Abstract

In this era of intensive electricity utilization for economic development, the role of urbanization remains inconclusive, especially in developing economies. Here, this study examined the electricity consumption and economic growth nexus in a trivariate framework by incorporating urbanization as an additional variable. Using the recent novel Maki cointegration test, Ng-Perron, Zivot-Andrews, and Kwiatkowski unit root tests along with FMOLS, DOLS and the CCR estimation methods, we relied on an annual frequency data from 1971-2014. Results from FMOLS, DOLS and the CCR regression confirms the electricity consumption-driven economic growth. This is desirable as Nigeria is heavily dependent on energy (electricity) consumption. A unidirectional causality from urbanization to electricity consumption and economic growth was found but the long-run empirical findings revealed urbanization impedes growth — a situation that has policy implications. The study highlights that though urbanization is a good predictor of Nigeria's economic growth, however, the adjustment of the energy portfolio to meet the growing urban demand will curtail the adverse and far-reaching impact of urbanization on the economy.

Keywords: Energy, Economics, Economic growth, Electricity consumption, Maki cointegration, Dynamic causality, Urbanization

Energy; Economics; Economic growth; Electricity consumption; Maki cointegration; Dynamic causality; Urbanization.

1. Introduction

The goal of every economy, be it developed, emerging or developing economies is to achieve sustainable development. Global growth necessitated the economies to require more energy for the operations of different economic sectors, this is in line with its functions as the driver of most economic activities. Electricity consumption is considered as one of the necessities in daily life as a result of its relationship with human development that comprises health, population, agricultural productivity, education, and industrial production (Asumadu-Sarkodie and Owusu, 2017). Electricity is a basic source of energy and its accessibility promotes both residential and domestic needs which has a positive correlation with factor inputs while enhancing a country's export (Narayan and Smyth, 2009), reducing poverty and eventually enhancing the overall standard of living (Poveda and Martinez, 2011). Research reveals that the growth of a given economy is negatively influenced by the level of energy consumption, then diverse arguments are needed to justify such at any point in time (Ozturk, 2010). Therefore, it is essential for growing economies to cut the level of energy consumed through the technological innovation of applying energy conservative and management techniques. Developing countries can also reduce the level of emissions by shifting attention to renewable energy sources such as solar energy, wind energy, among others. which are environmentally friendly and enhance ‘green’ growth (Bekun et al., 2019).

One of the goals of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the year 2030 is to have access to clean and modern energy (Owusu et al., 2016). Particularly, the economic growth of developing nations heavily depends on electricity consumption. Hence, a decline in electricity supply leads to a reduction in industrial sector output. Electricity consumption is an important element of economic growth and it is linked to capital and labour (Costantini and Martini, 2010). Several studies have revealed the different impact of electricity consumption on economic growth (Tang et al., 2016; Streimikiene and Kasperowicz, 2016; Mutascu, 2016; Narayan and Prasad, 2008; Shahbaz and Lean, 2012; Abosedra et al., 2009; Ahmed and Azam, 2016; Yuan et al., 2008; Iyke, 2015).

Just like many sub-Sahara African countries, Nigeria finds it difficult to meet the energy demands of its ever-increasing population. Various government reforms to salvage the situation in the energy sector have yielded little or no impact. The sector keeps falling behind expectation, for example, in 2009, only less than half of the country's population had access to electricity (Legros et al., 2009). As of 2018, about 80 million Nigerians still lack access to electricity supply in their homes (Okafor, 2018). Even after more than 5 years of privatizing the energy sector, the story still remains unchanged. The investors who acquired the six generating companies and the 11 distribution companies still grapple with the same problems (water management, low load demand by distribution companies, gas shortfall, electricity theft, inadequate supply, huge metering gap, and limited distribution networks) that has bedevilled the sector over the years. The installed generation capacity is 12,910.40 MW, with the available capacity, transmission wheeling capacity, and the peak generation ever attained at 7,652.60 MW, 8,100 MW, and 5,375 MW, respectively. Due to the challenges of the energy sector, peak generation of 5,375 MW has hardly been sustained. After the privatization of the sector on November 1, 2013, the power grid has suffered over 100 collapses both partial and total. Nigeria is blessed with lots of natural resources especially renewable energy sources which when exploited would surmount the energy woes. However, the country is yet to fully harness these renewables (wind, solar, geothermal, tide, hydropower) to solve its energy problems.

Given the backdrop, the current study focuses on Nigeria, like any other developing country needs sustainable growth. For growth to be sustainable, energy demand must be met, however, Nigeria's energy sector remains incapable to meet energy demand amidst increasing urban population. Demographic factors, such as urbanization, can deteriorate the environment and impede growth. There is a dire need to examine the increase in energy demand and urbanization on the country's economic growth which will serve as a benchmark in achieving the objectives of the SDGs. There are lots of studies on the energy-growth nexus for Nigeria, but these studies fail to examine the role of urbanization on growth knowing the upward surge in the country's urbanization rate holding to discrepancies in developmental factors like, inter alia, basic amenities, household income, and infrastructural provision in rural areas. In time-series data, economic episodes offer structural break dates which can influence the unit root, cointegration, and causality tests. Previous studies in Nigeria ignored the influence of structural breaks or considered a single break, but the current study considers up to five structural breaks in the series.

The remaining sections are as follows: section two compiles related literature on the proposed theme; section three highlights the methodological constructions and model specification used in the study. Section four discusses the empirical findings while section five provides a brief summary of the study and makes policy recommendation in relation to the research outcomes.

2. Literature review

The current theoretical and empirical underpinnings of the linkage between electricity consumption and economic growth is well established. This is not unconnected with the essential role energy consumption plays in the global and country-specific economic development. Literature on electricity consumption-growth nexus is categorized into four components namely; studies that hypothesized energy consumption promotes economic growth (Damette and Seghir, 2013; Salahuddin et al., 2015; Dogan, 2015; Shahbaz et al., 2017a, Shahbaz et al., 2017b); studies that claim economic productivity spur energy consumption, also known as conservative hypotheses (Yoo and Kwak, 2010; Apergis and Payne, 2011; Baranzini et al., 2013; Akadiri et al., 2019). The third category is known as feedback hypothesis, which reveals the presence of a bidirectional causal nexus between energy consumption and economic growth (Lee et al., 2008; Nazlioglu et al. 2013; Tang and Tan, 2013; Belaid and Abderrahmani, 2013; Osman et al., 2016). The fourth category (Ameyaw et al. 2016) refers to the neutrality hypothesis which reveals no causal link between energy consumption and economic growth.

