Abstract

Objectives:

The Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit 24 (FS-ICU 24) survey consists of two domains (overall care and medical decision-making) and was validated only for family members of adult patients in the ICU. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the internal consistency and construct validity of the FS-ICU 24 survey modified for parents/caregivers of pediatric patients (Pediatric Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit 24 [pFS-ICU 24]) by comparing it to McPherson’s PICU satisfaction survey, in a similar racial/ethnic population as the original Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit validation studies (English-speaking Caucasian adults). We hypothesized that the pFS-ICU 24 would be psychometrically sound to assess satisfaction of parents/caregivers with critically ill children.

Design:

A prospective survey examination of the pFS-ICU 24 was performed (1/2011–12/2011). Participants completed the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey with the order of administration alternated with each consecutive participant to control for order effects (nonrandomized). Cronbach’s alphas (α) were calculated to examine internal consistency reliability, and Pearson correlations were calculated to examine construct validity.

Setting:

University-affiliated, children’s hospital, cardiothoracic ICU.

Subjects:

English-speaking Caucasian parents/caregivers of children less than 18 years old admitted to the ICU (on hospital day 3 or 4) were approached to participate if they were at the bedside for greater than or equal to 2 days.

Measurements and Main Results:

Fifty parents/caregivers completed the surveys (mean age ± SD = 36.2 ± 9.6 yr; 56% mothers). The α for the pFS-ICU 24 was 0.95 and 0.92 for McPherson’s survey. Overall, responses for the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey were significantly correlated (r = 0.73; p < 0.01). The average overall pFS-ICU 24 satisfaction score was 92.6 ± 8.3. The average pFS-ICU 24 satisfaction with care domain and medical decision-making domain scores were 93.3 ± 8.8 and 91.2 ± 8.9, respectively.

Conclusions:

The pFS-ICU 24 is a psychometrically sound measure of satisfaction with care and medical decision-making of parents/caregivers with children in the ICU.

Keywords: care, decision-making, intensive care, parents, pediatric, satisfaction

The Institute of Medicine’s report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (1), outlined components of quality healthcare, including effectiveness, efficiency, timeliness, safety, patient-centeredness, and equity. Patient-centeredness is a complex concept that has been challenging to measure and quantify (2). Nevertheless, patient-centeredness may be reflected in how satisfied patients and their families are with healthcare that they have received (3–7). Family and patient satisfaction with care has become a critical and legitimate part of quality assessment, as well as a valuable outcome measurement in healthcare (8–10). Although there are many concrete and definitive ICU outcome measures, such as survival, length of hospitalization, cost, and others, used to assess aspects of quality healthcare, measuring satisfaction of patients and families is recognized as an important outcome measure to assess healthcare quality and patient-centeredness in the ICU (9–12).

A number of tools are used to assess satisfaction with healthcare, but few are aimed at assessing satisfaction with healthcare in the ICU (13–19). Because patients in the ICU often cannot communicate their medical wishes, decisions, and subsequent satisfaction with healthcare delivery/results, this task is relegated to family members who act on their behalf (20–25). This is even more apparent in the PICU, where parents/caregivers are the primary caretakers and surrogate decision-makers for their children, even when they are not critically ill. However, tools used to assess satisfaction in the PICU are less common (17–19).

McPherson et al (2000), Haines and Childs (2005), and Latour et al (2011) created satisfaction surveys for parents/caregivers of children who are admitted to the PICU (17–19). The three surveys emphasize slightly different domains of satisfaction with the PICU experience. McPherson’s survey focuses more on parent/caregiver satisfaction with the ICU environment and direct patient care experience, but not the assessment of satisfaction with medical decision-making (17). The survey by Haines and Childs focuses on the family’s progression through the PICU. The satisfaction domains that are emphasized include issues related to the child’s admission, information and communication, parental support, the PICU environment and facilities, parents’ perception of the standard of care, and the discharge process (19). Although this survey is fairly comprehensive with regard to satisfaction with the process of care in the PICU, it does not incorporate satisfaction with medical decision-making inclusion, support, or control of the parents/caregivers. The survey by Latour et al (18) is a well constructed and validated tool in which the satisfaction domains include information, care and cure, parental participation, organization, and professional attitude. There is a question directed at parents’/caregivers’ active involvement in decision-making on care and treatment of their children, but satisfaction with medical decision-making is not a major focus.

