Significance

The influenza M2 protein is an integral membrane protein that transports protons across the viral envelope upon acid activation. M2 has become the target of numerous experimental and theoretical studies due to its important role in flu infection; however, there are still unresolved questions regarding the proton-conductance mechanism. In addition, these studies were mostly performed on constructs containing only the TM domain of the protein. We have applied explicit solvent CpHMDMSλD to the M2 construct containing the TM and AH domains, as well as the truncated M2. Our model provides a qualitative picture of pH-dependent conformational transitions in the M2 channel that suggests an important role of the AH on this transition and, consequently, on the proton-transport mechanism.

Keywords: explicit solvent CpHMD, M2 transmembrane protein, amphipathic helix

Abstract

The matrix-2 (M2) protein from influenza A virus is a tetrameric, integral transmembrane (TM) protein that plays a vital role in viral replication by proton flux into the virus. The His37 tetrad is a pH sensor in the center of the M2 TM helix that activates the channel in response to the low endosomal pH. M2 consists of different regions that are believed to be involved in membrane targeting, packaging, nucleocapsid binding, and proton transport. Although M2 has been the target of many experimental and theoretical studies that have led to significant insights into its structure and function under differing conditions, the main mechanism of proton transport, its conformational dynamics, and the role of the amphipathic helices (AHs) on proton conductance remain elusive. To this end, we have applied explicit solvent constant pH molecular dynamics using the multisite λ-dynamics approach (CpHMDMSλD) to investigate the buried ionizable residues comprehensively and to elucidate their effect on the conformational transition. Our model recapitulates the pH-dependent conformational transition of M2 from closed to open state when the AH domain is included in the M2 construct, revealing the role of the amphipathic helices on this transition and shedding light on the proton-transport mechanism. This work demonstrates the importance of including the amphipathic helices in future experimental and theoretical studies of ion channels. Finally, our work shows that explicit solvent CpHMDMSλD provides a realistic pH-dependent model for membrane proteins.

The matrix-2 (M2) proton channel is an integral membrane protein comprising a homotetramer that plays a critical role in the initiation of the infection and replication of the influenza A virus. There are four main domains in this protein: an N-terminal domain, which is located in the viral exterior (residues 1 to 21); followed by a short transmembrane (TM) domain region that spans across the viral membrane (residues 22 to 46); a short amphipathic helix (AH) at the interface of the cytoplasmic membrane (residues 47 to 67); and, finally, the C-terminal domain of the peptide that is located in the viral interior (residues 68 to 97). M2 allows a unidirectional (vectorial) proton flux across the viral membrane in response to the low pH of the viral exterior. It has been proposed that the injection of the viral genetic material into the host cell in later stages of the infection is due to the acidification of the virion. Consequently, the viral RNA dissociates from the matrix protein, which triggers the fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes (1–4).

M2 is the target of the amantadine class of antiviral drugs; however, the efficiency of this drug has decreased significantly in recent years due to the mutations in the M2 TM domain (5). Therefore, further understanding of the mechanism, function, and structure of the M2 protein has significant public health relevance. Its small size and the important roles of M2 in flu infection has made it the topic of numerous studies, which have led to intricate details about its structure and function in different membrane-mimetic environments and under different conditions (1–4, 6–13). It has been shown that a histidine tetrad at position 37 in the core of the M2 channel has an active role in each proton-conductance cycle, since mutation of this residue to a variety of other amino acids disrupts the channel’s proton sensitivity and selectivity (9–11, 14).

Extensive electrophysiological experiments along with X-ray crystallography, NMR studies, and computational/theoretical modeling have been performed throughout the years to shed light on the mechanism of the proton transfer across the membrane by M2. However, despite significant findings, there are still several questions facing the field (13, 15–19). One of the most debated topics is associated with the proton-conductance mechanism in the M2. Cross and coworkers (4, 10) proposed that the proton transfer occurs through the breaking and reforming of hydrogen bonds between His37 monomers, based on 15N chemical-shift measurements of His37 Nδ1 and Nε2 at different pH values in 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC)/1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylglycerol (DMPG) bilayers using magic-angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. They showed that His37 residues form low-barrier hydrogen bonds when the tetrad is in its +2 charge state. The measured chemical shifts led to three distinct pKa values for His37, i.e., 8.2, 6.3, and <5 (10).

On the other hand, Hong and coworkers (9, 20) ruled out the formation of the hydrogen bonds between two pairs of His37 dimers and, instead, suggested that the individual His37 residue shuttles protons via imidazole ring reorientations and exchanging protons with water. Their studies of the pH-dependent variation of 15N chemical shift resulted in four distinct pKa values of 7.6, 6.8, 4.9, and 4.2 in zwitterionic bilayers containing cholesterol. Despite the differences between these two sets of reported pKa values and their proposed mechanism (9, 10, 14), both indicate that the +3 charge state is the most conductive state among all. The discrepancy in the pKa values and 15N chemical-shift measurements could be due to the fact that the NMR spectra highly depend on the protein constructs and lipids used in sample preparation. For instance, it has been observed that there is a set of two resonances for His37 (implying the existence of a dimer of dimer conformation for the histidine tetrad) for M2 (residues 22 to 62) in 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC)/1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) lipids (21), M2 (residues 18 to 60) in 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC)/1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPhPC) (8, 22–24), and M2 full-length protein in both Escherichia coli and DOPC/DOPE membranes (25), while truncated M2 (residues 22 to 46) in viral-envelope-mimetic lipid membrane shows a different set of His37 resonances and does not show imidazole–imidazolium cross-peaks (9). Nevertheless, correlations between water and His37 imidazolium nitrogen has been shown by using the 1H–15N heteronuclear correlation spectra from either the M2 full-length in DOPC/DOPE (21) or the truncated M2 protein in viral-envelope-mimetic lipid membranes (9). Therefore, although the interpretation of these data resulted in different conductance mechanisms, they all agreed that water molecules are involved in proton conductance. Recently, conformational heterogeneity in the His37 tetrad has been observed, reflecting sophisticated chemistry associated with proton conductance. In this model, both imidazole–imidazolium hydrogen bonds and hydrogen bonds with water molecules are characterized. The conformational heterogeneity proposed in this study explains how waters/hydronium ions access the imidazole–imidazolium dimers and facilitate the cycling between charged states. In this model, the His37 residues in the +2 charge state distribute each charge over an imidazole–imidazolium dimer via hydrogen bonds. In the +3 charge state, His37 interacts with water to reduce the charge–charge repulsion, which results in proton shuttling across the membrane (19, 26).

