Abstract

Nowadays, there is a growing concern about the environmental impacts of colored wastewater. Thus, the present work aims the synthesis, characterization and determination of photocatalytic activity of iron oxide (Fe2O3) nanocatalyst, evaluating the effect of hybridization with titanium (TiNPs-Fe2O3) and silver (AgNPs-Fe2O3) nanoparticles, on the degradation of Rhodamine B dye (RhB). Nanocatalysts were characterized by XRD, SEM, TEM, FTIR, N2 porosimetry (BET/BJH method), zeta potential and DRS. Photocatalytic tests were performed in a slurry reactor, with the nanocatalyst in suspension, using RhB as a target molecule, under ultraviolet (UV) and visible radiation. Therefore, the photocatalytic activity of the nanocatalysts (non-doped and hybridized) was evaluated in these ideal conditions, where the AgNPs-Fe2O3 sample showed the best photocatalytic activity with a degradation of 94.1% (k = 0.0222 min−1, under UV) and 58.36% (k = 0.007 min−1, under visible), while under the same conditions, the TiO2-P25 commercial catalyst showed a degradation of 61.5% (k = 0.0078 min−1) and 44.5% (k = 0.0044 min−1), respectively. According with the ideal conditions determined, reusability of the AgNPs-Fe2O3 nanocatalyst was measured, showing a short reduction (about 8%) of its photocatalytic activity after 5 cycles. Thus, the Fe2O3 nanocatalyst can be considered a promising catalyst in the heterogeneous photocatalysis for application in the degradation of organic dyes in aqueous solution.

Subject terms: Pollution remediation; Environmental, health and safety issues

Introduction

Dyes are substances with high application potential in the most diverse areas, mainly to color the final products of textile, precious stones, leather, paper, plastics and food. For example, it is estimated that there are more than 100,000 synthetic dyes, with an annual production of more than 700,000 tons worldwide, generating a significant amount of wastewater1. In addition, these colored waters are characterized by complex aromatic compounds, making their biodegradation difficult, becoming an environmental liability. Thus, advanced processes are needed to promote their correct treatment in order to meet environmental norms and legislation2.

In this context, the Advanced Oxidative Processes (AOPs), highlighting the heterogeneous photocatalysis, becomes an attractive alternative, since they are technologies with potential to oxidize a great variety of complex organic compounds3, using a highly oxidant and less selective species (the hydroxyl radical, •OH), capable of mineralize many organic compounds4. Thus, the heterogeneous photocatalysis involves the photoactivation of a semiconductor (catalyst), under visible or ultraviolet radiation, with energy equal to or greater than band gap energy5, promoting oxy-reduction reactions on the catalytic surface and thus the degradation of organic pollutants.

Among the most used catalysts are titanium dioxide (TiO2), cadmium sulfide (CdS), zinc oxide (ZnO), zinc sulphide (ZnS), tungsten trioxide (WO3), tin dioxide (SnO2) and iron oxide III (Fe2O3)6. However, these catalysts generally present a low specific surface area and porosity, limiting intraparticle diffusion of organic pollutants, compromising its photocatalytic activity7–9.

Nanocatalyst has emerged as an alternative to increase catalytic efficiency, since it has advantages over commercial catalysts, such as higher specific surface area and porosity, making them with great potential application in heterogeneous photocatalysis10. One of the strategies used to increase the photocatalytic activity of nanocatalysts is the usage of hybridization with noble metal and metals, in order to reduce the recombination between photoelectrons/holes pairs and reducing the energy required to its photoactivation, allowing its application to visible radiation11–16. In addition, Rhodamine B dye (RhB) (C28H31N2O3Cl), a highly water soluble organic cation dye, belongings to the class of xanthenes, whose contact with humans can cause irritation to the skin, airways and eyes17. Moreover, it presents the chromophoric groups (−C=C −/− C=N−), as well as a characteristic carcinogenicity and neurotoxicity activity.

