Abstract

Even though cell–cell adhesion molecule carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) is extensively studied since the discovery, the role of CEACAM1 in different cancers is not completely clarified. In the present study, we examined CEACAM1 expression and its association with patient survival in various cancers by analysis of multiple databases. Oncomine database analysis revealed that CEACAM1 expression was upregulated in lung and pancreatic cancers, but downregulated in colorectal and head and neck cancers. PrognoScan and Kaplan‑Meier analyses showed that colorectal cancer patients as well as head and neck cancer patients with high CEACAM1 expression exhibited a higher overall survival rate. STRING analysis identified CEACAM3, CEACAM8, FN1, etc. as CEACAM1 interactors. Gene alteration analysis showed that CEACAM1 mutation predominantly occurred in the N-terminal. Coexpression analysis demonstrated that CEACAM1 had distinct coexpressed genes in different cancers, but KRT protein was consistently coexpressed with CEACAM1 in diverse cancer types. All the observations supported that CEACAM1 can serve as a diagnostic marker for some cancers, such as pancreatic cancer. And high CEACAM1 expression provides a better prognosis for some cancers, such as colorectal and head and neck cancers.

Keywords: CEACAM1, Cancer, Meta analysis, Gene alteration

Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of death worldwide nowadays and accounts for a major public health problem. It is reported that there were 18.1 million new cancer cases and 9.6 million cancer deaths worldwide in 2018 (Bray et al. 2018). Lung, breast, prostate and colorectal cancers are the most commonly occurred cancers worldwide. Lung, liver, stomach, and colorectal cancers are the most common causes of cancer death worldwide (Bray et al. 2018). Even though diagnostic techniques and therapeutic methods have been progressively improved, the quality of patients’ life is still seriously influenced by cancer, which further causes serious economic and social burdens. Therefore, uncovering the underlying mechanisms of cancer, and identifying potential cancer biomarkers to improve diagnosis, therapy and prognosis are urgently needed.

As a cell–cell adhesion molecule detected mostly on leukocytes, epithelia, and endothelia, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) has been extensively studied since discovery. CEACAM1 was reported to participate in differentiation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, and the modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses (Helfrich and Singer 2019; McLeod et al. 2018; Shi et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2016). CEACAM1 is a type-1 transmembrane protein and contains an extracellular N-terminal variable domain, followed by up to three constant C2-like immunoglobulin domains (Beauchemin et al. 1999). The extracellular domains of CEACAM1 play an essential role in the homophilic and heterophilic intercellular adhesion with carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) or other proteins (Dankner et al. 2017; Huang et al. 2015). Since CEACAM1 is the only CEACAM member to possess an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM), it can inhibit signaling during effector protein binding (Beauchemin and Arabzadeh 2013; Beauchemin et al. 1997; Huber et al. 1999).

The CEACAM1 gene generates 12 different isoforms by alternative splicing. Inclusion or exclusion of the CEACAM1 exon 7 differentiates CEACAM1 protein into the two isoforms of long (-L) tail or short (-S) tail, and only the CEACAM1-L isoform contains ITIM motifs (Ieda et al. 2011; Kammerer and Zimmermann 2010). The presence of a particulate tail isoform and the ratios between different isoforms significantly influence the functions of CEACAM1 protein.

Previous studies indicated that CEACAM1 may take an oncogenic or anti-oncogenic function in different cancer types. In > 85% early colorectal adenomas and carcinomas, reduced CEACAM1 expression has been reported (Nollau et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 1997), which indicates a tumor growth inhibitor role of CEACAM1 in colorectal cancer development. In addition, CEACAM1 knockout mice developed a significantly increased number of colonic tumors after tumorigenesis induction (Leung et al. 2006). In contrast, various studies suggest that CEACAM1 is a useful biomarker for pancreatic adenocarcinomas since CEACAM1 is present in both tumor specimens and patient serum (Beauchemin and Arabzadeh 2013; Giulietti et al. 2016; Simeone et al. 2007). However, the precise role of CEACAM1 remains controversial due to the conflicting evidence in some cancers, such as breast cancer (Gerstel et al. 2011; Horst and Wagener 2004). These results indicate that the roles of CEACAM1 depend largely on the type of cancers.

To analyze CEACAM1 expression levels in various cancers and to investigate the role of CEACAM1 in the regulation of tumor development, we evaluated CEACAM1 expression level through the Oncomine database. The correlation between patient survival rate and CEACAM1 expression in different cancer types were examined in the Kaplan–Meier plotter database and Prognoscan database. CEACAM1-interacted proteins and the corresponding pathway networks were identified by STRING database analysis. Genetic alterations of CEACAM1 and its interactors during carcinogenesis, including copy number alterations and mutations were inspected by cBioPortal. Finally, the genes coexpressed with CEACAM1 in various cancer types were identified by Oncomine. Our results suggested that CEACAM1 may serve as a diagnostic marker in pancreatic cancer, and reduced CEACAM1 may be a biomarker in colorectal and head and neck cancers. The prediction role of CEACAM1 in lung and breast cancers is controversial and thus needs to be further clarified.

Materials and methods

Oncomine database analysis

CEACAM1 expression in cancer vs. healthy tissues was analyzed using the “cancer vs. normal” filter in the Oncomine database (https://www.oncomine.org/resource/login.html) (Rhodes et al. 2007, 2004). The criteria for data filtration were set as p < 0.01, fold‑change > 2 and a gene rank percentile < 10%. The advanced analysis criteria were adjusted as follows: p < 0.0001, fold‑change > 2 and gene ranking in the top 10%. The CEACAM1 expression profile in various cancer types was rendered as a heat map. The threshold for coexpression analysis was: p < 0.0001, fold‑change > 2 and gene ranking in the top 10%.

