Abstract

Background

We evaluated the epidemiology of fluid balance (FB) over the first postnatal week and its impact on outcomes in a multi-center cohort of premature neonates from the AWAKEN study.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of infants <36 weeks’ gestational age from the AWAKEN study (N = 1007). FB was defined by percentage of change from birth weight. Outcome: Mechanical ventilation (MV) at postnatal day 7.

Results

One hundred and forty-nine (14.8%) were on MV at postnatal day 7. The median peak FB was 0% (IQR: −2.9, 2) and occurred on postnatal day 2 (IQR: 1,5). Multivariable models showed that the peak FB (aOR 1.14, 95% CI 1.10–1.19), lowest FB in first postnatal week (aOR 1.12, 95% CI 1.07–1.16), and FB on postnatal day 7 (aOR 1.10, 95% CI 1.06–1.13) were independently associated with MV on postnatal day 7. In a similar analysis, a negative FB at postnatal day 7 protected against the need for MV at postnatal day 7 (aOR 0.21, 95% CI 0.12–0.35).

Conclusions

Positive peak FB during the first postnatal week and more positive FB on postnatal day 7 were independently associated with MV at postnatal day 7. Those with a negative FB at postnatal day 7 were less likely to require MV.

Introduction

Over the past several decades, it has become clear that premature neonates are subject to multi-organ dysfunction, which frequently includes renal dysfunction. The Assessment of Worldwide Acute Kidney Injury Epidemiology in Neonates (AWAKEN) study clearly showed that acute kidney injury (AKI) occurs commonly in preterm neonates with an incidence of 24.9% in those <36 weeks’ gestational age and is associated with increased mortality and length of stay.1 A critical step in improving outcomes is to begin to understand how AKI impacts the function of distant organs.2 In particular, AKI has been shown to affect lung physiology in a number of ways, including inflammation, acid/base imbalance, and disturbances in fluid balance.2 A complete understanding of the impact of fluid balance in neonates is critical as this represents a potential target for intervention.

Fluid balance and, at its extreme, fluid overload (FO) is one of the most active areas in research across critical care nephrology.3–14 Pediatricians have long recognized that FO has a deleterious impact on outcomes in critically ill patients, which has now extended into adult surgical and medical cohorts. Using the AWAKEN dataset, we recently showed that fluid balance in the first postnatal week predicted the need for mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7 in a cohort of 645 critically ill neonates ≥36 weeks’ gestational age.3 Early work in preterm neonates recognized that abnormalities in fluid balance (high fluid intake and weight gain or absence of appropriate weight loss) are associated with the development of chronic lung disease.15,16 However, these studies did not systematically evaluate fluid balance in the context of AKI. The epidemiology and impact of fluid balance and AKI on respiratory status in a preterm population has not been systematically evaluated.

The AWAKEN study captured data on AKI, fluid balance, and the impact of other renal-related risk factors on short-term outcomes.1,3,17–20 Using these data, we sought to: (1) describe the pattern of changes in fluid balance in preterm neonates during the first postnatal week, (2) evaluate the association of fluid balance with AKI, and (3) investigate the association of fluid balance with an important short-term clinical outcome, mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7. Our primary hypothesis is that a more positive fluid balance during the first postnatal week is independently associated with the need for mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7.

Methods

Study population

The AWAKEN study protocol has been previously published.17 Screening included all neonates admitted to 24 level 2–4 neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) between January 1 and March 31, 2014. Inclusion criterion for enrollment was receipt of intravenous fluids (IV) for at least 48 h. Exclusion criteria included: (1) admission at ≥14 days after birth, (2) congenital heart disease requiring surgical repair before postnatal day 7, (3) lethal chromosomal anomaly, (4) death within 48 h of NICU admission, and (5) severe congenital kidney and urinary tract abnormalities. We limited this analysis to those patients with gestational age <36 weeks, admission at or before postnatal day 7, data sufficient to calculate AKI, and recorded weight by postnatal day 2. Each center involved in the study received approval from their Institutional Review Board or Human Research Ethics Committee.

Data collection

The data collected for the AWAKEN study included five components: baseline demographics, daily information for the first postnatal week, weekly “snapshots” for the remaining hospitalization, and discharge data (discharge or 120 days of age).1,17 Day of birth was defined as postnatal day 1.

Fluid balance definitions

The AWAKEN study protocol included daily weights, fluid intake (IV fluids, enteral fluids), and outputs (urine, total output, all other documented fluid loss) for the first 7 postnatal days, when available. Documentation was subject to local protocols.

The quantification of all potential sources of intake for the first week of life varied by institution and differed by the type of intake (e.g., the amount of maternal breast milk ingested at breast could not be quantified). Similarly, quantification of urine output, usually based on diaper weights, as well as other sources of fluid loss, was often incomplete. We chose to use daily weights to define fluid balance as there was much more missing data on intake/output than on weights and the difference between successive weights is an excellent approximation of net fluid loss or gain consistent with the previously published work in neonates ≥36 weeks.3 An analysis of the number of available data points is presented in the “Results” section below.