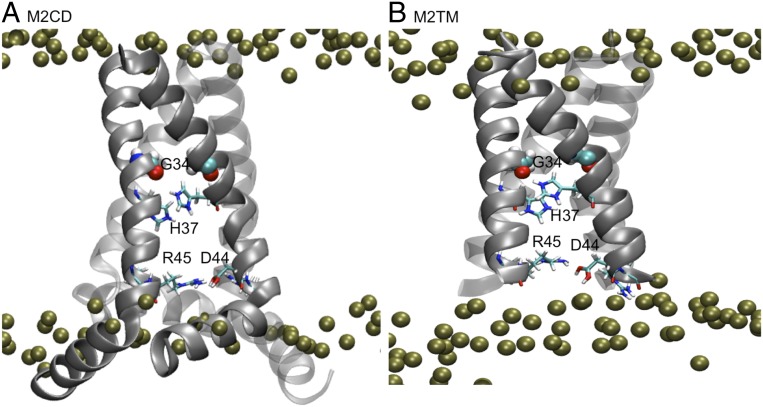

In addition, while these studies have provided valuable and detailed insights into the mechanism of the M2 proton current, they were mostly performed on constructs containing only the TM domain of the protein. However, comparison between the activities of constructs with different lengths of M2 indicates that, although the TM region (residues 22 to 46) alone forms a proton-selective channel and is responsible for conducting protons (M2TM), the rates of proton transport of various M2 constructs are within approximately a factor of two of the value for the full length (12, 27–30). This twofold difference in the proton-transport rate of the various M2 constructs has not been elucidated; however, it could be due to the differences in orientational preferences or differences in conductivity (27). The recent study by Hong and coworkers (12) suggests that the cytoplasmic tail facilitates protonation of His37 compared to that of the TM peptide. They attributed their observation to the acidity of the cytoplasmic domain, either directly by increasing the proton-transfer rate from water to the imidazole or indirectly by expanding the TM channel at His37. In addition, they showed that the His37 backbone conformation is more α-helical in the presence of the cytoplasmic domain compared to the TM peptide. Therefore, more studies of the full-length protein will clearly be desirable, especially to understand the role of the AH. It has been known that the AH domain of M2 is important for the stability and expression of the protein. Moreover, it has been shown that it plays a more active role in the pH-activation process by undergoing a conformational change and moving deeper into the bilayer in response to pH activation (12, 31). Therefore, the combination of the TM and AH regions, known as the conductance domain, is necessary to recover the full activity and maintain the functional integrity of the channel (M2 conductance domain [M2CD]) (12, 27, 31). In Fig. 1, we illustrate the structures that represent the M2CD and M2TM constructs explored in these earlier studies and herein.

Fig. 1.

Structure of M2. (A) M2CD construct (residues 22 to 62) contains TM and AH domains. (B) M2TM construct (residues 22 to 46) only contains TM domain. Phosphorous atoms of the lipid bilayer are presented in green van der Waals (VDW) spheres. His37, Asp44, and Arg45 are shown in licorice, and Gly34 is shown in VDW spheres.

Despite these observations, a recent study by Voth and coworkers (32) investigated the importance of including the amphipathic domain on the proton-conductance mechanism by performing molecular dynamics (MD) and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) studies on M2CD and M2TM constructs and suggested that the amphipathic domain doesn’t significantly change the structure of the TM domain and proton-conduction mechanism. The free-energy profiles (potentials of mean force [PMFs]) for proton transport through the channel were calculated for the +2 charge state of an M2CD construct (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID code 2L0J) and two different M2TM constructs (PDB ID codes 4QKL and 3LBW). The PMFs showed similar barriers around His37 for all three of these constructs, suggesting that the proton conductance was not affected significantly by initial structure (32). However, the conductance values calculated for proton transport showed that the conductance of one of the M2TM constructs (PDB ID code 4QKL; conductance = 7.7 fS) was approximately eightfold larger than that in the M2TM (PDB ID code 3LBW; conductance = 1.2 fS) and M2CD (PDB ID code 2L0j; conductance = 1.0 fS) constructs. Furthermore, the reported experimental values for conductance varied across a range of 0.4 aS to 4 fS under various conditions of pH and temperature (SI Appendix, Table S1). Also notable is that these studies only examined the +2 charge state of the His37 tetrad, where the system is dominantly the closed state. Although it has been shown that the pore radius increases around the His37 tetrad in the +2 charge state (33), further investigation is desirable for at least the +3 charge state, where the channel is open and has the maximum proton conductance (9, 10, 14). SI Appendix, Table S1 illustrates the measured or calculated proton conductance for different M2 constructs as reported in the literature (4, 27, 32, 34–38), illustrating that this property is highly sensitive to both the channel construct and conditions under which the measurements were made.

In addition to experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography and NMR, several MD studies have been performed on M2TM and M2CD constructs (6, 13, 15, 16, 35, 39–42). However, classical MD simulations have typically modeled only a single charge state at a time, and switching between different charge states whose population is supposedly a function of pH is not possible. Additionally, such studies do not typically consider protonation-state changes of other titratable residues in the protein. On the other hand, recently developed constant-pH MD (CpHMD) techniques have proven to be effective in studying pH-dependent processes without making a prior assumption on the charge state (43–50). In these methods, protonation states of the titratable residues are coupled with the system dynamics and are allowed to propagate through time. Therefore, the pKa values can be directly estimated from the free-energy difference between the different charge states at a given pH. Further detailed introduction on CpHMD methods and applications is presented in ref. 51; however, we note that there are two distinct approaches to CpHMD. In the discrete CpHMD methods developed by van Gunsteren et al. (52–54), the charge state of titratable residues is determined by performing several Monte Carlo (MC) steps along titration coordinates after a certain number of regular MD steps with fixed charges. One may note that the sudden change of charge state after performing the MC moves can lead to discontinuity in energy and forces. This issue is avoided in the continuous CpHMD method developed by Brooks and coworkers (55–57). In this technique, the titration coordinate propagates through time using a λ-dynamics approach, which provides a continuous switch between different charge states. The early implementation relied on an implicit representation of solvent (58, 59), which could potentially cause systematic errors in pKa calculations due to the known artifacts of the generalized Born models in aqueous systems (48, 60–62) and membrane proteins (63, 64). However, a recent implementation of CpHMD in the multisite λ-dynamics framework (CpHMDMSλD) (65, 66) allows the solvent to be explicitly represented, making this model particularly appropriate for studying membrane proteins.

Recently, Shen and coworkers (67) utilized the membrane-enabled hybrid-solvent CpHMD method with a pH replica exchange (pH-REX) sampling protocol to investigate the pH-dependent conformational dynamics of M2TM. Their work illustrates the conformational transition of M2TM as a function of pH; however, they only considered the TM domain and didn’t account for the effect of the AH domain on the conformational transition. In addition, there may be shortcomings due to limitations in the membrane implicit–solvent model employed for propagating titration coordinates and the high dielectric constant of water confinement inside of the channel, which is addressed by applying an explicit solvent model (67). More recently, Voth and coworkers (33) provided detailed information regarding the nature of the structure of the water molecules in different regions of the channel and emphasized that explicit water is necessary to include in simulations in order to capture the correlated changes. To this end, we have applied explicit solvent CpHMD using the multisite λ-dynamics approach (CpHMDMSλD) (65, 66) to the M2 construct containing the TM and AH domains (M2CD) (4), as well as the truncated M2 (M2TM). Our model provides a qualitative picture of pH-dependent conformational transitions in the M2 channel, reflecting the important role of the AH on this transition and, consequently, on the proton-transport mechanism.

