Abstract

We assessed whether early implementation of Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion and state health insurance exchanges increased access to mental health and substance use treatment among those in need and whether these changes differed by racial/ethnic group. We found that mental health treatment rates increased significantly but found no evidence of a reduction in the wide racial/ethnic disparities in mental health treatment that preceded ACA expansion from 2005 to 2013.

A core purpose of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is to improve access to health care by expanding health insurance coverage. Two overlapping groups in particular have been expected to benefit: racial/ethnic minorities and people with behavioral health conditions.1,2 Preliminary assessments have shown overall increases in coverage and some evidence that racial/ethnic disparities in coverage have been reduced.3,4 It remains unclear, however, whether coverage expansion has led to improvements for racial/ethnic minority groups that have historically lagged far behind in access to behavioral health treatment.5,6

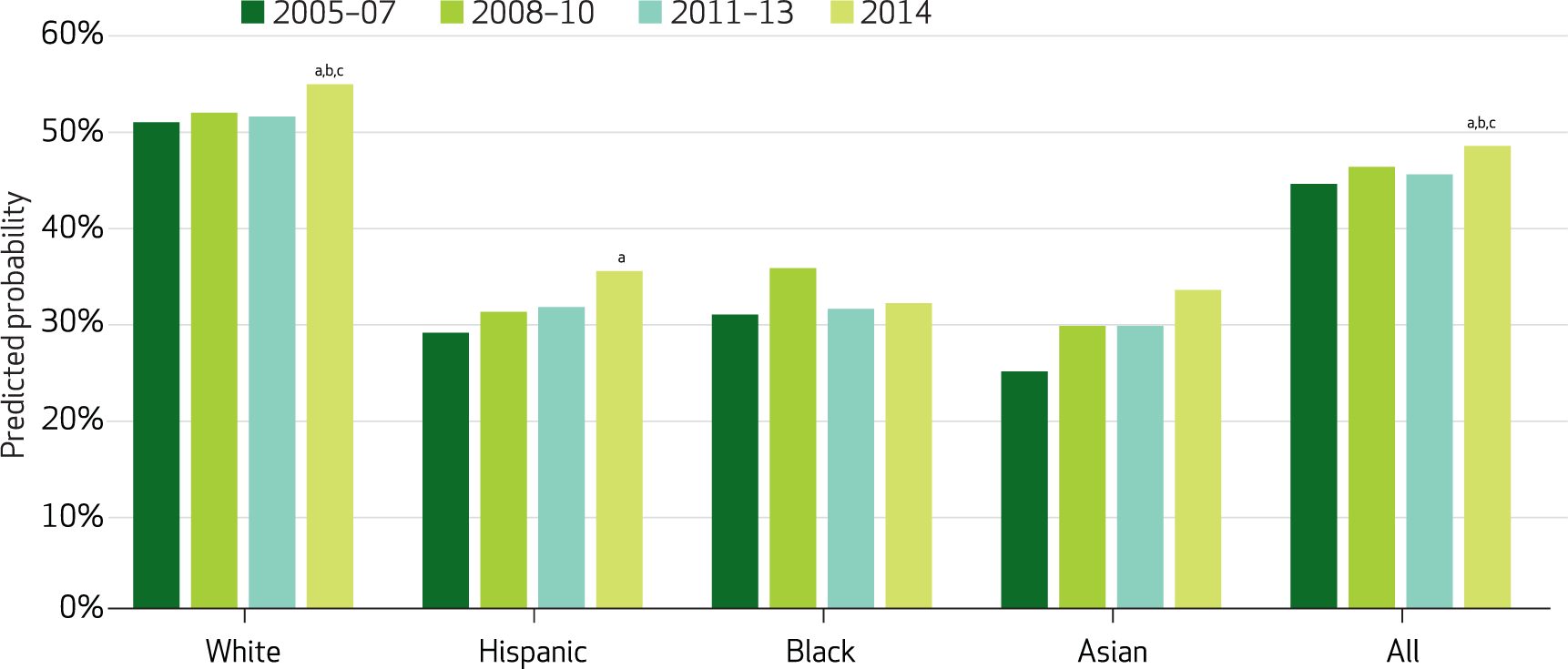

In this analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, we found that mental health treatment rates increased significantly among people with serious psychological distress in 2014, when ACA-driven Medicaid expansion and private insurance exchanges were initiated. Despite the expansion of treatment rates in 2014, though, there was no evidence of reduction in the wide racial/ethnic disparities in mental health treatment access that had persisted throughout 2005–13 (Exhibit 1).

