Abstract

The title reaction is theoretically investigated in detail using density functional theory. Three possible routes starting from keto- or enol-type vinylcyclopropylketone are considered in this work. Results indicate that phosphine catalyst would first attack at the three-membered ring (C3 position) rather than the terminal of alkene (C1 position) in vinylcyclopropylketone. It is found that the two-stage mechanism would be responsible for the title reaction. The first stage is the SN2-type ring-opening of the keto-type vinylcyclopropylketone with phosphine catalyst. After the proton-transfer tautomerisms in the zwitterionic intermediates, the second stage is associated with the 7-endo-trig SN2′-type ring closure of keto- or enol-type zwitterions to furnish seven-membered cyclic products and recover the catalyst. Moreover, it turns out that 7-endo-trig SN2′-type ring closure would be highly asynchronous and could be well described as an addition/elimination process where the ring closure already finishes before the cleavage of the C–P bond. Computational results provide a deep insight into experimental observations.

1. Introduction

Cycloalkanes bearing a small ring are ideal candidates for the organic synthesis, which benefits from the high strain-release energy associated with the cleavage of the covalent bond.1 As for these strained cyclic compounds, the cleavage of a three-membered ring would provide a significant driving force and has attracted more attention in the synthesis. Donor–acceptor cyclopropanes (DACs), one class of special three-membered cyclic compounds, have high reactivity due to the electronic effect.2 In the past decades, many elegant methodologies have been developed for the ring-opening of cyclopropanes,3 such as metal-catalyzed, Lewis acid-catalyzed, and radical-induced ring-opening strategies.

On the other hand, several advances have been made in phosphine-mediated reactions,4 such as Wittig, Mitsunobu, Staudinger, Appel, and so on. Phosphines could easily undergo a nucleophilic addition on the electron-deficient unsaturated compounds, leading to zwitterionic intermediates. Generally, phosphines participate in reactions through the formation of phosphonium salts from alkyl halides, phosphine dienolates from allenes, Kukhtin–Ramirez type adducts from 1,2-dicarbonyl compounds, Huisgen zwitterions from diazene derivatives, etc. Among these, the zwitterions generated from the nucleophilic addition of trivalent phosphines to allenes have been extensively investigated in synthetic applications for the formation of C–C and C–heteroatom bonds.

Combined with the merits of cyclopropane substrates and phosphine catalysts, Xu et al. hypothesized that it was possible to form a ring-opening zwitterionic intermediate by the addition of phosphines on to the electron-deficient vinylcyclopropanes (VCPs).5 The VCPs might have to be treated as synthetic equivalents of C5 units to generate medium-sized cyclic backbones. Due to the unique and varied reactivity, the VCPs have been extensively investigated in modern organic synthesis.6

As shown in Scheme 1, Xu and co-workers examined the reactivity of 1,1-diacetyl-2-vinylcyclopropane.5 Different from the formation of dihydrofuran via the Cloke–Wilson rearrangement by 1,4-diazabicyclooctane (DABCO) catalyst,7 an unexpected phosphine-catalyzed rearrangement of vinylcyclopropylketones to cycloheptenones was observed in the experiment. This novel phosphine-catalyzed ring expansion of vinylcyclopropylketones would be an alternative strategy for the construction of seven-membered ring backbones. Under the optimal condition of 20 mol % PBu3 catalyst at 110 °C in toluene, the yield of the product reaches 85%. With the aid of deuterated isotropic labeling, reactive intermediate trapping, and 31P NMR tracking, a catalytic cycle was proposed for the reaction mechanism. It mainly includes two processes. Process 1 is the homoconjugate addition of PBu3 on vinylcyclopropylketone to generate a zwitterion via the ring-opening; Process 2 is associated with 7-endo-trig SN2′ ring closure for the seven-membered cyclic product after the tautomerism of the zwitterionic intermediate by the proton shift.

Scheme 1. Reported Phosphine-Catalyzed Rearrangement of Vinylcyclopropylketone in the Experiment5.

Even so, some critical questions are hidden and need to be resolved. For example, which is the favored site of VCP for the nucleophilic attack by phosphine catalyst? What is the role of the phosphine catalyst? Which stage would be responsible for the proton transfer? In this work, our motivation is to make the mechanistic scenario clear using pure computations. Generally, besides the suggested pathways in the experiment, other possible pathways (Scheme 2) should be carefully designed and checked for comparison. Three possible routes are designed for the reaction in this work. Routes 1 and 2 are associated with the addition of phosphine at C3 and C1 positions of the keto-type reactant, respectively. After keto–enol tautomerism, route 3 corresponds to reaction pathways of the enol-type reactant. Note that the ring-closure steps in route 3 would be common for routes 1 and 2.

