Abstract

Double-bond photoisomerization in molecules such as the green fluorescent protein (GFP) chromophore can occur either via a volume-demanding one-bond-flip pathway or via a volume-conserving hula-twist pathway. Understanding the factors that determine the pathway of photoisomerization would inform the rational design of photoswitchable GFPs as improved tools for super-resolution microscopy. In this communication, we reveal the photoisomerization pathway of a photoswitchable GFP, rsEGFP2, by solving crystal structures of cis and trans rsEGFP2 containing a monochlorinated chromophore. The position of the chlorine substituent in the trans state breaks the symmetry of the phenolate ring of the chromophore and allows us to distinguish the two pathways. Surprisingly, we find that the pathway depends on the arrangement of protein monomers within the crystal lattice: in a looser packing, the one-bond-flip occurs, whereas, in a tighter packing (7% smaller unit cell size), the hula-twist occurs.

Light-driven chemistry often involves the cis–trans photoisomerization of a double bond. Photoisomerization plays a central role in photoreceptive biological functions such as vision and phototaxis, as well as in broad areas of chemical and industrial importance including optogenetics, optical data storage, molecular switches, and molecular motors.1–5 In conjugated systems such as the green fluorescent protein (GFP) chromophore, double-bond isomerization can proceed either via a one-bond-flip (OBF) or a hula-twist (HT) pathway, depending on which chemical bonds rotate during the process (Figure 1).6 Since the OBF atomic movement sweeps out a greater volume, the OBF pathway tends to occur in fluid solution where the surroundings allow for free movement, whereas the volume-conserving HT pathway is favored in sterically constrained environments such as vitrified solvents.7 Currently, it is not definitively known whether the protein environment surrounding the GFP chromophore favors isomerization via the OBF or HT pathway.6,8–11

