ABSTRACT

Mutations that activate the RAS oncoproteins are common in cancer. However, aberrant upregulation of RAS activity often occurs in the absence of activating mutations in the RAS genes due to defects in RAS regulators. It is now clear that loss of function of Ras GTPase-activating proteins (RasGAPs) is common in tumors, and germline mutations in certain RasGAP genes are responsible for some clinical syndromes. Although regulation of RAS is central to their activity, RasGAPs exhibit great diversity in their binding partners and therefore affect signaling by multiple mechanisms that are independent of RAS. The RASSF family of tumor suppressors are essential to RAS-induced apoptosis and senescence, and constitute a barrier to RAS-mediated transformation. Suppression of RASSF protein expression can also promote the development of excessive RAS signaling by uncoupling RAS from growth inhibitory pathways. Here, we will examine how these effectors of RAS contribute to tumor suppression, through both RAS-dependent and RAS-independent mechanisms.

KEY WORDS: RAS, RASSF, GAP, RASA1, NF1, RASAL2, DAB2IP

Summary: The activity of the critical oncoprotein RAS can be negatively regulated by two groups of proteins, GAPs and RASSF proteins, as reviewed here.

Introduction

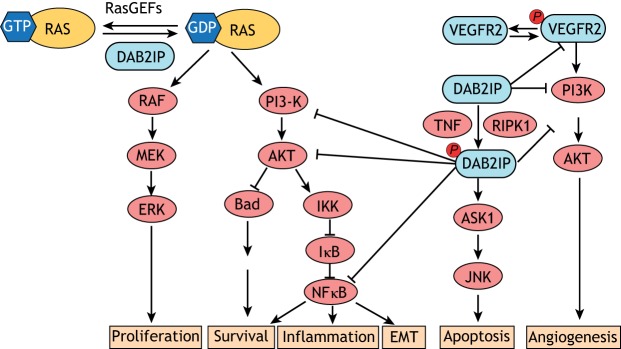

The RAS GTPases H-RAS, K-RAS and N-RAS are proto-oncoproteins that are frequently activated in human cancer (Prior et al., 2012). Although part of a superfamily of over 150 members, these three GTPases share high sequence and structural identity. However, there are some variable regions, as well as differences in post-translational modification (Hobbs et al., 2016). The RAS genes exhibit gain-of-function point mutations in 25% to 30% of tumors, although mutation rates in individual tumor types vary widely from less than 5% in breast cancer to upwards of 90% in pancreatic cancer (Prior et al., 2012; Zhang and Cheong, 2016). Some tumor types are associated with a specific RAS gene. For instance, pancreatic tumors almost always harbor KRAS mutations. The basis for this tissue-specific difference in mutation frequency remains unresolved (Hobbs et al., 2016). Activation of RAS proteins stimulates multiple signaling cascades that control metabolism, proliferation and transformation. Two of the best characterized effector pathways of the RAS proteins are the RAF–MEK–ERK and PI3K–AKT pathways (Fig. 1) (Chong et al., 2003; Cox and Der, 2003).

Fig. 1.

Canonical RAS signaling. RAS is able to activate multiple signaling cascades regulating growth, survival and metabolism. The first downstream effector of RAS identified was the serine/threonine kinase RAF. Activation of RAF initiates the RAF–MEK–ERK kinase cascade. At its terminus, phosphorylated ERK (ERK1/2, also known as MAPK3 and MAPK1, respectively) translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription factors that promote cell cycle progression and inhibit apoptosis. Additionally, RAS can activate PI3K and promote PI3K-AKT signaling. AKT, also known as protein kinase B (PKB), phosphorylates and inhibits Bad, thus derepressing the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. AKT also activates IκB kinase (IKK), which in turn phosphorylates IκB, thus resulting in the derepression of the anti-apoptotic transcription factor NFκB. NFκB translocates to the nucleus where it activates genes promoting cell survival, migration and EMT.

While historical interest has focused on the role of the mutant forms of RAS in cancer, many tumors exhibit activation of RAS signaling in the absence of mutations in RAS genes (Ji et al., 2012; Basu et al., 1992; Downward, 2003). For example, elevated RAS pathway activity is present in more than 50% of human breast tumors – particularly in highly aggressive subtypes, even though they seldom exhibit RAS mutations and are commonly considered to be a ‘non-RAS’ tumor type (von Lintig et al., 2000; Sears and Gray, 2017; Siewertsz van Reesema et al., 2016). Therefore, enhanced RAS activity in the absence of activating mutations of the RAS genes is likely to play an important role in human disease.

The main mechanisms of deregulation of wild-type RAS signaling in cancer can be placed into two broad categories: excessive activation of positive regulators of RAS or loss of function of negative regulators.

Excessive activation

The RAS proteins function as classical molecular binary switches, cycling between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound states. The ability to exchange GDP for GTP is intrinsic to RAS; however, by itself, this activity is low. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) activate RAS by binding to RAS-GDP and facilitating GDP-GTP exchange (Bos et al., 2007). RAS is anchored to the inner leaflet of the cell membrane through a farnesyl group, which is critical for its regulation by membrane-bound receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Upon ligand binding, for instance, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activation by epidermal growth factor (EGF), RasGEFs are recruited to the membrane and interact with and activate RAS (Bos et al., 2007).

Such a mechanism of activation has several potential points of failure, at which RAS signaling can become disordered. Aberrant autocrine and/or paracrine signaling through growth factors, such as EGF, transforming growth factor (TGF) and insulin-like growth factor (IGF), has long been known to promote malignancy (Walsh et al., 1991). Furthermore, GPCRs and RTKs can be directly affected by multiple pathological insults, including transcriptional overexpression, mutational activation and loss of negative regulators, among others (Du and Lovly, 2018). GEFs may also become dysregulated and so promote oncogenesis. Recently, overexpression of RacGEFs and RhoGEFs has been shown to promote breast and colon cancer progression (Liao et al., 2012; Barrio-Real et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2019). GEFs can also be mutationally activated. Germline mutations in the RasGEF gene SOS1 account for 10% to 15% of cases of Noonan syndrome, part of a group of clinical syndromes characterized predominantly by craniofacial defects and cardiovascular abnormalities (Lepri et al., 2011). Noonan syndrome and the related Costello and cardiofaciocutaneous syndromes are all driven by excessive RAS–ERK signaling (Roberts et al., 2006).

Loss of negative regulation

Just as GTP loading is tightly regulated in normal tissue, the GTPase activity of RAS is under the control of a family of regulatory proteins called GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). Although GTPase activity is intrinsic to RAS proteins, their rate of GTP hydrolysis is slow, and binding of GAPs increases this rate by a factor of up to 105 (Resat et al., 2001). Consequently, loss of RasGAPs, either through loss-of-function mutation or epigenetic inactivation, results in an accumulation of GTP-bound RAS and therefore increased signaling through RAS-regulated pathways. Multiple RasGAPs are downregulated in human cancers, and their loss tends to correlate with poorer prognosis in patients (Zhou et al., 2016; Calvisi et al., 2011; Olsen et al., 2017; Min et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2007; Dischinger et al., 2018).

In addition to the RasGAPs, another family of proteins, the Ras association domain family (RASSF), can directly bind to RAS in a GTP-dependent manner and their inactivation can promote RAS-mediated transformation. There is an increasing body of evidence demonstrating that oncogenic RAS has the ability to induce cell death. While much regarding this anti-tumor activity of RAS signaling is yet to be discovered, RASSF proteins have been identified as key mediators of these effects. Several RASSF proteins have been shown to scaffold activated RAS to pro-apoptotic and pro-senescent effector proteins, particularly novel RAS effector 1a (NORE1A, also known as RASSF5) and RASSF1A, the major isoform encoded by the RASSF1 gene (Donninger et al., 2016a,b, 2007; Barnoud et al., 2017; Matallanas et al., 2007; Law et al., 2015; Baksh et al., 2005). Recently, we discovered that Rassf1a-knockout mice exhibit elevated signaling through mitogenic RAS effector pathways compared to wild-type controls, namely RAF–MEK–ERK and Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator (RalGDS) pathways (Schmidt et al., 2018). RASSF1A may therefore act to directly suppress RAS activation in addition to mediating RAS-dependent apoptosis.

Like RasGAPs, the regulation and activities of the RASSF proteins are complex and varied. The family of ten can be divided into two groups: RASSF1 to RASSF6, which contain the coiled-coil motif called Salvador-RASSF-Hippo (SARAH), and RASSF7 to RASSF10 that do not (Iwasa et al., 2018). The classical RASSF proteins, RASSF1 to RASSF6, all have multiple isoforms derived from either alternative splicing or use of an internal promoter. Furthermore, each has unique RAS-dependent and -independent functions (Donninger et al., 2016b). The expression of RASSF proteins is frequently downregulated in tumors, primarily owing to promoter hypermethylation. In fact, hypermethylation of the RASSF1 promoter is among the most frequent methylation events in human cancer (Hesson et al., 2007).

In this Review, we will focus on examining the implications of these negative regulator and effector proteins on RAS signaling and demonstrate how their inactivation contributes to RAS-mediated transformation. First, we will discuss the best characterized members of the RasGAP family, p120GAP (also known as RASA1), NF1, RASAL2 and DAB2IP, in terms of both their GAP activity and RAS-independent effects. Next, we will turn our attention to the anti-tumor activities of RASSF1A and NORE1A, the most relevant RASSF family members in the context of cancer. Finally, the potential for interplay between these two families of negative RAS effectors will be considered.

