Abstract

In 2011, genome wide association studies implicated a polymorphism near CD33 as a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. This finding sparked interest in this member of the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectin family which is linked to innate immunity. Subsequent studies found that CD33 is expressed in microglia in the brain and then investigated the molecular mechanism underlying the CD33 genetic association with Alzheimer’s disease. The allele that protects from Alzheimer’s disease acts predominately to increase a CD33 isoform lacking exon 2 at the expense of the prototypic, full-length CD33 that contains exon 2. Since this exon encodes the sialic acid ligand binding domain, the finding that loss of exon 2 was associated with decreased Alzheimer’s disease risk was interpreted as meaning that a decrease in functional CD33 and its associated immune suppression was protective from Alzheimer’s disease. However, this interpretation may need to be reconsidered given current findings that a genetic deletion which abrogates CD33 is not associated with Alzheimer’s disease risk. Therefore, integrating currently available findings leads us to propose a model wherein the CD33 isoform lacking the ligand binding domain represents a gain of function variant that reduces Alzheimer’s disease risk.

Keywords: Molecular genetics, Inflammation, RNA splicing, Alzheimer’s disease, CD33, SIGLEC, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif

Introduction

Recent genetic studies have identified multiple Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk variants, including many that mark genes expressed specifically or selectively in microglia in the brain [1–3]. Because an understanding of the mechanisms whereby these variants impact AD may lead to pharmacologic agents that reduce AD risk, these studies have sparked intense interest in the role of inflammation in this disease. Several recent reviews have addressed these genetic factors and their actions in AD overall [4–6]. Here, we will focus on the genetics and actions of one of these risk factors, CD33.

CD33 Genetics and AD risk

In 2011, two genome wide association studies (GWAS) identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) located upstream of CD33, rs3865444, as associated with AD risk [1, 2]. Naj et al, using AD Genetic Consortium samples, found a robust association between reduced AD risk and the minor allele of rs3865444 that reached genome wide significance when meta-analyzed with subjects from the three other consortia that would later form the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP) [2]. The complementary study by Hollingworth et al. was supportive of an association between rs3865444 and AD risk although the finding did not reach genome wide significance (p=2×10−4) [1]. When data from both studies were combined in a meta-analysis to generate an overall cohort of 18,762 AD individuals and 29,827 non-AD individuals, the association between rs3865444 and AD was strong, with a p value of 1.6×10−9 and an odds ratio (OR) of 0.91 (95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.88–0.93) [1, 2]. These studies focused attention on CD33. A prior AD genetic study had also identified a SNP near CD33, rs3826656, but this finding was not replicated in subsequent reports and rs3826656 is not in robust linkage disequilibrium (co-inherited) with rs3865444 [7]. In 2013, the IGAP studied an additional 8,572 AD and 11,312 non-AD individuals, and, somewhat surprisingly, rs3865444 was not associated with AD (OR=0.99, p=0.69) [3]. The reason for the lack of association was not clear. The study was consistent with prior studies in terms of the cohort being European-based and the analytical approaches used [1, 2]. A meta-analysis of the overall dataset of 74,046 individuals found that rs3865444 just missed genome wide significance with an OR of 0.94 (CI of 0.91–0.96) and p=3.0×10−6 [3]. Similar findings for the rs3865444 association with AD were reported in a recent update to the IGAP study (OR = 0.92 (95% CI: 0.90–0.95)), p=3.9×10−7 [8]. Quite recently, Jansen et al. reported on a very large-scale meta-analysis which incorporated an unconventional AD-by-proxy phenotype to gain statistical power. In this analysis, individuals that reported a parent with AD were considered to be AD risk carriers and hence scored as AD. This study totaled 71,880 AD samples and 383,378 non-AD samples. Although subjects overlapped with IGAP, this study reconfirmed genome wide significance for the rs3865444 association with AD (p = 6.3×10−9) [3, 9]. In summary, currently available, very large studies support an association between rs3865444 and AD risk. The reason for the inconsistent association in some cohorts could reflect statistical power, variation in AD diagnostic accuracy or cohort risk, or, conceivably, inconsistent linkage disequilibrium between rs3865444 and the functional CD33 SNP, or cohort variations in the allele frequency of SNPs in CD33-related genes that modulate the rs3865444 association with AD risk.

CD33 as a SIGLEC family member

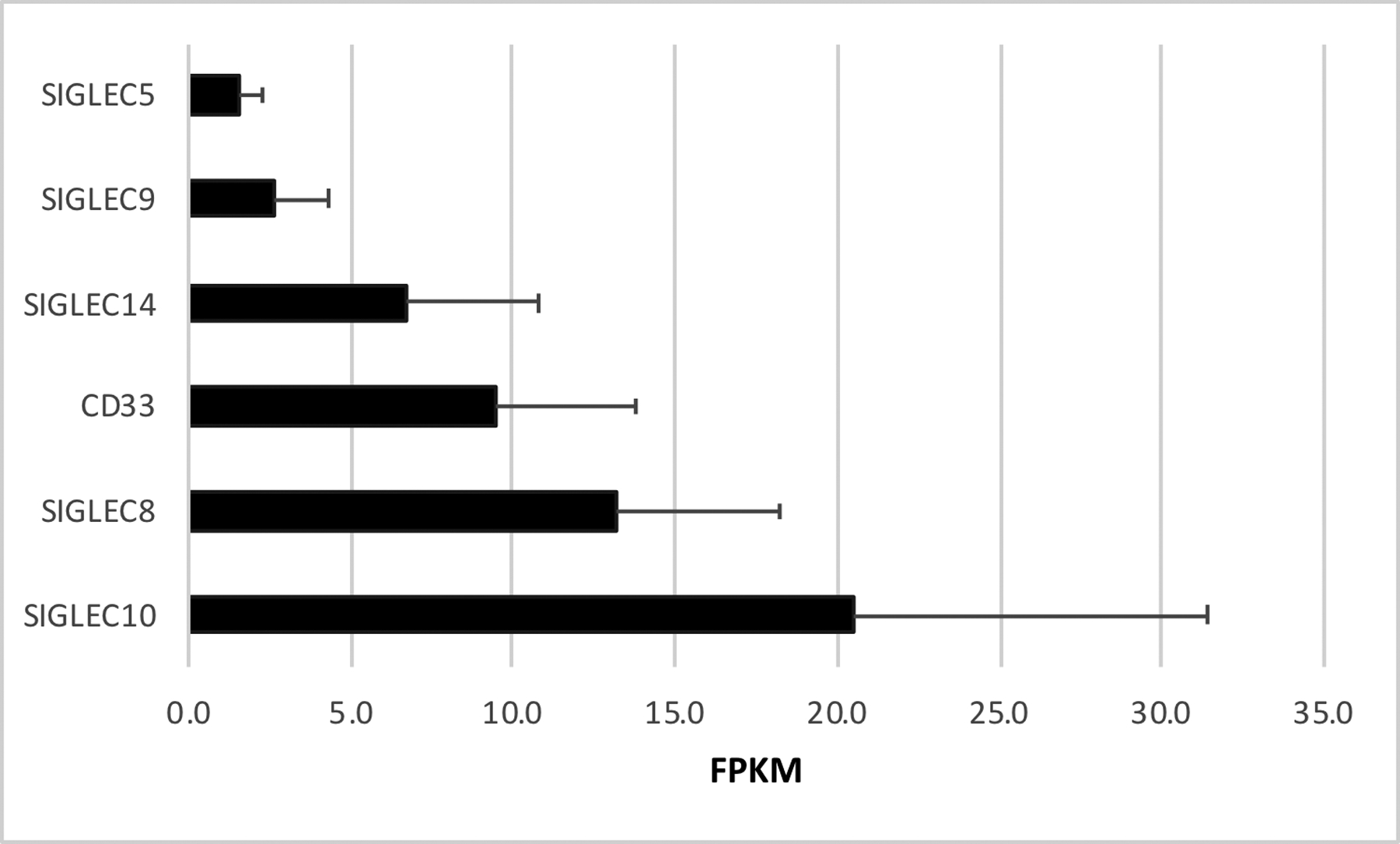

Since CD33 is a member of the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectin (SIGLEC) family, genetic variants in other family members could compensate for or enhance the protective association between the rs3865444 minor allele and AD. The human SIGLEC family consists of the CD33-related SIGLECs (CD33, SIGLEC 5 through 12, 14 and 16), which are rapidly evolving and poorly conserved between species, as well as four SIGLECs that are relatively well conserved between species (Sialoadhesin (SIGLEC1), CD22 (SIGLEC2), myelin-associated glycoprotein (SIGLEC4) and SIGLEC15) [10]. Examination of RNAseq results suggests that CD33-related SIGLECs are the primary SIGLECs expressed in microglia in the human brain (Figure 1). Overall, SIGLEC10 and SIGLEC8 appear to be expressed at higher levels than CD33 while multiple CD33-related SIGLECs are expressed at lower levels. Hence, although only CD33 has been associated with AD risk, CD33 may not be the predominant SIGLEC in human microglia.

Figure 1: SIGLEC Expression in Human Microglia.

SIGLECs with microglial expression greater than 1 FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) are shown. Additional CD33-related SIGLECs expressed in the human brain include SIGLEC7 (0.9 FPKM), SIGLEC16 (0.8 FPKM), SIGLEC11 (0.4 FPKM) and SIGLEC12 (0.2 FPKM). Non-CD33-related SIGLECs with microglial expression include SIGLEC1 (0.5 FPKM) and CD22 (0.2 FPKM). Two SIGLECs expressed predominantly in oligodendrocytes include Myelin Associated Glycoprotein (SIGLEC4) at 1.5 FPKM, and CD22 (SIGLEC2) at 3.7 FPKM are not shown. These data (mean±SD, n=3) are derived from http://web.stanford.edu/group/barres_lab/brainseq2/brainseq2.html [77]. Other microglial RNAseq studies report similar SIGLEC expression profiles [78].

