Abstract

The ability of organisms to sense and adapt to oxygen levels in their environment leads to changes in cellular phenotypes, including biofilm formation and virulence. Globin coupled sensors (GCSs) are a family of heme proteins that regulate diverse functions in response to O2 levels, including modulating synthesis of cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP), a bacterial second messenger that regulates biofilm formation. While GCS proteins have been demonstrated to regulate O2-dependent pathways, the mechanism by which the O2 binding event is transmitted from the globin domain to the cyclase domain is unknown. Using chemical cross-linking and subsequent liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, diguanylate cyclase (DGC)-containing GCS proteins from Bordetella pertussis (BpeGReg) and Pectobacterium carotovorum (PccGCS) have been demonstrated to form direct interactions between the globin domain and a middle domain π-helix. Additionally, mutation of the π-helix caused major changes in oligomerization and loss of DGC activity. Furthermore, results from assays with isolated globin and DGC domains found that DGC activity is affected by the cognate globin domain, indicating unique interactions between output domain and cognate globin sensor. Based on these studies a compact GCS structure, which depends on the middle domain π-helix for orienting the three domains, is needed for DGC activity and allows for direct sensor domain interactions with both middle and output domains to transmit the O2 binding signal. The insights from the present study improve our understanding of DGC regulation and provide insight into GCS signaling that may lead to the ability to rationally control O2-dependent GCS activity.

Keywords: diguanylate cyclase, globin, heme, oxygen sensing, signaling protein

Introduction

Since the discovery of cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) as a bacterial second messenger and its effects on biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance, the proteins involved in c-di-GMP pathways have been of considerable interest as possible targets for the development of new antibiotics [1–4]. To date, conserved motifs for the enzymes responsible for c-di-GMP production (diguanylate cyclase; GGDEF) and c-di-GMP hydrolysis (c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase; EAL or HDGYP) have been identified, allowing for relatively facile identification of bacteria that utilize c-di-GMP signaling to control cellular phenotypes [5,6]. However, our understanding of how c-di-GMP metabolic enzymes are regulated and how bacteria obtain disparate downstream effects from activation of different diguanylate cyclases is incomplete. In particular, the molecular mechanisms by which environmental signals regulate c-di-GMP production remain poorly understood, despite the importance of this information for both understanding signal-specific c-di-GMP signaling and designing anti-biofilm agents [6–8].

Oxygen (O2) levels have been demonstrated to regulate biofilm formation and to affect virulence, making it an important external signal, likely due to its importance in metabolism [9–11]. Globin coupled sensor (GCS) proteins utilize a heme-containing globin domain to sense O2 levels and transmit the ligand-binding signal through a linking middle domain to an output domain. GCS proteins have been identified in numerous bacteria with a variety of output domains that are regulated by the O2-binding signal, including methyl accepting chemotaxis protein (MCP), kinase, and diguanylate cyclase (DGC) [12,13]. In Bacillus subtilis, the MCP-containing GCS regulates aerotaxis, allowing the organism to move to its preferred location within an O2 gradient [14]. In contrast, the DGC-containing GCS from the plant pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum (PccGCS) regulates O2-dependent motility, virulence factor production, and rotting within a plant host, highlighting the importance of O2 sensing and GCS proteins in controlling bacterial phenotypes [11].

Within the GCS protein family, the most common effect of O2 binding to the heme of the globin domain is an increase in the activity of the output domain [13]. This increase in GCS enzymatic activity often requires oligomerization of GCS monomers to yield activity of the output domains; GCS proteins with diguanylate cyclase, histidine kinase, and adenylate cylcase output domains have been shown to function as homodimers and higher order oligomers [15–20]. Because of the multi-domain organization and oligomerization of GCS proteins, questions have arisen regarding the overall structure and path of signal transduction within the protein family. A number of studies have focused on elucidating the structure of GCS proteins, but to date, high resolution structural information is only available for isolated domains. Sensor globin domains from HemAT-Bs (MCP-GCS from B. subtilis), AfGcHK (kinase-GCS from Anaeromyxobacter sp. FW109-5), EcDosC (DGC-GCS from E. coli), and BpeGReg (DGC-GCS from Bordetella pertussis) [21] have been crystallized as dimers in different ligation states (FeII, FeII-CO, FeIII-CN, FeII-O2, FeIII-H2O) and have highlighted some conformational changes within the globin domain that might be involved in signal transduction [22–24]. These include displacement of the globin monomers relative to each other, changes in helix flexibility (as evidenced by B factors), and subtle changes in heme pocket conformation. Structures of the isolated middle and DGC domains from EcDosC have provided additional insights [24]. The middle domain was demonstrated to adopt a four-helix bundle architecture containing a short π-helix and to form a dimer in the crystal structure, suggesting a possible dimeric configuration within the full-length protein. In addition, one crystal form of the DGC domain formed a dimer with the product inhibitory sites (I-sites) near the dimer interface, highlighting a potential mechanism by which the DGC domain could exert the product inhibition observed in enzymatic assays.

Despite the insights gained from individual domain structures, these structures have not provided detailed information regarding transfer of the O2-binding signal from the globin domain to the output domain. In a study of AfGcHK (kinase-containing GCS), which is dimeric, hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) was used to determine regions within the GCS that might undergo ligand-dependent conformational changes. The HDX-MS data indicated that the distal side of the heme pocket of the globin domain, the region of the peptide backbone that interacts with gaseous ligands, was very flexible and thus probably involved in signal transmission by globin conformational changes [17]. However, investigations of full-length EcDosC demonstrated that it exists as a homodimer with a somewhat elongated shape and, based on charge complementarity analysis, was proposed to adopt a conformation with the globin domains orientated at one end of the middle domain dimer through flexible linkers and the DGC dimer connected through small loops at the other end of the middle domain dimer. This proposed model would suggest that the distal heme pocket would have to propagate the ligand binding signal through rearrangements of the middle domain, as this model does not predict interaction between the globin and DGC domains [24].

