Abstract

Terlipressin is a commonly used drug in hepatology practice for the two most serious complications of cirrhosis, that is, acute oesophageal variceal bleed and hepatorenal syndrome. Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a medical emergency and is frequently associated with acute kidney injury (AKI). Two male patients with alcohol-induced ACLF with high MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) score presented with AKI. Both were treated with terlipressin infusion. There was no response to terlipressin in these sick patients, and further both patients developed ischaemic skin necrosis and succumbed to multiorgan failure. Continuous infusion of terlipressin is superior to bolus dosing, but we noted that continuous infusion might as well be associated with severe adverse effects in patients with a high MELD score. More extensive prospective studies, including patients with high MELD score, are required to ascertain the safety of terlipressin.

Keywords: alcoholic liver disease, dermatological, unwanted effects/adverse reactions, acute renal failure

Background

Acute variceal bleed (AVB) and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) are serious complications of cirrhosis.1 Terlipressin (also known as triglycyl lysine vasopressin) is a synthetic analogue of the neuropeptide hormone vasopressin and a prodrug for lysine vasopressin. Terlipressin has been approved as a first-line drug for the management of AVB and HRS.1 However, the safety of terlipressin remains a concern, which is the reason for its non-availability in some countries. Here we report two patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) awaiting liver transplant who developed terlipressin-induced ischaemic skin necrosis, along with a review of published case reports.

Case presentation

The first case is a 54-year-old chronic alcoholic who presented with complaints of jaundice for 1 month and abdominal distension for 15 days. He also complained of decreased urine output for 2 days. He had no significant personal or family history of any illness. Clinically he was icteric, had hepatosplenomegaly, and ascites on abdomen examination.

The second case is a 45-year-old chronic alcoholic man with no significant personal or family history of any illness who presented with complaints of jaundice and ascites for 20 days. On examination, he was deeply icteric, and had tense ascites and hepatomegaly (8 cm below the right costal margin).

Investigations

In case 1, investigations revealed serum creatinine of 3.2 mg/dL with serum total bilirubin of 18.6 mg/dL and International Normalized Ratio (INR) of 2.1. The patient also had hypoalbuminaemia (albumin of 2.7 g/dL). Sepsis (serum procalcitonin, blood and urine cultures) screening was negative.

In case 2, investigations revealed a haemoglobin of 96g/L, bilirubin of 21.4 mg/dL, INR of 1.9 and creatinine of 2.3 mg/dL.

Differential diagnosis

Both patients had organ failure (liver and renal) and satisfied the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver and the European Association for the Study of the Liver criteria for ACLF.2 3

Treatment

In case 1, the patient was started on albumin infusion. Despite 60 g of albumin (1 g/kg), he had progressive acute kidney injury (AKI) and was hence started on terlipressin 2 mg/day on continuous infusion after 48 hours.

In case 2, the patient was resuscitated with intravenous albumin at 1 g/kg dose. Sepsis was ruled out, and he was started on terlipressin at 2 mg/day infusion at 48 hours as there was no decline in creatinine (2.2 mg/dL at 48 hours).

Outcome and follow-up

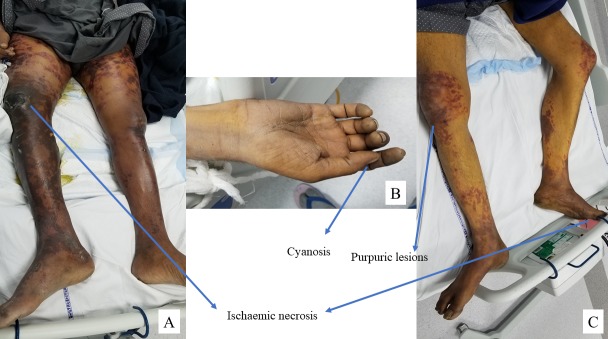

In case 1, we noted extensive skin necrosis on the lower limbs with a gangrenous lesion on the right knee on day 5 of terlipressin therapy, and terlipressin was withheld (figure 1A). He had worsening kidney functions despite changing to octreotide and midodrine, and later required renal replacement therapy. He succumbed to multiorgan failure on day 16 of admission.

Figure 1.

(A) Ischaemic necrosis on the lower limbs in case 1. (B) Cyanosis of the upper limb in case 2. (C) Cyanosis of the toes and necrotic purpuric lesions on the lower limbs in case 2.