Despite the different studies, no agreement has been reached on the causality between electricity consumption and economic growth. Findings from advanced economies used energy as a measure of energy usage (see for example; Fatai et al., 2002; Hondroyiannis et al., 2002; Stern, 2000; Glasure, 2002; Ho and Siu, 2007; Payne, 2009). Similarly, studies from developing countries that applied electricity use to represent energy consumption found different outcomes of electricity causality. Several regional studies were conducted with the view of assessing the relationship between electricity consumption and economic growth (Belaid and Abderrahmani, 2013; Nindi and Odhiambo. 2014; Rafindadi and Ozturk, 2017; Zhang et al., 2017 and Wang et al., 2017). Recent findings in the electricity-growth nexus like Balcilar et al. (2019) affirm the presence of bidirectional causality between electricity and growth based on Maki cointegration analysis. Bakirtas and Akpolat (2018) assert a unidirectional causal relationship running from economic growth to energy consumption. A study in Malawi revealed that a shock in electricity consumption is found to cause a permanent rise in economic development (Jumbe, 2004). On the contrary, studies in 17 African countries showed that electricity supply is entirely not a nostrum for economic improvements in Africa but a catalyst for improving lives and wellbeing (Wolde-Rufael, 2006; Odhiambo, 2009). Electricity consumption was found to trigger more economic productivity (GDP). Electricity consumption was found to enhance Nigeria's economic growth, however, the short-run causality revealed a unidirectional in nature, running from electricity consumption to economic growth (Bekun and Agboola, 2019). In a study that explored the causality between electricity consumption, economic growth, and environmental factors in North Africa, economic growth was found to stimulate the upsurge in electricity demand (Boukhelkhal and Bengana, 2018). However, an increase in electricity demand and economic growth drive CO2 emissions in the region. The authors further noted that achieving sustainable development will be difficult if countries in the region do not invest adequately in clean energy sources. In a similar study carried out in sub-Sahara Africa, the findings validated the notion that electricity consumption increases economic growth, while electricity quality declines growth (Chakamera and Alagidede, 2018). The study further revealed that emissions emanating from electricity stock hamper economic growth whereas the deterioration of electricity quality will have the same impact exacted by emissions emanating from electricity stock on growth. Surprisingly, unlike previous findings for African countries, a study on the electricity-growth nexus for Sudan while controlling for urbanization reported that energy consumption does not stimulate growth but rather inhibits economic growth (Elfaki et al. 2018). While Bah and Azam (2017) found no direction of causality between electricity consumption and economic growth in South Africa, Iyke (2015) reported the exact opposite for Nigeria. The findings (Iyke, 2015) suggested a unidirectional causality from electricity consumption to economic growth. Solarin et al. (2016) revisited the electricity-economic growth nexus for Angola while controlling for import, export, and urbanization from 1971-2012. The result showed that urbanization impairs growth, while electricity consumption spurs economic productivity. A feedback causality was found between economic growth and electricity consumption in Angola. nullO investigated the link between energy consumption, economic growth and CO2 emissions in Nigeria from 1971-2011 while controlling for trade and financial development. Findings revealed that economic growth drives CO2 emissions, but lowers energy demand. On the other hand, trade increases energy demand and improves environmental quality by reducing CO2 emissions. Thus, a massive investment in the financial sector is essential because of its ripple effect on the energy sector of the country. Table 1 presents selected literature on electricity consumption and economic growth. Thus, given the trajectory of the literature. Previous studies have failed to account for the covariate (like Urbanization in the electricity-led growth literature) explored in this study. On this premise, the current study revisits the theme with a new perspective and offer new insights into related literature.

Table 1.

Compilation of selected literature on electricity consumption and economic growth.

| Author(s) | Year | Methodology | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yoo and Kwak | 2010 | Hsiao causality Test | EG → ELC in Ecuador, Columbia Argentina, Chile, and Brazil. Conversely, GDP ↔ ELC for Venezuela, while a neutral effect is confirmed in Peru. |

| Apergis and Payne | 2011 | Panel error correction model | EG ↔ ELC for upper-middle-income and high-income countries is proven. |

| Ozturk and Acaravci | 2011 | Panel cointegration method | EG and ELC have a long-run relationship. |

| Das et al. | 2012 | System-GMM | ELC triggers EG. |

| Solarin and Shahbaz | 2013 | ARDL | EG ↔ Urbanization exists for Angola. |

| Nazlioglu et al. | 2014 | ARDL | EG ↔ ELC. The evidence of non-linearity is however found between the series. |

| Belaid and Abderrahmani | 2013 | Zivot–Andrews test; Gregory–Hansen cointegration test | EG ↔ ELC exists in both time periods. |

| Willie | 2014 | Granger causality test | EG → ELC in Zimbabwe. |

| Wolde-Rufael | 2014 | Panel bootstrap cointegration approach | For the case of Belarus and Bulgaria, ELC drives EG. EG → ELC in the Czech Republic, Latvia and Lithuania. Although, EG ↔ ELC is found for Ukraine and Russian. |

| Hamdi et al. | 2014 | ARDL | ELC, FDI and capital impact EG positively. |

| Aslan | 2014 | ARDL | ELC drives EG in Turkey. EG ↔ ELC also exists. |

| Karanfil and Li | 2015 | ARDL | The link between ELG and EG is sensitive to regional differences, level of incomes and degree of urbanization as well as supply risk factors. |

| Abdoli and Dastan | 2015 | FMOLS | Trade and ELC impact EG positively. EG ↔ ELC is also established. |

| Salahuddin et al. | 2015 | Panel data analysis | ELC → EG in GCC member countries over the study period. |

| Kayikci and Bildirici | 2015 | ARDL | The causality between EG and ELC is conditioned upon the level of natural resources of the sampled countries. |

| Dogan | 2015 | VECM Granger causality | ELC → EG. Higher investment in the power sector is sacrosanct. |

| Belloumi and Alshehry | 2016 | ARDL, FMOLS, DOLS and Toda-Yamamoto causality | Urbanization → EG and energy. They resolved that sustainable development in Saudi Arabia is determined by reducing energy inefficiency. |

| Osman et al. | 2016 | Pool Mean Group technique among others. | Capitalization and electricity consumption promote GDP. EG ↔ ELC is established. Capitalization → EG, and EG → capitalization. |