The RasGAP family

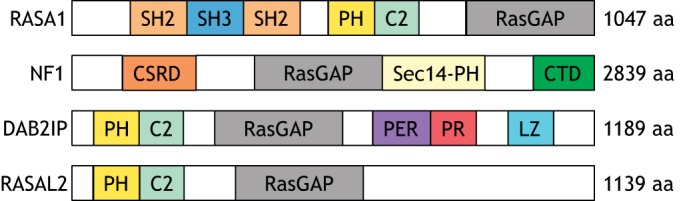

In cancer, RAS genes are most commonly rendered oncogenic from missense point mutations in codons 12, 13 and 61 (Prior et al., 2012). Early studies on RAS proteins attempting to explain the mechanism of action of the point mutations were puzzling, as they only had a modest effect on the intrinsic GTPase activity of the purified protein, yet in cells, the respective mutant RAS protein exhibited much higher levels of GTP association than the wild-type form. This puzzle was resolved when a protein factor in membrane preparations was found to be able to stimulate the GTPase activity of wild type, but not mutant RAS protein (Trahey and McCormick, 1987). This factor, a 120 kD protein was named GAP (Trahey et al., 1988; Vogel et al., 1988), and it is also now known as RAS p21 protein activator 1 (RASA1) or p120GAP. The GTPase-stimulating activity was found to reside in the C-terminus of the protein, referred to as the GAP domain (Marshall et al., 1989). Three years later, the causative gene of the hereditary neurocutaneous syndrome neurofibromatosis type one (NF1), was cloned and shown to have homology to the GAP domain of RASA1 (Ballester et al., 1990; Marchuk et al., 1991). Since then, 12 additional RasGAP genes have been identified in the human genome. Apart from the conserved GAP domain, members of the RasGAP family show little sequence or structural similarity (Fig. 2). Consequently, several of the family members have been shown to participate in a wide array of cellular processes that are distinct from their GAP activities (King et al., 2013).

Fig. 2.

Domain organization of RasGAPs. All RasGAPs contain a GAP domain or GAP-related domain (RasGAP). Apart from that, the RasGAP family is quite diverse in terms of domain composition and arrangement. The GAP domain of RASA1 is at its C-terminus. C2 and plekstrin homology (PH) domains facilitate membrane binding, while the N-terminal SH2 and SH3 domains promote protein-protein interactions. NF1 contains a lipid-binding Sec14-PH module that targets it to membranes. This protein also contains a cysteine/serine-rich domain (CSRD), which can be phosphorylated to modulate NF1 function, and the C-terminal domain (CTD). As members of the SynGAP subfamily, DAB2IP and RASAL2 have N-terminal PH and C2 domains and a centrally located GAP domain. For DAB2IP, the period-like domain (PER) and proline-rich region (PR), which are responsible for binding to TNFR and transducing TNF-mediated apoptosis, are C-terminal to the GAP domain. At the extreme C-terminus lies the leucine zipper (LZ) domain.

RASA1

In addition to its catalytic GAP domain, RASA1 contains Src homology 2 and 3 (SH2 and SH3, respectively) domains, as well as a plekstrin homology (PH) and protein kinase C2 homology (C2) domains (Fig. 2). These domains mediate the targeting of RASA1 to membranes and its interaction with RTKs, thereby facilitating the binding to and inactivation of RAS (Maertens and Cichowski, 2014; King et al., 2013). Additionally, these non-catalytic domains facilitate interactions between RASA1 and multiple binding partners, which allow for a tight regulation of RASA1 activity.

Among the first discovered physiological roles of RASA1 is the regulation of embryonic blood vessel development (Henkemeyer et al., 1995). Genetic deletion of the Rasa1 locus in mice has been shown to be embryonic lethal. Knockout mouse embryos displayed delayed growth, disrupted vascularization of the yolk sac and increased apoptosis in neuronal tissues at embryonic day (E)9.5 compared to wild-type littermates (Henkemeyer et al., 1995). Germline mutations in the human RASA1 gene were later discovered to cause a group of disorders characterized by capillary and/or arteriovenous malformations (Eerola et al., 2003; Wooderchak-Donahue et al., 2018). More recently, the mechanisms underlying the effect of RASA1 on the vasculature have begun to be elucidated. In an investigation using zebrafish, it was shown that knockdown of the endothelial receptor ephrin type-B receptor 4 (EPHB4) in embryos mimicked the phenotype of vascular abnormalities that was caused by RASA1 knockout and increased cell death in the head region (Kawasaki et al., 2014). It has long been known that RASA1 binds to EPHB4 via its SH2 and SH3 domains (Holland et al., 1997). This interaction regulates the activity of RASA1 towards RAS (Xiao et al., 2012). Exogenous re-expression of wild-type EPHB4, but not mutants deficient for RASA1 binding, restored normal vascular development (Kawasaki et al., 2014). Together, these studies demonstrate the critical role of non-GAP domains in proper RasGAP function. Disrupting interactions between RasGAPs and their non-RAS binding partners can still impair RasGAP-mediated regulation of RAS.

Because RASA1 reduces the levels of active RAS-GTP, it might be logical to assume that RASA1 has a role in tumor suppression; however, such a link between RASA1 and human cancer has been demonstrated only in the last 5 years. Numerous microRNAs (miRs) have been shown both to suppress the expression of RASA1 and to be overexpressed in multiple cancers, including colorectal, lung, hepatocellular and triple-negative breast cancers (Sun et al., 2013, 2015; Shi et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2014; Du et al., 2015). Such a miR-mediated suppression of RASA1 causes the dysregulation of RAS–ERK signaling and promotes proliferation in vitro and in xenograft experiments (Sharma et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2013). miR-mediated suppression of RASA1 in endothelial cells has also been shown to promote angiogenesis (Du et al., 2015; Anand et al., 2010).

Some miRs that regulate RASA1 expression appear to have conflicting effects on cell growth depending on the cell type. Two studies report that miR-182 is overexpressed and downregulates RASA1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and lung squamous cell carcinoma, respectively. However, miR-182 promotes angiogenesis and tumor progression in HCC (Du et al., 2015), while suppressing growth in the lung (Zhu et al., 2014). Similarly, miR-335 suppresses RASA1 expression; however, it is described as a downregulated tumor suppressor in gastric cancer and an overexpressed cancer-associated miR (oncomiR) in colorectal cancer (Xu et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2016). There are numerous instances of miRs having inconsistent and even competing effects on cancer progression. This phenomenon is likely due to a single miR being able to regulate multiple genes, both tumor suppressive and oncogenic ones. Thus the phenotype of a miR depends on the net effect of all the gene expression changes that are under its control (Svoronos et al., 2016). miR-182, for instance, suppresses RASA1 expression but also suppresses cortactin, a protein that favors cancer growth and metastasis by promoting the formation of invadopodia (Zhang et al., 2011; Li et al., 2018). It is therefore more likely that cortactin or some other miR-182 target known for promoting proliferation is responsible for the growth-suppressive effects of miR-182 on lung squamous cell carcinoma.

NF1

At 320 kDa, NF1 is the largest RasGAP; however, it contains the fewest functional domains (Fig. 2). Most critical to its function is its centrally located GAP-related domain (GRD), which binds to RAS-GTP to facilitate GTP hydrolysis and so suppresses RAS signaling (Xu et al., 1990a,b; Ballester et al., 1990; Martin et al., 1990). The full name of the NF1-encoding gene is neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), which derives its name from the familial cancer syndrome with which it is associated (Viskochil et al., 1990; Wallace et al., 1990). Germline mutations in NF1 result in the development of multiple benign peripheral nerve tumors and a predisposition for the development of other neoplasms, including gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs), melanoma and juvenile myelomelogenous leukemia (JMML). Individuals with NF1 mutations may also have café-au-lait spots, bone deformities, intellectual deficits and Lisch nodules (Ly and Blakeley, 2019).

The most obvious and the only fully characterized mechanism of NF1-mediated tumor suppression is its inhibition of RAS through the direct regulation of the levels of RAS-GTP. Indeed, it was noted shortly after the discovery of NF1 that RAS was constitutively activated in tumors of neurofibromatosis patients (Basu et al., 1992). More recently, genomic screening has unearthed the frequent occurrence of somatic NF1 mutations in numerous tumor types, including skin, lung, breast and ovarian cancers (Philpott et al., 2017). Although the contribution of these mutations to aberrant RAS signaling has yet to be investigated in many of these tumor types, NF1 mutations in the context of melanoma and gliomas have been discussed (Maertens and Cichowski, 2014). NF1 also plays a critical role in embryonic development, primarily through its GAP activity. Nf1–/– mice die by E14.5 due to cardiac defects, multi-organ hypoplasia and overgrowth of neural crest-derived tissues (Brannan et al., 1994; Jacks et al., 1994). Conditional knockout of Nf1 in endothelial cells recapitulates the cardiac phenotype of Nf1–/– mice, demonstrating a fundamental role for NF1 in endothelial development (Gitler et al., 2003). Furthermore, normal cardiac architecture can be restored in Nf1–/– mice through the expression of the isolated NF1-GRD, although, surprisingly, the overgrowth of neural crest-derived tissues was reported to persist (Ismat et al., 2006). As its Sec14-PH domain is responsible for lipid binding, it has been suggested that the failure of the isolated GRD to rescue neural crest development is due to its impaired ability to properly target RAS at the lipid membrane (King et al., 2013). This explanation is supported by more recent work in mice in which wild-type NF1 was replaced with a point mutant that was deficient for GAP activity (R1276P) (Yzaguirre et al., 2015). Introduction of the point mutant in both alleles of Nf1 was embryonic lethal, with embryos exhibiting similar morphological features to Nf1–/– embryos. Furthermore, neural crest-specific loss of NF1 GAP activity also phenocopied the defects found in Nf1–/– mice with regard to overgrowth of the adrenal medulla and enlargement of paravertebral sympathetic ganglia (Yzaguirre et al., 2015). If NF1 had activity in neural crest cells distinct from its GAP activity, then a point mutation in the GRD would not have been expected to disrupt neural crest development. Together, these studies demonstrate that the GAP activity of NF1 is essential for endothelial and neural crest development.