EXHIBIT 1. Any past-year mental health treatment among people with past-year serious psychological distress.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2005–14. NOTES Predicted probabilities generated from difference-in-differences regression model adjusting for age, sex, marital status, and self-reported health status. Unweighted n = 54, 575. aSignificantly different from 2005–07 (p < 0.05). bSignificantly different from 2008–10 (p < 0.05). cSignificantly different from 2011–13 (p < 0.05).

The ACA has been expected to improve access to behavioral health care in at least three ways. First, private health insurance exchanges with premium subsidies were established to make insurance more accessible to individuals and families who do not have employer-based coverage. Second, Medicaid expansion was designed to increase enrollment by raising the income threshold and eliminating other qualifications not related to income. Third, the ACA extended provisions of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, mandating parity between behavioral health and general medical insurance benefits across most sources of insurance coverage.7

In 2014, however, multiple factors might have attenuated the potential for the ACA to improve insurance coverage and access to behavioral health care—factors that might have disproportionately affected racial/ethnic minorities. First, insurance exchanges experienced technical problems that complicated the sign-up process and delayed enrollment for millions of Americans. Second, a 2012 US Supreme Court decision made Medicaid expansion voluntary, and many states chose not to expand their programs. States that did not expand Medicaid had larger populations of lower-income racial/ethnic minorities compared to states that did expand.8 Third, people are generally unfamiliar with the health care benefits their insurance policies include,9 so while millions of Americans might have gained new behavioral health coverage in 2014, many of them were likely unaware of the change. Finally, other factors such as the stigma surrounding behavioral health care among racial/ethnic minority groups10 and a combination of overall shortages and an uneven distribution of behavioral health providers11 were not addressed by the ACA and were likely to continue limiting the uptake of treatment in 2014.

In this study we used newly released, nationally representative survey data to examine changes in racial/ethnic disparities in behavioral health treatment access and insurance coverage associated with the implementation of major ACA provisions in 2014. We estimated mental health and substance use disorder treatment rates separately and assessed how often cost and insurance problems were cited as reasons for not receiving needed behavioral health care.

Study Data And Methods

The data source was the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a nationally representative, annual survey of drug and alcohol use behaviors, mental health status, and behavioral health treatment among the civilian noninstitutionalized US population age twelve or older.12 We used ten annual cross-sections, split into four time periods (2005–07, 2008–10, 2011–13, and 2014) to measure trends leading up to the 2014 implementation of ACA insurance reforms.

Our study sample comprised survey respondents with the following characteristics. First, they were ages 18–64 (the age range most likely to be affected by ACA-based insurance expansion). Second, they had experienced serious psychological distress in the past year, based on a score of 13 or higher on the Kessler-6 Scale,13 which measures level of psychological distress, or they met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-4), criteria for a past-year drug or alcohol use disorder, or both.

We assessed four sets of outcomes: past-year receipt of mental health treatment (inpatient, outpatient, or pharmacy) among those with serious psychological distress (n = 54, 575); past-year substance use treatment among those with a diagnosis of a substance use disorder (n = 52, 258); treatment barriers (cost, lack of insurance, or inadequate insurance) among respondents who self-identified a need for care but did not receive it (n = 25, 080); and insurance coverage (any source, any Medicaid, or any nongroup private coverage) among people diagnosed with serious psychological distress or a substance use disorder (n = 91, 186).

To compare outcomes for racial/ethnic groups, we considered the four largest self-identified racial/ethnic categories: non-Hispanic white, Hispanic or Latino, non-Hispanic black or African American, and non-Hispanic Asian. Other racial/ethnic categories were excluded because of small sample sizes.

We fitted difference-in-differences models to estimate racial/ethnic differences in 2014 compared to racial/ethnic differences in the three pre-ACA implementation time periods. These pre-ACA comparison groups accounted for shifting baseline conditions, measuring secular trends in health policy and the broader economy. In each model, we controlled for age, sex, marital status, and self-reported overall health status. To implement the Institute of Medicine (IOM) definition of health care disparity,14 we did not adjust for socioeconomic status measures such as education, employment, and income. Racial/ethnic differences attributable to these socioeconomic status factors then became part of the disparity estimation.