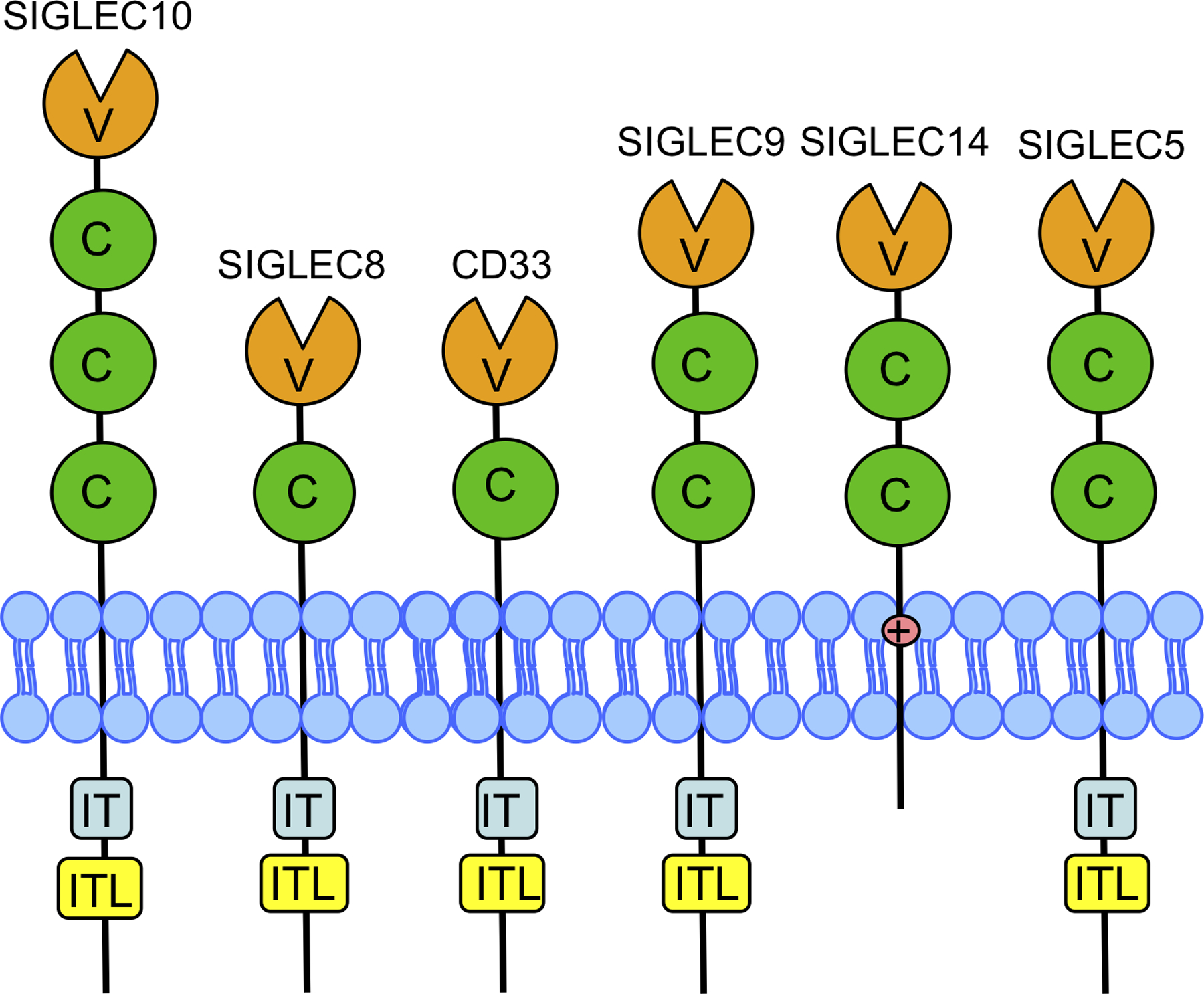

SIGLEC family members share three primary hallmarks, suggesting the possibility of functional redundancy. The first hallmark is an amino-terminal IgV domain that mediates ligand binding (Figure 2). As indicated by the SIGLEC acronym, the primary SIGLEC ligand is a sialic acid, which is a 9-carbon sugar abundantly found in the ganglioside subclass of glycosphingolipids and as a common post-translational protein modification. Sialylated glycoproteins and gangliosides are oftentimes especially abundant in pathophysiologic conditions such as cancer and inflammation, including AD amyloid plaques; their binding to inhibitory microglial SIGLECs has been suggested to inhibit plaque clearance [11]. Within the IgV domain, an arginine that is critical for sialic acid binding is also well-conserved in functional SIGLECs, being present at position 119 in CD33 [12].

Figure 2. Structures of SIGLEC Family Members Expressed in Human Brain Microglia.

SIGLECs expressed at >1 FPKM in microglia are depicted. The IgV (V) domain is amino-terminal while the IgC2 (C) domains are proximal to the membrane. While most brain SIGLECs contain an ITIM (IT) or ITIM-like domain (ITL), SIGLEC14 lacks these motifs and instead has a lysine in the transmembrane domain that is used to signal to DAP12 [25].

The second SIGLEC hallmark is one or more conserved IgC2 domains, which provide a foundation for the ligand binding domain and may modulate ligand binding. The variable number of IgC2 domains has been proposed to impact whether the SIGLEC binds sialic acids in cis, i.e., neighboring glycoproteins on the same cell, or in trans, i.e., sialic acid ligands in the extracellular matrix or on adjacent cells by varying the position of the IgV binding domain closer or further from the cell membrane [13]. The third SIGLEC hallmark is an immunomodulatory motif. The CD33-related SIGLECs generally contain a cytosolic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) proximal to the membrane and an ITIM-like sequence near their carboxyl terminus. Of the CD33-related SIGLECS, SIGLEC14 and SIGLEC16 lack this domain and instead have a positively charged amino acid in their transmembrane domain (Figure 2). This charged amino acid is critical for signaling to adaptor proteins, such as DAP12, which results in activation of DAP12’s immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM).

Considering that CD33 is not the most abundant SIGLEC in microglia, and that SIGLECs show some functional redundancy [14], the finding that CD33 is the only SIGLEC with a SNP that is associated with AD at a genome wide level of significance has two interpretations. First, CD33 may modulate AD risk via a mechanism unique to CD33. Second, CD33 may be the only SIGLEC with a genetic variant that alters its function. Considering the latter, a SIGLEC9 polymorphism, rs2075803, has been associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes including exacerbation frequency in a candidate gene study [15]. Although rs2075803 was not significantly associated with AD at genome wide significance in the largest AD GWAS recently published by Jansen et al., this SNP was in summary data included in the supplement and had a modest association with AD (uncorrected p value p=0.006) [9]. Interestingly, SIGLEC14 has undergone genetic deletion in 10–60% of humans, depending on race. This deletion has been associated with risk for infection [16, 17] but apparently has not been captured directly in genome wide association studies. However, a recent GWAS of the human plasma proteome found that rs1106476 is strongly associated with reduced SIGLEC14 plasma levels (p=2.2×10−309) and this SNP is also nominally associated with an increase in AD risk (p=0.028) [9]. This correlation is consistent with the concept that a decrease in a SIGLEC that acts through an ITAM will increase AD risk. In summary, further work is needed to discern whether CD33 has unique properties, or if a robust targeted genetic evaluation of SIGLECs and AD risk will reveal additional SIGLEC variants that are consistently and significantly associated with AD.

A prevailing concept is that SIGLECs are activated by “self-associated molecular patterns,” or SAMPs, to signal through their ITIM to induce immunosuppression ([18], reviewed in [19, 20]). Briefly, SAMPs including specific glycosylation patterns, i.e. sialic acid linkages, provide a self-recognition signal to suppress innate immune cells, much in the way that pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or “disease-associated molecular patterns” (DAMPs) activate innate immune cells. This contact-dependent inhibition is thought to provide self-nonself discrimination in cells which do not undergo a selection process. Not surprisingly, pathogens have evolved to mimic this by expressing or presenting on their surface SIGLEC ligands and thereby suppress the immune response. For example, sialic acids on group B Streptococcus bind to Siglec9 on neutrophils to inhibit their activation and thereby increase bacterial survival [21]. Perhaps in response to these pathogen ligands, the CD33-related SIGLEC family members have undergone rapid evolution ([14, 22], reviewed in [23]). This SIGLEC evolution is reflected by several observations. First, the gene family has proliferated, with some 15 SIGLEC members in humans, 11 of which are CD33-related SIGLECs. Second, inter-species comparisons show evolutionary divergence, noting that CD33-related SIGLECs in particular show primary sequence divergence, exon shuffling, and differences in gene number, e.g., mice have nine SIGLECs, five of which are CD33-related [22, 24]. Third, some SIGLECs have been neutralized by conversion of their ITIM to an ITAM, by loss of the IgV arginine that is critical for sialic acid ligand binding or by gene deletion, e.g., humans lack SIGLEC13 which is present in chimpanzees [22]. SIGLEC neutralization through loss of the critical arginine is found more commonly in non-human primates than in humans [14]. SIGLEC neutralization by conversion to an immune activator is shown robustly by considering SIGLEC5 and SIGLEC14 ([25], Figure 2). These two SIGLECs are adjacent on chromosome 19 and represent a recent gene duplication. Their amino terminal IgV domains are nearly identical, suggesting that these two SIGLECs bind similar ligands. However, the carboxyl termini of SIGLEC5 and SIGLEC14 differ dramatically. SIGLEC5 signals via its ITIM to immunosuppress while SIGLEC14 signals via an intramembranous arginine to DAP12, causing immune activation via its ITAM [25]. In situations where the two are co-expressed such as in myeloid cells, SIGLEC14 appears to counteract the effects of SIGLEC5 on immune function [25]. SIGLEC11 and SIGLEC16 reflect a similar gene duplication wherein the ITIM of SIGLEC11 is countered by the ITAM of SIGLEC16 [26]. Another type of evolutionary divergence is suggested by comparing human CD33 and murine Cd33. Murine Cd33 lacks the typical ITIM proximal to the membrane, retaining only the ITIM-like domain near the carboxyl terminus. However, Cd33 has evolved to include a lysine within its transmembrane domain that is reminiscent of SIGLEC14 and its use of DAP12 to activate immune cells. This suggests that murine Cd33 may not accurately reflect the actions of human CD33 such that a CD33 transgenic mouse may be necessary to capture the impact of CD33 in vivo. Overall, these findings are consistent with SIGLECs serving to modulate innate immunity, leading to evolutionary pressure that results in inter-species variability in CD33 function as well as SIGLEC function in general [27, 28].

