Abstract

School nurses encounter many students presenting with mental health needs. However, school nurses report that they need additional training and resources to be able to support student mental health. This study involved a multilevel, stakeholder-driven process to refine the Mental Health Training Intervention for Health Providers in Schools (MH-TIPS), an in-service training and implementation support system for school health providers, including school nurses, to increase their competence in addressing student mental health concerns. Findings highlighted the importance of mental health content including assessment, common factors of positive therapeutic mental health interactions, common elements of evidence-based mental health practice, and resource and referral mapping. Additionally, multifaceted ongoing professional development processes were indicated. Study findings indicate that, with recommended modifications, the MH-TIPS holds promise as a feasible, useful intervention to support school nurse practice and ultimately impact student mental health and educational outcomes.

Keywords: mental health, school nurses, continuing education, professional development

School nurses play a critical role in the health and mental health care of students and are integral members of a multidisciplinary comprehensive school mental health team (Bohnenkamp, Bobo, & Stephan, 2015; Ravenna & Clever, 2016). It is estimated that school nurses spend approximately 33% of their time addressing student mental health (Ravenna & Clever, 2016; Stephan & Connors, 2013). Moreover, it is the position of the National Association of School Nurses (NASN, 2017) that mental health is critical to academic success and that school nurses collaborate with school personnel as part of the coordinated school mental health team. School mental health involves an interdisciplinary approach to care with collaboration between school and community mental health providers (e.g., social workers, counselors, and psychologists), school nurses, students, and families (Bohnenkamp et al., 2015; Connors et al., 2016). Each collaborator plays a unique role in mental health care, including school nurses, who play a pivotal role in the continuum of care within a school building (Cowan, Vaillan-court, Rossen, & Pollitt, 2013). Specifically, the NASN position statement on behavioral health indicates that school nurses coordinate with an interdisciplinary team in the assessment, identification, intervention, referral, and follow-up of children in need of mental health services (NASN, 2017).

Despite the documented role of school nurses in addressing student mental health concerns, school nurses report that they would benefit from additional education in counseling skills and mental health (Ravenna & Cleaver, 2016). Previous efforts to support school nurse mental health professional development are limited and typically include educational training on a single subject only (e.g., suicide prevention), which constrains generalizability to the broad spectrum of presenting mental health concerns in schools (Allison, Nativio, Mitchell, Ren, & Yuhasz, 2014). Additionally, existing training opportunities frequently lack ongoing training and implementation support to help school nurses maintain and utilize the skills they have learned (Beidas, Edmunds, Marcus, & Kendall, 2012; Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010).

To address this need, the national Center for School Mental Health at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in partnership with the NASN and the Center for Mental Health Services in Pediatric Primary Care at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health developed a training program for school health providers, including school nurses, that incorporates a comprehensive approach to professional development on mental health skills and implementation support. The program, entitled the Mental Health Training Intervention for Health Providers in Schools (MH-TIPS), is an in-service training and implementation support system for school health providers aimed at enhancing their competence in managing the needs of students with or at risk for emotional and behavioral difficulties that interfere with learning.

The study described in this article was the first phase in the multiphase development and evaluation of MH-TIPS. The purpose of this study was to use a multilevel stakeholder-driven process to refine the MH-TIPS training intervention to be relevant, effective, and feasible based on real-world practice conditions. This study garnered input from experts in the field of school nursing, with direct expertise in professional development and mental health, in addition to school nurse practitioners. A mixed-method approach was selected to allow for a thorough understanding of how to best tailor the existing MH-TIPS content and structure and receive detailed feedback and suggestions about areas for intervention improvement to inform intervention refinement.

