Abstract

Rationale:

Lipid overload-induced heart dysfunction is characterized by cardiomyocyte death, myocardial remodeling, and compromised contractility, but the impact of excessive lipid supply on cardiac function remains poorly understood.

Objective:

To investigate the regulation and function of the mitochondrial fission protein dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) in lipid overload-induced cardiomyocyte death and heart dysfunction.

Methods and Results:

Mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) developed signs of obesity and type II diabetes, including hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and hypertension. HFD for 18 weeks also induced heart hypertrophy, fibrosis, myocardial insulin resistance, and cardiomyocyte death. HFD stimulated mitochondrial fission in mouse hearts. Furthermore, HFD increased the protein level, phosphorylation (at the activating serine 616 site), oligomerization, mitochondrial translocation, and GTPase activity of Drp1 in mouse hearts, indicating that Drp1 was activated. Monkeys fed a diet high in fat and cholesterol for 2.5 years also exhibited myocardial damage and Drp1 activation in the heart. Interestingly, HFD decreased NAD+ levels and increased Drp1 acetylation in the heart. In adult cardiomyocytes, palmitate increased Drp1 acetylation, phosphorylation, and protein levels, and these increases were abolished by restoration of the decreased NAD+ level. Proteomics analysis and in vitro screening revealed that Drp1 acetylation at lysine 642 (K642) was increased by HFD in mouse hearts and by palmitate incubation in cardiomyocytes. The non-acetylated Drp1 mutation (K642R) attenuated palmitate-induced Drp1 activation, its interaction with voltage-dependent anion channel 1, mitochondrial fission, contractile dysfunction, and cardiomyocyte death.

Conclusions:

These findings uncover a novel mechanism that contributes to lipid overload-induced heart hypertrophy and dysfunction. Excessive lipid supply created an intracellular environment that facilitated Drp1 acetylation, which, in turn, increased its activity and mitochondrial translocation, resulting in cardiomyocyte dysfunction and death. Thus, Drp1 may be a critical mediator of lipid overload-induced heart dysfunction as well as a potential target for therapy.

Keywords: Lipid overload, dynamin related protein 1, protein acetylation, mitochondrial dysfunction, heart dysfunction in type II diabetes, lipid toxicity, mitochondria, redox

Subject Terms: Animal Models of Human Disease, Basic Science Research, Cell Biology/Structural Biology, Metabolism, Obesity

Graphical Abstract

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of abnormalities characterized by obesity and insulin resistance, which compromise energy metabolism, damage mitochondria, cause cardiomyocyte death, and eventually impair heart contraction and relaxation performance. Despite the increasing prevalence of heart complications in obese and diabetic patients, our knowledge on how obese and diabetes impair heart function is very limited. In this study, we used animal and cell culture models in rodents or monkeys and generated lipid overload models to mimic obesity conditions. We found that excessive lipid supply decreased NAD+ levels and increased the acetylation of a fission protein Drp1 at a specific lysine residue (K642). Drp1 acetylation at K642 activated Drp1 through phosphorylation, mitochondrial translocation, and oligomerization. The excessively activated Drp1 had higher GTPase activity, bound with VDAC1 on mitochondria, induced mitochondrial fission, and caused cardiomyocyte death. These findings provide new information regarding how lipid overload regulates redox environment, protein acetylation, and the function of mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 in the heart.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a pandemic in the US and a leading risk factor for chronic diseases, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease.1 Obesity and diabetes can cause heart dysfunction indirectly through hypertension and atherosclerosis or directly via disturbance of the metabolism and function of cardiomyocytes.2–4 Lipid overload is a key trigger for heart dysfunction, because it inhibits glucose utilization and causes lipotoxicity.5 Although the heart relies mostly on fatty acids to provide ATP for its pumping function, excessive lipid supply may overrun fatty acid oxidation capacity and compromise intracellular energetics.6 The mechanisms by which lipid overload induces heart dysfunction are not fully elucidated.

Increased fatty acid oxidation suppresses glucose metabolism through the Randle cycle and causes metabolic inflexibility.7 Excessive lipids also lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and lipotoxicity.8–10 Recently, reductive stress is linked to insulin resistance in kidneys and skeletal muscles.11 A perturbed redox state is found in the hearts of type I and type II diabetes models and may be responsible for mitochondrial and cardiomyocyte dysfunction.12 Increased protein acetylation is found in the hearts of type I and type II diabetes models, indicating that the redox environment is imbalanced in vivo.13, 14 The precise changes and roles of intracellular redox environment in obesity-induced heart dysfunction have not been studied.12

Mitochondrial dysfunction is another feature of metabolic syndrome. A chronically elevated substrate supply depletes NAD+, causes accumulation of metabolic intermediates such as acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), promotes ROS generation, and predisposes mitochondria to damage.15 Mitochondrial damage is often linked to morphological changes. Indeed, fragmented mitochondria or increased mitochondrial fission is reported in cardiomyocytes incubated with high levels of glucose or fatty acids.16, 17 A recent report showed that excessive lipid uptake in the heart impacts dynamics proteins, including dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), and induces mitochondrial fission and dysfunction.18 The non-canonical functions of Drp1 may play a critical role in heart disease.19 For instance, Drp1 stimulates opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and contributes to heart dysfunction in ischemia-reperfusion injury and during chronic β adrenergic receptor activation.20, 21 The mechanisms of Drp1 activation by lipid overload and the role of Drp1 in lipid overload-induced heart dysfunction remain unknown.

The aims of this study were to determine whether lipid overload regulates Drp1 activity through modulation of the intracellular redox environment and to explore the mechanism by which excessively activated Drp1 compromises cardiomyocyte viability and function. We used a high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mouse model, a high-fat and high-cholesterol (HFHC) diet-fed monkey model, and an in vitro palmitate incubation model.14, 22, 23 We found that lipid overload created a redox environment to activate Drp1 through acetylation. Furthermore, excessively activated Drp1 translocated to mitochondria, induced mPTP and apoptosis, and compromised cardiomyocyte contractile function via the voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1). These findings highlight acetylation as a novel post-translational Drp1 modification that regulates its activity, contributing to metabolic stress-associated cardiomyocyte death and dysfunction.

METHODS

All supporting data are available within the article and Online Data Supplement. Raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

All rodent (mice and rats) experiments were performed in accordance with the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Washington. Male and female mice (C57BL/6, Charles River) and rats (Sprague Dawley, Harlan) were used. All rhesus monkey experiments were approved by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Intramural Program Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were maintained on the specified diet for 2.5 years at NIA. Detailed Methods and Materials are provided in the Online Data Supplement.

RESULTS

Lipid overload caused metabolic syndrome, heart dysfunction, and mitochondrial fission in mice.

