Short abstract

Aims

Chronic diseases may affect sexual health as an important factor for well-being. Mobile health (m-health) interventions have the potential to improve sexual health in patients with chronic conditions. The aim of this systematic review was to summarise the published evidence on mobile interventions for sexual health in adults with chronic diseases.

Methods

Five electronic databases were searched for English language peer-reviewed literature from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2019. Appropriate keywords were identified based on the study’s aim. Study selection was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis statement. The full texts of potential studies were reviewed, and final studies were selected. The m-health evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist was used to assess the quality of the selected studies. After data extraction from the studies, data analysis was conducted.

Results

Nine studies met the inclusion criteria. All interventions were delivered through websites, and a positive effect on sexual problems was reported. Prostate and breast cancer were considered in most studies. Interventions were delivered for therapy, self-help and consultation purposes. Quality assessment of studies revealed an acceptable quality of reporting and methodological criteria in the selected studies. Replicability, security, cost assessment and conceptual adaptability were the criteria that had not been considered in any of the reviewed studies.

Conclusions

Reviewed studies showed a positive effect of mobile interventions on sexual health outcomes in chronic patients. For more effective interventions, researchers should design web-based interventions based on users’ needs and consider the m-health essential criteria provided by mERA. Additionally, mobile interventions can be more effective in combination with smartphone apps.

Keywords: Sexual health, Internet, m-health, telemedicine, chronic disease

Introduction

Sexuality is an important factor for interpersonal connections and is associated with both positive mental and physical health outcomes.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being related to sexuality throughout the lifespan.2 Psychosocial and physiological factors can affect biological systems and result in sexual health problems among men and women.3 Chronic diseases as physiological factors and hence the treatment of such conditions may have serious effects on sexual functioning.4 For instance, female sexual dysfunction (SD) and decreased sexual desire are very common after breast cancer treatment.5,6 Treatment and control of SD in patients with chronic diseases must be considered in order to improve quality of life. However, assessing sexual function and discussing sexual problems with a clinician in clinic is limited due to the embarrassment or shame of people with sexual problems. This may be limiting treatment-seeking behaviour among patients.7–9 The easily administered and interpreted tools that are available to assess and manage sexual problems could improve people’s sexual health.9

Other than pharmacotherapy, psychological interventions including assessing sexual function, behavioural therapy and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) are the best-known approaches to address the behavioural, cognitive, affective and attitudinal aspects of sexual problems.8

There is growing evidence that Internet-based CBT is an effective method of treatment for a variety of psychological problems, including SD.4 Mobile health (m-health) is defined as ‘the use of mobile, internet and wireless technologies to deliver healthcare services regardless of geographical, temporal, and even organizational barriers’. It has a strong impact on typical health-care services10,11 and can be an alternative treatment approach for clinical sexual problems.8,12,13 M-health interventions provide convenience, privacy, anonymity and more interactive treatment for SD and are suitable tools for people who are too embarrassed or anxious to discuss their SD with a clinician.8,12,13

Some review studies have reported various digital and mobile interventions for sexual health promotion in adults and adolescents. Interventions that have been considered in these reviews include interactive digital interventions, serious digital games, short message service (SMS), mobile apps and social media.14–21 While the use of Internet therapy as a potential treatment for SD has frequently been advocated,13 as far as we know, there have been no systematic reviews that primarily include m-health interventions when addressing sexual health problems in adults with chronic diseases.

This systematic review summarises the published evidence on the effectiveness of m-health interventions in sexual health outcomes in adults (i.e. those aged ≥19 years) with chronic disease, as well as the reported quality, study design, methodology and technical features of such interventions. This research was designed to answer the following questions. (a) What are the m-health interventions for the management of SD among adults with chronic diseases? (b) What are the contents and technical characteristics of these interventions? (c) Have these interventions been effective in sexual health outcomes?

In this study, we defined SD as difficulty experienced by an individual or a couple during any stage of normal sexual activity, including physical pleasure, desire, preference, arousal or orgasm.

Methods

To conduct and report this systematic review, we followed the procedures described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement.22

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for study selection were defined based on the Patient and Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study design) as follows:

Population: individuals aged ≥19 years with a history of any type of chronic disease and a diagnosis of SD who were in a heterosexual relationship.

Intervention: m-health interventions, including apps, websites, SMS and other mobile technologies.

Comparator: usual sexual outcomes (behavioural, psychological, knowledge and attitude).

Outcome: primary outcomes of interest, including clinical outcomes, psychological outcomes behavioural outcomes and sexual knowledge or attitude; other outcomes of interest identified during the literature review were included.

Study design: we did not apply any restrictions on the type of studies.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if (a) measured outcomes were within the domains of sexually transmitted infections, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, violence, antenatal care or postnatal care; (b) the population was in sexual minority group (e.g. transgender, genderqueer, intersex, etc.); (c) the intervention was delivered via other information and communication technologies (e.g. personal computers, games, etc.); (d) interventions were delivered through the Internet but not a developed website or programme (e.g. blogs, social networks, email only, etc.); or (e) the paper was a review, commentary, meeting or conference paper or grey literature.

Information sources

Five electronic databases in the field of medicine and social sciences, including Medline (through PubMed), Embase, Web of sciences (core collection), Scopus and PsycINFO (through Proquest), were searched. We restricted our searches to English-language peer-reviewed literature from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2019. We also examined the reference lists of identified articles to find studies that did not initially appear in our search.

