Abstract

Dominant missense mutations in the amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein (APP) gene have been implicated in early onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD). These mutations alter protein structure to favor the pathologic production of Aβ. We report that homozygous nonsense mutations in APP are associated with decreased somatic growth, microcephaly, hypotonia, developmental delay, thinning of the corpus callosum, and seizures. We compare the phenotype of this case to those reported in mouse models and demonstrate multiple similarities strengthening the role of the amyloid precursor protein in normal brain function and development.

Keywords: Amyloid-β peptide (Aβ), Alzheimer disease (AD), seizures, microcephaly, corpus callosum, dysmyelination, mouse model, genotype-phenotype correlation

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease, which manifests as progressive memory deterioration and other cognitive decline. Genetic factors that predispose to classic AD as well as early onset AD have previously been described. One genetic predisposition for early onset AD is due to mutations in the gene encoding for amyloid precursor protein (APP) resulting in alterations to the amyloid-β peptide (Aβ)1, 2. Aβ is a 39–43-residue product of proteolysis of APP, which is an integral membrane protein with a long extracellular amino-terminal domain, a single transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic tail3. The APP gene on chromosome 21q, is a 400 kb gene that is spliced to produce isoforms ranging from 365 to 770 amino acid residues. Studies in mouse models have ascertained that in the constitutive secretory pathway, APP is cleaved within the Aβ region, to form secreted neuroprotective products included but not limted to sAPPα4. Through alternative pathways, the protein may be internalized to an endosome where intact Aβ is produced, or Aβ may be secreted from cells and found in the cerebrospinal fluid of both AD and healthy individuals5. Most mutations in this gene are located just outside of the Aβ region of the protein and are associated with autosomal-dominant early onset AD6. Interestingly, to date there have been no reports of human homozygous nonsense or frameshift mutations in the APP gene.

Methods

This study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) chromosomal microarray:

The chromosomal microarray platform was developed by Affymetrix and its performance characteristics determined by UCLA clinical laboratory as required by the CLIA ‘88 regulations. The assay compared the patient’s DNA with 270 HapMap normal controls, using the genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism array 6.0. This array platform contains 1.8 million markers for copy number variant detection chosen at ~696 bp spacing throughout the human genome. Oligonucleotide probe information is based on the 36 build of the Human Genome (UCSC, University of California, Santa Cruz, Genome Browser, hg18, March 2006). Nondiagnostic copy number changes are referenced to the Database of Genomic Variants http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/.

Clinical Exome Sequencing:

Clinical exome sequencing was performed on the patient and his parents at UCLA following the validated protocol as described by Lee et al7. Briefly, exome capture was performed using Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon 50Mb XT kit and sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq2500 as 100-bp paired-end runs. Mean coverage across the RefSeq protein-coding exons and flanking intronic sequence (±2 bp) was 93x with > 92% of these base positions being sequenced at >9×. Sequence reads were aligned to the human reference genome (hg19/NCBI Build 37) using Novoalign V2.07.15b (Novocraft, http://www.novocraft.com/main/index.php). PCR duplicates were marked using Picard-tools-1.42 (http://picard.sourceforge.net/). Indel (insertions and deletions) realignment, quality score recalibration, variant calling, recalibration and variant evaluation were performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) v1.1–338. All variants were annotated using Variant Annotator eXtras (VAX)9 and deposited into MySQL 5.2 database for filtering. Amino acid altering de novo, hemizygous, homozygous, compound heterozygous and inherited heterozygous variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) less than 1% (based on data from the 1000 genomes project (1Kg), NHLBI exome sequencing project (ESP), NIEHS environmental genome project (EGP) and HapMap, without the distinction of ethnic background) that were relevant to the patient’s phenotype were considered for further analysis. The pathogenicity of a variant was determined according to current ACMG sequence interpretation guidelines.

