Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a heterogeneous, chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune disease characterised by multiorgan involvement and the production of multiple autoantibodies. Neurological manifestations in SLE patients are frequently reported—the prevalence is 37%–90%. We present a unique case where the patient presented with bilateral wrist and foot drop for 4 days, which later led to the diagnosis of SLE-related vasculitic polyneuropathy. During the course of treatment, the patient received prednisone, rituximab and hydroxychloroquine. At 6-month follow-up, patient had reported significant improvement in her weakness with increased mobility in upper and lower extremities. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are necessary in these cases to prevent disease progression and morbidity.

Keywords: vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, peripheral nerve disease

Background

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a heterogeneous, chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune disease characterised by multiorgan involvement and the production of multiple autoantibodies. It presents with a wide range of manifestations that include arthritis/arthralgia. It may involve the skin as well as the vascular, renal and musculoskeletal systems; neuropsychiatric, haematological and serological symptoms also occur. Neurological manifestations of SLE are common and numerous. Disability from peripheral nervous is severe and requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent progression.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old Hispanic female patient, with a history of syphilis treated with penicillin, methamphetamine abuse and inflammatory arthritis pending work up, presented to the emergency room with a complaint of the bilateral wrist, hand and leg weakness associated with tingling and numbness in her hands and feet for the last 4 days. On presentation, the patient was tachycardic, but the other vital signs were within normal limits. On physical examination, bilateral wrist and ankle swelling and tenderness were seen, associated with bilateral wrist and foot drop. Her fingers were semiflexed, and she was unable to extend them. Reflexes were absent, and power was 0/5 in both the wrists and ankles. Proprioception was intact. All other systems and joints were normal on examination.

Investigations

On laboratory tests, the patient had a leukocytosis of 14 700 cells/µL, iron deficiency anaemia with haemoglobin of 79 g/L. The comprehensive metabolic panel showed low albumin levels, elevated alkaline phosphatase and normal renal function tests. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were significantly elevated at 18.4 mg/L and 120 mm/hour, respectively. The initial serological study revealed an antinuclear antibody titre of 1:320 with a homogeneous pattern. MRI of the brain and entire spine without contrast was performed, which did not reveal any acute pathological findings. Cerebral spinous fluid biochemistry was within normal limits, and Cerebrospinal Fluid Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test (CSF VDRL) was negative as well.

The patient was evaluated by neurology, started on intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) due to concern for demyelinating neuropathy, and was transferred to a tertiary centre for further evaluation with electromyography (EMG) and nerve biopsy. Other serological tests were pending at the time of transfer.

The serological tests later revealed positive antidouble-stranded DNA at 20 IU/mL, negative for ANCA, smith antibody, smith/ribonucleoprotein antibody, rheumatoid factor, Sjogren 70, HIV antigen, antibody, hepatitis B, hepatitis C antibody, rapid plasma reagin (RPR) ratio was 1:16, with low C4 level, normal C3 level and elevated urine protein to creatinine ratio at 0.458. thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level was normal, and vitamin B12 was normal.

EMG was performed at the tertiary centre, which was consistent with axonal sensorimotor neuropathy, involving both small and large fibres. Left sural nerve biopsy and adjacent muscle biopsy were performed which showed severe axonal neuropathy with ongoing Wallerian degeneration (figures 1 and 2), chronic inflammation within the endoneurium and the vessel walls supplying blood to the neurons, demonstrated by moderate inflammatory infiltrate with T cells and B cells, which was consistent with vasculitis causing the neuropathy (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 1.

H&E stain (200× magnification; scale bar 50 μm) shows frequent digestion chambers (arrows), indicative of active Wallerian degeneration. Axons are not seen.