Heyland et al previously created and validated the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU 24) survey for adult family members of critically ill adults (14, 26, 27). This tool evaluates satisfaction with care and satisfaction with medical decision-making. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of a modified version of the FS-ICU 24—Pediatric Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit 24 (pFS-ICU 24), reflecting the relationship between parents/caregivers and their critically ill children, by comparing this survey with McPherson’s survey. Items in McPherson’s survey match closest to items in the FS-ICU 24. The FS-ICU 24 was chosen because of its strong emphasis on assessing family medical decision-making in the ICU, which is not as strongly highlighted in the other adult ICU or PICU satisfaction surveys. Furthermore, the FS-ICU 24 has been used extensively and has been tested rigorously for validity and reliability (14, 26, 27). We hypothesized that the pFS-ICU 24 would have good internal consistency reliability and construct validity for assessing satisfaction with care and medical decision-making of parents/caregivers who have critically ill children in the ICU setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective evaluation of the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey in a cardiothoracic ICU (CTICU) of a free-standing, quaternary care, children’s hospital was performed between January and December 2011. In order to match the racial/ethnic group of the original FS-ICU 24 and McPherson studies, a convenience sample of English-speaking, Caucasian/European, non-Latino parents/caregivers was chosen for evaluation of the internal consistency reliability and construct validity of the pFS-ICU 24. Parent/caregivers of children less than 18 years old, on the third or fourth day of hospitalization in the CTICU, and present at the bedside of their child for at least 2 days during the hospitalization in the CTICU were identified as potential participants. Eligible parents/caregivers were identified, approached, and consented to participate in the study; then, they were given the surveys to complete on their own by research assistants who were not involved with clinical care (B.O., J.C.C.). Participants completed both the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey, with the order of administration alternated with each consecutive subject to control for order effects (nonrandomized). Only one parent/caregiver per family was enrolled in the study.

Measures

pFS-ICU 24.

The original FS-ICU 24 is a questionnaire with two domains, satisfaction with care and satisfaction with medical decision-making. Excluding demographic questions, the survey contains a total of 24 Likert-scale questions, 14 questions designed to assess satisfaction with care and 10 questions designed to assess satisfaction with medical decision-making. The original FS-ICU 24 questionnaire was obtained from The Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET) website (http://www.thecarenet.ca) and modified for parents/caregivers of critically ill children with guidance from the survey’s creator (28). The number of questions and content of the pFS-ICU 24 remained the same as the original survey; only the context was changed to reflect the parent or caregiver/child relationship in the PICU. For example, the pFS-ICU 24 identified “the patient” as “your child” and referred to the “family members” as “parents/caregivers.” The original FS-ICU 24 had a Cronbach’s α of 0.94 in a sample of mostly English-speaking Caucasian family members of adult ICU patients (89%) (14). The Flesch-Kincaid reading level grade of the pFS-ICU 24 was equivalent to readers of 10–12 years old in the United States.

The pFS-ICU 24 was converted to a score of 0 to 100 (with 0 representing the lowest satisfaction and 100 representing the highest satisfaction). (The Flesch-Kincaid reading level grade may be calculated using the spelling and grammar checking tool in Microsoft Word 2010, in the proofing section, after selecting “show readability statistics.”) A full copy of the pFS-ICU 24 is available in Supplemental Appendix A (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/A64) (29).

McPherson’s Survey.

The survey created by McPherson et al is composed of 23 Likert-scale questions. It was rigorously developed in four stages: 1) item selection, 2) item reduction, 3) pretesting, and 4) testing. Survey test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and content validity were established, but construct validity could not be executed because of the lack of existing validated PICU surveys for comparison at that time (17). The survey’s focus is on the parent’s/caregiver’s satisfaction with care delivered to their child in the PICU, the hospital environment, and communication. The survey contains three quality control items to assess internal reliability (for example: question 4 = nurses respond to my child’s needs promptly; question 11 = nurses respond slowly to my child’s needs). The Cronbach’s α was 0.83 in a sample of mostly Caucasian (52%) and African-American (26%) parents of children in the ICU (English-speaking) (17).