Search strategy

Regardless of inclusion criteria, we defined our search strategy to be purposefully broad in order to ensure that we captured all relevant articles. Search terms were grouped into three conceptual categories: sexual health and problems, mobile technology and the application of the interventions. For each concept, appropriate keywords were defined based on the aim of the study and inclusion criteria. Due to the diversity of chronic problems, the keywords related to chronic diseases were not defined. Alternatively, we selected all sexual problems and then included only those related to chronic diseases. To develop a sensitive search strategy, we joined the defined terms and database-specific indexing terms (MeSH in PubMed and Emtree in Embase) whenever possible, and supplemented them with other words and phrases as needed (see Online Appendix 1). The final search strategy was made by combining the keywords with the ‘OR’ Boolean operator in each concept and with the ‘AND’ operator between concepts. The search strategy was modified specifically for every database based on their guide (see Online Appendix 2).

Study selection

The search results of selected databases were imported into the EndNote citation manager software, and the duplicates were removed. Two reviewers independently scanned titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria. Each study was marked as relevant or irrelevant. An article was excluded if marked as irrelevant by both reviewers. The full texts of the remaining studies were reviewed separately by each reviewer, and the final eligible studies were determined and included. Any disagreements were discussed between reviewers, and two other authors were involved to help reach a consensus when necessary. We also excluded studies if they reported the same intervention in different study designs. The PRISMA flow diagram was used to document the search strategy and article selection process.

Data collection process and quality assessment

The data of interest and the basic characteristics of the selected studies, including the name of the intervention, the population, the aim of the intervention, the study design, the outcomes and the key technical features of the intervention, were extracted using a standardised sheet, which was designed and piloted by the reviewers.

The study design, the primary outcome and the application of the intervention were used as classification schemes for synthesising the data. We categorised the application of the interventions into five classes: self-assessment, self-help, education, consultation and treatment. The primary outcomes were categorised into the following groups: clinical, psychological, behavioural, sexual knowledge and attitude, skills and self-efficacy. One reviewer extracted data from the selected studies, and a second reviewer independently confirmed the accuracy.

To assess the quality of studies, evidence was graded using the m-health evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist,23 a checklist that consists of 16 core items focusing on the reporting of m-health interventions by addressing their content, context and implementation features.

Data synthesis and analysis

An overview of the basic characteristics of the studies was summarised in a table. Data were not combined because of differences in the main outcome measures and populations of the studies. All research findings were classified according to review objectives.

Results

Study selections

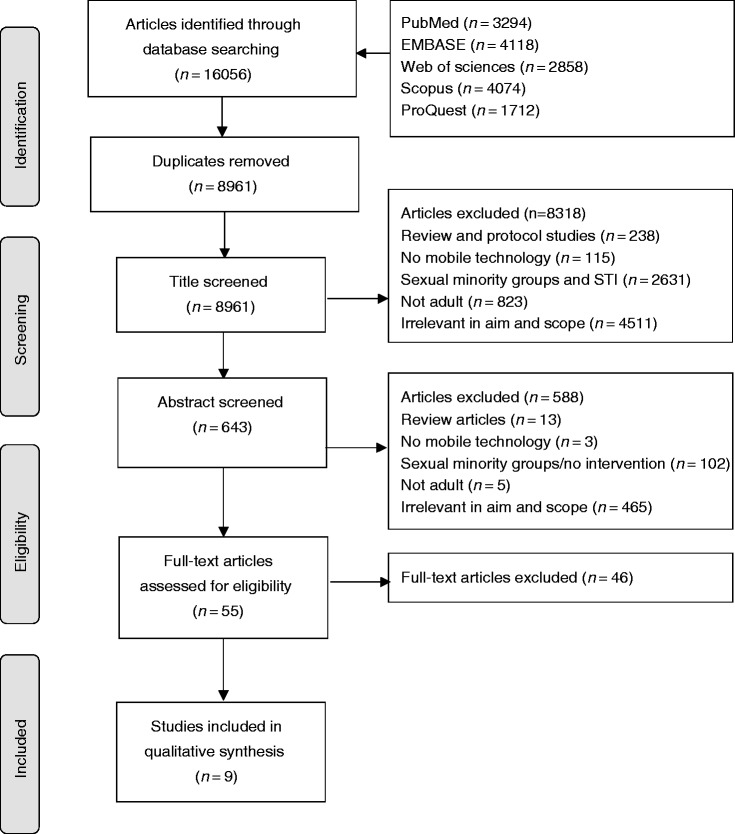

The online search resulted in 8961 unique articles being identified. Screening of the titles and abstracts rendered 55 articles for full-text review. A total of 45 articles were excluded at full-text screening. No new relevant studies were found by examining the reference lists of the identified studies. Finally, nine studies that reported m-health interventions for improving sexual health of chronic disease survivors were included in this study. The process of study selection is shown in a PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram of study selection.