In the present study, we have used alternative methods to gain insights into the signal transmission between domains of two previously studied DGC-containing GCSs, PccGCS from Pectobacterium carotovorum and BpeGReg from Bordetella pertussis [15,25]. BpeGReg and PccGCS have been chosen for analysis due to the previously reported ligand binding and enzyme kinetic characterizations [15,25], as well as the finding that PccGCS signaling controls O2-dependent soft rot infections of crop plants [11]. First, chemical cross-linking followed by protease digestion and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis was used to identify interactions between domains within the two DGC-containing GCS proteins. Next, influenced by the cross-linking results and previous BpeGReg mutation studies by Wan and others [9,10], conserved histidine and lysine residues within a π-helical region of the middle domain were mutated in PccGCS, and this mutant was compared biochemically and biophysically to the wild-type form to show that the π-helix mutations do affect DGC activity. Furthermore, enzyme kinetic assays utilizing isolated diguanylate cyclase and globin domains of PccGCS revealed enhanced activity due to specific interactions of the cognate globin domain. Finally, the globin domain from BpeGReg was used to probe the specificity of globin–DGC interactions. The results reported herein suggest an approximate quaternary structure that is needed for these DGC GCSs to function. The middle domain π-helix appears to be required for the proper quaternary structure formation and, based on PccGCS, the globin domain makes contacts with the DGC domain that can affect DGC activity. The present study provides an improved understanding of the structure of DGC GCSs and the mechanism of output domain regulation within DGC GCSs.

Materials and methods

Gene cloning

Full-length PccGCS and BpeGReg and PccGlobin and BpeGlobin constructs were cloned previously into vector pET20b [25,26]. PccGCS H237A/K238A was created through site directed mutagenesis by PCR. Site-directed mutagenesis primers were 5′-TGGTTCAACGCGGCGGGTAAGTCATCGTTCAGCAATATC-3′ (Forward) and 5′-TGACTTACCCGCCGCGTTGAACCACAGGCCAAATTCGGA-3′ (Reverse). The MBP-PccDGC construct was created using the vector pMAL-c2x (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). A his-tag (5′-ATGCATCATCATCATCATCATCACCTGAAAATCGAAGAAGGTCATCATCATCATCATCACCTG-3′) replaced the original start codon, and a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site (ENLYFQS (5′-GAGAACCTGTACTTCCAGTCA-3′)) was inserted between the Factor Xa cleavage site and EcoRI restriction site to create vector pHis-MBP. Using polymerase incomplete primer extension (PIPE) cloning [27], an Escherichia coli codon-optimized DNA sequence for residues #321 – 470 (N- LPTILRHE….EYAQEE -C) of PccGCS (DGC domain) was inserted into the multiple cloning site using four primers to create pHis-MBP-PccDGC. The primers used to amplify pHis-MBP were 5′-CAGTCAGAATTCGGATCCTCTGGCCTGCCGACCATCCTGCGCCATGAA-3′ (Forward) and 5′-CGTTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGCCAAGCTTTTATTCTTCTTGAGCGTATTCAAT-3′ (Reverse). The primers used to amplify the DGC domain from pET20b-PccGCS were 5′-CTGCCGACCATCCTGCGCCATGAAATTTCACTGGCG-3′ (Forward) and 5′-GATGGTCGGCAGGCGACCTTCGATGTGGTGGTGGTG-3′ (Reverse).

Protein expression and purification

The expressions and purifications of full-length PccGCS (WT and H237A/K238A) and BpeGReg and PccGlobin and BpeGlobin constructs were conducted as previously described [25,26]. Plasmid pHis-MBP-PccDGC was transformed into E. coli strain C41(DE3) pLysS (Lucigen, Middleton, WI) and MBP-PccDGC expression was carried out by inducing cells at OD600 ∼ 0.6–0.8 with 100 μM IPTG for ∼20 h at 20°C with expression media containing 45 g/l yeast extract, 1% glycerol (v/v), 1.6 g KH2PO4 and 6.27 g K2HPO4 per liter. Buffer A (50 mM Tris pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol (v/v), 20 mM imidazole) was used to resuspend MBP-PccDGC cell pellets, and cell lysis was completed using a homogenizer at 4°C (Avestin, Inc., Ontario, Canada). After centrifugation at 130,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h (Beckman Optima L-90X ultracentrifuge), the supernatant was loaded onto a Buffer A pre-equilibrated column containing HisPur Ni resin (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Bound protein was eluted with Buffer B (50 mM Tris pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol (v/v), 250 mM imidazole) and buffer-exchanged/desalted with Buffer C (50 mM Tris pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol (v/v), 1 mM DTT) on a S200 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). The collected protein was concentrated (Vivaspin 10 kDa MWCO centrifugal concentrators; Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany), flash frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C. Protein identity/purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE.

Cross-linking and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry

Cross-linking was accomplished by incubating 20 μM of PccGCS/BpeGReg with 2.5× (50 μM), 5× (100 μM) and 20× (400 μM) of bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate-d0 (BS3-d0) for ∼35 min at room temperature, and the reactions were stopped by adding ammonium bicarbonate to a final concentration of 20 mM. The reactions then were run on Bio-Rad 7.5% Criterion gels to separate oligomers for gel removal (Supplementary Figure S2).

The bands representing different oligomers were excised, and 50% acetonitrile in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate was used to destain the gel pieces. The samples were dehydrated using 100% acetonitrile and by vacuum. Trypsin digestion was completed by the addition of 10 ng/μl trypsin in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate to the dried gel pieces and incubation overnight at 37°C. Peptides were extracted using an extraction buffer consisting of 50% acetonitrile in 5% formic acid, and the extracted peptides were dehydrated with 100% acetonitrile and by vacuum. The final cleanup step involved reconstitution with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, desalting with a C18 microcolumn [28], and drying under vacuum.

The prepared peptides were resuspended in loading buffer (0.1% formic acid, 0.03% trifluoroacetic acid, 1% acetonitrile) and separated on a C18 (1.9 μm, Dr Maisch, Germany) fused silica column (15 cm × 75 μM internal diameter (ID); New Objective, Woburn, MA) by a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RSLCNano and monitored with a Fusion mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Elution of peptides was achieved by a gradient with Buffer E ranging from 3 to 65% with a mobile phase of Buffer D before gradient (Buffer D – 0.1% formic acid in water, Buffer E – 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). Collection at the top speed for 3 s cycles was programmed for the mass spectrometer cycle. Electron-transfer dissociation fragmentation for all precursor ions with charges of 3–8 and higher energy collision dissociation fragmentation for ions with charges of 2–5 were performed by a decision tree. A resolution of 120,000 at m/z 200 in profile mode was used in mass spectrometry scans (400–1600 m/z range, 200,000 AGC, 50 ms maximum ion time), and electron-transfer dissociation (0.7 m/z isolation width, charge dependent collision energy, 10,000 AGC target, 35 ms maximum ion time) and high-energy collision (0.7 m/z isolation width, 32% collision energy, 10,000 AGC target, 35 ms maximum ion time) MS/MS spectra were detected in the ion trap. Dynamic exclusion omitted previously sequenced precursor ions for 20 s within a 10 ppm window, and precursor ions with +1 and +9 or higher charge states were removed from sequencing.

