Abstract

Objective

Older adults make up a rapidly increasing proportion of motor vehicle occupants and previous studies have demonstrated that this population is more susceptible to traumatic injuries. The CDC recommends that patients anticipated to have severe injuries (Injury Severity Score [ISS] ≥ 16) be transported to a trauma center. The recommended target rate for undertriage is ≤ 5% and for overtriage is ≤ 50%. Several regression-based algorithms for injury prediction have been developed in order to predict severe injury in occupants involved in a motor vehicle collision (MVC). The objective of this study to was to determine if the accuracy of regression-based injury severity prediction algorithms decreases for older adults.

Methods

Data was obtained from the National Automotive Sampling System – Crashworthiness Data System (NASS-CDS) from the years 2000–2015. Adult occupants involved in non-rollover MVCs were included. Regression-based injury risk models to predict severe injury (ISS ≥ 16) were developed using random split-samples with the following variables: age, delta-V, direction of impact, belt status, and number of impacts. Separate models were trained using data from the following age groups: 1) all adults, 2) 15–54 years, 3) ≥45 years, 4) ≥55 years, and 5) ≥65 years. The models were compared using the mean receiver operating characteristic area under curve (ROC-AUC) after 1,000 iterations of training and testing. The predicted rates of overtriage were then determined for each group in order to achieve a undertriage rate of 5%.

Results

There were 24,577 occupants (6,863,306 weighted) included in this analysis. The injury prediction model trained using data from all adults did not perform as well when tested on older adults (ROC-AUC: 15–54 years: 0.874 [95% CI: [0.851–0.895]; 45+ years: 0.837 [95% CI: 0.802–869]; 55+ years: 0.821 [95% CI: 0.775–0.864]; and 65+ years: 0.813 [95% CI: 0.754–0.866]). The accuracy of this model decreased in each decade of life. The performance did not change significantly when age-specific data was used to train the prediction models (ROC-AUC: 18–54 years: 0.874 [95% CI: 0.851–0.896]; 45+ years: 0.836 [95% CI: 0.798–0.871]; 55+ years: 0.822 [95% CI: 0.779–0.864]; and 65+ years: 0.808 [95% CI: 0.748–0.868]). In order to achieve an undertriage rate of 5%, the predicted overtriage rate by these models were 50% for occupants 15–54 years, 61% for occupants ≥ 55 years, 70% for occupants ≥ 55 years, and 71% for occupants ≥ 65 years.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that it is more difficult to accurately predict severe injury in older adults involved in MVCs, which has the potential to result in significant overtriage. This decreased accuracy is likely due to variations in fragility in older adults. These findings indicate that special care should be taken when using regression-based prediction models to determine the appropriate hospital destination for older occupants.

Keywords: Injury outcome, NASS-CDS, Older occupant, Injury prediction, Trauma Triage

INTRODUCTION

Older occupants make up an increasing proportion of motor vehicle collision (MVC) victims and the appropriate care of these patients is a significant public health challenge (Adams and Holcomb 2015; Fu et al. 2015). Unintentional injuries are an important cause of death in adults 65 years of age and older in the US, with MVCs being the second leading cause of death within this category (Heron 2017). Older occupants are also disproportionally affected by MVC trauma. Drivers over the age of 70 years have relatively low numbers of collisions per mile driven, yet they have the highest mortality rates per collision (Tefft 2017). Older occupants have been shown to be a rapidly increasing proportion of patients admitted for trauma and these numbers are projected to increase over time (Adams and Holcomb 2015; Fu et al. 2015). Many of the currently used clinical decision tools for the evaluation of trauma patients exclude patients above 60 or 65 years of age (Haydel et al. 2000; Hoffman et al. 2000; Jagoda et al. 2009; Stiell et al. 2003, 2005). The ability to properly evaluate and manage older adults after traumatic events will become increasingly important as the US population ages.

Appropriate prehospital triage of older adults with significant injuries to trauma centers is an important step in optimizing their care.Undertriage occurs when a patient with severe injuries is not transported to a trauma center, which can significantly increase mortality. It is estimated that mortality is reduced by 25% if patients with severe injuries are taken directly to a trauma center (MacKenzie et al. 2006). Overtriage occurs when a patient without significant injuries is incorrectly determined to require a trauma center (Rotondo 2014). This can result in increased burden on limited resources available at the trauma center. For the purposes of triage, severe injury is often considered to be an Injury Severity Score (ISS) ≥ 16 (Center for Disease Control 2008; Cox et al. 2012; Lossius et al. 2012; Rotondo 2014). The American College of Surgeons – Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT) recommends that undertriage rates should not exceed 5% (sensitivity 95%) and the overtriage rate should not exceed 50% (specificity of 50%) (Eastman 1994). Studies have shown that undertriage is common and increasing age is a significant risk factor (Barsi et al. 2016; Kodadek et al. 2015).