Complementary to the direct control of RAS activation by its GRD, NF1 can also modulate the activity of downstream effectors of RAS through its other domains: the cysteine/serine-rich domain (CSRD), the Sec14-PH module and the C-terminal domain (CTD) (Fig. 2). For instance, NF1 can regulate actin cytoskeleton dynamics by suppressing phosphorylation of cofilin (herein referring to both cofilin 1 and 2) (Ozawa et al., 2005; Vallee et al., 2012). In HeLa cells, suppression of NF1 resulted in elevated cofilin phosphorylation with subsequent formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions (Ozawa et al., 2005). Cofilin phosphorylation is regulated by the RHO–ROCK–LIMK2 pathway (Sumi et al., 1999). RAS activates RHO, and RAS activity was shown to be required for the effects on cofilin observed upon NF1 depletion (Chen et al., 2003; Ozawa et al., 2005). Thus, the GAP activity of NF1 is at least partially responsible for suppression of RHO–ROCK–LIMK2 signaling. Later, it was discovered that the Sec14-PH domain of NF1 binds directly to LIM domain kinase 2 (LIMK2) and prevents its activation by the Rho-associated protein kinases (ROCK1/2). Furthermore, exogenous expression of the NF1 Sec14-PH domain can inhibit LIMK2-mediated phosphorylation of cofilin and formation of actin stress fibers (Vallee et al., 2012). Cofilin is regulated by a parallel pathway involving RAC1, PAK1 and LIMK1, which can also be regulated by RAS (Edwards et al., 1999; Yamauchi et al., 2005). An N-terminal fragment of NF1 containing the CSRD has been shown to inhibit stress fiber and focal adhesion formation by suppressing this pathway, with no effect on RAS or RHO activity (Starinsky-Elbaz et al., 2009). The exact mechanism by which this occurs is currently unknown.

Both the CSRD and the CTD of NF1 have been shown to bind focal adhesion kinase 1 (FAK, also known as FADK1 or PTK2) in an interaction that regulates neuronal function (Kweh et al., 2009). NF1 has been described as a downstream target of FAK, raising the possibility that FAK may regulate NF1 activity through modulating phosphorylation of its CSRD (Tsai et al., 2012; Rad and Tee, 2016). Thus, NF1 is an important regulator of cytoskeleton dynamics.

DAB2IP

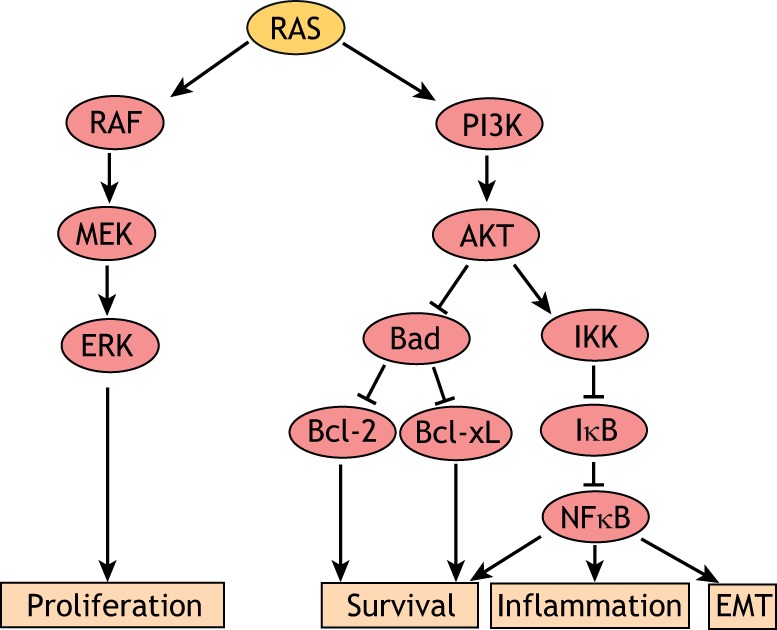

Disabled homolog 2-interacting protein (DAB2IP), also known as ASK1-interacting protein (AIP1), is a member of the SynGAP family of RasGAPs. Relative to the catalytic GRD, DAB2IP contains N-terminal PH and C2 domains, as well as the C-terminal period-like (PER) domain and proline-rich (PR) and leucine zipper (LZ) regions (Zhang et al., 2003) (Fig. 2). These domains allow DAB2IP to serve as a signaling scaffold for crosstalk between multiple pathways that regulate angiogenesis, inflammation, proliferation and apoptosis (Zhang et al., 2008; Xie et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2018; Min et al., 2010). DAB2IP is rarely mutated in cancer; rather, its expression is frequently suppressed by methylation of promoter DNA and histones (Bellazzo et al., 2017). Indeed, loss of DAB2IP expression is considered a driving factor in both the initiation and metastasis of prostate cancer (Min et al., 2010).

DAB2IP suppresses tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms that are both RAS dependent and independent (Fig. 3). It can directly bind to and inhibit signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which controls the expression of anti-apoptotic genes (Zhou et al., 2015) DAB2IP drives tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling towards apoptosis by simultaneously de-repressing apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) and inhibiting TNF-mediated activation of nuclear factor (NF)κB (Zhang et al., 2004). The mechanisms of this have been summarized elsewhere (King et al., 2013; Maertens and Cichowski, 2014); however, a few details should be noted. TNF directly induces the phosphorylation of DAB2IP at Ser-604 by receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), and this phosphorylation event is necessary for DAB2IP-mediated activation of ASK1 and suppression of NFκB (Zhang et al., 2007).

Fig. 3.

Overview of DAB2IP activity in cancer. DAB2IP is involved in a variety of cellular processes that overall confer a tumor-suppressive phenotype. As a RasGAP, DAB2IP can directly inhibit RAS activity by facilitating the hydrolysis of RAS-GTP. This suppresses RAF–MEK–ERK and PI3K–AKT signaling. DAB2IP can also disrupt VEGFR-mediated activation of PI3K by directly binding to activated (phosphorylated) VEGFR. DAB2IP is phosphorylated in a TNF-dependent manner. Phosphorylated DAB2IP can activate pro-apoptotic ASK–JNK signaling and simultaneously suppress TNF-mediated activation of NFκB. DAB2IP can also directly bind PI3K and AKT, inhibiting their activity, and these interactions require DAB2IP phosphorylation.

DAB2IP also promotes apoptosis through inhibition of the RAS effector pathway PI3K–AKT. Obviously, DAB2IP is able to suppress RAS signaling through its GAP domain; however, it also directly suppresses PI3K–AKT signaling by direct inhibition of both phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and AKT family proteins (Min et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2009). Phosphorylation of DAB2IP at Ser-604 is critical to its suppression of PI3K–AKT signaling (Xie et al., 2009). It is important to note that phosphorylation of Ser-604 is not required for GAP activity (Min et al., 2010), nor is GAP activity required for DAB2IP-mediated apoptosis (Xie et al., 2009). Together these studies demonstrate a critical RAS-independent role for DAB2IP in promoting apoptosis through TNF signaling.

Unlike RASA1 and NF1, DAB2IP does not appear to play a critical role in embryogenesis, despite showing distinct tissue-specific expression patterns during fetal development (Zhang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2012). DAB2IP-knockout mice survive through adulthood and largely appear normal; adult mice exhibit increased inflammatory angiogenesis and vascular leakage in two models, with accompanying increases in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression and levels of phosphorylated VEGF receptor (VEGFR) (Zhang et al., 2008). DAB2IP was further shown to have a role in regulating VEGF-induced angiogenesis by directly inhibiting signaling downstream of activated VEGFR2 (Zhang et al., 2008). DAB2IP has also been implicated in brain development, and has been shown to affect neuron and dendrite growth, as well as synapse formation. Indeed, suppression of DAB2IP expression in utero resulted in an abnormal development of both cortical and cerebellar structures (Lee et al., 2012; Qiao et al., 2013; Qiao and Homayouni, 2015). This may involve GAP activity of DAB2IP towards the RAS-related protein RAP1 (RAP1A and RAP1B), which DAB2IP may also regulate (Qiao and Homayouni, 2015)

RASAL2

RASA-like 2 (RASAL2), also known as nematode-like RasGAP (nGAP) is another member of the SynGAP family. Like DAB2IP, RASAL2 also does not appear to have a critical role in embryogenesis, as Rasal2–/– mouse pups are born in Mendelian proportions and survive into adulthood with no obvious phenotypic differences (McLaughlin et al., 2013). Of the RasGAPs discussed here, RASAL2 is the least characterized, and its importance in human disease has only recently begun to be appreciated. The initial investigation into the function of RASAL2 showed that Rasal2–/– mice develop tumors associated with old age earlier than wild-type littermates, involving primarily lung and hepatic tissues (McLaughlin et al., 2013). Additionally, loss of Rasal2 expression promotes the growth and metastasis of mutant p53-driven cancers as well as luminal breast cancer (McLaughlin et al., 2013). This work thus identifies RASAL2 as a tumor and metastasis suppressor.

