Abstract

Background and Objectives:

The study’s goal was to measure the association between social risks and the mental health of school-age children in primary care.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study in an urban safety-net hospital-based pediatric clinic using data collected from two standard screening tools administered at well child care visits for children age 6–11. Psychosocial dysfunction was measured with the Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 (PSC-17) and six social risks (caregiver education, employment, child care, housing, food security, and household heat) were measured with the WE CARE screener. Multivariable linear and logistic regression analyses were conducted to measure the association between scores while controlling for sociodemographic characteristics.

Results:

Among N=943 patients, cumulative social risks were significantly associated with a positive PSC-17 total score (Adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] 1.2; 95% CI [1.1–1.5]; p=0.02), indicating psychosocial dysfunction. Children with ≥3 social risks were 2.4 times more likely to have a positive PSC-17 total score compared to children with <3 social risks (95% CI [1.5–3.9]; p<0.001). Of the individual social risks measured, only food insecurity significantly predicted a positive PSC-17 total score (aOR 1.9; 95% CI [1.1–3.2]; p=0.02) and attention score (aOR 1.9; 95% CI [1.1–3.4]; p=0.03).

Conclusion:

Number of risks on a social risk screener was associated with psychosocial dysfunction in school-age children. Food insecurity was the only individual risk associated with psychosocial dysfunction, in particular attention problems. Screening tools for social risks could be used to identify at-risk children whose mental health may be adversely impacted by their social conditions.

Keywords: pediatrics, primary care, child psychiatry, mental health, social determinants of health

Introduction

Psychiatric disorders are among the most prevalent conditions in childhood, affecting more than one in five children in the United States (U.S.),1,2 and causing significant lifelong morbidity and increased mortality.2–5 Socioeconomically disadvantaged children are at even higher risk of psychiatric conditions than their more advantaged peers.6–8 Children raised in poverty, currently over 20% of children in the U.S.,9 are also less likely to access treatment10 and are more vulnerable to the detrimental consequences of mental health problems, such as academic failure and involvement with the justice system.11–15 The increased risk for mental health problems in socioeconomically disadvantaged children is in part related to adverse living and social conditions - collectively referred to as social determinants of health (SDoH) - including food insecurity, housing instability, and lack of quality child care.8 There is a growing body of literature supporting the contribution of social risk in childhood to physical, developmental, and mental health outcomes. Most prior studies describe the impact of cumulative risk, demonstrating that health outcomes worsen as risks accumulate.8,16,17 Other studies have examined individual risks. For example, homelessness and food insecurity have both been linked to higher rates of psychiatric symptoms.18–20

Given the evidence that social risks have on lifelong health, there is increasing interest in addressing these as part of routine preventive pediatric health care. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) 2016 policy statement on Poverty and Child Health recommended screening for social determinants that can be addressed at pediatric visits.11 Previous work by our study team demonstrated that it is feasible to screen for certain social risks and needs in the context of well child care and increase receipt of community resources for low income families.21 However, while many pediatric primary care practices have begun to adopt such screening,22 it is not known whether these tools could help to identify children at risk of mental health problems due to their social adversity. Screening for social risks could also be a key component of early intervention strategies for children at risk for mental health problems, or a component of multimodal treatments for children with psychiatric symptoms.

Thus, we sought to examine the relationship between six social risks (caregiver education, employment, child care, housing, food security, and household heat) that can be identified and addressed in primary care using a common social risks screener (WE CARE), and mental health problems in school-age children, as reported by caregivers on standardized screening tools administered at well child visits in a large, urban, safety-net hospital-based pediatric practice. We hypothesized that a higher number of social risks on the WE CARE screener would be associated with higher odds of mental health problems. We were also interested in whether: 1) children with social risks also had more mental health problems, and whether this relationship was specific to certain symptom clusters (e.g. anxiety/depression vs. behavioral vs. attention issues); 2) a certain threshold of social risks could distinguish children whose mental health problems might be exacerbated by these risks; and 3) children with certain individual social risks were more likely to suffer from mental health problems. Our goal was to inform how social risks screening tools could be used in clinical practice for children with social risks, mental health needs, or both.

