Abstract

Background

This retrospective study aimed to evaluate the prognostic roles of distant metastatic patterns in de novo metastatic triple-negative breast cancer to explore the roles of surgery on the primary tumor and to characterize the prognostic factors of organ-specific metastasis.

Material/Methods

Data were obtained from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. Kaplan-Meier analyses and log-rank tests were employed to compare survival outcomes among variables. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess risk factors for survival. The key endpoints were overall survival and breast cancer-specific survival.

Results

A total of 1888 patients were eligible. Distant metastatic site displayed a significant prognostic impact on survival. Using liver metastasis as the reference, overall survival was higher for bone (hazard ratio [HR] 0.770, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.634–0.935, P=0.008) and lung (HR 0.747, 95% CI 0.612–0.911, P=0.004) metastases. Using patients with brain metastasis as the reference, patients with bone (HR 0.516, 95% CI 0.392–0.680, P<0.001), lung (HR 0.500, 95% CI 0.379–0.661, P<0.001) or liver (HR 0.670, 95% CI 0.496–0.905, P=0.009) metastases exhibited better overall survival. Single-site metastatic patients who received surgery for the primary tumor had more favorable overall survival (P<0.001) and breast cancer-specific survival (P<0.001) than those who did not. Additionally, age, insurance status, chemotherapy, and surgery affected overall survival for patients with isolated bone metastasis; chemotherapy, and surgery affected overall survival for patients with isolated lung metastasis; and insurance status, chemotherapy, and surgery affected overall survival for patients with isolated liver metastasis.

Conclusions

Our study verified the specific prognostic significance of distant metastatic site for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer at diagnosis. Surgery on the primary tumor significantly improved survival for patients with single distant metastasis. The identified prognostic factors contributed to evaluating the prognoses for distant metastatic triple-negative breast cancer patients.

MeSH Keywords: Neoplasm Metastasis, Prognosis, SEER Program, Survival Analysis, Triple Negative Breast Neoplasms

Background

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in women following lung cancer. In the United States, 266 120 new diagnoses and 40 920 deaths due to breast cancer are predicted for 2018 [1]. Breast cancer prognoses vary greatly among molecular subtypes [2]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is characterized as a more aggressive subtype that lacks the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, and this subtype comprises approximately 15% of breast cancer cases diagnosed annually worldwide [3,4]. Because of the higher risk of distant metastases, recurrence and mortality, TNBC prognoses are dismal compared with those of other subtypes [5–7]. Furthermore, without available targets, chemotherapy remains the main treatment for TNBC. Thus, understanding the factors inducing aggressiveness and poor outcomes is necessary to further clarify potential treatment strategies and therapeutic goals for TNBC.

Characteristics that affect TNBC prognosis are multifactorial and include age, histological type, pathological grade, and clinical stage. Kassam et al. observed that patients >50 years of age with de novo advanced TNBC had longer overall survivals (OS) than did those <50 years old at first diagnosis (hazard ratio [HR] 0.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.27–0.76, P=0.003) [8]. Zhao et al. found that compared with invasive cancer of no special type, mixed nonspecific and lobular carcinomas had worse OS (P=0.005) and breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) (P<0.001) [9]. However, patients with metastatic TNBC generally had poor prognoses, with a median survival of approximately 12 months [6,8,10].

The most common metastatic site for advanced TNBC at presentation is bone, followed by the lung, liver, and brain [11]. Several studies have shown that TNBC patients often present with brain and lung metastases rather than bone or liver metastases [12,13]. Currently, TNBC patients harboring different metastatic sites are considered to have similarly poor outcomes. Despite an unsatisfactory outcome overall, TNBC remains quite heterogeneous relative to individual prognoses. These heterogeneities may be caused by small sample sizes, such as in the studies of Kassam et al. (111 patients) and Tischkowitz et al. (456 patients) [8,14]. The distant metastatic TNBC sites may have prognostic impacts on survival. Knowledge of the metastatic patterns of TNBC is essential to treat and manage patients. Jin et al. assessed the incidence rate and prognosis of brain metastasis for advanced TNBC [15]. Kassam et al. reported that patients with visceral metastasis as the first distant metastatic site had worse survival rates than patients with non-visceral metastases (P=0.021) [8]. However, these studies with small sample sizes focused on only 1 or 2 distant metastatic sites, and the prognostic impacts of site-specific metastasis were unexplored. Because data on organ-specific metastases are seldom documented in population-based studies, the prognostic roles of different metastatic sites remain unclear in de novo metastatic TNBC. Moreover, because treatment options are limited, it is unclear whether surgery on the primary lesion at diagnosis would provide an additional survival benefit for site-specific metastasis patients; thus, further investigation is warranted.

Therefore, this study evaluated the prognostic roles of site-specific metastasis in de novo metastatic TNBC patients using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. The therapeutic roles of surgery on the primary site and the prognostic factors of site-specific metastasis were also investigated.

Material and Methods

Database and patient selection

Data were obtained from the publicly available SEER-18 database of the United States National Cancer Institute, which covers approximately 28% of the United States population. The SEER database from 2010 included the variables “Mets at Dx-Bone”, “Mets at Dx-Lung”, “Mets at Dx-Brain”, and “Mets at Dx-Liver”, which confirmed the bone, lung, brain, and liver metastases at initial diagnoses, respectively. SEER*Stat version 8.3.5 was applied to retrieve the data [16]. All data from the SEER program were exempt from review by the institutional medical ethics committee, and no informed consent was required.

The inclusion criteria defined for eligible patients were as follows: 1) data were from de novo stage IV breast cancer between 2010 and 2015 (details regarding site-specific metastases were unavailable before 2010); 2) the molecular subtype of the patient’s tumor was TNBC; 3) female patients were >18 years old; 4) primary breast cancer diagnosis was labeled as “ICD-O-3 C50.0-C50.9” [17]; and 5) patients had confirmed distant metastatic sites, including lung, liver, bone, or brain. Patients with unknown follow-up information, surgery or survival data and those without complete metastatic information for these 4 sites were excluded from further analysis.

The following potential demographics and clinicopathological variables were evaluated: age, race, grade, tumor size, node stage, chemotherapy, surgery on the primary tumor, insurance, marital status, and metastatic site. In the current dataset, chemotherapy was defined as “yes” or “no/unknown”. Surgery of the primary tumor was classified as either “surgery” or “no surgery”. Survival in months, cause-specific death classification, and vital status were also retrieved from the SEER database. Metastatic TNBC patients were classified based on the sites and number of metastases. The primary endpoints were OS and BCSS.

Statistical analyses

Pearson’s chi-square test was conducted to compare demographic and clinicopathological characteristics across different metastatic sites and numbers. OS was calculated as the time from initial diagnosis to death from any cause. BCSS was calculated as from the time from initial diagnosis to death attributed to breast cancer. Survival statistics were generated using Kaplan-Meier analyses. Log-rank testing was conducted to estimate survival differences among groups. Cox proportional hazard models were employed to analyze independent predictors of survival, which were reported as HRs with homologous 95% CIs. Statistically significant variables in the univariate Cox models were matched using multivariate Cox models. A 2-tailed P-value <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical tests were conducted using SPSS software version 23.0 (IBM, NY, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 1888 de novo metastatic TNBC patients between 2010 and 2015 were identified in the analyses. The included patients’ baseline features are presented in Table 1: 1150 patients (60.91%) were less than 65 years old, 1285 patients (68.06%) were white, 804 patients (42.58%) had been married, and 1783 patients (94.44%) were insured. Overall, 681 patients (36.07%) underwent surgery for primary tumors, in which radical mastectomy (n=302, 44.35%) was the main surgery type, followed by partial mastectomy (n=185, 27.17%), and total mastectomy without nodal dissection (n=170, 24.96%). Most patients (n=1357, 71.88%) received chemotherapy. Among the patients who underwent surgery, most (n=542, 79.59%) also received chemotherapy, while 392 patients (20.76%) received no chemotherapy or surgery. Detailed demographics and the number and baseline characteristics of the distant metastatic sites are presented in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 1888 patients with de novo stage IV triple-negative breast cancer.

| Features | Level | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <65 | 1150 (60.91) |

| ≥65 | 738 (39.09) | |

| Race | White | 1285 (68.06) |

| Black | 481 (25.48) | |

| Others | 122 (6.46) | |

| Grade | G1/G2 | 287 (15.20) |

| G3/G4 | 1305 (69.12) | |

| Unknown | 296 (15.68) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | 267 (14.14) |

| 2–5 | 625 (33.10) | |

| >5 | 683 (36.17) | |

| Unknown | 313 (16.59) | |

| Node stage | Node negative | 442 (23.41) |

| Node positive | 1311 (69.44) | |

| Unknown | 135 (7.15) | |

| Surgery of the primary tumor | Yes | 681 (36.07) |

| No | 1207 (63.93) | |

| Chemotherapy | Yes | 1357 (71.88) |

| No/unknown | 531 (28.12) | |

| Insurance | Yes | 1783 (94.44) |

| No | 86 (4.56) | |

| Unknown | 19 (1.00) | |

| Marital status | Married | 804 (42.59) |

| Unmarried | 995 (52.70) | |

| Unknown | 89 (4.71) |

Metastatic site distribution

The metastatic site distribution is shown in Table 2. A total of 2833 metastatic sites were covered in the 1888 metastatic TNBC patients. The most common metastatic site was bone (n=997, 35.19%), followed by lung (n=932, 32.90%), liver (n=636, 22.45%) and brain (n=268, 9.46%). Overall, the numbers of patients with 1, 2, 3, and 4 distant metastatic sites were 1177 patients (62.34%), 519 patients (27.49%), 150 patients (7.94%), and 42 patients (2.22%), respectively. Fifteen distant metastatic patterns were found among these 4 metastatic sites, 4 of which were single-site metastasis (n=1177, 62.34%), and 11 of which were multisite metastases (n=711, 37.66%). Patients with isolated bone metastases accounted for 25.16% (475 out of 1888 patients) of all included patients. The proportion of patients with isolated brain metastases was 3.92% (74 out of 1888 patients), accounting for the fewest single-site metastatic patients. For patients with 2 distant metastatic sites, the largest proportion (156 out of 1888 patients; 8.26%) had combined bone and liver metastases. Only 6 patients had combined brain and liver metastases. Compared with single-site metastasis, a 7.36% increased mortality risk was found in patients with 2 metastatic sites. The death risk in patients with 3 metastatic sites was 9.09% higher than that in patients with 2 metastatic sites, while patients with 4 metastatic sites had a 4.19% higher risk of mortality than those with 3 metastatic sites.

