Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of dementia as well as Alzheimer disease in observational studies. Whether this association reflects causal association is still unclear. The purpose of this study was to examine the causal association of AF with Alzheimer disease.

Methods and Results

We used a 2‐sample Mendelian randomization approach to evaluate the causal effect of AF on Alzheimer disease. Summary data on the association of single nucleotide polymorphisms with AF were obtained from a recently published genome‐wide association study with up to 1 030 836 individuals and data on single nucleotide polymorphism‐Alzheimer disease association from another genome‐wide association study with up to 455 258 individuals. AF was mainly diagnosed according to International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9 or ICD‐10) and Alzheimer disease was mainly diagnosed according to clinical criteria (eg, National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association [NINCDS‐ADRDA] criteria). Effect estimates were calculated using the inverse‐variance weighted method. The Mendelian randomization analysis showed nonsignificant association of genetically predicted AF with risk of Alzheimer disease (odds ratio=1.002, 95% CI: 0.996–1.009, P=0.47) using 93 single nucleotide polymorphisms as the instruments. Mendelian randomization‐Egger indicated no evidence of genetic pleiotropy (intercept=0.0002, 95% CI: −0.001 to 0.001, P=0.70).

Conclusions

This Mendelian randomization analysis found no evidence to support causal association between AF and Alzheimer disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, atrial fibrillation, causal association, genetics, Mendelian randomization

Subject Categories: Atrial Fibrillation

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

The relationship between atrial fibrillation and degenerative dementia such as Alzheimer disease is still unclear.

The causal association of atrial fibrillation with Alzheimer disease was examined using a 2‐sample Mendelian randomization analysis using summary data from recently published genome‐wide association studies.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

This study did not provide convincing evidence to support a causal association between atrial fibrillation and Alzheimer disease.

Dementia is a major cause of disability in elderly people without available curative treatment.1 Worldwide, there were ≈50 million people living with dementia in 2018, and this number is expected to increase because of population growth and aging.2 Although the pathophysiologic mechanism of dementia is largely unknown, there has been increasing evidence that vascular risk factors and vascular diseases may contribute to cognitive decline and dementia.3

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia in the elderly population. AF was associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, which may further cause cognitive decline and dementia.4 It was well established that AF may increase vascular dementia5; however, the relationship between AF and degenerative dementia such as Alzheimer disease was still controversial. There were growing evidences indicating that the presence of AF might increase the risk of cognitive decline and dementia even in patients without prior stroke.6 Recently, several longitudinal studies have suggested that AF not only contributed to vascular dementia, but also to Alzheimer disease.5, 6 However, observational studies might be confounded by potential biases and reverse causation.7 Whether the association between AF and Alzheimer disease observed in observational studies reflects causal association required further investigation.

Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis can avoid potential unmeasured confounders and reverse causation by using genetic variants as instrumental variables and make stronger causal inferences between an exposure and risk of disease.7 In this study, we aimed to use MR analysis to evaluate the causal association of AF with Alzheimer disease using MR analysis.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

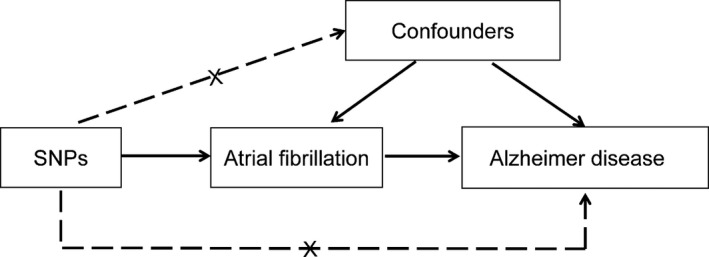

We designed a 2‐sample MR approach to evaluate the causal effect of AF on Alzheimer disease (Figure 1). The MR design is under the assumption that the genetic variants are associated with AF, but independent of confounders and risk of Alzheimer disease conditional on AF and confounders. Based on this design, MR analysis can control potential confounders and reverse causation and make stronger causal inferences.7 Data on the association of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with AF and the association of SNPs with Alzheimer disease were obtained from recently published genome‐wide association studies (GWAS).8, 9 The protocol and data collection of the original studies were approved by the ethics committee of participating sites and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for the Mendelian randomization analysis of atrial fibrillation and risk of Alzheimer disease. The design is under the assumption that the genetic variants are associated with atrial fibrillation, but not with confounders, and the genetic variants are not associated with risk of Alzheimer disease conditional on atrial fibrillation and confounders. SNP indicates single nucleotide polymorphism.

Selection of Genetic Variants

We used previous published genetic variants associated with AF from a recent published GWAS. That study tested association between 34 740 186 genetic variants and AF with a total of 60 620 cases and 970 216 controls from 6 contributing studies. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the contributing studies of the GWAS. The majority (98.6%) of individuals were of European ancestry. AF was mainly diagnosed according to International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9 or ICD‐10). In that study, 111 genetic loci with at least 1 genetic variant associated with AF were identified (P<5.0×10−8). These locus index variants explained 4.6% of the variation in AF (F statistic=534, indicating sufficient strength of the instruments).8 All these 111 SNPs were in different genomic regions and not in linkage disequilibrium (r 2<0.10).8 We performed a look‐up of the 111 SNPs in Phenoscanner (a curated database holding publicly available results from large‐scale GWAS with >65 billion associations and >150 million unique genetic variants; accessed on October 27, 2019) to evaluate whether these SNPs were associated with other traits at genome‐wide significance level (P<5.0×10−8) that may affect our results.10 We found that 9 SNPs (rs284277, rs1458038, rs60212594, rs422068, rs2540949, rs9899183, rs35005436, rs10006327, and rs12245149) were also associated with systolic blood pressure or self‐reported hypertension and 7 SNPs (rs7789146, rs2885697, rs9953366, rs4951258, rs12604076, rs56201652, and rs34080181) were also associated with whole body water mass, fat‐free mass, or fat percentage. After exclusion of these 16 SNPs and 2 SNPs (rs12648245 and rs11156751) not found in outcome data sets, we used the remaining 93 SNPs as the instrument in the MR analysis. Table 2 shows the characteristics and associations of the 93 included SNPs with AF.

Table 1.