| Ameyaw et al. | 2016 | Vector Error Correction Model | Energy is not a determinant factor in the growth of the Ghanaian economy. |

| Shahbaz et al. | 2017a,b | Panel cointegration | Variables have long-run relationships. Moreover, EG ↔ ELC. Also, oil prices ↔ GDP is found to be valid. |

| Wang et al. | 2017 | Alternate to the bootstrap Granger causality | The finding reflects a significant positive impact of ELC on EG. In the short run, GDP → ELC. |

| Bilgili et al. | 2017 | Panel causality test | Urbanization reduces energy intensity. |

| Shahbaz et al. | 2017a,b | ARDL | The ARDL result suggests that urbanization drives ELC in Pakistan. Also, urbanization → ELC. |

| Shahbaz et al. | 2017a,b | Non-Linear ARDL | The causality result reveals that ELC → EG in the Portuguese economy. |

| Tatlı | 2017 | ARDL | The findings reveal that urbanization and economic growth negatively and significantly affect residential electricity consumption. |

| Mezghani and Ben Haddad | 2017 | Time-Varying Parameters Vector Autoregressive Model | Electricity consumption is considered a determinant factor of carbon dioxide emissions in Saudi Arabia. |

| Kahouli | 2018 | Seemingly unrelated regression. | ELC → R&D stocks, however, R&D → CO2 emissions also exist. |

| Bakirtas and Akpolat | 2018 | Panel causality test | The bivariate analysis revealed EG → energy consumption, and from urbanization → EG and energy consumption. The trivariate analysis, however, suggests that urbanization → EG and energy consumption. |

| Kumari & Sharma | 2018 | Granger causality | ELC → EG in India. |

| Balsalobre-Lorente et al. | 2018 | Panel least squares model | Renewable electricity consumption enhances the quality of the environment in 5 European Union nations. |

| Elfaki et al. | 2018 | ARDL | Energy consumption inhibits growth in Sudan. |

| Chen & Fang | 2018 | Panel Granger non-causality test | ELC → EG in all cities considered. |

| Akadiri et al. | 2018 | Panel Granger causality test | EG → ELC in Middle Eastern countries. |

| Kahouli | 2018 | GMM, 3SLS, and SUR techniques | Electricity consumption promotes economic growth in Mediterranean countries. |

| Akadiri et al. | 2019 | ARDL and Toda-Yamamoto for Granger causality. | EG → ELC. |

| Balcilar et al. | 2019 | Maki cointegration test and Toda-Yamamoto causality test | Maki cointegration test validates long-run associations among the variables. Furthermore, EG ↔ ELC. Also, there is unidirectional causality ELC → CO2. |

| Bekun and Agboola | 2019 | Maki cointegration test, DOLS and FMOLS techniques | The main finding documented that electricity-induced growth in Nigeria. Also, in the short run ELC → EG. |

Note: ↔ and → denote the bidirectional and unidirectional causality respectively. ELC, EG and CO2 represent electricity consumption, economic growth and carbon dioxide emissions respectively.

3. Methodological construction

3.1. Model specification

This study explored the electricity-growth nexus in the fastest urbanized country in Africa (Nigeria). In the quest to investigate this theme, and the direction of causality, our study built on the existing literature (Shahbaz and Lean, 2012). The econometric model used for the empirical analysis is specified as:

| (1) |

where represents real income level in per capita term, denotes electricity consumption per capita while is urbanization. Data range from 1971 to 2014 for the case of Nigeria. All data were retrieved from the WDI (2017). Urbanization induces structural changes in an economy, therefore, its impact on energy consumption cannot be ignored (Solarin and Shahbaz, 2013). As argued by Alam et al. (2007), urbanization is a core factor in the development process. Urbanization creates a cluster of the population that is involved in different economic activities. In turn, economic activities raise the demand for electricity.

3.2. Unit root test

The Zivot and Andrew (1992) unit root test (ZA, hereafter) was applied to account for a structural break in the variables. The three different strands of the test are shown in Eq. (2), Eq. (3), and Eq. (4a) which suggest a break in the intercept, trend, intercept and trend respectively.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4a) |

Where is the possible breakpoint, is the upper limit of the lag length of the explanatory variables. Also, will be equivalent to if and it will be 0 if otherwise.

3.3. Cointegration test

Traditional cointegration tests like Engle and Granger (1987), Johansen (1991), Banerjee et al. (1998) and Boswijk (1995) break down when there are structural breaks in the series. Hence, leading to erroneous estimates of the relationship among variables — especially long-run equilibrium relationship. The reverse is the case for tests like Carrion-i-Silvestre and Sansó (2006), Gregory and Hansen (1996), Hatemi-j (2008), ZA (1992) and Westerlund and Edgerton (2007) which account for one or two structural breaks in the series. However, relying on a single structural break can create a similar problem like those encountered in using the conventional standard cointegration tests. This study used the Maki (2012) cointegration test which considers up to five structural breaks in the series. As a prerequisite for adopting this test, the selected variables are expected to be nonstationary but integrated at I(1). There are four alternative models proposed by the test shown in Eqs. (4b), (5), (6), and (7), expressed as: Model I: Break in intercept and without trend

| (4b) |

Model II: Break in intercept and coefficients and without trend

| (5) |

Model III: Break only in intercept and coefficients, but the model has a trend

| (6) |

Model IV: Break in intercept, coefficients and trend

| (7) |

is the dummy variable while and remain as explained above.

3.4. Estimation of long-run coefficients

In the case of cointegrated variables, the need to estimate the long-run coefficients for the various variables used in the study is relevant. For this purpose, the fully modified ordinary least squares (FMOLS), dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) and the Canonical cointegration regression (CCR) were used. The FMOLS model is shown in Eq. (8):

| (8) |

Where q is the lag order to be determined by using the Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC) and t is the time trend. Di denotes the dummy variables of the breaking years from Maki (2012) cointegration test results. Hence, it will be possible to investigate whether these breaking years show a statistically significant effect in the long-run model. The FMOLS has the advantage of correcting for autoregression and endogeneity problem, as well as error emerging from sample bias (Narayan and Narayan, 2005).