Advances in vehicle communication have made it possible for the automatic communication of crash data immediately after an MVC. As part of their triage guidelines, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) incorporated crash telemetry data into their trauma triage guidelines, recommending that patients with “vehicle telemetry data consistent with a high risk of injury” be transported to a trauma center (Sasser et al. 2012). The CDC has created a framework for automatically uploading this information, known as Advanced Automatic Crash Notification (AACN) (Center for Disease Control 2008). This crash data can be used to predict the risk of injury in occupants involved in a MVC (Augenstein et al. 2001, 2002; Hartka et al. 2018; Kononen et al. 2011; Stitzel et al. 2016; Weaver et al. 2015). The URGENCY algorithm, which predicts whether patients will have Maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale (MAIS) severity ≥3 injury, was the first widely-disseminated model demonstrating the ability to predict time-critical injuries based on crash data (Augenstein et al. 2001, 2002). Further research in this area has produced models that have demonstrated the ability to accurately predict injury severity, probability of injuries to body regions, and the probability of specific organ injuries (Kononen et al. 2011; Weaver et al. 2015; Stitzel et al. 2016; Hartka et al. 2018). Injury severity is usually determined by using the ISS, which is calculated by combining the square of three most severe injuries of different body regions. These models rely on regression-based techniques to correlate crash characteristics with injury risk. Age is often an important variable for determining injury severity in these models; however, the change in accuracy of these models due to an occupant’s age has not been explored.

It is therefore important to determine the ability of regression-based techniques to predict serious injury (ISS ≥ 16) in older occupants. The objective of this study was to quantify the change in accuracy of a regression-based automatic injury prediction model for older adults and examine the effect of this change on rates of appropriate triage.

METHODS

Data Source and Selection Criteria

The data were obtained from the National Automotive Sampling System-Crashworthiness Data System (NASS-CDS). NASS-CDS is a nationally representative sample of tow-away MVCs collected by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Data collected includes crash data, patient demographics, and occupant injuries coded using the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS)(Association for the Advancement of Automatic Medicine 2001). Crash data includes the direction of impact (Principal Direction of Force [PDOF]), change in velocity (delta-V), airbag deployment, number of impacts, type of vehicle, and rollover status. Occupant information includes occupant age, belt use, injury information, ejection status, mortality data, and location of medical treatment (if patient received medical attention).

NASS-CDS was queried for all cases from 2000–2015. Cases were only included if the occupant was an adult (≥15 years of age). Cases were excluded if basic crash information was missing (e.g. direction of impact, delta-V, seating position, and belt use), the occupant was not in a standard consumer vehicle, the occupant did not seek medical attention after the collision, or the crash resulted in a rollover of the occupant vehicle. Rollover crashes have inherently different prediction models which are largely driven by number of quarter turns and leading-edge vs trailing-edge. Traditional factors that are important for planar crashes may be less so in rollovers, therefore rollover crashes were excluded from this analysis.

AIS version 1990 update 1998 (AIS98) injury codes were used for this analysis (Association for the Advancement of Automatic Medicine 2001). NASS contains coding for injuries in AIS98 across all years studied, whereas only cases from the year 2010 and later additionally have AIS version 2005 update 2008 (AIS08) codes for injuries. AIS98 was selected in order to keep the AIS version consistent across all years.

Injury Risk Modeling and Testing

A split-sample approach was used for this study, with data randomly split into a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%). Logistic regression was used to develop models to predict the probability of occupants with a severe injury (ISS ≥ 16) based on occupant age, gender, delta-V, direction of impact, belt use, type of vehicle (car, SUV, van, pickup), and single or multiple impacts. The direction of impact was separated into quadrants based on the PDOF (frontal, rear, nearside, or farside). This modeling was performed using the R programming language.(R Core Team 2017) Each injury risk model was assessed for accuracy using the testing data set. The accuracy of detecting severe injury (ISS ≥ 16) was assessed using the Receiver Operating Characteristic-Area Under Curve (ROC-AUC).

The process of randomly splitting data, developing an injury risk model, and testing the model was repeated 1,000 times. The mean ROC-AUC was determined separately for each age range from these 1,000 iterations. A 95% confidence interval was determined by identifying the interval that contained 95% of the individual ROC-AUCs.

General Adult and Age Specific Injury Risk Models

General adult injury risk models were created using data from adults of all ages. The ROC-AUCs were calculated separately for the following groups of patients in the test data set: 1) all adults, 2) 15–54 years, 3) ≥ 45 years, 4) ≥ 55 years, and 5) ≥ 65 years. The age groups ≥ 45 years, ≥ 55 years, and ≥ 65 years were selected because it is unclear when the risk of significant injury increases for older adults (Boyd et al. 1987). The age threshold associated with an elevated risk of patient mortality can vary from approximately 45–65 years depending on the specific injuries sustained (Kuhne et al. 2005; Labib et al. 2011; Sampalis et al. 2009; Søreide et al. 2007; Stitzel et al. 2008, 2010).