Fluid balance was calculated based on a comparison of daily weight with birth weight: Percentage of change = (daily weight − birth weight)/birth weight × 100. We calculated the maximum and minimum weight change during the first postnatal week, percentage of change from birth weight on postnatal days 3 and 7, and the highest and lowest change from birth weight during the first postnatal week, as previously reported in our evaluation of neonates ≥36 weeks’ gestation.3

Similar to our previous publication evaluating fluid balance in neonates ≥36 weeks’ gestation, we utilized 5 variables to describe fluid balance over the first postnatal week.3 The 5 variables include: (a) the maximum percentage of weight change that occurred on postnatal days 2–7 of age, (b) the minimum percentage of weight change that occurred on postnatal days 2–7 of age, (c) the percentage of weight change at postnatal day 3, (d) the percentage of weight change at postnatal day 7, and (e) negative fluid balance at postnatal day 7. The negative fluid balance at postnatal day 7 was defined as being below birth weight at postnatal day 7.

AKI definition

The AWAKEN study extracted all clinically obtained serum creatinine (SCr) measurements during the study period. A neonatal modification of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Workgroup AKI was used to define neonatal AKI in the first week of life.1,21–23 Based on these criteria, AKI was defined as an average urine output <1 cc/kg/h over a 24-h period in the first 7 days and/or SCr rise ≥0.3 mg/dl or 50% from a previous trough.

Results stratified by gestational age

We describe our findings for the entire cohort of premature infants. In addition, we stratified the groups into premature infants <29 weeks (22 0/7–28 6/7 weeks’ gestational age) and those ≥29 weeks (29 0/7–35 6/7 weeks’ gestational age). These stratifications are consistent with those utilized across the AWAKEN study.1

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was the need for mechanical ventilation (high frequency or conventional ventilation) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation at postnatal day 7.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed by proportional differences with the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test (where appropriate). Continuous variables were tested for normality using Shapiro–Wilk test. For normally distributed continuous variables, the mean ± standard deviation (SD) were reported and analyzed using Student’s t test. For non-normally distributed variables, the median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported and groups were compared using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Logistic regression models were used to calculate crude odds ratios (ORs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between maximum fluid balance, minimum fluid balance, fluid balance on day 3, and fluid balance on day 7 with the likelihood of mechanical ventilation at day 7. Multivariable logistic regression models were run to account for potential confounding variables, and findings are reported as adjusted OR (aOR). Adjusted regression models were constructed using a backwards selection procedure with a significance level of <0.2. Separate regression models were created for each of the exposures of interest. In all analyses, a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 4273 neonates screened in the AWAKEN study, 2162 met the inclusion criteria, and 2022 had the required lab data to diagnose AKI. A total of 1189 of the 2022 infants in the AWAKEN study were <36 weeks’ gestational age. A total of 1007 neonates were included in the current report after exclusion of neonates with insufficient data for analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). An evaluation of the excluded patients is presented in Supplementary Table 1 and showed that excluded patients had significantly higher mortality (16.5% vs. 2.8%, p < 0.0001).

The baseline characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1. A total of 233 (23.1%) neonates were <29 weeks’ gestational age and 774 (76.9%) were gestational age ≥29 weeks. AKI occurred in 147 (14.6%) neonates in the first postnatal week. The most common admitting diagnoses, in addition to prematurity, were respiratory diagnoses (77.4%), sepsis evaluation (55.9%), and small for gestational age (21.4%).

Table 1.

Demographics and variables related to the need for mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7 in the whole cohort

| Whole cohort (N = 1007) | Mechanical ventilation at 7 days (N = 149) | No mechanical ventilation at 7 days (N = 858) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant variables | ||||

| Gender (male) | 551 | 90 (60.4%) | 461 (53.7%) | 0.30 |

| Ethnicity | 0.09 | |||

| Hispanic | 144 | 19 (12.7%) | 125 (14.6%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 731 | 118 (79.2%) | 613 (71.4%) | |

| Unknown | 132 | 12 (8.1%) | 120 (14.0%) | |

| Race | 0.70 | |||

| White | 565 | 83 (55.7%) | 482 (56.2%) | |

| Black | 207 | 34 (22.8%) | 173 (20.2%) | |

| Other | 235 | 32 (21.5%) | 203 (23.6%) | |

| Site of delivery (outborn) | 252 | 60 (40.3%) | 192 (22.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Gestational age | <0.0001 | |||

| 22 0/7–28 6/7 weeks | 233 | 104 (69.8%) | 129 (15.0%) | |

| 29 0/7–35 6/7 weeks | 774 | 45 (30.2%) | 729 (85.0%) | |

| Birth weight, g | <0.0001 | |||

| ≤1000 | 192 | 99 (66.4%) | 93 (10.8%) | |

| 1001–1500 | 263 | 20 (13.4%) | 243 (28.3%) | |

| 1501–2500 | 467 | 21 (14.1%) | 446 (52.0%) | |

| ≥2501 | 85 | 9 (6.0%) | 76 (8.9%) | |

| Apgar 1 min | 7 (4, 8) | 3 (1, 6) | 7 (5, 8) | <0.0001 |

| Apgar 5 min | 8 (7, 9) | 6 (4, 8) | 8 (7, 9) | <0.0001 |

| Acute kidney injury (first 7 days) | 147 (14.6%) | 46 (30.9%) | 101 (11.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Reason for admission | ||||

| Prematurity <36 weeks | 918 | 137 (91.9%) | 781 (91.0%) | 0.71 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 197 | 20 (13.4%) | 177 (20.6%) | 0.04 |

| Respiratory failure | 603 | 122 (81.9%) | 481 (56.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Sepsis evaluation | 563 | 92 (61.7%) | 471 (54.9%) | 0.12 |