In humans, RASAL2 expression is frequently suppressed in luminal B breast tumor cell lines and in primary tumors (McLaughlin et al., 2013; Olsen et al., 2017). Strikingly, nearly 25% of luminal B tumors exhibit a concomitant loss of RASAL2 and DAB2IP. These tumors constitute the most aggressive ones, with patients exhibiting markedly decreased relapse-free survival. Moreover, the expression of these RasGAPs cooperatively suppresses transformation and metastasis (Olsen et al., 2017). At least in breast cancer, however, this is not the complete story. RASAL2 has also been characterized as an oncoprotein in triple-negative breast cancer (Yan et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2014). At first glance, this appears to be another example of complex miR interactions causing conflicting reports (Svoronos et al., 2016), but what is actually occurring is far more interesting. Surprisingly, RASAL2 can promote cancer progression by activating the oncoprotein RAC1, a RAS-related small GTPase. This effect of RASAL2 is dependent on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) status of a cell (Feng et al., 2014). This finding is of particular importance as there is currently much debate over whether RASAL2 functions as a tumor suppressor (Li and Li, 2014; Hui et al., 2018a,b, 2017; Jia et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015) or an oncoprotein (Pan et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2017; Stefanska et al., 2014). It appears the answer may depend on the type and aggressiveness of the tumor. Further investigations into whether this phenomenon may explain the conflicting reports on RASA1 activity are warranted.

RasGAPs are the first line of defense against RAS-mediated transformation. Their catalytic GAP domains contribute to tissue homeostasis by greatly reducing the amount of time RAS can transduce signals upon activation. RasGAPs also have effects on cell signaling that are independent of their GAP activity; diversity in the structure of RasGAPs confers unique properties to each family member. These structural and functional differences are responsible for the wide array of clinical manifestations observed upon loss of RasGAP expression. Although loss of GAP activity is primarily pertinent to tumors that retain wild-type RAS, it could also impact some mutant RAS tumors. Certain activating RAS mutations have recently been found to retain some level of GAP sensitivity (Hunter et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2013). In addition, activated RAS mutants can establish autocrine signaling loops which can overstimulate the remaining wild-type isoforms to contribute to transformation (Schneeweis et al., 2018). Thus, RasGAPs may still impact the overall function of mutant RAS.

The RASSF family of negative modulators of RAS

While RasGAPs help to fine tune RAS activity in order to maintain tissue homeostasis, the complex mechanisms of RAS regulation create multiple points of failure at which RAS signaling can become oncogenic (see above). Protective mechanisms have evolved to induce senescence or apoptosis in cells possessing oncogenic RAS (Cox and Der, 2003; Karnoub and Weinberg, 2008). RAS is connected to these tumor suppression pathways primarily through the RASSF family of proteins, which as noted above fall into two homology groups: a core group composed of RASSF1 to RASSF6, which contain a SARAH protein–protein interaction motif, and a second, less related, group composed of RASSF7 to RASSF10 that lack the SARAH motif (Sherwood et al., 2009). All six core RASSF proteins have been implicated in tumor suppression (Donninger et al., 2016b). Moreover, each has been shown to be downregulated in cancer, with methylation of the RASSF1 promoter representing one of the most frequent methylation events in human tumors. Loss of RASSF expression abolishes the connection between RAS and anti-tumor signaling, thus permitting RAS-mediated transformation (Hesson et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2013; De Smedt et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2015; Iwasa et al., 2013). RASSF proteins lack enzymatic activity and instead function as scaffolds to mediate protein-protein interactions. To date, RASSF1A and NORE1A are the best characterized RASSF proteins and have been shown to have key roles in RAS-mediated cell death. We will thus concentrate on these members below.

NORE1A

NORE1A is the founding member of the RASSF family. It was identified in 1998 in a yeast two-hybrid screen as a binding partner for activated RAS (Vavvas et al., 1998). NORE1A is able to induce apoptosis in vitro and in vivo through multiple mechanisms, including through TNF, TRAIL and CD40L (Park et al., 2010; Elmetwali et al., 2016). NORE1A also binds to the kinase MST1 (also known as STK4), a member of the Hippo pathway; however, it does not appear to regulate canonical Hippo signaling and does not interact with any other components of the Hippo pathway (Park et al., 2010). Indeed, the interaction between NORE1A and MST1 is not necessary for NORE1A-mediated tumor suppression (Aoyama et al., 2004).

Although NORE1A has the ability to induce apoptosis, its role in controlling RAS-induced senescence is likely its most important physiological function. Much about RAS-induced senescence remains to be discovered, but activation of the tumor suppressors Rb and p53 have been shown to be critically involved (Bardeesy and Sharpless, 2006). Senescence is significantly inhibited in Nore1–/– MEFs, and these cells become immortalized significantly faster than wild-type MEFs (Park et al., 2010). NORE1A activates the tumor suppressors p53 and Rb, both known mediators of oncogene-induced senescence, in a RAS-dependent manner (Donninger et al., 2016a). Specifically, NORE1A provides a scaffold for the binding of the phosphatase PP1A to Rb, thereby facilitating its dephosphorylation and subsequent activation (Barnoud et al., 2016). NORE1A also binds the kinase homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2) and so scaffolds it to p53. Curiously, formation of the HIPK2–NORE1A–p53 complex does not promote phosphorylation of p53 by HIPK2, which is a pro-apoptotic event. Instead, phosphorylation of p53 is inhibited by NORE1A, and HIPK2 recruits the acetyltransferase p300/CPB-associated factor (PCAF, also known as KAT2B) to acetylate pro-senescent residues on p53 (Donninger et al., 2016a). Thus, NORE1A can regulate the determination between apoptotic and senescent signaling by p53. Moreover, NORE1A promotes the degradation of the p53 inhibitor mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) by targeting the Skp, Cullin, F-box containing complex containing β-TRCP (SCFβ-TRCP) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex to MDM2, further promoting the activity of p53 (Schmidt et al., 2014, 2016).

RASSF1A

RASSF1A is perhaps the best described RASSF protein. Like NORE1A, RASSF1A can bind to MST1, but unlike NORE1A, RASSF1A also binds to MST2 (also known as STK3) and thus is a potent activator of both MST kinases (Oh et al., 2006; Matallanas et al., 2007, 2011; Khokhlatchev et al., 2002). RASSF1A-mediated activation of MST1 or MST2 leads to activation of the Hippo signaling cascade, which terminates in the phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention of the transcription factors yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) and TAZ (also known as WWTR1) (Matallanas et al., 2007). RAS-induced apoptosis is not mediated by YAP sequestration, however, but by RASSF1A-mediated stabilization of p53 (Matallanas et al., 2011). Similar to NORE1A, RASSF1A stabilizes p53 by promoting the degradation of its inhibitor MDM2. RASSF1A achieves this through multiple mechanisms that are distinct from that of NORE1A. First, RASSF1A inhibits the ubiquitin ligase activity of MDM2 through activation of the Hippo pathway (Aylon et al., 2006). Additionally, RASSF1A promotes the autoubiquitination of MDM2 (Song et al., 2008). RASSF1A also promotes mitochondrial apoptosis (Vos et al., 2006).

In addition to scaffolding activated RAS to pro-apoptotic effectors, RASSF1A also mediates tumor suppression by modulating the activity of mitogenic RAS effectors. RASSF1A can suppress the activation of RAF and AKT (Donninger et al., 2016b; Thaler et al., 2009; Romano et al., 2014, 2010). More recently, the effects of RASSF1A on mitogenic signaling of RAS were demonstrated in a transgenic mouse model in which the A isoform of RASSF1 can specifically not be expressed, while expression of the other major isoform, RASSF1C, is retained (Schmidt et al., 2018). Rassf1a+/– mice harboring a doxycycline-inducible Ras mutant (KRasG12D) exhibit elevated RAL, ERK and AKT activation, irrespective of mutational activation of RAS. Moreover, mice with concomitant reduction of Rassf1a expression and oncogenic mutation of Kras develop significantly more tumors than mice with wild-type Rassf1a expression. However, how exactly RASSF1A mediates its tumor suppressive effects remains unknown. Although RASSF1A has been shown to have some effects on AKT and RAF activity, the fact that three RAS pathways are activated in Rassf1a heterozygous mice suggests that RASSF1A may affect the activation state of RAS by unknown mechanisms.

