Abstract

Introduction

ABO blood group incompatibility between a pregnant woman and her fetus as a cause of morbidity or mortality of the fetus or newborn remains an important, albeit rare, risk. When a pregnant woman has a high level of anti-A or anti-B IgG antibodies, the child may be at risk for hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN). Performing a direct prenatal determination of the fetal ABO blood group can provide valuable clinical information.

Objective

Here, we report a next generation sequencing (NGS)-based assay for predicting the prenatal ABO blood group.

Materials and Methods

A total of 26 plasma samples from 26 pregnant women were tested from gestational weeks 12 to 35. Of these samples, 20 were clinical samples and 6 were test samples. Extracted cell-free DNA was PCR-amplified using 2 primer sets followed by NGS. NGS data were analyzed by 2 different methods, FASTQ analysis and a grep search, to ensure robust results. The fetal ABO prediction was compared with the known serological infant ABO type, which was available for 19 samples.

Results

There was concordance for 19 of 19 predictable samples where the phenotype information was available and when the analysis was done by the 2 methods. For immunized pregnant women (n = 20), the risk of HDFN was predicted for 12 fetuses, and no risk was predicted for 7 fetuses; one result of the clinical samples was indeterminable. Cloning and sequencing revealed a novel variant harboring the same single nucleotide variations as ABO*O.01.24 with an additional c.220C>T substitution. An additional indeterminable result was found among the 6 test samples and was caused by maternal heterozygosity. The 2 indeterminable samples demonstrated limitations to the assay due to hybrid ABO genes or maternal heterozygosity.

Conclusions

We pioneered an NGS-based fetal ABO prediction assay based on a cell-free DNA analysis from maternal plasma and demonstrated its application in a small number of samples. Based on the calculations of variant frequencies and ABO*O.01/ABO*O.02 heterozygote frequency, we estimate that we can assign a reliable fetal ABO type in approximately 95% of the forthcoming clinical samples of type O pregnant women. Despite the vast genetic variations underlying the ABO blood groups, many variants are rare, and prenatal ABO prediction is possible and adds valuable early information for the prevention of ABO HDFN.

Keywords: Next generation sequencing, Fetal ABO blood group, Hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn, Prenatal diagnosis, Noninvasive prediction, Cell-free DNA, Genotyping

Introduction

ABO blood group-caused hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN) is very frequent but only rarely severe [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. The ABO blood group system is the only system in which natural IgM antibodies against the corresponding antigens are universally present from a young age, at approximately 4 months. The antibodies against the antigens of the ABO blood group can be significantly boosted - sometimes for unknown reasons, sometimes due to a previous pregnancy immunization or the use of probiotics. IgG antibodies will pass over the placenta into the fetus.

HDFN can be especially severe in pregnant women with blood group O with a high titer of anti-A or anti-B [3, 6, 7, 8]. A pregnant woman with high anti-A or anti-B titers [3, 10] who has a previous record of having an icteric baby is at increased risk of subsequently having another baby with serious ABO HDFN.

Predicting the fetal ABO blood group based on the analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from maternal plasma would provide valuable early information to determine the risk of HDFN in conjunction with measuring the peak systolic velocity in the fetal middle cerebral artery [11, 12].

Blood group genotyping is used in clinical practice [13, 14, 15, 16]. However, ABO genotyping is complicated, and despite successful development of assays for fetal RHD genotyping [17, 18, 19], or more recently for KEL and other non-RhD antigen targets [20, 21, 22], less work has been done attempting a noninvasive fetal ABO prediction [23]. Due to the huge genetic variation in the ABO locus [24, 25], it is difficult to develop a simple assay that will reach 100% accuracy in different ethnic populations. However, a high accuracy for the common clinical situations, for example, in the Danish ethnic population, can be achieved with the method we present here, using just 2 PCR primer sets followed by next generation sequencing (NGS). The described solution is a compromise between practical feasibility and extensive coverage, aiming for the common blood groups expected. The noninvasive fetal ABO assay was implemented in 2017, and here, we report the first results of routine analyses and the limitations of the assay.

Materials and Methods

Samples

Pregnant women, serotyped O with an anti-A and/or anti-B titer above 512 and a history of a previous baby with ABO HDFN requiring a transfusion, were eligible for prenatal ABO prediction according to Danish guidelines [26]. Maternal plasma samples for routine prenatal ABO analysis (designated clinical samples, n = 20) were collected in 10-mL Cell-Free DNA BCT® Blood Collection tubes (Streck Inc., La Vista, NE, USA).

An additional set of plasma samples was included (designated test samples, n = 6), each consisting of 1 mL residual plasma from samples used for routine prenatal RHD determination with known maternal and fetal ABO serotypes. The test samples were identified based on the ABO determination of the child within the first 3 years after birth. Various combinations of maternal/fetal ABO were chosen, and the maternal plasma samples were anonymized, retaining only serologically determined ABO blood group information for the mother and child. These test samples were collected in EDTA tubes and left at room temperature for a few days until processing and stored as plasma at −20°C until analyzed.