Scheme 2. Three Possible Routes for the Rearrangement of Vinylcyclopropylketone.

2. Computational Details

All of the relevant geometries were fully optimized using dispersion-included ωB97XD density functional theory (DFT) in conjunction with the self-consistent reaction field (SCRF) method.8 The standard 6-31+G(d,p) basis set was used in computations. After geometry optimization, harmonic vibrational analyses were performed at the same level to confirm that each minimum had no imaginary frequency or each transition state (TS) had only one imaginary frequency. The minimum energy path (MEP) was also traced using the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) method to ensure that each TS structure is correctly linked to two minima.9 The implicit C-PCM solvent model was adopted to evaluate the solvent effect on the reaction in toluene (ε = 2.374).10 To refine the energies, we, therefore, performed single-point energy calculations at the B2PLYP-D3/6-31+G(d,p) level.11 To match the experimental condition, the obtained thermal energies were corrected at 110 °C and 1 atm. Finally, the corresponding total energies of each species were obtained by the sum of single-point electronic energy (B2PLYP-D3) and thermal corrections of ωB97XD at 110 °C. Furthermore, some electronic structures were analyzed by the natural bond orbital (NBO) method.12 All computations were fulfilled with Gaussian 09 program.13 All three-dimensional (3-D) structures were generated by CYLview program.14

For practical reasons, it is common in quantum mechanics (QM) and statistic mechanics computations to estimate entropy using the ideal gas model. However, the translational and rotational motions would be suppressed in solution, reducing the entropy as compared to the gas phase. Especially, for a bimolecular reaction in solution, the relative entropy would be overestimated in computations if the uncorrected total gas-phase entropy of separated molecules is taken as the reference. Therefore, some methods were suggested to estimate the entropy in solution.15a For example, discarding translational and/or rotational entropy, scaling methods, and so on. Yu et al. reported that the experimental activation entropy would be 50–60% of the computational entropy in the attacking step of phosphine in electron-deficient alkenes.15b Deubel et al. proposed to simply use a correction factor (0.5) for the entropy contribution on the free energy (ΔGcorrected = ΔHsol + (1/2)TΔSgas).15c The Trouton’s rule states that the entropy of vaporization is almost the same (ca. 20–21 cal/(K mol)) for various kinds of liquids. In this work, we found that, if the scaling factor of 0.5 was used in the attacking step (see details in the Supporting Information and Section 3), the relative entropy would be reduced by 19 cal/(K mol), close to the Trouton’s rule. So, an average value, i.e., 20 cal/(K mol), was directly subtracted from the computational entropies in the calculation of the relative free energies. Note that this correction method only influences the bimolecular reaction step (e.g., phosphine-attacking step).

3. Results and Discussion

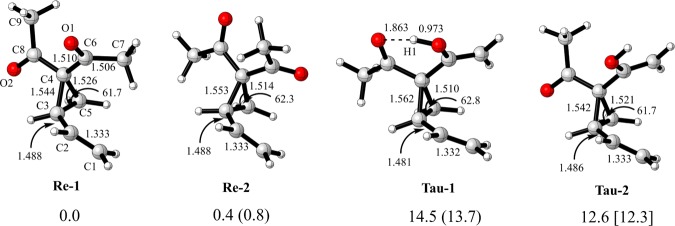

As shown in Figure 1, two types (keto and enol) of precursors possibly exist in the reaction via keto–enol tautomerism. Accordingly, four conformers were considered in our computations. Energies of two reactants Re-1 and Re-2 are very close. The energy difference is about 1.4 kcal/mol between their enol tautomers (Tau-1 and Tau-2). However, the energies of enol tautomers are about 13 kcal/mol higher than those of keto reactants, indicating that the major population would be keto structures in the reaction. Starting from the keto or enol conformers, some possible channels are shown in Scheme 2.

Figure 1.

Geometries (bond length in Å) of reactants and tautomers along with relative energies (in parenthesis) and Gibbs free energies (kcal/mol).

