Abstract

Background

Prayer is amongst the oldest and most widespread interventions used with the intention of alleviating illness and promoting good health. Given the significance of this response to illness for a large proportion of the world's population, there has been considerable interest in recent years in measuring the efficacy of intercessory prayer for the alleviation of ill health in a scientifically rigorous fashion. The question of whether this may contribute towards proving or disproving the existence of God is a philosophical question lying outside the scope of this review of the effects of prayer. This revised version of the review has been prepared in response to feedback and to reflect new methods in the conduct and presentation of Cochrane reviews.

Objectives

To review the effects of intercessory prayer as an additional intervention for people with health problems already receiving routine health care.

Search methods

We systematically searched ten relevant databases including MEDLINE and EMBASE (June 2007).

Selection criteria

We included any randomised trial comparing personal, focused, committed and organised intercessory prayer with those interceding holding some belief that they are praying to God or a god versus any other intervention. This prayer could be offered on behalf of anyone with health problems.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently and analysed it on an intention to treat basis, where possible. We calculated, for binary data, the fixed‐effect relative risk (RR), their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

Ten studies are included in this review (7646 patients). For the comparison of intercessory prayer plus standard care versus standard care alone, overall there was no clear effect of intercessory prayer on death (5 RCTs, n=3389, random‐effects RR 1.00 CI 0.74 to1.36). For general clinical state there was also no significant difference between groups (5 RCTs, n=2705, RR intermediate or bad outcome 0.98 CI 0.86 to 1.11). Four studies found no effect for re‐admission to Coronary Care Unit (4 RCTs, n=2644, RR 1.00 CI 0.77 to 1.30).Two other trials found intercessory prayer had no effect on re‐hospitalisation (2 RCTs, n=1155, RR 0.93 CI 0.71 to 1.22).

Authors' conclusions

These findings are equivocal and, although some of the results of individual studies suggest a positive effect of intercessory prayer, the majority do not and the evidence does not support a recommendation either in favour or against the use of intercessory prayer. We are not convinced that further trials of this intervention should be undertaken and would prefer to see any resources available for such a trial used to investigate other questions in health care.

Plain language summary

Intercessory Prayer for the alleviation of ill health

Intercessory prayer is one of the oldest and most common interventions used with the intention of alleviating illness and promoting good health. It is practised by many faiths and involves a person or group setting time aside to petition God (or a god) on behalf of another who is in some kind of need. This review examines whether there is a difference in outcome for people who are prayed for by name whilst ill, or recovering from an illness or operation, and those who are not. Both groups of people still received their usual treatment for their illness. Ten trials were found which randomised a total of 7646 people. The majority of these compared prayer (for someone to become well) plus treatment as usual with treatment as usual without prayer. One trial had two prayer groups, comparing participants who knew they were being prayed for with those who did not. Another trial prayed retroactively, randomising people a month to 6 years after they were admitted to hospital. Each trial had people with different illnesses. These included leukaemia, heart problems, blood infection, alcohol abuse and psychological or rheumatic disease. In one trial people were judged to be at high or low risk of death and placed in relevant groups.

Overall, there was no significant difference in recovery from illness or death between those prayed for and those not prayed for. In the trials that measured post‐operative or other complications, indeterminate and bad outcomes, or readmission to hospital, no significant differences between groups were also found. Specific complications (cardiac arrest, major surgery before discharge, need for a monitoring catheter in the heart) were significantly more likely to occur among those in the group not receiving prayer. Finally, when comparing those who knew about being prayed for with those who did not, there were fewer post‐operative complications in those who had no knowledge of being prayed for.

The authors conclude that due to various limitations in the trials included in this review (such as unclear randomising procedures and the reporting of many different outcomes and illnesses) it is only possible to state that intercessory prayer is neither significantly beneficial nor harmful for those who are sick. Further studies which are better designed and reported would be necessary to draw firmer conclusions.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings 1. INTERCESSORY PRAYER (CONTEMPORANEOUS ) versus STANDARD CARE.

| INTERCESSORY PRAYER (CONTEMPORANEOUS ) versus STANDARD CARE for various illnesses | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with various illnesses Settings: in hospital Intervention: INTERCESSORY PRAYER (CONTEMPORANEOUS ) versus STANDARD CARE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | INTERCESSORY PRAYER (CONTEMPORANEOUS ) versus STANDARD CARE | |||||

| Death by end of trial | Medium risk population | RR 0.72 (0.38 to 1.38) | 3389 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 96 per 1000 | 69 per 1000 (36 to 132) | |||||

| Clinical state: 1. Improved/not improved: intermediate or bad outcome | Medium risk population | RR 0.98 (0.86 to 1.11) | 2705 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 269 per 1000 | 264 per 1000 (231 to 299) | |||||

| Clinical state: 2. Significant complications (readmission to CCU) | Medium risk population | RR 1 (0.77 to 1.3) | 2644 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 84 per 1000 | 84 per 1000 (65 to 109) | |||||

| Leaving the study early | Medium risk population | RR 0.75 (0.43 to 1.31) | 3446 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 2 per 1000 | 2 per 1000 (1 to 3) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidance High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Randomisation not well described

2 Considerable heterogeneity

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings 2. INTERCESSORY PRAYER (RETROSPECTIVE) versus STANDARD CARE.

| INTERCESSORY PRAYER (RETROSPECTIVE) versus STANDARD CARE for blood stream infections | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with blood stream infections Settings: in hospital Intervention: INTERCESSORY PRAYER (RETROSPECTIVE) versus STANDARD CARE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | INTERCESSORY PRAYER (RETROSPECTIVE) versus STANDARD CARE | |||||

| Death by end of trial | Medium risk population | RR 0.93 (0.84 to 1.03) | 3393 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | ||

| 302 per 1000 | 281 per 1000 (254 to 311) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidance High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Randomisation not well described

2 Very rare type of study

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings 3. AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus STANDARD CARE.

| AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus STANDARD CARE for scheduled to receive non‐emergency CABG | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with scheduled to receive non‐emergency CABG Settings: in hospital Intervention: AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus STANDARD CARE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus STANDARD CARE | |||||

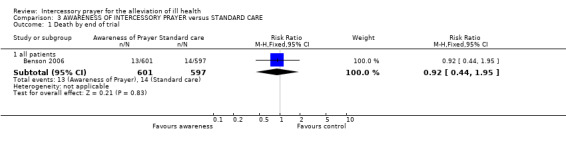

| Death by end of trial | Medium risk population | RR 0.92 (0.44 to 1.95) | 1198 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | ||

| 24 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (11 to 47) | |||||

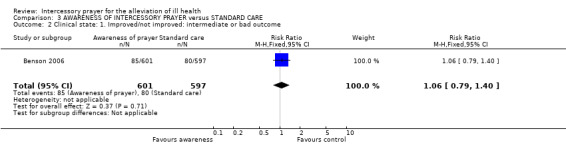

| Clinical state: 1. Improved/not improved: intermediate or bad outcome | Medium risk population | RR 1.06 (0.79 to 1.4) | 1198 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | ||

| 134 per 1000 | 142 per 1000 (106 to 188) | |||||

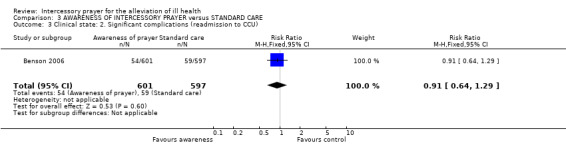

| Clinical state: 2. Significant complications (readmission to CCU) | Medium risk population | RR 0.91 (0.64 to 1.29) | 1198 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | ||

| 99 per 1000 | 90 per 1000 (63 to 128) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidance High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Randomisation not well described

2 Very rare type of study

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings 4. AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus INTERCESSORY PRAYER.

| AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus INTERCESSORY PRAYER for people who are ill | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with scheduled to receive non‐emergency CABG Settings: in hospital Intervention: AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus INTERCESSORY PRAYER | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus INTERCESSORY PRAYER | |||||

| Death by end of trial | Medium risk population | RR 0.82 (0.4 to 1.68) | 1205 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | ||

| 27 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (11 to 45) | |||||

| Clinical state: 1. Improved/not improved: intermediate or bad outcome | Medium risk population | RR 0.78 (0.6 to 1.02) | 1205 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | ||

| 181 per 1000 | 141 per 1000 (109 to 185) | |||||

| Clinical state: 2. Significant complications (readmission to CCU) | Medium risk population | RR 0.95 (0.67 to 1.36) | 1205 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | ||

| 94 per 1000 | 89 per 1000 (63 to 128) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidance High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Randomisation not well described

2 Very rare type of study

Background

Description of the intervention

Prayer is amongst the oldest and most widespread interventions used with the intention of alleviating illness and promoting good health (McCaffrey 2004; Barnes 2004). Recent years have seen considerable interest in the beneficial effects of religious belief and communal religious involvement on health outcomes (Koenig 2000). Research has been done to investigate the effect for the patient of the complex matter of belonging to a religious tradition and undertaking its distinctive practices. One aspect of this is offering and receiving intercessory prayers for the sick. In this study we consider effect for the patient of intercessory prayer being offered on their behalf, separated from the question of his or her religious affiliation.