Table 2.

Patterns of distant metastases for the 1888 patients with de novo stage IV triple-negative breast cancer.

| Sites of distant metastases | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| One site of distant metastasis | 1177 (62.34) |

| Bone | 475 (25.16) |

| Lung | 434 (22.98) |

| Liver | 194 (10.28) |

| Brain | 74 (3.92) |

| Two sites of distant metastasis | 519 (27.49) |

| Bone & lung | 154 (8.16) |

| Bone & liver | 156 (8.26) |

| Bone & brain | 32 (1.70) |

| Lung & liver | 114 (6.04) |

| Lung & brain | 57 (3.02) |

| Liver & brain | 6 (0.32) |

| Three sites of distant metastases | 150 (7.94) |

| Bone & lung & liver | 93 (4.93) |

| Bone & lung & brain | 26 (1.38) |

| Bone & liver & brain | 19 (1.00) |

| Lung & liver & brain | 12 (0.63) |

| Four sites of distant metastases | 42 (2.22) |

| Bone & lung & liver & brain | 42 (2.22) |

Impacts of site-specific metastases on survival

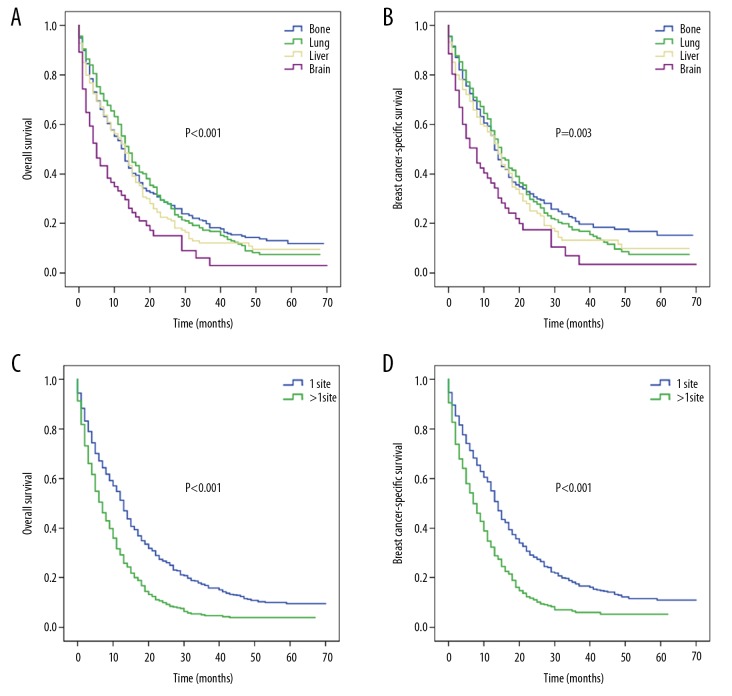

For patients with isolated metastasis, the median OS rates of bone, lung, liver, and brain metastasis were 13, 14, 13, and 5 months, respectively (P<0.001; Figure 1A), with corresponding median BCSS values of 13, 15, 14, and 8 months (P=0.003; Figure 1B). The median OS was 13 months for single-site metastasis and 7 months for multisite metastases (P<0.001; Figure 1C), while the corresponding median BCSS values were 14 and 7 months (P<0.001; Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with single-site metastasis and for entire cohorts: (A) overall survival and (B) breast cancer-specific survival for patients with single-site metastasis stratified by sites of distant metastases; (C) overall survival and (D) breast cancer-specific survival for entire cohorts stratified by the number of metastatic sites.

In patients with isolated metastases, age, marital status, insurance, surgery chemotherapy, surgery, and metastatic site were examined using univariate Cox analyses and were found to be related to OS and BCSS (Table 3, Supplementary Table 3). For the entire cohort, the univariate Cox models indicated that age, surgery, chemotherapy, marital status, ethnicity, insurance, and site number were associated with survival (Table 3, Supplementary Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for overall survival of patients with de novo stage IV triple-negative breast cancer.

| Features | Level | One site of distant metastases | Entire cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | <65 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| ≥65 | 1.385 (1.209–1.588) | <0.001 | 1.098 (0.950–1.270) | 0.206 | 1.332 (1.198–1.480) | <0.001 | 1.148 (1.028–1.282) | 0.015 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Race | White | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| Black | 1.053 (0.903–1.227) | 0.509 | – | – | 1.074 (0.954–1.209) | 0.236 | – | – | |

| Others | 0.992 (0.748–1.315) | 0.956 | – | – | 0.956 (0.764–1.196) | 0.693 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| G3/G4 | 0.974 (0.804–1.181) | 0.790 | – | – | 0.956 (0.825–1.108) | 0.553 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| 2–5 | 1.037 (0.836–1.285) | 0.743 | – | – | 0.940 (0.797–1.109) | 0.462 | – | – | |

| >5 | 1.044 (0.844–1.292) | 0.690 | – | – | 0.966 (0.821–1.136) | 0.674 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Node stage | Node negative | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| Node positive | 1.062 (0.903–1.248) | 0.468 | – | – | 1.002 (0.883–1.137) | 0.977 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Surgery of the primary | No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.476 (0.414–0.547) | <0.001 | 0.505 (0.439–0.582) | <0.001 | 0.492 (0.440–0.550) | <0.001 | 0.571 (0.509–0.641) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Chemotherapy | No/unknown | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.406 (0.352–0.470) | <0.001 | 0.455 (0.389–0.531) | <0.001 | 0.406 (0.363–0.454) | <0.001 | 0.437 (0.388–0.491) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Insurance | Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| No | 1.823 (1.331–2.497) | <0.001 | 1.749 (1.266–2.416) | 0.001 | 1.591 (1.259–2.011) | <0.001 | 1.540 (1.212–1.957) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Marital status | Married | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Unmarried | 1.273 (1.107–1.463) | 0.001 | 1.180 (1.024–1.359) | 0.022 | 1.302 (1.169–1.450) | <0.001 | 1.201 (1.078–1.339) | 0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Metastatic sites | Brian | Ref | Ref | – | – | ||||

| Bone | 0.565 (0.430–0.743) | <0.001 | 0.516 (0.392–0.680) | <0.001 | – | – | – | – | |

| Lung | 0.546 (0.414–0.720) | <.0001 | 0.500 (0.379–0.661) | <0.001 | – | – | – | – | |

| Liver | 0.631 (0.469–0.851) | 0.003 | 0.670 (0.496–0.905) | 0.009 | – | – | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | 1 | – | – | Ref | Ref | ||||

| >1 | – | – | – | – | 1.682 (1.512–1.872) | <0.001 | 1.566 (1.403–1.748) | <0.001 | |

Multivariate Cox analyses revealed that distant metastatic site had a significant prognostic role for OS and BCSS in patients with single-site metastasis (Table 3, Supplementary Table 3). Using brain metastases as the reference, bone (HR 0.516, 95% CI 0.392–0.680, P<0.001), lung (HR 0.500, 95% CI 0.379–0.661, P<0.001) and liver (HR 0.670, 95% CI 0.496–0.905, P=0.009) metastases were related to better OS. Using liver metastasis as a reference, distant metastases to bone (HR 0.770, 95% CI 0.634–0.935, P=0.008) and lung (HR 0.747, 95% CI 0.612–0.911, P=0.004) were related to higher OS (Supplementary Table 4). Similarly, using liver metastasis as the reference, bone (HR 0.763, 95% CI 0.610–0.955, P=0.018) and lung (HR 0.780, 95% CI 0.621–0.979, P=0.032) metastases were related to longer BCSS (Supplementary Table 5).

The multivariate Cox model indicated that the number of metastatic sites was a significant prognostic factor of OS and BCSS for the entire cohort (Table 3, Supplementary Table 3). Compared with single-site metastasis, multisite distant metastases were associated with poorer OS (HR 1.566, 95% CI 1.403–1.748, P<0.001) and BCSS (HR 1.584, 95% CI 1.397–1.797, P<0.001). Moreover, multivariate Cox analyses suggested that insurance, surgery, chemotherapy, and being married were associated with preferable OS and BCSS in both the entire cohort data and in the single metastatic site data (Table 3, Supplementary Table 3).