Methods

Research Design and Setting

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of de-identified electronic medical record (EMR) data for children age 6–11 years old seen for well child visits at a large, urban, safety-net hospital-based pediatric clinic between September 1, 2016 and August 31, 2017. We extracted scores on two brief standardized questionnaires that caregivers complete as a part of well child visits for school-age children: 1) the Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 (PSC-17),23,24 which assesses psychosocial functioning; and 2) the Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education (WE CARE) screener,21,25 which measures six social risks. Both screening tools were offered in multiple languages (English, Spanish, Portuguese, Haitian Creole) and given to caregivers at check-in. During the study period, results on both screeners were collected and entered electronically into the EMR by practice medical assistants. We also extracted sociodemographic data from the EMR including patient’s age, gender, race, ethnicity, language, and primary health insurance.

The study was approved by the Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board.

Measures and Variables

Psychiatric Symptoms.

Psychiatric symptoms were measured with the PSC-17, a caregiver-report measure of children’s psychosocial functioning. The PSC-17 is widely used as a psychosocial screening instrument in pediatrics, has been validated in many populations and languages,24,26–28 and has both high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.87) and test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.85).23,24 It was derived via exploratory factor analysis from the original 35-item psychiatric symptoms questionnaire.22 Caregivers rate symptoms on a three-point Likert scale, with 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, and 2 = often. Scores for each item are summed and reported as a total score (all 17 items) and three subscales: internalizing (5 items), externalizing (7 items), and attention (5 items). Higher scores indicate higher levels of impairment, and a positive total score (≥15) indicates psychosocial dysfunction and need for further evaluation.23,26 Children with an elevated externalizing subscale score (≥7), attention subscale score (≥7), or internalizing subscale score (≥5) usually have clinically significant problems with behavior, attention, or anxiety and depression, respectively.23,24

Social Risks.

Social risks were measured by the WE CARE screener, a caregiver-report questionnaire written at a third grade reading level which assesses six basic risks in the following order: caregiver education, employment, child care, housing, food security, and household heat.21,25 The original questionnaire was developed using an interdisciplinary collaborative approach to include only items for which community resources were available. The questionnaire has established face and content validity as well as high 2-week test-retest reliability (r=0.92).25 Previous research has demonstrated that WE CARE is feasible at well child visits with low-income children, and that it can lead to the receipt of more community resources and reduced social risks for families.21,25 Table 1 lists the WE CARE questions and answers, including risk represented by each question and scoring information.

Table 1.

WE CARE Survey Questions and Coding.

| Risk | Survey question (yes/no answers)* | Answer indicating risk present** |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Do you have a high school degree? | No |

| Employment | Do you have a job? | No |

| Child care | Do you risk daycare for your child? | Yes |

| Housing | Do you think you are at risk of becoming homeless? | Yes |

| Food | Do you always have enough food for your family? | No |

| Household heat | Do you have trouble paying your heating bill for the winter? | Yes |

Questions are listed in same order as the survey administered to families.

A score of 1 was assigned to each answer indicating a risk in order to calculate a cumulative risks score.

Data Analysis

We used data only from children who had complete answers to both questionnaires (WE CARE and PSC-17). Cumulative social risks were calculated by assigning a value of “1” to a risk, and “0” to no risk; therefore, items for education, employment, and food were reverse-coded (Table 1). The resulting score (ranging from 0 to 6) indicates the number of current, caregiver-reported social risks. In order to examine the association between PSC-17 scores and cumulative and individual social risks, we performed chi-squared tests and calculated odds ratios. We plotted a Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve for WE CARE score to determine a cut-off that best distinguished children with a positive PSC-17 total score from those with a negative score. We performed multiple linear regression analyses to examine the association between cumulative social risks and PSC-17 scores after adjusting for the following potential confounding variables – age (in years), gender (male vs. female), race/ethnicity (4 categories as listed in Table 2, with Non-Hispanic White as reference), language (English vs. other), and insurance (public vs. other).5 We performed multivariable logistic regression analyses to assess whether one or more social risks predicted positive PSC-17 scores1 after adjusting for the same potential confounders. We performed additional multivariable logistic regression analyses with all six individual social risks as predictors to examine the association between individual risks and PSC-17 scores, adjusting for potential sociodemographic confounders and checking for interactions among the six individual risks. For all statistical analyses, significance was set to α = 0.05. We used Statistical Analytical Systems (SAS) version 9.4 for data management and analysis.29

Table 2.

