Abstract

Background and study aims Endoscopic drainage of walled-off necrosis and subsequent endoscopic necrosectomy has been shown to be an effective step-up management strategy in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. One of the limitations of this endoscopic approach however, is the lack of dedicated and effective instruments to remove necrotic tissue. We aimed to evaluate the technical feasibility, safety, and clinical outcome of the EndoRotor, a novel automated mechanical endoscopic tissue resection tool, in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis.

Methods Patients with infected necrotizing pancreatitis in need of endoscopic necrosectomy after initial cystogastroscopy, were treated using the EndoRotor. Procedures were performed under conscious or propofol sedation by six experienced endoscopists. Technical feasibility, safety, and clinical outcomes were evaluated and scored. Operator experience was assessed by a short questionnaire.

Results Twelve patients with a median age of 60.6 years, underwent a total of 27 procedures for removal of infected pancreatic necrosis using the EndoRotor. Of these, nine patients were treated de novo. Three patients had already undergone unsuccessful endoscopic necrosectomy procedures using conventional tools. The mean size of the walled-off cavities was 117.5 ± 51.9 mm. An average of two procedures (range 1 – 7) per patient was required to achieve complete removal of necrotic tissue with the EndoRotor. No procedure-related adverse events occurred. Endoscopists deemed the device to be easy to use and effective for safe and controlled removal of the necrosis.

Conclusions Initial experience with the EndoRotor suggests that this device can safely, rapidly, and effectively remove necrotic tissue in patients with (infected) walled-off pancreatic necrosis.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is amongst the most frequent causes of gastrointestinal tract diseases that requires acute hospitalization and its incidence continues to rise 1 2 . Around 20 % of patients with acute pancreatitis develop necrotizing pancreatitis with about a third of them progressing to infected necrosis which is associated with mortality rates reported between 15 % and 30 % 3 4 5 . Since infected necrosis rarely responds to conservative treatment alone, virtually always some form of invasive and interventional treatment is necessary.

Over recent decades, the treatment of infected necrotizing pancreatitis has changed dramatically. Early open surgery is associated with a very high mortality rate and is largely avoided nowadays 6 . A shift towards less invasive techniques has become the standard of care. Minimally invasive techniques, either by percutaneous drainage, if necessary followed by video-assisted retroperitoneal drainage or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided transluminal drainage, if necessary followed by direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN), have been shown to improve outcomes for patients with regard to a combined endpoint consisting of mortality, multi-organ failure, external fistula, and endo- and exocrine insufficiency 5 7 8 . Several studies have reported on the potential and efficacy of direct endoscopic necrosectomy 9 10 .

If signs of infection persevere or worsen after EUS-guided transgastric or transduodenal drainage, the cyst cavity can be entered by a regular forward viewing endoscope to perform DEN. This can be achieved by balloon dilation of the transgastric fistula (up to 20 mm) when plastic double pigtail stents were placed initially, or directly through the stent opening when a large bore fully covered metal lumen apposing stent was placed. Usually, several sessions are required for complete removal of the necrosis; the mean number of DEN sessions varied from 1 to 15 in a meta-analysis by Puli et al. 11 with a weighted mean of 4.09 procedures.

One of the main limitations of endoscopic necrosectomy is the lack of dedicated and effective instruments to remove the necrotic tissue. For this purpose, various instruments, originally designed for other indications, are used. These devices, such as lithotripsy baskets, grasping forceps, retrieval nets, and polypectomy snares, are able to grasp and hold material but often lack sufficient grip making the procedure cumbersome, time consuming, and often marginally effective with only small chunks of necrosis being pulled into the gastrointestinal lumen per pass. Also, opening these devices in areas of necrosis is largely visually uncontrolled as is the amount of tissue that is caught. Pure suction can be helpful to pull out tissue chunks but often results in clogging of the working channel of the endoscope.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the technical feasibility, safety, and clinical outcome of the EndoRotor, a novel automated mechanical endoscopic resection system to suck, cut, and remove small pieces of tissue in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis.

Materials and methods

This prospective study took place at the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the Erasmus MC, University Medical Center in Rotterdam, a tertiary referral center in the Netherlands and at the Medizinische Klinik II, Sana Klinikum Offenbach in Offenbach, Germany. We recorded data on patient demographics, clinical presentation, etiologies of acute pancreatitis, American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) Physical Status Classification score 12 , radiologically defined size of the necrotic collection in a transverse computed axial tomographic image displaying the largest diameter of the necrotic cavity, procedural details, and adverse events during and after endoscopic necrosectomy. All patients with symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) were considered eligible for this study.

