Abstract

Mycorrhizal symbiotic relationship is one of the most common collaborations between plant roots and the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF). The first barrier for establishing this symbiosis is plant cell wall which strongly provides protection against biotic and abiotic stresses. The aim of this study was to investigate the gene expression changes in cell wall of wheat root cv. Chamran after inoculation with AMF, Funneliformis mosseae under two different irrigation regimes. To carry out this investigation, total RNA was extracted from the roots of mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal plants, and analyzed using RNA-Seq in an Illumina Next-Seq 500 platform. The results showed that symbiotic association between wheat and AMF and irrigation not only affect transcription profile of the plant growth, but also cell wall and membrane components. Of the 114428 genes expressed in wheat roots, the most differentially expressed genes were related to symbiotic plants under water stress. The most differentially expressed genes were observed in carbohydrate metabolic process, lipid metabolic process, cellulose synthase activity, membrane transports, nitrogen compound metabolic process and chitinase activity related genes. Our results indicated alteration in cell wall and membrane composition due to mycorrhization and irrigation regimes might have a noteworthy effect on the plant tolerance to water deficit.

Keywords: Arbuscular mycorrhizae, Plant cell wall, RNA-Seq, Triticum aestivum, Water deficit

Introduction

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the main crops containing high carbohydrate content that provides more than one-third of the world population’s food (Gill et al. 2004). Water deficiency is considered as one of the most significant limiting factors of wheat crop production and plant growth parameters in Iran (Nezhadahmadi et al. 2013), and other arid and semi-arid areas all around the world (Li et al. 2019). One of the most beneficial cooperation in the environment that can decrease adverse effects of abiotic stresses is arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis, in which mutualistic confrontation is beneficial for both plant and fungi (Ye et al. 2019). To colonize and establish a relationship, root cell wall is the first and basic border that must be passed by AMF, and initiate an interaction and nutrient exchange (Rich et al. 2014). Cell wall as the outermost part of the plant cells plays crucial roles in growth, development, preservation of the cell shape, as well as protection against variety of external and internal factors for plant (Essahibi et al. 2018). As apoplastic compartments of plant cell, cell wall and membrane are directly involved in establishment and development of the mycorrhizal symbiosis. For constructing the symbiotic structure in roots of host plant, it needs to access cell wall and membrane materials to make a conservative envelope which keeps and improves symbiotic relationship, and also plant cells integrity (Essahibi et al. 2018). Guether et al. (2009) have reported the induced genes related to plasma membrane and cell wall activities affected by AMF as plant response to water stress. Nanjareddy et al. (2017) performed comparative transcriptome analysis of Phaseoulus vulgaris symbiotic-roots with AMF and identified differentially expressed genes associated with defense responses and cell wall. Recently, next generation sequencing (NGS) based on transcriptome (TC) has provided rapid genome wide transcript profiling. Transcriptome based analysis of genes helps to better understand biological processes including development, organogenesis and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (Zhu et al. 2012; Brenchley et al. 2012; Jayasena et al. 2014; Lucas et al. 2014). Dong et al. (2012) used Illumina (NGS) for studying gene expression changes in Sinapis alba under water stress. However, identification of all genes associated with AMF symbiosis demands extensive further research (Garcia et al. 2017; Sugimura and Saito 2017; An et al. 2018; Nanjareddy et al. 2017; Li et al. 2018; Jacott et al. 2017). The experimental hypothesis of the present study was that the mycorrhization could improve the wheat tolerance to water stress by changing cell wall and membrane genes expression pattern in addition to the other common factors that influence the plant tolerance. To test the hypothesis, the contribution of an AM fungal species (Funneliformis mosseae) to a drought semi-tolerant cultivar, “Chamran”, was studied in both normal irrigation and water deficit conditions. Moreover, gene expression changes in cell membrane and cell wall were investigated using transcriptome analysis. This can be the first study on bread wheat plants, in which we exposed plants to four different growth conditions using AMF alleviation and different irrigation regimes, and our concentration has been on some genes related to cell wall and membrane and their relation with enhancement of plant tolerance to water shortage.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

The wheat cultivar Chamran, a drought semi-tolerant cultivar, was used in this study. Seeds were surface-sterilized in 70% ethanol for 2 min, rinsed in sterile distilled water for three times, and soaked in 40% sodium hypochlorite for 10 min. Finally, seeds were rinsed six times in sterile distilled water. To germinate seeds, they were transferred into sterile Petri dishes with wet filter papers at 26 °C. After 3 days, 10 germinated seeds were planted into each 0.5 L plastic autoclaved pots containing sterile field soil, sand and perlite (2:1:1, V:V:V). The air-dried soil samples which collected from Tehran, Iran, were passed through a 2 mm sieve, and diluted with sand and perlite, sterilized for 1 h using 100 °C steaming on 3 consecutive days. The pH of soil was 8; the texture of soil before mixing was composed of 35.5% sand, 15.4% clay, 48.7% silt, and almost 0.5% organic matters.

AMF and water deficit treatments

In order to evaluate the effect of AMF and water deficit on transcript level of Chamran cultivar, four combinations of treatments were performed in a factorial experiment design in two levels for both AMF (inoculated and non-inoculated) and irrigation (normal and water deficit) with three replications and 10 seedlings per replicate. For AMF inoculation, Funneliformis mosseae, isolate Gmb17, was provided by Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Rafsanjan University, Iran.

Inoculum was prepared in the pots containing 100–120 mycorrhizal infection unit/g of a mixture of soil and sand and the germinated seeds were planted.

The pots of each level of AMF treatment, inoculated and non-inoculated plants, were irrigated in two levels including normal irrigation (each pot three times weekly, 50 ml each time) and water deficit condition (each pot three times weekly irrigating, 25 ml per time) for 8 weeks.

Mycorrhizal colonization assessment

For colonization assessment, four 8-week old plants and 15 segments of roots of both AMF treatments were removed and washed in tap water. After washing, the roots were cleared in 10% KOH solution, and stained with 0.1% trypan blue according to Phillips and Hayman method (1970). For evaluating of colonization, roots were cut down into 1 cm fragments and located on microscopic slides in lactoglycerol. Analysis of colonization percentage was performed based on McGonigle et al. (1990) and under a light microscope.

Assessment of plant growth parameters

After 8 weeks, plants were harvested and some growth related parameters such as root and shoot lengths, root and shoot fresh weights, and spike fresh weight were measured.

RNA extraction and NGS sequencing

Eight weeks after transplanting germinated seeds into the pots, two biological replicates of root samples were prepared from each treatment, including mycorrhizal plants in normal irrigation and water deficit conditions and also non-mycorrhizal plants in normal irrigation and water deficit condition. Each biological replicate contained a pooled root sample of 10 seedlings. Then, total RNA was extracted from 30 mg of root tissues of each pooled sample using Qiagen kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction and immediately stored at − 80 °C. RNA integrity and concentration was measured using gel electrophoresis and Agilent 2100 Bio-analyzer. An Illumina TruSeq stranded total RNA HT sample preparation kit was used to convert total RNA into library based on manufacturer’s instruction with an average library size of 360 bp. The reads were de-multiplexed with one allowed mismatch and “no lane splitting”. Libraries were sequenced using an Illumina Next Seq 500/High Output Chemistry with 150 bp paired-end reads. Estimated output was approximately 120 Gb and 800 Million reads, paired-end sequencing with 150 bp read length generated from eight samples.

Paired-end RNA-seq reads were mapped to wheat reference genome (http://plants.ensemble.org/Triticum_aestivum; Clavijo et al. 2017) using TopHat v2.1.1 (http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml; Kim et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. 2013) and Bowtie2 v2.2.9 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012). Assembling of transcripts and determining their expression level were performed using Cufflinks (v2.2.1) based on fragments per kb of exon per million mapped reads (FPKM). A q value of 0.01 and Log twofold change (LOG2FC) ≥ 2 and ≤ − 2 was considered as significant threshold for gene differential expression.

Quantitative real-time-PCR analysis

The quantitative RT-PCR was performed to validate the RNA-Seq data in four randomly selected transcripts. Gene specific primers were designed using Oligo 7 software. Total RNA from control and treatment of each condition was treated with 1.5 µl DNAaseI to remove DNA contamination. cDNA was synthesized by mixing 2 µg of total RNA, 0.2 µl specific primers, 0.5 µl Oligo dT and 10 µl DEPC water using Thermo-scientific kit according to manufactures’ instructions. Then, the mixture was incubated at 65 °C for 10 min; 10 µl of thermo-scientific master mix 2X was added, and the samples were incubated at 42 °C for 90 min.

Real-time PCR was carried out using Step-one RT-PCR and 1 µl of cDNA template, 0.3 µl of primers, 3 µl SYBR green mix 5X Takara mix, 0.25 µl ROX and 15 µl DEPC water. The PCR cycling program included of: 94 °C for 120 s, 94 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 20 s, and melting curve point was tested in the range of 60 and 95 °C with a heating rate of 5 °C for every 15 s. Treatment and control samples were assessed in two independent biological replicates.