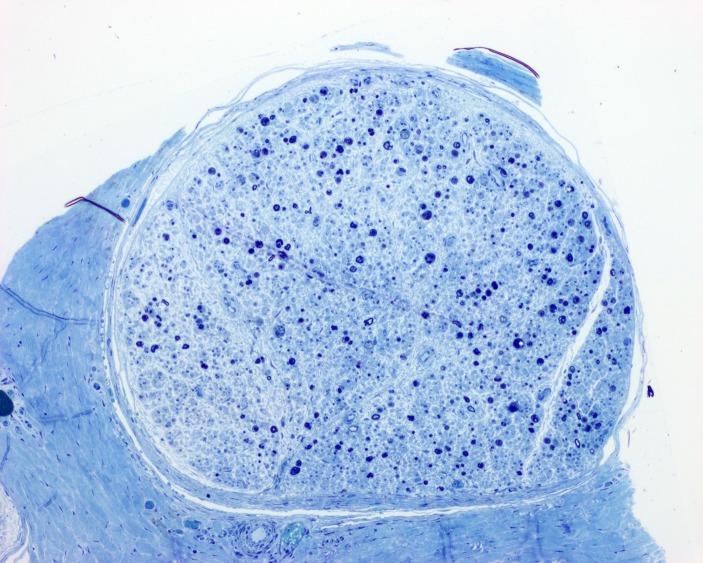

Figure 2.

Toluidine blue stain (100× magnification; scale bar 100 μm) shows loss of >95% of large and small myelinated axons, with the remaining axons showing degenerative changes.

Figure 3.

H&E stain (100× magnification; scale bar 100 μm) shows a moderate inflammatory infiltrate within and adjacent to a blood vessel.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry for Cluster of Differentiation 68 (CD68) (100× magnification; scale bar 100 μm) shows abundant macrophages within the wall of a blood vessel.

Treatment

The patient’s presentation with inflammatory arthritis, polyneuropathy, lab reports consistent with positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) and antidsDNA, low complement level, electrodiagnostic studies were revealing axonal sensorimotor neuropathy and biopsy showing changes of vasculitis led to the diagnosis of severe sensorimotor polyneuropathy secondary to vasculitis associated with SLE.

The patient was started on prednisone and was given four rounds of rituximab and discharged on prednisone 60 mg, gabapentin and duloxetine for pain. On outpatient follow-up with rheumatology, she was started on hydroxychloroquine 300 mg daily. She was slowly tapered off her prednisone to a daily dose of 15 mg.

Outcome and follow-up

At a 6-month follow-up, the patient had reported significant improvement in her weakness with increased mobility in upper and lower extremities, although difficulty with wrist and finger extension was present. She is no longer using wrist braces and can walk short distances with ankle and foot orthosis. She continues on hydroxychloroquine with ongoing physical and occupational therapy.

Discussion

SLE is a heterogeneous, chronic, autoimmune, inflammatory disease characterised by multiorgan involvement and the production of multiple autoantibodies. It can present with a wide range of manifestations that include cutaneous involvement and serological, haematological, vascular, renal, musculoskeletal and neuropsychiatric symptoms.1–3 Neuropsychiatric events in SLE patients are frequently reported—the prevalence is 37%–90%. Manifestations of SLE in the central nervous system (CNS) have received much attention over the years; many studies have reported on their prevalence, symptoms and probable pathological mechanisms.2 Peripheral nervous system manifestations of SLE (SLE-PN) have, on the other hand, received little attention despite their potentially significant impact on the patient’s quality of life.2

In 1999, a committee of the American College of Rheumatology proposed the existence of 19 neuropsychiatric syndromes in SLE, of which seven involve the peripheral nervous system.4 Involvement of the peripheral nervous system in SLE may take several different forms, including Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), autonomic disorder, mononeuropathy, polyneuropathy and plexopathy.5

SLE-PN can present as paraesthesias, pain, muscle weakness in the extremities, difficulty holding objects or writing, difficulty walking, frequent falls and poor balance. Decreased sensation, strength and diminished or absent reflexes can be seen on examination. Our patient reported paraesthesia but had preserved sensation; decreased strength and reflexes were absent in hands and feet. Proprioception was preserved as well. Peripheral neuropathy can present in various patterns that can give clues about the differential diagnosis which needs to be considered. Table 1 shows the various patterns of peripheral neuropathy and their differential diagnoses.6

Table 1.

