Abstract

Blood pressure (BP) is a leading global risk factor. Increasing age is related to changes in cardiovascular physiology that could influence cuff BP measurement, but this has never been examined systematically and was the aim of this study. Cuff BP was compared with invasive aortic BP across decades of age (from 40 to 89 years) using individual-level data from 31 studies (1674 patients undergoing coronary angiography) and 22 different cuff BP devices (19 oscillometric, 1 automated auscultation, 2 mercury sphygmomanometry) from the INvaSivE blood PressurE ConsorTium. Subjects were aged 64±11 years and 32% female. Cuff systolic BP (SBP) overestimated invasive aortic SBP in those aged 40-49 years, but with each older decade of age there was a progressive shift toward increasing underestimation of aortic SBP (p<0.0001). Conversely, cuff diastolic BP (DBP) overestimated invasive aortic DBP, and this progressively increased with increasing age (p<0.0001). Thus, there was a progressive increase in cuff pulse pressure (PP) underestimation of invasive aortic PP with increasing decades of age (p<0.0001). These age-related trends were observed across all categories of BP control. We conclude that cuff BP as an estimate of aortic BP was substantially influenced by increasing age, thus potentially exposing older people to greater chance for misdiagnosis of the true risk related to BP.

Keywords: sphygmomanometer, aging, blood pressure determination, pulse wave analysis

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide1 and the most important CVD risk factor is high blood pressure (BP). Clinical management of BP is based on measurements from upper arm cuff BP devices, either using auscultation or automated oscillometry. Correct identification and lowering of high BP will reduce the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality.2 However, our recent work revealed that cuff BP does not reflect intra-arterial BP either at the central aorta or brachial artery, especially in the systolic BP (SBP) range of 120 to 159 mmHg.3 The reasons for these differences are not fully understood, but are related to pathophysiological changes to the cardiovascular system that occur with increasing age or disease.4–7

Upper arm cuff BP measurement, whether by auscultation or oscillometry, relies on analysis of signals (Korotkoff sounds or cuff pressure oscillations) arising from the brachial artery.8 Major changes in cardiovascular hemodynamics could alter these signals to an extent that may affect cuff BP measurement. This could be highly relevant to increasing age because it is typically accompanied by a multitude of cardiovascular changes, such as lower BP amplification,6 impaired ventricular-vascular coupling,9 increased arterial stiffness,10 altered arterial geometry11 and abnormal blood flow dynamics.12, 13 The influence of age on cuff BP compared with an intra-arterial (invasive) BP reference standard has never been determined systematically, which was the aim of this study. We hypothesized that increasing age would be associated with greater differences between cuff BP and invasive aortic BP.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Overview

The analysis was conducted from data within an international consortium designed to better understand the level of cuff BP as an estimate of invasive BP (INvaSivE blood PressurE ConsorTium: INSPECT).3 This comprised an individual participant meta-analysis among 59 separate studies (total n=3073) where cuff measured BP was recorded simultaneously (or sequentially in the immediate time period) with invasive BP, thus providing a means to examine the difference between cuff BP compared with invasive BP. Studies that measured cuff BP in the angiography waiting room prior- or post- procedure were excluded. This current analysis focuses on the comparison of upper-arm cuff-measured BP versus invasive aortic BP as the reference measurement, which was measured using fluid-filled catheter-manometers or solid-state micromanometer catheters (complete data available for 1674 subjects). Rationale for comparison with aortic BP was because cuff BP aims to measure the pressure load at the arterial sites of interaction with the central organs.14, 15 Importantly, it is this central aortic BP that more strongly relates to organ damage, stroke and heart attack, compared with peripheral BP (i.e. brachial artery) which may substantially differ from central aortic BP, especially for SBP and pulse pressure (PP).3, 16 Although arm-cuff BP is not always expected to be equivalent to aortic BP, cuff SBP systematically underestimates the true (invasive) brachial SBP, and thus may approximate aortic SBP.3, 17 On the other hand, cuff diastolic BP (DBP) is expected to provide a reasonable estimate of the intra-arterial DBP because it is relatively constant through the arterial system.3 For complete assessment, a secondary (sensitivity) analysis was also undertaken to compare cuff BP with invasive brachial BP (complete data available for 520 subjects). The University of Tasmania Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (reference: H0015048).