Results

pKa Values and Charge States of the His37 Tetrad in M2CD and M2TM.

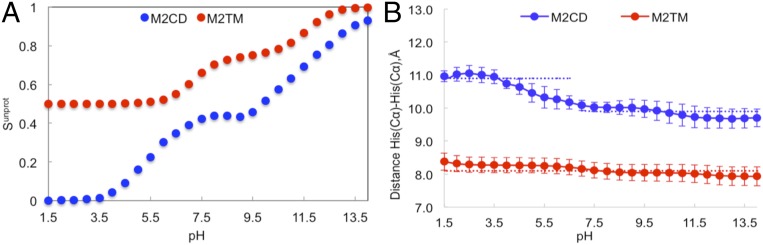

Replica exchange in pH with explicit solvent CpHMDMSλD for both M2TM and M2CD constructs was performed as described in Computational Methods. The unprotonated fraction of the His tetrad (Sunprot) for each replica was calculated and fitted to the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation (Eq. 2). Fig. 2A depicts the variation of Sunprot with pH for M2TM and M2CD. The resulting pKa values after fitting to Eq. 2 are listed in Table 1, along with experimental and other modeling values. Our calculated pKa values for M2CD (5.4, 7.0, 10.5, and 12.5) are numerically within the range of other measured or calculated pKa values, in particular, for the first and second pKa values. The third and fourth pKa values are 2 to 4 pKa units larger than their measured pKa values, respectively. This deviation may be due to differences in the membrane composition or, possibly, from incomplete convergence of our simulations. However, since these pKa values are above pH 7, they are expected to be fully populated in the protonated state and not affect the low-pH behavior. Our model suggests that the charge state of the histidine tetrad in M2CD changes from +4 to 0 as pH increases (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). In contrast, two pKa values in M2TM are dramatically shifted to lower values, indicating that the charge state of histidine residues only changes from +2 to 0 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). To probe the potential mechanism behind these distinct pKa values for the His37 tetrad in M2TM and M2CD, we turned to various trajectory analyses, such as hydrogen bonding, distance, tilt, and χ2 angle analysis.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of the His37 tetrad in the M2CD and M2TM constructs. Unprotonated fraction (Sunprot) (A) and the interhelical distance for histidine tetrad as a function of pH in M2TM and M2CD constructs (B). The dashed blue and red lines show the average values within the corresponded pH range.

Table 1.

pKa values of His tetrad from this study along with experimental/modeling results

| pKa | pH-REX (M2CD) | pH-REX (M2TM) | pH-REX (67) (M2TM) | Hong and coworkers (9) (M2TM) | Cross and coworkers (10) (M2TM) | Griffin and coworkers (8) (M2CD) | Hong and coworkers (12) (res. 21 to 97) |

| Explicit solvent model | Hybrid solvent model | ||||||

| Membrane | DOPC:DOPE | DOPC:DOPE | Implicit membrane | SM:DPPC: DPPE:Chol | DMPC:DMPG | DphPC:OG | SM:POPC: POPE:Chol |

| 1 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | <1 | 5.7 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | <5 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.4 |

| 2 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | <1 | 6.2 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 6.3 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.4 |

| 3 | 10.5 ± 0.3 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 7.1 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.02 |

| 4 | 12.5 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ± 0.1 | 8.3 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.02 |

Chol, cholesterol; res., residues; SM, sphingomyelin.

The M2 Conformational Transition Is Correlated with the Charge State of His37 in M2TM and M2CD.

The distance between the Cα of His residues in M2CD and M2TM constructs is presented in Fig. 2B. The Cα–Cα distance between His residues in M2CD decreased from 11.0 to 10.0 Å by increasing pH from 1.5 to 7, while it remained almost constant at pH values greater than 7 (∼9.9 Å). SI Appendix, Fig. S2 shows the relative orientation of the His37 tetrad in open and closed states. In contrast, the His(Cα)–His(Cα) distance in truncated M2 (M2TM) did not show the pH dependency, and the distance remained almost at 8.1 Å at all pH conditions. Furthermore, the number of water molecules and Cl− ions in the vicinity of the His37 (within 5 Å of the His37 tetrad) was calculated at different pH conditions for both M2TM and M2CD constructs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 and Movie S1). Movie S1 shows the conformational transition of M2 from low (pH 1.5) to high (pH 10) pH. Besides the small number of the water molecules in the channel of M2TM compared to M2CD, the number of water molecules in M2TM did not change in response to the pH change. In addition, there were no Cl− ions in the channel of M2TM, while 1 to 2 Cl− ions existed in the M2CD channel at low pH. The increase in the number of water molecules and Cl− ions in the M2CD construct at pH < 7.0 indicates that the channel is wide enough to accommodate these molecules. The presence of more water molecules around the His tetrad provides better solvation for the charged residues and perhaps facilitates the proton transfer. The existence of the counterions, which was shown by Klein and coworkers (68), could stabilize charged His and increase the proton-transfer barrier. Therefore, the presence of anions in the channel may play an important role in modulating proton current and preventing overacidification of the viral interior (68).

To further understand the effect of the charge state of the histidine tetrad on the size of the channel, we analyzed the pore radius of M2 in the M2CD and M2TM constructs using the HOLE2 program (69) (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5). At the 0 and +1 charge states of the M2CD construct, which are the dominant states at high pH values, the channel radius at His37 was too small to accommodate water molecules (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), indicating that the channel was in the closed state. However, as the charge increased to +2, the radius at His37 expanded slightly due to the repulsion between the charged His residues. Eventually, the channel was wide enough in the +3 charge state to allow water molecules to pass. Channel expansion was even more significant in the +4 charge state. In this state (pH < 4.5), the maximum distance (Fig. 2B) between charged His residues was achieved to ensure the lowest repulsion forces. In contrast, the channel radius at His37 in the M2TM construct indicated that the channel never expanded to be large enough to allow water molecules and even Cl− ions to pass (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). This was consistent with the number of Cl− ions and water molecules observed in the vicinity of the His37 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

This difference in the dynamics of the channel in the M2TM and M2CD constructs not only shows the important role of the amphipathic helices on the pH-dependent conformational changes of the channel, but also raises the question of whether these histidine residues in both constructs could form interhelical hydrogen bonds or whether they are only involved with hydrogen bonds to water molecules.

The Unique Behavior of His37 in the Heart of the Channel.

