Abstract

Background

Social skills programmes (SSP) are treatment strategies aimed at enhancing the social performance and reducing the distress and difficulty experienced by people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and can be incorporated as part of the rehabilitation package for people with schizophrenia.

Objectives

The primary objective is to investigate the effects of social skills training programmes, compared to standard care, for people with schizophrenia.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (November 2006 and December 2011) which is based on regular searches of CINAHL, BIOSIS, AMED, EMBASE, PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and registries of clinical trials. We inspected references of all identified studies for further trials.

A further search for studies has been conducted by the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group in 2015, 37 citations have been found and are currently being assessed by review authors.

Selection criteria

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials for social skills programmes versus standard care involving people with serious mental illnesses.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently. For dichotomous data we calculated risk ratios (RRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) on an intention‐to‐treat basis. For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD) and 95% CIs.

Main results

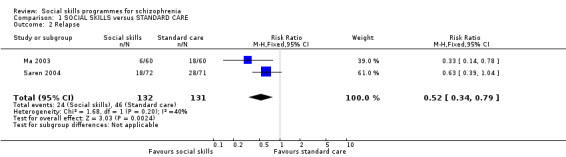

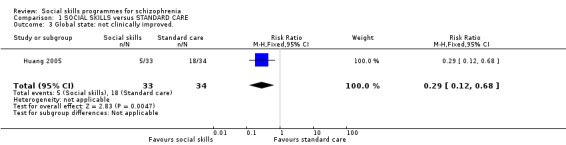

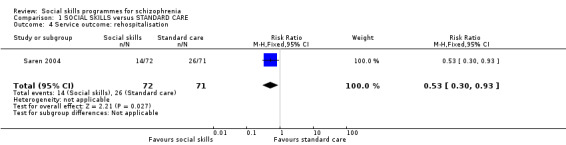

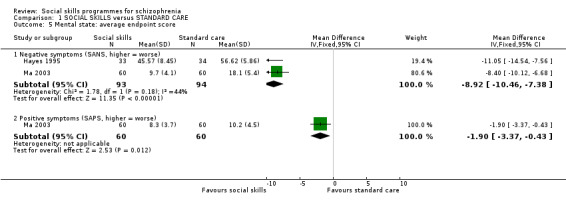

We included 13 randomised trials (975 participants). These evaluated social skills programmes versus standard care, or discussion group. We found evidence in favour of social skills programmes compared to standard care on all measures of social functioning. We also found that rates of relapse and rehospitalisation were lower for social skills compared to standard care (relapse: 2 RCTs, n = 263, RR 0.52 CI 0.34 to 0.79, very low quality evidence), (rehospitalisation: 1 RCT, n = 143, RR 0.53 CI 0.30 to 0.93, very low quality evidence) and participants’ mental state results (1 RCT, n = 91, MD ‐4.01 CI ‐7.52 to ‐0.50, very low quality evidence) were better in the group receiving social skill programmes. Global state was measured in one trial by numbers not experiencing a clinical improvement, results favoured social skills (1 RCT, n = 67, RR 0.29 CI 0.12 to 0.68, very low quality evidence). Quality of life was also improved in the social skills programme compared to standard care (1 RCT, n = 112, MD ‐7.60 CI ‐12.18 to ‐3.02, very low quality evidence). However, when social skills programmes were compared to a discussion group control, we found no significant differences in the participants social functioning, relapse rates, mental state or quality of life, again the quality of evidence for these outcomes was very low.

Authors' conclusions

Compared to standard care, social skills training may improve the social skills of people with schizophrenia and reduce relapse rates, but at present, the evidence is very limited with data rated as very low quality. When social skills training was compared to discussion there was no difference on patients outcomes. Cultural differences might limit the applicability of the current results, as most reported studies were conducted in China. Whether social skills training can improve social functioning of people with schizophrenia in different settings remains unclear and should be investigated in a large multi‐centre randomised controlled trial.

Keywords: Adult; Female; Humans; Male; Social Skills; Assertiveness; Communication; Cultural Characteristics; Patient Readmission; Patient Readmission/statistics & numerical data; Program Evaluation; Psychotic Disorders; Psychotic Disorders/rehabilitation; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Recurrence; Schizophrenia; Schizophrenia/rehabilitation; Schizophrenic Psychology; Stress, Psychological; Stress, Psychological/rehabilitation

Plain language summary

Social skills programmes for people with schizophrenia

Social skills programmes (SSP) use behavioural therapy and techniques for teaching individuals to communicate their emotions and requests. This means they are more likely to achieve their goals, meet their needs for relationships and for independent living as well as getting on with other people and socially adjusting. Social skills programmes involve 'model learning' (role playing) which was introduced to improve general 'molecular' skills (eye contact, fluency of speech, gestures) and 'molar' skills (managing negative emotions, giving positive feedback). Social skills programmes enhance social performance and reduce the distress and difficulty experienced by people with schizophrenia. Social skills programmes can be incorporated as part of a rehabilitation package for people with schizophrenia.

The main objective of this review is to investigate the effectiveness of social skills programmes, compared to standard care or discussion groups, for people with schizophrenia. Based on searches carried out in 2006 and 2011, this review includes 13 trials with a total of 975 participants. Authors chose seven main outcomes of interest, all data for these outcomes were rated to be very low quality. The review found significant differences in favour of social skills programmes compared to standard care on all measures of social functioning. Rates of relapse were lower for social skills compared to standard care and there was a significant difference in favour of social skills on people’s mental state. Quality of life was also improved in the social skills programme compared to standard care. However, when social skills programmes were compared to discussion groups, there were no significant differences in people’s social functioning, relapse rates, mental state or quality of life.

Compared to standard care, social skills programmes may improve the social skills of people with schizophrenia and reduce relapse rates. However, at the moment evidence is very limited with data only of very low quality available. Cultural differences might also limit the relevance of current results, as most reported studies were conducted in China. Whether social skills programmes or training can improve the social functioning of people with schizophrenia in different settings remains unclear and should be further investigated in a large multi‐centre randomised controlled trial.

Ben Gray, Senior Peer Researcher, McPin Foundation.http://mcpin.org/

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE for schizophrenia.

| SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Settings: Intervention: SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE | |||||

| Social functioning Various scales Follow‐up: 8‐52 weeks | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 585 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 | The four RCTs that provided data for this comparison used different scales to measure social functioning and so data were not pooled for this comparison. |

| Relapse Follow‐up: 6‐12 months | 351 per 1000 | 183 per 1000 (119 to 277) | RR 0.52 (0.34 to 0.79) | 263 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,6,7 | |

| Rehospitalisation Follow‐up: 12 months | 366 per 1000 | 194 per 1000 (110 to 340) | RR 0.53 (0.3 to 0.93) | 143 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,8 | |

|

Mental state: general symptoms (BPRS) Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

The mean mental state: general symptoms in the intervention groups was 4.01 lower (7.52 to 0.50 lower) | 91 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,8 | |||

| Global state: not clinically improved. CGI Follow‐up: 6 months | 529 per 1000 | 153 per 1000 (63 to 360) | RR 0.29 (0.12 to 0.68) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5 | |

| General functioning MRSS Follow‐up: 8 weeks | The mean General functioning: average endpoint score (various scales) ‐ MRSS in the intervention groups was 10.6 lower (17.47 to 3.73 lower) | 112 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5 | |||