Data handling

Several steps were taken to ensure the quality of the consortium data. First, only studies that measured cuff and invasive BPs simultaneously or within an immediate period (just before or after the invasive BP recording) were included. Full details on the sequence of cuff and invasive BP measurements are in the Expanded Methods in the online-only Data Supplement). Further, any study that recorded data during non-basal hemodynamic shifts or aimed to assess the effect of different cuff sizes on the relationship between cuff BP and invasive BP was excluded. A quality score was calculated by judging the key study methods that could have affected data accuracy (Online-only Data Supplement). Detailed systematic reviews for each topic were updated on 28 February 2018 using the same protocols previously published.3

Information on the separate studies included in the present analyses are detailed in Tables S1-S2 in the online-only Data Supplement. The analysis was conducted on subjects who were aged 40-89 years (stratified according to decades of age), because subjects aged younger than 40 or 90 years and older accounted for less than 4% of the data. Cuff BP was assessed by comparison to invasive BP, defined as cuff BP minus invasive BP. Therefore, a positive value for the difference indicated that cuff BP overestimated invasive BP, whereas a negative value indicated that cuff BP underestimated invasive BP. Cuff PP and invasive PP were calculated as SBP minus DBP. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated using a 40% form factor (DBP + 0.4*PP),18 because the true MAP, which is defined as the average of all points on the BP waveform, was not available.

Statistical analyses

Sample clinical characteristics were reported as mean±standard deviation (or median and interquartile range for skewed data) or number (%) of total cases. All differences between cuff BP and invasive BP were reported as mean and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Linear mixed models were used to analyse the influence of age on the difference between cuff BP and invasive BP. Multivariable mixed models were used to account for variables known or suspected to affect the relationship between age and the difference between cuff BP and invasive BP. These variables included sex (as a potential confounder) and separately invasive MAP, body mass index and heart rate (as potential mediators). A random effect term coding each individual study was included in the mixed models to account for the within study clustering of subjects. From the unadjusted and adjusted models, average marginal effects for the difference between cuff and invasive BP were calculated for each decade of age. The same analysis was performed with stratification by the category of cuff BP according to the 2017 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology arterial hypertension guidelines (normal: SBP <120 and DBP <80 mmHg; elevated: 120-129 and <80 mmHg; stage 1 hypertension: 130-139 or 80-89 mmHg and stage 2 hypertension: ≥140 or ≥90 mmHg).19 Sensitivity analyses included determining the influence of age on the difference between cuff BP and invasive BP when: 1) age was assessed as a continuous variable; 2) a fluid-filled or micromanometer tip catheter was used for invasive BP measurements; 3) studies were analysed according to a maximum versus non-maximum rated study quality score; 4) cuff versus invasive brachial BP was analysed, 5) cuff BP and invasive SBP and PP amplification (calculated as invasive brachial SBP and PP minus the respective invasive aortic values) were available on the same subjects, and; 6) the order of BP measurement was accounted for. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using R version 3.5.1 (R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.) The linear mixed models and average marginal effects were generated using the lme4 and ggeffects packages respectively.

Results

Subjects

1674 subjects from 31 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure S1). Twenty-two different cuff BP devices (19 oscillometric, 1 automated auscultation, 2 mercury sphygmomanometry) were used. In 16 of the studies, the average of multiple cuff BP readings was used in the analysis. Most subjects were patients who were undergoing coronary angiography procedures. The clinical characteristics in Table 1 are typical of this patient population; subjects were middle-to-older aged, predominately male, overweight according to body mass index and 67% had evidence of stenosis in at least one coronary artery. In total, 65% of subjects had cuff BP in the hypertensive range according to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines.

Table 1. Sample characteristics and blood pressure values across decades of age.

| Variable | 40 to 49 years (n=168) |

50 to 59 years (n=403) |

60 to 69 years (n=550) |

70 to 79 years (n=447) |

80 to 89 years (n=106) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 45.1±2.8 | 54.8±2.7 | 64.0 [62.0 to 67.0] | 74.0 [72.0 to 77.0] | 82 [81 to 84] |

| Female sex, %* | 45 (27) | 121 (30) | 178 (33) | 147 (33) | 40 (38) |

| Height, cm† | 170.7±9.6 | 167.1±9.1 | 165.4±10.3 | 162.9±10.2 | 158.9±10.1 |

| Weight, kg‡ | 84.4±20.9 | 78.3±18.6 | 73.7±17.6 | 68.1±14.5 | 61.1±13.0 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2§ | 28.9±5.9 | 27.9±5.8 | 26.8±5.5 | 25.4±4.4 | 24.1±4.1 |

