Abstract

Background

Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer) powder is in rising demand because powder forms of foods are convenient to handle and are highly preservable. However, ginseng powder (GP) manufactured using the conventional process of air drying and dry milling suffers nutrient destruction and a lack of microbiological safety. The objective of this study was to prepare GP using a novel process comprised of UV-TiO2 photocatalysis (UVTP) as a prewashing step, wet grinding, high hydrostatic pressure (HHP), and freeze-drying treatments.

Methods

The effects of UVTP and HHP treatments on the microbial population, ginsenoside concentration, and physiological characteristics of GP were evaluated.

Results

When UVTP for 10 min and HHP at 600 MPa for 5 min were combined, initial 4.95 log CFU/g-fw counts of total aerobes in fresh ginseng were reduced to lower than the detection limit. The levels of 7 major ginsenosides in UVTP-HHP–treated GP were significantly higher than in untreated control samples. Stronger inhibitory effects against inflammatory mediator production and antioxidant activity were observed in UVTP-HHP–treated GP than in untreated samples. There were also no significant differences in CIELAB color values of UVTP-HHP–treated GP compared with untreated control samples.

Conclusion

Combined processing of UVTP and HHP increased ginsenoside levels and enhanced the microbiological safety and physiological activity of GP.

Keywords: Ginseng powder, Ginsenoside, High hydrostatic pressure, Microbiological safety, Physiological activity

1. Introduction

Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer) has been used as a functional food and as a traditional medicine in Asia for more than 2,000 years [1]. Ginseng roots are known to contain significant levels of highly bioactive compounds, including the phenolic acids maltol, salicylic acid, vanillic acid, and p-coumaric acid [2]. Ginseng roots contain unique types of saponin called ginsenosides that exhibit health-beneficial effects, such as antioxidant, antihypertensive, antitumor, insulin resistance reduction, chemoprotective, immunomodulating, antidiabetic, and phytoestrogenic effects [3].

One of the general forms of dehydrated ginseng root is white ginseng powder (GP). White GP is an air-dried type of ginseng powder prepared conventionally by exposing ginseng roots to sunlight or mild heat treatment of approximately 60°C, followed by a dry milling process. However, this conventional procedure is not microbiologically controlled because the drying conditions are subjected to microbial growth and the milling process suffers a high possibility of cross-contamination [4]. Although powder forms of food products exhibit a high degree of preservability and an increased shelf life because of an extremely low water content. Moreover, powdery foods are convenient for handling and transport [5]. However, outbreaks of biological deterioration have been reported even for powdered foods due to cross-contamination during the manufacturing and processing [6]. In addition, even if powdered foods have a low water activity, some microorganisms, such as xerophilic yeasts and molds, can grow under dry conditions [7].

UV-TiO2 photocatalysis (UVTP) is a powerful surface decontamination technique that can inactivate pathogens by the generation of reactive oxygen species, such as hydroxyl radicals. The pasteurization mechanism of this technology is attracting attention because it is based on reactive oxygen species generation and also on denaturation of DNA by ultraviolet light. The main advantages of UVTP include effective disinfection of pathogenic bacteria while not affecting the organoleptic properties of food materials, such as color and texture [8], [9]. However, UVTP is a nascent technology, and its applications for inactivation of microorganisms in ginseng have not yet been reported.

High hydrostatic pressure (HHP) is a nonthermal food-processing technique that has gained a recent commercial success. HHP is a postpackaging technique for aseptic preservation of foods, even after processing [10]. For example, the antioxidant activity and phenolic content of banana puree and cape gooseberry pulp increased after application of HHP as the cell wall collapsed and mass transfer increased [11], [12]. HHP can also induce inactivation of enzymes under certain pressure ranges due to denaturation of the tertiary structure of proteins [13].

Recent studies have reported the use of HHP technology for production of powdered food products. For example, Park et al [14] reported the use of HHP technology in combined process for production of garlic powder with improved microbiological safety and less pungent flavor. Lee et al [15] also reported the application of HHP treatment rather than a thermal treatment for manufacturing of red bean powder with improved microbiological safety, physicochemical, and functional properties. There are several studies regarding extraction of ginsenosides using HHP, but the application of HHP in GP production for purposes of microbiological safety has not yet been reported.