Kaplan–Meier analysis

The Kaplan–Meier plotter database (https://kmplot.com/analysis/) (Gyorffy et al. 2010; Nagy et al. 2018) was utilized to assess the effect of > 54 k genes on survival in 21 cancer types. The largest datasets in Kaplan–Meier plotter database include 6234 breast, 3452 lung, 2190 ovarian and 1440 gastric cancer cases. The primary purpose of this tool is for meta-analysis-based biomarker assessment. The association between the expression levels of CEACAM1 and survival rates in breast, head and neck, and lung cancer were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier plotter. The hazard ratio with a 95% confidence interval and log-rank p-value were calculated.

Prognoscan database analysis

The PrognoScan database (https://dna00.bio.kyutech.ac.jp/PrognoScan/) (Mizuno et al. 2009) was examined to determine the association between CEACAM1 expression levels and patient survival rates in various cancer types. The threshold was set as Cox p < 0.05.

CEACAM1 interactor identification

The search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes/proteins (STRING v11.0) analysis tool (https://string-db.org/) (Szklarczyk et al. 2019) was employed to identify CEACAM1 interacting proteins, with ‘CEACAM1 (Homo sapiens)’ as the query. The minimum required interaction score was set as “highest confidence (0.900)” to improve the result credibility.

Functional enrichment analysis in CEACAM1 interactor network

GO and KEGG analyses for CEACAM1 interactors were performed by the STRING analysis tool. The categories of Molecular Function (GO), Biological Process (GO) and Cellular Component (GO) were examined. The threshold was set as observed gene count > 5, and false discovery rate < 0.05.

cBioPortal database analysis

The cBioPortal (https://cbioportal.org) was retrieved to explore mutations and copy number alterations (CNAs) of the genes of CEACAM1 and its interactors in various cancer types. The cBioPortal is a website used for investigating, visualizing and analyzing multidimensional cancer genomics data (Cerami et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2013). The threshold was set as (1) the number of cases in dataset ≥ 50, alteration frequency > 15% for all-gene-combined query; (2) the number of cases in dataset ≥ 20, alteration frequency > 1% for CEACAM1 query.

Statistical analysis

Survival curves were generated by Prognoscan and Kaplan‑Meier plots. Heatmaps were generated by Oncomine. All results were reviewed with a p value from a log‑rank test. Oncomine reported the statistical significance with a p value.

Results

CEACAM1 expression pattern is heterozygous in various cancer types

CEACAM1 expression patterns between tumor and normal tissues in pan-cancer were examined in Oncomine database. The “Cancer vs. Normal” filter was utilized to screen the studies in which CEACAM1 was differentially expressed. The criteria for data filtering were: p < 0.01, fold change > 2 or p < 0.0001, fold change > 2; gene rank percentile of top 10%. Totally, 81 cancer studies demonstrated significantly differential CEACAM1 expression (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

CEACAM1 expression levels in multiple cancer types compared with that in health controls. The left red column indicates the number of datasets in which CEACAM1 expression was upregulated in cancer and the right blue column represents the number of datasets in which CEACAM1 expression was downregulated in cancer tissues compared with normal tissues. The threshold was set as: a p < 0.01, fold change > 2 and a gene rank percentile of 10%, and b p < 0.0001, fold change > 2 and a gene rank percentile of 10%. The bottom legend refers to the gene rank percentile for each cell. The color of each cell is determined by the best gene rank percentile for the analyses within the cell. Significant Unique Analyses indicates the number of datasets with significant difference under the corresponding threshold. Total Unique Analyses indicates the number of total analyzed datasets, with or without significant difference. CEACAM1, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1, also known as CD66a; CNS, central nervous system

