Abstract

The inability to effectively stimulate cardiomyocyte proliferation remains a principle barrier to regeneration in the adult human heart. A tightly regulated, acute inflammatory response mediated by a range of cell types is required to initiate regenerative processes. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a potent lipid signaling molecule induced by inflammation, has been shown to promote regeneration and cell proliferation; however, the dynamics of PGE2 signaling in the context of heart regeneration remain underexplored. Here, we employ the regeneration-competent zebrafish to characterize components of the PGE2 signaling circuit following cardiac injury. In the regenerating adult heart, we documented an increase in PGE2 levels, concurrent with upregulation of cox2a and ptges, two genes critical for PGE2 synthesis. Furthermore, we identified the epicardium as the most prominent site for cox2a expression, thereby suggesting a role for this tissue as an inflammatory mediator. Injury also drove the opposing expression of PGE2 receptors, upregulating pro-restorative ptger2a and downregulating the opposing receptor ptger3. Importantly, treatment with pharmacological inhibitors of Cox2 activity suppressed both production of PGE2, and the proliferation of cardiomyocytes. These results suggest that injury-induced PGE2 signaling is key to stimulating cardiomyocyte proliferation during regeneration.

Subject terms: Stem-cell niche, Regeneration

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease is currently the leading cause of mortality worldwide1. A fundamental limitation to cardiac regeneration in adult humans is the inability to effectively replenish lost cardiomyocytes (CMs). In stark contrast, multiple vertebrates, including the axolotl, newt, zebrafish, and neonatal mouse, demonstrate the remarkable capacity to regenerate lost or damaged myocardium through the proliferation of resident cardiac muscle cells2–5. Therefore, elucidating the cues that promote CM proliferation in these models will be crucial to informing therapies to stimulate regeneration in the injured human heart.

Acute inflammation is a hallmark of the tissue damage response, requiring the meticulous orchestration of signals from multiple cell types. CMs, endothelial cells, immune cells, and more recently, epicardial cells, have been shown to play essential roles in crafting the injury micro-environment6–11. A highly regulated inflammatory response is required for regeneration, and abrogating this response blocked regeneration in both zebrafish and neonatal mouse hearts12–14.

Among the principal signaling molecules released during acute inflammation are the prostaglandins. Notably, Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has been shown to promote tissue regeneration by directly stimulating the proliferation of target cells15,16, as well as indirectly, by governing the recruitment and polarization of immune cells17–19. PGE2 is synthesized through the sequential catalytic activity of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase −1 and −2 (colloquially termed COX1 and −2), followed by the terminal synthase Prostaglandin E synthases (PTGES). There are four membrane-bound PGE2 receptors. Signaling through these receptors has pleiotropic effects; however upregulation of Prostaglandin E2 receptor 2 (EP2) and EP4 is frequently associated with cancer progression, cell survival and proliferation20–24, while activation of EP3 often stimulates opposing cellular responses25–27.

The multi-faceted effects of PGE2 activity are also mediated by the spatio-temporal dynamics of signal intensity. Although PGE2 has been demonstrated to accelerate skeletal muscle regeneration28, it also exacerbated ischemic damage in the brain, and inhibited repair and regeneration of the liver29–31. Of concern, PGE2-pathway genes are also upregulated in many cancers32–35, and while short-term PGE2 treatment promoted regeneration of damaged colon tissues, prolonged exposure-initiated tumor formation36. Therefore, it is critical to decode the precise dynamics of pro-regenerative PGE2 signaling to capitalize upon the benefits of this inflammatory mediator.

In the present study, we show that the regenerating zebrafish heart upregulates enzymes essential for PGE2 synthesis, and modulates PGE2 receptor expression to optimize pro-regenerative signaling. Moreover, we identify the epicardium as a focus of cox2a expression, implicating this tissue as a source of inflammation-associated PGE2 signaling. Importantly, pharmacological inhibition of Cox2 activity suppressed both levels of PGE2, and CM proliferation early in the regenerative process. Taken together, our data suggest that PGE2 promotes CM proliferation during the acute inflammatory response, and holds potential therapeutic promise for humans.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish husbandry and heart amputation

All animal studies were performed in accordance with an approved protocol (Protocol 16–14) by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at MDI Biological Laboratory. Wild type animals used were of the Ekkwill (EK) or EKxAB mixed background strains. Transgenic lines used in this study were Tg(cmlc2:EGFP)37, Tg(tcf21:DsRed)38, Tg(fli1a:EGFP)39, and Tg(mpeg1:YFP)40. Adult zebrafish 4–18 months of age were anaesthetized in a 1:1,000 dilution of 2-phenoxyethanol. Approximately 20% of the ventricular apex was resected with iridectomy scissors, as previously described5.

Intraperitoneal microinjection of selective Cox2 inhibitors

Zebrafish were injected daily, beginning on the day of surgery, with 220 ng/g of NS-398 or 1 μg/g Celecoxib (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI #70590, #10008672); vehicle controls were 0.1% DMSO, or 0.44% EtOH, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Hearts were extracted, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, equilibrated in 30% sucrose, then embedded in TBS tissue freezing medium (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH #TFM-C) and sectioned to 10 μm. Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-Mef2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA #SC-313; 1:75) and mouse anti-Pcna (Sigma-Aldrich, Nadick, MA #P8825; 1:400). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) for anti-Mef2, and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) for anti-Pcna (Invitrogen - Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA #A11034, #A11020). Images were captured at 20× using an Olympus BX53 microscope and Retiga 2000DC camera. CM proliferation indices were calculated as a percentage of Mef2(+)Pcna(+) cells relative to the total number of Mef2(+) cells in a defined area adjacent to the injury.