Description of Contributing Studies

| Contributing Studies | Sample Size (Cases/Controls) | Ancestry | Diagnosis of Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS for atrial fibrillation | 60 620/970 216 | ||

| The Nord‐Trøndelag Health Study | 6493/63 142 | European | ICD‐10 code I48 or ICD‐9 code 427.3 |

| deCODE | 13 471/358 161 | European | ICD‐10 code I48 or ICD‐9 code 427.3 |

| Michigan Genomics Initiative | 1226/11 049 | European | ICD‐9 code 427.31 |

| DiscovEHR Collaboration Cohort | 6679/41 803 | European | At least 1 electronic health record problem list entry or at least 2 diagnosis code entries for 2 separate clinical encounters on separate calendar days for ICD‐10 I48 |

| UK Biobank | 14 820/380 919 | European | ICD‐9 427.3 or ICD‐10 I48 |

| AFGen Consortium | 15 979/102 776 | European | Diagnosed according to ICD‐9, ICD‐10, or 12‐lead ECG at the examinations |

| 641/5234 | Black | ||

| 837/3293 | Japanese | ||

| 277/3081 | Hispanic | ||

| 197/758 | Brazilian | ||

| GWAS for Alzheimer disease | 71 880/383 378 | ||

| Alzheimer's disease working group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium [PGC‐ALZ] | 2965/14 512 | European | According to the recommendations from the NIA/AA, NINCDS‐ADRDA criteria or the ICD‐10 research criteria |

| International Genomics of Alzheimer's Project [IGAP] | 17 008/37 154 | European | Autopsy‐ or clinically confirmed Alzheimer Disease cases with NINCDS‐ADRDA criteria, DSM‐IV criteria, the ADDTC's State of California criteria or DSM‐III‐R criteria |

| Alzheimer's Disease Sequencing Project [ADSP] | 4114/3392 | European | |

| UK Biobank | 47 793/328 320 | European | Self‐report questionnaire administered during the in‐person assessment and confirmed with ICD‐10 codes (G30, F00) in national medical records |

ADDTC indicates Alzheimer's Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers; DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐Third Edition, Revised; DSM‐IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition; GWAS, genome‐wide association studies; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; NIA/AA, National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association; NINCDS‐ADRDA, National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 93 SNPs Associated With Atrial Fibrillation

| SNP | Prioritized Genes | Position (hg19) | EA/OA | EAF | Effect on Atrial Fibrillation | Effect on AD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | P Value | Beta | SE | P Value | |||||

| rs7529220 | HSPG2 | chr1:22282619 | C/T | 0.847 | 0.0621 | 0.0098 | 1.98×10−10 | 0.0094 | 0.0029 | 0.001 |

| rs11590635 | AGBL4 | chr1:49309764 | A/G | 0.024 | 0.1456 | 0.0248 | 4.12×10−9 | −0.0040 | 0.0079 | 0.616 |

| rs146518726 | MIR6500 | chr1:51535039 | A/G | 0.033 | 0.1605 | 0.0207 | 8.27×10−15 | −0.0019 | 0.0072 | 0.795 |

| rs1545300 | KCND3 | chr1:112464004 | C/T | 0.691 | 0.0558 | 0.0073 | 1.48×10−14 | 0.0059 | 0.0024 | 0.013 |

| rs4073778 | CASQ2 | chr1:116297758 | A/C | 0.564 | 0.0486 | 0.0067 | 4.96×10−13 | 0.0028 | 0.0021 | 0.189 |

| rs79187193 | GJA5 | chr1:147255831 | G/A | 0.943 | 0.1162 | 0.0153 | 3.15×10−14 | −0.0049 | 0.0054 | 0.363 |

| rs11264280 | KCNN3 | chr1:154862952 | T/C | 0.333 | 0.1347 | 0.0071 | 3.07×10−79 | 0.0000 | 0.0023 | 0.983 |

| rs72700114 | LINC01142 | chr1:170193825 | C/G | 0.076 | 0.2021 | 0.013 | 3.29×10−54 | 0.0006 | 0.0043 | 0.896 |

| rs10753933 | PPFIA4 | chr1:203026214 | T/G | 0.448 | 0.0609 | 0.0067 | 9.84×10−20 | −0.0019 | 0.0021 | 0.381 |

| rs7578393 | KIF3C | chr2:26165528 | T/C | 0.796 | 0.0614 | 0.0088 | 2.42×10−12 | −0.0051 | 0.0062 | 0.405 |

| rs11125871 | USP34 | chr2:61470126 | C/T | 0.605 | 0.0394 | 0.0068 | 6.42×10−9 | 0.0003 | 0.0022 | 0.906 |

| rs6747542 | GMCL1,ANXA4 | chr2:70106832 | T/C | 0.536 | 0.0554 | 0.0067 | 1.10×10−16 | −0.0006 | 0.0021 | 0.768 |

| rs72926475 | REEP1 | chr2:86594487 | G/A | 0.877 | 0.0683 | 0.0102 | 2.37×10−11 | −0.0018 | 0.0032 | 0.575 |

| rs28387148 | GYPC | chr2:127433465 | T/C | 0.105 | 0.0741 | 0.0113 | 6.25×10−11 | −0.0051 | 0.0035 | 0.152 |

| rs67969609 | TEX41 | chr2:145760353 | G/C | 0.071 | 0.0711 | 0.0126 | 1.71×10−8 | −0.0002 | 0.0037 | 0.951 |

| rs56181519 | WIPF1 | chr2:175555714 | C/T | 0.732 | 0.0662 | 0.0077 | 6.46×10−18 | −0.0021 | 0.0024 | 0.371 |

| rs2288327 | TTN,MIR548N,FKBP7,TTN‐AS1 | chr2:179411665 | G/A | 0.156 | 0.0919 | 0.0089 | 7.26×10−25 | 0.0004 | 0.0028 | 0.891 |

| rs3820888 | SPATS2L | chr2:201180023 | C/T | 0.392 | 0.0684 | 0.0068 | 5.75×10−24 | −0.0005 | 0.0022 | 0.813 |

| rs35544454 | ERBB4 | chr2:213266003 | A/T | 0.808 | 0.0589 | 0.0087 | 1.10×10−11 | 0.0050 | 0.0028 | 0.071 |

| rs7650482 | CAND2 | chr3:12841804 | G/A | 0.640 | 0.0711 | 0.007 | 1.79×10−24 | 0.0030 | 0.0022 | 0.169 |