In this context, the present work aims the synthesis, characterization and determination of photocatalytic activity of Fe2O3 nanocatalyst, hybridized with titanium nanoparticles (TiNPs) and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on the degradation of Rhodamine B (RhB) dye, under UV and visible radiation.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of the Fe2O3 nanocatalyst

The synthesis of iron oxide nanocatalyst followed the chemical precipitation by sodium borohydride method, according to the literature18. Sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 0.2 mol L−1, Neon, PA) and ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3∙H2O, 0.05 mol L−1, Synth, PA) were mixed for 30 minutes, under magnetic stirring (250 rpm). After, the synthesized nanoparticles were vacuum filtered and washed with deionized water and diluted ethanol (~5%). Parameters such as pH (≈ 7), reagents concentrations, stirring speed, reaction time and temperature (23 ± 0.5 °C) were kept constant in order to avoid influence on the composition and properties of nanocatalyst.

Synthesis of nanoparticles (NPs)

For silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), 75 mL of sodium borohydride solution (0.002 mol L−1, Neon, PA) was added, in ice bath, under for magnetic stirring for 10–15 min. with 25 mL of a silver nitrate solution (0.001 mol L−1, Synth, PA) (rate of 1 drop s−1), forming silver nanoparticles. It is noteworthy that titanium nanoparticles were commercially purchased (TiO2, Evonik Aeroxide P25).

Synthesis of hybridized nanocatalyst

For hybridization of Fe2O3 nanocatalyst, the impregnation methodology was used with TiNPs and AgNPs, according to the literature19. Samples were magnetic stirring at room temperature for 90 min, after calcined at 450 °C (heating rate 10 °C min−1) for 4 hours. Finally, the granulometry was standardized with milling and sieving (# 12). Hybridized nanocatalysts with NPs were labeled as TiNPs-Fe2O3 and AgNPs-Fe2O3, respectively.

Characterization of nanocatalyst

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to determine the crystallinity of the samples in a Bruker D2 Advance diffractometer with a copper tube (Kα = 1.5418 Ǻ) in the range of 5° to 70°, with tension acceleration and applied current of 30 kV and 30 mA, respectively.

For zeta potential (PZ), Malvern-Zetasizer® model nanoZS (ZEN3600, UK) with closed capillary cells (DTS 1060) (Malvern, UK) was used to measure the zeta potential values of the samples.

N2 porosimetry was used to evaluate the textural properties of specific surface area (SBET) and porosity (pore diameter – Dp and pore volume – Vp) using in an equipment Gemini VII 2375 Surface Area Analyzer Micromeritics® and BET/BJH Methods (P Po−1 = 0.05–0.35).

Band gap energy was determined by diffuse reflectance spectroscopy at UV radiation (UV DRS) using a Varian Cary Scan Spectrophotometer with DRA-CA-301 accessory (Labsphere) coupled in the diffuse reflectance mode to determine the energy band gap by means of the Kubelka–Munk function with scans ranged from 200 to 600 nm.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Transmission electronic microscopy (TEM) were used to morphologically characterize the nanocatalysts (Fe2O3, TiNPs-Fe2O3 and AgNPs-Fe2O3) using a JSM5800 (JEOL) and JEM 1200 Exll (JEOL) microscope, respectively. Moreover, the samples were coated with a thin layer of conductive gold by a sputtering technique.

Effect of the photolysis and adsorption on the RhB degradation

To evaluate the influence of adsorption on degradation of RhB dye, were carried out preliminary tests (time = 90 min, pH ≈ 4.03, [Fe2O3] = 0.7 g L−1 and [RhB] = 20 mg L−1) in dark (without irradiation) conditions to establish the time required for the equilibrium of RhB molecule on nanocatalyst surface. Moreover, the effect of photolysis on RhB degradation was carried out by tests without catalyst, only under radiation with RhB dye solution (20 mg L−1, 61.8 W m−2 for UV irradiation and 202 W m−2 for visible irradiation and time = 60 min).

Photocatalytic activity

Photodegradation tests were carried out using a solution of RhB, as the target molecule, and nanocatalysts in suspension (slurry). Tests were performed in two stages: (a) dark stage (absence of radiation), where adsorption/desorption equilibrium of the target molecule occurred on the surface of the nanocatalyst, with a duration of 60 minutes, and (b) a photocatalytic reaction step (with visible or UV radiation) with duration of 120 minutes (collections at predetermined times of (0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, and 120 minutes). Then the samples were centrifuged (Cientec CT-5000R refrigerated centrifuge) for 20 minutes with a rotation of 5,000 rpm and finally diluted (1:10 v/v).