Conclusions

A tight regulation of RAS activation is critical for tissue homeostasis. Aberrant RAS activity is a potent mediator of cellular transformation, and thus multiple protective mechanisms have evolved to both prevent oncogenic RAS signaling and kill cells in which RAS signaling has become unrestrained. RasGAPs play a unique and ever-expanding role in our understanding of both human development and human disease. Their activities within the cell extend far beyond the catalytic activity of their GAP domain. While some RasGAPs have critical roles in embryogenesis and genetic diseases, others are potent tumor suppressors that regulate apoptosis, angiogenesis and transformation. Furthermore, we have recently discovered the ability of these proteins to work cooperatively to modulate cell signaling (our unpublished data). Nevertheless, the majority of RasGAPs in the human genome remain poorly characterized at this point.

The RASSF proteins serve as the second line of defense against RAS-mediated transformation by driving cells with excessive RAS activity to apoptosis or senescence, before transformation can occur. RASSF proteins, particularly RASSF1A, have been implicated in a wide array of cellular processes that, taken together, confer a tumor-suppressive phenotype. The mechanisms by which RASSF proteins mediate these effects are, however, still incompletely understood. In fact, some of the RASSF family members have hardly been investigated at all.

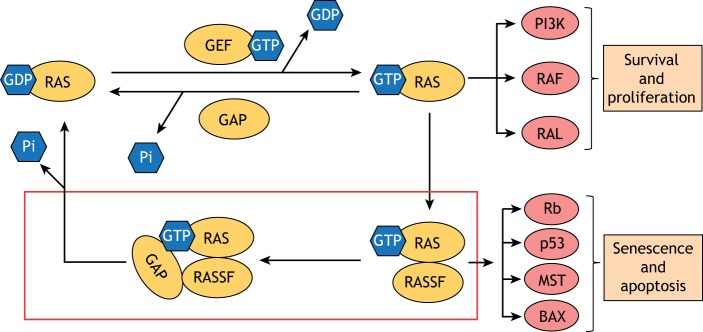

The frequency with which expression of these negative regulators and effectors of RAS are silenced in human cancer highlights their importance in maintaining tissue homeostasis and preventing transformation. In fact, loss of a single regulator of RAS is sufficient to predispose a cell to transformation, as is the case with NF1 and neurofibromatosis. In cancer, the concomitant loss of multiple regulators might have a synergizing effect that creates particularly aggressive and resistant tumors. Overstimulation of RAS owing to loss of RasGAP activity and its uncoupling from apoptotic signaling due to loss of expression of a RASSF protein is likely to result in enhanced cellular transformation. Moreover, we have recently identified a potential link between these classes of RAS suppressors, as we have detected a direct complex formation between RASSF1A and DAB2IP (our unpublished data). As RASSF1A acts as a scaffold protein, one may hypothesize that RASSF1A facilitates the interaction of RAS-GTP with one or more RasGAPs. This could allow RASSF and GAP proteins to work cooperatively to regulate mitogenic signaling through RAS (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Overview of RAS regulation and signaling through effector proteins. RAS is a small GTPase that functions as molecular switch controlling cell growth and survival. Activation and deactivation are controlled by two families of proteins, GEFs and GAPs, respectively. When active, RAS in turn activates pro-proliferative signaling cascades, such as PI3K–AKT, RAF–MEK–ERK and RalGDS. Conversely, RAS can induce apoptosis and senescence by binding a family of effector proteins called RASSF, which function to scaffold active RAS to pro-death proteins, such as the MST kinase and BAX. At least one member of the RASSF family binds to a RasGAP, suggesting that RASSF proteins may directly facilitate the RAS-RasGAP interaction in a feedback mechanism (red box).