3.5. Granger causality test

Since impact assessment is different from causation, this study adopted the Toda-Yamamoto (1995) causality test to ascertain the direction of causality. The test was preferred on the grounds that it allows for tests of augmented Granger causality, hence, providing long-run information (see, Karimo and Ogbonna, 2017). It can be carried out irrespective of the cointegration characteristics of models and the integration of the series (Gokmenoglu and Taspinar, 2018). The test recommends the modified Wald statistic (MWALD). This involves estimating VAR (k + dmax). Where dmax stands for a maximum order of integration, k is the optimal lag order. We applied a trivariate VAR (k + dmax) model which comprised of economic growth, electricity consumption and urbanization. The model is expressed as:

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

Where Y, EC and URB are all expressed in section 3.1, , and represent stochastic terms for fitted models and k denotes the optimal lag order (See AppendixA). By using the standard Chi-square statistics, Wald tests are employed to the first n-coefficient matrices.

4. Results and discussion

The summary statistics of the study shows that all the interest variables observe are positively skewed except for electricity consumption (See Table 2). The kurtosis statistic exhibits light tails as such, all series are normally distributed given the failure to reject the Jarque-Bera probability. Also observed among the series is a significant departure from their means. The Pearson correlation matrix analysis presented in Table 3 shows a positive association between growth and urbanization, which is not surprising for a heavily industrialized and growing economy like Nigeria. Similarly, we observe that urbanization and electricity consumption are positively and statistically related. However, the correlation analysis is not enough to validate our position. Thus, this study proceeds with econometrics procedure to investigate these outcomes.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics of the variables for Nigeria.

| Y | EC | URB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observations | 44 | 44 | 44 |

| Mean | 7.403 | 4.407 | 30.999 |

| Median | 7.393 | 4.467 | 30.930 |

| Maximum | 7.849 | 5.055 | 46.982 |

| Minimum | 7.048 | 3.352 | 18.151 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.239 | 0.424 | 8.643 |

| Skewness | 0.224 | -0.724 | 0.187 |

| Kurtosis | 1.657 | 3.091 | 1.883 |

| Jarque-Bera | 3.676 | 3.864 | 2.544 |

| Probability | 0.159 | 0.145 | 0.280 |

| Sum | 325.733 | 193.921 | 1363.934 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 2.455 | 7.738 | 3212.529 |

Table 3.

Pearson correlation estimates.

| Y | EC | URB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y | 1.000 | ||

| T- statistic | ----- | ||

| P- value | ----- | ||

| EC | 0.122 | 1.000 | |

| T- statistic | 0.799 | ----- | |

| P- value | 0.429 | ----- | |

| URB | 0.259 | 0.884 | 1.000 |

| T- statistic | 1.735 | 12.260 | ----- |

| P-value | 0.090*** | 0.000* | ----- |

Note: Correlation is statistically significant at *** 10% and * 1%, respectively.

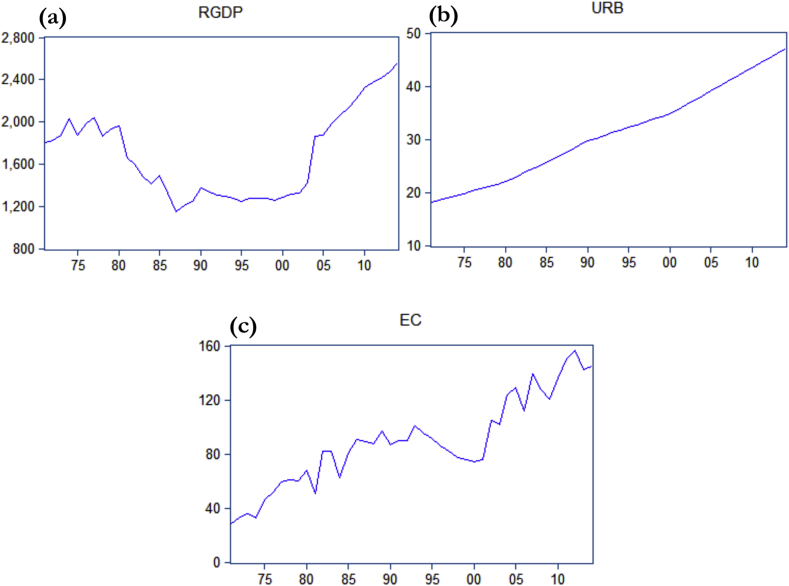

Here, we observe the series trend plot over the considered period, which shows an upward trend among all series with possible structural breaks (see Figure 1). Over the years, gross domestic product trends upward, though with the obvious business cycle and a sharp decline in the 1985 and 1986, which resonates with the period of Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) era in Nigeria — where the government sort for financial help from the Bretton Wood institutions. As such, Nigeria was required to liberalize its economy, which translated into a major structural change in the macroeconomy and a sharp decline as obverted in the visual plot. In addition, the urbanization series exhibits perpetual upward trend indicating the continuous increase in the urban population in Nigeria while electricity consumption displays many fluctuations especially in the 1980 and early 2000 that reflect the period of privatization of Nigeria's energy sector. As such, our econometric modelling accounts for such breaks which are necessary to avoid misleading statistical inferences. The current study employed both ZA and Ng-Perron that accounts for a possible single structural break and stationarity test of Kwiatkowski et al. (1992). All the tests in Table 4 are in consensus that all series are I(1). However, the ZA unit root test reveals significant break dates that resonate with Nigeria's economic and political happenings, like that of the pre and post-structural adjustment era (1984-86) characterized by major economic changes in the macroeconomy and the political episodes in the 90s.

Figure 1.

Visual plot of study variables (a) real income level (b) Urbanization (c) energy consumption.

Table 4.

Unit root tests.

| Ng-Perron |

KPSS |

Zivot-Andrews |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | MZa | MZt | MSB | MPT | nτ | ZAτ | |

| Y | -0.852 | -0.438 | 0.514 | 55.964 | 0.235* | -3.126 (0) [1994] | |

| ΔY | -20.830* | -3.227 | 0.155 | 4.375 | 0.108 | -7.151* (0) [1988] | |

| EC | -8.949 | -2.093 | 0.233 | 10.264 | 0.745* | -4.139 (0) [1994] | |

| ΔEC | -18.587* | -3.048 | 0.164 | 4.906 | 0.093 | -5.541** (3) [2002] | |

| URB | -31.394* | -3.832 | 0.122 | 3.628 | 0.840* | -3.874 (1) [1997] | |

| ΔURB | -6.774 | -1.837 | 0.271 | 13.454 | 0.075 | -5.136** (0) [1991] | |

Note: **, * indicate 5% and 1% statistical significance level. ( ) represents the optimum lag length. All tests were conducted with the model of both intercept and trend orientation.