The EndoRotor

The EndoRotor (Interscope Medical, Inc., Worcester, MA, United States) is a novel automated mechanical endoscopic resection system designed for use in the gastrointestinal tract for tissue dissection and resection with a single device. The EndoRotor system can be advanced through the working channel of a therapeutic endoscope with a working channel of at least 3.2mm in diameter. The EndoRotor can be used to suck, cut, and remove small pieces of tissue through the catheter, consisting of a fixed outer cannula with a hollow inner cannula. A motorized, rotating, cutting tool driven by an electronically controlled console performs tissue resection and rotates at either 1000 or 1700 revolutions per minute. The catheter shaft is flexible and can tolerate endoscope bending of manipulation up to greater than 160 degrees. If greater manipulation is required, a longer catheter can be used to facilitate less torsional stress on the device. The necrotic tissue is sucked into the catheter using negative pressure and cut by the rotating blade from the inner cannula. Tissue is transported to a standard vacuum container. Both the cutting tool and suction are controlled by the endoscopist using two separate foot pedals. During this study the EndoRotor catheter was upgraded to potentially resect necrotic tissue more effectively. All procedures with both versions of the EndoRotor are reported in this study. The originally designed EndoRotor has a 3.0 mm 2 opening at the tip, in which the rotator blade is located, and teeth on the inner cutter. The novel design is adjusted to facilitate the resection of necrotic tissue; the tip has a 50 % wider opening of 4.4 mm 2 , the teeth on the inner cutter are smaller, and this design additionally has teeth on the outer cutter. No changes were made in the material or available rotation speed ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The EndoRotor.

Procedure

Procedures were performed as per protocol under conscious or propofol sedation with close monitoring by the anesthesia team and by six senior endoscopists with a broad experience in advanced endoscopic procedures. Initially, all patients underwent EUS-guided transgastric drainage, creating a fistula from the stomach to the adjacent WOPN. The choice of placement of one or more plastic stents or a lumen apposing metal stent (LAMS) was at the discretion of the endoscopist. In some patients, a nasocystic irrigation catheter was placed. In the absence of clinical improvement following initial endoscopic transgastric drainage, we proceeded to perform endoscopic necrosectomy. For this, a therapeutic gastroscope was advanced into the collection cavity, if necessary after balloon dilation to 18 or 20 mm with a controlled radial expansion (CRE) balloon. The EndoRotor was inserted through the working channel of a therapeutic endoscope and advanced into the collection cavity. Rotation speed of the EndoRotor catheter was recorded as well as changes in setting. Suction was set at between 500 and 620 mmHg, the maximum achievable negative pressure level.

Questionnaire

Endoscopists were asked to rate their experiences with the EndoRotor in a short questionnaire. Appreciation was expressed on a 10-point Likert scale 13 , varying from very negative appreciation (1) towards very positive appreciation (10). Questions were asked about the ease of use of the EndoRotor, handling of the device, the safety, and their appreciation on the additional value of the EndoRotor in the treatment of patients with pancreatic necrosis.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median, and range.

Results

Patient characteristics

Twelve patients with a mean age of 60.6 ± 11.4 years underwent endoscopic necrosectomy using the EndoRotor. Of these 12 patients, nine were male (75 %). Two patients (16.7 %) had a class IV score on the ASA physical status classification system. Four patients (33.3 %) scored ASA class III, five patients (41.7%) scored class II, and one patient (8.3 %) scored ASA class I. Nine patients were diagnosed with acute necrotizing pancreatitis, which had developed into infected WOPN. The time from the onset of acute complicated pancreatitis to necrosectomy was a median of 48 days (range 13 to 368). Three patients were initially drained because of mechanical complaints from large fluid collections. As a result of these procedures, the necrotic debris became infected necessitating necrosectomy. The mean necrotic collection size was 117.5 ± 51.9 mm. The etiology of the acute pancreatitis was biliary in four patients (33.3 %), alcoholic in three patients (25 %), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy in one patient (8.3 %), and in four patients (33.3 %), the etiology was unknown.