Western Blot Analysis

Venous blood was drawn from the proband, both parents, and a confirmed unaffected control and immediately spun at 100g for 20 minutes for form platelet rich plasma (PRP). One milliliter of the PRP was transferred to a 1.5ml Eppendorf tube and spun at 100g for 20 minutes to pellet the white blood cells. The supernatant was transferred to a 1.5ml Eppendorf tube spun at maximum speed for 10 minutes to pellet platelets. The supernatant was aspirated from the platelet pellet and the pellet was suspended in 500ul of passive lysis buffer, prepared with phosphatase and protease inhibitors, and incubated by shaking at 4°C for one hour. After lysis tubes were spun at 7500 Rcf for 5 minutes to collect debris. Supernatant was transferred to a new tube then protein concentration determined with the Coomassie Plus Bradford (Life Technologies) reagent following manufacturer instructions. Protein samples were diluted to a final concentration of 5ug/20ul into Western loading buffer with beta-mercaptoethanol and then boiled for 5 minutes. Western blots were run on 12% acrylamide gels followed by transfer onto nitrocellulose membranes utilizing the Transblot Turbo® apparatus from Biorad. The membrane was blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin in TBST for 30 minutes, then incubated in primary antibodies overnight; Anti-Amyloid Precursor Protein (Sigma #A8717, Dilution 1/1000) and α-tubulin (Cell Signaling #2125, Dilution 1/1000). The next day blots were rinsed with Tris buffered saline (TBS) and washed three times with Tris buffered saline plus Tween (TBST). Blots were then incubated in rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at a dilution of 1/3750. Following secondary incubation membranes were rinsed with TBS then washed twice with TBST. Blots were exposed using Western Clarity reagents from BioRad and imaged on the Bio Rad ChemiDoc and viewed in ImageLab Software.

RESULTS

A 20-month-old male presented with microcephaly, hypotonia, and seizures. He was born prematurely at 33 weeks gestational age via spontaneous vaginal delivery to a G2P1 mother with a history of a previous miscarriage. Family history was significant for consanguinity on the maternal grandmother’s side of the family, seizures in a maternal uncle, and the demise of his paternal grandfather from hydrocephalus at age 40 (pedigree of family history, Figure 2). At birth, length was 45.7cm (75th %ile) and weight was 2381g (90th %ile). The perinatal period was complicated by poor feeding and seizures (first diagnosed at 1 month of age), which required hospitalization in the NICU until 2 months of age. Phenobarbital was initialed, which effectively controlled his seizures.