Demographic information was collected in our study for parents/caregivers, but not for the children of these parents/caregivers (Table 1). The surveys were not administered to parents/caregivers of children who died. It was felt that the circumstances of families grieving the loss of a child were distinct, requiring investigation in a more sensitive manner for this vulnerable population of parents/caregivers.

TABLE 1.

Study Group Characteristics

| Group Characteristic | n = 50 |

|---|---|

| Age (mean yr ± SD) | 36.2 ± 9.6 |

| Parent/caregiver, % | |

| Mother | 56 |

| Father | 40 |

| Guardian | 4 |

| Religion, % | |

| Christian | 30 |

| Catholic | 18 |

| Mormon | 6 |

| Jehovah Witness | 6 |

| Other | 18 |

| None | 22 |

| Married, % | 82 |

| Number of siblings (mean ± SD) | 1.3 ± 1.8 |

| Born in the United States, % | 92 |

| ≥ High school graduate, % | 94 |

| Previous admissions (mean ± SD) | |

| Total hospitalizations | 1.3 ± 1.3 |

| Only PICU/cardiothoracic ICU | 0.6 ± 1.0 |

| Parent’s/caregiver’s perceived severity of illness of their child, % | |

| Mild | 0 |

| Moderate | 24 |

| Severe | 76 |

| Weekly income after taxes (mean ± SD) | $1,588 ± 1,133 |

| Insurance, % | |

| Private | 78 |

| Government | 22 |

| None | 0 |

| Occupation, % | |

| Unskilled | 6 |

| Skilled | 12 |

| White collar | 18 |

| Professional | 36 |

| Not employed | 28 |

Statistics

A priori, we determined that the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey would be moderately to highly correlated, given that they both evaluate family members’ perceptions of care provided in the ICU and individual items are similar in the two questionnaires. However, McPherson’s survey does not include items related to medical decision-making. Thus, we further postulated that the pFS-ICU 24 medical decision-making domain would have a lower correlation coefficient with McPherson’s survey compared to the correlation between the pFS-ICU 24 care domain and McPherson’s survey.

In order to establish the a priori probability of moderate correlation between two variables, a group of 50 parents/caregivers was found to be sufficient to provide 80% power to detect correlations as small as 0.4 (α = 0.05, two-tailed test). Demographic data and satisfaction scores were displayed as the mean ± SD or percentage where appropriate. Correlation coefficients were calculated between both surveys and the pFS-ICU 24 care and medical decision-making domains. The Cronbach’s α was calculated for each survey as well. Because individual question responses have been helpful in evaluating more specific areas of satisfaction within each domain, the various responses for each question on the pFS-ICU 24 were separated to show the response proportions (30). The results of the satisfaction survey for each listed question in each of the domains of care and medical decision-making were described, but no specific analysis was performed because the aim of this study was only to evaluate the psychometric properties of the survey tool. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, also known as the Committee on Clinical Investigation at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

RESULTS

In 2011, of 701 admissions to the CTICU, there were 121 patients of English-speaking, Caucasian/European, non-Latino race/ethnicity (17.3%). Of these, 79 patients had a CTICU stay of greater than or equal to 3 days. From this subset, 19 parents/caregivers were not invited to participate because they were not available on the third or fourth day of their child’s hospitalization or because they were not present at their child’s bedside for at least 2 days during the first 3 or 4 days of their child’s hospitalization in the ICU. Of the 60 parents/caregivers who were approached to participate in the study, 50 (83%) completed the survey (Table 1). Of the 10 parents/caregivers who did not complete the survey, two declined to participate and three failed to complete the survey before their children were discharged from the ICU. Three participants did not fully complete the survey due to time constraints, one participant did not meet race/ethnicity inclusion criteria (upon further review), and one participant failed to meet admission inclusion criteria (upon further review). The average age of the participants was 36.2 ± 9.6 years, the majority of them were mothers (56%), born in the United States (92%), married (82%), had at least a high school education (94%), possessed private insurance (78%), and were employed in white collar or professional occupations (54%).

