Abstract

Fishborne heterophyid trematodes infecting humans are at least 29 species worldwide and belong to 13 genera. Its global burden is much more than 7 million infected people. They include Metagonimus (M. yokogawai, M. takahashii, M. miyatai, M. minutus, and M. katsuradai), Heterophyes (H. heterophyes, H. nocens, H. dispar, and H. aequalis), Haplorchis (H. taichui, H. pumilio, H. yokogawai, and H. vanissimus), Pygidiopsis (P. summa and P. genata), Heterophyopsis (H. continua), Stellantchasmus (S. falcatus), Centrocestus (C. formosanus, C. armatus, C. cuspidatus, and C. kurokawai), Stictodora (S. fuscata and S. lari), Procerovum (P. varium and P. calderoni), Acanthotrema (A. felis), Apophallus (A. donicus), Ascocotyle (A. longa), and Cryptocotyle (C. lingua). Human infections are scattered around the world but the major endemic areas are located in Southeast Asia. The source of human infection is ingestion of raw or improperly cooked fish. The pathogenicity, host-parasite relationships, and clinical manifestations in each species infection are poorly understood; these should be elucidated particularly in immunocompromised hosts. Problems exist in the differential diagnosis of these parasitic infections because of close morphological similarity of eggs in feces and unavailability of alternative methods such as serology. Molecular diagnostic techniques are promising but they are still at an infant stage. Praziquantel has been proved to be highly effective against most of the patients infected with heterophyid flukes. Epidemiological surveys and detection of human infections are required for better understanding of the geographical distribution and global burden of each heterophyid species. In this review, the most updated knowledge on the morphology, biology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and pathology, immunology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment, and prevention and control of fishborne zoonotic heterophyid infections is provided.

Keywords: Fishborne trematode, Zoonotic trematode, Heterophyid, Metagonimus, Heterophyes, Haplorchis

Highlights

-

•

Fishborne intestinal flukes are diverse and heterophyids are an important group.

-

•

Thirteen heterophyid genera and 29 species are known to infect humans.

-

•

Metagonimus, Heterophyes, and Haplorchis are the most important genera.

-

•

Infections are significant due to the potential for morbidity and mortality.

-

•

Epidemiological surveys and detection of human infections are urgently required.

1. Introduction

Foodborne zoonotic trematodes are highly diverse in terms of the species of parasites involved and the kinds and types of foods concerned. They can be largely divided into liver flukes, lung flukes, and intestinal flukes (Fürst et al., 2012, Chai, 2014a). The global burden of foodborne trematodes was estimated at about 50–60 million people (Fried et al., 2004, Fürst et al., 2012). However, this certainly is a far underestimate of the true number of infected people because of difficulty in case detection and diagnosis (Chai et al., 2009a).

Among them, intestinal flukes are the most neglected group despite a wide geographical distribution, a high prevalence in some endemic countries, and potentially significant morbidity and mortality. Intestinal trematodes are taxonomically diverse, and consist of more than 60 species worldwide (Chai et al., 2009a). They include heterophyids (including Metagonimus yokogawai, Heterophyes nocens, and Haplorchis taichui), echinostomes (including Echinostoma revolutum, Echinostoma ilocanum, Echinochasmus japonicus, Artyfechinostomum malayanum, and Acanthoparyphium tyosenense), fasciolids (Fasciolopsis buski), gymnophallids (Gymnophalloides seoi), microphallids (Gynaecotyla squatarolae), neodiplostomes/diplostomes/strigeids (Neodiplostomum seoulense), lecithodendriids (Prosthodendrium molenkampi and Phaneropsolus bonnei), and plagiorchiids (Plagiorchis muris) (Chai, 2007, Chai, 2014a, Chai et al., 2009a). Among them, the heterophyids have seldom been the subject of extensive reviews. Thus, in this article, the authors would like to review on the heterophyid group of intestinal flukes.

Heterophyids (= family Heterophyidae Leiper, 1909) are a group of minute-sized (1–2 mm in length) trematodes infecting vertebrate animals, including mammals and birds (Yamaguti, 1958). At least 36 genera are known within this family (Pearson, 2008), and among them, 13 genera are known to be zoonotic (Chai, 2007); Metagonimus, Heterophyes, Haplorchis, Pygidiopsis, Heterophyopsis, Stellantchasmus, Centrocestus, Stictodora, Procerovum, Acanthotrema, Apophallus, Ascocotyle, and Cryptocotyle. They are exclusively fishborne and contracted to humans by ingesting raw or improperly cooked freshwater or brackish water fish (Chai, 2007, Chai, 2014a) (Fig. 1). Most of the infected people live in Asian countries, including Korea, China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and India.

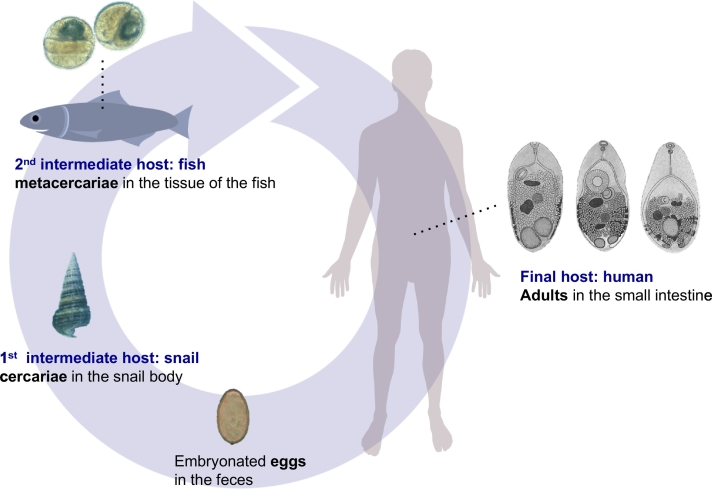

Fig. 1.

Common life cycle of fishborne zoonotic heterophyid trematodes. Human infection occurs when the infected fish are consumed raw or under improperly cooked conditions. Some images were adapted from Google.

In view of the wide geographical distribution and the number of infected people around the world, Metagonimus, Heterophyes, and Haplorchis are the three most important genera (Chai, 2015). Metagonimus morphologically differs from Heterophyes and Heterophyopsis in that the former has a smaller, submedian-located ventral sucker and no genital sucker, whereas the latter two have a bigger and almost median-located ventral sucker and a prominent genital sucker (Chai, 2007, Yu and Chai, 2010, Yu and Chai, 2013). Heterophyopsis has an elongated body unlike Heterophyes (Chai, 2007). Metagonimus has two testes but Haplorchis and Procerovum have only one testis (Chai, 2015). Haplorchis, Procerovum, and Stictodora have prominent gonotyls armed with several to numerous rodlets, superimposed on the submedially located ventral sucker (Chai, 2015). Pygidiopsis has a small and median-located ventral sucker with the presence of a ventrogenital apparatus armed with 12–15 minute spines (Chai et al., 1986a). Stellantchasmus has a small, laterally deviated ventral sucker and an elongated sac-like seminal vesicle with a muscular expulsor at the opposite side of the ventral sucker (Yu and Chai, 2010, Yu and Chai, 2013, Chai, 2015). Centrocestus has minute circumoral spines on the oral sucker (Yu and Chai, 2010, Yu and Chai, 2013, Chai, 2015). Stitodora has a gonotyl armed with spines and a separate opening of the ejaculatory duct and metraterm, but lacks a muscular bulb in the genital atrium (Chai et al., 1988). Acanthotrema is similar to Stictodora but differs in having fewer than 12 sclerotizations on the ventral sucker; more than 12 spines in the latter (Sohn et al., 2003a, Sohn et al., 2003b).

The purpose of this review is to provide the most updated knowledge on the morphology, biology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and pathology, immunology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment, and prevention and control of fishborne zoonotic heterophyid infections. In this review, those species naturally occurring in humans, as well as those in which experimental human infection was successful, were included.

2. Morphology, biology, and epidemiology

2.1. Metagonimus

Flukes of Metagonimus are characterized by the presence of a small submedian and unarmed ventral sucker; they differ from Heterophyes in lacking a genital sucker and gonotyl and from Haplorchis in having two testes (Chai, 2007, Chai, 2017). The genus Metagonimus was erected with M. yokogawai as the type species (Katsurada, 1912, Yokogawa, 1913a, Ito, 1964a), and 8 more species (total 9 species) have been described to date. They include M. ovatus (Yokogawa, 1913b); M. takahashii (Suzuki, 1930), M. minutus (Katsuta, 1932a), M. katsuradai (Izumi, 1935), M. otsurui (Saito and Shimizu, 1968), M. miyatai (Saito et al., 1997), M. hakubaensis (Shimazu, 1999), and M. suifunensis (Shumenko et al., 2017) (Table 1). Among them, M. yokogawai, M. takahashii, and M. miyatai are the 3 major human-infecting species in Japan and Korea (Chai et al., 2005a, Chai et al., 2009a, Chai et al., 2015a). An experimental human infection was reported to be successful in M. katsuradai (Izumi, 1935), and M. minutus was included among the list of human-infecting species in Taiwan without literature background (Yu and Mott, 1994). Hence, 5 species, namely, M. yokogawai, M. takahashii, M. miyatai, M. minutus, and M. katsuradai, are regarded as zoonotic or potentially zoonotic species. It should be reminded that some of old literature on M. yokogawai is actually referring to M. takahashii or M. miyatai, and caution is required when reviewing M. yokogawai in strict sense (Chai et al., 2009a, Chai, 2015, Chai, 2017).

Table 1.

Species of Metagonimus reported in the literature.

| Species | Human infection | Country/region | First reporter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metagonimus yokogawai | Yes | Korea, Japan, China, Taiwan, Russia, India, Europe | Katsurada (1912) |

| Metagonimus takahashii | Yes | Korea, Japan | Takahashi (1929a), Suzuki (1930) |

| Metagonimus miyatai | Yes | Korea, Japan | Katsurada (1912), Saito et al. (1997) |

| Metagonimus minutus | Yesa | Taiwan | Katsuta (1932a) |

| Metagonimus katsuradai | Yesb | Japan, Russia | Izumi (1935) |

| Metagonimus ovatus | No | Japan | Yokogawa (1913b) |

| Metagonimus otsurui | No | Japan | Saito and Shimizu (1968) |

| Metagonimus hakubaensis | No | Japan | Shimazu (1999) |

| Metagonimus suifunensis | No | Russia | Shumenko et al. (2017) |

Listed as a human-infecting species (Yu and Mott, 1994) without adequate documentation.