DNA Extraction

For the clinical samples, the plasma was separated by centrifugation at 2,000 g for 10 min at room temperature. DNA was extracted from 4 mL of plasma using a QIAsymphony robot (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and eluted into 60 µL using a standard protocol. For the test samples, DNA was extracted from 1 mL of plasma and eluted in 60 µL of elution buffer using the QIAsymphony robot. The plasma samples were analyzed in the NGS-based prenatal assay.

Serology

Serological ABO determination was performed according to standard procedures of the DANAK ISO 15189:2013 accredited blood bank, using a column agglutination technique [27].

Noninvasive NGS-Based Prenatal Assay

Assay Principle

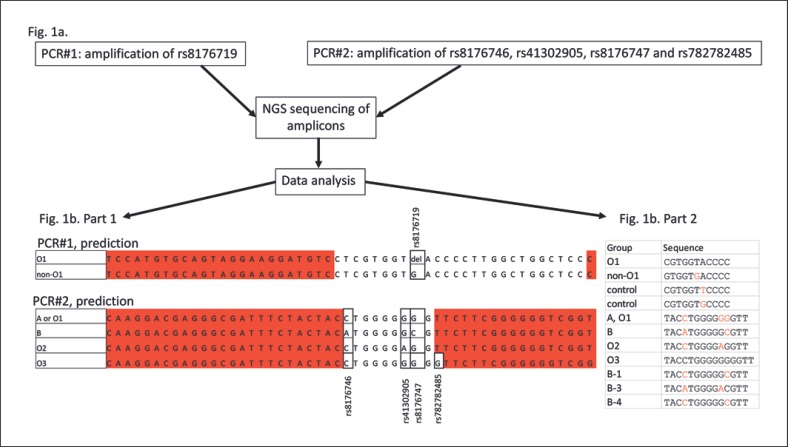

The principle of the analysis is simple and based on 2 appended PCR primer sets designed to amplify single nucleotide variations (SNVs) without allele specificity. After sequencing the PCR products, alleles are counted, and the ABO group of the pregnant woman and fetus can be deduced in most cases. One primer set amplifies the defining O 261delG deletion (rs8176719), and the other primer set amplifies both essential B-specific variants 796C>A and 803G>C (rs8176746 and rs8176747) as well as the ABO*O.02-specific 802G>A substitution (rs41302905) and the ABO*O.03-specific 804dupG (rs782782485) as shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

a Two separate PCR primer sets amplified 25 bases for ABO*O.01 261delG, 9 bases for ABO*B and ABO*O.02, and 10 bases for ABO*O.03 of both maternal and fetal cfDNA purified from maternal plasma samples. b Part 1 shows the sequenced bases, and bases marked in red are part of the primers. Part 2 shows the short strings used in the grep search to search all FASTQ sequences generated on the MiSeq instrument.

Primer Design

Primers were designed using Primer3 software [28]. We assessed standard primer criteria including 3′ stability, self-complementarity, mispriming, risk for primer-dimer formation, correct annealing temperatures, and balanced GC content. Furthermore, it was prioritized to select short PCR products with as few and rare SNVs as possible in the gene-specific primer-targeting sequences. Empirical testing of candidate designs was performed, checking the amount and purity of the PCR products and following the process described below under QC analysis. The primers decided upon are shown in Table 1, and the amplified bases are shown in Figure 1b, part 1. Primers were ordered from Eurofins Genomics (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany). The length of the O primer set gene-specific amplicon is 71 bases for ABO*O amplicons not containing the 261delG SNV and 70 bases for ABO*O amplicons containing the 261delG. The length of the B primer set gene-specific amplicon is 56 bases for ABO*A, ABO*B, and ABO*O;for ABO*O.03, the gene-specific amplicon is 57 bases.

Table 1.

Overview of primer sequences for NGS-based fetal ABO blood group prediction

| Primer name | Primer sequences |

|---|---|

| Oup2 | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT TCCATGTGCAGTAGGAAGGATGTC |

| Olow2 | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCGTGATGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATC AATGTGCCCTCCCAGACAATG |

| Bup1 | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT CAAGGACGAGGGCGATTTCTACTAC |

| Blow1 | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCGTGATGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATC TTTGCACCGACCCCCCGAAGAA |

The gene-specific part of the primers is shown in italics with the sequences needed for MiSeq sequencing appended. The Oup2 and Olow2 primer set amplifies the defining O261delG deletion (rs8176719), and the Bup1 and Blow1 primer set amplifies both essential B-specific variants 796C>A and 803G>C (rs8176746 and rs8176747) as well as the ABO*O.02-specific 802G>A substitution (rs41302905) and the ABO*O.03-specific 804dupG (rs782782485).