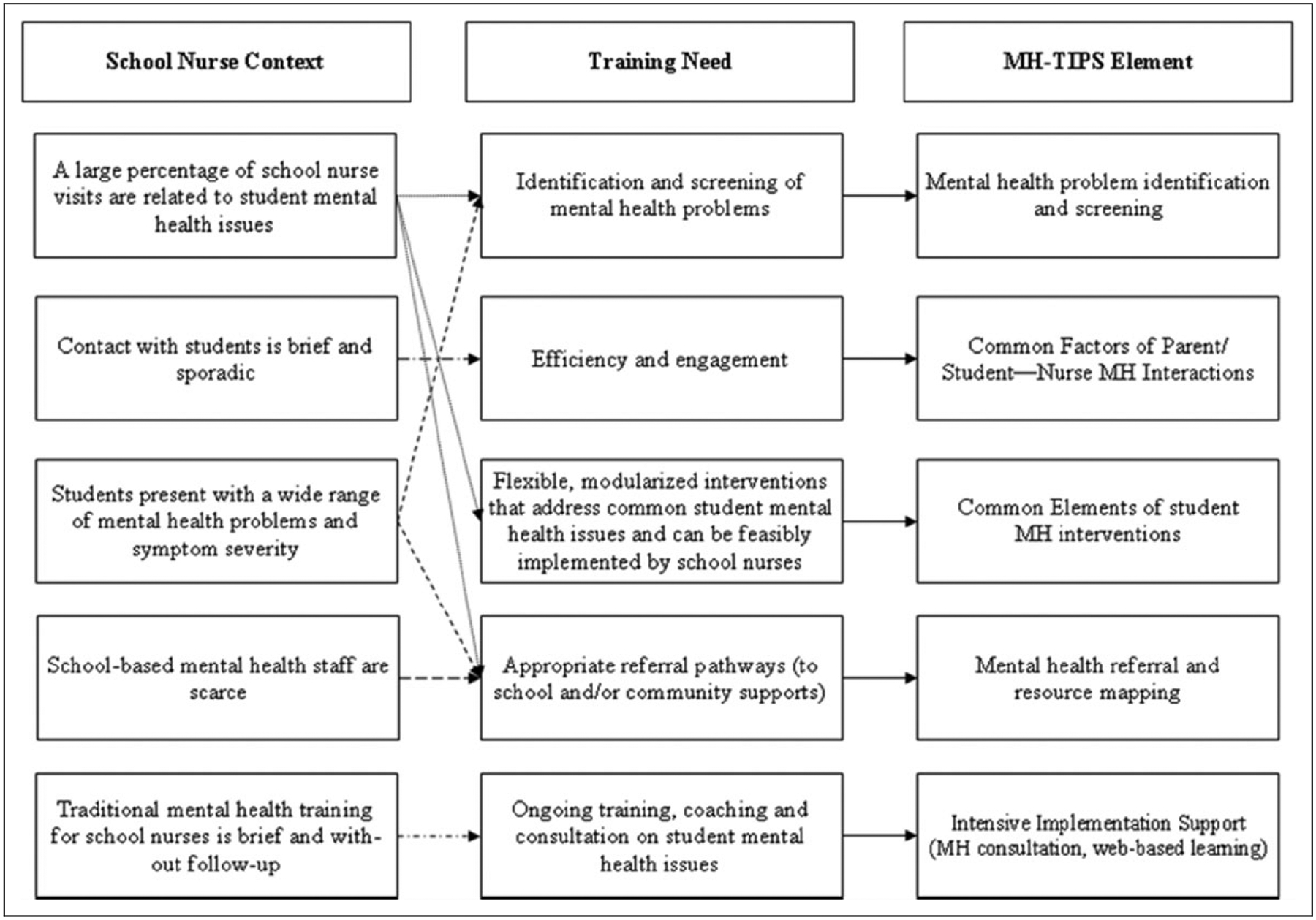

A Priori Models of MH-TIPS

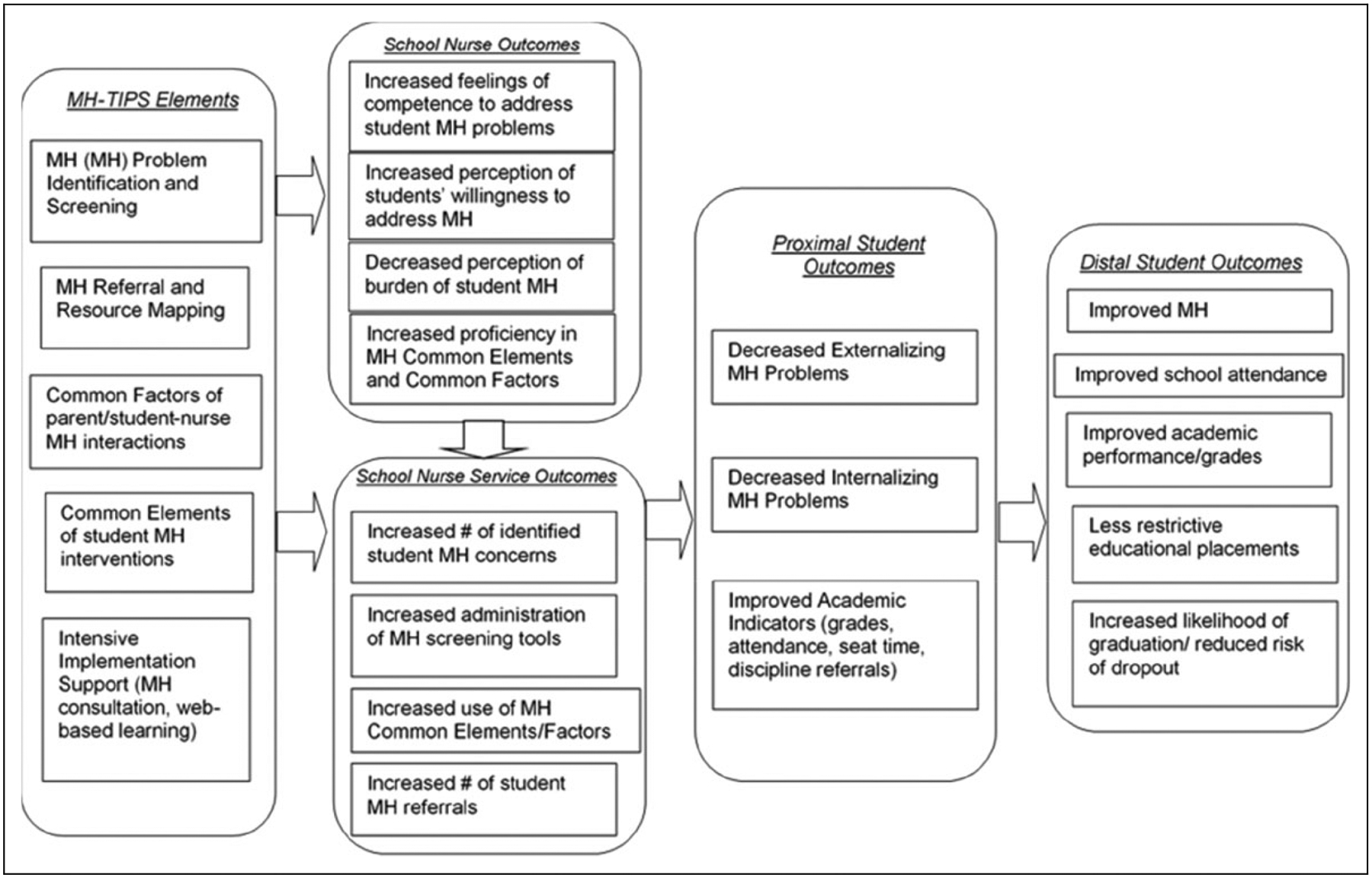

The MH-TIPS was developed based on two a priori conceptual models, the MH-TIPS logic model (Figure 1) and the MH-TIPS theory of change (Figure 2). The MH-TIPS logic model describes the school nurse training context considerations, relevant training needs and considerations, and how specific MH-TIPS elements address these needs. The MH-TIPS includes four core student mental health content elements developed specifically to align with the context of school nursing: (1) mental health problem identification and screening; (2) mental health resources and referral mapping; (3) common factors of successful mental health communication and interaction skills; and (4) common elements of evidence-based mental health interventions. Each of the training components is theoretically linked to improvement in the provision of quality mental health care to students with or at risk for mental health problems. These training elements specifically include skills that are tailored for school nurse practice considerations including range of age and presenting problems, time available for assessment and intervention, and coordination with existing mental health resources and supports in the school and community. Details about each of the proposed training elements included in the MH-TIPS are listed below.

Figure 1.

Mental Health Training Intervention for Health Providers in Schools logic model.

Figure 2.

Mental Health Training Intervention for Health Providers in Schools theory of change.

Mental health problem identification and screening includes training components to help school nurses: (1) identify and differentiate mental health and somatic concerns commonly seen in students at school, (2) learn how to assess for mental health concerns, (3) identify mental health “red flags” to look out for in the context of primary care, and (4) receive training in using evidence-based assessment tools to screen for general mental health concerns, depression, anxiety, attention and hyperactivity concerns, and substance abuse.

Mental health resources and referral mapping includes training components to help school nurses understand best practices for connecting students with appropriate mental health resources including (1) strategies to identify mental health resources in school and in the community, (2) important considerations for referral planning, (3) strategies to support a student’s successful transition to mental health supports, and (4) strategies to foster and maintain successful relationships with mental health providers both in and outside of the school building.

Common factors of successful mental health communication and interaction skills are basic communication and interaction skills that help to foster positive therapeutic interactions. A common factors approach to mental health treatment (Bickman, 2005; Castonguay & Beutler, 2006; Grencavage & Norcross, 1990) argues that aspects of service delivery that are not specific to treatment techniques (e.g., therapeutic alliance) may be applied effectively across broad categories of presenting issues. This approach is in contrast to a “specific effects” method, which requires a diagnostic and treatment process highly specific to distinct illness categories. A common factors approach focuses on the process of care, including patient and provider characteristics and interactions, as well as skills used by providers to influence behavior change (Castonguay & Beutler, 2006; Karver, Handeslman, Fields, & Bickman, 2006). A common factors approach is especially suited for and increasingly has been used by primary care health-care providers given its