Transgastric endoscopic drainage was performed in all patients; eight patients (66.6 %) received two or three plastic stents, and four patients (33.3 %) received a LAMS to achieve transluminal drainage of necrotic debris. In all patients, an aspirate of the WOPN was obtained and sent for Gram staining and culture. Culture-proven infected necrosis was present in 10 out of 12 patients (83.3 %). The predominant microorganisms found were Streptococcus species.

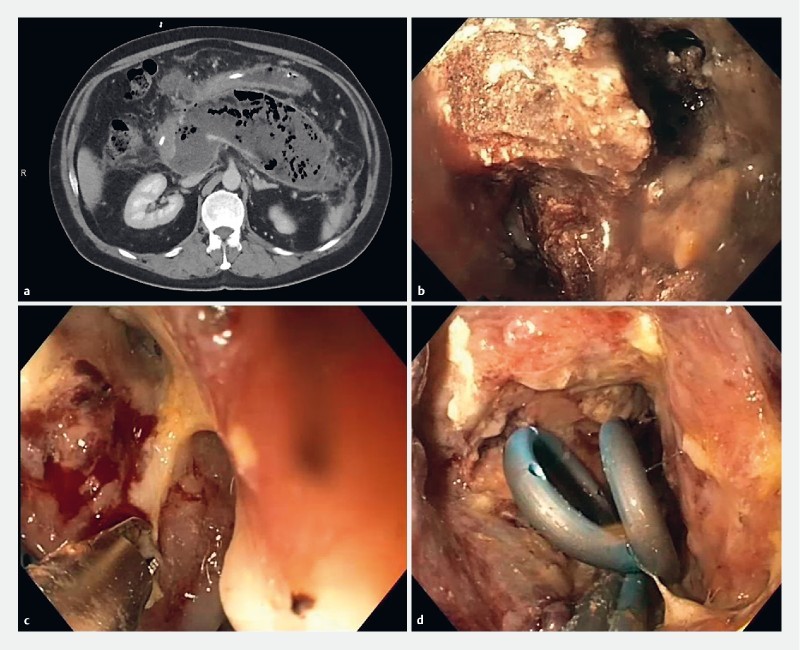

Three patients (25 %) were previously treated unsuccessfully with conventional instruments before being treated with the EndoRotor. Patient characteristics are included in Table 1 . Fig. 2 illustrates a typical case of infected WOPN and the steps during DEN.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Patient | Age, years | Sex | Etiology | Infected necrosis proven by culture | Size of the collection, mm | Stent placement | Previous necrosectomy 1 |

| 1 | 56 | Female | Biliary | Yes | 100 | 3 Pigtails | 2 |

| 2 | 65 | Male | Unknown | Yes | 167 | 2 Pigtails | 3 |

| 3 | 68 | Male | Unknown | Yes | 182 | LAMS | 1 |

| 4 | 43 | Male | Biliary | Yes | 141 | 2 Pigtails | 0 |

| 5 | 67 | Male | Biliary | Yes | 130 | 2 Pigtails | 0 |

| 6 | 71 | Male | Biliary | Yes | 78 | LAMS | 0 |

| 7 | 76 | Female | Alcoholic | Yes | 124 | 2 Pigtails | 0 |

| 8 | 58 | Male | Iatrogenic | No | 220 | 3 Pigtails | 0 |

| 9 | 51 | Male | Alcoholic | Yes | 84 | LAMS | 0 |

| 10 | 67 | Female | Unknown | Yes | 45 | LAMS | 0 |

| 11 | 66 | Male | Unknown | Unknown | 100 | 2 Pigtails | 0 |

| 12 | 39 | Male | Alcoholic | Yes | 90 | 1 Pigtail | 0 |

LAMS, lumen apposing metal stent.

Number of endoscopic necrosectomy procedures previously performed with conventional instruments.

Fig. 2.

Typical case of infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN). a Pre-intervention computed tomography scan illustrating WOPN with air bubbles. b Endoscopic view of necrosis after direct access into the cavity. c Necrosectomy using the EndoRotor. d Post-necrosectomy result.