| rs73041705 | THRB | chr3:24463235 | T/C | 0.702 | 0.0443 | 0.0073 | 1.55×10−9 | −0.0016 | 0.0023 | 0.496 |

| rs6790396 | SCN10A,SCN5A | chr3:38771925 | G/C | 0.596 | 0.0627 | 0.0068 | 2.40×10−20 | −0.0012 | 0.0021 | 0.567 |

| rs17005647 | FRMD4B | chr3:69406181 | T/C | 0.364 | 0.0413 | 0.0069 | 2.70×10−9 | 0.0026 | 0.0022 | 0.252 |

| rs6771054 | EPHA3 | chr3:89489529 | T/C | 0.596 | 0.0457 | 0.0068 | 2.42×10−11 | 0.0002 | 0.0022 | 0.925 |

| rs10804493 | PHLDB2,PLCXD2 | chr3:111554426 | A/G | 0.651 | 0.0558 | 0.007 | 1.63×10−15 | −0.0003 | 0.0022 | 0.877 |

| rs1278493 | PPP2R3A | chr3:135814009 | G/A | 0.436 | 0.0389 | 0.0068 | 8.77×10−9 | 0.0034 | 0.0021 | 0.105 |

| rs7612445 | GNB4 | chr3:179172979 | T/G | 0.188 | 0.0493 | 0.0084 | 4.81×10−9 | 0.0023 | 0.0026 | 0.372 |

| rs60902112 | XXYLT1 | chr3:194800853 | T/C | 0.226 | 0.0445 | 0.0079 | 1.72×10−8 | 0.0001 | 0.0025 | 0.967 |

| rs67249485 | PITX2 | chr4:111699685 | T/A | 0.199 | 0.3655 | 0.0081 | 7.32×10−443 | 0.0029 | 0.0025 | 0.250 |

| rs6829664 | CAMK2D | chr4:114448656 | G/A | 0.262 | 0.0556 | 0.0076 | 1.92×10−13 | −0.0030 | 0.0025 | 0.217 |

| rs10213171 | ARHGAP10 | chr4:148937537 | G/C | 0.061 | 0.091 | 0.0134 | 1.32×10−11 | −0.0021 | 0.0041 | 0.605 |

| rs6596717 | LOC102467213 | chr5:106427609 | C/A | 0.395 | 0.0404 | 0.0068 | 3.00×10−9 | −0.0011 | 0.0022 | 0.617 |

| rs337705 | KCNN2 | chr5:113737062 | G/T | 0.375 | 0.0564 | 0.0068 | 1.63×10−16 | 0.0012 | 0.0021 | 0.592 |

| rs2012809 | SLC27A6 | chr5:128190363 | G/A | 0.790 | 0.0582 | 0.0094 | 4.92×10−10 | 0.0029 | 0.0028 | 0.290 |

| rs2040862 | WNT8A,NPY6R,MYOT,FAM13B | chr5:137419989 | T/C | 0.178 | 0.1084 | 0.0087 | 1.08×10−35 | 0.0023 | 0.0028 | 0.420 |

| rs6580277 | NR3C1 | chr5:142818123 | G/A | 0.237 | 0.067 | 0.0079 | 1.64×10−17 | 0.0019 | 0.0025 | 0.456 |

| rs12188351 | SLIT3 | chr5:168386089 | A/G | 0.056 | 0.0865 | 0.0145 | 2.52×10−9 | −0.0012 | 0.0048 | 0.807 |

| rs6891790 | NKX2‐5 | chr5:172670745 | G/T | 0.717 | 0.0729 | 0.0076 | 4.53×10−22 | −0.0025 | 0.0023 | 0.278 |

| rs73366713 | ATXN1 | chr6:16415751 | G/A | 0.860 | 0.1035 | 0.0099 | 1.53×10−25 | 0.0012 | 0.0031 | 0.700 |

| rs34969716 | KDM1B,DEK | chr6:18210109 | A/G | 0.305 | 0.0702 | 0.0078 | 1.60×10−19 | −0.0015 | 0.0058 | 0.791 |

| rs3176326 | CDKN1A,PANDAR,PI16 | chr6:36647289 | G/A | 0.802 | 0.0626 | 0.0085 | 1.42×10−13 | 0.0001 | 0.0026 | 0.958 |

| rs2031522 | CGA | chr6:87821501 | A/G | 0.624 | 0.0436 | 0.0068 | 1.47×10−10 | −0.0009 | 0.0022 | 0.677 |

| rs3951016 | SLC35F1,PLN | chr6:118559658 | A/T | 0.459 | 0.0648 | 0.0067 | 2.15×10−22 | −0.0021 | 0.0021 | 0.328 |

| rs13195459 | HSF2 | chr6:122403559 | G/A | 0.638 | 0.0623 | 0.007 | 4.15×10−19 | −0.0018 | 0.0022 | 0.402 |

| rs117984853 | UST | chr6:149399100 | T/G | 0.101 | 0.1228 | 0.012 | 1.34×10−24 | −0.0036 | 0.0039 | 0.357 |

| rs55734480 | DGKB | chr7:14372009 | A/G | 0.249 | 0.0548 | 0.0078 | 2.20×10−12 | −0.0034 | 0.0024 | 0.155 |

| rs6462079 | CREB5 | chr7:28415827 | A/G | 0.721 | 0.0466 | 0.0076 | 8.79×10−10 | 0.0065 | 0.0025 | 0.009 |

| rs11773845 | CAV1,CAV2 | chr7:116191301 | A/C | 0.586 | 0.1054 | 0.0067 | 2.39×10−55 | −0.0022 | 0.0021 | 0.295 |

| rs55985730 | OPN1SW,CALU | chr7:128417044 | G/T | 0.060 | 0.0867 | 0.0149 | 5.24×10−9 | 0.0006 | 0.0049 | 0.907 |

| rs35620480 | GATA4 | chr8:11499908 | C/A | 0.157 | 0.054 | 0.0092 | 5.15×10−9 | 0.0046 | 0.0029 | 0.107 |

| rs7508 | ASAH1 | chr8:17913970 | A/G | 0.711 | 0.0711 | 0.0075 | 1.69×10−21 | −0.0025 | 0.0024 | 0.292 |