Study characteristics

The publication year of the studies ranged from 2011 to 2018. Only one study was found from 2019.24 The intervention in this study was reported in four different manuscripts by different study designs between 2015 to 2019.4,24–26 However, we included only one study from this author.4

Three (36%) studies were conducted in the USA,6,27,28 two (22%) in Sweden,29,30 one (11%) in Canada31 and one (11%) in both the USA and Canada.32 Other studies were conducted in Australia,33 the Netherlands4 and Belgium.3

The age of participants in the reviewed studies ranged from 18 to 82 years (Table 1). Participants of the studies were female,28,31 male,33 both sexes29,30 and couples.27,32,34 The chronic disease or condition of the participants included breast cancer,4,34 gynaecological cancer,31 prostate cancer,32,33 colorectal cancer32 and other types of cancer29,30 (Table 1). The setting of the studies included a mental health organisation in the Netherlands,4 nationwide programmes in Australia and Sweden,30,33 a university cancer centre in the USA,6,27,28 gynaecological oncology clinics, outpatient clinics and a tertiary care cancer centre in Canada,31 a cancer agency, cancer centre and a cancer programme at a hospital in the USA and Canada,3 hospitals in Belgium,34 and a hospital university in Sweden.29

Table 1.

Study characteristics and results of web-based interventions for sexual health.

| Author and year | Study design | Population | Chronic disease or condition | Study objective | Primary outcomes | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiljer (2011)31 | Pilot test; FU: NS | Canada; female; Mage=45.4 years; N=27 | Gynaecological cancer | To pilot test a web-based support group for women with psychosexual distress due to gynaecological cancer (whether benefits similar to the ones found in a breast cancer support group will be found for gynaecological cancer patients) | NS | Women reported benefits to participating in the intervention, including receiving support from group members and moderators, increased emotional well-being, improved feelings of body image and sexuality and comfort in discussing sexuality online |

| Schover (2012)27 | RCT; FU: 3, 6 and 12 months | USA; couples; Mage=64 years; N=234 | Localised prostate cancer | Hypotheses: (a) the two formats (face-to-face and Internet-based) of the intervention would have equal efficacy; (b) outcomes would be superior to those after a three-month waitlist control condition | The total score on the IIEF (a 15-item assessment of sexual function and satisfaction for men), the total score on the FSFI (a similar questionnaire for women), BSI-18 (assessed current distress), and Dyadic Adjustment Scale (measured relationship satisfaction); in the web groups, the duration, number and content of visits were recorded electronically | IIEF total scores improved significantly over time in all intervention groups and improved significantly on orgasmic function (p=0.001), intercourse satisfaction (p<0.0001) and overall sexual satisfaction (p<0.0001); only sexual desire scores remained stable |

| Pawels (2012)34 | Development and process evaluation; FU: NS | Belgium; females and their husbands; Mage=52 years; N=202 | Breast cancer | To assess whether tailoring of online information to the key needs of breast cancer survivors and partners is evaluated as positively by survivors and partners as a website that is tailored to their sociodemographic and medical characteristics | Content and layout of the tailored website: to what extent the website was user friendly, well built, interesting, informative, understandable, new, incomplete, irrelevant, unreliable, too extensive and confusing; opinions about the website’s topics, use of colours, images, the ability to select information of relevance and links to other websites | Survivors’ and partners’ total time spent on the website was on average 32 minutes and 19 minutes, respectively. The average frequency of visiting the website was 1.71 times for survivors and 1.38 times for partnersOn the survivor part of the website, the breast cancer and physical consequences menus were visited most frequently and for the longest amount of time, and the psychological and social consequences menus were consulted leastOn average, most time was spent by partners on the supporting my partner menu (nearly 14 minutes) |

| Schover (2013)6 | RCT; FU: 3 and 6 months | USA; females and their husbands; Mage=53 years; N=72 | Localised breast or gynaecological cancer | To create a web site and test a prototype in a randomised trial comparing use on a self-help basis or supplemented with sexual counselling for women after cancer | FSFI, MSIQ, BSI-18, QLACS | Significant improvement on the FSFI (p<0.001), MSIQ (p<0.001) and QLACS total score (p<0.001). |

| Winterling (2016)29 | Intervention development | Sweden; Females and males; age: 16–40 years | Any cancer types | To describe the development of a web-based intervention in long-term collaboration with patient research partners | Patient Research Partners on Service Quality and System Quality, overall impact of Patient Research Partners on the research project | NS |

| Wootten (2017)33 | RCT; FU: 3 and 6 months | Australia; Male; Mage=61 years; N=142 | Localised prostate cancer | To determine whether this intervention provided benefit for participants in terms of their sexual satisfaction | Overall sexual satisfaction | Significant improvement in erectile dysfunctionAssessments of sexual and masculine self‐esteem outcomes showed that only in the case of overall sexual satisfaction was there a significant difference between the groups in terms of the change from baseline to post-treatment (p=0.007) |

| Hummel (2017)4 | RCT; FU: 3 and 9 months | Netherlands; females and their husbands; Mage=51.1 years; N=187 | Breast cancer | To investigate the efficacy of Internet-based cognitive–behavioural therapy in improving sexual functioning in breast cancer survivors | Sociodemographic and basic clinical information, sexual functioning, sexual relationship intimacy | Significant improvement in in overall sexual functioning (ES=0.43), sexual desire (ES=0.48), sexual pleasure (ES=0.32) sexual arousal (ES=0.50) and vaginal lubrication (ES=0.46); also significantly greater decrease in sexual distress (ES=0.59) and discomfort during sex (ES=0.66).Secondary outcomes: Significant decrease in menopausal symptoms (ES=0.39), improvement in body image (ES=0.45) and marital sexual satisfaction |