Mice fed a high fat diet (HFD), in which 60% of the calories come from fat, serve as a widely used model for obesity and type II diabetes. C57BL/6 mice that were fed HFD for up to 18 weeks exhibited obesity and increased concentrations of fatty acids and lipids, including palmitate (C16:0), oleate (C18:1), cholesterol and ceramide, in plasma and heart tissues (Online Figure I A–B, Figure 1A, and Online Tables I–II). These mice also developed hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance as revealed by the glucose tolerance test (Online Figure I C–D and Figure 1B). HFD-induced heart dysfunction was evidenced by hypertrophy (increased heart weight-to-tibia length ratio, left ventricular mass, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels, Figure 1C), mildly declined contractility (Figure 1D), myocardial insulin resistance (decreased Akt phosphorylation), myocardial fibrosis (increased galectin-3 levels), and apoptosis (increased cleaved caspase 9 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) levels) (Figure 1E and Online Figure I E). HFD for 18 weeks also decreased LC3II/LC3BI ratio (Figure 1E), indicating that autophagy may be suppressed, which was consistent with previous reports.24 HFD did not alter aconitase activity, indicating lack of oxidative stress (Online Figure I F). In addition, mitochondrion size was decreased in the heart after 18 weeks of HFD (Figure 1F), consistent with previous reports that demonstrated an association between lipid overload and mitochondrial fission.17, 18 These results suggest that lipid overload induced obesity and type II diabetes in mice and caused myocardial damage, cardiomyocyte death, and mitochondrial morphological changes in the heart.

Figure 1. High-fat diet induced heart dysfunction in mice.

A, Palmitate (C16:0) and oleate (C18:1) levels in plasma (left) or heart samples (right) from mice fed regular rodent chow (RC) or high-fat diet (HFD) for 18 weeks. N=10 for each group. B, Plasma insulin levels (left, N=5–6) or diastolic and systolic blood pressure (right, N=9–12) in mice fed different diets for 18 weeks. C, Quantification of heart weight (HW) over tibia length (TL) ratio (N=5 for each group), Left ventricle (LV) mass (N=4–6), and plasma BNP levels (N=6) in mice fed different diets for 18 weeks. D, Fractional shortening (FS) in mice fed different diets. N=6. E, Western blotting images and summarized data showing phospho-Akt (Serine 473), total Akt, galectin-3, cleaved caspase 9, and LC3II/I protein levels in the hearts of mice fed different diets for 18 weeks. N=3–6. F, Electron microscopic images and quantification of mitochondrion size in mouse hearts. N=361–420 mitochondria from 5 mice for each group. Scale bar = 1 μm. *: P<0.05.

Lipid overload increased Drp1 protein level and activity in mouse hearts.

To investigate the mitochondrial morphological changes induced by lipid overload in the heart, we determined the protein levels of fission and fusion proteins. HFD increased the protein levels of the fission regulator Drp1 but did not change that of fusion proteins optic atrophy 1 (Opa1) and mitofusin1 (Mfn1) (Figure 2A and Online Figure II). Interestingly, increased Drp1 was mainly found in the mitochondrial fraction (Figure 2A). The translocation of Drp1 from cytosol to mitochondria is modulated by various signals and post-translational modifications.25 Phosphorylation of Drp1 at serine 616 (S616) promotes its translocation, oligomerization, GTPase activity, and fission.26 Phosphorylation of Drp1 at serine 637 (S637), however, is inhibitory.27 We found that HFD increased the phosphorylation of Drp1 at S616 in whole heart samples, cytosolic fractions, and mitochondrial fractions but decreased Drp1 phosphorylation at S637 in whole heart samples and mitochondrial fractions (Figure 2B–C). Next, using native PAGE gels, we revealed that Drp1 oligomers were increased in the heart, especially in mitochondrial fractions after 18 weeks of HFD (Figure 2D–E). Finally, HFD elevated the GTP-hydrolyzing activity of Drp1 in the heart (Figure 2F), consistent with a report that showed that Drp1 oligomerization enhances its GTPase activity.28 In summary, HFD upregulated Drp1 protein levels and modulated its phosphorylation, oligomerization, mitochondrial translocation, and GTPase activity in mouse hearts.

Figure 2. High-fat diet activated Drp1 in mouse hearts.

A, Western blotting images and summarized data showing Drp1 and Opa1 protein levels in whole heart (left) and Drp1 protein levels in mitochondrial or cytosolic fractions (right) from mice fed different diets for 18 weeks. N=5. B-C, Western blotting images and summarized data showing Drp1 phosphorylation at serine 616 (p-Drp1616) or serine 637 (p-Drp1637) in whole heart (B) or subcellular fractions (C) of mouse hearts. N=6. D-E, Western blotting images and summarized data showing Drp1 oligomerization (Drp1-o) in whole heart (D) or subcellular fractions (E) of mouse hearts. N=6. F, The GTPase activity of Drp1 in mouse hearts. N=3. *: P<0.05.