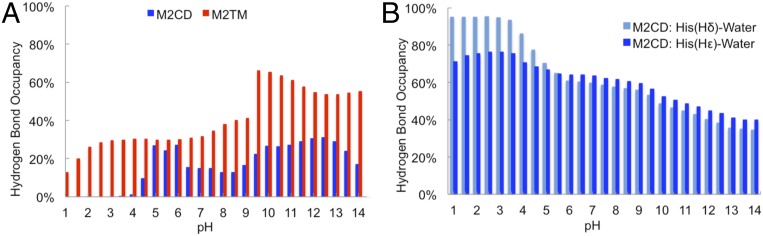

We examined hydrogen bonding to characterize the key interactions between the His37 residues. The hydrogen bond among the histidine residues (Fig. 3A) in M2TM largely existed at all pH values, which is consistent with the interhelical distance and the charge state of the histidine tetrad. Thus, M2TM appeared to be in a closed-like state, regardless of the pH condition of the environment. In M2CD, there was no hydrogen bond (<5% of the simulation time) between histidine dimers at pH lower than 4.5, where the histidine tetrad was in the +4 charge state. Around pH 5, when the first histidine deprotonated (pKa = 5.4), the occupancy of the hydrogen bond between the imidazole–imidazolium dimer slightly increased (∼30% of the simulation time). The hydrogen bond remained consistent (∼20% of the simulation time) between two histidine dimers when the third histidine titrated and the histidine tetrad was in its +2 charge state (pH 7.0 to 10.5).

Fig. 3.

The hydrogen-bond analysis. (A) Hydrogen bond between two pairs of histidine dimers in M2CD and M2TM constructs. (B) Hydrogen bond between Hδ and Hε of histidine residues and water molecules in M2CD constructs.

To resolve the competing views of the proton-conductance mechanism, we investigated the hydrogen bonds between histidine residues and water molecules (Fig. 3B). Although the hydrogen-bond occupancy between water molecules and histidine residues (with both Hδ and Hε) decreased by increasing pH, it was preserved for ∼50% of the simulation time at high pH. This decrease in the hydrogen-bond occupancy might be due to several factors, including the number of water molecules inside the channel (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), the histidine residues that become neutral/deprotonated, or the histidine dimers that are involved in imidazole–imidazolium hydrogen bonding in the +2 charge state. Nevertheless, we observed that the histidine residues can participate in hydrogen bonds with both water molecules and each other. This is consistent with the conclusion from the recent study by Cross and coworkers (19, 26), where they observed that histidine residues can participate in both types of hydrogen bonding. They suggested that the conformational heterogeneity of the histidine tetrad facilitates water access to the imidazole–imidazolium dimers and the cycling between different charged states.

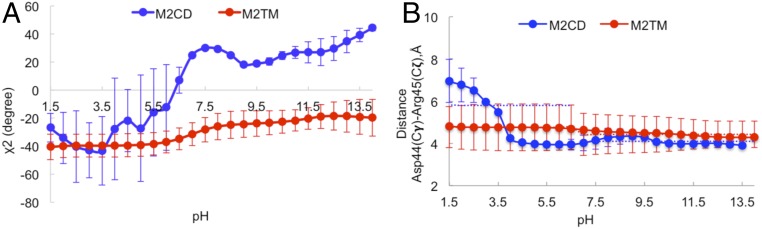

In addition, the formation of imidazole–imidazolium hydrogen bonds was highly sensitive to the orientation of His37 along Cβ–Cγ bond (χ2 angle). Therefore, we calculated the χ2 angle as a function of pH in M2TM and M2CD (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the χ2 angle in M2CD fluctuated dramatically at low pH, while above pH 7.0, where the histidine tetrad was at its +2 charge state, the χ2 angle remained largely steady. This implies that at high pH, where histidine dimers are involved in interhelical hydrogen bonding, they are in the locked (closed) state, and in the absence of the interhelical hydrogen bonds at low pH, the histidine residues can freely rotate along the Cβ–Cγ bond (open state). Movie S1 shows the dynamic character of His37 at low pH and that this rotation ceases at high pH, where the histidine residues are locked by interhelical hydrogen bonding. In contrast, the χ2 angle in the M2TM construct doesn’t change significantly compared to M2CD. This is consistent with the distance and hydrogen-bond analysis for truncated M2 and suggests that the channel doesn’t respond as readily to pH change.

Fig. 4.

Structural comparison of the M2TM and M2CD constructs. The χ2 angle for the histidine tetrad (A) and distance between Asp44 and Arg45 in M2TM and M2CD at different pH conditions (B) are shown.

Role of the M2 AH in Channel Dynamics.

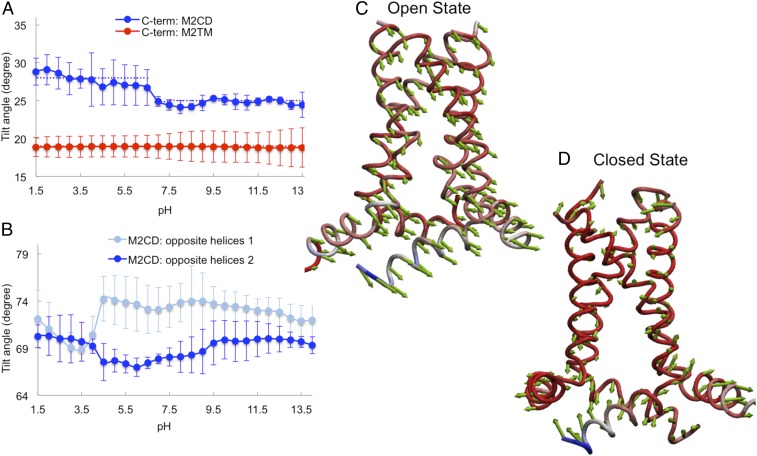

To further probe the AH domain role in proton conductance and channel structure, we focused on the tilt angle of the TM domain in M2TM and M2CD. The change in the tilt angle for the N-terminal (residues 22 to 33) and C-terminal (residues 35 to 46) portions of the TM domain for M2CD and M2TM are compared in SI Appendix, Fig. S6 and Fig. 5A, respectively. The change in the tilt angle of the N-terminal portion of the TM domain in the M2CD construct was negligible, while the tilt angle for the C-terminal portion decreased in response to high pH. This suggests that the bottom half of the channel, which is connected to the AH domain, is more dynamic and sensitive to pH change compared to the top half of the channel. This is consistent with the structural kink at Gly34 and the amantadine binding sites, which is observed in various studies (17, 18, 70, 71).

Fig. 5.

The effect of the amphipathic domain on conformational transition of M2CD construct. (A) Tilt angle of the C-terminal portion of the TM domain in M2CD and M2TM constructs. The dashed blue and red lines show the averaged value in the corresponding pH range. (B) Tilt angle of amphipathic helices. The values are averages over the two opposite helices. (C and D) The principal components of motion calculated using PCA in the open state (C) and the closed state (D) show the magnitude and direction of the TM and amphipathic helices’ mobility.