Data analysis was performed using Spectrum Identification Machine (SIM-XL) [29,30]. SIM-XL uses a unique paradigm for search-space reduction and utilizes reporter ions for identifying tandem mass spectra derived from cross-linked peptides. Settings for data analysis were: crosslinker – disuccinimidyl suberate DSS; mass shift – 138.0681; modification mass shift – 156.0786; reaction sites – KK,KS,KN-Term; reporter ions – 222.149, 239.1759, 240.159, 305.2229; precursor ppm – 20; fragment ppm – 20; Xrea threshold – 0; enzyme specificity – fully specific; enzyme – trypsin; enzyme regular expression – [KR](?!P); enzyme C/N terminal – C-terminal; deconvoluted MS/MS – false; fragmentation method – HCD; number of isotopic possibilities – 4; minimum amino acid residues per chain – 4; intra-link max charge – 4; maximum missed cleavages – 3; peaks matched cutoff – 0; minimum MH (linear peptide) – 600; maximum MH (linear peptides) – 6000. Identified cross-links were screened manually for cross-links with inter-link and intra-link scores of 2.0 or greater and fragmentation spectra peaks representing y (C-terminal fragment) and b (N-terminal fragment) ions that include the crosslinked residues as suggested by the developers of SIM-XL [30] (Supplementary Figures S5 and S6).

Enzyme kinetics

Enzyme kinetics assays were performed with the EnzChek pyrophosphate kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), as previously described [15,25]. Proteins were reduced and the ligation/oxidation states were confirmed by UV–Vis spectroscopy before the assays were performed. Enzyme kinetics with FeII-unligated globin and maltose binding protein (MBP) linked-PccDGC were performed in an anaerobic chamber in the presence of ∼75 μM sodium dithionite, while an anaerobically prepared EnzChek kit was used for FeII-unligated PccGCS WT and H237A/K238A reactions. EnzCheck kit instructions were followed and reactions were initiated with 500 μM GTP. Assays were performed in 96-well plates and in triplicate. Three concentrations each of PccGCS WT and H237A/K238A with EcDosP (a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase used at three times the amount of PccGCS to prevent DGC product inhibition) were used to determine turnover numbers in Vmax conditions. In the globin titration experiments, MBP-PccDGC concentration in all reactions was 3 μM, and EcDosP was used at the same concentration. PccGlobin was added at 10× (30 μM) and 20× (60 μM) concentrations, while BpeGlobin was added at 20× (60 μM) to probe for globin-induced effects. Reactions were monitored for 4 h using Epoch plate readers with Gen5 software (Biotek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT), and data analysis was performed using Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR).

Circular dichroism

Spectra for both FeII-O2 PccGCS WT and H237A/K238A were recorded with a JASCO J-1500 CD spectrometer (JASCO, Easton, MD) that was chilled by liquid nitrogen. Proteins were reduced within an anaerobic chamber using sodium dithionite, buffer exchanged into Buffer E (100 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0), and then mixed with oxygenated Buffer E. Concentrations of proteins were ∼50 μM. Spectra shown are averages of three scans of the protein samples at 20°C.

Analytical gel filtration

Size-exclusion chromatography using an Agilent 1200 infinity system with a Sepax SEC-300 (7.8 mm Å × 300 mm, 300 Å), and diode array detector (simultaneous detection at 214, 416 and 431 nm) was used to detect the oligomers of PccGCS WT and H237A/K238A. Sample preparation occurred as follows: proteins reduced in an anaerobic chamber, proteins buffered exchanged into Buffer D (50 mM Tris pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT), and proteins mixed with oxygenated Buffer D. The mobile phase was 150 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0 for all experiments. Calibration curves were determined using ferritin (443 kDa), β-amylase (200 kDa), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66 kDa) and carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa) as globular protein molecular weight standards (MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO).

Electronic absorption spectroscopy

Spectra for PccGCS H237A/K238A were recorded with an Agilent Cary 100 with Peltier accessory (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Sample preparation followed protocols previously described except protein samples were prepared in Buffer D [25,26,31,32].

Stopped-flow ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy

Determination of O2 dissociation rates was completed following previously described procedures [15,25,26]. PccGCS H237A/K238A was reduced in an anaerobic chamber using sodium dithionite, buffered exchanged into Buffer D, removed from the anaerobic chamber, and then mixed with oxygenated Buffer D. Rapid mixing with an equal volume of sodium dithionite solution (50 mM Tris pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM sodium dithionite) occurred within a SX20 stopped-flow apparatus (Applied Photophysics). O2 dissociation was monitored with a diode array detector. Global fitting was completed with Pro-KII software (Applied Photophysics) and additional fitting analysis handled with Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Substrate affinity was determined using a Microcal Auto-iTC200 within the Pennsylvania State University Huck Institute Automated Biological Calorimetry Core facility. PccGCS H237A/K238A was buffer exchanged into 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, and used at a concentration of 80 μM. GTP and two non-hydrolyzable substrate analogues (guanosine-5′-[(α,β)-methyleno]triphosphate, sodium salt (GTP-α-S), and guanosine-5′-(α-thio)-triphosphate, sodium salt (GpCpp); Jena Biosciences) were dissolved in 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, buffer to a stock concentration of 600 μM. The cell was maintained at 25°C, stirred at 750 rpm, and contained 200 μl of protein. Twenty injections of 2 μl of GTP/analog were made over ∼1.5 h.

Results

Cross-linking of PccGCS and BpeGReg

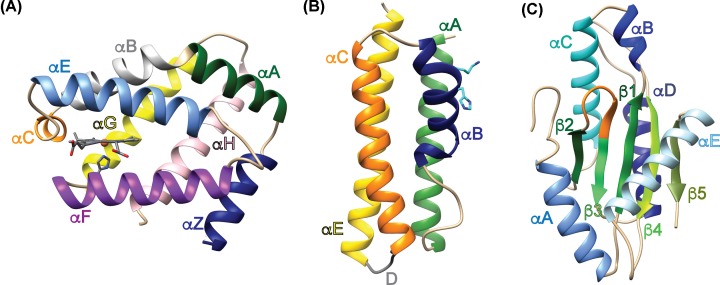

Cross-linking and tandem mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry were utilized in an effort to determine if there are unique interactions between the three GCS domains. PccGCS WT (Uniprot accession number: C6D9C2) consists of four domains, based on sequence alignments and domain homology, with the following approximate boundaries: HisTag (residues 1–11), globin domain (residues 12–181), middle domain (residues 182–331) and DGC domain (residues 332–481) (Figures 1 and 2). Structural features are labeled based on homology models generated using structures of the individual domains of EcDosC (Figure 1). To identify domain interactions, PccGCS WT was cross-linked with an electrophilic crosslinker, different oligomeric states separated using SDS-PAGE, and then each oligomer subjected to tryptic digest/LC-MS/MS analysis to identify cross-linked peptides. PccGCS WT contains 25 lysine residues throughout the 482 amino acid sequence, which are the preferred sites for succinimide cross-linkers. After screening of numerous cross-links by examining the spectra, five crosslinks were found for the tetramer form of PccGCS WT (Figure 3; Supplementary Table S1); three globin domain (helix αF)-middle domain (helix αB) and two globin domain (helix αB)-DGC domain (helix αD) cross-links identified. The dimer form of PccGCS WT did not produce cross-links with spectra that passed screening.