SIGLEC ITIM Signaling

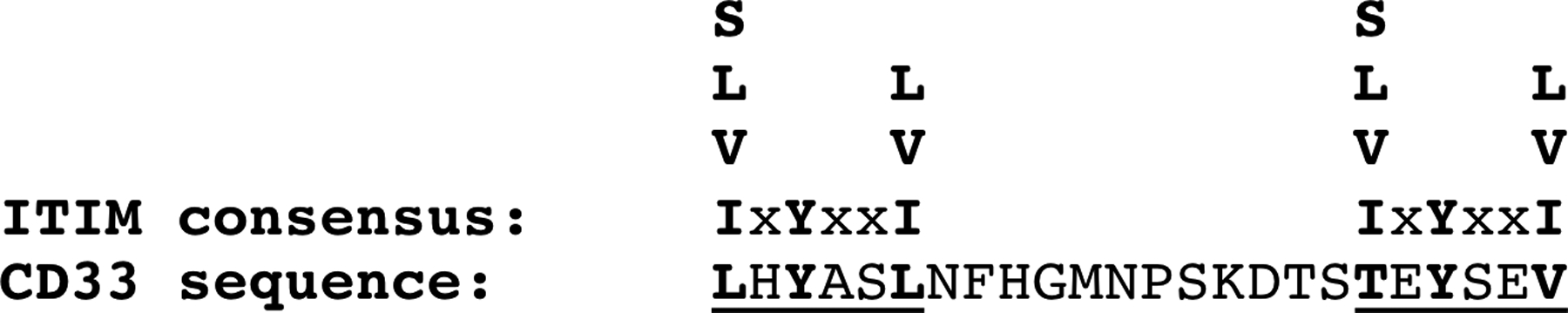

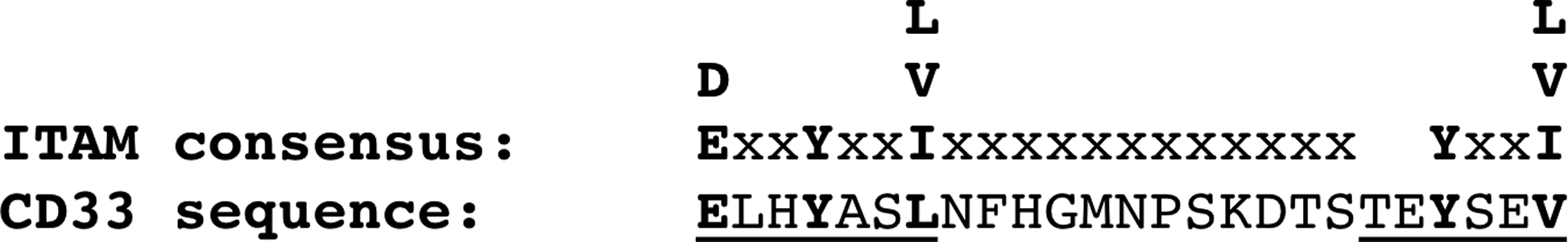

Most brain SIGLECs, including CD33, have an ITIM proximal to the membrane, a 6–14 amino acid spacer, and then an ITIM-like domain near their carboxyl terminus (Figure 2). The relevant CD33 sequences, relative to the prototypic ITIM consensus sequence [29], are shown in Figure 3. Antibodies, used as surrogate ligands, induce SIGLEC clustering, Src family kinase recruitment, and subsequent phosphorylation of the tyrosine in the membrane proximal ITIM followed by the membrane distal ITIM-like domain [30–32]. This clustering likely occurs in lipid rafts, where Src family kinases tend to localize due to their fatty acid lipid anchor [30, 32, 33]. Phosphorylation of the SIGLEC ITIM creates a binding site for the SH2- containing tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1and SHP-2 [12, 30]. The downstream targets of these phosphatases are multiple and include Syk, as well as scaffolding proteins such as BLNK that serve as a bridge between Syk and downstream signaling pathways [12, 34, 35]. CD33 ITIM phosphorylation also attracts proteins to promote CD33 degradation. Two members of the E3 ligase protein family, the suppressor of cytokine signaling, SOCS3, as well as Cbl, have been implicated in ubiquitination, internalization, and subsequent degradation of activated CD33 [31, 36]. SOCS proteins are upregulated by cytokines during inflammatory responses, suggesting the possibility that inflammation in AD may lead to lower CD33 levels. In summary, ligand binding to CD33 promotes receptor clustering, ITIM phosphorylation, localized tyrosine phosphatase activation and CD33 internalization and eventual degradation. The overall impact is typically a reduction in immune cell activation ([37, 38] reviewed in [39]). Of note, synthetic high affinity SIGLEC ligands have also been shown to induce inhibitory signaling via specific SIGLECs, including CD33 [40].

Figure 3. CD33 ITIM and ITIM-like Sequences Aligned to Consensus ITIM sequence.

The CD33 ITIM and ITIM-like sequences (underlined) are shown relative to the ITIM consensus sequence of S/L/V/IxYxxL/V/I. Note that the CD33 ITIM-like sequence begins with a threonine, as opposed to the consequence S/L/V/I, and hence is relatively well-conserved with the consensus. The spacer between the ITIM and ITIM-like sequence in CD33 is 12 amino acids.

Microglial homeostasis: balance of ITIM and ITAM actions

Microglia function appears to be regulated by a homeostatic balance between ITIM and ITAM signaling (reviewed in [41]). DAP12 is a prototypic ITAM family member and serves as a co-receptor for multiple cell surface receptors, including SIGLEC14 [25], and TREM2, which has been robustly associated with AD risk by genetics (reviewed in [41–44]). As noted above, signaling from the receptor to DAP12 is mediated by a positively charged amino acid in the receptor transmembrane domain. In a process similar to SIGLEC activation, receptor clustering leads to DAP12 clustering, which attracts a Src kinase family member to phosphorylate the tyrosines within the DAP12 ITAM. The ITAM consensus sequence is similar to that of two ITIMs, bridged by a spacer domain, i.e., D/ExxYxxL/V/Ix6–12xYxxL/V/I [45–49]. Robust high avidity TREM2 activators, such as TREM2 antibodies, induce phosphorylation of both tyrosines in the DAP12 ITAM. This in turn attracts Syk, which has two SH2 domains. Engagement of both Syk SH2 domains with the two phosphorylated tyrosines in the DAP12 ITAM causes the amino-terminal Syk SH2 domain to move away from its inhibitory position in the kinase, thereby activating Syk. Hence, Syk is activated at sites of DAP12 clustering, leading to the recruitment of additional proteins, including scaffolding proteins such as BLNK, and downstream effector enzymes including PI3-kinase and PLC-γ(reviewed in [42–44]).

Interestingly, less robust, lower avidity TREM2 ligands result in phosphorylation of a single tyrosine within the ITAM. This then attracts SHP-1and/or SHIP1, both of which bind the ITAM via their SH2 domains, behaving as though the ITAM was an ITIM [50–53]. As noted above, SHP-1 is a phosphatase that inhibits Syk signaling. In addition, SHIP1, which is also linked to AD risk by genetics [3, 9], is a lipid phosphatase, hydrolyzing the 5’ phosphate from phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate. Hence, SHIP1 inhibits PI3 kinase, which is downstream in the DAP12 ITAM pathway [52]. In summary, low avidity ligands in an ITAM pathway lead to immune suppression by causing ITAM mono-phosphorylation, resulting in ITIM-like activity by attracting SHP-1and/or SHIP1. High avidity ligands induce immune activation by causing phosphorylation of both tyrosines within the ITAM to attract Syk. The concept of immune regulation by ITIM/ITAM counterbalancing in this manner has been demonstrated in some systems (reviewed in [49, 54]) but has not yet been demonstrated directly in microglia.