applicability for a wide range of presenting problems for youth and adults (Wissow et al., 2008). The MH-TIPS common factors of successful mental health communication and interaction skills includes seven modules to teach core strategies for establishing rapport and encouraging behavior change. These skills were specifically adapted for school nurses and include the following modules: (1) introduction to common factors, (2) eliciting mental health concerns, (3) giving advice, (4) time management, (5) addressing barriers, (6) promoting effective group conversation, and (7) managing anger, frustration, and hopelessness.

Common elements of evidence-based mental health interventions is a related approach to common factors that involves the identification of specific practice elements that are found across multiple effective children’s mental health treatments. The Evidence-Based Services Committee of the Hawaii Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division conducted a comprehensive analysis of the children’s mental health literature, to identify “practice elements” that appear in manualized treatment protocols shown to be effective in randomized controlled trials as compared for broad problem areas (e.g., “depression or withdrawn behavior problems”). This “common elements” framework has since been put to extensive use and testing by Chorpita and colleagues who have developed a comprehensive system for training clinicians in the modularized implementation of discrete skills (e.g., relaxation, exposure; Weisz et al., 2012).

The MH-TIPS includes aspects of both common factors and common elements to address the broad areas of mental health need to be most applicable for school nurse practice including common elements which represent intervention practices specifically to address psychoeducation and brief intervention for disruptive behavior, attention and hyperactivity problems, depression, anxiety, and trauma. Aspects of both common factors and common elements were then adapted specifically for delivery by school nurses (e.g., taking into consideration variability of mental health knowledge and time available for intervention).

MH-TIPS Training Structure

Given the research highlighting the limitations of brief, onetime trainings and the need for ongoing implementation support, the proposed MH-TIPS logic model includes intensive implementation support with both mental health consultation and web-based learning components. To achieve this goal, the MH-TIPS training format involves an initial 1-day, in-person training, followed by three bimonthly, 1-day “booster” in-person training sessions focused on skill review, behavioral rehearsal, coaching, and performance feedback. Additional ongoing MH-TIPS implementation support includes bimonthly consultation with a licensed mental health professional and participation in a web-based training support system, including online skill review, video vignettes, and a community learning forum.

The second a priori model that was evaluated in this study is the MH-TIPS theory of change (Figure 2) which, in addition to proposing training content and structure, proposes resulting school nurse service outcomes, proximal and distal student outcomes, and potential mechanisms for change. The MH-TIPS theory of change proposes that the MH-TIPS training components and implementation support will result in increased school nurse competence to address student mental health concerns resulting in increased identification of student mental health concerns and use of mental health supports and interventions by school nurses. These increased mental health supports and interventions will then have a positive impact on student mental health and academic outcomes.

