Abstract

Objectives:

The Arabic-speaking population is increasing in Europe and North America. Evidence suggests that Arab migrants have a greater risk of adverse birth outcomes than nonmigrants, but the risk of stillbirth is largely understudied. We examined inequality in stillbirth rates between Arab women and the French and English majority of women in Quebec, Canada.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective study of all births in Quebec from 1981 through 2015. We computed stillbirth rates by period and cause of death, and we used log binomial regression to estimate the association between Arabic mother tongue and stillbirth, adjusted for maternal characteristics.

Results:

Stillbirth rates per 1000 births overall were lower among women with Arabic mother tongue (3.89) than among women with French or English mother tongue (4.52), and rates changed little over time. However, Arabic-speaking women from Arab countries had a higher adjusted risk of stillbirth than French- or English-speaking women (risk ratio = 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.42). Congenital anomalies, termination of pregnancy, and undetermined causes contributed to a disproportionate number of stillbirths among women with Arabic mother tongue compared with the French- and English-speaking majority.

Conclusions:

Arabic-speaking women from Arab countries have higher risks of stillbirth compared with the French and English majority in Quebec. Strategies to reduce stillbirth risk among Arabic speakers should focus on improving identification of causes of death.

Keywords: Arabs, inequalities, language, maternal health, stillbirth

Stillbirth, or the death of an infant in utero, is a global health indicator that reflects inequalities in maternal care.1 In high-income countries, the risk of stillbirth is higher among migrant populations that have cultural or communication barriers in navigating health care systems than among nonmigrant populations.2,3 Although studies conducted in Europe found that migrants from Arab regions have an elevated risk of stillbirth,4-6 little is known about Arabic speakers who may lack proficiency in the principal language of the host country. Information is particularly scarce on the prevalence and causes of stillbirth among Arabic speakers outside of Europe,7-9 including Canada, where linguistic inequality in stillbirth is increasingly recognized.10,11

Arabic accounts for a growing proportion of languages spoken in Quebec, a large Canadian province where language frequently reflects ethnicity. Arabic is the most common immigrant language in Quebec12 and is spoken by 3% of the population. Quebec is home to most Canadians of Arab descent.13 During the past 3 decades, a substantial portion of newcomers to the province have come from Arabic-speaking countries.14 Data on the perinatal health of Arabs in Canada, however, are scarce despite evidence from European countries suggesting that this population may be vulnerable to preterm birth, low birth weight, and infant mortality.15,16 The primary objective of our study was to investigate differences in stillbirth rates between women who speak Arabic and women who speak other languages in Quebec. A secondary objective was to identify the causes of fetal death that could be targeted for mortality reduction.

Methods

Data

We conducted a population-based study of 2 979 449 live births and 13 452 stillbirths by using data that were directly available on birth and stillbirth registration certificates in Quebec from 1981 through 2015.17 In Quebec, stillbirth is defined as the intrauterine death of a fetus at a viable stage of development.18 Legally, all stillborn fetuses weighing ≥500 g at delivery must be registered. Parental characteristics such as age, mother tongue, home language, place of birth, past pregnancies, and education are self-reported on birth registration certificates. The primary cause of death is recorded on stillbirth certificates.

Exposure

We identified women of Arab descent by using information on maternal mother tongue, paternal mother tongue, and language used most often at home. In Quebec, language marks cultural minority groups and also reflects ethnicity.19 French is the sole official language of Quebec, and language is a part of cultural identity. Data on maternal mother tongue and home language became available in 1981, and data on paternal mother tongue became available in 1998. We hypothesized that stillbirth disparities would be better captured with maternal mother tongue, a characteristic that reflects the cultural identity of women. In Quebec, mother tongue is defined as the first language learned in childhood that is still understood. We grouped mother tongue into 3 mutually exclusive categories: Arabic, French or English, and other languages. Mothers who reported both Arabic and French or English were rare (<0.2%) and were categorized as French or English. Most of the population in Quebec identifies French or English as a mother tongue (86.8%), and the remainder (13.9%) speaks a foreign language, including Arabic (2.5%).12