Sample characteristics.

| N=943 | |

|---|---|

| Age in years: Mean ± SD | 8.5 ± 1.7 |

| Sex: n (%) | |

| Male | 472 (50.1%) |

| Female | 471 (49.9%) |

| Race/Ethnicity: n (%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 154 (16.3%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 486 (51.5%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 47 (4.9%) |

| Non-Hispanic Other/Declined | 256 (27.2%) |

| Language: n (%) | |

| English | 610 (64.7%) |

| Non-Englishǂ | 333 (35.3%) |

| Haitian Creole | 193 (20.5%) |

| Port Creole/Cape Verdean | 42 (4.5%) |

| Spanish | 37(3.9%) |

| Other | 61 (6.5%) |

| Insurance: n (%) | |

| Public | 700 (74.2%) |

| Commercial | 236 (25.0%) |

| Self-pay | 6 (0.6%) |

| Other | 1 (0.1%) |

| Positive PSC-17ǂ ǂ scores: n (%) | |

| Internalizing (≥ 5) | 67 (7.1%) |

| Externalizing (≥7) | 86 (9.1 %) |

| Attention (≥7) | 99 (10.5 %) |

| Total (≥15) | 98 (10.4%) |

| WE CAREǂ ǂ ǂ social risks: n (%) | |

| Parent Education | 217 (23.0%) |

| Employment | 289 (30.7%) |

| Child care | 106 (11.2%) |

| Housing | 50 (5.3%) |

| Food security | 135 (14.3%) |

| Household heat | 228 (24.2%) |

| Number of social risks: n (%) | |

| 0 | 402 (42.6%) |

| 1 | 236 (25.0%) |

| 2 | 175 (18.6%) |

| 3 | 85 (9.0%) |

| 4 | 41 (4.4%) |

| 5 | 4 (0.4%) |

| 6 | 0 (0%) |

Non-English language includes Haitian Creole, Port Creole/Cape Verdean, Spanish, and others.

PSC-17 = Pediatric Symptom Checklist, 17 item version.

WE CARE = Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education.

Results

Sample characteristics

There were 3345 patients age 6–11 years old seen for well child visits during the study time period, and 943 (28.1 %) of these patients had complete results on both questionnaires entered into the EMR. The sample of patients with both completed questionnaires did not differ from the remainder of the sample based on sociodemographic characteristics (see Table 2).

Among the 943 children with complete WE CARE and PSC-17 screeners, 50.1% were male with a mean age of 8.5 years (SD = 1.7) (Table 2). The majority identified as non-Hispanic Black (51.5 %); 16.3% as Hispanic/Latino/Spanish, and 4.9% as non-Hispanic White. English was listed as the family’s primary language in the EMR for most patients (64.7%) followed by Haitian (20.5%), Port Creole/Cape Verdean (4.5%), Spanish (3.9%), and other (6.5%). Most children (74.2%) were publicly insured.

A quarter of the sample had at least one social risk. Table 2 shows the percentage of children with individual and cumulative risks (e.g. one, two, three risks, etc). The most common social risks were employment (30.7%), household heat (24.2%), and caregiver education (i.e., lack of high school diploma or GED) (23.0%).

Approximately 10% of children had a positive PSC-17 total score, indicating psychosocial dysfunction (Table 2). The externalizing and attention subscales identified about 10% of the sample with clinically significant symptoms in that realm, consistent with previously published risk rates.24 The internalizing score identified about 7% of children with clinically significant symptoms, which was less than rates reported in large epidemiologic samples.24

Association between cumulative social risks and psychosocial dysfunction

In the multivariable logistic regression model, cumulative social risks predicted significantly increased odds of a positive PSC-17 total score (Wald X2 = 5.16; adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] 1.2; 95% CI [1.1 – 1.5]; p-value = 0.02) (Table 3), indicating psychosocial dysfunction. Plotting a ROC curve with WE CARE against the PSC-17 total score demonstrated that we could most reliably distinguish children with a positive PSC-17 total score at a cut-off of 3 social risks on WE CARE (Figure 1A). Children with 3 or more social risks had 2.4 times the odds of having a positive PSC-17 total score compared to children with less than 3 risks (X2 = 13.90; 95% CI [1.5–3.9]; p-value <0.001) (Figure 1B). Likewise, in the multivariable logistic regression model, children with 3 or more social risks had 2.4 times the odds of having a positive PSC-17 total score compared to children with less than 3 social risks (Wald X2 = 9.34; aOR 2.3; 95% CI [1.4 – 3.9]; p-value = 0.002), after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 3:

Association between cumulative social risks measured by WE CAREǂ and domains of psychiatric risk measured by positive PSC-17ǂ ǂ total and subscale scores.

| Outcome: Positive PSC-17 Score | Wald X2ǂ ǂ ǂ | p-value | aOR (95% CI)ǂ ǂ ǂ ǂ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Total Score | 5.16 | 0.02* | 1.2 (1.1–1.5) |

| Positive Internalizing Score | 0.28 | 0.59 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| Positive Attention Score | 3.65 | 0.06 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| Positive Externalizing Score | 1.46 | 0.23 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

Note: Multivariable logistic regression model with cumulative social risks as the main predictor and positive PSC-17ǂ ǂ score (total or one of 3 subscales) as the outcome. Models were adjusted for the following confounders: age, sex, race/ethnicity, language, and insurance.

Denotes significant difference at p-value = 0.05.

WE CARE = Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education.

PSC-17 = Pediatric Symptom Checklist, 17 item version.

Wald X2 indicates Chi-squared test statistics.

aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio and CI = Confidence Interval.

Figure 1a.

Receiver Operating Characteristic curve of positive PSC-17 total score at possible WE CARE cut-offs

Figure 1b.

Odds of positive PSC-17 total score at possible WE CARE cut-offs

Multivariable logistic regression models with the three PSC-17 subscales as outcomes revealed that higher numbers of social risks did not increase the odds of having a positive attention subscale score (Wald X2 = 2.79; aOR 1.2; 95% CI [0.9–1.4]; p-value = 0.09), a positive externalizing subscale score (Wald X2=2.43; aOR 1.2; 95% CI [0.9–1.4]; p-value = 0.12) or a positive internalization score (Wald X2 = 0.28; aOR 1.1; 95% CI [0.9–1.3]; p-value = 0.59).

Association between cumulative social risks and psychiatric symptoms

Due to previous literature demonstrating that PSC-17 scale cut-offs may be specific but not sensitive for psychiatric disorders30 - and thus concern that a multivariable logistic regression model using these cut-offs would miss clinically relevant associations - we also performed a multivariable linear regression model to assess the relationship between cumulative risks and continuous PSC-17 total and subscale scores. In this model, cumulative social risks were significantly associated with the PSC-17 total score (t-statistics = 2.51; βestimate = 0.39; p-value = 0.01) as well as the PSC-17 attention subscale score (t-statistics=2.57; βestimate = 0.18; p-value = 0.01) and the internalizing subscale score (t-statistics= 2.05; βestimate = 0.10; p-value = 0.04), but not with the externalizing subscale score (t-statistics = 1.56; βestimate = 0.11; p-value = 0.12).