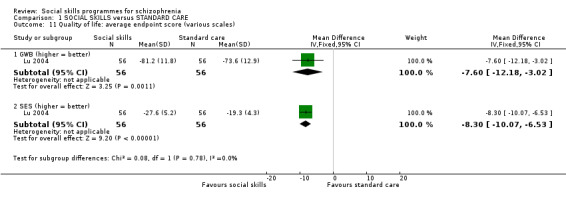

| Quality of life GWB. Scale from: 10 to 40. Follow‐up: 8 weeks | The mean Quality of life in the intervention groups was 7.6 lower (12.18 to 3.02 lower) | 112 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: very serious. Only one of the trials had adequate sequence generation. Allocation concealment was unclear in all trials and none were blinded. Two trials addressed incomplete data adequately and three were free from selective reporting. It was unclear in all trials whether they were free from other biases. 2 Inconsistency: serious. See comment. 3 Imprecision: very serious. Data were not combined, but for each single study the 95% confidence intervals around the pooled effect estimate are very wide. 4 Publication bias: strongly suspected. Less than five studies provided data for this outcome. 5 Risk of bias: very serious. The RCT that provided data for this outcome did not have adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding. It was unclear whether there were other biases. 6 Risk of bias: very serious. Neither of the two RCTs were blinded, and it was unclear in both if there was adequate allocation concealment. Only one had adequate sequence generation and one addressed incomplete data adequately. It was unclear in both if they were free from other biases. 7 Inconsistency: serious. There was moderate heterogeneity for this outcome. This may be explained by differences in type of social skills training. Ma 2003 included sessions on medication and symptom management as well as social skills, whereas in Saren 2004 the focus was on interpersonal interaction. 8 Risk of bias: very serious. The RCT that provided data for this outcome had unclear allocation concealment and was not blinded. It was unclear if it was free from other biases.

Summary of findings 2. SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL for schizophrenia.

| SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Settings: Intervention: SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL | |||||

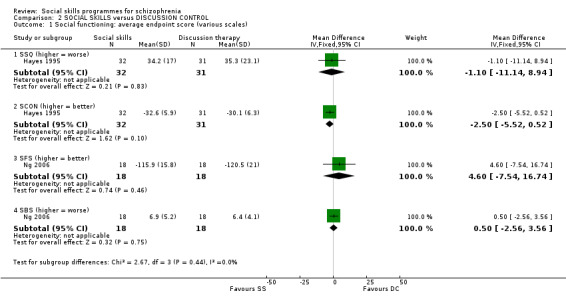

| Social functioning Various scales Follow‐up: 6 months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 63 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | The two RCTs that provided data for this comparison used different scales to measure social functioning and so data were not pooled for this comparison. |

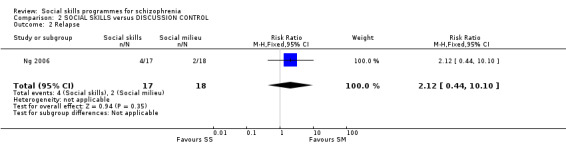

| Relapse Follow‐up: 6 months | 111 per 1000 | 235 per 1000 (49 to 1000) | RR 2.12 (0.44 to 10.1) | 35 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | |

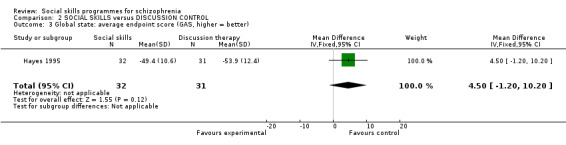

| Global state GAS Follow‐up: 6 months | The mean Global state: average endpoint score in the intervention groups was 4.5 higher (1.2 lower to 10.2 higher) | 63 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,5 | |||

|

Mental state: general symptoms Follow‐up: 6 months |

The mean mental state: general symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.22 higher (4.05 lower to 4.49 higher) | 99 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,4 | |||

| Quality of life QLS Follow‐up: 6 months | The mean Quality of life: average endpoint score in the intervention groups was 3.7 higher (6.47 lower to 13.87 higher) | 63 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,5 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: serious. Only one of the RCTs had adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment, neither were blinded nor addressed incomplete data adequately. Only one was free from selective reporting it was unclear if either was free from selective reporting. 2 Imprecision: serious. The 95% confidence intervals are very wide and include both significant benefit and harm of the intervention. 3 Publication bias: strongly suspected. Less than three studies provided data for this outcome. 4 Risk of bias: serious. The RCT that provided data for this outcome was not blinded. It was unclear whether incomplete data were adequately addressed and whether it was free from other biases. 5 Risk of bias: very serious. The RCT that provided data fro this outcome was not blinded, did not adequately address incomplete data and was not free from selective reporting. It was unclear if the sequence generation and allocation concealment was adequate and whether it was free from other biases.

Background

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia can occur as a single episode of illness. By far the greater proportion of sufferers, however, have remission and relapses; for up to 41% of those who develop schizophrenia it becomes a chronic and often disabling illness (Prudo 1987). Antipsychotic medications are commonly used for management of symptoms. However, the conclusions reached by meta‐analytical methods are that treatment with antipsychotic medication 'should be combined and coordinated with other interventions involving the patient's family, and social psychological and psychotherapeutic support' (MSPI 1997). These treatments are subsumed under the general term 'rehabilitation'.

Preceding the movement of care into the community, the rehabilitation process was mostly provided by the large psychiatric hospitals in which sufferers often spent many years (Wing 1961; Wing 1970). This pattern of care has now changed (Hume 1995). During the 1980s many psychiatric hospitals were closed, community‐based services were developed, and psychiatric units in general hospitals were established. Currently, few chronically mentally ill people spend longer than a few weeks per year in hospital. The rest of their care takes place in the community. Up to 75% of people with chronic schizophrenia are maintained in the community in the United Kingdom ‐ chronic in this case is defined as lasting more than 2.5 years (Davies 1990). Relative to other chronic illnesses, the personal and economic costs of schizophrenia are considerable (Knapp 1994). It is therefore important to offer rehabilitation treatments that are both clinically effective and cost‐effective.

Description of the intervention

As a part of the rehabilitation package for people with schizophrenia, social skills programmes (SSP) aim to utilise behaviour therapy principles and techniques for teaching individuals to communicate their emotions and requests, so they are more likely to achieve their goals and meet their needs for relationships and roles required for independent living and social competence (Kopelowicz 2006).

SSP involves 'model learning' (role playing) which was introduced to improve general 'molecular' skills (eye contact, fluency of speech, gestures, etc) and 'molar' skills (managing negative affects, giving positive feedback, etc.) (Brenner 1994). A problem‐solving model was later incorporated and rehabilitation topics that are particularly relevant for people with schizophrenia were introduced (Liberman 1993). The application of these modules appears far more effective than control conditions, particularly in terms of generalisation of skills and social adjustment (Marder 1996; Wallace 1998).

How the intervention might work

Learning‐based procedures used in SSP include identifying the problems and setting the goals in collaboration with the client. Through role play or behavioural rehearsal, participants demonstrate the required skills and positive or corrective feedback is given to them accordingly. By social modelling and behavioural practice, participants observe and repeat the skills until the communications reach a level of quality tantamount to success in the real‐life situation. Homework assignments are then given to motivate participants to implement these communications in real‐life situations.