| Brotto (2017)32 | RCT; FU: 6 months | USA and Canada; female and males; Mage=59 years (female), 55 years (males); N=113 | Colorectal and gynaecological cancer | To adapt this face-to-face intervention for online delivery, given that online treatments are able to overcome some of the emotional and geographic barriers | Primary outcome: sex-related distress – the 12-item Female Sexual Distress Scale | Women had significant improvements in sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasmic function, sexual satisfaction and overall sexual function, as well as a decrease in genital painMen showed a significant improvement in intercourse satisfaction and a marginally significant increase in sexual desire. |

| Wiklander (2017)30 | Feasibility study | Sweden; females and males; age: 18–43 years | Breast, cervical, ovarian, testicular, central nervous system or lymphoma cancers | Part of the Fertility and Sexuality Following Cancer (Fex-Can) research project, aiming to investigate and treat sexual problems and fertility distress among adults with cancer | Feasibility testing was evaluated in terms of: demand (use of the intervention), acceptability (the relevance and adequacy of the content, layout, and language), preliminary efficacy (perceived increase in knowledge and improved skills) or handling sexual problems or fertility distress) and functionality (technical functioning, organisation and usability) | Of participants who started the fertility programme, all rated high levels of distress on at least one of the RCAC subscales. |

FU: follow-up; NS: not specified; RCT: randomised controlled trial; FSFI: Female Sexual Function Index; MSIQ: Menopausal Sexual Interest Questionnaire; QLACS: Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors; IIEF: International index of erectile function; BSI-18: Brief Symptom Inventory-18; ES: effect size; RCAC: Revisiting the Reproductive Concerns After Cancer.

The study design was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in five studies4,6,27,32,33 while others were designed as pilot test,28,31 intervention development29,34 and feasibility study.30

The follow-up duration of the studies ranged from 3 to 12 months. The attrition rate ranged from 1.89%30 to 91.2%.34 The main objectives or applications of the studies were treatment,4,28,32,33 consultation27,31 and self-help6,29,30,34 (Table 1).

We assigned all primary outcomes of the studies into clinical, psychological and behavioural categories (Table 1). Menopausal symptoms,6 female sexual function,4,6 sexual activity,4 sexual function,27 female sexual distress,4 sex-related distress,32 relationship intimacy,4 sexual satisfaction,27,33 current distress,27 relationship satisfaction,27 feelings about body image and sexuality,31 baseline sexual knowledge32 and quality of life in adult cancer survivors6,31 were defined as primary outcome measures in the reviewed studies.

Intervention characteristics

The application of four interventions was sexual therapy.4,27,28,32,33 Other interventions were an informative website and discussion forum for consultation and self-help6,29,30,34 and support group.31 Online moderate discussion, online chat group, video communication with experts and self-assessment of skills and attitudes were technical features of some interventions.6,29–33 Four interventions were also customisable4,27,29,33,34 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Technical characteristics of interventions.

| Author and year | Intervention name | Application | Intervention delivery | Intervention duration | Features of intervention | Theoretical framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiljer (2011)31 | GyneGals | Consultation | Website | 12 weeks | Live chat | Supportive–expressive group therapy model |

| Schover (2012)27 | Counseling About Regaining Erections and Sexual Satisfaction (CAREss) | Consultation | Website, contacted by email/telephone | 12 weeks | Telephone reminders, assessment questionnaires | Cognitive–behavioural therapy model |

| Pawels (2012)34 | OncoWijzer | Informative website | Websites, contacted by telephone | 10–12 weeks | Information provided according to individual visitors’ needs. (customisable) | NS |

| Schover (2013)6 | Tendrils, Sexual Renewal for Women after Cancer | Self-help | Website | 12 weeks | Video features | NS |

| Winterling (2016)29 | The Fertility and Sexuality Following Cancer (Fex-Can) | Self-help | Website, contacted by telephone | 12 weeks | Discussion forum | Key components for Internet interventions defined by Barak,35 which is a combination of education and behaviour Change content, multimedia, interactive online activities, and partial feedback support |

| Wootten (2017)33 | My Road Ahead | Self-help | Website, contacted by email | 10 weeks | Two moderated online forums | Cognitive–behavioural therapy model |

| Hummel (2017)4 | NSa | Therapy | Website, contacted by email/telephone | 20 weekly sessions | Customisable | Cognitive–behavioural therapy model |

| Brotto (2017)32 | Psychoeducational Intervention for Sexual Health in Cancer Survivors (OPES) | Unidirectional psychoeducational intervention | Website | 12 weeks | Reminder e-mails and telephone calls, internet forum, | Mindfulness-based cognitive behavioural intervention |

| Wiklander (2017)30 | The Fertility and Sexuality Following Cancer (Fex-Can) | Self-help | Password-protected website, contacted by telephone | 2 months | Discussion forum |

The CBT model was used as the logic model and theoretical framework in three studies.4,27,33 A mindfulness-based cognitive–behavioural intervention was used in another intervention.32 The Internet intervention was based on the key components defined by Barak35 in two studies.29,30 One study used the supportive–expressive group therapy model for its online support group31 (Table 2).

Effectiveness of interventions

Because of the heterogeneity in the study design and outcome measures, we were not able to conduct a meta-analysis. However, all studies reported a significant positive effect of web-based interventions on adults’ sexual outcomes (Table 1).