In situ hybridizations

Hearts were processed as described above, and serial sections were subjected to in situ hybridization studies with DIG-labelled RNA probes directed against cox2a, cox2b and ptger2a using previously described methods5,41. cDNA fragments corresponding to the first 900-bp of each gene were synthesized (www.IDTDNA.com) and cloned into the pMiniT vector (www.NEB.com). Antisense probes were synthesized with either SP6 or T7 Polymerase using the Roche DIG Labelling Kit (SP6/T7) in accordance to the manufacturer’s suggested protocol (www.Roche.com). Negative controls included cox2a riboprobe but no secondary antibody, and secondary antibody only. Images were captured using settings described under the Immunohistochemistry methods section.

Gene expression studies of whole heart tissues

Ventricles were isolated in ice-cold PBS, placed immediately in Ambion TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen - Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA #2302700), and homogenized using an electric homogenizer. RNA was extracted using Zymo Direct-zol RNA Microprep Kit, (Zymo Research Corp, Irvine, CA #R2069), followed by treatment with DNAseI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA #M0303), and final purification with RNA Clean & Concentrator-5 Kit (Zymo Research Corp, Irvine, CA #R1014). cDNA was synthesized using ProtoScript® II First Strand cDNA Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA # E6560S). qPCR studies were performed in technical triplicate using Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBR® Green QPCR Master Mix (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA #600882) and transcript specific primers (Table 1) in a Roche LightCycler® 480. Relative gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method and normalized to the reference gene rpl13a. Fold-change was expressed on a log2 scale.

Table 1.

Gene expression primer sequences.

| Gene | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| cox1 FWD | CGGAAAGTGCTCACAGTAAGA |

| cox1 REV | CTGGTGTAGTAGGTGATGTTGG |

| cox2a FWD | AACTCTATCGTCACCAC |

| cox2a REV | CCTGTCATCTCCTCAAA |

| cox2b FWD | GGCTCATCCTTATTGGTGAGACTAT |

| cox2b REV | TCGGGATCAAACTTGAGCTTAAAATA |

| ptger2a FWD | TGCGGATACATCACCATCCCTTGT |

| ptger2a REV | GTGGCGTAAACATTGGCATACGCT |

| ptger3 FWD | TGATGGTCACTGGAATGGTGGGAA |

| ptger3 REV | TCCACGCGGTCCCATTTCATATCT |

| ptger4a FWD | TGCCAATATTTCGGCTTCGTGCTG |

| ptger4a REV | ATGCGTAAATGGCGAGTAGGGTGA |

| ptges FWD | CATATGTGGAGCGCTGTAGG |

| ptges REV | GATGGGCTTGTCATGGAGTAG |

| rpl13a FWD | TCTGGAGGACTGTAAGAGGTATGC |

| rpl13a REV | AGACGCACAATCTTGAGAGCAG |

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) and gene expression

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from 12–45 hearts of zebrafish reporter strains as previously described, with modifications42. Briefly, ventricles were isolated and washed in ice-cold PBS to remove blood cells. Tissues were digested in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution plus 0.13 U/ml Roche Liberase DH (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA # 5401054001) at 37 °C, while stirring gently with a magnetic spinbar. Supernatants were collected every 5 minutes and neutralized with 10% sheep serum. Dissociated cells were spun down, washed in PBS, and resuspended in PBS plus 2% fetal bovine serum. The cell suspension was then strained through a 35 μm mesh and DAPI added as a viability dye. Sorting was performed on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), gated to exclude doublets, debris, and dead cells. Viable cells were sorted directly into Ambion TRIzol LS Reagent (Invitrogen - Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA # 10296–010). RNA was extracted using Zymo Direct-zol RNA Microprep kit, (Zymo Research Corp, Irvine, CA #R2069) as directed by the manufacturer. Total RNA was amplified with the Ovation® PicoSL WTA Kit (NuGEN, Redwood City, CA #3312) to generate cDNA for downstream qPCR analysis.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for PGE2

ELISA for PGE2 was conducted using the Prostaglandin E2 Human ELISA Kit (Invitrogen - Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA # KHL1701) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, ventricles were collected from six weight-matched clutchmates, washed in ice-cold PBS, and homogenized in 500 μl TRIS buffer. Homogenate was spun down at 1200 rpm for four min at 4 °C to eliminate particulate, and supernatant collected for ELISA. Assays were run in technical triplicate.

LC-MS/MS analysis: Lipid isolation

For each biological replicate, ventricles from five weight-matched clutchmates were isolated, washed in ice-cold PBS, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until shipment on dry ice to the University of Iowa for sample preparation and analysis; samples were processed and analyzed in a blinded manner. Tissues were homogenized in 1 ml sucrose buffer (250 mM sucrose, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.1, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA with fresh protease inhibitors) using a Dounce homogenizer. A small aliquot was set aside to quantify proteins for sample normalization. Protein was precipitated and separated from homogenates with the addition of 2 ml HPLC grade methanol (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) and centrifugation at 2,200 × g at 4 °C for 15 minutes. Supernatants containing lipids were diluted with 12.5 ml HPLC grade H2O (Fischer Scientific, Hampton, NH), and supplemented with 100 μl of internal standard stock including the following deuterated eicosanoids (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI): 0.2 ng/μl d8 arachidonic acid, 0.1 ng/μl d4 6-keto-prostaglandin (PG)F1α, 0.1 ng/μl d4 PGD2, 0.1 ng/μl d4 PGE2, 0.1 ng/μl d4 PGF2α, 0.1 ng/μl d4 thromboxane (TX)B2, 0.1 ng/μl d4 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2, 0.1 ng/μl d8 5-(S)-hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), 0.1 ng/µl 15(S)-HETE, and 0.1 ng/µl 12(S)-HETE diluted in 50% HPLC grade ethanol (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Samples were loaded onto a Strata-X 33 u Polymeric Reversed Phase column 60 mg/3 ml (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) that was previously conditioned with HPLC grade methanol and equilibrated with HPLC grade water. Lipids were washed with HPLC grade water and eluted in HPLC grade methanol. Eluate was dried using a SpeedVac and samples were suspended in 100 μl of liquid chromatography (LC) solvent A (water-acetonitrile-formic acid (63:37:0.02, v/v/v)) for LC-MS/MS analysis. Samples were stored at −80 °C until analyzed.

Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry

An ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column, 130 Å, 1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm with in-line filter (Waters, Milford, MA) was equilibrated at 35 °C at a flow rate of 300 μl/min with LC solvent A on an ACQUITY UPLC H-Class system (Waters, Milford, MA). A small portion of each sample, 30 μl, was loaded onto the column at a flow rate of 300 μl/min of 100% LC solvent A followed by a linear gradient to 20% LC solvent B (acetonitrile-isopropanol(50:50, v/v)) over six min, then increased to 55% LC solvent B over 0.5 min and 100% LC solvent B over 5.5 min and held for four min. Column was primed with 100% LC solvent A for three min between samples. Metabolites were directed to an ACQUITY TQ detector mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source set to negative ion mode (Waters, Milford, MA). Specific analytes were detected via multiple reaction monitoring and quantified using a standard curve of known concentration using MassLynx software (Waters, Milford, MA). Each standard (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) and internal standard was resolved at the follow retention time (RT) with the following mass transitions: arachidonic acid, RT 12.52 min, m/z 303 → 259; 6-keto- PGF1α, RT 1.47 min, m/z 369 → 207; PGD2, RT 3.42 min, m/z 351 → 189; PGE2, RT 2.94 min, m/z 351 → 189; PGF2α, RT 2.63 min, m/z 353 → 193; TXB2, RT 2.12 min, m/z 369 → 169; 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2, RT 8.62 min, m/z 315 → 271; 5-(S)-HETE, RT 9.58 min, m/z 319 → 115; 12-(S)-HETE, RT 9.24 min, m/z 319 → 179; 15-(S)-HETE, RT 9.15 min, m/z 319 → 175; d8 arachidonic acid, RT 12.45 min, m/z 311 → 267; d4 6-keto- PGF1α, RT 1.46 min, m/z 373 → 211; d4 PGD2, RT 3.36 min, m/z 355 → 193; d4 PGE2, RT 2.95 min, m/z 355 → 193; d4 PGF2α, RT 2.51 min, m/z 357 → 197; d4 TXB2, RT 2.13 min, m/z 373 → 173; d4 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2, RT 8.61 min, m/z 319 → 275; d8 5-(S)-HETE, RT 9.55 min, m/z 317 → 116. Results were further normalized to sample protein concentrations using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Results

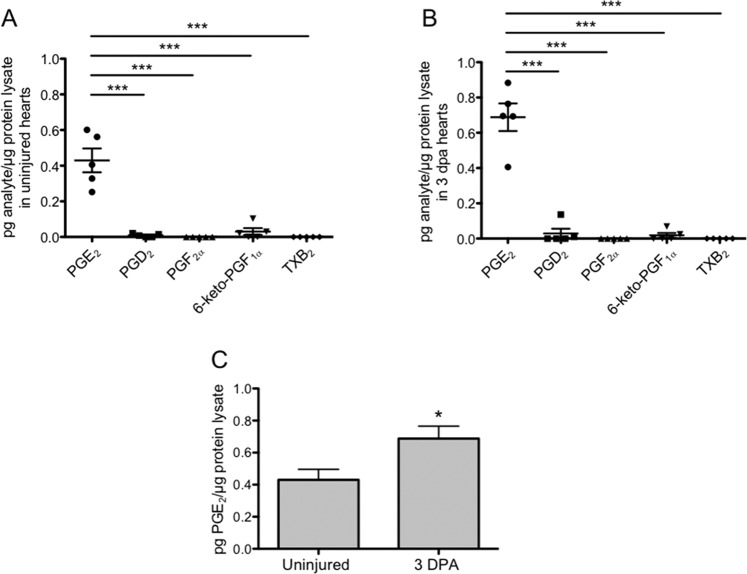

Cardiac injury triggers an elevation in PGE2

Prostaglandins are powerful lipid signals synthesized at the site of injury that regulate the inflammatory response. To profile cardiac prostaglandins and quantify changes associated with injury, we used Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). In uninjured hearts, PGE2 concentrations were significantly higher than those detected for other prostanoids. PGD2 and 6-keto PGF1α, a stable metabolite of prostacyclin, barely registered above background levels, while TXB2, a Thromboxane A metabolite, and PGF2α, were undetected (Fig. 1A). To define prostaglandin levels during regeneration, we amputated ~20% of the adult ventricle, allowed regeneration to proceed for 3 days, and extracted ventricles for analyses. At 3 days post-amputation (dpa), concentrations of PGE2 were again, significantly higher than all other prostanoids examined (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we found that at 3 dpa, concentrations of PGE2 increased by more than a 60% relative to uninjured hearts (Fig. 1C). Together, these experiments identify PGE2 as the most abundant prostanoid in the zebrafish heart, and establish an injury-induced increase in PGE2 concentrations.

Figure 1.

Cardiac injury triggers an elevation in PGE2 synthesis. (A,B) LC-MS/MS profiling showed that PGE2 concentrations were significantly elevated above all other prostaglandin species analyzed in both the uninjured heart (A), and at 3 dpa (B). (mean ± s.e.m. n = 5 biological replicates; 5 pooled ventricles per replicate. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ***P < 0.001). (C) LC-MS/MS analysis showed that PGE2 concentrations were significantly higher at 3 dpa, relative to uninjured hearts. (mean ± s.e.m. n = 5 biological replicates; 5 pooled ventricles per replicate. Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05).