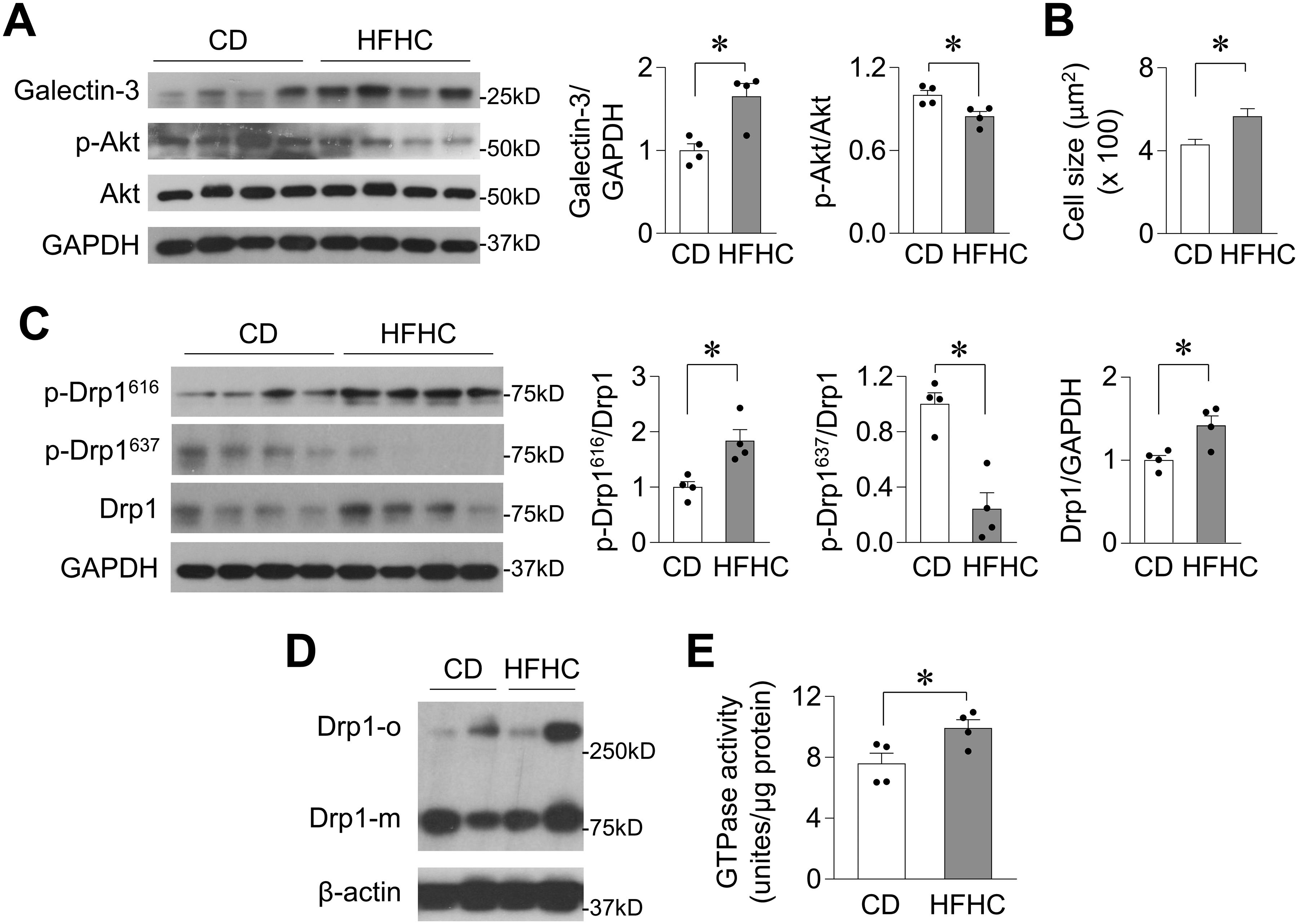

Lipid overload induced myocardial damage and activated Drp1 in monkey hearts.

To further explore the clinical significance of the above findings in rodent hearts, we determined Drp1 protein levels and activity in heart tissues of rhesus monkeys fed a high-fat and high-cholesterol (HFHC) diet for 2.5 years. The monkeys exhibited ~2-fold increase in blood cholesterol levels and signs of increased atherosclerosis burden. Analyses of whole heart images revealed unchanged gross morphology (Online Figure III A–D); however, evaluations of molecular markers and myocardium histology revealed myocardial damage. First, galectin-3 levels were significantly increased and Akt phosphorylation was decreased, suggesting inflammation, fibrosis, and insulin resistance in HFHC diet-fed monkey hearts (Figure 3A). Histological analysis showed an increase in cardiomyocyte size, elevated inflammation, collagen patches, and lipid accumulation in the left ventricles of HFHC diet-fed monkeys (Figure 3B and Online Figure III E–H).

Figure 3. High-fat and high-cholesterol diet damaged myocardium and activated Drp1 in monkey hearts.

A, Western blotting images and summarized data showing galectin-3, Akt phosphorylation (p-Akt), Akt, and GAPDH levels in the heart of monkeys fed a control diet (CD) or a high-fat and high-cholesterol (HFHC) diet for 2.5 years. N=4 per group. B, Summarized data showing cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes in the left ventricular free wall of monkey hearts. N=140–156 cells from 4 monkeys in each group. C-D, Western blotting images and summarized data showing Drp1 phosphorylation and protein level (C, N=4) and Drp1 oligomerization (D, N=2) in monkey heart samples. E, The GTPase activity of Drp1 in monkey heart samples. N=4. *: P<0.05.

In the HFHC diet-fed monkey hearts, Drp1 protein levels and phosphorylation at S616 were elevated, while phosphorylation of Drp1 at S637 was decreased (Figure 3C). Drp1 oligomerization levels tended to increase, and Drp1 GTPase activity was higher in HFHC diet-fed monkey hearts (Figure 3D–E and Online Figure III I). These results indicated that chronic lipid overload also caused myocardial damage and activated Drp1 in the hearts of non-human primates.

Lipid overload created an intracellular environment that promoted Drp1 acetylation.

Next, we investigated the mechanisms underlying the upregulation of Drp1 by lipid overload. HFD did not change Drp1 mRNA levels in the heart (Online Figure IV A), suggesting transcriptional regulation is unlikely the underlying mechanism. Thus, we hypothesized that post-translational modification of Drp1 may be responsible for increased Drp1 protein levels. To test this hypothesis, we first determined changes in intracellular metabolic intermediates, which regulate protein acetylation and are altered by lipid overload.29 Indeed, HFD significantly decreased total intracellular NAD+ content in the heart (Figure 4A, left). We also estimated cytosolic free NAD+ levels by measuring the ratio of lactate and pyruvate, an indirect index that is linked to cytosolic NAD+/NADH, in heart tissues. The conversion between lactate and pyruvate is catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase and depends on cytosolic free NAD+ and NADH levels.30 This analysis showed that the cytosolic free NAD+/NADH ratio was also lower in the heart after HFD (Figure 4A, right), consistent with the observed decreased total NAD+ content. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) is a key enzyme involved in NAD+ biosynthesis, and its level is decreased in liver and white adipose tissue after HFD.31 We found that HFD also downregulated NAMPT protein levels in the heart (Figure 4B), which may compromise NAD+ biosynthesis. In addition, HFD also elevated acetyl-CoA levels in the heart (Figure 4C). In line with these biochemical changes, total protein acetylation and Drp1 acetylation were increased in the hearts of HFD-fed mice and HFHC diet-fed monkeys (Figure 4D–F and Online Figure IV B). The increased Drp1 acetylation was mainly observed in the mitochondrial fraction and not in the cytosolic fraction (Figure 4G), implying that acetylation is coupled with Drp1 translocation to mitochondria.

Figure 4. High-fat diet created an intracellular environment that promoted Drp1 acetylation.

A, Total NAD+ content (left, N=3–4) and cytosolic free NAD+/NADH ratios (right, N=7) in heart tissues from mice fed different diets for 18 weeks. B, Protein levels of NAMPT in mouse hearts. N=3. C, Acetyl-CoA levels in mouse hearts. N=4. D, Total protein acetylation levels in the heart of mice fed different diets for 18 weeks. N=4. E-G, Western blotting images and summarized data showing Drp1 acetylation in mouse hearts (E), monkey hearts (F), or subcellular fractions of mouse hearts (G). N=4–6. *: P<0.05.

Palmitate upregulated Drp1 acetylation and activity in adult cardiomyocytes.