Vinylcyclopropanes (VCPs), including a double bond installed at cyclopropane, would be more active for ring-opening because of π–σ* or σ–π* conjugation. NBO results indicate that the second-order stabilization energy (E2) is 6.58 kcal/mol for the interaction of π(C1=C2) → σ*(C3–C4) in Re-1. In Tau-1, E2 energies of π(C1=C2) → σ*(C3–C4), π(C6=C7) → σ*(C3–C4), and σ(C3–C4) → π*(C8=O2) are 7.86, 5.68, and 11.45 kcal/mol, rendering the C3–C4 bond longer (1.562 Å) and weaker. As shown in Table S1 in the Supporting Information, the Wiberg bond order of the C2–C3 bond is 0.879 and 0.858 in Re-1 and Tau-1, respectively. After comparing the C1 and C3 positions (see details in the following section), it would be more favorable for the phosphine catalyst to attack the three-membered ring (C3 position) than the terminal of alkene (C1 position). In this article, we mainly report the reaction processes where the C3 position is attacked by phosphine catalyst.

3.1. Process Starting from Keto Structures (Route 1)

Figure 2 shows the relative energies along with the reaction process, and the corresponding geometries are depicted in Figure S1 (see the Supporting Information). Although we optimized a weak complex CM-1 on the PBu3-catalyzed pathway from Re-1 to TS-1, the binding energy is only 2.21 kcal/mol after being corrected by the basis set superposition error (0.66 kcal/mol). On the other hand, the uncorrected and corrected relative entropies are −32.3 and −12.3 cal/(mol K), contributing 12.4 and 4.7 kcal/mol to the −TΔS term of the relative free energy, respectively. In this sense, the complex CM-1 would be unstable (ΔG > 0).

Figure 2.

Relative energies (in parenthesis) and Gibbs free energies (kcal/mol) for the reaction processes of route 1.

Starting from Re-1 or Re-2, SN2-type transition states TS-1 or TS-1′ toward ring-opening were optimized. Except for the orientation of acetyl groups, the two transition states are very similar. The C3–C4 bond distances are 2.132 and 2.060 Å; the C3–P bond distances are 2.552 and 2.557 Å. Both vibrational modes of imaginary frequencies are mainly associated with the coupling of the C3–C4 and C3–P bond stretches. The Wiberg bond order of the C3–C4 bond in TS-1 is 0.266, which is 0.61 less than that in the reactant RE-1. However, the Wiberg bond order of the C3–P bond increases to 0.37 in TS-1. The result of IRC tracking is shown in Figure 3. Although the decrease in the C3–P bond distance occurs simultaneously with the increase of the C3–C4 bond distance, the ring-opening step would be an asynchronous SN2-type nucleophilic attack in the view of the evolution of the bond order. Namely, the cleavage of the C3–C4 bond toward ring-opening would be prior to the formation of the C3–P bond. This scenario is also found in the DABCO-catalyzed reaction and would be wrongly suggested to be a SN1 reaction in the experiment.7,16 Then, zwitterionic intermediates Int-1 and Int-1′ are formed in the reaction. Due to the conjugation and delocalization, the formal negative charge center (C4) is stabilized by the effect of the electron-withdrawing acetyl groups.

Figure 3.

IRC profiles along with evolutions of the C–C and C–P bond distance (Å) for TS-1 (A) and TS-2 (B).

It is found that the ΔG‡ of TS-1 and TS-1′ are 20.4 and 21.6 kcal/mol from Re-1 with the corrected entropy contributions (see Tables S2 and S3 in the Supporting Information). In other words, the two transition states would have an almost equal chance to occur in the reaction.

Next, the proton transfer would occur from methyl to C4 atom (see Int-2 in Figure 2) or O1 atom (see Int-3 or Int-3′ in Figure 4). Accurately computing the barrier of the proton transfer is an open question. To directly calculate the process of the proton transfer without the assistance of water (or a proton shuttle), the energy barrier should be dramatically high (>50 kcal/mol) for the 1,3-proton transfer because of the strain energy of the four-membered cyclic transition state.17 To narrow the energy barrier, it usually builds a bridge (such as water) to facilitate the proton transfer. Water can act as a proton shuttle and microsolvent. In this way, it should be reasonably considered how to arrange water molecules to help the proton transfer in the computation. Encouraged by our previous work,18 the water cluster including twelve explicit water molecules was tested for the proton transfer.19 Two water molecules build a bridge on the demand of the proton transfer and others are considered as microsolvent environment to stabilize the water bridge. It is found that the proton, transferred from the water solvent, would be very easy to add at the C4 atom, generating the “virtual existence” of a hydration hydroxide ion (see Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). Unfortunately, all attempts to locate the corresponding transition state of proton transfer failed. Simply put, we only keep the two waters as a bridge for the proton transfer and the corresponding transition states and relative energies were successfully obtained for the tautomerism from Int-1′ to Int-2 with the help of water (see Figure S3 in the Supporting Information). It turns out that this proton transfer would overcome the 23.8 kcal/mol barrier. The subtraction of α-H from C7 is slower than the addition of a proton onto C4. To our delight, stabilized by two water molecules, the relative free energy from Int-1′ to Int-2 decreases by about 7 kcal/mol (18.6 vs 11.6 kcal/mol). We imagine that ΔG‡ or ΔG would decrease more if more water molecules (water cluster) are considered in the proton transfer. Anyway, we believe that this proton transfer would be favorable and has a strong ability to compete against other reaction pathways if trace water exists in the reaction.