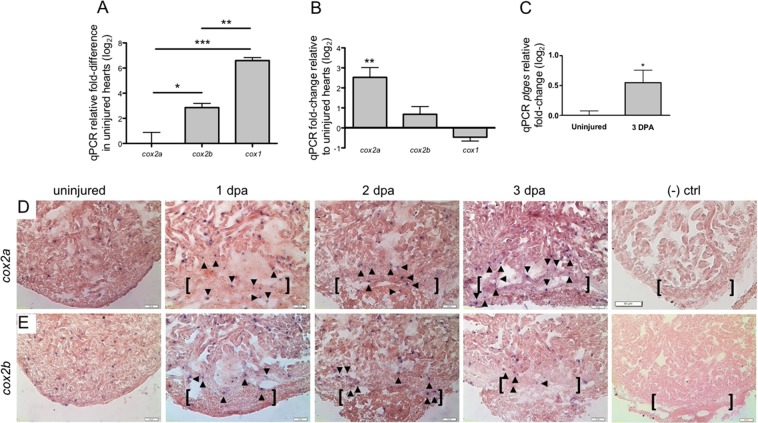

Enzymes critical to PGE2 synthesis are upregulated in regenerating adult hearts

Having shown that PGE2 is elevated in the heart after injury, we next asked how enzymes critical to PGE2 synthesis are modulated during regeneration. COX enzymes catalyze the first rate-limiting step in prostanoid synthesis. Mammals have two COX isozymes, constitutively expressed COX1, and inducible COX2. Three Cox isozymes have been identified in the zebrafish, a single ortholog of mammalian COX1, and two orthologs of mammalian COX2: Cox2a and -2b43. Downstream of the Cox enzymes, prostaglandin E synthase (Ptges), the zebrafish ortholog of mammalian PTGES, catalyzes the terminal step of PGE2 biosynthesis44.

To characterize relative expression of the Cox enzymes, we conducted qPCR studies in uninjured and 3 dpa regenerating hearts. These assays showed that in uninjured ventricles, cox1 expression was significantly elevated relative to both cox2a (>log2 6.5-fold) and cox2b (>log2 2.5-fold) (Fig. 2A). At 3 dpa however, cox2a levels had increased more than log2 2.5-fold relative to uninjured hearts. No significant changes were observed in cox2b or cox1 transcripts (Fig. 2B). Mirroring the response of cox2a, expression of the terminal prostaglandin synthase ptges was also significantly upregulated (>log2 0.5-fold) after amputation injury when compared to uninjured levels (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Enzymes critical to PGE2 production are upregulated in regenerating adult hearts. (A) qPCR studies demonstrated that cox1 levels in uninjured zebrafish ventricles were significantly higher than either cox2a or cox2b transcripts. Gene expression was calculated relative to cox2a (mean ± s.e.m. n = 4–5 biological replicates; 3–5 pooled ventricles per replicate. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (B) At 3 dpa, cox2a is the only Cox isozyme significantly upregulated relative to uninjured hearts, as determined by qPCR. (mean ± s.e.m. n = 4–5 biological replicates; 3–5 pooled ventricles per replicate. Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01). (C) Relative to uninjured hearts, ptges is significantly upregulated at 3 dpa. (mean ± s.e.m. n = 4 biological replicates; 3–5 pooled ventricles per replicate. Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05). (D,E) Representative images of cox2a (D) and cox2b (E) expression domains as revealed by in situ hybridization studies. (n = 4 biological replicates; brackets = approximate amputation zone; arrowheads demarcate signal within the injury zone). Representative (−) control 2 dpa hearts were hybridized with cox2a riboprobe without anti-DIG antibody (top right panel) or with anti-DIG only (bottom right panel). (n = 2 biological replicates).

To define the spatial distribution of cox2a and cox2b during heart regeneration, we performed in situ hybridizations on uninjured, 1, 2 and 3 dpa regenerating hearts using DIG labelled RNA probes. While cox2a expression was observed in CMs at all time points, expression became enriched within the resection injury zone at 2 and 3 dpa (Fig. 2D). This localized signal suggests potential expression in immune, epicardial and/or endocardial cells. Expression of cox2b displayed a more uniform pattern and intensity across the early stages of heart regeneration (Fig. 2E). These signals, however, were absent when heart sections were hybridized with cox2a riboprobe in the absence of an anti-DIG antibody (Fig. 2D) or with anti-DIG independently (Fig. 2E).

Together, these results demonstrate that the zebrafish dynamically responds to cardiac injury by upregulating both cox2a and ptges, two enzymes critical to PGE2 synthesis. Importantly, increased expression of these genes correlates directly with increased levels of PGE2 observed in ventricles subsequent to injury.