Why it is important to do this review

This review focuses on social skills programmes, which are some of the most established psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia (Liberman 1986; Liberman 1986a) but vary in use across the world. Essentially, social skills programmes are treatment strategies aimed at enhancing the social performance and reducing the distress and difficulty experienced by people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Few reviews exist (Kopelowicz 2006) and none are maintained.

Objectives

To investigate the effects of social skills training programmes, compared to standard care, for people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials. If a trial had been described as 'double blind' but implied randomisation, we planned to include such trials in a sensitivity analysis. If their inclusion did not result in a substantive difference, they would have remained in the analyses. If their inclusion did result in statistically significant differences, we would not have added the data from these lower quality studies to the results of the better trials, but presented such data within a subcategory. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by alternate days of the week. Where people were given additional treatments within a social skills trial, we only included data if the adjunct treatment was evenly distributed between groups and it was only the social skills programme that was randomised.

Types of participants

Adults, however defined, with schizophrenia or related disorders, including schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder, again, by any means of diagnosis.

We were interested in making sure that information is as relevant to the current care of people with schizophrenia as possible so proposed to clearly highlight the current clinical state (acute, early post‐acute, partial remission, remission) as well as the stage (prodromal, first episode, early illness, persistent) and as to whether the studies primarily focused on people with particular problems (for example, negative symptoms, treatment‐resistant illnesses).

Types of interventions

1. Social skills training programmes

Defined as any structured psychosocial intervention, whether group or individual, aimed at enhancing the social performance and reducing the distress and difficulty in social situations. The key components are; i. a careful behavioural‐based assessment of a range of social and interpersonal skills; ii. An importance placed on both verbal and non‐verbal communication; as well as the individual's ability to; i. perceive and process relevant social cues; and ii. to respond to and provide appropriate social reinforcement. This approach has the goal of building up individual behavioural elements into complex behaviours. The aim is to develop more effective social communication. There is considerable emphasis not just on clinic‐based interventions (including modelling, role‐play and social reinforcement) but also the setting of homework tasks and the applicability of the treatment.

Programmes where social skills training are a component part of a more complex rehabilitation intervention were excluded, as were token economies, life skills programmes and other similar milieu‐based interventions which may include an element of social skills training in a broader programme.

Programmes of five sessions and less are considered as 'brief ', and six or more as 'long'. Place of residence is defined as either 'hospital' or 'community' for the purposes of this review. For example, if people are in hospital at time of attending a day‐hospital based programme they are considered to be receiving 'hospital‐based' care. If, on the other hand, they attend the day hospital from home then they are considered to be receiving' community‐based' care. Trained staff are those personnel who hold a professionally recognised health care qualification.

2. The control treatment

Defined as standard care without a dedicated programme of the type described above.

Types of outcome measures

If possible we divided outcomes into short term (less than six months), medium term (seven to 12 months) and long term (over one year).

Primary outcomes

1. Social functioning

No clinically important change in general social functioning

2. Relapse

3. Mental state

No clinically important change in general mental state

Secondary outcomes

1. Social functioning

1.2 Average endpoint general social skills score 1.3 Average change in general social skills scores 1.4 No clinically important change in specific social skills 1.5 Average endpoint specific social skills score 1.6 Average change in specific social skills scores

2. Global state

2.1 No clinically important change in global state (as defined by individual studies) 2.2 Average endpoint global state score 2.3 Average change in global state scores

3. Service outcomes

3.1 Hospitalisation 3.2 Time to hospitalisation

4. Mental state (with particular reference to the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia)

4.1 Average endpoint general mental state score 4.2 Average change in general mental state scores 4.3 No clinically important change in specific symptoms (positive symptoms of schizophrenia, negative symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, mania) 4.4 Average endpoint specific symptom score 4.5 Average change in specific symptom scores

5. General functioning

5.1 No clinically important change in general functioning 5.2 Average endpoint general functioning score 5.3 Average change in general functioning scores 5.4 Employed

6. Behaviour

6.1 No clinically important change in general behaviour 6.2 Average endpoint general behaviour score 6.3 Average change in general behaviour scores 6.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of behaviour 6.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of behaviour 6.6 Average change in specific aspects of behaviour

7. Adverse effects ‐ general and specific

7.1 Clinically important general adverse effects 7.2 Average endpoint general adverse effect score 7.3 Average change in general adverse effect scores 7.4 Clinically important specific adverse effects 7.5 Average endpoint specific adverse effects 7.6 Average change in specific adverse effects 7.7 Death ‐ suicide and natural causes

8. Engagement with services

9. Satisfaction with treatment

9.1 Leaving the studies early 9.2 Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment 9.3 Recipient of care average satisfaction score 9.4 Recipient of care average change in satisfaction scores 9.5 Carer not satisfied with treatment 9.6 Carer average satisfaction score 9.7 Carer average change in satisfaction scores

10. Quality of life

10.1 No clinically important change in quality of life 10.2 Average endpoint quality of life score 10.3 Average change in quality of life scores 10.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of quality of life 10.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of quality of life 10.6 Average change in specific aspects of quality of life

11. Economic outcomes

11.1 Direct costs 11.2 Indirect costs

12. 'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008) and used GRADE profiler (GRADE 2004) to import data from RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2008) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes was rated as important to patient‐care and decision making. We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the Table 1 and Table 2:

1. Social functioning ‐ Clinically significant response on social skills ‐ as defined by each of the studies

2. Clinical response

Clinically significant response in global state ‐ as defined by each of the studies

Healthy days

3. Service utilisation outcomes

Hospital admission

Days in hospital

4. Adverse effect ‐ Any important adverse event

5. Quality of life ‐ Improved to an important extent

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register of Trials (November 2006, December 21, 2011) using the following search strategy:

((*social* OR *personal*) AND (*skill* OR *program* OR *training*)) in Title, Abstract and Indexing Terms Fields of REFERENCE and (*social skill* OR *social support* OR *sociotherapy* OR *socioenvironmental* OR *interpersonal*) in Intervention Field of STUDY

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register of Trials is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group Module). There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected references of all identified studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors Muhammad Okba Al Marhi (MOA), (Mohamad Alsabbag (MA) and Muhammad Jawoosh (MJ) independently inspected citations from the November 2006 search and identified relevant abstracts. A random 20% sample was independently re‐inspected by Muhammad Qutayba Almerie (MQA) to ensure reliability. Where disputes arose, the full report was acquired for more detailed scrutiny. Full reports of the abstracts meeting the review criteria were obtained and inspected by MOA and MS. Again, a random 20% of reports were re‐inspected by MQA in order to ensure reliable selection.

For the June 2010 search, review authors Nicola Maaya (NM) and Hanna Bergman (HB) independently inspected citations, and identified and inspected relevant abstracts. A random 20% sample was independently re‐inspected by Karla Soares Weiser (KSW) to ensure reliability. Full reports were obtained and inspected by NM and HB and a random 20% of reports were re‐inspected by KSW. Where it was not possible to resolve disagreement by discussion, we attempted to contact the authors of the study for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

For the November 2006 search, review authors MOA, MA and MJ extracted data from included studies. Where further clarification was needed, the authors' of trials were contacted to provide missing data. Any disagreements were discussed and the decisions documented.

