Abstract

Rationale:

Polyglandular autoimmune syndromes (PAS) are a heterogeneous group of rare diseases characterized by the association of at least 2 organ-specific autoimmune disorders, concerning both the endocrine and nonendocrine organs. Type III is defined as the combination of autoimmune thyroid disease and other autoimmune conditions (other than Addison disease), and is divided into 4 subtypes. We describe a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis, adult-onset Still disease, alopecia, vasculitis, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis, and hyperparathyroidism. Co-occurrence of these 5 diseases allowed us to diagnose PAS type IIIc. The rare combination of these different diseases has not been reported before.

Patient concerns:

A 51-year-old woman was admitted in April, 2019 after the complaint of an enlarged thyroid. She was diagnosed with Hashimoto thyroiditis at the age of 36. At age 40, she was diagnosed with an adult-onset Still disease. Three months before admission, she experienced renal insufficiency. After admission, she was diagnosed with hyperparathyroidism.

Diagnosis:

Renal biopsy revealed renal vasculitis and crescentic nephritis. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody showed that human perinuclear ANCA and myeloperoxidase ANCA were positive. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with vasculitis and ANCA-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis. After admission, parathyroid single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography fusion image demonstrated the presence of hyperparathyroidism.

Interventions:

The patient was treated with high-dose methylprednisolone pulse therapy (0.1 g/d) for vasculitis and ANCA-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis, calcium and vitamin D3 (600 mg/d elemental calcium [calcium carbonate] and 2.5 μg/d active vitamin D3) for hyperparathyroidism, and levothyroxine sodium (50 ug/d) for Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Outcomes:

Up to now, serum thyroid-stimulating hormone, total triiodothyronine, total thyroxine, free triiodothyronine, and free thyroxine were within the normal ranges. Patient's renal function did not deteriorate.

Lessons:

We report a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis, adult-onset Still disease, alopecia, vasculitis, ANCA-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis, and hyperparathyroidism, which is a very rare combination. We present this case as evidence for the coexistence of several different immune-mediated diseases in the clinical context of a PAS IIIc.

Keywords: adult-onset Still disease, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody, autoimmune polyglandular syndromes, crescentic glomerulonephritis, Hashimoto disease

1. Introduction

As the incidence of autoimmune disease has gradually increased over the past 10 years, polyglandular autoimmune syndromes (PAS) should be paid significant attention by physicians. PAS are a group of autoimmune disorders characterized by endocrine tissue destruction causing multiple gland malfunction. The classification of PAS proposed in 1980 by Neufeld and Blizzard[1] based on clinical features included 4 main types of PAS: type I, type II, type III, and type IV. In PAS III, autoimmune thyroiditis occurs together with another organ-specific autoimmune disease. PAS III can be further divided into 3 subtypes: PAS IIIa, autoimmune thyroiditis with immune-mediated diabetes mellitus; PAS IIIb, autoimmune thyroiditis with pernicious anaemia; and PAS IIIc, autoimmune thyroiditis with vitiligo, alopecia, and/or other organ-specific autoimmune disease.[2] In this article, we present a rare case of patient affected by PAS IIIc (Hashimoto disease accompanied with vasculitis, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody [ANCA]-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis, adult-onset Still disease, and hyperparathyroidism).

2. Case report

A 51-year-old woman was admitted in April, 2019 after the complaint of an enlarged thyroid. Fifteen years before admission, during her annual physical examination, her titers of antithyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) and anti-thyroglobulin (anti-Tg) increased in the serum. Thyroid ultrasound revealed an enlarged thyroid gland with diffuse hypoechoic lesion. Her free thyroxine (FT4) slightly decreased, and her thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) increased. She was diagnosed with Hashimoto thyroiditis and treated with levothyroxine sodium (Na) (50 μg/d). After 3 years, she stopped taking levothyroxine Na. At age 40, she was diagnosed with adult-onset Still disease due to fever, rash, and arthralgia. She was treated with methylprednisolone for 18 days, and her condition sufficiently improved. Hence, she was discharged from the hospital.