The major implication that can be drawn from the work discussed here is that many tumors that do not have an activating mutation in RAS may actually be RAS dependent due to a combination of defects in GAPs and RASSF proteins, leading to hyperactivation of the wild-type RAS protein. Thus, the spectrum of cancers that may be vulnerable to the new generation of direct RAS inhibitors currently under development may be much larger than is currently realized.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Science [5T32ES011564-13]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Anand S., Majeti B. K., Acevedo L. M., Murphy E. A., Mukthavaram R., Scheppke L., Huang M., Shields D. J., Lindquist J. N., Lapinski P. E. et al. (2010). MicroRNA-132-mediated loss of p120RasGAP activates the endothelium to facilitate pathological angiogenesis. Nat. Med. 16, 909-914. 10.1038/nm.2186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama Y., Avruch J. and Zhang X. F. (2004). Nore1 inhibits tumor cell growth independent of Ras or the MST1/2 kinases. Oncogene 23, 3426-3433. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylon Y., Michael D., Shmueli A., Yabuta N., Nojima H. and Oren M. (2006). A positive feedback loop between the p53 and Lats2 tumor suppressors prevents tetraploidization. Genes Dev. 20, 2687-2700. 10.1101/gad.1447006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baksh S., Tommasi S., Fenton S., Yu V. C., Martins L. M., Pfeifer G. P., Latif F., Downward J. and Neel B. G. (2005). The tumor suppressor RASSF1A and MAP-1 link death receptor signaling to Bax conformational change and cell death. Mol. Cell 18, 637-650. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballester R., Marchuk D., Boguski M., Saulino A., Letcher R., Wigler M. and Collins F. (1990). The NF1 locus encodes a protein functionally related to mammalian GAP and yeast IRA proteins. Cell 63, 851-859. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90151-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardeesy N. and Sharpless N. E. (2006). RAS unplugged: negative feedback and oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell 10, 451-453. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnoud T., Donninger H. and Clark G. J. (2016). Ras regulates Rb via NORE1A. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 3114-3123. 10.1074/jbc.M115.697557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnoud T., Schmidt M. L., Donninger H. and Clark G. J. (2017). The role of the NORE1A tumor suppressor in oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Lett. 400, 30-36. 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio-Real L., Benedetti L. G., Engel N., Tu Y., Cho S., Sukumar S. and Kazanietz M. G. (2014). Subtype-specific overexpression of the Rac-GEF P-REX1 in breast cancer is associated with promoter hypomethylation. Breast Cancer Res. 16, 441 10.1186/s13058-014-0441-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu T. N., Gutmann D. H., Fletcher J. A., Glover T. W., Collins F. S. and Downward J. (1992). Aberrant regulation of ras proteins in malignant tumour cells from type 1 neurofibromatosis patients. Nature 356, 713-715. 10.1038/356713a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellazzo A., Di Minin G. and Collavin L. (2017). Block one, unleash a hundred. Mechanisms of DAB2IP inactivation in cancer. Cell Death Differ. 24, 15-25. 10.1038/cdd.2016.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos J. L., Rehmann H. and Wittinghofer A. (2007). GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell 129, 865-877. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan C. I., Perkins A. S., Vogel K. S., Ratner N., Nordlund M. L., Reid S. W., Buchberg A. M., Jenkins N. A., Parada L. F. and Copeland N. G. (1994). Targeted disruption of the neurofibromatosis type-1 gene leads to developmental abnormalities in heart and various neural crest-derived tissues. Genes Dev. 8, 1019-1029. 10.1101/gad.8.9.1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvisi D. F., Ladu S., Conner E. A., Seo D., Hsieh J. T., Factor V. M. and Thorgeirsson S. S. (2011). Inactivation of Ras GTPase-activating proteins promotes unrestrained activity of wild-type Ras in human liver cancer. J. Hepatol. 54, 311-319. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Yang T., Tang D., Zhou F., Qian Y. and Zou X. (2019). Increased expression of GEF-H1 promotes colon cancer progression by RhoA signaling. Pathol. Res. Pract. 215, 1012-1019. 10.1016/j.prp.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. C., Zhuang S., Nguyen T. H., Boss G. R. and Pilz R. B. (2003). Oncogenic Ras leads to Rho activation by activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and decreasing Rho-GTPase-activating protein activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2807-2818. 10.1074/jbc.M207943200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong H., Vikis H. G. and Guan K. L. (2003). Mechanisms of regulating the Raf kinase family. Cell. Signal. 15, 463-469. 10.1016/S0898-6568(02)00139-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox A. D. and Der C. J. (2003). The dark side of Ras: regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene 22, 8999-9006. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt E., Maes K., Verhulst S., Lui H., Kassambara A., Maes A., Robert N., Heirman C., Cakana A., Hose D. et al. (2018). Loss of RASSF4 expression in multiple myeloma promotes RAS-driven malignant progression. Cancer Res. 78, 1155-1168. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dischinger P. S., Tovar E. A., Essenburg C. J., Madaj Z. B., Gardner E. E., Callaghan M. E., Turner A. N., Challa A. K., Kempston T., Eagleson B. et al. (2018). NF1 deficiency correlates with estrogen receptor signaling and diminished survival in breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 4, 29 10.1038/s41523-018-0080-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donninger H., Barnoud T. and Clark G. J. (2016a). NORE1A is a double barreled Ras senescence effector that activates p53 and Rb. Cell Cycle 15, 2263-2264. 10.1080/15384101.2016.1152431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donninger H., Schmidt M. L., Mezzanotte J., Barnoud T. and Clark G. J. (2016b). Ras signaling through RASSF proteins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 58, 86-95. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donninger H., Vos M. D. and Clark G. J. (2007). The RASSF1A tumor suppressor. J. Cell Sci. 120, 3163-3172. 10.1242/jcs.010389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downward J. (2003). Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 11-22. 10.1038/nrc969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du C., Weng X., Hu W., Lv Z., Xiao H., Ding C., Gyabaah O. A., Xie H., Zhou L., Wu J. et al. (2015). Hypoxia-inducible MiR-182 promotes angiogenesis by targeting RASA1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 34, 67 10.1186/s13046-015-0182-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z. and Lovly C. M. (2018). Mechanisms of receptor tyrosine kinase activation in cancer. Mol. Cancer 17, 58 10.1186/s12943-018-0782-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards D. C., Sanders L. C., Bokoch G. M. and Gill G. N. (1999). Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signalling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 253-259. 10.1038/12963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eerola I., Boon L. M., Mulliken J. B., Burrows P. E., Dompmartin A., Watanabe S., Vanwijck R. and Vikkula M. (2003). Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation, a new clinical and genetic disorder caused by RASA1 mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73, 1240-1249. 10.1086/379793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmetwali T., Salman A. and Palmer D. H. (2016). NORE1A induction by membrane-bound CD40L (mCD40L) contributes to CD40L-induced cell death and G1 growth arrest in p21-mediated mechanism. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2146 10.1038/cddis.2016.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J. F., Zhao H. P., Wang Z. F. and Zheng S. S. (2017). Upregulation of RASAL2 promotes proliferation and metastasis, and is targeted by miR-203 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 15, 2720-2726. 10.3892/mmr.2017.6320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng M., Bao Y., Li Z., Li J., Gong M., Lam S., Wang J., Marzese D. M., Donovan N., Tan E. Y. et al. (2014). RASAL2 activates RAC1 to promote triple-negative breast cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 5291-5304. 10.1172/JCI76711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler A. D., Zhu Y., Ismat F. A., Lu M. M., Yamauchi Y., Parada L. F. and Epstein J. A. (2003). Nf1 has an essential role in endothelial cells. Nat. Genet. 33, 75-79. 10.1038/ng1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Wang C., Guo Y., Shen S., Guo X., Kuang G. and Dong Z. (2015). RASSF5A, a candidate tumor suppressor, is epigenetically inactivated in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 32, 83-98. 10.1007/s10585-015-9693-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Dong Z., Guo Y., Shen S., Guo X., Kuang G. and Yang Z. (2016). Decreased expression and frequent promoter hypermethylation of RASSF2 and RASSF6 correlate with malignant progression and poor prognosis of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Mol. Carcinog. 55, 1655-1666. 10.1002/mc.22416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkemeyer M., Rossi D. J., Holmyard D. P., Puri M. C., Mbamalu G., Harpal K., Shih T. S., Jacks T. and Pawson T. (1995). Vascular system defects and neuronal apoptosis in mice lacking ras GTPase-activating protein. Nature 377, 695-701. 10.1038/377695a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesson L. B., Cooper W. N. and Latif F. (2007). The role of RASSF1A methylation in cancer. Dis. Markers 23, 73-87. 10.1155/2007/291538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs G. A., Der C. J. and Rossman K. L. (2016). RAS isoforms and mutations in cancer at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 129, 1287-1292. 10.1242/jcs.182873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland S. J., Gale N. W., Gish G. D., Roth R. A., Songyang Z., Cantley L. C., Henkemeyer M., Yancopoulos G. D. and Pawson T. (1997). Juxtamembrane tyrosine residues couple the Eph family receptor EphB2/Nuk to specific SH2 domain proteins in neuronal cells. EMBO J. 16, 3877-3888. 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui K., Gao Y., Huang J., Xu S., Wang B., Zeng J., Fan J., Wang X., Yue Y., Wu S. et al. (2017). RASAL2, a RAS GTPase-activating protein, inhibits stemness and epithelial-mesenchymal transition via MAPK/SOX2 pathway in bladder cancer. Cell Death Dis. 8, e2600 10.1038/cddis.2017.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui K., Wu S., Yue Y., Gu Y., Guan B., Wang X., Hsieh J.-T., Chang L. S., He D. and Wu K. (2018a). RASAL2 inhibits tumor angiogenesis via p-AKT/ETS1 signaling in bladder cancer. Cell. Signal. 48, 38-44. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui K., Yue Y., Wu S., Gu Y., Guan B., Wang X., Hsieh J. T., Chang L. S., He D. and Wu K. (2018b). The expression and function of RASAL2 in renal cell carcinoma angiogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 9, 881 10.1038/s41419-018-0898-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. C., Manandhar A., Carrasco M. A., Gurbani D., Gondi S. and Westover K. D. (2015). Biochemical and structural analysis of common cancer-associated KRAS mutations. Mol. Cancer Res. 13, 1325-1335. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismat F. A., Xu J., Lu M. M. and Epstein J. A. (2006). The neurofibromin GAP-related domain rescues endothelial but not neural crest development in Nf1 mice. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2378-2384. 10.1172/JCI28341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa H., Kudo T., Maimaiti S., Ikeda M., Maruyama J., Nakagawa K. and Hata Y. (2013). The RASSF6 tumor suppressor protein regulates apoptosis and the cell cycle via MDM2 protein and p53 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 30320-30329. 10.1074/jbc.M113.507384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa H., Hossain S. and Hata Y. (2018). Tumor suppressor C-RASSF proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75, 1773-1787. 10.1007/s00018-018-2756-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T., Shih T. S., Schmitt E. M., Bronson R. T., Bernards A. and Weinberg R. A. (1994). Tumour predisposition in mice heterozygous for a targeted mutation in Nf1. Nat. Genet. 7, 353-361. 10.1038/ng0794-353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Z., Flaherty K. T. and Tsao H. (2012). Targeting the RAS pathway in melanoma. Trends Mol. Med. 18, 27-35. 