Association between individual social risks and psychosocial dysfunction

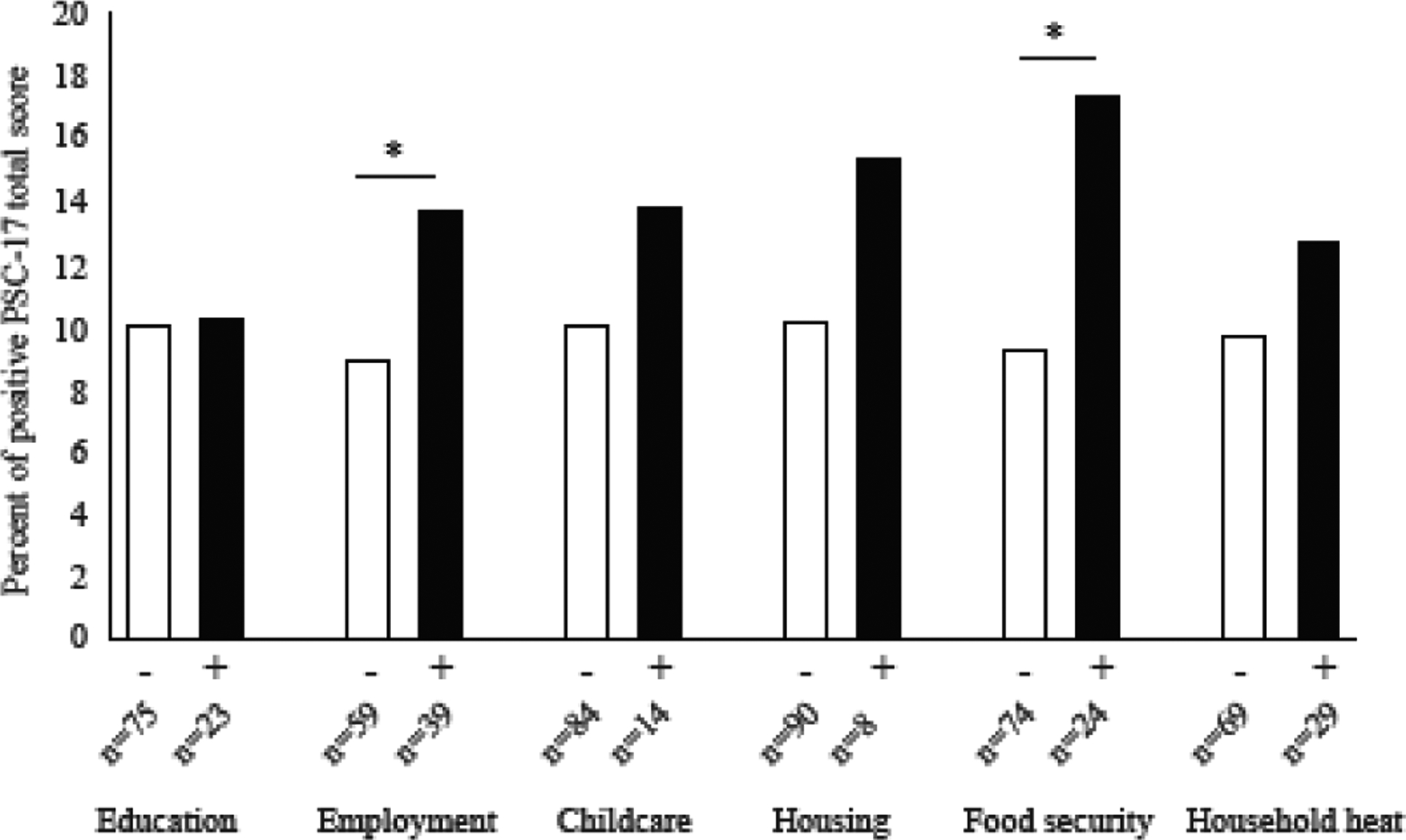

Of the six individual social risks, food security and employment were significantly associated with a positive PSC-17 total score (Table 4 and Figure 2). Children with food insecurity were 2.1 times as likely to have a positive PSC-17 total score compared to children with food security (X2 = 9.22; 95% CI [1.3–3.5]; p-value = 0.002). Children with an unemployed caregiver were 1.6 times as likely to have a positive PSC-17 total score (X2 = 4.31; 95% CI [1.1–2.4]; p-value = 0.03).

Table 4.

Odds of positive total PSC-17ǂ score in children with vs. without individual social risks on WE CAREǂ ǂ.

| Percent (%) of children with a positive PSC-17 total score | X2ǂ ǂ ǂ | p-value | OR (95% CI)ǂ ǂ ǂ ǂ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (−) Risk | With (+) Risk | ||||

| Individual risks: | |||||

| Parent Education | 10.3% | 10.6% | 0.01 | 0.91 | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) |

| Employment | 9.0% | 13.5% | 4.31 | 0.03* | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) |

| Child care | 10.0% | 13.2% | 1.02 | 0.31 | 1.3 (0.7–2.5) |

| Housing | 10.1% | 16.0% | 1.78 | 0.18 | 1.7 (0.7–3.7) |

| Food security | 9.2% | 17.8% | 9.22 | 0.002* | 2.1 (1.3–3.5) |

| Household heat | 9.7% | 12.7% | 1.75 | 0.19 | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) |

Denotes significant difference at p-value = 0.05.

PSC-17 = Pediatric Symptom Checklist, 17 item version.

WE CARE = Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education.