Moreover, the absorbance measurements of solutions collected during reactions were carried out in a double-beam spectrophotometer (Varian, Cary 100) with a halogen lamp at the wavelength characteristic of RhB (λ = 553 nm)

Kinetic study of RhB degradation

In order to determine the specific reaction rate (k), a kinetic study of RhB dye degradation, under UV and visible radiation over time, was carried out according to the classic heterogeneous kinetic model (pseudo first-order model) (Eqs. 1 and 2)20,21:

| 1 |

Or:

| 2 |

Experimental designs

Central Rotatable Composite Design (CRCD) (Statistic 8.0, StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) symmetrical and of second order was used to determine the ideal reaction conditions (pH, [RhB] and [Fe2O3]) for the degradation of RhB dye, constituted of a factorial 23, with 8 tests, 3 central points, and 6 axial points, totalizing 17 experiments, according to Table 1.

Table 1.

Factorial planning matrix 23 for Fe2O3 nanocatalyst.

| Order | [RhB] (mg L−1) | [Fe2O3] (g L−1) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|

| (−1.68) | 5 | 0.5 | 2 |

| (−1) | 24.25 | 1.41 | 4.03 |

| 0 | 52.5 | 2.75 | 7 |

| (+1) | 80.74 | 4.08 | 9.97 |

| (+1.68) | 100 | 5 | 12 |

Results and Discussion

Characterization of nanocatalysts

Table 2 shows the results of N2 porosimetry, DRS and zeta potential characterization.

Table 2.

Surface area (SBET), pore volume (Vp), pore diameter (Dp), band gap energy (Eg) and zeta potential (PZ) of the synthesized nanocatalysts.

| Samples | SBET (m² g−1) | Vp (cm³ g−1) | Dp (nm) | Eg (eV) | ZP (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 (P25) | 56 | 0.07 | 4.8 | 3.2 | −24.0 |

| Fe2O3 | 158 | 0.93 | 22.6 | 2.2 | −13.3 |

| TiNPs- Fe2O3 | 304 | 0.02 | 2.9 | 2.0 | −11.5 |

| AgNPs- Fe2O3 | 505 | 1.60 | 3.5 | 1.8 | −10.2 |

According to Table 2, AgNPs- Fe2O3 showed the highest SBET (505 m² g−1), while TiNPs- Fe2O3, (304 m² g−1), while Fe2O3 (158 m2 g−1) and TiO2 (P25) (56 m2 g−1) nanocatalysts. In relation to pore volume (Vp), AgNPs-Fe2O3 showed the highest volume (1.6 cm³ g−1). In addition, according to pore diameter (Dp), all nanocatalysts (non-doped and doped) showed mesoporous characteristics22. For heterogeneous photocatalysis, surface area and porosity (pore volume and diameter) are factors that directly affect photocatalytic performance, since they affect the adsorption of the target molecule and oxy-reduction reactions for hydroxyl radical formation23,24.

The band gap of Fe2O3, TiNPs-Fe2O3 and AgNPs-Fe2O3 were found between 2.2; 2.0 and 1.8 eV, respectively. Thus, nanoparticles (NPs) promoted a reduction in conduction and valence bands, compared to Fe2O3 nanocatalyst, generating a decrease in the energy required for photoactivation of the hybridized nanocatalysts and shifting the application of nanocatalysts to the visible region of radiation25.

Moreover, all samples showed a negative charge surface potential (−10.25 to −13.30 mV), according to zeta potential, indicating a charge compatibility, since RhB dye is characterized by its cationic nature26,27, increasing the RhB adsorption capacity on the catalytic surface and thus a possible better photocatalytic activity.