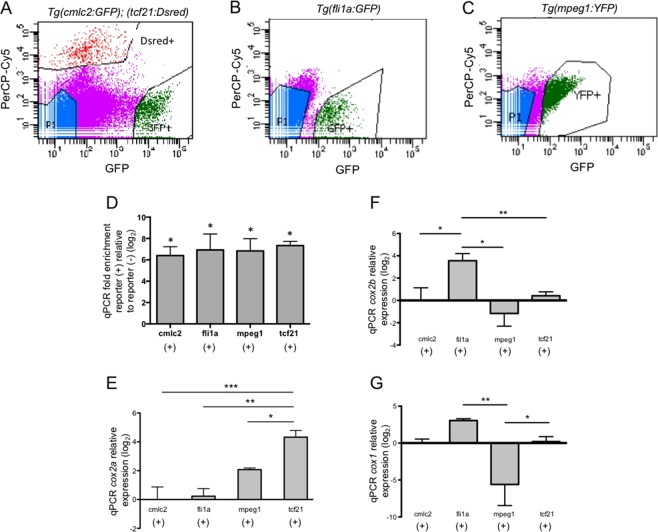

Cox2a expression is highest in epicardial cells at 3 dpa

Multiple cell types contribute to the injury-stimulated production of prostaglandins, the end products of Cox activity. To localize expression of the Cox enzymes in the injured heart, and identify potential sites of PGE2 synthesis, we utilized Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to isolate distinct cell populations for qPCR studies. CMs, epicardial cells, endocardial/endothelial cells, and macrophages were sorted from the dissociated ventricles of Tg(cmlc2:EGFP); (tcf21:DsRed), Tg(fli1a:EGFP), and Tg(mpeg1.YFP) strains, respectively (Fig. 3A–C). Purity of the sorts was validated by qPCR, which revealed a log2 6 to 7-fold enrichment of cell-specific markers in fluorescent(+) vs. fluorescent(−) cells (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Cox2a expression is highest in epicardial cells at 3 dpa. (A–C) Representative FACS dot plots displaying gating parameters used to isolate cells from (A) Tg(cmlc2:EGFP); Tg(tcf21:DsRed), (B) Tg(fli1a:eGFP), (C) Tg(mpeg1:YFP) reporter lines at 3 dpa. (D) qPCR analyses of population specific markers within reporter(+) and reporter(−) cells validate the purity of FACS isolated cells. (mean ± s.e.m. n = 3 biological replicate for each cell type. Student’s t-test *P < 0.05) (E) qPCR studies in 3 dpa FACS sorted cells showed cox2a expression is significantly higher in tcf21(+) cells, relative to all other cell types examined. (F) qPCR of FACS sorted cells showed that at 3 dpa, cox2b expression was significantly higher in fli1a(+) cells relative to all other cell types examined. (G) There was no significant difference in cox1 expression among the resident cardiac cells assayed. cox1 expression in mpeg1(+) cells was significantly lower than that observed in fli1a(+) and tcf21(+) cells. Gene expression was calculated relative to cmlc2(+) cells. (mean = ±s.e.m. n = 2–5 biological replicates; 12–45 pooled ventricles per replicate. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

qPCR analysis showed that at 3 dpa, cox2a expression was lowest in cmlc2(+) CMs and fli1a(+) endocardial/endothelial cells. Relative to cmlc2(+) cells, we observed a trend towards increased levels of cox2a levels in mpeg1(+) macrophages, which have classically been associated with cox2 expression45,46. Unexpectedly, we found cox2a expression was ~log2 2-fold higher in tcf21(+) epicardial cells relative to macrophages (Fig. 3E). Expression of cox2b, which showed a muted response to injury, was highest in fli1a(+) cells (Fig. 3F). There was no significant difference in cox1 expression among the resident cardiac cells assayed; however, Cox1 expression in mpeg1(+) cells was significantly lower than that observed in fli1a(+) and tcf21(+) cells (Fig. 3G). From these studies, we identified tcf21(+) epicardial cells as the primary site of inducible cox2a expression during the early stages of zebrafish heart regeneration.

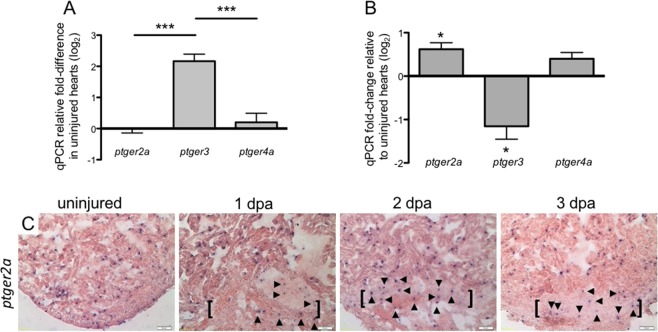

Injury activates a differential shift of PGE2 receptor expression in the heart

Having shown that the zebrafish heart responds to injury by upregulating the expression of cox2a and downstream production of PGE2, we next examined the expression of PGE2 receptors. Mammals express four G protein-coupled PGE2 receptors, EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4. Zebrafish orthologs of the mammalian EP1-4 receptors are Ptger1a, Ptger2a, Ptger3, and Ptger4a, respectively. Examination of receptor expression in the uninjured heart demonstrated that the level of ptger3 was higher by a log2 factor of ~2 relative to both ptger2a and ptger4a (Fig. 4A). Ptger1a was undetected in the ventricles (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Injury activates a differential shift in PGE2 receptor expression in the heart. (A) qPCR determination of PGE2 receptor expression showed that in uninjured hearts, ptger3 levels were significantly higher than ptger2a or ptger4a. Gene expression was calculated relative to ptger2a. (mean ± s.e.m. n = 4–5 biological replicates; 3–5 pooled ventricles per replicate. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ***P < 0.001). (B) Relative to uninjured hearts, expression of ptger2a was significantly upregulated, while ptger3 was significantly downregulated at 3 dpa. (mean ± s.e.m. n = 5 biological replicates; 3–5 pooled ventricles per replicate. Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05). (C) Representative in situ hybridization images of ptger2a expression in uninjured, 1, 2 and 3 dpa hearts. (n = 4 biological replicates, brackets mark approximate amputation zone; arrowheads demarcate signal within the injury zone).

Injury induced a differential shift in receptor expression, and at 3 dpa, ptger2a was upregulated by more than log2 0.6-fold while ptger3 was downregulated by more than log2 1-fold relative to uninjured hearts. We observed no significant change in expression for ptger4a (Fig. 4B). In situ hybridization studies revealed ptger2a expression was similar to the spatial dynamics of cox2a levels. Ptger2a was expressed throughout the heart and enriched within the wounded apex in 1, 2 and 3 dpa hearts (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that in the zebrafish, cardiac injury activates a dynamic shift in PGE2 receptor expression, upregulating the proliferation-associated EP2 ortholog ptger2a, while downregulating the functionally opposing receptor, ptger3.