X2 = Chi-squared test statistic.

OR = Odds Ratio and CI = Confidence Interval.

Figure 2.

Bivariate analysis comparing percent of children with positive PSC-17 total scores with and without individual social risks.

In the multivariable logistic regression model including the six individual social risks (Table 5), only food security was significantly associated with positive PSC-17 total score after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and other social risks (Wald X2 = 5.48; p-value = 0.02). Children with food insecurity had increased odds of a positive PSC-17 total score compared to food secure children (aOR 1.9; 95% CI [1.1–3.4]). Children with food insecurity also had increased odds of a positive PSC-17 attention subscale score (Wald X2 = 4.71; aOR 1.9; 95% CI [1.1 – 3.4]; p = 0.03) compared to food secure children.

Table 5.

| Predictor | Wald X2ǂ ǂ ǂ | p-value | aOR (95% CI)ǂ ǂ ǂ ǂ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Education | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) |

| Employment | 0.35 | 0.56 | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) |

| Child care | 0.38 | 0.54 | 1.2 (0.7–2.3) |

| Housing | 0.35 | 0.55 | 1.3 (0.5–2.9) |

| Food security | 5.48 | 0.02* | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) |

| Household heat | 0.05 | 0.82 | 1.1 (0.6–1.7) |

Note: Multivariable logistic regression outcome is a Positive Total Score on the 17-item Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC-17). There are six main predictors. For each of the main predictors, the model was adjusted for the other social risks and potential confounders – age, sex, race/ethnicity, language, and insurance.

Denotes significant difference at p-value = 0.05.

WE CARE = Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education.

PSC-17 = Pediatric Symptom Checklist, 17 item version.

Wald X2 indicates Chi-squared test statistics.

aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio and CI = Confidence Interval.

Discussion

Over half of the diverse children at this urban, hospital-based, primary care practice had at least one social risk, and the number of social risks were significantly associated with psychosocial dysfunction. School-age children with food insecurity and those with 3 or more social risks - identified using a simple screen of six social risks in primary care - had over twice the rate of psychosocial dysfunction as their peers. These findings are novel in that they suggest that urban children with 3 or more risks on the WE CARE screener are at particularly high risk for psychosocial dysfunction, and distinguish food insecurity from other risks as most problematic for child mental health, particularly with regard to attention problems. These results extend the current understanding of the relationship between social risks and mental health of school-age children, and how social risk screening can be used in primary care to identify children at high risk for mental health problems related to these risks.

We found that a higher number of social risks were associated with more psychiatric symptoms and higher rates of psychosocial dysfunction, consistent with past literature supporting a cumulative risk model of the deleterious effects of psychosocial stressors on psychiatric outcomes.16,17,31–33 However, while existing literature largely supports a linear cumulative risk model of the association between childhood psychosocial stressors and psychiatric problems in both childhood and adulthood, our study findings offer several important new insights. First, we measured only specific social risks that could be addressed in pediatric primary care using the validated screening tool, WE CARE.21 This is the first study to show that children with higher WE CARE scores are at increased odds of mental health problems, and that a score of 3 on WE CARE could be used to identify children most vulnerable to psychosocial dysfunction. Children with 3 or more risks reported by caregivers (13.8% of our sample) had more than twice the odds of having a positive PSC-17 total score compared to peers with lower scores. Thus, children with a score of 3 or higher on WE CARE may need more intensive monitoring for mental health problems, and may be important candidates for preventive mental health interventions. Furthermore, our findings suggest that children with positive PSC-17 scores should be screened for social risks that can be addressed as part of comprehensive treatment planning.