Molecular genetics of CD33 in AD

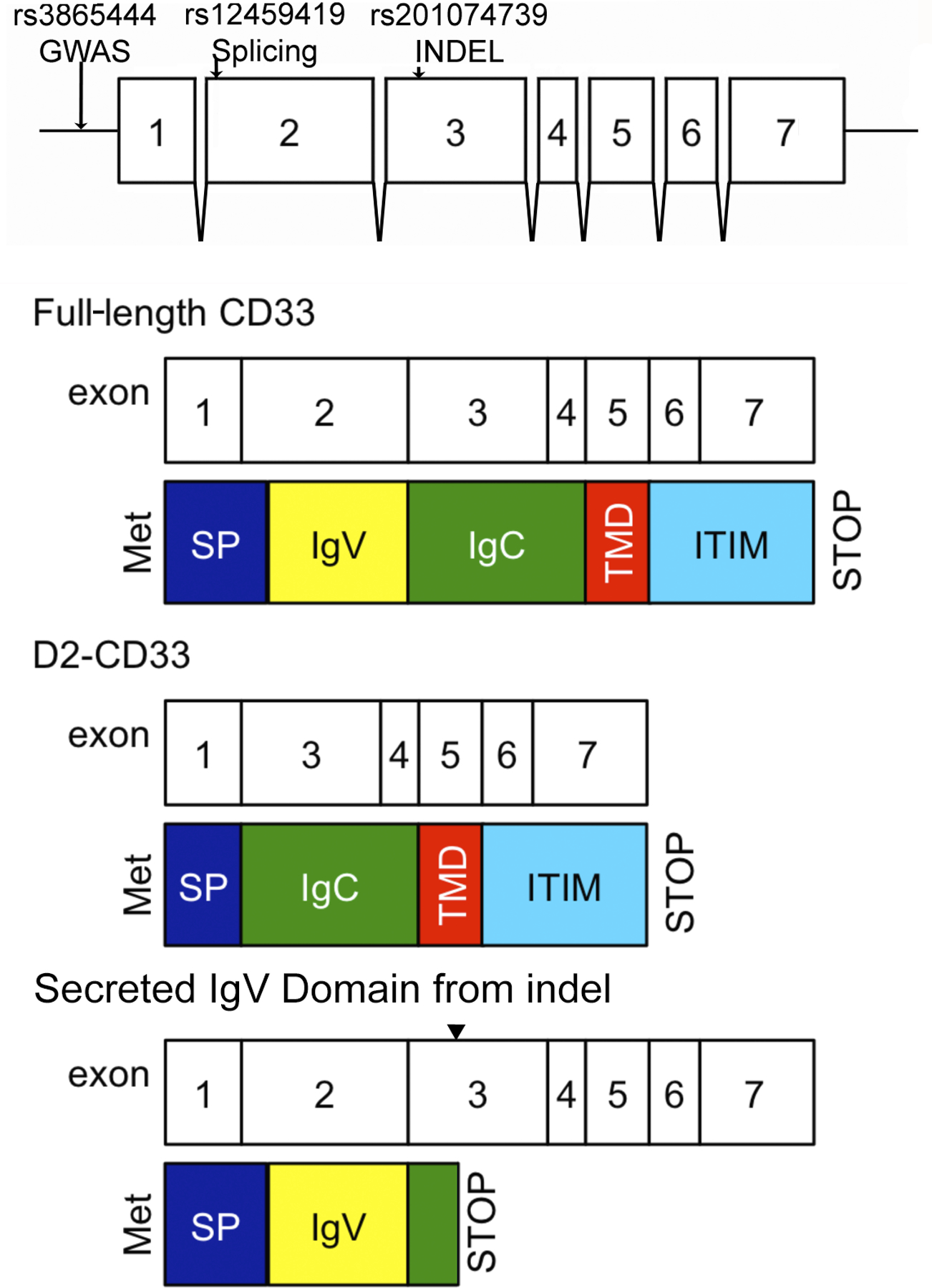

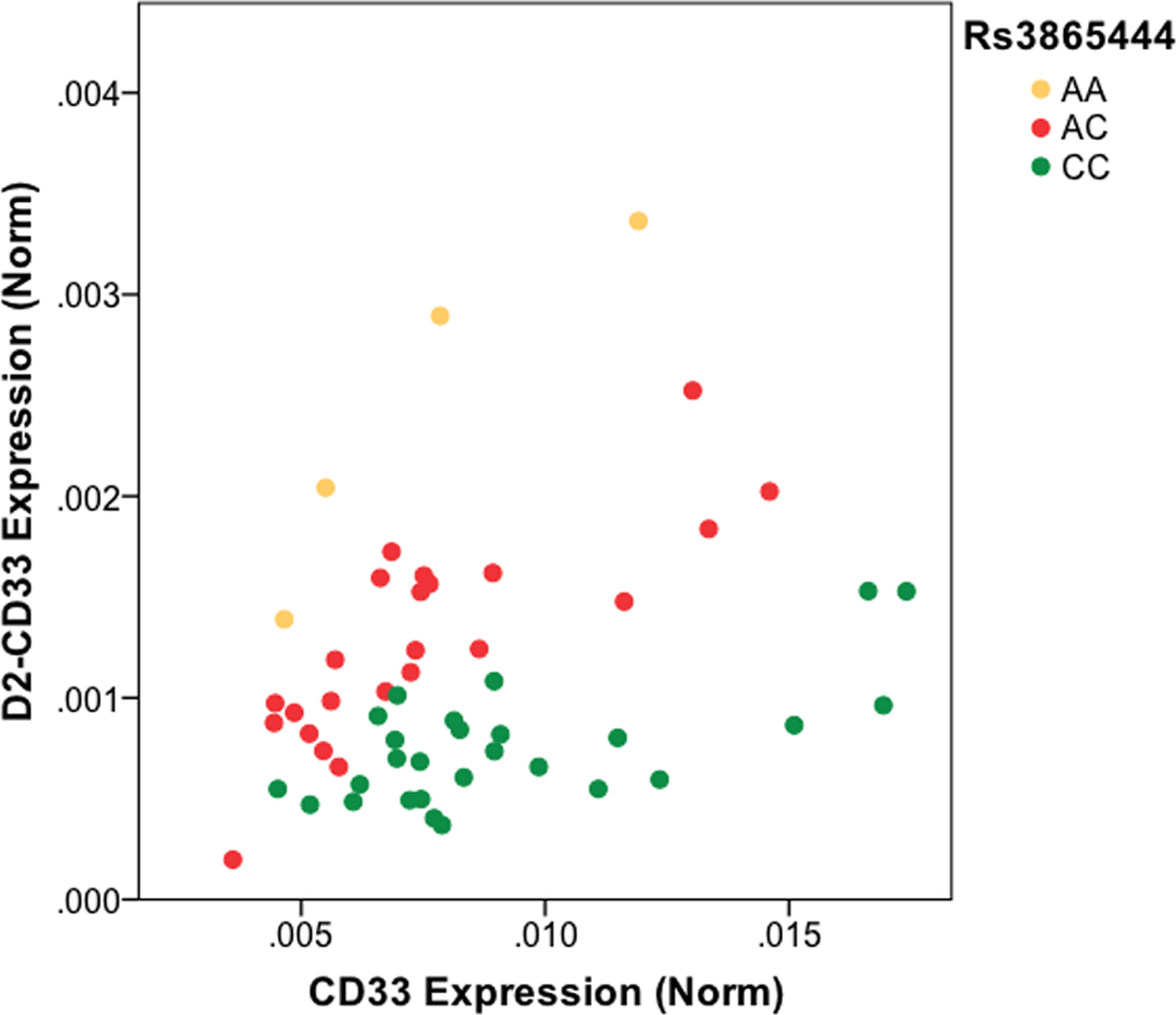

Acknowledging that CD33 is a single member of a multi-protein homeostatic cellular mechanism, we turn to consideration of the molecular mechanism whereby CD33 modulates AD risk. The primary AD GWAS SNP for CD33 is rs3865444, which is 372 bp upstream of the CD33 transcription start site. The minor allele of this SNP is associated with reduced AD risk [1, 2, 9]. Griciuc et al. did not detect an association between rs3865444 and CD33 mRNA expression and yet found reduced CD33 protein in rs3865444 minor allele carriers [55]. Subsequently, our laboratory found total CD33 mRNA was increased about 25% in AD and decreased modestly with the rs3865444 minor allele [56] (Table 1). Moreover, we found that a surprisingly common CD33 isoform in human brain was lacking exon 2 (D2-CD33, aka CD33ΔV-Ig [55] and CD33m [32]). Skipping of exon 2 deletes the CD33 IgV domain, leading to an in-frame fusion of the CD33 signal peptide directly to the IgC2 extracellular domain ([32], Figure 4). When we quantified D2-CD33 in comparison to CD33, by using isoform specific qPCR primers, we observed a striking correlation between rs3865444 and the proportion of CD33 mRNA expressed as D2-CD33 (Figure 5, Table 1, [56]). We hypothesized that rs3865444 was a proxy for a functional SNP because rs3865444 is in the promoter region of CD33. Indeed, sequencing and subsequent genotyping studies found an exon 2 SNP, rs12459419, that is in perfect linkage disequilibrium with rs3865444. Minigene studies confirmed that rs12459419 is a functional SNP with the minor allele increasing the proportion of D2-CD33 [56]. The finding that rs3865444 and its functional proxy, rs12459419, are associated with CD33 exon 2 splicing efficiency was subsequently confirmed in several reports [57–59]. We also identified a third CD33 isoform that retains intron 1 (R1-CD33) and found that this isoform also increased with the minor allele of rs3865444 [59]. Retention of the 62 bp intron 1 leads to a codon reading frameshift such that this isoform encodes only the signal peptide.

Table 1: CD33 isoform expression as a function of rs3865444 genotype [56, 59].

Means and standard errors (SE) are derived from a general linear model of CD33 isoform transcripts normalized to the geometric mean of AIF1 and ITGAM transcripts, taking both rs3865444 genotype and a dichotomous neuropathology score (i.e. high or low) [59]. The % Total CD33 mRNA columns represents the proportion each CD33 isoform within a genotype.

| rs3865444 CC (n = 25) | rs3865444 CA (n = 22) | rs3865444 AA (n = 4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD OR: [59] | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.83 | |||

| Isoform | Mean ± SE | % Total CC CD33 mRNA | Mean ± SE | % Total CA CD33 mRNA | Mean ± SE | % Total AA CD33 mRNA |

| FL-CD33 | 0.093 ± 0.004 | 85% | 0.069 ± 0.004 | 73% | 0.052 ± 0.010 | 57% |

| D2-CD33 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 8% | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 17% | 0.029 ± 0.002 | 31% |

| R1-CD33 | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 7% | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 10% | 0.010 ± 0.002 | 11% |

| Total CD33 | 0.109 ± 0.004 | 100% | 0.094 ± 0.005 | 100% | 0.091 ± 0.010 | 100% |

Figure 4. Structure of CD33 Gene, Common CD33 mRNA Isoforms, and their Predicted Protein Domains.

The sites of genetic variants relevant to this review are depicted on the CD33 exon structure. The modular nature of SIGLEC exons and protein domains are reflect in the structures of full-length CD33, CD33 lacking exon 2 (D2-CD33), and a secreted IgV domain arising from a four bp indel in exon 3 (noted by carot). This diagram is not drawn to scale, e.g., full-length CD33 protein is 364 amino acids, exon 2 encodes 127 amino acids and exon 3 encodes 93 amino acids. The cytosolic tail consists of 82 amino acids. Alternative splicing produces an atypical exon 7 that is less abundant and does not include ITIM motifs (not depicted).

Figure 5. Rs3865444 Allele Dose Dependent Association with CD33 Exon 2 Splicing Efficiency.

C is the major rs3865444 allele and A the minor allele. Each point represents the qPCR result from a different human brain RNA sample. Figure redrawn from Malik et al., with permission [56].

The association between rs12459419 and CD33 exon 2 splicing has also been documented by acute myeloid leukemia (AML) researchers, who are interested in CD33 as a target for antibody-based AML therapeutics [60, 61]. In fact, several, although not all studies, found a correlation between the rs12459419 major allele and increased efficacy of gemtuzumab-ozogamicin, which recognizes an epitope in the CD33 IgV domain (Table 2, [60–62] reviewed in [63]). Interestingly, Mortland et al reported that patients homozygous for the minor allele of rs12459419 were more likely to have favorable risk disease than those with the major allele (52% vs. 31%, p= 0.034) [60]. The minor allele homozygous individuals also had significantly lower diagnostic blast CD33 expression than other genotypes (p < 0.001) [60], suggestive that either lower CD33 or increased D2-CD33 may also lessen AML severity.

Table 2. CD33 antibodies and their epitopes.