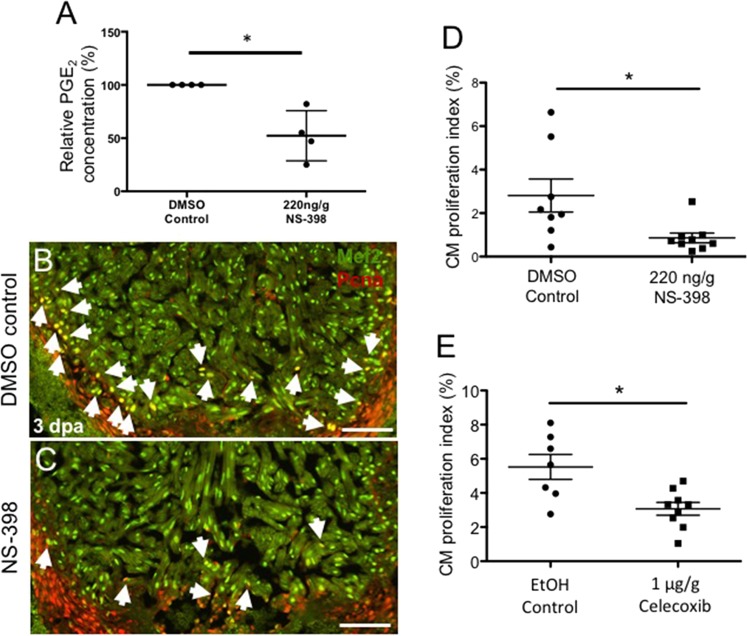

Activation of the Cox2-PGE2 circuit stimulates cardiomyocyte proliferation

PGE2 has been shown to promote cell proliferation in multiple contexts. To better understand the impact of Cox2 activity on PGE2 synthesis and CM proliferation, we subjected animals to ventricular amputation and treated them with either NS-398, a small molecule shown to selectively inhibit Cox2 activity in the zebrafish47, or DMSO control. At 3 dpa, ELISA assays demonstrated that PGE2 concentrations were reduced by more than 47% in NS-398 treated hearts relative to controls (Fig. 5A). To determine effects of suppressed Cox2 activity upon heart regeneration, we quantified CM proliferation indices at 3 dpa, a time during regeneration previously demonstrated to exhibit high levels of proliferative activity48. Immunostaining for Myocyte enhancer factor −2 (Mef2-green), a nuclear CM marker, and Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (Pcna-red), a nuclear marker for proliferating cells, showed that NS-398 treatment suppressed CM proliferation by approximately 70% relative to controls at 3 dpa (Fig. 5B–D). To confirm these findings, we examined the effects of another selective Cox2 inhibitor, Celecoxib. At 3 dpa, Celecoxib treatment also had a significant effect, reducing CM proliferation indices by almost 50% relative to controls (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that, in the injured zebrafish heart, Cox2 activity drives both PGE2 synthesis and CM proliferation during the early stages of heart regeneration.

Figure 5.

Activation of the Cox2-PGE2 circuit stimulates cardiomyocyte proliferation. Zebrafish were subjected to ventricular amputation and treated with daily intraperitoneal (IP) injections of either vehicle control, NS-398 or Celecoxib. Hearts were collected for analysis at 3 dpa. (A) Treatment with NS-398 reduced PGE2 concentrations in ventricles by ~47%, relative to DMSO controls. (mean ± s.e.m. n = 4 biological replicate for each group; 6 pooled ventricles from weight-matched clutch mates per replicate. Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05). (B,C) Representative images of 3 dpa injured hearts treated daily with a DMSO control (B) or NS-398 (C). Hearts were stained with Mef2 (green), and Pcna (red). Mef2+Pcna+ cells mark proliferating CMs, highlighted by white arrows. Scale bars represent 50 μM. (D-E) CM proliferation indices were calculated as a percentage of Mef2(+)Pcna(+) cells relative to the total number of Mef2(+) cells in a defined area adjacent to the injury. (D) CM proliferation was reduced by more than 69% in animals treated with NS-398 when compared to controls. (E) Reduction of CM proliferation was greater than 54% in animals treated daily with Celecoxib, relative to controls. (mean ± s.e.m. n = 7–9 hearts from clutchmates; three sections were quantified per heart and results averaged. Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05).

Discussion

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a potent inflammatory mediator, with pleiotropic effects. In the present study, we have identified a pro-regenerative role for PGE2 during cardiac regeneration in adult zebrafish. After ventricular amputation, the injured zebrafish heart revealed increased levels of PGE2, as well as upregulated expression of cox2a and ptges, two enzymes critical to PGE2 synthesis (Figs. 1, 2). Importantly, pharmacologic inhibition of Cox2 activity suppressed both PGE2 and CM proliferation, supporting a crucial role for the Cox2-PGE2 circuit in initiating the regenerative response (Fig. 5).

In addition to the wound environment, we unexpectedly identified the epicardium as a potential source of inflammation-associated prostaglandin signaling in the regenerating heart. During the inflammatory response, inducible Cox2 has canonically been associated with immune cells recruited to the site of injury, notably macrophages19. However, during conditions of homeostasis, Cox2 is constitutively maintained in some tissues including the vascular endothelium, where it supports the synthesis of prostanoid vasodilators49,50. The zebrafish genome encodes two Cox2 genes, Cox2a and −2b. During regeneration, FACS studies revealed expression of the most inducible Cox enzyme, cox2a, was highest in the epicardium, while more constitutively expressed cox2b was most prominent in endocardial/endothelial cells (Fig. 3). These findings raise the intriguing possibility that Cox2a and Cox2b have divergently evolved in specific tissues, such that Cox2b is expressed in endothelial cells to maintain vascular tone, while in the epicardium, Cox2a facilitates a rapid inflammatory response.

An emerging role for the epicardium as a source of inflammatory signaling has been highlighted in both mammalian and zebrafish models. In mice, epicardial cells were found to be a source of YAP-mediated IFNγ production following myocardial infarction, orchestrating the recruitment of immune-suppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs)11. PGE2 has been implicated in both YAP activation36, and Treg recruitment17, suggesting that in the epicardium, crosstalk between these pathways could mediate the inflammatory response. Our current work supports this study, identifying the epicardium as a potential locus of reparative, inflammatory signaling.

