Abstract

Natural honey in spite of its usefulness is known to contain certain microorganisms. In the present study, we describe a case of Acanthamoeba keratitis after using topical honey administered by a traditional medicine therapist. A 32-year-old male came with red eye and blurred vision. The pain and other symptoms became more severe after the 1st week, with appearance of radial perineuritis at the cornea. A repeated interview revealed that 1 week before appearance of ocular symptoms, the patient had instilled a drop of natural honey in his left eye. Confocal microscopic cornea imaging demonstrated cyst and trophozoite of Acanthamoeba in the corneal stroma.

Keywords: Acanthamoeba keratitis, cornea ulcer, honey

Introduction

Natural honey is considered to have various therapeutic effects in different religious, traditional, and naturopathic medicine.[1] There are some published articles about beneficial effects of topical use of honey in ophthalmology.[2,3] Honey in spite of its usefulness is known to contain certain microorganisms potentially considered a reservoir for microbes. In addition, it easily gets contaminated during its production process by bees and microorganisms introduced into honey by man's activities, including equipment, containers, and wind and dust.[4,5] The contaminant microorganisms in natural honey can potentially be unsafe if the natural unprocessed honey is used for therapeutic purposes.

In this article, we describe a case of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) after instillation of topical natural honey drop. The signs and symptoms of the disease improved after treatment for AK. The only possible risk factor in this patient was instillation of topical natural honey drop prescribed by the traditional therapist. To the best of our knowledge, this case is the first report of natural honey-induced AK. The emphasis of our report is topical use of unsterile traditional remedies, such as honey, which can be a risk factor for infectious keratitis with uncommon microorganisms, including Acanthamoeba.

Case Report

A 32-year-old male came to our ophthalmology emergency department due to red eye, photophobia, and blurred vision in his left eye for 1 week.

He did not have any notable condition in his medical or ocular history at the first visit. He did not recall any trauma to the eyes, had never used contact lenses, and had no history of swimming for at least a year.

The best-corrected visual acuity at the first visit was 20/20 and 20/40 in the right and left eyes, respectively. Slit-lamp examination revealed conjunctival hyperemia, ciliary injection, and cornea epithelial irregularity in his left eye.

Treatment initiated with topical lubricant and antibiotic drops with presumed diagnosis of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. After 1 week, the symptoms of decreased vision and pain exacerbated, and in slit-lamp evaluation, a dendritic form cornea epithelial defect became visible.

The treatment plan changed to topical acyclovir 3% ointment every 5 h for the treatment of possible epithelial herpes infection. The pain became more severe after the 1st week, and conjunctival hyperemia was worse. No therapeutic response was observed after initiating acyclovir.

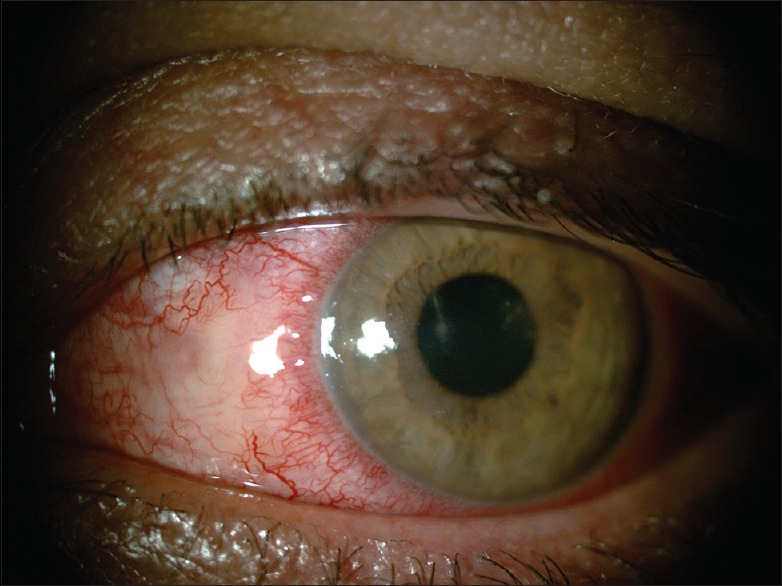

A watchful highly magnified slit-lamp examination of the cornea revealed radial perineuritis at the cornea [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Natural honey-induced Acanthamoeba keratitis. Stromal haziness and radial perineuritis in the left eye