The need for cointegration test under structural break model is pertinent in order to avoid the spurious analysis given the superior merits of the recently developed Maki (2012)1 cointegration test that accounts for five breaks dates in a cointegration model. Table 5 reports the cointegration test of the study. Table 5 shows the cointegration relationship between the variables over the considered period. This implies that there some sort of co-movement among these series in the long-run, as convergence is observed.

Table 5.

Maki (2012) Cointegration test.

| Number of Breaks Points |

Test Statistics [Critical Values] |

Break Points |

|---|---|---|

| m ≤ 5 | ||

| Model 0 | -5.418 [-5.760] | 1979,1982,1991,1994,1997 |

| Model 1 | -6.498 [-5.993]** | 1979,1984,1989,1991,2003 |

| Model 2 | -7.887 [-7.288]** | 1984,1987,1991,1999,2003 |

| Model 3 | -6.605 [-8.129]** | 1984,1989,1995,2003,2010 |

Note: [ ] shows critical values at 5 percent significance level.

** indicates significance at 5 percent.

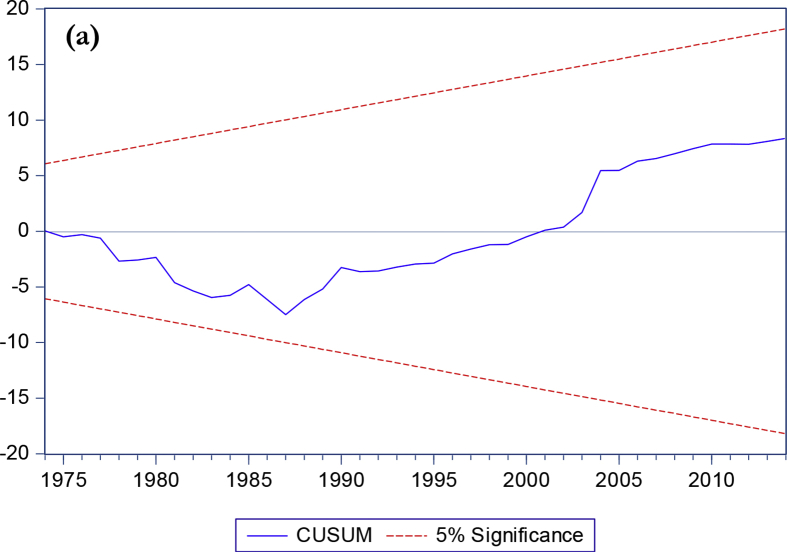

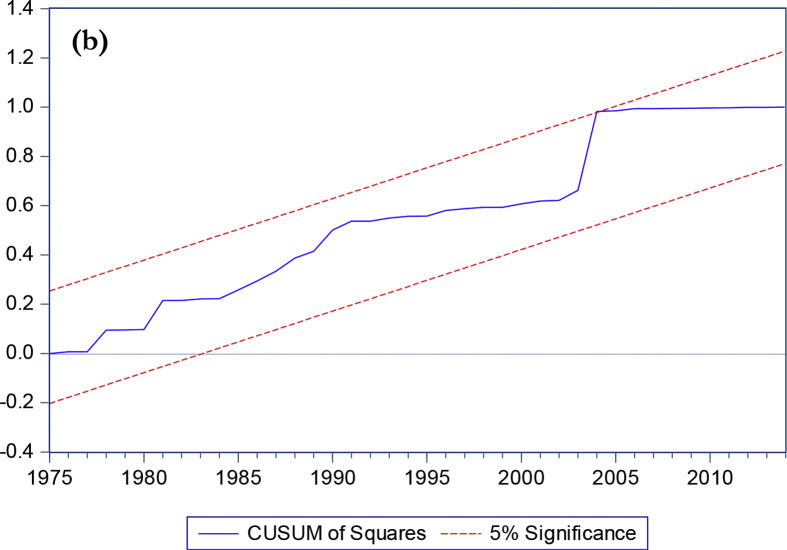

To determine the long-run coefficient among the variables under review is crucial. This study adopted the FMOLS, DOLS and CCR as tools to investigate the magnitude of the cointegration relationship among the three variables. All cointegration regression tests (FMOLS, DOLS, and CCR) are in harmony in terms of statistical significance and sign orientation and the CUSUM tests show the stability of the estimated model (AppendixB). We observe from Table 6 that an increase in electricity consumption spurs economic growth. This is necessary as Nigeria is heavily dependent on electricity. This corroborates the studies of Bekun and Agboola (2019). On the other hand, our study reveals that urbanization inhibits growth. The plausible logic for these outcomes lies in the fact that the country is driven by the primary sector as such, most people in the urban areas are also poor. This implies that most of the persons in the cities in Nigeria are not gainfully contributing to national output (GDP), this could be a possible reason for the inverse relationship observed in this study. These results are in line with the finding of a study conducted in Angola. The study conducted in South Africa (Bekun et al. 2019) further gives credence to the energy induced growth hypothesis while controlling for the contribution of capital and labour.

Table 6.

FMOLS-DOLS-CCR Long-run coefficient estimates.

| Dependent variable |

Y |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMOLS |

DOLS |

CCR |

||||

| Series name | Coefficient | t-stat. | Coefficient | t-stat. | Coefficient | t-stat. |

| EC | 0.161** | 2.222 | 0.585** | 4.221 | 0.182** | 2.163 |

| URB | -4.860* | 11.842 | -4.645* | -11.313 | -5.031* | -12.871 |

| D1984 | -0.064 | 0.568 | -1.743** | -6.594 | -0.252*** | -1.816 |

| D1989 | -0.263** | -3.090 | -2.050** | -3.708 | -0.300** | -2.278 |

| D1995 | -0.011 | 0.926 | -0.211 | -2.028 | -0.021 | -00.137 |

| D2003 | -0.120 | -1.057 | -0.258 | -1.749 | -0.192 | -1.321 |

| D2010 | 0.039 | 0.336 | -0.772** | -3.775 | 0.103 | 0.526 |

| constant | -66.798* | -10.647 | -64.771* | -10.901 | -69.397* | -11.615 |

| trend | -0.121 | -10.980 | -0.114** | -10.015 | -0.126* | -12.067 |

Note: *, ** and ***indicate significance at 1,5 and 10 percent, respectively.