The relative expression was calculated using 2−∆∆CT method (Rasmussen 2001). Elongation factor-1-alpha (EF-1α) gene (AF475129), a housekeeping gene, was used as endogenous gene to normalize the expression level of the target genes (Balestrini and Lanfranco 2006).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was carried out using SPSS program. The mean differences were estimated based on the Duncan test at a probability of 5%.

Result

Detection of mycorrhizal colonization percentage

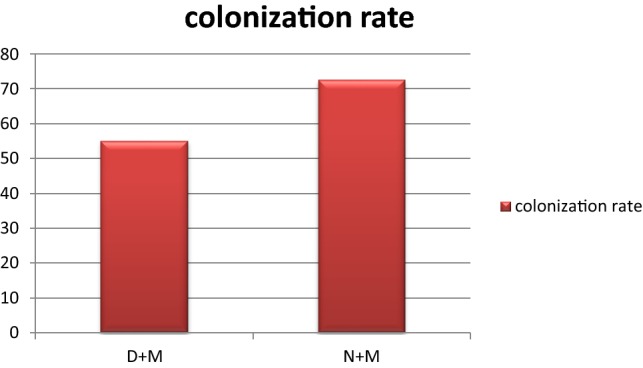

Non-inoculated roots did not show any colonization with AMF in roots. The colonization rate in inoculated roots under water deficiency and normal irrigated plants was 55% and 72.5% respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Colonization rate of two inoculated treatments: D + M: mycorrhizal plants under water deficiency, N + M: non-mycorrhizal plants with normal irrigation

Analysis of plant growth related traits

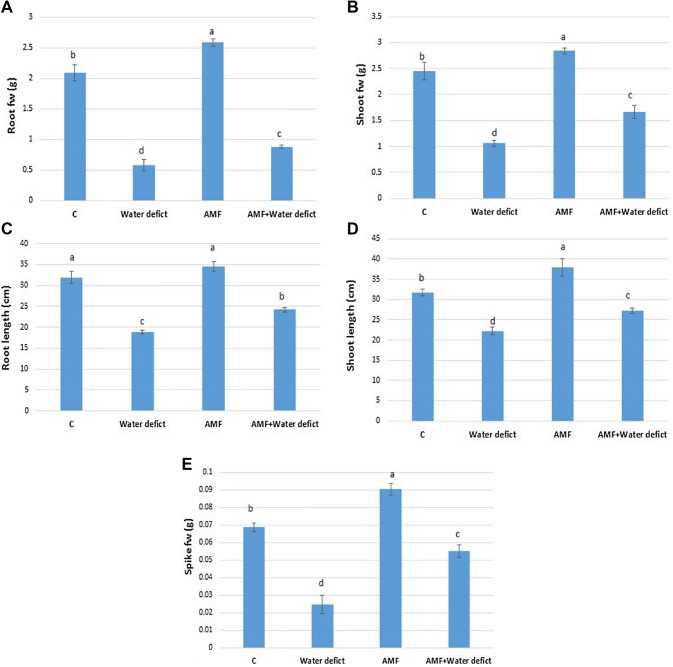

The individual application of AMF significantly increased root fresh weight by 23.8% when compared to the untreated control (Fig. 2a). Water deficit treatment led to the significant decrease in root fresh weight by 72.5% relative to the control. Interestingly, the mycorrhiza treatment mitigated the growth inhibition associated with water deficit by 15.5% (Fig. 2a). Showing similar trend, AMF inoculation enhanced shoot fresh weight by 15.6% than the control. Water deficit significantly reduced shoot fresh weight by 56.7% which was relieved by AMF supplementation and reached to 32% in the AMF + Water deficit treatment group (Fig. 2b). Similarly, the water deficit was associated with significant decrease in both root and shoot length (Fig. 2c, d). Moreover, water deficit-associated reduction in spike fresh weight was significantly alleviated by AMF utilization (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Water deficit and/or mycorrhiza-mediated changes in growth-related parameters. a root fresh weight, b shoot fresh weight; c root length, d shoot length; e spike fresh weight. Bars indicate the standard errors

Bioinformatic analysis of NGS RNA-Seq data

To perform bioinformatics analysis, TopHat Alignment software v 2.1.1 was used, and reads trimmed to 125 bp; also, read mapping and FRKM estimation of reference genes and transcripts were performed using TopHat 2 aligner. Assembly of novel transcripts, and differential expression of novel and reference transcripts were implemented with Cufflinks v 2.2.1 software. The summary of the bioinformatics data obtained in this study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Read numbers achieved from bioinformatics analysis

| Sample name | Sequenced reads | Overall read mapping rate (%) | Aligned pairs | Multiple alignments | Discordant alignments | Concordant alignment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (D − M) | 59651235 | 56.1 | 31304199 | 2720387 (8.7%) | 757957 (2.4%) | 51.2 |

| E (D − M) | 63094284 | 55.1 | 32499992 | 3114223 (9.6%) | 898573 (2.8%) | 50.1 |

| B (D + M) | 68576329 | 51.2 | 32762588 | 5609760 (17.1%) | 1951342 (6.0%) | 44.9 |

| D (D + M) | 81053620 | 49.9 | 37989411 | 5144110 (13.5%) | 1626126 (4.3%) | 44.9 |

| G (N − M) | 72618555 | 44.6 | 29503597 | 2708038 (9.2%) | 642998 (2.2%) | 39.7 |

| K (N − M) | 63905579 | 38.7 | 22643132 | 4092368 (18.1%) | 1217924 (5.4%) | 33.5 |

| H (N + M) | 64067079 | 49.4 | 29488910 | 2548789 (8.6%) | 656539 (2.2%) | 45.0 |

| I (N + M) | 59966731 | 51.2 | 28647390 | 2643137 (9.2%) | 742274 (2.6%) | 46.5 |

D − M: non-mycorrhizal roots under water deficiency, N − M: non-mycorrhizal roots with normal irrigation, D + M: mycorrhizal roots under water deficiency, N + M: mycorrhizal roots with normal irrigation

Paired-end RNA-Seq reads were obtained from each library aligned to Triticum aestivum genome sequence accessible at http://plants.ensemble.org/Triticum_aestivum for distinguishing per gene molecular function or biological processes. Log 2 fold change (LOG2FC) ≥ 2 and ≤ − 2 were considered for dividing genes to two up-regulated and down-regulated genes, subsequently.

Differentially expressed genes

In the present study, we generated four libraries including non-mycorrhizal roots with normal irrigation (N − M), mycorrhizal roots with normal irrigation (N + M), non-mycorrhizal roots under water deficiency (D − M) and mycorrhizal root under water deficiency (D + M).

While the published “Triticum aestivum L.” transcriptome includes 174639 gene transcripts, from among, 104390 are coding genes and 18087 are non-coding genes (http://plants.ensemble.org/Triticum_aestivum), we totally found 114428 genes expressed in wheat roots from four libraries of which, 12774 transcript were differentially expressed, 8754 transcripts had known biological process and molecular function; 1022 transcripts were non-coding and others were still unknown for their biological and molecular functions.

The number of identified genes in each library and treatment is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of identified genes in four different libraries

| Data | N − M | N + M | D − M | D + M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total annotated genes | 83691 | 84513 | 84418 | 85454 |

| Up-regulated genes | 10966 | 11825 | 10329 | 13405 |

| Down-regulated genes | 1709 | 2608 | 3226 | 2081 |

| Significant genes based on expression difference | 1759 | 4226 | 2701 | 4808 |

| Genes with known function | 1156 | 2535 | 1680 | 3049 |

| Genes with unknown function | 603 | 1691 | 1021 | 1759 |

| ncRNA (in significant genes) | 27 | 149 | 135 | 132 |

N − M: non-mycorrhizal roots with normal irrigation, N + M: mycorrhizal roots with normal irrigation, D − M: non-mycorrhizal roots under water stress D + M: mycorrhizal root under water stress

Transcriptome in each condition was screened for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with cell components namely cell wall and plasma membrane. Some genes were only induced or suppressed in one special treatment and considered as specific responsive genes.

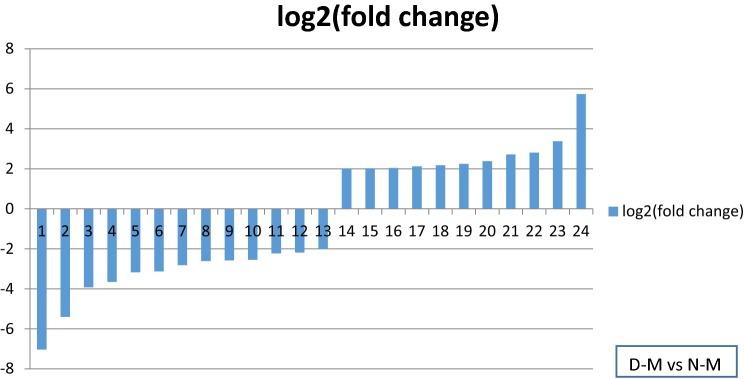

DEGs associated with cell wall and plasma membrane under water deficiency (D − M vs N − M)

Considering the cutoff threshold of log2 (≥ 2 and ≤ − 2) and q value of ≤ 0.01, a total number of 30 genes, associated with cell wall and plasma membrane showed significantly differential expression under water deficit. Among the up-regulated genes, chitinase activity, lipid metabolic process, lignin catabolic process and malate dehydrogenase activity genes were only induced in plants under water deficit condition but not in normal irrigation regime suggesting water deficit responsive genes (see Tables 3, 4 and Fig. 3). Compared to normal irrigation in our experiments, water deficit could also up-regulate the expression of genes related to carbohydrate metabolic process, lipid catabolic process, oxidation/reduction process, hydrolase activity and plant-type cell wall organization, and down-regulate the expression of genes associated with carbohydrate metabolic process, lipid metabolic process, transmembrane transport and cell wall macromolecule catabolic process (13 genes).