A repeated comprehensive meticulous interview revealed that 1 week before appearance of ocular symptoms, the patient had instilled a drop of natural honey in the left eye according to the prescription of a traditional medical therapist to improve the strength of his eyes. He told that he was reluctant to talk about utilizing traditional medicine with the visiting doctors, with fear of being blamed to follow obsolete directions, and supposed that this event was irrelevant to his current eye problem.

We did not have disclosed any risk factor for AK at first visit, but after history of use of natural honey in the eyes and radial perineuritis at the cornea, with high suspicion for AK, a scanning confocal microscopic cornea imaging was requested.

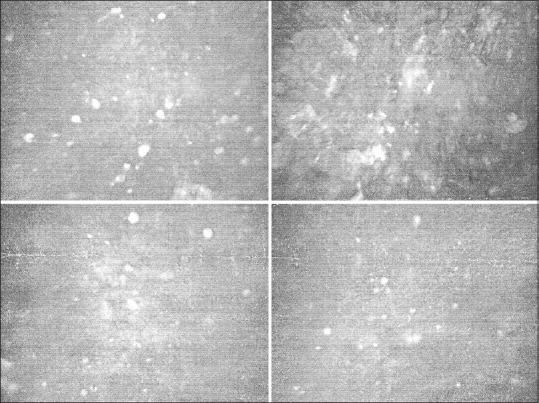

The confocal scan of the left cornea revealed areas of hyperreflectivity with infiltration of inflammatory cells and many hyperreflective cystic structures measuring up to 19.3 μm together with hyperreflective trophozoite like structures measuring up to 31.3 μm [Figure 2]. According to the clinical and imaging data, the patient underwent treatment for AK.

Figure 2.

Natural honey-induced Acanthamoeba keratitis. Multiple Acanthamoeba cysts and trophozoites in the confocal scan of the left cornea

Treatment with topical polyhexamethylene biguanide 0.02% and chlorhexidine 0.02% drops hourly during waking hours and every 4 h during sleep time for the first 3 days was initiated. Thereafter, the treatment sustained with the frequency of every 4 h for 1 week and subsequently tapered to every 6 h and continued for 1 month.

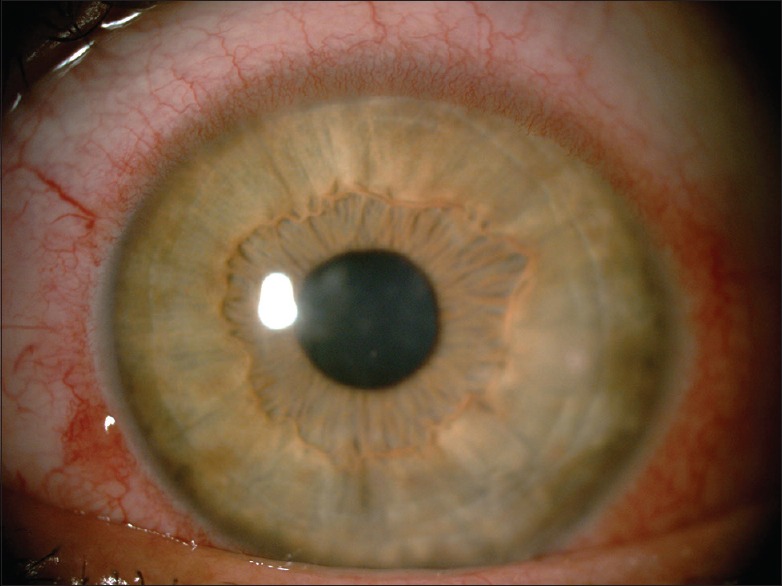

The topical treatment targeted at Acanthamoeba led to gradual improvement of the condition [Figure 3]. There was no recurrence during 6-month follow-up after cessation of therapy.