For the June 2012 search, review author NM extracted data from all included studies. In addition, to ensure reliability, HB independently extracted data from a random sample of these studies, comprising 10% of the total. Again, any disagreement was discussed, decisions documented and, if necessary, authors of studies were contacted for clarification. With remaining problems KSW helped clarify issues and these final decisions were documented. Data presented only in graphs and figures were extracted whenever possible, but included only if two review authors independently had the same result. Attempts were made to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. If studies were multi‐centre, where possible, we extracted data relevant to each component centre separately. The data from the Chinese papers were extracted by a speaker of that language (JX); but these Chinese language studies were not re‐inspected by review authors.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

Data were extracted onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a. the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b. the measuring instrument had not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial.

Ideally, the measuring instrument should either be i. a self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly, in Description of studies we have noted if this is the case or not.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. Endpoint and change data were combined in the analysis as we used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Higgins 2009, Chapter 9.4.5.2 ).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion: a) standard deviations SDs) and means were reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors; b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the SD, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996); c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), which can have values from 30 to 210), the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐S min), where S is the mean score and S min is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied; however, we did not find any skewed endpoint data. When continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. Skewed data from studies of less than 200 participants would have been entered as other data within the data and analyses section rather than into a statistical analysis. Skewed data pose less of a problem when looking at means if the sample size is large and would have been entered into statistical syntheses.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, if necessary we converted variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, efforts were made to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This was done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986), this can be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicates a favourable outcome for social skills training.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again review authors NM and HB worked independently to assess risk of bias by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009) to assess trial quality. This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus, with the involvement of another member of the review group. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. Non‐concurrence in quality assessment was reported, but if disputes arose as to which category a trial is to be allocated, again, resolution was made by discussion.

The level of risk of bias is noted in both the text of the review and in the Table 1 and Table 2.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). For statistically significant results we had planned to calculate the number needed to treat to provide benefit /to induce harm statistic (NNTB/H), and its 95% confidence interval (CI) using Visual Rx (http://www.nntonline.net/) taking account of the event rate in the control group. This, however, has been superseded by Table 1 and Table 2, and the calculations therein.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated the mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)). However, if scales of very considerable similarity were used, we presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and we calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

We did not have any data from cluster trials. Had there been data from these types of trials, and where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we would have presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error and contacted first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and adjusted for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). If clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted the data for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1 + (m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICChad not been reported, it would have been assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we would have only used data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, the additional treatment arms were presented in comparisons. If data were binary these were simply added and combined within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous we combined data following the formula in section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, these data were not reproduced.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' table/s by down‐rating quality. Finally, we also downgraded quality within the 'Summary of findings' table/s where loss was 25% to 50% in total.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50%, we presented data for the total number of participants randomised for studies that used an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis; where studies did not use an ITT analysis, we presented completer‐only data.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50% and completer‐only data were reported, we reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there are missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals available for group means, and either P value or T value available for differences in mean, we can calculate them according to the rules described in the Handbook (Higgins 2011): When only the SE is reported, SDs are calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Handbook (Higgins 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, T or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae do not apply, we can calculate the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We planned to examine the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, if LOCF data had been used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data had been assumed, we planned to reproduce these data and indicate that they were the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, these were fully discussed.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arose, these were fully discussed.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

Heterogeneity between studies was investigated by considering the I2 method alongside the Chi2 'P' value. The I2 provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. 'P' value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). an I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic was interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Section 9.5.2 ‐ Higgins 2009). When substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. As we did not have more than 10 studies providing data for outcomes, we did not need to use funnel plots. If future versions of this review do require funnel plots, we will seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model. It puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. Therefore, we chose the fixed‐effect model for all analyses. The reader is, however, able to choose to inspect the data using the random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses ‐ only primary outcomes

We planned to perform subgroup analyses to assess the impact of the following possible sources of heterogeneity for any of the social skills training programmes: brief versus long programmes, clinical state, stage or problem. However, there were not enough data to undertake these analyses.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, this was reported. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, the graph was visually inspected and outlying studies were successively removed to see if heterogeneity was restored. For this review we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, data were presented. If not, data were not pooled and issues discussed. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off but are investigating use of prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity was obvious we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

We also planned to conduct sensitivity analyses for the main outcomes for trials with the implication of randomisation, assumptions made for lost binary data, trials with high risk of bias, imputed values and fixed‐effect versus random‐effects models. However, all of the outcomes had less than 10 trials that reported data.

Results

Description of studies

Please see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

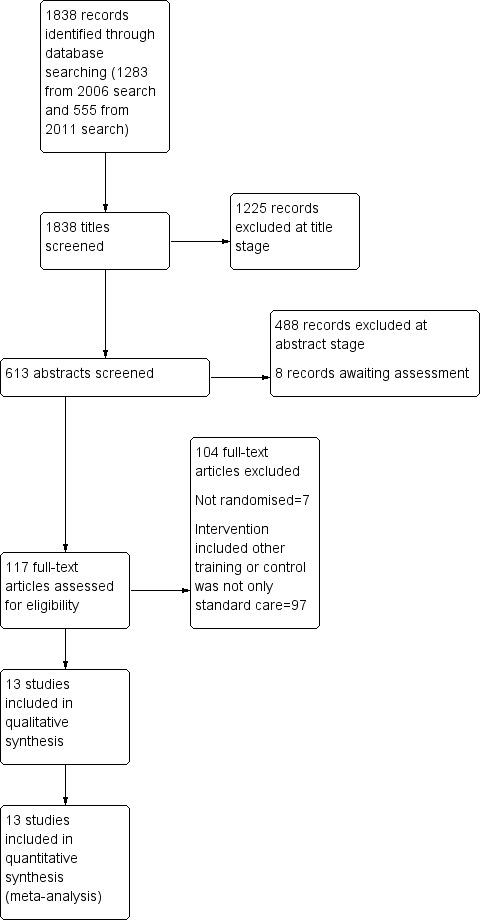

The November 2006 search identified 1283 references and a search in December 2011 identified a further 555 references. Agreement about which reports may have been randomised was 100%. See also Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The current review includes 17 reports describing 13 studies involving 975 participants.

1. Methods

All studies were stated to be randomised. Dobson 1995, Hayes 1995, Huang 2005 and Ng 2006 all stated that the assessors were blinded to the participant's treatment allocation; it was unclear in Potelunas 1982 whether all raters were blinded. In Tsang 2001, the raters were blinded, but it was unclear whether the participants were. Chien 2003, Cui 2004, Kopelowicz 1998, Lu 2004, Ma 2003, Mayang 1990 and Saren 2004 did not report that blinding was attempted. For further details please see sections below on Allocation and Blinding in Risk of bias in included studies.