Method

This study used a concurrent mixed-method approach with a triangulation model to facilitate a multilevel stakeholder-driven process to refine the MH-TIPS (Palinkas et al., 2011). To accomplish this approach, the following methodology was utilized (1) key informant interviews with school nurse experts, (2) a focus group using the nominal group decision-making process with practicing school nurses, and (3) a quantitative survey completed by both school nurse experts and practicing school nurses. The methods for each of these components are detailed below. Study procedures were approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent.

Participants

Key informant interview participants.

Six school nurse experts with expertise in training methods used for school nurses, training curriculum development, and/or mental health training for school nurses were nominated by the NASN leadership. Nominated participants were recruited via e-mail invitation to participate. Participants each had greater than 10 years of school nursing experience and held a range of national and state school nurse leadership positions. Participants resided in five different states (Maryland, Michigan, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and California).

Focus group participants.

Practicing school nurses (n = 20) were recruited to participate at the NASN Annual Conference via fliers distributed during a general session. All participants were female, 83% were Caucasian, and participants were practicing school nurses in a range of school settings, including urban, suburban, and rural locales and serving students in preschool through high school (see Table 1 for complete participant demographic information).

Table 1.

Focus Group Participant Characteristics as a Percentage of the Sample.

| Characteristics | % |

|---|---|

| Urbancity | |

| Urban | 23 |

| Suburban | 29 |

| Large town | 23 |

| Rural | 17 |

| Statewide | 5 |

| % FARL students | |

| <5 | 12 |

| 6–10 | 6 |

| 11–25 | 18 |

| 25–50 | 12 |

| >50 | 53 |

| School level serveda | |

| Preschool | 47 |

| Elementary | 59 |

| Middle | 59 |

| High | 30 |

| Students served | |

| <300 | 0 |

| 301–500 | 31 |

| 501–1,000 | 31 |

| >1,000 | 38 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 83 |

| African American | 17 |

| Hispanic | 5 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 100 |

Note. FARL = free and reduced lunch.

These categories are not mutually exclusive.

MH-TIPS quantitative survey participants.

Key informant interview and focus group participants also completed the MH-TIPS quantitative survey.

Procedures and Instrumentation

Key informant interview procedures and instrumentation.

Key informant interviews were 45–60 min in length and conducted via telephone by one or two study investigators. Prior to the phone interview, participants completed informed consent via phone and then reviewed an MH-TIPS summary document detailing the intervention background, logic model, theory of change, and proposed training content and structure. A semi-structured interview protocol was developed by members of the research team and piloted with leadership from the NASN for revisions prior to use, resulting in nine questions. Participants were queried about the most pressing mental health training needs for school nurses; the challenges to mental health training for school nurses; and changes, refinements, and additions to the MH-TIPS logic model and theory of change, and also gave open-ended feedback. The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and cleaned for accuracy by research team members.

Focus group procedures and instrumentation.

Focus group participants convened for 2 hr at a NASN Annual Conference. Participants completed in-person informed consent. During the first hour, participants reviewed a written MH-TIPS summary document and attended an in-person MH-TIPS overview presentation detailing the intervention background, logic model, theory of change, and proposed training content and structure. After reviewing the summary document and hearing the informational presentation, participants were randomly assigned to two equal groups. Each group answered three questions (see Table 2) using the nominal group decision-making process (Delbecq & Van de Ven, 1971).

Table 2.

Focus Group Questions.

| Group | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | What would you add, edit, or remove from the MH-TIPS logic model? |

| What would you add, edit, or remove from the MH-TIPS theory of change? | |

| What are the most pressing training and resource needs related to mental health for school nurses? | |

| 2 | What recommendations do you have about the proposed MH-TIPS content? |

| What recommendations do you have about the proposed MH-TIPS training structure? | |

| What are the biggest challenges to professional development and change of mental health practices? |

Note. MH-TIPS = Mental Health Training Intervention for Health Providers in Schools.

Participants answered each question using the five-step nominal group decision-making process as follows: (1) introduction and explanation: moderator presented the question to the group; (2) silent idea generation: participants worked independently to write ideas in brief phrases; (3) sharing ideas: participants shared each idea with the group and the moderator recorded each idea on a board for all group members to see; (4) group discussion: each recorded idea was then discussed by the group to clarify/explain the idea; and (5) voting and ranking: participants voted privately to prioritize top five ideas (i.e., idea of highest importance received 5 points, lowest importance received 1 point). After each question, the moderator collected each participant’s tally sheet, and participant rankings were tallied to create an overall rank order of generated answers to each question.

MH-TIPS quantitative survey procedure and instrumentation.

Both key informant interview and focus group participants completed the MH-TIPS survey after their participation in either the interview or focus group. The MH-TIPS survey evaluates the theoretical context, professional development process, and content of the proposed MH-TIPS training model. The Theoretical Context section queries how true the proposed mental health service delivery challenges are for school nurses on a scale of 1–5 with 1= not true and 5 = very true. The Professional Development section queries both the usefulness and accessibility of the proposed MH-TIPS training components (e.g., initial 1-day in-person training). Participants rated the usefulness of each component on a scale of 1–5 with 1 = not useful and 5 = very useful. Participants rated the accessibility of each component on a scale of 1–5 with 1 = hard to access and 5 = easy to access. The MH-TIPS Content section queries, on a scale of 1–5, the usefulness of each of the MH-TIPS content areas (e.g., mental health problem identification and screening) with 1 = not useful and 5 = very useful.