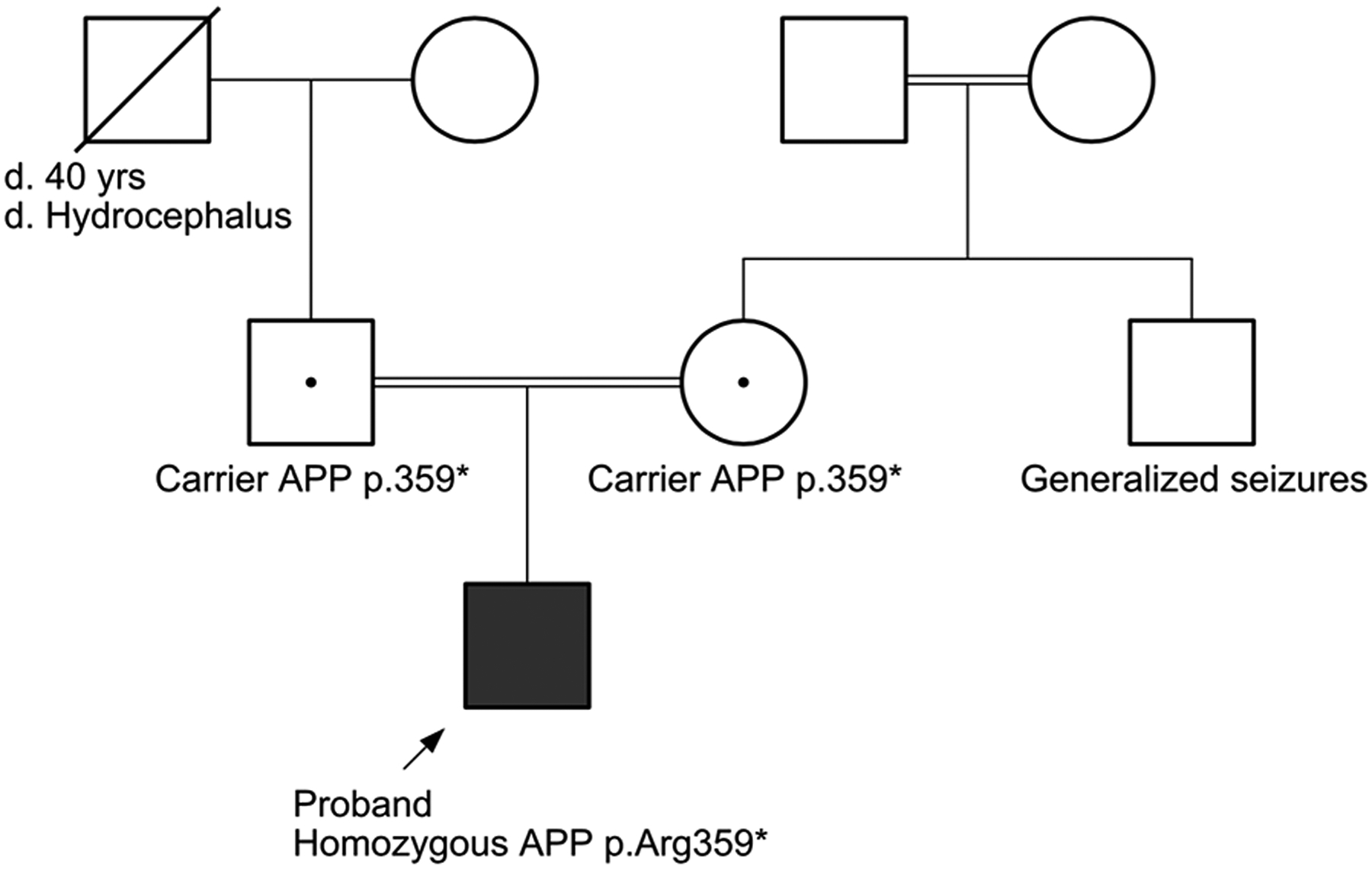

Figure 2: Pedigree for affected individual with homozygous truncating APP mutations.

Three generation family history was obtained. The pedigree demonstrates that carriers of the heterozygous truncating mutations in APP are unaffected. The proband is homozygous for the mutation and affected. Filled square indicates proband, black dot denotes carrier status of each parent. Double lines indicate consanguineous parentage.