The objective of this study was to develop a novel powder-manufacturing process using a combined process of UVTP as a washing step, wet grinding, HHP, and freeze-drying treatments. The microbiological safety, ginsenosides extraction, and physicochemical properties of prepared GP were assessed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Fresh Korean 5-year-old ginseng roots cultivated in Geumsan were purchased from the Gyeongdong Market, Seoul, Korea. The fresh weight of ginseng roots was 60–70 g. The roots were soaked in tap water for 30 min and washed using a brush to eliminate soil residue. The washed roots were stored at 4°C until the start of the experiment within 2 days.

2.2. Preparation of GP using the novel process

The combined process used in this study consisted of four steps, including UVTP, wet grinding, HHP, and freeze-drying (Fig. S1).

2.2.1. UVTP as a prewashing step

Fresh ginseng roots were cut into 2-cm-thick pieces. Photocatalysis treatment was conducted in a photocatalytic reactor newly developed in our laboratory (Fig. S1). This reactor consisted of a stainless steel vessel (50 L), an air pump, and eight UV-C lamps (254 nm, 35 W, 25 mW/cm2; Sankyo Denki, Japan) equipped with TiO2-coated quartz tubes (Taekyeong UV Co., Korea). The air pump was fitted at the bottom of the reactor to produce agitation in the wash water during the disinfection treatment. UV-C lamps fitted with quartz tubes were placed in the vessel, with four on the top and four on the bottom. These assemblies were submerged in water inside the reactor. Noncoated quartz tubes were also used for UV-C–alone treatment (without TiO2-coated quartz tubes), and a simple water washing treatment with UV lamps on and UV lamps off (dark) within the reactor was used as a control. Fresh ginseng was immersed in the reactor vessel containing 45 L of tap water, and UVTP, UV, and water washing treatments were carried out each for 10 min.

2.2.2. Wet grinding

Distilled water was added to the sliced ginseng roots, and wet grinding was carried out using a blender for 2 min with 30-s grinding pulses and a 10-s break. Finally, 100 mL of ginseng paste was packaged into a flexible polyethylene terephthalate pouch (13 cm × 18 cm) and heat-sealed with negligible headspace.

2.2.3. HHP pasteurization step

Ginseng paste samples were treated with HHP using a pilot scale of HHP at 600 MPa/5 L (BaoTou Kefa Co., Ltd., China). The pressure was increased at a rate of 2 MPa/s, and the decompression time was approximately 10 s. Tap water was used as a pressure transmission fluid. Each packaged ginseng paste sample was loaded into the pressure vessel and pressurized at 300, 400, 500, and 600 MPa for 5 min at 25°C.

2.2.4. Freeze-drying

After pressurization, ginseng paste samples were opened and spread over a Petri dish as a thin layer and then frozen rapidly at −80°C in a deep freezer for 2 h. The frozen paste was dried using a freeze-dryer (Alpha 2-4 LD plus; Martin Christ Gefriertrocknungsanlagen GmbH, Germany). The main drying was conducted at 0.37 mbar for 20 h while the coil temperature was −30°C. Final drying was conducted at 0.010 mbar for 2 h while the coil temperature was −76°C to remove bound moisture by desorption. Dried GP was collected and immediately used for analysis to avoid moisture absorption.

2.3. Determination of ginsenosides

2.3.1. Extraction of crude saponins

Freeze-dried GP (5 g) was sonicated in 70% methanol for 2 h at room temperature. A round-bottom flask fitted with a cooling condenser was used to evaporate the methanol solution [16]. The extract obtained was evaporated using a rotary evaporator under vacuum at 60°C. The evaporated residue was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water.

2.3.2. HPLC analysis of ginsenosides

Levels of seven major ginsenosides were analyzed using the HPLC method [17], [18], [19]. The HPLC system consisted of a Dionex Summit HPLC (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) with a UV detector (UVD340U), a P680 pump, an autosampler, and a column oven (TCC100). A Capcell Pak column (C18 MG, 4.6 × 250 mm; Shiseido Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used. The detection wavelength was set at 203 nm, and the solvent flow rate was held constant at 1.0 mL/min. The column temperature was fixed at 25°C using a column oven. The mobile phase used for separation consisted of Solvent A (10% acetonitrile) and Solvent B (90% acetonitrile). The injection volume was 20 μL for analysis. Peak identifications were based on retention times and comparisons with injected standard samples. All values were calculated on a dry weight basis.