Besides His37, another titratable residue, which is located in the C-terminal portion of the TM domain, is Asp44. It has been suggested that Asp44 can form an interhelical salt bridge with Arg45 to stabilize the closed state at high pH. The calculated pKa values of Asp44 (SI Appendix, Table S2) showed that all four Asp44 residues at pH > 7.0 were deprotonated and therefore promoted the salt bridge with Arg45. This explains the dramatic decrease (∼2.0 Å) in the interhelical distance between Asp44 and Arg45 (Fig. 4B) from open to closed state. This salt bridge breaks at low pH, when Asp44 titrates and becomes protonated. This could be a driving force for closing/opening the channel at high/low pH. Movie S1 shows how Asp44 and Arg45 formed the salt bridge as pH increased. Comparing the pKa values of Asp44 and the change in the distances between Asp44 and Arg45 in truncated M2 (M2TM) indicated that Asp44 never titrated to the protonated (neutral) state; therefore, it preserved the salt bridge with Arg45 at all pH values, even at very acidic conditions. While this may be partially an artifact from the length of our simulations, it is indicative of the pKa shift and anticipated increased rigidity of the truncated M2TM construct. The difference in the protonation state of Asp44, the interhelical salt bridge with Arg45, and, consequently, the tilt angle of the C-terminal in M2TM and M2CD prompted the question of whether the AH could affect the TM domain conformation and proton-transport mechanism. Therefore, we studied the titratable residues located in amphipathic helices as well as the amphipathic helices’ orientation in the lipid bilayer to understand what is the driving force for this unique channel dynamics.

The principal components of the motions in the open and closed states of the M2CD construct were analyzed by using principal component analysis (PCA), calculated with the NMwiz plug-in in VMD (72, 73) (Fig. 5 C and D). These results show that the direction of the movement of all four amphipathic helices in the open state was correlated (Fig. 5C), while in the closed state, the movement of adjacent helices was anticorrelated (Fig. 5D). This indicates that the two opposing helices moved toward the solvent, while the other two moved away at high pH values. The normal-mode analysis using an anisotropic network model (ANM) (74, 75) also showed similar results, as illustrated in Movie S2, where the lowest-frequency mode for M2CD in the closed state, calculated by using the ANM function in VMD, is shown. This is consistent with the tilt angle of the amphipathic helices (with respect to the membrane normal [z axis]), which is shown in Fig. 5B. In this figure, we illustrate two sets of tilt angles corresponding to the two opposite helices (opposite helices I and II). The change in the tilt angle of the amphipathic helices was very similar at low pH, suggesting that the mobility of all four amphipathic helices is very similar when the channel is in the open state. However, the AH tilt angle changed in the opposite direction for adjacent helices at high pH (closed state). The pKa values of the titratable residues in the AH reflected this opposite movement of adjacent helices, in particular, His57 (SI Appendix, Table S2). The two highly upshifted pKa values (9.5 and 9.9) corresponded to the residues located on the helices that moved away from the solvent. In addition, the magnitude of the vectors in the PCA showed that the amphipathic domain was more dynamic compared to the TM domain in M2CD, particularly in the closed state. Together, these results suggest that the amphipathic helices adjusted their orientation in the membrane in order to ease the helix–helix packing and to accommodate the TM helices in the closed state.

To further understand the role of the AH domain on channel’s pH response, we performed long MD simulations (100 ns) on all predicted charge states of the M2TM and M2CD constructs. We manually changed the charge state of the His37 tetrad to +3 in the M2TM construct and performed the long MD simulations on this structure to investigate whether the channel expands. The channel perimeter around His37 (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) not only showed correlation with the charge state of the His37 tetrad in M2CD, but also indicated that the channel perimeter in the M2CD construct was significantly larger than that in the M2TM construct. Consistently, the His37 χ2 angle (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) and protein backbone rmsd values (SI Appendix, Fig. S9) showed large fluctuations in the M2CD construct compared to M2TM, suggesting that the truncated M2 was more rigid compared to M2CD construct. Altogether, our results imply that the M2 is more rigid in the absence of the amphipathic helices and that this may result in either a slower or a more difficult conformational transition from the closed to open state.

Discussion

The M2 conductance (M2CD: residues 22 to 62) and truncated M2 (M2TM: residues 22 to 46) constructs of the influenza A virus have been investigated with explicit solvent CpHMDMSλD to explore the proton-conductance mechanism and to understand the role of the amphipathic helices on channel-opening dynamics. The calculated pKa values combined with trajectory analyses portray a qualitative picture of how the conformational dynamics of the channel facilitate channel opening/closing. Our results show that the pKa values, and, hence, the interpretation of the ion-transport mechanism, critically depend on the protein construct. The calculated pKa values for histidine tetrad in M2CD are 5.4, 7.0, 10.5, and 12.5, corresponding to the four protonation steps. For pH values lower than 5.4; pH intervals of 5.4 to 7.0, 7.0 to 10.5, and 10.5 to 12.5; and pH higher than 12.5, the dominant charge states of the histidine tetrad are +4, +3, +2, +1, and 0, respectively. The +2 charge state dominates across the pH range of 7.0 to 10.5. This is consistent with the “histidine-locked” state proposed by Cross and coworkers (10). Indeed, the fact that the second and third pKa values are separated by nearly 4 pH units suggests how difficult it is to disrupt the stable histidine-locked conformation. The corresponding free energy to change the charge state of the histidine tetrads from +2 to +3 (ΔΔG+2→+3) and to disrupt the “histidine-locked” state is 4.76 kcal/mol. This is significantly larger than the ΔΔG+1→+2 = 2.17 kcal/mol and ΔΔG+3→+4 = 2.72 kcal/mol. In the truncated M2 (M2TM), the pKa values (<1, 7.0, and 10.7) indicate that the histidine tetrad charge state in this construct only changes from +2 to 0 with increasing pH on the time scale of our simulations.

The pKa differences between M2CD and M2TM, and, hence, different charge states for the histidine tetrad, reflect the important role of the amphipathic helices. We further correlated the conformational change of M2CD with the charge of the histidine tetrads by analyzing the interhelical distance and hydrogen bonding between the histidine tetrad. These results strongly correlate with the open (low-pH) and closed (high-pH) states in the M2CD construct, while the truncated M2 (M2TM) preserves the closed state at all pH conditions. We showed that the hydrogen bond within histidine dimers breaks at low pH. In the absence of the hydrogen bonds within the histidine dimers at low pH in M2CD, histidine residues appeared to assist the proton-shuttle mechanism by forming hydrogen bonds with water molecules. Although the occupancy of hydrogen bonds with water molecules decreased with increasing pH, it still existed under elevated-pH conditions. This is consistent with the recent study on the full-length M2 by Cross and coworkers (19, 26), where it was proposed that the histidine residues in the +2 charge state are involved with both interhelical hydrogen bonding and hydrogen bonds with water molecules. The conformational heterogeneity for the histidine tetrad has been introduced as a result of the variation in helix–helix packing and helix bending by using NMR spectroscopy that could facilitate water access to sequestered nitrogen sites in imidazole–imidazolium dimers and cycling between +2 and +3 charge states (19, 26). Additionally, we showed that the fluctuation of the histidine χ2 angles in M2CD, which can facilitate the proton-shuttle mechanism, ceases at high pH when the imidazole–imidazolium hydrogen bonds dominate.