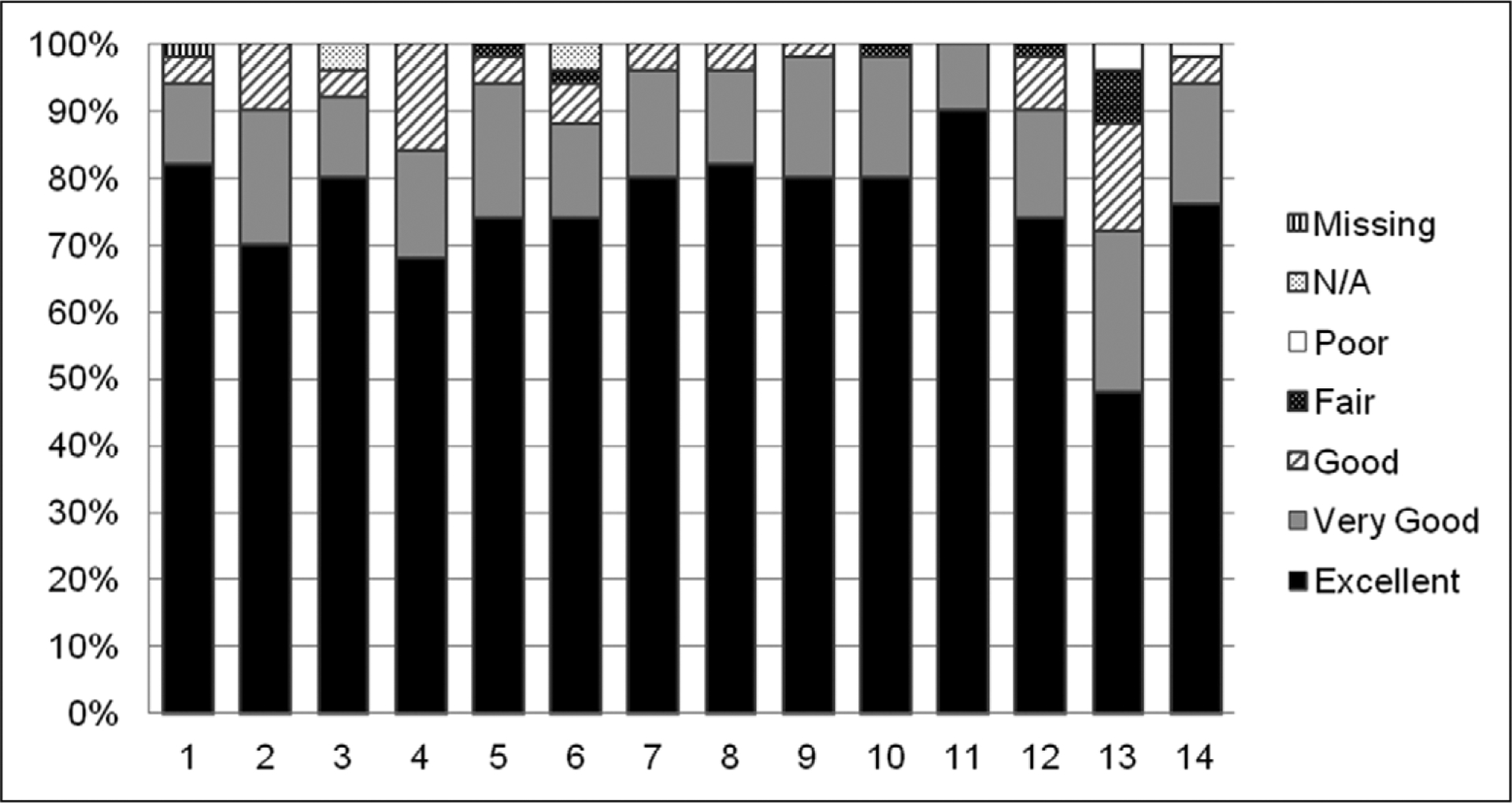

The overall average pFS-ICU 24 satisfaction score for the group was 92.6 ± 8.3. The average pFS-ICU 24 satisfaction with care and medical decision-making scores were 93.3 ± 8.8 and 91.2 ± 8.9, respectively. When screening the response proportions for each question on the pFS-ICU 24, items with a relatively low “excellent” response percentage included the ICU waiting room environment, frequency of communication with physicians, and inclusion, support, and control in the medical decision-making process for parents/caregivers (Figs. 1 and 2). These figures were included for the purpose of showing how the results of the survey can be expressed visually to enable side-by-side comparisons in a format that may be useful for quality and performance improvement in the clinical setting, in addition to the research setting.

Figure 1.

Parent/caregiver satisfaction with care. 1. Courtesy, respect, and compassion toward your child. 2. Symptom management: pain. 3. Symptom management: breathlessness. 4. Symptom management: agitation. 5. Staff showed an interest in family needs. 6. Staff provided family emotional support. 7. Teamwork and coordination of care. 8. Courtesy, respect, and compassion toward family. 9. How well nurses cared for your child--skill and competence. 10. How often nurses communicated to you about your child’s condition. 11. How well physicians cared for your child--skill and competence. 12. Atmosphere of the ICU. 13. Atmosphere of the waiting room. 14. Satisfaction with level of healthcare that your child received in the ICU.

Figure 2.

Parent/caregiver satisfaction with decision-making. 15. Frequency of communication with ICU doctors about your child’s condition. 16. Willingness of ICU caregivers to answer your questions. 17. How well ICU caregivers provided you with explanations that you understood. 18. Honesty of information provided to you about your child’s condition. 19. How well ICU caregivers informed you what was happening to your child and why things were being done. 20. Consistency of information provided to you by the ICU caregivers about your child’s condition. 21. Parent/caregiver feeling included during the decision-making process. 22. Parent/caregiver feeling of support during the decision-making process. 23. Parent/caregiver feeling of control over the care of his/her child. 24. Adequate time to have parent’s/caregiver’s concerns addressed and questions answered [only 2 response options: (1) I could have used more time = poor; (2) I had adequate time = excellent].