To explore whether decreased NAD+ facilitates Drp1 acetylation and regulates its protein levels and activity, we employed cultured adult cardiomyocytes due to the feasibility of manipulating signaling proteins genetically. To prove that this is a suitable model, we first recapitulated the above HFD-induced changes in Drp1 in the cultured adult cardiomyocytes under lipotoxicity. Palmitate is a major saturated fatty acid in the plasma, and HFD increased palmitate levels in mouse hearts (Figure 1A). Palmitate can cause deleterious effects in cultured cells.22, 23 Therefore, we incubated adult rat cardiomyocytes with palmitate (0.3 mmol/L) for up to 24 hr and found that palmitate decreased total intracellular NAD+ levels (Figure 5A, left). In addition, overexpression of a genetic fluorescent NAD(H) indicator SoNar32 revealed that palmitate lowered cytosolic free NAD+/NADH ratios (Figure 5A, right and Online Figure V A), implying that cytosolic free NAD+ levels may be decreased as well. Moreover, palmitate downregulated the protein levels of NAMPT and Sirt1, upregulated the protein levels of acetyl-CoA synthetase, and promoted protein acetylation in adult cardiomyocytes (Figure 5B and Online Figure V B–C). These changes were consistent with our abovementioned findings in HFD-fed mouse hearts (Figure 4A–D) as well as previous results from other tissues.31, 33

Figure 5. Lipid overload activated Drp1 in adult cardiomyocytes.

A, Total intracellular NAD+ content (left, N=3–9) and cytosolic free NAD+/NADH ratios monitored by SoNar indicator (right, N=28–29 cells from 3 rats) in adult cardiomyocytes incubated with palmitate (Pal, 0.3 mmol/L) and with pretreatment of NAD+ precursor NMN (500 μmol/L). B, Effects of palmitate (0.3 mmol/L, 24 hr) on the protein levels of NAMPT (left), Sirt1, and acetyl-CoA synthetase (ac-CoA syn) (right) in adult cardiomyocytes. N=3 rats. C, Dose- (left, N=6) and time-dependent (middle, N=4) effects of palmitate on Drp1 acetylation with or without NAD+ precursor (NR, 1 mmol/L) and the effect of overexpressing NAMPT on palmitate-induced Drp1 acetylation (right, N=3) in adult cardiomyocytes. D, Western blotting images and summarized data showing time-dependent effects of palmitate (0.3 mmol/L) on Drp1 and Opa1 protein levels in adult cardiomyocytes. N=3–9 rats. E, Western blotting images showing time- and dose-dependent effects of palmitate on Drp1 S616 phosphorylation in adult cardiomyocytes and with pretreatment of NAD+ precursor (NR, 1 mmol/L). N=5–6 rats. F, Western blotting images and summarized data showing Drp1 oligomerization (Drp1-o) in adult cardiomyocytes. N=6 rats. G, Representative confocal images and summarized data showing GFP-Drp1 puncta in live adult cardiomyocytes. N=109–177 puncta from 3–4 rats. Scale bars = 20 or 5 μm for the whole cell or enlarged images, respectively. *: P<0.05.

Palmitate dose- and time-dependently increased Drp1 acetylation, which was blocked by supplementation with the NAD+ precursor nicotinamide ribose chloride (NR, 1 mmol/L) or overexpression of NAMPT (Figure 5C). Moreover, palmitate elevated Drp1 protein levels in adult cardiomyocytes, and the increase was blocked by overexpression of NAMPT or supplementation of NAD+ precursor nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN, 500 μmol/L) (Figure 5D and Online Figure V D–E). In addition, palmitate time- and dose-dependently increased Drp1 S616 phosphorylation, which was abolished by NR (1 mmol/L, Figure 5E and Online Figure V F). Palmitate also induced Drp1 oligomerization as determined by native PAGE analysis of whole cell lysates or by tracking the puncta of overexpressed GFP-tagged Drp1 (GFP-Drp1) in live cardiomyocytes (Figure 5F–G). Palmitate increased the GTP-hydrolyzing activity of Drp1 in cardiomyocytes (Online Figure V G). Furthermore, palmitate induced mitochondrial fission, increased the sensitivity of mitochondria to laser-triggered mPTP opening, and caused cardiomyocyte death (Online Figure V H–J), consistent with the detrimental effects of palmitate and chronically elevated Drp1 activity in cardiomyocytes.21, 23 Taken together, these results indicate that palmitate altered cytosolic NAD+ levels and modulated Drp1 in adult cardiomyocytes similar to HFD in mouse hearts. Moreover, restoration of NAD+ levels blocked the increased Drp1 protein levels, Drp1 phosphorylation at S616, and Drp1 acetylation, suggesting that NAD+-mediated Drp1 acetylation regulates Drp1 protein levels and activity.

Interestingly, oleate, which is the most abundant unsaturated fatty acid in the plasma and exhibits significantly increased levels in HFD-fed mice (Figure 1A), had no effect on Drp1 protein levels, Drp1 phosphorylation at S616, or Drp1 acetylation in adult cardiomyocytes (Online Figure V K–L). Moreover, oleate had no effect on cardiomyocyte viability (Online Figure V M), in contrast to the detrimental effect of palmitate on cultured cells (Online Figure V J).22 These results indicate that the monounsaturated long-chain fatty acid oleate may not be involved in Drp1 regulation and Drp1 regulation in the heart could be a class effect of saturated and unsaturated long-chain fatty acids.

Identification of the lysine residue in Drp1 that is acetylated by lipid overload.

Drp1 acetylation has not been reported before. Thus, we further examined the Drp1 lysine residues that were acetylated by lipid overload. First, we purified Drp1 protein but did not observe acetylation via Western blotting. After acetyl-CoA incubation, a strong acetylation band was detected (Figure 6A). Next, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis of purified Drp1 proteins detected >80% of the amino acids and 36 of the 42 lysine residues in Drp1. Subsequent proteomics analysis revealed that 15 lysine residues were acetylated after in vitro acetyl-CoA incubation. To further determine whether HFD modulated acetylation of any of these lysine residues in vivo, we conducted LC-MS studies on whole heart samples after enrichment for Drp1 and acetylated proteins. Acetylated K75 and K642 residues were found in heart samples from HFD-fed mice, and no acetylated peptides were found in the hearts of regular chow-fed mice (Figure 6B). These data provide strong evidence that Drp1 is acetylated at specific sites by lipid overload in vivo.

Figure 6. Lipid overload increased Drp1 acetylation at lysine 642.

A, Western blotting images showing acetylation of purified Drp1 after incubation with acetyl-CoA (upper) and scheme showing the location of 10 lysine residues in Drp1 that can be acetylated in vitro (lower). The domains are GTPase domain (GTP), middle domain (M), B domain (B), and GTPase effector domain (GED). B, Mass spectrometry analysis of Drp1 acetylation showing the tandem mass spectrum of a Drp1 fragment containing the acetylated K642 (increased by 42 Da) in the heart samples of HFD-fed mice. C-E, Western blotting images showing the effects of palmitate (Pal, 0.3 mmol/L, 24 hr) on the protein levels (C), acetylation (D), and oligomerization (E) of overexpressed wild type (WT) or mutations of Drp1 (non-tagged) in HEK293 cells. N=5–6. F, Summarized data showing the effects of palmitate on mitochondrion size in HEK293 cells overexpressing various Drp1 mutations (non-tagged). N=16564–30141 mitochondria from 4 independent experiments. *: P<0.05.