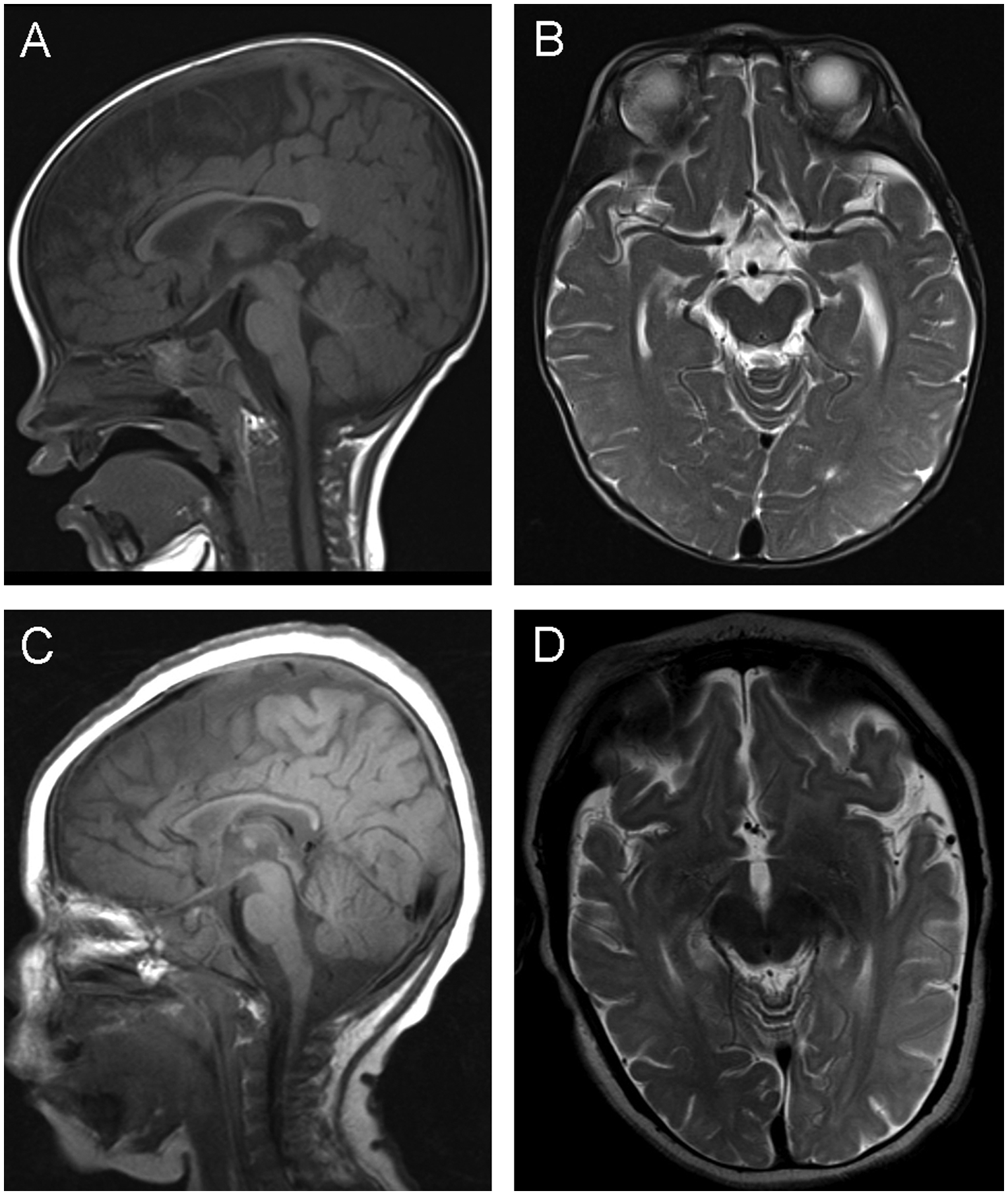

At 3 months of age, delay in developmental milestones was noted. Topiramate was added to the seizure regimen and was effective. Brain MRI at that time was significant for dolichocephaly, moderate diffuse cerebral atrophy, marked thinning of the corpus callosum, diffuse loss of white matter volume particularly within the bilateral parietal and occipital lobes, and a paucity of myelinated tracts within bilateral frontal lobes with no evidence of infarct, hemorrhage, or mass effect (Figure 1A–B).

Figure 1: Brain findings in APP knockout.

(A) One year old male normal sagittal T1 MRI demonstrating normal myelination and corpus callosum thickness and (B) axial T2 MRI demonstrating lack of focal atrophy and normal T2 signal in subcortical white matter of the left temporal and occipital regions. (C) Proband sagittal T1 MRI demonstrating diffuse hypomyelination with thin corpus callosum and (D) axial T2 MRI demonstrating focal atrophy and hyperintense T2 signal in subcortical white matter of the left temporal and occipital regions.

Seizure frequency ranged from 2–20 per day and the seizure semiology appeared to be complex partial with left or right head turning and eyes deviating up and to the left followed by tonic axial stiffening with left arm tonicity, clinically lasting no longer than 90 seconds. A 5-week-long video EEG recording while in status epilepticus demonstrated seizure clusters as frequently as 10 per hour with duration up to 25 minutes, with multifocal regions of epileptogenicity. In the postictal state, there was consolable crying, but no signs of fatigue or somnolence.