Figure 1. Homology models.

Homology models of the globin, middle, and diguanylate cyclase domains of PccGCS. (A) Globin domain (heme represented by stick-and-ball structure). (B) Middle domain showing the conserved histidine-237 and lysine-238 in cyan. (C) Diguanylate cyclase domain (GGEEF active site residues are shown in orange). Homology models were made for both PccGCS and BpeGReg using EcDosC crystal structures and the Protein Homology/analogY Recognition Engine V2.0 (PHYRE 2) tool [35]. Structure molecular graphics were created using the UCSF Chimera package [39].

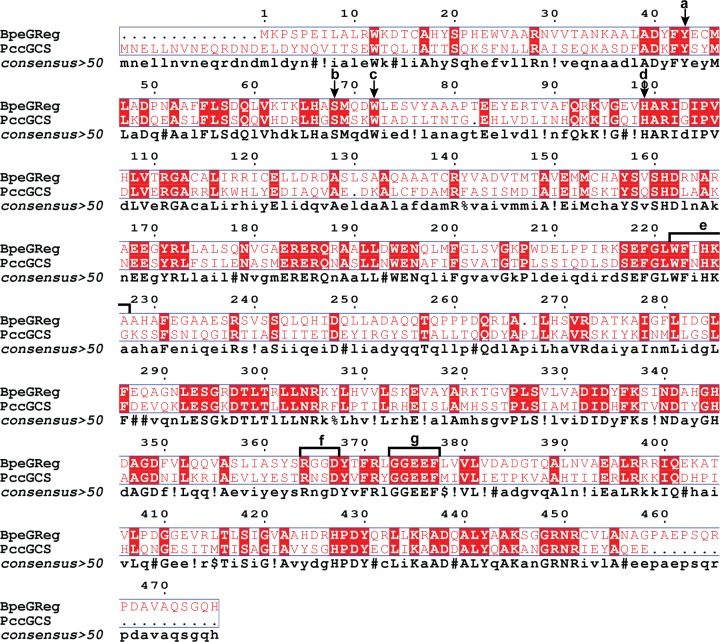

Figure 2. Sequence alignments.

Sequence alignment of BpeGReg and PccGCS. (A) Conserved distal tyrosine (hydrogen bonds with oxygen). (B) Conserved distal serine (helps stabilize bound oxygen). (C) Conserved tryptophan (in contact with edge of heme). (D) Conserved proximal histidine (holds heme in globin domain). (E) Conserved π-helical region. (F) Product-binding inhibitory site (I-site) motif (RxxD). (G) Active site motif (GGEEF). Alignment and image created using MultAlin [40] and ESPript 3.0 [41].

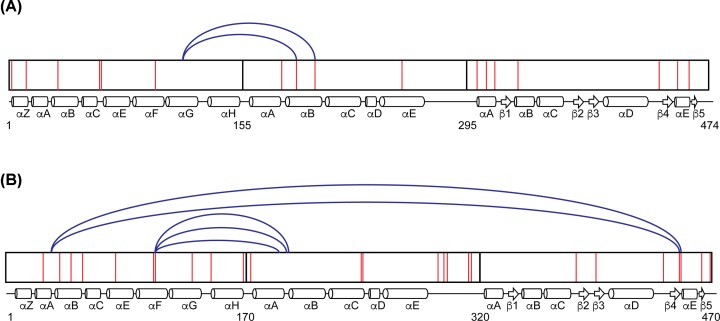

Figure 3. Cross-linking analysis.

Cross-linking maps of BpeGReg and PccGCS tetramer forms. (A) Cross-links for BpeGReg. (B) Cross-links for PccGCS. The three domains of the proteins are shown with the arrangement of their secondary structures (drawn approximately to scale). Lysine residues are shown as red lines within the domains and numbering is based on native residue numbering. Cross-links were identified using Spectrum Identification Machine [29,30].

In analogy to PccGCS, the BpeGReg WT construct (Uniprot accession number: Q7VTL8) consists of four segments (HisTag (residues 1–11), globin domain (residues 12–166), middle domain (residues 167–306), and DGC domain (residues 307–485); Figure 2), and cross-linking for BpeGReg was accomplished in the same manner as described above for PccGCS. BpeGReg contains 17 lysine residues throughout the 485 amino acid sequence (Figure 2). There were only two globin domain (loop between helices αG and αH)-middle domain (helix αB) cross-links identified after inspecting the cross-linking spectra for the tetramer form of BpeGReg (Figure 3). No cross-linking spectra for the dimer form of BpeGReg passed screening, which followed results from PccGCS WT in dimer form. These seven cross-links from PccGCS and BpeGReg provide evidence for globin domain interactions with the middle and output domains.

As the different oligomeric states of PccGCS and BpeGReg were isolated prior to MS analysis, at least one identified cross-link must be between monomers within the tetrameric complexes. However, due to the challenges with generating tetrameric assemblies consisting of four labeling patterns, we were unable to determine which cross-links correspond to inter-monomer cross-links and which are intra-monomer linkages.