Commonly used CD33 antibodies are indicated to help orient the reader.

| CD33 Antibody | Antigen/Recognized epitope | Selected citations |

|---|---|---|

| P67.6 (gemtuzumab-ozogamicin) | IgV domain | Lamba et al [61] Laszlo et al [64] |

| M195 (lintuzumab) | IgV domain | Sutherland et al [38] Malik et al [59] |

| EPR4423 | IgV domain | Walker et al [57] |

| WM53 | IgV domain | Perez-Oliva et al [32] |

| HIM3–4 | IgC2 domain | Perez-Oliva et al [32] |

| PWS44 | IgC2 domain | Gricuic et al [55] |

| H-110 | Transmembrane and cytosolic domain | Raj et al [58] |

| AC104.3E3 | CD33 | Bradshaw et al [65] |

The function(s) of D2-CD33, if any, have not been determined. Since loss of exon 2 does not alter the codon reading frame, D2-CD33 encodes a protein essentially identical to CD33 except for the loss of the IgV domain. Therefore, we and others originally hypothesized that D2-CD33 is non-functional because loss of the IgV domain would result in an inability to bind sialic acid-based ligands (reviewed in [5, 39]). Although humans and chimpanzees express both CD33 and D2-CD33, the allelic regulation of exon 2 splicing appears human-specific and has been hypothesized to reflect evolutionary pressure for longevity in humans [66].

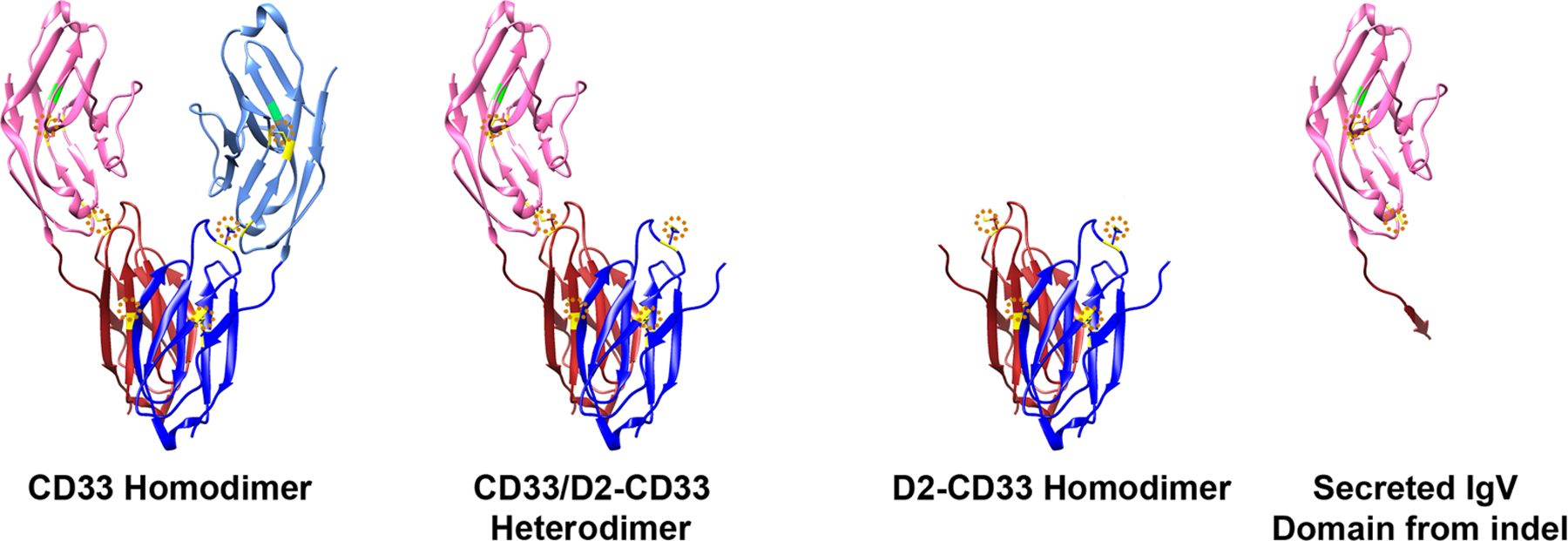

Several studies have described D2-CD33 as a cell-surface protein. For example, Perez-Oliva et al. transfected HEK293T cells with D2-CD33 and found expression on the cell surface by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence [32]. Our laboratory independently confirmed this finding in transfected HEK293T cells [59] as did Laszlo et al. [64]. CD33 is thought to normally exist on the cell surface as a homodimer ([67], Figure 6). The dimer is not stabilized by disulfide bonds but rather, based on x-ray crystallography models, appears to be stabilized by IgC2 domain interactions as there are no disulfide bonds between the two monomers. The interpretation that dimerization is mediated by the IgC2 domain suggests the possibility of D2-CD33 homodimers as well as CD33 and D2-CD33 heterodimers (Figure 6). Since D2-CD33 lacks the ligand binding domain, a heterodimer would be predicted to have lower ability to bind ligand but a similar ability to signal given the retention of both cytosolic domains. However, the feasibility of heterodimers at least is unclear and may be unlikely because ectopic expression of D2-CD33 did not influence internalization of full-length CD33 induced by the CD33 antibody p67.6, which recognizes the IgV domain [64]. If a portion of CD33 was engaged in a heterodimer with D2-CD33, this would have been predicted to decrease CD33 internalization. Overall, discernment of the role, if any, of dimerization in CD33 or D2-CD33 function and AD impact requires further experimentation.

Figure 6. CD33, D2-CD33 Homo- and Hetero-dimers, and IgV domain derived from CD33 indel.

CD33 homodimer model is based on CD33 x-ray crystallography (PDB:5J06 (www.rcsb.org/structure/5J06) [79]). D2-CD33 and indel models are derived from this CD33 model. Extracellular domains are shown. There are two monomers: one depicted as pink/red or the other as light blue/blue. The IgV domains are shown as pink or light blue and the IgC2 domains as red or dark blue. The arginine critical for sialic acid ligand binding is marked in green. Disulfide bonds are marked in yellow and circled in dotted orange. A CD33 monomer is stabilized by disulfide bonds within the IgV domain (aa41–101), within the IgC2 domain (aa163–212) and between the IgV and IgC2 domains (aa36–169, see dotted orange circles in CD33 homodimer). These three disulfide bonds are a common feature of all the SIGLECs [80]. D2-CD33 retains the disulfide bond within the IgC2 domain and has an unpaired cysteine that may be relevant to D2-CD33 gain of function. Conversely, the indel secreted IgV domain retains the disulfide bond within the IgV domain and also has an unpaired cysteine.

The finding that the minor allele of rs3865444 is associated with reduced full-length CD33 is essentially unequivocal because of its reproducibility in multiple labs and experimental models. The magnitude of the reduction has been somewhat variable between reports and tissue types. Our laboratory performed qPCR on human brain in an absolute fashion by using reference standards and found that the mRNA encoding apparently full-length CD33 was reduced by ~44% in a comparison between major and minor allele homozygous individuals (Table 1, [59]). At the protein level, Griciuc et al. performed Western blots of human brain by using the PWS44 IgC2 antibody and found a 30–60% reduction in CD33 protein in carriers of the rs3865444 minor allele, depending on the normalization protein [55]. Walker et al. performed Western blots on human brain with EPR4423, an antibody against the IgV domain, and reported an approximately three-fold reduction in CD33 in a comparison of rs3865444 major and minor allele homozygous individuals [57]. Raj et al examined peripheral blood mononuclear cells in Western blots with H-110, a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the CD33 cytosolic tail, and reported a larger, 15-fold reduction in CD33 in minor allele homozygous individuals [58]. Bradshaw et al. evaluated human monocytes with flow cytometry involving an antibody raised against the CD33 protein (AC104.3E3) and reported a seven-fold reduction in CD33 mean fluorescence intensity between major and minor allele homozygous individuals [65]. Lastly, Mortland et al. used a similar approach and reported a three-fold reduction in CD33 expression in AML blasts between homozygous major and minor allele individuals [60]. The actual CD33 epitopes recognized by the antibodies in the flow cytometry studies are not clear. Overall, we interpret variability in the quantitative impact of CD33 genetics on CD33 protein as reflecting differences in tissue type and/or assay techniques. In summary, the primary impact of rs3865444, and its functional proxy, rs12459419, appears to be an allele dose-dependent increase in D2-CD33 at the expense of full-length CD33 with secondary effects being a decrease in total CD33 and an increase in R1-CD33. Of particular importance, the genetics of AD risk show a similar allele dose-dependent pattern and increased protection against AD (Table 1).

CD33 genetic impact on microglial function

Given that CD33 contains an ITIM and is expressed on microglia, several groups have evaluated the impact of CD33 genetics on microglial function. Griciuc et al. quantified CD33+ microglia per unit area in human AD brain samples by immunohistochemistry and reported a decrease with the rs3865444 minor allele [55]. Since this study used the CD33 antibody PWS44, which recognizes an IgC2 domain present in both CD33 and D2-CD33, this decrease in CD33+ microglia is not due to lower CD33 expression per se. Bradshaw et al. reported a decrease in the frequency of stage III microglia/macrophages with rs3865444, consistent with a possible decrease in microglial activation with the rs3865444 minor allele [65]. The finding that levels of SIGLEC mRNAs, including Cd33, are decreased in disease-associated murine microglia, while TREM2 mRNA is increased and is required to achieve this microglial subtype, is supportive of the concept that SIGLECs and TREM2 generally modulate microglial activation in opposing directions [68]. Given the importance of innate immunity, its somewhat surprising that rs3865444 and TREM2 polymorphisms are not associated with more human conditions. Besides AD, the primary GWAS finding for rs3865444 is decrease with the minor allele of white blood cells, specifically those involving the myeloid lineage (p value = 6.81 × 10−14) [69]. Although microglia are derived from a separate lineage than monocytes in the periphery, whether this finding may be relevant to microglia abundance in brain is not clear. Perhaps this decrease in peripheral myeloid cells may promote subclinical infections, e.g., periodontal disease, which is thought to be one of the many socioeconomic or medical contributing factors in AD [70, 71].

To evaluate CD33 impact on immune cell function, researchers have transfected microglial cell models with CD33 constructs and evaluated monocytes as a function of CD33 genotype. For example, overexpression of human CD33, but not D2-CD33, in the murine microglial BV2 cell line inhibited Aβ42 uptake [55]. Similarly, Bradshaw et al. studied human monocytes and found a dose dependent inhibition of uptake of dextran beads and Aß42 with increasing copies of the rs3865444 major allele [65]. These in vitro findings are consistent with CD33, but not D2-CD33, acting to inhibit microglial phagocytosis. This possibility is supported by in vivo findings that the rs3865444 minor allele is correlated with decreased formic acid-soluble Aβ42 in frontal cortex of AD brains as well as an apparent amyloid reduction in living individuals, as detected by Pittsburgh Compound-B (PIB) [55, 65]. In summary, the rs3865444 minor allele is associated with reduced CD33, increased D2-CD33, increased uptake of Aß and dextran uptake, decreased Aß burden in vivo and decreased AD risk.