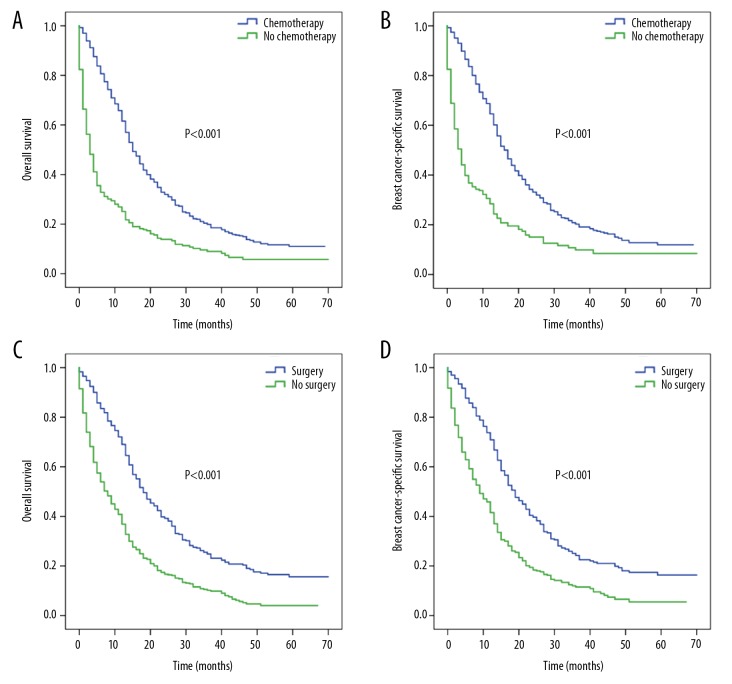

Effects of chemotherapy and surgery on the survival of patients with single-site metastases

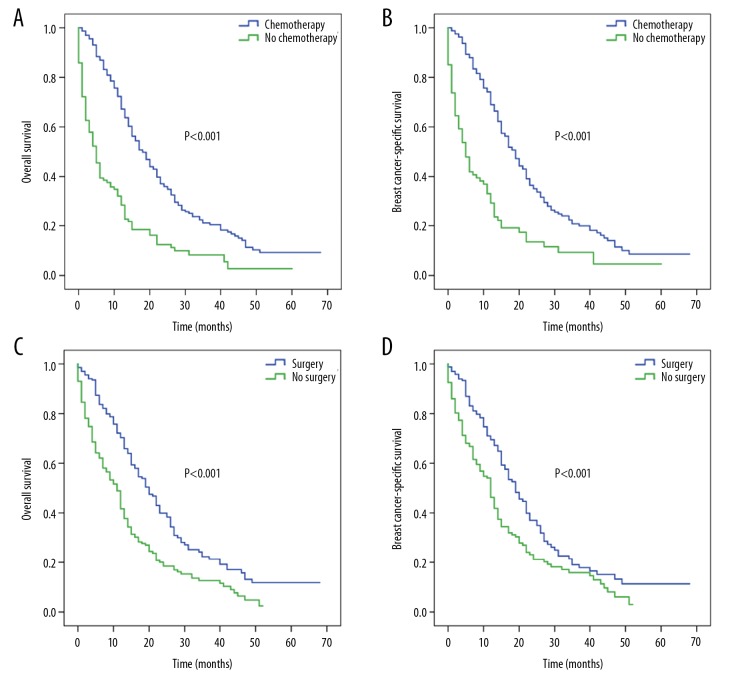

The roles of chemotherapy and surgery were further analyzed in single-site metastatic patients. Patients who had chemotherapy had a better OS (median: 15 versus 3 months) and BCSS (median: 17 versus 4 months) (all, P<0.001) than those who received no chemotherapy (Figure 2A, 2B). Surgery-treated patients had a higher median OS (18 months versus 8 months) and BCSS (19 months versus 9 months) (all, P<0.001) than those who did not undergo surgery (Figure 2C, 2D).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with single-site metastasis based on chemotherapy and surgery: (A) overall survival and (B) breast cancer-specific survival based on chemotherapy; (C) overall survival and (D) breast cancer-specific survival based on surgery.

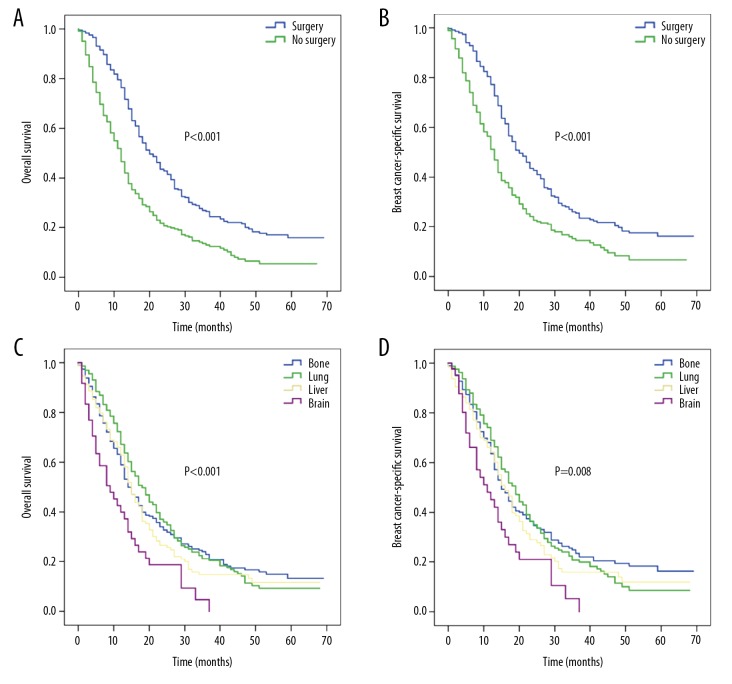

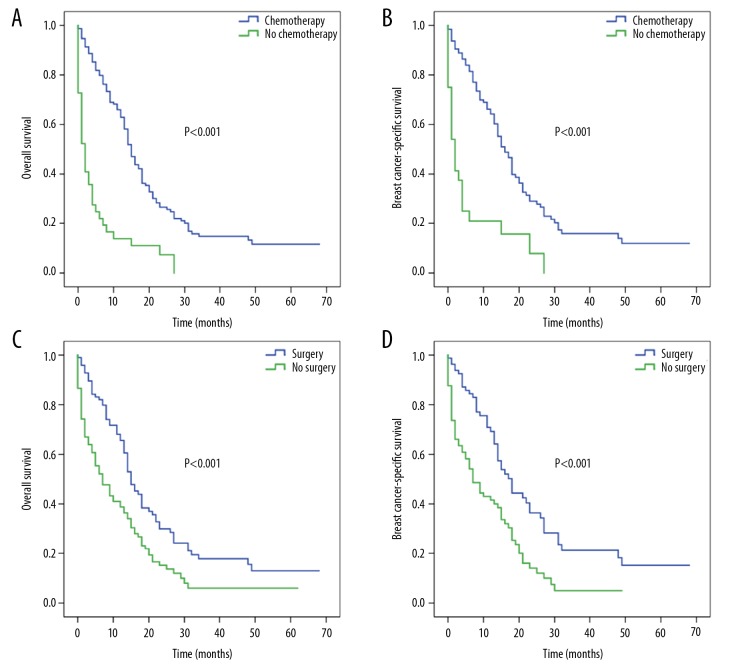

When single-site metastatic patients received chemotherapy, patients who underwent surgery had better median OS (20 versus 12 months) and BCSS (20 versus 13 months) (all, P<0.001) than those who did not undergo surgery (Figure 3A, 3B). For chemotherapy-treated patients, the median OS rates for bone, lung, liver, and brain metastases were 14, 18, 15, and 9 months, respectively (P<0.001; Figure 3C), while the corresponding median BCSS rates were 15, 19, 16 and 11 months (P=0.008; Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with single-site metastasis who received chemotherapy according to surgery and specific metastatic site: (A) overall survival and (B) breast cancer-specific survival based on surgery; (C) overall survival and (D) breast cancer-specific survival based on specific metastatic site.

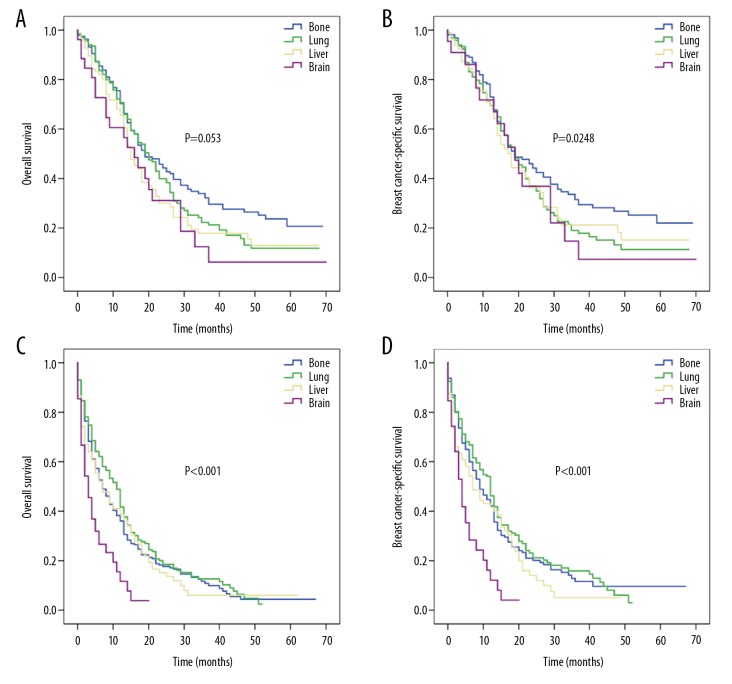

For surgically-treated patients, the corresponding median OS rates for bone, lung, liver, and brain metastases were 19, 20, 15, and 16 months, respectively (P=0.053; Figure 4A) and for BCSS rates were 19, 19, 18, and 19 months, respectively (P=0.248; Figure 4B). For patients who received no surgical treatment, the corresponding median OS rates were 7, 11, 7, and 3 months (P<0.001; Figure 4C) and median BCSS rates were 9, 12, 7, and 4 months (P<0.001; Figure 4D) for bone, lung, liver, and brain metastases, respectively.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with single-site metastasis based on surgery: (A) overall survival and (B) breast cancer-specific survival for patients with surgery according to specific metastatic site; (C) overall survival and (D) breast cancer-specific survival for patients without surgery according to specific metastatic site.