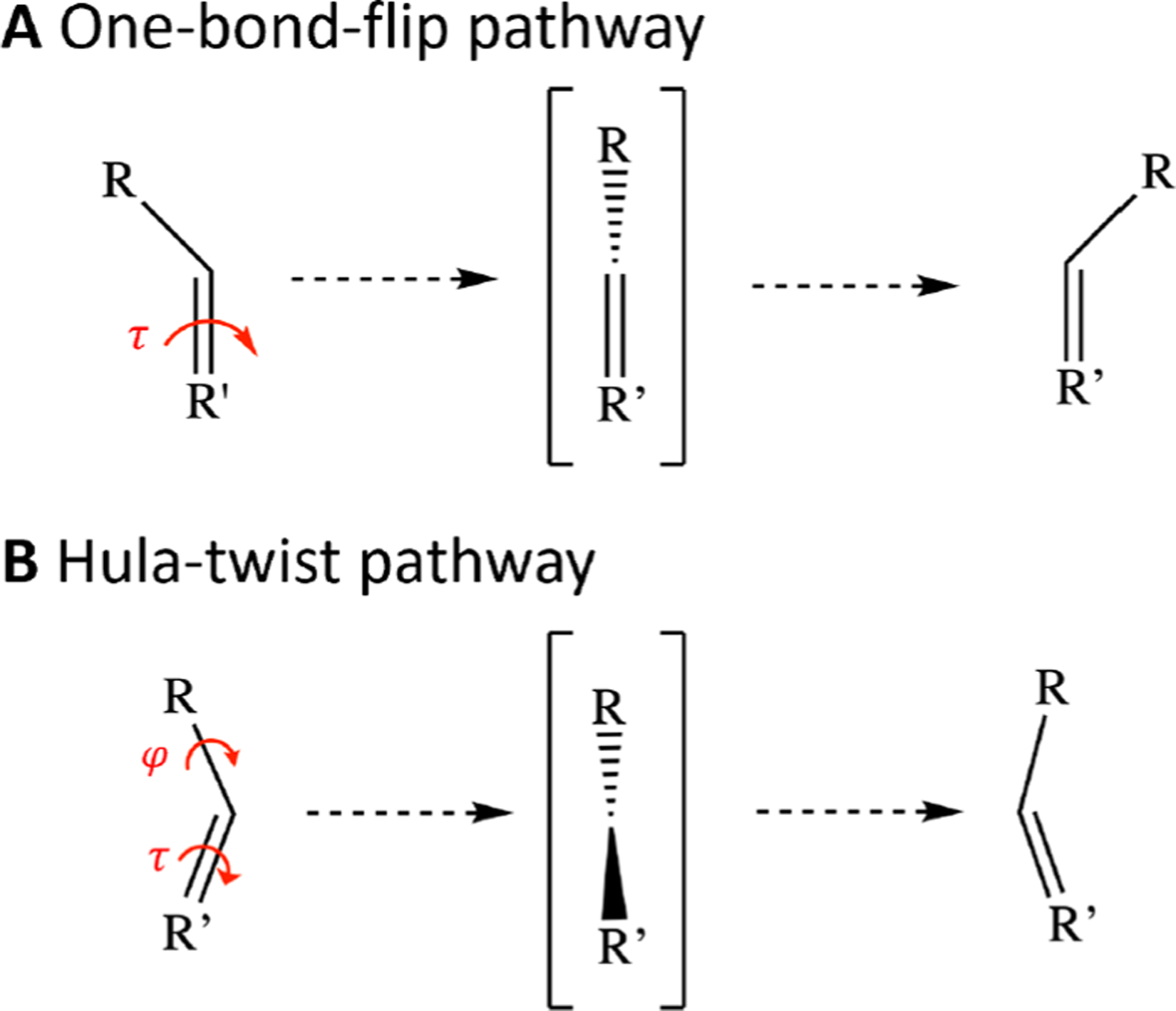

Figure 1.

Pathways of isomerization. In systems such as the GFP chromophore, double-bond isomerization can proceed either (A) via a one-bond-flip (OBF) pathway, in which only the isomerizing τ-bond rotates, or (B) via a hula-twist (HT) pathway, in which the neighboring φ-bond rotates along with the τ-bond.7 The atomic trajectory of the OBF pathway demands a greater volume than the HT pathway.

To address this question, we adopt the model system of rsEGFP2 (reversibly switchable enhanced green fluorescent protein 2), a photoswitchable fluorescent protein which is readily crystallizable12 and has a well-characterized photocycle.13,14 The chromophore within the rsEGFP2 β-barrel naturally adopts the cis isomer and readily photoisomerizes to the less fluorescent trans isomer upon 488 nm light irradiation; the trans isomer, in turn, photoisomerizes back to the cis isomer upon 405 nm light irradiation (Figure 2A).13 The higher-energy trans isomer is relatively stable at room temperature and thermally relaxes to the cis isomer with a rate constant of 0.2 h−1.12 Since rsEGFP2 fluorescence can easily be toggled by laser excitation, its photoswitching property is often exploited for cellular imaging techniques such as super-resolution microscopy.15 Understanding the pathway of the photochemistry would help inform the rational design of fluorescent proteins as imaging tools.