Prayer, defined as the "solemn request or thanksgiving to God or object of worship" (OED 1989), is an ancient and widely used intervention. There are many different forms of intercessory prayer; it is found in highly developed belief systems and is also practised sporadically by individuals in times of need, relatively free from formal involvement in organised religion. Indeed, one plausible derivation of the word ‘God’ and its Indo‐European cognates is from a root meaning "the one who is called upon" (OED 1989). Prayer has relation to other spiritual disciplines, including meditation and thanksgiving. This review focuses on intercessory prayer which, for the purposes of this study, involves a person or group setting time aside to petition God (or a god) on behalf of another person who is in some kind of need. Intercessory prayer is organised, regular, and committed, and those who practise it will hold some committed belief that they are praying to God (or a god).

How the intervention might work

The mechanism(s) by which prayer might work is unknown and hypotheses about this will depend to a large extent on religious beliefs. This review seeks to answer the question of effect not mechanism and it does not seek to answer the question of whether any effects of prayer confirm or refute the existence of God. In determining the direction of any effect, it is important to note that a religious believer may suggest that the nature of divine intervention could be subtle ‐ more subtle, indeed, than is likely to be revealed by the results of a randomised trial. Significance could be attached, for instance, to the question of whether a person has a ‘good death’ (approached with courage and having achieved a sense of peace) or a ‘bad death’, even though the ‘clinical outcome’ may be measured and recorded as the same. We nonetheless take the stand that claims for intercessory prayer for the sick which go beyond such subtleties can be subject to empirical testing and, potentially, proof and so, whilst not wishing to belittle such distinctions (as, for instance, between a ‘good’ and a ‘bad’ death), we will test the starker claims that are made for prayer which are of a measurable, directly clinical nature.

Why it is important to do this review

As with all systematic reviews, this review is necessary to bring together the relevant research evidence, to present that evidence and to seek to resolve uncertainties about the effects of intercessory prayer. We note that the results of this review will be of interest to those who are involved with the ‘debate about God’ ‐ both religious believers and atheists ‐ but these results cannot directly stand as ‘proof’ or ‘disproof’ of the existence of God. The extent and manner to which God’s existence can be determined by reference to events in the world is one of the most significant, and ancient, questions in theology‐philosophy, and is contested. (For a recent survey see Denys Turner (Turner 2004)). One strand of discussion, for instance, concentrates on the existence of the world rather than any given state of affairs within it. In the words of Ludwig Wittgenstein, ‘It is not how things are in the world that is mystical, but that it exists' (Wittgenstein 1974). We do not, therefore, seek to pose or answer any questions about the existence of God with this reviews. There are several challenges when assessing the results of randomised trials of prayer. There are potential problems with trial methodology. For example, ‘contamination’. The ‘control group’ of patients who are not prayed for within the trial may, nonetheless, be the subject of prayers offered by others. For instance, a sizeable number of people ‐ particularly those within religious orders and comparable fraternities ‐ are devoted to the practice of praying for all who are in need. Nonetheless, those who pray for the sick do so out of a conviction that their contribution makes a difference. They do not refrain from praying out of the consideration that someone, somewhere else, may also be praying. This conviction and its consequent practices are sufficiently deeply engrained as to make such studies worthwhile, since this background level of prayer should be evenly distributed to the two intervention groups through the process of random allocation.

A second consideration is the question of whether it makes any sense to speak of a ‘blind’ trial if the action (or not) of the intervention is determined by a putative divine agent. Most of the world’s religious traditions, from within which the prayer under consideration here would be offered, understand God to be omniscient, that is, all‐knowing. Therefore there could be no concealment of allocation nor concealment of the group to which a person has been allocated before God, who might choose to influence the patient outcomes because of or instead of the allocation. However, these are theological questions, and this review proceeds on scientific principles in that it is a widely held belief that intercessory prayer is beneficial for those who are unwell because God directs the outcome of those for whom prayers are offered differently from those for whom it is not. As noted above, we are not seeking to assess whether God is or is not the agent of action for prayer but, by using the same study designs used to test other interventions in healthcare we will assess the effects of the intervention. For this reason we also exclude from consideration such theological considerations as the injunction "Do not put the Lord your God to the test" (Deuteronomy 6:16) or questions as to whether God generally veils his presence from observation: in the words of the philosopher GF Hegel, "God does not offer himself for observation" (Hegel 2008).

Objectives

1. To evaluate the effects of intercessory prayer as an intervention for those with health problems.

2. If possible, to undertake sensitivity analyses to assess the specific efficacy of prayer for (i) people suffering from life threatening conditions and (ii) people suffering from less serious health problems.

3. In addition, we compared the outcomes of well 'blinded' and poorly 'blinded' studies in order to investigate the extent to which knowing that one is being prayed for influences the primary outcome of recovery.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials. Where a trial was described as "double blind" but it was only implied that the study was randomised, if the participants' demographic details in each group were similar, we included it. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, in which treatment allocation was not concealed, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

We included any person with a physical or mental health problem irrespective of age, gender, or race.

Types of interventions

1. Intercessory prayer: routine care (see below) plus personal, focused, committed, and organised intercessory prayer on behalf of another.

2. Routine care: the relevant medical and non‐medical care normally given to people diagnosed with their particular illness in the setting in which the trial was done.

Types of outcome measures

We grouped outcomes into those measured in the short term (up to six weeks), medium term (six weeks to six months) and long term (six months and more).

Primary outcomes

1. Death ‐ any cause

2. Clinical state ‐ No important change in clinical state (as defined by individual studies)

3. Service outcomes ‐ Hospitalisation

4. Quality of life ‐ No clinically important change in quality of life

5. Satisfaction with treatment ‐ Leaving the studies early

Secondary outcomes

1. Death 1.1 Suicide 1.2 Due to illness 1.3 Natural

2. Clinical state 2.1 Course of illness (as defined by individual studies) 2.2 Complications (as defined by individual studies) 2.3 Medication use (as defined by individual studies) 2.4 Average endpoint scores in clinical state (as defined by individual studies)

3. Service outcomes 3.1 Number of days in hospital 3.2 Number of days to discharge 3.3 Re‐admission

4. Quality of life 4.1 Average endpoint quality of life score 4.2 Average change in quality of life scores 4.3 No clinically important change in specific aspects of quality of life 4.4 Average endpoint specific aspects of quality of life 4.5 Average change in specific aspects of quality of life

5. Satisfaction with treatment 5.1 Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment 5.2 Recipient of care average satisfaction score 5.3 Recipient of care average change in satisfaction scores 5.4 Carer not satisfied with treatment 5.5 Carer average satisfaction score 5.6 Carer average change in satisfaction scores

6. Mental state 6.1 No clinically important change in general mental state 6.2 Not any change in general mental state 6.3 Average endpoint general mental state score 6.4 Average change in general mental state scores 6.5 No clinically important change in specific symptoms 6.6 Not any change in specific symptoms 6.7 Average endpoint specific symptom score 6.8 Average change in specific symptom scores

7. Behaviour 7.1 No clinically important change in general behaviour 7.2 Average endpoint general behaviour score 7.3 Average change in general behaviour scores 7.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of behaviour 7.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of behaviour 7.6 Average change in specific aspects of behaviour

8. Adverse effects 8.1 Clinically important general adverse effects 8.2 Average endpoint general adverse effect score 8.3 Average change in general adverse effect scores 8.4 Clinically important specific adverse effects 8.5 Average endpoint specific adverse effects 8.6 Average change in specific adverse effects

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update we searched the following electronic databases:

a. AMED, CINAHL, EMBASE and MEDLINE on Ovid (June 2007) were searched using Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for randomised controlled trials (see Group search strategy) combined with:

((pray* or god or faith* or religio or spiritual*) in ti, ab) or ((spirituality or religion) in sh)

b. ATLA Religion Database on EBSCO Host (June 2007) was searched using the phrase:

pray* and trial*

c. Web Sites We searched Clinicaltrials.gov on National Institute for Health using the phrase

pray or prayer or god or religion or religious

Searching other resources

We checked all references in the articles selected for further relevant trials.