Given that regression does not necessarily depict causality, the need to conduct the Toda-Yamamoto Granger causality was essential. Table 7 shows a one-way causality relationship between urbanization and economic growth. This implies that urbanization is a good predictor for economic growth in Nigeria, an empirical result consistent with Nathaniel (2019). In a similar fashion, unidirectional causality runs from urbanization to electricity consumption. This is expected given the interconnectedness of the nation, the role of globalization as countries are open to each other, thus there will be a rise in global demand for energy (electricity) consumption, and Nigeria is not an exception. This aligns with the findings of Akinlo (2008), Matthew et al. (2018), Iyke (2015) and Ogundipe et al. (2016) for the case of Nigeria. However, there is no Granger causal relationship between electricity consumption and economic growth. In another way, electricity consumption and economic growth variables are not good predictors for each other. This finding contrasts with the finding of Bekun and Agboola (2019) for Nigeria. The reason for this difference may come from model specification and data selection. However, empirical results reported in Matthew et al. (2018) show a non-causal relationship from electricity consumption to economic growth for Nigeria.

Table 7.

The Toda-Yamamoto Granger causality analysis.

| Hypothesis | Chi-square | P-value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECY | 1.571 | 0.210 | No causality relationship |

| URBY | 3.517*** | 0.060 | Causality relationship |

| YEC | 0.082 | 0.775 | No causality relationship |

| URBEC | 5.410** | 0.020 | Causality relationship |

| YURB | 0.019 | 0.901 | No causality relationship |

| ECURB | 0.702 | 0.402 | No causality relationship |

Notes: (1) The symbol ‘’’’ represents no causality between the selected variables and ** indicates 0.05 statistical significance level. (2) Optimum lag length is selected as 1 by using SIC (See Appendix A).

5. Conclusion and policy implication

This study explored the perceived relationship and causality among three variables (economic growth, urbanization and electricity consumption) in Nigeria from 1971–2014. The Maki's (2012) cointegration test in the presence of multiple structural breaks was used to ascertain the long-run relationship in the model. The results revealed the presence of a long-run relationship among the variables amidst several significant structural breaks. All long-run regression results of FMOLS, DOLS and CCR confirmed urbanization exerts a negative and inelastic statistically significant relationship on economic growth over the sampled period. We observed that electricity consumption drives economic growth. These findings confirmed the electricity (energy) induced growth hypothesis for Nigeria. The findings serve as a clarion call for the government and policymakers to initiate policies that will curtail rapid urban growth in various cities in the country. One of such policies will be to provide the needed infrastructures and other basic needs in the rural areas as this will go a long way in curbing rural-urban migration. Since energy consumption spurs economic growth, there is a dire need for improvement in energy generation in the country. The increase in the country's population which is in excess of 180 million calls for an increase in electricity generation given that the country's generational deficit. Nigeria still generates about 7,000 MW, which is far from 51,309 MW generated in South Africa from all sources with a population of about 56.72 million. It is important for Nigeria to concentrate on renewable energy sources like, inter alia, solar, wind power, geothermal, biogas, tidal power and wave power, which are environmentally friendly. This is necessary given the global consciousness and pressure to move towards sustainable and renewable energy sources. Thus, policymakers, energy, and environmental economist in Nigeria are encouraged to re-position the Nigerian energy mix to environmentally friendly sources to meet global practices.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Hamisu Sadi Ali, Gizem Uzuner & Samuel Asumadu Sarkodie: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Solomon Prince Nathaniel: Contributed analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Festus Victor Bekun: Conceived and designed the analysis; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

SA Sarkodie acknowledges the financial support of Nord University Business School, Bodø, Norway.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Footnotes

For lack of space we reported only Model 5 results. Other model results are available upon request. However, the other model results are in harmony with Model 5. There is traces cointegration among the variables under review.

Appendix A. Lag-length selection criterion

| Endogenous variables: LEC LURB LY D1 D2 D3 D4 D5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lag | LogL | LR | FPE | AIC | SC | HQ |

| 0 | 18.48744 | NA | 9.07e-05 | -0.794228 | -0.666262 | -0.748315 |

| 1 | 243.2534 | 403.4261* | 1.42e-09 | -11.85915 | -11.34729* | -11.67550* |

| 2 | 252.8079 | 15.67910 | 1.40e-09* | -11.88758* | -10.99182 | -11.56619 |

| 3 | 260.7449 | 11.80383 | 1.51e-09 | -11.83307 | -10.55341 | -11.37394 |

| 4 | 268.9541 | 10.94553 | 1.64e-09 | -11.79252 | -10.12896 | -11.19565 |

| 5 | 277.4534 | 10.02483 | 1.82e-09 | -11.76684 | -9.719381 | -11.03223 |

* indicates lag order selected by the criterion.

FPE: Final prediction error.

LR: sequential modified LR test statistic (each test at 5% level).

AIC: Akaike information criterion.

SC: Schwarz information criterion.

HQ: Hannan-Quinn information criterion.

Appendix B. Stability test for the long-run coefficients (a) CUSUM (b) CUSUM of Squares

References

- Fatai K., Oxley L., Scrimgeour F. Paper Presented at NZAE Conference; Wellington: 2002. Energy Consumption and Employment in New Zealand: Searching for Causality; pp. 26–28. June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Abdoli G., Dastan S. Electricity consumption and economic growth in OPEC countries: a cointegrated panel analysis. OPEC Energy Rev. 2015;39(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abosedra S., Dah A., Ghosh S. Electricity consumption and economic growth, the case of Lebanon. Appl. Energy. 2009;86(4):429–432. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M., Azam M. Causal nexus between energy consumption and economic. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;60:653–678. [Google Scholar]

- Akadiri S.S., Bekun F.V., Taheri E., Akadiri A.C. Carbon emissions, energy consumption and economic growth: a causality evidence. Int. J. Energy Technol. Pol. 2019;15(2-3):320–336. [Google Scholar]

- Akinlo A.E. Energy consumption and economic growth: evidence from 11 Sub-Sahara African countries. Energy Econ. 2008;30(5):2391–2400. [Google Scholar]

- Ameyaw B., Oppong A., Abruquah L.A., Ashalley E. Causality nexus of electricity consumption and economic growth: an empirical evidence from Ghana. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2016;5(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Apergis N., Payne J. A dynamic panel study of economic development and the electricity consumption-growth nexus. Energy Econ. 2011;33(5):770–781. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan A. Causality between electricity consumption and economic growth in Turkey: an ARDL bounds testing approach. Energy. Energy Sour. part B: Econom. Plan. Pol. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Asumadu-Sarkodie S., Owusu P.A. Recent evidence of the relationship between carbon dioxide emissions, energy use, GDP, and population in Ghana: a linear regression approach. Energy Sources B Energy Econ. Plann. 2017;12(6):495–503. [Google Scholar]