Figure 4.

Relative energies (in parenthesis) and Gibbs free energies (kcal/mol) for the reaction processes in channel 2 of route 3.

Then, the transition state SN2′-type 7-endo-trig TS-2, associated with constructing the C1–C7 bond to furnish the seven-membered cyclic product, was also successfully obtained. In TS-2, the bond distance of C1–C7 is 1.984 Å and the vibrational mode of imaginary frequency almost corresponds to the C1–C7 bond stretch. Both the IRC result (Figure 3) and the vibrational mode of imaginary frequency confirm that this 7-endo-trig ring closure would be strongly asynchronous because the C1–C7 bond is formed much before the cleavage of the C3–P bond. Interestingly, a plateau occurs in the IRC profile after the formation of the C1–C7 bond. It is found that the formal negative center moves from C7 to C2 in the plateau region and that the hybridization of C2 changes from sp2 to sp3. Therefore, the 7-endo-trig SN2′ would be well described as an addition/elimination stepwise process. Namely, followed by the nucleophilic addition of alkene with α carbanion to form the C1–C7 bond, it would undergo the elimination of PBu3 through an E1cb-like mechanism.

Although ΔG‡ in this elementary step is 26.0 kcal/mol from Int-2, the total ΔG‡ reaches 41.1 kcal/mol including the proton transfer from Int-1′ to TS-2 in this rate-limiting step. As stated above, this barrier would be significantly reduced by the assistance of water.

Likewise, the Cloke–Wilson rearrangement was also comparatively studied in this work (channel 3 of route 1).6 Starting from Int-1′, the transition state TS-3 is associated with the C3–O bond formation toward dihydrofuran. Distances of the C3–O and C3–P bonds are 2.048 and 2.472 Å, respectively. This transition state is also asynchronous with the confirmation that the C3–O bond is formed earlier than the cleavage of the C3–P bond. The corresponding ΔG‡ is 26.6 kcal/mol from Int-1′. In this sense, the Cloke–Wilson rearrangement (TS-3) would be somewhat fast or strongly compete with 7-endo-trig ring closure (TS-2) from Int-1′. Note that the energy of Pr-3 is close to that of Int-1′, indicating that the formation of dihydrofuran would be a resting state in the reaction.

By the way, the rearrangement of vinylcyclopropane to cyclopentene (VCP–CP) (channel 4 of route 1) was also checked.3c The results exhibit that it would be difficult to undergo this transformation via a 5-endo-trig SN2′-type ring closure process, which coincides with no detection of cyclopentene in the experiment. This disadvantage of transformation would be explained by Baldwin’s rules.

3.2. Process Starting from Enol Structures (Channel 2 of Route 3)

Starting from Tau-1 and Tau-2 as shown in Figure 1, the transition states TS-4 and TS-4′ associated with PBu3 attacking cyclobutene (C3 position) were optimized (Figure 4). The relevant geometries are depicted in Figure S4 (see the Supporting Information). The C3–C4 bond distance is almost equal (2.182 Å) in TS-4 and TS-4′, whereas the C3–P bond distances are 2.498 and 2.333 Å, respectively. In TS-4, due to the coplanar character, more orbital interaction and hydrogen bonding lead to more conjugation of the two electron withdrawing groups (EWG) with a negative C4 center. The corresponding ΔG‡ is 22.4 and 27.8 kcal/mol, respectively. If the keto–enol tautomerism is included, this attacking mode would be difficult to achieve in the reaction (ΔG‡ would be 36.9 and 40.4 kcal/mol for TS-4 and TS-4′, respectively).

Then, it offers intermediates Int-3 and Int-3′. Note that although they would not be generated by direct ring-opening of enol structures by phosphine catalyst, they could be alternatively transformed from keto-type intermediates Int-1, Int-1′, or Int-2. We think that this transformation would also be likely with the help of water.

Next, 7-endo-trig transition states TS-5 and TS-5′ were also optimized in the formation of seven-membered cyclic products. Both the IRC result and the vibrational mode obviously indicate that the 7-endo-trig process of enol type is very similar to that of the keto type. Namely, it is also an addition/elimination sequential process.