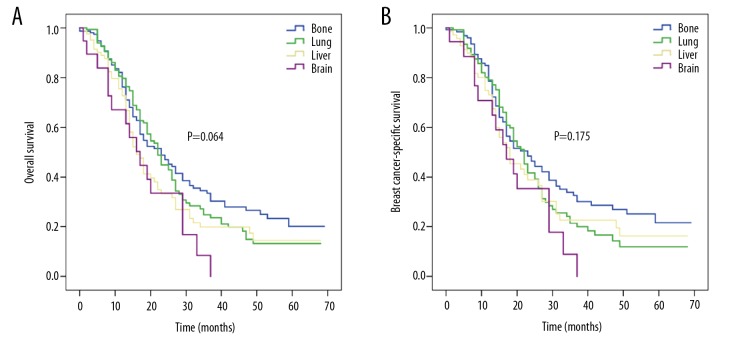

For patients who received both chemotherapy and surgery, the median OS rates for bone, lung, brain, and liver metastases were 23, 22, 17, and 16 months, respectively (P=0.064; Figure 5A), while the corresponding median BCSS rates were 23, 22, 18, and 17 months (P=0.175; Figure 5B), respectively.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of (A) overall survival and (B) breast cancer-specific survival for patients with single-site metastasis who received both chemotherapy and surgery according to specific metastatic site.

Prognostic factors for organ-specific metastasis

For patients with isolated bone metastasis, age, insurance, marital status, chemotherapy, and surgery were related to OS in a univariate Cox model (Supplementary Table 6). Subsequently, multivariate Cox analyses including these variables indicated that age, insurance, chemotherapy, and surgery affected OS. Patients aged ≥65 years had a higher risk of mortality (HR 1.356, 95% CI 1.083–1.696, P=0.008) than those aged <65 years. Patients without insurance had a worse OS than those with insurance (HR 2.450, 95% CI 1.382–4.343, P=0.002). Patients who received chemotherapy (HR 0.581, 95% CI 0.454–0.743, P<0.001) and surgery (HR 0.463, 95% CI 0.367–0.584, P<0.001) had longer OS. The corresponding survival curve is displayed in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with only bone metastases based on chemotherapy and surgery: (A) overall survival and (B) breast cancer-specific survival based on chemotherapy; (C) overall survival and (D) breast cancer-specific survival based on surgery.

For patients with isolated lung metastasis, univariate Cox analyses indicated that age, chemotherapy, and surgery affected OS; chemotherapy and surgery remained apparent using multivariate Cox models (Supplementary Table 7). Chemotherapy (HR 0.374, 95% CI 0.290–0.481, P<0.001) and surgery (HR 0.561, 95% CI 0.445–0.709, P<0.001) were related to favorable OS for isolated lung metastasis patients. The corresponding survival curve is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with only lung metastases based on chemotherapy and surgery: (A) overall survival and (B) breast cancer-specific survival based on chemotherapy; (C) overall survival and (D) breast cancer-specific survival based on surgery.

For patients with isolated liver metastasis, univariate Cox models revealed that age, marital status, insurance, chemotherapy, and surgery were significant factors affecting survival (Supplementary Table 8). Multivariate Cox analysis suggested that having insurance, receiving chemotherapy, and undergoing surgery affected OS. Patients without insurance had a poorer OS than those with insurance (HR 2.323, 95% CI 1.007–5.326, P=0.048), and patients who received chemotherapy (HR 0.314, 95% CI 0.204–0.484, P<0.001) or surgery (HR 0.594, 95% CI 0.426–0.828, P=0.002) had a lower risk of mortality than those who did not receive these treatments. The corresponding survival curve is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with only liver metastases based on chemotherapy and surgery: (A) overall survival and (B) breast cancer-specific survival based on chemotherapy; (C) overall survival and (D) breast cancer-specific survival based on surgery.

Discussion

Our population-based analysis investigated the association between patterns of site-specific metastasis and survival in TNBC, as this is vital for making effective and appropriate clinical decisions. This study showed that metastatic sites were independent prognostic factors affecting OS and BCSS in de novo stage IV TNBC. The prognosis differed greatly in patients with different metastatic sites. Moreover, the number of metastatic sites significantly affected metastatic TNBC patients’ survival. For patients with isolated metastasis, surgery on the primary tumor led to better survival. Prognostic factors were also identified for patients with isolated bone, lung and liver metastases.

Our data suggest that common metastatic sites of TNBC include bone, lung and liver, while metastases to the brain are rare, which is consistent with previous studies [18,19]. The Kennecke et al. study, which included 318 TNBC patients, indicated that the metastasis rates for bone, lung, liver, and brain were 15.1%, 12.5%, 10.7%, and 7.2%, respectively [18]. Other studies have also shown that bone is the most common metastatic site for advanced breast cancer, followed by the lung, liver, and brain [20,21]. Thus, the distributions of common metastatic sites of TNBC are consistent with those of other advanced breast cancers. The results of our study provided additional details on survival for patients with organ-specific metastasis based on a larger sample size.

This study explored the impacts of metastasis to 4 organs on OS and BCSS in TNBC patients. We found that isolated bone metastases or isolated lung metastases were associated with better prognoses than was isolated liver metastasis, while isolated brain metastasis was associated with the poorest OS and BCSS of these single metastatic sites. A few studies explored the impacts of distant metastatic sites on survival. Kassam et al. showed that patients with visceral metastasis had worse OS than patients with non-visceral metastases (P=0.021) [8]. Lung and bone are common distant metastatic sites of TNBC. However, no studies to date have directly compared survival between bone metastases and lung metastases in patients with metastatic TNBC at diagnosis. In this study, no difference was evident between isolated bone metastases and isolated lung metastases in terms of survival, which was consistent with previous results for advanced breast cancer [22]. Moreover, patients with brain metastasis had a shorter survival than those with the other 3 distant metastatic sites, which is similar to previous studies (median OS: 7.3 months) [15], likely because some drugs used for treatment have difficulty crossing the blood-brain barrier. Accordingly, multimodal treatment may result in better survival for TNBC patients with bone or lung metastasis. The results of our study also indicated that the number of sites was a significant prognostic factor for metastatic TNBC. Both Kaplan-Meier and Cox analyses suggested that patients with multisite metastases had apparently shorter survival times than those with single-site metastasis. These observations may help clinicians more accurately estimate metastatic TNBC prognoses.

Several studies have reported prognostic factors for organ-specific metastasis in de novo metastatic TNBC. Bone is the most common metastatic site. This study suggested that age <65 years, insurance, chemotherapy, and surgery were favorable prognostic factors for patients with isolated bone metastasis. The median OS rates of young and elderly patients were 14 months and 8 months, respectively, while the corresponding median OS rates for insured and uninsured patients were 13 and 4 months, respectively. Thus, special treatment and management should be given to patients <65 years old who have insurance. The median OS was 19 months for patients who had surgery and 7 months for patients who did not. Accordingly, the median OS rates for cases with and those without chemotherapy were 14 and 3 months, respectively. These data suggest that chemotherapy and surgery significantly improved prognosis for patients with isolated bone metastasis.

Both chemotherapy and surgery were beneficial prognostic factors of OS for isolated lung metastasis patients. The median OS rates were 20 months with surgery and 11 months without surgery. The corresponding median OS rates were 18 months with chemotherapy and 5 months without chemotherapy. These data indicate that chemotherapy and surgery significantly improved prognosis for patients with isolated lung metastasis. Among the 4 distant metastatic sites we studied, isolated bone metastases and isolated lung metastases had the best prognosis; thus, these patients should receive chemotherapy and surgery immediately. However, for patients with oligometastatic lung metastasis, whether resection of metastases could improve patient survival remains to be further explored due to the lack of available data.

In this study, patients with isolated liver metastases had poorer prognoses than did patients with isolated bone or isolated lung metastases. The results showed that insurance, chemotherapy, and surgery were all favorable prognostic factors for isolated liver metastasis patients. The median OS rates of patients with and those without insurance were 14 months and 2 months, respectively. The median OS rates were 15 months for patients who had surgery and 7 months for those who did not, while the corresponding median OS rates were 15 months and 2 months for patients who had and those who did not have chemotherapy, respectively. Although the prognosis for patients with isolated liver metastases was poor, surgery and chemotherapy significantly improved the OS.