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy | 21 | 11 (7.4%) | 10 (1.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Seizures | 6 | 4 (2.7%) | 2 (0.2%) | 0.01 |

| Hypoglycemia | 88 | 6 (4.0%) | 82 (9.6%) | 0.03 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 15 | 3 (2.0%) | 12 (1.4%) | 0.47 |

| Metabolic evaluation | 2 | 2 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.02 |

| Trisomy 21 | 4 | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.5%) | 1.00 |

| Congenital heart disease | 9 | 5 (3.4%) | 4 (0.5%) | 0.01 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 5 | 4 (2.7%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0.002 |

| Omphalocele/gastroschisis | 12 | 4 (2.7%) | 8 (0.9%) | 0.09 |

| Need for surgical evaluation | 14 | 7 (4.7%) | 7 (0.8%) | 0.002 |

| Meningomyelocele | 4 | 1 (0.7%) | 3 (0.3%) | 0.47 |

| Small for gestational age | 215 | 32 (21.5%) | 183 (21.3%) | 0.97 |

| Large for gestational age | 8 | 1 (0.7%) | 7 (0.8%) | 1.00 |

| Maternal variables | ||||

| Maternal age (years) | 28.2 ± 6.7 | 28.8 ± 6.2 | 0.30 | |

| Infections | ||||

| Bacterial | 88 | 15 (10.1%) | 73 (8.5%) | 0.53 |

| Viral | 32 | 4 (2.7%) | 28 (3.3%) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | 138 | 16 (10.7%) | 122 (14.2%) | 0.25 |

| Hypothyroidism | 48 | 7 (4.7%) | 41 (4.8%) | 0.97 |

| Chronic hypertension | 115 | 14 (9.4%) | 101 (11.8%) | 0.40 |

| Kidney disease | 11 | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (1.3%) | 0.38 |

| Pre-eclampsia | 198 | 22 (14.8%) | 176 (20.5%) | 0.10 |

| Eclampsia | 18 | 3 (2.0%) | 15 (1.7%) | 0.74 |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 113 | 14 (9.4%) | 99 (11.5%) | 0.44 |

| Oligohydramnios | 54 | 11 (7.4%) | 43 (5.0%) | 0.24 |

| Polyhydramnios | 29 | 6 (4.0%) | 23 (2.7%) | 0.42 |

| Hemorrhage | 40 | 8 (5.4%) | 32 (3.7%) | 0.34 |

| Gestation | 293 | 38 (25.5%) | 255 (29.7%) | 0.29 |

| Assisted conception | 116 | 18 (12.1%) | 98 (11.4%) | 0.05 |

| Intrapartum complications | ||||

| Nuchal cord | 39 | 8 (5.4%) | 31 (3.6%) | 0.31 |

| Meconium | 38 | 5 (3.4%) | 33 (3.4%) | 1.00 |

| Severe vaginal bleeding | 56 | 13 (8.7%) | 43 (5.0%) | 0.07 |

| Shoulder dystocia | 3 | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (0.2%) | 0.38 |

| Medications | ||||

| Vasopressors | 78 | 43 (28.9%) | 35 (4.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Antimicrobials | 758 | 119 (79.9%) | 639 (74.5%) | 0.16 |

On postnatal day 7, 149 neonates (14.8%) were mechanically ventilated. Table 1 includes a detailed analysis of the patient characteristics associated with need for mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7. Those who required mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 7 were more likely to be <29 weeks’ gestational age, have had lower 1- and 5-min Apgar scores, admitted for respiratory failure, received vasopressors, and have had AKI (Table 1). These findings were similar when each gestational cohort was examined independently (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Fluid balance

A total of 6042 potential days of data were available over the first postnatal week for the entire population. Complete intake and output data were available on 71.8% of days. Weight was recorded on 90.9% of the possible days.

Fluid balance in the first postnatal week in all subjects and by gestational age classification is shown in Table 2. The median peak fluid balance during the first postnatal week was 0% (IQR: −2.9, 2.0) and occurred on postnatal day 2 (IQR: 1, 5). The median lowest fluid balance during the first postnatal week was −7.7% (IQR: −10.9, −4.5) and occurred on postnatal day 3 (IQR: 2, 5). Supplementary Table 4 describes the daily fluid balance for all subjects by gestational age (<29 vs. ≥29 weeks’ gestational age). Throughout the first postnatal week, neonates in the ≥29 weeks’ gestational age cohort had consistently higher fluid balance than the younger cohort.

Table 2.