The injury risk model for the general adult population was also tested on data across sequential age ranges in order to provide an indication of the trend in accuracy. The test data was separated into overlapping 20-year windows, which were 10 years below and 10 years above the target age. For example, the target age of 45 years included occupants 35–55 years of age. The accuracy of the model for each target age from 15–85 years was tested separately in this manner (e.g. 15, 16, 17,…84, 85 years). The windows were censored at the extremes of age due to available data (i.e. target age 20 years only included 15–30 years).

Additional injury risk models were then developed using training data only from occupants of ages 15–54 years, ≥ 45 years, ≥ 55 years, and ≥ 65 years. These models were then assessed using data from the corresponding age ranges in the test data sets. The purpose was to determine if injury risk models would have better performance if they were optimized for the age range being tested.

Triage Sensitivity and Specificity Analysis

The sensitivity and specificity of the general adult model was tested for its ability to correctly triage patients based on the predicted probability of severe injury (ISS ≥ 16). For this analysis, case weights provided by NHTSA were used to estimate the likelihood of correct triage recommendations in the US population. Each occupant was multiplied by the case weight in order to estimate the actual number of occupants who would have been correctly or incorrectly triaged at different threshold of the regression model. The thresholds were selected for each model which produced a sensitivity of 95%, which equates to an undertriage rate of 5% (1-sensitivity). The weighted specificities were determined based on these regression model thresholds. The specificities were determined for each age group (all adults, 15–54 years, ≥ 45 years,, ≥ 55 years, and ≥ 65 years). These specificities were used to determine the over triage rate (1-specificity).

RESULTS

The NASS-CDS query resulted in 24,577 cases (6,863,306 weighted cases) that met the criteria for the current study. Approximately 80% of occupants were aged 15–54 years; approximately 30%, 20%, and 10% occupants were aged ≥ 45 years, ≥ 55 years, and ≥ 65 years, respectively (Table 1). There were significant differences in demographics and crash characteristics among the groups due to shifts in driving profiles with increasing age. The proportion of females increased in the older age groups as did the proportion of occupants wearing seat belts. Most collisions involved a single impact with the occupant being in a passenger car across all ages. The majority of collisions were frontal impacts, although older adults had a greater proportion of side impacts.

Table 1 –

Demographics of adult occupants involved in an MVC from the NASS-CDS database years 2000–2015 included for analysis.

| 15–54 | 45+ | 55+ | 65+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | |

| Total Patients | 13,711 (80.0%) | 4,104,875 (82.9%) | 5621 (32.8%) | 1,480,342 (29.9%) | 3,426 (20.0%) | 847,841 (17.1%) | 1,819 (10.6%) | 430,248 (8.7%) |

| ISS 16+ | 888 (6.5%) | 51,075 (1.2%) | 569 (10.1%) | 45,273 (3.1%) | 419 (12.2%) | 35,939 (4.2%) | 255 (14.0%) | 21,388 (5.0%) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 6,832 (49.8%) | 2,076,733 (50.6%) | 2,563 (45.6%) | 695,983 (47.0%) | 1,554 (45.4%) | 385,087 (45.4%) | 838 (46.1%) | 200,789 (46.7%) |

| Female | 6,879 (50.2%) | 2,028,142 (49.4%) | 3,058 (54.4%) | 784,359 (53.0%) | 1,872 (54.6%) | 462,754 (54.6%) | 981 (53.9%) | 229,459 (53.3%) |

| Single collision | ||||||||

| Yes | 8,664 (63.2%) | 2,875,587 (70.1%) | 3,642 (64.8%) | 1,052,235 (71.1%) | 2,202 (64.3%) | 600,338 (70.8%) | 1,145 (62.9%) | 309,096 (71.8%) |

| No | 5,047 (36.8%) | 1,229,288 (29.9%) | 1,979 (35.2%) | 428,107 (28.9%) | 1,224 (35.7%) | 247,502 (29.2%) | 674 (37.1%) | 121,153 (28.2%) |

| PDOF | ||||||||

| Front | 10,795 (79.7%) | 3,351,788 (81.7%) | 4,285 (76.2%) | 1,171,220 (79.1%) | 2,558 (74.7%) | 641,601 (75.7%) | 1,342 (73.8%) | 322,343 (74.9%) |

| Near side | 1,095 (8.0%) | 2,487,780 (6.1%) | 536 (9.5%) | 109,673 (7.4%) | 367 (10.7%) | 81,500 (9.6%) | 210 (11.5%) | 39,208 (9.1%) |

| Far side | 1,072 (7.8%) | 290,697 (7.1%) | 447 (8.0%) | 89,601 (6.1%) | 296 (8.6%) | 61,150 (7.2%) | 183 (10.1%) | 36,049 (8.4%) |