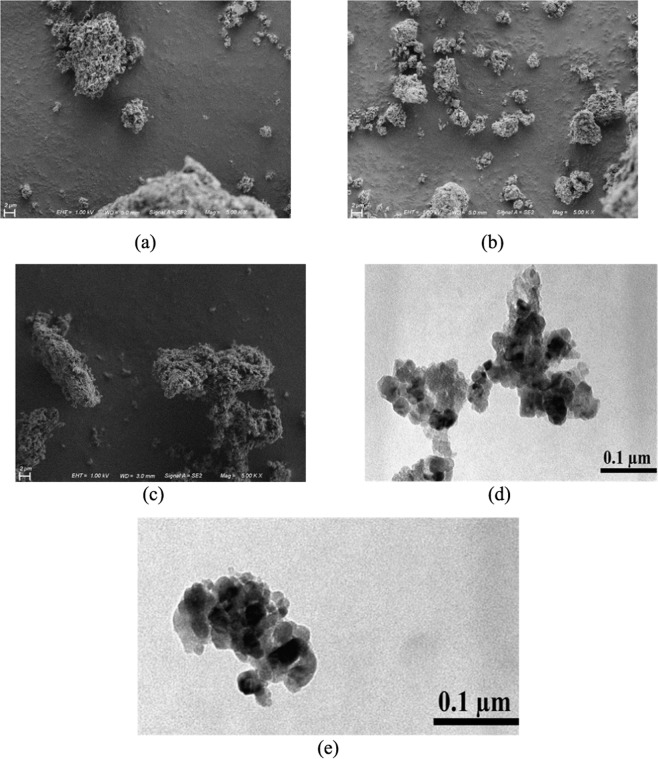

Figure 1 shows the X-ray diffractograms of the synthesized samples (without and with NPs hybridization).

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction of nanocatalysts, (Fe2O3, TiNPs-Fe2O3 and AgNPS-Fe2O3) and standard XRD (TiO2 and AgNO3).

According to Fig. 1, it is possible to identify the characteristic peaks of the photo phase of TiO2 (anatase) at 25.2°; 37.8°; 48.2°; 53.8° e 55.0° corresponding respectively to the plans (101), (004), (200), (105), e (211); some rutile diffraction peaks are still observed, the main one being 2θ = 27.4° which corresponds to the plane (110), according to JCPDS (Code 21–1272)28. Moreover, the silver nitrate X-ray diffraction pattern (AgNO3) showed the characteristic peaks, with their respective crystalline planes, at 30.2° (001), 35.6° (111), 43.6° (200) and 62.3° (220)29. In addition, it was possible to identify peaks of Fe2O3 oxide (33.2°, 35.6°, 40.9°, 54.1°, 62.5° and 64.1°) (JCPDS - Code 01–1053)30,31. Thus, the hybridization process with the NPs did not promote the formation of new peaks, as well as titanium and silver characteristic peaks were identified on Fe2O3 sample, indicating a successful hybridization.

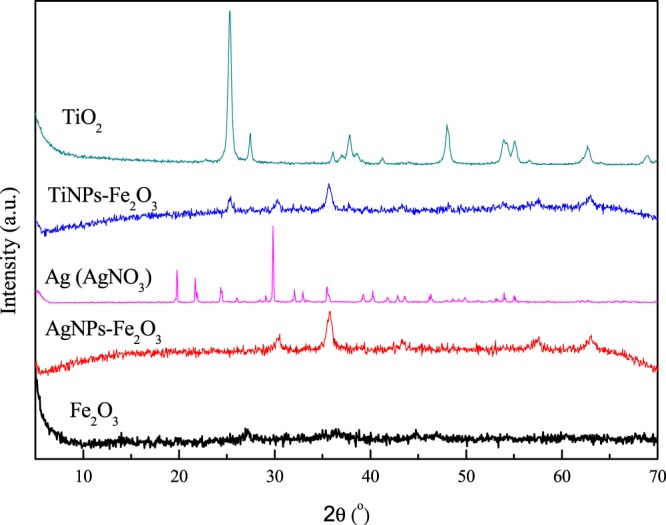

FTIR analysis was used as a qualitative analysis technique to determine the functional groups present in the synthesized materials, according to Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectrum of nanocatalysts.

According to Fig. 2, iron oxide showed at 3394 cm−1 strip, is attributed to stretch vibrations (ν), while the 1620 cm−1 strip is attributed to flexural vibrations (δ) due to water adsorbed on the surface of the iron oxide nanoparticles32. The band observed at 611 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of MTh-O-MOh, where MTh and MOh correspond to iron occupying tetrahedral and octahedral positions, respectively. TiNPs showed at 590 cm−1 due to the vibration of the TiO-O bond33,34.