Data Analysis

Key informant interview data analysis.

Key informant interviews were analyzed using qualitative analysis grounded theory to distill themes. Atlas.ti v.7 software was used for the qualitative analysis. Consistent with Charmaz (2014), initial, focused, and theoretical coding processes were used to reduce and synthesize the data. Two coders engaged in initial coding to develop focus codes, followed by consensus coding (two interviews). The third author coded the remaining four interviews.

Focus group data analysis.

Nominal group response results for each focus group question were tallied to rank order the most highly endorsed answers.

Quantitative survey data analysis.

Descriptive statistics were calculated from the MH-TIPS survey to evaluate individual components of the MH-TIPS theoretical context, content, and process.

Results

Key Informant Interview Results

Qualitative analysis of the six interviews with school nurse experts revealed seven predominant themes. Each theme is discussed below. Table 3 provides illustrative quotations.

Table 3.

Key Informant Interview Results.

| Theme | Top Codes | Illustrative Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Model validation | MH-TIPS aligns with real-world conditions | I was really excited about this! We have been asking for MH…in our professional development so I think the time is right. |

| Positive student outcomes | ||

| Enthusiasm about project | ||

| School nurse MH training needs | General MH training needed | Having a good solid background in MH…can make us stronger participants at the [SST]table.… Our challenge is really kind of breaking that barrier. |

| Joining the interdisciplinary school teams | ||

| Parent engagement | ||

| School nurse role in MH care | Clarifying SN role in MH care | Nurses don’t like to be in that role of identification with nothing to do, and so that’s when the identification goes further…it’s a brief intervention. |

| SN role in MH assessment, identification | ||

| SN sense of MH competence | ||

| School nurse occupational context | Buy-in and motivation for MH training | Nurses are professionally motivated to address the MH thing, but realistically time constrained…. We got to frame this that spending some time learning [MH-TIPS] will help you help those kids more quickly. |

| Student contacts vary (length, frequency) | ||

| SN are isolated, scarcity of MH staff | ||

| Barriers to school nurse MH practice | Lack of time/large caseloads | We have staffing challenges which compromises our ability to really do any type of screening and identification of MH issues, so time and money. |

| Difficulty leaving school/coverage issues | ||

| Resources vary | ||

| MH-TIPS training format/features | Online support | And those one shot training deals…that’s essential, but I think that you have to provide at some point a follow-up. Focus more on the video training, the webinars for nurses because you will quickly address that lack of coverage challenge almost immediately. |

| Ongoing consultation | ||

| Train the trainer | ||

| Triage tool or flowchart for MH concerns | ||

| Promoting uptake | Lead nurses | How do we assist that nurse in feeling competence using the new tool over time…? That resource nurse, somebody checking in who you have identified this month. |

| National, state, and local organizations | ||

| CEUs and MH certifications |

Note. MH-TIPS = Mental Health Training Intervention for Health Providers in Schools; SN = school nurse; SST = Student Support Services; CEUs Continuing Education Credits.

Model validation.

All participants reported that the proposed logic model and training structure were sound and aligned with the real-world conditions of school nursing. Moreover, nurse experts were clear about their perception that the comprehensive training model of MH-TIPS would be a critical contributing factor to school nurses’ role in supporting positive student outcomes. In addition, although participants provided various recommendations for improvements and represented a range of opinions on the role of school nurses in mental health care (discussed in themes to follow), interview data revealed consistent enthusiasm about the prospect of having the MH-TIPS available to school nurses.

School nurse mental health training needs.

Several nurses reported that only in unique nursing programs or clinical experiences would school nurses already have the mental health knowledge and skills offered by the MH-TIPS and that the “timing is right” in the field of school nursing for mental health training opportunities. Participants reported that enhanced professional development in mental health assessment, identification, referral, and brief intervention would enhance their ability to effectively participate on school teams and engage caregivers of students with mental health needs.

School nurse role in mental health care.

Participants varied in their perspectives regarding the school nurses’ role in mental health care, particularly with respect to whether or not intervention should or could be provided within their context. However, participants agreed that based on the frequent presentation of student mental health concerns, skills to identify, and refer are necessary. Several participants reported their own comfort and experience providing brief intervention, particularly for students who return to their office frequently, when other mental health supports at their school are scarce and/or when students face barriers to community-based care.

School nurse occupational context.

Participants reported that school nurses are often working in isolation from other nurses and sometimes with a scarcity of school-based mental health professionals. Student contacts are typically infrequent without follow-up, but sometimes students are seen multiple times for the same, or various presenting concerns and contact can be brief or longer. School nurses are busy and facing a broad spectrum of student needs, so buy-in and motivation from the nurse is critical to their understanding of how MH-TIPS can support them in their complex, fast-paced, and dynamic occupational context.

Barriers to school nurse mental health practice.

Participants endorsed a variety of barriers to mental health practice including limited time, large caseloads, inconsistent resources at their school site(s), and difficulty planning for coverage to attend professional development off site.

MH-TIPS training format/features.

Participants suggested improvements to the format and features of the MH-TIPS including a “train-the-trainer” feature where MH-TIPS trained nurses could provide leadership and supervision for a group of other nurses as well as offering ongoing consultation in a variety of formats to suit individual preferences. Particularly, to address site coverage issues, online supports such as web-based training were recommended. Also, a triage tool or flowchart for mental health concerns was recommended to utilize familiar nursing language and provide a visual diagram that simplifies decision-making options.

Promoting uptake.