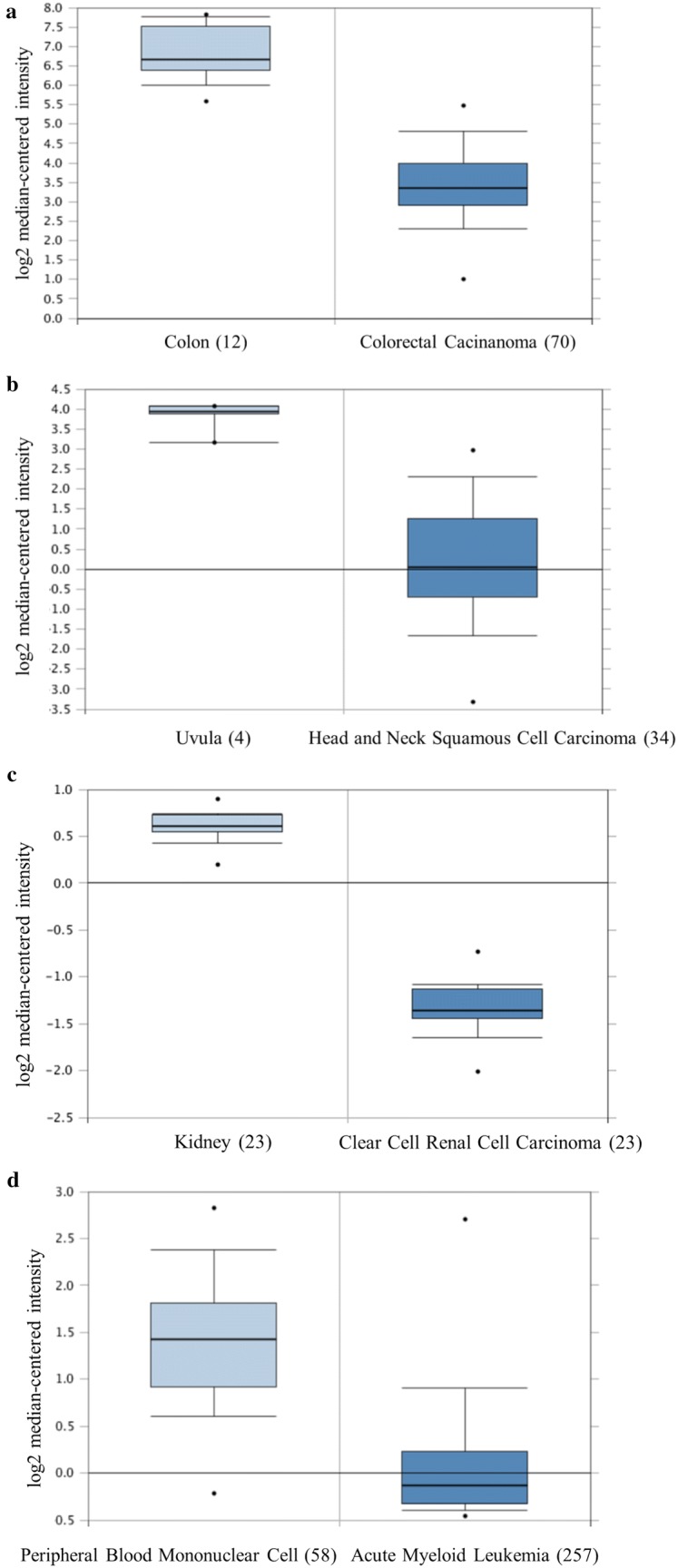

Compared with normal tissue, CEACAM1 was over-expressed in 19 tumor studies (9 tumor types), and under-expressed in 62 cancer studies (11 tumor types) (Fig. 1a). In lung and pancreatic cancers, CEACAM1 expression was upregulated compared to normal tissues; in colorectal, head and neck, kidney, cervical, esophageal, prostate and sarcoma cancer tissues, CEACAM1 expression was downregulated (Fig. 2). However, in breast cancer, leukemia and lymphoma tissues, CEACAM1 expression was heterozygous: both upregulation and downregulation were observed in the studies on these cancers. These results indicated that relative higher/lower CEACAM1 expression level may serve as a diagnostic biomarker depending on the cancer type.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of CEACAM1 expression in different cancers according to the Oncomine database. CEACAM1 expression levels in health (left column) and cancer tissue (right column) were retrieved from the Oncomine database. The fold changes of CEACAM1 in different types of cancers were identified from the analysis. The fold changes of CEACAM1 expression in a colorectal carcinoma compared with normal colon tissues from Hong Colorectal dataset; b head and neck squamous cell carcinoma compared with normal uvula tissues from Cromer Head-Neck dataset; c clear cell renal cell carcinoma compared with normal kidney tissues from Jones Renal dataset; d acute myeloid leukemia compared with normal peripheral blood mononuclear cell from Haferlach Leukemia 2 dataset; e lung adenocarcinoma compared with normal lung tissues from Beer Lung dataset; f pancreatic carcinoma compared with normal pancreas tissues from Pei Pancreas dataset; g ductal breast carcinoma compared with normal breast tissues from Ma Breast 4 dataset. The number in the parentheses following each group represented the number of samples in each group. Fold change > 0 indicates higher CEACAM1 expression in cancer tissue, while fold change < 0 indicates lower CEACAM1 expression in cancer tissue

Genetic expression levels of CEACAM1 influence patient survival in some cancer types