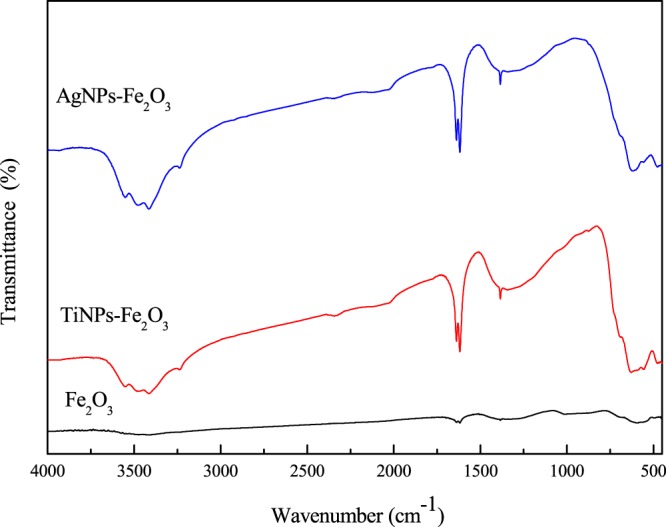

Figure 3 shows SEM micrographs of the nanocatalysts (a) Fe2O3, (b) TiNPs-Fe2O3 and (c) AgNPs-Fe2O3, while Fig. 3(d,e) show the TEM micrographs of the TiNPSs-Fe2O3 and AgNPs-Fe2O3 samples, respectively. Then, it was possible to identify a heterogeneous surface with a random distribution of the TiNPs and AgNPs, with the formation of small clusters of NPs. Then, it can be explained through of the zeta potential (surface charge), since using NPs, the ZP showed a smaller between the nanoparticles, causing a lower dispersion, in relation to Fe2O3 nanocatalyst (with higher value of ZP)33. Thus, this greater dispersion of NPs tends to promote changes in the textural properties of nanocatalysts, such as an improve of the specific area and a greater number of active sites to conductive the RhB adsorption, directly affecting photocatalytic activity34. Therefore, TEM micrographs showed the presence of NPs (TiNPs and AgNPs) over Fe2O3 in spherical shape with a diameter around 3 nm.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs for the samples: (a) Fe2O3, (b)TiNPs- Fe2O3 and (c) AgNPs- Fe2O3, and TEM micrographs for the (d) TiNPs-Fe2O3 and (e) AgNPs-Fe2O3.

Adsorption and photolysis

Preliminary tests of the adsorption showed that the minimum time necessary for the adsorption equilibrium of RhB was 60 minutes, with an adsorption percentage of 4.71, 8.70 and 10.32% to Fe2O3, TiNPs-Fe2O3 and AgNPs-Fe2O3, respectively. The preliminary tests of photolysis indicated that only 14% (UV radiation) and 4% (visible radiation) of RhB were degraded after 60 minutes.

Central rotatable composite design

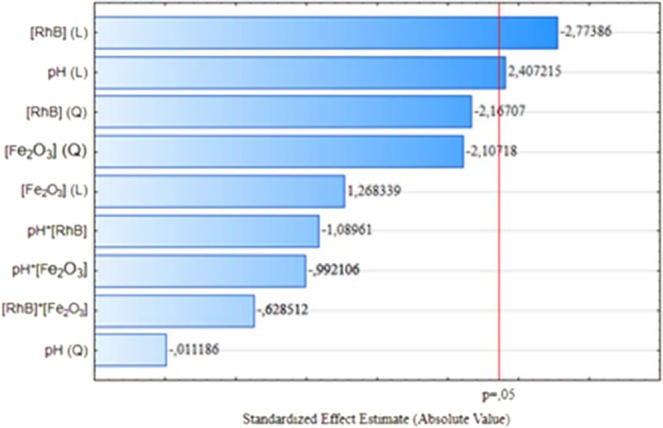

Figure 4 shows the Pareto chart used to evaluate the main effects of the central rotatable composite design (pH, [RhB] and [Fe2O3]). The reduced quadratic model (Eq. (3)) represents the Fe2O3 CRCD experiments, in which “y” represents the dependent variable (percentage of photocatalytic degradation after 120 minutes).

| 3 |

Figure 4.

Pareto chart on the effect of the pH, [RhB] and [Fe2O3] on the degradation of RhB dye.

According to Fig. 4, the RhB concentration showed a negative effect, thus with increasing RhB concentration occurs a reduction of the photocatalytic activity on RhB degradation occurs due to the reduction in the number of active sites available for adsorption on surface of Fe2O3 the nanocatalyst35. About the effect of pH, it has a positive effect on RhB degradation, since with the increase of the pH, the surface of Fe2O3 nanocatalyst is more deprotonated, increasing the compatibility of charges between RhB and Fe2O3 and thus increasing adsorption and photocatalytic activity36.