We estimated logit regressions and computed predicted probabilities by race/ethnicity and time for each model. Estimates and standard errors of differences and differences-in-differences were calculated using sampling weights and variance estimation variables to account for the complex survey design and to make results nationally representative.

Study Results

MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT RATES

Among those meeting criteria for serious psychological distress in the past year, survey respondents in 2014 were significantly more likely (p < 0.05) to receive mental health treatment than respondents in any of the pre-2014 comparison periods (Exhibit 1). Whites received mental health care more frequently in 2014 than any of the pre-2014 comparison periods. Racial/ethnic minority respondents continued to receive treatment at substantially lower rates than whites. None of the racial/ethnic minority respondents in 2014 received significantly more mental health treatment (p < 0.05) than their same-minority-group counterparts in the pre-2014 comparison periods with the exception that 2014 Hispanics received significantly more care than 2005–07 Hispanic respondents (p < 0.05). There was no significant narrowing of racial/ethnic disparities over time in mental health service access.

DRUG AND ALCOHOL TREATMENT RATES

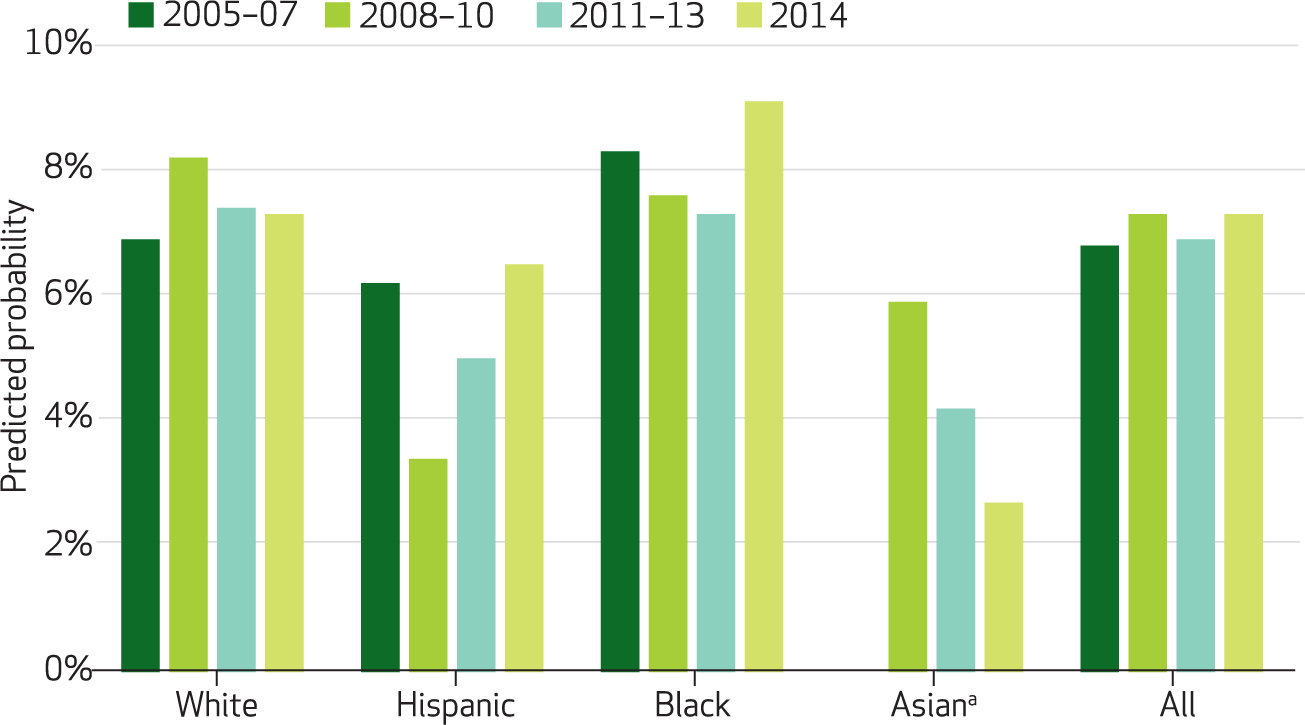

Among individuals meeting criteria for past-year substance use disorders, specialty drug and alcohol treatment rates did not change significantly for 2014 survey respondents compared to those in any of the pre-2014 periods (Exhibit 2). Treatment rates remained consistently low (averaging about 7 percent) throughout the entire ten-year span between 2005 and 2014 for all racial/ethnic groups studied.