Experimental human infection was reported.

2.1.1. Metagonimus yokogawai (Katsurada, 1912) Katsurada, 1912

The original description of this species is based on adult specimens recovered from an experimental dog fed the metacercariae in the sweetfish (Plecoglossus altivelis) from Taiwan (Katsurada, 1912, Shimazu and Kino, 2015). It is now known to distribute mainly in the Far Eastern countries (Chai, 2017). Its characteristic morphology include a minute body, a small laterally deviated ventral sucker with no ventrogenital apparatus and no genital sucker, a medially-located ovary, and two testes located almost side-by-side near the posterior end of body (Ito, 1964a, Chai et al., 2009a, Yu and Chai, 2013) (Fig. 2). M. takahashii and M. miyatai have two testes separated from each other (Chai et al., 2009a). In addition, the vitelline follicles of M. yokogawai extend in lateral fields from the level of the ovary down to the posterior end of the posterior testis, but not beyond the posterior testis (Saito et al., 1997, Chai, 2015). In M. takahashii, the vitelline follicles distribute abundantly beyond the posterior testis level (Chai et al., 2009a). The uterine tubules of M. yokogawai never overlap or cross over the middle portion of the anterior testis, whereas M. takahashii and M. miyatai have the uterine tubules which overlap the whole anterior testis (Chai et al., 1993a, Saito et al., 1997).

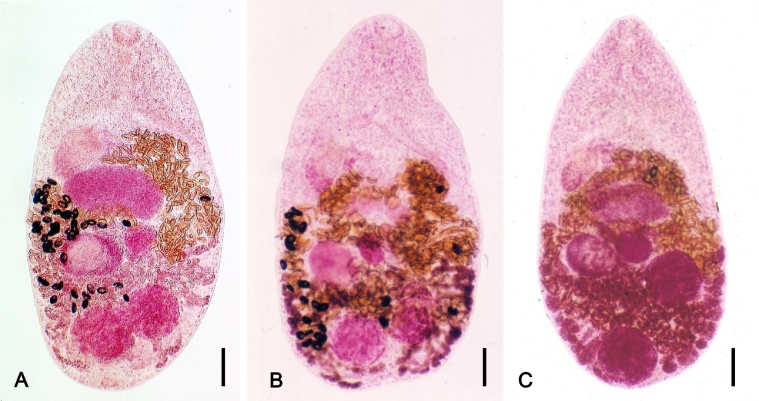

Fig. 2.

Morphology of Metagonimus spp. infecting humans. (A) Metagonimus yokogawai, (B) Metagonimus takahashii, and (C) Metagonimus miyatai. Note that M. yokogawai has two adjacent testes, whereas M. takahashii and M. miyatai have more or less two separated testes. The uterine tubule of M. yokogawai does not overlap with the anterior testis, but the tubules of M. takahashii and M. miyatai do overlap with the anterior testis. Vitelline follicles are distributed diffusely beyond the post-testicular areas in M. takahashii but not in M. yokogawai and M. miyatai. Scale bars; (A) = 100 μm, (B) = 100 μm, (C) = 100 μm.

Freshwater snails (including Semisulcospira libertina and S. coreana) have been reported to be the molluscan intermediate host (Ito, 1964b, Cho et al., 1984). The most important fish host is the sweetfish (Plecoglossus altivelis) in Korea and Japan (Ito, 1964a, Chai and Lee, 2002, Sohn, 2009, Chai, 2007, Chai, 2015). The big-scaled redfin (Tribolodon hokonensis), Pacific redfin (T. taczanowskii), and the perch (Lateolabrax japonicus) have also been reported as the fish host (Chai, 2007, Chai et al., 2009a, Yu and Chai, 2013, Chai, 2015). The natural definitive hosts are humans (Chai et al., 2009a), dogs (Komiya, 1965, Cho et al., 1981), rats (Seo et al., 1981a), cats (Huh et al., 1993), foxes (Miyamoto, 1985), boars (Komiya, 1965), and kites (bird) (Miyamoto, 1985). Mice, rats, cats, dogs, gerbils, hamsters, and ducks are experimental definitive hosts (Guk et al., 2005, Chai et al., 2009a, Li et al., 2010, Li et al., 2013). Guk et al. (2005) studied on the growth and development of M. yokogawai in different strains of mice (BALB/c, ddY, C57BL/6J, C3H/HeN, and A/J) and found that ddY mice were the most highly suitable strain.

The principal mode of human infection is consumption of raw or improperly cooked freshwater fish, notably the sweetfish (P. altivelis) and the big-scaled redfin (T. hakonensis) (under the name T. taczanowskii) (Yu and Chai, 2013, Chai, 2015). Pickled, salted, or fermented fish, as well as cooking knife and chopping board contaminated with the metacercariae may also cause human infections (Chai, 2015). Major endemic areas are scattered in Far Eastern countries, including the Republic of Korea (= Korea), Japan, China, and Russia (Chai, 2015). In Korea, numerous endemic foci have been found, and almost all small streams to large rivers in eastern and southern coastal areas were confirmed to be endemic areas (Chai and Lee, 2002, Chai, 2007, Chai, 2015, Chai, 2017, Chai et al., 2009a). High endemic areas are the Seomjin, Tamjin, Boseong Rivers, Geoje Island, and Osip Stream in Samcheok-shi (Gangwon-do) which revealed 20–70% egg positive rates of the riparian residents (Chai and Lee, 2002, Chai et al., 1977, Chai et al., 2000, Chai et al., 2015a). Of considerable interest in Korea is that the eggs of M. yokogawai were detected from mummies of the 17th century, Joseon Dynasty (Seo et al., 2008, Shin et al., 2009). It is thus presumed that the life cycle of M. yokogawai has been actively maintained at least more than 400 years in Korea (Seo et al., 2008).

In Japan, it was originally thought that M. yokogawai infection is distributed nationwide with the exception of Hokkaido (Ito, 1964a). However, the presence of its life cycle in Hokkaido was also recognized (Miyamoto, 1985). Until the 1960s, the prevalence in humans ranged 0.5–35.1% depending on the locality surveyed (Ito, 1964a). Kagei and Kihata (1970) surveyed 26 areas of Japan and reported M. yokogawai egg positive rates as 0–73.9%; three areas of Shimane Prefecture showed the highest prevalence (73.9%, 71.9%, and 57.1%, respectively) followed by areas of Hiroshima (38.9%), Kochi (33.2%), Kagoshima (28.0%), and Saga Prefecture (27.0%). The last available literature on the prevalence (Ito et al., 1991) reported 13.2% egg positive rate among 4524 riparian people examined in Hamamatsu Lake, Shizuoka Prefecture during 1982–1988. It is presumed that the prevalence of M. yokogawai in Japan has been decreasing until now. In China, 8 human infections were confirmed by genetic analysis of fecal eggs in Guangxi Province (Jeon et al., 2012). It was stated that human infections exist in Guangdong, Anhui, Hubei, and Zhejiang Province (Yu and Mott, 1994). In Taiwan, the metacercariae of M. yokogawai were first found from the sweetfish in 1912 (Yokogawa, 1912, Ito, 1964a), and after then, human infections were occasionally reported (Chen, 1991). However, little surveys have been undertaken on the prevalence among humans (Li et al., 2013).

In Russia, the Amur and Ussuri valleys of the Khabarovsk territory have been known to be endemic areas of M. yokogawai (Yu and Mott, 1994). In this territory, the prevalence among the total population was 1–2% but the prevalence among the ethnic minority was 20–70% (Yu and Mott, 1994). Also in the north of Sakhalin Island, the infection rate was 10% among ethnic minorities and 1.5% among Russians (Yu and Mott, 1994). Sporadic cases were also reported in the Amur district and the Primorye territory (Yu and Mott, 1994, Chai, 2015). In the Khabarovsk territory, the population at risk was once estimated at 859,000, which is 14.7% of the total population in this territory (Yu and Mott, 1994). In India, the presence of human infection was suspected because two heterophyid egg positive cases (designated as M. yokogawai infection) were detected (Mahanta et al., 1995, Uppal and Wadhwa, 2005). In Europe, the existence of M. yokogawai infection (in some references described as Metagonimus sp.) have been reported in fish hosts and wild animals of Ukraine (Davydov et al., 2011), Serbia (Djikanovic et al., 2011), Bulgaria (Nachev and Sures, 2009, Ondračkova et al., 2012), and Czech Republic (Francová et al., 2011). However, human infections have not yet been confirmed.

2.1.2. Metagonimus takahashii (Takahashi, 1929) Suzuki, 1930

This species was originally found from the small intestine of mice and dogs fed the metacercariae encysted in freshwater fish in Japan (Takahashi, 1929a). A year later, it was proposed as a new species M. takahashii admitting that the large egg size is enough to be a specific character (Suzuki, 1930). Its taxonomic validity had long been debated by Japanese parasitologists. However, Saito, 1972, Saito, 1973 strongly supported the validity of M. takahashii based not only on its remarkably larger egg size but also on differential morphologies of larval and adult stages and also by the different host specificities at experimental infection with the cercariae. Thereafter, the name M. takahashii has been settled. M. takahashii differs morphologically from M. yokogawai and M. miyatai in the position of the two testes, distribution of vitelline follicles, and size of their eggs (Saito, 1984, Chai et al., 1993a, Chai, 2015) (Fig. 2). It also differs from M. katsuradai, M. otsurui, and M. hakubaensis in that the latter three species have a smaller ventral sucker than the oral sucker (Saito, 1984, Shimazu, 1999, Chai, 2015). M. minutus, having a larger ventral sucker than the oral sucker, differs from M. takahashii and M. yokogawai in having a smaller body and eggs, larger seminal vesicle, and different fish host (Katsuta, 1932a, Chai et al., 1993a).

The snail hosts are Semisulcospira spp. (including S. libertina and S. coreana) (Saito, 1972, Cho et al., 1984). The fish hosts include the crussian carp (Carassius auratus), carp (Cyprinus carpio), big-scaled redfin (T. hakonensis), and perch (L. japonicus) (Takahashi, 1929a, Saito, 1984, Sohn, 2009, Chai, 2015). The natural definitive hosts are mice, rats, dogs, cats, pelicans, kites, and other avian species (Takahashi, 1929a, Yamaguti, 1958, Ahn, 1993). The experimental definitive hosts include mice, rats and dogs, cats, hamsters, and rabbits (Takahashi, 1929a, Saito, 1972, Chai et al., 1991, Rim et al., 1996, Guk et al., 2005, Chai, 2017). The growth and development of M. takahashii were studied in different strains of mice (BALB/c, ddY, C57BL/6J, C3H/HeN, and A/J), that were generally not a good experimental host (Guk et al., 2005).