2. Duration

Five trials were undertaken for no longer than three months: Chien 2003 four weeks; Cui 2004 12 weeks; Kopelowicz 1998 three months, Lu 2004 eight weeks; Mayang 1990 four sessions with a four‐week follow‐up (it did not report the frequency of the sessions); and Potelunas 1982 six weeks. Seven trials were longer than three months: Dobson 1995 involved nine weeks of training with three months of follow‐up for all participants, although the follow‐up period lasted up to one year for the social skills group; Hayes 1995 lasted for 18 weeks, but had an additional period of six months where the patients received decreasing frequency of training; the duration of Huang 2005 was six months; Ma 2003 had eight weeks of intervention and 26 weeks follow‐up; Ng 2006 was eight weeks with a six‐month follow‐up; Saren 2004 was 10 weeks with 12 months follow‐up; and Tsang 2001 was 10 weeks with a three‐month follow‐up period.

3. Participants

All participants were people with a chronic mental illness, mostly with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. One of the studies randomised only men (Cui 2004) and two studies randomised only women (Mayang 1990 and Potelunas 1982); the others included both sexes. Data on mean age were available from seven trials. The average age was between 33 and 48 years. Ma 2003 did not report any demographic information about the participants.

All studies included patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective psychoses. Three studies used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM‐IV) criteria, one used the third edition (DSM‐III), two used the third version of the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD‐III), three used the second version (CCMD‐II), and four studies did not report the diagnostic criteria.

4. Setting

Nine studies used a hospital setting (Chien 2003; Cui 2004; Dobson 1995; Huang 2005; Kopelowicz 1998; Lu 2004; Mayang 1990; Ng 2006; Tsang 2001); in four studies (Hayes 1995; Ma 2003; Potelunas 1982; Saren 2004) the participants were outpatients. Three of the included trials were conducted in USA, five in China, one in Taiwan, two in Hong Kong, one in Canada and one in Australia.

5. Interventions

5.1 Experimental treatment

In Chien 2003, the social skills training focused on conversation and assertiveness skills. Participants attended a one‐hour session twice a week for four weeks. In Dobson 1995, the focus was on communication and assertiveness for four one‐hour sessions per week over a nine‐week period.

The social skills training programme used in Cui 2004 was the UCLA Social and independent Living Skills programme, which includes: i) general social interpersonal skills training, using video demonstration, role play and discussion; ii) educating patients of the purpose and function of antipsychotic medication; iii) medication management; iv) how to recognise a drug adverse effect; v) opportunity to discuss issues relating to drug therapy. The training lasted 90 to 120 minutes per session, and there were three sessions per week for 12 weeks.

Ma 2003 also used the UCLA Social and independent Living Skills programme as the social skills training (90 to 120 minutes per session, one session a week for eight weeks) and Kopelowicz 1998 used an adapted version, which was translated into Spanish (participants attended three months of training four days a week, although the length of each session was not reported).

The social skills training in Hayes 1995 emphasised interpersonal skills, social problem solving, positive time use skills, generalisation enhancement techniques, and used instructions, modelling, behaviour rehearsal, feedback, and structured homework. The training consisted of 36 sessions of 75 minutes over 18 weeks, followed by a six‐month period in which patients received decreasing frequency of training.

The social skills training in Huang 2005 was delivered in groups of eight to nine people, and each session was two hours per weeks for 24 weeks.The social skills group also received routine drug therapy, recreational activities and work in the wards, which was the standard care for all patients.

In Lu 2004, the training included targeted problem solving training to improve patients' attention and planning skills with the aim of gradually improving patient's social function. Training was 60 minutes per session and two sessions per week for eight weeks.

In Mayang 1990and Ng 2006, the social skills training focused on problem solving skills (receiving skills, processing skills and sending skills) and involved instructions, modelling, feedback, role playing, social reinforcement. The training consisted of four sessions of 45 minutes of training in Mayang 1990 and 30 to 32 hours of treatment within eight weeks in Ng 2006.

In Potelunas 1982, the social skills training consisted of four one‐hour sessions over four weeks of videotaped presentation of eight problem situations, videotaped modelling, behaviour rehearsal, coaching and feedback, which occurred within a work adjustment programme.

In Saren 2004, the training focused on making eye contact, facial expressions, tone of voice, language fluency, posture and gestures and overall enthusiasm. Training was provided in groups of between 10 to 12 people, for 60 to 90minutes per session, three sessions per week for 10 weeks. In Tsang 2001, social skills training also consisted of basic social skills (facial expression, gestures etc.) and basic social survival skills (personal appearance, tidiness), but also included core work‐related skills. In this study there were two intervention groups: one received social skills training plus follow‐up support, which consisted of contact with group members and the trainer; the other group received only the social skills training and no follow‐up support.The training consisted of 10 weekly group sessions lasting one and a half to two hours, with approximately six to eight people in each group.

5.2 Control treatment

In five of the studies (Chien 2003; Cui 2004; Huang 2005; Kopelowicz 1998; Tsang 2001), the comparison treatment was standard psychiatric care. However, three of the studies (Dobson 1995; Hayes 1995; Ng 2006) used a discussion group as the control treatment to control for any confounding effects that arise from interacting with the therapist during social skills training. Dobson 1995 used a social milieu, which consisted of structured activities including supportive discussion groups, exercise groups and activity groups, and occurred at same time of day and same length of time as social skills training group. Hayes 1995 used a discussion group condition, which focused on interpersonal relations and purposeful use of time using open ended questions, paraphrasing, reflecting, and summarising the participants' comments to promote self‐disclosure. In Ng 2006, the control treatment was supportive group discussion with topics that included practical tips on money management and information on application for social security allowances, with special attention paid to avoid discussions on interpersonal skills issues and use of behavioural techniques. Two studies (Mayang 1990 and Potelunas 1982) had both standard care and a discussion group as their control treatments. In Mayang 1990, the interaction group condition consisted of non‐treatment interaction with trainers, and in Potelunas 1982, the discussion control was four one‐hour sessions over four weeks of videotaped presentation and discussion of eight problem situations.

7. Outcomes scales

7.1 Social functioning

i) Disabilities Assessment Schedule ‐ DAS (WHO 1988) This scale covers six domains: cognition – understanding and communicating; mobility; self‐care – hygiene, dressing, eating and staying alone; interacting with other people; life activities – domestic responsibilities, leisure, work and school; participation – joining in community activities. Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Ma 2003 reported data from this scale.

ii) Social Disability Schedule ‐ SDSS (WHO 1988) The SDSS is a Chinese simplified version of the World Health Organization’s Disability Assessment Schedule and assesses 10 different aspects of social functioning (WHO 1988). Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Lu 2004 and Saren 2004 reported data from this scale.

iii) Social avoidance and disability scale ‐ SAD (Watson 1969) The Social Avoidance and Distress Scale (SAD) is a 28‐item, self‐rated scale used to measure various aspects of social anxiety including distress, discomfort, fear, anxiety, and the avoidance of social situations. Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Saren 2004 reported data from this scale.

iv) Scale of Social Skills for Psychiatric Inpatients ‐ SSPI (Guo 1995) This scale is a Chinese rating scale, commonly used for assessing response to antipsychotic treatment. Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Huang 2005 reported data from this scale.

v) Social Situations questionnaire ‐ SSQ (Bryant 1974) Measures self‐perception of social difficulty; participants rate their anxiety and avoidance of 30 different social situations from zero “no difficulty” to four “avoidance if possible”. Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. It is not clear whether this is a validated scale. Hayes 1995 reported data from this scale.

vi) Social Behaviour Schedule ‐ SBS (Wykes 1986) The scale covers 21 behaviour areas such as destructive behaviours, personal appearance and hygiene, measured on a five‐point Likert scale from zero (no problem or acceptable behaviour) to four (serious problem). Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Hayes 1995 reported data from this scale.

vii) Social functioning scale ‐ SFS (Birchwood 1990) This scale is an 81‐item self‐administered questionnaire covering several behaviour areas: employment, social withdrawal, pro‐social activities, recreation, interpersonal functioning, perceived independence, competence and perceived independence performance. Higher scores indicate a better outcome. Ng 2006 reported data from this scale.

viii) Conversation with a stranger task ‐ SCON (Wallace 1985) This assesses the participants’ skill in initiating a conversation in an unstructured five‐minute interaction with a stranger. It is scored on a rating scale from one “skill not evident” to five “very high level of skill”. Coding of the SCON used the system described by Bellack 1990. It is unclear whether the SCON is a validated scale. Hayes 1995 reported data from this scale.