2.4. Microbial analysis

Effects of the complete combined process on the viability of naturally occurring microorganisms were examined following the method (AOAC, 1995). GP samples (3 g) after freeze-drying were placed in sterile filter bags (Interscience, France), and 1% buffered peptone water was added 7 times the amount of GP samples, followed by homogenization with a stomacher MIX 2 (AES Laboratories, France) for 2 min. Then, the liquid portion, which passed through the filter, was used for analysis. The plate count method was used to enumerate microbial viability in the GP. One milliliter of the filtered sample was serially diluted with 0.85% saline water and counted using pour plating onto triplicate plates of nutrient agar (Difco, USA) and potato dextrose agar (Difco, USA). Microbial enumeration was conducted after incubation of agar plates at 37°C for 48 h.

2.5. Color measurement

Color changes of each powder sample were measured using a CR-400 chromameter (Konica Minolta Sensing Inc., Japan) with the CIELAB (L*, a*, b*) system. The chromameter was calibrated using a calibration tile (Y = 92.3, x = 0.3156, y = 0.3433) to set standards for L*, a*, and b* values before use. CIELAB values can be expressed as L* to indicate lightness (+) to darkness (−), a* to indicate redness (+) to greenness (−), and b* to indicate yellowness (+) to blueness (−). The total color difference (ΔE) against a control sample was calculated using the following equation, which represents the magnitude of color value changes (L*, a*, b*) against a negative control sample (L0, a0, b0):

2.6. Antioxidant activity

2.6.1. Determination of pH

GP samples of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 g were added to 10 mL of distilled water and mixed for 1 min using a Genie 2 vortex (Scientific Industries, Inc., USA). After mixing, solutions were stabilized at room temperature for 1 h to reach equilibrium. The pH of GPs was measured using a glass electrode pH meter (520A; Thermo Scientific, USA).

2.6.2. Total phenolic contents

Analysis of total phenolic contents followed the spectrophotometric method using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent [20] following modification of a previous procedure [21]. Extraction of GP was also conducted following modification of a previously described method. Each powder sample was added to 10 mL of 80% methyl alcohol, and extraction was conducted with sonication for 2 h at 40°C. Resultant solutions were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 20 min, and then the last supernatant was used for study.

An aliquot of 0.1 mL of each extract was added to 1.5 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and diluted with a 10 times amount of distilled water, followed by equilibration for 5 min at room temperature. Then, 1.5 mL of a 6% sodium carbonate solution was added to each sample, followed by incubation for 90 min at room temperature. Finally, the absorbance value was measured spectrophotometrically at 765 nm. Total phenolic contents of GP were quantified using a gallic acid (Samchun Pure Chemicals, Co., Ltd., Korea) standard curve and expressed as micrograms of gallic acid equivalents per g-dry weight (μg GAE/g-dw).

2.6.3. DPPH radical–scavenging activity

Extraction of GP was conducted following modification of a previous method [19]. One gram of each powder sample was added to 10 mL of 80% methyl alcohol (HPLC grade; Honeywell, USA), and extraction was conducted with sonication for 2 h at 40°C. Resultant solutions were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 20 min, and supernatants were collected for analysis.

Analysis of the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical–scavenging activity was conducted following modification of a previous method [19]. First, 0.1 mM DPPH (Sigma-Aldrich Co., USA) in 80% methyl alcohol was prepared, and 0.25 mL of an extracted GP solution that was processed with each condition was added to 1.25 mL of a 0.1 mM DPPH solution. Then, 0.25 mL of 80% methyl alcohol was added instead of the extracted solution as a control. After incubation in the dark at room temperature for 30 min, the absorbance value at 517 nm was measured spectrophotometrically using a UV–Vis UV-mini 1240 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). The DPPH free radical–scavenging activity was calculated as a percentage of inhibition (% inhibition) using the following equation:

where A517 control indicates the absorbance of a control and A517 sample indicates the absorbance of a sample.