The proteomics approach may not be sensitive enough to find all the lysine residues that can be modulated by lipid overload. Thus, based on their relative in vitro acetylation levels, conserved nature, and locations within the functional domains of Drp1, we selected 10 lysine residues and generated single- or double-point mutations (K to R, which mimics a non-acetylated state without altering the positive charge of the side chain) (Figure 6A). After transfection, wild-type (WT) and mutations of Drp1 proteins had similar expression and acetylation levels in HEK293 cells (Online Figure VI A–B). Palmitate increased the protein levels, acetylation, and oligomerization of WT Drp1 and most of the point mutations, including K75R but not K642R (Figure 6C–E and Online Figure VI C–E), suggesting that K642 may be the residue modified by lipid overload. Since K642 can be acetylated in vivo (Figure 6B) and is highly conserved among dynamin-like GTPases across different species (Online Figure VI F), this residue is likely involved in regulating Drp1 function.

The K631 residue plays a critical role in Drp1 dimerization.28 Indeed, K631R mutation inhibited palmitate-induced Drp1 oligomerization (Figure 6E and Online Figure VI E). The 3D structure of Drp1 suggests that K642 and K631 are located adjacent to each other and near the domain that regulates Drp1 dimerization (Online Figure VI G). Finally, Drp1 K642R prevented mitochondrial fragmentation and attenuated cell death after palmitate incubation in HEK293 cells (Figure 6F and Online Figure VI H). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that K642 is acetylated by lipid overload and may be important for Drp1 activation.

K642R mutation blocked palmitate-induced Drp1 phosphorylation, oligomerization and activity in adult cardiomyocytes.

To explore the pathophysiological significance of Drp1 acetylation at K642 in adult cardiomyocytes, we generated adenovirus containing GFP-tagged WT or K642R mutation. Drp1 expression, acetylation, phosphorylation at S616, and oligomerization were all comparable between WT and K642R mutation, suggesting that K-to-R mutation does not alter the basic features of Drp1 (Online Figure VII). Next, we tested whether Drp1 acetylation at K642 is responsible for increased Drp1 protein levels induced by lipid overload. Cycloheximide (CHX, 25 μg/ml for 24 hr) inhibited protein synthesis and decreased Drp1 protein levels in adult cardiomyocytes. Palmitate incubation prevented the effect of CHX in WT but not K642R Drp1-overexpressing cardiomyocytes (Figure 7A). Thus, Drp1 acetylation at K642 may stabilize Drp1 or prevent its degradation. Palmitate incubation also increased Drp1 acetylation, phosphorylation, and oligomerization in WT but not K642R Drp1-overexpressing cardiomyocytes (Figure 7B–E). Moreover, K642R attenuated palmitate-induced mitochondrial fission in adult cardiomyocytes and in Drp1-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) (Figure 7E–F). Finally, the GTPase activity of K642R was not elevated by palmitate incubation in adult cardiomyocytes (Figure 7G). These results suggest that palmitate acetylates Drp1 at K642 to regulate its protein stability and activity.

Figure 7. Preventing Drp1 acetylation at K642 blocked palmitate-induced Drp1 activation and fission.

A, Western blotting images and summarized data showing the degradation of GFP-tagged Drp1 (WT) or Drp1 K642R mutation (K642R) with or without palmitate and cycloheximide (CHX, 25 μg/ml, 24 hr) incubation. N=5 rats. B-D, Western blotting images and summarized data showing the effects of WT or K642R on palmitate-induced Drp1 acetylation (B), S616 phosphorylation (C), and oligomerization (D). N=5 rats. E, Representative confocal images and summarized data showing GFP puncta and mitochondrial morphology in adult cardiomyocytes overexpressing WT or K642R and in the presence of palmitate. N=763–1221 mitochondria or 20839–39002 GFP puncta in 18–24 cells from 3–4 rats in each group. Scale bars = 20 or 5 μm for the whole cell or enlarged images, respectively. F, Representative confocal images showing mitochondrial morphology in Drp1 knockout (KO) MEF cells overexpressing WT or K642R and in the presence of palmitate. N=16 cells in each group from 3 independent experiments. G, The GTPase activity of Drp1 in adult cardiomyocytes overexpressing WT or K642R. N=3 rats. *: P<0.05.

Drp1 acetylation induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction and cell death through VDAC1.

Excessive activation of Drp1 mediates chronic or acute stress-induced cell death in the heart.20, 21 To determine how Drp1 activation promotes lipid overload-induced cardiomyocyte death, we explored the potential interaction between Drp1 and the mitochondrial outer membrane protein VDAC1, which also regulates apoptosis.34 Co-immunoprecipitation showed that Drp1 interacts with VDAC1 and that HFD enhanced this interaction in the heart (Figure 8A). In cultured adult cardiomyocytes, palmitate also enhanced the interaction between VDAC1 and WT Drp1 but not between VDAC1 and Drp1 K642R (Figure 8B). Moreover, palmitate compromised contraction and prolonged relaxation time course (time from peak to 50% relaxation, T50%) in adult cardiomyocytes and these effects were attenuated by overexpression of Drp1 K642R or treatment with a VDAC1 inhibitor (VBit4, 10 μmol/L, 24 hr) (Figure 8C). Drp1 K642R did not alter cardiomyocyte contractility or relaxation in the absence of palmitate (Online Figure VIII A). Drp1 K642R and VBit4 also blocked palmitate-induced mPTP opening and adult cardiomyocyte death (Figure 8D–E). Abolishment of Drp1 activity through overexpression of a dominant-negative Drp1 mutation (Drp1 K38A) or supplementation with NAD+ (NMN) also rescued palmitate-induced mPTP opening and cell death (Online Figure VIII B–C). Finally, palmitate increased caspase 9 cleavage and LC3II/I ratio in adult cardiomyocytes, which were abolished by Drp1 K642R or VBit4 (Figure 8F). Thus, Drp1 acetylation and VDAC1 activity may contribute to apoptosis and autophagy regulation by palmitate. In summary, these results demonstrate that lipid overload-induced contractile dysfunction and cardiomyocyte death are mediated by Drp1 acetylation, its activity, and VDAC1.

Figure 8. Acetylation at K642 increased Drp1 and VDAC1 interaction and mediated lipid overload-induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction.