Upon reviewing the open-ended comments sections listed at the end of the survey (Supplemental Appendix A, Supplement Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/ A64), there was support for the results expressed in Figures 1 and 2. Although there were many positive comments supporting the high satisfaction in the ICU, there were constructive suggestions as well. For instance, there were multiple comments made concerning the access to, physical comfort, and sleeping accommodations in the waiting area supporting its lower score shown in Figure 1. There were also comments reflecting the desire to have more communication with the physicians. A theme that came to light, which was not reflected in the multiple choice survey questions, was that parents/caregivers desired continuity of nursing care. (“I like having the same nurses for consecutive days.” and “I would have liked it better if the same nurse could have been with us more than 1 day.”) These comments drew attention to more detailed issues not able to be covered in a multiple choice question format (31).

The Cronbach’s α for the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey were 0.95 and 0.92, respectively. The Cronbach’s α for the pFS-ICU 24 care and medical decision-making domains were 0.94 and 0.84, respectively. As postulated, there were significant correlations between the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey. The correlation coefficient for the entire pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson survey was 0.73 (p < 0.01). The correlation with the medical decision-making domain of the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey was less than the correlation with the care domain of the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey (0.62 [p < 0.01] and 0.70 [p < 0.01], respectively). Furthermore, there was a significant correlation between the care domain and the medical decision-making domain of the pFS-ICU 24 (r = 0.72; p < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

In this setting of a pediatric CTICU, the pFS-ICU 24 exhibited good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α > 0.70) and good construct validity (correlation coefficients > 0.60). The overall and domain scores provided important information on the general satisfaction levels. We also found responses to individual questions helpful in evaluating more specific areas of satisfaction within each domain, especially as they were supported by comments provided by the open-ended questions (31). Items that had a lower “excellent” response percentage could be considered opportunities for improvement, such as the atmosphere in the waiting room (Fig. 1) or parents/caregivers feeling included in medical decision-making or communicating with their ICU physicians (Fig. 2). Through use of the written comments, one may surmise that this lower level of satisfaction with medical decision-making may ultimately be due to the perception of less frequent communication between the physicians, who are responsible for medical decision-making, and the parents/caregivers.