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z., Liu W., Gong L. and Xiao Z. (2017). Downregulation of RASAL2 promotes the proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of colorectal cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 13, 1379-1385. 10.3892/ol.2017.5581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H., Wang X., Ying J., Wong A. H. Y., Cui Y., Srivastava G., Shen Z.-Y., Li E.-M., Zhang Q., Jin J. et al. (2007). Epigenetic silencing of a Ca(2+)-regulated Ras GTPase-activating protein RASAL defines a new mechanism of Ras activation in human cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 12353-12358. 10.1073/pnas.0700153104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnoub A. E. and Weinberg R. A. (2008). Ras oncogenes: split personalities. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 517-531. 10.1038/nrm2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki J., Aegerter S., Fevurly R. D., Mammoto A., Mammoto T., Sahin M., Mably J. D., Fishman S. J. and Chan J. (2014). RASA1 functions in EPHB4 signaling pathway to suppress endothelial mTORC1 activity. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 2774-2784. 10.1172/JCI67084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlatchev A., Rabizadeh S., Xavier R., Nedwidek M., Chen T., Zhang X.-F., Seed B. and Avruch J. (2002). Identification of a novel Ras-regulated proapoptotic pathway. Curr. Biol. 12, 253-265. 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00683-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King P. D., Lubeck B. A. and Lapinski P. E. (2013). Nonredundant functions for Ras GTPase-activating proteins in tissue homeostasis. Sci. Signal. 6, re1 10.1126/scisignal.2003669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kweh F., Zheng M., Kurenova E., Wallace M., Golubovskaya V. and Cance W. G. (2009). Neurofibromin physically interacts with the N-terminal domain of focal adhesion kinase. Mol. Carcinog. 48, 1005-1017. 10.1002/mc.20552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law J., Salla M., Zare A., Wong Y., Luong L., Volodko N., Svystun O., Flood K., Lim J., Sung M. et al. (2015). Modulator of apoptosis 1 (MOAP-1) is a tumor suppressor protein linked to the RASSF1A protein. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 24100-24118. 10.1074/jbc.M115.648345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. H., Kim S. H., Homayouni R. and D'arcangelo G. (2012). Dab2ip regulates neuronal migration and neurite outgrowth in the developing neocortex. PLoS ONE 7, e46592 10.1371/journal.pone.0046592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepri F., De Luca A., Stella L., Rossi C., Baldassarre G., Pantaleoni F., Cordeddu V., Williams B. J., Dentici M. L., Caputo V. et al. (2011). SOS1 mutations in Noonan syndrome: molecular spectrum, structural insights on pathogenic effects, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum. Mutat. 32, 760-772. 10.1002/humu.21492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N. and Li S. (2014). RASAL2 promotes lung cancer metastasis through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 455, 358-362. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang H., Gong H., Yuan Y., Li Y., Wang C., Li W., Zhang Z., Liu M., Liu H. et al. (2018). miR-182 suppresses invadopodia formation and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer by targeting cortactin gene. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 37, 141 10.1186/s13046-018-0824-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y. C., Ruan J. W., Lua I., Li M. H., Chen W. L., Wang J. R., Kao R. H. and Chen J. H. (2012). Overexpressed hPTTG1 promotes breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis by regulating GEF-H1/RhoA signalling. Oncogene 31, 3086-3097. 10.1038/onc.2011.476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Zhu N. and Chen H. (2012). Expression patterns of human DAB2IP protein in fetal tissues. Biotech. Histochem. 87, 350-359. 10.3109/10520295.2012.664658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Yang H., Yuan L., Liu G., Zhang C., Hong M., Liu Y., Zhou M., Chen F. and Li X. (2016). Overexpression of miR-335 confers cell proliferation and tumour growth to colorectal carcinoma cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 412, 235-245. 10.1007/s11010-015-2630-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly K. I. and Blakeley J. O. (2019). The diagnosis and management of neurofibromatosis type 1. Med. Clin. North Am. 103, 1035-1054. 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertens O. and Cichowski K. (2014). An expanding role for RAS GTPase activating proteins (RAS GAPs) in cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 55, 1-14. 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchuk D. A., Saulino A. M., Tavakkol R., Swaroop M., Wallace M. R., Andersen L. B., Mitchell A. L., Gutmann D. H., Boguski M. and Collins F. S. (1991). cDNA cloning of the type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: complete sequence of the NF1 gene product. Genomics 11, 931-940. 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90017-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M. S., Hill W. S., Ng A. S., Vogel U. S., Schaber M. D., Scolnick E. M., Dixon R. A., Sigal I. S. and Gibbs J. B. (1989). A C-terminal domain of GAP is sufficient to stimulate ras p21 GTPase activity. EMBO J. 8, 1105-1110. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03480.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G. A., Viskochil D., Bollag G., Mccabe P. C., Crosier W. J., Haubruck H., Conroy L., Clark R., O'connell P., Cawthon R. M. et al. (1990). The GAP-related domain of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product interacts with ras p21. Cell 63, 843-849. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90150-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matallanas D., Romano D., Yee K., Meissl K., Kucerova L., Piazzolla D., Baccarini M., Vass J. K., Kolch W. and O'neill E. (2007). RASSF1A elicits apoptosis through an MST2 pathway directing proapoptotic transcription by the p73 tumor suppressor protein. Mol. Cell 27, 962-975. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matallanas D., Romano D., Al-Mulla F., O'neill E., Al-Ali W., Crespo P., Doyle B., Nixon C., Sansom O., Drosten M. et al. (2011). Mutant K-Ras activation of the proapoptotic MST2 pathway is antagonized by wild-type K-Ras. Mol. Cell 44, 893-906. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S. K., Olsen S. N., Dake B., De Raedt T., Lim E., Bronson R. T., Beroukhim R., Polyak K., Brown M., Kuperwasser C. et al. (2013). The RasGAP gene, RASAL2, is a tumor and metastasis suppressor. Cancer Cell 24, 365-378. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min J., Zaslavsky A., Fedele G., McLaughlin S. K., Reczek E. E., De Raedt T., Guney I., Strochlic D. E., Macconaill L. E., Beroukhim R. et al. (2010). An oncogene-tumor suppressor cascade drives metastatic prostate cancer by coordinately activating Ras and nuclear factor-kappaB. Nat. Med. 16, 286-294. 10.1038/nm.2100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H. J., Lee K.-K., Song S. J., Jin M. S., Song M. S., Lee J. H., Im C. R., Lee J.-O., Yonehara S. and Lim D. S. (2006). Role of the tumor suppressor RASSF1A in Mst1-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Res. 66, 2562-2569. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen S. N., Wronski A., Castano Z., Dake B., Malone C., De Raedt T., Enos M., Derose Y. S., Zhou W., Guerra S. et al. (2017). Loss of RasGAP tumor suppressors underlies the aggressive nature of luminal B breast cancers. Cancer Discov. 7, 202-217. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa T., Araki N., Yunoue S., Tokuo H., Feng L., Patrakitkomjorn S., Hara T., Ichikawa Y., Matsumoto K., Fujii K. et al. (2005). The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product neurofibromin enhances cell motility by regulating actin filament dynamics via the Rho-ROCK-LIMK2-cofilin pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39524-39533. 10.1074/jbc.M503707200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Tong J. H. M., Lung R. W. M., Kang W., Kwan J. S. H., Chak W. P., Tin K. Y., Chung L. Y., Wu F., Ng S. S. M. et al. (2018). RASAL2 promotes tumor progression through LATS2/YAP1 axis of hippo signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 17, 102 10.1186/s12943-018-0853-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Kang S. I., Lee S.-Y., Zhang X. F., Kim M. S., Beers L. F., Lim D. S., Avruch J., Kim H.-S. and Lee S. B. (2010). Tumor suppressor ras association domain family 5 (RASSF5/NORE1) mediates death receptor ligand-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35029-35038. 10.1074/jbc.M110.165506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H., Liu H., Zhao S., Wu J., Fan J. and Liao J. (2013). Silencing of RASSF3 by DNA hypermethylation is associated with tumorigenesis in somatotroph adenomas. PLoS ONE 8, e59024 10.1371/journal.pone.0059024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott C., Tovell H., Frayling I. M., Cooper D. N. and Upadhyaya M. (2017). The NF1 somatic mutational landscape in sporadic human cancers. Hum. Genomics 11, 13 10.1186/s40246-017-0109-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior I. A., Lewis P. D. and Mattos C. (2012). A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 72, 2457-2467. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao S. and Homayouni R. (2015). Dab2IP Regulates neuronal positioning, rap1 activity and integrin signaling in the developing cortex. Dev. Neurosci. 37, 131-141. 10.1159/000369092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao S., Kim S.-H., Heck D., Goldowitz D., Ledoux M. S. and Homayouni R. (2013). Dab2IP GTPase activating protein regulates dendrite development and synapse number in cerebellum. PLoS ONE 8, e53635 10.1371/journal.pone.0053635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rad E. and Tee A. R. (2016). Neurofibromatosis type 1: fundamental insights into cell signalling and cancer. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 52, 39-46. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resat H., Straatsma T. P., Dixon D. A. and Miller J. H. (2001). The arginine finger of RasGAP helps Gln-61 align the nucleophilic water in GAP-stimulated hydrolysis of GTP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6033-6038. 10.1073/pnas.091506998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A., Allanson J., Jadico S. K., Kavamura M. I., Noonan J., Opitz J. M., Young T. and Neri G. (2006). The cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 43, 833-842. 10.1136/jmg.2006.042796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano D., Matallanas D., Weitsman G., Preisinger C., Ng T. and Kolch W. (2010). Proapoptotic kinase MST2 coordinates signaling crosstalk between RASSF1A, Raf-1, and Akt. Cancer Res. 70, 1195-1203. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano D., Nguyen L. K., Matallanas D., Halasz M., Doherty C., Kholodenko B. N. and Kolch W. (2014). Protein interaction switches coordinate Raf-1 and MST2/Hippo signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 673-684. 10.1038/ncb2986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. L., Donninger H. and Clark G. J. (2014). Ras regulates SCF(beta-TrCP) protein activity and specificity via its effector protein NORE1A. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 31102-31110. 10.1074/jbc.M114.594283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. L., Calvisi D. F. and Clark G. J. (2016). NORE1A Regulates MDM2 Via beta-TrCP. Cancers (Basel) 8, E39 10.3390/cancers8040039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. L., Hobbing K. R., Donninger H. and Clark G. J. (2018). RASSF1A deficiency enhances RAS-driven lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 78, 2614-2623. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeweis C., Wirth M., Saur D., Reichert M. and Schneider G. (2018). Oncogenic KRAS and the EGFR loop in pancreatic carcinogenesis-A connection to licensing nodes. Small GTPases 9, 457-464. 10.1080/21541248.2016.1262935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears R. and Gray J. W. (2017). Epigenomic inactivation of RasGAPs activates RAS signaling in a subset of luminal B breast cancers. Cancer Discov. 7, 131-133. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S. B., Lin C.-C., Farrugia M. K., McLaughlin S. L., Ellis E. J., Brundage K. M., Salkeni M. A. and Ruppert J. M. (2014). MicroRNAs 206 and 21 cooperate to promote RAS-extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling by suppressing the translation of RASA1 and SPRED1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 4143-4164. 