Searches undertaken for previous versions of this review are included in Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

The methods described below differ from those in earlier versions of this review (Roberts 2000, Roberts 2007). The methods in this 2009 version have been brought up to date and are in keeping with the new format of Cochrane reviews and recent methodological developments. These changes have not materially effected how we have or will manage data, but we have included the 'Methods' section from the previous review for those who are interested (Appendix 2).

Selection of studies

Material downloaded from electronic sources included details of author, institution, or journal of publication. The principal review author (LR) inspected all reports. These were then re‐inspected independently by a second author (IA) in order to ensure reliable selection. We resolved any disagreement by discussion, and where there was still doubt, we obtained the full article for further inspection. When we had obtained the full articles, LR and IA decided whether the studies met the review criteria. If disagreement could not be resolved by discussion, we sought further information and added these trials to the list of those awaiting classification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

Two authors (LR and IA) independently extracted data from included studies. Again, any disagreements were discussed, decisions documented and, if necessary, authors of studies were contacted for clarification. With remaining problems Clive Adams (Co‐ordinating Editor of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group) helped clarify issues and those final decisions were documented.

2. Management

Data were extracted onto standard, simple forms.

3. Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000) and the instrument is either a self‐report or completed by an independent rater or relative (not by the therapist).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again working independently, two authors (LR and IA) assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009). This tool encourages consideration of how the randomisation sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome measurement, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. We would have excluded any studies where sequence generation was at high risk of bias or where allocation was clearly not concealed. If disputes arose as to the correct category for a trial this was resolved through discussion, and guidance from Clive Adams. Where possible, we extracted (and report here) information on the religious beliefs of the authors reporting the included studies because of the possibility that this is related to the risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We adopted p=0.05 as the conventional level of statistical significance but are especially cautious where results were only slightly below this, and we report 95% confidence intervals in preference to p‐values.

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the fixed‐effect risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). For statistically significant results we calculated the number needed to treat/harm statistic (NNT/H), and its 95% CI using Visual Rx (http://www.nntonline.net/) taking account of the event rate in the control group.

2. Continuous data

2.1 Summary statistic

For continuous outcomes we estimated a fixed‐effect weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups. We did not calculate effect size measures.

2.2 Endpoint versus change data

We preferred to use scale endpoint data, which typically cannot have negative values and is easier to interpret from a clinical point of view. Change data are often not ordinal and are problematic to interpret. If endpoint data were unavailable, we used change data.

2.3 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means are reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996)); (c) if a scale starts from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above will be modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐S min), where S is the mean score and S min is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied. When continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. Skewed data from studies of less than 200 participants were entered in additional tables rather than into the data analysis. Skewed data pose less of a problem when looking at means if the sample size is large and these were entered into syntheses.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This increases the risk of type I errors (Bland 1997, Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in an included study, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intraclass correlation coefficients for their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of an included study, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account intraclass correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in schizophrenia, we will only use data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, the additional treatment arms were presented in comparisons. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, these data were not reproduced.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, the findings of a trial must lose credibility (Xia 2007 ‐ direct link). We are forced to make a judgment where this is for the very short‐term trials likely to be included in this review. We decided that if more than 40% of data be unaccounted for at 8 weeks we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses.

2. Binary

If attrition for a binary outcome is between 0 and 40% and outcomes of these people are described, we included these data as reported. Where these data were not clearly described, for the primary outcome we assumed the worst for each person who was lost, and for adverse effects we assumed rates similar to those among patients who did continue to have their data recorded.

3. Continuous

If attrition for a continuous outcome is between 0 and 40% and completer‐only data were reported, we have reproduced these.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies without any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity.

2. Statistical

2.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

2.2 Employing the I‐squared statistic

This provided an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance. I‐squared estimate greater than or equal to 50% was interpreted as evidence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2002).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1995). These are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2009). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were ten or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots were possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

Where possible we employed a fixed‐effect model for analyses. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us, however, random‐effects does put added weight onto the smaller of the studies ‐ those trials that are most vulnerable to bias. For this reason we favour using fixed‐effect models employing random‐effects only when investigating heterogeneity.

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for prayer.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If data are clearly statistically heterogeneous we first checked that data were correctly extracted and entered and that we had made no unit of analysis errors. If the high levels of heterogeneity remained we did not undertake a meta‐analysis at this point for if there is considerable variation in results, and particularly if there is inconsistency in the direction of effect, it may be misleading to quote an average value for the intervention effect. Instead we would have explored possible sources of heterogeneity. We do not pre‐specify any characteristics of studies that may be associated with heterogeneity except those relating to the quality of trial method. If no clear association could be shown by sorting studies by quality of methods a random‐effects meta‐analysis was performed. Should another characteristic of the studies be highlighted by the investigation of heterogeneity, perhaps some clinical heterogeneity not hitherto predicted but plausible causes of heterogeneity, these post‐hoc reasons will be discussed and the data analysed and presented. However, should the heterogeneity be substantially unaffected by use of random‐effects meta‐analysis and no other reasons for the heterogeneity be clear, the results of the individual trials would be presented without a meta‐analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

If necessary, we analysed the impact of including studies with high attrition rates in a sensitivity analysis. We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they are described as 'double‐blind' but only implied randomisation had taken place (but no such trials have been included in the 2009 update). If we found no substantive differences within primary outcome when these high attrition and 'implied randomisation' studies were added to the overall results, we included them in the final analysis. However, if there was a substantive difference, we excluded them and only included clearly randomised trials and those with attrition below 40%.

Results

Description of studies

Please also see 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Results of the search

The original electronic search identified 196 citations and four included studies were identified from these. More recent searches identified six new excluded studies and six new included studies, taking the total number of included studies to ten. Three of the new included studies (Benson 2006, Krucoff 2001 and Walker 1997) were ongoing studies in the original review.

Included studies

The number of included studies now stands at ten with six new studies, Aviles 2001, Benson 2006, Krucoff 2001, Leibovici 2001 and Walker 1997. In all but one of the studies prayer was undertaken after the onset of ill‐health, concurrent with routine treatment, however, in one study, Leibovici 2001, the prayers were ‘retroactive’, that is, they were undertaken after the clinical outcomes were recorded.

1. Duration

Studies ranged from short term with follow‐up for the 'remainder of the admission' (Byrd 1988, Leibovici 2001) to long term with a follow‐up of 15 months (Collipp 1969). Most of the studies, however, were of mid‐term duration. Aviles 2001, Joyce 1964, Krucoff 2001 and Walker 1997 had follow up of six months. Harris 1999 states that participants were the focus of prayer for 28 days but does not comment on the duration of follow‐up. Benson 2006 was also a short trial with prayer for only 14 days, starting the night before coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) and outcomes were measured through the 30 days after surgery.

