Significance

Understanding of the shape-preserving crystallization from transient amorphous precursors to crystalline products in biomineralization makes it possible to produce topologically complex morphologies that defy crystallographic controls. Here we use in situ liquid-phase TEM, FTIR, and molecular dynamics simulations to investigate transformation of amorphous CaCO3 to crystalline phases in the presence of multiple additives. In situ observations reveal that Mg2+, which brings excess water into the bulk, is unique in initiating crystallization within the amorphous phase, leading to a shape-preserving transformation that is accompanied by dehydration. Simulation results find that the water accelerates ionic rearrangement within the solid phase, enabling the shape-preserving transformation. This in-depth understanding provides an alternative strategy for manufacturing crystals with arbitrary morphologies by design.

Keywords: crystallization, biomineralization, calcium carbonate, magnesium, morphology

Abstract

Organisms use inorganic ions and macromolecules to regulate crystallization from amorphous precursors, endowing natural biominerals with complex morphologies and enhanced properties. The mechanisms by which modifiers enable these shape-preserving transformations are poorly understood. We used in situ liquid-phase transmission electron microscopy to follow the evolution from amorphous calcium carbonate to calcite in the presence of additives. A combination of contrast analysis and infrared spectroscopy shows that Mg ions, which are widely present in seawater and biological fluids, alter the transformation pathway in a concentration-dependent manner. The ions bring excess (structural) water into the amorphous bulk so that a direct transformation is triggered by dehydration in the absence of morphological changes. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest Mg-incorporated water induces structural fluctuations, allowing transformation without the need to nucleate a separate crystal. Thus, the obtained calcite retains the original morphology of the amorphous state, biomimetically achieving the morphological control of crystals seen in biominerals.

Crystallization in nature often follows a multistep pathway (1) involving phase transformation from a transient amorphous precursor (2–4). Calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which is among the most abundant near-surface minerals and biominerals, is widely used as a model system to investigate fundamental aspects of crystallization in the context of both abiotic and biological mineralization (3, 5). Biomineral formation starting from amorphous CaCO3 (ACC) results in diverse morphologies including those of sea urchin spicules and teeth (6), nacre layers (7), and crustacean exoskeletons (8), which are strikingly distinct from the growth shapes of abiotic CaCO3 crystals. In these systems, amorphous nanoparticles are deposited within a vesicular space onto the surface of the growing biomineral where they transform to a crystalline material that is shape-preserving with the original ACC precursor and exhibits a microstructure reminiscent of aggregated particles (9, 10).

The transformation of biogenic amorphous phases is believed to be regulated by inorganic and organic components including Mg, phosphate, and carboxylated macromolecules, such as acidic proteins (8, 11–14). In particular, incorporation of Mg into biogenic calcites is common, and its presence is believed essential to stabilization of ACC (8, 13, 15) and inhibition of calcite (12, 16). However, the amorphous to crystalline transformation remains poorly understood (1, 4). Although some laboratory studies reported direct transformation (or solid-state transformation) of ACC to crystalline CaCO3 (17–19), most have concluded ACC transforms by dissolution–reprecipitation (1, 19–22). Moreover, few studies have been based on direct observation of the transformation and have instead relied upon either ex situ or bulk measurements, which are unable to relate the measured change in properties to the dynamics of individual particles. Consequently, knowledge of how impurities alter transformation pathways and the evolution of particle composition are largely unknown.

Here we take advantage of the ability of liquid phase TEM (LP-TEM) to follow mineral transformation processes of individual particles in real time (22, 23) in order to gain insight into the mechanism by which additives impact the transformation of ACC to crystalline products. LP-TEM has been used to investigate nanoparticle nucleation, growth, dissolution, and assembly of many materials including Pt (24, 25), Au (26, 27), Pd (28), Ag (29, 30), Cu (31), iron hydroxide (32), PbS (33), iron oxides (34), and CaCO3 (22, 23). These studies show that in situ observations by LP-TEM can provide high spatial and temporal resolution to directly observe the progress of phase transformations of individual particles. While we recognize that there are significant differences between the formation of minerals in the vesicles and membranes of organisms and the solution environment of a TEM sample cell, the results provide insights into physiochemically available mechanisms of transformation and the effect of impurities on those mechanisms.

Results and Discussion

In Situ Observation of Dissolution–Reprecipitation-Based CaCO3 Phase Transition.

We observed ACC crystallization in the presence of Mg2+, sodium citrate (Na-Cit), and sodium poly-acrylate (PAA), which were chosen to represent inorganic ions, small organic molecules, and macromolecules found in biomineralizing systems. To initiate the formation of ACC with known concentrations of the reagents, solutions containing 50 mM Ca2+ and HCO3− were deposited on the top and bottom chip of the TEM fluid cell, respectively. The additives were introduced with the Ca2+ reagent (see SI Appendix for details). Precipitation of CaCO3 was initiated by assembling the chips, and imaging was performed at a calibrated electron dose rate of 3.11 e/nm2s (see SI Appendix for details on calibration). This dose is low by the standards of LP-TEM and is considered to exert a limited influence on aqueous environments (35), having, for example, a negligible effect on metallic particle nucleation rates, which are highly sensitive to hydrated electron production, for time periods up to nearly 1,000 s (29).

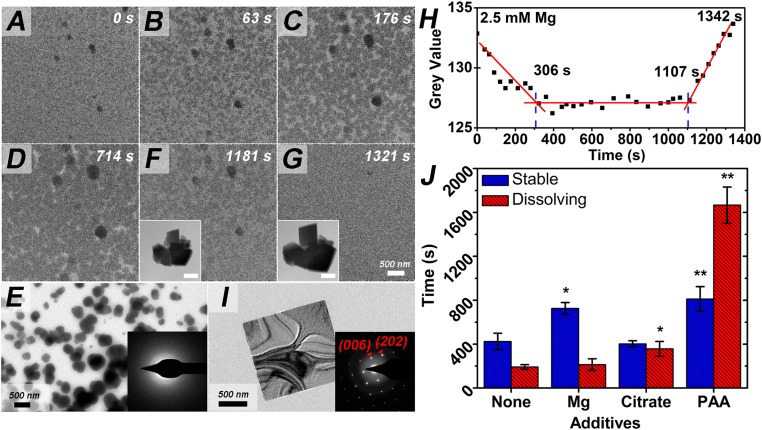

For low concentrations of Mg2+ (2.5 mM), Na-Cit (0.5 mM = 1.5 mM of carboxyl side groups), and PAA (250 μg/mL = 2.7 mM of acrylic acid monomers), 100 to 250 nm particles were present at 0 s (Fig. 1 A–D and SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S3) and, in the subsequent ∼300 s, grew continuously to ∼500 nm. These particles were identified as ACC via selected area electron diffraction (SAED) (Fig. 1E). Upon cessation of the growth stage, the ACC remained stable for times ranging from 400 to 800 s, after which it dissolved over periods of ∼200 to 1,600 s, depending on the type and concentration of the additive (Fig. 1 F and G and SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S3). The ACC lifetime and timescale for dissolution were quantified using average gray values of the TEM images (Fig. 1H and SI Appendix, Figs. S1B–S3B). During ACC dissolution, growth of crystalline CaCO3 could also be observed (Fig. 1 F and G, Insets, and I and SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5), demonstrating that dissolution–reprecipitation was responsible for the disappearance of ACC. Parallel experiments performed without an electron beam to exclude beam effects gave similar results (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Relative to additive-free solutions, all of the additives either increased ACC lifetimes (Mg2+), retarded calcite formation and ACC dissolution (Na-Cit), or both (PAA) (Fig. 1J).