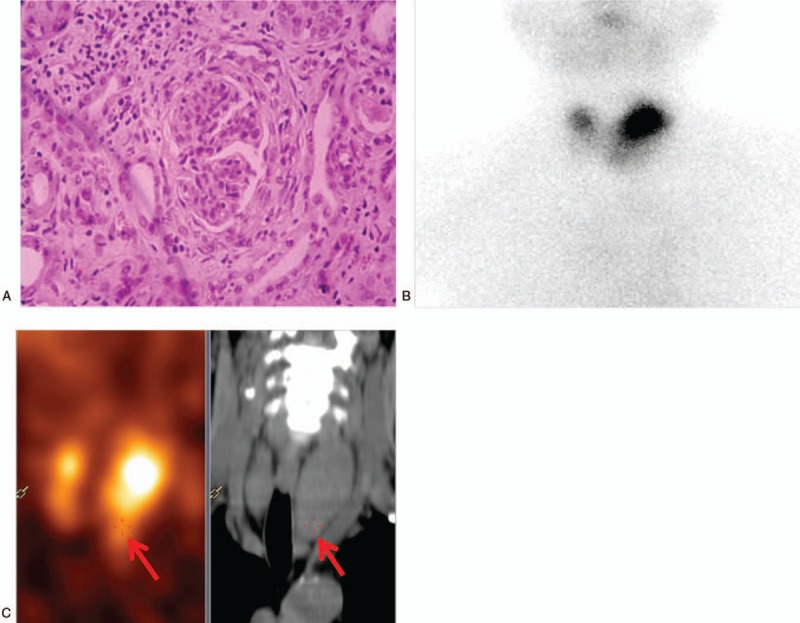

Three months before admission, she experienced alopecia and renal insufficiency (creatinine 265 μmol/L; glomerular filtration rate 22.03 mL/min). Considering her renal insufficiency, renal biopsy was performed. Light microscopy revealed renal vasculitis and crescentic nephritis (Fig. 1A). Serum antinuclear antibodies were positive (1:100). Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody showed that perinuclear ANCA and myeloperoxidase ANCA were positive. Therefore, vasculitis and ANCA-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis were considered. The patient was treated with high-dose methylprednisolone pulse therapy (0.1 g/d).