PCR Amplification and Presequencing QC Analysis

Extracted cfDNA was amplified in 2 separate PCR reactions (PCR1 with Oup2 and Olow2 primers, and PCR2 with Bup1 and Blow1 primers) (see Table 1 and Fig. 1), using the Phusion Hot Start enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) at the calculated annealing temperature for each primer set and 40 cycles of amplification. The PCR products were routinely tested on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent, CA, USA), and the concentration of the purified PCR product was determined by Qubit fluorometric quantitation analysis (ThermoFischer, MA, USA). We routinely only sequence PCR products with concentrations above 5 µg/mL after purification on AMPpure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA), following the recommendations from the manufacturer. The primers were tested using anonymized cfDNA, and the amount of bead-purified PCR product was generally between 20 and 40 µg/mL. The amount of spurious PCR product was estimated on a Bioanalyzer. The result of a typical Bioanalyzer run is shown in Figure 2. Whether or not to proceed with DNA sequencing was decided by an experienced person after the visual inspection of the Bioanalyzer result with assessment of the purity of the PCR product.

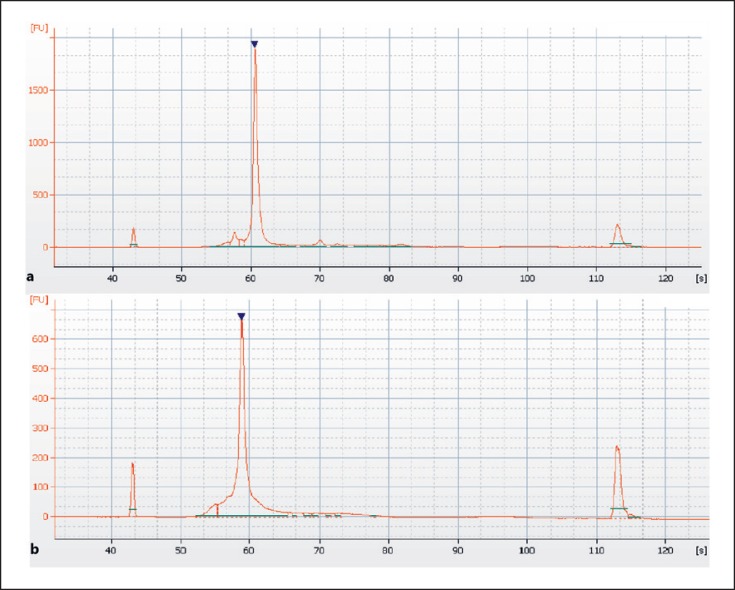

Fig. 2.

Bioanalyzer electropherogram of PCR products from the O primer set (a) and B primer set (b). The PCR products are indicated by a filled, reverse triangle, and the small peaks at approximately 45 and 115 s are the spiked-in molecular weight markers. The PCR products were diluted in molecular biology grade water and were 191/192 and 175 bp, respectively. A small amount of spurious PCR product can be seen for both the O and B primer sets. The O primer set gives a somewhat better amplification.

NGS Sequencing

NGS sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), and the 50 bp kit from Illumina was used for sequencing in one direction only while meticulously adhering to the recommendations of the vendor with only one minor modification: the PCR product was diluted in HT1 buffer as follows: 30 µL PhiX, 320 µL PCR products at 4 nM concentration, and 250 µL HT1 buffer at a total of 600 µL for loading into the sequencing cassette. We performed 26 runs, corresponding to one run per sample. For all runs, the Q30 was above 90%.

Data Analysis

The FASTQ data were analyzed in 2 ways. First, an analysis was done using the FastQC software version 0.11.5 (Bioinformatics Group at the Babraham Institute, UK; http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) which analyzes DNA sequences with a frequency of >0.1%. The reads with the same sequence are binned, and the number of reads of each allele is counted.

Second, a Unix-based grep search was performed using the search strings given in Figure 1b, part 2. An exact search for these strings was performed, and the number of times each string occurred was counted and related to the total number of reads. Samples 1–5 were originally analyzed with FastQC software only, and the results were sent to clinicians based on this single software analysis. However, when one false-negative result was found, samples 1–5 were reanalyzed with both FastQC and a grep search, and all subsequent samples were also analyzed with both methods. Thus, all samples reported here were analyzed by both FastQC and a grep search. The grep search is used to avoid false-negative outcomes. Several of the short strings are quality controls (control1, control2, B-1, B-3, and B-4), and the resulting numbers are not shown. The prediction relies on the relative number of sequences; typically, only a small number of non-ABO*O.01 sequences are found in the first primer set in cases where the woman is pregnant with a fetus positive for either A, B, O2, or O3, and the vast majority of reads show the 261delG, indicating that the pregnant woman is likely ABO*O.01 homozygous. The results of the second primer set indicate whether or not there are ABO*B, ABO*O.02, or ABO*O.03 sequences, resulting in the prediction of a B-, an O2-, or an O3-positive fetus; if there are no increases in the number of detected ABO*B, ABO*O.02, or ABO*O.03 sequences, then by deduction, the fetus is predicted to be positive for A. The fetus is predicted to be O if only ABO*O.01-specific sequences are found among the PCR sequences from the first primer set and if the ABO*B-, ABO*O.02-, or ABO*O.03-specific sequences are not found in the second PCR primer set.