Endoscopic procedure

In the 12 patients described, a total of 27 endoscopic necrosectomy procedures were performed using the EndoRotor to achieve complete removal of necrotic tissue. The median procedure time was 38 minutes (IQR 28.9). To achieve complete removal of pancreatic necrosis, the median number of procedures required was two per patient (range 1 to 7). The first version of the EndoRotor was used in 19 procedures, and the median procedure time was 45.8 minutes (IQR 28.1), with a median number of procedures required of 2.0 (range 1 to 7). The second version was used in eight procedures with a median procedure duration of 33 minutes (IQR 31.3); the median number of procedures required was 1.5 (range 1 to 3) to achieve complete removal of necrotic tissue.

Adverse events

No adverse events occurred during the necrosectomy procedures or within the next 24 hours. Three patients (27.2 %) experienced adverse events within the course of their infected pancreatic necrosis. One patient died eight days after the last endoscopic necrosectomy as a result of ongoing multi-organ failure caused by massive collections of infected pancreatic necrosis which, despite multiple sessions, could not be completely removed. One patient eventually died three months after discharge due to an underlying pancreatic carcinoma after having undergone two successful endoscopic necrosectomy procedures for infected necrotizing obstructive pancreatitis using the EndoRotor. In one patient, a gastrointestinal bleed occurred two days after the procedure necessitating coiling of the splenic artery. During the procedure, there was no evidence of bleeding or damage to any exposed vessel.

Questionnaire

Endoscopists rated the EndoRotor easy in its use (mean 10-point Likert scale score, 8.3; range, 8 to 9) and an effective tool to remove necrotic tissue (mean 10-point Likert scale score, 8.3; range, 8 to 9). They were especially satisfied by the ability to manage the removal of necrotic tissue in a controlled way (mean 10-point Likert scale score, 8.6; range, 8 to 9). The risk of causing complications was estimated to be low (mean 10-point Likert scale score, 1.9; range, 1 to 2). Overall, the device was judged to be of substantial additional value in the management of pancreatic necrosis (mean 10-point Likert scale score, 8.6; range, 8 to 9), and respondents were very willing to use the device in subsequent cases with necrotizing pancreatitis (mean 10-point Likert scale score, 9.3; range, 9 to 10).

Discussion

Direct endoscopic necrosectomy has proven to be safe and effective in the treatment of patients with infected pancreatic necrosis; however, up until now, no dedicated instruments were available for treating these patients. Recently, we published our preliminary experience with the EndoRotor 14 . This multicenter prospective cohort study describes the results in the first 12 patients with infected pancreatic necrosis who underwent a combined total of 27 DEN procedures using the EndoRotor. We have demonstrated the efficacy of the EndoRotor and good clinical outcomes, without any directly device-related adverse events.

For years, open necrosectomy has been considered as the gold standard treatment for management of pancreatic necrosis; however, it was accompanied by high morbidity and mortality rates 6 . In 2000, Carter et al. 15 demonstrated a new minimally invasive approach indicating that adequate necrosectomy can be achieved by either percutaneous or endoscopic techniques. These results encouraged several research groups to further investigate minimally invasive techniques, with the first randomized controlled trial published in 2010 by Van Santvoort et al. 5 confirming the benefit of a minimally invasive approach versus open necrosectomy in terms of major complications or death 6 15 16 17 . The potential and efficacy of endoscopic necrosectomy in terms of overall outcome is undisputed, but the proper tools available for adequate endoscopic debridement are still unavailable. Several alternatives have been described as additional treatment after initial endoscopic debridement to optimize clinical results, such as the use of a high-flow waterjet system 18 19 20 21 22 , the use of hydrogen peroxide 23 24 , and a vacuum-assisted closure system 25 26 27 . These techniques seem promising, but to date, only small case series have been published.

All 12 patients in this study underwent minimally invasive DEN using the EndoRotor. Of these 12 patients, three were treated after initial failure using conventional instruments. During the procedures, the rotation speed of the EndoRotor catheter was set at 1000 or 1700 revolutions per minute at the discretion of the treating endoscopist, with suction set at 620 mmHg negative pressure, the maximum achievable level. For optimal removal of tissue, the angle of the device relative to the necrotic tissue plane is important. The cutter opening should be directed to face the necrosis with direct contact. The high vacuum setting alone was not always able to suck in all of the tissue, and the best results were achieved by “trapping” the necrotic tissue between the cavity wall and the cutter opening of the catheter. This resulted in relatively fast and highly effective removal of necrotic tissue. There was no need for “blind” grabbing into the necrosis as is often unavoidable with snare-based instruments. We were able to clear the walls of the necrotic cavities of any necrosis left without damaging the wall itself. The tip of the EndoRotor cutter remains visible at all times making it a very safe procedure, and providing good control of what is being cut and what is not.