Trends of fluid balance by in the first postnatal week

| Whole cohort (<36 weeks) | <29 weeks | ≥29 weeks | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak fluid balance | 0 (−2.9, 2.0) | 0 (−3.6, 3.2) | 0 (−2.7, 1.7) | 0.75 |

| Day of peak | 2 (1, 5) | 2 (1, 5) | 2 (1, 5) | 0.99 |

| Lowest fluid balance | −7.7 (−10.9, −4.5) | −10.3 (−14.5, −6.1) | −7.2 (−9.9, −4.3) | <0.0001 |

| Day of lowest | 3 (2, 5) | 4 (3, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | 0.25 |

| Fluid balance at day 3 | −4.4 (−7.3, −1.5) | −5.5 (−8.6, −1.3) | −4.3 (−6.9, −1.8) | 0.01 |

| Fluid balance at day 7 | −4.4 (−8.1, 0) | −6.0 (−10.9, 0) | −4.0 (−7.3, 0) | 0.0002 |

Fluid balance and AKI

The incidence of AKI in the cohort was 14.6% (N = 147) in the first postnatal week. This included 6.4% (N = 64) with stage 1, 3.9% with stage 2 (N = 39), and 4.4% (N = 44 with 2 requiring renal replacement therapy) with stage 3 AKI. The incidence of AKI was 24% in those 22–28 weeks’ gestational age and 11.7% in those ≥29 weeks’ gestational age. Table 3 shows differences in fluid by AKI status over the first postnatal week. Neonates with AKI were less likely to have a negative fluid balance at postnatal day 7 and had consistently higher peak fluid balance during the first postnatal week.

Table 3.

Trends of fluid balance by acute kidney injury in the first postnatal week

| Outcome | N | AKI in first postnatal week | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 147) | No (N = 860) | |||

| Peak fluid balance first week | 1007 | 0 (−2.0, 4.0) | 0 (−3.1, 1.7) | 0.003 |

| Lowest fluid balance first week | 1007 | −7.4 (11.2, −3.8) | −7.7 (−10.8, −4.8) | 0.65 |

| Fluid balance at postnatal day 3 | 929 | −3.7 (−8.0, −0.6) | −4.5 (−7.3, −1.8) | 0.15 |

| Fluid balance at postnatal day 7 | 948 | −3.1 (−8.2, 1.5) | −4.6 (−8.1, 0) | 0.07 |

| Negative fluid balance at postnatal day 7 | 948 | 90 (61.2%) | 609 (70.8%) | 0.04 |

AKI acute kidney injury

Association of fluid balance with outcomes

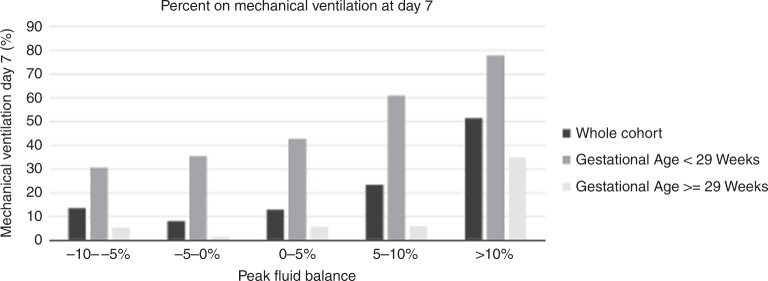

One hundred and forty-nine neonates (14.9%) had the primary outcome of interest (mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 7). Table 1 describes the associations between the need for mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 7 and patient clinical and demographic characteristics. This is also reported by gestational age groups in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. A description of the association of fluid balance by the need for mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 7 is summarized in Table 4. The need for mechanical ventilation at postnatal day was associated with fluid balance on postnatal days 3 and 7 and peak fluid balance (Table 4). Figure 1 demonstrates that in general there was a graded increase in the need for mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7 by increasing peak fluid balance (by 5% intervals). This was seen in both the <29 weeks’ gestational age cohort as well as in the ≥29 weeks’ gestational age cohort. This was most profound in the older cohort of subjects who reached >10% over birth weight. The daily epidemiology of fluid balance in the first postnatal week evaluating the need for mechanical ventilation in each gestational age cohort is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Fluid balance stratified by the need for mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7

| Outcome | N | Mechanically ventilated at postnatal day 7 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 149) | No (N = 858) | |||

| Peak fluid balance first week | 1007 | 1.2 (−1.2, 9.3) | 0 (−3.1, 1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Lowest fluid balance first week | 1007 | −7.0 (−13.3, −2.0) | −7.7 (−10.6, −5.0) | 0.19 |

| Fluid balance at postnatal day 3 | 929 | −2.7 (−7.0, 1.2) | −4.5 (−7.3, −2.2) | 0.003 |

| Fluid balance at postnatal day 7 | 948 | −2.6 (−9.4, 4.9) | −4.5 (−8.0, −0.6) | 0.01 |

| Negative fluid balance at postnatal day 7 | 948 | 72 (48.3%) | 627 (73.1%) | <0.0001 |

Fig. 1.