| rs7834729 | XPO7 | chr8:21821778 | G/T | 0.885 | 0.0653 | 0.0104 | 3.55×10−10 | 0.0047 | 0.0031 | 0.131 |

| rs62521286 | FBXO32 | chr8:124551975 | G/A | 0.066 | 0.1202 | 0.0135 | 4.50×10−19 | −0.0004 | 0.0045 | 0.936 |

| rs6994744 | PTK2 | chr8:141740868 | C/A | 0.495 | 0.0405 | 0.0066 | 1.10×10−9 | −0.0026 | 0.0021 | 0.212 |

| rs10821415 | C9orf3 | chr9:97713459 | A/C | 0.413 | 0.0821 | 0.0067 | 2.92×10−34 | −0.0012 | 0.0021 | 0.574 |

| rs2274115 | LHX3 | chr9:139094773 | G/A | 0.700 | 0.0487 | 0.0076 | 1.69×10−10 | 0.0047 | 0.0023 | 0.042 |

| rs7096385 | SIRT1,MYPN | chr10:69664881 | T/C | 0.092 | 0.0707 | 0.013 | 4.87×10−8 | −0.0006 | 0.0039 | 0.868 |

| rs10458660 | C10orf11 | chr10:77936576 | G/A | 0.173 | 0.0537 | 0.0087 | 6.78×10−10 | 0.0002 | 0.0028 | 0.932 |

| rs11598047 | NEURL1 | chr10:105342672 | G/A | 0.162 | 0.1537 | 0.009 | 8.95×10−66 | −0.0018 | 0.0028 | 0.514 |

| rs10749053 | RBM20 | chr10:112576695 | T/C | 0.158 | 0.0555 | 0.0097 | 1.05×10−8 | −0.0065 | 0.0029 | 0.027 |

| rs10741807 | NAV2 | chr11:20011445 | T/C | 0.245 | 0.0729 | 0.0079 | 1.59×10−20 | −0.0075 | 0.0025 | 0.003 |

| rs4935786 | SORL1 | chr11:121661507 | T/A | 0.267 | 0.0463 | 0.0079 | 4.85×10−9 | −0.0035 | 0.0058 | 0.551 |

| rs76097649 | KCNJ5 | chr11:128764570 | A/G | 0.093 | 0.1151 | 0.0124 | 1.26×10−20 | 0.0038 | 0.0038 | 0.321 |

| rs4963776 | LINC00477 | chr12:24779491 | G/T | 0.818 | 0.0913 | 0.0088 | 1.84×10−25 | −0.0016 | 0.0028 | 0.567 |

| rs17380837 | SSPN | chr12:26345526 | C/T | 0.693 | 0.0501 | 0.0072 | 4.80×10−12 | −0.0002 | 0.0023 | 0.927 |

| rs12809354 | PKP2 | chr12:32978437 | C/T | 0.144 | 0.0718 | 0.0094 | 2.89×10−14 | 0.0012 | 0.0029 | 0.667 |

| rs2860482 | NACA | chr12:57105938 | A/C | 0.274 | 0.054 | 0.0076 | 1.21×10−12 | 0.0005 | 0.0024 | 0.835 |

| rs71454237 | LRRC10 | chr12:70013415 | G/A | 0.791 | 0.062 | 0.0084 | 1.78×10−13 | 0.0028 | 0.0026 | 0.293 |

| rs12426679 | PHLDA1 | chr12:76237987 | C/T | 0.472 | 0.0391 | 0.0067 | 4.95×10−9 | 0.0017 | 0.0021 | 0.416 |

| rs883079 | TBX5 | chr12:114793240 | T/C | 0.707 | 0.0981 | 0.0074 | 2.84×10−40 | −0.0006 | 0.0023 | 0.782 |

| rs10773657 | HIP1R | chr12:123327900 | C/A | 0.138 | 0.0575 | 0.0103 | 2.54×10−8 | −0.0099 | 0.0031 | 0.002 |

| rs6560886 | FBRSL1 | chr12:133150210 | C/T | 0.788 | 0.051 | 0.009 | 1.49×10−8 | −0.0060 | 0.0069 | 0.383 |

| rs9506925 | LINC00540,LINC00621,SGCG | chr13:23368943 | T/C | 0.267 | 0.0449 | 0.0075 | 2.72×10−9 | 0.0002 | 0.0024 | 0.937 |

| rs35569628 | CUL4A | chr13:113872712 | T/C | 0.777 | 0.0452 | 0.008 | 1.38×10−8 | 0.0039 | 0.0025 | 0.117 |

| rs73241997 | CFL2 | chr14:35173775 | T/C | 0.142 | 0.0733 | 0.0093 | 2.94×10−15 | 0.0018 | 0.0029 | 0.540 |

| rs2738413 | SYNE2,MIR548AZ,ESR2,MTHFD1 | chr14:64679960 | A/G | 0.495 | 0.0778 | 0.0067 | 2.55×10−31 | 0.0003 | 0.0021 | 0.895 |

| rs74884082 | DPF3 | chr14:73249419 | C/T | 0.750 | 0.0493 | 0.0078 | 3.48×10−10 | 0.0012 | 0.0025 | 0.632 |

| rs10873298 | IRF2BPL | chr14:77426525 | C/T | 0.366 | 0.0401 | 0.0069 | 7.07×10−9 | 0.0004 | 0.0021 | 0.868 |

| rs147301839 | GCOM1/MYZAP | chr15:57924714 | C/A | 0.007 | 0.3328 | 0.0523 | 1.93×10−10 | 0.0100 | 0.0173 | 0.565 |

| rs7170477 | HERC1 | chr15:64103777 | A/G | 0.304 | 0.0393 | 0.0072 | 4.98×10−8 | 0.0037 | 0.0023 | 0.108 |

| rs74022964 | HCN4 | chr15:73677264 | T/C | 0.157 | 0.1132 | 0.009 | 3.51×10−36 | 0.0008 | 0.0029 | 0.786 |

| rs12908004 | ARNT2 | chr15:80676925 | G/A | 0.164 | 0.0732 | 0.009 | 4.12×10−16 | 0.0007 | 0.0028 | 0.795 |

| rs4965430 | IGF1R | chr15:99268850 | C/G | 0.386 | 0.0441 | 0.0069 | 1.26×10−10 | 0.0019 | 0.0022 | 0.370 |