A median number of two procedures was required to achieve complete removal of necrotic tissue in this series. Several studies have reported on the mean number of interventions necessary to completely remove necrotic tissue using conventional instruments, with a weighted mean of four endoscopic necrosectomy procedures per patient 11 28 . Two large studies, published by Papachristou et al. 29 and Seifert et al., described a mean of four and even six procedures, respectively, with a maximum of 10 and even 35 endoscopic procedures. A more recently published study by Van Brunschot et al. 30 showed that 41 % of patients undergoing transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy required at least three procedures to achieve complete removal. Our study was not powered to detect a difference in the number of procedures compared to historical series or between the two technical iterations of the EndoRotor. Nevertheless, taking into consideration the large sizes of the necrotic collections in our series, the current data indicate that this device and, in particular, the adapted design of the EndoRotor, is even more effective to achieve complete clearance of the pancreatic necrosis in terms of the number of procedures required and the time spent.

Despite the reduction in overall mortality over recent years, acute necrotizing pancreatitis is still associated with high morbidity and mortality rates 3 4 5 . In patients treated endoscopically, a complication rate of 36 % was reported in a recently published meta-analysis, with bleeding as the most prevalent complication (22 %) 30 . In the current study, no device-related complications occurred during the procedures or within the first 24 hours. One patient died as a result of ongoing organ failure eight days after the last necrosectomy procedure; the necrotic cavity was very comprehensive and complete removal of necrotic tissue was therefore not achieved. Another patient died as a result of pancreatic carcinoma, which became apparent two months after successful endoscopic treatment of pancreatic necrosis using the EndoRotor, in the absence of complications. One patient suffered from a gastrointestinal bleed occurring two days after the necrosectomy and necessitating coiling of the splenic artery. During the necrosectomy, no bleeding or damage to any exposed vessel was observed. We believe that the bleeding was a direct result of ongoing inflammation within the remaining necrosis leading to pseudoaneurysm formation and eventually bleeding. Based on our experience, we believe that the risk of bleeding using this device is low, because removal of necrosis occurs in a very controlled way under direct endoscopic vision.

The general opinion of the endoscopists on the use of the EndoRotor for pancreatic necrosectomy was encouraging in the way that this novel tool was judged to be easy to use, effective, having a low risk of complications, and being of additional value in the treatment of patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. A limitation of the current study is the number of patients who were included. This was partly compensated by the fact that, in total, 27 necrosectomy procedures were carried out. This study was set up as a prospective cohort study testing initial feasibility and safety. These results should be confirmed by others and in comparative series.

The EndoRotor is the first instrument specifically designed to facilitate easy, safe, and rapid removal of necrotic tissue in patients with (infected) WOPN under direct endoscopic vision. Its unique design overcomes some of the inherent problems and shortcomings that are associated with conventional instruments currently used for endoscopic necrosectomy. Prospective comparative evaluation of the EndoRotor in a larger series of patients is required to confirm these favorable observations and to further evaluate its safety profile and clinical efficacy.

Footnotes

Competing interests Yes. Dr Van der Wiel has nothing to disclose. Dr May reports speakers and honorarium fee from ERBE Georgia USA, FALK, Fujifilm Global, MedUpdate, Promedics, Interscope and Olympus Medical. Dr Poley reports consultancy, travel and speakers fee from Cook Medical, Limerick, Ireland, Pentax and Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA. Dr Grubben has nothing to disclose. Dr Wetzka has nothing to disclose. Dr Bruno reports institutional study support by unrestricted grant from Cook Medical, Limerick, Ireland, Consultancy and Lecturer Fee from both Cook Medical Limerick, Ireland and Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA. Dr Koch reports personal fees from Cook Medical, Limerick, Ireland, personal fees from ERBE Georgia USA, personal fees from Pentax, personal fees from Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA, during the conduct of the study.