A, Western blotting images and summarized data showing Drp1 and VDAC1 interactions in the heart of mice fed different diets for 18 weeks. N=3 rats. B, Western blotting image and summarized data showing the interactions between VDAC1 and WT Drp1 or VDAC1 and Drp1 K642R in adult cardiomyocytes in the presence of palmitate. N=3 rats. C, Representative original or normalized traces (upper) and summarized data (lower) showing the effects of palmitate (0.3 mmol/L, 24 hr) on electric pacing-induced cardiomyocyte contraction (cell shortening) and relaxation (T50%) and with overexpression of K642R or pretreatment with VBit4 (10 μmol/L). N=30–43 cells in each group from 3–4 rats. D-F, Effects of palmitate on mPTP time (D), cell death (E), cleaved caspase 9 (F), and LC3II/I ratios (F) in adult cardiomyocytes and with overexpression of K642R or pretreatment with VBit4. N=3–4 rats. *: P<0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reported a novel mechanism that contributes to lipid overload-induced cardiomyocyte death and heart dysfunction. We found that lipid overload creates an intracellular environment that facilitates acetylation of the fission protein Drp1 at K642 in adult cardiomyocytes in vivo and in vitro. K642 acetylation regulated Drp1 stability, phosphorylation, oligomerization, mitochondrial translocation, and GTPase activity. Excessive Drp1 activation through the above mechanisms induced fission, cardiomyocyte dysfunction, and cell death, contributing to heart dysfunction. These results are the first to show that lipid overload leads to post-translational activation of Drp1 via acetylation in the heart. Based on these findings, targeting Drp1 acetylation may offer a new therapeutic approach for heart dysfunction associated with obesity and type II diabetes. The clinical relevance of these findings was exemplified by increased Drp1 acetylation and activity in the hearts of monkeys fed a HFHC diet.

In this study, we explored how lipid overload regulates the intracellular environment, protein activity, and heart function. Imbalanced intracellular NAD+ and NADH levels are found in pathological conditions, including metabolic syndrome, heart failure, and aging.35, 36 Decreased NAD+ levels and increased protein acetylation are reported in multiple tissues in obesity and diabetes models, including the heart.12, 14, 15, 31 Increased protein acetylation and decreased Sirt3 protein levels are observed in the hearts of obesity and type II diabetic mice.14 However, the exact changes in NAD+, acetyl-CoA, and protein acetylation as well as their interrelationships have not been thoroughly studied in the heart under these conditions.12 Our results depict a pathway that links lipid overload to altered intracellular metabolites and to increased acetylation of the fission protein Drp1. Thus, lipid overload alters the intracellular environment likely via decreased NAD+ generation and increased acetyl-CoA synthesis to modulate the acetylation/de-acetylation balance, protein activity, and eventually cardiomyocyte function and viability in the heart.

Our results also revealed a role of Drp1 in the link between cytosolic stress signals and mitochondrial morphological changes. Mitochondrial morphology is coupled to mitochondrial biogenesis, fitness, and quality control.37 Our results indicate that the interplay between excessive fuel supply and regulators of mitochondrial morphology critically influences cardiomyocyte function and heart disease progression.25 Mitochondrial morphology and dynamics can influence metabolism. For instance, in pancreatic cells, longitudinal or networking mitochondria exhibit increased respiration and energy production, while small and disconnected mitochondria exhibit decreased respiration efficiency and uncoupling.38 Deficiencies of major fission and fusion proteins in the heart cause mitochondrial dysfunction, cardiomyocyte death, heart failure, and lethality.39–41 On the other hand, stresses, such as hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia, can change mitochondrial morphology, most notably inducing fission or fragmentation in multiple tissues and cell types.16, 18 Our findings are consistent with a recent study that showed increased fission and Drp1 activity in the heart upon enhanced fatty acid uptake.18 Although we and others have shown that excessively activated Drp1 causes cardiomyocyte dysfunction and death, endogenous Drp1 may benefit the heart via mitophagy,40 which serves as a mitochondrial quality control mechanism and plays a role in obesity and diabetes.24 Impaired mitophagy increases lipid accumulation, induces mitochondrial dysfunction, and exacerbates HFD-induced heart dysfunction.42 Thus, it is possible that Drp1 is activated during lipid overload to initially facilitate mitophagy, but over time, this activated Drp1 exacerbates cell apoptosis and heart dysfunction.

Drp1 acetylation at K642 is a new post-translational modification, while Drp1 phosphorylation, S-nitrosylation, SUMOylation, O-GlcNAcylation, and ubiquitination are previously reported.25 Previously, it was not known whether Drp1 was acetylated or whether its acetylation level was modulated by substrate metabolism. Since protein acetylation is sensitive to the intracellular redox state,29 Drp1 acetylation may be an early event in Drp1 activation during lipid overload. First, Drp1 acetylation at K642 is required for increased Drp1 phosphorylation at S616, which promotes its mitochondrial translocation and GTPase activity.26 Second, Drp1 oligomerization is attenuated by the non-acetylated K642R mutation. Third, K642R also attenuates the GTPase activity of Drp1. Interestingly, K642 is located within the GTPase effector domain (GED), which regulates Drp1 oligomerization and GTPase activity.43 K642 is also close to K631, a key site for Drp1 dimerization.28 Taken together, these results suggest that K642 acetylation may initiate sequential steps in Drp1 activation. Therefore, targeting Drp1 acetylation could prevent Drp1 overactivation and the cardiac dysfunction associated with obesity and type II diabetes. Several questions, however, remain to be answered. First, how does K642 acetylation modulate Drp1 phosphorylation at S616? Can K642 and K631 synergistically regulate Drp1 oligomerization and GTPase activity? Does K642 acetylation stabilize Drp1 via promotion of its oligomerization or prevention of its proteolysis? Besides Drp1, lipid overload broadly affects protein acetylation and function and may contribute to heart dysfunction through multiple mechanisms, including altered substrate metabolism, mitophagy, and oxidative stress.14, 18, 42 On the other hand, other Drp1 post-translational modifications, such as palmitoylation and glycosylation, may be altered during obesity and/or diabetes and likely play a role in heart dysfunction.

Our finding that Drp1 interacts with VDAC1 to promote cardiomyocyte dysfunction and cell death provides insight into the non-canonical roles of dynamics proteins in the heart.19 Although fission and fusion proteins are abundant in adult hearts, the morphological dynamics of mitochondria in adult hearts are remarkably different than those in most other tissues. Electron microscopic images reveal that mitochondria in adult cardiomyocytes are fragmented and fixed in between myofilaments (Figure 1F).18 Previously, our real time confocal imaging also revealed that fission/fusion and mitochondrial movement are nearly absent in adult hearts and cardiomyocytes. These alterations are in sharp contrast to the constant changes in mitochondrial shape and location in other cell types, including H9C2 cardiomyoblasts.21, 44 Recently, compelling evidence suggests that dynamics proteins play non-canonical roles in cells, including adult cardiomyocytes.45 These non-canonical roles regulate a wide range of mitochondrial and cellular functions, including mitochondria-sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ communication (by Mfn1/2), mitochondrial respiration (by Opa1), mitophagy (by Mfn1/2 and Drp1), and mPTP opening (by Drp1).19 The current study further showed that acetylation influences cardiomyocyte function and viability via promotion of the Drp1-VDAC1 interaction. The way Drp1 acetylation modulates its interaction with VDAC1 and how this interaction regulates mitochondrial morphology, function, and mPTP remain to be determined.