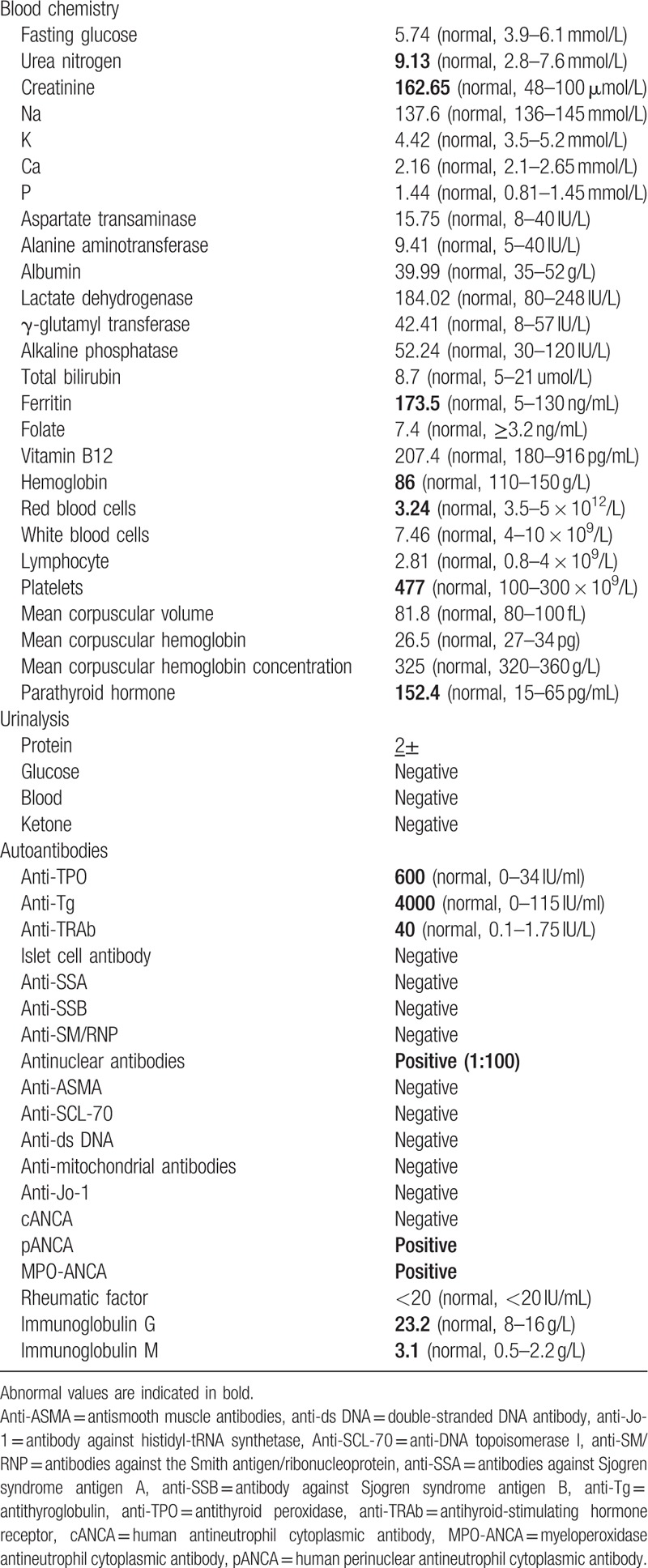

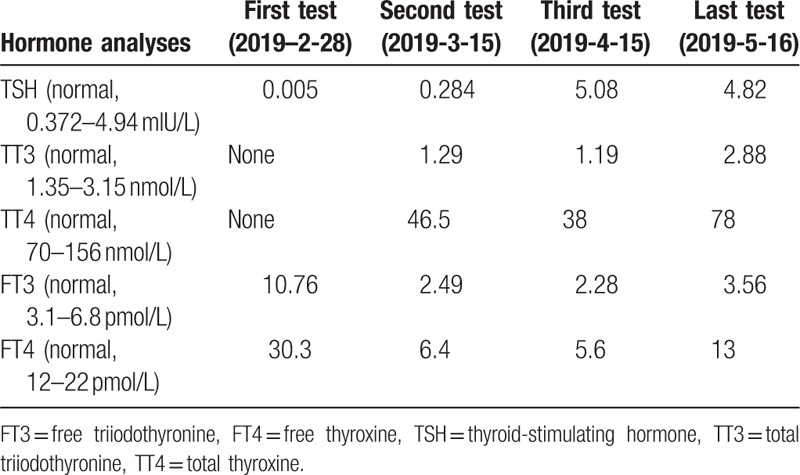

Figure 1.

(A) Renal biopsy (hematoxylin and eosin staining ×200) showing the interstitial and perivascular infiltrate comprising lymphocytes and eosinophils, fibrinoid necrosis, and glomerular, parietal epithelial cell hyperplasia. (B) 99Technetium scan revealing a high tracer uptake in the left upper thyroid. (C) Parathyroid single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography fusion image showing a slightly lower density below the left thyroid with a slightly higher concentration of radioactivity (as indicated by the red arrows).

Upon admission, her body mass index was 21 kg/m2, temperature 37.1°C, blood pressure 160/90 mm Hg, and pulse rate 90/min (regular). On physical examination, she presented with diffusely enlarged thyroid. There was slight exophthalmos. Laboratory data on admission were as follows (Table 1): urinalysis showed positive protein (2+), but no glucose, ketonuria, and blood. Blood analysis revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin 86 g/dL). Patient's renal function did not deteriorate. Fasting glucose, serum lipids, and electrolytes were within the normal ranges. The circadian rhythms of serum adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol, and renin were normal. Computed tomography scan of the adrenal glands and magnetic resonance imaging scan of the pituitary gland were normal. According to hormone analyses (2019-2-28), serum free triiodothyronine (FT3) (10.76 pmol/L) and FT4 (30.3 pmol/L) levels increased with a suppressed TSH level (0.005 mIU/mL) in the serum. Immunoglobulin G (23.2 g/L) and immunoglobulin M (3.1 g/L) increased. The titers of anti-TPO (600 IU/mL), anti-Tg (4000 IU/mL), and antithyrotropin receptor antibodies (40I U/L) increased. Thyroid ultrasound image showed diffusely enlarged thyroid gland without nodules, confirming the diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis. The radioactive iodine-131 uptake rate showed the following: 2 hours (radioactive iodine uptake rate, 7.16% [reference range 5%–15%]), 4 hours (radioactive iodine uptake rate, 11.34% [reference range 10%–20%]), and 24 hours (radioactive iodine uptake rate, 21.94% [reference range 20%–35%]). We suspected that it was a transient thyrotoxicosis, and the antithyroid therapy (methimazole) was not adapted. The results of thyroid hormone follow-up are shown in Table 2. Additionally, the serum parathyroid hormone (152.4 pg/mL) significantly increased. 