Fig. 1.

Effect of additives on dissolution–reprecipitation kinetics observed by LP-TEM. (A–D, F, and G) Growth of ACC particles with 2.5 mM Mg2+ and their subsequent dissolution. All particles in the main panels are ACC. (Inset) In situ images of growing calcite particles. (Scale bars, Insets of F and G, 2 μm.) (E) Confirming existence of ACC particles on chips disassembled at ∼180 s. Inset in E and I shows SAED labeled with crystal planes. (I) Cuboidal calcite crystal formed by dissolution–reprecipitation on chips disassembled at ∼1,500 s. (H) Change of gray value of image with time showing periods of ACC growth, stability, and dissolution. Each square gives the gray value at the specified time and red lines show the trends in gray values during different time periods (A–D, F, and G). (J) The lifetime (labeled “Stable”) and dissolution period (labeled “Dissolving”) of ACC with the different additives. Additive concentrations were Mg2+, 2.5 mM; sodium citrate, 0.5 mM (1.5 mM of carboxyl groups); and PAA, 250 μg/mL (2.7 mM of acrylic acid monomers). The Student’s t test is used to analyze the statistical significance, and the P value was 0.016 (*P < 0.05) for lifetime of Mg2+; 0.019 (*P < 0.05) for dissolution period of citrate; 0.003 (**P < 0.01) for lifetime of PAA and 0.002 (**P < 0.01) for dissolution period of PAA.

Direct Transformation of CaCO3 Driven by Mg Incorporation.

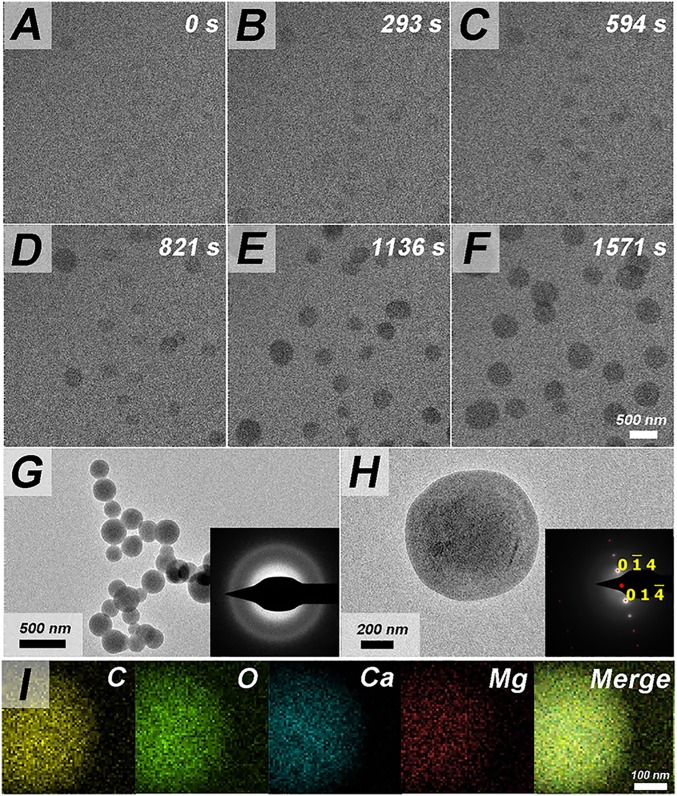

Upon increasing Na-Cit to 2.5 mM or PAA to 500 μg/mL, the observed behavior remained unchanged (Table 1). However, upon increasing Mg2+ concentrations to 5.0 or 7.5 mM, which is known to result in a concomitant increase in the Mg2+ content of the ACC (36), a different mechanism of ACC transformation was obtained: ACC particles initially exhibited low contrast that increased along with particle size (Fig. 2 A–G), and dissolution no longer occurred even after 1 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B). SAED analysis following disassembly of the TEM cell, as well as in situ, showed the particles had transformed into crystalline calcite with spheroidal morphologies (Fig. 2H and SI Appendix, Figs. S7 E and F, S8 A and B, and S9). Significantly, as a consequence of this direct transformation pathway, the number density of calcite particles after crystallization was ∼1,000 times higher with Mg (∼20 spheroidal calcite particles per 2 × 2 μm2; SI Appendix, Fig. S9A) than without (one calcite crystal per ∼14 × 14 μm2; SI Appendix, Fig. S4B).

Table 1.

Dominant transition pathway of ACC with different additives

| Additive | Concentration | Pathway | Stable (s) | Dissolving (s) |

| Mg2+ | 0.0 mM | D-R | 424 ± 75 | 192 ± 21 |

| 2.5 mM | D-R | 725 ± 54 | 213 ± 53 | |

| 5.0 mM | D-T | – | – | |

| 7.5 mM | D-T | – | – | |

| 25.0 mM | Beam effect* | – | – | |

| Sodium citrate | 0.5 mM (1.5 mM CG) | D-R | 402 ± 28 | 357 ± 67 |

| 2.5 mM (7.5 mM CG) | D-R | 428 ± 66 | 661 ± 77 | |

| 10.0 mM (30.0 mM CG) | Beam effect* | – | – | |

| Sodium poly-acrylate | 250 μg/mL (2.7 mM CG) | D-R | 812 ± 113 | 1,666 ± 165 |

| 500 μg/mL (5.4 mM CG) | D-R | 1,260 ± 145 | 4,431 ± 411 | |

| 750 μg/mL (8.1 mM CG) | Beam effect* | – | – |

D-R means dissolution-reprecipitation process, and D-T stands for direct transformation. Stable and dissolving represent the time periods of stability and dissolution for additive concentrations where dissolution–reprecipitation is observed. CG is the abbreviation for carboxyl groups.

For Mg, NaCit, and PAA concentrations of 25 and 10 mM and 750 μg/mL, respectively, the data were unreliable due to electron beam-induced dissolution (see SI Appendix for details).