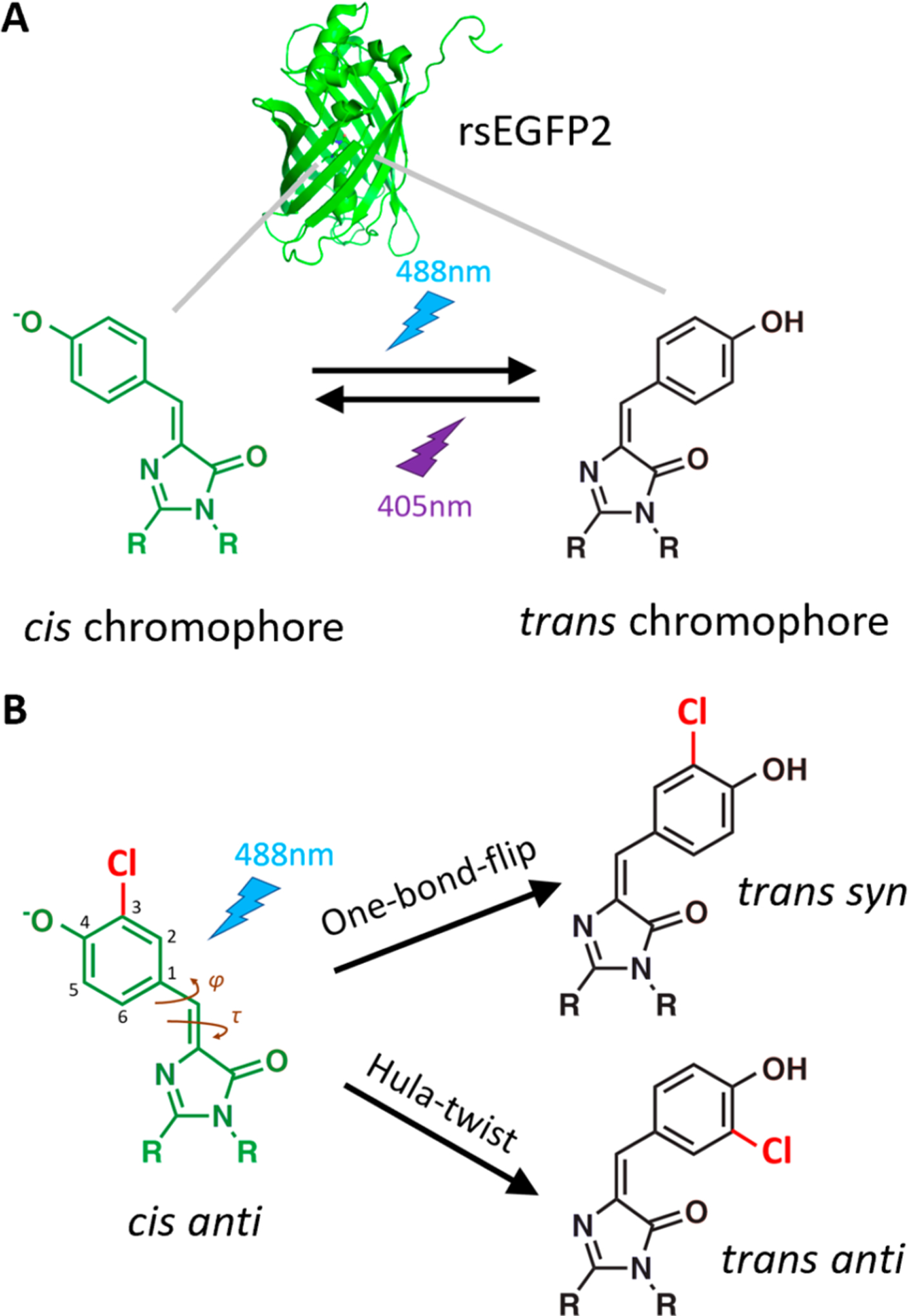

Figure 2.

Reaction scheme for chromophore isomerization. (A) The rsEGFP2 protein (PDB ID: 5DTX12) contains a chromophore whose bridging double bond can be reversibly photoisomerized between cis and trans conformations (cis-to-trans by 488 nm irradiation, trans-to-cis by 405 nm irradiation).12 (B) The 3-chloro substituent introduced by amber suppression breaks the symmetry of the phenolate ring such that each proposed pathway of chromophore cis–trans isomerization (OBF or HT) yields a distinct product. Starting from the cis anti conformation, the OBF pathway forms the trans syn product, whereas the HT pathway forms trans anti.

An additional advantage of rsEGFP2 is that substituents can be readily incorporated into the chromophore to distinguish the OBF and HT pathways. In the wild-type chromophore, both pathways yield the same trans product, but if a substituent breaks the symmetry of the chromophore’s phenolate ring, then the two pathways yield distinct products. Specifically, as shown in Figure 2B, when the cis chromophore with a substituent anti to the double-bonded imidazolinone nitrogen undergoes OBF isomerization, the resulting product is trans syn, whereas if the initial cis anti state undergoes HT isomerization, then the product is trans anti. Thus, placing a substituent on the chromophore allows us to deduce the photoswitching pathway from crystal structures of the cis and trans forms of rsEGFP2, a distinction not achievable by spectroscopic methods.

In this study, we investigated the cis-to-trans photoisomerization pathway of an rsEGFP2 variant with a substituted phenolate ring by solving crystal structures before and after 488 nm light irradiation. Remarkably, we found that the pathway depends on how the rsEGFP2 monomers pack into a crystal lattice. Our structures demonstrate that chromophore dynamics are sensitive to their surroundings, and more broadly suggest that a protein’s internal structure can be influenced by crystallization conditions.