Patterns for peripheral neuropathy and related diagnoses6

| Pattern no. |

Neurological involvement | Causes |

| 1. | Symmetric proximal and distal weakness with sensory loss |

|

| 2. | Symmetric distal sensory loss with or without distal weakness | Cryptogenic sensory polyneuropathy. Metabolic disorders. Drugs, toxins. Hereditary (Charcot-Marie-Tooth, amyloidosis and others). |

| 3. | Asymmetric distal weakness with sensory loss |

|

| 4. | Asymmetric proximal and distal weakness with sensory loss |

|

| 5. | Asymmetric distal weakness without sensory loss |

|

| 6. | Symmetric sensory loss and distal areflexia with upper motor neuron findings |

|

| 7. | Symmetric weakness without sensory loss |

Hereditary motor neuropathy. |

| 8. | Focal midline proximal symmetric weakness |

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS). |

| 9. | Asymmetric proprioceptive sensory loss without weakness |

|

| 10. | Autonomic symptoms and signs |

|

EMG studies may be abnormally early in the course of presentation without any clinical symptoms of peripheral neuropathy.7 Histological findings can be helpful in difficult situations in which nerve conduction studies are non-contributive. If EMG studies are normal, neuropathy may be diagnosed by nerve biopsy.8

Vasculitis is an important cause of peripheral neuropathy in SLE. The main histopathological feature of SLE vasculitic neuropathy is inflammation of the blood vessel wall causing ischaemic nerve injury which results in axonal loss. The small epineurial arterioles are predominantly affected in most cases of SLE vasculitic neuropathy.9 10 Wallerian degeneration of nerve fibres is also evident; it is secondary to ischaemic infarction due to the occlusion of blood vessels caused by leukocytoclastic vasculitis.9 In the pathogenesis of peripheral neuropathy in SLE, Mawrin et al also reported that the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-3 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 may be related to vessel wall injury, resulting in a chronic combined axonal and demyelinating type of SLE-PN.1 3

Pruzansk et al studied the relationship between phospholipase A2 activity, antilipocortin antibodies and severity of SLE in a group of 81 patients and found no significant correlation among them.11 Bortoluzzi et al studied PNS involvement in SLE in a systematic review and found that damage accrual and higher age are related to higher risk of PNS involvement, the most common manifestation is peripheral polyneuropathy followed by cranial nerve neuropathy, and GBS and plexopathy are extremely rare in SLE.12

Racanelli et al stressed the need to decipher the mechanisms of autoantibody generation in autoimmune diseases, including SLE and suggested that the molecular mechanisms involving autoantibodies against the intracellular antigens have to be analysed to identify the key steps in pathogenesis that could be targeted by therapy.13 Barturen et al discussed the basis for introducing a new molecular taxonomy for autoimmune rheumatic diseases including SLE and rheumatoid arthritis, by reviewing the evidence regarding the common molecular features related to the pathogenesis and development of these diseases and introduced a new project named PRECISESADS for this purpose.14

Our patient’s EMG was consistent with axonal sensorimotor neuropathy that involved both small and large fibres. Left sural nerve biopsy and adjacent muscle biopsy showed severe axonal neuropathy with ongoing Wallerian degeneration (figures 1 and 2) and chronic inflammation around the vessels (and their walls) supplying blood to the neurons. This was demonstrated by a moderate inflammatory infiltrate within the endoneurium and around the blood vessels throughout the nerve which is consistent with vasculitis causing the neuropathy (figures 3 and 4).

In 2019, a European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) update recommended that all patients with SLE should be started on hydroxychloroquine. During chronic maintenance, glucocorticoids should be minimised and, when possible, withdrawn. Appropriate initiation of immunomodulatory therapy (methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate) can expedite the tapering or discontinuation of glucocorticoids. For persistently active or flaring extra-renal disease that has become refractory, the use of rituximab or belimumab is recommended. Cyclophosphamide has been the gold standard treatment for many decades, but EULAR proposes that it should be considered in organ-threatening disease (especially renal, cardiopulmonary or neuropsychiatric) and only as rescue therapy in refractory non-major organ manifestations, due to its gonadotoxic effects.15

Xiong et al have reviewed the pragmatic approaches to therapy for SLE, concluding that mild SLE generally has been treated with NSAIDs and antimalarial agents as first line therapy with additional use of glucorticoids and immunosuppressive drugs in cases that involve organs. New therapies include the use of targeted immunotherapies in patients who do not have remission despite the standard treatment.16 Dammacco et al conducted a randomised controlled study for studying the effect of low-dose cyclosporine-A plus steroids versus steroids in early-stage, active SLE which showed significantly better results in the group with cyclosporine-A plus prednisone and suggested sparing use of steroids with cyclosporine-A to maintain clinical remission in such patients.17