| rs140185678 | RPL3L | chr16:2003016 | A/G | 0.035 | 0.1659 | 0.0218 | 2.43×10−14 | −0.0113 | 0.0068 | 0.097 |

| rs2359171 | ZFHX3 | chr16:73053022 | A/T | 0.176 | 0.1746 | 0.0086 | 4.65×10−91 | 0.0045 | 0.0028 | 0.101 |

| rs7225165 | YWHAE,CRK,MYO1C | chr17:1309850 | G/A | 0.887 | 0.0655 | 0.0111 | 3.20×10−9 | 0.0020 | 0.0033 | 0.547 |

| rs72811294 | MYOCD | chr17:12618680 | G/C | 0.887 | 0.072 | 0.0106 | 9.67×10−12 | −0.0010 | 0.0033 | 0.772 |

| rs11658278 | ZPBP2,GSDMB,ORMDL3 | chr17:38031164 | T/C | 0.479 | 0.0443 | 0.0067 | 3.47×10−11 | −0.0036 | 0.0021 | 0.089 |

| rs1563304 | WNT3 | chr17:44874453 | T/C | 0.178 | 0.0644 | 0.0092 | 2.56×10−12 | 0.0001 | 0.0029 | 0.979 |

| rs8088085 | MEX3C | chr18:48708548 | A/C | 0.535 | 0.0365 | 0.0067 | 4.79×10−8 | 0.0012 | 0.0021 | 0.584 |

| rs2834618 | LINC01426 | chr21:36119111 | T/G | 0.894 | 0.0944 | 0.0112 | 3.41×10−17 | −0.0024 | 0.0034 | 0.469 |

| rs464901 | TUBA8 | chr22:18597502 | T/C | 0.665 | 0.0508 | 0.0072 | 1.53×10−12 | −0.0007 | 0.0022 | 0.761 |

| rs133902 | MYO18B | chr22:26164079 | T/C | 0.427 | 0.0419 | 0.0068 | 9.14×10−10 | 0.0028 | 0.0021 | 0.194 |

AD indicates Alzheimer disease; EA, effect allele; EAF, effect allele frequency; OA, other allele; SE, standard error; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Outcomes

Summary statistics for the associations between the 93 SNPs related to AF and Alzheimer disease were obtained from the recently published genome‐wide meta‐analysis.9 In that study, genome‐wide meta‐analysis was performed through 3 phases including 71 880 Alzheimer disease cases and 383 378 controls (Table 1). Phase 1 involved a genome‐wide meta‐analysis for clinically diagnosed Alzheimer disease (eg, according to National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association [NINCDS‐ADRDA] criteria) case–control status using data from 3 independent consortia with 79 145 individuals of European ancestry and 9 862 738 genetic variants. Phase 2 involved a GWAS using 376 113 individuals of European ancestry from UK Biobank with parental Alzheimer disease status weighted by age to construct an Alzheimer disease‐by‐proxy status assessed as part of the self‐report questionnaire administered during the in‐person assessment and additional information obtained from medical records. All individuals of phase 1 and phase 2 were meta‐analyzed together in phase 3. The associations between each SNP related to AF and Alzheimer disease are presented in Table 2.

Statistical Analysis

We used 2‐sample MR approaches to compute estimates of the effect of AF on Alzheimer disease using summarized data of the SNP‐AF and SNP‐Alzheimer disease associations. We performed both fixed‐effect and random‐effect inverse‐variance weighted (IVW) MR analysis in which the effect estimate was the IVW mean of ratio estimates from 2 or more instruments using first‐order weights, assuming all SNPs were valid instruments.11 In sensitivity analyses, we also conducted penalized IVW, penalized robust IVW, MR‐Egger, simple median, weighted median, weighted mode‐based estimate (MBE), and Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy Residual Sum and Outlier (MR‐PRESSO) methods of MR analyses. The penalized methods improved the robustness by penalizing the weights of instruments with pleiotropic effect with heterogeneous ratio estimates in the weighted regression model and the robust method can provide robust estimates both to outliers and to data points with high leverage by performing robust regression.12 The MR‐Egger method was performed by weighted linear regression of the associations of SNP with Alzheimer disease on the associations of SNP with AF using the inverse‐variance of SNP‐Alzheimer disease estimate as weights. The MR‐Egger method may provide robust estimates to potential violations of the standard instrumental variable assumptions because of directional pleiotropy (a genetic variant affects the Alzheimer disease via a different biological pathway from AF).13 The weighted median method may provide robust estimates against invalid instruments (even if up to 50% of genetic variants are invalid instruments) using the inverse of the variance of the ratio estimates as weights.14 The weighted MBE method used the mode of the IVW empirical density function as the weighted MBEs and obtained a causal effect estimate robust to horizontal pleiotropy.15 The MR‐PRESSO approach was used to detect and correct for horizontal pleiotropic outliers through outlier removal in multi‐instrument summary‐level MR testing.16 These methods had been demonstrated to be more robust to the inclusion of pleiotropic and/or invalid instruments and provide a consistent estimate of the causal effect. The second‐order weights were used in the weighted MBE method and first‐order weights were used for all other methods. Heterogeneity between SNPs in the IVW analysis was estimated by Q statistic and I2 index.14 Potential pleiotropic effects were estimated by intercepts of the MR‐Egger regression.13 An statistic was calculated to test the presence of bias with MR‐Egger because of measurement error; statistic >0.90 was considered no obvious violation of “NO Measurement Error” assumption and sufficient for instruments in the MR‐Egger analyses.17 We also performed a leave‐1‐out analysis in which 1 SNP was excluded in turn to estimate the influence of outlying and/or pleiotropic SNPs.18

The associations between genetically predicted AF and Alzheimer disease were presented as odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% CIs per 1‐unit‐higher log‐odds of AF. The association of each genetic variant with AF was further plotted against its effect for the risk of Alzheimer disease.

A power analysis using a web‐based application (http://cnsgenomics.com/shiny/mRnd/) was conducted to estimate the minimum detectable magnitude of association in terms of OR per log odds of AF. Based on the sample size of 1 030 836, our MR analysis has 80% power at an alpha rate of 5% to detect an OR of 1.055 per log odds of AF.

An observed 2‐sided P<0.05 was considered as significant evidence for a causal association. All analyses were conducted with R 3.5.3 (R Development Core Team).