99Technetium scan demonstrated a high tracer uptake in the left upper thyroid (Fig. 1B), which was associated with thyroid hyperplasia. Parathyroid single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography fusion image showed a slightly lower density below the left thyroid with a slightly higher concentration of radioactivity (Fig. 1C). Regarding bone mineral density, an osteoporosis was defined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (the T score of the patient was −3.17 standard deviation [SD] in the lumbar vertebra and −2.63 SD in the right articulatio coxae, lower than the reference value, which was −2.5 SD). Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with hyperparathyroidism and was treated with calcium and vitamin D3 (600 mg/d elemental calcium [calcium carbonate] and 2.5 μg/d active vitamin D3).

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission.

Table 2.

The results of thyroid hormone follow-up.

This study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Ethics Committee of the China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, and all the participants provided written informed consent for the publication of this case report.

3. Discussion

Considering the subtle manifestations of Hashimoto thyroiditis and its insufficient clinical features, the early detection of this disease is significantly hard. Hashimoto thyroiditis has a variety of clinical manifestations, which can be characterized by hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and a normal gland. In our case, hormone analyses on admission (2019-2-28) showed increased circulating FT3 (10.76 pmol/L) and FT4 (30.3 pmol/L) with a decreased TSH level (0.005 mIU/mL) in the serum. Hormone analysis after hospital discharge showed that TSH level gradually increased, and FT3, FT4, total triiodothyronine (TT3), and total thyroxine (TT4) gradually decreased. The third hormone analysis (2019-4-15) showed the low level of circulating TT3 and FT3 (TT3, 1.19 nmol/L; FT3, 2.28 pmol/L) and TT4 (TT4, 38 nmol/L; FT4, 5.6 pmol/L) with an increased TSH level (5.08 mIU/mL) in the serum. This was due to the release of thyroxine after thyroid follicle damage, rather than increased thyroxine synthesis; thyroxine levels will decrease over time. Subsequently, hyperthyroidism disappeared and even transitioned into hypothyroidism. In our case, the patient was finally diagnosed with hypothyroidism and received levothyroxine Na (50 μg/d). The last hormone analysis (2019-5-16) showed that the sera TSH, TT3, TT4, FT3, and FT4 were within the normal ranges. In the case of the presented patient, chronic kidney disease was due to hyperparathyroidism. Patients with chronic kidney disease are at risk of calcium and phosphorus metabolism disorders and osteoporosis. The parathyroid gland was stimulated by hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia for a long time, and it was easy to secrete a large amount of parathyroid hormone; subsequently, parathyroid hyperplasia was observed.