EXHIBIT 2. Any past-year specialty substance use disorder treatment among people with past-year substance use disorders.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2005–14. NOTES Predicted probabilities generated from difference-in-differences regression model adjusting for age, sex, marital status, and self-reported health status. Unweighted n = 52, 258. aEstimate of rate for Asians in 2005–07 omitted because of insufficient cell size.

BARRIERS TO CARE

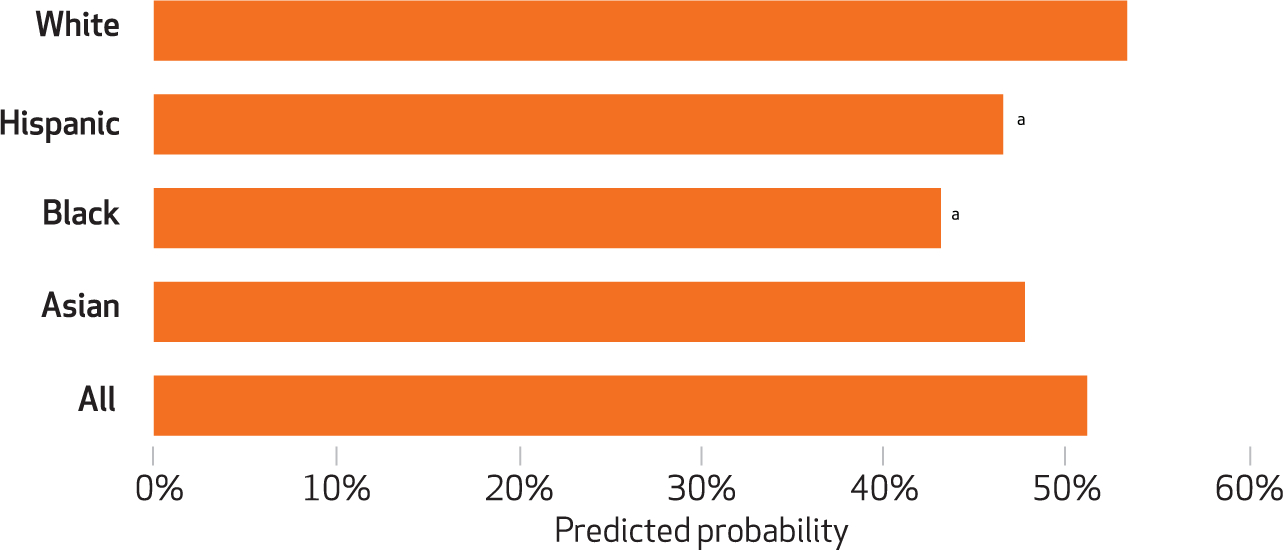

Among people who needed mental health care but did not receive it, the cost of care, no insurance, or inadequate insurance were cited as causes by approximately half of those with unmet need (between 44 percent and 54 percent, depending on racial/ethnic group). Whites were significantly more likely (p < 0.05) to cite at least one of these barriers than blacks or Hispanics (Exhibit 3). These rates and differences did not change significantly in 2014, compared to pre-ACA time periods (data available upon request).

EXHIBIT 3. Prevalence of cost and insurance problems as reasons for unmet mental health treatment need, 2014.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2014. NOTES Predicted probabilities generated from difference-in-differences regression model adjusting for age, sex, marital status, and self-reported health status. Unweighted n = 25, 080. aSignificantly different from non-Hispanic whites (p < 0.05).