Effect of π-helix disruption on diguanylate cyclase activity

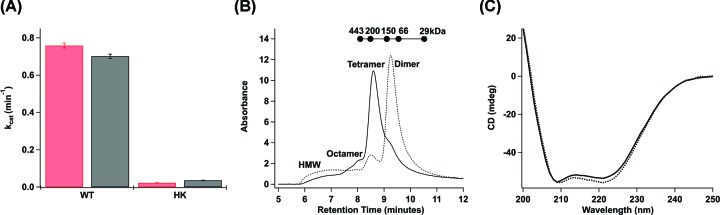

The globin-coupled sensor middle domain contains consecutive conserved histidine and lysine amino acid residues, and these PccGCS residues were mutated to alanines (native residues numbering – H237A and K238A) to disrupt the π-helical nature of helix αB (refer to Figures 1B and 2). Previous work with BpeGReg mutated conserved histidine-225 to alanine (native residues numbering); this mutation led to a construct with undetectable c-di-GMP production from GTP [9]. The production of c-di-GMP from GTP in the presence of phosphodiesterase (to remove product inhibition) was measured for both WT and H237A/K238A variants of PccGCS. The turnover numbers of PccGCS H237A/K238A in aerobic and anaerobic conditions were ∼30× (2.27 × 10−2 min−1) and ∼20× (3.62 × 10−2 min−1), respectively (∼1.5-fold increase in catalysis upon O2 binding), less than the aerobic and anaerobic turnover numbers of PccGCS WT (7.59 × 10−1 min−1 and 7.01 × 10−1 min−1, respectively; ∼2.5-fold increase in catalysis upon O2 binding) (Figure 4A). Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was used to determine if the decreased enzyme activity of PccGCS H237A/K238A was due to changes in the rate of catalysis, substrate affinity, or a combination thereof. Data from titration with GTP was not useable due to the heat generated from diguanylate cyclase catalysis, even with the very slow rate. Binding of the non-hydrolyzable analog GTP-α-S was very weak (Kd > 300 μM) and therefore were not pursued further. In contrast, titration of PccGCS H237A/K238A with GpCpp yielded a Kd of 9.7 ± 3.9 μM (Supplementary Figure S7). For comparison, the PccGCS WT KM for GTP was previously measured to range from 31 to 62 μM, depending on heme ligation state [25]. Therefore, disruption of the π-helix within the middle domain results in a drastic loss of PccGCS diguanylate cyclase activity due to decreased enzymatic catalysis, not substrate binding.

Figure 4. Biochemical effects of π-helix mutations.

Effects of π-helix mutations on PccGCS characteristics. (A) Enzyme kinetics of PccGCS WT (WT) and H237A/K238A (HK). Red values represent proteins in the ligated Fe(II)-O2 state, and black values represent proteins in the unligated Fe(II) state. Turnover numbers were calculated from assays at Vmax conditions with varying enzyme concentrations, and error bars represent standard deviations. (B) Analytical gel filtration analysis of oligomerization states of PccGCS WT (solid line) and H237A/K238A (dotted line). Different oligomeric states are annotated for both constructs on the graph. The molecular weights and retention times of globular protein standards are plotted above the graph. (C) Circular dichroism spectra for PccGCS WT (solid line) and H237A/K238A (dotted line). The plots are the averages of three scans for each construct.

Biophysical characterization of PccGCS π-helix mutant

The structures of the PccGCS WT and H237A/K238A variants were explored to determine if structural changes caused the loss of DGC activity of the mutant. Circular dichroism was employed to investigate the secondary structure compositions of both PccGCS variants, and no significant differences were seen within the spectra of the two variants (Figure 4C). PccGCS oligomerization was observed using analytical gel filtration to ascertain if there were tertiary structural changes that would help explain the changes in DGC activity. The dominant oligomeric state shifted from tetramer (WT) to dimer (H237A/K238A), a significant change in quaternary structure, and possibly tertiary structure, due to the π-helix-disrupting mutations (Figure 4B).

No change in ligand-binding by the globin domain was seen with disruption of the π-helix. The absorption spectra of PccGCS H237A/K238A in various ligation states are identical with those of PccGCS WT (Supplementary Figure S3), and the mutant displayed biphasic O2 dissociation rates very similar to PccGCS WT with slow (k1) and fast (k2) rates of 0.68 ± 0.10 and 3.88 ± 0.32 s−1, respectively [25].

Effect of Isolated globin domains on diguanylate cyclase activity

To directly probe interactions between GCS protein globin and output domains, the diguanylate cyclase domain of PccGCS (native residues numbering 321–470; Figure 2) was expressed as a N-terminal maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion, which resulted in a soluble DGC construct termed MBP-PccDGC. All other non-fusion constructs that were tested resulted in insoluble protein. The globin domains from PccGCS (PccGlobin; native residues numbering 1–176), and BpeGReg (BpeGlobin; native residues numbering 1–161) [26] were used to further probe interactions between the globin and cyclase domains, and to determine if direct linkage through the middle domain is required for the globin domain to affect catalytic activity of the cyclase domain (Supplementary Figure S1).

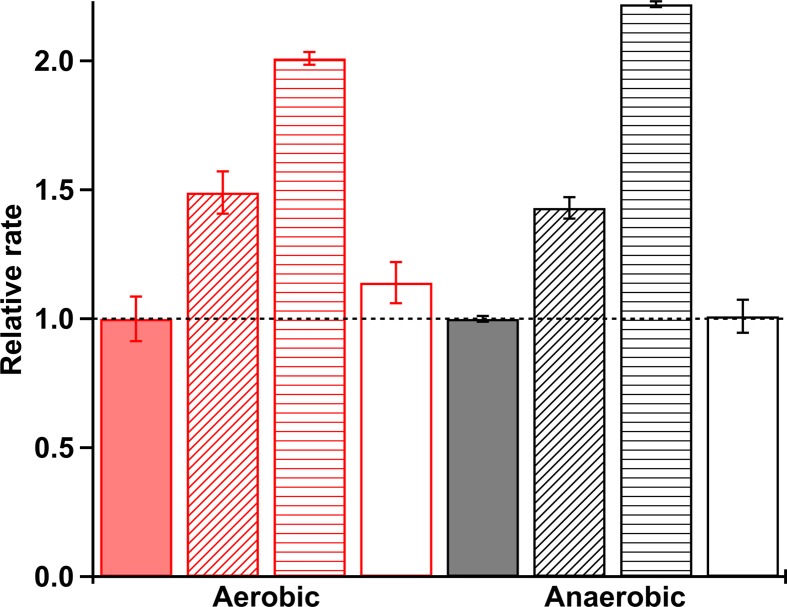

The catalytic rates of c-di-GMP production from MBP-PccDGC alone and in the presence of PccGlobin or BpeGlobin were ascertained in the presence and absence of oxygen (Figure 5 and Supplementary S8). The aerobic rates of MBP-PccDGC supplied with 10× and 20× molar amounts of PccGlobin were ∼1.5- and ∼2.0-fold, respectively, greater than the rate of c-di-GMP production for MBP-PccDGC alone (Figure 5). Similar results were seen for the anaerobic condition (Figure 5). However, the cyclase activity of MBP-PccDGC was not affected by the addition of 20× molar amount of BpeGlobin. These data demonstrate that the cognate globin domain is able to influence DGC activity through specific interactions, even in the absence of a direct linkage between the domains.

Figure 5. Diguanylate cyclase activity.