Several strategies to promote uptake of MH-TIPS use were recommended, including dissemination of the MH-TIPS through national, state, and local nursing organizations and structures as well as local health departments (which offer more regulation and supervisory support to school nurses than local school administrators or school districts, for instance). Utilizing nurses in leadership roles or with advanced expertise to endorse and promote the MH-TIPS was also suggested, as well as offering continuing education units and/or mental health certificates to trainees upon completion.

Focus Groups Results

The top three ranked responses for each focus group question are listed in Table 4. Participants endorsed the following modifications to the MH-TIPS logic model: (1) include the role of the family as a key school nurse context consideration, (2) add reintegration tools for students after hospitalization or home instruction as a key mental health training need for school nurses, and (3) add a common factor module on how to address confidentiality within the school context and to be able to coordinate with multidisciplinary stakeholders.

Table 4.

Focus Group Results.

| Rank | Most Highly Endorsed Responses |

|---|---|

| What would you add, edit or remove from the MH-TIPS logic model? | |

| 1 | Add to context: Role of family |

| 2 | Add to training: Reintegration tools for students after hospitalization or home instruction |

| 3 | Add to element: Common factors: How to address confidentiality (within school context and with all stakeholders) |

| What would you add, edit, or remove from the MH-TIPS theory of change? | |

| 1 | Student outcomes: Proximal: Add: Increased student coping strategies |

| 2 | School nurse outcomes: Add: Understanding of tools (and interpretation of findings) administered by school MH providers |

| 3 | MH-TIPS elements: Add: Psychotropic medication |

| What are the most pressing training and resource needs related to MH for school nurses? | |

| 1 | Understanding the signs and symptoms of an MH diagnosis |

| 2 | How to communicate with student/parent who is exhibiting MH issues |

| 3 | Free assessment tools |

| What recommendations do you have about the proposed MH-TIPS content? | |

| 1 | Inclusion of assessment/triage flowchart |

| 2 | Inclusion of crisis management tools |

| 3 | Information about possible diseases and disorders that mimic MH disorders |

| What recommendations do you have about the proposed MH-TIPS training structure? | |

| 1 | Precourse web training |

| 2 | In-person first day training |

| 3 | Need MH provider to be a co-presenter for the live training |

| What are the biggest challenges to professional development and change of MH practices? | |

| 1 | School nurse staffing challenges: Impact on time to interact with students—Need fast resources that nurses can use on the go. |

| 2 | Commitment and buy-in to the process |

| 3 | Cost for implementing a training (at all levels) |

Note. MH-TIPS = Mental Health Training Intervention for Health Providers in Schools; MH = mental health.

Participants reviewed the MH-TIPS theory of change and the most highly endorsed modifications were (1) an additional proximal outcome of MH-TIPS training is increased student coping strategies, (2) an additional school nurse outcome of MH-TIPS is the understanding of tools administered by school mental health professionals and how to interpret the results of such tools, and (3) the addition of an MH-TIPS element to provide education and training for school nurses about psychotropic medication.

Participants also reported on the most pressing training and resource needs related to mental health for school nurses and highlighted the following most highly endorsed needs: (1) how to identify the signs and symptoms of a mental health diagnosis, (2) how to effectively communicate with a student or caregiver who is exhibiting a mental health concern, and (3) access to free mental health assessment tools.

Focus group participants also provided feedback about the proposed MH-TIPS content and training structure. The most highly endorsed recommendations about the proposed MH-TIPS content were (1) the inclusion of a mental health assessment and triage flowchart that school nurses can reference to guide their treatment process, (2) the inclusion of mental health crisis management resources, and (3) information about possible somatic health conditions that may present as similar to mental health concerns.

The most highly endorsed recommendations about the proposed MH-TIPS training structure were (1) inclusion of a precourse web training with introductory information about mental health and mental health concerns to help all participants have a baseline level of competency and understanding of mental health, (2) the importance of the having the first training day be conducted as an in-person training, and (3) the importance of having a school nurse and mental health provider colead the first training day.

Finally, participants described the biggest challenges to professional development in general for school nurses and change of mental health practices. The most highly endorsed challenges included (1) the impact of staffing problems that limit the amount of time school nurses have to interact with students and given that, the importance of having resources that can be used in real time, (2) commitment and buy-in to the training process and adaptation of existing mental health practices, and (3) the cost for implementing a training across various levels of dissemination.

Quantitative Survey Results

All quantitative survey results are reported in Table 5. Participants confirmed the school nurse context can be characterized by frequent mental health visits, a wide range of mental health problems and symptom severity, limited mental health referral sources, and limited ongoing professional development on mental health. There was some discrepancy in whether school nurse contact with students is brief and sporadic. Additional context areas that were highlighted as important for consideration in intervention development included barriers to successful collaboration with interdisciplinary school team members and scope of practice implications.

Table 5.

Quantitative Survey Results.

| Survey Questions | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| School nurse context: not true (1) to very true (5) | ||

| A large percentage of school nurse visits are related to student MH issues | 4.37 | 0.77 |

| Contact with students is brief and sporadic | 3.33 | 1.2 |

| Students present with a wide range of MH problems and symptom severity | 4.63 | 0.58 |

| There are limited MH staff in the school setting | 4.25 | 0.94 |

| Traditional MH training for health providers are often brief and without follow-up | 4.57 | 0.73 |

| MH-TIPS content: not useful (1) to very useful (5) | ||

| MH problem identification and screening | 4.88 | 0.34 |

| Common factors of student/parent-provider MH interactions | 4.92 | 0.28 |

| Flexible, modularized interventions for common student MH issues | 4.92 | 0.28 |

| MH referral and resource mapping | 4.62 | 0.71 |

| Usefulness: not useful (1) to very useful (5) | Accessibility: hard to access (1) to easy to access (5) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| MH-TIPS process | ||||

| Initial 1-day in-person training | 4.95 | 0.21 | 3.83 | 1.27 |

| Three booster sessions | 4.55 | 0.80 | 3.52 | 1.27 |

| Bimonthly phone consultation | 4.22 | 1.08 | 3.54 | 1.50 |

| Ongoing web-based learning support | 4.87 | 0.34 | 4.95 | 0.21 |

Note. MH-TIPCS = Mental Health Training Intervention for Health Providers in Schools; MH = mental health.