2. Participants

A total of ten studies which randomised 7646 people are included in this review. Seven of the ten included studies focused on people who were 'acutely ill' with life‐threatening conditions: children with leukaemia (Collipp 1969), those admitted to a coronary care unit (Aviles 2001, Benson 2006, Byrd 1988, Harris 1999 and Krucoff 2001) and people with a blood stream infection (Leibovici 2001). The participants in Joyce 1964 were ill with psychological or rheumatic disease and in Walker 1997 the participants were being treated for alcohol abuse. Collipp 1969 was the only trial not to include adults. The mean age of participants in this trial was around seven years. All other studies randomised people over the age of 18 years.

3. Setting

Participants were mixture of inpatients and outpatients. All received prayer from outside their medical surroundings.

4. Study size

Study size varied from small (Collipp 1969 n=18, Joyce 1964 n=48) to very large (Leibovici 2001 n=3393, Benson 2006 n=1804, Harris 1999 n=1013).

5. Interventions

5.1 Intercessory Prayer

Patients in the intercessory prayer groups received relevant routine care plus daily intercessory prayer. The types of intercessory prayer varied slightly but all prayers were given with the intent that these intercessions would aid recovery of the patient.

5.1.1 Religious background of those interceding

The religious background of the original researchers is likely to have affected their selection of interceders and was mentioned in some studies. Joyce 1964 was undertaken by two researchers, one of whom started with the belief that prayer 'worked' and the other that it did not. The author of Collipp 1969 recruited "...friends of ours in Washington..." to undertake the experimental intervention and concluded the article with the statement "every physician has prescribed this remedy [prayer] and nearly every physician has seen it succeed". Harris 1999 did not comment on the religious feelings of its authors.

All intercessors had religious belief but their background and level of religious activity varied. Byrd 1988 accepted people as intercessors if they were "'born‐again' Christians with an active Christian life as manifested by daily devotional prayer and active Christian fellowship with a local church.” In Collipp 1969 intercessors were "friends of ours in Washington who [...] agreed to organize a prayer group." Joyce 1964 stipulated two required conditions which needed to be fulfilled: (a) a willingness to accept up to six participant names and (b) residence more than 30 miles from the London Hospital. In Harris 1999 intercessors did not have to belong to any particular denomination, but needed to agree with the statements: "I believe in God. I believe that He is personal and is concerned with individual lives. I further believe that He is responsive to prayers for healing made on behalf of the sick". They also all reported at least weekly church attendance and daily prayer habits before the trial. The volunteers in Walker 1997 were initially recruited from the 'Albuquerque Faith Initiative', a community organisation designed to educate religious professionals and laity about substance abuse. They needed to report at least five years experience of intercessory prayer and believe that at least one prayer had been actively answered.

The remaining five studies were unclear about the level of religious activity previously undertaken by its intercessors. Aviles 2001 recruited from local religious groups and community interest meetings but stated the 'beliefs of intercessors was not quantified'. Krucoff 2001 listed several off‐site prayer groups (United School of Christianity, Buddhist, Roman Catholic, Jewish, Fundamentalist Christian, Baptist and Moravian) but gave no other background information. Benson 2006 listed three Christian groups (St Pauls Monastery, Community of Tersian Carmelties and Silent Unity) but no further details. Leibovici 2001 was also unclear about religious background.

5.1.2 Type of prayer given

Apart from Krucoff 2001, prayer was undertaken daily in all studies. Krucoff 2001 had a Jewish prayer which was placed on the Western Wall for the duration of the trial. One trial, Benson 2006, gave a specific phrase ("for a successful surgery with a quick, healthy recovery and no complications") to be added to the daily prayer of the group.

Most trials used intercessors who prayed within the Judeo‐Christian framework although they had a range of backgrounds: Protestant, Roman Catholic and other interdenominational bodies promoting Christian healing (Quakers and the Guild of Health). Intercessors in Krucoff 2001 belonged to seven different nominations, or faiths (as above).

Some participants were prayed for by groups (Benson 2006, Joyce 1964, Collipp 1969, Krucoff 2001), others by individuals (Joyce 1964, Byrd 1988, Harris 1999, Leibovici 2001 and Walker 1997). Efforts were made in some studies to ensure daily prayer was maintained throughout the trial. Byrd 1988 states that prayer was "under the direction of a co‐ordinator", and in Collipp 1969 intercessors received weekly reminders and participated in frequent discussions about their commitment (despite being unaware that they were participating in a study). Intercessors in Harris 1999 were randomly placed in groups of five members, each with a team leader. Prayer, however, was offered individually, not in groups. None of the intercessors in any trial personally knew the participant for whom they were praying.

In Leibovici 2001 prayer was offered after the period of illness and its outcome. Such retrospective prayer is practised by some people.

5.2 Routine care

Those in the control group received the routine care relevant to their setting, including the medication that would normally be given to people suffering from their particular illness. Joyce 1964 provided "standard, uninterrupted medical care" for all the participant groups (rheumatic and psychological conditions) but no further details are available. Collipp 1969 provided drug therapy for all participants (children with leukaemia). Each child received combinations of between two and five drugs (methotrexate, 6‐mercaptopurine, vincristine, prednisone, daunamycin, bis‐chlorethyl‐nitrosourea, cytosinearabioside, tryptophane mustard and fluorinated progesterone). In Byrd 1988, Harris 1999 and Aviles 2001 all participants were treated on the coronary care unit and the control groups received "usual or standard care". It was assumed, but not stated, in a few studies that all participants received standard medical care. Krucoff 2001 defined standard care by 'the absence of any noetic therapy" and Leibovici 2001stated that there was no "sham intervention".

5.3 Awareness of intervention.

Only one study, Benson 2006, specifically informed some participants that they were receiving intercessory prayer from people other than 'friends and family'. This was to determine the effects of awareness of prayer and in accordance with a pre‐specified analysis plan, we separated this data for additional analysis.

6. Outcomes

6.1 Scales used

The criteria for accepting scale data has changed since the original publication of this review. However, no trial in this review presents usable scale data from a valid scale which would be needed to meet this new criteria (see Data extraction and management). After discussion, therefore, we decided to retain the original data and discuss this below.

a. Clinical State Scale and Clinical Attitude Scale Only Joyce 1964 employed these scales. As neither is referenced we assumed they have not been validated. Data from these scales, however, were graded into dichotomous positive or negative outcomes and as un‐validated clinical opinion for these outcomes is acceptable for this review these too have been included. The Clinical State Scale graded changes in the participants' illness by an examination by a physician, from zero (very poor) to four (very good). We considered data from this scale to be similar to data from the Byrd score and therefore presented them as dichotomous data for Clinical state. The Attitude Scale was also used in a similar way and data from this scale are presented as dichotomous data for Behaviour. Data were categorised into 1. positive scores for (a) stoical; (b) positive and cooperative attitude; (zero for 'non‐committal' attitude); and 2. negative scores for (a) apprehensive; and (b) critical and complaining.

b. Byrd Score (Byrd 1988) This was developed by Byrd 1988 to assess clinical state. Clinical outcomes were categorised into 'good', 'intermediate' and 'bad'. It is not clear if those undertaking the categorisation were blind to the data at the time. The scoring system was based on the presence or absence of complications, for example a patient would be categorised 'good clinical state' if they had no or only one relatively unserious complication/s such as mild unstable angina, supraventricular tachyarrhythmia or mild congestive heart failure without pulmonary oedema. A patient would be categorised as 'bad' if they suffered from complications such as extension of initial infarction, cerebrovascular accident or death. A full list of categorisation of complications is given in the paper. Harris 1999 replicated this study and although they developed their own scoring system (MAIHU‐ CCU score, see below) they also used the Byrd score for clinical state to compare data. After discussion, we have accepted this use of the Byrd Score as a form of peer review and used data from the Byrd score.

c. Mid American Heart Institute‐Cardiac Care Unit scoring system: MAHI‐CCU score (Harris 1999) Harris 1999 created their own scoring system to categorise clinical state into good, intermediate or bad. The scoring system is a 'continuous variable that attempts to describe outcomes from excellent to catastrophic'. Points are given if a patient suffers from a complication and the severity of complications are graded, for example, if, after one day a patient developed unstable angina (one point) was treated with antiangian agents (one point) and then suffered a cardiac arrest (five points) their weighted MAHI‐CCU score would be seven. Although the MAHI‐CCU has not been peer reviewed, because this review was originally prepared before the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's change in its guidance on the use of data from scales, we decided to leave the data from the MAHI‐CCU scoring system in this review but are aware it may be prone to bias because it is a scoring system created by the authors of the paper (Marshall 2000)

d. Major Cardiovascular End Points (MACE) (Krucoff 2001) Krucoff 2001 used MACE to assess the clinical state of their participants. Again, complications such as death, myocardial infarction congestive heart failure or bypass surgery were used as markers. We felt these were similar enough to the categories used by the above studies to categorise participants in Krucoff 2001 with MACE as 'intermediate or bad' clinical state. Benson 2006 also used 'major events' (defined by the New York State Cardiac Surgery Reporting System) as an outcome, and again, we felt this data could be used in the same way.