Similarly, although ΔG‡ of the elementary step is 18.6 kcal/mol, the total ΔG‡ reaches 41.6 kcal/mol, including the proton transfer in this rate-limiting step from Int-1′ to TS-5. Because of the almost equal barriers (41.1 vs 41.6 kcal/mol), we cannot rule out one between the keto-type TS-2 and the enol-type TS-5.

In all, by gathering the available information, the suggested reaction scenario is concisely depicted in Figure 5. The first stage is the SN2-type ring-opening of the keto-type reactant with the phosphine catalyst. After the proton-transfer tautomerisms of the zwitterionic intermediates, the second stage is associated with the 7-endo-trig SN2′-type asynchronous ring closure of enol or keto zwitterions to afford seven-membered ring products and recover the catalyst. Additionally, the resting state (dihydrofuran) would exist in the reaction. Importantly, after the proton shift, the nonconjugate in Int-2 and the hydrogen bond in Int-3 would retard the Cloke–Wilson rearrangement (TS-3) to generate the resting state. As shown in Figure 4, enol-type product (Pr-2) is slightly stable than the keto-type product (Pr-1) by about 2 kcal/mol, supporting the observation of 85% experimental yield of enol product in the reaction.5

Figure 5.

Catalyzed mechanism for the title reaction along with relative energies (in parenthesis) and Gibbs free energies (kcal/mol) in key steps. Underlined values are the total activation barriers that include the relative energies (free energies) of the proton-transfer tautomerisms.

3.3. Uncatalyzed Process via [3,3]-σ Rearrangement (Channel 1 of Route 3)

To clarify the role of catalyst, the uncatalyzed process via [3,3]-σ rearrangement was also considered as a comparative study. Optimized geometries are depicted in Figure S5 (see the Supporting Information). Figure 6 shows that the values of total ΔG‡ are 28.5 and 31.8 kcal/mol for TS-6 and TS-7 from Re-1, respectively. Compared with the above-mentioned PBu3-catalyzed processes, the uncatalyzed processes might be somewhat competitive. Why it does not work without the catalyst in the experiment? We think that it would be favorable for the PBu3-catalyzed ring-opening of the keto-type reactant to generate a zwitterionic intermediate in the first reaction stage and that the barrier of the water-assisted proton transfer would reduce more if more water molecules are considered. For example, after considering only two water molecules, as discussed above, ΔG‡ reduces from 41 to 34 kcal/mol in the rate-limiting step from Int-1′ to TS-2. The detailed proton-transfer processes, including more accurate computational model and method, are being performed by our group and will be reported separately in the future.

Figure 6.

Relative energies (in parenthesis) and Gibbs free energies (kcal/mol) for the uncatalyzed reaction processes in channel 1 of route 3.

3.4. Possible Pathways via the Addition at C1 Position by PBu3 (Route 2 and Channel 3 of Route 3)

As shown in Figures 7 and 8, both keto- and enol-type precursors are taken as the starting geometries. Optimized geometries are depicted in Figures S6 and S7 (see the Supporting Information). The corresponding processes also include two stages: SN2′-type nucleophilic addition for the ring-opening of vinylcyclopropylketone and SN2-type 7-endo-trig ring closure of the seven-membered cyclic product. However, compared with the attack at the C3 position, ΔG‡ of the C1 site addition is higher to some extent. In this sense, the ring-opening vinylcyclopropylketone at C1 position using the steric free catalyst would be unlikely.

Figure 7.

Relative energies (in parenthesis) and Gibbs free energies (kcal/mol) for the reaction processes in route 2.

Figure 8.

Relative energies (in parenthesis) and Gibbs free energies (kcal/mol) for the reaction processes in channel 3 of route 3.

To make clear the difference in the reactivities between C1 and C3 positions, the ring-opening process was scanned along with the C3–C5–C4 angle expansion starting from the reactant. Figure 9 and Table S4 in the Supporting Information show that the relative natural charges at C1 and C3 atoms gradually become more positive in the ring-opening process. The C3 atom loses electron more rapidly than the C1 atom, rendering the C3 atom more active for the nucleophilic attack of PBu3. Additionally, the complexation energy was obtained by the counterpoise method at the ωB97XD/6-31+G(d,p) level. The activation barrier is decomposed into ΔEstrain and ΔEint, where ΔEstrain is associated with the deformation energy from free reactants (including the catalyst) to their geometries in the transition state, and ΔEint is the interaction energy between the deformed moieties. It indicates that ΔEint of PBu3 with the C3 atom in TS-1 (−7.9 kcal/mol) is lower than that with C1 atom in TS-8 (−2.7 kcal/mol). ΔEstrain of the reactant in TS-1 and TS-8 are very close (27.3 vs 26.9 kcal/mol), whereas ΔEstrain of PBu3 catalyst is small (0.7 vs 1.4 kcal/mol). Therefore, the strong electron deficiency and high interaction energy would be responsible for the high reactivity of the C3 position in the nucleophilic attack of PBu3.