We further examined whether the channel in the M2TM construct expands at its +2 charge state by performing long MD simulations (100 ns) on all charge states of both the M2TM and M2CD constructs. The His37 distance and χ2 angle analyses (SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8) confirmed that the truncated M2 (M2TM) preserves the closed state across all predicted His37 tetrad charge states, while the dynamics of the channel in the M2CD construct is correlated with its charge state. The results derived from these long MD simulations indicate that the M2TM construct is more rigid compared to the M2CD construct, and its rigidity results in a predominance of the closed state. SI Appendix, Fig. S9 shows the backbone rmsd values for the M2TM and M2CD constructs with various charge states for the His37 tetrad. The rigidity of the M2TM construct is reflected in the significantly depressed pKa values in the M2TM construct, and perhaps longer simulations are needed to capture the conformational transition in truncated M2. However, the conformational transition is recapitulated by the inclusion of the amphipathic helices, suggesting that the AH domain assists the channel expansion. This agrees well with the observations of Hong and coworkers (12), who suggest that the M2 cytoplasmic tail facilitates protonation of the His37.

Our investigations illustrated the important role of the amphipathic helices on the conformational transition of M2, and investigation of the dynamics of the amphipathic helices (tilt angle and PCA) provided a link between the conformational dynamics and channel opening/closing dynamics. The PCA shows that the amphipathic helices are more dynamic compared to the TM domain. Furthermore, this analysis combined with tilt angle calculations showed that the movement of the opposing amphipathic helices at high pH is correlated, while the adjacent helices move in an anticorrelated fashion. This could be due to the interaction of the amphipathic helices with the interfacial region of the lipid bilayer (4, 76). In particular, the existence of several titratable residues on the amphipathic helices, such as Glu56 and His57, can adopt different protonation states under different pH conditions to facilitate the channel dynamics. Comparison of the tilt angle of the N- and C-terminal portion of the M2CD and M2TM constructs clearly shows that the dynamics of the amphipathic helices affects the tilt angle of the C-terminal portion of the TM domain. The increase in the tilt angle for the C terminus at low pH, consistent with the pKa values of Asp44, leads to the breakage of the salt bridge between Asp44 and Arg45. Asp44 has been shown to be a critical and interesting residue (77–79); therefore, this detailed information about its protonation state in different M2 constructs could be important for further pharmacological, biochemical, and structural studies. Together, our results show that M2CD becomes activated at pH ∼7.0, which is consistent with experimental observations (pH ∼6.5) (14).

In summary, the pH-dependent structural perturbations in the M2CD and M2TM constructs of M2 proteins characterized here have not been investigated in prior studies of this protein (32, 67). Our explorations of the dynamics of the TM and amphipathic domain have led to rich details regarding the contributions of these elements to the function of this TM protein that we believe should fuel future experimental and theoretical research on this protein. It is important to emphasize that our investigation doesn’t imply that there is no proton conductance in the M2TM construct. In contrast, it shows that the inclusion of amphipathic helices could facilitate the channel expansion and proton conductance and suggests that the proton conductance in the M2TM construct might occur through other mechanisms. Finally, our study is a success story in applying explicit solvent CpHMDMSλD to achieve a detailed structural and functional understanding of a highly dynamic membrane protein. This study is important not only for influenza virology, but also for understanding other ion channels, such as voltage-gated proton channels.

Computational Methods

The M2CD construct was built starting from the deposited structural data from PDB ID code 2L0J (4). This structure was acetylated and amidated at the N and C termini, respectively, and was inserted in bilayers composed of a 4:1 ratio of DOPC:DOPE by using the CHARMM-GUI (80) server. For the M2TM construct, we used the same PDB structure and deleted the amphipathic helices (residues 47 to 62). Each system was solvated by using TIP3P water (81), and the number of Na+ and Cl− ions was chosen to match a concentration of 150 mM. The CHARMM36 (82) force field was used to represent the lipid molecules, and the CMAP-corrected CHARMM36 (83, 84) all-atom force field was applied to describe the proteins. The lipid bilayers were chosen to resemble previous studies (4). For all simulations, the SHAKE algorithm (85) was applied to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms, and a nonbonded cutoff of 12 Å was used with an electrostatic force switching (fswitch) and a van der Waals force switching (vfswitch) functions. The Leapfrog Verlet integrator was used with an integration time step of 1 fs. A Langevin thermostat with a frictional coefficient of 10 ps−1 was employed to maintain the temperature at 298 K. Equilibration simulations were performed on a graphics processing unit platform utilizing the CHARMM/OpenMM interface for 20 ns on both constructs with a charge state of 0 for the His37 tetrad (closed state), and the final structure was taken as the starting structure for pH-REX, which has been shown to improve the convergence of pKa calculations (47). The pH-REX simulation was performed by using CpHMDMSλD with the BLOCK (9) facility and the λNexp functional form with a coefficient of 5.5 (43). λ for each titratable site α (λα) was expressed in terms of virtual particles that propagate through time via a transformation to a constrained variable set (θα). Further discussions on different expressions of λα versus θα can be found in ref. 65. λα was used to linearly scale all nonbonded parameters; however, angles, bonds, and dihedral terms remained unaffected. For each site, λ values were saved every 100 steps. A total of 28 replicas were equally spaced between pH values of 1 to 14.5 with a 0.5 pH interval. The exchange between the neighboring replicas was attempted every 0.5 ps with an average acceptance rate above 40%. A fictitious mass of 12 amu⋅Å−2 was assigned to all θα. The production run was performed for 40 ns for each replica (cumulative time = 1.2 μs), and snapshots were saved every 1 ps. All parameters for the pH-REX simulations were kept as default values, as listed in ref. 43. States with λ ≥ 0.8 were considered as physical states and used for further analysis.

To calculate pKa values of His residues in the His tetrad, the fraction of unprotonated state (Sunprot) at a given pH was calculated as follows:

| [1] |

where Nunprot and Nprot are the sum of all unprotonated or protonated physical states (i.e., λ ≥ 0.8) of all four His residues in the His tetrad. The resulting Sunprot values versus pH were fitted to the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation:

| [2] |

The prefactor is a normalization constant. More discussion on Eq. 2 is presented in ref. 43.