This species is known to distribute only in Korea and Japan. However, it is possibly distributed in other countries. In Korea, M. takahashii was first found in experimental rabbits fed the metacercariae from carps (Chun, 1960a). The presence of human infections (mixed with Metagonimus sp., presumably M. miyatai) was first demonstrated by adult worm recovery from riparian people along the Hongcheon River, Gangwon-do (Ahn and Ryang, 1988). An endemic area was subsequently discovered along the upper reaches of the Namhan River, mixed-infected with M. miyatai, with an egg positive rate of 9.7% for both species (Chai et al., 1993a). A recent survey performed along the Boseong River, Jeollanam-do (M. yokogawai endemic area) detected 3293 specimens of M. takahashii from 11 riparian residents out of a total of 70,223 intestinal fluke specimens (mostly M. yokogawai) (Chai et al., 2015a). In Japan, articles regarding its existence have been published (Ito, 1964a, Saito, 1972, Saito, 1973). However, because of taxonomic debates and confusion between M. takahashii and M. yokogawai, its precise epidemiologic status, including the prevalence and geographical distribution of human infections, has not been clearly defined (Chai, 2015). An earlier study in Okayama City reported infection of M. takahashii in 43 (0.64%) of 6680 residents examined, whereas infection of M. yokogawai was found in 54 (0.81%) residents (Takahashi, 1929a). Later, in Fuchu City, Hiroshima Prefecture, 11 (4.8%) of 231 residents examined were infected with M. takahashii, whereas 81 (35.1) were infected with M. yokogawai (Asada et al., 1957).

2.1.3. Metagonimus miyatai Saito, Chai, Kim, Lee, and Rim, 1997

Saito et al. (1997) described M. miyatai as a new species based on adult flukes collected from dogs and hamsters experimentally fed the metacercariae from the sweetfish (P. altivelis), dace (T. hakonensis and T. taczanowskii), Amur fat-minnow (Phoxinus steindachneri) (under the name Morocco steindachneri), pale chub (Zacco platypus), and dark chub (Zacco temminckii) in Korea and Japan. This species was actually first found by Katsurada (1912) (shown only by a figure drawing) together with M. yokogawai in Taiwan, but at that time it was regarded as a paratype specimen of M. yokogawai (Saito et al., 1997). Human infections have been reported from Korea and Japan (Saito et al., 1997, Chai et al., 1993a, Chai et al., 2015a). M. miyatai is morphologically characterized by two markedly separated testes from each other, with the posterior one located very close to the posterior body wall, vitelline follicles never distributing beyond the posterior testis, and the egg size which is intermediate between those of M. yokogawai and M. takahashii (Chai et al., 1993a, Saito et al., 1997, Yu and Chai, 2013, Chai, 2015) (Fig. 2). It differs from M. minutus in its larger body and egg size (Katsuta, 1932a, Chai et al., 1993a). M. miyatai is also genetically distinct from M. yokogawai and M. takahashii (Yu et al., 1997a, Yu et al., 1997b, Lee et al., 1999, Yang et al., 2000).

The snail host includes S. libertina, S. dolorosa, S. globus, and Koreanomelania nodifila (Kim, 1980, Kim et al., 1987, Shimazu, 2002). The metacercariae have been detected in freshwater fish (including Z. platypus, Z. temminckii, P. altivelis, T. hakonensis, T. taczanowskii, Opsariichthys bidens, and Phoxinus steindachneri) (Saito et al., 1997, Shimazu, 2002, Sohn, 2009). Natural definitive hosts include the dog, red fox, raccoon dog, and black-eared kite (Saito et al., 1997, Chai, 2015). Experimental definitive hosts are the mouse, rat, hamster, and dog (Kim, 1980, Kim et al., 1987, Chai et al., 1991, Ahn and Ryang, 1995, Saito et al., 1997, Shimazu, 2002, Chai, 2017). The worm growth and development was studied in different strains of mice (BALB/c, ddY, C57BL/6J, C3H/HeN, and A/J); mice were generally not a susceptible animal host (Guk et al., 2005).

The major source of human infection is raw or improperly cooked freshwater fish, in particular, the pale chub (Z. platypus) in Korea and Japan (Chai, 2015). In Korea, the presence of human infections (under the name Metagonimus sp.) was first demonstrated by Kim (1980) in Geum River by detecting eggs in the feces and recovery of adult flukes from several cases. Kim et al. (1987) performed another survey around the Lake Daecheong and its upper reaches (designated the worms as Metagonimus Miyata type of Saito, 1984) and reported Z. platypus and Opsariichthys bidens as the most heavily infected fish species. Adult specimens were recovered from 32 people living along the Namhan River in Eumseong-gun (9.7% in egg positive rate) and Yeongwol-gun (48.1% in egg positive rate) (Chai et al., 1993a). A most recent survey performed along the Boseong River, Jeollanam-do (M. yokogawai endemic area) detected 343 specimens of M. miyatai from 11 riparian residents out of a total of 70,223 intestinal fluke specimens (mostly M. yokogawai) (Chai et al., 2015a). In Japan, epidemiological studies, particularly on human infections, are scarce. With regard to animal definitive hosts, Saito et al. (1997) listed dogs, foxes, raccoon dogs, and black-eared kites in Shimane, Kochi, and Yamagata Prefectures. Metacercariae were detected in a fish species (P. steindachneri) in Hiroi River basin, Nagano Prefecture (Shimazu, 2002). Small rivers of Shizuoka Prefecture were also found to have M. miyatai metacercariae-infected fish (Kino et al., 2006).

2.1.4. Metagonimus minutus Katsuta, 1932

The original description of this species is based on adult flukes recovered from cats and mice experimentally fed the metacercariae in the brackish water mullet in Taiwan (Katsuta, 1932a). It is smaller than M. yokogawai, M. takahashii, and M. miyatai in its egg and adult worm size (Katsuta, 1932a, Ito, 1964a, Saito et al., 1997). Its body size is slightly larger than M. katsuradai but its egg size is smaller than M. katsuradai (Katsuta, 1932a, Izumi, 1935). Its oral sucker is smaller than the ventral sucker, whereas, in M. katsuradai, the oral sucker is bigger than the ventral sucker (Katsuta, 1932a, Izumi, 1935, Chai, 2015). This species has been listed as a human-infecting intestinal fluke species in Taiwan but the literature background is not available (Yu and Mott, 1994).

The molluscan host is unknown. The metacercariae are found in the scales, gills, and fins of the mullets (Mugil cephalus) (Katsuta, 1932a). Natural definitive hosts have not been discovered. Cats and mice were used as experimental definitive hosts (Katsuta, 1932a). Eating raw or improperly cooked mullets in endemic areas is a risk factor. Distribution of this species in other countries is unknown.

2.1.5. Metagonimus katsuradai Izumi, 1935

The original description of this species is based on adult flukes recovered from rats, mice, rabbits, dogs, and cats experimentally infected with the metacercariae obtained from freshwater fish (including Pseudorasbora parva, Z. platypus, and Tanakia lanceolata) in Japan (Izumi, 1935). The possibility of human infection was experimentally proven through infection to author himself and family (Izumi, 1935). The body of M. katsuradai is slightly smaller than M. minutus but its eggs are larger than M. katsuradai (Katsuta, 1932a, Izumi, 1935). It differs from M. yokogawai, M. takahashii, M. miyatai, and M. minutus in having a smaller ventral sucker than the oral sucker (Yu and Chai, 2013, Chai, 2015). It also differs from M. otsurui in the position of the seminal receptacle (Saito and Shimizu, 1968). It differs from M. hakubaensis in its long ceca that enter the post-testicular region (Shimazu, 1999).

The molluscan host is S. libertina in Japan (Kurokawa, 1939) and Juga tegulata in Russia (Besprozvannykh et al., 1987). The second host is freshwater fish (including Tanakia lanceolata, T. oryzae, T. limbata, Acheilognathus rhombeus, T. moriokae, P. parva, Z. platypus, and Gnathopogon elongatus) (Izumi, 1935, Ito, 1964a, Shimazu, 2003). Dogs are the only found natural definitive host (Yoshikawa et al., 1940). Experimental definitive hosts include humans, mice, white mice, rats, rabbits, puppies, kittens, ducks, and golden hamsters (Izumi, 1935, Kurokawa, 1939, Shimazu, 2003, Chai, 2017). Consumption of raw or improperly cooked freshwater fish (Z. platypus and others) is a risk factor (Ito, 1964a).

In Japan, its presence has been reported in several localities (Kurokawa, 1939, Ito, 1964a, Urabe, 2003). However, natural human cases have never been documented. In Russia, the existence of its life cycle was reported by Besprozvannykh et al. (1987) in the southern Primorye region through discovery of cercariae in Juga snails and metacercariae in 6 species of freshwater fish. Without firm evidence, it is listed among the human-infecting trematodes in the Primorye Territory (Emolenko et al., 2015).

2.2. Heterophyes

Flukes of Heterophyes are characterized by the presence of a genital sucker and armed gonotyl; they differ from Metagonimus in having a large median located ventral sucker and from Haplorchis in having only one testis (Chai, 2007). Heterophyes flukes were first discovered by Bilharz in 1851 at an autopsy of an Egyptian and named as Distomum heterophyes by von Siebold in 1852 (Chai, 2007, Chai, 2014b). The genus Heterophyes was raised by Cobbold in 1866 with Heterophyes aegyptiaca as the type; later this was synonymized with H. heterophyes (Witenberg, 1929). A total of 18 species or subspecies had been described in the genus Heterophyes (Chai, 2014b). However, three species were moved to another genus Alloheterophyes by Pearson (1999) and nine species were synonymized with H. heterophyes or other pre-existing species (Chai, 2014b). Now, the number of valid species of Heterophyes is only six (Pearson, 1999, Chai, 2014b), namely, H. heterophyes (by von Siebold in 1852), H. nocens (Onji and Nishio, 1916), H. dispar (Looss, 1902), H. aequalis (Looss, 1902), H. indica (Rao and Ayyar, 1931), and H. pleomorphis (Bwangamoi and Ojok, 1977) (Table 2). Four species, H. heterophyes, H. nocens, H. dispar, and H. aequalis, are known to infect humans (Ashford and Crewe, 2003, Chai, 2014b). Caution is needed to refer to some old literature which dealt with H. nocens as a synonym of H. heterophyes.

Table 2.