7.2 Mental state

i) Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‐ SANS (Andreasen 1983) This scale allows a global rating of the following negative symptoms: alogia (impoverished thinking), affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐asociality, and attention impairment. Assessments are made on a six‐point scale from zero (not at all) to five (severe). Higher scores indicate more symptoms. Hayes 1995 and Ng 2006 reported data from this scale.

ii) Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms – SAPS (Andreasen 1983). This is a six‐point scale providing a global rating of positive symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations and disordered thinking. Higher scores indicate more symptoms. Ma 2003 reported data from this scale.

iii) Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) This is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental state. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from zero to six or one to seven. Scores can range from zero to 126, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms. Cui 2004, Hayes 1995 and Ng 2006 reported data from this scale.

7.3 General Functioning

i) Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale ‐ MRSS (Affleck 1984) In this scale four individual areas are rated on an 8‐point scale: dependency, occupation and leisure activity, social isolation, and current symptoms. Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Lu 2004 reported data from this scale.

7.4 Global state

i) Global Assessment Scale ‐ GAS (Endicott 1976) This is an observer‐rated scale for evaluating the overall functioning of a patient during a specified time period on a continuum from psychological or psychiatric sickness to health. Score ranges from zero to 100, where higher score indicates a better outcome. Hayes 1995 reported data from this scale.

ii) Clinical Global Impression Scale ‐ CGI (Guy 1976) This is used to assess both severity of illness and clinical improvement, by comparing the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores showing decreased severity and/or overall improvement. Huang 2005 reported data from this scale.

7.5 Quality of Life

i) Quality of Life Scale ‐ QLS (Heinrich 1984) This six‐point quality of life scale has been designed as an outcome instrument for schizophrenic deficit syndrome as well as to measure impaired functioning in studies of chronic schizophrenia, to assess the deficit syndrome's impact on the patient's life. There are seven severity steps (zero to six, six being adequately functioning and zero being deficient). The time frame is one month. Four item categories have been identified by factor analysis 1) interpersonal relationships (seven items), 2) instrumental role (four items), 3) intrapsychic function (seven items) and 4) commonplace objects and activities. Hayes 1995 reported data from this scale.

ii) General Well‐Being Scale ‐ GWB (Dupuy 1977) This is a self‐administered questionnaire consisting of 18 items covering six dimensions of anxiety, depression, general health, positive well‐being, self‐control and vitality. There is a total score running from zero to 110, higher scores indicate less distress. Lu 2004 reported data from this scale.

iii) Rosenberg Self‐esteem scale ‐ SES (Rosenberg 1965) The Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale is a 10‐item self‐report measure of global self‐esteem. It consists of 10 statements related to overall feelings of self‐worth or self‐acceptance. The items are answered on a four‐point scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The SES has also been administered as an interview. Scores range from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher self‐esteem. Lu 2004 reported data from this scale.

Excluded studies

We excluded 104 studies. Of these, seven studies were not randomised. The other 97 studies were randomised but either the experimental groups were allocated to a programme that had some elements of social skills but also incorporated other training interventions, for example life skills and cognitive behavioural therapies, or the control group was not only standard care, but for example, holistic therapy. We did, however, include studies that used a discussion group as an attention control.

Awaiting assessment

Eight studies are awaiting assessment.

Ongoing studies

We found eight ongoing studies, three have social skills training programmes as the intervention (NCT00338975 2006, NCT00791882 2008, NCT00183625 2005), two include health management training with the social skills training (NCT00069433 2003, Pratt 2008), one has cognitive behavioural social skills training as the intervention (NCT00237796 2005), another social cognition and interaction training (NCT00601224 2008) and one attention shaping procedures (NCT00391677 2006).

Risk of bias in included studies

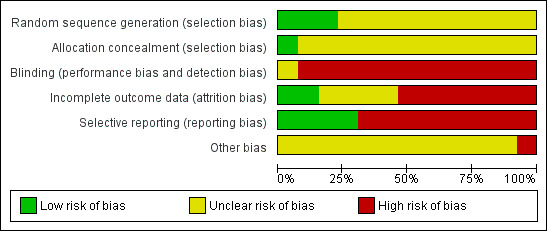

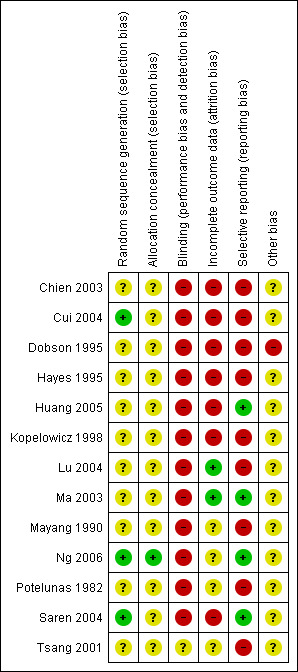

We prepared a 'Risk of bias' assessment for each trial. Our judgments regarding the overall risk of bias in individual studies is illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Overall, we felt the risk of bias in the included studies to be high.

2.

Risk of bias Summary for included studies

3.

Risk of bias Summary for included studies

Allocation

All studies were stated to be randomly assigned. However, only three of the studies described how allocation to intervention was undertaken: Cui 2004, Ng 2006 and Saren 2004 each used a random numbers table. Only Ng 2006 described the allocation concealment; it was unclear in the remaining studies.

Blinding

Only Tsang 2001 was stated to be double blind, although it was unclear if participants in the control group were blinded. In five of the studies the assessors were blinded (Dobson 1995, Hayes 1995, Huang 2005, Ng 2006 and Potelunas 1982), although in Potelunas 1982 it was unclear whether all the raters were blinded.

Incomplete outcome data

Two studies did not have any incomplete data (Lu 2004 and Ma 2003), seven studies did not address incomplete outcome data adequately and it was unclear in four of the studies (Mayang 1990, Potelunas 1982, Ng 2006 and Tsang 2001).

Selective reporting

Four of the studies were free from selective reporting (Huang 2005; Ma 2003; Ng 2006 and Saren 2004), the remaining nine studies were rated as high risk of bias for selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

It was unclear in all of the trials except Dobson 1995 whether they were free from other biases. In Dobson 1995 there was bias from allowing the control group to begin social skills training before the end of the follow‐up period and we downgraded this trial to high risk for other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

For dichotomous data we calculated risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD) and 95% CIs.