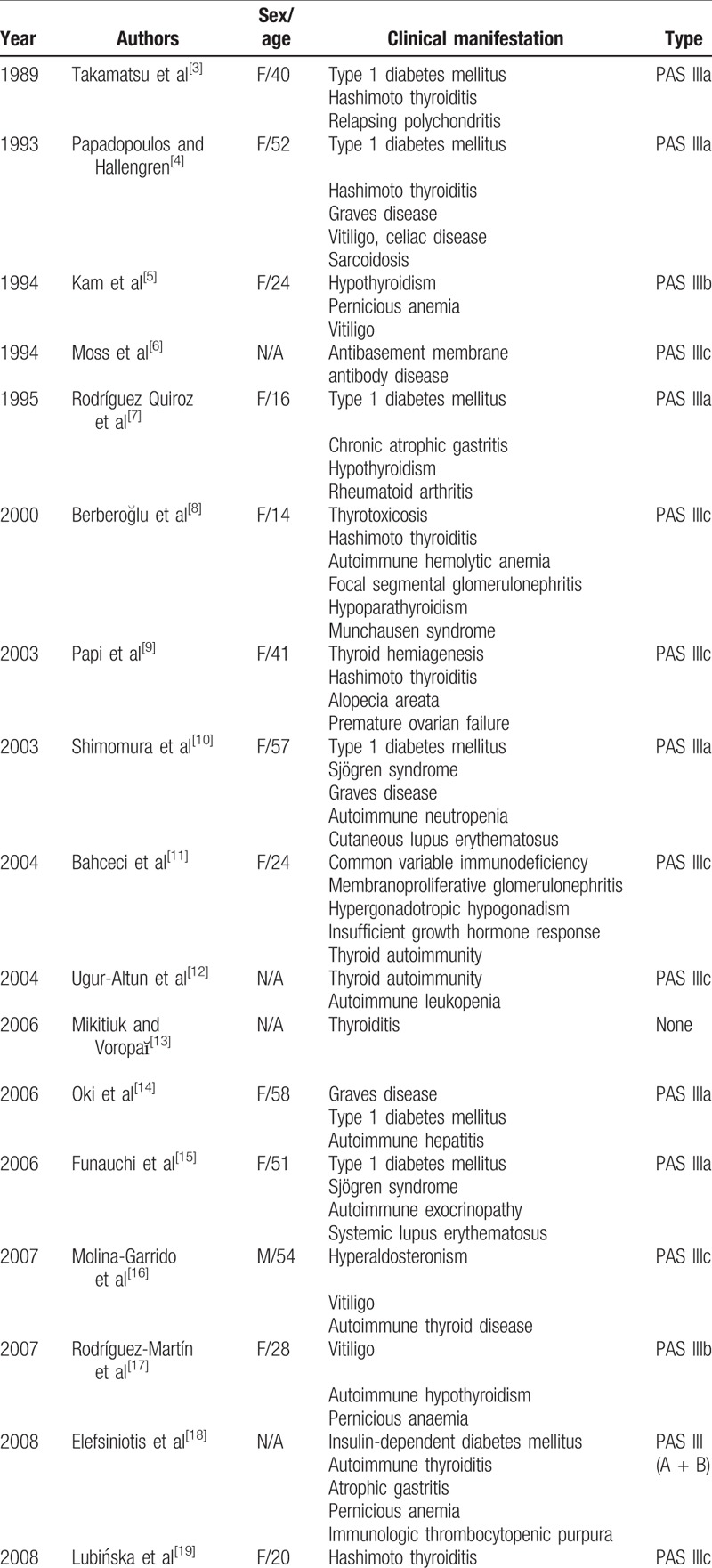

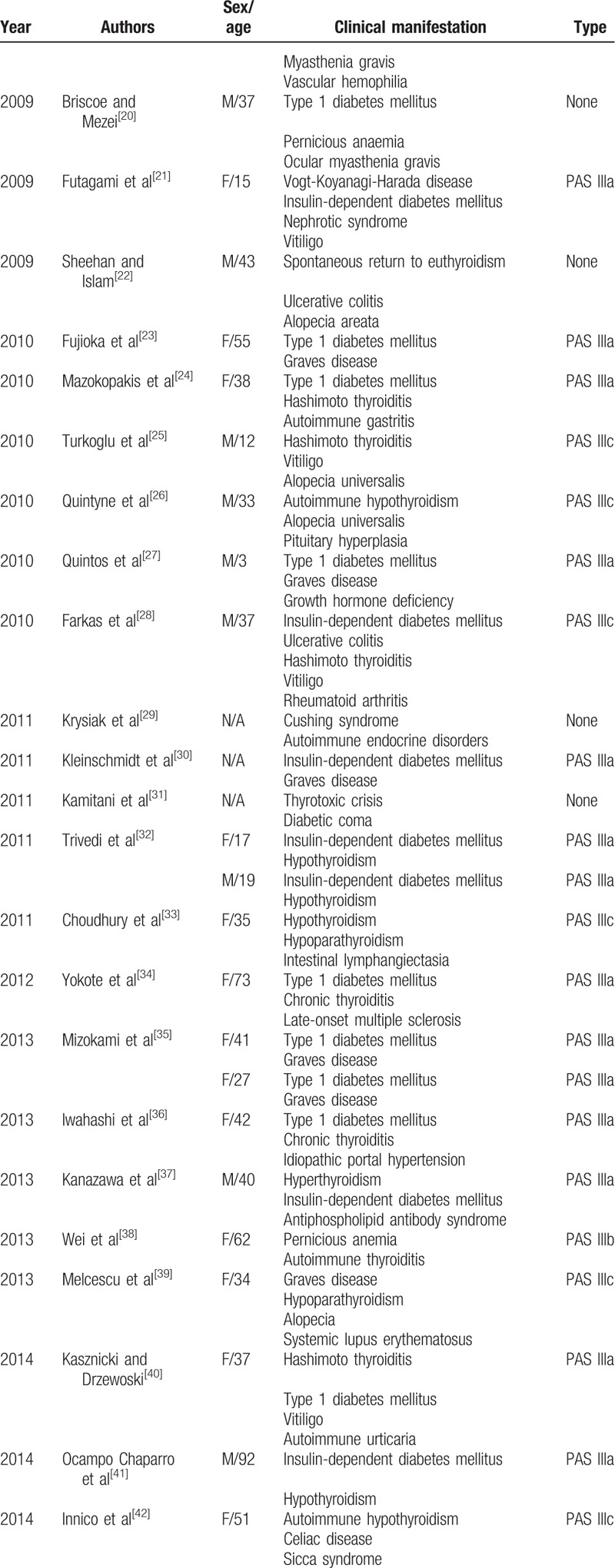

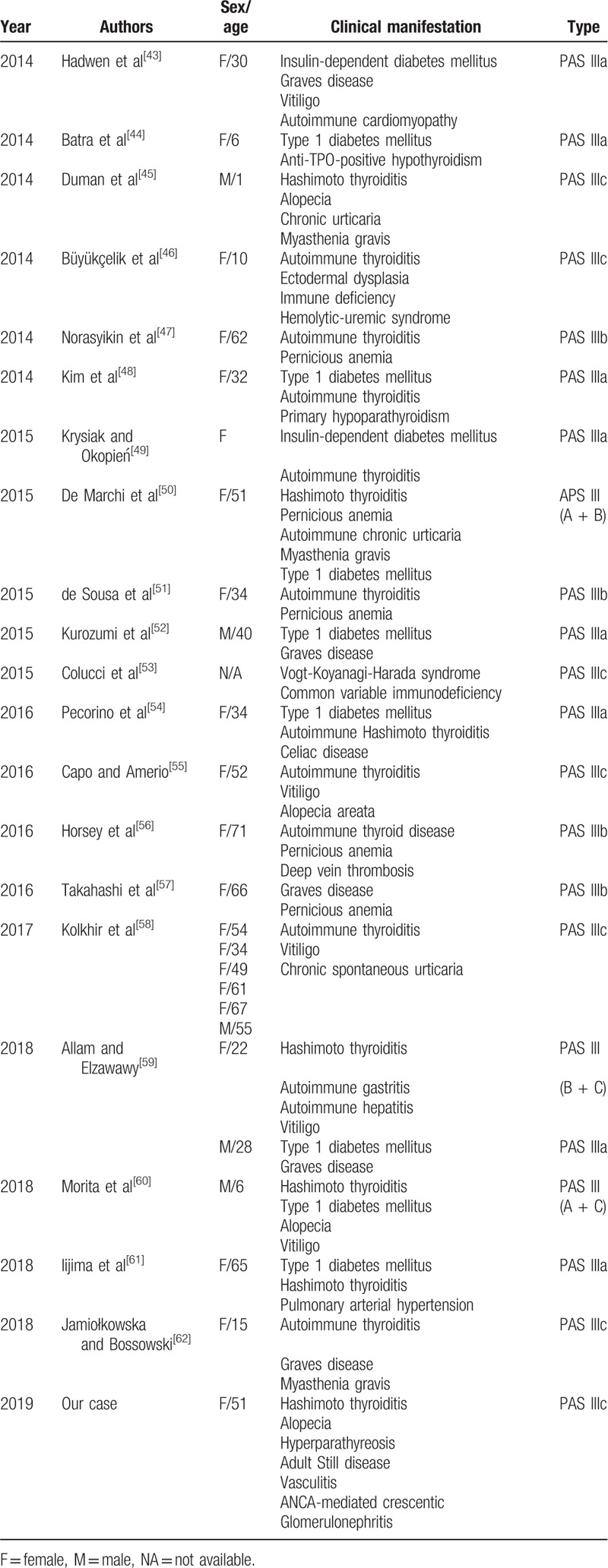

Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome is defined as multiple endocrine endorgan failure presenting over a variable period of time. Patients with PAS have an increased incidence of autoimmune diseases affecting both the endocrine and nonendocrine organs. The latter disorders include alopecia, vitiligo, pernicious anemia, Addison disease, insulin-dependent type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, myasthenia gravis, chronic active hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis. PAS III includes autoimmune thyroid disease plus another autoimmune disorder in the absence of Addison disease. If the other autoimmune disorder is insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, it is designated as type IIIa. Type IIIb involves pernicious anemia, whereas type IIIc includes vitiligo, alopecia, and/or other organ-specific autoimmune disease. Our patient had Hashimoto thyroiditis, alopecia, adult-onset Still disease, vasculitis, ANCA-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis, and hyperparathyroidism. Accordingly, she was classified as type IIIc. By reviewing the literature (Table 3 ), we confirm that this is a rare combination that has never been reported. Moss et al[6] described a patient with type IIIc PAS who presented with antibasement membrane antibody disease. They incorporated the antibasement membrane antibody disease into the spectrum of PAS. Shimomura et al[10] reported a case with PAS III associated with Sjögren syndrome and autoimmune neutropenia. They considered autoimmune disorders as the cause of this condition. In our case, multiple autoimmune disorders including autoimmune thyroiditis, adult-onset Still disease, and positive autoantibodies might be associated with the onset of vasculitis and ANCA-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis. At present, the mechanism of PAS is unclear, but its occurrence is associated with the genetic susceptibility associated with the human leukocyte antigen.[63] Tadmor et al[64] have hypothesized that organs derived from the same embryonal germ layer share common specific antigens. Recent studies have shown that polymorphisms of the T-cell regulatory gene (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4) are associated with PAS.[65] Evidently, the immunological mechanisms are crucial in the development of the autoimmune disease, and the intervention of activated self-reacting T cell is considered to be necessary in the majority of the cases to achieve complete destruction of the target organ.[66]