Current findings in CD33 genetics and AD

In considering CD33 genetics and AD more broadly, we recently investigated the impact of a four bp insertion/deletion (indel), rs201074739, in exon 3 of CD33. The deletion is moderately rare with a ~2.4% minor allele frequency in European populations. The rs201074739 deletion causes a frameshift in the CD33 codon reading frame at amino acid 155. This results in aberrant amino acids at positions 156–159 and then a premature stop codon. Hence, instead of CD33 as a 364 amino acid type-1 transmembrane protein, CD33 containing this 4bp deletion is predicted to be a secreted protein consisting of the IgV domain and approximately 16 amino acids of the IgC2 domain (Figure 6). As such, this deletion would preclude both CD33 and D2-CD33. This was demonstrated in a very recent report by Papageorgiou et al. describing an individual that was homozygous for this deletion and had no detectable cell surface CD33 on their monocytes [72]. We investigated CD33 expression and splicing in several individuals heterozygous for the indel (Table 3). Although one may have hypothesized that loss of CD33 due to the indel would lead to a compensatory increase in CD33 expression, we found that CD33 mRNA levels appeared reduced in indel carriers. This decrease in apparent CD33 may reflect nonsense mediated RNA decay which was demonstrated for this isoform in the recent report by Papageorgiou et al. [72]. We also considered the possibility that atypical splicing may generate an unusual CD33 isoform that retained ITIM function in these individuals. Indeed, we found a CD33 isoform unique to the indel carriers wherein a novel splice donor site was introduced a few bp after the rs201074739 deletion. This donor site was spliced into an acceptor site at the 24th bp of exon 6 rather than the beginning of exon 4. Overall, this isoform consisted of exons 1, 2, and 7, along with fragments of exon 3 and 6 and again encoded a truncated CD33 protein consisting of essentially the signal peptide, IgV domain and fragment of the IgC2 domain.

Table 3. CD33 Expression Appears Decreased in indel Carriers.

These results were determined by qPCR by using primers in exons 4 and 5 for CD33. CD33 data are normalized to the geometric mean of ITGAM and AIF1, as described [56]. The apparent decrease in CD33 expression in carriers of the indel may reflect lower CD33 mRNA levels due to nonsense mediated RNA decay [72] and/or a loss of exons 4 and 5 in an isoform unique to the indel carriers.

| Brain Region | indel | CD33 Expression (mean ±SD, (n)) |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal Cortex | Non-Carrier | 0.245 ± 0.034 (3) |

| Carrier | 0.162 ± 0.009 (3) | |

| Cerebellum | Non-Carrier | 0.177 ± 0.034 (5) |

| Carrier | 0.142 ± 0.023 (5) |

Since the rs3865444 minor allele is associated with decreased full-length CD33 and decreased AD risk, we hypothesized that this indel would also be associated with reduced AD risk. To evaluate this possibility, we used results from the most recent IGAP AD meta-analysis [8]. As a positive control to assess whether CD33 genetics are associated with AD, we examined the CD33 exon 2 splicing SNP, rs12459419, and found a significant association with AD risk (OR = 0.92 (95% CI: 0.90–0.95), p=4.5×10−7). This was a robust sample set of 21,982 AD cases and 41,944 non-AD cases. However, the 4 bp indel was not significantly associated with AD risk in these same data (p=0.1337, OR=0.90 (95% CI: 0.79–1.03). While post-hoc power calculations have well-known limitations [73], it is somewhat revealing that a dataset of this size (>60k individuals) confers 80% statistical power to detect an odds ratio as small as 0.90 for a variant with a minor allele frequency similar to this indel (2.4%).

Current Model for CD33 and AD

Based on our current understanding of CD33 genetics, AD risk and SNP actions, an interesting paradigm has emerged. The AD-associated SNP, rs3865444, acts through the linked SNP rs12459419 to primarily increase aberrant exon 2 splicing. This results in a D2-CD33 increase at the expense of CD33. Reduced functional CD33 was hypothesized to mediate reduced AD risk. This loss of function hypothesis is derived from the demonstrated ability of ligand binding to the CD33 IgV domain to cause CD33 clustering and ITIM phosphorylation and overall lead to an inhibition in phagocytic-type activity. A decrease in CD33 inhibition of microglial function was thought to increase microglial function, e.g., clearance of amyloid and cell debris and, over time, lead to reduced AD pathology. The conclusion in this loss of function hypothesis is that further reducing CD33 protein via pharmacologic means (antibodies, small molecules, anti-sense approaches) would reduce AD incidence and severity [39, 59].

This theory is now called into question because of the data regarding the rs201074739 indel variant. Although the indel is expected to cause a 50% reduction in CD33 in heterozygous individuals and to produce a complete loss of CD33 cell surface expression in homozygous individuals [72], this indel does not appear to modulate AD risk. Considering CD33 genetic findings overall, we conclude that (i) an AD-protective splicing SNP, rs12459419, increases D2-CD33 and decreases CD33 but (ii) an indel that robustly decreases CD33 has no effect on AD risk. While we recognize that future genetic studies may yield new findings, a parsimonious interpretation of available data is that AD protection may well be mediated by the increase in D2-CD33, i.e., D2-CD33 represents a gain of function variant to protect from AD.

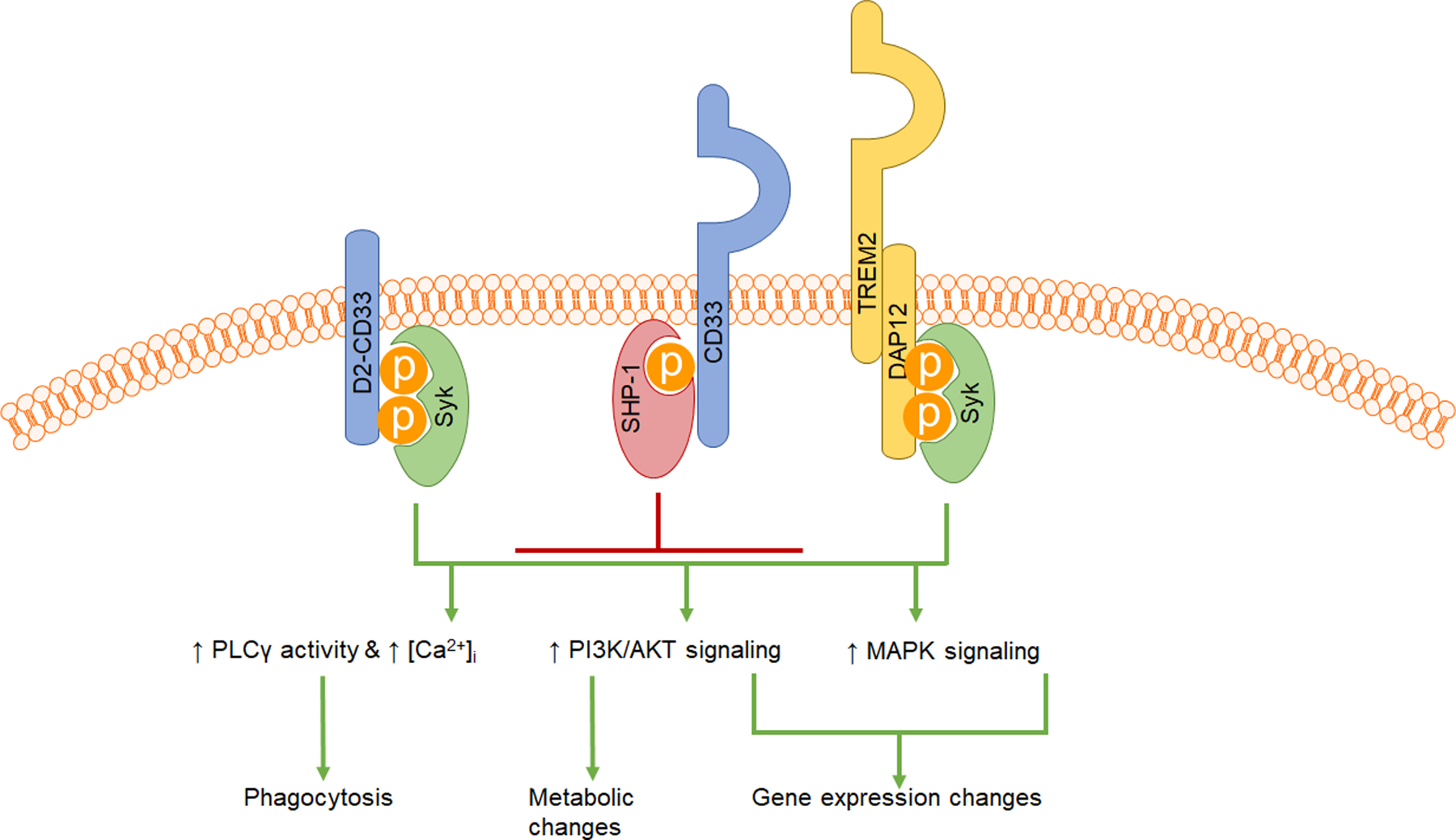

In considering possible mechanisms for a D2-CD33 gain of function, we note that the rs3865444 minor allele is associated with an increase in D2-CD33 [56, 57, 65] as well as decreased amyloid burden [57, 65], and increased Aß42 uptake [65]. Although we initially attributed these actions to a decrease in CD33 ITIM signaling, they are also consistent with ITAM signaling. In considering this possibility further, we note that the sequence of the CD33 ITIM and ITIM-like region represents a near-canonical ITAM sequence (Figure 7) [45–47, 49]. A clear precedent for ITIMs acting as an ITAM can be found with PECAM-1 which has an ITIM and an ITIM-like sequence similar to that of CD33. Although PECAM-1 signaling is generally thought to be immunosuppressive, PECAM-1 has also been shown to bind and activate Syk when the two tyrosines in the PECAM-1 “ITAM” sequence are phosphorylated [74]. Other studies have also suggested that “ITAM” sequences similar to those in CD33 can bind Syk as well as ZAP70 and lead to cellular activation [48, 75, 76]. Hence, the gain of function whereby D2-CD33 reduces AD risk may be due to D2-CD33 acting as an ITAM to activate microglial function (Figure 8). We speculate that this gain of function in D2-CD33 but not CD33 is due to the smaller extracellular domain of D2-CD33. The loss of the IgV domain, which represents about 1/3 of the total CD33 protein, may allow D2-CD33 to cluster in a novel conformation and facilitate dual ITAM motif phosphorylation. This is analogous to the way TREM2 switches from an immune inhibitor, in response to a low avidity ligand, to an immune activator, in response to a high avidity ligand, in a process mediated by DAP12 monophosphorylation and dual phosphorylation, respectively. D2-CD33, which lacks any ligand binding capability, may constitutively function as an ITAM. In summary, the hypothesis that D2-CD33 can act as an ITAM and bind Syk to generate an activating signal is experimentally testable and a current focus of on-going work.