- Bah M.M., Azam M. Investigating the relationship between electricity consumption and economic growth: evidence from South Africa. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017;80:531–537. [Google Scholar]

- Bakirtas T., Akpolat A.G. The relationship between energy consumption, urbanization, and economic growth in new emerging-market countries. Energy. 2018;147:110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Balcilar M., Bekun F.V., Uzuner G. Revisiting the economic growth and electricity consumption nexus in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2019;26(12):12158–12170. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsalobre-Lorente D., Shahbaz M., Roubaud D., Farhani S. How economic growth, renewable electricity and natural resources contribute to CO2 emissions? Energy Pol. 2018;113:356–367. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A., Dolado J., Mestre R. Error-correction mechanism tests for cointegration in a single-equation framework. J. Time Anal. 1998;19(3):267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Baranzini A., Weber S., Bareit M., Mathys N.A. The causal relationship between energy use and economic growth in Switzerland. Energy Econ. 2013;36:464–470. [Google Scholar]

- Bekun F.V., Agboola M.O. Electricity consumption and economic growth nexus: evidence from Maki cointegration. Eng. Econ. 2019;30(1):14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bekun F.V., Emir F., Sarkodie S.A. Another look at the relationship between energy consumption, carbon dioxide emissions, and economic growth in South Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;655:759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belaid F., Abderrahmani F. Electricity consumption and economic growth in Algeria: a multivariate causality analysis in the presence of structural change. Energy Pol. 2013;55:286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Belloumi M., Alshehry A.S. The impact of urbanization on energy intensity in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2016;8(4):375. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgili F., Koçak E., Bulut Ü., Kuloğlu A. The impact of urbanization on energy intensity: panel data evidence considering cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. Energy. 2017;133:242–256. [Google Scholar]

- Boswijk H.P. Efficient inference on cointegration parameters in structural error correction models. J. Econom. 1995;69(1):133–158. [Google Scholar]

- Boukhelkhal A., Bengana I. Cointegration and causality among electricity consumption, economic, climatic and environmental factors: evidence from North-Africa region. Energy. 2018;163:1193–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Carrion-i-Silvestre J.L., Sansó A. Testing the null of cointegration with structural breaks. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2006;68(5):623–646. [Google Scholar]

- Chakamera C., Alagidede P. Electricity crisis and the effect of CO2 emissions on infrastructure-growth nexus in Sub Saharan Africa. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018;94:945–958. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Fang Z. Industrial electricity consumption, human capital investment and economic growth in Chinese cities. Econ. Modell. 2018;69:205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini V., Martini C. The causality between energy consumption and economic growth: a multi-sectoral analysis using non-stationary cointegrated panel data. Energy Econ. 2010;32(3):591–603. [Google Scholar]

- Damette O., Seghir M. Energy as a driver of growth in oil exporting countries? Energy Econ. 2013;37:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Chowdhury M., Khan S. The dynamics of electricity consumption and growth nexus: empirical evidence from three developing regions. J. Appl. Econ. Res. 2012;6:445–466. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan E. The relationship between economic growth and electricity consumption from renewable and non-renewable sources: a study of Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015;52:534–546. [Google Scholar]

- Elfaki K.E., Poernomo A., Anwar N., Ahmad A.A. Energy consumption and economic growth: empirical evidence for Sudan. Int. J. Energy Econ. Pol. 2018;8(5):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Engle R.F., Granger C.W. Co-integration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica: J. Econom. Soc. 1987:251–276. [Google Scholar]

- Glasure Y. Energy and national income in Korea: further evidence on the role of omitted variables. Energy Econ. 2002;24:355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Gokmenoglu K.K., Taspinar N. Testing the agriculture-induced EKC hypothesis: the case of Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2018:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A.W., Hansen B.E. Practitioners’ corner: tests for cointegration in models with regime and trend shifts. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1996;58(3):555–560. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi H., Sbia R., Shahbaz M. The nexus between electricity consumption and economic growth in Bahrain. Econ. Modell. 2014;38:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Hatemi-j A. Tests for cointegration with two unknown regime shifts with an application to financial market integration. Empir. Econ. 2008;35(3):497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Ho C., Siu K. A dynamic equilibrium of electricity consumption and GDP in Hong Kong: an empirical investigation. Energy Pol. 2007;35:2507–2513. [Google Scholar]

- Hondroyiannis G., Lolos S., Papapetrou E. Energy consumption and economic growth: assessing the evidence from Greece. Energy Econ. 2002;24:319–336. [Google Scholar]

- Iyke B.N. Electricity consumption and economic growth in Nigeria: a revisit of the energy-growth debate. Energy Econ. 2015;51:166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen S. Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica: J. Econom. Soc. 1991:1551–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Jumbe C.B. Cointegration and causality between electricity consumption and GDP: empirical evidence from Malawi. Energy Econ. 2004;26(1):61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kahouli B. The causality link between energy electricity consumption, CO2 emissions, R&D stocks and economic growth in Mediterranean countries (MCs) Energy. 2018;145:388–399. [Google Scholar]

- Karanfil F., Li Y. Electricity consumption and economic growth: exploring panel specific differences. Energy Pol. 2015;28:264–277. [Google Scholar]

- Karimo T.M., Ogbonna O.E. Financial deepening and economic growth nexus in Nigeria: supply-leading or demand-following? Economies. 2017;5(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- Kayıkçı F., Bildirici M. Economic growth and electricity consumption in GCC and MENA countries. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2015;83(2):303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari A., Sharma A.K. Causal relationships among electricity consumption, foreign direct investment and economic growth in India. Electr. J. 2018;31(7):33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski D., Phillips P.C., Schmidt P., Shin Y. Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root: how sure are we that economic time series have a unit root? J. Econom. 1992;54(1-3):159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.C., Chang C.P., Chen P.F. Energy-income causality in OECD countries revisited: the key role of capital stock. Energy Econ. 2008;30:2359–2373. [Google Scholar]