Table 3.

Induced and suppressed transcripts identified in wheat cv. Chamran under water-deficit

| Gene ID | Protein name | Value_1 (D-M) | Value_2 (N-M) | Accession ID in NCBI | Source organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_321131_AA1055910 | Anti-sigma-I factor RsgI6-like | 0 | 0.67093 | XM_020311775.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_320705_AA1046770 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 31-like | 0 | 0.41745 | XM_020338007.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_U_TGACv1_642890_AA2124500 | Chi gene for endochitinase | 1.97046 | 0 | X76041.1 | T.aestivum (Chinese spring) |

| TRIAE_CS42_7DS_TGACv1_622542_AA2041460 | Patatin-like protein 2 | 3.80167 | 0 | XM_020293126.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_6DL_TGACv1_526537_AA1686380 | Putative laccase-9 | 19.6026 | 0 | XM_020320013.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_344866_AA1150230 | Malate dehydrogenase [NADP] 1 | 12.0765 | 0 | XM_020325953.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

Table 4.

DEGs identified in wheat cv. Chamran showing down-regulation and up-regulation under water deficit

| Gene ID | Protein name | Log2 (fold change) | Accession ID in NCBI | Source organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_327875_AA1077360 | Protein ZINC INDUCED FACILITATOR-LIKE 1-like | − 7.0352 | XM_020334708.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_129932_AA0399780 | Beta-glucosidase BoGH3B-like | − 5.3941 | XM_020296045.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_133066_AA0441180 | WT003_M11 | − 3.9284 | AK332352.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_3DL_TGACv1_250209_AA0864280 | cht4 chitinase | − 3.6586 | KR049250.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DS_TGACv1_361542_AA1169880 | Putative clathrin assembly protein At1g33340 | − 3.1668 | XM_020300262.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_095187_AA0308020 | Beta-glucosidase BoGH3B-like | − 3.1291 | XM_020296045.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_129576_AA0389360 | Putative xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 13 | − 2.8189 | XM_020307537.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_130022_AA0401820 | WT003_N09 | − 2.6079 | AK332377.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_093126_AA0272780 | Fructan 6-exohydrolase | − 2.5755 | AB196524.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_U_TGACv1_643084_AA2127090 | Lipase-like | − 2.5461 | XM_020344369.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DL_TGACv1_158029_AA0506490 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 24-like | − 2.2207 | XM_020307539.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_328000_AA1080810 | HIPL1 protein-like | − 2.1827 | XM_020300864.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_328633_AA1091330 | sn1-specific diacylglycerol lipase beta | − 2.0071 | XM_020326437.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_7DL_TGACv1_604135_AA1994270 | Patatin-like protein 2 | 2.01008 | XM_020306914.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_132929_AA0440510 | Beta-glucosidase | 2.02 | AB236423.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BS_TGACv1_049914_AA0164140 | tplb0043f07 | 2.04793 | AK450976.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_320333_AA1035610 | B12 alpha expansin 6 (EXPA6) | 2.12293 | KC441067.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BS_TGACv1_049965_AA0164870 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-like | 2.18288 | XM_020317649.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_129561_AA0388630 | Beta-glucosidase | 2.25564 | AB100035.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_343409_AA1134090 | Omega-3 fatty acid desaturase, endoplasmic reticulum-like | 2.38774 | XM_020337300.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_328921_AA1095710 | Beta-tubulin (TUB) | 2.71602 | MG852134.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BS_TGACv1_050729_AA0174830 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-like | 2.81184 | XM_020319266.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_246242_AA0834280 | Expansin-A24-like | 3.38153 | XM_020322455.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_094425_AA0297430 | Beta-glucosidase | 5.74049 | AB548284.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

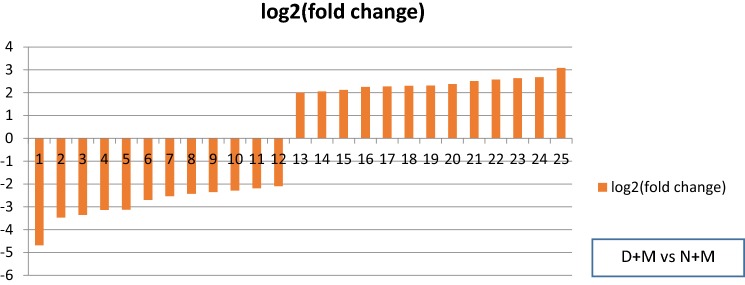

Fig. 3.

Log2 (fold change) of down and up-regulated genes under water stress. 1: transmembrane transport, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 12, 15, 19: carbohydrate metabolic process, 4: chitinase activity, 5: clathrin coat assembly, 7: xyloglucan metabolic process, 10, 13, 20: lipid metabolic process, 11: cellular glucan metabolic process, 14: lipid catabolic process, 16, 18, 22: l-phenylalanine catabolic process, 17, 23: plant-type cell wall organization, 21: microtubule-based process, 24: beta-glucosidase activity

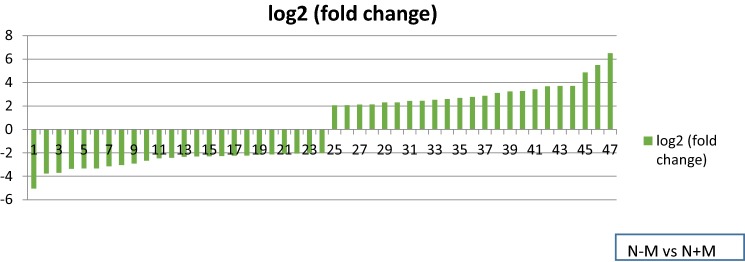

DEGs associated with cell wall and plasma membrane in AMF-colonized wheat root (N − M vs N + M)

This experiment was performed to identify the expressed genes in the symbiosis between mycorrhiza and wheat in normal irrigation. Generally, 23 and 24 up- as well as down-regulated genes related to cell wall and plasma membrane were identified, respectively (Table 5, Fig. 4).

Table 5.

DEGs identified in wheat cv. Chamran showing down-regulation and up-regulation in AMF colonized roots under normal irrigation

| Gene ID | Protein name | Log2 (fold change) | Accession ID in NCBI | Source organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_094425_AA0297430 | Beta-glucosidas | − 5.0471 | AB548284.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_129561_AA0388630 | Beta-glucosidase | − 3.7674 | AB100035.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_093096_AA0271920 | Probable xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 12 | − 3.7085 | XM_020317472.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_7AS_TGACv1_569995_AA1828380 | Expansin-A17-like | − 3.3671 | XM_020293675.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3AS_TGACv1_212195_AA0698660 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase protein 8-like | − 3.3353 | XM_020316160.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4AS_TGACv1_306275_AA1005550 | Phytosulfokines 4-like | − 3.3329 | XM_020303724.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_131489_AA0428390 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 12 | − 3.1424 | XM_020317472.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_329606_AA1102700 | Xylanase inhibitor | − 3.0417 | AB302973.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_7DS_TGACv1_622353_AA2038220 | Expansin-A17-like | − 2.9 | XM_020293675.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_342392_AA1112380 | Phytosulfokines 4-like | − 2.6674 | XM_020303724.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1DL_TGACv1_062431_AA0214390 | Patatin-like protein 1 | − 2.4622 | XM_020344309.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BL_TGACv1_033545_AA0140280 | Patatin-like protein 1 | − 2.4214 | XM_020344309.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_328921_AA1095710 | Beta-tubulin (TUB) | − 2.3301 | MG852134.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_327950_AA1079560 | WT005_P03 | − 2.299 | AK333221.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_5AL_TGACv1_374195_AA1193240 | Beta-glucosidase 30-like | − 2.2883 | XM_020332410.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_7BL_TGACv1_578733_AA1899350 | Agglutinin isolectin 3-like | − 2.2651 | XM_020325269.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3DS_TGACv1_271881_AA0910150 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase protein 8-like | − 2.2407 | XM_020316162.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_320919_AA1051690 | Isoform GSr1 (GS) | − 2.2254 | AY491968.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_345130_AA1151850 | Laccase-3-like | − 2.149 | XM_020292685.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DS_TGACv1_361309_AA1165460 | Beta-3 chain | − 2.1292 | XM_020308075.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BS_TGACv1_051414_AA0179560 | tplb0012l18 | − 2.0773 | AK456462.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DS_TGACv1_363201_AA1183500 | tplb0005g02 | − 2.0566 | AK454358.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_320618_AA1044770 | Laccase-3-like | − 2.0072 | XM_020292685.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3DL_TGACv1_250306_AA0865810 | Expansin-A8-like | − 2.0057 | XM_020317488.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_321498_AA1061390 | Beta-glucosidase 6 | 2.05694 | XM_020290811.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BS_TGACv1_049914_AA0164150 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-like | 2.08107 | XM_020317638.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DS_TGACv1_177268_AA0571460 | Uncharacterized | 2.12878 | XM_020322743.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DL_TGACv1_158049_AA0507280 | Aldose 1-epimerase-like | 2.13367 | XM_020290960.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_114151_AA0364450 | Gamma gliadin-A1 | 2.30073 | MG560140.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_113897_AA0362110 | Putative amidase C869.01 | 2.309 | XM_020311367.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AL_TGACv1_001256_AA0027880 | Endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase 13-like | 2.43686 | XM_020325014.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BL_TGACv1_033482_AA0139800 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase 13-like | 2.44328 | XM_020325006.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DS_TGACv1_360999_AA1158040 | SET4_M23 | 2.52346 | AK330584.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BL_TGACv1_030467_AA0091630 | ABC transporter B family member 11-like | 2.60003 | XM_009391731.2 | Musa acuminata subsp. malaccensis |