There were several pediatric-specific ICU parent/caregiver satisfaction surveys available; however, we used the one developed and validated by McPherson et al for direct comparison (17–19). Although it correlated well with the pFS-ICU 24, McPherson’s survey lacked a specific domain on satisfaction with medical decision-making. Despite this difference, there was a moderate correlation between satisfaction with medical decision-making in the pFS-ICU 24 and McPherson’s survey. This may be explained by the fact that the satisfaction with care and medical decision-making domains within the pFS-ICU 24 were highly correlated with each other and shared a large percentage of variation. Furthermore, some of the medical decision-making domain in the pFS-ICU 24 focuses on communication, which is a focus of McPherson’s survey as well. Although the surveys created by Haines and Childs and Latour et al did not strongly emphasize medical decision-making in the ICU either, we chose the McPherson’s survey because it was a better direct comparison with the pFS-ICU 24 due to the length of the survey and the similarity of satisfaction with care questions.

In this study, care and medical decision-making domains were highly correlated. Although one may argue that satisfaction with care integrates everything having to do with a parent/caregiver experience in the ICU (decision-making included), it is nonetheless important to consider decision-making separate from the delivered patient care. A child’s pain control or cleanliness of a child’s ICU room are important care delivery issues, but how a parent/caregiver is included in medical decision-making is different because it reflects that the parent/caregiver of that child is included in patient care discussions. Although satisfaction with care decisions and actual delivery of care may reflect similar constructs (arguably patient-centeredness), these two domains require separate consideration because the approach to addressing satisfaction with room cleanliness and the decision to withdraw medical support are so clearly different.

In the ICU, substituted decision-makers’ satisfaction with medical decision-making is a reflection of adequate communication, feeling of support, and achievement of the appropriate level of care for their family member (21). This may, in turn, be interpreted as the degree to which a patient or family member feels he/she is heard and respected by the healthcare team. The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Support of the Family in the Patient-Centered Intensive Care Unit recommends that medical decision-making in the ICU be based on a partnership between the patient, his or her appointed surrogate, and the multiprofessional team (20). In particular, a shared decision-making model has been shown to generate fewer decision-making conflicts, create fewer unrealistic family expectations, and improve collaboration between providers and family members, as well as help family members gain a more accurate understanding of the patient’s medical condition (32). The gap between patient and family expectations and perceptions of medical care defines and determines satisfaction (30). The pFS-ICU 24 has the ability to assess the parent/caregiver perceived quality of healthcare and determine the gap between expectations and perception in healthcare delivery.

Even as it is important to assess the degree of satisfaction with care and medical decision-making of parents whose critically ill children are in the ICU, it is more important to use that assessment to improve healthcare. Dodek et al (30) outlined an approach to translating family satisfaction data into critical care quality improvement initiatives. Dodek et al focused on one approach to accomplishing this task using a “Plan-Do-Study-Act” cycle by Langley et al, but there are variations on how to translate satisfaction data into quality improvement (33–36). First, a valid and reliable tool is required to collect the satisfaction data (37). Next, these data must be analyzed and results prioritized in a manner consistent with the mission of the hospital, ICU, or group of healthcare providers. Although general trends in satisfaction with care and medical decision-making are useful, targeting responses to specific survey questions may be more helpful in identifying areas for improvement (14, 30, 38, 39) (Figs. 1 and 2). The effort of focusing on areas of improvement and creating plans for improvement must be multidisciplinary in nature, receiving acceptance from all healthcare providers, not just the leadership group (11, 30, 40). In a patient-centered environment, multiprofessional care is the model (20). Once a plan to improve care is enacted, there should be a plan to reassess the action using the same tool that was used to identify the problem in the first place. This represents the classic “Plan-Do-Study-Act” cycle, so common in quality improvement projects (37, 40, 41). The process of improvement starts and ends with the satisfaction assessment tool, but there is much more work required to create improvement between assessments. The tool that we examined to assess the satisfaction with care and medical decision-making of parents/caregivers with children in the ICU is only the first step in the quality improvement process.