Figure 7. Comparison of CD33 ITIM and ITIM-like Region with Consensus ITAM Sequence.

The consensus ITAM sequence is D/ExxYxxL//I x6–12YxxL/V/I. Similar variations with the ITAM consensus sequence have been reported for functional ITAMs previously [45–47, 49]. ITAM sequences with longer spacers have also been reported to bind and activate Syk [74, 81].

Figure 8: Working model of D2-CD33 neuroprotection in AD.

Full-length CD33 recruits phosphatases such as SHP-1 and SHP-2. Targets of SHP-1 include spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and scaffolding proteins such as the B cell linker protein BLNK. SHP-1 dephosphorylates these proteins, thus acting as a negative regulator for microglial activation. Syk activation leads to multiple downstream cellular events, including calcium mobilization via phospholipase C γ activity, protein kinase B (AKT) signaling, and extracellular-related kinase (MAPK/ERK) signaling. These events lead to metabolic and transcriptional changes, along with context-dependent increases in activities such as phagocytosis and chemotaxis. D2-CD33 may be locked in a constitutively active or permissive conformation, leading to Syk recruitment at the membrane, and ultimately resulting in a higher propensity toward microglial activation through mechanisms similar to the well-recognized functions of TREM2 and its co-receptor, DAP12.

Finally, the presence of the unpaired cysteine in the IgC2 domain of D2-CD33 may also contribute to a gain of function. D2-CD33 homodimers may possibly form a disulfide bond between the two IgC2 domains. If this occurs, it is unclear whether this would stabilize D2-CD33 or lead to increased clearance. This might determine the proportion of D2-CD33 homodimer versus heterodimer formation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Whether a D2-CD33 gain of function exists, and whether it is due to D2-CD33 monomer, homodimers, or D2-CD33/CD33 heterodimers has yet to be experimentally shown.

Conclusions

Three findings are critical to the evaluation of CD33 as an AD modulator. First, the minor allele of rs3865444 is associated with reduced AD risk in the largest AD GWAS performed to date. Second, rs12459419, which is in near-perfect linkage disequilibrium with rs3865444, modulates the efficiency of CD33 exon 2 splicing. In combination, these two results provide very strong evidence that a decrease in CD33 or an increase in D2-CD33 reduces AD risk. Third, rs201074739, a four bp indel that precludes CD33, does not appear associated with AD risk. Overall, we interpret these findings as reducing the likelihood that a decrease in CD33 protects from AD. Rather, we currently hypothesize that an increase in D2-CD33 protects from AD. Studies to confirm the lack of indel association with AD and to determine the mechanism whereby D2-CD33 protects from AD are on-going. The insights gained through this process will hopefully lead to pharmacologic agents that maximize this protective pathway to reduce AD risk.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (RF1AG059717 and P30AG028383).