1. COMPARISON 1: SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE

1.1 Social functioning

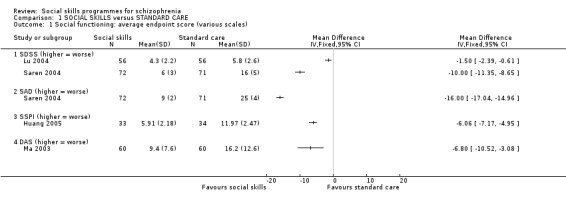

1.1.1 Social functioning: Average endpoint score

We found significant differences between social skills and standard care on all scales that measured social functioning (Analysis 1.1). Lu 2004 reported data on the Social Disability Schedule (SDSS) at eight weeks (1 RCT, n = 112, MD ‐1.50 CI ‐2.39 to ‐0.61) and Saren 2004 at 12 months (1 RCT, n = 143, MD ‐10.00 CI ‐11.35 to ‐8.65). Saren 2004 also reported data on the Social Avoidance and Distress Scale (SAD) at 12 months follow‐up (1 RCT, n = 143, MD ‐16.00 CI ‐17.04 to ‐14.96) and Huang 2005 reported data on the Scale of Social‐skills for Psychiatric Inpatients (SSPI) at six months follow‐up (1 RCT, n = 67, MD ‐6.06 CI ‐7.17 to ‐4.95). In addition, Ma 2003 reported data for general functioning on the Disability Assessment Scale (DAS) at 26 weeks follow‐up and also found a significant difference in favour of the social skills training group (1 RCT, n = 120, MD ‐6.8 CI ‐10.52 to ‐3.08).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 1 Social functioning: average endpoint score (various scales).

1.2 Relapse

Two studies reported on the number of participants relapsing, with follow‐up between six months and 12 months. A significant difference was found in favour of the social skills group (2 RCTs, n = 263, RR 0.52 CI 0.34 to 0.79; Analysis 1.2). The results showed moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 40%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 2 Relapse.

1.3 Global state: not clinically improved

Huang 2005 reported data for this outcome at six months follow‐up and found that significantly more participants showed a clinical improvement in global state in the social skills training group compared to the standard care group (1 RCT, n = 67, RR 0.29 CI 0.12 to 0.68; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 3 Global state: not clinically improved..

1.4 Service outcome: re‐hospitalisation

Saren 2004 reported data on re‐hospitalisation at 12 months follow‐up and showed a significant difference in favour of the social skills group (1 RCT, n = 143, RR 0.53 CI 0.30 to 0.93; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 4 Service outcome: rehospitalisation.

1.5 Mental state

1.5.1 Average endpoint score in negative and positive symptoms

Hayes 1995 and Ma 2003 measured negative symptoms on the SANS scale with eight and 18 weeks follow‐up, respectively, and found a significant difference in favour of the social skills training group (2 RCTs, n = 187, MD ‐8.92 CI ‐10.46 to ‐7.38). Ma 2003 also measured positive symptoms on the SAPS scale, and also found a significant difference favouring social skills training (1 RCT, n = 120, MD ‐1.90 CI ‐3.37 to ‐0.43; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 5 Mental state: average endpoint score.

1.5.2 Average change in general and negative symptoms

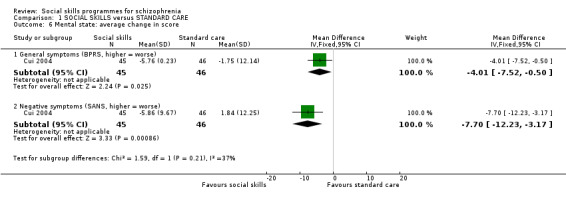

Cui 2004 reported the average change in mental state at 12 weeks follow‐up (Analysis 1.6). General symptoms were measured using the BPRS (1 RCT, n = 91, MD ‐4.01 CI ‐7.52 to ‐0.50) and negative symptoms were measured using the SANS (1 RCT, n = 91, MD ‐7.70, CI ‐12.33 to ‐3.17), both of which showed a significant improvement in symptoms in the social skills group compared with standard care.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 6 Mental state: average change in score.

1.6 General functioning: average endpoint score

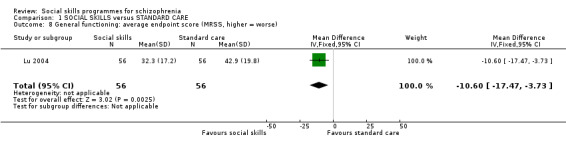

Lu 2004 reported data on the Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale (MRSS) at eight weeks follow‐up and found a significant difference in favour of the social skills training for the participants rehabilitation status (1 RCT, n = 112, MD ‐10.60 CI ‐17.47 to ‐3.73; (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 8 General functioning: average endpoint score (MRSS, higher = worse).

1.7 General functioning: employment

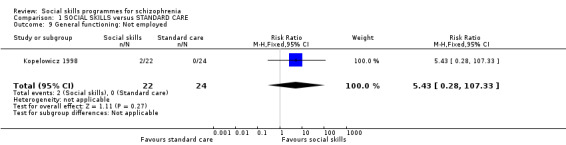

(Kopelowicz 1998) reported whether participants were employed at the end of the study and found no difference between treatment groups (n = 46, RR 5.43 CI 0.28 to 107.33) Analysis 1.9.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 9 General functioning: Not employed.

1.8 Leaving the study early

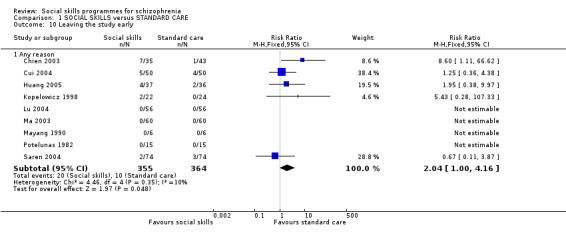

We found no significant differences between social skills training and standard care for the number of participants leaving the study early with follow‐up between eight weeks and 12 months (9 RCTs, n = 719, RR 2.04 CI 1.00 to 4.16; Analysis 1.10). In Kopelowicz 1998, two people in the social skills group dropped out because they had found employment, but despite this there was very low heterogeneity for these results (I2 = 10%).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 10 Leaving the study early.

1.9 Quality of Life: average endpoint score

Lu 2004 measured quality of life at 8 weeks follow‐up on two scales, the General Well‐Being scale (n = 112, MD ‐7.60 CI ‐12.18 to ‐3.02) and the Self‐Esteem scale (n = 112, MD ‐8.30 CI ‐10.07 to 6.53), both of which showed a significant difference in favour of the social skills training (Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 11 Quality of life: average endpoint score (various scales).

2. COMPARISON 2: SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL

2.1 Social functioning: average endpoint score

Two studies reported data for this outcome at six months follow‐up, each on two different scales, none of which showed a significant difference between social skills training and a discussion control (Analysis 2.1). Hayes 1995 measured social functioning on the Social situations questionnaire (SSQ) (n = 63, MD ‐1.10 CI ‐11.14 to 8.94) and the conversation with a stranger task (SCON) (n = 63, MD ‐2.50 CI ‐5.52 to 0.52). Ng 2006 used the Social Functioning Scale (SFS) (n = 36, MD 4.60 CI ‐7.54 to 16.74) and the Social behaviour schedule (SBS) (n = 36, MD 0.50 CI ‐‐2.56 to 3.56).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL, Outcome 1 Social functioning: average endpoint score (various scales).