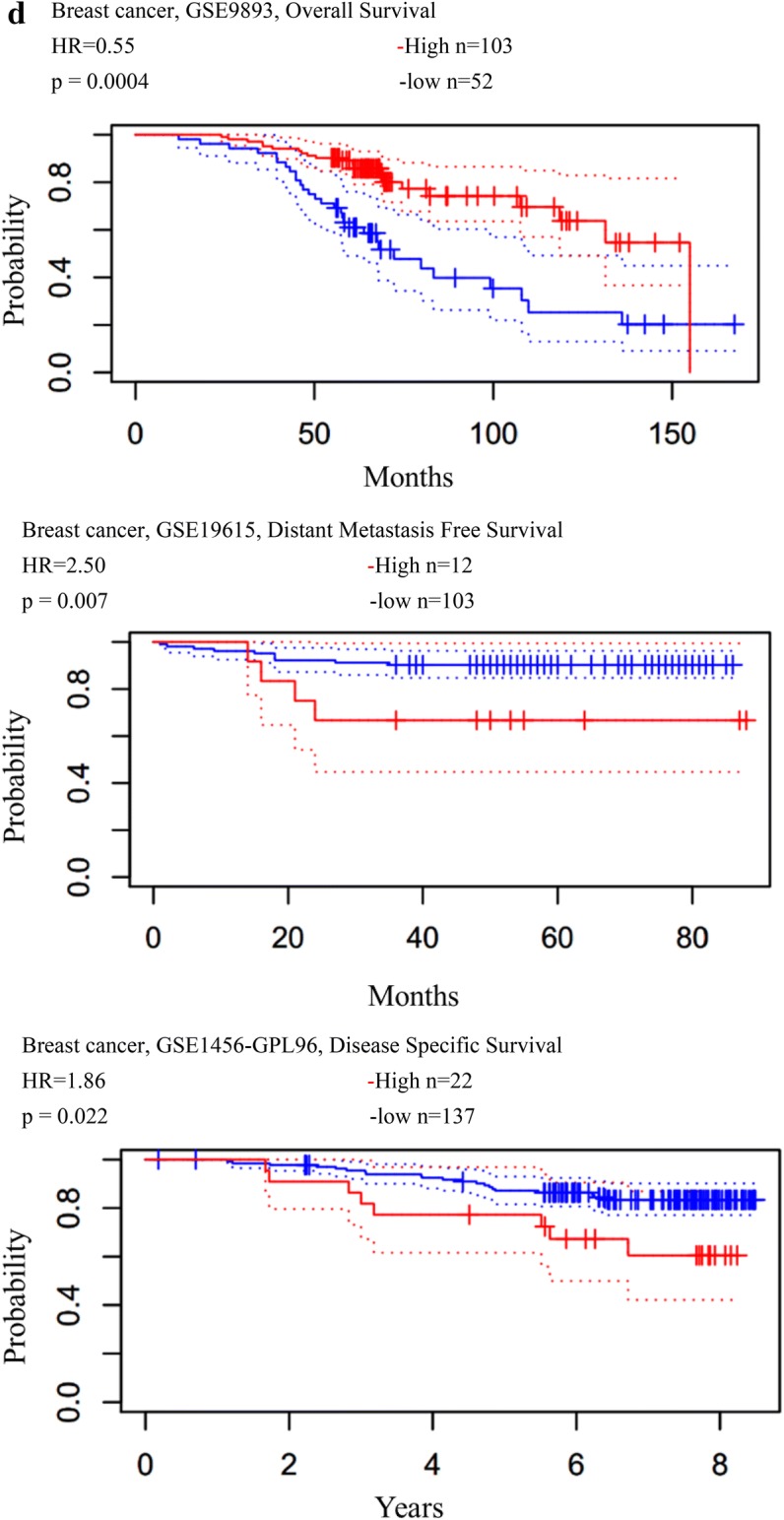

The association between CEACAM1 expression levels and survival rates of patients with colorectal, head and neck, lung and breast cancer was examined by PrognoScan and Kaplan‑Meier analysis (Figs. 3, 4) (Mizuno et al. 2009; Nagy et al. 2018). Colorectal cancer patients with high CEACAM1 expression demonstrated significantly higher overall survival (OS) rate compared to patients with low CEACAM1 expression (Fig. 3a). Head and neck cancer patients with high CEACAM1 expression exhibited higher relapse-free survival (RFS) (Fig. 3b) and OS rates (Fig. 4b). The role of CEACAM1 in lung cancer patients was still controversial: different probes of CEACAM1 showed the nearly opposite results in the context of OS and RFS rates for lung cancer patients (Figs. 3c, 4c). Breast cancer patients with enriched CEACAM1 exhibited higher OS (Figs. 3d, 4a) and RFS (Fig. 3d) rates, but lower distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) rates (Fig. 3d). Thus, the role of CEACAM1 in lung and breast cancer patient survival remains to be further examined.

Fig. 3.

Association between the survival rates of cancer patients and CEACAM1 expressions based on PrognoScan database analysis. Survival curves were plotted based on CEACAM1 expression levels, comparing patients with high (red) and low (blue) CEACAM1 expression levels. Analysis was performed for a colorectal, b head and neck, c lung, and d breast cancer. n the number of patients. HR hazard ratio

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for patients with different cancers according to CEACAM1 expression levels. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated to compare the survival rates of patients with high (red) and low (black) CEACAM1 expression levels. Cancer type: a breast, b head-neck, c lung cancer. HR hazard ratio

The association between CEACAM1 expression and cancer patient survival in the PrognoScan database was summarized in Table 1. Data with Cox p-value < 0.05 was listed. In addition to the above cancer types, blood cancer patients with lower CEACAM1 expression were correlated with higher OS rate, while ovarian cancer patient with higher CEACAM1 expression tended to have higher OS rate. Thus, the role of CEACAM1 is not consistent and is dependent on the cancer type discussed.

Table 1.

Association of CEACAM1 expression level with the survival of patients with cancer

| Cancer type | n | COX P-value | HR [95% CI] | Endpoint | Dataset | Probe ID | ln(HR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood cancer | 180 | 3.59 × 10–3 | 1.73 [1.20–2.51] | Overall survival | GSE16131-GPL96 | 206576_s_at | 0.55 |

| Blood cancer | 34 | 1.24 × 10–2 | 2.08 [1.17–3.70] | Overall survival | GSE8970 | 210610_at | 0.73 |

| Breast cancer | 155 | 4.02 × 10–4 | 0.55 [0.39–0.77] | Overall survival | GSE9893 | 17,208 | − 0.6 |

| Breast cancer | 115 | 6.87 × 10–3 | 2.50 [1.29–4.87] | Distant metastasis free survival | GSE19615 | 211883_x_at | 0.92 |

| Breast cancer | 286 | 1.65 × 10–2 | 0.71 [0.53–0.94] | Distant metastasis free survival | GSE2034 | 210610_at | − 0.35 |

| Breast cancer | 54 | 1.79 × 10–2 | 0.52 [0.30–0.89] | Distant metastasis free survival | GSE2990 | 209498_at | − 0.65 |

| Breast cancer | 286 | 1.89 × 10–2 | 0.73 [0.56–0.95] | Distant metastasis free survival | GSE2034 | 206576_s_at | − 0.31 |

| Breast cancer | 159 | 2.24 × 10–2 | 1.86 [1.09–3.16] | Disease specific survival | GSE1456-GPL96 | 211889_x_at | 0.62 |

| Breast cancer | 159 | 2.37 × 10–2 | 2.23 [1.11–4.45] | Disease specific survival | GSE1456-GPL96 | 211883_x_at | 0.80 |

| Breast cancer | 159 | 2.59 × 10–2 | 1.97 [1.09–3.59] | Relapse free survival | GSE1456-GPL96 | 211883_x_at | 0.68 |

| Breast cancer | 115 | 3.35 × 10–2 | 0.15 [0.03–0.86] | Distant metastasis free survival | GSE19615 | 210610_at | − 1.89 |

| Breast cancer | 286 | 4.11 × 10–2 | 0.65 [0.43–0.98] | Distant metastasis free survival | GSE2034 | 211883_x_at | − 0.43 |

| Breast cancer | 115 | 4.74 × 10–2 | 0.42 [0.18–0.99] | Distant metastasis free survival | GSE19615 | 209498_at | − 0.86 |

| Colorectal cancer | 55 | 3.40 × 10–2 | 0.22 [0.05–0.89] | Overall survival | GSE17537 | 210610_at | − 1.52 |