With regard to the proposed MH-TIPS professional development process, survey results supported all proposed professional development components as very useful but noted that in-person and phone consultation components would be somewhat difficult to access given school nurse job requirements. Results indicated that web-based training is a very accessible form of professional development.

Survey results indicated that all proposed content would be very useful. Additional content areas endorsed as very useful for school nurse mental health professional development included school team collaboration, understanding legal issues, including scope of practice and confidentiality, addressing barriers related to language, culture, and stigma, emergency/crisis management, and teaming.

Discussion

School nurses play a critical role in the health and mental health care of students but frequently report that they would benefit from additional training and resources to address the wide range of student mental health concerns that present in their practice (Bohnenkamp et al., 2015; Ravenna & Clever, 2016; Stephen & Connors, 2013). The goal of this study was to facilitate a multilevel stakeholder-driven process to refine the MH-TIPS, to facilitate implementation and uptake. Key findings that inform the development of MH-TIPS and potential resultant school nurse and student outcomes are discussed. These include school nurse mental health training context and challenges and mental health content and professional development process considerations.

Mental Health Training Context and Challenges

Results from this mixed-method study highlight a number of important unique practice considerations and challenges for school nurse mental health practice. Consistent with the MH-TIPS a priori models, school nurses are frequently confronted with a wide range of mental health problems and symptom severity, making a broadly applicable mental health training program a better fit than one targeting a particular condition. In contrast to the MH-TIPS a priori hypothesis, the duration of contact with individual students related to mental health issues varies from brief and sporadic to in-depth and consistent; thus, nurses need skills that allow them to be both therapeutic “in the moment” and able to formulate approaches to students who they see repeatedly. Qualitative and quantitative findings also affirmed the MH-TIPS a priori hypotheses that school nurses lack ongoing mental health professional development opportunities and that school- and community-based mental health providers and resources are often limited. School nurses often are called on to play a role in stabilizing students’ problems pending the availability of specialized services, and they require support if they are to fulfill this role. This study discovered additional challenges related to school nurse mental health practice including the impact of school nurse staffing issues, variable school nurse commitment to serving a significant role in student mental health treatment, and the cost for implementing ongoing mental health professional development which are consistent with other literature on school nurse mental health practice (Ravenna & Clever, 2016).

Mental Health Content

School nurses indicated that one essential mental health training content area for their practice would include how to screen and assess for mental health problems within the context of somatic health presentations. In addition, they noted that training in mental health safety assessment and crisis response is critical. School nurses also validated that “common factor skills” to enhance their abilities to interact with students, families, educators, and professionals about mental health issues would be useful for their practice (Karver et al., 2006). Evidence-based “common element” mental health intervention skills specifically adapted for school nurse practice were also endorsed as an important training component; this is consistent with initial work with school health providers who use this training component (Stephan, Mulloy, & Brey, 2011).

A particularly salient theme that emerged with regard to the need for referral and resource-mapping training was the need for skills to better connect with school teams and promote collaboration across school professionals. The importance of communication among collaborating professionals has also been noted in integrated care programs in other settings (Benzer et al., 2012).

Results from this study also supported the inclusion of several content areas that were not included in the initial MH-TIPS design, including training in child and adolescent psychotropic medication, defining nurses’ scope of practice with regard to mental health issues, and training in privacy and confidentiality within school context and with all stakeholders. In addition to these specific mental health content areas, school nurses highlighted the importance of tools and triage materials that are quick and easy to use and consider the school nurse’s fast-paced and varied practice in the school setting. School nurses described the usefulness of assessment flowcharts and “hands-on” materials that could be used directly with students.

Professional Development Process

In addition to addressing needs specific to mental health professional development, this study provides generalizable information about feasible and useful professional development processes for school nurses to receive training on any condition. Results from this study were consistent with the professional development literature, highlighting the importance of ongoing professional development as opposed to onetime trainings (Beidas et al., 2012). School nurses endorsed a number of important professional development components including a balance of in-person and online opportunities, specific timing considerations for ongoing consultation (prescribed meetings vs. a consultation line), and ways to disseminate professional development opportunities. Dissemination strategies focused on the importance of linking professional development opportunities to existing professional organization meetings and using a “train-the-trainer” approach to increase reach.

School Nurse and Student Outcomes

The a priori MH-TIPS theory of change identified both proximal school nurse outcomes and proximal and distal student mental health outcomes that would likely result from participation in the MH-TIPS. School nurse mental health attitudes, preparedness, and service outcomes were validated as potential outcomes of the proposed MH-TIPS. Additionally, school nurse experts and practicing school nurses were enthusiastic about the potential this intervention has for proximal and distal educational and mental health student outcomes. The overwhelming consensus from this evaluation was the need for mental health training for school nurses and the great potential to impact student educational and mental health outcomes.