| Heart rate, beats/min|| | 70±12 | 69±12 | 68±12 | 67±12 | 66±12 |

| Hypertension defined by cuff BP ≥ 130/≥80, % | 91 (54) | 241 (60) | 361 (66) | 316 (71) | 82 (77) |

| Hypertension defined by invasive aortic BP ≥130/≥80, % | 76 (45) | 206 (51) | 337 (61) | 305 (68) | 83 (78) |

| Blood pressure | |||||

| Cuff systolic blood pressure | 128±18 | 131±21 | 136±23 | 139±22 | 145±23 |

| Cuff diastolic blood pressure | 80±11 | 79±12 | 77±13 | 76±12 | 76±14 |

| Cuff pulse pressure | 48±13 | 52±15 | 59±18 | 63±20 | 69±20 |

| Invasive aortic systolic blood pressure | 125±20 | 130±25 | 138±25 | 143±26 | 150±26 |

| Invasive aortic diastolic blood pressure | 75±11 | 73±12 | 70±12 | 67±12 | 65±13 |

| Invasive aortic pulse pressure | 50±15 | 58±19 | 68±21 | 76±22 | 85±22 |

Data are mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. All blood pressure units are mm Hg.

n=1647

n=1520

n=1532

n=1518

n=1453.

Influence of age on upper-arm cuff BP measurement

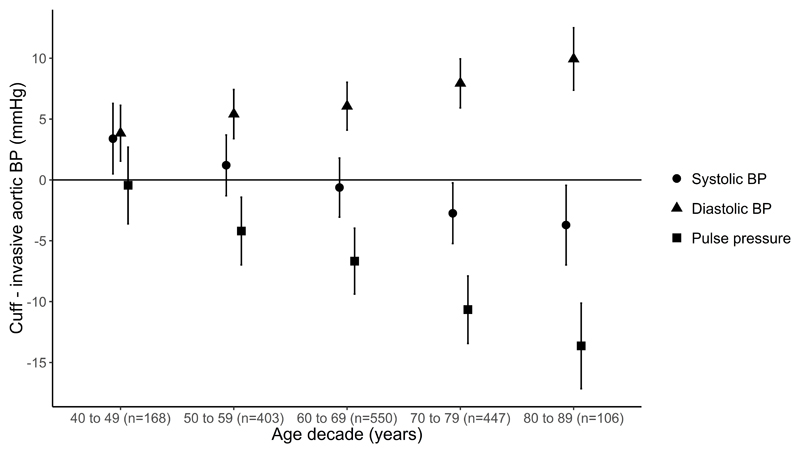

Systolic BP

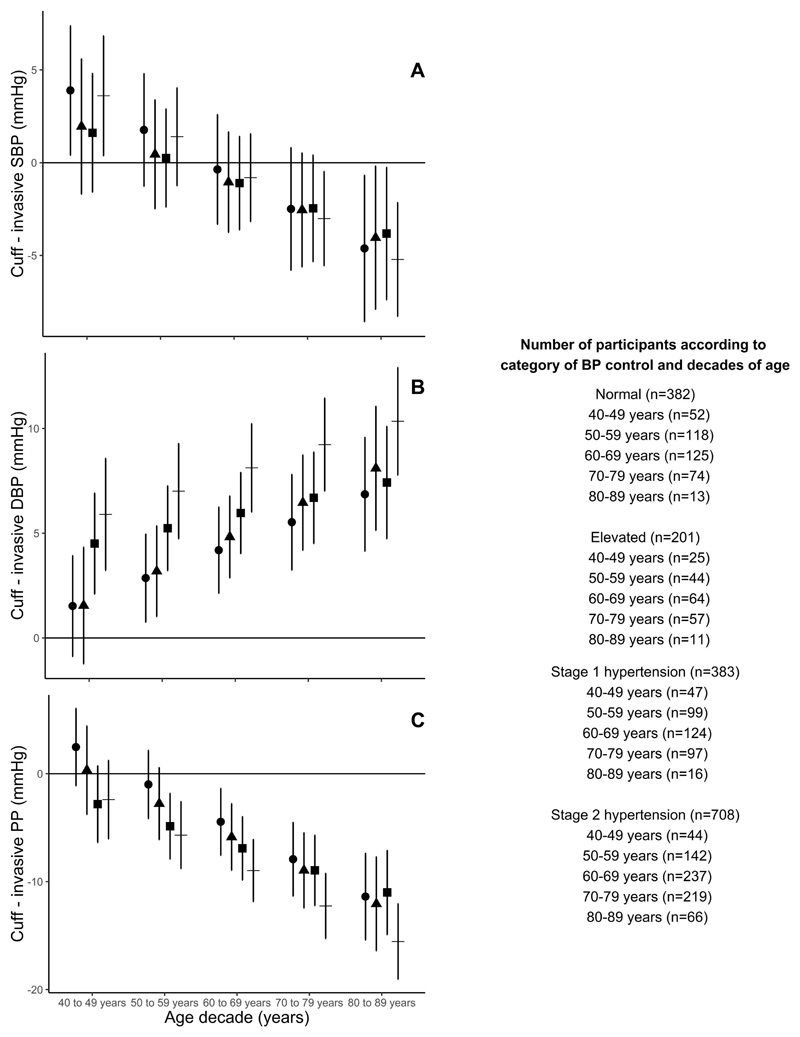

Cuff SBP slightly overestimated invasive aortic SBP in those aged 40-49 years, but with each increase in decade of age there was a progressive shift toward increasing underestimation of invasive aortic SBP (Figure 1 and Table S3, p<0.0001). In those aged 70-79 and 80-89 years, cuff SBP clearly underestimated invasive aortic SBP. After adjusting for sex and separately for invasive MAP, heart rate and body mass index, the difference between cuff SBP and invasive aortic SBP across the decades of age were slightly attenuated, but remained significant (Tables S4-S5, p<0.0001). Sex, invasive MAP, heart rate and body mass index (Tables S4-S5) were also related to the difference between cuff SBP and invasive aortic SBP. After stratification of subjects based on cuff BP guideline categories, each increase in decade of age remained related to a progressive increase in the magnitude of underestimation of invasive aortic SBP (Figure 2A, p<0.05 for each cuff BP category).

Figure 1.

Cuff blood pressure (BP) compared with invasive aortic systolic BP (red), diastolic BP (green) and pulse pressure (blue) measurements across age decades. Data are mean difference and 95% confidence interval (error bars). Data above the solid horizontal zero line indicates cuff BP is higher than invasive aortic BP and vice versa below the zero line. The trends for the age related differences in cuff BP compared with invasive aortic BP were statistically significant for systolic, diastolic and pulse pressure, p<0.0001 all.