Species of Heterophyes reported in the literature.

| Species | Human infection | Country/region | First reporter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterophyes heterophyes | Yes | Egypt, Sudan, Palestine, Turkey, India, Middle East, Japana, Koreaa | von Siebold in 1852 (Ransom, 1920) |

| Heterophyes nocens | Yes | Korea, Japan | Onji and Nishio (1916) |

| Heterophyes dispar | Yes | Egypt, Middle East, Koreab | Looss (1902) |

| Heterophyes aequalis | Yes | Egypt, Middle East | Looss (1902) |

| Heterophyes indica | No | India | Rao and Ayyar (1931) |

| Heterophyes pleomorphis | No | Uganda | Bwangamoi and Ojok (1977) |

| Twelve other species (subspecies)c | No |

Imported human cases were reported in Japan (Kagei et al., 1980) and Korea (Eom et al., 1985a, Chai et al., 1986b).

Imported human cases were reported in Korea (Eom et al., 1985a, Eom et al., 1985b, Chai et al., 1986a, Chai et al., 1986b).

Six of them, including H. aegyptiaca, H. fraternus, H. persicus, H. heterophyes sentus, H. inops, and H. palidus, were synonymized with H. heterophyes (Witenberg, 1929). H. dispar limatus was synonymized with H. dispar (Witenberg, 1929). The validity of H. elliptica has been questioned (Waikagul and Pearson, 1989). H. katsuradai was synonymized with H. nocens (Witenberg, 1929). H. superspinata (syn. H. bitorquatus) and H. chini have been transferred to another genus Alloheterophyes (Pearson, 1999).

2.2.1. Heterophyes heterophyes (v. Siebold, 1852) Stiles and Hassal, 1900

This species was first discovered by Bilharz in 1851 at autopsy of an Egyptian in Cairo (Chai, 2007, Chai, 2014b). It is now known to cause human infections along the Nile Delta of Egypt and Sudan, the Middle East, southeastern Europe, and India (Yu and Mott, 1994, Mahanta et al., 1995, Pica et al., 2003, Chai et al., 2005a). The adult flukes are minute, ovoid to elliptical, elongate, or pyriform in shape (Witenberg, 1929). Their unique morphologies include the presence of two side-by-side testes near the posterior extremity of the body, a large ventral sucker which is located median, and a large submedian genital sucker armed with 70–85 chitinous rodlets on the gonotyl (Chai, 2007, Chai, 2014b) (Fig. 3). Adults of H. heterophyes differ from those of H. nocens mainly in the number of rodlets on the gonotyl; 50–62 in H. nocens and 70–85 in H. heterophyes (Witenberg, 1929, Chai et al., 1994b, Chai et al., 2009a). Adults of H. dispar are slightly smaller in body size and have smaller sizes of the genital sucker and smaller numbers of rodlets on the gonotyl (22–35) compared with those of H. heterophyes and H. nocens (Witenberg, 1929, Chai et al., 1986a, Chai et al., 2009a).

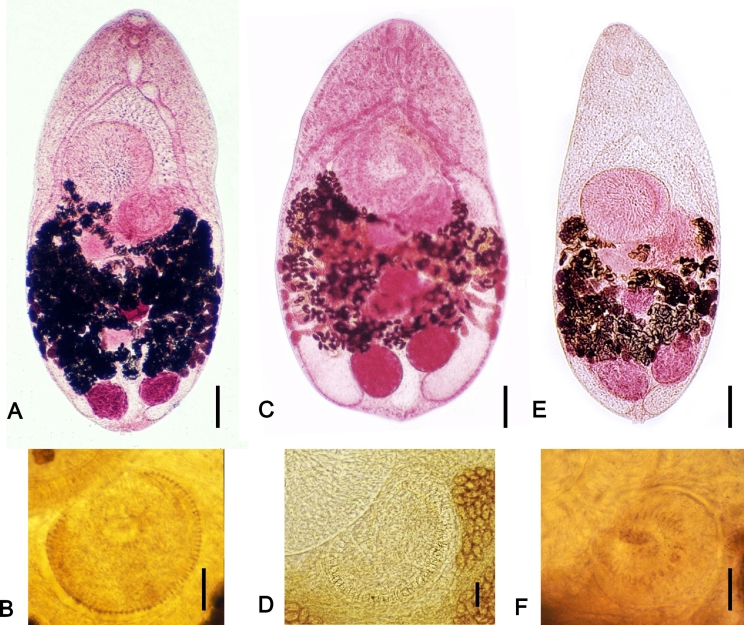

Fig. 3.

Morphology of Heterophyes spp. infecting humans. (A, B) Heterophyes heterophyes, (C, D) Heterophyes nocens, and (E, F) Heterophyes dispar. Note that H. heterophyes has a gonotyl armed with more than 70 chitinous spines (rodlets) around the genital sucker (B), whereas H. nocens and H. dispar have about 60 (D) and 30 rodlets (F), respectively. Scale bars; (A) = 100 μm, (B) = 100 μm, (C) = 100 μm, (D) = 10 μm, (E) = 10 μm, (F) = 10 μm. The photo (A) has been reproduced, with permission, from the black and white photo of the same specimen reported by Chai et al. (1986b) in Korean J. Parasitol. 24, 82–88.

The eggs contain a fully developed miracidium and hatch after ingestion by an appropriate freshwater snail (for example, Pirenella conica) (Taraschewski, 1984). The cercariae enter between the scales of freshwater or brackish water fish, including mullets (Mugil cephalus, Mugil capito, Mugil auratus, Mugil saliens, and Mugil chelo), Tilapia fish (Tilapia nilotica and Tilapia zilli), and gobies/other fish (Aphanius fasciatus, Barbus canis, Sciaena aquilla, Solea vulgaris, and Acanthogobius sp.), and encyst chiefly in the muscle of these fish host (Paperna and Overstreet, 1981, Velasquez, 1982). Various species of mammals and birds, including dogs, cats, wolves, bats, rats, foxes, sea gulls, and pelicans, act as the natural definitive hosts and take the role of reservoir hosts (Yamaguti, 1958, Chai, 2014b). Rats, dogs, cats, foxes, badgers, pigs, macaques, and gulls can be experimental definitive hosts (Chai, 2014b).

The principal mode of human infections is consuming raw or improperly cooked fish, notably mullets and gobies (Chai, 2014b). Human and/or animal infections have been reported in Egypt, Sudan, Greece, Turkey, Palestine, Italy, Tunisia, India, and the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Yemen (Yu and Mott, 1994, Chai, 2014b, Tandon et al., 2015). About 30 million people are estimated to be infected with this fluke (Mehlhorn, 2015). In Egypt, human infections are commonly found in the northern part of the Nile Delta, particularly around Lakes Manzala, Burullus, and Edku, where fishermen and domestic animals frequently consume fish (Yu and Mott, 1994, Youssef and Uga, 2014). In an earlier report, an extremely high prevalence (88%) was found among schoolchildren at Mataria on Lake Manzala (Khalil, 1933). In Dakahlia Governorate, the disease was common in both urban and rural localities owing to the habit of consuming salted or insufficiently baked fish (Sheir and Aboul-Enein, 1970). After 1960s–1980s, the prevalence began to decline down to 2.5–10.0% in these areas (Rifaat et al., 1980, Youssef et al., 1987a). However, near the Lake Edku, the prevalence among 2219 individuals was 33.8% demonstrating still considerably high endemicity in northern parts of Nile Delta (Abou-Basha et al., 2000). Interestingly, some Japanese immigrants living in Egypt were found positive for heterophyid eggs (including H. heterophyes); the prevalence was 11% in 2005, 11% in 2006, 15% in 2007, and 14% in 2008 (Okuzawa et al., 2010).

In Sudan, few epidemiological surveys have been undertaken, although some humans (Koreans) who lived in Sudan and returned home were found infected with H. heterophyes and H. dispar (Eom et al., 1985a). In Iran, the prevalence of heterophyid (including H. heterophyes) infections in humans and animals was documented by Massoud et al. (1981); in 13 villages of Khuzestan, the prevalence ranged 2–24%. In Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Dubai, and United Arab Emirates, no reports are available on human infections. However, the existence of H. heterophyes has been documented in fish intermediate hosts or animal reservoir hosts (Abdul-Salam and Baker, 1990, Khalil et al., 2014, El-Azazy et al., 2015). Sporadic H. heterophyes infection has been reported from Greece, Turkey, Italy, Spain, Tunisia, Yemen, and Sri Lanka (Taraschewski and Nicolaidou, 1987, Yu and Mott, 1994, Martínez-Alonso et al., 1999). Imported human cases were reported in France (Rousset and Pasticier, 1972), Korea (Eom et al., 1985a, Chai et al., 1986a), and Japan (Kagei et al., 1980); the patients returned from Egypt, Saudi Arabia, or Sudan. In USA, a woman patient was found to be infected with H. heterophyes (the species is uncertain because only eggs were detected in her stool) after eating ‘sushi’ in a local Japanese restaurant (Adams et al., 1986).

2.2.2. Heterophyes nocens Onji and Nishio, 1916

The original description of this species is based on adult flukes recovered from experimental dogs and cats fed the metacercariae encysted in mullets Mugil cephalus in Japan (Onji and Nishio, 1916). Later, Heterophyes katsuradai was recovered from a man in Kobe, Japan and described as a new species (Ozaki and Asada, 1926). However, it was synonymized with H. nocens (Witenberg, 1929, Waikagul and Pearson, 1989). It is now known to occur in Korea, Japan, China, Taiwan (in China and Taiwan, the name was written as H. heterophyes probably by an error), and Thailand (Yokogawa et al., 1965, Seo et al., 1981b, Chai et al., 1984, Chai et al., 1985, Yu and Mott, 1994, Namchote et al., 2015). Its adult flukes are elongate, elliptical, or pyriform, and morphologically close to H. heterophyes (Chai et al., 1986b, Chai et al., 1994b). The only recognizable difference is the smaller number of rodlets on the gonotyl of the genital sucker in H. nocens (50–62) compared to that in H. heterophyes (70–85) (Taraschewski, 1984, Chai et al., 1986b, Chai et al., 1994b, Chai and Lee, 2002) (Fig. 3). H. dispar has a slightly smaller body, a smaller-sized genital sucker, and a smaller number (22–35) of rodlets on the gonotyl compared to H. nocens and H. heterophyes (Witenberg, 1929, Chai et al., 1986b). H. aequalis is also smaller in body size than H. nocens and H. heterophyes, has relatively short ceca, and has a smaller number (14–25) of rodlets on the gonotyl (Witenberg, 1929, Chai et al., 1986b).