- Legros G., Havet I., Bruce N., Bonjour S., Rijal K., Takada M., Dora C. World Health Organization; 2009. The Energy Access Situation in Developing Countries: a Review Focusing on the Least Developed Countries and Sub-saharan Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Maki D. Tests for cointegration allowing for an unknown number of breaks. Econ. Modell. 2012;29(5):2011–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew O.A., Ede C.U., Osabohien R., Ejemeyovwi J., Fasina F.F., Akinpelumi D. Electricity consumption and human capital development in Nigeria: exploring the implications for economic growth. Int. J. Energy Econ. Pol. 2018;8(6):8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mezghani I., Ben Haddad H. Energy consumption and economic growth: an empirical study of the electricity consumption in Saudi Arabia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017;75:145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mutascu M. A bootstrap panel Granger causality analysis of energy consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;63:166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan P.K., Narayan S. Estimating income and price elasticities of imports for Fiji in a cointegration framework. Econ. Modell. 2005;22(3):423–438. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan P.K., Prasad A. Electricity consumption–real GDP causality nexus: evidence from a bootstrapped causality test for 30 OECD countries. Energy Pol. 2008;36(2):910–918. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan P., Smyth R. Multivariate Granger causality between electricity consumption, exports and GDP: evidence from a panel of Middle Eastern countries. Energy Pol. 2009;37:229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Nathaniel S.P. Modelling urbanization, trade flow, economic growth and energy consumption with regards to the environment in Nigeria. Geojournal. 2019:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nazlioglu S., Kayhan S., Adiguzel U. Electricity consumption and economic growth in Turkey: cointegration, linear and nonlinear granger causality. Energy Sources B Energy Econ. Plann. 2014;9:315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Nindi A.G., Odhiambo N.M. Energy consumption and economic growth in Mozambique: an empirical investigation. Environ. Econ. 2014;5:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Odhiambo N.M. Energy consumption and economic growth nexus in Tanzania: an ARDL bounds testing approach. Energy Pol. 2009;37(2):617–622. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundipe A.A., Akinyemi O., Ogundipe O.M. Electricity consumption and economic development in Nigeria. Int. J. Energy Econ. Pol. 2016;6(1):134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Okafor Chineme. This Day; 2018, December 18. Nigeria’s Power Sector: 58 Years of Falling behind Expectations; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Osman M., Gachino G., Hoque A. Electricity consumption and economic growth in the GCC countries: panel data analysis. Energy Pol. 2016;98:318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu P.A., Asumadu-Sarkodie S., Ameyo P. A review of Ghana’s water resource management and the future prospect. Cogent. Eng. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk I. Literature survey on energy–growth nexus. Energy Pol. 2010;38(1):340–349. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk I., Acaravci A. Electricity consumption and real GDP causality nexus: evidence from ARDL bounds testing approach for 11 MENA countries. Appl. Energy. 2011;88:2885–2892. [Google Scholar]

- Payne J. On the dynamics of energy consumption and output in the US. Appl. Energy. 2009;86:575–577. [Google Scholar]

- Poveda A., Martínez C. Trends in economic growth, poverty and energy in Colombia: long-run and short-run effects. Energy System. 2011;2:281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Rafindadi A.A. Does the need for economic growth influence energy consumption and CO2 emissions in Nigeria? Evidence from the innovation accounting test. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;62:1209–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Rafindadi A.A., Ozturk I. Dynamic effects of financial development, trade openness and economic growth on energy consumption: evidence from South Africa. Int. J. Energy Econ. Pol. 2017;7:24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Salahuddin M., Gow J., Ozturk I. Is the long-run relationship between economic growth, electricity consumption, carbon dioxide emissions and financial development in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries robust? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015;51:317–326. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M., Lean H.H. Does financial development increase energy consumption? The role of industrialization and urbanization in Tunisia. Energy Pol. 2012;40:473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M., Benkraiem R., Miloudi A., Lahiani A. Production function with electricity consumption and policy implications in Portugal. Energy Pol. 2017;110:588–599. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M., Chaudhary A.R., Ozturk I. Does urbanization cause increasing energy demand in Pakistan? Empirical evidence from STIRPAT model. Energy. 2017;122:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Solarin S.A., Shahbaz M. Trivariate causality between economic growth, urbanisation and electricity consumption in Angola: cointegration and causality analysis. Energy Pol. 2013;60:876–884. [Google Scholar]

- Solarin S.A., Shahbaz M., Shahzad S.J.H. Revisiting the electricity consumption-economic growth nexus in Angola: the role of exports, imports and urbanization. Int. J. Energy Econ. Pol. 2016;6(3):501–512. [Google Scholar]

- Stern D. A multivariate cointegration analysis of the role of energy in the US macro economy. Energy Econ. 2000;22:267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Streimikiene D., Kasperowicz R. Review of economic growth and energy consumption: a panel cointegration analysis for EU countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;59:1545–1549. [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.F., Tan E.C. Exploring the nexus of electricity consumption, economic growth, energy prices and technology innovation in Malaysia. Appl. Energy. 2013;104:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.F., Tan B.W., Ozturk I. Energy consumption and economic growth in Vietnam. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;54:1506–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Tatlı H. Short-and long-term determinants of residential electricity demand in Turkey. Int. J. Econom. Manag. Account. 2017;25(3):443–464. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Zhao J., Hongzhou L. The electricity consumption and economic growth nexus in China: a bootstrap seemingly unrelated regression estimator approach. Comput. Econ. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Westerlund J., Edgerton D.L. New improved tests for cointegration with structural breaks. J. Time Anal. 2007;28(2):188–224. [Google Scholar]

- Willie A. 2014. Modelling the Impact of Energy Use on Economic Growth: the Case of Zimbabwe. [Google Scholar]

- Wolde-Rufael Y. Electricity consumption and economic growth: a time series experience for 17 African countries. Energy Pol. 2006;34(10):1106–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Wolde-Rufael Y. Electricity consumption and economic growth in transition countries: a revisit using bootstrap panel Granger causality analysis. Energy Econ. 2014;44:325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S., Kwak S. Electricity consumption and economic growth in seven South American countries. Energy Pol. 2010;38:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J.-H., Kang J.-G., Zhao C.-H., Hu Z.-G. Energy consumption and economic growth: evidence from China at both aggregated and disaggregated levels. Energy Econ. 2008;30(6):3077–3094. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Zhou K., Yang S., Shao Z. On electricity consumption and economic growth in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017;76:353–368. [Google Scholar]

- Zivot E., Andrews D.W.K. Further evidence on the great crash, the oil-price shock, and the unit-root hypothesis. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1992;20(1):25–44. [Google Scholar]