Cloning and Sequencing of Novel Variant

All exons of the ABO gene from sample #19 were amplified by PCR followed by sequencing using BigDye Terminator v3.1 and analyzed on an ABI3500 Dx (Life Technologies, Denmark; for primer sequences, see Table 2). In SeqScape version 3, data were compared to the sequences from the reference NG_006669.1 (representing ABO*A1.01) and 16 controls with different ABO genotypes. To separate the 2 alleles from the patient with the new variant, a long-range PCR of 5.6 kb covering exons 3–7 was performed using the TaKaRa Taq®RR02AG (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Japan) and the forward primer for exon 3 and reverse primer for exon 7. The PCR program used was as follows: an initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 6 min; and a final 5-min extension at 72°C. PCR products were cloned into the pCRTM 2.1-TOPO TA vector (Invitrogen, Roskilde, Denmark). The clones were sequenced with the ABO-specific primers as described above. Three clones carrying a common ABO*O.01.01 allele and 2 clones with the new variant were sequenced.

Table 2.

Primers used for cloning and sequencing the ABO variant

| Exon | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5'-GTGTTCGGCCTCGGGAAG-3' | 5'-GAGGAGAGGCTGGAGACCG-3' |

| 2 | 5'-AGGGTGTGATGCCTGAATTA-3' | 5'-GCTGGACGCAGGCAATAAC-3' |

| 3 | 5'-ATGCACTTTTTGGAGGAAGG-3' | 5'-TGGGCAGAGCATAGAGAGCG-3' |

| 4 | 5'-GTTGTTCTGTGACTGTTTCT-3' | 5'-TCAGAGCCACAGGAGGAAAG-3' |

| 5 | 5'-CTTACCTGCATCCCACGCT-3' | 5'-CCGCCCTCTAATACCTTCAG-3' |

| 6 | 5'-GCAGAAGCTGAGTGGAGTTT-3' | 5'-AACACAAGGAGAGACCTCAA-3' |

| 7 | 5'-TCTGCTGCTCTAAGCCTTCC-3' | 5'-ACCCGTTCTGCTAAAACCAA-3' |

Results

An overview of the results from the prenatal testing compared with the postnatal serology is shown in Table 3. We tested a total of 26 samples from 26 different individuals. The clinical samples were from a median of 16 weeks of gestation (range 12–35), and the test samples were all from 25 weeks of gestation. In 19 cases, the postnatal serology was available; in 5 cases, the women had not yet given birth; and in 2 cases, no postnatal ABO determination was made. For the prediction of the fetal ABO type, 19 out of 19 cases were in accordance with the postnatal serology using the 2 software analyses. Two samples, #19 and #23, were indeterminable and thus not predicted (discussed in detail further below).

Table 3.

An overview of the clinical and test samples

| Case number* | Gestational age, whole weeks | Mother's serological ABO blood group | Infant's serological ABO group postnatally | Prenatal prediction | Result | O primers, totalO reads rs8176719 (–/G) | Total B reads rs8176746 (C/A) rs8176747 (G/C) | O primers, non-O reads rs8176719 (G) | Specific B reads rs8176746 (A) rs8176747 (C) | Non-O reads, % | Specific B reads, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | O | A | A | Correct | 6832784 | 5086191 | 392610 | 1 | 5.75 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 21 | O | A | A | Correct | 8008116 | 4948363 | 250852 | 8 | 3.13 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 22 | O | A | A | Correct | 7371630 | 5803623 | 102039 | 1 | 1.38 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 12 | O | O | O | Correct | 8060259 | 4756835 | 2 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 14 | O | O/A# | A | Correct | 5650568 | 4396888 | 4790 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| 6 | 12 | O | A | A | Correct | 6336566 | 5187665 | 111061 | 1 | 1.75 | 0.00 |

| 7 | 34 | O | No postnatal sample | A | N/A | 5032888 | 4578020 | 709352 | 2 | 14.09 | 0.00 |

| 8 | 13 | O | A | A | Correct | 6718605 | 11620066 | 37029 | 5 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 9 | 15 | O | O | O | Correct | 8004851 | 4546100 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 10 | 19 | O | O | O | Correct | 6704503 | 4843488 | 1 | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 11 | 27 | O | B | B | Correct | 3934914 | 3245762 | 243366 | 227327 | 6.18 | 7.00 |