2.2 Relapse

This outcome was reported by Ng 2006 at six months follow‐up and no significant difference was found between the treatment groups (1 RCT, n = 33, RR 2.12 CI 0.44 to 10.10; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL, Outcome 2 Relapse.

2.3 Global state: average endpoint score

Hayes 1995 reported data for global state on the Global Assessment Scale at six months follow‐up and found no significant difference between the social skills training and the discussion control (1 RCT, n = 63, MD 4.50 CI ‐1.20 to 10.20) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL, Outcome 3 Global state: average endpoint score (GAS, higher = better).

2.4 Mental state: average endpoint score

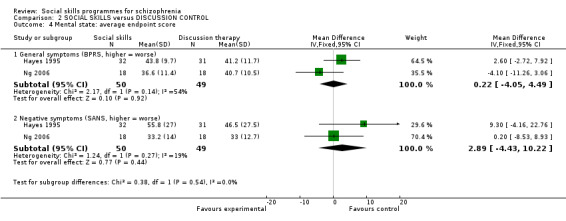

Two trials reported the average endpoint score for general symptoms at six months follow‐up on the BPRS scale and found no significant difference between the treatment groups (2 RCTs, n = 99, MD 0.22 CI ‐4.05 to 4.49; Analysis 2.4). The results showed high heterogeneity (I2 = 54%). In addition, the two trials also found no significant difference in negative symptoms on the SANS scale (2 RCTs, n = 99, MD 2.89 CI ‐4.43 to 10.22; Analysis 2.4). These results were moderately heterogeneous (I2 = 19%).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL, Outcome 4 Mental state: average endpoint score.

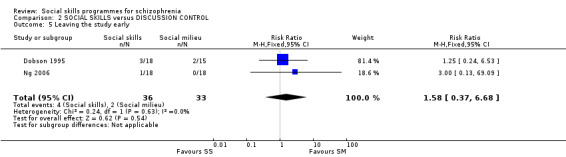

2.5 Leaving the study early

Two trials reported data for this outcome at three months and six months follow‐up and showed no significant difference between the social skills training and discussion control (2 RCTs, n = 69, RR 1.58 CI 0.37 to 6.68; (Analysis 2.5). The results showed no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL, Outcome 5 Leaving the study early.

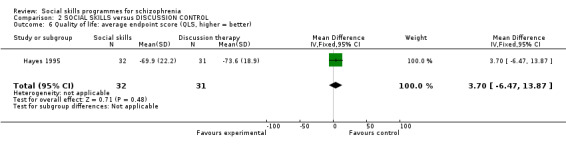

2.6 Quality of life

Hayes 1995 reported data on quality of life at six months follow‐up and found no significant difference between the treatment groups (Analysis 2.6). (1 RCT, n = 63, MD 3.70 CI ‐6.47 to 13.87).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL, Outcome 6 Quality of life: average endpoint score (QLS, higher = better).

3. Missing outcomes

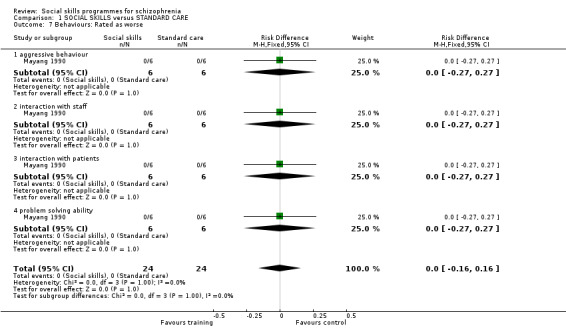

None of the studies evaluated general behaviour, engagement with services, satisfaction with treatment and economic outcomes.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The summary below reflects the outcomes chosen for the 'Summary of findings' tables chosen to be of clinical importance before seeing the data. These are considered to be the main findings of this review. For all outcomes, we judged the quality of evidence to be very low ‐ randomisation was not well described, observation bias was impossible to exclude and few attempts were made to minimise it, and outcomes were poorly reported.

1. COMPARISON 1: SOCIAL SKILLS versus STANDARD CARE

1.1 Social functioning

We found it surprising that ‐ for this comparison ‐ social functioning was just so poorly reported. The use of various scales made any potential analysis prone to problems from the very many assumptions that would have had to be made. Four studies reported on 585 people but different scales were used in each with little help for the reader in the interpretation of what outcomes would mean in everyday life.

1.2 Relapse/rehospitalisation

Two trials suggest (n = 263) that the risk of relapse is halved in between six and 12 months follow‐up. The low‐quality data are also moderately heterogeneous ‐ but this is an encouraging finding ‐ mirroring that of the risk of rehospitalisation. If only rehospitalisation had some suggestion of decrease and not relapse then it may have been argued that the putative increase in social skills would have helped avoid admission. However, this is not the case and there is a suggestion that the social skills programmes help offset the relapse as well. This finding, as others, need replicated in larger studies.

1.3 Mental state: general symptoms

Mental state outcomes were few and is it not clear that the social skills programmes have any effect.

1.4 Global state: not clinically improved.

The global state outcome, as measured by the CGI, was also favouring social skills programmes. This is in keeping with the relapse and rehospitalisation outcomes but is only based on one very small study (n = 67).

1.5 General functioning

One small study (n = 112) reported on general functioning. We have not been able to find explanation of what a 10‐point decline would mean in everyday life, but the decline did favour the social skills programme group.

1.6 Quality of life

Finally, the quality of life measure also favoured the social skills programme group in one study (n = 112).

1.7 Overall

The overall impression that we are left with is that social skills programmes, in the hands of expert and committed practitioners ‐ who these trialists were ‐ may have some valuable effects (please see Implications for research).

2. COMPARISON 2: SOCIAL SKILLS versus DISCUSSION CONTROL

As stated above, we thought that is would not be right to summate a social skills programme versus standard care comparison with that comparing the social skills programme to a more active discussion group control. However, data were more thin and inconclusive.

2.1 Social functioning

Two studies (total n = 63 people) reported on two different scales. There did not seem to be any difference between the social skills programme and the discussion group control.

2.2 Relapse

One tiny study (n = 35) reported on relapse with no differences between groups. Such outcomes should be reported as a matter of routine ‐ but it would seem likely that much larger studies are needed to highlight differences with any degree of meaningful confidence.

2.3 Global state, mental state. quality of life

In the one study of 63 people global state was unchanged. This applies to mental state (2 RCTs, n = 99) and quality of life 1 RCT, 63 people).

2.4 Overall

When social skills training was compared to this discussion control, no evidence was found to suggest that social skills training was superior to the control group for improving social functioning, employment, relapse rates, mental state, global state, quality of life and leaving the study early.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

1. Completeness

Even for outcomes for which we identified usable data, because all studies were of a small sample size (range 18 to 148) we feel that no outcomes could be labelled as complete. We did not find studies with any data for the following outcomes: general behaviour, engagement with services, satisfaction with treatment and economic outcomes.

2. Applicability