References

- 1.Spanier B, Bruno M J, Dijkgraaf M G. Incidence and mortality of acute and chronic pancreatitis in the Netherlands: a nationwide record-linked cohort study for the years 1995–2005. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3018–3026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rimbas M, Rizzati G, Gasbarrini A et al. Endoscopic necrosectomy through a lumen-apposing metal stent resulting in perforation: is it time to develop dedicated accessories? Endoscopy. 2018;50:79–80. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-119974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines . IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Santvoort H C, Bakker O J, Bollen T L et al. A conservative and minimally invasive approach to necrotizing pancreatitis improves outcome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1254–1263. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Santvoort H C, Besselink M G, Bakker O J et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. NEJM. 2010;362:1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor S, Alexakis N, Raraty M G et al. Early and late complications after pancreatic necrosectomy. Surgery. 2005;137:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakker O J, van Santvoort H C, van Brunschot S et al. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1053–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Brunschot S, van Grinsven J, Voermans R P et al. Transluminal endoscopic step-up approach versus minimally invasive surgical step-up approach in patients with infected necrotising pancreatitis (TENSION trial): design and rationale of a randomised controlled multicenter trial [ISRCTN09186711] BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bugiantella W, Rondelli F, Boni M et al. Necrotizing pancreatitis: A review of the interventions. Int J Surg. 2016;28 01:S163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurusamy K S, Belgaumkar A P, Haswell A et al. Interventions for necrotising pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD011383. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011383.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puli S R, Graumlich J F, Pamulaparthy S R et al. Endoscopic transmural necrosectomy for walled-off pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:50–53. doi: 10.1155/2014/539783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynes S R, Lawler P G. An assessment of the consistency of ASA physical status classification allocation. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:195–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb04554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 1932;140:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Wiel S E, Poley J W, Grubben M et al. The EndoRotor, a novel tool for the endoscopic management of pancreatic necrosis. Endoscopy. 2018;50:E240–241. doi: 10.1055/a-0628-6136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter C R, McKay C J, Imrie C W. Percutaneous necrosectomy and sinus tract endoscopy in the management of infected pancreatic necrosis: an initial experience. Ann Surg. 2000;232:175–180. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200008000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horvath K D, Kao L S, Wherry K L et al. A technique for laparoscopic-assisted percutaneous drainage of infected pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1221–1225. doi: 10.1007/s004640080166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Santvoort H C, Besselink M G, Bollen T L et al. Case-matched comparison of the retroperitoneal approach with laparotomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. World J Surg. 2007;31:1635–1642. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez J P, Mönkemüller C MWK. New technique to carry out endoscopic necrosectomy lavage using a pump. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:117. doi: 10.1111/den.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Consiglieri J BGCF, Busquets J, Salord S et al. Endoscopic necrosectomy of walled-off pancreatic necrosis using a lumen-apposing metal stent and irrigation technique. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2592–2602. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hritz I, Fejes R, Szekely A et al. Endoscopic transluminal pancreatic necrosectomy using a self-expanding metal stent and high-flow water-jet system. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3685–3692. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raczynski S, Teich N, Borte G et al. Percutaneous transgastric irrigation drainage in combination with endoscopic necrosectomy in necrotizing pancreatitis (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:420–424. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith I B, Gutierrez J P, Ramesh J et al. Endoscopic extra-cavitary drainage of pancreatic necrosis with fully covered self-expanding metal stents (fcSEMS) and staged lavage with a high-flow water jet system. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E154–160. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Othman M O, Elhanafi S, Saadi M et al. Extended cystogastrostomy with hydrogen peroxide irrigation facilitates endoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2017;2017:7.145803E6. doi: 10.1155/2017/7145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdelhafez M, Elnegouly M, Hasab Allah M S et al. Transluminal retroperitoneal endoscopic necrosectomy with the use of hydrogen peroxide and without external irrigation: a novel approach for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3911–3920. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2948-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wedemeyer J, Schneider A, Manns M P et al. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure of upper intestinal anastomotic leaks. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:708–711. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallstabe I, Tiedemann A, Schiefke I. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted therapy of an infected pancreatic pseudocyst. Endoscopy. 2011;43 02:E312–313. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallstabe I, Tiedemann A, Schiefke I. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted therapy of infected pancreatic pseudocyst using a coated sponge. Endoscopy. 2012;44 02:E49–50. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haghshenasskashani A, Laurence J M, Kwan V et al. Endoscopic necrosectomy of pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3724–3730. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papachristou G I, Takahashi N, Chahal P et al. Peroral endoscopic drainage/debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:943–951. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000254366.19366.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Brunschot S, van Grinsven J, van Santvoort H C et al. Endoscopic or surgical step-up approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;391:51–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]