| 12 | 32 | O | B | B | Correct | 7894289 | 5242408 | 465537 | 450910 | 5.90 | 8.60 |

| 13 | 16 | O | No postnatal sample | A | N/A | 4628526 | 3230323 | 157662 | 2312 | 3.41 | 0.07 |

| 14 | 15 | O | Still pregnant | O | N/A | 7336420 | 6118268 | 3 | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 15 | 14 | O | Still pregnant | A | N/A | 6407459 | 5463652 | 130356 | 1 | 2.03 | 0.00 |

| 16 | 19 | O | Still pregnant | O | N/A | 5251880 | 4059343 | 647 | 17 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 17 | 14 | O | Still pregnant | O | N/A | 6779882 | 4988903 | 47 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 18 | 25 | O | Still pregnant | B | N/A | 5820353 | 5468214 | 197961 | 375307 | 3.40 | 6.86 |

| 19 | 19 | O | B | Indeter$$ | N/A | 6289641 | 6170220 | 220494 | 3496912 | 3.51 | 56.67 |

| 20 | 28 | O | O | O | Correct | 6193016 | 5318222 | 1299 | 77 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| 21 | 25 | A | AB | B$$ | Correct | 3845935 | 2959306 | 1793567 | 10665 | 46.64 | 0.36 |

| 22 | 25 | O | A | A | Correct | 8406658 | 5799271 | 2588 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| 23 | 25 | B | O | Indeter | N/A | 5440367 | 4240078 | 2453856 | 2364791 | 45.10 | 55.77 |

| 24 | 25 | A | B | B | Correct | 5317095 | 19183 | 2832475 | 1780 | 53.27 | 9.28 |

| 25 | 25 | A | O | not B$$ | Correct | 3866705 | 3329210 | 1883678 | 1 | 48.72 | 0.00 |

| 26 | 25 | O | A | A | Correct | 3728609 | 3203736 | 8367 | 13 | 0.22 | 0.00 |

The number of specific reads was a result of the grep string search among all the FASTQ reads in a given sequencing run. No ABO*O.02 or ABO*O.03 groups were detected in any of the samples. N/A, not applicable; Indeter, indeterminable.

Clinical samples (sample numbers 1–20), test samples (sample numbers 21–26).

Twin pregnancy; one twin was O, the other was A. Originally, we used only FastQC analysis for samples 1–5, and this gave a false negative reply for sample #5. However, using the two bioinformatics analysis methods, this sample is correctly predicted to be A. $$Only possible to predict an A or B blood type. $$Prediction in these samples is based on the B-specific primer set only. For #21, it is not possible to predict whether the fetus is AB or B, only that the fetus has the B antigen, which is the relevant information. For #25, it is not possible to predict whether the fetus is AB or AO, only whether the fetus has the B antigen, which is the relevant information for determining the risk for HDFN.

The results from the 2 samples, #21 and #25, relied solely on the B-specific primer set. For #21, it is not possible to predict whether the fetus is type AB or B, as the pregnant woman is type A; it is only possible to predict that the fetus has the B antigen. For #25, it is not possible to predict whether the fetus is type O or AO, as the pregnant woman's genotype was clearly ABO*A/ABO*O; it is only possible to predict that this fetus does not have the B antigen. In both cases, this is the relevant clinical information pertaining to the potential risk of HDFN. This illustrates a limitation of the assay.

The indeterminable result of #23, among the test samples, was caused by heterozygosity of ABO*B/ABO*0.01, demonstrating a limitation where the fetal genotype cannot be predicted with this assay. Similarly, the indeterminable result of #19 made it clear that relatively rare maternal ABO*O variants may obscure the prediction of the fetal phenotype. Cloning and sequencing of the ABO gene from #19 showed a novel variant of the ABO*O, resembling the ABO*O.01.24 allele variant, except with an additional c.220C>T, Pro74Ser substitution. In this sample, the primer set interrogating the O 261delG SNV still gave 220,494 reads, which is clearly above the background, indicating the presence of either an A- or B-positive fetus. Thus, some maternal and fetal genotype combinations preclude the fetal phenotype prediction (online suppl. Table 2S; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000505464) but not for ABO*O.01 homozygous pregnant women. In addition, we found no maternal or fetal cases of ABO*O.02 or ABO*O.03 among the samples in Table 3.

The method was sensitive, as indicated by the low background number of reads in ABO*O.01 fetuses (exemplified by #4, #9, and #10 and by the specific B reads in B-negative fetuses; see Table 3). Tentatively, for clinical samples the cutoff was set at 0.025% specific reads for the non-O reads and at 0.1% for B-specific reads.

The fetal fraction of reads for the positive clinical samples was estimated to be an average of 3.9% (n = 13, range 0.1–14.1%) for the O primer set and 7.5% (n = 3, range 6.9–8.6%) for the B primer set.