Fig. 2.

In situ observations of direct ACC transformation in presence of 5 mM Mg2+. (A–F) Growth and direct transformation of ACC particles. (G) Confirming existence of ACC particles on chips disassembled at ∼180 s. (H) Formation of spheroidal calcite after the direct transformation on chips disassembled at ∼1,800 s. Inset in G and H shows SAED labeled with crystal planes. Typical simulated SAED for calcite is marked in red. (I) EDX analysis of spheroidal calcite after direct transformation showing the presence of Mg.

Parallel experiments performed without the electron beam excluded beam effects as the source of the altered transformation process (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A and C). Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) on a spheroidal calcite particle showed that the Mg present in the ACC remained in the solid after transformation (Fig. 2I and SI Appendix, Fig. S8C), and ∼23.8% Ca (mole ratio) was replaced by Mg. Moreover, the transformation process observed at high Mg levels was distinct from the direct transformation pathways reported previously for Mg-free solutions (22), in which nucleation of crystalline phases occurred at the ACC particle surface, the spherical morphology of the original particles was rapidly lost, and the emerging crystalline particles exhibited the expected morphology for the specific crystalline phase. Consequently, we conclude that the introduction of Mg2+ at concentrations of ≥5.0 mM switches the ACC-to-calcite transition pathway from dissolution–reprecipitation to a shape-preserving direct transformation.

In Situ Analysis of Structural Evolution During the Direct Transformation.

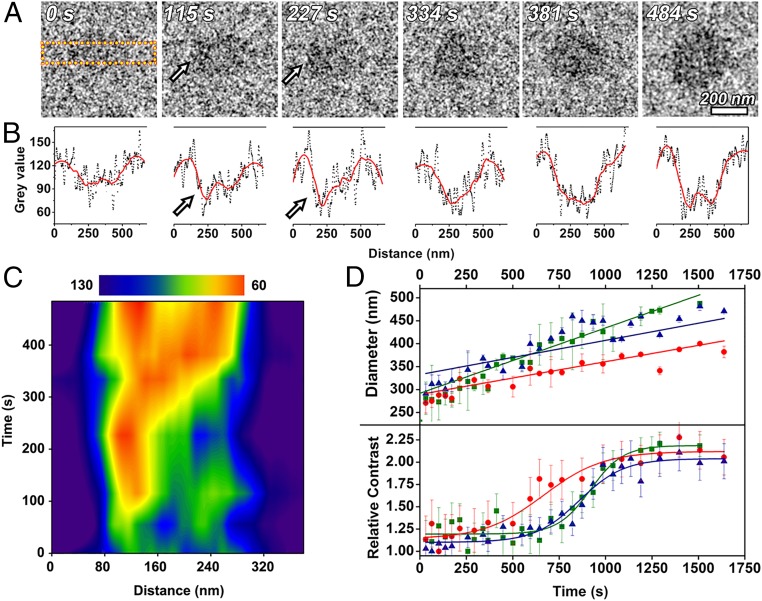

To obtain structural details about the transformation, ideally, in situ SAED or lattice fringe analysis would be used (22, 23). However, the electron beam doses required for these methods were too large to avoid significant beam effects. Thus, we followed the development of electron contrast under the low-dose conditions used for imaging. While the overall electron contrast of each particle increases with time, a sharp change in contrast begins at a specific location in each particle and then spreads throughout (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

In situ TEM analysis of direct transformation of CaCO3 in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+. (A) Transformation of a single particle. (B) Gray values of CaCO3 particles in A acquired from area between yellow dashed lines. Red lines are smoothed data. Arrows in A mark locations at which contrast begins to increase and correspond to arrows in B. (C) Distribution of gray values in B changes with time, indicating increase in area of high contrast region. (D) Size and contrast analysis for three different particles, which are represented by circles, squares, and triangles, respectively.

The specimen affects both the amplitude and phase of the electron beam, leading to the formation of amplitude contrast (including mass–thickness contrast and diffraction contrast) and phase contrast, respectively. Although both types of contrast commonly contribute to an image, specific conditions can cause one type to dominate. As discussed in detail in SI Appendix, mass–thickness contrast was the major contrast observed in our TEM experiments. The mass–thickness contrast Φ is influenced by mass and density effects on Rutherford scattering (SI Appendix) (37):

| [1] |

where N0 is Avogadro’s number, Qatom is cross section for scattering per atom, ρ is density, ∆D is thickness, and A is atomic weight.

While ρ should increase during the ACC to calcite transition, particle diameter also increased with time during the transition (Figs. 2 A–F and 3A). We cannot say with certainty whether the thickness increased as well, but to get a conservative estimate of the change in contrast, we first assume the particles remain spherical, i.e., they thicken as much as they expand laterally. Thus, the contrast change was influenced by both ∆D and ρ. To separate out the effects, we calculated the relative contrast (∆Φ):

| [2] |

where the argument 0 refers to the initial values (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Table S1). Consequently, under the assumption that the particles are spherical throughout the experiment, the results demonstrate that particle sizes grew linearly throughout the transition from ∼350 to 400 nm while the relative contrast exhibited an S-shaped curve with an increase from about 1.17 to 2.20 occurring between 400 and 1,300 s. Thus, the increase in relative contrast is due to increasing density during the direct transformation.

From Eq. 2 and the changes in relative contrast and particle size, which were acquired from the fits to the data in Fig. 3D, we obtain an average density change for all particles of ρ(t)/ρ(0) = 1.57 ± 0.08. (The error here arises from averaging over the values for multiple particles rather than signal-to-noise seen in the contrast for any one particle.) If, in fact, the particles are only expanding laterally and are not thickening, then the measured density change increases from 1.57 to 1.79. The reported densities of hydrated ACC and calcite are 1.62 and 2.75 g/cm3, respectively (38). Considering that MgCO3 has a higher density than CaCO3, the assumed density of the final calcite particles, which contain ∼23.8% Mg, should be higher than that of calcite. Using a linear interpolation gives a corrected density of 2.8 g/cm3, or ρMg-calcite/ρACC = 1.7. This ratio is within 5 to 8% of the measured value, further supporting the conclusion that Mg2+ induces a direct transformation from ACC to Mg-calcite.

Smeets et al. (39) used cryoTEM to show that under the conditions used in their experiments, the first particles of calcium carbonate were, in fact, a dense liquid phase (DLP). They quantified the difference in contrast between the DLP, the solution, and crystalline CaCO3. The magnitude of the contrast change seen here is significantly less—2.2 vs. 3.5—indicating that the ACC particles, by the time we detected them, were already less hydrated and not of the DLP. However, the ACC particles are almost certainly more hydrated in solution than in the dry state. Bolze et al. (38) found that the density of ACC in solution is 1.62 g/cm3, while Fernandez-Martinez et al. (40) obtained a density for dry ACC powder of 2.18 g/cm3. As the density measured by Bolze et al. is nearly the same as what we obtain from the change in contrast, “a hydrated ACC particle” is the accurate description of the Mg-ACC in this system. Whether in this state the particles exhibit mechanical properties consistent with a solid, a gel, or a dense liquid is unknown.