Therefore, after all the photocatalytic tests, the ideal conditions determined were 1.41 g L−1 to Fe2O3 nanocatalyst, 24.25 mg L−1 RhB concentration and pH = 9.97, which showed the greatest degradation of the 77.38%, after 120 minutes under UV radiation.

Photocatalytic performance

The photocatalytic performance of nanocatalysts (Fe2O3, TiNPs-Fe2O3 and AgNPs-Fe2O3) was evaluated by the photodegradation of RhB, under UV and visible radiation, using the ideal conditions.

After 120 min of UV radiation, 77.38% (k = 0.0124 min−1), 88.03% (k = 0.0173 min−1) and 94.10% (k = 0.022 min−1) of RhB were degraded using Fe2O3, TiNPs-Fe2O3 and AgNPs-Fe2O3, while 38.03% (k = 0.0039 min−1), 48.36% (k = 0.0055 min−1) and 58.36% (k = 0.0070 min−1) of RhB were degraded using Fe2O3, TiNPs-Fe2O3 and AgNPs-Fe2O3 under visible radiation, respectively, according to Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Photocatalytic activity of nanocatalysts (Fe2O3, TiNPs-Fe2O3 and AgNPs-Fe2O3) on RhB degradation under UV (a) and visible (b) radiation after 120 minutes ([catalyst] = 1.41 g L−1, [RhB] = 24.25 mg L−1, T = 30 °C, pH = 9.97, UV radiation of 61.8 W m−2, visible radiation of 202 W m−2 and error 5%).

According to Fig. 5, the hybridization of Fe2O3 nanocatalyst with NPs (TiNPs and AgNPs) promoted an increase in the photocatalytic activity on the RhB degradation under UV radiation (13.8% using to TiNPs-Fe2O3 and 21.6% with AgNPs-Fe2O3) and visible radiation (27.2% - TiNPs-Fe2O3 and 55.4% - AgNPs-Fe2O3). This can be explained, due the fact that the nanoparticles (TiNPs and AgNPs) can act as electron traps facilitating the electron hole separation and subsequent transference of trapped electrons to the absorbed O2 acting as an electron acceptor on the surface of Fe2O3 nanocatalyst35,36. Thus, more molecules are adsorbed on the surface of hybridized nanocatalysts, enhancing the photo excited electron to the conduction band and simultaneously increasing the electron transfer to the adsorbed O2.

The power of the semiconductor material to act as a sensitizer and to enhance the photodegradation of the RhB is based on their electronic structure with filled valence bond and empty conduction bond37. The semiconductor photooxidation instigated the photocatalysis of RhB in solution, leaving the catalyst surface with a strong oxidative potential of an electron–hole pair (h+VB) (Eq. (4)), when photocatalyst was irradiated with higher energy than that of band gap energy (Eg), which allows the oxidation of the RhB molecule in a direct manner to the reactive intermediates (Eq. (5)).The hydroxyl radical (OH•), the exceptionally strong and a non-selective oxidant which is formed either by decomposition of water (Eq. (6)) or by reaction of hole along with hydroxyl ion (OH−) (Eq. (7)) is also responsible for degradation of phenol molecule. Leading to incomplete or complete mineralization of many organic molecules (Eq. (8))38.

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

Effect of AgNPs-Fe2O3 recycling

The effect of reuse of the AgNPs-Fe2O3 nanocatalyst under visible radiation (202 W m−²) was evaluated in 5 times, according to Table 3.

Table 3.

Effect of AgNPs-Fe2O3 nanocatalyst reuse on degradation of the RhB.

| Cycle number | Degradation (%) |

|---|---|

| Cycle I (fresh nanocatalyst) | 58.36 |

| Cycle II | 57.40 |

| Cycle III | 56.68 |

| Cycle IV | 55.73 |

| Cycle V | 54.39 |

| Cycle VI | 53.69 |

According to Table 3, the AgNPS-Fe2O3 nanocatalyst showed a photostability after five recycling processes, with a small decrease (about 8%) in the photocatalytic activity (58.36% to 53.69%), under visible radiation.