INSURANCE COVERAGE

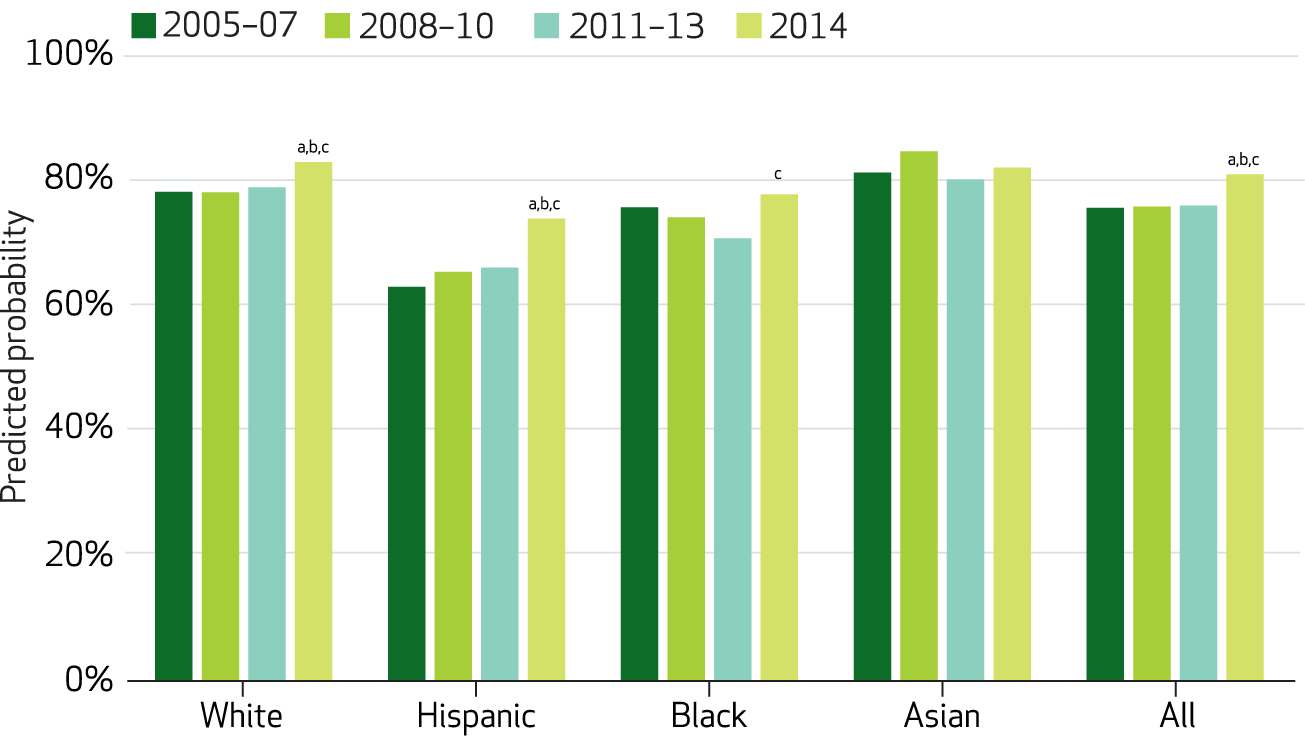

For 2014 respondents with serious psychological distress or substance use disorders, the estimated rate of any insurance coverage was about 81.5 percent—a significant increase (p < 0.05) over all pre-2014 time periods (Exhibit 4). Hispanic and black respondents in 2014 were more likely to be insured than their 2011–13 counterparts, but disparities in insurance coverage relative to whites were not reduced. Among blacks, the coverage rate rose to 78.3 percent in 2014. This appeared to reverse a negative pre-ACA trend and represented a 10 percent relative increase after nine years of consistent decline (Exhibit 4).

EXHIBIT 4. Any health insurance coverage among people meeting criteria for substance use disorders or serious psychological distress.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2005–14. NOTES Predicted probabilities generated from difference-in-differences regression model adjusting for age, sex, marital status, and self-reported health status. Unweighted n = 91, 186. aSignificantly different from 2005–07 (p < 0.05). bSignificantly different from 2008–10 (p < 0.05). cSignificantly different from 2011–13 (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Compared to 2005–13, significant increases in mental health treatment were realized in 2014 as ACA-mandated insurance expansion took place. This might serve as preliminary evidence that the combination of expanded insurance coverage and laws mandating parity in behavioral health coverage increased the accessibility of mental health care for those with serious psychological distress.

While there were increases in mental health treatment for Hispanics and Asians, our results show that these increases were not significantly greater than what was to be expected given prior trends in mental health treatment for these groups. For blacks, no increases were identified in mental health care access in 2014.

No changes in substance use treatment among people with substance use disorders were observed despite the gains in insurance coverage for this population. This finding indicates that substance use disorder treatment continues to be somewhat of an outlier, responding against expectations and differently than mental health treatment.