Despite the promising results, our study has a number of limitations. We performed a study to evaluate the pFS-ICU 24 survey’s internal consistency reliability and construct validity; however, content and criterion validity as well as test-retest reliability were not assessed. Because the pFS-ICU 24 and the original FS-ICU 24 were relatively similar, with only subtle changes in wording to denote the parent/caregiver and child relationship in an ICU for children, along with the fact that the original FS-ICU 24 had previously undergone rigorous validity and reliability testing, further validation and reliability testing was not felt to be necessary at this time. The construct validity (establishing that the survey answers what it intends to answer) and internal consistency reliability gives one assurance that the pFS-ICU 24 accurately evaluates satisfaction with care and medical decision-making of parents with children in the ICU. Another limitation was that the participants may have been concerned that their comments would influence the care of their child and this may have caused reporting bias (reporting what they thought the investigators wanted to hear). The reporting bias may have been reduced by the fact that the survey was administered by staff not involved in clinical care, and it was emphasized that the survey results were confidential and participation in the study would not influence the care of their child in any way. Furthermore, variability in comprehension of the questions in the survey may have caused general inaccurate self-reporting (based on misunderstanding). Since the reading age level of the survey was below a majority of subjects’ minimum schooling achievement, misunderstanding of the questions in the sample studied herein seemed less likely. Another limitation of the study was that the study sample may not represent other ICUs for children in other regions of the country or other types of hospitals, since a relatively small sample of participants was primarily obtained from a CTICU at a single institution. In addition, specific diagnoses and demographic information of the children of the parents/caregivers was not obtained and no parents/caregivers of children who died were included in the study. Finally, our investigation included only English-speaking, Caucasian/European, non-Latino parents/caregivers. We have not yet validated the usefulness of the pFS-ICU 24 in different racial/ethnic groups with different languages.

The pFS-ICU 24 is a psychometrically sound tool to assess the satisfaction with care and medical decision-making of parents/caregivers with children hospitalized in the ICU. Because we studied only English-speaking, Caucasian/European, non-Latino parents/caregivers, additional investigation is necessary to establish the usefulness of the pFS-ICU 24 in different racial/ethnic groups with different languages. Furthermore, a future multi-institutional study of the pFS-ICU 24 with a larger sample size will support greater universal validity and reliability as an assessment tool of satisfaction with care and medical decision-making for parents/caregivers of critically ill children. Nevertheless, our initial assessment suggests that the pFS-ICU 24 is a promising tool to use as the first step in translating parent/caregiver satisfaction into quality improvement for critically ill children and their families.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/pccmjournal).

The authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine (U.S.): Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, et al. : Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care: A systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med 2011; 9:155–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laschinger HS, Hall LM, Pedersen C, et al. : A psychometric analysis of the patient satisfaction with nursing care quality questionnaire: An actionable approach to measuring patient satisfaction. J Nurs Care Qual 2005; 20:220–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. : Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ 2001; 323:908–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mallinger JB, Griggs JJ, Shields CG: Patient-centered care and breast cancer survivors’ satisfaction with information. Patient Educ Couns 2005; 57:342–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. : The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract 2000; 49:796–804 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latour JM, Hazelzet JA, van der Heijden AJ: Parent satisfaction in pediatric intensive care: A critical appraisal of the literature. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005; 6:578–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vos M, Graafmans W, Keesman E, et al. : Quality measurement at intensive care units: Which indicators should we use? J Crit Care 2007; 22:267–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schull MJ, Guttmann A, Leaver CA, et al. : Prioritizing performance measurement for emergency department care: Consensus on evidence-based quality of care indicators. CJEM 2011; 13:300–309, E28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berenholtz SM, Dorman T, Ngo K, et al. : Qualitative review of intensive care unit quality indicators. J Crit Care 2002; 17:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chassin MR, Galvin RW: The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA 1998; 280:1000–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flaatten H: The present use of quality indicators in the intensive care unit. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012; 56:1078–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson D, Wilson M, Cavanaugh B, et al. : Measuring the ability to meet family needs in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1998; 26:266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. : Refinement, scoring, and validation of the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) survey. Crit Care Med 2007; 35:271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wasser T, Pasquale MA, Matchett SC, et al. : Establishing reliability and validity of the critical care family satisfaction survey. Crit Care Med 2001; 29:192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell-Dicenso A, Guyatt G, Paes B, et al. : A new measure of parent satisfaction with medical care provided in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Epidemiol 1996; 49:313–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McPherson ML, Sachdeva RC, Jefferson LS: Development of a survey to measure parent satisfaction in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2000; 28:3009–3013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latour JM, van Goudoever JB, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. : Construction and psychometric testing of the EMPATHIC questionnaire measuring parent satisfaction in the pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 2011; 37:310–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haines C, Childs H: Parental satisfaction with paediatric intensive care. Paediatr Nurs 2005; 17:37–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. : Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med 2007; 35(2):605–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, et al. : Decision-making in the ICU: Perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Med 2003; 29:75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrand E, Bachoud-Levi AC, Rodrigues M, et al. : Decision-making capacity and surrogate designation in French ICU patients. Intensive Care Med 2001; 27:1360–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen LM, McCue JD, Green GM: Do clinical and formal assessments of the capacity of patients in the intensive care unit to make decisions agree? Arch Intern Med 1993; 153:2481–2485 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanson LC, Danis M, Mutran E, et al. : Impact of patient incompetence on decisions to use or withhold life-sustaining treatment. Am J Med 1994; 97:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prendergast TJ, Claessens MT, Luce JM: A national survey of end-of-life care for critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 158:1163–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heyland DK, Tranmer JE; Kingston General Hospital ICU Research Working Group: Measuring family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: The development of a questionnaire and preliminary results. J Crit Care 2001; 16:142–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, et al. : Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: Results of a multiple center study. Crit Care Med 2002; 30:1413–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) Survey. Available at: http://www.thecarenet.ca/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=135&Itemid=91. Accessed January 14, 2013

- 29.Pediatric ICU Family Satisfaction Survey (pFS-ICU 24). Available at: http://www.thecarenet.ca/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=137&Itemid=92. Accessed January 14, 2013

- 30.Dodek PM, Heyland DK, Rocker GM, et al. : Translating family satisfaction data into quality improvement. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:1922–1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henrich NJ, Dodek P, Heyland D, et al. : Qualitative analysis of an intensive care unit family satisfaction survey. Crit Care Med 2011; 39:1000–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penticuff JH, Arheart KL: Effectiveness of an intervention to improve parent-professional collaboration in neonatal intensive care. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2005; 19:187–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langley GJ, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, et al. : The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burroughs TE, Cira JC, Chartock P, et al. : Using root cause analysis to address patient satisfaction and other improvement opportunities. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 2000; 26:439–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dyck D: Gap analysis of health services. Client satisfaction surveys. AAOHN J 1996; 44:541–549 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaplin E, Bailey M, Crosby R, et al. : Using quality function deployment to capture the voice of the customer and translate it into the voice of the provider. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 1999; 25: 300–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson P: Master the steps to performance improvement: Plan, do, study, and act to enhance your facility’s patient care initiatives. Nurs Manage 2004; 35:45–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S, et al. : Patients’ experiences and satisfaction with health care: Results of a questionnaire study of specific aspects of care. Qual Saf Health Care 2002; 11:335–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodek PM, Wong H, Heyland DK, et al. ; Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET): The relationship between organizational culture and family satisfaction in critical care. Crit Care Med 2012; 40:1506–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carey RG, Lloyd RC: Measuring Quality Improvement in Healthcare: A Guide to Statistical Process Control Applications. Milwaukee, Quality Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Tiel FH, Elenbaas TW, Voskuilen BM, et al. : Plan-do-study-act cycles as an instrument for improvement of compliance with infection control measures in care of patients after cardiothoracic surgery. J Hosp Infect 2006; 62:64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.