Conclusion

According to the characterization and photocatalytic activity results, the hybridization process with NPs (TiNPs and AgNPs) caused positive changes in the properties of Fe2O3 nanocatalyst for heterogeneous photocatalysis, such as: reduction of band gap energy (2.2 eV to 2.0 eV - TiNPs-Fe2O3 and 1.8 eV - AgNPs-Fe2O3); increase of surface area (158 m² g−1 to 304 m² g−1 - TiNPs-Fe2O3 and 505 m² g−1 - AgNPs-Fe2O3) and increase in photocatalytic activity under UV and visible radiation. Therefore, nanoparticle hybridization on nanocatalysts is a great option to improve the photocatalytic performance for degradation of organic pollutants (such as dyes) by heterogeneous photocatalysis.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Laboratory of Catalysis and Polymers (K106) of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) and Nanotechnology Laboratory (S013) of the Franciscan University for the support and assistance to carry out the present work. Moreover, this work received financial support from the Foundation for Research of the State of Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS – Project 19/2551-0001362-0), so all thanks.

Author contributions

P. Muraro designed, performed most of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. S.R. Mortari, B.S. Vizzotto, G. Chuy, C. dos Santos, L.F.W. Brum and W.L. da Silva supervised the research work. All authors were contributed to discussion and writing the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Al-Fawwaz AT, Abdullah M. Decolorization of methylene blue and malachite green by immobilized Desmodesmus sp. isolated from North Jordan. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2016;7:95–99. doi: 10.7763/IJESD.2016.V7.748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Araújo KS, Antonelli R, Gaydeczka B, Granato AC, Malpass GRP. Advanced oxidation processes: a review of fundamentals and applications in the treatment of urban and industrial wastewaters. Rev. Ambient. Água. 2016;11:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma J, Li L, Zou J, Kong Y, Komarneni S. Highly efficient visible light degradation of Rhodamine B by nanophasic Ag3PO4 dispersed on SBA-15. Mat. Res. C. 2014;48:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira VJ, Fernandes D, Carvalho G, Benoliel MJ, San Romão MV. Assessment of the presence and dynamics of fungi in drinking water sources using cultural and molecular methods. Water Res. 2010;44:4850–4859. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirkanniemi K, Sillanpää M. Heterogeneous water phase catalysis as an environmental application: a review. Chemosphere. 2002;48:1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Zhao J, Liu H, Huang J. Design, modification and application of semiconductor photocatalysts. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. 2018;93:590–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2018.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collivignarelli MC, Abbà A, Miino MC, Damiani S. Treatments for color removal from wastewater: State of the art. J. Environ. Manage. 2018;236:727–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low J, Yu J, Jaroniec M, Wageh S, Al‐Ghamdi AA. Heterojunction Photocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:16016940. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Low J, Cheng B, Yu J. Surface modification and enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of TiO2: a review. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;392:658–686. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.09.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva MF, Pineda EAG, Bergamasco R. Application of nanostructured iron oxides as adsorbents and photocatalysts in the removal of pollutants from waste water. Quim. Nova. 2015;38:393–398. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Einaga H, Ibusuki T, Futamura S. Improvement of catalyst durability by deposition of Rh on TiO2 in photooxidation of aromatic compounds. Envir. Sci Tech. 2004;38:285–289. doi: 10.1021/es034336v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozlova EA, Vorontsov AV. Nobel metal and sulfuric acid modified TiO2 photocatalyts: mineralization of organophorous compounds. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2006;63:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.You XF, Chen F, Zhang J, Anpo M. A novel deposition precipitation method for preparation of Ag-loaded titanium dioxide. Catal. Lett. 2005;102:247–250. doi: 10.1007/s10562-005-5863-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Liu B, Nakata K. Effects of crystallinity, {001}/{101} ratio, and Au decoration on the photocatalytic activity of anatase TiO2 crystals. Chinese J. Catal. 2019;40:403–412. doi: 10.1016/S1872-2067(18)63174-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bui VKH, et al. Synthesis of MgAC-Fe3O4/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites via sol-gel chemistry for water treatment by photo-Fenton and photocatalytic reactions. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:11855–711866. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48398-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu W, et al. Fabrication of commercial pure Ti by selective laser melting using hydride-dehydride titanium powders treated by ball milling. J. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2019;35:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2018.09.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta VK, Suhas S. Application of low-cost adsorbents for dye removal – A review. J. Environ. Manage. 2009;90:2313–2342. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Y, Li X, Cao J, Zhang W, Wang HP. Characterization of zero-valent iron nanoparticles. Adv. Colloid Interfac. 2006;120:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melo MA, Jr, Santos LSS, Gonçalves MC, Nogueira AF. Preparation of silver and gold nanoparticles: a simple method to introduce nanotechnology into teaching laboratories. Quim. Nova. 2012;35:1872–1878. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422012000900030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gogate PR, Pandit AB. A review of imperative technologies for wastewater treatment I: oxidation technologies at ambient conditions. Adv. Environ. Res. 2004;8:501–551. doi: 10.1016/S1093-0191(03)00032-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaya UI, Abdullah AH. Heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants over titanium dioxide: A review of fundamentals, progress and problems. J. Photoch. Photobio. C. 2008;9:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2007.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.IUPAC Manual of symbols and Terminology. Pure Apll. Chem. 1972;31:578–592. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bet-moushoul E, Mansourpanah Y, Farhadi K, Tabatabaei M. TiO2 nanocomposite based polymeric membranes: A review on performance improvement for various applications in chemical engineering processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2016;283:29–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.06.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vadivel S, Rajarajan G. Effect of Mg hybridization on structural, optical and photocatalytic activity of SnO2 nanostructure thin films. J. Mater Sci. Mater. 2015;26:3155–3162. doi: 10.1007/s10854-015-2811-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Debrassi A, Largura MCT, Rodrigues CA. Adsorption of Congo red dye by hydrophobic o-carboxymethyl chitosan derivatives. Quim. Nova. 2011;34:764–770. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salleh MAM, Mahomoud DK, Karim WA, Idris A. Cationic and anionic dye adsorption by agricultural solid wastes: A comprehensive review. Desalination. 2011;280:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2011.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jarlbring M, Gunneriusson L, Hussmann B, Forsling W. Surface complex characteristics of synthetic maghemite and hematite in aqueous suspensions. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2005;285:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sansiviero MTC, de Faria DLA. Influence of thermal treatment on the photocatalyst nanocomposite ZnO/TiO2. Quim. Nova. 2015;38:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boningari T, Inturi SNR, Suidan M, Smirniotis PG. Novel continuous single-step synthesis of nitrogen-modified TiO2 by flame spray pyrolysis for photocatalytic degradation of phenol in visible light. J. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2018;34:1494–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2018.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu X, Liu S, Yu J. Superparamagnetic γ-Fe2O3@SiO2@TiO2 composite microspheres with superior photocatalytic properties. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2011;104:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie T, Liu Y, Wang H, Wu Z. Synthesis of α-Fe2O3/Bi2WO6 layered heterojunctions by in situ growth strategy with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7551–7562. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43917-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devi LB, Mandal AB. Self-assembly of Ag nanoparticles using hydroxypropyl cyclodextrin: synthesis, characterization and application for the catalytic reduction of p-nitrophenol. Rsc. Adv. 2013;3:5238–5253. doi: 10.1039/c3ra23014g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaleji BK, Sarraf-Mamorry R, Nakata K, Fujishima A. The effect of Sn dopant on crystal structure and photocatalytic behavior of nanostructured titania thin films. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Techn. 2011;60:90–99. doi: 10.1007/s10971-011-2560-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qamar M, Muneer M. A comparative photocatalytic activity of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide by investigating the degradation of vanillin. Desalination. 2009;249:535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2009.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daneshvar N, Aber S, Dorraji MS, Khataee AR, Rasoulifard MH. Photocatalytic degradation of the insecticide diazinon in the presence of prepared nanocrystalline ZnO powders under irradiation of UV-C light. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007;58:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2007.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Da Silva WL, Lansarin MA, Dos Santos JHZ, Silveira F. Photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B, paracetamol and diclofenac sodium by supported titania-based catalysts from petrochemical residue: effect of hybridization with magnesium. Water Sci. Technol. 2016;74:2370–2383. doi: 10.2166/wst.2016.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gnanaprakasam A, Sivakumar VM, Thirumarimurugan M. Influencing parameters in the photocatalytic degradation of organic effluent via nanometal oxide catalyst: A review. Indian J. Mater. Sci. 2015;1:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kansal SK, Singh M, Sud D. Studies on photodegradation of two commercial dyes in aqueous phase using different photocatalysts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007;141:581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]