At present, chemotherapy remains the primary treatment for patients with metastatic TNBC [23,24]. In our study, approximately 25% of patients did not receive chemotherapy. This may be related to the lack of insurance for the patient, since about half of these patients had not received insurance. Also, other risks, such as patients with poor ECOG PS (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status), may also be a reason for patients without chemotherapy. Furthermore, about 36% of de novo metastatic TNBC patients received surgical resection of the primary tumor. This may be for palliative surgery because 25% of these patients received total mastectomy without nodal dissection. Our study demonstrated that surgery on the primary tumor combined with chemotherapy significantly prolonged survival of isolated metastatic patients. Previous studies showed that surgery on the primary tumor improved the survival outcomes for metastatic breast cancer patients at diagnosis [25–27]. However, specific information on the treatment sequence before and after surgery and chemotherapy was unavailable in the current SEER database. Therefore, determining which combination of treatment options could provide greater survival benefits is challenging. In addition, time lags occur with treatment. Some new treatments for TNBC, including targeted treatment and immunotherapy, have not yet entered mainstream practice, but they may be better treatment options for patients with metastatic TNBC.

Our study had several limitations. First, as a retrospective analysis, inherent bias was likely. Second, available variables provided by the SEER database were restricted. Information on the specific treatment of metastatic sites and systemic treatment details, such as information on adjuvant chemotherapy, surgery type, and treatment sequence were unrecorded. Detailed information on comorbidities and performance status was also not provided. This lack of information may have led to selection biases for patients receiving specialized treatment. The survival analyses in this study were based on cancer-specific survival (except for OS) to avoid the potential confounding effects of noncancer mortality due to unknown complications. Third, the SEER program included only 4 distant metastatic sites (brain, liver, lung, and bone) at initial diagnosis, and no further information regarding the time of secondary metastasis was available. Other metastatic sites were not recorded in the SEER program; therefore, no comments were included in the analysis. Fourth, the sample size for patients with brain metastasis was relatively small; therefore, no subgroup analyses of other variables were performed, because if subgroup analyses had included patients with brain metastasis, the number of samples in each subgroup would have been too small. Finally, all patients enrolled were from the United States rather than from the global population; therefore, these findings should be confirmed in other population-based cohorts worldwide.

Conclusions

This population-based study suggested that distant metastatic sites were independent predictors of survival in metastatic TNBC at diagnosis. Compared with other metastatic sites, patients with only brain metastasis had the shortest survival rates, while patients with isolated bone or lung metastases survived longer than those with isolated liver metastases. Moreover, surgery and chemotherapy significantly improved the prognosis of patients with site-specific metastases. For patients with isolated bone metastasis, age <65 years, insurance, chemotherapy, and surgery were favorable prognostic factors, while chemotherapy and surgery were associated with better OS for isolated lung metastases. Knowledge of the differences in metastatic patterns contributes to better pretreatment assessments of patients with metastatic TNBC and to better decisions regarding appropriate treatments. Additionally, further studies are warranted to identify subgroups of patients with isolated metastasis who may benefit from surgery of the primary tumor.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table 1.

Clinical features of de novo stage IV triple-negative breast cancer patients by metastatic sites.

| Features | Bone metastases (%) | P- value | Lung metastases (%) | P- value | Liver metastases (%) | P- value | Brain metastases (%) | P- value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| Age (years) | 0.138 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| <65 | 623 (62.5) | 527 (59.1) | 540 (57.9) | 610 (63.8) | 416 (65.4) | 734 (58.6) | 188 (70.1) | 962 (59.4) | ||||

| ≥65 | 374 (37.5) | 364 (40.9) | 392 (42.1) | 346 (36.2) | 220 (34.6) | 518 (41.4) | 80 (29.9) | 658 (40.6) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Race | 0.261 | 0.099 | 0.644 | 0.726 | ||||||||

| White | 695 (69.7) | 590 (66.2) | 615 (66.0) | 670 (70.1) | 440 (69.2) | 845 (67.5) | 187 (69.8) | 1098 (67.8) | ||||

| Black | 242 (24.3) | 239 (26.8) | 248 (26.6) | 233 (24.4) | 159 (25.0) | 322 (25.7) | 63 (23.5) | 418 (25.8) | ||||

| Others | 60 (6.0) | 62 (7.0) | 69 (7.4) | 53 (5.5) | 37 (5.8) | 85 (6.8) | 18 (6.7) | 104 (6.4) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Grade | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.349 | 0.167 | ||||||||

| G1/G2 | 186 (18.7) | 101 (11.3) | 113 (12.1) | 174 (18.2) | 97 (15.3) | 190 (15.2) | 36 (13.4) | 251 (15.5) | ||||

| G3/G4 | 644 (64.6) | 661 (74.2) | 678 (72.7) | 627 (65.6) | 450 (70.8) | 855 (68.3) | 180 (67.2) | 1125 (69.4) | ||||

| Unknown | 167 (16.8) | 129 (14.5) | 141 (15.1) | 155 (16.2) | 89 (14.0) | 207 (16.5) | 52 (19.4) | 244 (15.1) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.291 | 0.041 | ||||||||

| ≤2 | 155 (15.5) | 112 (12.6) | 113 (12.1) | 154 (16.1) | 90 (14.2) | 177 (14.1) | 49 (18.3) | 218 (13.5) | ||||

| 2–5 | 333 (33.4) | 292 (32.8) | 284 (30.5) | 341 (35.7) | 225 (35.4) | 400 (31.9) | 77 (28.7) | 548 (33.8) | ||||

| >5 | 310 (31.1) | 373 (41.9) | 393 (42.2) | 290 (30.3) | 228 (35.8) | 455 (36.3) | 89 (33.2) | 594 (36.7) | ||||

| Unknown | 199 (20.0) | 114 (12.8) | 142 (15.2) | 171 (17.9) | 93 (14.6) | 220 (17.6) | 53 (19.8) | 260 (16.0) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Node stage | 0.447 | 0.120 | 0.150 | 0.004 | ||||||||

| Node negative | 228 (22.9) | 214 (24.0) | 229 (24.6) | 213 (22.3) | 134 (21.1) | 308 (24.6) | 45 (16.8) | 397 (24.5) | ||||

| Node positive | 691 (69.3) | 620 (69.6) | 628 (67.4) | 683 (71.4) | 460 (72.3) | 851 (68.0) | 195 (72.8) | 1116 (68.9) | ||||

| Unknown | 78 (7.8) | 57 (6.4) | 75 (8.0) | 60 (6.3) | 42 (6.6) | 93 (7.4) | 28 (10.4) | 107 (6.6) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Surgery of the primary | <0.001 | 0.082 | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 305 (30.6) | 376 (42.2) | 318 (34.1) | 363 (38.0) | 199 (31.3) | 482 (38.5) | 54 (20.1) | 627 (38.7) | ||||

| No | 692 (69.4) | 515 (57.8) | 614 (65.9) | 593 (62.0) | 437 (68.7) | 770 (61.5) | 214 (79.9) | 993 (61.3) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.579 | 0.128 | 0.394 | 0.158 | ||||||||

| Yes | 722 (72.4) | 635 (71.3) | 655 (70.3) | 702 (73.4) | 465 (73.1) | 892 (71.2) | 183 (68.3) | 1174 (72.5) | ||||

| No/unknown | 275 (27.6) | 256 (28.7) | 277 (29.7) | 254 (26.6) | 171 (26.9) | 360 (28.8) | 85 (31.7) | 446 (27.5) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Insurance | 0.430 | 0.115 | 0.466 | 0.213 | ||||||||

| Yes | 948 (95.1) | 835 (93.7) | 870 (93.3) | 913 (95.5) | 595 (93.6) | 1188 (94.9) | 247 (92.2) | 1536 (94.8) | ||||

| No | 40 (4.0) | 46 (5.2) | 50 (5.4) | 36 (3.8) | 33 (5.2) | 53 (4.2) | 17 (6.3) | 69 (4.3) | ||||

| Unknown | 9 (0.9) | 10 (1.1) | 12 (1.3) | 7 (0.7) | 8 (1.3) | 11 (0.9) | 4 (1.5) | 15 (0.9) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Marital status | 0.299 | 0.010 | 0.826 | 0.215 | ||||||||

| Married | 431 (43.2) | 373 (41.9) | 367 (39.4) | 437 (45.7) | 274 (43.1) | 530 (42.3) | 117 (43.7) | 687 (42.4) | ||||

| Unmarried | 526 (52.8) | 469 (52.6) | 513 (55.0) | 482 (50.4) | 330 (51.9) | 665 (53.1) | 144 (53.7) | 851 (52.5) | ||||

| Unknown | 40 (4.0) | 49 (5.5) | 52 (5.6) | 37 (3.9) | 32 (5.0) | 57 (4.6) | 7 (2.6) | 82 (5.1) | ||||

Supplementary Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of de novo stage IV triple-negative breast cancer patients by the number of metastatic sites.

| Features | Level | 1 site (%) | >1 site (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <65 | 691 (58.7) | 459 (64.6) | 0.012 |

| ≥65 | 486 (41.3) | 252 (35.4) | ||

|

| ||||

| Race | White | 795 (67.5) | 490 (68.9) | 0.824 |

| Black | 305 (25.9) | 176 (24.8) | ||

| Others | 77 (6.5) | 45 (6.3) | ||

|

| ||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | 177 (15.0) | 110 (15.5) | 0.968 |

| G3/G4 | 815 (69.2) | 490 (68.9) | ||

| Unknown | 185 (15.7) | 111 (15.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | 168 (14.3) | 99 (13.9) | 0.565 |

| 2–5 | 399 (33.9) | 226 (31.8) | ||

| >5 | 425 (36.1) | 258 (36.3) | ||

| Unknown | 185 (15.7) | 128 (18.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Node stage | Node negative | 295 (25.1) | 147 (20.7) | 0.020 |

| Node positive | 809 (68.7) | 502 (70.6) | ||

| Unknown | 73 (6.2) | 62 (8.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Surgery of the primary | Yes | 521 (44.3) | 160 (22.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 656 (55.7) | 551 (77.5) | ||

|

| ||||

| Chemotherapy | Yes | 843 (71.6) | 514 (72.3) | 0.754 |

| No/unknown | 334 (28.4) | 197 (27.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Insurance | Yes | 1118 (95.0) | 665 (93.5) | 0.402 |

| No | 48 (4.1) | 38 (5.3) | ||

| Unknown | 11 (0.9) | 8 (1.1) | ||

|

| ||||

| Marital status | Married | 512 (43.5) | 292 (41.1) | 0.556 |

| Unmarried | 609 (51.7) | 386 (54.3) | ||

| Unknown | 56 (4.8) | 33 (4.6) | ||

Supplementary Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for cancer-specific survival of patients with de novo stage IV triple-negative breast cancer.