Bibliography

- 1.Hollingworth P, Harold D, Sims R, Gerrish A, Lambert JC, Carrasquillo MM, et al. , Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet, 2011. 43(5): p. 429–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naj AC, Jun G, Beecham GW, Wang LS, Vardarajan BN, Buros J, et al. , Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet, 2011. 43(5): p. 436–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, et al. , Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet, 2013. 45(12): p. 1452–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Efthymiou AG and Goate AM, Late onset Alzheimer’s disease genetics implicates microglial pathways in disease risk. Mol Neurodegener, 2017. 12(1): p. 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik M, Parikh I, Vasquez JB, Smith C, Tai L, Bu G, et al. , Genetics ignite focus on microglial inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener, 2015. 10: p. 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen DV, Hanson JE, and Sheng M, Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol, 2018. 217(2): p. 459–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertram L, Lange C, Mullin K, Parkinson M, Hsiao M, Hogan MF, et al. , Genome-wide association analysis reveals putative Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility loci in addition to APOE. Am J Hum Genet, 2008. 83(5): p. 623–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, Damotte V, Naj AC, et al. , Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Abeta, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet, 2019. 51(3): p. 414–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen IE, Savage JE, Watanabe K, Bryois J, Williams DM, Steinberg S, et al. , Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat Genet, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz F, Fong JJ, and Varki A, Human-specific evolutionary changes in the biology of siglecs. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2015. 842: p. 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salminen A and Kaarniranta K, Siglec receptors and hiding plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Med (Berl), 2009. 87(7): p. 697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor VC, Buckley CD, Douglas M, Cody AJ, Simmons DL, and Freeman SD, The myeloid-specific sialic acid-binding receptor, CD33, associates with the protein-tyrosine phosphatases, SHP-1 and SHP-2. J Biol Chem, 1999. 274(17): p. 11505–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crocker PR and Varki A, Siglecs in the immune system. Immunology, 2001. 103(2): p. 137–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padler-Karavani V, Hurtado-Ziola N, Chang YC, Sonnenburg JL, Ronaghy A, Yu H, et al. , Rapid evolution of binding specificities and expression patterns of inhibitory CD33-related Siglecs in primates. FASEB J, 2014. 28(3): p. 1280–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishii T, Angata T, Wan ES, Cho MH, Motegi T, Gao C, et al. , Influence of SIGLEC9 polymorphisms on COPD phenotypes including exacerbation frequency. Respirology, 2017. 22(4): p. 684–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graustein AD, Horne DJ, Fong JJ, Schwarz F, Mefford HC, Peterson GJ, et al. , The SIGLEC14 null allele is associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis- and BCG-induced clinical and immunologic outcomes. Tuberculosis (Edinb), 2017. 104: p. 38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamanaka M, Kato Y, Angata T, and Narimatsu H, Deletion polymorphism of SIGLEC14 and its functional implications. Glycobiology, 2009. 19(8): p. 841–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varki A, Since there are PAMPs and DAMPs, there must be SAMPs? Glycan “self-associated molecular patterns” dampen innate immunity, but pathogens can mimic them. Glycobiology, 2011. 21(9): p. 1121–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angata T, Possible Influences of Endogenous and Exogenous Ligands on the Evolution of Human Siglecs. Front Immunol, 2018. 9: p. 2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubbers J, Rodriguez E, and van Kooyk Y, Modulation of Immune Tolerance via Siglec-Sialic Acid Interactions. Front Immunol, 2018. 9: p. 2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlin AF, Uchiyama S, Chang YC, Lewis AL, Nizet V, and Varki A, Molecular mimicry of host sialylated glycans allows a bacterial pathogen to engage neutrophil Siglec-9 and dampen the innate immune response. Blood, 2009. 113(14): p. 3333–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angata T, Margulies EH, Green ED, and Varki A, Large-scale sequencing of the CD33-related Siglec gene cluster in five mammalian species reveals rapid evolution by multiple mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(36): p. 13251–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao H and Crocker PR, Evolution of CD33-related siglecs: regulating host immune functions and escaping pathogen exploitation? Immunology, 2011. 132(1): p. 18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bornhofft KF, Goldammer T, Rebl A, and Galuska SP, Siglecs: A journey through the evolution of sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectins. Dev Comp Immunol, 2018. 86: p. 219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angata T, Hayakawa T, Yamanaka M, Varki A, and Nakamura M, Discovery of Siglec-14, a novel sialic acid receptor undergoing concerted evolution with Siglec-5 in primates. FASEB J, 2006. 20(12): p. 1964–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao H, Lakner U, de Bono B, Traherne JA, Trowsdale J, and Barrow AD, SIGLEC16 encodes a DAP12-associated receptor expressed in macrophages that evolved from its inhibitory counterpart SIGLEC11 and has functional and non-functional alleles in humans. Eur J Immunol, 2008. 38(8): p. 2303–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macauley MS, Crocker PR, and Paulson JC, Siglec-mediated regulation of immune cell function in disease. Nat Rev Immunol, 2014. 14(10): p. 653–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crocker PR, Paulson JC, and Varki A, Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol, 2007. 7(4): p. 255–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravetch JV and Lanier LL, Immune inhibitory receptors. Science, 2000. 290(5489): p. 84–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul SP, Taylor LS, Stansbury EK, and McVicar DW, Myeloid specific human CD33 is an inhibitory receptor with differential ITIM function in recruiting the phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2. Blood, 2000. 96(2): p. 483–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walter RB, Hausermann P, Raden BW, Teckchandani AM, Kamikura DM, Bernstein ID, et al. , Phosphorylated ITIMs enable ubiquitylation of an inhibitory cell surface receptor. Traffic, 2008. 9(2): p. 267–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Oliva AB, Martinez-Esparza M, Vicente-Fernandez JJ, Corral-San Miguel R, Garcia-Penarrubia P, and Hernandez-Caselles T, Epitope mapping, expression and post-translational modifications of two isoforms of CD33 (CD33M and CD33m) on lymphoid and myeloid human cells. Glycobiology, 2011. 21(6): p. 757–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ulyanova T, Blasioli J, Woodford-Thomas TA, and Thomas ML, The sialoadhesin CD33 is a myeloid-specific inhibitory receptor. Eur J Immunol, 1999. 29(11): p. 3440–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizuno K, Tagawa Y, Mitomo K, Arimura Y, Hatano N, Katagiri T, et al. , Src homology region 2 (SH2) domain-containing phosphatase-1 dephosphorylates B cell linker protein/SH2 domain leukocyte protein of 65 kDa and selectively regulates c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation in B cells. J Immunol, 2000. 165(3): p. 1344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizuno K, Tagawa Y, Mitomo K, Watanabe N, Katagiri T, Ogimoto M, et al. , Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase 1 positively regulates B cell receptor-induced apoptosis by modulating association of B cell linker protein with Nck and activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. J Immunol, 2002. 169(2): p. 778–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orr SJ, Morgan NM, Elliott J, Burrows JF, Scott CJ, McVicar DW, et al. , CD33 responses are blocked by SOCS3 through accelerated proteasomal-mediated turnover. Blood, 2007. 109(3): p. 1061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hernandez-Caselles T, Martinez-Esparza M, Perez-Oliva AB, Quintanilla-Cecconi AM, Garcia-Alonso A, Alvarez-Lopez DM, et al. , A study of CD33 (SIGLEC-3) antigen expression and function on activated human T and NK cells: two isoforms of CD33 are generated by alternative splicing. J Leukoc Biol, 2006. 79(1): p. 46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutherland MK, Yu C, Lewis TS, Miyamoto JB, Morris-Tilden CA, Jonas M, et al. , Anti-leukemic activity of lintuzumab (SGN-33) in preclinical models of acute myeloid leukemia. MAbs, 2009. 1(5): p. 481–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao L, CD33 in Alzheimer’s Disease - Biology, Pathogenesis, and Therapeutics: A Mini-Review. Gerontology, 2018: p. 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duan S, Koziol-White CJ, Jester WF Jr., Nycholat CM, Macauley MS, Panettieri RA Jr., et al. , CD33 recruitment inhibits IgE-mediated anaphylaxis and desensitizes mast cells to allergen. J Clin Invest, 2019. 129(3): p. 1387–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linnartz B and Neumann H, Microglial activatory (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif)- and inhibitory (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif)-signaling receptors for recognition of the neuronal glycocalyx. Glia, 2013. 61(1): p. 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gratuze M, Leyns CEG, and Holtzman DM, New insights into the role of TREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener, 2018. 13(1): p. 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi Y and Holtzman DM, Interplay between innate immunity and Alzheimer disease: APOE and TREM2 in the spotlight. Nat Rev Immunol, 2018. 18(12): p. 759–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jay TR, von Saucken VE, and Landreth GE, TREM2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol Neurodegener, 2017. 12(1): p. 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sada K, Takano T, Yanagi S, and Yamamura H, Structure and function of Syk protein-tyrosine kinase. J Biochem, 2001. 130(2): p. 177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Underhill DM and Goodridge HS, The many faces of ITAMs. Trends Immunol, 2007. 28(2): p. 66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strzelecka A, Kwiatkowska K, and Sobota A, Tyrosine phosphorylation and Fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis. FEBS Lett, 1997. 400(1): p. 11–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamerman JA, Ni M, Killebrew JR, Chu CL, and Lowell CA, The expanding roles of ITAM adapters FcRgamma and DAP12 in myeloid cells. Immunol Rev, 2009. 232(1): p. 42–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barrow AD and Trowsdale J, You say ITAM and I say ITIM, let’s call the whole thing off: the ambiguity of immunoreceptor signalling. Eur J Immunol, 2006. 36(7): p. 1646–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pasquier B, Launay P, Kanamaru Y, Moura IC, Pfirsch S, Ruffie C, et al. , Identification of FcalphaRI as an inhibitory receptor that controls inflammation: dual role of FcRgamma ITAM. Immunity, 2005. 22(1): p. 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ganesan LP, Fang H, Marsh CB, and Tridandapani S, The protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 associates with the phosphorylated immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif of Fc gamma RIIa to modulate signaling events in myeloid cells. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(37): p. 35710–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peng Q, Malhotra S, Torchia JA, Kerr WG, Coggeshall KM, and Humphrey MB, TREM2- and DAP12-dependent activation of PI3K requires DAP10 and is inhibited by SHIP1. Sci Signal, 2010. 3(122): p. ra38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamerman JA, Jarjoura JR, Humphrey MB, Nakamura MC, Seaman WE, and Lanier LL, Cutting edge: inhibition of TLR and FcR responses in macrophages by triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM)-2 and DAP12. J Immunol, 2006. 177(4): p. 2051–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Billadeau DD and Leibson PJ, ITAMs versus ITIMs: striking a balance during cell regulation. J Clin Invest, 2002. 109(2): p. 161–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Griciuc A, Serrano-Pozo A, Parrado AR, Lesinski AN, Asselin CN, Mullin K, et al. , Alzheimer’s disease risk gene CD33 inhibits microglial uptake of amyloid beta. Neuron, 2013. 78(4): p. 631–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malik M, Simpson JF, Parikh I, Wilfred BR, Fardo DW, Nelson PT, et al. , CD33 Alzheimer’s risk-altering polymorphism, CD33 expression, and exon 2 splicing. J Neurosci, 2013. 33(33): p. 13320–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker DG, Whetzel AM, Serrano G, Sue LI, Beach TG, and Lue LF, Association of CD33 polymorphism rs3865444 with Alzheimer’s disease pathology and CD33 expression in human cerebral cortex. Neurobiol Aging, 2015. 36(2): p. 571–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raj T, Ryan KJ, Replogle JM, Chibnik LB, Rosenkrantz L, Tang A, et al. , CD33: increased inclusion of exon 2 implicates the Ig V-set domain in Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility. Hum Mol Genet, 2014. 23(10): p. 2729–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malik M, Chiles J 3rd, Xi HS, Medway C, Simpson J, Potluri S, et al. , Genetics of CD33 in Alzheimer’s disease and acute myeloid leukemia. Hum Mol Genet, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mortland L, Alonzo TA, Walter RB, Gerbing RB, Mitra AK, Pollard JA, et al. , Clinical significance of CD33 nonsynonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with gemtuzumab-ozogamicin-containing chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res, 2013. 19(6): p. 1620–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamba JK, Chauhan L, Shin M, Loken MR, Pollard JA, Wang YC, et al. , CD33 Splicing Polymorphism Determines Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin Response in De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Report From Randomized Phase III Children’s Oncology Group Trial AAML0531. J Clin Oncol, 2017. 35(23): p. 2674–2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laszlo GS, Beddoe ME, Godwin CD, Bates OM, Gudgeon CJ, Harrington KH, et al. , Relationship between CD33 expression, splicing polymorphism, and in vitro cytotoxicity of gemtuzumab ozogamicin and the CD33/CD3 BiTErAMG 330. Haematologica, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gbadamosi M, Meshinchi S, and Lamba JK, Gemtuzumab ozogamicin for treatment of newly diagnosed CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia. Future Oncol, 2018. 14: p. 3199–3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laszlo GS, Harrington KH, Gudgeon CJ, Beddoe ME, Fitzgibbon MP, Ries RE, et al. , Expression and functional characterization of CD33 transcript variants in human acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(28): p. 43281–43294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bradshaw EM, Chibnik LB, Keenan BT, Ottoboni L, Raj T, Tang A, et al. , CD33 Alzheimer’s disease locus: altered monocyte function and amyloid biology. Nat Neurosci, 2013. 16(7): p. 848–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwarz F, Springer SA, Altheide TK, Varki NM, Gagneux P, and Varki A, Human-specific derived alleles of CD33 and other genes protect against postreproductive cognitive decline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(1): p. 74–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Siddiqui S, Schwarz F, Springer S, Khedri Z, Yu H, Deng L, et al. , Studies on the Detection, Expression, Glycosylation, Dimerization, and Ligand Binding Properties of Mouse Siglec-E. J Biol Chem, 2017. 292(3): p. 1029–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, Matcovitch-Natan O, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Ulland TK, et al. , A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell, 2017. 169(7): p. 1276–1290 e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tajuddin SM, Schick UM, Eicher JD, Chami N, Giri A, Brody JA, et al. , Large-Scale Exome-wide Association Analysis Identifies Loci for White Blood Cell Traits and Pleiotropy with Immune-Mediated Diseases. Am J Hum Genet, 2016. 99(1): p. 22–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stein PS, Desrosiers M, Donegan SJ, Yepes JF, and Kryscio RJ, Tooth loss, dementia and neuropathology in the Nun study. J Am Dent Assoc, 2007. 138(10): p. 1314–22; quiz 1381–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, Benedyk M, Marczyk A, Konradi A, et al. , Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv, 2019. 5(1): p. eaau3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Papageorgiou I, Loken MR, Brodersen LE, Gbadamosi M, Uy GL, Meshinchi S, et al. , CCGG deletion (rs201074739) in CD33 results in premature termination codon and complete loss of CD33 expression: another key variant with potential impact on response to CD33-directed agents. Leuk Lymphoma, 2019: p. 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoenig JM and Heisey DM, The abuse of power: the pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. Am Stat, 2001. 55(1): p. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang J, Wu Y, Hu H, Wang W, Lu Y, Mao H, et al. , Syk protein tyrosine kinase involves PECAM-1 signaling through tandem immunotyrosine inhibitory motifs in human THP-1 macrophages. Cell Immunol, 2011. 272(1): p. 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Balaian L, Zhong RK, and Ball ED, The inhibitory effect of anti-CD33 monoclonal antibodies on AML cell growth correlates with Syk and/or ZAP-70 expression. Exp Hematol, 2003. 31(5): p. 363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Konishi H and Kiyama H, Microglial TREM2/DAP12 Signaling: A Double-Edged Sword in Neural Diseases. Front Cell Neurosci, 2018. 12: p. 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang Y, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, Caneda C, Plaza CA, Blumenthal PD, et al. , Purification and Characterization of Progenitor and Mature Human Astrocytes Reveals Transcriptional and Functional Differences with Mouse. Neuron, 2016. 89(1): p. 37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Olah M, Patrick E, Villani AC, Xu J, White CC, Ryan KJ, et al. , A transcriptomic atlas of aged human microglia. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rose AS, Bradley AR, Valasatava Y, Duarte JM, Prlic A, and Rose PW, NGL viewer: web-based molecular graphics for large complexes. Bioinformatics, 2018. 34(21): p. 3755–3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Crocker PR and Varki A, Siglecs, sialic acids and innate immunity. Trends Immunol, 2001. 22(6): p. 337–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marczynke M, Groger K, and Seitz O, Selective Binders of the Tandem Src Homology 2 Domains in Syk and Zap70 Protein Kinases by DNA-Programmed Spatial Screening. Bioconjug Chem, 2017. 28(9): p. 2384–2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]