rsEGFP2 was expressed with a monochlorinated chromophore using amber suppression.16 Upon replacing the tyrosine at residue 67 with the noncanonical amino acid 3-chlorotyrosine, the autocatalytic chromophore formation reaction produces a chromophore with a chlorine substituent ortho to the phenolic oxygen (Figure 2B). The resulting protein variant with this substitution, denoted Cl-rsEGFP2, maintained similar photoswitching properties as the wild-type rsEGFP2 (Figure S1) and formed crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction. To capture the photoisomerized trans state, the Cl-rsEGFP2 crystals were looped and irradiated with 488 nm light at room temperature, and then immediately cryocooled (see Section S1 for detailed methods). We collected X-ray diffraction data sets of cryocooled Cl-rsEGFP2 crystals before and after irradiation and found that the crystals had lattice constants similar to the previously reported12 wild-type structures (Figures S2 and S3). The electron density of the nonirradiated crystals was well modeled by a chromophore in the cis state; the irradiated crystals required a mixture of cis and trans structural models to explain the electron density. Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table S2, and the minor conformations of the irradiated crystals, such as the residual cis population from incomplete isomerization, are discussed in Section S2.

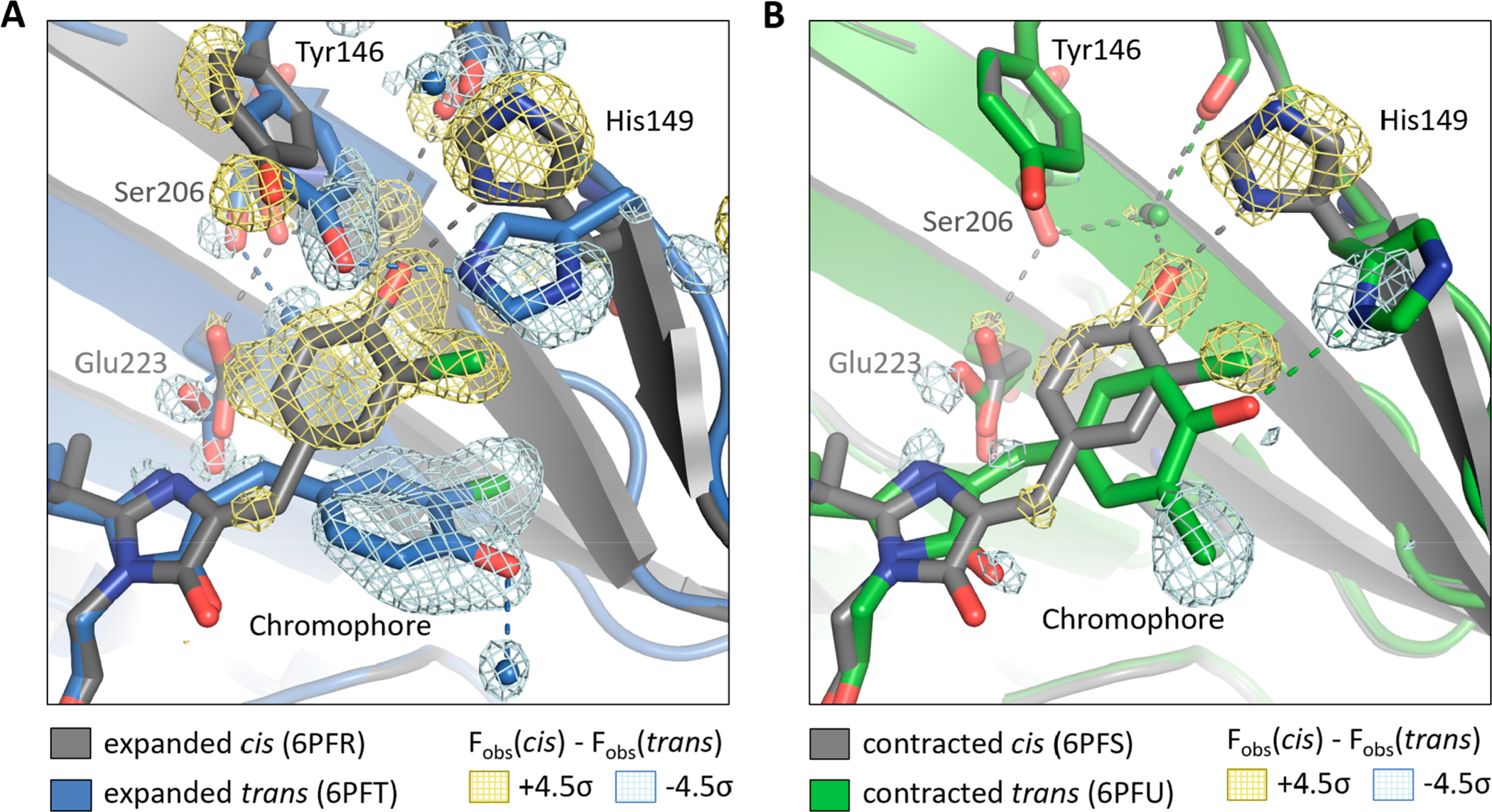

As expressed with the chromophore in the cis state, the chlorine substituent is incorporated completely in the anti orientation (Figure 3A). Our observation of a single substituent orientation is consistent with previous protein crystal structures containing chlorinated tyrosines.17 When the chromophore is photoisomerized to the trans state, the chlorine substituent ends up in the syn orientation, and the two rings of the chromophore are no longer planar with respect to one another (τ = 12°, φ = −13° in cis; τ = 187°, φ = −32° in trans, where τ is the N−C=C–C1 dihedral angle and φ is the C=C–C1–C6 dihedral angle (Figure 2B)). In addition, the surrounding pocket distorts slightly to accommodate the new trans geometry: the phenolic oxygen loses its hydrogen bond to His149 and instead forms a hydrogen bond with a new water molecule in the trans structure; in turn, the Tyr146 residue adopts a different rotamer and acts as a surrogate hydrogen-bonding partner to His149 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Crystal structures of Cl-rsEGFP2. Structural models of cis and trans Cl-rsEGFP2 in the (A) expanded crystal and (B) contracted crystal. The cis states are shown with gray carbon atoms, and trans states are shown with colored carbon atoms (blue and green for expanded and contracted crystals, respectively). Water molecules are shown as spheres, and hydrogen bonds (≤3.1 Å) are shown as dotted lines. The Fobs(cis) – Fobs(trans) difference density map contoured at ±4.5σ is shown (yellow, positive; light blue, negative) to highlight significant differences between the cis and trans state. PDB IDs are shown in the figure legend, and data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table S2.