Discussion

We present the results from the first clinical experience with our NGS-based noninvasive fetal ABO genotyping, based on the analysis of cfDNA from maternal plasma samples. For predictable samples, we demonstrated full concordance between the fetal ABO prediction and infant ABO type. The method is conceptually based on the previously reported method for a noninvasive prediction of fetal KEL [20], albeit here with a more complex setup with a more complicated data analysis. The combination of only 2 primer sets together with the maternal ABO serotype allows for the identification of most clinically relevant O and B alleles and, by deduction, A alleles. The A2 phenotype is not a risk factor in ABO HDFN [29]; therefore, it could be advantageous to include an extra primer set specifically amplifying the most frequent A2 SNV, 1061delC (rs56392308), to discern between ABO*A alleles with and without the deletion.

In the design of the assay primers, the final selection reflects a compromise of many factors that all placed constraints on the design. Minimizing spurious amplification is important. Additionally, keeping the amplicons short is a priority due to the size of cell-free fetal DNA, which has an average size of 143 bp [30]. The risk of allelic dropout due to a rare genetic variation in the gene-specific target region for the ABO*O primer set is very low, with the exception of one T>C SNV (rs8176720), which is 3 bases from the 5′ end in the upper primer and has an MAF of 0.4, and probably has no major impacts on the amplification efficiency. For the ABO*B primers, there are a few very rare SNVs and only one C>T SNV, rs8176745, which is located at the first 5′ base in the lower primer with an MAF of 0.2962, and probably has no significant impacts on the amplification efficiency.

All clinical samples were from type O pregnant women. The test samples were included to test the assay with different maternal/fetal ABO blood group combinations; even though these samples were not taken optimally in stabilizing blood tubes and only 1 mL was used for the DNA extraction, reliable predictions were made.

Of the 26 samples tested, 2 samples were classified as indeterminable, demonstrating limitations for predicting the fetal ABO type. There were 2 general sources of limitations: one due to the interference by the maternal genotype that obscures a relatively few fetal reads, and the other due to a hybrid ABO*O/ABO*B allele. Sample #19 exemplified interference by a rare maternal variant resembling ABO*O.01.24 (with an additional c.220C>T substitution) that we cloned and sequenced. However, this situation can be realized as a maternal phenotype is always known before the analysis, thus hindering a false prediction of the fetal ABO type. Furthermore, some ABO*O alleles cannot be detected in this assay as they lack the 261delG deletion shared by most O alleles; these alleles are shown in the lower part of online supplementary Table 1S. As the maternal serotype is always known, these rare situations can also be recognized during the analysis. Sample #23 exemplified the interference by a heterozygous ABO*B/ABO*O.01 pregnant woman (this situation would be equivalent among type O pregnant women to an ABO*O.01/ABO*O.02 heterozygous pregnant woman and is also valid for ABO*O.01/ABO*O.03 heterozygous pregnant women), making the prediction of the fetal blood group impossible. Online supplementary Table 2S depicts possible maternal/fetal genotype combinations and how specific combinations may interfere with fetal ABO genotyping using the current assay. If the fetal fraction could be reliably and significantly increased, the heterozygote limitations could be overcome.

In further detail, the heterozygosity of maternal ABO*O.01/ABO*O.02 has an expected frequency of approximately 3.4% in the Caucasian population, and the ABO*O.01.24 allele (a hybrid O/B gene carrying the 261delG variant and with both the ABO*B-specific 796C>A and 803G>C variants) has a frequency of 2.39% (online suppl. Table 1S). Together, these sources are theoretically by far the 2 most frequent causes of the inability to make a noninvasive fetal ABO prediction from type O pregnant women in the present assay, constituting approximately 5.8% of cases. It is important to note that even though a definite fetal A or B prediction cannot be determined in the cases of hybrid ABO*O.01/ABO*B genes, it is possible to state that the fetus is positive for either A or B antigens. Based on these calculations, we estimate that in approximately 95% of the pregnant type O women, we can assign a reliable fetal ABO type. It should be noted, however, that among 1,004 genotyped Danish blood donors, not a single ABO*O.01.24 allele was detected [16]. From a cohort of approximately 14,000 genotyped Danish blood donors, not a single haplotype compatible with ABO*O.01.24 or ABO*O.01.41 was found by interrogating the 261delG variant (rs8176719), 526G>C (rs7853989), and 657C>T (rs8176741) (data not shown). This may indicate that the ABO*O.01.24 allele is rare among Danish blood donors and, consequently, that the estimate of 95% is very conservative. It should be kept in mind though that the blood donor population does not precisely reflect the variation of the general population.

In addition, FUT1 (responsible for synthesis of H-substance) variants were not investigated in the assay, and this must be taken into consideration in the resulting prediction of the fetal ABO phenotype so as not to give a misleading result of the assay to clinicians.