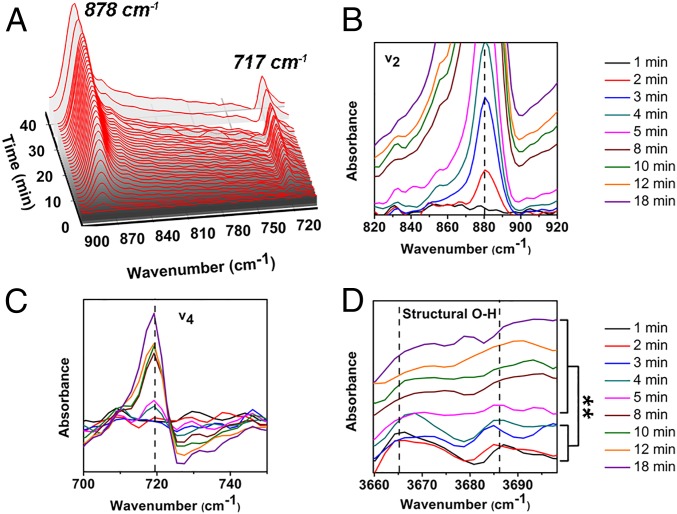

We related the observed density changes to the development of crystallinity using in situ attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) on identical solution compositions to follow the evolution of CaCO3 spectral features (Fig. 4A) (12). In-growth of the two primary calcite peaks at 720 and 880 cm−1, which appear within 2 to 4 min, dominates the time evolution of the spectrum (Fig. 4 B and C). The v4 peak that appears at 720 cm−1 is also indicative of high Mg doping in calcite (12). However, during the first 4 min we also observed out-growth of two previously unreported peaks at 3,600 to 3,700 cm−1 associated with structural water in minerals (Fig. 4D) (41). By ∼5 min, the signals of structural water were no longer observable while the calcite peaks continued to grow. In complementary experiments using 25 mM Mg2+ to amplify the water loss, thermogravometric analysis (TGA) showed >20% loss by mass, with loss continuing beyond 250 °C (SI Appendix, Fig. S10A). These TGA results reinforce the conclusion from the ATR-FTIR data that the Mg-ACC particles contain structural water. In contrast, TGA data on ACC prepared without Mg2+ exhibited a loss of <15% with negligible dehydration occurring beyond 250 °C (SI Appendix, Fig. S10B). Notably, previous work by Blue et al. (42) also observed a correlation between Mg2+ content and the water within ACC.

Fig. 4.

In situ ATR-IR analysis of CaCO3 direct transformation in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+. (A) In situ ATR-FTIR analysis confirming transition from ACC to calcite. (B–D) Detailed in situ ATR-FTIR spectrum of CaCO3. (B) v2 asymmetric bending. (C) v4 symmetric bending. (D) Structural water. The peak areas before and after 4 min at 3,665 and 3,685 cm−1 are compared, respectively. The Student’s t test is used to analyze the statistical significance, and the P value was 0.006 (**P < 0.01) for 3,665 cm−1 and 0.007 (**P < 0.01) for 3,685 cm−1.

Understanding the Role of Mg in Altering the Mechanism of Phase Transformation.

The above findings show that high Mg2+ incorporation drives transformation to Mg-calcite within the bulk of hydrated ACC particles, with the transformation front propagating through the particle as the water is expelled and the material densifies, leaving the amorphous morphology intact. However, the results do not provide insights into the separate roles of incorporated Mg2+, water, and free Mg2+ in driving this pathway. Previous research showed that Mg2+ ions can inhibit calcite crystal growth via two main pathways: 1) incorporation of Mg2+, leading to a lower supersaturation of calcite by increasing the mineral solubility (11), and 2) the adsorption of Mg2+ on step-edges or terraces of calcite, decreasing the velocity of migrating steps likely due to slower ion desolvation (43, 44). Other studies showed that water is a key factor in enabling crystallization and reorientation of ACC (45–48). Indeed, TGA data (SI Appendix, Fig. S10) prove that Mg2+ incorporation increases the water content of ACC. Thus, either Mg2+ or water or the combination of both could affect the crystallization pathway.

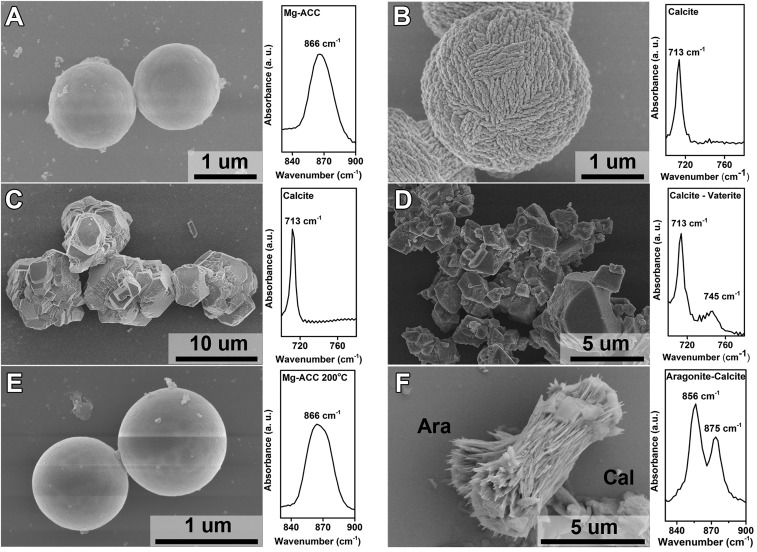

The shape-preserving manner of the direct transformation enabled us to determine the importance of incorporated Mg, incorporated water, and free Mg2+ in driving that pathway. Spherical Mg-ACC particles were first precipitated in the presence of 25 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 5A). When left in 25 mM Mg2+ aqueous solution, spherical calcite was obtained, indicating a direct transformation (Fig. 5B). In contrast, when the Mg-ACC particles were precipitated in 25 mM Mg2+ aqueous solution and quickly centrifuged and redispersed in pure water, large faceted calcite particles were formed in place of the Mg-ACC or spherical Mg-calcite (Fig. 5C), indicating dissolution–reprecipitation dominated. Similarly, when pure ACC particles (without Mg doping) were placed into 25 mM Mg2+ solution, faceted calcite particles with sporadic vaterite were generated (Fig. 5D). Notably, the calcite in Fig. 5C is more spheroidal than is that in Fig. 5D. We assume that direct transformation of the ACC begins to occur within the particle due to the Mg2+ doping, but due to a lack of Mg2+ in solution the dissolution–reprecipitation that is usually inhibited when Mg2+ is present happens synchronously. Thus, the small morphological difference is observed. Finally, when spherical Mg-ACC was heated to 200 °C to remove the ∼16% incorporated water (Fig. 5E) and then placed in 25 mM Mg2+ solution, only needle-like aragonite was obtained (Fig. 5F), again implying a dissolution–reprecipitation pathway. Thus, we conclude that all three components are necessary for the direct transformation to take place: incorporated Mg2+, incorporated water, and free Mg2+.