While collecting data on several Cl-rsEGFP2 crystals, we observed that some crystals had a unit cell size smaller than that of previously reported crystals and the ones discussed above by up to 7% (Table S2). It is well-known that protein crystals can expand or contract when water enters or exits the solvent channels between individual proteins,18 and in our case, slight variations in experimental handling caused the solvent content of Cl-rsEGFP2 to vary. These variations included the incubation time in cryoprotectant and the exposure time of cryoprotectant to ambient air during the looping and irradiation process. Upon further investigation, we discovered that we could controllably diminish the lattice spacing of Cl-rsEGFP2 crystals by soaking them in a cryoprotectant of low relative humidity (see methods in Section S1), which pulled water out of the crystal and forced the proteins to pack more closely together. The resulting “contracted” crystal consistently had a smaller unit cell volume (19 900 Å3 vs 21 400 Å3) and a lower solvent content (29% vs 34%) than the “expanded” crystal (Table S2).

When the Cl-rsEGFP2 unit cell contracts into the tighter lattice, the protein retains its β-barrel fold but develops slight deviations in tail and loop regions compared with the more expanded lattice (Figure S4). The interior of the protein around the cis state of the chromophore maintains the same geometry as in the expanded lattice, but the chromophore pocket is significantly distorted around the trans state of the chromophore when the lattice contracts (Figure 3B). Interestingly, the trans structure in the contracted lattice has the chlorine substituent in an anti orientation, in contrast to the expanded lattice. Furthermore, the two rings of the chromophore are planar (τ = 153°, φ = −43°), and the phenolic oxygen retains its hydrogen bond with His149. These differences between the structures of the trans chromophore and its environment between the contracted and expanded lattices (Figure S5) were reproducibly observed in multiple crystals.

The crystal structures of Cl-rsEGFP2 indicate that a subtle rearrangement of the crystal lattice is sufficient to alter the photoisomerization pathway. As illustrated in Figure 3A and 3B, photoisomerization occurs via the OBF pathway (cis anti → trans syn) in the expanded crystal and via the HT pathway (cis anti → trans anti) in the contracted crystal. Since cis–trans isomerization is sensitive to the steric properties of the surrounding medium, it is reasonable that the arrangement of rsEGFP2 monomers within the crystal lattice affects the photoisomerization pathway. We speculate that the tighter packing and lower solvent content of the contracted crystal create a more rigid chromophore pocket that restricts atomic motion during isomerization, favoring the volume-conserving HT trajectory.