| Head and neck cancer | 28 | 4.53 × 10–2 | 0.00 [0.00–0.84] | Relapse free survival | GSE2837 | g4502404_3p_x_at | − 8.12 |

| Lung cancer | 82 | 2.74 × 10–2 | 0.71 [0.53–0.96] | Overall survival | jacob-00182-CANDF | 211883_x_at | − 0.34 |

| Lung cancer | 204 | 2.86 × 10–2 | 1.56 [1.05–2.32] | Relapse free survival | GSE31210 | 211889_x_at | 0.44 |

| Lung cancer | 204 | 3.81 × 10–2 | 0.54 [0.30–0.97] | Relapse free survival | GSE31210 | 210610_at | − 0.62 |

| Lung cancer | 204 | 4.02 × 10–2 | 1.49 [1.02–2.19] | Relapse free survival | GSE31210 | 211883_x_at | 0.40 |

| Ovarian cancer | 278 | 4.18 × 10–3 | 0.64 [0.47–0.87] | Overall survival | GSE9891 | 206576_s_at | − 0.45 |

| Ovarian cancer | 278 | 8.22 × 10–3 | 0.79 [0.66–0.94] | Overall survival | GSE9891 | 209498_at | − 0.24 |

| Ovarian cancer | 278 | 1.11 × 10–2 | 0.61 [0.42–0.89] | Overall survival | GSE9891 | 211883_x_at | − 0.49 |

| Ovarian cancer | 278 | 1.45 × 10–2 | 0.65 [0.46–0.92] | Overall survival | GSE9891 | 211889_x_at | − 0.43 |

| Ovarian cancer | 133 | 2.52 × 10–2 | 0.77 [0.62–0.97] | Overall survival | DUKE-OC | 209498_at | − 0.26 |

| Ovarian cancer | 81 | 3.53 × 10–2 | 0.58 [0.35–0.96] | Overall survival | GSE8841 | 3988 | − 0.54 |

| Prostate cancer | 281 | 2.04 × 10–2 | 0.83 [0.70–0.97] | Overall survival | GSE16560 | DAP3_5091 | − 0.19 |

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

Proteins associated with CEACAM1 and interactor network analysis

Functional proteins interacted with CEACAM1 were identified by the STRING analysis tool. The ten predicted interactors of CEACAM1 were listed as follows (Fig. 5): CEACAM3 (Carcinoembryonic Antigen Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 3), CEACAM8 (Carcinoembryonic Antigen Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 8), FN1 (Fibronectin 1), HVCN1 (Hydrogen Voltage Gated Channel 1), PTAFR (Platelet Activating Factor Receptor), LAIR1 (Leukocyte Associated Immunoglobulin Like Receptor 1), ITGAM (Integrin Subunit Alpha M), MS4A3 (Membrane Spanning 4-Domains A3), CD177, CD300A. The protein–protein interaction (PPI) for CEACAM1 network was significantly enriched (p < 1.95*10−11).

Fig. 5.

Proteins interacted with CEACAM1 by STRING database. Each node represented a protein. Each connection represented an interaction between proteins. The resulting network contained 42 functional associations between the 11 proteins. The line color indicates the type of interaction evidence. CEACAM3, Carcinoembryonic Antigen Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 3; CEACAM8, Carcinoembryonic Antigen Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 8; FN1, Fibronectin 1; HVCN1, Hydrogen Voltage Gated Channel 1; PTAFR, Platelet Activating Factor Receptor; LAIR1, Leukocyte Associated Immunoglobulin Like Receptor 1; ITGAM, Integrin Subunit Alpha M; MS4A3, Membrane Spanning 4-Domains A3

GO analysis was examined to reveal the enriched pathways for CEACAM1 interactors. The categories of Cellular Component (GO) and Biological Process (GO) were demonstrated in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. No significant pathway enrichment was observed in the category Molecular Function (GO) or KEGG pathways.

Table 2.

Enriched GO terms (Cellular Component) for CEACAM1 interactors

| #term ID | Term description | Observed gene count | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0030667 | Secretory granule membrane | 10 | 9.85 × 10–16 |

| GO:0035579 | Specific granule membrane | 8 | 2.71 × 10–15 |

| GO:0030141 | Secretory granule | 11 | 3.17 × 10–14 |

| GO:0070821 | Tertiary granule membrane | 7 | 1.04 × 10–13 |

| GO:0044433 | Cytoplasmic vesicle part | 11 | 4.74 × 10–12 |

| GO:0005886 | Plasma membrane | 11 | 2.71 × 10–6 |

Observed gene count > 5, false discovery rate < 0.05

Table 3.

Enriched GO terms (Biological Process) for CEACAM1 interactors

| #term ID | Term description | Observed gene count | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0045055 | Regulated exocytosis | 11 | 1.02 × 10–13 |

| GO:0043312 | Neutrophil degranulation | 10 | 3.04 × 10–13 |

| GO:0002376 | Immune system process | 11 | 3.19 × 10–9 |

| GO:0050900 | Leukocyte migration | 6 | 1.72 × 10–7 |

| GO:0040011 | Locomotion | 7 | 1.46 × 10–5 |

| GO:1903530 | Regulation of secretion by cell | 6 | 1.50 × 10–5 |

| GO:0007155 | Cell adhesion | 6 | 4.95 × 10–5 |

| GO:0050776 | Regulation of immune response | 6 | 5.67 × 10–5 |

| GO:0051049 | Regulation of transport | 7 | 1.70 × 10–4 |

| GO:0050896 | Response to stimulus | 11 | 6.10 × 10–4 |

| GO:0048583 | Regulation of response to stimulus | 7 | 1.67 × 10–2 |

Observed gene count > 5, false discovery rate < 0.05

Alterations of CEACAM1 and its interactors in diverse cancer types

Totally, 23,450 patients/25,013 samples in 85 cancer studies for colorectal, head and neck, kidney, leukemia, lung, pancreatic, breast and lymphoma cancer were analyzed by the cBioPortal tool, to detect the mutations and CNAs of genes of CEACAM1 and its 10 interactors.