In comparison to our qPCR studies (Figs. 2B and 4B), in situ hybridizations revealed more uniform expression for cox2a, −2b and ptger2a in response to injury (Figs. 2D,E and 4C). One potential explanation for the expression differences observed between these two methodologies is their relative sensitivity. Highly sensitive qPCR assays are more likely to amplify subtle differences in transcript levels, compared to the semi-quantitative nature of in situ hybridizations. Interestingly, we also noted that while in situ studies identified cox2 transcripts in both injury and remote zones of the adult heart, CM proliferation appeared to be limited to the wound area (Fig. 5B). It is possible this localized proliferation may be attributable to additional factors, either related, or unrelated to Cox2 activity, that are spatially restricted during regeneration.

In the downstream PGE2 signaling circuit, we found that PGE2 receptor expression was dynamically modulated in the regenerating heart. PGE2 signals through the autocrine and paracrine activation of four G protein-coupled receptors to initiate diverse downstream pathways. Activation of EP2, the ortholog of zebrafish Ptger2a, directly promotes cell proliferation in the context of regeneration and cancer23,51, polarizing neutrophils and macrophages towards a reparative phenotype18,19. By contrast, EP3, the ortholog of zebrafish Ptger3, appears to activate pathways in opposition to EP2, inhibiting cell proliferation25,26 and exacerbating pathologic inflammation13,52. Our profiling studies of PGE2 receptor expression revealed that injury drives the upregulation of ptger2a and reciprocal downregulation of ptger3 in cardiac tissues (Fig. 4), suggesting that in the zebrafish heart, PGE2 signaling is directed towards a restorative response.

Whether modulation of the PGE2 circuit after injury has an enduring impact on cardiac regeneration remains an open question. Our work showed that in the regenerative zebrafish heart, injury triggers the upregulation of genes critical to PGE2 synthesis (Fig. 2). We furthermore demonstrated that activation of the PGE2 signal is essential to stimulate CM proliferation, a major driver of heart regeneration (Fig. 5).

In other model systems, PGE2 has been shown to directly promote the proliferation of multiple cell types, including skeletal muscle stem cells28 and primary human CMs15. However, a large body of work also supports a role for PGE2 in governing the recruitment, retention, and pro-regenerative polarization of neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells17,18,53. Therefore, it is likely that PGE2 stimulates CM proliferation directly, as well as indirectly, through orchestrating restorative immune cell activity. This study, documenting the injury-induced modulation of PGE2signaling during cardiac regeneration, seeds the field for future research to define the mechanisms through which PGE2 promotes the early, regenerative response.