The association of fluid balance and the need for mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 7

After adjusting for confounding variables, each fluid balance measure (peak fluid balance during the first postnatal week, lowest fluid balance during the first postnatal week, fluid balance on postnatal day 3, fluid balance postnatal day 7, and negative fluid balance at postnatal day 7) remained independently associated with the need for mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 7 (Table 5). The multivariable analyses showed that, after adjusting for delivery site, gestational age, 5 min Apgar, AKI in the first week of life, admission for surgery, and vasopressors, for every 1% increase in maximum fluid balance there was a 14% increased odds of receiving mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7 (aOR 1.14, 95% CI: 1.10–1.19; p < 0.0001). Similarly, after controlling for the same variables, for every 1% increase in the lowest fluid balance in the first postnatal week there was a 12% increased odds of mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7 (aOR 1.12, 95% CI: 1.07–1.16; p < 0.0001). Furthermore, those with a negative fluid balance on postnatal day 7 had significantly lower odds of being mechanically ventilated on postnatal day 7 (aOR 0.21, 95% CI: 0.12–0.35; p < 0.0001). The results of unadjusted and adjusted analysis did not differ significantly when the analyses were run for each gestational age cohort separately (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Crude and adjusted logistic regression modeling for mechanical ventilation in the first postnatal weeka

| Exposure of interest | Crude (OR, 95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted (OR, 95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak fluid balance in first postnatal week | 1.13 (1.09–1.16) | <0.0001 | 1.14 (1.10–1.19) | <0.0001 |

| Lowest fluid balance in first postnatal week | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.01 | 1.12 (1.07–1.17) | <0.0001 |

| Fluid balance postnatal day 3 | 1.07 (1.04–1.11) | <0.0001 | 1.12 (1.07–1.16) | <0.0001 |

| Fluid balance postnatal day 7 | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | <0.0001 | 1.10 (1.06–1.13) | <0.0001 |

| Negative fluid balance at postnatal day 7 | 0.35 (0.24–0.50) | <0.0001 | 0.21 (0.12–0.35) | <0.0001 |

aAll logistic models adjusted for delivery site, gestational age, 5 min Apgar, AKI in the first week of life, admission for surgery, and vasopressors

Over 98% (N = 979) of subjects survived to NICU discharge. Stratification of NICU survival by fluid balance measures over the first postnatal week are described in Supplemental Table 7, with only the lowest fluid balance being associated with mortality (p = 0.04). Regression analysis could not be performed given the small event numbers.

Discussion

In this analysis of premature neonates from the AWAKEN study, we report the epidemiology of fluid balance and its impact on outcomes in the first postnatal week. We show that over half of the neonates had weights above birth weight in the first postnatal week indicating a positive fluid balance in that period. Furthermore, fluid balance in the first week of life is independently associated with the need for mechanical ventilation at postnatal day 7. This is consistent with reports from children showing that fluid balance is associated with poor lung function and heightened need for mechanical ventilation.6,24 In addition, fluid balance is associated with AKI, which is consistent with reports on the association between fluid balance and risk for AKI in adults and children after cardiac surgery13,25 and with those in sick near-term and term neonates in a single-center study and the AWAKEN study.3,26

The degree of fluid accumulation has been repeatedly demonstrated to be associated with increased morbidity and mortality across the spectrum of critical illness in term neonates, children, and adults. This association was first demonstrated in critically ill children who received continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT).9,10,14 A recent systematic review of studies including a spectrum of critically ill pediatric patient populations demonstrated that FO was associated with increased in-hospital mortality (OR 4.34 95% CI, 3.01–6.26). After adjustment for illness severity, there was a 6% increase in odds of mortality for every 1% increase in percentage of FO (aOR, 1.06, 95% CI, 1.03–1.10). In the same review, FO was also associated with increased risk for prolonged mechanical ventilation (>48 h, OR, 2.14, 95% CI, 1.25–3.66) and AKI (OR, 2.36, 95% CI, 1.27–4.38).24 The spectrum of patient populations in the meta-analysis spanned pediatric patients receiving CRRT, patients with sepsis and/or shock, and general pediatric intensive care unit populations, none of whom were newborns.

Until recently, there have been very little data on the impact of fluid balance in critically ill neonates. Similar to the findings in the current manuscript, analysis of neonates ≥36 weeks’ gestational age from the AWAKEN study showed that peak fluid balance in the postnatal first week was associated with the need for mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 7 (aOR 1.12, 95% CI 1.07–1.17 for ≥36 weeks gestational age vs. aOR 1.14, 95% CI 1.10–1.19 for <36 weeks gestational age) and a negative fluid balance on postnatal day 7 was protective (aOR 0.33, 95% CI 0.16–0.67 for ≥36 weeks gestational age vs. aOR 0.21, 95% CI 0.12–0.35 for <36 weeks gestational age).3 The current study extends these findings by showing an association between fluid balance and outcomes in preterm neonates, identifying a negative fluid balance during the first postnatal week as a potential therapeutic target warranting further study.

While the implications of disorders of fluid balance in premature neonatal populations appear to parallel those of older children, it is critical to understand these findings in the context of the unique physiology and the unique long-term consequence on lung function in newborns. Neonates are born with an excess of extracellular fluid and typically experience a natural diuresis with an expected weight loss of up to 10% in the days after birth. For premature infants, body water content is proportionally higher than in term infants, making the impact of fluid shifts even greater. The loss of extracellular fluid is essential in the normal transition to extrauterine life, especially in terms of pulmonary function, and is accomplished by a negative fluid balance, where urine output and insensible water loss exceed fluid administration. The current study provides important epidemiologic data which shows that the median peak fluid balance in the first postnatal week is 0% (IQR −2.9, 2.0). It is particularly concerning that over half the cohort had a peak fluid balance above birth weight with another quarter of the cohort ≥2% above their birth weight at a time when neonates are expected to undergo a physiologic diuresis.