2.7. Antiinflammation activity

2.7.1. Cell culture

The mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 μg/mL penicillin, 25 μg/mL amphotericin B, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

2.7.2. Cell viability assay and nitric oxide (NO) measurement

RAW 264.7 cell proliferation was evaluated using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo, Japan). Cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates overnight and subsequently treated with GP solution (250, 500, and 1,000 ng/mL) for 24 h. At the end of the treatment period, 10 μL of the cell viability assay solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 30 min. The absorbance value was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Results were expressed as a percentage of a control.

Accumulated nitrite (NO2−) in the culture medium was measured following a modified version of the assay described by Kang et al [1]. RAW 264.7 cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well on a 96-well plate and incubated overnight. Subsequently, cells were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 ng/mL) and treated with GP solution (250, 500, and 1,000 ng/mL). Then, 100 μL of the cultured supernatant was plated in a 96-well plate, and 100 μL of Griess reagent was added. The plate was incubated for 10 min, and the absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Results from triplicate experiments were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Version 21, IBM Corporation, USA). Results were expressed as mean values along with standard deviations (means ± SDs). Statistical analysis was performed using Duncan's multiple range test, and significance was defined at p < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Inactivation of naturally occurring microorganisms

Inactivation of naturally occurring microorganisms using the combined process with/without a pretreatment of UVTP is shown in Fig. 1A. Bacterial populations were decreased to 2.22 log CFU/g-dw when GP was subjected to HHP at 600 MPa for 5 min. When GP was exposed to a combined treatment of 10 min of UVTP followed by HHP at 500 MPa, total aerobic populations were significantly decreased to 1.72 log CFU/g-dw. Furthermore, aerobic microorganisms were not detected after treatment at 600 MPa. When GP was exposed to a combined treatment of UVTP for 10 min followed by HHP above 400 MPa, the yeast and mold population was completely eliminated (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, commercial white GP, used as a positive control, exhibited 4.75 and 2.49 log CFU/g-dw value for total aerobes and total yeast and mold counts, respectively (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Inactivation of total aerobes and yeasts and molds in ginseng powder using the combined process of UV-TiO2 photocatalysis (UVTP) and high hydrostatic pressure (HHP). Error bars represent standard deviations from the mean (n = 3).

In general, microbial cells with a high resistance to heat are also resistant to pressurization [22]. In this study, approximately 2 log CFU/g-dw of naturally occurring microorganisms remained after pressurization at 600 MPa for 5 min. However, a combined treatment of UVTP with HHP achieved a greater reduction of microbial levels. UVTP disinfection technology is based on surface hydroxylation by hydroxyl radicals, and a synergistic effect of UVTP and HHP mechanisms was achieved leading to much higher bactericidal effects [23]. Researchers have reported the use of other intervention technologies for disinfection of GP. For example, Byun et al [24] used gamma irradiation and ozone treatment for sterilization of red GP but achieved only a 1-log microbial reduction with 2.5-kGy gamma irradiation and ozone treatment at 18 ppm for 4 h. Kwon et al [25] also investigated the effect of gamma irradiation on GP and achieved almost a 5-log reduction of naturally occurring microorganisms under a high dose of 10 kGy. In our study, the combined process of UVTP and HHP at 600 MPa for 5 min achieved complete disinfection. Thus, it could be an effective strategy for preparation of other powdered food products.

3.2. Determination of ginsenosides in GP

Levels of the seven major ginsenosides (Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re, Rg1, and Rg2) in GP are shown in Fig. 2. Ginsenoside levels under all UVTP-HHP treatment for GP were higher than for untreated controls. Zhang et al [26] also reported higher levels for all seven ginsenosides in GP after HHP. The level of Rb1 for untreated GP was 2.82 mg, and for UVTP-HHP–treated GP, it was 6.21, approximately 3 times higher. Levels of Rc, Rd, Re, Rg1, and Rg2, which are the main components of the plant, were also higher than for untreated controls. UVTP-HHP processing of GP contributed to enhanced extraction efficiencies of ginsenoside functional materials through cell structural modification. Approximately 40 ginsenoside compounds have been identified in ginseng roots, and researchers are now focused on the specific mechanism for functional properties of each ginsenoside instead of whole ginseng root extracts [27], [28], [29]. Conventional extraction techniques such as heat, refluxing, and Soxhlet usually require long extraction times and suffer low-efficiency values. Moreover, many materials are thermally unstable and may degrade during a thermal extraction. The proposed process of producing GP has advantages of enhanced efficiency for specific ginsenoside extraction and less transformation of each ginsenoside.