Second, we found that all six modifiable social risks were not equal predictors of psychosocial dysfunction in children. Food insecurity - present in 1 of every 7 families in our sample - was the only individual risk associated with increased psychosocial dysfunction once we controlled for sociodemographic and other social risks. Food insecurity was associated with twice the odds of a positive PSC-17 total score, and with increased odds of a positive PSC-17 attention score as well. This is consistent with existing literature that food insecurity negatively impacts general cognitive development and psychological functioning.19,34–37 Others have also found a specific association between food insecurity and attention/hyperactivity problems in young children,18,38 and our findings suggest that this association continues into the school-age, which could negatively impact academic success and peer relationships. Food insecurity may impact child mental health and increase attention problems via a variety of hypothesized mechanisms. First, inadequate nutrition may lead to low dietary intake of essential vitamins, iron and fatty acids, which may worsen attention and cognition.18 Second, food insecurity may cause high levels of stress, anxiety and depression in caregivers, which may in turn cause mental health problems and inattention/hyperactivity in children.39 Second, food insecurity may be associated with other risk factors that we did not measure, such as single parenthood, severe poverty, or unwell caregivers. Although more work is needed to understand the contributions of these factors to our results, our findings nonetheless support the importance of detecting and addressing food insecurity as a critical part of preventive pediatric health care. Children with food insecurity should also be monitored for mental health problems - particularly attention and hyperactivity - and could be candidates for preventive mental health interventions initiated in primary care.

Importantly, social risk screening is not synonymous with, nor a substitute for, mental health screening. As expected, the majority of children with multiple social risks did not have positive PSC-17 scores. In addition, the majority of children with positive PSC-17 scores did not have multiple social risks. However, our findings highlight the fact that these tools could be used together to enhance treatment planning, and that the mental health of children with social risks may need to be monitored closely.

Our study has some limitations. This was a retrospective chart review of cross-sectional data, and thus we cannot establish temporal relationships or causality of the associations found. The screeners were administered as part of standard clinical practice at well child visits in a large, urban, safety net hospital-based pediatric practice, and only about one-third of children had both completed questionnaires in their medical records. This was largely due to a low completion rate of WE CARE, which had been recently implemented, and highlights the challenges of beginning social risks screening in a busy primary care practice. Despite this limitation, we were still able to retain a large sample with information on social risks and psychosocial functioning for analysis, and there were no meaningful differences between children with complete and incomplete questionnaires. We also did not have data on whether caregivers thought they needed help related to each risk, and so we do not know whether families’ social needs matched these measured risks, and whether this would more or less robustly predict psychosocial functioning. We also had very few children with four or more social risks on the WE CARE screener, and thus we were not able to reliably report on the effect of social risk accumulation past three risks. Children in our study were mostly publicly insured and non-white; thus, our findings may not generalize to other populations. We did not have information about income, because income is not included in WE CARE and the EMR does not otherwise contain this information. Thus, we used public insurance as a proxy, which may have obscured income differences that would have clarified the role of income in our findings. Finally, due to the sample size, we may have been inadequately powered to detect other clinically meaningful differences. Despite these limitations, our study extends the current literature on the association between social risks and psychosocial dysfunction in children and their detection in primary care.

Conclusions

In this study, we found a positive association between cumulative social risks and psychosocial dysfunction in school-age children. Individually, food insecurity was the only risk examined that was positively associated with psychosocial dysfunction, in particular attention problems. Our results suggest that screening for food insecurity and other social risks using a primary care based tool such as WE CARE can be combined with well-validated psychosocial screening tools such as the PS-17 to identify and appropriately treat children whose mental health may be impacted by adverse social conditions.

What’s New:

School-age children with food insecurity and those with 3 or more social risks - identified using a screen of six social risks in primary care - had over twice the rate of psychosocial dysfunction as their peers.

Funding Source:

This work was supported by grants from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the National Institute of Mental Health, K23 (1K23MH118478-01). The funders had no role in the design of this study nor collection of data.

Abbreviations:

- PSC-17

Pediatric Symptom Checklist, 17-item version

- WE CARE

Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education

- SDoH

Social Determinants of Health

- ACEs

Adverse Childhood Experiences

- ICC

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in US Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Study-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(1):7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Copeland WE, Wolke D, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Adult Functional Outcomes of Common Childhood Psychiatric Problems: A Prospective, Longitudinal Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(9):892–899. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello EJ, Angold A, Keeler GP. Adolescent outcomes of childhood disorders: the consequences of severity and impairment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(2):121–128. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodman A, Joyce R, Smith JP. The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(15):6032–6037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016970108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232–246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadsworth ME, Achenbach TM. Explaining the link between low socioeconomic status and psychopathology: testing two mechanisms of the social causation hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1146–1153. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans GW, Cassells RC. Childhood Poverty, Cumulative Risk Exposure, and Mental Health in Emerging Adults. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2(3):287–296. doi: 10.1177/2167702613501496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NCCP | Child Poverty. http://www.nccp.org/topics/childpoverty.html. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 10.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pediatrics C on C. Poverty and Child Health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, Beardslee WR. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: implications for prevention. Am Psychol. 2012;67(4):272–284. doi: 10.1037/a0028015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikulina V, Widom CS, Czaja S. The role of childhood neglect and childhood poverty in predicting mental health, academic achievement and crime in adulthood. Am J Community Psychol. 2011;48(3–4):309–321. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9385-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basch CE. Inattention and hyperactivity and the achievement gap among urban minority youth. J Sch Health. 2011;81(10):641–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, et al. The delinquency outcomes of boys with ADHD with and without comorbidity. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011;39(1):21–32. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9443-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sameroff A, Seifer R, Zax M, Barocas R. Early indicators of developmental risk: Rochester Longitudinal Study. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(3):383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Barocas R, Zax M, Greenspan S. Intelligence quotient scores of 4-year-old children: social-environmental risk factors. Pediatrics. 1987;79(3):343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melchior M, Chastang J-F, Falissard B, et al. Food Insecurity and Children’s Mental Health: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinman RE, Murphy JM, Little M, et al. Hunger in children in the United States: potential behavioral and emotional correlates. Pediatrics. 1998;101(1):E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassuk EL, Richard MK, Tsertsvadze A. The Prevalence of Mental Illness in Homeless Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(2):86–96.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e296–304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg A, Cull W, Olson L, et al. Screening and Referral for Low-Income Families’ Social Determinants of Health by US Pediatricians. Acad Pediatr. May 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.05.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardner W, Murphy M, Childs G, et al. The PSC-17: A brief pediatric symptom checklist with psychosocial problem subscales. A report from PROS and ASPN. Ambul Child Health. 1999;5(3):225–236. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy JM, Bergmann P, Chiang C, et al. The PSC-17: Subscale Scores, Reliability, and Factor Structure in a New National Sample. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Thompson RE, Serwint JR. Improving the management of family psychosocial problems at low-income children’s well-child care visits: the WE CARE Project. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):547–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardner W, Lucas A, Kolko DJ, Campo JV. Comparison of the PSC-17 and alternative mental health screens in an at-risk primary care sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(5):611–618. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318032384b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoppelbein L, Greening L, Moll G, Jordan S, Suozzi A. Factor analyses of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 with African-American and Caucasian pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(3):348–357. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erdogan S, Ozturk M. Psychometric evaluation of the Turkish version of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 for detecting psychosocial problems in low-income children. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(17–18):2591–2599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Copyright © [2014] SAS Institute Inc. SAS and All Other SAS Institute Inc. Product or Service Names Are Registered Trademarks or Trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

- 30.Spencer AE, Plasencia N, Sun Y, et al. Screening for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Comorbidities in a Diverse, Urban Primary Care Setting. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018;57(12):1442–1452. doi: 10.1177/0009922818787329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank DA, Casey PH, Black MM, et al. Cumulative Hardship and Wellness of Low-Income, Young Children: Multisite Surveillance Study. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1115–e1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Appleyard K, Egeland B, van Dulmen MHM, Sroufe LA. When more is not better: the role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(3):235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forehand R, Biggar H, Kotchick BA. Cumulative risk across family stressors: short- and long-term effects for adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26(2):119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinreb L, Wehler C, Perloff J, et al. Hunger: its impact on children’s health and mental health. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4):e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Food Insufficiency and American School-Aged Children’s Cognitive, Academic, and Psychosocial Development. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Casey PH, et al. Household food insecurity: associations with at-risk infant and toddler development. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):65–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slopen N, Fitzmaurice G, Williams DR, Gilman SE. Poverty, food insecurity, and the behavior for childhood internalizing and externalizing disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(5):444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murphy JM, Wehler CA, Pagano ME, Little M, Kleinman RE, Jellinek MS. Relationship between hunger and psychosocial functioning in low-income American children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):163–170. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199802000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knowles M, Rabinowich J, Ettinger de Cuba S, Cutts DB, Chilton M. “Do You Wanna Breathe or Eat?”: Parent Perspectives on Child Health Consequences of Food Insecurity, Trade-Offs, and Toxic Stress. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(1):25–32. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1797-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]