Additional medical history was significant for global developmental delay, microcephaly, and apneic episodes. Physical exam revealed height 71cm (<5th%ile), weight 9.5Kg (15%ile), head circumference 41.5cm (<5th %ile) at 13 months, as well as dolichocephaly, mild facial dysmorphia, hypotonia, slightly abnormal ear morphology and micrognathia. Eye movements were normal. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) chromosomal microarray analysis was performed to look for microdeletions and duplications associated with seizures and microcephaly, as well as regions of homozygosity that might suggest identity by descent and a recessive genetic etiology. Subsequently, clinical exome sequencing (CES) trio analysis was performed to identify mutations associated with the clinical findings.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) chromosomal microarray:

No copy number gains or losses of genomic regions of known clinical significance were observed. A total 138.36 Mb of contiguous stretches of homozygosity (each stretch larger than 5 Mb) were identified on chromosomes 3, 4, 5, 9, 13, 16, 20, and 21, suggesting identity by descent. No known uniparental disomy-associated human disorders or imprinted genes were located within these regions.

Clinical Exome Sequencing:

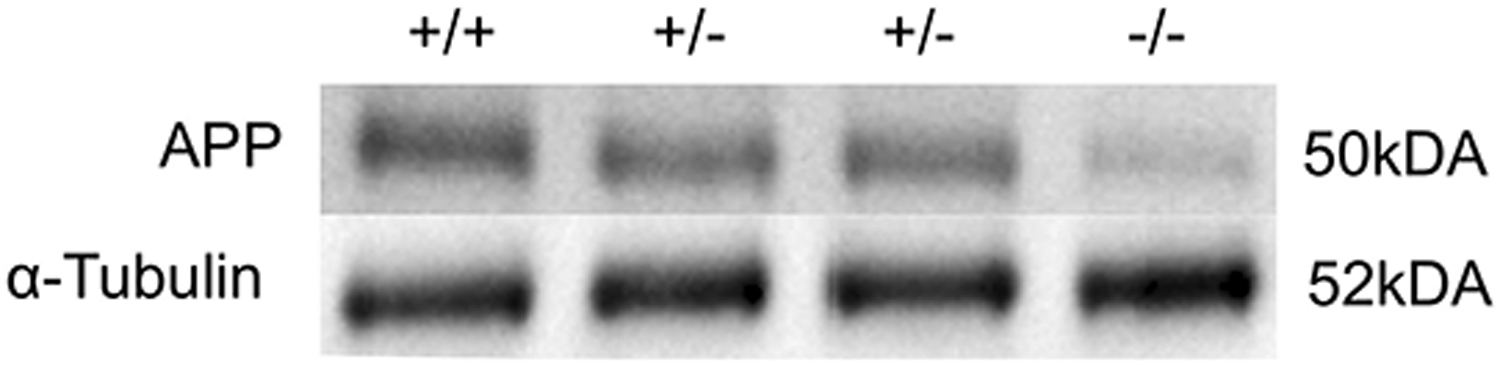

Of total 21,790 variants identified by CES, three variants were reported: two homozygous single nucleotide variants (SNV) in two genes, including a nonsense variant in APP gene and a missense variant in SETX gene and one heterozygous variant in CLN8 gene that is associated with an autosomal recessive neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-8 (table 1). We confirmed the pathogenicity of the APP genetic variants by analyzing protein extracts from platelets collected from the trio and a confirmed unaffected control. APP expression is decreased in both heterozygous parents and minimal in the proband when compared to control (Figure 3).

Table 1:

Variants identified and reported by clinical exome sequencing

| Gene | cDNA change | Protein change | Variant Classification | Zygosity | Allele counts in ExAC database | Disease Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SETX | NM_015046.5: c.4738C>T | p.Arg1580Cys | VUS | Homozygous | 1 heterozygous, 0 homozygous | Autosomal dominant juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 4 [MIM: 602433] Autosomal recessive ataxia-ocular apraxia-2 [606002]. |

| CLN8 | NM_018941.3: c.685C>G | p.Pro229Ala | VUS | Heterozygous (Maternally inherited) | 1397 heterozygous, 93 homozygous | Autosomal recessive neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-8 [MIM: 600143]. |

| APP | NM_000484.3: c.1075C>T | p.Arg359* | VUS | Homozygous | 7 heterozygous, 0 homozygous | Autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer disease-1 [MIM: 104300]. |

Figure 3: APP levels in carriers and affected proband.