Fig. 5.

Understanding the role of free Mg2+, doped Mg, and water on crystallization of ACC by SEM and FTIR. (A) Precipitation of spherical Mg-ACC in the presence of 25 mM Mg2+. (B) Crystallization of Mg-ACC to spherical calcite in the presence of 25 mM free Mg2+. (C) Crystallization of Mg-ACC to calcite without Mg2+ in solution. (D) Precipitation of ACC without Mg2+. In the subsequent phase transition stage, Mg2+ was added to maintain 25 mM free Mg2+ in solution. (E) Heating the Mg-ACC in A at 200 °C for 20 min. The dried CaCO3 was still amorphous with a spherical shape. (F) The dried Mg-ACC in E was crystallized to aragonite (Ara) and calcite (Cal) in the presence of 25 mM free Mg2+ in solution.

From the data on ACC lifetime (Fig. 1H), the known inhibition of calcite crystallization by free Mg2+ (12, 45), and the observation that in the absence of free Mg2+, Mg-ACC is replaced by faceted calcite, the role of Mg2+ is clear. First, in its absence, ACC is kinetically stabilized due to the long incubation time for nucleation of calcite in solution. However, once calcite forms in solution, it consumes the dissolved ions as it grows, reducing the activity product toward the solubility of calcite. Once the activity product drops below the solubility limit of ACC, the ACC begins to dissolve. In contrast, when Mg2+ is present, two changes take place. First, Mg2+ inhibits the nucleation of calcite in solution thus increasing the lifetime of the ACC, even at low Mg2+ concentrations (Fig. 1H). This longer lifetime then combines with the second effect of Mg2+, which is to destabilize the ionic network and enhance ionic reconfigurations, to drive calcite nucleation within the Mg-ACC particle instead of the surrounding solution. Then the dehydration–transformation front must reach the surface of the Mg-ACC particle and come in contact with surrounding solution before it can begin to deplete the dissolved ions through growth. As long as the dehydration–transformation front moves through the entire particle too rapidly for significant dissolution to occur following first contact of the front with the solution, the particle will remain largely intact. The specific and relative roles of incorporated Mg and incorporated water are less clear. Moreover, whether the water must be part of the ACC structure or only the amount of water in the ACC matters is uncertain. However, based on the observations above, we hypothesize that Mg2+, which is a strongly hydrated ion, brings additional water into the ACC (45), and the water provides the molecular mobility needed to nucleate calcite within the Mg ACC particles.

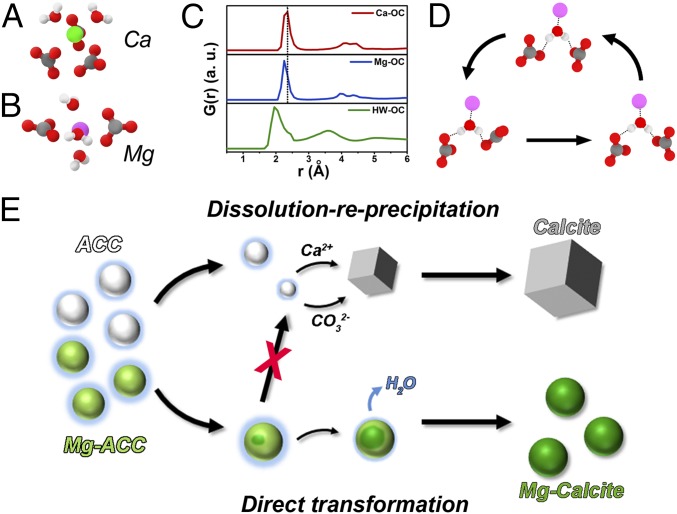

To test the hypothesized function of Mg2+ and water in the transformation process and understand whether the water plays a structural role, we employed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to examine the structural dynamics of ACC and Mg-ACC clusters for a range of Mg concentrations. ACC clusters were generated from Ca2+/Mg2+ and CO32− solutions by a procedure which was used to minimize the artificial influence on the initial structure of the ACC clusters (refer to simulation details of SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Specifically, we placed the solutions between two walls which only allowed water molecules to pass. The free water and weak-binding water passed through the walls, leaving behind the ions and strongly binding water, which constitute the ACC/Mg-ACC clusters. These clusters were subsequently used as the initial configurations for the final production simulations. Both sets of simulations were carried out using previously developed potentials (49–51).

This approach produced clusters that could be reasonably assumed as representative of those formed in the experiments. For example, according to the results from the TGA experiments, ACC has ∼15 wt % water content, and Mg-ACC with 23.8% Mg doping has ∼20 wt % water content. In our simulations, the Mg-free ACC clusters contained ∼16.1 wt % water, while the Mg-ACC clusters into which Mg was doped at 20 wt % had a water content of ∼19.6 wt %, in good agreement with experiments. Moreover, the atomic configurations obtained in the simulations could be reasonably taken as reflective of isolated regions within larger ACC particles because the Mg-ACC cluster contained about 3 times as many ions and molecules (800 Ca2+ plus Mg2+, 800 CO32−, and 840 to 1,400 water molecules) than used in previous published simulations (800 ions and molecules in total) (51).

The structural dynamics of the resulting ACC clusters were evaluated by examining the radial distribution function (RDF) profiles, residence times, and coordination numbers between the ion pairs in ACC clusters. The MD results predict that, due to its high dehydration barrier, Mg2+ brings additional water into ACC (Fig. 6 A and B and SI Appendix, Tables S2 and S3). The results also predict that the water molecules, which form hydrogen bonds to CO32−, are relatively unstable sites in the ionic-binding network. This is seen by comparing the sharpness of the peaks in the RDF profiles, which depends on the binding energies (SI Appendix). The peaks representing cation–OC binding, though different in position due to the smaller size of Mg2+ ion than Ca2+, are both sharp, implying strong binding affinities between CO32− and both Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the RDF profile of H2O–OC exhibits two broad overlapping peaks, indicating weak binding between water and CO32−, which establishes a weak point in the ionic-binding network of the ACC cluster that results in stronger ionic rearrangements for Mg-ACC than ACC (Fig. 6D). This greater propensity for rearrangement is reflected in the residence times of water molecules around CO32− (HW–CO32−), Ca2+ (OW–Ca2+), and Mg2+ (OW–Mg2+), which rank in the order of Mg2+ >> Ca2+ >> CO32− (SI Appendix, Table S4). The fact that strong cation–anion bonds are partially replaced by weak, unstable H bonds between H2O and CO32− indicates that some of the water has a role in the structure of the ACC at least some of the time (Fig. 6 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S12). More importantly, the weak H2O–OC binding and high rate of HW–CO32− rearrangement in the water-rich Mg-ACC implies an enhanced probability for nucleation of a crystalline phase within the particle.