The eggs hatch after ingestion by an appropriate brackish water snail, for example, Cerithidea cingulata (= Tympanotonus microptera) or Cerithidea fluviatilis (Ito, 1964b). The cercariae enter between the scales of brackish water fish, including mullets and gobies (Mugil cephalus, Liza menada, Tridentiger obscurus, Glossogobius brunnaeus, Therapon oxyrhynchus, and Acanthogobius flavimanus) (Ito, 1964a, Komiya, 1965, Sohn, 2009). Two species of brackish water gobies (Boleophthalmus pectinirostris and Scartelaos sp.) can also host H. nocens (Sohn et al., 2005). Cats, dogs, and rats are natural definitive hosts (Yoshikawa et al., 1940, Ito, 1964a, Seo et al., 1981a, Eom et al., 1985b, Sohn and Chai, 2005, Shin et al., 2015). Mice and rats can be used as experimental definitive hosts (Chai et al., 2009a, Chai, 2014b).

Raw or improperly cooked mullets and gobies are the major source of human infections (Chai, 2014b). Human infections have been reported in Korea, Japan, China, and Taiwan (Yu and Mott, 1994). In Korea, about 50,000 people are estimated to be infected with this fluke (Chai and Lee, 2002). In Korea, human infection was first identified in a man residing in a seashore village along the Western Sea (= Yellow Sea) (Seo et al., 1981b). Thereafter, cases were reported from western and southern coastal areas (Chai et al., 1984, Chai et al., 1985). Subsequently, numerous endemic areas with 10–40% prevalences were detected in southwestern coastal areas, i.e., Jeollanam-do and Gyeongsangnam-do Province (Chai et al., 1994b, Chai et al., 1997, Chai et al., 1998, Chai et al., 2004, Park et al., 2007, Guk et al., 2007). In addition, in an inland area of Boseong-gun (along the Boseong River) where M. yokogawai is highly endemic, a few adult specimens of H. nocens were also recovered from some riparian residents (Chai et al., 2015a).

In Japan, an earlier study reported 18.5% prevalence among inhabitants in Yamaguchi Prefecture (Onji, 1915). Later, in Chiba Prefecture, the heterophyid egg positive rate was 8.0% among residents in Goi-Machi village and 9.0% in Misaki-Machi village (Yokogawa et al., 1965). In Shizuoka Prefecture, the prevalence of H. nocens was 20.7% in Harai village of Izu peninsula but six years after a mass treatment, inhibition of raw fish eating, and health education, the prevalence decreased to 3.4% (Ito et al., 1967). Human H. nocens infection was also reported from Chugoku and Hiroshima Prefectures (Suzuki et al., 1982). Two lakeside villages of Mikkabi-cho, north end of Hamana Lake, Shizuoka Prefecture were also found to have 7.5% and 10.5% prevalences of H. nocens eggs (Kino et al., 2002). In China, human infections (under the name H. heterophyes) were reported in provinces of mainland China (Guangdong, Hubei, and Beijing) and Taiwan (Yu and Mott, 1994). However, the parasite may have been actually H. nocens (Chai, 2014b). The life cycle of H. nocens may be present in Thailand, since cercariae of Heterophyes sp. were recovered from brackish water snails (Namchote et al., 2015). A French professor who visited Japan and consumed raw fish and aquatic plants there was found to be infected with H. nocens (under the name H. heterophyes) (Lamy et al., 1976).

2.2.3. Heterophyes dispar Looss, 1902

The original description is based on specimens discovered in the intestines of dogs and cats in Egypt (Looss, 1902). It was found in other mammals, including foxes and wolves, in the northern Africa and eastern Mediterranean, including Greece and Palestine (Witenberg, 1929, Taraschewski and Nicolaidou, 1987, Yu and Mott, 1994, Chai, 2014b). Human infections were first reported from 2 Korean men returning from Saudi Arabia (Chai et al., 1986a) and then also found in Kalasin Province, Thailand (Yu and Mott, 1994). There were taxonomic debates on H. dispar and H. aequalis, both of which were described by Looss (1902) in Egypt. However, H. dispar is distinct from H. aequalis in the larger number of rodlets (22–35) on the gonotyl compared with H. aequalis (14–25) and long ceca extending down to the posterior margin of two testes in H. dispar, whereas they are ending before the anterior margin of two testes in H. aequalis (Looss, 1902, Witenberg, 1929). Based on several differential characters, Taraschewski, 1985a, Taraschewski, 1985b, Taraschewski, 1987 acknowledged the validity of both species. Adults of H. dispar are elliptical or pyriform, and slightly smaller than those of H. heterophyes and H. nocens (Chai et al., 1986a, Chai, 2014b). A remarkable difference is the smaller number of rodlets on the gonotyl of the genital sucker in H. dispar (22–35) compared to that in H. heterophyes (70–85) and H. nocens (50–62) (Chai et al., 1986a, Chai et al., 1994b, Chai, 2014b) (Fig. 3).

Freshwater or brackish water snails (P. conica) serve as the first intermediate host, and various species of freshwater or brackish water fish (including Mugil spp., Epinephelus enaeus, Tilapia spp., Lichia spp., Barbus canis, Solea vulgaris, and Sciaena aquilla) are the second intermediate hosts (Witenberg, 1929, Paperna and Overstreet, 1981, Taraschewski, 1984). Natural definitive hosts include dogs, cats, wolves, jackals, foxes, and kites (Witenberg, 1929, Chai, 2014b). Pups, rabbits, rats, cats, and red foxes are experimental definitive hosts (Taraschewski, 1985b).

Human infections may occur when Mugil spp. fish are eaten raw or under inadequately cooked conditions (Chai, 2014b). However, human infections were unknown before 1985–1986 when some Korean men were found infected with this fluke together with H. heterophyes who returned from Sudan (Eom et al., 1985a) and Saudi Arabia (Chai et al., 1986a). Human infectins were also confirmed in Thailand (Yu and Mott, 1994).

2.2.4. Heterophyes aequalis Looss, 1902

The original description is based on specimens discovered in the intestines of dogs and cats in Egypt (Looss, 1902). It infects various other mammals too (Witenberg, 1929, Taraschewski, 1985b). The presence of human infections was first mentioned by Kahlil in Egypt in 1991 (Ashford and Crewe, 2003), although the literature background is difficult to obtain. Morphologically H. aequalis is most similar to H. dispar but distinct from it in the smaller number of rodlets (14–25) on the gonotyl in comparison with H. dispar (22–35) and short ceca ending extending before the anterior margin of two testes in H. aequalis, whereas they reach down to the posterior margin of two testes in H. dispar (Looss, 1902, Witenberg, 1929).

Brackish water snails (P. conica) serve as the first intermediate host (Taraschewski, 1984). Freshwater or brackish water fish (including M. cephalus, M. capito, M. auratus, E. enaeus, T. simonis, L. amia, L. glauca, and B. canis) are the second intermediate hosts (Witenberg, 1929). Natural definitive hosts include cats, dogs, Persian wolves, ref. foxes, rats, pigs, pelicans, kites, and herons (Witenberg, 1929, Taraschewski, 1985b). Pups, rabbits, rats, cats, and red foxes are experimental definitive hosts (Taraschewski, 1985b). Human infections may occur when Mugil spp. fish are eaten raw or under inadequately cooked conditions (Chai, 2014b). Human infections seem to occur in Egypt (Ashford and Crewe, 2003).

2.3. Haplorchis

Flukes of Haplorchis are characterized by the presence of only one testis and a small armed ventral sucker lacking a gonotyl; they differ from Metagonimus and Heterophyes in having only one testis (Chai, 2007). They lack the expulsor-style distal part of the seminal vesicle which is present in genera Procerovum and Stellantchasmus (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). The genus Haplorchis was erected with Haplorchis pumilio as the type and Haplorchis cahirinus as another species (Looss, 1899). However, Witenberg (1929) transferred H. cahirinus to another family because it is an intestinal parasite of fish in its adult stage, whereas H. pumilio is an intestinal parasite of birds and mammals. At present, 9 species can be recognized as valid species in the genus Haplorchis. They include H. pumilio (Looss, 1899), H. taichui (Nishigori, 1924a), H. yokogawai (Katsuta, 1932b), H. vanissimus (Africa, 1938), H. parataichui (Pearson, 1964), H. sprenti (Pearson, 1964), H. wellsi (Pearson, 1964), H. parapumilio (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982), and H. paravanissimus (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982) (Table 3). Among them, H. taichui, H. pumilio, H. yokogawai, and H. vanissimus are human-infecting species. Human infections with Haplorchis spp. are prevalent in Southeast Asia, including countries located in Indo-China Peninsula, Taiwan, the Philippines, and also probably in Egypt (Chai, 2007).

Table 3.

Species of Haplorchis reported in the literature.

| Species | Human infection | Country/region | First reporter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haplorchis taichui | Yes | Thailand, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, China, Taiwan, Egypt, Palestine | Nishigori (1924a) |

| Haplorchis pumilio | Yes | Thailand, Laos, Egypt, Palestine, India, Bangladesh, China, Taiwan, Cambodia, Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Koreaa | Looss in 1886 (Looss, 1902) |

| Haplorchis yokogawai | Yes | Thailand, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, India, Indonesia, China, Taiwan, Cambodia, Vietnam, Australia, Egypt | Katsuta (1932b) |

| Haplorchis vanissimus | Yes | Philippines, Australia | Africa (1938) |

| Haplorchis sprenti | No | Australia | Pearson (1964) |

| Haplorchis wellsi | No | Taiwan | Pearson (1964) |

| Haplorchis parataichui | No | Australia | Pearson (1964) |

| Haplorchis parapumilio | No | Indonesia | Pearson and Ow-Yang (1982) |

| Haplorchis paravanissimus | No | Australia | Pearson and Ow-Yang (1982) |

A natural human case co-infected with H. pumilio, Gymnophalloides seoi, and Gynaecotyla squatarolae has been reported in Korea (Chung et al., 2011). However, Korea is tentatively not regarded as an endemic area for Haplorchis spp.