Western blots comparing APP levels of unaffected control (+/+), parental carriers (+/−) and proband (−/−). The carriers are shown to have less APP than the control and the proband has minimal APP protein consistent with the genotypes (APP band shown has a MW of approximately 50kDa, α-tubulin band shown has a MW of approximately 52kDa).

DISCUSSION

In this study we report for the first time a loss of APP and its phenotypic consequences, including developmental delay, reduced growth, seizures, thin corpus callosum, and hypotonia. Additional variants were identified by CES including a homozygous recessive mutation in SETX a gene associated with juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 4 (ALS)10 and ataxia with ocular apraxia type 2 (AOA2)11, and a heterozygous variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis 8 (NCL)12. Comparisons of the clinical course of this case to the natural history of these other gene-associated syndromes revealed no clinical signs typically associated with juvenile ALS. However, definitive EMG testing was not performed and is needed to rule out ALS anterior horn involvement. Furthermore, ALS and AOA2 usually have onset in adolescence not the global, mutli-system involvement observed in this case. Lastly, NCL lysosomal enzyme testing was normal in this case, demonstrating that enzyme function was intact and furthermore, there are 93 individuals in ExAC (Exome Aggregation Consortium) database13 who are homozygous for the same variant the patient was identified with, making the variant likely benign.

We next evaluated the role that loss of APP function might be playing in causing the clinical phenotype by examining the consequence of APP knockout in the murine model. APP1 knockout mice have been generated alone and in combination with other APP gene orthologs14–20. The APP1 knockout mouse model has revealed a reproducible generalized phenotype including decreased growth5, decreased brain weight18, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum18, seizures19, defects in locomotor activity20, and impaired spatial learning associated with defects in long-term potentiation20. This case shares striking phenotypic overlap with the murine model including decreased growth, decreased brain weight, thinning of the corpus collosum, hypotonia and developmental delay (Summarized in Table 2).

Table 2:

Phenotypic overlap between human and murine APP knockouts

| Phenotype | Mouse | Human |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased growth | + | + |

| Decreased brain weight | + | + |

| Dysgenesis of the corpus callosum | + | + |

| Hypomyelination | na | + |

| Seizures | + | + |

| Defects in locomotor activity/hypotonia | + | + |

| Impaired spatial learning associated with defects in long-term potentiation | + | na |