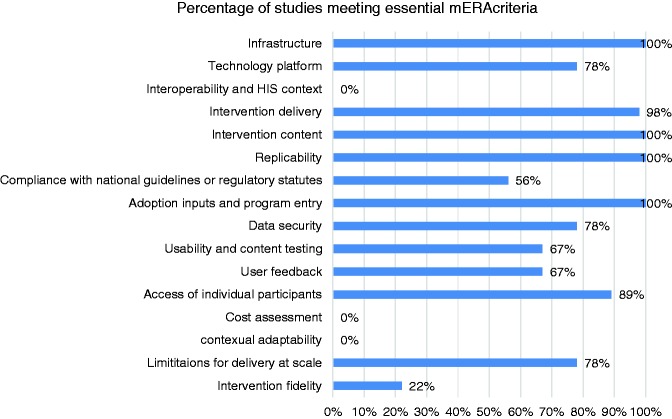

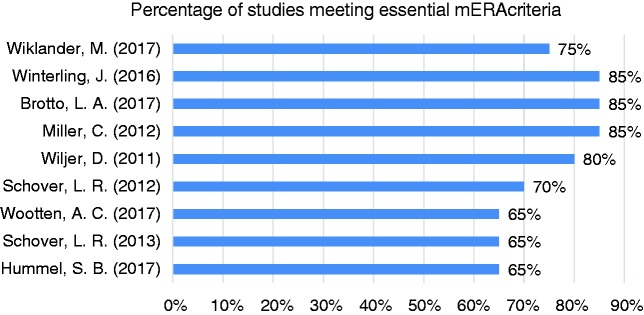

Assessment of m-health essential quality

Of 16 essential criteria defined by mERA for m-health, 12 (75%) were met by 50–100% of the included studies (Figure 2). In another view, all reviewed studies met 65–85% of the m-health essential criteria (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Percentage of studies that met m-health evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) essential criteria.

Figure 3.

Percentage of mERA criteria met by the studies.

Regarding the availability of infrastructure to support technology operations in the study location, two studies only considered Internet access as the main infrastructure.4,6 Three studies did not consider any necessary infrastructures for the intervention.29,31,33 All studies developed interventions in the form of a website. Of these, five studies designed password-protected websites.6,27,30,32,34 E-mail,4 asynchronous chat and online chat groups,12,36 phone and video conference36 and discussion forums6 were other modes of intervention delivery. Duration of intervention delivery varied from 10 weeks to five months, and users would use the intervention every day or weekly, based on the intervention design (Table 2). Only three studies described the hardware used, which included computer, tablet, mobile and laptop.27,29,30 None of the reviewed studies described how the intervention could integrate into the existing health information systems.

All studies partially described the content of the intervention. Four studies used basic information.29,31–33 Detailed information on some web-page content and tools was reported by three.6,30,34 One study4 used published guidelines for CBT for SD, and two29,30 created the features of the intervention based on the key components for Internet interventions.35

No study clearly described formative research. However, content and usability testing with target groups were described in most cases. One study mentioned some results of usability testing.6 The interview process was mentioned in another study.31 The evaluation of the content and layout using a post questionnaire was discussed in another study,34 programme acceptability was measured through semi-structured interviews32 and the content quality was discussed in meetings with participant research partners.29 In one study, the feasibility was evaluated in terms of four aspects (demand, acceptability, preliminary efficacy and functionality).30 From the nine studies reviewed, seven described user feedback about the intervention.27,29–34 Two studies recorded and calculated page view data.27,33 One study collected data from both the website tracking system and an online post questionnaire.34 One study gathered the data through semi-structured interviews.31 In one study, an online questionnaire together with interview sessions were used for collecting feedback.32 System quality was discussed in group meetings in one study.29 Finally, one study reported using website system data, telephone interviews, continuous online evaluations and study-specific measures for gathering feedback from users.30 These studies reported positive evaluations of participating in the m-health intervention for sexual problems, and the majority of the participants (75–97%) were satisfied with the interventions.36,37

Only two studies provided instructional approaches for end users of the intervention by the deployment of clinical experts.4,31 Providing information via email was another method mentioned in another study30 to educate users about how to use the intervention.

The appropriateness of the intervention and any possible adaptation strategies used to assess the fidelity of the intervention and a cost assessment of the web-based intervention were not considered in any of the studies. Furthermore, no study presented adequate technical and content details to support replicability. Considering data security of the interventions, some studies used password-protected websites.6,27,32,34 However, no study explained any hardware, software or procedural steps taken to minimise the risk of data loss or data capture.

Five studies4,30–32,34 mentioned barriers and facilitators to the adoption of the intervention among study participants. Competing priorities, fatigue and the strain of reading materials on a computer screen,31 not being acquainted with the Internet,34 lack of computer and Internet access32 and use of a specific language30 were barriers to the applicability of web-based interventions reported in studies. Facilitators to the adoption of such interventions included: having the programme guided by a personal psychologist or sexologist,4 employing clinical psychologists with expertise in facilitating psycho-oncology and sexuality groups,31 using post and email service for sending information30,34 and discussing the forms for collaboration between researchers and patient research participants during an initial meeting.30

Discussion

There are a considerable number of studies exploring the effects of m-health interventions on sexual health problems. However, among the 7829 retrieved articles, only nine met our inclusion criteria. This demonstrates that m-health interventions addressing sexual problems for patients with chronic diseases have not been considered sufficiently over the last 10 years. Although various chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, inflammatory bowel disease and so on can affect sexual functioning,38–40 reviewed studies mostly considered breast or prostate cancer for female or male patients, respectively, indicating that more research is needed for the evaluation of m-health interventions aiming at sexual health improvement in patients with other chronic disease and considering other types of cancer as well.