| TRIAE_CS42_1DS_TGACv1_080643_AA0251500 | Laccase-25-like | 2.68528 | XM_020300631.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4AL_TGACv1_290204_AA0982950 | tplb0045l10 | 2.78117 | AK451279.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_129780_AA0395640 | Triacylglycerol lipase 2-like | 2.87066 | XM_020303075.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BS_TGACv1_147826_AA0487990 | GT75-3 | 3.1223 | KM670460.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BS_TGACv1_146914_AA0475330 | 3.24964 | |||

| TRIAE_CS42_2DS_TGACv1_180213_AA0610440 | UDP-arabinopyranose mutase 3 | 3.27702 | XM_020345004.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_113522_AA0357250 | UDP-arabinopyranose mutase 3 | 3.42686 | XM_020345004.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BS_TGACv1_145994_AA0452200 | WT004_F09 | 3.68528 | AK332578.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DL_TGACv1_157981_AA0504650 | Beta-glucosidase 12-like | 3.70993 | XM_020329910.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_113828_AA0361200 | Syntaxin-132-like | 3.71212 | XM_020290887.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_331402_AA1109940 | Heparan-alpha-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase-like | 4.87088 | XM_020314296.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_327875_AA1077360 | Protein ZINC INDUCED FACILITATOR-LIKE 1-like | 5.5069 | XM_020334708.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BS_TGACv1_051503_AA0180180 | Alpha-mannosidase-like | 6.50912 | XM_020334225.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

Fig. 4.

Log2 (fold change) of down- and up-regulated genes in symbiotic normal-irrigated plants. 1: scopolin beta-glucosidase activity, 2, 8, 14, 15, 22, 25, 31, 32, 43: carbohydrate metabolic process, 3: xyloglucan metabolic process, 4, 9, 24, 33: plant-type cell wall organization, 5, 7, 17: cellular glucan metabolic process, 6, 10: growth factor activity, 11, 12, 21, 37: lipid metabolic process, 13, 20: microtubule-based process, 16: chitin binding, 18: nitrogen compound metabolic process, 19, 23, 35: lignin catabolic process, 26: l-phenylalanine catabolic process, 27, 29, 39: d-alanine ligase activity, 28: hexose metabolic process, 30: carbon–nitrogen ligase activity, 34: transmembrane transport, 36: long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase activity, 38, 41: cellulose biosynthetic process, 40: UDP-arabinopyranose mutase activity, 42, 44: SNAP receptor activity, 45, 46: integral component of membrane, 47: mannose metabolic process

Among DEGs, 13 significant genes classified as a group of carbohydrate metabolic process; 7 showed up-regulation, and 6 were down-regulated due to mycorrhizal symbiosis. Genes related to hexose metabolic process, UDP-arabinopyranose mutase activity and alpha mannosidase activity were up-regulated. 5 genes were associated with lipid metabolic process; 2 appeared as up-regulated, and three were down-regulated. 2 cellulose biosynthetic process genes indicated increase in their expression influenced by mycorrhization. Among down-regulated genes, 3 of them were related to plant-type cell wall organization, 2 were linked to cell proliferation, 2 genes were involved in microtubule based process; 4 genes were annotated as transmembrane transports.

Apart from normal irrigation condition in this comparison, AMF led to the expression of 19 genes that were not expressed in control plants (Table 6). The most of these induced genes were associated with transporter activity and cell growth, and this can be attributed to the effect of AMF on improving plant behavior.

Table 6.

Induced transcripts identified in wheat cv. Chamran AMF colonized roots in normal irrigation

| Gene ID | Protein name | Value 1 (N − M) | Value 2 (N + M) | Accession ID in NCBI | Source organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIAE_CS42_6DL_TGACv1_527547_AA1705600 | Laccase-21-like | 0 | 0.54396 | XM_020336472.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AL_TGACv1_000750_AA0018290 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase 13-like | 0 | 1.56382 | XM_020325012.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_132538_AA0438240 | Acidic endochitinase-like | 0 | 19.0282 | XM_020321162.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_130318_AA0408760 | Acidic endochitinase-like | 0 | 19.645 | XM_020321162.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_7DL_TGACv1_603253_AA1979180 | Putative cellulose synthase A catalytic subunit 11 | 0 | 1.02689 | XM_020331230.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AL_TGACv1_001368_AA0029420 | S-type anion channel SLAH2-like | 0 | 0.38224 | XM_020295652.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AS_TGACv1_021078_AA0080890 | CASP-like protein 4D1 | 0 | 2.29829 | XM_020308584.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_130367_AA0409580 | WAT1-related protein At1g68170-like | 0 | 1.79156 | XM_020322988.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3AS_TGACv1_211406_AA0689890 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-like | 0 | 0.66478 | XM_020341608.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_226641_AA0818320 | Ammonium transporter 3 member 1-like | 0 | 6.40827 | XM_020310974.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3DL_TGACv1_249337_AA0845800 | Sugar transport protein 1-like | 0 | 1.14417 | XM_020334105.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4AS_TGACv1_306829_AA1013910 | WAT1-related protein At1g68170-like | 0 | 0.7281 | XM_020338332.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_321771_AA1065240 | Heptahelical transmembrane protein 4-like | 0 | 0.85227 | XM_020290761.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_344866_AA1150230 | Malate dehydrogenase [NADP] 1 | 0 | 5.60577 | XM_020325953.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BL_TGACv1_031679_AA0118650 | Beta-glucosidase 22-like | 0 | 6.93309 | XM_020330200.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_129438_AA0383660 | COBRA-like protein 7 | 0 | 0.4556 | XM_020312442.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_130858_AA0418950 | Beta-glucosidase 12-like | 0 | 8.15626 | XM_020329910.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DS_TGACv1_180706_AA0611240 | COBRA-like protein 7 | 0 | 0.72135 | XM_020322746.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_112645_AA0342840 | Copper transporter 4-like | 0 | 0.59084 | XM_020325425.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

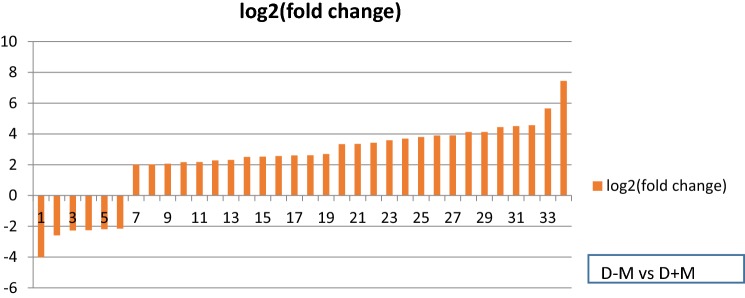

DEGs associated with cell wall and plasma membrane in AMF- roots under water deficit (D − M vs D + M)

Colonization of wheat roots with AMF changed the transcriptome profile of water-deficit plants. Compared to non-AMF roots, we observed 6 and 28 down-regulated and up-regulated genes in AMF-roots, respectively, which were associated with cell wall and plasma membrane (Table 7).

Table 7.