Totally, in 13 of 85 studies, the number of cases is ≥ 50 and the all-gene-combined alteration frequency is > 15%. The alteration frequency ranged between 15.09% and 36.70% (Table 4) (Bhandari et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2016; Ellrott et al. 2018; Gao et al. 2018; Giannakis et al. 2016; Hoadley et al. 2018; Imielinski et al. 2012; Jamal-Hanjani et al. 2017; Lefebvre et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2018; Morin et al. 2011; Pereira et al. 2016; Sanchez-Vega et al. 2018; Seshagiri et al. 2012; Taylor et al. 2018; Witkiewicz et al. 2015). Mutations occurred in several domains of the CEACAM1 protein, predominantly in the N-terminal. Database analysis revealed that the most critical mutation site A94T, located in the V-set domain at the N-terminal (Fig. 6). Higher mutation rate in the N-terminal of CEACAM1 protein indicated the functional significance of the N-terminal.

Table 4.

Alteration frequency of a signature for 11 genes (CEACAM1, CEACAM3, CEACAM8, FN1, HVCN1, PTAFR, LAIR1, ITGAM, MS4A3, CD177 and CD300A)

| Cancer type | n | Data source | Frequency (%) | Amplification (%) | Deletion (%) | Mutation (%) | Multiple alteration (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreas | 109 | UTSW | 36.70 | 19.27 | 12.84 | 3.67 | 0.92 |

| Breast | 237 | The MBC Project | 29.54 | 8.02 | 16.03 | 4.22 | 1.27 |

| NSCLC | 1144 | TCGA 2016 | 22.29 | 4.90 | 0.79 | 15.3 | 1.31 |

| Lung adeno | 183 | Broad | 21.31 | 3.83 | 0.55 | 16.39 | 0.55 |

| Breast | 1099 | TCGA | 18.47 | 14.38 | 1.46 | 2.18 | 0.45 |

| Colorectal | 72 | Genentech | 18.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 18.06 | 0.00 |

| Tracerx | 327 | NSCLC 2017 | 17.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 17.13 | 0.00 |

| BRCA | 216 | INSERM 2016 | 16.67 | 10.19 | 1.39 | 3.24 | 1.85 |

| Lung squ | 502 | TCGA | 16.14 | 7.37 | 1.59 | 5.98 | 1.20 |

| Colorectal | 619 | DFCI 2016 | 15.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 15.67 | 0.00 |

| Breast | 2173 | METABRIC 2016 | 15.55 | 14.86 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| NHL | 53 | BCGSC 2013 | 15.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 15.09 | 0.00 |

TCGA The Cancer Genome Atlas

Fig. 6.

Mutation diagram of CEACAM1 across protein domains in pan-cancer. The diagram presents the mutation sites and frequencies of CEACAM1. Green circles: missense mutations; black circles: truncating mutations, including nonsense, nonstop, frameshift deletion, frameshift insertion, splice site. In case of different mutation types at a single position, color of the circle is determined with respect to the most frequent mutation type. The higher the value of the vertical axis is, the higher the mutation rate is. aa, amino acid

In addition, in 14 of 85 studies, ≥ 20 cases are included and CEACAM1 alteration frequency is > 1% (Bhandari et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2016; Ellrott et al. 2018; Gao et al. 2018; Gardner et al. 2017; Ho et al. 2013; Hoadley et al. 2018; Imielinski et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2018; Sanchez-Vega et al. 2018; Shah et al. 2012; Taylor et al. 2018; Witkiewicz et al. 2015). Pancreatic cancer and small cell lung cancer rendered the highest alteration frequencies for CEACAM1, with amplification and mutation as their dominant alteration type, respectively (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Mutation and CNA analysis of CEACAM1 in different cancer subtypes determined by cBioPortal database analysis. The alterations included amplifications (red), deep deletions (blue), multiple alterations (grey) or mutations (green). Cancer studies containing > 20 cases were selected and only alteration frequencies > 1% are presented. “ + ” indicates the existence of corresponding alteration type; “−” indicates lack of corresponding alteration type. Each bar represents a dataset for a particular cancer subtype. CNA copy number alteration, SCLC small cell lung cancer, DLBC diffuse large B cell lymphoma, MBC metastatic breast cancer, ACyC adenoid cystic carcinoma, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer

The alterations in the 10 CEACAM1 interactor genes were next examined in pancreatic cancer, small cell lung cancer, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, and breast cancer patients. CEACAM3, CEACAM8, LAIR1, and CD177 were found to be mostly altered in pancreatic cancer patients; the missense mutation of FN1, PTAFR, ITGAM and CD177 contributed to most of CEACAM1 alterations in small cell lung cancer dataset; LAIR1 deletion was the most popular alteration type in the breast cancer dataset; however, no dominant alteration type was discovered in the diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBC) patients (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Mutation of CEACAM1 and associated genes in the datasets of a pancreatic, b lung, c lymphoma and d breast cancer. The Oncoprint feature of cBioPortal was utilized to determine the mutation and copy number alteration (CNA) frequency of each individual gene. The percentages of alterations in CEACAM1, CEACAM3, CEACAM8, FN1, HVCN1, PTAFR, LAIR1, ITGAM, MS4A3, CD177 and CD300A genes are presented