Since the relationship factors may affect sexual functioning, sexual health interventions should be designed separately for those who are single and those who are cohabiting. On the other hand, whenever an intervention is designed for those in a sexual relationship, it is important that both members of the couple be involved in the intervention.41 One of the positive aspects of the selected studies was taking the partners of patients involved in the studies into consideration. In some studies, involvement of the partners was desirable but not mandatory. However, sexual function and both partners’ relationship satisfaction are important prognostic factors for the success of sexual rehabilitation.27

The applications of reviewed interventions were therapy, consultation and self-help. M-health interventions can be used for sexual education, self-management, self-assessment and so on.42 Education is a remarkable factor in sexual health promotion, especially for the prevention of high-risk sexual behaviors.43 The utilisation of m-health for patient education can lead to better sexual health outcomes through improving patient knowledge and involving them in sexual decisions.42 Future research is needed to identify the impact of mobile interventions on sexual health education for patients with chronic diseases.

The selected studies measured sexual functioning and satisfaction outcomes. In order to make sure that mobile interventions are effective in sexual health promotion for patients with chronic disease, sexual health knowledge, self-efficacy, intention, motivation and biological outcomes should be considered in future studies.44

M-health devices include smartphones, wearable activity trackers, wirelessly connected scales and so on that send and receive health data through the Internet or local networks.45 We explored m-health interventions for sexual health improvement but did not find any interventions delivered through smartphones or other devices. One reason might be that such interventions have been designed but not reported. Additionally, the platform of all included interventions was web applications delivered through websites, despite smartphone apps being increasingly used for health prevention and care.18,20,46 Given that mobile phones have improved Internet access and the capacity to perform more advanced computer functions, web-based interventions may be more effective if delivered in combination with smartphone apps.47 Our results showed insufficient consideration of customisable interventions. Providing information and services to each individual based on personal data related to a given health outcome can be more effective than presenting global information.48

Regardless of the study design, m-health interventions will not be effective if users do not adopt and continue to use them.45 It is not possible to measure the impact of various features on the adoption of interventions directly, but understanding the reasons for attrition leads to reliable user-friendly interventions.49 Our findings highlight the importance of exploring users’ needs, their preferences for sexual health and features associated with system usability14 and user-friendliness by researchers and system developers so that better adoption and adherence to web-based sexual health interventions will be supported.

Some interventions provide online discussion features for patient–clinician communication. Online communication tools such as online discussion forums and online chat groups are effective in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms in individuals with depression and breast cancer.50 Self-disclosure, learning from others’ experiences and providing guidance are the advantages of online communication tools that can be used to enhance the cognitive aspects of web-based sexual health interventions.3

Some of the reviewed studies did not consider the logic model or theoretical frameworks. Interventions will be more effective if they are designed based on the theory and evidence. Additionally, the design of interventions is frequently not well described in studies, which makes it difficult to replicate interventions. As a result, designers of future interventions find it hard to discriminate effective and ineffective aspects. Thus, researchers should describe the content and development process of intervention in detail, since this helps other researchers to understand how and why the interventions work and thus facilitates the evaluation of the intervention.51

This study found that using m-health interventions may help reduce sexual health problems among patients with chronic diseases. The findings of this review are in line with other systematic reviews that have been performed in m-health interventions for the promotion of sexual health, which showed that the use of digital interventions has the potential to improve sexual health outcomes among people with sexual difficulties.15,16,20,44,52,53,54

Due to the diversity in the design of the reviewed studies, we did not assess the risk of study bias. To assess the quality of the m-health interventions, the mERA checklist23 for m-health essential criteria was used. Although CONSORT-EHEALTH11 can also be used to evaluate the validity and applicability of web-based intervention trials, we prefer the mERA checklist, since it provides guidance for developing complete and transparent reports on studies that evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of m-health interventions, while CONSORT-EHEALTH does not provide any recommendations for reporting the technical details, feasibility and sustainability of the intervention strategies.

The findings of this systematic review revealed that the quality of the reviewed studies based on m-health essential criteria was fair. Reporting on m-health interventions is new,23 and m-health reporting tools such as mERA have been available in recent years for complete and transparent reporting on m-health intervention research. More reliance on the utilisation of the mERA checklist would provide better reporting and an improved ability to synthesise the evidence on m-health interventions.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review exploring the effectiveness and quality of m-health interventions targeting sexual health promotion for adults with chronic diseases. The findings of this review helped to identify the gaps in the sexual health interventions delivered via mobile technology. It might be a useful roadmap to guide further studies on the use of mobile interventions for sexual health promotion.

To analyse a comprehensive set of m-health interventions, we included studies with diverse study designs. The benefit of this search strategy was that a larger sample size of published m-health interventions was obtained, and therefore the focus was on the recently developed interventions. However, all of the included studies were conducted as RCT.

Nevertheless, there were some methodological limitations to this study. First, we did not include studies published in languages other than English, which increases the likelihood that relevant studies were missed. Second, due to resource and time constraints, we searched only five electronic databases. Searching more databases, such as the Cochrane library or IEEE Xplore, may affect the results. Third, since positive outcome effects are more likely to be published than non-significant or negative ones, selective outcome reporting or publication bias was inevitable. Finally, we included and analysed all types of studies, regardless of their quality. Although it is often helpful to have more recent findings, low-quality studies present more inconclusive data, which affect the results.