| Features | Level | One site of distant metastases | Entire cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | <65 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| ≥65 | 1.230 (1.049–1.441) | 0.011 | 0.972 (0.820–1.151) | 0.739 | 1.216 (1.076–1.375) | 0.002 | 1.036 (0.911–1.178) | 0.590 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Race | White | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| Black | 0.977 (0.819–1.166) | 0.799 | – | – | 1.038 (0.907–1.189) | 0.589 | – | – | |

| Others | 0.898 (0.654–1.233) | 0.505 | – | – | 0.877 (0.680–1.130) | 0.310 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| G3/G4 | 1.007 (0.804–1.260) | 0.955 | – | – | 0.964 (0.814–1.142) | 0.674 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| 2–5 | 0.996 (0.770–1.287) | 0.973 | – | – | 0.962 (0.788–1.175) | 0.703 | – | – | |

| >5 | 1.068 (0.831–1.374) | 0.607 | – | – | 1.032 (0.849–1.255) | 0.750 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Node stage | Node negative | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| Node positive | 1.103 (0.908–1.341) | 0.323 | – | – | 1.014 (0.872–1.179) | 0.857 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Surgery of the primary | No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.502 (0.429–0.589) | <0.001 | 0.529 (0.450–0.621) | <0.001 | 0.502 (0.442–0.570) | <0.001 | 0.595 (0.522–0.679) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Chemo-therapy | No/unknown | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.399 (0.337–0.473) | <0.001 | 0.426 (0.354–0.512) | <0.001 | 0.383 (0.336–0.437) | <0.001 | 0.401 (0.350–0.461) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Insurance | Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| No | 2.237 (1.589–3.150) | <0.001 | 2.032 (1.427–2.892) | <0.001 | 1.861 (1.447–2.392) | <0.001 | 1.729 (1.337–2.237) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Marital status | Married | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Unmarried | 1.292 (1.101–1.516) | 0.002 | 1.185 (1.007–1.395) | 0.041 | 1.323 (1.170–1.496) | <0.001 | 1.183 (1.045–1.341) | 0.008 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Metastatic sites | Brian | Ref | Ref | – | – | ||||

| Bone | 0.580 (0.427–0.788) | <0.001 | 0.533 (0.391–0.726) | <0.001 | – | – | – | – | |

| Lung | 0.603 (0.443–0.821) | <0.001 | 0.544 (0.399–0.743) | <0.001 | – | – | – | – | |

| Liver | 0.676 (0.483–0.945) | 0.022 | 0.698 (0.498–0.978) | 0.037 | – | – | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | 1 | – | – | Ref | Ref | ||||

| >1 | – | – | – | – | 1.708 (1.512–1.929) | <0.001 | 1.584 (1.397–1.797) | <0.001 | |

Supplementary Table 4.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the impact of metastatic sites on overall survival when using metastasis of bone, lung, liver as the reference group.

| Features | Level | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic sites | Bone | Ref | |

| Lung | 0.970 (0.829–1.134) | 0.699 | |

| Liver | 1.299 (1.069–1.577) | 0.008 | |

| Brain | 1.938 (1.472–2.551) | <0.001 | |

| Metastatic sites | Lung | Ref | |

| Bone | 1.031 (0.882–1.206) | 0.699 | |

| Brain | 1.998 (1.513–2.640) | <0.001 | |

| Liver | 1.339 (1.098–1.634) | 0.004 | |

| Metastatic sites | Liver | Ref | |

| Lung | 0.747 (0.612–0.911) | 0.004 | |

| Bone | 0.770 (0.634–0.935) | 0.008 | |

| Brain | 1.492 (1.105–2.014) | 0.009 |

Supplementary Table 5.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the impact of metastatic sites on cancer-specific survival when using metastasis of bone, lung, liver as the reference group.

| Features | Level | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic sites | Bone | Ref | |

| Lung | 1.022 (0.854–1.223) | 0.815 | |

| Liver | 1.310 (1.047–1.640) | 0.018 | |

| Brain | 1.877 (1.378–2.556) | <0.001 | |

| Metastatic sites | Lung | Ref | |

| Bone | 0.979 (0.818–1.171) | 0.815 | |

| Brain | 1.837 (1.346–2.507) | <0.001 | |

| Liver | 1.282 (1.021–1.610) | 0.032 | |

| Metastatic sites | Liver | Ref | |

| Lung | 0.780 (0.621–0.979) | 0.032 | |

| Bone | 0.763 (0.610–0.955) | 0.018 | |

| Brain | 1.432 (1.022–2.008) | 0.037 |

Supplementary Table 6.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with only bone metastases.

| Features | Level | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | <65 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥65 | 1.564 (1.262–1.939) | <0.001 | 1.356 (1.083–1.696) | 0.008 | |

|

| |||||

| Race | White | Ref | – | ||

| Black | 1.014 (0.793–1.298) | 0.911 | – | – | |

| Others | 0.971 (0.614–1.536) | 0.901 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | Ref | – | ||

| G3/G4 | 0.988 (0.751–1.299) | 0.929 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | Ref | – | ||

| 2–5 | 0.880 (0.638–1.212) | 0.433 | – | – | |

| >5 | 1.032 (0.743–1.434) | 0.852 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Node stage | Node negative | Ref | – | ||

| Node positive | 1.161 (0.899–1.500) | 0.253 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Surgery of the primary | No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.422 (0.336–0.531) | <0.001 | 0.463 (0.367–0.584) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy | No/unknown | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.451 (0.359–0.567) | <0.001 | 0.581 (0.454–0.743) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Insurance | Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| No | 2.542 (1.454–4.444) | 0.001 | 2.450 (1.382–4.343) | 0.002 | |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | Married | Ref | Ref | ||

| Unmarried | 1.344 (1.079–1.675) | 0.008 | 1.155 (0.923–1.445) | 0.207 | |

Supplementary Table 7.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with only lung metastases.

| Features | Level | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | <65 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥65 | 1.259 (1.002–1.581) | 0.048 | 0.907 (0.712–1.155) | 0.427 | |

|

| |||||

| Race | White | Ref | – | – | |

| Black | 1.096 (0.849–1.415) | 0.480 | – | – | |

| Others | 1.070 (0.694–1.650) | 0.759 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | Ref | – | – | |

| G3/G4 | 0.800 (0.545–1.173) | 0.253 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | Ref | – | – | |

| 2–5 | 1.016 (0.677–1.523) | 0.940 | – | – | |

| >5 | 1.104 (0.750–1.623) | 0.616 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Node stage | Node negative | Ref | – | – | |

| Node positive | 0.941 (0.723–1.225) | 0.653 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Surgery of the primary | No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.535 (0.424–0.673) | <0.001 | 0.561 (0.445–0.709) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy | No/unknown | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.368 (0.290–0.468) | <0.001 | 0.374 (0.290–0.481) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Insurance | Yes | Ref | – | – | |

| No | 1.194 (0.721–1.977) | 0.492 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | Married | Ref | – | – | |

| Unmarried | 1.156 (0.911–1.466) | 0.233 | – | – | |

Supplementary Table 8.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with only liver metastases.

| Features | Level | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | <65 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥65 | 1.700 (1.211–2.388) | 0.002 | 1.306 (0.902–1.892) | 0.158 | |

|

| |||||

| Race | White | Ref | – | – | |

| Black | 1.190 (0.833–1.698) | 0.339 | – | – | |

| Others | 1.188 (0.550–2.565) | 0.661 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | Ref | – | – | |

| G3/G4 | 1.110 (0.707–1.743) | 0.650 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | Ref | – | – | |

| 2–5 | 1.614 (0.962–2.708) | 0.070 | – | – | |

| >5 | 1.342 (0.793–2.273) | 0.273 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Node stage | Node negative | Ref | – | – | |

| Node positive | 0.754 (0.515–1.103) | 0.146 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Surgery of the primary | No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.549 (0.397–0.760) | <0.001 | 0.594 (0.426–0.828) | 0.002 | |