Fig. 2.

Effect of the combined process of UV-TiO2 photocatalysis (UVTP) and high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) on the ginsenoside contents of ginseng powder. Error bars represent standard deviations from the mean (n = 3).

3.3. Effect of the combined process on CIELAB values of GP

The effect of the combined process on CIELAB (L*, a*, b*) values of GP was examined (Table 1). L*, a*, b*, and total color difference values did not differ significantly in treated GP, compared with control samples for all applied treatments. UVTP and HHP did not affect CIELAB values of GP or total color difference during the combined process of GP production. HHP has been reported not to alter the color of fresh produce [11]. Ghafoor et al [30] applied HHP for preparation of red ginseng and measured high a* values (redness) due to the Maillard reaction.

Table 1.

Effect of the combined treatment of UV-TiO2 photocatalysis (UVTP) and high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) on CIELAB values of ginseng powder

| Treatment | L* | a* | b* | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 78.84 ± 0.86a | −0.56 ± 0.02a | 15.89 ± 0.25a | – |

| UVTP, 10 min | 79.41 ± 0.16a | −0.59 ± 0.03a | 15.90 ± 0.11a | 0.75 ± 0.84a |

| HHP 600 MPa, 5 min | 79.42 ± 1.22a | −0.55 ± 0.01a | 15.58 ± 0.29a | 0.72 ± 0.56a |

| UVTP-HHP | 79.43 ± 0.69a | −0.58 ± 0.03a | 15.91 ± 0.09a | 0.80 ± 0.43a |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different small letters in the same column for each value indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). This ‘a’ represents the statistical difference between treatments. All ‘a’ means values are not different statistically.

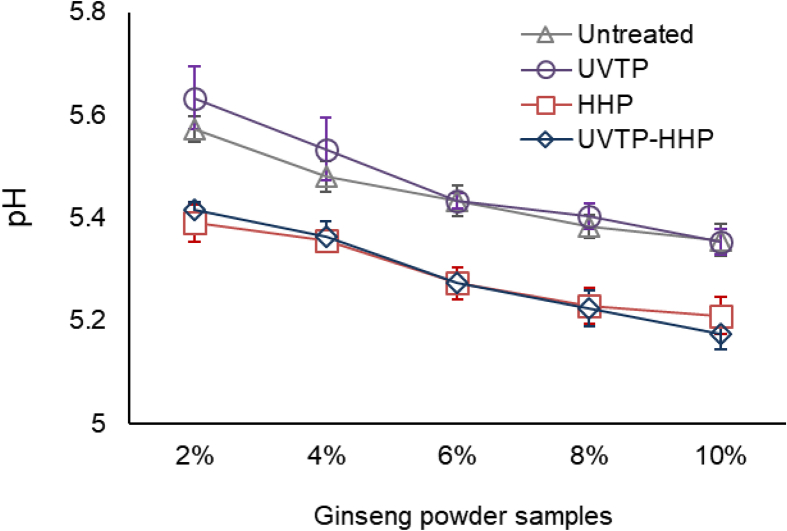

3.4. Effect of the combined process on the pH value of GP

The effect of the combined process on the pH value of GP was studied (Fig. 3). For all treatments, pH values of GP were decreased as the concentration increased, perhaps due to the dissolution of acidic compounds. Also, among all treatments at the same concentration, UVTP did not affect the pH values of aqueous solutions, whereas pressurization at 600 MPa significantly decreased pH values.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the combined process of UV-TiO2 photocatalysis (UVTP) and high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) on pH values of ginseng powder. Error bars represent standard deviations from the mean (n = 3).