Figure 2.

Cuff blood pressure (BP) compared with invasive aortic systolic BP (SBP; A), diastolic BP (DBP; B) and pulse pressure (PP; C) measurements across decades of age and stratified according to the category of BP control (according to the 2017 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology arterial hypertension guidelines).19 Data are mean difference and 95% confidence interval (error bars). Within each BP category, there were significant trends for the influence of age on cuff BP compared with invasive aortic BP (p<0.05), albeit borderline for DBP in stage 1 hypertension (p=0.086). Circles, normal BP; triangles, elevated BP; squares, stage 1 hypertension; crosses; stage 2 hypertension.

Diastolic BP

Cuff DBP overestimated invasive aortic DBP in all decades of age. Similar to SBP, with each increase in decade of age there was a progressive increase in the overestimation of aortic DBP (Figure 1 and Table S3, p<0.0001). The trend was unchanged after adjustment for the variables described above (Tables S4-S5, p<0.0001). Sex and invasive MAP (Tables S4-S5) were also related to the difference between cuff DBP and invasive aortic DBP in the adjusted models. After additional stratification of subjects based on the cuff BP category, each increase in decade of age remained related to a progressive increase in the magnitude of overestimation of invasive aortic DBP (p<0.01; Figure 2B), albeit stage 1 hypertension was a borderline trend (p=0.086).

Pulse pressure

For each increase in decade of age there was a progressive increase in the magnitude of underestimation of invasive aortic PP by cuff measurements (Figure 1 and Table S3, p<0.0001). The trend was unchanged after adjustment for sex or separately for invasive MAP, heart rate and body mass index, and all these variables were related to the difference between cuff PP and invasive aortic PP (Tables S4-S5, p<0.0001). After additional stratification of subjects based on the cuff BP category, each increase in decade of age remained related to a progressive increase in the magnitude of underestimation of invasive aortic PP (Figure 2C, p<0.001 for each BP category).