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy | No/unknown | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.279 (0.191–0.409) | <0.001 | 0.314 (0.204–0.484) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Insurance | Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| No | 3.347 (1.537–7.287) | 0.002 | 2.323 (1.007–5.326) | 0.048 | |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | Married | Ref | Ref | 0.088 | |

| Unmarried | 1.424 (1.022–1.983) | 0.037 | 1.338 (0.958–1.869) | ||

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, et al. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:93–99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma P. Biology and management of patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21:1050–62. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3997–4013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liedtke C, Mazouni C, Hess KR, et al. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1275–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurvitz S, Mead M. Triple-negative breast cancer: Advancements in characterization and treatment approach. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;28:59–69. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassam F, Enright K, Dent R, et al. Survival outcomes for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: Implications for clinical practice and trial design. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9:29–33. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2009.n.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao S, Ma D, Xiao Y, et al. Clinicopathologic features and prognoses of different histologic types of triple-negative breast cancer: A large population-based analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:420–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu XC, Zhang J, Xu BH, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus paclitaxel plus gemcitabine as first-line therapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (CBCSG006): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:436–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Zhang C, Zhang J, et al. The prognosis analysis of different metastasis pattern in patients with different breast cancer subtypes: A SEER based study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:26368–79. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rakha EA, Chan S. Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2011;23:587–600. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anders CK, Carey LA. Biology, metastatic patterns, and treatment of patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(Suppl 2):S73–81. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2009.s.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tischkowitz M, Brunet JS, Begin LR, et al. Use of immunohistochemical markers can refine prognosis in triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin J, Gao Y, Zhang J, et al. Incidence, pattern and prognosis of brain metastases in patients with metastatic triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:446. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4371-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER* Stat Database: Incidence – SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2017 Sub (1973–2015 varying) – linked to county attributes – Total U.S., 1969–2016 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released April 2018, based on the November 2017 submission. Available online: http://www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 17.Swede H, Sarwar A, Magge A, et al. Mortality risk from comorbidities independent of triple-negative breast cancer status: NCI-SEER-based cohort analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:627–36. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0736-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R, et al. Metastatic behavior of breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3271–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu SG, Sun JY, Yang LC, et al. Patterns of distant metastasis in Chinese women according to breast cancer subtypes. Oncotarget. 2016;7:47975–84. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao H, Hartman M, Bhoo-Pathy N, et al. Predicting survival of de novo metastatic breast cancer in Asian women: systematic review and validation study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holzel D, Eckel R, Bauerfeind I, et al. Survival of de novo stage IV breast cancer patients over three decades. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:509–19. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2306-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ording AG, Heide-Jorgensen U, Christiansen CF, et al. Site of metastasis and breast cancer mortality: A Danish nationwide registry-based cohort study. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2017;34:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s10585-016-9824-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Lin Y, Sun XJ, et al. Biomarker assessment of the CBCSG006 trial: A randomized phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine compared with paclitaxel plus gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1741–47. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stover DG, Parsons HA, Ha G, et al. Association of cell-free DNA tumor fraction and somatic copy number alterations with survival in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:543–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warschkow R, Guller U, Tarantino I, et al. Improved survival after primary tumor surgery in metastatic breast cancer: A propensity-adjusted, population-based SEER trend analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;263:1188–98. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pathy NB, Verkooijen HM, Taib NA, et al. Impact of breast surgery on survival in women presenting with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1566–72. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hazard HW, Gorla SR, Scholtens D, et al. Surgical resection of the primary tumor, chest wall control, and survival in women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:2011–19. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

Clinical features of de novo stage IV triple-negative breast cancer patients by metastatic sites.

| Features | Bone metastases (%) | P- value | Lung metastases (%) | P- value | Liver metastases (%) | P- value | Brain metastases (%) | P- value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| Age (years) | 0.138 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| <65 | 623 (62.5) | 527 (59.1) | 540 (57.9) | 610 (63.8) | 416 (65.4) | 734 (58.6) | 188 (70.1) | 962 (59.4) | ||||

| ≥65 | 374 (37.5) | 364 (40.9) | 392 (42.1) | 346 (36.2) | 220 (34.6) | 518 (41.4) | 80 (29.9) | 658 (40.6) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Race | 0.261 | 0.099 | 0.644 | 0.726 | ||||||||

| White | 695 (69.7) | 590 (66.2) | 615 (66.0) | 670 (70.1) | 440 (69.2) | 845 (67.5) | 187 (69.8) | 1098 (67.8) | ||||

| Black | 242 (24.3) | 239 (26.8) | 248 (26.6) | 233 (24.4) | 159 (25.0) | 322 (25.7) | 63 (23.5) | 418 (25.8) | ||||

| Others | 60 (6.0) | 62 (7.0) | 69 (7.4) | 53 (5.5) | 37 (5.8) | 85 (6.8) | 18 (6.7) | 104 (6.4) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Grade | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.349 | 0.167 | ||||||||

| G1/G2 | 186 (18.7) | 101 (11.3) | 113 (12.1) | 174 (18.2) | 97 (15.3) | 190 (15.2) | 36 (13.4) | 251 (15.5) | ||||

| G3/G4 | 644 (64.6) | 661 (74.2) | 678 (72.7) | 627 (65.6) | 450 (70.8) | 855 (68.3) | 180 (67.2) | 1125 (69.4) | ||||

| Unknown | 167 (16.8) | 129 (14.5) | 141 (15.1) | 155 (16.2) | 89 (14.0) | 207 (16.5) | 52 (19.4) | 244 (15.1) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.291 | 0.041 | ||||||||

| ≤2 | 155 (15.5) | 112 (12.6) | 113 (12.1) | 154 (16.1) | 90 (14.2) | 177 (14.1) | 49 (18.3) | 218 (13.5) | ||||

| 2–5 | 333 (33.4) | 292 (32.8) | 284 (30.5) | 341 (35.7) | 225 (35.4) | 400 (31.9) | 77 (28.7) | 548 (33.8) | ||||

| >5 | 310 (31.1) | 373 (41.9) | 393 (42.2) | 290 (30.3) | 228 (35.8) | 455 (36.3) | 89 (33.2) | 594 (36.7) | ||||

| Unknown | 199 (20.0) | 114 (12.8) | 142 (15.2) | 171 (17.9) | 93 (14.6) | 220 (17.6) | 53 (19.8) | 260 (16.0) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Node stage | 0.447 | 0.120 | 0.150 | 0.004 | ||||||||

| Node negative | 228 (22.9) | 214 (24.0) | 229 (24.6) | 213 (22.3) | 134 (21.1) | 308 (24.6) | 45 (16.8) | 397 (24.5) | ||||

| Node positive | 691 (69.3) | 620 (69.6) | 628 (67.4) | 683 (71.4) | 460 (72.3) | 851 (68.0) | 195 (72.8) | 1116 (68.9) | ||||

| Unknown | 78 (7.8) | 57 (6.4) | 75 (8.0) | 60 (6.3) | 42 (6.6) | 93 (7.4) | 28 (10.4) | 107 (6.6) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Surgery of the primary | <0.001 | 0.082 | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 305 (30.6) | 376 (42.2) | 318 (34.1) | 363 (38.0) | 199 (31.3) | 482 (38.5) | 54 (20.1) | 627 (38.7) | ||||

| No | 692 (69.4) | 515 (57.8) | 614 (65.9) | 593 (62.0) | 437 (68.7) | 770 (61.5) | 214 (79.9) | 993 (61.3) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.579 | 0.128 | 0.394 | 0.158 | ||||||||

| Yes | 722 (72.4) | 635 (71.3) | 655 (70.3) | 702 (73.4) | 465 (73.1) | 892 (71.2) | 183 (68.3) | 1174 (72.5) | ||||

| No/unknown | 275 (27.6) | 256 (28.7) | 277 (29.7) | 254 (26.6) | 171 (26.9) | 360 (28.8) | 85 (31.7) | 446 (27.5) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Insurance | 0.430 | 0.115 | 0.466 | 0.213 | ||||||||

| Yes | 948 (95.1) | 835 (93.7) | 870 (93.3) | 913 (95.5) | 595 (93.6) | 1188 (94.9) | 247 (92.2) | 1536 (94.8) | ||||

| No | 40 (4.0) | 46 (5.2) | 50 (5.4) | 36 (3.8) | 33 (5.2) | 53 (4.2) | 17 (6.3) | 69 (4.3) | ||||

| Unknown | 9 (0.9) | 10 (1.1) | 12 (1.3) | 7 (0.7) | 8 (1.3) | 11 (0.9) | 4 (1.5) | 15 (0.9) | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Marital status | 0.299 | 0.010 | 0.826 | 0.215 | ||||||||

| Married | 431 (43.2) | 373 (41.9) | 367 (39.4) | 437 (45.7) | 274 (43.1) | 530 (42.3) | 117 (43.7) | 687 (42.4) | ||||

| Unmarried | 526 (52.8) | 469 (52.6) | 513 (55.0) | 482 (50.4) | 330 (51.9) | 665 (53.1) | 144 (53.7) | 851 (52.5) | ||||

| Unknown | 40 (4.0) | 49 (5.5) | 52 (5.6) | 37 (3.9) | 32 (5.0) | 57 (4.6) | 7 (2.6) | 82 (5.1) | ||||

Supplementary Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of de novo stage IV triple-negative breast cancer patients by the number of metastatic sites.