Isolated diguanylate cyclase activity in the presence of isolated globin domains. All rates are reported relative to PccDGC alone. Red bars, aerobic kinetics (Fe(II)-O2 globin); black bars, anaerobic kinetics (Fe(II) globin). Solid bars, PccDGC alone; diagonal stripes, PccDGC + 10× PccGlobin; horizontal stripes, PccDGC + 20× PccGlobin; empty bars, PccDGC + 20× BpeGlobin.

Discussion

Given the ubiquity of c-di-GMP-related proteins in bacteria, understanding how regulatory domains modulate diguanylate cyclase activity will both improve our understanding of signal transduction within ligand-sensing DGC proteins and potentially identify new ways to target DGCs to inhibit biofilm formation [3,4,6–8]. Structures have been solved for a handful of full-length regulatory domain-DGC proteins and show two general domain organizations: (1) regulatory domain separated from DGC domain by an extended linker (such as WspR and PadC) and (2) regulatory domain and DGC domain in direct contact due to a very short/absent linking domain (including PleD and DgcZ) [16,33,34]. In the first case, ligand binding or phosphorylation of the regulatory domain leads to rearrangements that are propagated through the helical linking domain, leading to rotation of the DGC domains relative to each other and (in)activation. In contrast, activation of the regulatory domain in the second case results in rotation of the DGC domains to align the active site and allow for c-di-GMP production. However, to date, structural information is lacking for DGC proteins that contain substantial linking domains that do not form rod-like structures, such as GCS proteins.

Signal transduction following ligand binding to GCS proteins has been postulated to occur through conformational shifts in the globin domain that are propagated through the middle domain to reach the output domain [23,24]. The cross-linking and globin titration experiments described in this work demonstrate that GCS proteins adopt conformations that allow the globin domain to make interactions with both the middle and output domains of two DGC-containing GCS proteins, PccGCS and BpeGReg (Figures 3 and 5). For BpeGReg and PccGCS, both tetrameric forms exhibited multiple globin/middle cross-links. Two globin/DGC cross-links were observed in the tetramer form tested for PccGCS. To visualize the locations of residues with respect to one another, homology models of the three domains for PccGCS were created using the Protein Homology/analogY Recognition Engine V2.0 (PHYRE 2) tool (Figure 1) [35]. Taken together, these cross-links definitively demonstrate that GCS proteins can adopt conformations that allow both the globin and the middle domains to interact with the DGC output domain.

When comparing cross-linking of both proteins, the following region stood out: the αB helix/π-helical region of the middle domain (Figure 3). The existence of a π-helix within the middle domain of GCS proteins and the cross-links between the π-helix region and globin domain suggest a potential role in transmitting the O2-binding signal. π-Helices are defined by the occurrence of multiple hydrogen bonds between the amide backbone that reside in amino acids i+5 and i within an α-helix and require a bulge or insertion within a typical α-helix sequence. Mutation of residues within the bulge can alter the π-helix structure and function, but without significantly disrupting the α-helix [36]. A unique aspect of π-helices is the ability to move in peristaltic-like shifts that lead to structural changes within proteins [36]. Toluene 4-monooxygenase (T4moH), which consists of three polypeptides (TmoA, TmoE, and TmoB), is an enzyme that hydroxylates toluene with its cognate effector protein T4moD. In the toluene 4-monooxygenase/effector protein complex, active site changes occur due to a π-helical shift caused by T4moD binding to TmoH, which prepares the active site for substrate binding [37]. A π-helix also plays a role in infection caused by Shigella passing through the human small intestine. In response to high concentrations of the bile salt deoxycholate (DOC), which binds to invasion plasmid antigen D (IpaD) of the type three secretion system of Shigella, a π-helical shift within IpaD leads to association with invasion plasmid antigen B (IpaB) and eventually invasion of host cells [38]. Based on a sequence homology of middle domains from EcDosC and 78 DGC-containing GCS homologues, the π-helical kink of EcDosC (H223, K224) is highly conserved [24] and both these residues and the π-helical region are predicted in BpeGReg (native residues numbering H225, K226) and PccGCS (native residues numbering H237, K238) (Figure 2).

For BpeGReg, cross-links were observed between the globin αG/αH loop and the π-helical kink within helix αB of the middle domain. As the αG/αH loop in the globin was observed to become rigid after gas ligand binding to the heme within the histidine kinase-containing GCS from Anaeromyxobacter sp. Fw109-5 [23], this same increase in rigidity of the αG/αH helices loop may occur in BpeGReg, which could result in signal transduction through a π-helical shift in the middle domain and increased DGC activity. Cross-links also show that PccGCS globin αF helix (contains proximal histidine that shifts due to gaseous ligand binding) interacts with the π-helical αB helix of the middle domain, suggesting that the middle domain π-helix is involved in signal transduction pathways in both BpeGReg and PccGCS. The similar secondary structures (Figure 4) and ligand-binding abilities (Supplementary Figure S3) of the PccGCS WT and π-helix mutant (H237A/K238A construct) but major differences in DGC activities and oligomerization (Figure 4) suggest significant changes in quaternary structure and loss of π-helix interactions leading to interrupted signal transduction. In two previous studies by Wan and colleagues, mutation of the conserved histidine and lysine residues within EcDosC and BpeGReg led to inactive phenotypes for the two enzymes [9,10], supporting our data highlighting this region as being critical for enzyme activity of GCS proteins.

Interactions within PccGCS suggest protein structures wherein the domains are folded into a more compact structure than previously hypothesized for DGC-containing GCS proteins [24]. Cross-links were observed between the globin and cyclase domains within PccGCS, suggesting a mechanism of direct transduction of the ligand binding signal (Figure 3). The globin helix αB was linked to the helix αD of the DGC domain. Helix αB of the globin domain contains the distal tyrosine within the heme pocket that interacts directly with gaseous ligands. When a ligand binds to the globin heme, the signal could be transmitted to the DGC active site through the close association of the DGC helix αD with the active site αB-αC loop, which is involved in GTP binding (Figures 1–3).

To further probe the role of direct globin-DGC interactions, isolated PccGlobin, BpeGlobin, and PccDGC domains were investigated. The addition of cognate globin domain, PccGlobin, increased the activity of MBP-PccDGC in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, whereas non-cognate BpeGlobin addition had no effect on MBP-PccDGC, even at 20-fold excess (Figure 5). These results demonstrate that PccGlobin makes specific interactions with PccDGC that increase the rate of GTP to c-di-GMP conversion. However, without the middle domain linkage, PccGlobin was no longer able to exert O2-dependent effects on diguanylate cyclase activity, suggesting that the middle domain is required to correctly position the globin domain relative to the DGC domain, as previous studies demonstrated higher catalytic activity for O2-bound full-length PccGCS (∼2.5-fold increase in cyclase activity for PccGCS WT Fe(II)-O2 vs. Fe(II)) [25].