Morbidities that impair this natural diuresis, including AKI, lead to a state of FO that invariably worsens underlying lung function and, in some newborns, lung pathology. The Neonatal Research Network published a retrospective study examining the association between the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and daily fluid intake as well as weight loss over the first 10 days of life. Even after adjusting for co-morbidities and other known risk factors for BPD, higher fluid intake and less weight loss were associated with the composite outcome of death or BPD.15 Schmidt and colleagues performed an analysis of patients from the Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms and found in patients without a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) who were randomized to receive indomethacin there was reduced weight loss in the first postnatal week and higher rates of BPD.16 The authors postulate that this FO may explain the association with BPD. A Cochrane review included five randomized studies comparing restricted vs. liberal fluid intake and morbidity and mortality in preterm infants. This meta-analysis found decreased risk of PDA and necrotizing enterocolitis in infants whose fluid intake was restricted and a trend (though not statistically significant) toward lower risk of BPD.27 Our study results are consistent with these studies in that the odds of requiring mechanical ventilation at 7 days of age were increased in patients who had a less negative fluid balance. More importantly, on adjusted analysis, a negative fluid balance on postnatal day 7 was protective against the need for mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 7 with an aOR of 0.21. Taken together, these data suggest that it may be beneficial to focus on the avoidance of FO during the first postnatal week in order to decrease short-term and potentially longer-term morbidities. It is apparent that not only extreme FO is important, but that small degrees of positive fluid balance increase morbidity and mortality.

Distinguishing the cause and effect relationship between FO as a marker of critical physiologic instability from playing a causative role in AKI development remains challenging. The association between FO and AKI has been well described in both adult and pediatric studies.3,13,26,28–32 Investigators have demonstrated the association between early positive fluid balance and risk for AKI in adults and children after cardiac surgery.13,25 A recent study by Hassinger et al. in children after cardiac surgery reported that FO was common, occurred before, and was independently associated with a diagnosis of AKI and a protracted course in the hospital including longer time on the ventilator.11 The current study extends these findings to preterm neonates by showing that those with AKI had a higher peak fluid balance with a quarter of those with AKI having a median peak fluid balance of ≥4%. Furthermore, those with AKI were less likely to have a negative fluid balance at postnatal day 7. While the cause and effect of disorders in fluid balance remains an important academic question, our data clearly show that small changes in fluid balance irrespective of the presence of AKI predict increased morbidity.

A major strength of this study is the number and variety of centers involved in this international multi-center study allowing for the detailed exploration of the impact of fluid balance on outcomes. Despite this strength, there are several limitations inherent to any retrospective study including being limited to only clinically obtained data (SCr, urine output, composition of fluids). Daily weights were available for only 91% of all possible patient days, which may have impacted the results. We therefore utilized subsequent weights and may have missed important increases or decreases, though misclassification is likely to have been infrequent. We acknowledge that, during sensitivity analysis, we had to exclude patients who died, which could affect our results and allow us to only generalize our findings to those who survive to 1 week of age. As the AWAKEN database only included daily clinical data over the first postnatal week and weekly “snapshots” thereafter, our conclusions were limited to this time period. Although the first week is extremely important, longer observation periods are necessary to confirm and extend our findings.

Conclusion

In this multi-center cohort study, we describe for the first time the distribution and impact of fluid balance in preterm neonates over the first postnatal week. Our study demonstrates that peak fluid balance, lowest fluid balance, and negative fluid balance on postnatal day 7 are all independently associated with the need for mechanical ventilation on postnatal day 7. Future prospective studies must be designed to evaluate the impact of a variety of fluid management strategies (fluid restriction, diuretics, etc.) on fluid balance and subsequent short- and longer-term outcomes.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to thank the outstanding work of the following clinical research personnel and colleagues for their involvement in AWAKEN: Ariana Aimani, Samantha Kronish, Ana Palijan, MD, Michael Pizzi—Montreal Children's Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC, Canada; Laila Ajour, BS, Julia Wrona, BS—University of Colorado, Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO; Melissa Bowman, RN—University of Rochester, Rochester, NY; Teresa Cano, RN, Marta G. Galarza, MD, Wendy Glaberson, MD, Aura Arenas Morales, MD, Denisse, Cristina Pareja Valarezo, MD—Holtz Children's Hospital, University of Miami, Miami, FL; Sarah Cashman, BS, Madeleine Stead, BS—University of Iowa Children’s Hospital, Iowa City, IA; Jonathan Davis, MD, Julie Nicoletta, MD—Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA; Alanna DeMello—British Columbia Children's Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada; Lynn Dill, RN—University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL; Ellen Guthrie, RN—MetroHealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH; Nicholas L. Harris, BS, Susan M. Hieber, MSQM—C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; Katherine Huang, Rosa Waters—University of Virginia Children’s Hospital, Charlottesville, VA; Judd Jacobs, Ryan Knox, BS, Hilary Pitner, MS, Tara Terrell—Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical, Center, Cincinnati, OH; Nilima Jawale, MD—Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY; Emily Kane—Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia; Vijay Kher, DM, Puneet Sodhi, MBBS—Medanta Kidney Institute, The Medicity Hospital, Gurgaon, Haryana, India; Grace Mele—New York College of Osteopathic Medicine, Westbury, NY; Patricia Mele, DNP—Stony Brook Children’s Hospital, Stony Brook, NY; Charity Njoku, Tennille Paulsen, Sadia Zubair—Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX; Emily Pao—University of Washington, Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA; Becky Selman RN, Michele Spear, CCRC—University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM; Melissa Vega, PA-C—The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY, USA); Leslie Walther, RN—Washington University, St. Louis, MO. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Center for Acute Care Nephrology provided funding to create and maintain the AWAKEN Medidata Rave electronic database. The Pediatric and Infant Center for Acute Nephrology (PICAN) provided support for web meetings, for the NKC steering committee annual meeting at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), as well as support for some of the AWAKEN investigators at UAB (L.J.B., R. Griffin). PICAN is part of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and is funded by Children’s of Alabama Hospital, the Department of Pediatrics, UAB School of Medicine, and UAB’s Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences (CCTS, NIH grant UL1TR001417). Finally, the AWAKEN study at the University of New Mexico was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Center (CTSC, NIH grant UL1TR001449) and by the University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (U54TR001356). C.L.A. was supported by the Micah Batchelor Foundation. A.-A.A. and C.J.R. were supported by the Section of Pediatric Nephrology, Department of Pediatrics, Texas Children’s Hospital. J.R.C. and J.R.S. were supported by a grant from 100 Women Who Care. F.S.C. and K.T.D. were supported by the Edward Mallinckrodt Department of Pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine. J.F. and A.K. supported by the Canberra Hospital Private Practice Fund. R.G. and E.R. were supported by the Department of Pediatrics, Golisano Children’s Hospital, University of Rochester. P.E.R. was supported by R01 HL-102497, R01 DK 49419. S.S. and D.T.S. were supported by the Department of Pediatrics & Communicable Disease, C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan. S.S. and R.W. were supported by Stony Brook Children’s Hospital Department of Pediatrics funding. Funding sources for this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Neonatal Kidney Collaborative

