Abstract

Preventing and curing complications of acute and chronic pancreatitis, which may be local or systemic, remains a challenge. Pseudocysts and walled-off pancreatic necrosis are two local complications that most frequently require surgical intervention. Two rare complications of pancreatitis are pseudoaneurysms and pulmonary embolism. Angiographic embolization can be the treatment of choice for pseudoaneurysms, while for pulmonary embolism apart from anticoagulation treatment, the optional inferior vena cava filter placement could be useful. As far as we know, in literature, these complications of pancreatitis have never been reported simultaneously yet.

Keywords: pancreatitis, complications, pulmonary embolism, pseudoaneurysm, pseudoaneurysm of gastroduodenal artery, angiographic embolization

INTRODUCTION

Both acute and chronic pancreatitis can lead to plenty arterial and venous complications, such as pseudoaneurysm and splanchnic vein thrombosis [1]. A bleeding pseudoaneurysm is a rare and lethal complication of pancreatitis with mortality rates up to 40% [2]. Successful hemostasis has been reported with angiographic embolization in 74% of cases [1]. In addition, pancreatic inflammation has been associated with thrombogenic situations, with pulmonary embolism being an extremely rare and morbid complication [3].

We present a case of two rare complications of acute pancreatitis (AP). Bleeding pseudoaneurysm and pulmonary embolism have never been reported before simultaneously in the same patient.

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old Caucasian man presented with nausea, abdominal distension, progressive cramps, abdominal pain and vomiting appearing shortly after meal. Laboratory tests revealed white blood cells 13100/μL, hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL, transaminases were quite elevated (AST/ALT = 130/80), serum amylase was 455 IU/L, urine amylase was 5217 IU/L, total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were in normal range. His past medical history includes nine episodes of acute alcoholic pancreatitis and long-lasting alcohol abuse, while his past surgical history includes a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Upper abdominal magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (Fig. 1) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 2) revealed large walled-off pancreatic necrosis in the pancreatic head, measuring 10.5 × 6.5 × 9 cm, compressing the inferior vena cava, the common bile duct and the duodenum. There were also peripancreatic pseudocysts, with the biggest measuring at 12.5 cm.

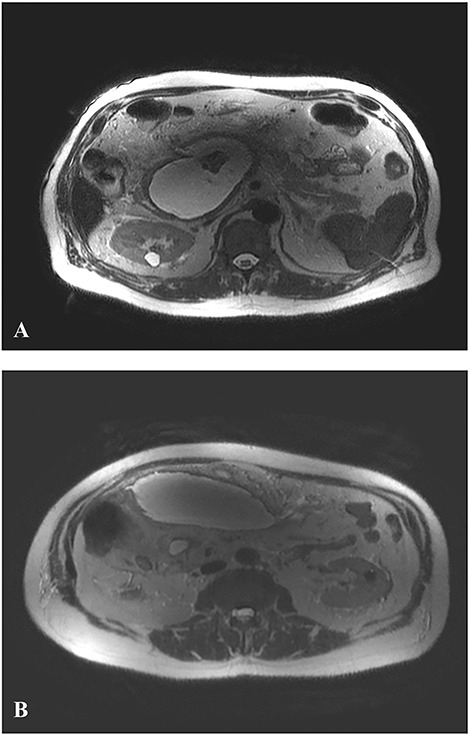

Figure 1.

Axial T2-weighted MR image. A. WOPN: large pancreatic collection with hyperintense fluid and hypointense non-liquefied components (debris) pressing inferior vena cava. B. Peripancreatic pseudocysts.

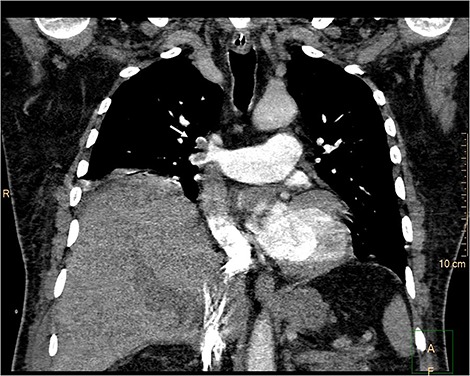

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT. Large walled-off pancreatic necrosis in the pancreatic head, pressing inferior vena cava and duodenum (white arrow).

Initially, a conservative approach was decided, but the pain was worsening and six days after his admission, a new CT had shown an increased in size fluid collections. Then, a decision was made to proceed cystogastrostomy of the walled-off pancreatic necrosis and drainage of fluid collections was made.

At the postoperative day seven, the patient was presented with progressive dyspnea with sinus tachycardia and tachypnea > 20 per minute. A CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) revealed pulmonary embolism (Fig. 3). The patient had started anticoagulation treatment with a low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparine) in therapeutic doses, and five days later, the patient was discharged with instructions to continue anticoagulation treatment.

Figure 3.