DEGs identified in wheat cv. Chamran showing down-regulation and up-regulation in AMF colonized roots under water deficiency

| Gene Id | Protein name | Log2(fold change) | Accession ID in NCBI | Source organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_224369_AA0795760 | HIPL1 protein-like | − 3.9997 | XM_020331354.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_320919_AA1051690 | Isoform GSr1 (GS) | − 2.5829 | AY491968.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4AS_TGACv1_307728_AA1023060 | Cereale cytosolic glutamine synthetase isoform (GS1-4) | − 2.2636 | JN188394.1 | Triticum turgidum subsp. durum |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DL_TGACv1_158029_AA0506490 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 24-like | − 2.2546 | XM_020307539.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_343321_AA1133210 | Glutamine synthetase isoform GSr2 (GS) gene | − 2.1786 | AY491969.1 | Triticum aestivum |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_093096_AA0271920 | Probable xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 12 | − 2.1437 | XM_020317472.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AL_TGACv1_002286_AA0040530 | Fatty acid amide hydrolase-like | 2.0061 | XM_020323605.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_112829_AA0345860 | Plastid acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Acc-1) gene | 2.02936 | EU660900.1 | Triticum aestivum |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_093900_AA0288950 | Beta-glucosidase 16-like | 2.07524 | XM_020327283.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_5BS_TGACv1_423370_AA1375340 | PI-PLC X domain-containing protein At5g67130-like | 2.16637 | XM_020312303.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DL_TGACv1_157992_AA0505150 | Beta-glucosidase 16-like | 2.17812 | XM_020327283.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_321498_AA1061390 | Beta-glucosidase 6 | 2.28425 | XM_020290811.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BL_TGACv1_030467_AA0091630 | ABC transporter B family member 11-like | 2.31482 | XM_009391731.2 | Musa acuminata subsp. malaccensis |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BL_TGACv1_032327_AA0128440 | WAT1-related protein At5g07050-like | 2.509 | XM_020338654.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DL_TGACv1_158049_AA0507280 | Aldose 1-epimerase-like | 2.51875 | XM_020290960.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BS_TGACv1_146482_AA0466120 | ABC transporter B family member 4-like | 2.56886 | XM_020293040.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_131851_AA0432880 | Aldose 1-epimerase-like | 2.60357 | XM_020290960.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_343670_AA1138050 | Protein transport protein Sec61 subunit alpha-like | 2.61792 | XM_020290809.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_112362_AA0336420 | ABC transporter B family member 4-like | 2.69261 | XM_020293040.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_129780_AA0395640 | Triacylglycerol lipase 2-like | 3.34377 | XM_020303075.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_113028_AA0350040 | ABC transporter C family member 14-like | 3.34819 | XM_020332672.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_6AL_TGACv1_474105_AA1534120 | 2-Alpha-l-fucosyltransferase-like | 3.42443 | XM_020309974.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DS_TGACv1_360999_AA1158040 | SET4_M23 | 3.58926 | AK330584.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4AL_TGACv1_290204_AA0982950 | tplb0045l10 | 3.70217 | AK451279.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_094425_AA0297430 | Beta-glucosidas | 3.80462 | AB548284.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DL_TGACv1_157981_AA0504650 | Beta-glucosidase 12-like | 3.89686 | XM_020329910.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_113828_AA0361200 | Syntaxin-132-like | 3.91589 | XM_020290887.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BS_TGACv1_145994_AA0452200 | WT004_F09 | 4.11817 | AK332578.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_113522_AA0357250 | UDP-arabinopyranose mutase 3 | 4.12231 | XM_020345004.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_221856_AA0751810 | Peptide-N4-(N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminyl)asparagine amidase A-like | 4.43885 | XM_020315658.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DS_TGACv1_180213_AA0610440 | UDP-arabinopyranose mutase 3 | 4.50941 | XM_020345004.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BS_TGACv1_147826_AA0487990 | GT75-3 | 4.56522 | KM670460.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_331402_AA1109940 | Heparan-alpha-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase-like | 5.66096 | XM_020314296.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BS_TGACv1_051503_AA0180180 | Alpha-mannosidase-like | 7.44879 | XM_020334225.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

The interaction between mycorrhiza and water-deficit, caused up-regulation of 28 genes related to carbohydrate metabolic process, fatty acid metabolic process, lipid metabolic process, transmembrane transport activity, hydrolase activity, cellulose biosynthetic process, mannose metabolic process and ligase activity. 11 of these genes (see Table 7 and Fig. 5) were classified as a group of carbohydrate metabolic process of which some of them had role in cell wall biogenesis, consisting of genes related to mannosidase activity, galactoside-2-alpha-L-fucosylteransferase activity, hexose metabolic process, β-glucosidase activity, UDP-arabinopyranose mutase and hydrolase activity. Two other genes were associated with cellulose biosynthetic process (KM670460.1, XM_020345004.1). In AMF plants, ten membrane-related genes as transporters and compartments were up-regulated in wheat plants under water deficit.

Fig. 5.

Log2 (fold change) of down and up-regulated genes under mycorrhizal water-stress plants. 1, 9, 11, 12, 26: carbohydrate metabolic process, 2, 3, 5: nitrogen compound metabolic process, 4: cellular glucan metabolic process, 6: xyloglucan metabolic process, 7: carbon–nitrogen ligase activity, 8: fatty acid biosynthetic process, 10, 20: lipid metabolic process, 13, 14, 16, 19, 21, 30: transmembrane transport, 15, 17: hexose metabolic process, 18, 33: integral component of membrane, 22: galactoside 2-alpha-l-fucosyltransferase activity, 23: plant-type cell wall, 24: long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase activity, 25: beta-glucosidase activity, 27, 28: SNAP receptor activity, 29, 32: cellulose biosynthetic process, 31: UDP-arabinopyranose mutase activity, 34: mannose metabolic process

In addition to up-regulated transcripts associated with cell wall and membrane, 25 genes were recognized only in AMF inoculated roots but not in the control samples suggesting AMF specific genes under water deficit.

However, only 1 gene was suppressed in the treated samples (Table 8).

Table 8.

Induced and suppressed transcripts identified in wheat cv. Chamran in AMF roots under water deficiency

| Gene ID | Protein name | Value 1 (D − M) | Value 2 (D + M) | Accession ID in NCBI | Source organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIAE_CS42_6DL_TGACv1_527547_AA1705600 | Laccase-21-like | 0 | 0.94653 | XM_020336472.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_132538_AA0438240 | Acidic endochitinase-like | 0 | 34.2003 | XM_020321162.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_130318_AA0408760 | Acidic endochitinase-like | 0 | 37.2347 | XM_020321162.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_096263_AA0318280 | COBRA-like protein 7 | 0 | 0.57753 | XM_020312442.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_7DL_TGACv1_603253_AA1979180 | Putative cellulose synthase A catalytic subunit 11 | 0 | 1.39848 | XM_020331230.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_6AL_TGACv1_472962_AA1527570 | Chitinase 6-like | 0 | 3.36273 | XM_020317430.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AL_TGACv1_001368_AA0029420 | S-type anion channel SLAH2-like | 0 | 1.48604 | XM_020295652.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AS_TGACv1_021078_AA0080890 | CASP-like protein 4D1 | 0 | 2.3401 | XM_020308584.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_130367_AA0409580 | WAT1-related protein At1g68170-like | 0 | 7.59737 | XM_020322988.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_131444_AA0427790 | Probable purine permease 11 | 0 | 1.81115 | XM_020344559.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3AS_TGACv1_210868_AA0680480 | Protein NRT1/PTR FAMILY 8.2-like | 0 | 1.02073 | XM_020335824.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3AS_TGACv1_211406_AA0689890 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-like | 0 | 1.25925 | XM_020341608.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_221895_AA0752610 | protein NRT1/PTR FAMILY 4.5-like | 0 | 36.8762 | XM_020341045.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_226641_AA0818320 | Ammonium transporter 3 member 1-like | 0 | 6.44725 | XM_020310974.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_227304_AA0822670 | Protein NRT1/PTR FAMILY 1.2-like | 0 | 3.71422 | XM_020312497.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3DL_TGACv1_249337_AA0845800 | Sugar transport protein 1-like | 0 | 0.63211 | XM_020334105.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4AS_TGACv1_306829_AA1013910 | WAT1-related protein At1g68170-like | 0 | 2.20539 | XM_020338332.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_321310_AA1058840 | Nitrate transporter (TaNPF6.1 gene) | 0 | 1.14233 | HF544988.1 | Triticum aestivum cv. Paragon |

| TRIAE_CS42_4BL_TGACv1_321771_AA1065240 | Heptahelical transmembrane protein 4-like | 0 | 1.55394 | XM_020290761.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_5AL_TGACv1_373992_AA1186890 | Nitrate transporter (TaNPF6.1 gene) | 0 | 1.86885 | HF544988.1 | Triticum aestivum cv. Paragon |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_094209_AA0294360 | Beta-glucosidase 12-like | 0 | 0.61419 | XM_020329909.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2DL_TGACv1_161025_AA0556070 | COBRA-like protein 7 | 0 | 0.69365 | XM_020312442.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_7AL_TGACv1_559082_AA1798000 | Class II chitinase gene | 0 | 1.06682 | AY973229.1 | Triticum aestivum cultivar Gamenya |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_093541_AA0282250 | HKT1 | 0 | 0.41727 | KF443078.1 | Triticum durum |

| TRIAE_CS42_3DL_TGACv1_251611_AA0883070 | UDP-glucuronate:xylan alpha-glucuronosyltransferase 1-like | 0 | 0.49347 | XM_020310973.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_6DL_TGACv1_526537_AA1686380 | Putative laccase-9 | 19.5213 | 0 | XM_020320013.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

DEGs related to cell wall and plasma membrane in AMF roots under water deficit and normal irrigation

In this experiment, the transcripts of AMF colonized roots under water deficit were compared to normal irrigation.