6.2 Choosing 'significant complication'. In Byrd 1988 those complications with statistically significant findings are re‐highlighted in the text of the paper and it is these that are quoted elsewhere (AIDS daily summary). We asked an independent collaborator (Dr Evandro da Silva Freire Coutinho), blind to these data, to choose one 'complication' for presentation in the analysis. He chose 'readmission to Coronary Care Unit (CCU)'. As newly included studies also present data for complications we have kept this outcome as a 'primary significant complication' but also report data for other complications arising after treatment.

Excluded studies

There are now 15 excluded studies in this review. Six trials have been added since the original version of this review (Abbot 2000, Conti 1999, Green 1993, Harrison 1999a, O'Mathuna 1999 and Toth 1999). Three of these (Abbot 2000, O'Mathuna 1999 and Toth 1999) were not trials but reviews. The other three studies were randomised trials not using intercessory prayer as one of the interventions. We excluded Galton 1883, as it was a retrospective study, although cited by Byrd 1988, Collipp 1969 and Joyce 1964. Two studies examined the effect of providing a religious solution to a hypothetical personal problem (Lilliston 1981, Lilliston 1982). A further three trials investigated the effect of specifically "non‐contact therapeutic touch" for dermal healing (Wirth 1994a), the results of non‐traditional prayers on physiological measures (Wirth 1994b), and "distance healing by volunteers trained in LeShan's meditation techniques" (Greyson 1997). As a result of the update of February 2000, Sicher 1998 was excluded as the intervention was 'distance healing'. This technique may have included an element of prayer but did not specifically involve personal, focused, committed and organised intercessory prayer on behalf of another alone. Sicher 1998 is the published result of 'Targ 1993', which, in previous versions of this review, was listed as an 'Ongoing Study'.

We had previously included Cha 2001, but this has been changed to an excluded study in the 2009 update, after we learnt of the controversy surrounding it and the removal of the study from the website of the Journal of Reproductive Medicine.

Awaiting classification

No further publications of Larson 1997 and Choi 1997 have been found despite considerable searching, so we decided to remove these from 'awaiting classification' (previously, ‘awaiting assessment’) and have now excluded them. If further publications come to light we will assess them.

Ongoing studies

In the 2009 update, three studies that were previously in this section (Benson 2006, Krucoff 2001, Walker 1997) have been included. We have not identified any currently ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

All included studies were stated to be randomised. Joyce 1964 stated that allocation was decided by the spin of a coin, Collipp 1969 by randomly selecting names, and Byrd 1988 by a computer generated list. In none of these studies was it stated that those in charge of allocation were blind as to what a 'heads or tails' of the spinning coin meant, to how the computer generated list was to be used or where the next name out of the bag was to go.

Harris 1999 had a rather unexpected method of randomisation. All new admissions to the CCU were identified daily in the chaplain's office, and these new patients were "randomly" assigned to either group by the chaplain's secretary based on the last digit of the medical record number; even numbers assigned to the prayer group, odd to 'usual care'. After some discussion we came to the conclusion that this method of allocation was adequate. Nevertheless, for every outcome that included data from Harris 1999 we undertook an analyses to investigate the sensitivity of the finding to removal of these data. The six studies added to the update were also all stated to be randomised and all described how this was achieved. Aviles 2001, and Walker 1997 used computer programmes. Krucoff 2001and Benson 2006 allocated participants by on‐site envelopes and Leibovici 2001 used a random number generator.

Blinding

Participants in Joyce 1964 were not aware of their participation in a trial and the rater was unaware of the group to which each patient had been allocated. Byrd 1988 obtained written consent from all participants but neither they nor those rating outcomes knew of their group allocation. In Collipp 1969 neither the children with leukaemia nor their parents knew of their inclusion in a trial and, in addition, all physicians were blinded. Even those praying were unaware that they were taking part in a study. Harris 1999 did not obtain written consent, so all participants may have been blind as we have found no report of them having given verbal consent. CCU staff, data collectors and statisticians involved in the studies were also blind to allocation. Five of the six new studies were double blind and described how this was achieved. In each case “double blind” was used to indicate that both the patient and the people responsible for their health care did not know whether the patient was in the prayer or the control group. Of note, Aviles 2001 stated that participants, care‐givers and interviewers were blind to allocation. Finally, Leibovici 2001 did not obtain consent from participants to maintain blindness ‐ the intervention took place after the outcome. The study was double blind; those praying did not know the outcome for any of the patients. One study, Benson 2006, specifically told one group of participants they were receiving intercessory prayer while the other groups were uncertain of their allocation. This was to assess the effects of awareness of intercessory prayer on recovery. All carers and researchers were unaware of each patient's allocation in this trial.

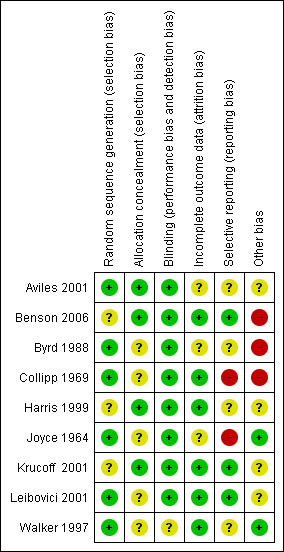

We have not been able to extract data fully for the Risk of Bas table in this update (see Figure 1) because of misplaced papers and the need to reach the deadline for publication. We have not extracted information on incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other potential sources of bias from Collipp 1969, Joyce 1964 or Walker 1997. We will amend this for a forthcoming issue of The Cochrane Library.

1.

Review authors' judgements for each quality item

Incomplete outcome data

Analysis in Joyce 1964 was by sequential, paired analysis and this led to two of the 19 original pairs being eliminated because one of each pair was found not to satisfy the criteria for admission to the study. Also one member of a third pair failed to attend despite repeated requests and data from that pair were lost. Aviles 2001, Benson 2006, Byrd 1988, Harris 1999, Krucoff 2001 and Leibovici 2001 all had a design where loss of data was difficult and full follow‐up was possible.

Selective reporting

The only evidence we found of a failure to report selected results was that Aviles 2001 stated that they were going to report on quality of life and we could not see where they had done this. The opposite ‐ where a few primary outcomes were pre‐stated but many secondary outcomes were then presented ‐ was more prevalent (Benson 2006, Byrd 1988, Harris 1999). Byrd 1988 especially highlighted the statistically significant effects from the secondary outcomes over the equivocal results of the primary outcomes. This caused us some difficulties (please Description of studies).

Other potential sources of bias

The Benson 2006 and Byrd 1988 studies were undertaken by researchers with a prior belief in the positive effects of prayer. The beliefs of the researchers in the other trials are not clear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

As outlined above (Allocation) we did have some concerns as to whether Harris 1999 should be included. We included and excluded Harris 1999 from all outcomes for which that study reported data. In every case it tightened confidence intervals but made no substantive difference in the findings with a few exceptions. When synthesised with other data it tended to be conservative in its findings and make the findings less favourable for the intervention of intercessory prayer. The first exceptions are where all data for a given outcome are from the Harris 1999 study (anaemia/transfusion, atrial fibrillation, cardiopulmonary arrest, catheterization, implanted cardiac defibrillator, interventional coronary procedure, intra‐aortic balloon pumpSwan‐Ganz catheter). The second group of exceptions are where exclusion of Harris 1999 does result in the finding changing from a null finding to one that becomes statistically significant in favour of prayer (congestive heart failure, diuretics, intubation/ventilation, major surgery before discharge, pneumonia).

