Introduction

Darier disease (DD) is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatosis with high penetrance and variable expressivity. This acantholytic dermatosis is caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene, which encodes the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase isoform 2, resulting in a loss of interkeratinocyte cohesion and abnormalities in the differentiation of keratinocytes.1 This dysfunction of the cutaneous barrier is clinically characterized by multiple, discrete, scaly, crusted papules mainly in seborrheic and flexural areas, associated with severe pruritus and often pain. The cutaneous lesions can flare following viral or bacterial infection, high stress, or humidity. The impact of DD on quality of life is significant and may lead to depression or suicide. The avoidance of triggers such as friction, heat, and high sun exposure should be proposed to prevent exacerbation of the disease. Topical therapies such as antibacterial soaps, antibiotics, antifungals, salicylic acid, retinoids, and topical corticosteroids can also be used to control disease flare-ups. In recalcitrant cases, therapeutic options remain limited.2

Case report

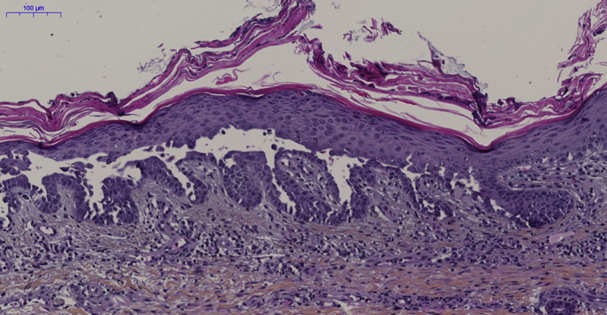

A 54-year-old man was referred for DD present since childhood associated with ichthyosis vulgaris (Fig 1, A). The patient had no known family history of DD. He presented with crusted pruritic papules coalescing into large foul-smelling plaques. Hematoxylin-eosin examination found acantholytic dyskeratosis (Fig 2). Direct immunofluorescence analysis was noncontributory. No serum anti-intercellular substance antibodies were found. For several years, he had received topical corticosteroids or topical 5-fluorouracil, without improvement despite good compliance.

Fig 1.

A, Darier disease before intravenous immunoglobulins. B, Improvement after 4 infusions of immunoglobulins, 0.4 g/kg every 3 weeks.

Fig 2.

Skin biopsy on trunk. Hematoxylin-eosin staining shows hyperkeratosis, suprabasal acantholysis and clefts, and dermal mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. (Original magnification: ×12.)

Given the severe course of the disease with disabling and erythrodermic flare-ups, acitretin, 0.3 mg/kg/d was initiated but discontinued after 3 months owing to lack of efficacy. Then, in view of our previous experience using intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) in Netherton syndrome (NS), a condition that serves as an appropriate analogue to DD because of the presence of skin barrier abnormalities associated with bacterial infections, we decided to initiate IVIg at a substitutive dose (0.4 g/kg every 3 weeks). After 4 infusions, the patient improved significantly (Fig 1, B) with healing of the crusted lesions and reduced itching. The interval between infusions had to be maintained at 3 weeks owing to moderate relapses localized on the flank when infusions were administered every 4 to 6 weeks. The clinical response has continued for the last 2 years.

Discussion

The use of IVIg is now well established in several chronic inflammatory skin conditions.3 A dose of 2 g/kg is used to obtain an immunomodulatory mechanism of action including blockade of Fc receptors on phagocytes, inhibition of complement deposition, modulation of cytokine production, neutralization of circulating autoantibodies, and down-regulation of autoantibody production by anti-idiotypic antibodies interacting with B cells.

More recently, IVIg has shown its efficacy in the management of NS, as shown by several cases published in the literature including one in our department.4,5 NS is caused by a mutation in SPINK5, encoding the serine protease inhibitor LEKT1 and leading to a major alteration of the stratum corneum. NS is characterized by congenital ichthyosis, bamboo hair, and chronic skin inflammation with atopic diathesis.6 As in DD, patients have skin barrier abnormalities leading to recurrent skin infections, mostly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, causing flare-ups of the disease. More recently, NS was also found to be associated with abnormal antibody responses and a reduced number of circulating memory B cells, supporting the use of IVIg in NS.5 The clinical efficacy of IVIg in NS could be because of the restoration of an antibody immune response and a reduction in skin inflammation, which is known to potentiate the defect in skin barrier integrity, as in atopic dermatitis.7 IVIg used as replacement therapy at the dose of 0.4 g/kg/mo led to clinical improvement in cutaneous inflammation and pruritus and robustness of hair.

Because DD, like NS, is also associated with local bacterial infection and skin barrier abnormalities, we tested the use of IVIg in this recalcitrant case of DD and found that it led to dramatic improvement. We hypothesized that IVIg in DD patients might also dampen the skin inflammation and improve immune response against skin infections, thereby leading to fewer flare-ups and to clinical improvement. To our knowledge, this is the first case of severe DD treated effectively with IVIg.

Besides having an immunomodulatory effect, IVIg might also control the skin barrier function. IVIg could be an effective therapy for DD patients who do not respond to or are intolerant to topical agents and systemic retinoids and maybe for dermatoses with epidermal barrier failure presenting with severe erythrodermic manifestations. However, the mechanisms of action of IVIg and the best dose and schedule need further investigation.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.Celli A., Mackenzie D.S., Zhai Y. SERCA2-controlled Ca2+-dependent keratinocyte adhesion and differentiation is mediated via the sphingolipid pathway: a therapeutic target for Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(4):1188–1195. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engin B., Kutlubay Z., Erkan E., Tüzün Y. Darier disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33(4):448–451. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forbat E., Ali F., Al-Niaimi F. Intravenous immunoglobulins in dermatology. Part 2: clinical indications and outcomes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(6):659–666. doi: 10.1111/ced.13552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Small A.M., Cordoro K.M. Netherton syndrome mimicking pustular psoriasis: clinical implications and response to intravenous immunoglobulin. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(3):e222–e223. doi: 10.1111/pde.12856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renner E.D., Hartl D., Rylaarsdam S. Comèl-Netherton syndrome defined as primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2009;124(3):536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hovnanian A. Netherton syndrome: skin inflammation and allergy by loss of protease inhibition. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;351(2):289–300. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1558-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pellerin L., Henry J., Hsu C.-Y. Defects of filaggrin-like proteins in both lesional and nonlesional atopic skin. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2013;131(4):1094–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]