CEACAM1 coexpression profiling in different cancer types

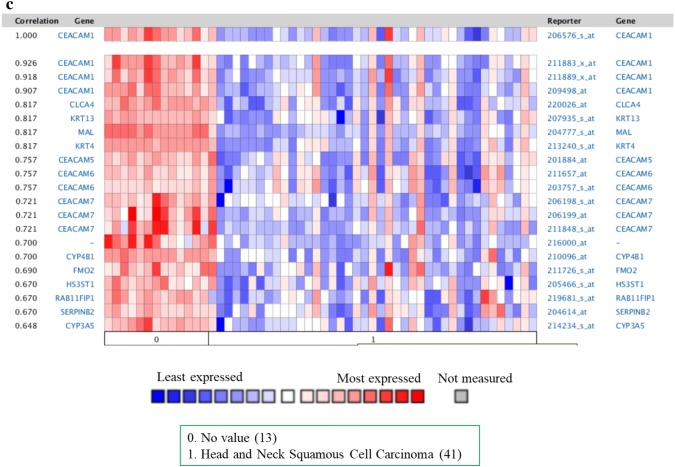

Coexpression gene profiles for CEACAM1 in breast, colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, lung, head and neck carcinoma were analyzed by Oncomine (Fig. 9). The co-expressed genes with CEACAM1 in different cancers were distinct, which may serve as the fingerprint for different cancer types. However, some genes consistently coexpressed with CEACAM1 in diverse cancer types, such as KRT protein, demonstrating its functional correlation with CEACAM1.

Fig. 9.

CEACAM1 coexpressed genes in different cancers. Cell lines: a Gyorffy cell line 2, including breast cancer cells, gastric cancer cells, colon cancer cells, and pancreatic cancer cells; b Nguyen cells; c Ginos head and neck cancer cells. Blue cells indicated low expression, and red cells indicated high expression. Colors are z-score normalized to depict relative values within rows. They cannot be used to compare values between rows

Discussion

CEACAM1 is an extensively studied cell–cell adhesion molecule detected in leukocytes, epithelia, and endothelia. This molecule plays an important role in differentiation, angiogenesis, apoptosis and immune responses (Helfrich and Singer 2019; McLeod et al. 2018; Shi et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2016). Even though an increased number of studies indicated that CEACAM1 may take an oncogenic or anti-oncogenic function in various cancer development, the controversial evidence often rendered the role of CEACAM1 inconclusive. In this study, we summarized the expressions of CEACAM1 in different cancers based on our review of a significant number of traceable human cancer studies, using various cancer databases and cancer analysis tools. Our results supported that CEACAM1 may serve as a diagnostic marker in pancreatic cancer; in contrast, lack of CEACAM1 may be a biomarker in colorectal and head and neck cancers. The role of CEACAM1 in lung and breast cancers is complicated and needs further examination. Current studies suggested that CEACAM1 also participated in the immune checkpoint inhibition (Blake et al. 2016; Dankner et al. 2017). Therefore, CEACAM1 is a promising diagnostic marker and immunotherapy target for certain cancers.

The controversial role of CEACAM1 in some cancer types, such as breast and lung cancers, maybe due to the fact that the roles of different CEACAM1 isoforms are not separately investigated. As is known, 12 isoforms of CEACAM1 exist. The presence of a specific isoform and the ratios between different isoforms contribute to the function of CEACAM1. Some isoforms may play opposite roles in the same cancer type. Therefore, it is necessary to scrutinize the correlation between expression of each CEACAM1 isoform and survival of cancer patients, to completely uncover the role of each CEACAM1 isoform in different cancer types. It is possible that only one or several CEACAM1 isoform(s), or a particular isoform ratio, serves as the biomarker(s) for a particular cancer type. The clarification of this would greatly promote the importance and accuracy of CEACAM1 as biomarkers.

Even though different cancer subtypes were analyzed in this study, different progression stages of cancer were not fully reviewed. It is possible that CEACAM1 only plays a differential role in a specific progression stage. It is reported that even though CEACAM1 expression was considerably downregulated within the epithelia in the early phases of some solid tumors, it had been linked lately to the progression of malignancy and metastatic spread (Calinescu et al. 2018). Thus, it is worth further analysis to illustrate during which stages the role of CEACAM1 is the most significant. The databases utilized in this study do not provide such delicate functionality for analysis. Thus, to complete this comprehensive analysis, deep data mining is required, which is beyond the database analysis alone.

In addition, the gender influence is not taken into consideration in our analysis. It is feasible that the role of CEACAM1 is not the same between males and females. Further analysis is required to reveal whether the role of CEACAM1 is influenced by sex in different cancer types.

Besides, only the expression and differential role of CEACAM1 in cancer was analyzed in our study. However, the underlying mechanism is even more important. CEACAM1-L is reported to transduce signaling through the binding of ITIM to SHP1/2, but the mechanism of CEACAM1-S is still to be determined (Zhu et al. 2019). In breast cancer, it was reported that CEACAM1 can function through miRNA to regulate the morphogenesis of healthy mammary tissues (Weng et al. 2016). The clarification of the mechanism is worth further study.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the data contributors of the TCGA, Oncomine, Kaplan–Meier plotter, Prognoscan, STRING and cBioPortal databases. The enormous data in these databases are the foundation of deep exploration, multidimensional analysis and delicate visualization across multiple cancers. Additionally, we acknowledge Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LQ18C010005) for supporting this work.