We had not anticipated a study of prayer in which people prayed for those who had already had an outcome (albeit one unbeknownst to those intervening). In the last update we added this study to the others but, after conversations with the ombusmen of the Cochrane Collaboration and the Editor in Chief, we have moved it to a seperate comparison.

1. INTERCESSORY PRAYER (CONTEMPORANEOUS) versus ROUTINE CARE

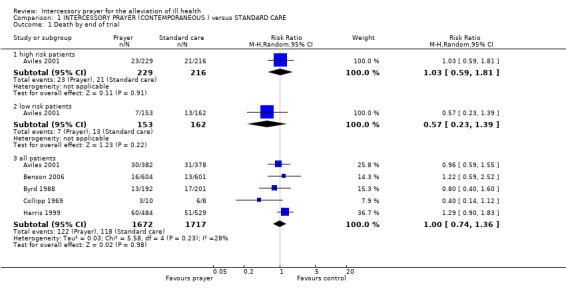

1.1 Death

Five studies present data on death (Aviles 2001, Benson 2006, Collipp 1969, Byrd 1988, Harris 1999). Overall there was no clear effect of intercessory prayer on death (5 RCTs, n=3389, random‐effects RR 1.00 CI 0.74 to 1.36). Aviles 2001 separated data into high‐risk patients and low‐risk patients. This study identified no effect of intercessory prayer on people with low risk of death (1 RCT, n=315, RR 0.57 CI 0.23 to 1.39) or high risk (1 RCT, n=445, RR 1.03 CI 0.59 to 1.81).

1.2 Clinical state

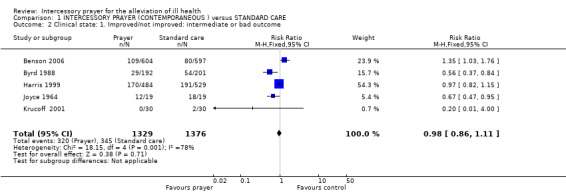

1.2.1 Intermediate or bad outcome

Five studies present data for general clinical state (Joyce 1964, Byrd 1988, Benson 2006, Krucoff 2001, Harris 1999). Overall there was no significant difference in clinical state between intervention groups (5 RCTs, n=2705, RR 0.98 CI 0.86 to 1.11).

1.3 Significant complications

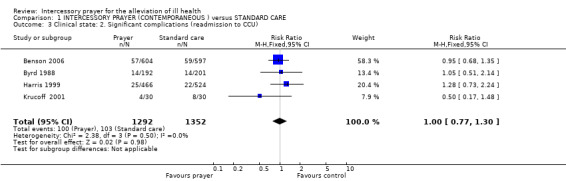

1.3.1 Re‐admission to Coronary Care Unit (CCU)

Four studies found no significant effect for re‐admission to CCU (4 RCTs, n=2644, RR 1.00 CI 0.77 to 1.30).

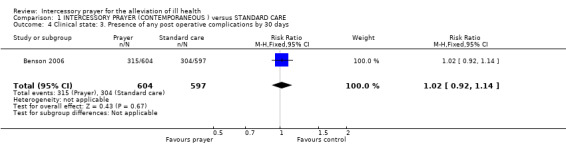

1.3.2 Presence of any post operative complications by 30 days

Only Benson 2006 grouped complications into one outcome of 'any complication'. Compared with routine care, people unaware of receiving intercessory prayer were not shown to be more or less likely to have post operative complications than those not receiving prayer (1 RCT, n=1201, RR 1.02 CI 0.92 to 1.14).

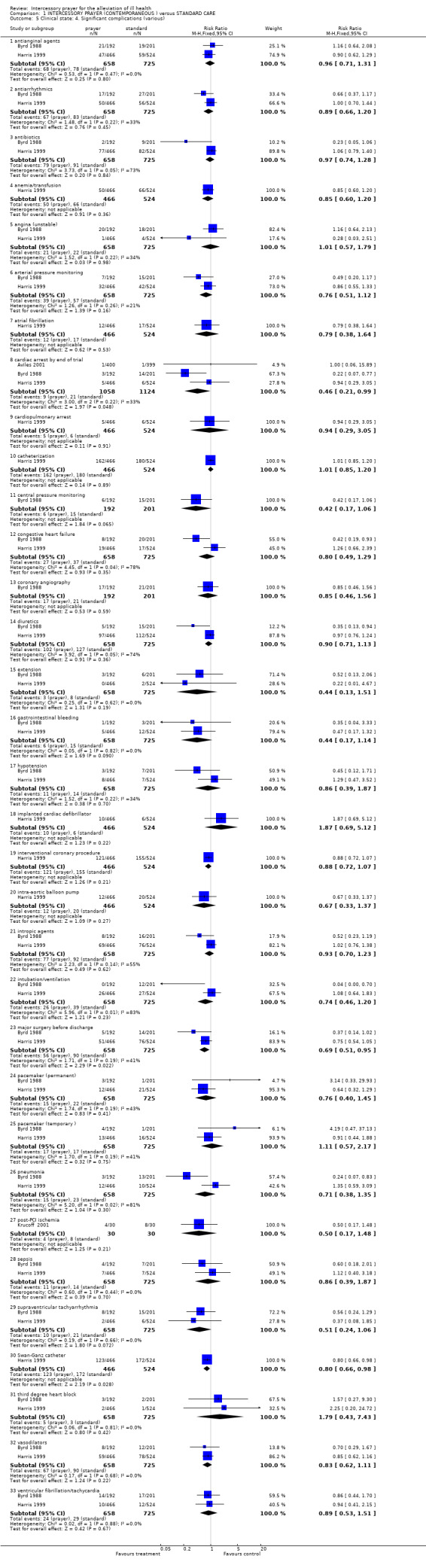

1.3.3 Various complications

Other studies presented data for specific complications. A total of 33 complications were listed as outcomes, of these, only three showed any significant effect. The numbers suffering cardiac arrest before the end of trial, numbers needing major surgery and/or Swan‐Ganz catheter were all significantly lower in the prayer group. Aviles 2001, Byrd 1988 and Harris 1999 report data for cardiac arrest ‐ the result is just statistically significant (3 RCTs, n=2174, RR 0.46 CI 0.21 to 0.99, NNT 100 CI 69 to 5377). The combined analysis of Byrd 1988 and Harris 1999 found significantly more people in standard care underwent major surgery during the trial (2 RCTs, n=1383, RR 0.69 CI 0.51 to 0.95, NNT 27 CI 17 to 162). One study, Harris 1999, found fewer people in the prayer group needed a Swan‐Ganz catheter. This result is also marginally statistically significant (1 RCT, n=990, RR 0.80 CI 0.66 to 0.98, NNT 16 CI 9 to 153).

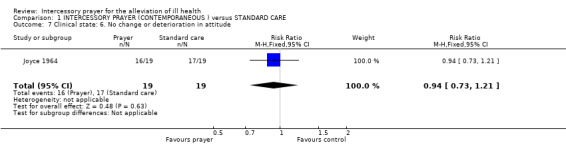

1.4 No change or deterioration in attitude

Joyce 1964 did not detect a significant difference for people receiving intercessory prayer in regard to attitude deterioration or change compared to those receiving routine care for their condition (1 RCT, n=38, RR 0.94 CI 0.73 to 1.21).

1.5 Service use

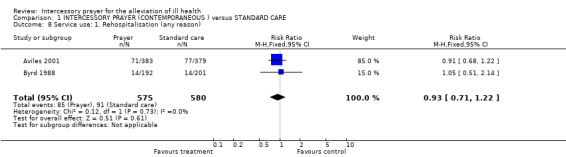

1.5.1 Rehospitalisation, any reason

The combined analysis of Aviles 2001 and Byrd 1988 shows no significant difference on rehospitalisation (2 RCTs, n=1155, RR 0.93 CI 0.71 to 1.22).