2.3.1. Haplorchis taichui (Nishigori, 1924) Chen, 1936

The original description of this species was based on specimens recovered from birds and mammals caught in the middle part of Taiwan (Nishigori, 1924a). Its characteristic morphology (Fig. 4) includes a minute and oval body with flattened dorsal and ventral sides (Faust and Nishigori, 1926). The most specific morphological feature for differentiation from other Haplorchis species is the size, shape, and number of spines on the ventral sucker (Chen, 1936, Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). H. taichui has a semi-lunar group of 12–16 long, crescentic, and hollow spines (Fig. 4) and a sinistral patch of very minute solid spines (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). Other species can be differentiated by the presence of minute sclerites on the ventral sucker (H. pumilio, H. parapumilio, H. vanissimus, and H. paravanissimus), remarkably large ventral sucker (H. wellsi), or a ventral sucker smaller than the oral sucker (H. yokogawai and H. sprenti) (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982).

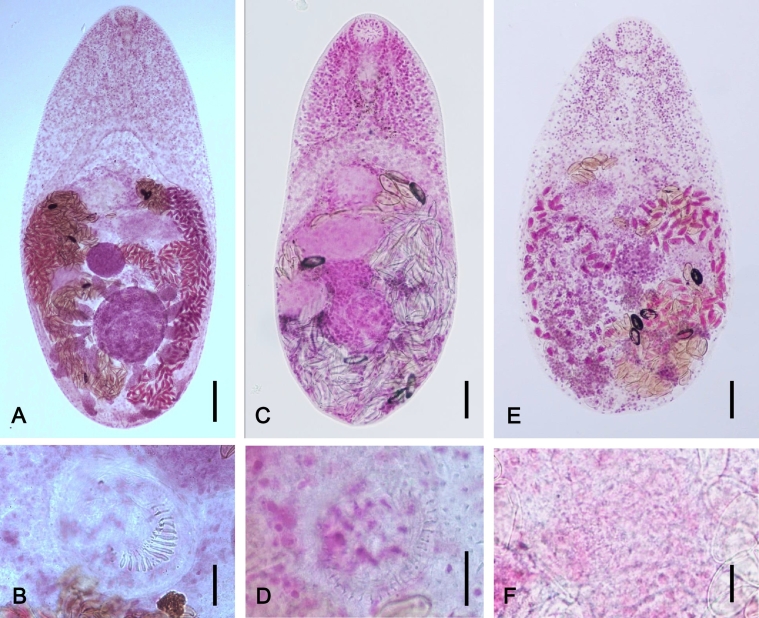

Fig. 4.

Morphology of Haplorchis spp. infecting humans. (A, B) Haplorchis taichui, (C, D) Haplorchis pumilio, and (E, F) Haplorchis yokogawai. Note that H. taichui has a gonotyl armed with 12–16 long and crescentic spines (B), whereas H. pumilio and H. yokogawai have about 32–40 minute sclerites (D) and numerous (uncountable) tiny spines (F), respectively. Scale bars; (A) = 100 μm, (B) = 100 μm, (C) = 100 μm, (D) = 10 μm, (E) = 10 μm, (F) = 10 μm.

The snail intermediate host is freshwater snails; Melania obliquegranosa in Taiwan (experimental) (Faust and Nishigori, 1926), Melanoides tuberculata and Melania juncea in the Philippines (Velasquez, 1973a), and Tarebia granifera in Hawaii (Martin, 1958). The cercariae enter between the scales of various species of freshwater fish (including Barbodes gonionotus, Cirrhinus molitorella, Cyclocheilichthys spp., Hampala spp., Labiobarbus leptocheila, Mystacoleucus marginatus, Onychostoma elongatum, Puntius spp., and Rhodeus ocellatus) (Velasquez, 1973b, Velasquez, 1982, Scholz et al., 1990, Rim et al., 2008). Birds and mammals, including dogs, cats, and humans, have been reported as the natural definitive hosts (Yamaguti, 1958). Experimental definitive hosts include mice, rats, hamsters, guinea pgs, rabbits, cats, and dogs (Faust and Nishigori, 1926, Sukontason et al., 2001). A human was also successfully infected with this fluke after swallowing the fish flesh (Faust and Nishigori, 1926).

In Thailand and Laos, fermentation is a traditional procedure for preservation of freshwater fish, and consumption of semi-fermented fish shortly after preparation increases the risk of human infections with Haplorchis spp. (Sukontason et al., 1998). Local fish dishes, notably ‘koi-pla’, ‘pla-som’, ‘pla-ra’, and ‘lab-pla’ are the major source of human infections (Sukontason et al., 1998). In the Philippines, a local fish dish called ‘kinilaw’ (freshwater fish seasoned only with salt and vinegar) is popularly consumed (Belizario et al., 2004). Other types of local fish dish in the Philippines include ‘sabaw’ (boiling fish for several minutes) and ‘sugba’ (grilling over charcoal) (Belizario et al., 2004). In Vietnam, raw or pickeld fish, for example, slices of silver carp, sold in Vietnamese restaurants are popularly consumed (Dung et al., 2007). H. taichui is known to distribute in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, South China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Hawaii, Egypt, Palestine, Bangladesh, India, and Malaysia (Velasquez, 1982, Yu and Mott, 1994, Chai et al., 2005a, Chai et al., 2009a, Chai et al., 2014a).

In Thailand, northern parts, including Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai, Mae Hong Son, and Lamphun Provinces, were found to be endemic (Radomyos et al., 1998). In Phrae Province, the prevalence of H. taichui worms among 87 worm-recovery cases was 64.4% (Pungpak et al., 1998). In Nan Province, 37 of 50 praziquantel-treated patients were positive for H. taichui worms in their diarrheic stools, whereas in Lampang Province, 69 of 100 patients revealed H. taichui worms (Wijit et al., 2013). In northeastern parts, such as Khon Kaen Province, heterophyid trematodes are common among village people (Srisawangwong et al., 1997). In Laos, human H. taichui infection was first reported from 5 Laotians (Giboda et al., 1991). Thereafter, in fecal examinations of 29,846 Loatian people from 17 provinces and Vientine Municipality, the overall positive rate of small trematode eggs (O. viverrini, H. taichui, or other minute intestinal flukes) was 10.9% (3263 peole) (Rim et al., 2003). Chai et al. (2005b) performed worm recovery of O. viverrini, H. taichui, or other minute intestinal flukes from small trematode egg positive cases in two areas; Vientiane Municipality was highly prevalent with O. viverrini worms with a small number of intestinal flukes, including H. taichui, whereas Saravane Province was severely infected with H. taichui worms with a small number of O. viverrini specimens. Hyperendemicity of H. taichui, with high prevalence and heavy worm burden, was again documented in Saravane Province (Chai et al., 2013a). In Savannakhet Province, the prevalence of small trematode eggs among the riparian people was 67.1% (658/981), and the worms recovered after chemotherapy and purging of 29 egg-positive people consisted of similar numbers of O. viverrini (3347 worms) and H. taichui (2977 worms) (Chai et al., 2007). In Khammouane Province, the prevalence of small trematode eggs among the riparian people was higher than that in Savannakhet Province, 81.1% (1007/1242) (Chai et al., 2009b). An interesting finding in Phongsali Province was that the high prevalence (18.4%) of small trematode eggs notified (Rim et al., 2003) was confirmed to be exclusively due to H. taichui and H. yokogawai infections but not to O. viverrini infection (Chai et al., 2010). Also in Champasak and Luang Prabang Provinces, the infection was mostly due to intestinal flukes, in particular, H. taichui, H. yokogawai, and H. pumilio (Chai et al., 2013a, Chai et al., 2013b, Chai et al., 2013c, Sohn et al., 2014).

In Vietnam, a high prevalence (64.9%; 399/615) of minute intestinal trematodes, including H. taichui, H. pumilio (dominant species), and H. yokogawai, has been confirmed in human infections in two communes of Nam Dinh Province, a northern part of Vietnam (Dung et al., 2007). Later, in another commune in Nam Dinh Province, 22.7% (92/405) of household members were positive for small trematode eggs (De and Le, 2011). In Southern China, the presence of human H. taichui infection was first documented from Guangxi Province in 2004 (T. Li et al., 2010). Later, in several different areas of Guangxi Province, 28.0–70.6% prevalence was obtained by fecal examination for small trematode eggs; PCR analysis of the feces revealed that 29 of 46 egg positive cases were due to H. taichui (Jeon et al., 2012). In Taiwan, where H. taichui was originally discovered (Nishigori, 1924a, Faust and Nishigori, 1926), little study has been available on human infections with this fluke. In the Philippines, the Lake Lanao, Marawi City, Mindanao Island and U.P. rice paddies, Diliman, Quezon City, and Luzon Island have been listed as endemic areas of H. taichui (Velasquez, 1973b). In southern Mindanao, 36.0% (87/242) egg positive rate was reported from residents; H. taichui adult flukes were recovered from some of these people (Belizario et al., 2004). In Egypt and Kuwait, little has been reported regarding human infections; however, the presence of H. taichui was documented from animals (Kuntz and Chandler, 1956, El-Azazy et al., 2015).

2.3.2. Haplorchis pumilio (Looss, 1896) Looss, 1899

The original description of this species is based on adult specimens recovered from the small intestine of birds and mammals in Egypt (Looss, 1899). Its specific morphological feature (Fig. 4) for differentiation from other Haplorchis species is the size, shape, and number of spines on the ventral sucker (Chen, 1936, Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). H. pumilio has a circle of 32–40 I- or Λ-shaped sclerites (Fig. 4), 2.5–5.9 μm long, interrupted dorsally between latero-dorsal lobes of the ventral sucker, and a few to 9 small simple spines of various lengths on latero-dorsal and mid-dorsal lobes, respectively (Pearson, 1964, Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). H. taichui is differed from H. pumilio by the presence of a semi-lunar group of 12–16 long, crescentic, and hollow spines and a sinistral patch of very minute solid spines. Other species can be differed from H. pumilio by the presence of 15–21 hollow spines (H. parataichui), ventral sucker with four lobes and armed with spines (H. vanissimus), ventral sucker without lobes and spines interrupted mid-ventrally (H. paravanissimus), remarkably large ventral sucker (H. wellsi), or a ventral sucker smaller than the oral sucker (H. yokogawai and H. sprenti) (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982).