Fig. 6.

Mechanism of Mg2+ regulation of ACC phase transition pathway. Atomic configuration details around (A) Ca2+ and (B) Mg2+ in MD simulation (Ca2+, green sphere; Mg2+, purple sphere; H2O, red/white; CO3, gray/red). (C) Radial distribution function (RDF, G(r)) between positively and negatively charged atoms showing broadened peak for H atoms of water and O atoms of CO3 (Ca, Ca2+; Mg, Mg2+; OC, O atoms in CO32−; HW, H atoms of water). (D) Local binding network of water molecules in simulated ACC. The H bonds between water molecules and CO32− are unstable, easily breaking and regenerating spontaneously. (E) Two pathways of ACC phase transformation regulated by Mg2+. Without Mg2+, ACC typically follows a dissolution–recrystallization pathway to form rhombohedral calcite. However, in the presence of Mg2+, nucleation of calcite occurs within the ACC and is accompanied by dehydration. As a result, a direct transformation is achieved in the absence of morphological changes.

These conclusions are consistent with recent results based on coherent X-ray and incoherent neutron scattering demonstrating that the presence of Mg2+ in ACC can increase the content of both mobile and rigid water, leading to a higher frequency of structural rearrangements within the mineral (52), although the authors attributed the behavior to stress effects. Yang et al. (53) found that Mg-ACC actually consists of two types of carbonates, amorphous CaCO3 and amorphous MgCO3. Using quasi-elastic neutron scattering, Jensen et al. (54) recently observed that water diffuses in amorphous MgCO3 with similar dynamics to that found for water in clays, although they did not report higher water mobility in Mg-ACC than in pure ACC. All these results are consistent with the conclusion that incorporation of Mg2+ into ACC introduces relatively unstable sites in the ACC structure, increasing the possibility of ion rearrangement, thus enhancing the probability of structural transformations. With regard to the finding that a direct transformation process dominates in the presence of high Mg content, most previous studies indeed found that free Mg2+ inhibits nucleation of calcite in solution, thereby decreasing the crystallization rate during the dissolution-reprecipitation process, but the applicability of the findings to the direct transformation process investigated here is unclear. Moreover, previous work has shown that extremely high Mg2+ concentrations can initiate transformation of ACC to aragonite either in simulated sea water (55) or in solution containing a high content of polymer (56). Whether the mechanism reported here still dominates is unknown.

Dissolution–reprecipitation and direct transformation can be understood as two competitive pathways, with the dominant pathway dependent on the site of nucleation: nucleation of calcite in solution leads to dissolution–reprecipitation, while nucleation within ACC particles initiates a direct transformation. Commonly, the mobility of ions in solution is much higher than in the solid; thus, nucleation in solution is much more rapid. However, the presence of Mg2+ in CaCO3 solutions lowers the supersaturation with respect to calcite by increasing the mineral solubility (11). In addition, the adsorption of Mg2+ onto the surfaces of calcite blocks its growth (43, 44). In contrast, Mg2+ brings more water into ACC, increasing the nucleation rate in (or on) the solid. Moreover, the additional structural water that Mg2+ introduces into Mg-ACC likely makes it less soluble than pure ACC (52). Consequently, once the concentration of Mg2+ reaches a certain level (5 mM for our experimental conditions), nucleation from ACC happens before nucleation from solution, causing the direct transformation to dominate (Fig. 6E).

Conclusions

The findings reported above reveal that, while for pure solutions and most additives investigated here, ACC transformation into calcite is dominated by dissolution–reprecipitation, doping of Mg2+ into ACC increases the water content, weakens the ionic-binding network, and leads to a direct transformation in the absence of morphological changes (Fig. 6E). In addition, Mg inhibits the nucleation of calcite within the bulk solution, leading to an increase in the period of stability (11, 43, 44). Thus, Mg2+ plays two roles: 1) It decreases the supersaturation of the solution with respect to calcite, as well as the crystal growth rate, leading to the inhibition of the dissolution-reprecipitation pathway and increasing the time available for direct transformation. 2) It acts as a carrier to bring excess structural water into ACC, generating relatively unstable sites that promote the transformation, as proposed previously (46, 57). The results also show that direct transformation of ACC is a condensation process accompanied by dehydration. As a result, the Mg is retained within the particle, leading to formation of Mg-calcite. This outcome stands in stark contrast to previous findings showing Mg2+ is lost during ACC transformation via dissolution–reprecipitation (36) and suggests a plausible reason why Mg is such a common impurity in biominerals (8, 11, 13, 15, 58). Moreover, the direct transformation is shape-preserving, implying that Mg doping is potentially exploited by organisms to assist in formation of curved, noncrystalline forms commonly seen in natural biominerals (2, 6, 12, 15, 58). Because the morphological characteristics of materials endow them with specific functions (59, 60), the ability to control material morphology is an important goal in material science. Previous work has shown that amorphous precursors are moldable (61). The findings reported here demonstrate a potential method for initiating a shape-preserving direct transformation in such precursors. Consequently, our results point toward a process that directly transforms an amorphous precursor to a crystalline phase without morphological changes, providing a viable route to manufacturing crystals with arbitrary morphologies—especially with curved surfaces—by design.

Methods

TEM Liquid Cells.

Liquid cell chips (Hummingbird Scientific) similar to those described previously were used for LC-TEM observation (22). Briefly, the liquid cell consists of two square 4 mm2 silicon chips with 50 nm thick silicon nitride membranes in 30 × 200 µm2 windows for imaging. Each chip has eight Au pads with a thickness of 500 nm, and the chips were aligned with the pads were on the internal faces to create a space for particle growth. All of the chips were plasma cleaned in a Plasma Cleaner (Harrick Plasma) for 30 s prior to use by bleeding in 200 to 400 mTorr of ambient atmosphere.

Sample preparation.

Different from previous LC-TEM experiments on CaCO3 crystallization, the dual flow method was not used here owing to the uncertainty of the resulting ion concentrations, which was an important parameter to fix in investigating the influence of additives. Instead, a static method was applied by placing 100 mM CaCl2 (with or without additives) and NaHCO3 solution separately on different liquid cell chips and assembling the chips to start the precipitation of ACC. Although this method can miss the earliest moments of ACC nucleation, the phase transition from ACC to crystalline polymorph could be easily captured at fixed and known solution conditions.