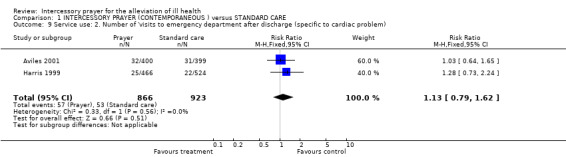

1.5.2 Number of visits to emergency department (specific to cardiac problem)

Harris 1999 found no significant difference between groups in the number of visits to emergency room after discharge (1 RCT, n=1789, RR 1.28 CI 0.73 to 2.24).

1.5.3 Mean number of days in hospital

Two studies presented skewed data for this outcome, results were equivocal (Byrd 1988 and Harris 1999).

1.5.4 Mean number of days in CCU

Skewed data from Byrd 1988 found no significant difference for this outcome.

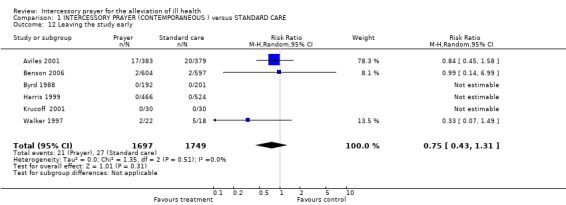

1.6 Leaving the study early

We found no significant difference between groups for numbers of people leaving a study early (6 RCTs, n=3446, RR 0.75 CI 0.43 to 1.31).

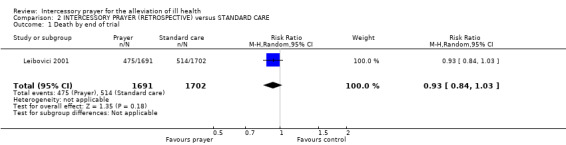

2. INTERCESSORY PRAYER (RETROSPECTIVE) versus ROUTINE CARE

2.1 Death

There is one relevant study (Leibovici 2001). Overall there was no clear effect of 'retroactive' intercessory prayer on death (n=3393, RR 0.93 CI 0.84 to 1.03).

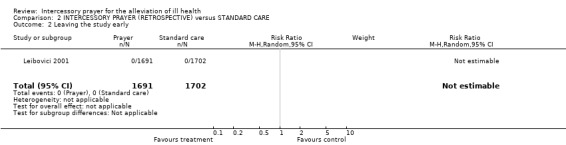

2.2 Leaving the study early

As this study was retroactive and record keeping was, by all accounts complete, no one could leave the study in the conventional sense.

3. AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus ROUTINE CARE

Benson 2006 was the only trial to assess the effect of 'awareness of prayer'.

3.1 Death

No significant difference was found for death (1 RCT, n=1198, RR 0.92 to 1.40)

3.2 Clinical state

3.2.1 Intermediate or bad outcome

Again, there was no significant difference on clinical state between people aware they were being prayed for and people not being prayed for by the end of the trial (1 RCT, n=1198, RR 0.91 CI 0.64 to 1.29).

3.3 Significant complications

3.3.1 Re‐admission to CCU

There was no significant difference between groups for this outcome (1 RCT, n=1198, RR 1.04 CI 1.04 to 1.28).

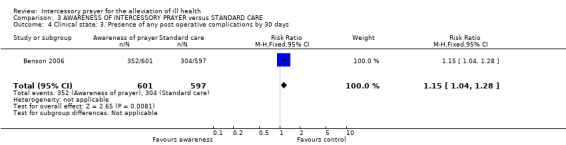

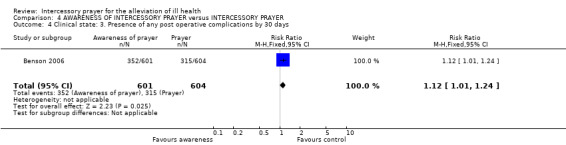

3.3.2 Presence of any post operative complication by 30 days

An effect for this outcome, with those not receiving prayer having fewer post operative complications than those aware they were receiving prayer (1 RCT, n=1198, RR 1.15 CI 1.04 to 1.28, NNT 14 CI 8 to 50).

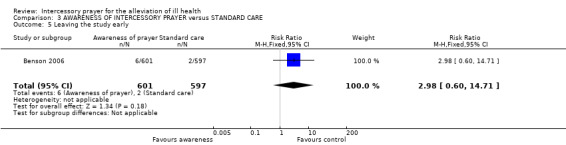

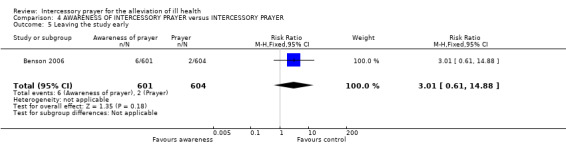

3.4 Leaving the study early

No significant difference between groups was found for leaving the study early (1 RCT, n=1198, RR 2.98 CI 0.60 to 14.71).

4. AWARENESS OF PRAYER versus UNCERTAINTY OF PRAYER

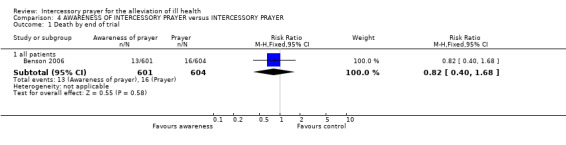

4.1 Death

Benson 2006 found no difference in death between groups (1 RCT, n=1205, RR 0.82 CI 0.40 to 1.68).

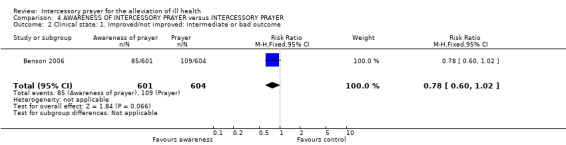

4.2 Clinical state

4.2.1 Intermediate or bad outcome

Although fewer people aware of receiving prayer had a 'bad or intermediate' clinical state by the end of the trial, the result is not statistically significant (1 RCT, n=1205, RR 0.78 CI 0.60 to 1.02).

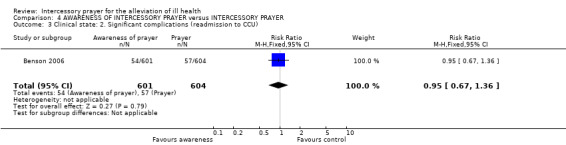

4.3 Significant complications

4.3.1 Re‐admission to CCU

No significant difference between groups was found for re‐admission to CCU (1 RCT, n=1205, RR 0.95 CI 0.67 to 1.36).

4.3.2 Presence of any post operative complication by 30 days

Benson 2006 found a difference between groups, favouring those uncertain of receiving prayer ‐ but it was marginally statistically significant (1 RCT, n=1205, RR 1.12 CI 1.01 to 1.24, NNT 17 CI 9 to 201).

4.4 Leaving the study early

Very few people left the study early and the result is non significant with a wide confidence interval (1 RCT, n=1205, RR 3.01 CI 0.61 to 14.88).

Discussion

Summary of main results

1. INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus ROUTINE CARE

1.1 Death

Overall, the trial data show no more or no fewer deaths in the intercessory prayer group. There is no clear effect of this type of prayer, within these very unusual randomised trials. People of faith may speculate as to why this is so. There could be many plausible reasons when considered from this perspective. Those of no theological belief will also be able to use these data to support their hypotheses.

1.2 Clinical state

1.2.1 Intermediate/poor outcome

Five studies (n=2705) presented data relating to intermediate or poor outcome (Benson 2006, Byrd 1988, Harris 1999, Joyce 1964, Krucoff 2001). Results were equivocal and heterogeneous (I2 =78%). Harris 1999 carried most weight in this meta‐analysis, and although this was a trial replicating Byrd 1988, it found prayer to be less effective. Harris 1999 suggests this could be due to "important differences between the two study designs" (more stringent blinding, lack of informed consent possibly changing participant group, amount of participant information given to intercessors). It is also important to note that in Byrd 1988 the point at which decisions were made relating to the definitions of 'good', 'intermediate' and 'poor' was not stipulated. It is not clear whether these important decisions were made before or after seeing the data and whether those doing the analysis were blind to group allocation. Therefore, bias may have influenced the result of the rather positive Byrd 1988. It is also interesting that Benson 2006, another large trial, also found less favourable results for prayer than the smaller trials. The outcomes of these two larger trials were different to the results of other prayer trials. Participants in Benson 2006 received prayer for only 14 days and as the original authors noted, this may not be enough time for prayer to be effective. It may also be that the study measured an outcome which is not effected by prayer or that prayer has no effect at all.