Our patient was initially started on IV IgG due to a concern for demyelinating polyneuropathy. In our patient, peripheral neuropathy with bilateral wrist and foot drop was unusually aggressive. After the diagnosis of SLE-PN, she was started on rituximab due to significant bilateral wrist and foot involvement. While cyclophosphamide is considered the gold standard treatment for SLE but it was not preferred in this patient because of her young age and concern for infertility associated with its use. She was discharged on prednisone and was later started on hydroxychloroquine and was tapered off the glucocorticoids. Due to the severity of the disease, the patient also received four doses of rituximab. At her 6-month follow-up, the patient showed improvement in the hand and feet was no longer using wrist braces and is able to walk short distances with ankle and foot orthosis. She continues on hydroxychloroquine with ongoing physical and occupational therapy.

Learning points.

Neurological manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are common and numerous.

Peripheral neuropathy though not life threatening like SLE-central nervous system (CNS) is associated with severe morbidity and affects the quality of life significantly, especially in the younger population.

It is important to include peripheral nervous system manifestations of SLE (SLE-PN) as one of the differential diagnoses in patients with polyneuropathy.

Electromyography (EMG) can help in diagnosis along with other serological markers, but if EMG is non-contributive, nerve biopsy is required for an early diagnosis and treatment to differentiate from demyelinating neuropathies and to prevent progression of the disease and morbidity.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first case report of SLE-PN with bilateral wrist and foot drop.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS, RR and JH made a significant contribution to the data acquisition. SS worked on data analysis and interpretation, drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Xianbin W, Mingyu W, Dong X, et al. Peripheral neuropathies due to systemic lupus erythematosus in China. Medicine 2015;94:e625 10.1097/MD.0000000000000625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Florica B, Aghdassi E, Su J, et al. Peripheral neuropathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011;41:203–11. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mawrin C, Brunn A, Röcken C. Peripheral neuropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: pathomorphological features and distribution pattern of matrix metalloproteinases. Small nerve fiber involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:1228–32.12115228 [Google Scholar]

- 4. ACR Ad Hoc Committee on Neuropsychiatric Lupus Nomenclature The American College of rheumatology Nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dall’era M, Wofsy D. Clinical features of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus : Firestein G, Budd R, Gabriel SE, Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. Volume II 9th edn Elsevier Saunders, 2013: 1283–303. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barohn RJ, Amato AA. Pattern-recognition approach to neuropathy and neuronopathy. Neurol Clin 2013;31:343–61. 10.1016/j.ncl.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Luyendijk J, Steens SCA, Ouwendijk WJN, et al. Neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: lessons learned from magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:722–32. 10.1002/art.30157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thouraya BS, Nabil B, Mounir L, et al. Peripheral neuropathies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Neurol Neurosci 2016;7:S3. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhowmik A, Banerjee P. Mononeuritis multiplex complicating systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian Pediatr 2012;49:581–2. 10.1007/s13312-012-0098-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barile-Fabris L, Hernández-Cabrera MF, Barragan-Garfias JA. Vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014;16:440 10.1007/s11926-014-0440-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pruzanski W, Goulding NJ, Flower RJ, et al. Circulating group II phospholipase A2 activity and antilipocortin antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. correlative study with disease activity. J Rheumatol 1994;21:252–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bortoluzzi A, Silvagni E, Furini F, et al. Peripheral nervous system involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of the evidence. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37:146–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Racanelli V, Prete M, Musaraj G, et al. Autoantibodies to intracellular antigens: generation and pathogenetic role. Autoimmun Rev 2011;10:503–8. 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barturen G, Beretta L, Cervera R, et al. Moving towards a molecular taxonomy of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018;14:75–93. 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, et al. Update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;2019:736–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xiong W, Lahita RG. Pragmatic approaches to therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014;10:97–107. 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dammacco F, Della Casa Alberighi O, Ferraccioli G, et al. Cyclosporine-A plus steroids versus steroids alone in the 12-month treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Clin Lab Res 2000;30:67–73. 10.1007/s005990070017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]