CTPA. Pulmonary embolism. Filling defect (white arrow) of the upper lobar artery (truncus anterior) and the descending interlobar artery.

Twelve hours after his discharge, the patient presented to emergency room with multiple episodes of hematemesis. From the clinical examination, he was hemodynamically stable with increased pulses >100 per minute, arterial pressure in a normal range and from his blood tests, hemoglobin was measured 9.0 g/dL (Hb = 11.0 g/dL the previous day). An emergency upper GI endoscopy was performed with signs of recent but not active bleeding.

After the negative GI endoscopy for active bleeding, contrast-enhanced CT in the arterial phase was performed and revealed a pseudoaneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery with a diameter of 9 mm, and a second smaller pseudoaneurysm of a branch of gastroduodenal artery were demonstrating (Fig. 4). Furthermore, celiac-mesenteric trunk and worsening image of pancreatitis were depicted (Fig. 5). After that, emergency embolization of the pseudoaneurysms was performed, using a 4-F arterial sheath via the Seldinger technique. A celiac angiogram was obtained with a 4-F angiographic catheter type Cobra (Medical Materials, Boynton Beach, Florida, USA). Using microcatheter Asahi Caravel (Asahi-Intecc USA Medical, Tustin, California, USA), microcatheter SwiftNinja (Merit Medical, South Jordan, Utah, USA) and microcoils of (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA) 2.5 and 3 mm, complete embolization of the two pseudoaneurysms was achieved (Fig. 6).

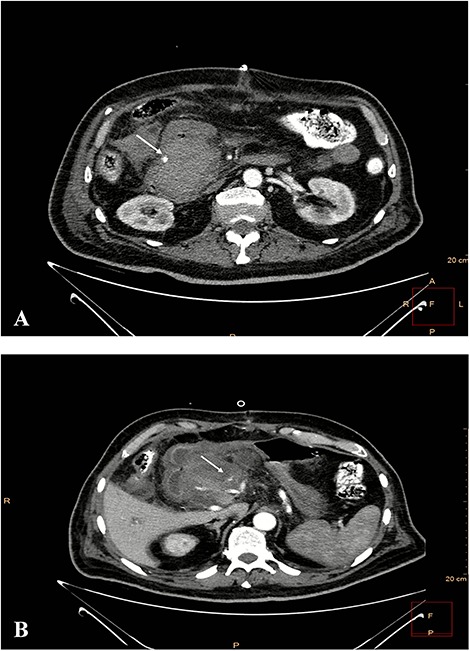

Figure 4.

Contrast-enhanced CT in arterial phase. A pseudoaneurysm of gastroduodenal artery with a diameter of 9 mm (white arrow). B. Smaller pseudoaneurysm of a branch of gastroduodenal artery (white arrow).

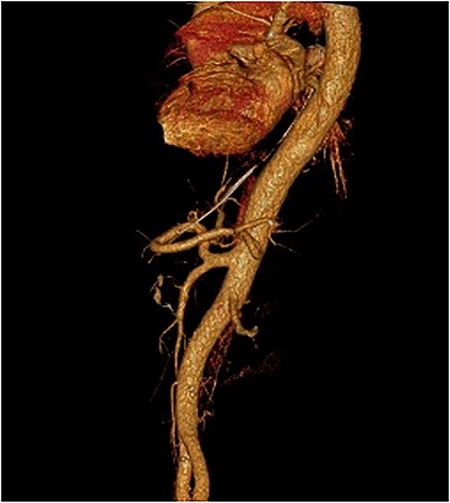

Figure 5.

3D-CTA. Celiac-mesenteric trunk.

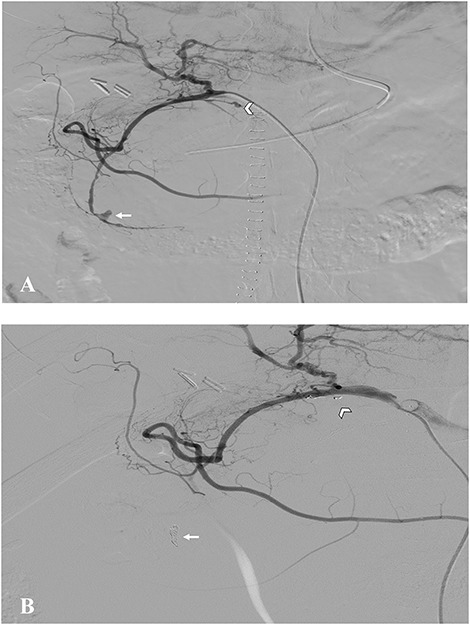

Figure 6.

Digital subtraction angiography. A. Pseudoaneurysm of gastroduodenal artery (arrow) and a branch of it (arrow head). B. Postembolization images showing absence of blood flow into the pseudoaneurysms.