A pairwise sequence alignment of the amino acid sequences of PccGCS and BpeGReg was used to identify sequence characteristics that could result in differences in crosslinking patterns and globin-dependent MBP-PccDGC activity. The alignment indicates that the overall sequences are approximately 35% identical and 52% similar (Figure 2); PccGCS has a globin domain that is 12 amino acids longer (as an N-terminal extension) than the globin domain of BpeGReg, while BpeGReg has a larger DGC domain when compared to PccGCS (17 residue extension at the C-terminus). One possibility is a role for the 12-residue N-terminal extension of the PccGCS globin domain; however, cross-links were not observed between the globin extension and the DGC domain, possibly due to the absence of a lysine within the extension. The data did identify cross-links between the globin domain (helix αB) and the DGC (helix αD) of PccGCS, suggesting that interactions between the globin and DGC helices could be mediating the cognate interactions that allow for globin-specificity in activating MBP-PccDGC.

BpeGReg and PccGCS cross-linking analysis, π-helix mutations, and the globin-DGC activity assays suggest that DGC-containing GCS proteins can form relatively compact structures, with the N-terminal globin domain directly interacting with the C-terminal diguanylate cyclase domain. These GCSs have a globular shape based on analytical gel filtration experiments [25], and the data presented here further support the formation of compact structures. Cross-linking data identified interactions between the DGC output domain and the sensor globin domain within PccGCS, suggesting that globin domain helices that undergo conformational changes due to ligand binding can directly transduce signal through interactions near the DGC active site. The middle domain αB helix/π-helical region has emerged as a central component of DGC-containing GCS proteins and appears to be crucial in maintaining the correct quaternary structure for function, even in the presence of direct globin-DGC domain interactions, as evidenced by the lack of O2-dependent changes in activity in the studies on isolated domains. Cross-linking interactions between the DGC output domain and the sensor globin domain within PccGCS, and the activity of the DGC domain of PccGCS being influenced by the cognate PccGCS globin domain, but not the BpeGReg globin domain, are likely due to sequence differences. Based on the results of the present study, the proper quaternary structures of DGC GCSs that effectively convert GTP into c-di-GMP appear dependent on the middle domain/π-helical region for correct positioning of subunits within oligomers. Future structural studies will add to our understanding of how GCS structure leads to function and the mechanism of signal transduction within GCS proteins, and may allow for targeting GCS activity as a method to modulate bacterial biofilm formation and virulence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Weinert lab for assistance and helpful suggestions, and Julia Fecko and Dr Neela Yennawar of the Pennsylvania State University Huck Institute Automated Biological Calorimetry Facility for assistance with ITC measurements. The present study was supported in part by the Emory Integrated Proteomics Core (EIPC), which is subsidized by the Emory University School of Medicine and is one of the Emory Integrated Core Facilities. Additional support was provided by the Georgia Clinical & Translational Science Alliance of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002378. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- AfGcHK

GCS from Anaeromyxobacter sp. FW109-5

- BpeGReg

GCS from Bordetella persussis

- c-di-GMP

cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate

- DGC

diguanylate cyclase

- EcDosC

GCS from Escherichia coli

- GCS

globin coupled sensor

- GpCpp

guanosine-5′-[(α,β)-methyleno]triphosphate, sodium salt

- GTP-α-S

guanosine-5′-(α-thio)-triphosphate, sodium salt

- HDX-MS

hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry

- HemAT-Bs

GCS from Bacillus subtilis

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- MBP

maltose-binding protein

- MCP

methyl accepting chemotaxis protein

- PccGCS

GCS from Pectobacterium carotovorum

- WT

wild-type

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by NSF [grant number CHE1352040 (to E.E.W.)]; and Frasch Foundation [grant number 824-H17 (to E.E.W.)]; National Institutes of Health General Medical Sciences Institutional Research and Career Development Award [grant number K12 GM000680 (to J.A.W.)].