Knowledge of the genetic variability in the ABO locus continues to accumulate as investigations are carried out [20, 22, 25]. Our discovery of a new variant among only 26 samples exemplifies this variability. However, it is probably unlikely that novel frequent ABO variants will be discovered among Caucasians.

The prediction of all fetal ABO groups was concordant in all 19 samples with the available infant postnatal ABO type. Early on after the development of the assay, we had one false-negative result when using only the FastQC analysis. We therefore implemented an additional analysis method, which, when applied to the former false-negative sample, yielded a positive result. The reliability and robustness of the assay needs to be further evaluated with a larger set of samples, for example, for determining a definite lower cutoff value for both primer sets to increase the accuracy of the predictions. Others have also established a prenatal test for predicting the fetal ABO blood group, but that test was based on real-time PCR and had 5 false-negative results in a total of 73 cases [23].

The overall strengths of the assay are that it is reliable and sensitive and that the situations where the fetal ABO group is indeterminable can be realized. Furthermore, it should be noted that the assay also provides information on the maternal ABO genotype for the investigated SNVs. The overall weaknesses include the limitation to approximately 95% of pregnant women in the Caucasian population, the assay is technically challenging, and the interpretation requires some experience.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the clinical application of a noninvasive fetal ABO prediction. We investigated a small clinical cohort, and more samples should be run to substantiate cutoff levels and to further assess the accuracy. We did not analyze samples before gestational age of 10 weeks. We estimate that we can assign a reliable fetal ABO type in approximately 95% of clinical samples. Consequently, the patients with clinical ABO HDFN in high-risk pregnancies can be predicted and preemptively cared for to prevent serious morbidity.

Statement of Ethics

The reported data are the results from a routine analysis of previously collected samples used for developing a clinically applicable method, thus not requiring approval by the Ethics Committee. Informed consent for the publication of the sequenced variant ABO blood group data was obtained from the patient.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was obtained for this work, which is a collection of routine analysis results.

Author Contributions

K.R. conceived the idea for the analytical principle of the analysis and data interpretation, designed all primers for the antenatal assay, established the analysis in the laboratory, and drafted the manuscript. C.E.H. set up the grep search data analysis. F.B.C. contributed to the design of the work and the data interpretation and substantially contributed to writing the manuscript. M.A.J. performed the cloning and sequencing of the variant. M.H.D. suggested the application of the analytical principle for antenatal ABO analysis, promoted the notion of the clinical value of the analysis, and supervised the work. All authors contributed to data acquisition and the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