Typically, after the chips were cleaned, 0.6 μL of the abovementioned CaCl2 solution (with or without additives) was placed on one chip, while 0.6 μL of 100 mM NaHCO3 aqueous solution was placed on the other one. Then the chips were quickly assembled inside the liquid cell holder (Hummingbird Scientific) to check the vacuum seal. Posttest, the samples were immediately put into TEM for observation, with the time between chip assembling and observation being within 5 min.

Electron Microscopy.

Electron microscopy was conducted in a field emission FEI Tecnai G2 F20 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated at 200 kV. Snapshots were captured by an Eagle CCD (1,024 × 1,024 pixels), which was controlled from the Tecnai User Interface (TUI), and snapshots were further processed using the TEM Imaging & Analysis (TIA) interface.

Different from previous LC-TEM observation on particle nucleation (22, 23), the crystallization from ACC to crystal required a longer time, especially when additives stabilized the ACC phase. To minimize beam effects a low electron dose rate was used to observe the phase transition.

In order to control the electron dose rate, we used the same TEM observation conditions (including condenser aperture, spot size, magnification, C2 lens, etc.) for every experiment. We chose a diameter of 50 μm for the second condenser aperture. The spot size was 6. In order to increase the mass–thickness contrast, an objective aperture of 35 μm was used. The measurements were made with a blank holder under same observation condition, as well as with the liquid cell chips in the holder for comparison. The dose rate after correcting for the measured calibration factor was 3.11 e/nm2s with a blank holder; thus, the electron dose in our experiments was no more than 3.11 e/nm2s, which was 100 times smaller than previous work on the observation of calcium carbonate. As a result, the exposure time for each acquisition was prolonged to 2 s to obtain adequate contrast while keeping the total electron dose at low values. We confirmed that this was a suitable dose for observing the phase transition with negligible impact on the timescale of transformation events, as discussed in SI Appendix.

Scanning electron microscopy images were acquired by a field emission SU-8010 (Hitachi) operated at 5 kV.

ATR-IR Measurements.

The precipitation of Mg-ACC was monitored over time using a Bruker Alpha Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer equipped with a Harrick ConcentratIR sampling accessory with a diamond attenuated total reflectance (ATR) sampling plate. For each FTIR spectrum recorded, 16 scans were made at a resolution of 2 cm−1. All samples were made by mixing equal volumes of calcium solution (100 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2) and bicarbonate solution (100 mM NaHCO3). The backgrounds were determined using 50 mM NaHCO3 solution. The first spectrum was recorded ∼10 s after mixing the solutions and the rest of the spectra were recorded at the defined time intervals.

Data Availability.

The detailed description of the experiment and experimental data are available in the manuscript and SI Appendix. In situ LP-TEM files are available in the Zenodo repository (http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3609354).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Soltis and Guomin Zhu for TEM assistance and Yueqi Zhao for SEM assistance. We also thank Fan Yang, Jiajun Chen, and Boyan Li for help. Materials synthesis, ATR-IR spectroscopy and electron microscopy were supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES), Division of Materials Science and Engineering, Synthesis and Processing Sciences Program at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). Analysis of TEM and TGA data and MD simulations were supported by the International Exchange Program of Zhejiang University, National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 21625105, 21805241, and 11904300), the Fujian Provincial Department of Science & Technology (Grant 2017J05028), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant 20720180018), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grants 2017M621909 and 2018T110585). ATR-IR measurements were performed at the Environmental and Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a DOE Office of Science User Facility at PNNL sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research. In situ TEM capability development was supported by the Materials Synthesis and Simulation Across Scales Initiative through the Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program at PNNL. PNNL is a multiprogram national laboratory operated for Department of Energy by Battelle under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: In situ LP-TEM files have been deposited in the Zenodo repository (http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3609354).