Figure 9.

Relative charges at C1 and C3 atoms along with the ring-opening process (Δq is relative to the reactant).

3.5. Other Possibilities Related with Phosphine Catalyst Acting as a Base or an Oxygenphile

Phosphine could act as a nucleophile or an oxygenphile. The possibility of the direct attack at C=O of the acetyl group in the keto-type reactant was also examined. The corresponding structure is unstable, and the zwitterion could not be successfully located via the formation of the C–P bond (see structure A in Figure 10). For other possible structures, the results show that the relative energies are somewhat high or that they need the formation of the enol-type reactant first. By the way, if the α carbanion was generated with the α-H abstraction by PBu3, the [3,3]-σ rearrangement would overcome the 16.9 kcal/mol barrier, which is very close to that of the neutral enol-type transition state TS-7. We think because the yield of the product did not increase with the amine catalyst in the experiment, the α-H abstraction would not occur due to the weak basicity of PBu3. Anyway, these possibilities are safely ruled out in this work.

Figure 10.

Other zwitterionic intermediates along with relative energies (in parenthesis) and Gibbs free energies (kcal/mol).

4. Conclusions

In this work, the detailed pathways of the title reaction were theoretically explored using density functional theory. Both keto- and enol-type reaction precursors were considered in computations. Main findings are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

The keto-type reactant and its ring-opening zwitterionic intermediates are more stable than their enol-type counterparts.

-

(2)

It would be more favorable for the phosphine catalyst to attack the three-membered ring (C3 position) than the terminal of alkene (C1 position) in vinylcyclopropylketone.

-

(3)

A two-stage mechanism was responsible for the title reaction. The first stage is the SN2-type ring-opening of the keto-type reactant with phosphine catalyst. After the proton-transfer tautomerisms of the zwitterionic intermediates, the second stage is associated with the asynchronous 7-endo-trig SN2′-type ring closure of keto- or enol-type zwitterion to afford seven-membered cyclic products and recovery of the catalyst.

-

(4)

The 7-endo-trig SN2′-type ring closure would be well described as an addition/elimination sequential process where the C1–C7 bond formation is much before the cleavage of the C3–P bond.

-

(5)

Water-assisted proton-transfer tautomerisms between zwitterionic intermediates are very crucial. The water-assisted tautomerisms not only accelerate the reaction rate but also suppress the Cloke–Wilson rearrangement toward the resting state.

Although proton-shift processes are insufficient, computational results provide a rational mechanistic scenario and enhance the comprehension of the experimental observation.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21573172, 21773181, 21503157, and 21503159). L.J. thanks the Research Foundation for Advanced Talents in Xinjiang Province and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21762043). Y.W. thanks the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University (No. xjj2015064). We thank Dr. Silong Xu for comments and suggestions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b03902.