The unadjusted differences between cuff SBP, DBP and PP and invasive aortic SBP, DBP and PP were not different between the entire study dataset (n=1674) and the sub-populations used in the adjusted models for sex (n=1547) and invasive MAP, heart rate and body mass index (n=1382). Our previous work details the difference between cuff and invasive BP for each individual study.3

Sensitivity analyses

Age as a continuous variable

Increasing age was related to a progressive increase in the magnitude of underestimation of invasive aortic SBP and PP, and overestimation of aortic DBP (p<0.0001 all).

Fluid-filled or micromanometer tip catheter

The influence of age on cuff BP compared to invasive aortic BP was similar irrespective of the type of catheter used (trend p<0.0001 all; Figure S2).

Study quality score

The influence of age on cuff BP compared to invasive aortic BP was similar for the maximum and non-maximum rated studies (Figure S3).

Cuff BP compared with invasive brachial BP

520 subjects (62±11 years of age, 31% female; detailed characteristics in Table S6) met the inclusion criteria for this sensitivity analysis (Figure S4). Similar trends to aortic BP were observed for the influence of age on cuff SBP compared to invasive brachial (Figure S5 and Table S7), but this was less pronounced than for invasive aortic BP. After adjustment for sex and separately for invasive MAP, heart rate and body mass index the influence of age on cuff SBP compared to invasive brachial was not significant (Tables S8- S9). The influence of age on cuff DBP and PP compared to invasive brachial values was similar to the invasive aortic analysis (Figure S5 and Tables S8- S9). Stratification based on the cuff BP guideline category (Figure S6) was limited due to low subject numbers in several age and BP category combinations (e.g. n=3 for 80-89 years of age and normal, elevated or stage one hypertension BP categories). The magnitude of difference between cuff and invasive brachial BP was similar when data were stratified according to the type of catheter (Figure S7), and separately, the type of cuff device used (cuff oscillometry or mercury auscultation; Figure S8).

Cuff BP and BP amplification

In 372 subjects, the influence of age on cuff SBP compared to both invasive aortic and brachial SBP, tracks for the 40-49 and 50-59 age decades, but then SBP amplification does not continue to drop with increasing age (Figure S9). Cuff PP compared to both invasive aortic and brachial PP does not track with PP amplification. The influence of age on the difference between cuff and invasive aortic SBP, DBP or PP remained after adjustment for BP amplification (Table S10).

Order of BP measurement

The influence of age was not different whether cuff and invasive aortic BP were measured simultaneously, or if cuff BP was measured just prior to invasive BP or if invasive BP was measured just prior to cuff BP (Figure S10).

Discussion

Correct measurement of BP is paramount for the appropriate diagnosis and management of CVD risk.20 The key findings from this study were that there were greater differences between cuff BP and invasive aortic BP with increasing age, and that this occurred irrespective of the level of BP according to guideline categories. These findings could have implications for the assessment of true risk related to BP across the lifespan and may also be relevant to understanding the true distribution of aortic BP in population level studies, as well as clinical hypertension thresholds and validation protocols used to test new BP devices.

Pioneering studies in arterial physiology from the 1950s provided critical insights on BP measurement, showing that brachial SBP and PP were higher than corresponding aortic SBP and PP (termed BP amplification).21, 22 Inconsequential differences in DBP between the aorta and brachial artery were also reported. Theoretically, if cuff BP was a close proxy of invasive brachial BP then typically it should be higher than the corresponding invasive aortic SBP and PP and should agree closely with aortic DBP. However, cuff BP measurements systematically underestimate invasive brachial SBP (-5.7 mmHg) and PP (-12.0 mmHg) and systematically overestimate invasive brachial DBP (+5.5 mmHg).3 The systematic underestimation of brachial SBP means that cuff and invasive aortic SBP are not different on average, but there is wide variability with substantial over- or under-estimation of aortic SBP, depending on the individual and the cuff BP device.3 Invasive aortic DBP is systematically overestimated by cuff DBP. The present study extends on these findings and has found that age has a systematic influence on the cuff SBP, DBP and PP compared to invasive aortic values.