Namasivayam Ambalavanan17, Subrata Sarkar18, Alison Kent19, Jeffery Fletcher19, Carolyn L. Abitbol20, Marissa DeFreitas20, Shahnaz Duara20, Jennifer R. Charlton21, Jonathan R. Swanson21, Carl D’Angio22, Ayesa Mian22, Erin Rademacher22, Maroun J. Mhanna23, Rupesh Raina23, Deepak Kumar23, Jennifer G. Jetton24, Patrick D. Brophy24, Tarah T. Colaizy24, Jonathan M. Klein24, Christopher J. Rhee25, Juan C. Kupferman26, Alok Bhutada26, Shantanu Rastogi26, Susan Ingraham27, F. Sessions Cole28, T. Keefe Davis28, Lawrence Milner29, Alexandra Smith29, Mamta Fuloria30, Frederick J. Kaskel30, Danielle E. Soranno31, Jason Gien31, Aftab S. Chishti32, Sangeeta Hingorani33, Michelle Starr33, Sunny Juul33, Craig S. Wong34, Tara DuPont34, Robin Ohls34, Surender Khokhar35, Sofia Perazzo36, Patricio E. Ray36, Mary Revenis36, Sidharth K. Sethi37, Smriri Rohatgi37, Cherry Mammen38, Anne Synnes38, Sanjay Wazir39, Michael Zappitelli40, Robert Woroniecki41, Shanty Sridhar41

Author contributions

All listed authors provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests

D.J.A. serves on the speaker board for Baxter (Baxter, USA) and the Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) Foundation (Cincinnati, OH, USA); he also receives grant funding for studies not related to this manuscript from National Institutes of Health—National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIH-NIDDK (R01 DK103608) and NIH-FDA (R01 FD005092)). K.M.G. is a consultant for BioPorto. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Collaborators of the Neonatal Kidney Collaborative are listed below Acknowledgements.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

David T. Selewski, Phone: +843-792-8904, Email: selewski@musc.edu

on behalf of the Neonatal Kidney Collaborative:

Namasivayam Ambalavanan, Subrata Sarkar, Alison Kent, Jeffery Fletcher, Carolyn L. Abitbol, Marissa DeFreitas, Shahnaz Duara, Jennifer R. Charlton, Jonathan R. Swanson, Carl D’Angio, Ayesa Mian, Erin Rademacher, Maroun J. Mhanna, Rupesh Raina, Deepak Kumar, Jennifer G. Jetton, Patrick D. Brophy, Tarah T. Colaizy, Jonathan M. Klein, Christopher J. Rhee, Juan C. Kupferman, Alok Bhutada, Shantanu Rastogi, Susan Ingraham, F. Sessions Cole, T. Keefe Davis, Lawrence Milner, Alexandra Smith, Mamta Fuloria, Frederick J. Kaskel, Danielle E. Soranno, Jason Gien, Aftab S. Chishti, Sangeeta Hingorani, Michelle Starr, Sunny Juul, Craig S. Wong, Tara DuPont, Robin Ohls, Surender Khokhar, Sofia Perazzo, Patricio E. Ray, Mary Revenis, Sidharth K. Sethi, Smriri Rohatgi, Cherry Mammen, Anne Synnes, Sanjay Wazir, Michael Zappitelli, Robert Woroniecki, and Shanty Sridhar