A decrease in the pH value due to HHP can be attributed to structural changes in the plant cell. HHP is known to change the plant cell morphological structure and increase cell wall permeability [31]. Increased cell wall permeability of GP might promote leakage of intracellular acidic components, such as free amino acids and phenolic acids. Large amounts of reducing sugars and free amino acids were extracted from red ginseng using HHP [30].

3.5. Effect of the combined process on antioxidant activity and total phenolic contents of GP

The combined process including UVTP and HHP did not affect the % inhibition of DPPH significantly, based on the GP DPPH radical–scavenging activity (Table 2). DPPH is a naturally stable free radical and has an absorption band at 517 nm in the radical form. However, DPPH loses absorption characteristics after exposure to constituents that have high antioxidant activity levels [32]. Prasad et al [33] did not observe any significant differences in the DPPH radical–scavenging activity and the total phenolic compounds in fresh litchi treated with HHP at 200–500 MPa. However, there are reports regarding the antioxidant activity of red ginseng treated with a low pressure of 100–200 MPa with no consideration of microbiological safety [30], [31].

Table 2.

Effect of combined treatment of UV-TiO2 photocatalysis (UVTP) and high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) on antioxidant activity and total phenolic contents of ginseng powder

| Treatment | 1)DPPH radical–scavenging activity (%) | 2)Total phenolic contents (μg GAE/g-powder) |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 23.26 ± 2.28a | 448.6 ± 23.5b |

| UVTP, 10 min | 22.80 ± 2.61a | 455.0 ± 19.6b |

| HHP 600 MPa, 5 min | 23.60 ± 2.67a | 743.7 ± 115.3a |

| UVTP-HHP | 23.02 ± 1.02a | 769.6 ± 46.3a |

DPPH radical–scavenging activity is expressed as % inhibition of DPPH.

Total phenolic contents are expressed as μg-GAE/g-powder.

Total phenolic contents for an untreated group were 448.6 μg GAE/g-dw, whereas UVTP, HHP, and UVTP-HHP groups exhibited values of 455.0, 743.7, and 769.6 μg GAE/g-dw, respectively (Table 2). HHP changes the cell structure and increases cell wall permeability [30]. Previous reports for fresh produce showed that HHP-treated strawberries and pomegranates showed a significant increase in total phenolic compounds after HHP treatment of above 400 MPa [10]. Lee et al [34] reported that the concentration of the phenolic compounds in ginseng products was increased by pressurization at 600 MPa.

In our study, the percentage of DPPH inhibition was maintained after a high pressure level of HHP treatment, but the total phenol content was increased. Results reported by Kim et al [27] showed that the DPPH radical–scavenging activity of ginseng was low, even though total phenol and saponin contents of a ginseng extract were high. Several possibilities can be considered, including a limitation of the DPPH radical–scavenging activity, destruction of other components instead of phenols that show antioxidant activity, and the extracted quantities of ginsenosides under specific conditions.

Lee et al [34] reported that methods of evaluating antioxidant activity indirectly suffer limitations regarding the reactive spectra of reagents. Even though the DPPH radical–scavenging activity showed a significant difference, the nitric oxide–scavenging activity did not show any significant difference between any two groups. Thus, the DPPH used in this study might not have reacted with certain components in GP that can show an antioxidant activity.

3.6. Antiinflammation activity

Ginseng powder extract (GPE) samples were tested using a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay with RAW 264.7 macrophage cells to determine the effect of GPE on cell viability. Proliferation and cytotoxic effects were examined to establish appropriate GPE concentration ranges for analysis (Fig. 4A). GPE at 100, 200, and 500 ng/mL concentrations had no cytotoxic effects on RAW 264.7 cells and, therefore, were used in further studies. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with LPS (10 ng/mL) for 24 h to examine the inhibitory effect of GPE on LPS-stimulated NO production (Fig. 4B). NO has a central role in inflammation, and the NO level can be quantified using a simple procedure. LPS treatment significantly increased NO production (p < 0.05), compared with a control group, but a simultaneous treatment of GPE significantly inhibited (p < 0.05) NO production at all concentration ranges with 20–30% inhibition. Treatment of cells with 500 ng/mL of UVTP-HHP–treated GPE inhibited NO release by 68.4%. Thus, UVTP-HHP–treated GPE was more effective in suppressing production of NO in macrophages than nontreated GPE. NO induction might be directly correlated with inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and other proinflammatory cytokines. Further study is needed to consider a molecular target for GP with antiinflammatory action.