This study was not designed to determine the mechanisms which explain why chronological age influences the capacity of cuff BP to estimate invasive aortic BP. An excellent analogue of vascular aging can be derived from measures of arterial stiffness via methods such as pulse wave velocity, and several studies have examined the relationship between stiffness and cuff BP compared with invasive BP.4, 5, 23–25 In a study of elderly people, higher arterial stiffness was associated with overestimation of invasive aortic BP by auscultatory cuff measurements.5, 24 However, the opposite was observed among patients with chronic kidney disease,4 using oscillometric cuff BP methods. It is unclear whether differences in measurement methods or participant characteristics explain the discordance.26 Others have found no association between arterial stiffness and cuff compared with invasive BP.23, 25 Nevertheless, there is physiological rationale that is supportive of arterial stiffness causing differences between cuff BP and invasive aortic BP by altering blood flow dynamics and the properties of signals detected by the upper arm cuff.13 In previous studies a lower heart rate has also been associated with greater underestimation of SBP and overestimation of DBP, and this relationship may be influenced by the cuff deflation rate.27, 28 Our data is consistent with these observations, although in multivariable models the relationship between lower heart rate and cuff DBP overestimation was non-significant. Further, while older subjects did have lower heart rate, the influence of age on differences between cuff BP and invasive aortic BP remained similar after adjusting for heart rate.

Seminal epidemiologic data reporting population level characteristics and changes in BP with ageing have been recorded using cuff BP measurement methods.29, 30 These studies report a rise in SBP with increasing age and, that from approximately 50-60 years of age, PP also increases due to concomitant decreases in DBP.29, 31 Importantly, because these observations are from cuff BP, they may underestimate the relationship between aortic SBP and PP with age (according to our invasive observations). Similarly, the decline in invasive aortic DBP with increasing age after 50 years is also likely to be markedly more rapid than observed from cuff DBP measurements. These differences will influence the estimates of strength of association based on epidemiological studies, and are probable underlying contributors to clinical uncertainty and debate around treatment thresholds for SBP,19, 32, 33 DBP,34, 35 and PP.16, 32 Despite these issues, decades of evidence unequivocally support the value of cuff BP for prediction of cardiovascular risk in adults across the age spectrum examined in this study.2 Nevertheless, the impact of our findings on these uncertainties warrants closer examination in prospective studies.

The current findings may also be relevant to cuff BP device validation protocols that are used to test new devices by comparison to mercury sphygmomanometry. The current universal standard for the validation of BP devices does not take into consideration the potential influence of age on cuff measured BP.36 Our findings indicate that BP devices should be evaluated among a minimum number of subjects across different decades of age. However, this would not fully address the problem because the influence of age on the cuff BP is likely to extend to the reference comparator, mercury sphygmomanometry. Taken together this emphasises the urgent need to find better ways to measure BP (that reflect true invasive aortic BP) without confounding influences from age or other factors.

Subjects were studied under cardiac catheterisation conditions and had an indication for coronary angiography, thus the results may not reflect those that would be observed in the general population. Despite this, there is no data to suggest that the influence of age on cuff BP in patients undergoing cardiac catheterisation is different to other populations. Inter-arm cuff BP differences were not assessed systematically in each individual study, and we cannot rule out that some participants may have had obstructive arterial disease that could have influenced cuff BP compared to invasive aortic BP. Heart rate may also influence cuff BP measurement,27, 28 but in some studies included in this current analysis, heart rate may not have been recorded simultaneously to BP measurement. The influence of age on cuff BP compared to invasive aortic BP did not change when adjusted for heart rate. Reassuringly, the associations we observed between heart rate and the difference between cuff BP compared to invasive aortic BP are consistent with previous work.28 We could not separately compare the different types of cuff BP devices (e.g. mercury versus oscillometric) with invasive aortic BP due to a small sample of data recorded using mercury sphygmomanometry data (n=21). Oscillometric devices are designed to measure the same values as mercury sphygmomanometry, although age, pulse pressure and arterial stiffness can influence differences between these methods.26, 37 Nevertheless, we did not observe major differences between oscillometric devices or mercury sphygmomanometry compared to invasive brachial BP (Figure S8). The influence of age on cuff BP versus invasive aortic BP for prediction of clinical outcomes or management of hypertension could not be assessed in the present study. Addressing this question should be a research priority.

Perspectives

This study adds to growing evidence that there are substantive differences between cuff BP and invasive BP.3, 4, 6 Although cuff BP is the cornerstone for hypertension management, it is relatively crude and imprecise. In an era of rapid advances in technology and analytics, it is imperative that more personalized methods of BP measurement are developed. Ultimately, better measurement of BP should improve clinical care and lead to a reduction in preventable cardiovascular disease events.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and significance.

What Is New?

Cuff BP is influenced by increasing age, whereby invasive SBP and PP are progressively underestimated, but invasive DBP is progressively overestimated.

Age-related trends were independent of BP control and similar for comparisons of cuff BP and invasive brachial BP.

What Is Relevant?