| Rear | 749 (5.5%) | 213,610 (5.2%) | 353 (6.3%) | 109,848 (7.4%) | 205 (6.0%) | 63,590 (7.5%) | 84 (4.6%) | 32,648 (7.6%) |

| Vehicle Type | ||||||||

| Car | 9,497 (69.3%) | 2,813,795 (68.5%) | 3,661 (65.1%) | 932,895 (63.1%) | 2,293 (66.9%) | 572,757 (67.6%) | 1,277 (70.2%) | 300,795 (70.0%) |

| SUV | 2,393 (17.4%) | 764,871 (18.7%) | 1,022 (18.2%) | 339,716 (22.9%) | 593 (17.3%) | 160,811 (19.0%) | 272 (15.0%) | 66,982 (15.5%) |

| Van | 698 (5.1%) | 218,756 (5.3%) | 406 (7.2%) | 98,222 (6.6%) | 236 (6.9%) | 46,563 (5.5%) | 142 (7.8%) | 29,378 (6.8%) |

| Pickup | 1,123 (8.2%) | 307,453 (7.5%) | 532 (9.5%) | 109,509 (7.4%) | 304 (8.9%) | 67,710 (7.9%) | 128 (7.0%) | 33,093 (7.7%) |

| Restraint Use | ||||||||

| Belted | 10,719 (78.2%) | 3,354,797 (81.7%) | 4,865 (86.6%) | 1,284,098 (86.7%) | 3,001 (87.6%) | 774,325 (91.3%) | 1,578 (86.8%) | 391,951 (91.1%) |

| Unbelted | 2,992 (21.8%) | 750,078 (18.3%) | 756 (13.4%) | 196,244 (13.3%) | 423 (12.4%) | 73,516 (8.7%) | 241 (13.2%) | 37,298 (8.9%) |

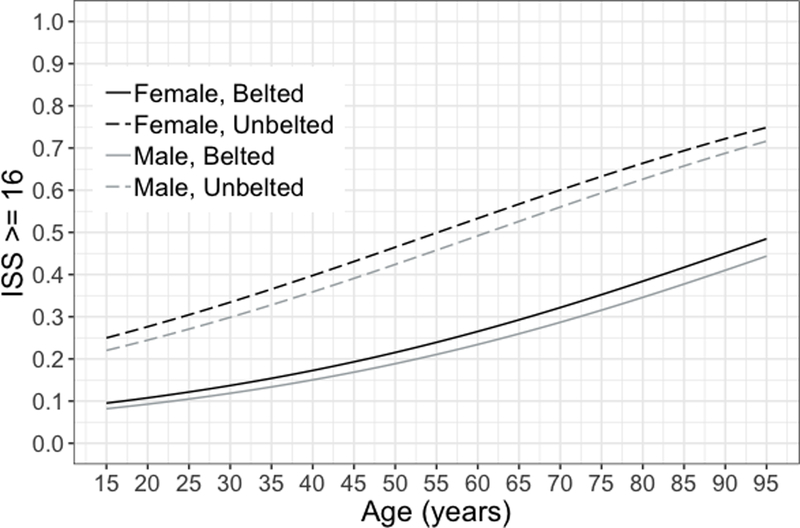

Age was found to be a significant predictor of injury risk in all models. Figure 1 shows an injury risk curve for a single iteration of the models predicting severe injury (ISS ≥ 16) using a training set of data from all adults. This curve illustrates the risk of severe injury of a driver in a car involved in a single impact, frontal collision at 56 kph (35 mph). The risk of severe injury is nearly doubled for a 60-year-old occupant compared to a 30-year-old. The risk of injury is predicted to be higher for females and unbelted occupants at all ages.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of the driver of a car involved in a single impact, 56 kmph (35 mph) frontal collision sustaining a severe injury (ISS≥16) based on age, gender, and belt status. ISS: Injury Severity Scale.