The corresponding free energy (ΔΔG) for the charge-state change of the His tetrad was calculated by using pKa values:

| [3] |

In addition, the final structure of M2TM and M2CD extracted from replicas at different pH conditions corresponding to various charge states of the His37 tetrad were used as initial structures for classical MD simulations. The MD simulations were carried out for 100 ns for all nine structures (M2TM with +3, +2, +1, and 0 charge state and M2CD with +4, +3, +2, +1, and 0 charge state) with the same simulation conditions and criteria as the CpHMD simulation.

To study pH-dependent structural changes, the physical structures of M2CD and M2TM (λ ≥ 0.8) were extracted from different replicas at different pH values. We performed distance, hydrogen-bond, χ2-angle, and tilt-angle analysis to correlate the conformational dynamics with pKa and charge-state changes. The default criteria in CHARMM were used for hydrogen-bond analysis. We calculated the average pore radius at several points across the channel axis (z axis) using the HOLE2 (69) program. In addition, for each physical state at each replica, the number of water molecules and Cl− ions within 5 Å of the His tetrad were calculated. The principal components were calculated by using the PCA module within the NMwiz plug-in in VMD. PCA was done by using the diagonalized covariance matrix of the alpha carbon positions from each trajectory. The SDs in Figs. 2B, 4, 5 A and B, and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 were calculated over all trajectories and reflect the average over the individual helices as well. The 95% confidence coefficient was calculated for pKa values reported in Table 1 and SI Appendix, Table S2.

Data Availability.