A limitation of this study is that cultured adult cardiomyocytes are quiescent and metabolically very different than cells in beating hearts. For instance, an increased fuel supply can acutely stimulate mitochondrial respiration in cultured cells;42, 44 however, lipid overload may not increase fatty acid oxidation in beating hearts.46, 47 Despite differences in energy metabolism, Drp1 acetylation and activation were observed in hearts in vivo and in cultured cells, suggesting that the two models share the same signaling pathway downstream of lipid overload. In addition, total NAD+ levels in heart tissues are higher than previously reported values (0.2–0.5 mM).48 This discrepancy may be caused by different experimental conditions or methods. Nevertheless, cytosolic free NAD+ levels, which are more relevant to sirtuins activity and protein acetylation regulation, were likely lower in heart tissues and cultured cells in the presence of lipid overload. Another issue is the translational potential of these findings. Since obtaining heart tissues from patients with obesity and diabetes-associated heart failure is very difficult, our results from non-human primate models suggest that Drp1 regulation may be universal and may be present in patient hearts. Although contractile functions (e.g., echocardiography) were not measured in the monkey hearts, clear signs of myocardial damage justify this as a relevant disease model.

In summary, we showed that lipid overload modulates intracellular redox environment and Drp1 acetylation at a specific lysine residue (K642), which initiates sequential processes of Drp1 activation. This could be a class effect of saturated and unsaturated long-chain fatty acids. The excessively activated Drp1 increases mitochondrial fission and interacts with VDAC1 to induce cardiomyocyte death. Our results suggest that targeting the intracellular redox environment, Drp1 acetylation, Drp1 overactivation, or Drp1-interacting proteins may offer a promising approach to ameliorate the heart dysfunction associated with obesity and type II diabetes.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Lipid overload-induced heart damage is associated with mitochondrial and cardiomyocyte dysfunction.

In tissues from obesity and diabetes patients or animal models, NAD+ levels are decreased and protein acetylation is increased.

The fission protein Drp1 modulates acute and chronic heart dysfunction via canonical and non-canonical mechanisms.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Lipid overload decreases NAD+ and increases Drp1 acetylation at lysine 642 in the heart.

Acetylation activates Drp1 through promoting its phosphorylation, oligomerization, GTPase activity, and mitochondrial translocation.

Excessively activated Drp1 induces fission, cardiomyocyte dysfunction, and cell death via binding VDAC1.

Targeting NAD+, Drp1 acetylation/activation, or VDAC1 prevents lipid overload-induced cardiomyocyte death.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Rong Tian and E. Dale Abel for constructive suggestions. We thank Dr. Yi Yang for providing the SoNar indicator. We thank Yan Lu, Haodong Xu, Matthew A. Walker, Arianne Caudal and Julia Ritterhoff for technical support. The University of Washington (UW) Core for Vision Research (NEI P30EY001730) conducted electron microscopy analysis. The Cell Function and Analysis Core at the Diabetes Research Center of UW assisted with pyruvate and lactate measurements (P30DK017047). Drp1 K38A and GFP-Drp1 constructs are provided by Drs. Yisang Yoon (Augusta University) and Suzanne Hoppins (UW), respectively. The VBit4 is from Dr. Varda Shoshan-Barmatz (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel). We thank Ms. Zitong Wang for English editing.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was partially supported by NIH (HL114760 and HL110349 to W. Wang, HL137266 to S. S. Sheu and W. Wang, and NIH HL093671 and HL142864 to S. S. Sheu), American Heart Association (18EIA33900041 to W. Wang and 19CDA34660311 to H. Zhang), and NIA Intramural Research Program (M. Wang and E. G. Lakatta).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-coenzyme A

- BCAA

Branched-chain amino acids

- BNP

Brain natriuretic peptide

- BW

Body weigh

- CD

Control diet

- CHX

Cycloheximide

- Drp1

Dynamin related protein 1

- FS

Fractional shortening

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- GTT

Glucose tolerance test

- HADHA

Hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase/3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase/enoyl-CoA hydratase, alpha subunit

- HFD

High fat diet

- HFHC

High fat and high cholesterol diet

- HW

Heart weight

- KHB

Krebs-Henseleit Buffer

- LC-MS

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- LFWT

Left ventricular free wall thickness

- LV

Left ventricle

- MEF

Mouse embryonic fibroblast

- Mfn1

Mitofusin1

- mPTP

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- NAD+

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized)

- NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced)