By evaluating the difference between their gene expression patterns, we identified 25 significantly DEGs associated with cell wall and plasma membrane. Among these, 12 and 13 genes down-regulated as well as up-regulated in D + M (Table 9 and Fig. 6). Regarding the slight difference between these two treatments, it could be concluded that the effect of mycorrhiza on the amount of expression was greater than that of irrigation regimes. 10 significantly expressed genes were categorized as a group of carbohydrate metabolic process of which half were down-regulated and the others were up-regulated. 2 up-regulated genes were involved in lipid metabolic process, and the remaining two had role in cell division and plant-type cell wall organization. Considering the specific genes, three were expressed only in D + M samples. Cellulose synthase activity, plant-type cell wall organization and carbohydrate metabolic process genes were found specific related to N + M, and the genes associated with lipid metabolic process, chitin binding and plant-type hypersensitive response only expressed in D + M (Table 10).

Table 9.

DEGs identified in wheat cv. Chamran showing down-regulation and up-regulation in AMF colonized roots under water deficit and normal irrigation

| Gene Id | Protein name | Log2(fold change) | Accession ID in NCBI | Source organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIAE_CS42_4BS_TGACv1_328907_AA1095330 | Cytosolic glutamine synthetase (GSe-B4) gene | − 4.6836 | KF242513.1 | Triticum turgidum |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DS_TGACv1_361179_AA1162880 | Glutamine synthetase cytosolic isozyme 1-3 | − 3.4703 | XM_020323172.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_129932_AA0399780 | Beta-glucosidase BoGH3B-like | − 3.3528 | XM_020296045.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_7BL_TGACv1_578733_AA1899350 | Agglutinin isolectin 3-like | − 3.1321 | XM_020325269.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_094425_AA0297430 | Beta-glucosidas | − 3.1248 | AB548284.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_5AL_TGACv1_374243_AA1194960 | Beta-glucosidase BoGH3B-like | − 2.6959 | XM_020293489.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_343897_AA1141200 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase 1-like | − 2.5333 | XM_020343229.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_7DL_TGACv1_602790_AA1968680 | Agglutinin isolectin 3-like | − 2.4325 | XM_020325269.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4AL_TGACv1_288277_AA0943450 | Cytosolic glutamine synthetase (GSe-A4) gene | − 2.3568 | KF242512.1 | Triticum turgidum |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_095187_AA0308020 | Beta-glucosidase BoGH3B-like | − 2.288 | XM_020296045.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_129561_AA0388630 | Beta-glucosidase | − 2.1882 | AB100035.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_2BL_TGACv1_130367_AA0409580 | WAT1-related protein At1g68170-like | − 2.0993 | XM_020322988.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1DS_TGACv1_080861_AA0254810 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-like | 2.00132 | XM_020319266.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_113168_AA0352430 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-like | 2.05164 | XM_020310911.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_224369_AA0795760 | HIPL1 protein-like | 2.11947 | XM_020331354.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BS_TGACv1_050729_AA0174830 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase-like | 2.24533 | XM_020319266.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_5AS_TGACv1_392939_AA1266520 | – | 2.27591 | CT009586.1 | Triticum aestivum |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AL_TGACv1_001387_AA0029810 | Chromosome 3B-specific BAC library | 2.29746 | FN564431.1 | Triticum aestivum |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AL_TGACv1_001256_AA0027880 | Endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase 13-like | 2.30594 | XM_020325014.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_343409_AA1134090 | Omega-3 fatty acid desaturase, endoplasmic reticulum-like | 2.37468 | XM_020337300.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_4AS_TGACv1_308797_AA1029560 | Expansin-A12-like | 2.50807 | XM_020306411.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1BS_TGACv1_049914_AA0164140 | tplb0043f07 | 2.57319 | AK450976.1 | Triticum aestivum L. |

| TRIAE_CS42_1DL_TGACv1_061987_AA0206950 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase 13-like | 2.63057 | XM_020325014.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_5AL_TGACv1_374914_AA1211820 | Uncharacterized LOC109761629 | 2.67513 | XM_020320447.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1DL_TGACv1_061159_AA0187430 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase 13-like | 3.07913 | XM_020325013.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

Fig. 6.

Log2 (fold change) of down- and up-regulated genes in symbiotic normal and low-irrigated plants. 1, 2, 9: nitrogen compound metabolic process, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11, 15, 19, 23, 24, 25: carbohydrate metabolic process, 4, 8: chitin binding, 5: scopolin beta-glucosidase activity, 12: transmembrane transporter activity, 13, 14, 16: l-phenylalanine catabolic process, 17: cell division, 18, 20: lipid metabolic process, 21, 22: plant-type cell wall organization

Table 10.

Induced transcripts identified in wheat cv. Chamran AMF colonized roots in normal and deficit conditions

| Gene ID | Protein name | Value_1 (D + M) | Value_2 (N + M) | Accession ID in NCBI | Source organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIAE_CS42_7AL_TGACv1_557532_AA1782680 | Mixed-linked glucan synthase 2-like | 0 | 0.38386 | XM_020308861.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1DL_TGACv1_061987_AA0206890 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase 13-like | 0 | 0.70549 | XM_020325007.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_5BL_TGACv1_405270_AA1323650 | Expansin-A31-like | 0 | 0.41256 | XM_020334430.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_7DS_TGACv1_622542_AA2041460 | Patatin-like protein 2 | 3.75019 | 0 | XM_020293126.1 | Aegilops tauschii subsp. tauschii |

| TRIAE_CS42_1AL_TGACv1_003048_AA0047290 | Germ agglutinin isolectin A | 1.21392 | 0 | M25536.1 | Wheat (T.aestivum) |

| TRIAE_CS42_3DL_TGACv1_251714_AA0884080 | WPR4b gene | 0.545005 | 0 | AJ006099.1 | Triticum aestivum |

Validation of DEGs by q-RT PCR

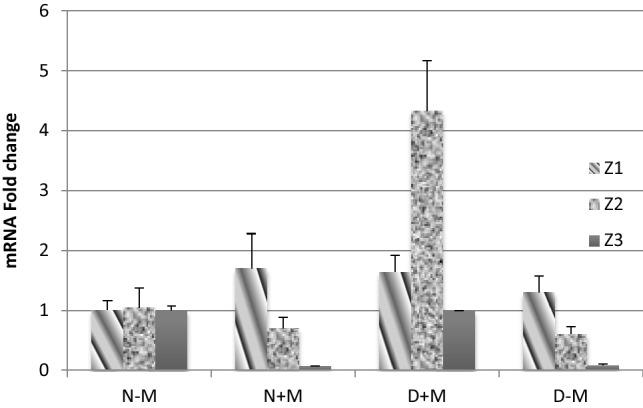

To confirm the accuracy of the result of transcriptome analysis, the expression of three randomly selected DEGs, in RNA-Seq analysis were examined by qRT-PCR (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Log 2 (fold change) of three selected genes, Z1: cellulose biosynthetic process, Z2: beta-glucosidase BoGH3B-like Z3: chitinase activity, analyzed by q-RT PCR

The genes examined with q-RT PCR represented the close expression level similar to RNA-Seq data. The selected genes were associated to cellulose biosynthetic process (XM_020345004.1), beta-glucosidase BoGH3B-like (XM_020296045.1), and chitinase activity (AY973229.1), respectively.

Discussion

Since severe soil drought significantly decrease root AMF colonization and hyphal growth in the soil, we applied a mild water stress in our experiments. The beneficial role of the symbiosis relationship concerning the tolerance to abiotic stresses is clearly revealed (Bernardo et al. 2019; Ren et al. 2019; Ouledali et al. 2019). AMF inoculation not only enhanced plant growth and yield, but also improved plant resistance against water deficit. In line with our findings, AMF improved plant growth and productivity under water stress situation (Li et al. 2019). The improvement of plant growth can be related to root system development and recuperating of water and minerals accessibility. This conclusion is in corroboration with previous findings (Nezhadahmadi et al. 2013; Li et al. 2019; Ye et al. 2019).

To discover novel genes involved in plant-AMF interaction in different conditions, whole-genome Transcriptome analysis technique was used. Moreover, applying two biological replicates per condition with 10 pooled roots per replicate for sequencing can strengthen our results. We have also considered precise criteria in order to separate differential expressed genes which have resulted in the omission of genes with low expression differences.