Other problems with interpreting clinical state results are the use of non‐published scales. In the protocol for this review we stated that only published scales would be reported in an attempt to avoid the presentation of invalid data. However, we were limited in that all data for this outcome came from scales for which the validation status is not clear. The Byrd score used by Byrd 1988 and Harris 1999 was created by Byrd 1988 and replicated by Harris 1999. We felt this was a form of 'peer review' and included these data but realise it could be prone to bias and more valid scale data are needed to confirm this result. The Clinical State Scale, as used in Joyce 1964, is also not referenced and it is unclear if it is a valid measure of health or can be used with any degree of reliability. Data on this outcome are so positive that it may be widely quoted. Even if this scale is indeed a valid measure of health, such a result from a small trial (n=38) must be viewed with caution.

1.3 Significant complications

The presence of post operative complications was a main outcome in several trials. Byrd 1988 and Harris 1999 both presented long lists of possible complications. As noted above, we asked a colleague to choose a generic 'significant' complication blind to the data. He chose 'Readmission to Coronary Care Unit' and results from four studies (n=2644) found no overall difference in these readmissions.

Analysis of data from the list of specific complications found three out of 33 outcomes were statistically significant, all favouring prayer. However, the two studies presenting these data (Byrd 1988, Harris 1999) presented results for such a long list of complications that statistical analysis was likely to highlight some as 'statistically significantly' improved by the use of prayer by chance alone (Bender 2008). The authors of Byrd 1988 do state how multiple analysis of variables can lead to spurious 'significant' results but go on to re‐report these in the text of the paper. It is these results that are then selectively quoted in other papers, leading to reporting bias (Anonymous 1995). Benson 2006 did not present results for individual specific complications but summated data into 'presence of any complication' and found no effect.

1.4 No change or deterioration in attitude

Joyce 1964 presented data from an unknown 'Attitude Scale' and the same arguments apply to this as to the Clinical State Scale (see above). Results are equivocal. Even if the Attitude Scale is a valid measure of attitude, the trial was too small to detect a difference unless it was very large.

1.5 Service use

No effect was found for any service use outcomes. There were no significant differences between groups for rehospitalisation (n=1155) or visits to emergency departments (n=1789).

1.6 Leaving the study early

Six studies (n=3446) found no overall difference in the numbers leaving studies early. However, it might be better to regard this outcome as “loss to follow up” rather than leaving the study early because, in most trials, the patients were not aware that they were being studied.

2. INTERCESSORY PRAYER (RETROSPECTIVE) versus ROUTINE CARE

2.1 Death

The purpose of this review is not to consider the putative means by which prayer may or may not be effective, but only to consider the results of well‐constructed trials. Leibovici 2001 attempted to test the effects of such prayer and did not find any clear effect (n=3393, RR 0.93 CI 0.84 to 1.03). Retrospective prayer may be considered theologically controversial, but we are not concerned with theology. Our aim is to review the empirical evidence for the efficacy of prayer as a treatment for ill‐health rather than to consider questions of metaphysics. We judge ourselves bound to analyse the results of any trial that fits our original criteria (including our initial definition of prayer) and which is methodologically well constructed. Having set our protocol we are convinced that it would be unscientific to modify it to exclude a study that fits our criteria for inclusion, for all it approaches this from an unusual angle.

2.2 Leaving the study early

We understand that record keeping was complete so no one could leave the study in the conventional sense.

3. AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus ROUTINE CARE

Benson 2006 found no significant effect for 'awareness of prayer' (where the participants were told and gave consent for intercessory prayer on their behalf, for their recovery from illness) for death, clinical state or leaving the study early. There was however, a significant effect favouring standard care for 'presence of post operative complications' (1 RCT, n=1198, RR 1.15 CI 1.04 to 1.28, NNH 14 CI 8 to 50). This result is from a single trial and needs replication if it is to be accepted. One suggestion, made by the original authors, as to why people not receiving prayer should have fewer postoperative complications than those who knew they were being prayed for is the limited time prayer was offered to those in the prayer group. This result, which is just statistically significant could also be due the play of chance when there is truly no difference between the groups or be a real, toxic effect of the knowledge that one is being prayed for.

4. AWARENESS OF INTERCESSORY PRAYER versus UNCERTAINTY OF PRAYER

Here the intervention 'awareness of prayer' is as above and those in the 'uncertainty of prayer' group were told they may or may not be the focus of intercessory prayer, by either an individual or group praying for their recovery from illness.

The single trial that investigated this, Benson 2006, found no significant differences between groups for any outcomes, except for presence of post operative complications (1 RCT, n=1205, RR 1.12 CI 1.01 to 1.24, NNH 17 CI 9 to 201). As above, this suggests that awareness of a person or group praying for you may have moderate untoward effects, but this finding needs replication if it is to be accepted.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There is considerable interest relating to this widely used health care intervention and studies relevant to prayer and distance healing continue to be carried out, although we know of no ongoing studies directly relevant to this review. There are, however, a number of studies, at least as extensive in number as those included in this review, which deal with interventions of a spiritual nature not focused specifically on the supplication of God or a god. These include such practices as ‘distance healing’. We restricted our review to ‘intercessory prayer’, as widely understood and were limited by a lack of usable data within the included trials.

A further issue is that the healthcare conditions of the trial participants were diverse, although the majority did suffer from coronary disease (Aviles 2001, Benson 2006, Byrd 1988, Harris 1999, Krucoff 2001). This could be a limitation or a strength, but all of the conditions were serious and life‐threatening and we expect that the beneficial, harmful or non‐existent effects of prayer should be similar across different health problems.

Quality of the evidence

We have not yet fully investigated the quality of the evidence arising from the trials in this review but we do not consider it to be radically different from what is common for randomised trials of, for example, drug interventions or psychological therapies. In some ways, the original researchers for these prayer trials have been more clear about their potential for bias and their prior beliefs than would be expected in a trial of a drug run by the pharmaceutical industry or of a psychological therapy run by a psychotherapist. Overall, the reporting of the included studies could have been improved and it is likely that all studies fall into a category of having at least a moderate risk of bias. For example, sequence generation, concealment, blinding were not well described in any of the studies and this poor description of these methodological parameters has been shown to be associated with an over estimate of effect (Jüni 2001). Having said that, the overall estimates were non‐significant so it is not clear how increasing the methodological quality of the evidence would have changed the result.

Potential biases in the review process

Searching for these unusual studies is not easy. There is no clear place where they would be published or indexed. Several databases have been used but it is likely that we have missed some eligible trials. These are likely to be those studies that are smaller and more difficult to publish ‐ and, perhaps less positive for prayer (Egger 1995).

We have excluded Cha 2001 from this version of the review because of the comments received feedback and knowledge gained by our own investigations. We may have been incorrect in doing this and still do not have proof that the study was bogus but the behaviour of the principal investigator raises concerns about its legitimacy which makes it safer to exclude it at this time.

We have also received comments suggesting that publication in the 2001 Christmas issue of the BMJ should preclude a study from inclusion because its methods or findings would be "jest" (Feedback). We found no evidence that this was true. Leibovici 2001 is an unusual and original design ‐ but it appears to have used a rigorous design, and, although a challenging study, it was conducted carefully and is presented respectfully. We do not agree that it should be regarded as a "jest" and excluded on those grounds but, as with all Cochrane reviews, we present its results explicitly and others may wish to remove it before conducting their own meta‐analysis using the RevMan 5 data file which is available alongside this review. We do acknowledge that this study will pose philosophical problems for some readers. We aim not to involve ourselves in such philosophical discussions but to include all studies that tested empirical claims in a rigorous, empirical way.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This version of the review broadly concurs with findings from those that preceded it (Roberts 2000, Roberts 2007).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For people receiving health care