Our structures demonstrate that the dynamics of the chromophore pocket inside Cl-rsEGFP2 are affected by changes in the external environment around the protein. This result is consistent with a recent study by Kao et al. on the reversibly photoswitchable fluorescent protein Dronpa,19 in which the authors observe that increasing the viscosity of the surrounding medium slows down the photoswitching rate. The fact that both solvent viscosity and crystal packing affect chromophore isomerization suggests that photoisomerization of the internal chromophore is coupled to motion of the protein β-barrel.

The Cl-rsEGFP2 structures also present a striking example of how crystallization conditions may perturb the structure of buried portions of proteins, and, in this case, with functional consequences. It is well-accepted that the outward-facing residues and flexible loops of proteins are distorted by interactions between proteins in a crystal,20,21 but it is less common for the interior of the protein matrix to be affected by packing interactions. Nevertheless, the crystal structures of trans Cl-rsEGFP2 exhibit a significant distortion of the internal chromophore pocket upon 7% unit cell contraction (Figure 3, Figure S5), indicating that crystal packing interactions affect the conformation of internal residues in Cl-rsEGFP2.

It is important to note that the Cl-rsEGFP2 structures reported here only provide snapshots before and after photoisomerization rather than a time-resolved depiction of the process. The mechanistic conclusions drawn in this paper rely on the assumption that the trans crystal structures reflect the chlorine orientation immediately following photoisomerization, which presumes that the trans syn and trans anti states do not interconvert on the experimental time scale (that is, in the few seconds between photoisomerization and cryocooling). The interconversion between syn and anti conformers (a phenolate ring-flip) requires rotation about the φ-bond (Figure 2B), which has substantial double-bond character since it is conjugated to a large π-system. In Section S3, we argue that the energetic barrier is likely too costly for this process to occur freely at room temperature within the relevant time scale. More definitive proof of the photoisomerization mechanism would come from time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography22,23 of rsEGFP2 with a substituted chromophore, which would reveal snapshots of the atomic trajectory immediately following photon absorption. The atomic motion of isomerization occurs within picoseconds of excitation, as shown from pump–probe studies,23 so the time resolution of a serial femtosecond crystallography experiment should be sufficient to capture the isomerization process as it occurs.

In summary, we have observed mechanistic details of cis–trans photoisomerization in crystals of Cl-rsEGFP2. Remarkably, the pathway is not intrinsic to the protein but depends on the packing of the protein within the crystal: an expanded crystal lattice favors the more volume-demanding OBF pathway, while a 7% reduction in unit cell size instead selects for the HT pathway. This finding suggests chromophore isomerization in fluorescent proteins is coupled to motion of the surrounding β-barrel, and that the chromophore’s photoisomerization mechanism may not be conserved across different fluorescent protein variants. Our results also indicate that crystallization conditions can cause structural rearrangements of interior-facing residues in proteins, suggesting that crystal structures should be interpreted with care.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH. Part of this work was performed at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities (SNSF)/Stanford Nanofabrication Facility (SNF), supported by the National Science Foundation under Award ECCS-1542152. We thank Dr. Irimpan Mathews at the SSRL for assistance with data collection, Dr. Jacek Kozuch for conceiving the project idea, and Chi-Yun Lin for many helpful discussions. Support from the Stanford Bio-X Undergraduate Fellowship (to J.C.) and the Center for Molecular Analysis and Design Graduate Fellowship (to M.G.R.) is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported, in part, by NIH Grant GM118044 (to S.G.B.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b08356.