This review is part of a main study which aimed to design a m-health intervention for the management and support of sexual health problem among heterosexual adults with usual sexual relationships. We excluded minority sexual groups because their difficulties differ from heterosexuals, and the care and management procedure for sexual problems regarding chronic diseases of this group is complex. Obviously, if we included minority sexual groups, the results of this review might have been different. However, this issue can be considered separately in other studies.

Recommendations for future studies

Whilst the results of the included studies were mostly positive, we were unable to identify effective structures and strategies of mobile interventions due to poor reporting quality and heterogeneity of the interventions as a result of small sample sizes or contamination effects. The quality of interventions is acceptable based on the mERA essential criteria checklist. Yet, it is recommended that future studies consider some m-health essential criteria discussed in this systematic review. Following the privacy concerns about sexual health issues, ethical aspects of interventions should be considered in system development.21 The reviewed studies focused on sexual health for individuals dealing with cancer of any type, even though other chronic diseases can affect sexual functionality as well.26,32,33 Thus, future studies need to assess the effectiveness of m-health interventions for patients suffering with other chronic diseases such as diabetes, dementia and so on. The review and assessment of m-health interventions for improving sexual health in sexual minority groups suffering from chronic illnesses is another recommendation for future studies.

Conclusion

This systematic review shows that mobile interventions are effective in the improvement of sexual health outcomes in adults with chronic diseases. However, the results should be interpreted with caution because the quality and the risk of bias of the studies are ambiguous and need to be evaluated. Moreover, the impact of such interventions on sexual knowledge, attitudes and/or behaviour has not yet been fully elucidated. The limited number of included studies points to the need for additional research. Future studies need to consider the specific features associated with improving the adoption of sexual mobile interventions.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, DHJ906956 supplemental material for Mobile health applications for improving the sexual health outcomes among adults with chronic diseases: A systematic review by Hesam Karim, Hamid Choobineh, Niloofar Kheradbin, Mohammad Hosseini Ravandi, Ahmad Naserpor and Reza Safdari in Digital Health

Acknowledgements

This paper is a part of a PhD thesis in the field of medical informatics funded by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS). We thank all authors for their contribution.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Contributorship

HK developed the review protocol, drafted the manuscript and management all process of review. NKH, MHR, and AN completed studies searching, screening, data extraction, and quality assessment. RS and HCH supervised this work. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

No application.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor

R.S.

ORCID iD

Hesam Karim https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5865-028X

Peer review

This manuscript was reviewed by reviewers who have chosen to remain anonymous.