The snail host is Melania reiniana var. hitachiens (experimental) in Taiwan (Faust and Nishigori, 1926, Velasquez, 1982) and Melanoides (= Thiara) tuberculata (natural) in Taiwan (Lo and Lee, 1996, Wang et al., 2002), India (Umadevi and Madhavi, 2006), and Egypt (Khalifa et al., 1977). The second intermediate host is various species of freshwater or brackish water fish which belong to the Cyprinidae, Siluridae, and Cobitidae (Acanthogobius spp., Ambassis buruensis, Anabas spp., Astatotilapia desfontainesi, Barbus spp., Carrssius spp., Cyprinus spp., Esomus longimana, Gerris filamentosus, Glossogobius giurus, Hampala macrolepidota, Mugil capito, Ophicephalus striatus, Puntius binotatus, Therapon plumbeus, Teuthis javus, and Tilapia spp.) (Faust and Nishigori, 1926, Velasquez, 1982, Scholz et al., 1990, Scholz, 1991). Fish-eating birds and mammals, including dogs, cats, and humans, have been reported as the natural definitive hosts (Yamaguti, 1958, Yu and Mott, 1994). Experimental definitive hosts include mice, rats, hamsters, guinea pgs, rabbits, cats, and dogs (Faust and Nishigori, 1926, Chai et al., 2012, Nissen et al., 2013).

In Vietnam, where this parasite is highly endemic, raw or pickled fish, for example, slices of silver carp, sold in Vietnamese restaurants is a major source of infection (Dung et al., 2007). In Thailand and Laos, where fermentation is a traditional preservation method for freshwater fish, semi-fermented fish shortly after preparation is the major source of human infections with liver (Opisthorchis viverrini) and intestinal flukes (H. pumilio, H. taichui, and H. yokogawai) (Sukontason et al., 1998). Practically, local fish dishes, namely ‘lab-pla’ and ‘pla-som’ are important sources of infection (Radomyos et al., 1998, Sukontason et al., 1998, Onsurathum et al., 2016). H. pumilio is distributed in Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, South China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Egypt, Palestine, Iraq, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Malaysia (Witenberg, 1929, Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982, Chai et al., 2005a, Chai et al., 2009a, Chai et al., 2015b).

In Vietnam, the presence of H. pumilio, H. taichui, and H. yokogawai, has been confirmed in human infections in two communes of Nam Dinh Province, a northern part of Vietnam (Dung et al., 2007). The prevalence of small trematode eggs among riparian people in this area was 64.9% (399/615) (Dung et al., 2007). Later, in another commune in Nam Dinh Province, 22.7% (92/405) of household members were positive for small trematode eggs (De and Le, 2011). In Ninh Binh Province, 20.5% (381/1857) of commune people were positive for small trematode eggs (Hung et al., 2015). In Thailand, 12 human cases were first reported by Radomyos et al., 1983, Radomyos et al., 1984 through recovery of adult flukes. Thereafter, northern parts (including Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai Provinces) were found to be endemic areas of this fluke (Radomyos et al., 1998). In Laos, the presence of human H. pumilio infection was first documented by Chai et al. (2005b) based on recovery of adult flukes after praziquantel treatment and purging in Saravane Province and Vientiane Municipality. Later, in Saravane and Champasak Province, 796 and 247 adult specimens of H. pumilio were recovered in 5 and 5 patients, respectively (Chai et al., 2013a). In Savannakhet Province, a small proportion of recovered worms from 3 patients (80 among 7693 fluke specimens) were H. pumilio (Chai et al., 2007). In Luang Prabang Province, total 41 specimens of H. pumilio were recovered in 4 patients (Sohn et al., 2014). In Xieng Khouang Province, 2268 specimens of H. pumilio were harvested from 8 egg positive people (Chai et al., 2015b).

In Cambodia, no human cases have been detected until present; however, in 2014, a fish survey in Pursat Province, near the Lake Tonlesap, revealed the infection of freshwater fish with the metacercariae of H. pumilio (Chai et al., 2014a). In Southern China, the presence of human H. pumilio infection was documented in Guangdong Province in 1964; however, the background literature was not provided (T. Li et al., 2010). In Taiwan, H. pumilio was described in earlier times (Nishigori, 1924a, Faust and Nishigori, 1926); however, there have been no reports on human infections with this fluke. In the Philippines, human infections have never been documented. In Egypt, human H. pumilio infection was first documented by Khalifa et al. (1977) in a 9-year-old child passing diarrheic stools. In Korea, a 5-year old patient was found to be naturally infected with one specimen of H. pumilio, together with 841 Gymnophalloides seoi and 3 Gynaecotyla squatarolae specimens (Chung et al., 2011).

2.3.3. Haplorchis yokogawai (Katsuta, 1932) Chen, 1936

The original description of this species, Monorchotrema yokogawai, is based on adult flukes obtained in the small intestine of dogs and cats experimentally fed the metacercariae encysted in the mullet Mugil cephalus in Taiwan (Katsuta, 1932b). Its characteristic morphology (Fig. 4) differentiated from other Haplorchis species is the size, shape, and number of spines on the ventral sucker (Chen, 1936, Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). H. yokogawai has a small ventral sucker with its apex comprising a large ventral lobe armed with numerous tiny spines (Fig. 4) and a pair of large variable-sized sclerites ventro-dextrally, and 3 small lobes armed with tiny spines (Chen, 1936, Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). The total number of tiny spines on the ventral sucker was reported to be 70–74 (Katsuta, 1932b) but difficult to count. Ceca of H. yokogawai exceed the middle level of the testis (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). H. pumilio is morphologically similar to H. yokogawai but the latter has 23–32 I- or Λ-shaped sclerites on the ventral sucker (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). Other species can be differentiated by the presence of 12–16 or 15–21 large spines (H. taichui or H. parataichui, respectively), ventral sucker with four lobes and armed dorsal pocket (H. vanissimus), ventral sucker without lobes but with armed dorsal pocket with tiny spines interrupted mid-ventrally (H. paravanissimus), or remarkably large ventral sucker (H. wellsi) (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982).

The snail host is Melanoides (= Thiara) tuberculata or Stenomelania newcombi (Ito, 1964b, Velasquez, 1982). The second intermediate host is freshwater fish (Ambassis burunensis, Amphacanthus javus, Anabas testudineus, Boleophthalmus spp., Carassius auratus, Cirrhinus jullieni, Clarias fuscus, Cyclocheilichthys spp., Gambusia affinis, Gerris kapas, Hampala dispar, Hemiramphus georgii, Misgurnus spp. Mugil affinis, Mullus spp., Ophicephalus stratus, Pectinirostris spp., Puntioplites proctozysron, Puntius spp., and Tilapia nilotica) in Taiwan, the Philippines, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, South China, Malaysia, northern Thailand, India, Australia, and Egypt (Velasquez, 1982, Rim et al., 2008, Rim et al., 2013, Lobna et al., 2010, Chai et al., 2012, Chai et al., 2014a). Fish-eating birds and mammals, including dogs, cats, cattle, and humans, have been reported as the natural definitive hosts (Yamaguti, 1958, Yu and Mott, 1994). Experimental definitive hosts include mice, cats, dogs, and humans (Katsuta, 1932b).

In Thailand and Laos, consumption of semi-fermented fish shortly after preparation is the major risk for human infections with liver and intestinal flukes, including H. yokogawai (Sukontason et al., 1998). Notably, local fish dishes, ‘lab-pla’ and ‘pla-som’ are important sources of infection (Radomyos et al., 1998, Sukontason et al., 1998, Onsurathum et al., 2016). In the Philippines, local fish dishes called ‘kinilaw’ (freshwater fish seasoned only with salt and vinegar), ‘sabaw’ (boiling fish for several minutes), and ‘sugba’ (grilling over charcoal) are popularly consumed and seem to be the source of infection with Haplorchis spp. (Belizario et al., 2004). In Vietnam, raw or pickeld fish, for example, slices of silver carp, is an example of the infection source (Dung et al., 2007). H. yokogawai is now known to distribute in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia, Vietnam, South China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Hawaii, Egypt, India, Indonesia, and Australia (Velasquez, 1982, Yu and Mott, 1994, Chai et al., 2005a, Chai et al., 2009a, Chai et al., 2014a). Human infections are known in Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, the Philippines, and China.

In Thailand, human infection was first recorded by Manning and Lertprasert (1971), Manning et al. (1971), and then by Kliks and Tantachamrun (1974) and Radomyos et al. (1984). Subsequently, northern parts of Thailand (including Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai Provinces) were found to have human cases infected with H. yokogawai (Radomyos et al., 1998). In another study performed in Phrae Province, the prevalence of H. yokogawai among 87 worm-recovery cases was 2.3%, much lower than 64.4% of H. taichui (Pungpak et al., 1998). In Laos, the presence of human infection was first documented by Chai et al. (2005a) based on adult flukes recovered after praziquantel treatment and purging. Low grade infections were subsequently detected in Savannakhet Province (Chai et al., 2007). In another study in Savannakhet and Saravane Province, adult specimens were recovered from a small number of patients (Sayasone et al., 2009). In Phongsali Province, Haplorchis spp., predominantly H. taichui and a small number of H. yokogawai were recovered from local people (Chai et al., 2010). Similarly, in Luang Prabang Province, adults were recovered in 5 of 10 patients treated with praziquantel (Sohn et al., 2014). In Vietnam, the presence of H. yokogawai, together with H. pumilio, H. taichui, and other intestinal flukes, has been first confirmed in human infections in two communes of Nam Dinh Province (Dung et al., 2007).

In the Philippines, human infections were described by Africa et al. (1940) from 16 of 33 human autopsies. Later, however, the presence of this parasite has seldom been documented. In Southern China, the presence of human H. pumilio infection was first documented in Guangdong Province in 1979; however, the literature background was not provided (T. Li et al., 2010). In Taiwan where H. yokogawai was originally discovered, the possibility of human infection was proved by a human experimental infection (Katsuta, 1932b); however, no reports are available on natural human infections. In Cambodia, a recent fish survey in Pursat Province, near the Lake Tonlesap, revealed the infection of freshwater fish (Puntioplites falcifer) with the metacercariae of H. yokogawai (Chai et al., 2014a); however, no human infection cases have been detected.

2.3.4. Haplorchis vanissimus (Africa, 1938) Yamaguti, 1958

The original description of this species is based on adult flukes recovered at an autopsy of a Filipino (Africa, 1938). It was morphologically redescribed by Pearson (1964) in Australia. Its specific morphology includes the presence of four armed lobes and an armed dorsal pocket on the ventral sucker with spines continuous across the width of ventral face (Pearson, 1964, Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). It is readily distinguished from other species of Haplorchis (H. pumilio, H. parapumilio, H. taichui, H. parataichui, H. yokogawai, H. wellsi, and H. sprenti) by the form and spination of the ventral sucker (Pearson, 1964, Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982). The most closely resembled species is H. paravanissimus which has a simple ventral sucker without obvious lobes and the presence of minute spines interrupted mid-ventrally (Pearson and Ow-Yang, 1982).