Interaction with arbuscular micorrhizal fungus Funneliformis mosseae, cell wall of plant root is the first line of defense which can highly protect the plant. On the other hand, in mycorrhizal symbiosis, plant root cell wall opens a way for symbiotic establishment, development and nutrient exchange (Rich et al. 2014). In the present study, we tried to connect some cell wall and membrane genes generated from RNA-Seq data set to plants growth and tolerance against water deficit in the presence or absence of AMF; since the most up- and down- regulated genes related to transferase activity and biosynthetic processes are cell membrane proteins (An et al. 2018; Vangelisti et al. 2018). Here we focused on several DEGs that were directly or indirectly involved in cell wall and membrane modulation and synthesis, and tried to make a connection between these DEGs and plant tolerance. It seems that the plant cell wall plays a significant role in stress perception through changing and remodeling the growth strategies in response to stress (Kesten et al. 2017). Furthermore, different molecules of cell wall can play a role as signaling factors to warn the plant immune system under adverse situations (Malinovsky et al. 2014). Cellulose as the major component of cell wall has considerably shown up-regulation in mycorrhizal plants. Comparing D − M/D + M, we found three genes (XM_020312442.1, XM_020331230.1, XM_020312442.1) to be only expressed in mycorrhizal treatment as mycorrhizal-induced gene (Table 8); analogously, there were three specific induced cellulose-related genes (Table 6) in N − M/N + M comparison (XM_020331230.1, XM_020312442.1, XM_020322746.1). Considering these data, it seems that mycorrhizal symbiosis can effectively increase cellulose biosynthetic process and cell growth. Interestingly, cellulose synthases and also linked microtubules can perceive stress signals directly or indirectly to trigger reproducing and remodeling the cellulose microfibrils and proteins like expansin as the best response (Kesten et al. 2017). Wang et al. (2016) have reported that cellulose deficient mutant plants are more sensitive to abiotic stress than wild-type ones (Wang et al. 2016); therefore, a stress-response related role can be considered for cellulose, since cellulose microfibrils and the other factors that lead the direction of cell growth can be regulated by water availability (Wang et al. 2016). Based on our results, increased cellulose synthesis occurs in plants in normal irrigation, and this data is content with plant growth analysis (Fig. 2); and as we observed a gene (XM_020308861.1) only expressed in N + M treatment compared to D + M (Table 10), it can be perceived that probably the better irrigation condition leads to more cellulose microfibril biosynthesis in plant cell wall, and consequently, cell growth and symbiosis establishment; thus, we can introduce this gene (XM_020308861.1) as a N + M-specific gene. Therefore, cellulose biosynthesis related genes recognized as significant expressed in mycorrhizal-alleviated plants. Our results suggest that a defense-related role can be considered for cellulose in plant cell wall, since cellulose is the most abundant component of that, and cell wall appears as a very complex network for providing protection and perception to confront critical situations (Kesten et al. 2017; Vangelisti et al. 2018; Ren et al. 2019). A possible explanation for increasing of cellulose biosynthesis might be a relevance between cellulose content increase toward raising alleviated wheat plants tolerance; referring previous studies (Balestrini and Bonfante 2014; Kesten et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2014), disordering the cellulose microfibriles organization occurred by biotic or abiotic factors, water deficit or AMF in this case, can trigger defense response in plants; Although discovering the exact mechanism requires more investigation.

Deducing from our results, lipid metabolic process associated genes such as fatty acid biosynthetic process, were up-regulated in AMF plants in comparison to non-mycorrhizal plants, especially under water deficit; comparing D − M/D + M conditions, there were three up-regulated genes related to lipid biosynthesis, and two up-regulated (FN564431.1, XM_020337300.1) and one specific gene (XM_020293126.1) related to D + M treatment in comparison with N + M. Since lipids are very important component of cell membrane, water deficiency may affect the composition and amount of lipids due to stress (Ivanov and Harrison. 2018). Increasing the lipid metabolic process due to AMF and well watering may suggest the role of lipids in maintaining the normal structure and function of cell membrane (Ivanov et al. 2019); to this aim, since AMF increases plant defense in stress situation, specially water deficit condition, it endeavors to enhance the cell membrane thickness by increased biosynthesis of lipid compartments either for forming arbuscular structures or counteracting abiotic stresses. Considering the increased lipid-related gene expression in D + M plants, we propose the role of AMF to increase the plant tolerance by targeting the cell membrane composition, which is consistent with previous reports (López-Ráez et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2014).

In addition, we identified genes related to microfibril organization and cytoskeleton structure as mycorrhizal-responsive genes. As the cytoskeletal restructuring is related to cell membrane integrity, different stresses such as water shortage can change this arrangement, membrane fluidity and transmembrane transporters activity (Vangelisti et al. 2018). It could be suggested that up-regulation of the cytoskeletal compartments related genes in symbiotic plants protect the membrane integrity and transports in response to water stress; as it has been suggested that de-polymerization and re-organization of the cytoskeletal microtubules can be important for plant tolerance to salt stress as an abiotic stress (Wang et al. 2013). It is demonstrated that mycorrhizal symbiosis can enhance the absorption of minerals in host plant (Smith et al. 2011). In agreement with these results, we found the up-regulation of genes involved in membrane transferase compartments because of mycorrhizal relationship. Genes such as ammonium transporters and integral components of membrane are presented as mycorrhizal-responsive genes (Tables 6, 8). Up-regulation of ammonium transporters in AMF roots of host plants has already been reported in some plant species (Breuillin-Sessoms et al. 2015; Hong et al. 2012; Pérez-Tienda et al. 2014). It is proposed that the presence of transporters in pre-arbuscular membrane can help arbusculated cells survival and maintenance of symbiotic relationship in root cells (Breuillin-Sessoms et al. 2015).

Moreover, several carbohydrate metabolic process related genes were identified as significant differentially expressed genes in this study and mainly related to root cell wall degradation and remodeling (Vangelisti et al. 2018); which some such as mannosidase, hexose metabolic process and β-glucosidase activity with roles in cell wall biogenesis. In comparison between D − M/N − M, there were two carbohydrate-metabolic-process related genes (Table 3) whose expression level were completely induced in control plants, and it can be associated with normal irrigation condition. Since four induced genes (XM_020321162.1, XM_020321162.1, XM_020329909.1, XM_020310973.1) related to carbohydrate metabolic process, hydrolase activity and xylan biosynthetic process were found in AMF plants (Table 8), it can be deduced that AMF could effectively improve cell behavior by changing its gene expression pattern. Amongst different roles of carbohydrates in plant cells, such as mechanical support imparted by xylan, mannan and xyloglucan in cell wall can be considered as one of their important roles (Houston et al. 2016). It seems that some carbohydrates related to the host plant are allocated to AM development, and accumulation of some carbohydrates, like monosaccharides, can improve the osmotic adjustment and water preservation of the host plant (Wu et al. 2013). It has been shown that carbohydrates play an important role in plant defense response and immunity (Lastdrager et al. 2014). Some participate as elicitors, whilst, others can imply such as phyto-hormones and signaling molecules (Trouvelot et al. 2014), or elicitors which are derived from plant cell wall during plant’s interaction with microorganisms (Boudart et al. 2003). Since water stress can directly affect the cell membrane construction, it is suggested that carbohydrates play a key role in integral redox network and mitigate the destructive effects of drought stress (Keunen et al. 2013). Chen et al. (2014) has previously reported increased the expression of monosaccharide genes like mannose and glucose in symbiotic plants. Hemicellulose, as a complex and important part of the plant cell wall is composed of mannose, glucose or xylose and reinforces the cell wall through interaction with cellulose microfibrils and lignin (Malinovsky et al. 2014). Here we can suggest a mycorrhizal-responsive role for abovementioned monosaccharide related genes which appeared as upregulated DEGs in colonized plants (Tables 5, 7). Also, AMF positively affect the plant immune system by increasing the expression of genes annotated as hemicellulose compartments, such as mannose and xylose, and fortifying the cell wall as a first barrier of plant cell.

The expression data about chitin binding and chitinase activity genes, revealed increasing pattern in presence of AMF, especially under water deficit condition. This result is consistent with Behringer et al. (2015) observation in Picea abies, and other reports demonstrating the role of chitinase enzymes in increasing plant tolerance (Couto et al. 2013; Dana et al. 2006; Hermosa et al. 2012; Lucas et al. 2014).

As fundamental molecule of fungus cell wall, chitin and chitin-derived molecules play a key role as signals to initiate defense responses in plant cells in symbiosis relationship (Shimizu et al. 2010; Hayafune et al. 2014). It could be suggested that chitin-related genes such as chitinase detect chitin molecules of fungus as a signal to trigger a proper defense response, and also increase the plant tolerance.

Cufflink assembly data indicated higher expression of lignin catabolic processes related genes. Gutjahr et al. (2015) have reported plant secondary cell wall genes such as lignin, down-regulated during symbiosis, and it might facilitate mycorrhizal fungus penetration and development through plant cell wall, and this is in agreement with our results.

Conclusion

Our analysis of significantly expressed genes in AMF roots of wheat cv. “Chamran” proposes that a primary defense response related to cell wall and membrane and also some membrane located molecules such as carbohydrates as a very significant group of molecules could be accomplished in mycorrhizal plants. These two important external parts of plant cells could initiate the first step of defense response against water deficiency through signaling processes in which different molecules of cell wall and also membrane transporters and compartments are involved. For the first time, in the present research it has been suggested that modifications and changes in cell wall components and their activities and cell-membrane-located molecules induced by AMF as an invader in the first place, may provide a tolerance-specified system in which structural part, such as cellulose and hemicellulose compartments and lipid molecules, and non-structural molecules, such as many carbohydrates, cooperate toward improving biosynthetic processes and physically strengthening of the outermost parts of the host plant which lead to plant growth improvement as well. Since there are great number of genes addressed to cell wall and membrane, understanding the exact genes and their roles, obviously needs more investigations in the future. Our results represent that symbiotic plants displayed differentially amount of expressed genes, most related to restructuring and strengthening of cell wall and membrane, and also their organization and remodeling to protect the host plant, and this tolerance response can provide more durability and better growth status for the symbiotic plants.