Accuracy of Models

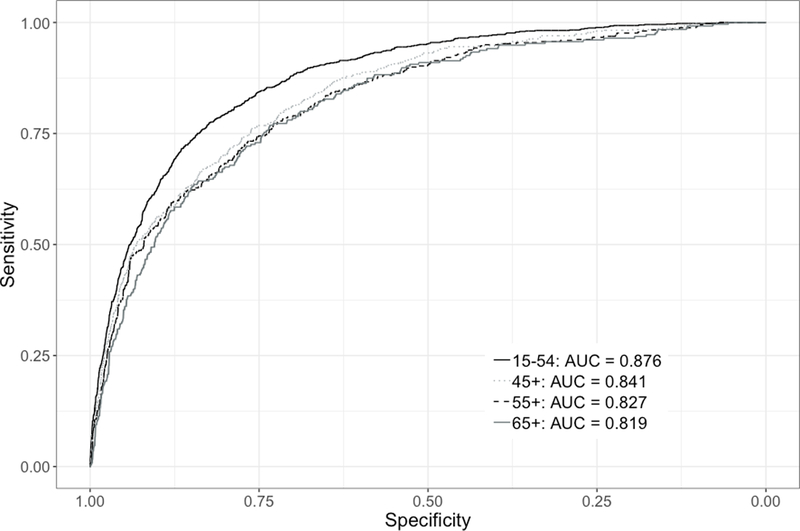

The models were assessed using different age ranges from the test data set. Figure 2 shows the ROC curves for different age ranges for a single iteration. The model had good performance for occupants 15–54 years, however the accuracy decreased similarly for occupants ≥ 45 years, ≥ 55 years and ≥ 65 years. This pattern persisted after the process was repeated for multiple iterations. The mean AUC for occupants 15–54 years was 0.874 [95% CI: 0.851–0.895], ages ≥ 45 years was 0.837 [95% CI: 0.802–0.869], ages ≥ 55 years was 0.821 [95% CI: 0.775–0.864], and ≥ 65 years was 0.813 [95% CI: 0.754–0.866] across 1,000 iterations. The models trained using data from the specific age groups 15–54 years, ≥ 45 years, ≥ 55 years, and ≥ 65 years had similar accuracy when tested with data from their respective age groups (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves and area under curve (AUC) of sensitivity and specificity for detecting severe injury (ISS≥16) in adult occupants of different age ranges.

Table 2 –

Performance of models to predict severe injury (ISS≥16). The model built using data from all ages compared to models built using only data from specific age groups. Results are reported as the mean ROC-AUC after 1,000 split sample iterations with 95% confidence intervals defined by the range that includes 95% of the AUCs.

| 15–54 Years | 45+ Years | 55+ Years | 65+ Years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Data Model | 0.874 [0.851–0.895] | 0.837 [0.802–869] | 0.821 [0.775–0.864] | 0.813 [0.754–0.866] |

| 15–54 Years Model | 0.874 [0.851–0.896] | |||

| 45+ Years Model | 0.836 [0.798–871] | |||

| 55+ Years Model | 0.822 [0.779–0.864] | |||

| 65+ Years Model | 0.808 [0.748–0.868] |

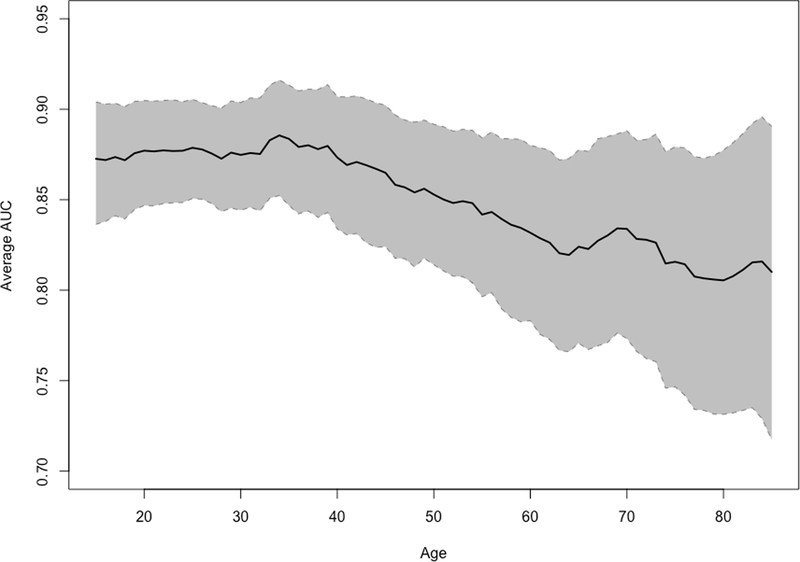

The accuracy of the severe injury risk model appeared to decrease approximately linearly with increasing age. The results from testing the model with a sliding 20-year window showed the mean ROC-AUC decreased from close to 0.9 around age 25 to less than 0.8 around age 85 years (Figure 3). The 95% confidence interval increased at the older ages.

Figure 3.

Performance of models to predict severe injury (ISS≥16) when tested in different ages. Each point on the line represents a 20-year window centered on a particular age (i.e. data point at age 40 represents 30–50 years). Results are reported as the average ROC-AUC after 1,000 split-sample iterations with range that includes 95% of results. ISS: Injury Severity Scale.

Triage Sensitivity and Specificity

The specificity of the models for detecting severe injury (ISS ≥ 16) was 0.49 in all adults when weighted to represent all tow-away crashes in the US, representing a 51% overtriage rate (calculated as 1-specificity) (Table 3). This very near the target of ≤ 50% overtriage rate recommendation of the ACS-COT. This borderline specificity appeared to be driven primarily by older adults. When the adults aged 15–54 years were examined separately, the specificity was 0.50, representing a 50% overtriage rate. However, older adults had substantial lower specificity [[≥45 years: 0.39, ≥55 years: 0.30, ≥65 year: 0.29], corresponding to 61%, 70% and 71% overtriage rates, which all substantially exceeds the 50% overtriage rate ACS-COT recommendation. This low specificity would result in significant overtriage in order to not exceed the ACS-COT recommended 5% rate of undertriage.