Protein and DNA sequences, detailed experimental methods, discussion of minor populations, discussion of ring-flip time scale, comparison of crystal structures, and crystallographic data and refinement statistics (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Gozem S; Luk HL; Schapiro I; Olivucci M Theory and simulation of the ultrafast double-bond isomerization of biological chromophores. Chem. Rev 2017, 117 (22), 13502–13565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Fenno L; Yizhar O; Deisseroth K The development and application of optogenetics. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 2011, 34, 389–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Gu M; Zhang Q; Lamon S Nanomaterials for optical data storage. Nat. Rev. Mater 2016, 1 (12), 16070. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Russew M-M; Hecht S Photoswitches: From Molecules to Materials. Adv. Mater 2010, 22 (31), 3348–3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).van Leeuwen T; Lubbe AS;Štacko P; Wezenberg SJ; Feringa BL Dynamic control of function by light-driven molecular motors. Nat. Rev. Chem 2017, 1 (12), 0096. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Andresen M; Wahl MC; Stiel AC; Gräter F; Schäfer LV; Trowitzsch S; Weber G; Eggeling C; Grubmüller H; Hell SW; Jakobs S Structure and mechanism of the reversible photoswitch of a fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102 (37), 13070–13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Liu RSH Photoisomerization by hula-twist: A fundamental supramolecular photochemical reaction. Acc. Chem. Res 2001, 34 (7), 555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Gayda S; Nienhaus K; Nienhaus GU Mechanistic insights into reversible photoactivation in proteins of the GFP family. Biophys. J 2012, 103 (12), 2521–2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Schäfer LV; Groenhof G; Boggio-Pasqua M; Robb MA; Grubmüller H Chromophore protonation state controls photoswitching of the fluoroprotein asFP595. PLoS Comput. Biol 2008, 4 (3), No. e1000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jonasson G; Teuler J-M; Vallverdu G; Merola F; Ridard J; Levy B; Demachy I Excited state dynamics of the green fluorescent protein on the nanosecond time scale. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2011, 7 (6), 1990–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Li X; Chung LW; Mizuno H; Miyawaki A; Morokuma K Primary events of photodynamics in reversible photoswitching fluorescent protein Dronpa. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2010, 1 (23), 3328–3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).El Khatib M; Martins A; Bourgeois D; Colletier J-P; Adam V Rational design of ultrastable and reversibly photoswitchable fluorescent proteins for super-resolution imaging of the bacterial periplasm. Sci. Rep 2016, 6 (1), 18459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Grotjohann T; Testa I; Reuss M; Brakemann T; Eggeling C; Hell SW; Jakobs S rsEGFP2 enables fast RESOLFT nanoscopy of living cells. eLife 2012, 1, No. e00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Zhou XX; Lin MZ Photoswitchable fluorescent proteins: ten years of colorful chemistry and exciting applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2013, 17 (4), 682–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Baddeley D; Bewersdorf J Biological insight from super-resolution microscopy: What we can learn from localization-based images. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2018, 87 (1), 965–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Chin JW Expanding and reprogramming the genetic code of cells and animals. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2014, 83 (1), 379–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Oltrogge LM; Boxer SG Short hydrogen bonds and proton delocalization in green fluorescent protein (GFP). ACS Cent. Sci 2015, 1 (3), 148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Atakisi H; Moreau DW; Thorne RE Effects of proteincrystal hydration and temperature on side-chain conformational heterogeneity in monoclinic lysozyme crystals. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Struct. Biol 2018, 74 (4), 264–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kao Y-T; Zhu X; Min W Protein-flexibility mediated coupling between photoswitching kinetics and surrounding viscosity of a photochromic fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109 (9), 3220–3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jacobson MP; Friesner RA; Xiang Z; Honig B On the role of the crystal environment in determining protein side-chain conformations. J. Mol. Biol 2002, 320 (3), 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wagner G; Hyberts SG; Havel TF NMR structure determination in solution: A critique and comparison with X-ray crystallography. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 1992, 21 (1), 167–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Coquelle N; Sliwa M; Woodhouse J; Schirò G; Adam V; Aquila A; Barends TRM; Boutet S; Byrdin M; Carbajo S; De la Mora E; Doak RB; Feliks M; Fieschi F; Foucar L; Guillon V; Hilpert M; Hunter MS; Jakobs S; Koglin JE; Kovacsova G; Lane TJ; Levy B; Liang M; Nass K; Ridard J; Robinson JS; Roome CM; Ruckebusch C; Seaberg M; Thepaut M; Cammarata M; Demachy I; Field M; Shoeman RL; Bourgeois D; Colletier J-P; Schlichting I; Weik M Chromophore twisting in the excited state of a photoswitchable fluorescent protein captured by time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography. Nat. Chem 2018, 10 (1), 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Colletier J-P; Sliwa M; Gallat F-X; Sugahara M; Guillon V; Schirò G; Coquelle N; Woodhouse J; Roux L; Gotthard G; Royant A; Uriarte LM; Ruckebusch C; Joti Y; Byrdin M; Mizohata E; Nango E; Tanaka T; Tono K; Yabashi M; Adam V; Cammarata M; Schlichting I; Bourgeois D; Weik M Serial femtosecond crystallography and ultrafast absorption spectroscopy of the photoswitchable fluorescent protein IrisFP. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2016, 7 (5), 882–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.