Figure 3.

Slit-lamp photo of the eye on posttreatment on day 21 showing a clinical improvement during the treatment

Discussion

AK, comprising <5% of microbial keratitis associated with contact lens related, is a relatively rare microbial infection of the cornea that can result in significant morbidity, including vision loss.[6]

The first case of AK and Acanthamoeba uveitis associated with fatal meningoencephalitis was described in 1974.[7] Since then, many authors have published their experience with this disease. Today, several predisposing factors for AK, such as contact lens wear, overnight orthokeratology for myopia, water exposure, and certain contact lens solutions, have been identified.[8]

AK is usually described to be associated with contact lens. However, in most developing countries where contact lenses are not popular, trauma and other risk factors are considered as important predisposing factors for AK, suggesting that the disease occurs even without associated use of contact lens.[9]

In this report, our patient did not have any notable condition as a predisposing factor in his medical or ocular history at the first visit. He did not recall any trauma to the eyes, had never used contact lenses, and had no history of swimming for at least a year anywhere. In our case, we did not disclose any predisposing factor for AK except the use of natural honey eye drop as a potential reservoir of many microorganisms, including Acanthamoeba in the eyes.

Although the use of natural products, including honey as alternative, complementary, or traditional medicine, has regained in different communities, the rules and regulations to control traditional practitioners are not strict and pervasive in different countries.[10]

Conclusion

We identified new predisposing factors of AK that may aid in early diagnosis of AK with increased suspicion for Acanthamoeba infection, particularly before culture results, and in settings where a microbiological laboratory is unavailable. Finally, because the natural honey drop is an unsterile solution loaded with different microorganisms, spores, and cysts, it is not sensible to use the natural unsterile form of this substance in ophthalmology.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ediriweera ER, Premarathna NY. Medicinal and cosmetic uses of Bee's honey – A review. Ayu. 2012;33:178–82. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.105233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cernak M, Majtanova N, Cernak A, Majtan J. Honey prophylaxis reduces the risk of endophthalmitis during perioperative period of eye surgery. Phytother Res. 2012;26:613–6. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majtanova N, Vodrazkova E, Kurilova V, Horniackova M, Cernak M, Cernak A, et al. Complementary treatment of contact lens-induced corneal ulcer using honey: A case report. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2015;38:61–3. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinson VG, Danforth BN, Minckley RL, Rueppell O, Tingek S, Moran NA. A simple and distinctive microbiota associated with honey bees and bumble bees. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:619–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olaitan PB, Adeleke OE, Ola IO. Honey: A reservoir for microorganisms and an inhibitory agent for microbes. Afr Health Sci. 2007;7:159–65. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2007.7.3.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg P, Kalra P, Joseph J. Non-contact lens related Acanthamoeba keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65:1079–86. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_826_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones DB, Visvesvara GS, Robinson NM. Acanthamoeba polyphagakeratitis and Acanthamoeba uveitis associated with fatal meningoencephalitis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1975;95:221–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mascarenhas J, Lalitha P, Prajna NV, Srinivasan M, Das M, D'Silva SS, et al. Acanthamoeba, fungal, and bacterial keratitis: A comparison of risk factors and clinical features. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Garg P, Rao GN. Patient characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment of non-contact lens related Acanthamoeba keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1103–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.10.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Staden AM, Joubert GB. Interest in and willingness to use complementary, alternative and traditional medicine among academic and administrative university staff in Bloemfontein, South Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2014;11:61–6. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v11i5.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]