Table 3 –

Specificity of the risk prediction model for predicting correct triage for different age ranges. The sensitivity was held at 95% (undertriage rate 5%) based on ACS-COT recommendations. These results are based on triaging patients to a trauma center if there is severe injury (ISS≥16). Results are weighted based on national representation estimate. [ISS-Injury Severity Scale]

| Specificity | Overtriage | |

|---|---|---|

| All Occupants | 0.49 | 51% |

| 15–54 years | 0.50 | 50% |

| ≥45 years | 0.39 | 61% |

| ≥55 years | 0.30 | 70% |

| ≥65 years | 0.29 | 71% |

DISCUSSION

The determination of severe injury is important since appropriate trauma triage has been linked to improved mortality (MacKenzie et al. 2006; Sasser et al. 2012). It has been demonstrated that patients, and especially older adults, are often not taken to trauma centers even when they meet CDC triage criteria (Voskens et al. 2018). This is concerning because older adults are more likely to die from traumatic injuries (Johnson et al. 1994; Kuhne et al. 2005) and the risk of severe injury increases with age. While more sophisticated methods for triage have the potential to decrease mortality rates, they may fail to account for potential limitations in older adult populations.

The results of this study demonstrated that commonly used regression-based risk prediction techniques produce models that are not as accurate for older individuals as opposed to younger. Overall, the models produced in this study showed good predictive ability, similar to results produced by Kononen et al. (2011). However, the accuracy of predictions appears to steadily decrease each decade of life. The accuracy in older adults was not improved when models were trained using only data from the respective age groups. This suggests that the differences in sensitivity and specificity may be due to intrinsic differences between age groups.

The difference in predictive ability is likely due to the larger range of health status and comorbidities in older adults. Although occupants may have the same chronological age, there may be considerable variability in terms of frailty and function (Bandeen-Roche et al. 2015; Rockwood and Mitnitski 2007). Bone health and muscle volume may be a particularly important aspect of this variation as bony fractures make up a large portion of the more severe injuries sustained in MVCs (Fairchild et al. 2015; Joseph et al. 2017; Kaplan et al. 2017). Previous research has shown that the chest region has the largest increase in risk of internal injury in older adults after adjusting for crash severity (Hartka et al. 2018). The large majority of these internal injuries are rib fractures in adults, so differences in bone strength may be a primary driver of variations in susceptibility to injury from MVC (Saffarzadeh et al. 2016). Unfortunately, the NASS-CDS dataset does not include sufficient data on comorbid health conditions to draw conclusions definitively.

The difference in accuracy of injury prediction resulted in a clinically meaningful difference in triage rates. While the injury risk prediction models could successfully meet the recommended rates of undertriage and overtriage for adults aged 15–54 years, these targets were not met in older adults. More older adults would therefore need to be sent to trauma centers who did not require these resources in order to prevent exceeding the recommended rate of undertriage. This overtriage of older adults has the potential to strain the capacity of trauma centers and lead to considerable expense.

The possible solutions to this problem of decreased accuracy for older adults are not clear. However, these findings can serve to increase awareness that models to predict injury severity have significant limitations in older adults. The CDC guidelines for trauma triage acknowledge this increased vulnerability of older individuals to trauma. The guidelines state that for older adults “Risk of injury/death increases after age 55 years” and “Low impact mechanisms might result in severe injury” (Sasser et al. 2012). As AACN technology becomes more pervasive, prehospital systems need to recognize that the available crash data may be insufficient for this population. Further research is needed to determine how to provide better estimations in this population. The incorporation of known comorbidities would likely improve accuracy, but would fail to capture the increased risk in occupants with undiagnosed or sub-clinical conditions.

There are several limitations to this study. Importantly, this analysis is based on retrospective data. NASS-CDS collects data through hospital data when possible and then uses patient-reported outcomes for occupants not treated at a hospital. It is possible there may be under-reporting or over-reporting of certain injuries. Other limitations stem from the quantities of data available. Less data is available for older occupants since they make up a smaller portion of the pool of active drivers. While this may have affected our results, we have performed additional analysis with up-sampled and down-sampled data which yielded similar results (Appendix 1). There were also baseline differences in the various age groups which affect model performance. However, these differences mirror the demographic for trauma patients that would require triage in actual practice.