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41390-019-0579-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Jetton JG, et al. Incidence and outcomes of neonatal acute kidney injury (AWAKEN): a multicentre, multinational, observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2017;1:184–194. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30069-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu RK, Wheeler DS. Kidney-lung cross-talk and acute kidney injury. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2013;28:2239–2248. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selewski David T., Akcan-Arikan Ayse, Bonachea Elizabeth M., Gist Katja M., Goldstein Stuart L., Hanna Mina, Joseph Catherine, Mahan John D., Nada Arwa, Nathan Amy T., Reidy Kimberly, Staples Amy, Wintermark Pia, Boohaker Louis J., Griffin Russell, Askenazi David J., Guillet Ronnie. The impact of fluid balance on outcomes in critically ill near-term/term neonates: a report from the AWAKEN study group. Pediatric Research. 2018;85(1):79–85. doi: 10.1038/s41390-018-0183-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selewski DT, et al. Fluid overload and fluid removal in pediatric patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:2694–2699. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318258ff01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selewski DT, et al. Weight-based determination of fluid overload status and mortality in pediatric intensive care unit patients requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1166–1173. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2231-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arikan AA, et al. Fluid overload is associated with impaired oxygenation and morbidity in critically ill children. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2012;13:253–258. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31822882a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flori HR, et al. Positive fluid balance is associated with higher mortality and prolonged mechanical ventilation in pediatric patients with acute lung injury. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2011;2011:854142. doi: 10.1155/2011/854142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foland JA, et al. Fluid overload before continuous hemofiltration and survival in critically ill children: a retrospective analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2004;32:1771–1776. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000132897.52737.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein SL, et al. Outcome in children receiving continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1309–1312. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein SL, et al. Pediatric patients with multi-organ dysfunction syndrome receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Kidney Int. 2005;67:653–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassinger AB, Wald EL, Goodman DM. Early postoperative fluid overload precedes acute kidney injury and is associated with higher morbidity in pediatric cardiac surgery patients. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2014;15:131–138. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes LW, et al. Outcomes of critically ill children requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. J. Crit. Care. 2009;24:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazle MA, et al. Fluid overload in infants following congenital heart surgery. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2013;14:44–49. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182712799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland SM, et al. Fluid overload and mortality in children receiving continuous renal replacement therapy: the prospective pediatric continuous renal replacement therapy registry. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010;55:316–325. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh W, et al. Association between fluid intake and weight loss during the first ten days of life and risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely low birth weight infants. J. Pediatr. 2005;147:786–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt B, et al. Indomethacin prophylaxis, patent ductus arteriosus, and the risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: further analyses from the Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms (TIPP) J. Pediatr. 2006;148:730–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jetton JG, et al. Assessment of worldwide acute kidney injury epidemiology in neonates: design of a retrospective cohort study. Front. Pediatr. 2016;4:68. doi: 10.3389/fped.2016.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlton, J. R. et al. Late onset neonatal acute kidney injury: results from the AWAKEN study. Pediatr. Res. 85, 339–348 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Kirkley MJ, et al. Acute kidney injury in neonatal encephalopathy: an evaluation of the AWAKEN database. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2019;34:169–176. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-4068-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraut EJ, et al. Incidence of neonatal hypertension from a large multicenter study [Assessment of Worldwide Acute Kidney Injury Epidemiology in Neonates-AWAKEN] Pediatr. Res. 2018;84:279–289. doi: 10.1038/s41390-018-0018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zappitelli M, et al. Developing a neonatal acute kidney injury research definition: a report from the NIDDK neonatal AKI workshop. Pediatr. Res. 2017;82:569–573. doi: 10.1038/pr.2017.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selewski DT, et al. Neonatal acute kidney injury. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e463–e473. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jetton JG, Askenazi DJ. Update on acute kidney injury in the neonate. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2012;24:191–196. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834f62d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alobaidi R, et al. Association between fluid balance and outcomes in critically ill children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:257–268. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dass B, et al. Fluid balance as an early indicator of acute kidney injury in CV surgery. Clin. Nephrol. 2012;77:438–444. doi: 10.5414/CN107278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Askenazi DJ, et al. Fluid overload and mortality are associated with acute kidney injury in sick near-term/term neonate. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2013;28:661–666. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2369-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell, E. F. & Acarregui, M. J. Restricted versus liberal water intake for preventing morbidity and mortality in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD000503 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.de Oliveira FS, et al. Positive fluid balance as a prognostic factor for mortality and acute kidney injury in severe sepsis and septic shock. J. Crit. Care. 2015;30:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teixeira C, et al. Fluid balance and urine volume are independent predictors of mortality in acute kidney injury. Crit. Care. 2013;17:R14. doi: 10.1186/cc12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basu RK, et al. Acute kidney injury based on corrected serum creatinine is associated with increased morbidity in children following the arterial switch operation. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2013;14:e218–e224. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182772f61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SooHoo MM, et al. Acute kidney injury defined by fluid corrected creatinine in neonates after the Norwood procedure. World J. Pediatr. Congenit. Heart Surg. 2018;9:513–521. doi: 10.1177/2150135118775413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mah KE, et al. Fluid overload independent of acute kidney injury predicts poor outcomes in neonates following congenital heart surgery. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2018;33:511–520. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3818-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.