Interpretation of our findings with regard to behavioral health treatment rates requires caution. Respondents of the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health reported on past-year receipt of treatment. Depending on when in 2014 they were surveyed, the treatment they reported receiving might have taken place in 2013. The increase in mental health treatment and the lack of change in substance use treatment might thus be considered conservative measures of the first-year impact of the ACA.

In addition, 2014 alone was not likely to have been a long enough period to judge the full effect of ACA insurance expansion. There might have been a lagged effect, with many newly insured individuals requiring additional time to identify a need for care, find a provider, and determine what their new insurance covered. Another limitation was that while the difference-in-differences design protected against possible confounding when estimating change in disparities, the overall increase in mental health treatment access might have reflected a break in trend as a result of other, unobserved factors in 2014 instead of a causal effect of the ACA insurance reforms.

Our health insurance findings demonstrate that substantial gains in insurance coverage were realized for people with recent behavioral health conditions. However, we found that unlike in the general population, there was no narrowing of racial/ethnic insurance disparities in this subgroup. To be sure, significant gains did appear to take place for all racial/ethnic groups in this subpopulation, but minorities did not make up ground compared to whites.

Conclusion

Our analysis reveals a lack of congruence between patterns of insurance coverage and patterns of access to care. Although whites, blacks, and Hispanics alike experienced coverage gains in 2014, only whites and Hispanics saw corresponding increases in mental health treatment. While coverage increased for blacks at least as much as it did for whites, the mental health treatment rate for blacks remained flat in 2014. And despite clear coverage gains across multiple racial/ethnic groups, in no case did treatment rates for substance use disorders increase. This suggests that gains in insurance coverage alone are not likely to push forward meaningful reductions in mental health treatment disparities or increase consistently low overall substance use treatment rates. Without focusing further attention on the unique access barriers confronting racial/ethnic minorities, disparities and overall low levels of behavioral health treatment access are likely to persist. This includes targeting interventions to address the stigma surrounding behavioral health care and the scarcity of behavioral health care providers available to racial/ethnic minorities.▪

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant No. R01HS021486). The authors thank Naysha Shahid for her research assistance.

Contributor Information

Timothy B. Creedon, Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University, in Waltham, Massachusetts, and a research associate at the Health Equity Research Lab, Cambridge Health Alliance, in Cambridge, Massachusetts..

Benjamin Lê Cook, Health Equity Research Lab at Cambridge Health Alliance and an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, in Boston..

NOTES

- 1.Clemans-Cope L, Kenney GM, Buettgens M, Carroll C, Blavin F. The Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansions will reduce differences in uninsurance rates by race and ethnicity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012; 31(5):920–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry CL, Huskamp HA. Moving beyond parity—mental health and addiction care under the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):973–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMorrow S, Long SK, Kenney GM, Anderson N. Uninsurance disparities have narrowed for black and Hispanic adults under the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1774–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommers BD, Musco T, Finegold K, Gunja MZ, Burke A, McDowell AM. Health reform and changes in health insurance coverage in 2014. N Engl J. Med 2014;371(9):867–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook BL, Zuvekas S, Carson N, Wayne GF, Vesper A, McGuire TG. Assessing racial/ethnic disparities in treatment across episodes of mental health care. Health Serv Res. 2014; 49(1):206–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manseau M, Case BG. Racial-ethnic disparities in outpatient mental health visits to U.S. physicians, 1993–2008. Psychiatr Serv. 2014; 65(1):59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beronio K, Glied S, Frank R. How the Affordable Care Act and Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act greatly expand coverage of behavioral health care. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2014;41(4):410–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garfield R, Damico A. The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid—an update [Internet].Washington (DC): Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2016. January 21 [cited 2016 Apr 8]. Available from: http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid-an-update/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Braun B, Williams AD, Understanding health insurance literacy: a literature review. Fam Consum Sci Res J. 2013;42(1):3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leong FT, Lau AS. Barriers to providing effective mental health services to Asian Americans. Ment Health Serv Res. 2001;3(4):201–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Holzer CE, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10): 1323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: methodological summary and definitions [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. [cited 2016 Apr 8]. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs2014/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs2014.htm [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6): 959–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook BL, McGuire TG, Zaslavsky AM. Measuring racial/ethnic disparities in health care: methods and practical issues. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 Pt 2):1232–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]