This study is also limited by the methods for evaluating injury severity and comparing models. ISS has limitations as a marker for injury severity. Various combinations of injuries can produce an ISS of ≥16, such as three moderate injuries or one severe injury, which may have very different outcomes. Despite this fact, ISS ≥16 is commonly used to defining severe trauma (Center for Disease Control 2008; Cox et al. 2012; Kononen et al. 2011; Lossius et al. 2012; Weaver et al. 2015). Additionally, ROC-AUC is not a perfect method for evaluating models. However, while ROC-AUC does not fully describe the performance of a risk prediction model, it is useful in comparing similar models (Zou Kelly H. et al. 2007).

Automatic prediction of severe injury based on crash telemetry data has the potential to improve appropriate trauma triage after an MVC, but these methods are significantly less accurate in older adults. Our injury prediction models did not meet the trauma triage metrics recommended by ACS-COT in older occupants. These findings are likely due to increased variability in frailty and comorbidities in older adults. Current injury prediction models should not be relied upon solely for triage of older patients after MVCs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work of the primary author was conducted with the support of the iTHRIV Scholars Program. The iTHRIV Scholars Program is supported in part by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UL1TR003015 and KL2TR003016. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Thomas Hartka, University of Virginia, Emergency Medicine.

Christina Gancayco, University of Virginia, Research Computing.

Tim McMurry, University of Virginia, PBHS Public Health Sciences Admin.

Marina Robson, University of Virginia, School of Medicine.

Ashley Weaver, Wake Forest University, Biomedical Engineering.