Results

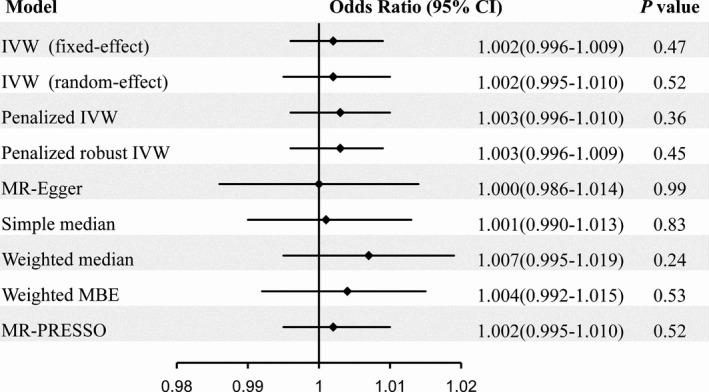

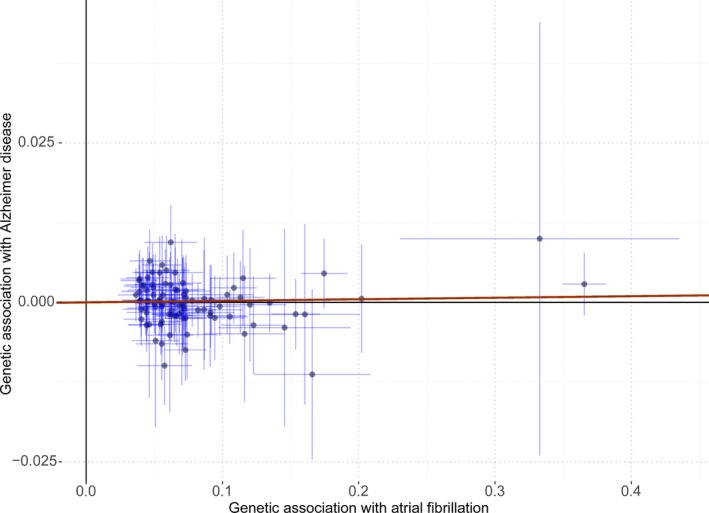

The MR analysis showed nonsignificant association of genetically predicted AF with risk of Alzheimer disease using 93 SNPs as the instruments (Figure 2). The fixed‐effect and random‐effect IVW methods showed that genetically predicted AF was not associated with the risk of Alzheimer disease (OR=1.002, 95% CI: 0.996–1.009, P=0.47; OR=1.002, 95% CI: 0.995–1.010, P=0.52). Similar results were observed using the penalized IVW, penalized robust IVW, MR‐Egger, simple median, weighted median, weighted MBE, and MR‐PRESSO methods. Association between each variant with AF and risk of Alzheimer disease are displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Risk of Alzheimer disease for genetically predicted atrial fibrillation. IVW indicates inverse‐variance weighted; MBE, mode‐based estimate; MR, Mendelian randomization; MR‐PRESSO, Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier.

Figure 3.

Associations of atrial fibrillation–related variants with risk of Alzheimer disease. The red line indicates the estimate of effect using inverse‐variance weighted method. Circles indicate marginal genetic associations with atrial fibrillation and risk of Alzheimer disease for each variant. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

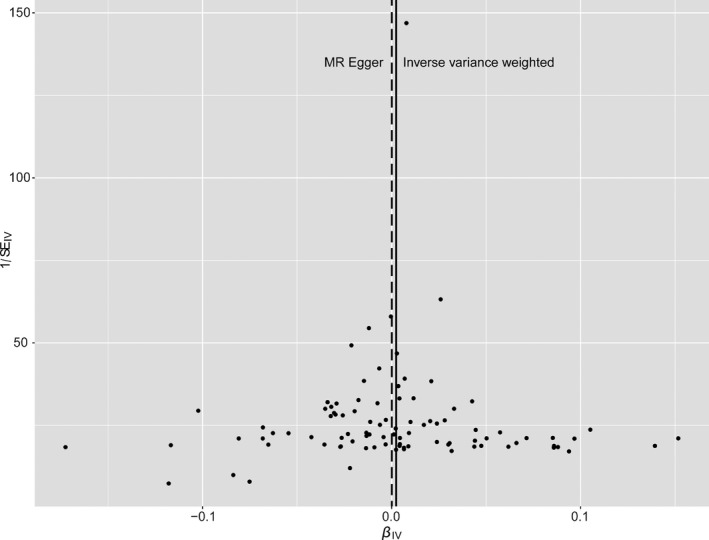

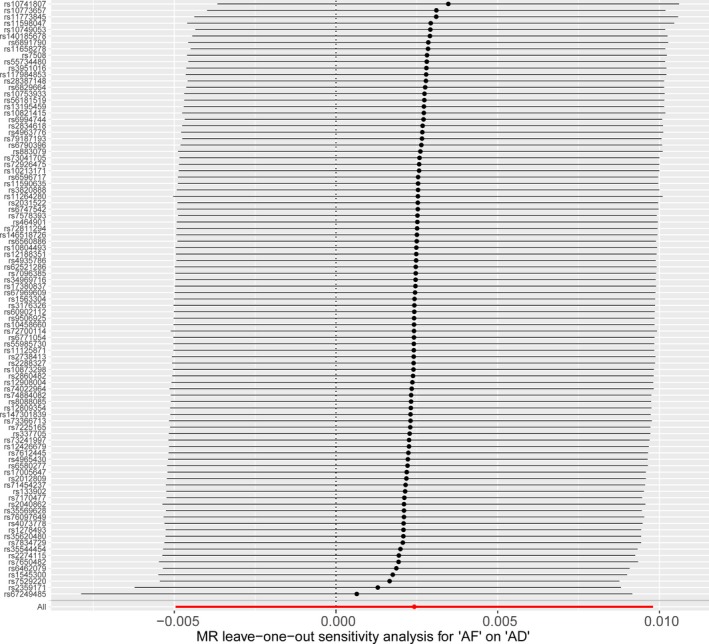

There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the IVW analysis (Q=113.60, P=0.055; I2=19%). MR‐Egger regression showed no evidence of directional pleiotropy for the association of the included SNPs with risk of Alzheimer disease (intercept=0.0002, 95% CI: −0.001 to 0.001, P=0.70). There was a low risk of bias with MR‐Egger because of measurement error ( statistic=96.6%). Funnel plot also showed no evidence of obvious heterogeneity across the estimates, indicating absence of the potential pleiotropic effects (Figure 4). The results of leave‐1‐out sensitivity analysis showed that the negative association between AF and Alzheimer disease was not substantially driven by any individual SNP (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of the Mendelian randomization analysis for Alzheimer disease. Funnel plot evaluated the presence of possible heterogeneity across the estimates, which indicates the potential pleiotropic effects. The figure presents the observed causal effect of each of the 93 instrumental variables (IVs) by dots, and the averaged causal effect of all IVs combined (βIV) using inverse variance weighted (solid line) and MR‐Egger (dashed line) method on x‐axis. Y axis presents the inverse standard error of the estimated causal effect for each of the single nucleotide polymorphisms (IVs).