Supplemental Material

Supplementary material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Holmes LG, Himle MB, Strassberg DS. Parental romantic expectations and parent–child sexuality communication in autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2016; 20: 687–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards WM, Coleman E. Defining sexual health: A descriptive overview. Arch Sex Behav 2004; 33: 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hucker A, McCabe MP. A qualitative evaluation of online chat groups for women completing a psychological intervention for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marit Ther 2014; 40: 58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hummel SB, Van Lankveld J, Oldenburg HSA, et al. Efficacy of Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in improving sexual functioning of breast cancer survivors: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 1328–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cockerham WC, Hamby BW, Oates GR. The social determinants of chronic disease. Am J Prev Med 2017; 52: S5–S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schover LR, Yuan Y, Fellman BM, et al. Efficacy trial of an Internet-based intervention for cancer-related female sexual dysfunction. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013; 11: 1389–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe MP, Price E, Piterman L, et al. Evaluation of an internet-based psychological intervention for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 2008; 20: 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones LM, McCabe MP. The effectiveness of an Internet-based psychological treatment program for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2011; 8: 2781–2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn KE, Lindau ST, Lin L, et al. Development and validation of a single-item screener for self-reporting sexual problems in U.S. adults. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30: 1468–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva BM, Rodrigues JJ, De La Torre Díez I, et al. Mobile-health: A review of current state in 2015. J Biomed Inform 2015; 56: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eysenbach G. CONSORT-EHEALTH: Implementation of a checklist for authors and editors to improve reporting of web-based and mobile randomized controlled trials. Stud Health Technol Inform 2013; 192: 657–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hucker A, McCabe MP. Incorporating mindfulness and chat groups into an online cognitive behavioral therapy for mixed female sexual problems. J Sex Res 2015; 52: 627–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Lankveld JJ, Leusink P, Van Diest S, et al. Internet-based brief sex therapy for heterosexual men with sexual dysfunctions: A randomized controlled pilot trial. J Sex Med 2009; 6: 2224–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wayal S, Bailey JV, Murray E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised control trials of interactive digital interventions for sexual health promotion. Sex Transm Infect 2015; 91: A83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wayal S, Bailey JV, Murray E, et al. Interactive digital interventions for sexual health promotion: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014; 384: 85–85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeSmet A, Shegog R, Van Ryckeghem D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions for sexual health promotion involving serious digital games. Games Health J 2015; 4: 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brusse C, Gardner K, McAullay D, et al. Social media and mobile apps for health promotion in Australian Indigenous populations: Scoping review. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16: e280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muessig KE, Pike EC, Legrand S, et al. Mobile phone applications for the care and prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases: A review. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunny C, Taylor D, Memetovic J, et al. Short message service (SMS) interventions for the prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections: A systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2014; 3: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.L’Engle KL, Mangone ER, Parcesepe AM, et al. Mobile phone interventions for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2016; 138: e20160884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Condran B, Gahagan J, Isfeld-Kiely H. A scoping review of social media as a platform for multi-level sexual health promotion interventions. Can J Hum Sex 2017; 26: 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal S, LeFevre AE, Lee J, et al. Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist. BMJ 2016; 352: i1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hummel SB, Van Lankveld J, Oldenburg HSA, et al. Sexual functioning and relationship satisfaction of partners of breast cancer survivors who receive internet-based sex therapy. J Sex Marit Ther 2019; 45: 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummel SB, Van Lankveld J, Oldenburg HSA, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy realizes long-term improvement in the sexual functioning and body image of breast cancer survivors. J Sex Marit Ther 2018; 44: 485–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hummel SB, Van Lankveld JJ, Oldenburg HS, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women treated for breast cancer: Design of a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2015; 15: 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, et al. A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer 2012; 118: 500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hitt WC, Low GM, Lynch CE, et al. Application of a telecolposcopy program in rural settings. Telemed J E Health 2016; 22: 816–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winterling J, Wiklander M. Development of a self-help Web-based intervention targeting young cancer patients with sexual problems and fertility distress in collaboration with patient research partners. JMIR Res Protoc 2016; 5: e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiklander M, Strandquist J, Obol CM, et al. Feasibility of a self-help web-based intervention targeting young cancer patients with sexual problems and fertility distress. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25: 3675–3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiljer D, Urowitz S, Barbera L, et al. A qualitative study of an Internet-based support group for women with sexual distress due to gynecologic cancer. J Cancer Educ 2011; 26: 451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brotto LA, Dunkley CR, Breckon E, et al. Integrating quantitative and qualitative methods to evaluate an online psychoeducational program for sexual difficulties in colorectal and gynecologic cancer survivors. J Sex Marit Ther 2017; 43: 645–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wootten AC, Meyer D, Abbott JM, et al. An online psychological intervention can improve the sexual satisfaction of men following treatment for localized prostate cancer: outcomes of a randomised controlled trial evaluating My Road Ahead. Psychooncology 2017; 26: 975–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pauwels E, Van Hoof E, Charlier C, et al. Design and process evaluation of an informative website tailored to breast cancer survivors’ and intimate partners’ post-treatment care needs. BMC Res Notes 2012; 5: 548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barak A, Klein B, Proudfoot JG. Defining Internet-supported therapeutic interventions. Ann Behav Med 2009; 38: 4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doss BD, Cicila LN, Georgia EJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the web-based OurRelationship program: Effects on relationship and individual functioning. J Consult Clin Psychol 2016; 84: 285–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarski AC, Berking M, Fackiner C, et al. Internet-based guided self-help for vaginal penetration difficulties: Results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Sex Med 2017; 14: 238–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stechova K, Mastikova L, Urbaniec K, et al. Sexual dysfunction in women treated for type 1 diabetes and the impact of coexisting thyroid disease. Sex Med 2019; 7: 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park YE, Kim TO. Sexual dysfunction and fertility problems in men with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Mens Health 2019; 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santana LM, Perin L, Lunelli R, et al. Sexual dysfunction in women with hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Hypertens Rep 2019; 21: 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hucker A, McCabe MP. An online, mindfulness-based, cognitive–behavioral therapy for female sexual difficulties: Impact on relationship functioning. J Sex Marit Ther 2014; 40: 561–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis D. Computer-based approaches to patient education: A review of the literature. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1999; 6: 272–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mevissen FE, Doubova SV, Infante-Castaneda C, et al. Internet-based educational intervention to prevent risky sexual behaviors in Mexican adolescents: Study protocol. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailey J, Mann S, Wayal S, et al. Sexual health promotion for young people delivered via digital media: A scoping review. Public Health Research 2015; 3: 1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaw RJ, Steinberg DM, Bonnet J, et al. Mobile health devices: Will patients actually use them? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016; 23: 462–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nouri R, Niakan Kalhori S, Ghazisaeedi M, et al. Criteria for assessing the quality of mHealth apps: A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 25: 1089–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheung K, Ling W, Karr CJ, et al. Evaluation of a recommender app for apps for the treatment of depression and anxiety: An analysis of longitudinal user engagement. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 25: 955–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lustria MLA, Cortese J, Noar SM, et al. Computer-tailored health interventions delivered over the Web: Review and analysis of key components. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 74: 156–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hui CY, Walton R, McKinstry B, et al. The use of mobile applications to support self-management for people with asthma: A systematic review of controlled studies to identify features associated with clinical effectiveness and adherence. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017; 24: 619–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andersson E, Walen C, Hallberg J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of guided Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med 2011; 8: 2800–2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Webster R, Michie S, Estcourt C, et al. Increasing condom use in heterosexual men: development of a theory-based interactive digital intervention. Transl Behav Med 2016; 6: 418–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Webster R, Gerressu M. Defining the content of an online sexual health intervention: the MenSS Website. JMIR Res Protoc 2015; 4: e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hobbs L, Bailey J, Murray E. The effectiveness of interactive digital interventions for sexual problems in adults: A systematic review. Lancet 2013; 382: 46–46. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guse K, Levine D, Martins S, et al. Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: A systematic review. J Adolesc Health 2012; 51: 535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, DHJ906956 supplemental material for Mobile health applications for improving the sexual health outcomes among adults with chronic diseases: A systematic review by Hesam Karim, Hamid Choobineh, Niloofar Kheradbin, Mohammad Hosseini Ravandi, Ahmad Naserpor and Reza Safdari in Digital Health