The findings may have implications for BP management with increasing age, population level studies of BP, hypertension guideline thresholds and validation protocols that test new BP devices.

Summary

This study has shown that the difference between cuff BP and invasive aortic BP is substantially influenced by increasing age. Altogether, the data underline the need to improve the quality of BP measurement devices for people of all ages.

Acknowledgements

Additional members of the INvaSive blood PressurE ConsorTium are:

Ahmed M. Al-Jumaily: Institute of Biomedical Technologies, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

Brian A. Gould: BMI Hospital Blackheath, London, United Kingdom

Fuyou Liang: School of Naval Architecture, Ocean and Civil Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

Sandy Muecke: Department of Critical Care Medicine, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia

Ronak Rajani: Cardiology Department, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals, London, United Kingdom

Ralph Stewart: Green Lane Cardiovascular Service, Auckland City Hospital, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

George A. Stouffer: Division of Cardiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, United States

Manish D. Sinha: Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Department of Paediatric Nephrology, Kings College London, Evelina London Children’s Hospital, Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

Funding

This work was supported by a Vanguard Grant from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (reference 101836) and Royal Hobart Hospital Research Foundation project grant (reference 19-202).

Footnotes

Disclosures

James E Sharman: His university has received equipment and research funding from manufacturers of BP devices including AtCor Medical, IEM and Pulsecor (Uscom). He has no personal commercial interests related to BP companies. No disclosures from other authors.