The snail host has not been confirmed. Freshwater fish probably play the role of the second intermediate hosts (Yu and Mott, 1994). In Australia, fish-eating birds were found to be natural definitive hosts (Pearson, 1964). No further human infections have been documented. The practical mode of human infection or the type of fish dish involved is unknown. The geographical distribution of this fluke is confined to the Philippines and Australia.

2.4. Pygidiopsis

2.4.1. Pygidiopsis summa Onji and Nishio, 1916

The original description of this species is based on adult flukes recovered from dogs fed brackish water fish infected with the metacercariae in Japan (Onji and Nishio, 1916). Its characteristic morphologies include a small concave body, median location of the ventral sucker, unique morphology of the ventrogenital apparatus (having two groups of spines on the gonotyl; 5–6 right side and 7–9 left side), side-by-side location of the two testes (Chai et al., 1986a), and small pyriform eggs with no distinct muskmelon patterns on the shell (Lee et al., 1984a). In P. genata, the ventral sucker is median and globular in shape, whereas in P. summa, it is slightly submedian and transversely elliptical; the former has only one group of spines on the gonotyl whereas the latter has two groups of spines (Chai et al., 1986a).

The life cycle of P. summa has been elucidated by Ochi (1931) in Yamaguti, Hiroshima, and Okayama Prefectures, Japan. The snail host is the brackish water snail Tympanotonus microptera (= Cerithidea fluviatilis) in Korea (Chai, unpublished observation) and in Japan (Ochi, 1931). The metacercariae are detected in the gill and muscle of the mullets (Mugil cephalus and Liza menada), redlip mullets (Chelon haematocheilus), and gobies (Acanthogobius flavimanus) (Onji and Nishio, 1916, Chun, 1963, Sohn et al., 1994a, Kim et al., 2006, Sohn, 2009, Cho et al., 2012). Natural infections of domestic or feral cats (Eom et al., 1985b, Sohn and Chai, 2005, Shin et al., 2015) and raccoon dogs (E.H. Shin et al., 2009) have been reported. Experimental hosts include rats, cats, and dogs (Ochi, 1931, Chun, 1963).

Humans are contracted by this fluke through consumption of raw or undercooked brackish water fish, in particular, the mullet, goby, and perch. It is now known to distribute in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam (Yokogawa et al., 1965, Seo et al., 1981b, Vo et al., 2008, Sohn et al., 2016) (Table 4). Human infections with P. summa were first reported by detection of eggs in human feces in Japan (Takahashi, 1929b). Subsequently, adult flukes were identified from humans in Japan (Yokogawa et al., 1965) and Korea (Seo et al., 1981b). In Korea, eight people residing in a salt-farm village of Okku-gun, Jeollabuk-do who habitually ate the raw flesh of the mullet were proved to be infected with P. summa through recovery of adult flukes after bithionol treatment and purging (Seo et al., 1981b). In another coastal area of South Korea, 18 heterophyid egg-positive people were found to be mixed-infected with P. summa and Heterophyes nocens (Chai et al., 1994b). Eighteen more cases were detected in another coastal area, Muan-gun, Jeollanam-do, from whom total 703 adult specimens of P. summa were recovered (Chai et al., 1997). Five more cases were detected in Buan-gun, Jeollabuk-do, and total 1732 adult specimens were collected (Chai et al., 1998). Subsequently, more wide distribution of this parasite has been found along the western and southern coastal islands of South Korea, although the egg positive rate was remarkably higher for Heterophyes nocens (11.0%) than that for P. summa (1.2%) (Chai et al., 2004).

Table 4.

Other heterophyid species infecting humans around the world.

| Species | Human infection | Country/region | First reporter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pygidiopsis summa | Yes | Korea, Japan, Vietnam | Onji and Nishio (1916) |

| Pygidiopsis genata | Yes | Egypt, Palestine, Rumania, Iran, Ukraine, Tunisia, Israel, Kuwait, Philippines | Looss (1907) |

| Heterophyopsis continua | Yes | Korea, Japan, China, Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirate | Onji and Nishio (1916) |

| Stellantchasmus falcatus | Yes | Korea, Japan, Philippines, USA (Hawaii), Thailand, Vietnam, China, Taiwan, Laos, Australia, India, Iran, Palestine | Onji and Nishio (1916) |

| Centrocestus formosanus | Yes | Taiwan, China, Japan, Philippines, India, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Turkey, Croatia, USA, Mexico, Costa Rica, Colombia, Brazil | Nishigori (1924b) |

| Centrocestus armatus | Ye | Japan, Korea | Tanabe (1922) |

| Centrocestus cuspidatus | Yes | Egypt, Taiwan, China, Kuwait, Tunisia | Looss in 1896 (Looss, 1902) |

| Centrocestus kurokawai | Yes | Japan | Kurokawa (1935) |

| Stictodora fuscata | Yes | Korea, Japan, Kuwait | Onji and Nishio (1916) |

| Stictodora lari | Yes | Korea, Japan, Australia, Russia, Vietnam | Yamaguti (1939) |

| Procerovum varium | Yes | Japan, China, Philippines, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Australia, India, Korea | Onji and Nishio (1916) |

| Procerovum calderoni | Yes | Philippines, China, Egypt | Africa and Garcia (1935) |

| Acanthotrema felis | Yes | Korea | Sohn et al., 2003a, Sohn et al., 2003b |

| Apophallus donicus | Yes | USA, Canada, Europe | Skrjabin and Lindtrop in 1919 (Price, 1931) |

| Ascocotyle longa | Yes | USA, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Panama, Peru, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Romania, Egypt, Georgia, Israel, Turkey | Ransom (1920) |

| Cryptocotyle lingua | Yes | UK, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Russia, North America, Japan, Greenland | Creplin in 1825 (Stunkard, 1930) |

2.4.2. Pygidiopsis genata Onji and Nishio, 1916

The original description of this species is based on adult flukes recovered from the small intestine of a pelican in Cairo, Egypt (Looss, 1907, Ransom, 1920). Its characteristic morphologies include the presence of 16 small spines on the oral sucker which are seen only in fresh preparations, pear-shape or triangular body, short ceca terminating at the level of the ovary, and a small oval gonotyl on the ventrogenital sac (Witenberg, 1929). In P. summa, the body is ovoid to oval, with relatively long ceca terminating near the anterior border of testes, and two small oval gonotyl armed with spines (Chai et al., 1986a).

The snail host is Melanoides tuberculata (Youssef et al., 1987b) and Melanopsis costata (Dzikowski et al., 2004). The second intermediate host is brackish water fish (including Barbus canis, Mugil capito, and Tilapia spp.) (Witenberg, 1929, Mahdy and Shaheed, 2001, Ibrahim and Soliman, 2010, Lobna et al., 2010), and experimentally Gambusia affinis and Tilapia nilotica (Youssef et al., 1987b). Natural definitive hosts include wolves, cats, dogs, foxes, shrews, rats, pelicans, kites, ducks, and cormorants (Looss, 1907, Witenberg, 1929, Kuntz and Chandler, 1956, Dzikowski et al., 2004). Experimental hosts include mice, rats, and hamsters (Mansour et al., 1981).

The mode of human infection is probably the consumption of raw or undercooked brackish water fish. Human infections were unknown before 1987 when eggs were detected in human fecal examinations from Maryut area on Manzala Lake, Egypt; the egg positive rate was 2.7% (2/73) (Youssef et al., 1987a). Although the adult flukes were not identified, the eggs of P. genata were morphologically well discriminated from those of Heterophyes heterophyes (Youssef et al., 1987a). The existence of human infections in other countries, including Rumania, Iran, Palestine, Ukraine, Tunisia, Israel, and Kuwait should be determined. After its discovery, P. genata was found in pelicans in Romania (Ciurea, 1924), dogs in China (it should be verified whether the species was actually P. genata or a related species P. summa) (Faust and Nishigori, 1926), and dogs and cats (both hosts were experimentally infected) in the Philippines (Africa and Garcia, 1935, Africa et al., 1940), and a Persian wolf, dogs, and cats in Palestine (Witenberg, 1929). In Egypt, this parasite has been found from cats, dogs, foxes, shrews, rats, kites, and ducks (Kuntz and Chandler, 1956). Recently, this parasite was recovered from birds in Israel (Dzikowski et al., 2004) and stray cats in Kuwait (El-Azazy et al., 2015).

2.5. Heterophyopsis

2.5.1. Heterophyopsis continua (Onji and Nishio, 1916) Price, 1940

The original description of this parasite is based on specimens recovered from experimental cats fed the mullet harboring the metacercariae in Japan (described under the name Heterophyes continuus) (Onji and Nishio, 1916). Tubangui and Africa (1938) created a new genus Heterophyopsis. Yamaguti (1939) also created a new genus Pseudoheterophyes and assigned H. continuus to this genus. However, Africa et al. (1940) and Price (1940) synonymized Pseudoheterophyes with Heterophyopsis and thereafter, the status of the genus Heterophyopsis has been settled. Its characteristic morphology includes the elongate body, genital sucker located separately at a slightly postero-sinistral position from the ventral sucker, and two obliquely tandem testes (Seo et al., 1984a, Chai and Lee, 2002). The most similar genus Heterophyes is different from Heterophyopsis in having a genital sucker closely adjacent with the ventral sucker, whereas the genital sucker is much separated from the ventral sucker; the former has a ovoid to elliptical or pyriform body but the latter has an elongated body (Chai, 2007).

The first intermediate host is yet unknown. Metacercariae encyst in the perch Lateolabrax japonicas, goby Acanthogobius flavimanus, Konosirus (= Clupanodon) punctatus, and Conger myriaster (Chun, 1960b, Seo et al., 1984a, Sohn et al., 1994a, Sohn et al., 2009a, Chai et al., 2005a, Kim et al., 2006, Cho et al., 2012). Metacercariae were also detected in the sweetfish (P. altivelis), gobies (Boleophthalmus pectinirostris and Scartelaos sp.), mullets (M. cephalus), and groupers (Epinephelus bleekeri and E. coioides) (Sohn et al., 2005, Kim et al., 2006, Vo et al., 2008, Vo et al., 2011, Thanh et al., 2009, Chai et al., 2009a). Natural definitive hosts are domestic or feral cats (Eom et al., 1985b, Sohn and Chai, 2005, Schuster et al., 2009, Chai et al., 2013c), dogs (Yamaguti, 1958), ducks (Onji and Nishio, 1916), and sea-gulls (Yamaguti, 1939). Experimental definitive hosts include cats (Onji and Nishio, 1916), dogs (Chun, 1960b, Seo et al., 1984a) and domestic chicks (Hong et al., 1990, Shin et al., 2015).