Optimized structures (bond length in Å) in route 1; optimized structures (bond length in Å) in channel 2 of route 3; Wiberg bond index; cartesian coordinates (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Fumagalli G.; Stanton S.; Bower J. F. Recent Methodologies That Exploit C–C Single-Bond Cleavage of Strained Ring Systems by Transition Metal Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9404–9432. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Schneider T. F.; Kaschel J.; Werz D. B. A New Golden Age for Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5504–5523. 10.1002/anie.201309886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cavitt M. A.; Phun L. H.; France S. Intramolecular Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropane Ring-Opening Cyclizations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 804–818. 10.1039/C3CS60238A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Petzold M.; Jones P. G.; Werz D. B. (3+3)-Annulation of Carbonyl Ylides with Donor-Acceptor Cyclopropanes: Synergistic Dirhodium(II) and Lewis Acid Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6225–6229. 10.1002/anie.201814409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Varshnaya R. K.; Banerjee P. Lewis Acid-Catalyzed [3 + 3] Annulation of Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes and Indonyl Alcohols: One Step Synthesis of Substituted Carbazoles with Promising Photophysical Properties. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 1614–1623. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ivanova O. A.; Andronov V. A.; Vasin V. S.; Shumsky A. N.; Rybakov V. B.; Voskressensky L. G.; Trushkov I. V. Expanding the Reactivity of Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes: Synthesis of Benzannulated Five-Membered Heterocycles via Intramolecular Attack of a Pendant Nucleophilic Group. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 7947–7952. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Xiao J. A.; Cheng X. L.; Li Y. C.; He Y. M.; Li J. L.; Liu Z. P.; Xia P. J.; Su W.; Yang H. Palladium-Catalysed Ring-Opening [3+2]-Annulation of Spirovinyl Cyclopropyl Oxindole to Diastereoselectively Access Spirooxindoles. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 103–107. 10.1039/C8OB02859A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Halskov K. S.; Næsborg L.; Tur F.; Jørgensen K. A. Asymmetric [3+2] Cycloaddition of Vinylcyclopropanes and α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes by Synergistic Palladium and Organocatalysis. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 2220–2223. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Liu Y.; Wang Q. L.; Chen Z.; Zhou C. S.; Xiong B. Q.; Zhang P. L.; Yang C. A.; Zhou Q. Oxidative Radical Ring-Opening/Cyclization of Cyclopropane Derivatives. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 256–278. 10.3762/bjoc.15.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Zotova M. A.; Novikov R. A.; Shulishov E. V.; Tomilov Y. V. GaCl3-Mediated “Inverted” Formal [3 + 2]-Cycloaddition of Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes to Allylic Systems. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 8193–8207. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b00959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Xie M. S.; Zhao G. F.; Qin T.; Suo Y. B.; Qu G. R.; Guo H. M. Thiourea Participation in [3+2] Cycloaddition with Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes: a Domino Process to 2-Amino-dihydrothiophenes. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 1580–1583. 10.1039/C8CC09595G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Dieskau A. P.; Holzwarth M. S.; Plietke B. Fe-Catalyzed Allylic C–C-Bond Activation: Vinylcyclopropanes As Versatile a1,a3,d5-Synthons in Traceless Allylic Substitutions and [3+2]-Cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5048–5051. 10.1021/ja300294a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Matsumoto Y.; Nakatake D.; Yazaki R.; Ohshima T. An Expeditious Route to trans-Configured Tetrahydrothiophenes Enabled by Fe(OTf)3-Catalyzed [3 + 2] Cycloaddition of Donor–Acceptor Cyclopropanes with Thionoesters. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6062–6066. 10.1002/chem.201800957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Hashimoto T.; Kawamata Y.; Maruok K. An Organic Thiyl Radical Catalyst for Enantioselective Cyclization. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 702–705. 10.1038/nchem.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Karanam P.; Reddy G. M.; Koppolu S. R.; Lin W. Recent Topics of Phosphine-Mediated Reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 59–76. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.11.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ye L. W.; Zhou J.; Tang Y. Phosphine-Triggered Synthesis of Functionalized Cyclic Compounds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1140–1152. 10.1039/b717758e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Swamy K. C. K.; Kumar N. N. B.; Balaraman E.; Kumar K. V. P. P. Mitsunobu and Related Reactions: Advances and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2551–2651. 10.1021/cr800278z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Nair V.; Menon R. S.; Sreekanth A. R.; Abhilash N.; Biju A. T. Engaging Zwitterions in Carbon–Carbon and Carbon–Nitrogen Bond-Forming Reactions: A Promising Synthetic Strategy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006, 39, 520–530. 10.1021/ar0502026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Guo H.; Fan Y. C.; Sun Z.; Wu Y.; Kwon O. Phosphine Organocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 10049–10293. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Tang Y. H.; Wei W.; Wu Y.; Li Y.; Zhang J. J.; Zheng Y. S.; Xu S. L. Phosphine-Catalyzed Activation of Vinylcyclopropanes: Rearrangement of Vinylcyclopropylketones to Cycloheptenones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 6284–6288. 10.1002/anie.201800555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Meazza M.; Guo H.; Rios R. Synthetic Applications of Vinyl Cyclopropane Opening. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 2479–2490. 10.1039/C6OB02647H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ganesh V.; Chandrasekaran S. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Reactivity of Vinylcyclopropanes. Synthesis 2016, 48, 4347–4380. 10.1055/s-0035-1562530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Jiao L.; Yu Z. X. Vinylcyclopropane Derivatives in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Cycloadditions for the Synthesis of Carbocyclic Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 6842–6848. 10.1021/jo400609w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Tang Y. H.; Wei W.; Wu Y.; Li Y.; Zhang J. J.; Zheng Y. S.; Xu S. L. Organocatalytic Cloke–Wilson Rearrangement: DABCO-Catalyzed Ring Expansion of Cyclopropyl Ketones to 2,3-Dihydrofurans. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 3043–3046. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chai J. D.; Head-Gordon M. Long-Range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals with Damped Atom–Atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. 10.1039/b810189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Different density functional theory (DFT) methods, B3LYP(D3), cam-B3LYP(D3), M06(D3), M06-2×(D3), PBE0(D3), LC-ωPBE, and ωB97XD, were tested for a rate-limiting transition state TS-2 (see Table S5 in the supporting information and the section of results). It turns out the barriers of ωB97XD are very close to those of B3LYP(D3), M06-2×(D3), and LC-ωPBE. The barriers of cam-B3LYP(D3) are slightly overestimated, whereas the barriers of PBE0(D3) and M06(D3) are underestimated to some extent. Therefore, it would be suitable to use ωB97XD in this work.