Table 3.

Summary of reported cases with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III.

Table 3 (Continued).

Summary of reported cases with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III.

Table 3 (Continued).

Summary of reported cases with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III.

Therapies regarding the different components of PAS III are similar whether they occur as single or in multiple associations with other autoimmune diseases. However, it is worth noting that Hashimoto disease can present as transient thyrotoxicosis; hence, antithyroid drugs and radiotherapy with iodine-131 must be carefully considered when treating Hashimoto disease. Additionally, the thyroid hormone replacement therapy in patients with autoimmune hypothyroidism may result in adrenal failure because thyroxine may enhance hepatic corticosteroid metabolism. Thus, before initiating the therapy with thyroxine, it is crucial to investigate the possible coexistence of an underlying adrenal insufficiency.[67]

4. Conclusions

We report a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis, adult-onset Still disease, alopecia, vasculitis, ANCA-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis, and hyperparathyroidism, which is a very rare combination. We present this case as evidence for the coexistence of several different immune-mediated diseases in the clinical context of a PAS IIIc.

Author contributions

Data curation: Shiyuan Tian.

Resources: Zhiwei Liu.

Supervision: Baofeng Xu.

Writing – original draft: Shiyuan Tian.

Writing – review & editing: Rui Liu.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: anti-Tg = antithyroglobulin, anti-TPO = antithyroid peroxidase, ANCA = antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, FT3 = free triiodothyronine, FT4 = free thyroxine, PAS = polyglandular autoimmune syndromes, TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone, TT3 = total triiodothyronine, TT4 = total thyroxine.

How to cite this article: Tian S, Xu B, Liu Z, Liu R. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis: A case report and literature review. Medicine. 2020;99:7(e19179).