- NAMPT

Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase

- NMN

Nicotinamide mononucleotide

- NR

Nicotinamide ribose chloride

- OD

Optical density

- Opa1

Optic atrophy 1

- RC

Regular rodent chow

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- TL

Tibia length

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VDAC1

Voltage-dependent anion channel 1

- VW

Ventricle weight

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ortega FB, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Obesity and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:1752–1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman JA, Creager MA. Vascular complications of diabetes. Circ Res. 2016;118:1771–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenny HC, Abel ED. Heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circ Res. 2019;124:121–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reaven GM, Lithell H, Landsberg L. Hypertension and associated metabolic abnormalities--the role of insulin resistance and the sympathoadrenal system. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:374–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wende AR, Abel ED. Lipotoxicity in the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:311–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, Keung W, Samokhvalov V, Wang W, Lopaschuk GD. Role of fatty acid uptake and fatty acid beta-oxidation in mediating insulin resistance in heart and skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodpaster BH, Sparks LM. Metabolic flexibility in health and disease. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1027–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, Woodlief TL, Kane DA, Lin CT, Price JW 3rd, Kang L, Rabinovitch PS, Szeto HH, Houmard JA, Cortright RN, Wasserman DH, Neufer PD. Mitochondrial h2o2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:573–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park TS, Hu Y, Noh HL, Drosatos K, Okajima K, Buchanan J, Tuinei J, Homma S, Jiang XC, Abel ED, Goldberg IJ. Ceramide is a cardiotoxin in lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Journal of lipid research. 2008;49:2101–2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy, causes and effects. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2010;11:31–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma K Mitochondrial hormesis and diabetic complications. Diabetes. 2015;64:663–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berthiaume JM, Kurdys JG, Muntean DM, Rosca MG. Mitochondrial nad(+)/nadh redox state and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2019;30:375–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vazquez EJ, Berthiaume JM, Kamath V, Achike O, Buchanan E, Montano MM, Chandler MP, Miyagi M, Rosca MG. Mitochondrial complex i defect and increased fatty acid oxidation enhance protein lysine acetylation in the diabetic heart. Cardiovascular research. 2015;107:453–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alrob OA, Sankaralingam S, Ma C, Wagg CS, Fillmore N, Jaswal JS, Sack MN, Lehner R, Gupta MP, Michelakis ED, Padwal RS, Johnstone DE, Sharma AM, Lopaschuk GD. Obesity-induced lysine acetylation increases cardiac fatty acid oxidation and impairs insulin signalling. Cardiovascular research. 2014;103:485–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraus D, Yang Q, Kong D, Banks AS, Zhang L, Rodgers JT, Pirinen E, Pulinilkunnil TC, Gong F, Wang YC, Cen Y, Sauve AA, Asara JM, Peroni OD, Monia BP, Bhanot S, Alhonen L, Puigserver P, Kahn BB. Nicotinamide n-methyltransferase knockdown protects against diet-induced obesity. Nature. 2014;508:258–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu T, Sheu SS, Robotham JL, Yoon Y. Mitochondrial fission mediates high glucose-induced cell death through elevated production of reactive oxygen species. Cardiovascular research. 2008;79:341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuzmicic J, Parra V, Verdejo HE, Lopez-Crisosto C, Chiong M, Garcia L, Jensen MD, Bernlohr DA, Castro PF, Lavandero S. Trimetazidine prevents palmitate-induced mitochondrial fission and dysfunction in cultured cardiomyocytes. Biochemical pharmacology. 2014;91:323–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsushima K, Bugger H, Wende AR, Soto J, Jenson GA, Tor AR, McGlauflin R, Kenny HC, Zhang Y, Souvenir R, Hu XX, Sloan CL, Pereira RO, Lira VA, Spitzer KW, Sharp TL, Shoghi KI, Sparagna GC, Rog-Zielinska EA, Kohl P, Khalimonchuk O, Schaffer JE, Abel ED. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in lipotoxic hearts induce post-translational modifications of akap121, drp1, and opa1 that promote mitochondrial fission. Circ Res. 2018;122:58–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang W, Fernandez-Sanz C, Sheu SS. Regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics by the non-canonical roles of mitochondrial dynamics proteins in the heart. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease 2018;1864:1991–2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong SB, Subrayan S, Lim SY, Yellon DM, Davidson SM, Hausenloy DJ. Inhibiting mitochondrial fission protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2010;121:2012–2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu S, Wang P, Zhang H, Gong G, Gutierrez Cortes N, Zhu W, Yoon Y, Tian R, Wang W. Camkii induces permeability transition through drp1 phosphorylation during chronic beta-ar stimulation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dyntar D, Eppenberger-Eberhardt M, Maedler K, Pruschy M, Eppenberger HM, Spinas GA, Donath MY. Glucose and palmitic acid induce degeneration of myofibrils and modulate apoptosis in rat adult cardiomyocytes. Diabetes. 2001;50:2105–2113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sparagna GC, Hickson-Bick DL, Buja LM, McMillin JB. A metabolic role for mitochondria in palmitate-induced cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2124–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Sowers JR, Ren J. Targeting autophagy in obesity: From pathophysiology to management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:356–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall AR, Burke N, Dongworth RK, Hausenloy DJ. Mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins: Novel therapeutic targets for combating cardiovascular disease. British journal of pharmacology. 2014;171:1890–1906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi X, Disatnik MH, Shen N, Sobel RA, Mochly-Rosen D. Aberrant mitochondrial fission in neurons induced by protein kinase c{delta} under oxidative stress conditions in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:256–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, Martins de Brito O, Chang CR, Blackstone C, Bernardi P, Scorrano L. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of drp1 to mitochondria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:15803–15808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frohlich C, Grabiger S, Schwefel D, Faelber K, Rosenbaum E, Mears J, Rocks O, Daumke O. Structural insights into oligomerization and mitochondrial remodelling of dynamin 1-like protein. The EMBO journal. 2013;32:1280–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menzies KJ, Zhang H, Katsyuba E, Auwerx J. Protein acetylation in metabolism - metabolites and cofactors. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:43–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson DH, Lund P, Krebs HA. The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of rat liver. Biochem J. 1967;103:514–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshino J, Mills KF, Yoon MJ, Imai S. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, a key nad(+) intermediate, treats the pathophysiology of diet- and age-induced diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 2011;14:528–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y, Hu Q, Cheng F, Su N, Wang A, Zou Y, Hu H, Chen X, Zhou HM, Huang X, Yang K, Zhu Q, Wang X, Yi J, Zhu L, Qian X, Chen L, Tang Y, Loscalzo J, Yang Y. Sonar, a highly responsive nad+/nadh sensor, allows high-throughput metabolic screening of anti-tumor agents. Cell Metab. 2015;21:777–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshino J, Baur JA, Imai SI. Nad(+) intermediates: The biology and therapeutic potential of nmn and nr. Cell Metab. 2018;27:513–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoshan-Barmatz V, De S, Meir A. The mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel 1, ca(2+) transport, apoptosis, and their regulation. Front Oncol. 2017;7:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verdin E Nad(+) in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science. 2015;350:1208–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CF, Chavez JD, Garcia-Menendez L, Choi Y, Roe ND, Chiao YA, Edgar JS, Goo YA, Goodlett DR, Bruce JE, Tian R. Normalization of nad+ redox balance as a therapy for heart failure. Circulation. 2016;134:883–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan DC. Fusion and fission: Interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:265–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liesa M, Shirihai OS. Mitochondrial dynamics in the regulation of nutrient utilization and energy expenditure. Cell Metab. 2013;17:491–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wai T, Garcia-Prieto J, Baker MJ, Merkwirth C, Benit P, Rustin P, Ruperez FJ, Barbas C, Ibanez B, Langer T. Imbalanced opa1 processing and mitochondrial fragmentation cause heart failure in mice. Science. 2015;350:aad0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shirakabe A, Zhai P, Ikeda Y, Saito T, Maejima Y, Hsu CP, Nomura M, Egashira K, Levine B, Sadoshima J. Drp1-dependent mitochondrial autophagy plays a protective role against pressure overload-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and heart failure. Circulation. 2016;133:1249–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorn GW 2nd, Song M, Walsh K. Functional implications of mitofusin 2-mediated mitochondrial-sr tethering. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;78:123–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong M, Saito T, Zhai P, Oka SI, Mizushima W, Nakamura M, Ikeda S, Shirakabe A, Sadoshima J. Mitophagy is essential for maintaining cardiac function during high fat diet-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sever S, Muhlberg AB, Schmid SL. Impairment of dynamin’s gap domain stimulates receptor-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 1999;398:481–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H, Wang P, Bisetto S, Yoon Y, Chen Q, Sheu SS, Wang W. A novel fission-independent role of dynamin-related protein 1 in cardiac mitochondrial respiration. Cardiovascular research. 2017;113:160–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song M, Dorn GW 2nd. Mitoconfusion: Noncanonical functioning of dynamism factors in static mitochondria of the heart. Cell Metab. 2015;21:195–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldenberg JR, Carley AN, Ji R, Zhang X, Fasano M, Schulze PC, Lewandowski ED. Preservation of acyl coenzyme a attenuates pathological and metabolic cardiac remodeling through selective lipid trafficking. Circulation. 2019;139:2765–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldenberg JR, Wang X, Lewandowski ED. Acyl coa synthetase-1 links facilitated long chain fatty acid uptake to intracellular metabolic trafficking differently in hearts of male versus female mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;94:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canto C, Auwerx J. Nad+ as a signaling molecule modulating metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:291–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.