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1914813117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.De Yoreo J. J., et al. , CRYSTAL GROWTH. Crystallization by particle attachment in synthetic, biogenic, and geologic environments. Science 349, aaa6760 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addadi L., Raz S., Weiner S., Taking advantage of disorder: Amorphous calcium carbonate and its roles in biomineralization. Adv. Mater. 15, 959–970 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gower L. B., Biomimetic model systems for investigating the amorphous precursor pathway and its role in biomineralization. Chem. Rev. 108, 4551–4627 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartwright J. H., Checa A. G., Gale J. D., Gebauer D., Sainz-Díaz C. I., Calcium carbonate polyamorphism and its role in biomineralization: How many amorphous calcium carbonates are there? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 11960–11970 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morse J. W., Arvidson R. S., Lüttge A., Calcium carbonate formation and dissolution. Chem. Rev. 107, 342–381 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Politi Y., Arad T., Klein E., Weiner S., Addadi L., Sea urchin spine calcite forms via a transient amorphous calcium carbonate phase. Science 306, 1161–1164 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nassif N., et al. , Amorphous layer around aragonite platelets in nacre. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12653–12655 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao J., Zhou D., Zhang Z., Xu X., Tang R., Magnesium-aspartate-based crystallization switch inspired from shell molt of crustacean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 22096–22101 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Politi Y., et al. , Transformation mechanism of amorphous calcium carbonate into calcite in the sea urchin larval spicule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17362–17366 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Killian C. E., et al. , Mechanism of calcite co-orientation in the sea urchin tooth. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 18404–18409 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis K. J., Dove P. M., De Yoreo J. J., The role of Mg2+ as an impurity in calcite growth. Science 290, 1134–1137 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loste E., Wilson R. M., Seshadri R., Meldrum F. C., The role of magnesium in stabilising amorphous calcium carbonate and controlling calcite morphologies. J. Cryst. Growth 254, 206–218 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang D., Wallace A. F., De Yoreo J. J., Dove P. M., Carboxylated molecules regulate magnesium content of amorphous calcium carbonates during calcification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21511–21516 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong Y. U., et al. , Phase transitions in biogenic amorphous calcium carbonate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 6088–6093 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raz S., Weiner S., Addadi L., Formation of high‐magnesian calcites via an amorphous precursor phase: Possible biological implications. Adv. Mater. 12, 38–42 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meldrum F. C., Hyde S. T., Morphological influence of magnesium and organic additives on the precipitation of calcite. J. Cryst. Growth 231, 544–558 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pouget E. M., et al. , The development of morphology and structure in hexagonal vaterite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11560–11565 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ihli J., et al. , Dehydration and crystallization of amorphous calcium carbonate in solution and in air. Nat. Commun. 5, 3169 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gal A., et al. , Calcite crystal growth by a solid-state transformation of stabilized amorphous calcium carbonate nanospheres in a hydrogel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 4867–4870 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assaf G., et al. , Particle accretion mechanism underlies biological crystal growth from an amorphous precursor phase. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 5420–5426 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Q., et al. , The thermodynamics of calcite nucleation at organic interfaces: Classical vs. non-classical pathways. Faraday Discuss. 159, 509 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen M. H., Aloni S., De Yoreo J. J., In situ TEM imaging of CaCO3 nucleation reveals coexistence of direct and indirect pathways. Science 345, 1158–1162 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smeets P. J., Cho K. R., Kempen R. G., Sommerdijk N. A., De Yoreo J. J., Calcium carbonate nucleation driven by ion binding in a biomimetic matrix revealed by in situ electron microscopy. Nat. Mater. 14, 394–399 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng H., et al. , Observation of single colloidal platinum nanocrystal growth trajectories. Science 324, 1309–1312 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuk J. M., et al. , High-resolution EM of colloidal nanocrystal growth using graphene liquid cells. Science 336, 61–64 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye X., et al. , Single-particle mapping of nonequilibrium nanocrystal transformations. Science 354, 874–877 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loh N. D., et al. , Multistep nucleation of nanocrystals in aqueous solution. Nat. Chem. 9, 77–82 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin B., et al. , Revealing the cluster-cloud and its role in nanocrystallization. Adv. Mater. 31, e1808225 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woehl T. J., Evans J. E., Arslan I., Ristenpart W. D., Browning N. D., Direct in situ determination of the mechanisms controlling nanoparticle nucleation and growth. ACS Nano 6, 8599–8610 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutter E., et al. , In situ liquid-cell electron microscopy of silver-palladium galvanic replacement reactions on silver nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 5, 4946 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson M. J., Tromp R. M., Vereecken P. M., Hull R., Ross F. M., Dynamic microscopy of nanoscale cluster growth at the solid-liquid interface. Nat. Mater. 2, 532–536 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu K., et al. , Bubble nucleation and migration in a lead-iron hydr(oxide) core-shell nanoparticle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 12928–12932 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans J. E., Jungjohann K. L., Browning N. D., Arslan I., Controlled growth of nanoparticles from solution with in situ liquid transmission electron microscopy. Nano Lett. 11, 2809–2813 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li D., et al. , Direction-specific interactions control crystal growth by oriented attachment. Science 336, 1014–1018 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider N. M., et al. , Electron-water interactions and implications for liquid cell electron microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 22373–22382 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blue C. R., et al. , Chemical and physical controls on the transformation of amorphous calcium carbonate into crystalline CaCO3 polymorphs. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 196, 179–196 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter C. B., Williams D. B., Transmission Electron Microscopy (Springer-Verlag, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolze J., et al. , Formation and growth of amorphous colloidal CaCO3 precursor particles as detected by time-resolved SAXS. Langmuir 18, 8364–8369 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smeets P. J. M., et al. , A classical view on nonclassical nucleation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E7882–E7890 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez-Martinez A., Kalkan B., Clark S. M., Waychunas G. A., Pressure-induced polyamorphism and formation of ‘aragonitic’ amorphous calcium carbonate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 8354–8357 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madejová J., FTIR techniques in clay mineral studies. Vib. Spectrosc. 31, 1–10 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blue C., Dove P., Chemical controls on the magnesium content of amorphous calcium carbonate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 148, 23–33 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutjahr A., Dabringhaus H., Lacmann R., Studies of the growth and dissolution kinetics of the CaCO3 polymorphs calcite and aragonite. 2. The influence of divalent cation additives on the growth and dissolution rates. J. Cryst. Growth 158, 310–315 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanzaki N., Onuma K., Treboux G., Tsutsumi S., Ito A., Inhibitory effect of magnesium and zinc on crystallization kinetics of hydroxyapatite (0001) face. J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 4189–4194 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Politi Y., et al. , Role of magnesium ion in the stabilization of biogenic amorphous calcium carbonate: A structure−Function investigation. Chem. Mater. 22, 161–166 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ihli J., Kulak A. N., Meldrum F. C., Freeze-drying yields stable and pure amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC). Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 49, 3134–3136 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jensen A., et al. , Hydrogen bonding in amorphous calcium carbonate and molecular reorientation induced by dehydration. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 3591–3598 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albéric M., et al. , The crystallization of amorphous calcium carbonate is kinetically governed by ion impurities and water. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 5, 1701000 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen J. W., Li C., Van Der Vegt N. F., Peter C., Understanding the control of mineralization by polyelectrolyte additives: Simulation of preferential binding to calcite surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 6904–6913 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raiteri P., Gale J. D., Quigley D., Rodger P. M., Derivation of an accurate force-field for simulating the growth of calcium carbonate from aqueous solution: A new model for the calcite−Water interface. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 5997–6010 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomono H., et al. , Effects of magnesium ions and water molecules on the structure of amorphous calcium carbonate: A molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 14849–14856 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koishi A., et al. , Role of impurities in the kinetic persistence of amorphous calcium carbonate: A nanoscopic dynamics view. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 16983–16991 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang S. Y., Chang H. H., Lin C. J., Huang S. J., Chan J. C., Is Mg-stabilized amorphous calcium carbonate a homogeneous mixture of amorphous magnesium carbonate and amorphous calcium carbonate? Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 52, 11527–11530 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jensen A. C. S., Rodriguez I., Habraken W. J. E. M., Fratzl P., Bertinetti L., Mobility of hydrous species in amorphous calcium/magnesium carbonates. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 19682–19688 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun W., Jayaraman S., Chen W., Persson K. A., Ceder G., Nucleation of metastable aragonite CaCO3 in seawater. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 3199–3204 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheng X., Varona P. L., Olszta M. J., Gower L. B., Biomimetic synthesis of calcite films by a polymer-induced liquid-precursor (PILP) process: 1. Influence and incorporation of magnesium. J. Cryst. Growth 307, 395–404 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raiteri P., Gale J. D., Water is the key to nonclassical nucleation of amorphous calcium carbonate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 17623–17634 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Polishchuk I., et al. , Coherently aligned nanoparticles within a biogenic single crystal: A biological prestressing strategy. Science 358, 1294–1298 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mann S., Behrens P., Bäuerlein E., Handbook of Biomineralization: Biomimetic and Bioinspired Chemistry (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeom B., et al. , Abiotic tooth enamel. Nature 543, 95–98 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cölfen H., Antonietti M., Mesocrystals and Nonclassical Crystallization (John Wiley & Sons Ltd., West Sussex, 2008). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The detailed description of the experiment and experimental data are available in the manuscript and SI Appendix. In situ LP-TEM files are available in the Zenodo repository (http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3609354).