References

- 1.Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, Ahmed M, Aksut B, Alam T, Alam K, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T, Emberson J, Chalmers J, Rodgers A, Rahimi K. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:957–967. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picone DS, Schultz MG, Otahal P, Aakhus S, Al-Jumaily AM, Black JA, Bos WJ, Chambers JB, Chen CH, Cheng HM, et al. Accuracy of cuff-measured blood pressure: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:572–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlsen RK, Peters CD, Khatir DS, Laugesen E, Botker HE, Winther S, Buus NH. Estimated aortic blood pressure based on radial artery tonometry underestimates directly measured aortic blood pressure in patients with advancing chronic kidney disease staging and increasing arterial stiffness. Kidney Int. 2016;90:869–877. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Messerli FH, Ventura HO, Amodeo C. Osler's maneuver and pseudohypertension. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1548–1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506133122405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picone DS, Schultz MG, Peng X, Black JA, Dwyer N, Roberts-Thomson P, Chen CH, Cheng HM, Pucci G, Wang JG, Sharman JE. Discovery of new blood pressure phenotypes and relation to accuracy of cuff devices used in daily clinical practice. Hypertension. 2018;71:1239–1247. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutouyrie P, London GM, Sharman JE. Estimating central blood pressure in the extreme vascular phenotype of advanced kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016;90:736–739. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benmira A, Perez-Martin A, Schuster I, Aichoun I, Coudray S, Bereksi-Reguig F, Dauzat M. From korotkoff and marey to automatic non-invasive oscillometric blood pressure measurement: Does easiness come with reliability? Expert Rev Med Devices. 2016;13:179–189. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2016.1128821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CH, Nakayama M, Nevo E, Fetics BJ, Maughan WL, Kass DA. Coupled systolic-ventricular and vascular stiffening with age: Implications for pressure regulation and cardiac reserve in the elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1221–1227. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness Collaboration. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: 'Establishing normal and reference values'. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2338–2350. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redheuil A, Yu WC, Mousseaux E, Harouni AA, Kachenoura N, Wu CO, Bluemke D, Lima JA. Age-related changes in aortic arch geometry: Relationship with proximal aortic function and left ventricular mass and remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1262–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bensalah MZ, Bollache E, Kachenoura N, Giron A, De Cesare A, Macron L, Lefort M, Redheuil A, Mousseaux E. Geometry is a major determinant of flow reversal in proximal aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306:H1408–1416. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00647.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashimoto J, Ito S. Aortic stiffness determines diastolic blood flow reversal in the descending thoracic aorta: Potential implication for retrograde embolic stroke in hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;62:542–549. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Booth J. A short history of blood pressure measurement. Proc R Soc Med. 1977;70:793–799. doi: 10.1177/003591577707001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karamanou M, Papaioannou TG, Tsoucalas G, Tousoulis D, Stefanadis C, Androutsos G. Blood pressure measurement: Lessons learned from our ancestors. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:700–704. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666141023163313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharman JE, Marwick TH. Accuracy of blood pressure monitoring devices: A critical need for improvement that could resolve discrepancy in hypertension guidelines. J Hum Hypertens. 2019;33:89–93. doi: 10.1038/s41371-018-0122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narayan O, Casan J, Szarski M, Dart AM, Meredith IT, Cameron JD. Estimation of central aortic blood pressure: A systematic meta-analysis of available techniques. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1727–1740. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bos WJ, Verrij E, Vincent HH, Westerhof BE, Parati G, van Montfrans GA. How to assess mean blood pressure properly at the brachial artery level. J Hypertens. 2007;25:751–755. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32803fb621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, et al. 2017 acc/aha/aapa/abc/acpm/ags/apha/ash/aspc/nma/pcna guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, Jones DW, Kurtz T, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: A statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the american heart association council on high blood pressure research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroeker EJ, Wood EH. Comparison of simultaneously recorded central and peripheral arterial pressure pulses during rest, exercise and tilted position in man. Circ Res. 1955;3:623–632. doi: 10.1161/01.res.3.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowell LB, Brengelmann GL, Blackmon JR, Bruce RA, Murray JA. Disparities between aortic and peripheral pulse pressures induced by upright exercise and vasomotor changes in man. Circulation. 1968;37:954–964. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.37.6.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuwajima I, Hoh E, Suzuki Y, Matsushita S, Kuramoto K. Pseudohypertension in the elderly. J Hypertens. 1990;8:429–432. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finnegan TP, Spence JD, Wong DG, Wells GA. Blood pressure measurement in the elderly: Correlation of arterial stiffness with difference between intra-arterial and cuff pressures. J Hypertens. 1985;3:231–235. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bos WJW, Van Goudoever J, Wesseling KH, Rongen GAPJM, Hoedemaker G, Lenders JWM, Van Montfrans GA. Pseudohypertension and the measurement of blood pressure. Hypertension. 1992;20:26–31. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.20.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Popele NM, Bos WJ, de Beer NA, van Der Kuip DA, Hofman A, Grobbee DE, Witteman JC. Arterial stiffness as underlying mechanism of disagreement between an oscillometric blood pressure monitor and a sphygmomanometer. Hypertension. 2000;36:484–488. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng DC, Amoore JN, Mieke S, Murray A. How important is the recommended slow cuff pressure deflation rate for blood pressure measurement? Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:2584–2591. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yong PG, Geddes LA. The effect of cuff pressure deflation rate on accuracy in indirect measurement of blood pressure with the auscultatory method. J Clin Monit. 1987;3:155–159. doi: 10.1007/BF01695937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franklin SS, Gustin Wt, Wong ND, Larson MG, Weber MA, Kannel WB, Levy D. Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure. The framingham heart study. Circulation. 1997;96:308–315. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S, Hense HW, Joffres M, Kastarinen M, Poulter N, Primatesta P, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 european countries, canada, and the united states. JAMA. 2003;289:2363–2369. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scuteri A, Morrell CH, Orru M, Strait JB, Tarasov KV, Ferreli LA, Loi F, Pilia MG, Delitala A, Spurgeon H, Najjar SS, et al. Longitudinal perspective on the conundrum of central arterial stiffness, blood pressure, and aging. Hypertension. 2014;64:1219–1227. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2018 esc/esh guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the european society of cardiology and the european society of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36:1953–2041. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messerli FH, Bangalore S. The blood pressure landscape: Schism among guidelines, confusion among physicians, and anxiety among patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1313–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mancia G, Grassi G. Aggressive blood pressure lowering is dangerous: The j-curve: Pro side of the arguement. Hypertension. 2014;63:29–36. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000441190.09494.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Mazzotta G, Garofoli M, Reboldi G. Aggressive blood pressure lowering is dangerous: The j-curve: Con side of the arguement. Hypertension. 2014;63:37–40. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000439102.43479.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stergiou GS, Palatini P, Asmar R, Ioannidis JP, Kollias A, Lacy P, McManus RJ, Myers MG, Parati G, Shennan A, Wang J, et al. Recommendations and practical guidance for performing and reporting validation studies according to the universal standard for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices by the association for the advancement of medical instrumentation/european society of hypertension/international organization for standardization (aami/esh/iso) J Hypertens. 2019;37:459–466. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stergiou GS, Lourida P, Tzamouranis D, Baibas NM. Unreliable oscillometric blood pressure measurement: Prevalence, repeatability and characteristics of the phenomenon. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:794–800. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2009.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.