Figure 5.

MR leave‐1‐out sensitivity analysis for atrial fibrillation on AD. Circles indicate MR estimates for atrial fibrillation on Alzheimer disease using inverse‐variance weighted fixed‐effect method if the SNP was omitted. The bars indicate the CI of MR estimates. AD indicates Alzheimer disease; AF, atrial fibrillation; MR, Mendelian randomization.

Discussion

Using 2‐sample MR analysis based on data from large‐scale GWAS studies, our study demonstrated that genetically predicted AF had no causal effect on the risk of Alzheimer disease. The findings were robust in sensitivity analyses with different instruments and statistical models.

AF and dementia are frequent diseases that predominantly affect elderly people. There were several assumed mechanisms that contribute to AF‐related cognitive decline and dementia, including occurrence of AF‐related (clinically overt or silent) strokes, systemic inflammation, and chronic hypoperfusion of the brain.3, 19 Strong evidences from many prospective studies have been established that AF was associated with cognitive impairment, cognitive decline, and dementia.3, 6, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 However, most studies included all‐cause dementia without separate investigation of vascular dementia and Alzheimer disease.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 In the past decades, accumulating observational evidence has demonstrated that AF was also associated with degenerative dementias such as Alzheimer disease.3, 6, 24 In the prospective Intermountain Heart Collaborative Study with 37 025 patients and 5‐year follow‐up, AF was independently associated with all forms of dementia, including Alzheimer disease.24 In the Korea National Health Insurance Service‐Senior cohort with 262 611 participants, incident AF was associated with an increased risk of both Alzheimer and vascular dementia.6 Longitudinal association was observed between prevalent AF and all‐cause dementia, but the association was nonsignificant between either incident or prevalent AF and Alzheimer disease in the Rotterdam Study.25 However, these studies still cannot control the influence of unmeasured confounders because of the nature of observational study. The present study provides evidence supporting a negative causal effect of genetically predicted AF on risk of Alzheimer disease using an MR approach, and this method may control unmeasured confounders and reverse causation.26

Our findings demonstrated that the causal role of AF on Alzheimer disease could be different from that on vascular dementia. The lack of causal association of AF with the risk of Alzheimer disease in our study suggests that the association of AF with Alzheimer disease risk observed in observational cohort studies may be confounded by other risk factors rather than indicate a causal relationship. It was perhaps unsurprising because dementia and AF share numerous common vascular risk factors, such as hypertension, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, lipid disorders, age, obesity, and physical inactivity.3, 27, 28 The co‐occurrence of AF and Alzheimer disease might be explained by the existence of these common factors. Another potential explanation was that AF probably increased the risk of Alzheimer disease only when AF started in middle age and with a longer duration of AF as neuropathology of underlying dementia gradually developed over many years.3 There was only indirect evidence in observational studies that anticoagulation in AF was associated with a preventive effect on cognitive impairment and dementia development.4, 6 However, these studies did not separately analyze the dementia subtypes and may be confounded by other treatments (ie, patients with anticoagulation may also have a high compliance with treatment targeting other risk factors, such as hypertension, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and lipid disorders).

The strength of the study is the design of MR analysis based on AF‐related SNPs and effects of SNP‐Alzheimer disease from large‐scale GWAS studies. Using the 2‐sample MR approach, we were able to investigate the effect of AF based on data with large sample sizes (60 620 AF cases and 970 216 controls; 71 880 Alzheimer disease cases and 383 378 controls). Compared with traditional observational study, MR analysis is less prone to potential unmeasured confounding and also to avoid reverse causation since genetic variation is allocated at conception, and thus can strengthen the evidence for causal inference.11

Our study has several limitations. First, it is difficult to completely avoid the influence of potential horizontal pleiotropy (a genetic variant affects the outcome via a different biological pathway from the exposure), which may lead to biased causal effect estimates.13 However, pleiotropic effect was not observed in MR‐Egger regression or heterogeneity test, and similar results were observed in sensitivity analyses using several other robust models. Second, the findings were limited since data of associations of SNP‐exposure and SNP‐outcome were derived from 2 different populations. Third, estimates of SNP‐AF association were derived from trans‐ancestry studies, which may cause bias because of population admixture. The same genetic variant could exhibit different pleiotropic effects in different populations. However, we note that this might have subtle influences on the effect estimates because the majority of individuals were of European ancestry and merging studies showed the genetic architecture for common diseases was likely similar across ethnic groups.29 Fourth, measurement error may exist as Alzheimer disease‐by‐proxy was used in UK Biobank in phase 2 of GWAS of Alzheimer disease. This measurement error would likely bias results towards the null. However, a strong genetic correlation (0.81) between Alzheimer disease status and Alzheimer disease‐by‐proxy, and substantial concordance in the individual SNP effects were observed in the original study.9 Finally, there were some overlapping samples between the AF and Alzheimer disease GWAS data set (38.4% in the AF GWAS data set and 82.6% in the Alzheimer disease GWAS data set), which could inflate MR estimates.30 However, this would only affect the study by producing a false positive result and our study observed only negative results.

Conclusions

Our 2‐sample MR analysis did not provide convincing evidence to support a causal effect of AF on risk of Alzheimer disease.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971091), Beijing Hospitals Authority Youth Programme (QML20190501), Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (2016YFC0901001, 2016YFC0901002, 2017YFC1310901, 2017YFC1310902, 2017YFC1307905, 2018YFC1311700, and 2018YFC1311706), Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals (SML20150502), Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (D151100002015003), and Guangdong Natural Science Foundation for Major Cultivation Project (2018B030336001).