10.1128/MCB.00480-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood V., Recino A., Jeffries A., Ward A. and Chalmers A. D. (2009). The N-terminal RASSF family: a new group of Ras-association-domain-containing proteins, with emerging links to cancer formation. Biochem. J. 425, 303-311. 10.1042/BJ20091318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Middleton J., Jeon Y.-J., Magee P., Veneziano D., Laganà A., Leong H.-S., Sahoo S., Fassan M., Booton R. et al. (2018). KRAS induces lung tumorigenesis through microRNAs modulation. Cell Death Dis. 9, 219 10.1038/s41419-017-0243-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewertsz Van Reesema L. L., Lee M. P., Zheleva V., Winston J. S., O'connor C. F., Perry R. R., Hoefer R. A. and Tang A. H. (2016). RAS pathway biomarkers for breast cancer prognosis. Clin. Lab. Int. 40, 18-23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. J., Neel B. G. and Ikura M. (2013). NMR-based functional profiling of RASopathies and oncogenic RAS mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4574-4579. 10.1073/pnas.1218173110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M. S., Song S. J., Kim S. Y., Oh H. J. and Lim D. S. (2008). The tumour suppressor RASSF1A promotes MDM2 self-ubiquitination by disrupting the MDM2-DAXX-HAUSP complex. EMBO J. 27, 1863-1874. 10.1038/emboj.2008.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starinsky-Elbaz S., Faigenbloom L., Friedman E., Stein R. and Kloog Y. (2009). The pre-GAP-related domain of neurofibromin regulates cell migration through the LIM kinase/cofilin pathway. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 42, 278-287. 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanska B., Cheishvili D., Suderman M., Arakelian A., Huang J., Hallett M., Han Z. G., Al-Mahtab M., Akbar S. M., Khan W. A. et al. (2014). Genome-wide study of hypomethylated and induced genes in patients with liver cancer unravels novel anticancer targets. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 3118-3132. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi T., Matsumoto K., Takai Y. and Nakamura T. (1999). Cofilin phosphorylation and actin cytoskeletal dynamics regulated by rho- and Cdc42-activated LIM-kinase 2. J. Cell Biol. 147, 1519-1532. 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D., Yu F., Ma Y., Zhao R., Chen X., Zhu J., Zhang C. Y., Chen J. and Zhang J. (2013). MicroRNA-31 activates the RAS pathway and functions as an oncogenic MicroRNA in human colorectal cancer by repressing RAS p21 GTPase activating protein 1 (RASA1). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 9508-9518. 10.1074/jbc.M112.367763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D., Wang C., Long S., Ma Y., Guo Y., Huang Z., Chen X., Zhang C., Chen J. and Zhang J. (2015). C/EBP-beta-activated microRNA-223 promotes tumour growth through targeting RASA1 in human colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 112, 1491-1500. 10.1038/bjc.2015.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Yao Y., Lu T., Shang Z., Zhan S., Shi W., Pan G., Zhu X. and He S. (2018). DAB2IP downregulation enhances the proliferation and metastasis of human gastric cancer cells by derepressing the ERK1/2 pathway. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2968252 10.1155/2018/2968252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoronos A. A., Engelman D. M. and Slack F. J. (2016). OncomiR or tumor suppressor? the duplicity of MicroRNAs in cancer. Cancer Res. 76, 3666-3670. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler S., Hahnel P. S., Schad A., Dammann R. and Schuler M. (2009). RASSF1A mediates p21Cip1/Waf1-dependent cell cycle arrest and senescence through modulation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway and inhibition of Akt. Cancer Res. 69, 1748-1757. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trahey M. and Mccormick F. (1987). A cytoplasmic protein stimulates normal N-ras p21 GTPase, but does not affect oncogenic mutants. Science 238, 542-545. 10.1126/science.2821624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trahey M., Wong G., Halenbeck R., Rubinfeld B., Martin G. A., Ladner M., Long C. M., Crosier W. J., Watt K., Koths K. et al. (1988). Molecular cloning of two types of GAP complementary DNA from human placenta. Science 242, 1697-1700. 10.1126/science.3201259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai P. I., Wang M., Kao H. H., Cheng Y. J., Walker J. A., Chen R. H. and Chien C. T. (2012). Neurofibromin mediates FAK signaling in confining synapse growth at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. J. Neurosci. 32, 16971-16981. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1756-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallee B., Doudeau M., Godin F., Gombault A., Tchalikian A., De Tauzia M. L. and Benedetti H. (2012). Nf1 RasGAP inhibition of LIMK2 mediates a new cross-talk between Ras and Rho pathways. PLoS ONE 7, e47283 10.1371/journal.pone.0047283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavvas D., Li X., Avruch J. and Zhang X. F. (1998). Identification of Nore1 as a potential Ras effector. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5439-5442. 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viskochil D., Buchberg A. M., Xu G., Cawthon R. M., Stevens J., Wolff R. K., Culver M., Carey J. C., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A. et al. (1990). Deletions and a translocation interrupt a cloned gene at the neurofibromatosis type 1 locus. Cell 62, 187-192. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90252-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel U. S., Dixon R. A., Schaber M. D., Diehl R. E., Marshall M. S., Scolnick E. M., Sigal I. S. and Gibbs J. B. (1988). Cloning of bovine GAP and its interaction with oncogenic ras p21. Nature 335, 90-93. 10.1038/335090a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Lintig F. C., Dreilinger A. D., Varki N. M., Wallace A. M., Casteel D. E. and Boss G. R. (2000). Ras activation in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 62, 51-62. 10.1023/A:1006491619920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos M. D., Dallol A., Eckfeld K., Allen N. P., Donninger H., Hesson L. B., Calvisi D., Latif F. and Clark G. J. (2006). The RASSF1A tumor suppressor activates Bax via MOAP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4557-4563. 10.1074/jbc.M512128200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M. R., Marchuk D. A., Andersen L. B., Letcher R., Odeh H. M., Saulino A. M., Fountain J. W., Brereton A., Nicholson J., Mitchell A. L. et al. (1990). Type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: identification of a large transcript disrupted in three NF1 patients. Science 249, 181-186. 10.1126/science.2134734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh J. H., Karnes W. E., Cuttitta F. and Walker A. (1991). Autocrine growth factors and solid tumor malignancy. West J. Med. 155, 152-163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Wang J., Su Y. and Zeng Z. (2015). RASAL2 inhibited the proliferation and metastasis capability of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 18765-18771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooderchak-Donahue W. L., Johnson P., Mcdonald J., Blei F., Berenstein A., Sorscher M., Mayer J., Scheuerle A. E., Lewis T., Grimmer J. F. et al. (2018). Expanding the clinical and molecular findings in RASA1 capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 26, 1521-1531. 10.1038/s41431-018-0196-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z., Carrasco R., Kinneer K., Sabol D., Jallal B., Coats S. and Tice D. A. (2012). EphB4 promotes or suppresses Ras/MEK/ERK pathway in a context-dependent manner: Implications for EphB4 as a cancer target. Cancer Biol. Ther. 13, 630-637. 10.4161/cbt.20080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D., Gore C., Zhou J., Pong R.-C., Zhang H., Yu L., Vessella R. L., Min W. and Hsieh J.-T. (2009). DAB2IP coordinates both PI3K-Akt and ASK1 pathways for cell survival and apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 19878-19883. 10.1073/pnas.0908458106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G. F., Lin B., Tanaka K., Dunn D., Wood D., Gesteland R., White R., Weiss R. and Tamanoi F. (1990a). The catalytic domain of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product stimulates ras GTPase and complements ira mutants of S. cerevisiae. Cell 63, 835-841. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90149-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G. F., O'connell P., Viskochil D., Cawthon R., Robertson M., Culver M., Dunn D., Stevens J., Gesteland R., White R. et al. (1990b). The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene encodes a protein related to GAP. Cell 62, 599-608. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90024-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Zhao F., Wang Z., Song Y., Luo Y., Zhang X., Jiang L., Sun Z., Miao Z. and Xu H. (2012). MicroRNA-335 acts as a metastasis suppressor in gastric cancer by targeting Bcl-w and specificity protein 1. Oncogene 31, 1398-1407. 10.1038/onc.2011.340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi J., Miyamoto Y., Tanoue A., Shooter E. M. and Chan J. R. (2005). Ras activation of a Rac1 exchange factor, Tiam1, mediates neurotrophin-3-induced Schwann cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14889-14894. 10.1073/pnas.0507125102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M., Li X., Tong D., Han C., Zhao R., He Y. and Jin X. (2016). miR-136 suppresses tumor invasion and metastasis by targeting RASAL2 in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncol. Rep. 36, 65-71. 10.3892/or.2016.4767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yzaguirre A. D., Padmanabhan A., De Groh E. D., Engleka K. A., Li J., Speck N. A. and Epstein J. A. (2015). Loss of neurofibromin Ras-GAP activity enhances the formation of cardiac blood islands in murine embryos. Elife 4, e07780 10.7554/eLife.07780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F. and Cheong J. K. (2016). The renewed battle against RAS-mutant cancers. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 1845-1858. 10.1007/s00018-016-2155-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., He X., Liu W., Lu M., Hsieh J. T. and Min W. (2003). AIP1 mediates TNF-alpha-induced ASK1 activation by facilitating dissociation of ASK1 from its inhibitor 14-3-3. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1933-1943. 10.1172/JCI200317790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zhang R., Luo Y., D'alessio A., Pober J. S. and Min W. (2004). AIP1/DAB2IP, a novel member of the Ras-GAP family, transduces TRAF2-induced ASK1-JNK activation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44955-44965. 10.1074/jbc.M407617200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zhang H., Lin Y., Li J., Pober J. S. and Min W. (2007). RIP1-mediated AIP1 phosphorylation at a 14-3-3-binding site is critical for tumor necrosis factor-induced ASK1-JNK/p38 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14788-14796. 10.1074/jbc.M701148200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., He Y., Dai S., Xu Z., Luo Y., Wan T., Luo D., Jones D., Tang S., Chen H. et al. (2008). AIP1 functions as an endogenous inhibitor of VEGFR2-mediated signaling and inflammatory angiogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3904-3916. 10.1172/JCI36168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Liu T., Huang Y. and Liu J. (2011). microRNA-182 inhibits the proliferation and invasion of human lung adenocarcinoma cells through its effect on human cortical actin-associated protein. Int. J. Mol. Med. 28, 381-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Ning Z., Wang B., Yun E. J., Zhang T., Pong R. C., Fazli L., Gleave M., Zeng J., Fan J. et al. (2015). DAB2IP loss confers the resistance of prostate cancer to androgen deprivation therapy through activating STAT3 and inhibiting apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1955 10.1038/cddis.2015.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Luo J., Wu K., Yun E.-J., Kapur P., Pong R.-C., Du Y., Wang B., Authement C., Hernandez E. et al. (2016). Loss of DAB2IP in RCC cells enhances their growth and resistance to mTOR-targeted therapies. Oncogene 35, 4663-4674. 10.1038/onc.2016.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. J., Xu B. and Xia W. (2014). Hsa-mir-182 downregulates RASA1 and suppresses lung squamous cell carcinoma cell proliferation. Clin. Lab. 60, 155-159. 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2013.121131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]