Acknowledgements

We thank Stephanie Anderson, Ari Dehn, Karlee Markovich, Austin Orecchio and Anne Yu for all zebrafish animal care, Ken Poss for providing the Tg(cmlc2:GFP), Tg(tcf21:Dsred) and Tg(fli1a:GFP) fish, and Lalita Ramakrishnan for sharing the Tg(mpeg1:YFP) reporter strains. William Schott at the Jackson Laboratory provided the technical support for FACS experiments. The Yin laboratory research on heart regeneration is supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20 GM104318, P20 GM103423), the American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (11SDG7210045) and the MacKenzie Foundation (17003).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.F., M.B., D.J.K., T.L.T., and V.P.Y.; Methodology, M.F., M.B., D.J.K., and M.C.L.; Investigation, M.F., M.B., A.M.S., E.G.S., D.J.K. and M.C.L.; Writing - Original Draft, M.F. and V.P.Y.; Writing - Review & Editing, M.F., M.B., A.M.S., E.G.S., D.J.K., M.C.L., T.L.T. and V.P.Y.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Finegold JA, Asaria P, Francis DP. Mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, region, and age: statistics from World Health Organisation and United Nations. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013;168:934–945. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cano-Martinez A, et al. Functional and structural regeneration in the axolotl heart (Ambystoma mexicanum) after partial ventricular amputation. Arch. Cardiol. Mex. 2010;80:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberpriller JO, Oberpriller JC. Response of the adult newt ventricle to injury. J. Exp. Zool. 1974;187:249–253. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401870208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porrello ER, et al. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Sci. 2011;331:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Sci. 2002;298:2188–2190. doi: 10.1126/science.1077857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrassy M, et al. High-mobility group box-1 in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:3216–3226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Y, et al. Cardiac RNA induces inflammatory responses in cardiomyocytes and immune cells via Toll-like receptor 7 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:26688–26698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.661835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horckmans M, et al. Neutrophils orchestrate post-myocardial infarction healing by polarizing macrophages towards a reparative phenotype. Eur. Heart J. 2017;38:187–197. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hossain M, et al. Endothelial LSP1 Modulates Extravascular Neutrophil Chemotaxis by Regulating Nonhematopoietic Vascular PECAM-1 Expression. J. Immunol. 2015;195:2408–2416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahrendorf M, et al. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:3037–3047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramjee V, et al. Epicardial YAP/TAZ orchestrate an immunosuppressive response following myocardial infarction. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:899–911. doi: 10.1172/JCI88759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Preux Charles Anne-Sophie, Bise Thomas, Baier Felix, Marro Jan, Jaźwińska Anna. Distinct effects of inflammation on preconditioning and regeneration of the adult zebrafish heart. Open Biology. 2016;6(7):160102. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han C, et al. Acute inflammation stimulates a regenerative response in the neonatal mouse heart. Cell Res. 2015;25:1137–1151. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang WC, et al. Treatment of Glucocorticoids Inhibited Early Immune Responses and Impaired Cardiac Repair in Adult Zebrafish. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chien PT, Hsieh HL, Chi PL, Yang CM. PAR1-dependent COX-2/PGE2 production contributes to cell proliferation via EP2 receptors in primary human cardiomyocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014;171:4504–4519. doi: 10.1111/bph.12794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsueh YC, Wu JM, Yu CK, Wu KK, Hsieh PC. Prostaglandin E(2) promotes post-infarction cardiomyocyte replenishment by endogenous stem cells. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014;6:496–503. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karavitis J, et al. Regulation of COX2 expression in mouse mammary tumor cells controls bone metastasis and PGE2-induction of regulatory T cell migration. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loynes CA, et al. PGE2 production at sites of tissue injury promotes an anti-inflammatory neutrophil phenotype and determines the outcome of inflammation resolution in vivo. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaar8320. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar8320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu JMF, et al. Prostaglandin E2 Receptor 2 Modulates Macrophage Activity for Cardiac Repair. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009216. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenhough A, et al. The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:377–386. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George RJ, Sturmoski MA, Anant S, Houchen CW. EP4 mediates PGE2 dependent cell survival through the PI3 kinase/AKT pathway. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;83:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parga JA, et al. Prostaglandin EP2 Receptors Mediate Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Neuroprotective Effects on Dopaminergic Neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;55:4763–4776. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0681-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang J, Dingledine R. Role of prostaglandin receptor EP2 in the regulations of cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and inflammation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013;344:360–367. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.200444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh N, et al. COX-2/EP2-EP4/beta-catenin signaling regulates patulin-induced intestinal cell proliferation and inflammation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018;356:224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carboneau BA, et al. Opposing effects of prostaglandin E2 receptors EP3 and EP4 on mouse and human beta-cell survival and proliferation. Mol. Metab. 2017;6:548–559. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konger RL, Brouxhon S, Partillo S, VanBuskirk J, Pentland AP. The EP3 receptor stimulates ceramide and diacylglycerol release and inhibits growth of primary keratinocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 2005;14:914–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2005.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Semmlinger A, et al. EP3 (prostaglandin E2 receptor 3) expression is a prognostic factor for progression-free and overall survival in sporadic breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:431. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho ATV, et al. Prostaglandin E2 is essential for efficacious skeletal muscle stem-cell function, augmenting regeneration and strength. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:6675–6684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705420114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamada T, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 deficiency enhances Th2 immune responses and impairs neutrophil recruitment in hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Immunol. 2008;180:1843–1853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeda-Matsuo Y, et al. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 is a critical factor of stroke-reperfusion injury. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11790–11795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604400103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishizawa N, et al. Inhibition of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 facilitates liver repair after hepatic injury in mice. J. Hepatol. 2018;69:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattila S, Tuominen H, Koivukangas J, Stenback F. The terminal prostaglandin synthases mPGES-1, mPGES-2, and cPGES are all overexpressed in human gliomas. Neuropathology. 2009;29:156–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2008.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sano H, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3785–3789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tucker O, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is up-regulated in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;Mar 1:987–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshimatsu K, et al. Inducible microsomal prostaglandin E synthase is overexpressed in colorectal adenomas and cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7:3971–3976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim HB, et al. Prostaglandin E2 Activates YAP and a Positive-Signaling Loop to Promote Colon Regeneration After Colitis but Also Carcinogenesis in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:616–630. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burns CG, et al. High-throughput assay for small molecules that modulate zebrafish embryonic heart rate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:263–264. doi: 10.1038/nchembio732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kikuchi K, et al. tcf21+ epicardial cells adopt non-myocardial fates during zebrafish heart development and regeneration. Dev. 2011;138:2895–2902. doi: 10.1242/dev.067041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawson ND, Weinstein BM. In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 2002;248:307–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roca FJ, Ramakrishnan L. TNF dually mediates resistance and susceptibility to mycobacteria via mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell. 2013;153:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lepilina A, et al. A dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell. 2006;127:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao J, et al. Single epicardial cell transcriptome sequencing identifies Caveolin 1 as an essential factor in zebrafish heart regeneration. Dev. 2016;143:232–243. doi: 10.1242/dev.130534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishikawa TO, Griffin KJ, Banerjee U, Herschman HR. The zebrafish genome contains two inducible, functional cyclooxygenase-2 genes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;352:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pini B, et al. Prostaglandin E synthases in zebrafish. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005;25:315–320. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000152355.97808.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russell SW, Pace JL. Both the kind and magnitude of stimulus are important in overcoming the negative regulation of macrophage activation by PGE2. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1984;35:291–301. doi: 10.1002/jlb.35.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dubois RN, et al. Cyclooxygenase in biology and disease. FASEB J. 1998;12:1063–1073. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.12.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grosser T, Yusuff S, Cheskis E, Pack MA, FitzGerald GA. Developmental expression of functional cyclooxygenases in zebrafish. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112217799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beauchemin M, Smith A, Yin VP. Dynamic microRNA-101a and Fosab expression controls zebrafish heart regeneration. Dev. 2015;142:4026–4037. doi: 10.1242/dev.126649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 49.Hristovska AM, et al. Prostaglandin E2 induces vascular relaxation by E-prostanoid 4 receptor-mediated activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Hypertension. 2007;50:525–530. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.088948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russell-Puleri S, et al. Fluid shear stress induces upregulation of COX-2 and PGI2 release in endothelial cells via a pathway involving PECAM-1, PI3K, FAK, and p38. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017;312:H485–H500. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00035.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otsuka S, et al. PGE2 signal via EP2 receptors evoked by a selective agonist enhances regeneration of injured articular cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2009;17:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morimoto K, et al. Prostaglandin E2-EP3 signaling induces inflammatory swelling by mast cell activation. J. Immunol. 2014;192:1130–1137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang L, et al. Chlorogenic acid methyl ester exerts strong anti-inflammatory effects via inhibiting the COX-2/NLRP3/NF-kappaB pathway. Food Funct. 2018;9:6155–6164. doi: 10.1039/c8fo01281d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]