Limitations

The results of this study represent findings from identified school nurse experts and a national convenience sample of practicing school nurses attending a NASN Annual Conference. While both school nurse experts and focus group participants represented a diverse group of school nurses, it is possible that these findings may not generalize to all school nurses. In addition, purposive sampling was not used for key informant interviews, but data revealed a variety of perspectives presented. Moreover, some indicators of saturation were present related to repeating information among interviews, as well as consistencies in interview and focus group data, particularly for concepts of training features and barriers to mental health practice. Finally, demographic and other descriptive characteristics of the participants are minimal and could be expanded upon in future studies. The purpose of this study was exploratory and to inform MH-TIPS program development. Future research evaluating MH-TIPS feasibility, acceptability, and school nurse and student outcomes after participation in the MH-TIPS is necessary.

Conclusion

This study indicates that, with modifications endorsed as part of this study, the MH-TIPS has the potential to be feasible and useful for school nurses and to impact school nurse practice and student mental health and educational outcomes. Findings from this study are also consistent with previous research that school nurses both need and are interested in in-service mental health professional development (Bohnenkamp et al., 2015; Ravenna & Clever, 2016; Stephan & Connors, 2013). Key findings with regard to essential mental health training content include assessment, intervention, referral, psychotropic medication, and scope of practice considerations. Important professional development components for school nurses for any content area include a combination of both in-person training and ongoing online resources, and quick and user-friendly tools that are tailored to their fast-paced and multifaceted practice context. Findings from this study have been used to inform the development of the MH-TIPS and current efforts are underway testing the effectiveness of this intervention with school nurses and other school health providers. The revised MH-TIPS is currently available online free of charge and with school nurse continuing education credits (https://mdbehavioralhealth.com/training). The results of this study also provide general information about important professional development considerations for school nurses, especially with regard to mental health.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Center for School Mental Health, Project U45 MC 00174 from the Office of Adolescent Health, Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Service Administration, Department of Health and Human Services and Center for Mental Health Services in Pediatric Primary Care funded by the National Institute of Mental Health P20MH086048-05.

Author Biographies

Jill Haak Bohnenkamp, PhD, is an assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Sharon A. Hoover, PhD, is an associate professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Elizabeth Halsted Connors, PhD, is an assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Lawrence Wissow, MD, MPH, is a professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Nichole Bobo, MSN, RN, is the director of nursing education at National Association of School Nurses, Silver Spring, MD, USA.

Donna Mazyck, MS, RN, NCSN, CAE, is the executive director at National Association of School Nurses, Silver Spring, MD, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Allison V, Nativio D, Mitchell A, Ren D, & Yuhasz J (2014). Identifying symptoms of depression and anxiety in students in the school setting. The Journal of School Nursing, 30, 165–172. doi: 10.1177/1059840513500076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, & Kendall PC (2012). Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 63, 660–665. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzer JK, Beehler S, Miller C, Burgess JF, Sullivan JL, Mohr DC, … Cramer IE (2012). Grounded theory of barriers and facilitators to mandated implementation of mental health care in the primary care setting. Depression Research and Treatment, 2012, 1–11. doi: 10.1155/2012/597157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L (2005). A common factors approach to improving mental health services. Mental Health Services Research, 2007, 1–4. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-1961-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnenkamp JH, Bobo N, & Stephan SH (2015). Supporting student mental health: The role of the school nurse in coordinated school mental health care. Psychology in the Schools, 52, 714–727. doi: 10.1002/pits.21851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castonguay LG, & Beutler J (2006). Principles of therapeutic change: A task force on participants, relationships, and techniques factors. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 631–638. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Connors E, Stephan S, Lever N, Ereshefsky S, Mosby A, & Bohnenkamp J (2016). A national initiative to advance school mental health performance measurement in the United States. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 9, 50–69. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2015.1123639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan KC, Vaillancourt K, Rossen E, & Pollitt K (2013). A framework for safe and successful schools. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. [Google Scholar]

- Delbecq AL, & Van de Ven AH (1971). A group process model for problem identification and program planning. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 7, 466–492. doi: 10.1177/002188637100700404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grencavage LM, & Norcross JC (1990). Where are the commonalities among the therapeutic common factors? Professional Psychology Research and Practice, 21, 372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, & Davis AC (2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karver MS, Handelsman JB, Fields S, & Bickman L (2006). Meta-analysis of therapeutic relationship variables in youth and family therapy: The evidence for different relationship variables in the child and adolescent treatment outcome literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of School Nurses. (2017). The school nurse’s role in the behavioral health of students (Position Statement). Silver Spring, MD:Author; Retrieved from https://www.nasn.org/nasn/advocacy/professional-practice-documents/position-statements/ps-behavioral-health [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurl-burt M, & Landsverk J (2011). Mixed method designs in implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38, 44–53. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenna J, & Clever K (2016). School nurses’ experiences of managing young people with mental health problems. The Journal of School Nursing, 32, 58–70. doi: 10.1177/1059840515620281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan SH, Mulloy M, & Brey L (2011). Improving collaborative mental health care by school-based primary care and mental health providers. School Mental Health, 3, 70–80. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9047-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan SH, & Connors EH (2013). School nurses’ perceived prevalence and competence to address student mental health problems. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 6, 174–188. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2013.808889 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J, Chorpita B, Palinkas L, Schoenwald S, Miranda J, & Bearman S, … Research Network on Youth Mental Health. (2012). Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 274–282. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissow L, Anthony B, Brown J, DosReis S, Gadomski A, Ginsburg G, & Riddle M (2008). A common factors approach to improving the mental health capacity of pediatric primary care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 35, 305–318. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0178-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]