| Features | Level | 1 site (%) | >1 site (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <65 | 691 (58.7) | 459 (64.6) | 0.012 |

| ≥65 | 486 (41.3) | 252 (35.4) | ||

|

| ||||

| Race | White | 795 (67.5) | 490 (68.9) | 0.824 |

| Black | 305 (25.9) | 176 (24.8) | ||

| Others | 77 (6.5) | 45 (6.3) | ||

|

| ||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | 177 (15.0) | 110 (15.5) | 0.968 |

| G3/G4 | 815 (69.2) | 490 (68.9) | ||

| Unknown | 185 (15.7) | 111 (15.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | 168 (14.3) | 99 (13.9) | 0.565 |

| 2–5 | 399 (33.9) | 226 (31.8) | ||

| >5 | 425 (36.1) | 258 (36.3) | ||

| Unknown | 185 (15.7) | 128 (18.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Node stage | Node negative | 295 (25.1) | 147 (20.7) | 0.020 |

| Node positive | 809 (68.7) | 502 (70.6) | ||

| Unknown | 73 (6.2) | 62 (8.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Surgery of the primary | Yes | 521 (44.3) | 160 (22.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 656 (55.7) | 551 (77.5) | ||

|

| ||||

| Chemotherapy | Yes | 843 (71.6) | 514 (72.3) | 0.754 |

| No/unknown | 334 (28.4) | 197 (27.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Insurance | Yes | 1118 (95.0) | 665 (93.5) | 0.402 |

| No | 48 (4.1) | 38 (5.3) | ||

| Unknown | 11 (0.9) | 8 (1.1) | ||

|

| ||||

| Marital status | Married | 512 (43.5) | 292 (41.1) | 0.556 |

| Unmarried | 609 (51.7) | 386 (54.3) | ||

| Unknown | 56 (4.8) | 33 (4.6) | ||

Supplementary Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for cancer-specific survival of patients with de novo stage IV triple-negative breast cancer.

| Features | Level | One site of distant metastases | Entire cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | <65 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| ≥65 | 1.230 (1.049–1.441) | 0.011 | 0.972 (0.820–1.151) | 0.739 | 1.216 (1.076–1.375) | 0.002 | 1.036 (0.911–1.178) | 0.590 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Race | White | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| Black | 0.977 (0.819–1.166) | 0.799 | – | – | 1.038 (0.907–1.189) | 0.589 | – | – | |

| Others | 0.898 (0.654–1.233) | 0.505 | – | – | 0.877 (0.680–1.130) | 0.310 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| G3/G4 | 1.007 (0.804–1.260) | 0.955 | – | – | 0.964 (0.814–1.142) | 0.674 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| 2–5 | 0.996 (0.770–1.287) | 0.973 | – | – | 0.962 (0.788–1.175) | 0.703 | – | – | |

| >5 | 1.068 (0.831–1.374) | 0.607 | – | – | 1.032 (0.849–1.255) | 0.750 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Node stage | Node negative | Ref | – | Ref | – | ||||

| Node positive | 1.103 (0.908–1.341) | 0.323 | – | – | 1.014 (0.872–1.179) | 0.857 | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Surgery of the primary | No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.502 (0.429–0.589) | <0.001 | 0.529 (0.450–0.621) | <0.001 | 0.502 (0.442–0.570) | <0.001 | 0.595 (0.522–0.679) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Chemo-therapy | No/unknown | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.399 (0.337–0.473) | <0.001 | 0.426 (0.354–0.512) | <0.001 | 0.383 (0.336–0.437) | <0.001 | 0.401 (0.350–0.461) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Insurance | Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| No | 2.237 (1.589–3.150) | <0.001 | 2.032 (1.427–2.892) | <0.001 | 1.861 (1.447–2.392) | <0.001 | 1.729 (1.337–2.237) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Marital status | Married | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Unmarried | 1.292 (1.101–1.516) | 0.002 | 1.185 (1.007–1.395) | 0.041 | 1.323 (1.170–1.496) | <0.001 | 1.183 (1.045–1.341) | 0.008 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Metastatic sites | Brian | Ref | Ref | – | – | ||||

| Bone | 0.580 (0.427–0.788) | <0.001 | 0.533 (0.391–0.726) | <0.001 | – | – | – | – | |

| Lung | 0.603 (0.443–0.821) | <0.001 | 0.544 (0.399–0.743) | <0.001 | – | – | – | – | |

| Liver | 0.676 (0.483–0.945) | 0.022 | 0.698 (0.498–0.978) | 0.037 | – | – | – | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | 1 | – | – | Ref | Ref | ||||

| >1 | – | – | – | – | 1.708 (1.512–1.929) | <0.001 | 1.584 (1.397–1.797) | <0.001 | |

Supplementary Table 4.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the impact of metastatic sites on overall survival when using metastasis of bone, lung, liver as the reference group.

| Features | Level | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic sites | Bone | Ref | |

| Lung | 0.970 (0.829–1.134) | 0.699 | |

| Liver | 1.299 (1.069–1.577) | 0.008 | |

| Brain | 1.938 (1.472–2.551) | <0.001 | |

| Metastatic sites | Lung | Ref | |

| Bone | 1.031 (0.882–1.206) | 0.699 | |

| Brain | 1.998 (1.513–2.640) | <0.001 | |

| Liver | 1.339 (1.098–1.634) | 0.004 | |

| Metastatic sites | Liver | Ref | |

| Lung | 0.747 (0.612–0.911) | 0.004 | |

| Bone | 0.770 (0.634–0.935) | 0.008 | |

| Brain | 1.492 (1.105–2.014) | 0.009 |

Supplementary Table 5.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the impact of metastatic sites on cancer-specific survival when using metastasis of bone, lung, liver as the reference group.

| Features | Level | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic sites | Bone | Ref | |

| Lung | 1.022 (0.854–1.223) | 0.815 | |

| Liver | 1.310 (1.047–1.640) | 0.018 | |

| Brain | 1.877 (1.378–2.556) | <0.001 | |

| Metastatic sites | Lung | Ref | |

| Bone | 0.979 (0.818–1.171) | 0.815 | |

| Brain | 1.837 (1.346–2.507) | <0.001 | |

| Liver | 1.282 (1.021–1.610) | 0.032 | |

| Metastatic sites | Liver | Ref | |

| Lung | 0.780 (0.621–0.979) | 0.032 | |

| Bone | 0.763 (0.610–0.955) | 0.018 | |

| Brain | 1.432 (1.022–2.008) | 0.037 |

Supplementary Table 6.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with only bone metastases.

| Features | Level | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | <65 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥65 | 1.564 (1.262–1.939) | <0.001 | 1.356 (1.083–1.696) | 0.008 | |

|

| |||||

| Race | White | Ref | – | ||

| Black | 1.014 (0.793–1.298) | 0.911 | – | – | |

| Others | 0.971 (0.614–1.536) | 0.901 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | Ref | – | ||

| G3/G4 | 0.988 (0.751–1.299) | 0.929 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | Ref | – | ||

| 2–5 | 0.880 (0.638–1.212) | 0.433 | – | – | |

| >5 | 1.032 (0.743–1.434) | 0.852 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Node stage | Node negative | Ref | – | ||

| Node positive | 1.161 (0.899–1.500) | 0.253 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Surgery of the primary | No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.422 (0.336–0.531) | <0.001 | 0.463 (0.367–0.584) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy | No/unknown | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.451 (0.359–0.567) | <0.001 | 0.581 (0.454–0.743) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Insurance | Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| No | 2.542 (1.454–4.444) | 0.001 | 2.450 (1.382–4.343) | 0.002 | |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | Married | Ref | Ref | ||

| Unmarried | 1.344 (1.079–1.675) | 0.008 | 1.155 (0.923–1.445) | 0.207 | |

Supplementary Table 7.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with only lung metastases.

| Features | Level | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | <65 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥65 | 1.259 (1.002–1.581) | 0.048 | 0.907 (0.712–1.155) | 0.427 | |

|

| |||||

| Race | White | Ref | – | – | |

| Black | 1.096 (0.849–1.415) | 0.480 | – | – | |

| Others | 1.070 (0.694–1.650) | 0.759 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | Ref | – | – | |

| G3/G4 | 0.800 (0.545–1.173) | 0.253 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | Ref | – | – | |

| 2–5 | 1.016 (0.677–1.523) | 0.940 | – | – | |

| >5 | 1.104 (0.750–1.623) | 0.616 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Node stage | Node negative | Ref | – | – | |

| Node positive | 0.941 (0.723–1.225) | 0.653 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Surgery of the primary | No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.535 (0.424–0.673) | <0.001 | 0.561 (0.445–0.709) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy | No/unknown | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.368 (0.290–0.468) | <0.001 | 0.374 (0.290–0.481) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Insurance | Yes | Ref | – | – | |

| No | 1.194 (0.721–1.977) | 0.492 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | Married | Ref | – | – | |

| Unmarried | 1.156 (0.911–1.466) | 0.233 | – | – | |

Supplementary Table 8.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with only liver metastases.

| Features | Level | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | <65 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥65 | 1.700 (1.211–2.388) | 0.002 | 1.306 (0.902–1.892) | 0.158 | |

|

| |||||

| Race | White | Ref | – | – | |

| Black | 1.190 (0.833–1.698) | 0.339 | – | – | |

| Others | 1.188 (0.550–2.565) | 0.661 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Grade | G1/G2 | Ref | – | – | |

| G3/G4 | 1.110 (0.707–1.743) | 0.650 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 | Ref | – | – | |

| 2–5 | 1.614 (0.962–2.708) | 0.070 | – | – | |

| >5 | 1.342 (0.793–2.273) | 0.273 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Node stage | Node negative | Ref | – | – | |

| Node positive | 0.754 (0.515–1.103) | 0.146 | – | – | |

|

| |||||

| Surgery of the primary | No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.549 (0.397–0.760) | <0.001 | 0.594 (0.426–0.828) | 0.002 | |

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy | No/unknown | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.279 (0.191–0.409) | <0.001 | 0.314 (0.204–0.484) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Insurance | Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| No | 3.347 (1.537–7.287) | 0.002 | 2.323 (1.007–5.326) | 0.048 | |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | Married | Ref | Ref | 0.088 | |

| Unmarried | 1.424 (1.022–1.983) | 0.037 | 1.338 (0.958–1.869) | ||