Birgitte Suhr Bundgaard and staff are thanked for their excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1.Doyle B, Quigley J, Lambert M, Crumlish J, Walsh C, McParland P, et al. A correlation between severe haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn and maternal ABO blood group. Transfus Med. 2014 Aug;24((4)):239–43. doi: 10.1111/tme.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akanmu AS, Oyedeji OA, Adeyemo TA, Ogbenna AA. Estimating the Risk of ABO Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn in Lagos. J Blood Transfus. 2015;2015:560738. doi: 10.1155/2015/560738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li P, Pang LH, Liang HF, Chen HY, Fan XJ. Maternal IgG Anti-A and Anti-B Titer Levels Screening in Predicting ABO Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn: A Meta-Analysis. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2015;34((6)):341–50. doi: 10.3109/15513815.2015.1075632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matteocci A, De Rosa A, Buffone E, Pierelli L. Retrospective analysis of HDFN due to ABO incompatibility in a single institution over 6 years. Transfus Med. 2019 Jun;29((3)):197–201. doi: 10.1111/tme.12512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain A, Malhotra S, Marwaha N, Kumar P, Sharma RR. Severe ABO hemolytic disease of fetus and newborn requiring blood exchange transfusion. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2018 Jul-Dec;12((2)):176–9. doi: 10.4103/ajts.AJTS_106_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar R, Saini N, Kaur P, Sood T, Kaur G, Bedi RK, et al. Severe ABO Hemolytic Disease of Newborn with High Maternal Antibody Titres in a Direct Antiglobulin Test Negative Neonate. Indian J Pediatr. 2016 Jul;83((7)):740–1. doi: 10.1007/s12098-015-1926-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zonneveld R, van der Meer-Kapelle L, Sylva M, Brand A, Zijlstra M, Schonewille H. Severe Fetal Hemolysis and Cholestasis Due to High-Titer Maternal IgG Anti-A Antibodies. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr;143((4)):e20182859. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drabik-Clary K, Reddy VV, Benjamin WH, Boctor FN. Severe hemolytic disease of the newborn in a group B African-American infant delivered by a group O mother. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2006;36((2)):205–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goraya J, Basu S, Sodhi P, Mehta S. Unusually severe ABO hemolytic disease of newborn. Indian J Pediatr. 2001 Mar;68((3)):285–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02723208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakkeheim E, Bergerud U, Schmidt-Melbye AC, Akkök CA, Liestøl K, Fugelseth D, et al. Maternal IgG anti-A and anti-B titres predict outcome in ABO-incompatibility in the neonate. Acta Paediatr. 2009 Dec;98((12)):1896–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mari G, Deter RL, Carpenter RL, Rahman F, Zimmerman R, Moise KJ, Jr, et al. Collaborative Group for Doppler Assessment of the Blood Velocity in Anemic Fetuses Noninvasive diagnosis by Doppler ultrasonography of fetal anemia due to maternal red-cell alloimmunization. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jan;342((1)):9–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001063420102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerman R, Carpenter RJ, Jr, Durig P, Mari G. Longitudinal measurement of peak systolic velocity in the fetal middle cerebral artery for monitoring pregnancies complicated by red cell alloimmunisation: a prospective multicentre trial with intention-to-treat. BJOG. 2002 Jul;109((7)):746–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westhoff CM. Blood group genotyping. Blood. 2019 Apr;133((17)):1814–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-833954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyland CA, Roulis EV, Schoeman EM. Developments beyond blood group serology in the genomics era. Br J Haematol. 2019 Mar;184((6)):897–911. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lane WJ, Vege S, Mah HH, Lomas-Francis C, Aguad M, Smeland-Wagman R, et al. MilSeq Project Automated typing of red blood cell and platelet antigens from whole exome sequences. Transfusion. 2019 Oct;59((10)):3253–63. doi: 10.1111/trf.15473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krog GR, Rieneck K, Clausen FB, Steffensen R, Dziegiel MH. Blood group genotyping of blood donors: validation of a highly accurate routine method. Transfusion. 2019 Oct;59((10)):3264–74. doi: 10.1111/trf.15474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Schoot CE, de Haas M, Clausen FB. Genotyping to prevent Rh disease: has the time come? Curr Opin Hematol. 2017 Nov;24((6)):544–50. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clausen FB. Lessons learned from the implementation of non-invasive fetal RHD screening. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2018 May;18((5)):423–31. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2018.1461562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H, Llewellyn A, Walker R, Harden M, Saramago P, Griffin S, et al. High-throughput, non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal rhesus D status in RhD-negative women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2019 Feb;17((1)):37. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1254-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rieneck K, Bak M, Jønson L, Clausen FB, Krog GR, Tommerup N, et al. Next-generation sequencing: proof of concept for antenatal prediction of the fetal Kell blood group phenotype from cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma. Transfusion. 2013 Nov;53((11 Suppl 2)):2892–8. doi: 10.1111/trf.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wienzek-Lischka S, Krautwurst A, Fröhner V, Hackstein H, Gattenlöhner S, Bräuninger A, et al. Noninvasive fetal genotyping of human platelet antigen-1a using targeted massively parallel sequencing. Transfusion. 2015 Jun;55((6 Pt 2)):1538–44. doi: 10.1111/trf.13102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orzińska A, Guz K, Mikula M, Kluska A, Balabas A, Ostrowski J, et al. Prediction of fetal blood group and platelet antigens from maternal plasma using next-generation sequencing. Transfusion. 2019 Mar;59((3)):1102–7. doi: 10.1111/trf.15116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song W, Zhou S, Shao L, Wang N, Pan L, Yu W. Non-invasive fetal ABO genotyping in maternal plasma using real-time PCR. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015 Nov;53((12)):1943–50. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Möller M, Hellberg Å, Olsson ML. Thorough analysis of unorthodox ABO deletions called by the 1000 Genomes project. Vox Sang. 2018 Feb;113((2)):185–97. doi: 10.1111/vox.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Möller M, Jöud M, Storry JR, Olsson ML. Erythrogene: a database for in-depth analysis of the extensive variation in 36 blood group systems in the 1000 Genomes Project. Blood Adv. 2016 Dec;1((3)):240–9. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016001867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Føtal anæmi og håndtering af gravide med alloimmunisering (Danish guidelines 2019) Danish Society for Fetal medicine http://www.dfms.dk/fagligt/guidelines/378-fotal-anaemi-2019.html.

- 27.Ono T, Ohto H, Yasuda H, Hikichi R, Kawabata K, Minakawa K, et al. Comparative study of two automated pre-transfusion testing systems (microplate and gel column methods) with standard tube technique. Int J Blood Transfus Immunohematol. 2017;7:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, et al. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Aug;40((15)):e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein HG, Anstee DJ. 12th ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014. Mollison's blood transfusion in clinical medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo YM, Chan KC, Sun H, Chen EZ, Jiang P, Lun FM, et al. Maternal plasma DNA sequencing reveals the genome-wide genetic and mutational profile of the fetus. Sci Transl Med. 2010 Dec;2((61)):61ra91. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data