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014889 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014889.)

References

- 1. Alzheimer's Association . 2016 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alzheimer's Disease International . World Alzheimer Report 2018. The state of the art of dementia research: New frontiers. Available at: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2018. Accessed on May 18, 2019.

- 3. Diener HC, Hart RG, Koudstaal PJ, Lane DA, Lip GYH. Atrial fibrillation and cognitive function: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Madhavan M, Graff‐Radford J, Piccini JP, Gersh BJ. Cognitive dysfunction in atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:744–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dietzel J, Haeusler KG, Endres M. Does atrial fibrillation cause cognitive decline and dementia? Europace. 2018;20:408–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim D, Yang PS, Yu HT, Kim TH, Jang E, Sung JH, Pak HN, Lee MY, Lee MH, Lip GYH, Joung B. Risk of dementia in stroke‐free patients diagnosed with atrial fibrillation: data from a population‐based cohort. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2313–2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27:1133–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nielsen JB, Thorolfsdottir RB, Fritsche LG, Zhou W, Skov MW, Graham SE, Herron TJ, McCarthy S, Schmidt EM, Sveinbjornsson G, Surakka I, Mathis MR, Yamazaki M, Crawford RD, Gabrielsen ME, Skogholt AH, Holmen OL, Lin M, Wolford BN, Dey R, Dalen H, Sulem P, Chung JH, Backman JD, Arnar DO, Thorsteinsdottir U, Baras A, O'Dushlaine C, Holst AG, Wen X, Hornsby W, Dewey FE, Boehnke M, Kheterpal S, Mukherjee B, Lee S, Kang HM, Holm H, Kitzman J, Shavit JA, Jalife J, Brummett CM, Teslovich TM, Carey DJ, Gudbjartsson DF, Stefansson K, Abecasis GR, Hveem K, Willer CJ. Biobank‐driven genomic discovery yields new insight into atrial fibrillation biology. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1234–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jansen IE, Savage JE, Watanabe K, Bryois J, Williams DM, Steinberg S, Sealock J, Karlsson IK, Hägg S, Athanasiu L, Voyle N, Proitsi P, Witoelar A, Stringer S, Aarsland D, Almdahl IS, Andersen F, Bergh S, Bettella F, Bjornsson S, Brækhus A, Bråthen G, de Leeuw C, Desikan RS, Djurovic S, Dumitrescu L, Fladby T, Hohman TJ, Jonsson PV, Kiddle SJ, Rongve A, Saltvedt I, Sando SB, Selbæk G, Shoai M, Skene NG, Snaedal J, Stordal E, Ulstein ID, Wang Y, White LR, Hardy J, Hjerling‐Leffler J, Sullivan PF, van der Flier WM, Dobson R, Davis LK, Stefansson H, Stefansson K, Pedersen NL, Ripke S, Andreassen OA, Posthuma D. Genome‐wide meta‐analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer's disease risk. Nat Genet. 2019;51:404–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Staley JR, Blackshaw J, Kamat MA, Ellis S, Surendran P, Sun BB, Paul DS, Freitag D, Burgess S, Danesh J, Young R, Butterworth AS. PhenoScanner: a database of human genotype‐phenotype associations. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3207–3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burgess S, Bowden J, Dudbridge F, Thompson SG. Robust instrumental variable methods using multiple candidate instruments with application to Mendelian randomization. arXiv. 2016:1606.03729. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hartwig FP, Davey Smith G, Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1985–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bowden J, Del Greco M F, Minelli C, Davey Smith G, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Assessing the suitability of summary data for two‐sample Mendelian randomization analyses using MR‐Egger regression: the role of the I2 statistic. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1961–1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR‐Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:377–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alonso A, Knopman DS, Gottesman RF, Soliman EZ, Shah AJ, O'Neal WT, Norby FL, Mosley TH, Chen LY. Correlates of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in patients with atrial fibrillation: the atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study (ARIC‐NCS) J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006014 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liao JN, Chao TF, Liu CJ, Wang KL, Chen SJ, Tuan TC, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Lo LW, Hu YF, Chung FP, Tsao HM, Chen TJ, Lip GY, Chen SA. Risk and prediction of dementia in patients with atrial fibrillation–a nationwide population‐based cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2015;199:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thacker EL, McKnight B, Psaty BM, Longstreth WT Jr, Sitlani CM, Dublin S, Arnold AM, Fitzpatrick AL, Gottesman RF, Heckbert SR. Atrial fibrillation and cognitive decline: a longitudinal cohort study. Neurology. 2013;81:119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nishtala A, Piers RJ, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, Davis‐Plourde KL, Saczynski JS, McManus DD, Benjamin EJ, Au R. Atrial fibrillation and cognitive decline in the Framingham Heart Study. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:166–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Singh‐Manoux A, Fayosse A, Sabia S, Canonico M, Bobak M, Elbaz A, Kivimäki M, Dugravot A. Atrial fibrillation as a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2612–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bunch TJ, Weiss JP, Crandall BG, May HT, Bair TL, Osborn JS, Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB, Horne BD, Lappe DL, Day JD. Atrial fibrillation is independently associated with senile, vascular, and Alzheimer's dementia. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Bruijn RF, Heeringa J, Wolters FJ, Franco OH, Stricker BH, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Ikram MA. Association between atrial fibrillation and dementia in the general population. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:1288–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allman PH, Aban IB, Tiwari HK, Cutter GR. An introduction to Mendelian randomization with applications in neurology. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;24:72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lau DH, Nattel S, Kalman JM, Sanders P. Modifiable risk factors and atrial fibrillation. Circulation, 2017;136:583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Edwards GA III, Gamez N, Escobedo G Jr, Calderon O, Moreno‐Gonzalez I. Modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer's Disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gan W, Walters RG, Holmes MV, Bragg F, Millwood IY, Banasik K, Chen Y, Du H, Iona A, Mahajan A, Yang L, Bian Z, Guo Y, Clarke RJ, Li L, McCarthy MI, Chen Z;China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group . Evaluation of type 2 diabetes genetic risk variants in Chinese adults: findings from 93,000 individuals from the China Kadoorie Biobank. Diabetologia. 2016;59:1446–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burgess S, Davies NM, Thompson SG. Bias due to participant overlap in two‐sample Mendelian randomization. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]