S.T. and B.X. contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Neufeld M, Blizzard RM. Pinchera A, Doniach D, Fenzi GF, Baschieri L. Polyglandular autoimmune diseases. Symposium on Autoimmune Aspects of Endocrine Disorders. New York: Academic Press; 1980. 357–65. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Eisenbarth GS, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2068–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Takamatsu K, Nishiyama T, Nakauchi Y, et al. A case of insulin dependent diabetes mellitus associated with relapsing polychondritis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis and pituitary adrenocortical insufficiency in succession. Jpn J Med 1989;28:232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Papadopoulos KI, Hallengren B. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type III associated with coeliac disease and sarcoidosis. Postgrad Med J 1993;69:72–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kam T, Birmingham CL, Goldner EM. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome and anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 1994;16:101–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Moss M, Neff TA, Colby TV, et al. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage due to antibasement membrane antibody disease appearing with a polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. Chest 1994;105:296–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rodríguez Quiroz F, Berrón Pérez R, Ortega Martell JA, et al. Type III polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. Report of a case. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 1995;23:251–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Berberoğlu M, Ocal G, Cetinkaya E, et al. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome accompanied by Munchausen syndrome. Pediatr Int 2000;42:386–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Papi G, Salvatori R, Ferretti G, et al. Thyroid hemiagenesis and autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III. J Endocrinol Invest 2003;26:1160–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shimomura H, Nakase Y, Furuta H, et al. A rare case of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2003;61:103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bahceci M1, Tuzcu A, Pasa S, et al. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type III accompanied by common variable immunodeficiency. Gynecol Endocrinol 2004;19:47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ugur-Altun B, Arikan E, Guldiken S, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III in monozygotic twins: a case report. Acta Clin Belg 2004;59:225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mikitiuk MR, Voropaĭ TI. The case of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome of type III. Lik Sprava 2006;5:67–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Oki K, Yamane K, Koide J, et al. A case of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type III complicated with autoimmune hepatitis. Endocr J 2006;53:705–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Funauchi M, Tamaki C, Yamagata T, et al. A case of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III with a slowly progressive form of type-1 diabetes mellitus that manifested in the course of autoimmune diseases. Scand J Rheumatol 2006;35:81–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Molina-Garrido MJ, Enríquez R, Mora-Rufete A, et al. Primary hyperaldosteronism associated with vitiligo vulgaris and autoimmune hypothyroidism. Am J Med Sci 2007;333:178–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rodríguez-Martín M, Sáez-Rodríguez M, Carnerero-Rodríguez A, et al. Coincidental presentation of vitiligo and psoriasis in a patient with polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol 2007;32:453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Elefsiniotis IS, Papatsimpas G, Liatsos GD, et al. Atypical autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3 overlapped by chronic HCV infection resulting in carcinogenesis and fatal infection. South Med J 2008;10:756–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lubińska M, Swiatkowska-Stodulska R, Kazimierska E, et al. Acquired von Willebrand's disease in the course of severe primary hypothyroidism in a patient with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3. Endokrynol Pol 2008;59:34–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Briscoe NK, Mezei MM. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 3 in a patient with ocular myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2009;40:1064–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Futagami Y, Sugita S, Fujimaki T, et al. Bilateral anterior granulomatous keratouveitis with sunset glow fundus in a patient with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2009;17:88–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sheehan MT, Islam R. Silent thyroiditis, isolated corticotropin deficiency, and alopecia universalis in a patient with ulcerative colitis and elevated levels of plasma factor VIII: an unusual case of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3. Endocr Pract 2009;15:138–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fujioka T, Honda M, Yoshizaki T, et al. A case of type 1 diabetes onset and recurrence of Graves’ disease during pegylated interferon-( plus ribavirin treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Intern Med 2010;49:1987–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mazokopakis EE, Karefilakis CM, Batistakis AG, et al. High serum levels of calcitonin are not pathognomonic of medullary thyroid carcinoma and may indicate polyglandular autoimmune syndrome III. Hell J Nucl Med 2010;13:67–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Turkoglu Z, Kavala M, Kolcak O, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome-3C in a child. Dermatol Online J 2010;16:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Quintyne KI, Barratt N, O’Donoghue L, et al. Alopecia universalis, hypothyroidism and pituitary hyperplasia: polyglandular autoimmune syndrome III in a patient in remission from treated Hodgkin lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep 2010. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Quintos JB, Grover M, Boney CM, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3 and growth hormone deficiency. Pediatr Diabetes 2010;11:438–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Farkas K, Nagy F, Kovács L, et al. Ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis as part of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:10–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Krysiak R, Szkróbka W, Okopień B. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 3 in a patient after surgical treatment of Cushing syndrome. Wiad Lek 2011;64:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kleinschmidt K, Martoni A, Masetti R, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a child with acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;59:341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kamitani Y, Harada Y, Uchikura T, et al. Case report; autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type3 with thyrotoxic crisis and diabetic coma. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi 2011;100:1051–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Trivedi HL, Thakkar UG, Vanikar AV, et al. Treatment of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 3 using co-transplantation of insulin-secreting mesenchymal stem cells and haematopoietic stem cells. BMJ Case Rep 2011. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Choudhury BK, Saiki UK, Sarm D, et al. Intestinal lymphangiectasia in a patient with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III. J Assoc Physicians India 2011;59:729–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yokote H, Nagasawa M, Ichijo M, et al. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome-3 in a patient with late-onset multiple sclerosis. Neurologist 2012;18:83–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mizokami T, Yamauchi A, Sato Y, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of type 1 diabetes mellitus and Graves’ disease: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Intern Med 2013;52:2537–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Iwahashi A, Nakatani Y, Hirobata T, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome III in a patient with idiopathic portal hypertension. Intern Med 2013;52:1375–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kanazawa Y, Matsuo R, Fukushima Y, et al. Progression of right internal carotid artery stenosis in ischemic stroke patient with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome: a case report. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2013;53:531–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wei R, Chang A, Rockoff A. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome disguised as mental illness. BMJ Case Rep 2013. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Melcescu E, Kemp EH, Majithia V, et al. Graves’ disease, hypoparathyroidism, systemic lupus erythematosus, alopecia, and angioedema: autoimmune polyglandular syndrome variant or coincidence? Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2013;26:217–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kasznicki J, Drzewoski J. A case of autoimmune urticaria accompanying autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III associated with Hashimoto's disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and vitiligo. Endokrynol Pol 2014;65:320–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ocampo Chaparro JM, Reyes Ortiz CA, Ramírez M, et al. Type III polyglandular autoimmune syndrome: a case report. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2014;49:244–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Innico G, Frassetti N, Coppola B, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome in a woman of 51 years. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014;18:1717–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hadwen TI, Foster K, Buchanan J, et al. A case of nonischemic cardiomyopathy associated with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III. Endocr Pract 2014;20:183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Batra P, Singhal R, Shah D. Diabetic lipemia presenting as eruptive xanthomas in a child with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type IIIa. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2014;27:569–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Duman O, Koken R, Baran RT, et al. Infantile anti-MuSK positive myasthenia gravis in a patient with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy type 3. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2014;18:526–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Büyükçelik M, Keskin M, Keskin Ö, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3c with ectodermal dysplasia, immune deficiency and hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2014;6:47–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Norasyikin AW, Rozita M, Mohd Johan MJ, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome presenting with jaundice and thrombocytopenia. Med Princ Pract 2014;23:387–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kim SJ, Kim SY, Kim HB, et al. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type III with primary hypoparathyroidism. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2013;28:236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Krysiak R, Okopień B. Coexistence of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3 with diabetes insipidus. Wiad Lek 2015;68:204–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].De Marchi SU, Cecchin E, De Marchi S. Autoimmune spontaneous chronic urticaria and generalized myasthenia gravis in a patient with polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 3. Muscle Nerve 2015;52:440–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].de Sousa AWP, da Silva VM, Fernandes PA. Polyglandular syndrome type III and severe peripheral neuropathy: an unusual association. GE Port J Gastroenterol 2015;22:15–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kurozumi A, Okada Y, Arao T, et al. Induction of thyroid remission using rituximab in a patient with type 3 autoimmune polyglandular syndrome including Graves’ disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus: a case report. Endocr J 2015;62:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Colucci R, Galeone M, Conti R, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular type IIIc syndrome associated with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome and common variable immunodeficiency. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2015;150:633–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Pecorino B, Teodoro MC, Scollo P. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome in pregnancy: case report. Ital J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;28:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Capo A, Amerio P. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type III with a prevalence of cutaneous features. Clin Exp Dermatol 2017;42:61–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Horsey M, Hogan P, Oliver T. Deep vein thrombosis, an unreported first manifestation of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type III. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2016. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Takahashi T, Hara K, Takayoshi T, et al. Case Report; Gastric mucosa in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis. (Discussion about a case of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome 3B). Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi 2016;105:81–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kolkhir P, Pogorelov D, Kochergin N. Chronic spontaneous urticaria associated with vitiligo and thyroiditis (autoimmune polyglandular syndrome IIIC): case series. Int J Dermatol 2017;56:e89–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Allam MM, Elzawawy HTH. Induction of remission in autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type three (APS III): an old drug with new perspectives. Clin Case Rep 2018;6:2178–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Morita C, Yanase T, Shiohara T, et al. Aggressive treatment in paediatric or young patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DiHS)/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) is associated with future development of type III polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Iijima T, Niitani T, Tanaka S, et al. Concurrent variant type 3 autoimmune polyglandular syndrome and pulmonary arterial hypertension in a Japanese woman. Endocr J 2018;65:493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Jamiołkowska M, Bossowski A. 15-Year old girl with APS type IIIc, 12 months post-thymectomy remission of myasthenia. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2017;23:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Flesch BK, Matheis N, Alt T, et al. HLA class II haplotypes differentiate between the adult autoimmune polyglandular syndrome types II and III. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Tadmor B, Putterman C, Naparstek Y. Embryonal germ-layer antigens: target for autoimmunity. Lancet 1992;339:975–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Ueda H, Howson JM, Espositol L, et al. Association of the T-cell regulatory gene CTLA4 with susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Nature 2003;423:506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Roep BO. Autoreactive T cells in endocrine/organ-specific autoimmunity: why has progress been so slow? Springer Semin Immunopathol 2002;24:261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Schatz DA, Winter WE. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome II. Clinical syndrome and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 2002;31:339–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]