Finally, despite several investigations on cell wall and membrane changes in symbiotic plants and the relationship with plant tolerance to achieve a precise conclusion, this study has tried to focus on some significant genes and introduce some specific genes associated with mycorrhiza under two different irrigation regimes. Notwithstanding the delicate and extended range of water stress condition as one of the most important abiotic stresses, the relationship between cell wall and membrane genes expression pattern and the intensity and duration of water deficit can be very impressive; so the studies domain can be really vast and detailed in this case. Probably, our outcomes can highlight the advantage of transcriptome profiling to identify additional genes and the mycorrhiza-associated genes that have been found, provide a field for further investigations into cell wall-related genes and their relationship with plant tolerance.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- An J, Sun M, Velzen R, Ji C, Zheng Z, Limpens E, Bisseling T, Deng X, Xiao S, Pan Z. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Poncirus trifoliate identifies a core set of genes involved in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(21):5255–5264. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestrini R, Bonfante P. Cell wall remodeling in mycorrhizal symbiosis: a way towards biotrophism. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:237. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestrini R, Lanfranco L. Fungal and plant gene expression in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Mycorrhiza. 2006;16:509–524. doi: 10.1007/s00572-006-0069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer D, Zimmermann H, Ziegenhagen B, Liepelt S. Differential gene expression reveals candidate genes for drought stress response in Abies alba (Pinaceae) PLoS ONE. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo L, Carletti P, Badeck FW, Rizza F, Morcia C, Ghizzoni R, Ruphael Y, Colla G, Terzi V, Lucini L. Metabolomic responses triggered by arbuscular mycorrhiza enhance tolerance to water stress in wheat cultivars. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;137:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudart G, Charpentier M, Lafitte C, Martinez Y, Jauneau A, Gaulin E, Esquerré-Tugayé MT, Dumas B. Elicitor activity of a fungal endopolygalacturonase in tobacco requires a functional catalytic site and cell wall localization. Plant Physiol. 2003;131(1):93–101. doi: 10.1104/pp.011585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenchley R, Spannagl M, Pfeifer M, Barker GL, D’Amore R, Allen AM, McKenzie N, Kramer M, Kerhornou A, Bolser D, Kay S, Waite D, Trick M, Bancroft I, Gu Y, Huo N, Luo MC, Sehgal S, Gill B, Kianian S, Anderson O, Kersey P, Dvorak J, McCombie WR, Hall A, Mayer KF, Edwards KJ, Bevan MW, Hall N. Analysis of the bread wheat genome using whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Nature. 2012;491(7426):705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature11650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuillin-Sessoms F, Floss DS, Gomez SK, Pumplin N, Ding Y, Levesque-Tremblay V, Noar RD, Daniels DA, Bravo A, Eaglesham JB, Benedito VA, Udvardi MK, Harrison MJ. Suppression of arbuscule degeneration in Medicago truncatula phosphate transporter4 mutants is dependent on the ammonium transporter 2 family protein AMT2;3. Plant Cell. 2015;27(4):1352–1366. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.131144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Xiaoying, Song Fengbin, Liu Fulai, Tian Chunjie, Liu Shengqun, Xu Hongwen, Zhu Xiancan. Effect of Different Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Growth and Physiology of Maize at Ambient and Low Temperature Regimes. The Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2014/956141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavijo BJ, Venturini L, Schudoma C, Accinelli GG, Kaithakottil G, Wright J, et al. An improved assembly and annotation of the allohexaploid wheat genome identifies complete families of agronomic genes and provides genomic evidence for chromosomal translocations. Genome Res. 2017;27:885–896. doi: 10.1101/gr.217117.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto M, Lovato P, Wipf D, Dumas-Gaudot E. Proteomic studies of arbuscular mycorrhizal associations. Adv Biol Chem. 2013;3:48–58. doi: 10.4236/abc.2013.31007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dana MM, Pintor-Toro JA, Cubero B. Transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing chitinases of fungal origin show enhanced resistance to biotic and abiotic stress agents. Plant Physiol. 2006;142(2):722–730. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong CH, Li C, Yan XH, Huang SM, Huang JY, Wang LJ, Guo RX, Lu GY, Zhang XK, Fang XP, Wei WH. Gene expression profiling of Sinapis alba leaves under drought stress and rewatering growth conditions with Illumina deep sequencing. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(5):5851–5857. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essahibi A, Benhiba L, Babram MA, Ghoulam C, Qaddoury A. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the functional mechanisms associated with drought tolerance in carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) Trees. 2018;32:87–97. doi: 10.1007/s00468-017-1613-84. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia K, Chasman D, Roy S, Ané JM. Physiological responses and gene co-expression network of mycorrhizal roots under K + deprivation. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:1811–1823. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill BS, Appels R, Botha-Oberholster AM, Buell CR, Bennetzen JL, Chalhoub B, Chumley F, Dvorák J, Iwanaga M, Keller B, Li W, McCombie WR, Ogihara Y, Quetier F, Sasaki T. A workshop report on wheat genome sequencing: international genome research on wheat consortium. Genetics. 2004;168(2):1087–1096. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guether M, Balestrini R, Hannah M, He J, Udvardi MK, Bonfante P. Genome-wide reprogramming of regulatory networks, transport, cell wall and membrane biogenesis during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in Lotusjaponicus. New Phytol. 2009;182(1):200–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutjahr C, Sawers RJH, Marti G, Andrés-Hernández L, Yang SY, Casieri L, et al. Transcriptome diversity among rice root types during asymbiosis and interaction with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:6754–6759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504142112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayafune M, Berisio R, Marchetti R, Silipo A, Kayama M, Desaki Y, Arima S, Squeglia F, Ruggiero A, Tokuyasu K, Molinaro A, Kaku H, Shibuya N. Chitin-induced activation of immune signaling by the rice receptor CEBiP relies on a unique sandwich-type dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(3):404–413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312099111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermosa R, Viterbo A, Chet I, Monte E. Plant-beneficial effects of Trichoderma and of its genes. Microbiology. 2012;158(1):17–25. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.052274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JJ, Park YS, Bravo A, Bhattarai KK, Daniels DA, Harrison MJ. Diversity of morphology and function in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses in Brachypodium distachyon. Planta. 2012;236:851–865. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston K, Tucker MR, Chowdhury J, Shirley N, Little A. The plant cell wall: a complex and dynamic structure as revealed by the responses of genes under stress conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:984. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov S, Harrison MJ. Accumulation of phosphoinositides in distinct regions of the periarbuscular membrane. New Phytol. 2018;221(4):2213–2227. doi: 10.1111/nph.15553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov S, Austin J, Berg RH, Harrison MJ. Extensive membrane systems at the host-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus interface. Nat Plants. 2019;5:194–203. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacott CN, Murray JD, Ridout CJ. Trade-offs in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: disease resistance, growth responses and perspectives for crop breeding. Agronomy. 2017;7(4):75. doi: 10.3390/agronomy7040075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasena AS, Secco D, Bernath-Levin K, Berkowitz O, Whelan J, Mylne JS. Next generation sequencing and de novo transcriptomics to study gene evolution. Plant Methods. 2014;10(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-10-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesten C, Menna A, Sánchez-Rodríguez C. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in response to stress. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;40:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keunen E, Peshev D, Vangronsveld J, Van Dem Ende W, Cuypers A. Plant sugars are crucial players in the oxidative challenge during abiotic stress: extending the traditional concept. Plant, Cell Environ. 2013;36:1242–1255. doi: 10.1111/pce.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastdrager J, Hanson J, Smeekens S. Sugar signals and the control of plant growth and development. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(3):799–807. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Wang R, Tian H, Gao Y. Transcriptome responses in wheat roots to colonization by the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis. Mycorrhiza. 2018;28:747. doi: 10.1007/s00572-018-0868-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Meng B, Chai H, Yang X, Song W, Li S, Lu A, Zhang T, Sun W. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi alleviate drought stress in C3 (Leymus chinensis) and C4 (Hemarthria altissima) grasses via altering antioxidant enzyme activities and photosynthesis. Front Plant Sci. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Ráez JA, Verhage A, Fernández I, García JM, Azcón-Aguilar C, Flors V, Pozo MJ. Hormonal and transcriptional profiles highlight common and differential host responses to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and the regulation of the oxylipin pathway. J Exp Bot. 2010;61(10):2589–2601. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas SJ, Akpınar BA, Šimková H, Kubaláková M, Doležel J, Budak H. Next-generation sequencing of flow-sorted wheat chromosome 5D reveals lineage-specific translocations and widespread gene duplications. BMC Genom. 2014;15:1080. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinovsky FG, Fangel JU, Willats WG. The role of the cell wall in plant immunity. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:178. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigle TP, Miller MH, Evans DG, Fairchild GL, Swan JA. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular—arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 1990;115(3):495–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1990.tb00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]