In case 2, the patient developed cyanosis of the upper hands and diffuse ischaemic purpuric lesions on the lower limbs 2 days after terlipressin infusion (figure 1B, C), with creatinine reaching 2.5 mg/dL. Hence terlipressin was changed to octreotide and midodrine. However, he developed pneumonia and succumbed to multiorgan failure on day 21.

Discussion

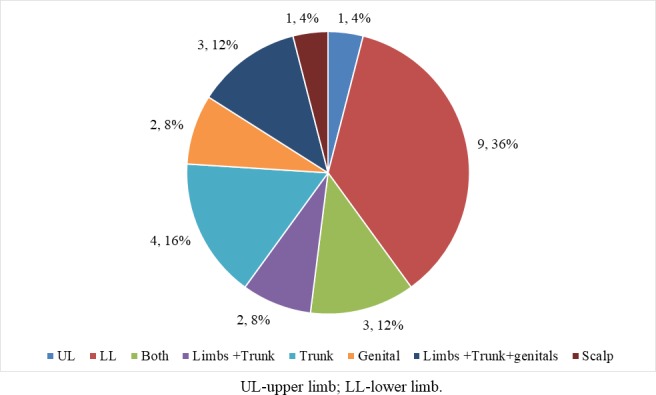

Terlipressin is an approved drug for AVB and HRS. However, there are case reports of terlipressin causing skin necrosis and gangrene (table 1).4–22 Nineteen articles reporting a total of 25 patients were analysed. Of these patients, 80% were male and the mean age was 58.88±12.36 years. MELD (Model for End-StageLiver Disease) score was reported in 11 patients, and the mean MELD score was 21.18±8.08. The most common aetiology of liver cirrhosis was ethanol in 52%, followed by viral in 16% and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in 12%. Twenty per cent of the total had vascular comorbidity (hypertension or cardiovascular disease) and 16% had diabetes mellitus. Indication for using terlipressin was HRS in 64% and variceal bleed in 36%. Terlipressin dosing was reported in 24 patients. Eighty-four per cent (21 patients) had received bolus dosing compared with only three who received continuous infusion. The mean dose in the continuous arm was much higher than in the bolus arm (continuous: 8.34±2.33 mg/day; bolus: 5.05±0.58 mg/day; p=0.07). However, the time to the development of side effects was similar in both groups (continuous: 2.95±0.48; bolus: 2.67±0.88; p=0.82). The most common site was the lower limbs (figure 2). A total of 72% of patients who developed ischaemic side effects succumbed to the disease.

Table 1.

Published case reports to date on terlipressin-induced ischaemic side effects

| Reference | Authors | Aetiology | Age/sex | Indication | Comorbidities | Dose | MELD score | Time to side effects (days) | Site | Others | Mortality |

| 4 | Chiang et al 4 | Alcohol | 65/M | HRS | Hypertension | 2 mg every 6 hours for 48 hours, and then 1 mg every 6 hours. | 28 | 3 | Fingers, toes, area around the umbilical hernia and scrotum. | – | No |

| 5 | Iglesias Julián et al 5 | HCV | 84/F | AVB | Hypertension, chronic renal failure and auricular fibrillation | 1.5 mg 4 hourly. | 1 | Hypogastrium, flanks and periareolar regions. | No | ||

| 6 | Sarma et al 6 | Alcohol | 65/M | AVB | DM | 1 mg 6 hourly. | NA | 2 | Bilateral upper and lower limbs. | Yes | |

| 7 | Herrera et al 7 | Alcohol | 55/M | HRS | Ischaemic haemorrhage/subarachnoid haemorrhage | 1 mg 4 hourly. | 29 | NA | Lower extremities, buttocks, back and abdomen. | Yes | |

| 8 | Ozel Coskun et al 8 | NASH | 65/M | AVB | Obesity, IHD, hypertension | 1 mg 4 hourly. | 10 | 2 | Skin of the right forearm and hand. | – | No |

| 9 | Sundriyal et al 9 | Alcohol | 47/M | AVB | – | 1 mg 6 hourly. | 3 | Skin of bilateral lower limbs. | – | NA | |

| 10 | Lee and Oh10 | Alcohol + HCV | 71/M | HRS | Prior pulmonary tuberculosis | 1 mg intravenously 4 hourly. | 25 | 11 | Legs and toes. | Osteomyelitis | No |

| 11 | Taşliyurt et al 11 | (A) Alcohol | 79/M | HRS | 1 mg intravenously 4 hourly. | NA (bilirubin NA) | 2 | Scrotum. | – | Yes | |

| (B) HBV | 65/M | HRS | 1 mg intravenously 4 hourly. | NA (bilirubin NA) | 2 | Scrotum. | – | Yes | |||

| 12 | Yefet et al 12 | Alcohol | 66/M | AVB | Obesity, IHD, DM, CKD | 2 mg intravenously 4 hourly, 48 hours. 1 mg intravenously 4 hourly, 24 hours. |