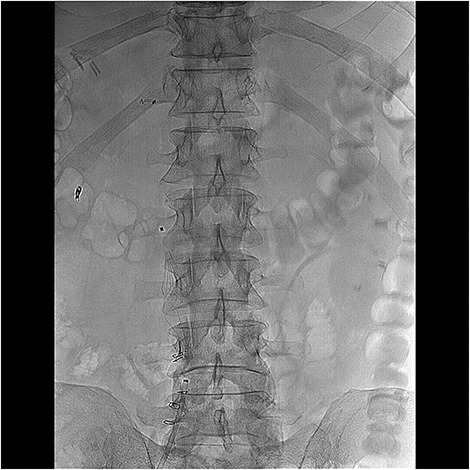

Considering the pulmonary embolism and the contraindications for anticoagulation therapy, a retrievable inferior vena cava filter type Angel (Mermaid medical, Copenhagen, Denmark) had been placed (Fig. 7). The patient had total recovery and was discharged the postoperative day 14 overall. He remains asymptomatic 6 months after.

Figure 7.

Placement of retrievable inferior vena cava filter.

DISCUSSION

Necrotizing pancreatitis is a severe complication of acute pancreatitis with high morbidity (34–95%) and mortality (2–39%). Walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) is developed after 4 weeks from the onset of pancreatitis and refers to encapsulated fluid with heterogeneous non-liquefied material (debris) [2].

A bleeding pseudoaneurysm is a rare and sometimes fatal complication of chronic and AP, involving most often splenic artery (up to 10% of patients with necrotic pancreatitis) [4]. A pseudoaneurysm can be found in almost every visceral artery, but most common in arteries proximal to pancreas such as splenic (46%), renal (22%), hepatic (16.2%) and only 1.5% of all cases involve the gastroduodenal artery [5]. Three main pathogenic mechanisms have been suggested for pseudoaneurysm development: severe inflammation and enzymatic autodigestion, a pseudocyst eroding into a visceral artery and bowel wall causing bleeding from the mucosal surface [6]. The current standard of therapy of pseudoaneurysms is endovascular transarterial catheter embolization or placement of a covered stent. Patients who cannot undergo embolization or embolization is not successful, surgery remains the only option [5].

Pulmonary embolism (PE) in AP has been reported to be very rare, with only few cases reported in the literature. The prevalence of venus thromboembolism among hospitalization patients with AP was 0.93% as having concurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE); while 80% had deep venous thrombosis (DVT) alone, 15% had PE alone, and 5% had both DVT and PE [7]. AP is thought to be a hypercoagulable state [4]. Some researchers consider as risk factors of thrombogenesis in acute pancreatitis; inflammation, male sex and alcohol abuse [8] and as multiple mechanisms of thrombogenesis, the role of vasculitis due to pancreatic enzymes penetrating vessels through cyst and pancreatic duct communication [3]. Failure of anticoagulation treatment, high risk of hemorrhagic complications, recent PE and medical status of the patient were main indications for placement of a vena cava filter as prophylactic management to avoid recurrent pulmonary embolism [9].

The coexistence of pseudoaneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery and its branch and pulmonary embolism as rare complications of AP has not been reported in the literature yet. Diagnosis and management require high clinical suspicion and expertise. The decision of therapeutic management is crucial because the physician has to balance hemorrhagic and thrombotic complications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

References

- 1. Mendelson Richard M, James A, Martin M, Duscan R. Vascular complications of pancreatitis. ANZ J Surg 2005;75:1073–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balachandra S, Siriwardena AK. Systematic appraisal of the management of the major vascular complications of pancreatitis. Am J Surg 2005;190:489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Q, Zhang Q-X, Tan X-P, Wang W-Z, He C-H, Xu L, et al. Pulmonary embolism with acute pancreatitis: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:583–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shyu JY, Sainani NI, Sahni VA, Chick JF, Chauhan NR, Conwell DL, et al. Necrotizing pancreatitis: diagnosis, imaging, and intervention. Radiographics 2014;34:1218–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Habib N, Hassan S, Abdou R, Torbey E, Alkaied H, Maniatis T, et al. Gastroduodenal artery aneurysm, diagnosis, clinical presentation and management: a concise review. Ann Surg Innov Res 2013;7:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsu J-T, Yeh C-N, Hung C-F, Chen H-M, Hwang T-L, Jan Y-Y, et al. Management and outcome of bleeding pseudoaneurysm associated with chronic pancreatitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2006;6:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trikudanathan G, Umapathy C, Munigala S, Gajendran M, Conwell D, Freeman M, et al. Venous thromboembolism is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients with acute pancreatitis: a population-based cohort study. Pancreas 2017;46:1165–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herath HMMTB, . Pahalagamage SP. Pulmonary embolism in acute pancreatitis: a rare but potentially lethal complication. J Vasc 2016;2:doi:10.4172/2471-9544.100118. [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeYoung E, Minocha J. Inferior vena cava filters: guidelines, best practice, and expanding indications. Semin Intervent Radiol 2016;33:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]