Fig. 4.

Effect of UV-TiO2 photocatalysis (UVTP) and high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) treatments in ginseng powder extracts. (A) On proliferation and cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 macrophages and LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. (B) On the NO level in LPS-sti. NO, nitric oxide.

4. Conclusion

A novel powder preparation method comprised of UVTP prewashing, wet grinding, HHP pasteurization, and freeze-drying was applied for production of GP. The combined treatment of UVTP with HHP for GP preparation showed synergistic effects on microbial inactivation. The combined process also increased ginsenoside levels in GP. Stronger inhibitory effects against inflammatory mediator production and antioxidant activity were observed in UVTP-HHP–treated GP than in untreated control samples. There were also no significant differences in CIELAB color values of UVTP-HHP–treated GP, compared with untreated control samples.

Nonthermal processing technologies are in their early stages of development compared to the well-established thermal process where the overall processing costs have been reduced over time. Among all novel processing technologies, HHP technology has gained the most industrial success in recent years. Engineering advancements have actually made HHP technology feasible at industrial scale. The capital cost of novel processing technologies may be further decreased in the future with technological advances in process and equipment design, as well as their wider commercial applications. Therefore, the novel powder-manufacturing method presented herein can be a promising alternative for use in the food powder industry.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the cooperative research funding from Holistic Bio. Co., LTD, Korea. The authors would like to thank Sang Jun Lee for the technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2018.11.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kang K.S., Yokozawa T., Kim H.Y., Park J.H. Study on the nitric oxide scavenging effects of ginseng and its compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:2558–2562. doi: 10.1021/jf0529520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung M.Y., Jeon B.S., Bock J.Y. Free, esterified, and insoluble-bound phenolic acids in white and red Korean ginsengs (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) Food Chem. 2002;79:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y., You J., Yu Y., Qu C., Zhang H., Ding L., Li X. Analysis of ginsenosides in Panax ginseng in high pressure microwave-assisted extraction. Food Chem. 2008;110:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin Y., Shin H., Song K.B. Electron beam irradiation improves shelf lives of Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng CA Meyer) and red ginseng. J Food Sci. 2007;72:217–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhandari B., Bansal N., Zhang M., Schuck P. Elsevier; 2013. Handbook of food powders: processes and properties. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicole H., Roger S., Monika E., Sophia J. Characterization of Bacillus cereus group isolates from powdered food products. Int J Food Microbiol. 2018;283:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott W.J. Water relations of food spoilage microorganisms. Adv Food Res. 1957;7:83–127. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maneerat C., Hayata Y. Antifungal activity of TiO2 photocatalysis against Penicillium expansum in vitro and in fruit tests. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006;107:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoo S., Ghafoor K., Kim J.U., Kim S., Jung B., Lee D.U., Park J. Inactivation of Escherichia coli O157: H7 on orange fruit surfaces and in juice using photocatalysis and high hydrostatic pressure. J Food Prot. 2015;78:1098–1105. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shahbaz H.M., Kim J.U., Kim S.H., Park J. Advances in nonthermal processing for enhancing microbiological safety and quality of fresh fruit and juice products. In: Grumezescu A.M., Holban A.M., editors. Food processing for increased consumption. Academic Press; 2018. pp. 179–217. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palou E., Agr-Malo A., Barbosa-Calo A., Barbosag-Chanes J., Swanson B.G. Polyphenoloxidase activity and color of blanched and high hydrostatic pressure treated banana puree. J Food Sci. 1999;64:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vega-Gálvez A., López J., Torres-Ossandón M.J., Galotto M.J., Puente-Díaz L., Quispe-Fuentes I., Di Scala K. High hydrostatic pressure effect on chemical composition, color, phenolic acids and antioxidant capacity of Cape gooseberry pulp (Physalis peruviana L.) LWT Food Sci Technol. 2014;58:519–526. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim K.W., Kim Y.T., Kim M., Noh B.S., Choi W.S. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) treatment on flavor, physicochemical properties and biological functionalities of garlic. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2014;55:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park I., Kim J.U., Shahbaz H.M., Jung D., Jo M., Lee K.S., Lee H., Park J. High hydrostatic pressure treatment for manufacturing of garlic powder with improved microbial safety and antioxidant activity. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H., Ha M.J., Shahbaz H.M., Kim J.U., Jang H., Park J. High hydrostatic pressure treatment for manufacturing of red bean powder: a comparison with the thermal treatment. J Food Eng. 2018;238:141–147. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ando T., Tanaka O., Shibata S. Comparative studies on the saponins and sapogenins ginseng and related crude drugs. Syoyakugaku Zasshi. 1971;25:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim C.S., Kim S.B. Determination of ginseng saponins by reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography. Korean J Med Crop Sci. 2001;9:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau A.J., Woo S.O., Koh H.L. Analysis of saponins in raw and steamed Panax notoginseng using high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection. J. Chromatogr. A. 2003;1011:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(03)01135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee D.G., Lee J., Kim K., Lee S., Kim Y., Cho I., Kim H., Park C., Lee S. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of phytosterols in Panax ginseng root grown under different conditions. J Ginseng Res. 2018;42:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singleton V.L., Orthofer R., Lamuela-Raventos R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;99:152–178. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chien Y.S., Yu Z.R., Koo M., Wang B.J. Supercritical fiuid extractive fractionation: study of the antioxidant activities of Panax ginseng. Sep Sci Technol. 2016;51:954–960. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alpas H., Kalchayanand N., Bozoglu F., Ray B. Interactions of high hydrostatic pressure, pressurization temperature and pH on death and injury of pressure-resistant and pressure-sensitive strains of foodborne pathogens. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;60:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chai C., Lee J., Lee Y., Na S., Park J. A combination of TiO2–UV photocatalysis and high hydrostatic pressure to inactivate Bacillus cereus in freshly squeezed Angelica keiskei juice. LWT-food Sci Technol. 2014;55:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byun M.W., Yook H.S., Kwon O.J., Kang I.J. Effects of gamma irradiation on physicochemical properties of Korean red ginseng powder. Radiat Phys Chem. 1997;49:483–489. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon J.H., Bélanger J.M., Paré J.J. Effects of ionizing energy treatment on the quality of ginseng products. Int J Radiat Appl Instrum Part C Radiat Phys Chem. 1989;34:963–967. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang S., Chen R., Wu H., Wang C. Ginsenoside extraction from Panax quinquefolium L. (American ginseng) root by using ultrahigh pressure. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;41:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim S.J., Murthy H.N., Hahn E.J., Lee H.L., Paek K.Y. Parameters affecting the extraction of ginsenosides from the adventitious roots of ginseng (Panax ginseng CA Meyer) Sep Purif Technol. 2007;56:401–406. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam K.Y. The comparative understanding between red ginseng and white ginseng, processed ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) J. Ginseng Res. 2005;29:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee Y.J., Jin Y.R., Lim W.C., Ji S.M., Choi S., Jang S., Lee S.K. Aginsenoside-Rh1, a component of ginseng saponin, activates estrogen receptor in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. J. Steroid Biochem. 2003;84:463–468. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghafoor K., Kim S.O., Lee D.U., Seong K., Park J. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on structure and colour of red ginseng (Panax ginseng) J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:2975–2982. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen R., Meng F., Zhang S., Liu Z. Effects of ultrahigh pressure extraction conditions on yields and antioxidant activity of ginsenoside from ginseng. Sep Purif Technol. 2009;66:340–346. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brand-Williams W., Cuvelier M.E., Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci Technol. 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prasad N.K., Yang B., Zhao M., Wang B.S., Chen F., Jiang Y. Effects of high-pressure treatment on the extraction yield, phenolic content and antioxidant activity of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) fruit pericarp. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2009;44:960–966. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee D., Ghafoor K., Moon S.Y., Kim S.H., Kim S., Chun H., Park J. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of high hydrostatic pressure and conventionally treated ginseng (Panax ginseng) products. Qual Assur Saf Crop. 2015;7:493–500. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.