Author contributions

CW and YW designed the study, statistically analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript, CW and XH collected the data, YW revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

References

- Beauchemin N, Arabzadeh A. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules (CEACAMs) in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Metast Rev. 2013;32:643–671. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin N, Kunath T, Robitaille J, et al. Association of biliary glycoprotein with protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in malignant colon epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:783–790. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin N, Draber P, Dveksler G, et al. Redefined nomenclature for members of the carcinoembryonic antigen family. Exp Cell Res. 1999;252:243–249. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari V, Hoey C, Liu LY, et al. Molecular landmarks of tumor hypoxia across cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51:308–318. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake SJ, Stannard K, Liu J, et al. Suppression of metastases using a new lymphocyte checkpoint target for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:446–459. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-15-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calinescu A, Turcu G, Nedelcu RI, et al. On the dual role of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) in human malignancies. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2018/7169081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Alexandrov A, Kim J, et al. Distinct patterns of somatic genome alterations in lung adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2016;48:607–616. doi: 10.1038/ng.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:960–960. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-12-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankner M, Gray-Owen SD, Huang YH, et al. CEACAM1 as a multi-purpose target for cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1328336. doi: 10.1080/2162402x.2017.1328336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellrott K, Bailey MH, Saksena G, et al. Scalable open science approach for mutation calling of tumor exomes using multiple genomic pipelines. Cell Syst. 2018;6:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JJ, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao QS, Liang WW, Foltz SM, et al. Driver fusions and their implications in the development and treatment of human cancers. Cell Rep. 2018;23:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EE, Lok BH, Schneeberger VE, et al. Chemosensitive relapse in small cell lung cancer proceeds through an EZH2-SLFN11 axis. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel D, Wegwitz F, Jannasch K, et al. CEACAM1 creates a pro-angiogenic tumor microenvironment that supports tumor vessel maturation. Oncogene. 2011;30:4275–4288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakis M, Mu XJ, Shukla SA, et al. Genomic correlates of immune-cell infiltrates in colorectal carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1206–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulietti M, Occhipinti G, Principato G, et al. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis reveals key genes involved in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma development. Cell Oncol. 2016;39:379–388. doi: 10.1007/s13402-016-0283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Tr. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich I, Singer BB. Size matters: the functional role of the ceacam1 isoform signature and its impact for nk cell-mediated killing in melanoma. Cancers. 2019;11:356. doi: 10.3390/cancers11030356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AS, Kannan K, Roy DM, et al. The mutational landscape of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:791. doi: 10.1038/ng.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoadley KA, Yau C, Hinoue T, et al. Cell-of-origin patterns dominate the molecular classification of 10,000 tumors from 33 types of cancer. Cell. 2018;173:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst AK, Wagener C. CEA-Related CAMs. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2004 doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68170-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YH, Zhu C, Kondo Y, et al. CEACAM1 regulates TIM-3-mediated tolerance and exhaustion. Nature. 2015;517:386–U566. doi: 10.1038/nature13848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M, Izzi L, Grondin P, et al. The carboxyl-terminal region of biliary glycoprotein controls its tyrosine phosphorylation and association with protein-tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:335–344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieda J, Yokoyama S, Tamura K, et al. Re-expression of CEACAM1 long cytoplasmic domain isoform is associated with invasion and migration of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1351–1361. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS, et al. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 2012;150:1107–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, McGranahan N, et al. Tracking the evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2017;376:2109–2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer R, Zimmermann W. Coevolution of activating and inhibitory receptors within mammalian carcinoembryonic antigen families. BMC Biol. 2010;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre C, Bachelot T, Filleron T, et al. Mutational profile of metastatic breast cancers: a retrospective analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung N, Turbide C, Olson M, et al. Deletion of the carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (Ceacam1) gene contributes to colon tumor progression in a murine model of carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2006;25:5527–5536. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JF, Lichtenberg T, Hoadley KA, et al. An integrated TCGA pan-cancer clinical data resource to drive high-quality survival outcome analytics. Cell. 2018;173:400–416. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod RL, Angagaw MH, Baral TN, et al. Characterization of murine CEACAM1 in vivo reveals low expression on CD8(+) T cells and no tumor growth modulating activity by anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1. Oncotarget. 2018;9:34459–34470. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H, Kitada K, Nakai K, et al. PrognoScan: a new database for meta-analysis of the prognostic value of genes. Bmc Med Genomics. 2009;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ, et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. 2011;476:298–303. doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Lanczky A, Menyhart O, et al. Validation of miRNA prognostic power in hepatocellular carcinoma using expression data of independent datasets. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27521-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollau P, Scheller H, KonaHorstmann M, et al. Expression of CD66a (human C-CAM) and other members of the carcinoembryonic antigen gene family of adhesion molecules in human colorectal adenomas. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2354–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira B, Chin SF, Rueda OM, et al. The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refine their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Mahavisno V, et al. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia. 2007;9:166–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.07112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vega F, Mina M, Armenia J, et al. The molecular landscape of oncogenic signaling pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cancer Res. 2018;78:3302. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2018-3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshagiri S, Stawiski EW, Durinck S, et al. Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature. 2012;488:660. doi: 10.1038/nature11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SP, Roth A, Goya R, et al. The clonal and mutational evolution spectrum of primary triple-negative breast cancers. Nature. 2012;486:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature10933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi JF, Xu SX, He P, et al. Expression of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1(CEACAM1) and its correlation with angiogenesis in gastric cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210:473–476. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone DM, Ji B, Banerjee M, et al. CEACAM1, a novel serum biomarker for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2007;34:436–443. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3180333ae3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AM, Shih J, Ha G, et al. Genomic and functional approaches to understanding cancer aneuploidy. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:676–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen Y, Yan Y, et al. Loss of CEACAM1, a tumor-associated factor, attenuates post-infarction cardiac remodeling by inhibiting apoptosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21972. doi: 10.1038/srep21972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng CY, Nguyen T, Shively JE. miRNA-342 regulates CEACAM1-induced lumen formation in a three-dimensional model of mammary gland morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:16777–16786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.710152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewicz AK, McMillan EA, Balaji U, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic cancer defines genetic diversity and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6744. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhou W, Velculescu VE, et al. Gene expression profiles in normal and cancer cells. Science. 1997;276:1268–1272. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YC, Song DL, Song YL, et al. Interferon gamma induces inflammatory responses through the interaction of CEACAM1 and PI3K in airway epithelial cells. J Transl Med. 2019;17:147. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1894-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]