REFERENCES

- Adams SD, Holcomb JB. Geriatric trauma. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2015;21(6):520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association for the Advancement of Automatic Medicine. The Abbreviated Injury Scale, 1990 Revision, Update 98. Barrington, IL; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Augenstein J, Digges K, Ogata S, Perdeck E, Stratton J. Development and Validation of the URGENCY Algorithm to Predict Compelling Injuries. Proceedings of the 17th International Technical Conference on the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles (ESV) 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Augenstein J, Perdeck E, Stratton J, Digges K, Steps J, Bahouth G. Validation of the urgency algorithm for near-side crashes. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2002;46:305–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandeen-Roche K, Seplaki CL, Huang J, Buta B, Kalyani RR, Varadhan R, Xue Q-L, Walston JD, Kasper JD. Frailty in Older Adults: A Nationally Representative Profile in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1427–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsi C, Harris P, Menaik R, Reis NC, Munnangi S, Elfond M. Risk factors and mortality associated with undertriage at a level I safety-net trauma center: a retrospective study. Open Access Emerg Med. 2016;8:103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CR, Tolson MA, Copes WS. Evaluating trauma care: the TRISS method. Trauma Score and the Injury Severity Score. J Trauma. 1987;27(4):370–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. Recommendations from the Expert Panel: Advanced Automatic Collision Notification and Triage of the Injured Patient. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cox S, Currell A, Harriss L, Barger B, Cameron P, Smith K. Evaluation of the Victorian state adult pre-hospital trauma triage criteria. Injury. 2012;43(5):573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman AB. Resources for optimal care of the injured patient−−1993. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1994;79(5):21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild B, Webb TP, Xiang Q, Tarima S, Brasel KJ. Sarcopenia and Frailty in Elderly Trauma Patients. World J Surg. 2015;39(2):373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu TS, Jing R, McFaull SR, Cusimano MD. Recent trends in hospitalization and in-hospital mortality associated with traumatic brain injury in Canada: A nationwide, population-based study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(3):449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartka T, Kao C, McMurry T. Develop of injury risk models to guide CT evaluation in the Emergency Department after motor vehicle collisions. Association of the Advancement of Automotive Medicine Annual Meeting. 2018:Submission pending acceptance. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydel MJ, Preston CA, Mills TJ, Luber S, Blaudeau E, DeBlieux PM. Indications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343(2):100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron M National VitalStatistics Reports. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2015. 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JR, Mower WR, Wolfson AB, Todd KH, Zucker MI. Validity of a set of clinical criteria to rule out injury to the cervical spine in patients with blunt trauma. National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343(2):94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns JJ, Cantrill SV, Gean AD, Howard PK, Ghajar J, Riggio S, Wright DW, Wears RL, Bakshy A, Burgess P, Wald MM, Whitson RR. Clinical policy: neuroimaging and decisionmaking in adult mild traumatic brain injury in the acute setting. J Emerg Nurs. 2009;35(2):e5–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CL, Margulies DR, Kearney TJ, Hiatt JR, Shabot MM. Trauma in the elderly: an analysis of outcomes based on age. Am Surg. 1994;60(11):899–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph B, Orouji Jokar T, Hassan A, Azim A, Mohler MJ, Kulvatunyou N, Siddiqi S, Phelan H, Fain M, Rhee P. Redefining the association between old age and poor outcomes after trauma: The impact of frailty syndrome. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2017;82(3):575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SJ, Pham TN, Arbabi S, Gross JA, Damodarasamy M, Bentov I, Taitsman LA, Mitchell SH, Reed MJ. Association of Radiologic Indicators of Frailty With 1-Year Mortality in Older Trauma Patients: Opportunistic Screening for Sarcopenia and Osteopenia. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(2):e164604–e164604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodadek LM, Selvarajah S, Velopulos CG, Haut ER, Haider AH. Undertriage of older trauma patients: is this a national phenomenon? J. Surg. Res. 2015;199(1):220–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kononen DW, Flannagan CAC, Wang SC. Identification and validation of a logistic regression model for predicting serious injuries associated with motor vehicle crashes. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2011;43(1):112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhne CA, Ruchholtz S, Kaiser GM, Nast-Kolb D. Mortality in Severely Injured Elderly Trauma Patients—When Does Age Become a Risk Factor? World J. Surg 2005;29(11):1476–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib N, Nouh T, Winocour S, Deckelbaum D, Banici L, Fata P, Razek T, Khwaja K. Severely Injured Geriatric Population: Morbidity, Mortality, and Risk Factors. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2011;71(6):1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossius HM, Rehn M, Tjosevik KE, Eken T. Calculating trauma triage precision: effects of different definitions of major trauma. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2012;6(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, Salkever DS, Scharfstein DO. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N. Engl. J. Med 2006;354(4):366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2017;Vienna, Austria: Available at: https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in Relation to the Accumulation of Deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotondo M Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. 6th edition. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons-Committee on Trauma; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saffarzadeh M, Hightower RC, Talton JW, Miller AN, Stitzel JD, Weaver AA. Multicenter analysis of CIREN occupant lumbar bone mineral density and correlation with age and fracture incidence. Traffic Inj Prev. 2016;17 Suppl 1:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampalis JS, Nathanson R, Vaillancourt J, Nikolis A, Liberman M, Angelopoulos J, Krassakopoulos N, Longo N, Psaradellis E. Assessment of Mortality in Older Trauma Patients Sustaining Injuries from Falls or Motor Vehicle Collisions Treated in Regional Level I Trauma Centers. Annals of Surgery. 2009;249(3):488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasser SM, Hunt RC, Faul M, Sugerman D, Pearson WS, Dulski T, Wald MM, Jurkovich GJ, Newgard CD, Lerner EB, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for field triage of injured patients: recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage, 2011. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-1):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søreide K, Krüger AJ, Vårdal AL, Ellingsen CL, Søreide E, Lossius HM. Epidemiology and Contemporary Patterns of Trauma Deaths: Changing Place, Similar Pace, Older Face. World J Surg. 2007;31(11):2092–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiell IG, Clement CM, McKnight RD, Brison R, Schull MJ, Rowe BH, Worthington JR, Eisenhauer MA, Cass D, Greenberg G, MacPhail I, Dreyer J, Lee JS, Bandiera G, Reardon M, Holroyd B, Lesiuk H, Wells GA. The Canadian C-Spine Rule versus the NEXUS Low-Risk Criteria in Patients with Trauma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(26):2510–2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiell IG, Clement CM, Rowe BH, Schull MJ, Brison R, Cass D, Eisenhauer MA, McKnight RD, Bandiera G, Holroyd B, Lee JS, Dreyer J, Worthington JR, Reardon M, Greenberg G, Lesiuk H, MacPhail I, Wells GA. Comparison of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005;294(12):1511–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel JD, Kilgo PD, Danelson KA, Geer CP, Pranikoff T, Meredith JW. Age thresholds for increased mortality of three predominant crash induced head injuries. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2008;52:235–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel JD, Kilgo PD, Weaver AA, Martin RS, Loftis KL, Meredith JW. Age Thresholds for Increased Mortality of Predominant Crash Induced Thoracic Injuries. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2010;54:41–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel JD, Weaver AA, Talton JW, Barnard RT, Schoell SL, Doud AN, Martin RS, Meredith JW. An Injury Severity-, Time Sensitivity-, and Predictability-Based Advanced Automatic Crash Notification Algorithm Improves Motor Vehicle Crash Occupant Triage. J. Am. Coll. Surg 2016;222(6):1211–1219.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefft B Rates of Motor Vehicle Crashes, Injuries and Deaths in Relation to Driver Age, United States, 2014–2015. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Voskens FJ, van Rein EAJ, van der Sluijs R, Houwert RM, Lichtveld RA, Verleisdonk EJ, Segers M, van Olden G, Dijkgraaf M, Leenen LPH, van Heijl M. Accuracy of Prehospital Triage in Selecting Severely Injured Trauma Patients. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(4):322–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver AA, Talton JW, Barnard RT, Schoell SL, Swett KR, Stitzel JD. Estimated injury risk for specific injuries and body regions in frontal motor vehicle crashes. Traffic Inj Prev. 2015;16 Suppl 1:S108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Kelly H, O’Malley A James, Mauri Laura. Receiver-Operating Characteristic Analysis for Evaluating Diagnostic Tests and Predictive Models. Circulation. 2007;115(5):654–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.