Author Contribution

J.A.W. and E.E.W. designed the research. J.A.W., Y.W., J.R.P., and E.E.W. performed the research. J.A.W. and E.E.W. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ross P., Weinhouse H., Aloni Y., Michaeli D., Weinberger-Ohana P., Mayer R. et al. (1987) Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 325, 279–281Epub 1987/01/15 10.1038/325279a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hengge R., Grundling A., Jenal U., Ryan R. and Yildiz F. (2016) Bacterial Signal Transduction by Cyclic Di-GMP and Other Nucleotide Second Messengers. J. Bacteriol. 198, 15–26, Pubmed Central PMCID: 4686208 10.1128/JB.00331-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall C.L. and Lee V.T. (2018) Cyclic-di-GMP regulation of virulence in bacterial pathogens. Wires RNA 9, 10.1002/wrna.1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jakobsen T.H., Tolker-Nielsen T. and Givskov M. (2017) Bacterial Biofilm Control by Perturbation of Bacterial Signaling Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1970 10.3390/ijms18091970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlstrom K.M. and O’Toole G.A. (2017) A Symphony of Cyclases: Specificity in Diguanylate Cyclase Signaling. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 71, 179–195 10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenal U., Reinders A. and Lori C. (2017) Cyclic di-GMP: second messenger extraordinaire. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 271–284 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krasteva P.V. and Sondermann H. (2017) Versatile modes of cellular regulation via cyclic dinucleotides. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 350–359 10.1038/nchembio.2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orr M.W., Galperin M.Y. and Lee V.T. (2016) Sustained sensing as an emerging principle in second messenger signaling systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 34, 119–126 10.1016/j.mib.2016.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan X., Tuckerman J.R., Saito J.A., Freitas T.A., Newhouse J.S., Denery J.R. et al. (2009) Globins synthesize the second messenger bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic diguanosine monophosphate in bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 388, 262–270, Epub 2009/03/17 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan X.H., Saito J.A., Newhouse J.S., Hou S.B. and Alam M. (2017) The importance of conserved amino acids in heme-based globin-coupled diguanylate cyclases. PLoS One 12, e0182782 10.1371/journal.pone.0182782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns J.L., Jariwala P.B., Rivera S., Fontaine B.M., Briggs L. and Weinert E.E. (2017) Oxygen -Dependent Globin Coupled Sensor Signaling Modulates Motility and Virulence of the Plant Pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 2070–2077 10.1021/acschembio.7b00380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu T., Huang D., Yan F., Stranava M., Bartosova M., Fojtikova V. et al. (2015) Gaseous O2, NO, and CO in signal transduction: structure and function relationships of heme-based gas sensors and heme-redox sensors. Chem. Rev. 115, 6491–6533 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker J.A., Rivera S. and Weinert E.E. (2017) Mechanism and Role of Globin-Coupled Sensor Signalling. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 71, 133–169 10.1016/bs.ampbs.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou S., Larsen R.W., Boudko D., Riley C.W., Karatan E., Zimmer M. et al. (2000) Myoglobin-like aerotaxis transducers in Archaea and Bacteria. Nature 403, 540–544, Epub 2000/02/17 10.1038/35000570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns J.L., Rivera S., Deer D.D., Joynt S.C., Dvorak D. and Weinert E.E. (2016) Oxygen and c-di-GMP Binding Control Oligomerization State Equilibria of Diguanylate Cyclase-Containing Globin Coupled Sensors. Biochemistry 55, 6642–6651 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schirmer T. (2016) C-di-GMP Synthesis: Structural Aspects of Evolution, Catalysis and Regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 3683–3701 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stranava M., Martinek V., Man P., Fojtikova V., Kavan D., Vanek O. et al. (2016) Structural characterization of the heme-based oxygen sensor, AfGcHK, its interactions with the cognate response regulator, and their combined mechanism of action in a bacterial two-component signaling system. Proteins 84, 1375–1389, Epub 2016/06/09 10.1002/prot.25083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willett J.W. and Crosson S. (2017) Atypical modes of bacterial histidine kinase signaling. Mol. Microbiol. 103, 197–202 10.1111/mmi.13525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sen Santara S., Roy J., Mukherjee S., Bose M., Saha R. and Adak S. (2013) Globin-coupled heme containing oxygen sensor soluble adenylate cyclase in Leishmania prevents cell death during hypoxia. PNAS 110, 16790–16795Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3801027 10.1073/pnas.1304145110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassler J., Schultz J.E. and Lupas A.N. (2018) Adenylate cyclases: Receivers, transducers, and generators of signals. Cell. Signal. 46, 135–144 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivera S., Young P.G., Hoffer E.D., Vansuch G.E., Metzler C.L., Dunham C.M. et al. (2018) Structural Insights into Oxygen-Dependent Signal Transduction within Globin Coupled Sensors. Inorg. Chem. 57, 14386–14395, Epub 2018/11/01 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W. and Phillips G.N. Jr (2003) Structure of the oxygen sensor in Bacillus subtilis: signal transduction of chemotaxis by control of symmetry. Structure 11, 1097–1110, Epub 2003/09/10 10.1016/S0969-2126(03)00169-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stranava M., Man P., Skalova T., Kolenko P., Blaha J., Fojtikova V. et al. (2017) Coordination and redox state-dependent structural changes of the heme-based oxygen sensor AfGcHK associated with intraprotein signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 20921–20935 10.1074/jbc.M117.817023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarnawski M., Barends T.R. and Schlichting I. (2015) Structural analysis of an oxygen-regulated diguanylate cyclase. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 71, 2158–2177 10.1107/S139900471501545X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns J.L., Deer D.D. and Weinert E.E. (2014) Oligomeric state affects oxygen dissociation and diguanylate cyclase activity of globin coupled sensors. Mol. Biosyst. 10, 2823–2826 10.1039/C4MB00366G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivera S., Burns J.L., Vansuch G.E., Chica B. and Weinert E.E. (2016) Globin domain interactions control heme pocket conformation and oligomerization of globin coupled sensors. J. Inorg. Biochem. 164, 70–76 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klock H.E. and Lesley S.A. (2009) The Polymerase Incomplete Primer Extension (PIPE) method applied to high-throughput cloning and site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 498, 91–103, Epub 2008/11/07 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhai L.H., Chang C., Li N., Duong D.M., Chen H., Deng Z.X. et al. (2013) Systematic research on the pretreatment of peptides for quantitative proteomics using a C-18 microcolumn. Proteomics 13, 2229–2237 10.1002/pmic.201200591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lima D.B., de Lima T.B., Balbuena T.S., Neves-Ferreira A.G.C., Barbosa V.C., Gozzo F.C. et al. (2015) SIM-XL: A powerful and user-friendly tool for peptide cross-linking analysis. J. Proteomics 129, 51–55 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lima D.B., Melchior J.T., Morris J., Barbosa V.C., Chamot-Rooke J., Fioramonte M. et al. (2018) Characterization of homodimer interfaces with cross-linking mass spectrometry and isotopically labeled proteins. Nat. Protoc. 13, 431–458 10.1038/nprot.2017.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinert E.E., Plate L., Whited C.A., Olea C. Jr and Marletta M.A. (2010) Determinants of ligand affinity and heme reactivity in H-NOX domains. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49, 720–723, Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3517115. Epub 2009/12/18 10.1002/anie.200904799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinert E.E., Phillips-Piro C.M., Tran R., Mathies R.A. and Marletta M.A. (2011) Controlling conformational flexibility of an O(2)-binding H-NOX domain. Biochemistry 50, 6832–6840Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC3153587. Epub 2011/07/05 10.1021/bi200788x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whiteley C.G. and Lee D.J. (2015) Bacterial diguanylate cyclases: Structure, function and mechanism in exopolysaccharide biofilm development. Biotechnol. Adv. 33, 124–141 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gourinchas G., Etzl S., Gobl C., Vide U., Madl T. and Winkler A. (2017) Long-range allosteric signaling in red light-regulated diguanylyl cyclases. Sci Adv 3, e1602498 10.1126/sciadv.1602498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelley L.A., Mezulis S., Yates C.M., Wass M.N. and Sternberg M.J.E. (2015) The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 10.1038/nprot.2015.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooley R.B., Arp D.J. and Karplus P.A. (2010) Evolutionary Origin of a Secondary Structure: pi-Helices as Cryptic but Widespread Insertional Variations of alpha-Helices That Enhance Protein Functionality. J. Mol. Biol. 404, 232–246 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey L.J., Mccoy J.G., Phillips G.N. and Fox B.G. (2008) Structural consequences of effector protein complex formation in a diiron hydroxylase. PNAS 105, 19194–19198 10.1073/pnas.0807948105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernard A.R., Jessop T.C., Kumar P. and Dickenson N.E. (2017) Deoxycholate-Enhanced Shigella Virulence Is Regulated by a Rare pi-Helix in the Type Three Secretion System Tip Protein IpaD. Biochemistry 56, 6503–6514 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C. et al. (2004) UCSF chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corpet F. (1988) Multiple Sequence Alignment with Hierarchical-Clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 10881–10890 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robert X. and Gouet P. (2014) Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 10.1093/nar/gku316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.