Raw data files are available from the corresponding author upon fair request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grants GM103695, GM037554, GM107233, and GM130587.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1913385117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cady S. D., Luo W., Hu F., Hong M., Structure and function of the influenza A M2 proton channel. Biochemistry 48, 7356–7364 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liao S. Y., Fritzsching K. J., Hong M., Conformational analysis of the full-length M2 protein of the influenza A virus using solid-state NMR. Protein Sci. 22, 1623–1638 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinto L. H., Holsinger L. J., Lamb R. A., Influenza virus M2 protein has ion channel activity. Cell 69, 517–528 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma M., et al. , Insight into the mechanism of the influenza A proton channel from a structure in a lipid bilayer. Science 330, 509–512 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balannik V., et al. , Design and pharmacological characterization of inhibitors of amantadine-resistant mutants of the M2 ion channel of influenza A virus. Biochemistry 48, 11872–11882 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acharya R., et al. , Structure and mechanism of proton transport through the transmembrane tetrameric M2 protein bundle of the influenza A virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15075–15080 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cady S. D., et al. , Structure of the amantadine binding site of influenza M2 proton channels in lipid bilayers. Nature 463, 689–692 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colvin M. T., Andreas L. B., Chou J. J., Griffin R. G., Proton association constants of His 37 in the influenza-A M218-60 dimer-of-dimers. Biochemistry 53, 5987–5994 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu F., Schmidt-Rohr K., Hong M., NMR detection of pH-dependent histidine-water proton exchange reveals the conduction mechanism of a transmembrane proton channel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3703–3713 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu J., et al. , Histidines, heart of the hydrogen ion channel from influenza A virus: Toward an understanding of conductance and proton selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6865–6870 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang R., Li H., Swanson J. M., Voth G. A., Multiscale simulation reveals a multifaceted mechanism of proton permeation through the influenza A M2 proton channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9396–9401 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao S. Y., Yang Y., Tietze D., Hong M., The influenza M2 cytoplasmic tail changes the proton-exchange equilibria and the backbone conformation of the transmembrane histidine residue to facilitate proton conduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6067–6077 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou H. X., Cross T. A., Modeling the membrane environment has implications for membrane protein structure and function: Influenza A M2 protein. Protein Sci. 22, 381–394 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C., Lamb R. A., Pinto L. H., Activation of the M2 ion channel of influenza virus: A role for the transmembrane domain histidine residue. Biophys. J. 69, 1363–1371 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong M., DeGrado W. F., Structural basis for proton conduction and inhibition by the influenza M2 protein. Protein Sci. 21, 1620–1633 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J., Qiu J. X., Soto C., DeGrado W. F., Structural and dynamic mechanisms for the function and inhibition of the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21, 68–80 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekanayake E. V., Fu R., Cross T. A., Structural influences: Cholesterol, drug, and proton binding to full-length influenza A M2 protein. Biophys. J. 110, 1391–1399 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandala V. S., Liao S. Y., Kwon B., Hong M., Structural basis for asymmetric conductance of the influenza M2 proton channel investigated by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 429, 2192–2210 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miao Y., Fu R., Zhou H. X., Cross T. A., Dynamic short hydrogen bonds in histidine tetrad of full-length M2 proton channel reveal tetrameric structural heterogeneity and functional mechanism. Structure 23, 2300–2308 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong M., Fritzsching K. J., Williams J. K., Hydrogen-bonding partner of the proton-conducting histidine in the influenza M2 proton channel revealed from 1H chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 14753–14755 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Can T. V., et al. , Magic angle spinning and oriented sample solid-state NMR structural restraints combine for influenza a M2 protein functional insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9022–9025 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andreas L. B., Eddy M. T., Pielak R. M., Chou J., Griffin R. G., Magic angle spinning NMR investigation of influenza A M2(18-60): Support for an allosteric mechanism of inhibition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10958–10960 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andreas L. B., Eddy M. T., Chou J. J., Griffin R. G., Magic-angle-spinning NMR of the drug resistant S31N M2 proton transporter from influenza A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7215–7218 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andreas L. B., et al. , Structure and mechanism of the influenza A M218-60 dimer of dimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14877–14886 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miao Y., et al. , M2 proton channel structural validation from full-length protein samples in synthetic bilayers and E. coli membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 8383–8386 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin H., Miao Y., Cross T. A., Fu R., Beyond structural biology to functional biology: Solid-state NMR experiments and strategies for understanding the M2 proton channel conductance. J. Phys. Chem. B 121, 4799–4809 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma C., et al. , Identification of the functional core of the influenza A virus A/M2 proton-selective ion channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12283–12288 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duff K. C., Ashley R. H., The transmembrane domain of influenza A M2 protein forms amantadine-sensitive proton channels in planar lipid bilayers. Virology 190, 485–489 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossman J. S., Lamb R. A., Influenza virus assembly and budding. Virology 411, 229–236 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossman J. S., Jing X., Leser G. P., Lamb R. A., Influenza virus M2 protein mediates ESCRT-independent membrane scission. Cell 142, 902–913 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen P. A., et al. , pH-induced conformational change of the influenza M2 protein C-terminal domain. Biochemistry 47, 9934–9936 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang R., et al. , Acid activation mechanism of the influenza A M2 proton channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E6955–E6964 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watkins L. C., Liang R., Swanson J. M. J., DeGrado W. F., Voth G. A., Proton-induced conformational and hydration dynamics in the influenza A M2 channel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 11667–11676 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin T. I., Schroeder C., Definitive assignment of proton selectivity and attoampere unitary current to the M2 ion channel protein of influenza A virus. J. Virol. 75, 3647–3656 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson E., et al. , Functional reconstitution of influenza A M2(22-62). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 516–521 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moffat J. C., et al. , Proton transport through influenza A virus M2 protein reconstituted in vesicles. Biophys. J. 94, 434–445 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leiding T., Wang J., Martinsson J., DeGrado W. F., Arsköld S. P., Proton and cation transport activity of the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15409–15414 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mould J. A., et al. , Permeation and activation of the M2 ion channel of influenza A virus. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31038–31050 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khurana E., et al. , Molecular dynamics calculations suggest a conduction mechanism for the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1069–1074 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yi M., Cross T. A., Zhou H. X., Conformational heterogeneity of the M2 proton channel and a structural model for channel activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 13311–13316 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yi M., Cross T. A., Zhou H. X., A secondary gate as a mechanism for inhibition of the M2 proton channel by amantadine. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 7977–7979 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomaston J. L., et al. , High-resolution structures of the M2 channel from influenza A virus reveal dynamic pathways for proton stabilization and transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 14260–14265 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goh G. B., Hulbert B. S., Zhou H., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Constant pH molecular dynamics of proteins in explicit solvent with proton tautomerism. Proteins 82, 1319–1331 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goh G. B., Knight J. L., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Constant pH molecular dynamics simulations of nucleic acids in explicit solvent. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 36–46 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goh G. B., Knight J. L., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Towards accurate prediction of protonation equilibrium of nucleic acids. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 760–766 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goh G. B., Knight J. L., Brooks C. L. 3rd, pH-dependent dynamics of complex RNA macromolecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 935–943 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goh G. B., Laricheva E. N., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Uncovering pH-dependent transient states of proteins with buried ionizable residues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8496–8499 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arthur E. J., Yesselman J. D., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Predicting extreme pKa shifts in staphylococcal nuclease mutants with constant pH molecular dynamics. Proteins 79, 3276–3286 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panahi A., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Membrane environment modulates the pKa values of transmembrane helices. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 4601–4607 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panahi A., Bandara A., Pantelopulos G. A., Dominguez L., Straub J. E., Specific binding of cholesterol to C99 domain of amyloid precursor protein depends critically on charge state of protein. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 3535–3541 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen W., Morrow B. H., Shi C., Shen J. K., Recent development and application of constant pH molecular dynamics. Mol. Simul. 40, 830–838 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baptista A. M., Teixeira V. H., Soares C. M., Constant-pH molecular dynamics using stochastic titration. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 4184–4200 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bürgi R., Kollman P. A., Van Gunsteren W. F., Simulating proteins at constant pH: An approach combining molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo simulation. Proteins 47, 469–480 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mongan J., Case D. A., McCammon J. A., Constant pH molecular dynamics in generalized Born implicit solvent. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 2038–2048 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo Z., Brooks C. L. III, Kong X., Efficient and flexible algorithm for free energy calculations using the λ-dynamics approach. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 2032–2036 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knight J. L., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Lambda-dynamics free energy simulation methods. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 1692–1700 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kong X., Brooks C. L. III, λ‐dynamics: A new approach to free energy calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 105, 2414–2423 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khandogin J., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Constant pH molecular dynamics with proton tautomerism. Biophys. J. 89, 141–157 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee M. S., Salsbury F. R. Jr, Brooks C. L. 3rd, Constant-pH molecular dynamics using continuous titration coordinates. Proteins 56, 738–752 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khandogin J., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Toward the accurate first-principles prediction of ionization equilibria in proteins. Biochemistry 45, 9363–9373 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shen J. K., Uncovering specific electrostatic interactions in the denatured states of proteins. Biophys. J. 99, 924–932 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wallace J. A., Shen J. K., Continuous constant pH molecular dynamics in explicit solvent with pH-based replica exchange. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 2617–2629 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Choe S., Hecht K. A., Grabe M., A continuum method for determining membrane protein insertion energies and the problem of charged residues. J. Gen. Physiol. 131, 563–573 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Panahi A., Feig M., Dynamic Heterogeneous Dielectric Generalized Born (DHDGB): An implicit membrane model with a dynamically varying bilayer thickness. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 1709–1719 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Knight J. L., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Applying efficient implicit nongeometric constraints in alchemical free energy simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 3423–3432 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knight J. L., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Multi-site λ-dynamics for simulated structure-activity relationship studies. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 2728–2739 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen W., Huang Y., Shen J., Conformational activation of a transmembrane proton channel from constant pH molecular dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 3961–3966 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dong H., Fiorin G., DeGrado W. F., Klein M. L., Proton release from the histidine-tetrad in the M2 channel of the influenza A virus. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 12644–12651 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smart O. S., Goodfellow J. M., Wallace B. A., The pore dimensions of gramicidin A. Biophys. J. 65, 2455–2460 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paulino J., Pang X., Hung I., Zhou H. X., Cross T. A., Influenza A M2 channel clustering at high protein/lipid ratios: Viral budding implications. Biophys. J. 116, 1075–1084 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cady S. D., Hong M., Amantadine-induced conformational and dynamical changes of the influenza M2 transmembrane proton channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1483–1488 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bakan A., Meireles L. M., Bahar I., ProDy: Protein dynamics inferred from theory and experiments. Bioinformatics 27, 1575–1577 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.García A. E., Large-amplitude nonlinear motions in proteins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 2696–2699 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eyal E., Yang L. W., Bahar I., Anisotropic network model: Systematic evaluation and a new web interface. Bioinformatics 22, 2619–2627 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Atilgan A. R., et al. , Anisotropy of fluctuation dynamics of proteins with an elastic network model. Biophys. J. 80, 505–515 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tian C., Gao P. F., Pinto L. H., Lamb R. A., Cross T. A., Initial structural and dynamic characterization of the M2 protein transmembrane and amphipathic helices in lipid bilayers. Protein Sci. 12, 2597–2605 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schnell J. R., Chou J. J., Structure and mechanism of the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus. Nature 451, 591–595 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ma C., et al. , Asp44 stabilizes the Trp41 gate of the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus. Structure 21, 2033–2041 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rosenberg M. R., Casarotto M. G., Coexistence of two adamantane binding sites in the influenza A M2 ion channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13866–13871 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jo S., Kim T., Im W., Automated builder and database of protein/membrane complexes for molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS One 2, e880 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., Klein M. L., Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Klauda J. B., et al. , Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: Validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 7830–7843 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Foloppe N., MacKerell J., Alexander D., All‐atom empirical force field for nucleic acids: I. Parameter optimization based on small molecule and condensed phase macromolecular target data. J. Comput. Chem. 21, 86–104 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 84.MacKerell A. D. Jr, Feig M., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Improved treatment of the protein backbone in empirical force fields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 698–699 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ryckaert J.-P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H. J., Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: Molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23, 327–341 (1977). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data files are available from the corresponding author upon fair request.