- Fukui K. The Path of Chemical Reactions - the IRC Approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 1981, 14, 363–368. 10.1021/ar00072a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Barone V.; Cossi M. Quantum Calculation of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. 10.1021/jp9716997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cossi M.; Rega N.; Scalmani G.; Barone V. Energies, Structures, and Electronic Properties of Molecules in Solution with the C-PCM Solvation Model. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 669–681. 10.1002/jcc.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Grimme S. Semiempirical Hybrid Density Functional with Perturbative Second-Order Correlation. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 034108 10.1063/1.2148954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Schwabe T.; Grimme S. Double-Hybrid Density Functionals with Long-Range Dispersion Corrections: Higher Accuracy and Extended Applicability. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 3397–3406. 10.1039/b704725h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. E.; Curtiss L. A.; Weinhold F. Intermolecular Interactions from a Natural Bond Orbital, Donor-Acceptor Viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. 10.1021/cr00088a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian H. P.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam M. J.; Klene M.; Knox J. E.; Cross J. B.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Stratmann R. E.; Yazyev O.; Austin A. J.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Voth G. A.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Daniels A. D.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Ortiz J. V.; Cioslowski J.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 09, revision C.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Legault C. Y.CYLview, 1.0b; Universite′de Sherbrooke: Quebec, Canada. http://www.cylview.org, 2009.

- a Besora M.; Vidossich P.; Lledos A.; Ujaque G.; Maseras F. Calculation of Reaction Free Energies in Solution: A Comparison of Current Approaches. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 1392–1399. 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b11580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liang Y.; Liu S.; Xia Y. Z.; Li Y. H.; Yu Z. X. Mechanism, Regioselectivity, and the Kinetics of Phosphine-Catalyzed [3 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions of Allenoates and Electron-Deficient Alkenes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2008, 14, 4361–4373. 10.1002/chem.200701725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Deubel D. V. Mechanism and Control of Rare Tautomer Trapping at a Metal–Metal Bond: Adenine Binding to Dirhodium Antitumor Agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 665–675. 10.1021/ja076603t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q. Q.; Wang Y.; Wei D. H. Theoretical Study on DABCO-Catalyzed Ring Expansion of Cyketone: Mechanism, Chemoselectivity, and Role of Catalyst. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2018, 1123, 20–25. 10.1016/j.comptc.2017.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calculated ΔG‡ are 68.0 and 52.4 kcal/mol for the keto-enol tautomerism of the reactant and the zwitterionic intermediate (direct proton transfer from C7 to O2). Calculated ΔG‡ is 64.0 kcal/mol for the direct proton transfer from C7 to C4 in the zwitterionic intermediate.

- a Wu Y.; Jin L.; Xue Y.; Xie D. Q.; Kim C. K.; Guo Y.; Yan G. S. Theoretical Study on the Hydrolysis Mechanism of N,N-dimethyl-N′-(2-oxo-1, 2-dihydro-pyrimidinyl) Formamidine: Water-Assisted Mechanism and Cluster-Continuum Model. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1222–1232. 10.1002/jcc.20883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wu Y.; Xue Y.; Xie D. Q.; Kim C. K.; Yan G. S. Theoretical Studies on the Hydrolysis Mechanism of N-(2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-pyrimidinyl) Formamide. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 2357–2364. 10.1021/jp064510c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jin L.; Wu Y.; Zhao X. Theoretical Insight into the Au(I)-Catalyzed Hydration of Halo-Substituted Propargyl Acetate: Dynamic Water-Assisted Mechanism. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 89836–89846. 10.1039/C6RA13897G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Initial geometry of the water cluster is modified from the web. http://www1.lsbu.ac.uk/water/clusters_overview.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.