NA | 3 | Skin of thigh, calf and abdomen epidermolysis. | – | Yes |

| 13 | Chandail and Jamwal13 | (A) Cryptogenic | 47/M | HRS | Obesity | 0.5 mg 6 hourly. | NA | 2 | Skin of bilateral lower limbs and toe gangrene. | – | Yes |

| (B) NASH | 53/F | HRS | Obesity | – | 5 | Abdominal wall and thighs. | – | Yes | |||

| (C) Alcohol | 41/M | AVB | – | 1 mg 6 hourly. | 3 | Posterior of the thighs and legs. | No | ||||

| 14 | Bañuelos Ramírez et al 14 | Alcohol | 51/F | AVB | CKD | 4 mg/day. | NA | 3 | Legs and toes. | No | |

| 15 | Elzouki et al 15 | Cryptogenic | 52/M | AVB | DM, hypothyroidism | 4 mg stat f/b 2 mg intravenously 6 hourly. | 12 | 2 | Bilateral upper and lower limb fingers and toes. | NSTEMI, SVT | No |

| 16 | Sahu et al 16 | Alcohol | 50/M | HRS | DM | 1 mg 8 hourly. | NA | 2 | Digital gangrene and skin of bilateral lower limbs. | – | Yes |

| 17 | Posada et al 17 | Alcohol | 39/M | HRS | – | 0.5 mg 4 hourly. | NA | 3 | Skin of bilateral lower limbs. | – | Yes |

| 18 | Mégarbané et al 18 | (A) Alcohol/HCC | 68/M | HRS | – | 1 mg 6 hourly. | 3 | Skin of trunk, legs, tongue and scrotum. | Yes | ||

| (B) Metastatic adenocarcinoma | 74/M | Pseudo-HRS | DM, IHD, dyslipidaemia | 0.5 mg/hour infusion. | 4 | Scalp. | – | Yes | |||

| 19 | Di Micoli et al 19 | HCV, HCC | 65/F | HRS | Hypothyroidism | 3 mg/day × 3 days f/b 9 mg/day intravenous infusion. | 15 | 4 | Skin of bilateral breasts. | – | No |

| 20 | Donnellan et al 20 | (A) AIH, post liver transplant | 47/M | HRS | Chronic venous insufficiency | 0.5 mg 6 hourly + octreotide. |

24 | 2 | Skin of bilateral lower limb epidermolysis. | – | Yes |

| (B) NASH | 53/F | HRS | 0.5 mg 6 hourly + octreotide |

23 | 5 | Skin of the abdomen and thigh epidermolysis. | – | Yes | |||

| (C) Alcohol | 56/M | AVB | 1 mg 6 hourly + octreotide. | 9 | 3 | Skin of the right groin and flank epidermolysis. | – | Yes | |||

| 21 | Lee et al 21 | HBV | 41/M | HRS | 1 mg 4 hourly. | 30 | – | Toes and injection site. | – | NA | |

| 22 | Vaccaro et al 22 | Alcohol | 73/M | HRS | 0.5 mg 6 hourly. | 28 | 2 | Abdomen, thighs, scrotum and penis. | Yes |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; AVB, acute oesophageal variceal bleed; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; F, female; f/b, followed by; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HRS, hepatorenal syndrome; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; M, male; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia.

Figure 2.

Site of ischaemia reported in studies.

Terlipressin should be used with caution in patients with high MELD score, and is safe when used in continuous infusion rather than bolus dosing. However, in the current report, the patients developed ischaemic necrosis even when continuous infusion was used.23 Terlipressin is superior to norepinephrine in patients with ACLF with AKI but is poorly tolerated.24 The drawback of the current study was that we did not perform skin biopsy, which would have added more information on the pathogenesis. We also lacked a comparison with patients with low MELD score. Whether sicker patients develop skin necrosis or patients who develop skin necrosis become sick is difficult to conclude, but a large prospective study, including a homogeneous group of patients with ACLF, would help in ascertaining the same.

Learning points.

Terlipressin is associated with certain undesirable side effects.

Terlipressin should be used with caution in patients with high MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) score.

Most complications develop by the third to fifth day of infusion.

Terlipressin use requires strict vigilance for adverse events.

Healthcare providers should report unusual adverse drug reactions associated with clinical applications of terlipressin.