| Developmental delay | na | + |

| Decreased Grip Strength | + | na |

| Increased Copper Levels | + | na |

| Defects in Lipid Metabolism | + | na |

| Dolichocephaly | − | + |

| Mild facial dysmorphia | − | + |

| Abnormal ear morphology | − | + |

| Micrognathia | − | + |

Present,

Absent,

not assessed

Loss of APP offers insight into the role of the non-pathogenic products of APP including but not limited to sAPPα. These findings suggest an essential role for intact APP processing in growth, brain development and behavior in both humans and mice. However, further studies are required to understand the exact contribution of APP to these processes. The data also demonstrate that APP haploinsufficiency is not associated with a phenotype as both unaffected parents are heterozygous for the nonsense allele and otherwise healthy. Additionally, searching the ExAC database revealed an absence of homozygote nonsense mutations in the healthy population. Interestingly, from this same analysis we were able to identify seven additional cases heterozygous for the same mutation as this case (hg19 chr21:g.[27369690C>T], c.1075C>T). These cases are all of Latino descent, as is the case of this family, indicating that this may be a founder mutation. This study expands the human phenotypic data associated with genetic changes in APP and further strengthens the utility of the mouse model to understand the role of the amyloid precursor protein. The identification of additional cases in combination with future functional studies will solidify the understanding of the exact role for APP in brain development.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the patient and the family for participating in the study. This work was supported by March of Dimes (grant #6-FY12-324, JAM-A), UCLA Children’s Discovery Institute, UCLA CART (NIH/NICHD Grant# P50-HD-055784, JAM-A), NIH/NCATS UCLA CTSI (Grant # UL1TR000124, JAM-A), Autism Speaks grant #9172 (SK) and the UCLA-Caltech MSTP NIH T32GM008042 (SK).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Campion D, Dumanchin C, Hannequin D, et al. Early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and mutation spectrum. Am J Hum Genet. 1999. September;65(3):664–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musiek ES, Holtzman DM. Three dimensions of the amyloid hypothesis: time, space and ‘wingmen’. Nat Neurosci. 2015. June;18(6):800–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller U, Cristina N, Li ZW, et al. Behavioral and anatomical deficits in mice homozygous for a modified beta-amyloid precursor protein gene. Cell. 1994. December 2;79(5):755–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow VW, Mattson MP, Wong PC, Gleichmann M. An overview of APP processing enzymes and products. Neuromolecular Med. 2010. March;12(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng H, Jiang M, Trumbauer ME, et al. beta-Amyloid precursor protein-deficient mice show reactive gliosis and decreased locomotor activity. Cell. 1995. May 19;81(4):525–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brickell KL, Steinbart EJ, Rumbaugh M, et al. Early-onset Alzheimer disease in families with late-onset Alzheimer disease: a potential important subtype of familial Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology. 2006. September;63(9):1307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H, Deignan JL, Dorrani N, et al. Clinical exome sequencing for genetic identification of rare Mendelian disorders. Jama. 2014. November 12;312(18):1880–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nature genetics. 2011. May;43(5):491-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yourshaw M, Taylor SP, Rao AR, Martin MG, Nelson SF. Rich annotation of DNA sequencing variants by leveraging the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor with plugins. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2014. March 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arning L, Epplen JT, Rahikkala E, Hendrich C, Ludolph AC, Sperfeld AD. The SETX missense variation spectrum as evaluated in patients with ALS4-like motor neuron diseases. Neurogenetics. 2013. February;14(1):53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anheim M, Monga B, Fleury M, et al. Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2: clinical, biological and genotype/phenotype correlation study of a cohort of 90 patients. Brain. 2009. October;132(Pt 10):2688–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kousi M, Lehesjoki AE, Mole SE. Update of the mutation spectrum and clinical correlations of over 360 mutations in eight genes that underlie the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Hum Mutat. 2012. January;33(1):42–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC). [cited 2015 September 1st]; Available from: http://exac.broadinstitute.org.

- 14.Li ZW, Stark G, Gotz J, et al. Generation of mice with a 200-kb amyloid precursor protein gene deletion by Cre recombinase-mediated site-specific recombination in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996. June 11;93(12):6158–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herms J, Anliker B, Heber S, et al. Cortical dysplasia resembling human type 2 lissencephaly in mice lacking all three APP family members. EMBO J. 2004. October 13;23(20):4106–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heber S, Herms J, Gajic V, et al. Mice with combined gene knock-outs reveal essential and partially redundant functions of amyloid precursor protein family members. J Neurosci. 2000. November 1;20(21):7951–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Koch CS, Zheng H, Chen H, et al. Generation of APLP2 KO mice and early postnatal lethality in APLP2/APP double KO mice. Neurobiol Aging. 1997. Nov-Dec;18(6):661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magara F, Muller U, Li ZW, et al. Genetic background changes the pattern of forebrain commissure defects in transgenic mice underexpressing the beta-amyloid-precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999. April 13;96(8):4656–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinbach JP, Muller U, Leist M, Li ZW, Nicotera P, Aguzzi A. Hypersensitivity to seizures in beta-amyloid precursor protein deficient mice. Cell Death Differ. 1998. October;5(10):858–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremml P, Lipp HP, Muller U, Ricceri L, Wolfer DP. Neurobehavioral development, adult openfield exploration and swimming navigation learning in mice with a modified beta-amyloid precursor protein gene. Behav Brain Res. 1998. September;95(1):65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]