Footnotes

Contributors: AVK and PK made the study concept, collected the images and prepared the manuscript. Final input and technical support were provided by NPR and NR.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu, European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2018;69:406–60. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sarin SK, Kedarisetty CK, Abbas Z, et al. Acute-On-Chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL) 2014. Hepatol Int 2014;8:453–71. 10.1007/s12072-014-9580-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, et al. Acute-On-Chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1426–37. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chiang C-W, Lin Y-J, Huang Y-B. Terlipressin-Induced peripheral cyanosis in a patient with liver cirrhosis and hepatorenal syndrome. Am J Case Rep 2019;20:5–9. 10.12659/AJCR.913150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iglesias Julián E, Badía Aranda E, Bernad Cabredo B, et al. Cutaneous necrosis secondary to terlipressin therapy. A rare but serious side effect. Case report and literature review. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2017;109:380–3. 10.17235/reed.2017.4466/2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sarma P, Muktesh G, Dhaka N, et al. Terlipressin-induced peripheral ischemic gangrene in a diabetic patient. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2017;8:148 10.4103/jpp.JPP_42_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Herrera I, Leiva-Salinas M, Palazón JM, et al. [Extensive cutaneous necrosis due to terlipressin use]. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;38:12–13. 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2014.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ozel Coskun BD, Karaman A, Gorkem H, et al. Terlipressin-induced ischemic skin necrosis: a rare association. Am J Case Rep 2014;15:476 10.12659/AJCR.891084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sundriyal D, Kumar N, Patnaik I, et al. Terlipressin induced ischaemia of skin. Case Reports 2013;2013:bcr2013010050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee HJ, Oh MJ. A case of peripheral gangrene and osteomyelitis secondary to terlipressin therapy in advanced liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2013;19:179 10.3350/cmh.2013.19.2.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taşliyurt T, Kutlutürk F, Erdemır F, et al. Ischemic skin necrosis following terlipressin therapy: report of two cases and review of the literature. Turk J Gastroenterol 2012;23:787–91. 10.4318/tjg.2012.0490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yefet E, Gershovich M, Farber E, et al. Extensive epidermal necrosis due to terlipressin. Isr Med Assoc J 2011;13:180–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chandail VS, Jamwal V. Cutaneous complications of terlipressin. JK Science 2011;13:205. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bañuelos Ramírez DD, Sánchez Alonso S, Ramírez Palma MM. Sildenafil in severe peripheral ischemia induced by terlipressin. A case report. Reumatología Clínica 2011;7:59–60. 10.1016/j.reuma.2010.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elzouki A-N, El-Menyar A, Ahmed E, et al. Terlipressin-induced severe left and right ventricular dysfunction in patient presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med 2010;28:540.e1–540.e6. 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sahu S, Panda K, Patnaik SB, et al. Telipressin induced peripheral ischaemic gangrene and skin necrosis. Tropical Gastroenterology 2010;31:229–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Posada C, Feal C, García-Cruz A, et al. Cutaneous necrosis secondary to Terlipressin therapy. Acta Derm Venereol 2009;89:434–5. 10.2340/00015555-0651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mégarbané H, Barete S, Khosrotehrani K, et al. Two observations raising questions about risk factors of cutaneous necrosis induced by terlipressin (Glypressin). Dermatology 2009;218:334–7. 10.1159/000195676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Di Micoli A, Bracci E, Cappa FM, et al. Terlipressin infusion induces ischemia of breast skin in a cirrothic patient with hepatorenal syndrome. Dig Liver Dis 2008;40:304–5. 10.1016/j.dld.2007.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Donnellan F, Cullen G, Hegarty JE, et al. Ischaemic complications of Glypressin in liver disease: a case series. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;64:550–2. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02921.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee JS, Lee HS, Jung SW, et al. [A case of peripheral ischemic complication after terlipressin therapy]. Korean J Gastroenterol 2006;47:454–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vaccaro F, Giorgi A, Riggio O, et al. Is spontaneous bacterial peritonitis an inducer of vasopressin analogue side-effects? A case report. Digestive and Liver Disease 2003;35:503–6. 10.1016/S1590-8658(03)00225-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cavallin M, Piano S, Romano A, et al. Terlipressin given by continuous intravenous infusion versus intravenous boluses in the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Hepatology 2016;63:983–92. 10.1002/hep.28396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arora V, Maiwall R, Rajan V, et al. Terlipressin is superior to noradrenaline in the management of acute kidney injury in acute on chronic liver failure. Hepatology 2018. [Epub ahead of print: 3 Aug 2018]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]