We characterized the linguistic environment of Arabic-speaking women through variables capturing maternal origin, language retention, and language proficiency. Maternal origin, or a mother’s birth country, may capture cultural background or other factors that influence perinatal health behaviors. We used maternal mother tongue and country of origin to categorize births as follows: (1) Arabic-speaking mothers from Arab countries (countries in the Arab League or other regions where Arabic is the official language), (2) Arabic-speaking mothers from non-Arab countries, (3) French or English speakers born in Canada, and (4) other. Most Arabic-speaking mothers were from Maghreb and Middle Eastern regions (81%); the 5 leading countries were Morocco, Algeria, Lebanon, Tunisia, and Syria. Data on maternal origin were available starting in 1998.

We defined language retention as women with Arabic mother tongue who kept Arabic as the home language.20 We had 4 levels of language retention: (1) Arabic maternal mother tongue and home language, (2) Arabic maternal mother tongue with French or English home language, (3) French or English maternal mother tongue and home language, and (4) other. Language retention is sometimes used as a proxy for acculturation, or the extent to which an individual adopts the home culture of the receiving country.20

We captured information on language proficiency by using data on maternal and paternal mother tongue to identify varying language abilities of parents. Our goal was to determine if the risk of stillbirth depended on which parent spoke Arabic, hypothesizing potentially stronger associations if the woman was the Arabic speaker. We categorized births into 5 levels of language proficiency: (1) Arabic-speaking mother with non–Arabic-speaking father, (2) non–Arabic-speaking mother with Arabic-speaking father, (3) Arabic-speaking mother and father, (4) French- or English-speaking mother and father, and (5) other. Data on language proficiency were available starting in 1998.

Stillbirth

The main outcome was stillbirth, which we analyzed as a binary variable (yes/no). We identified the principal cause of stillbirth by using the International Classification of Diseases, with codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision before 2000 and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision thereafter. We used a modified version of the cause of death classification system from the Public Health Agency of Canada.21 We grouped causes into 7 types: disorders of the placenta, cord, or membranes (762, P02.0-P02.9); birth asphyxia (768, P20-P21); congenital anomalies (740-759, Q00-Q99); termination of pregnancy (779.6, P96.4); maternal complications or comorbidities (760-761, P00-01); undetermined cause (779.9, P95, P96.9); and other causes. In Quebec, late pregnancy terminations in the second and third trimesters are recorded on stillbirth certificates if the weight at delivery is ≥500 g. However, the reason for termination is not available. Late terminations can be performed for various reasons, but a substantial proportion are for congenital anomalies detected during ultrasound screening mid-gestation.22

Data Analysis

We calculated stillbirth rates per 1000 total births with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We assessed trends over time and determined whether the proportion of live births and stillbirths among Arabic speakers changed. We used log binomial regression models to compute risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs for the association between language and risk of stillbirth, using French or English as the reference. We adjusted the models for maternal age (<20, 20-34, ≥35 years), parity (0, 1, ≥2 previous deliveries), maternal education (no high school diploma, high school diploma with or without vocational training, some university), and period (1981-1989, 1990-1997, 1998-2006, 2007-2015). We further estimated associations for maternal origin, language retention, and language proficiency, and we examined the distribution of stillbirths according to cause of death.

In this study, data were missing for maternal mother tongue (2.3%), paternal mother tongue (5.7%), language spoken at home (2.7%), maternal education (5.6%), birth country (1.1%), and age (0.01%). We assumed that data were missing at random and used multiple imputation to construct 5 new data sets by using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method, assuming a multivariate normal distribution.23 We imputed missing data separately for births before and after 1998, because paternal mother tongue and maternal birth country were available only later in the study. We also imputed data for live births and stillbirths separately. Imputation models included the variables maternal mother tongue, paternal mother tongue, home language, maternal birth country, age, parity, education, year, and cause of death. We performed sensitivity analyses by using a complete case–only approach, whereby we excluded births with missing data. We conducted all analyses by using SAS version 9.424 and determined significance by using 95% CIs.

For this type of study, formal consent was not required. The data were anonymous, and we obtained an ethics waiver from the ethics review board of the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre. This study complied with the Tri Council Policy Statement for ethical conduct of research involving humans in Canada.

Results

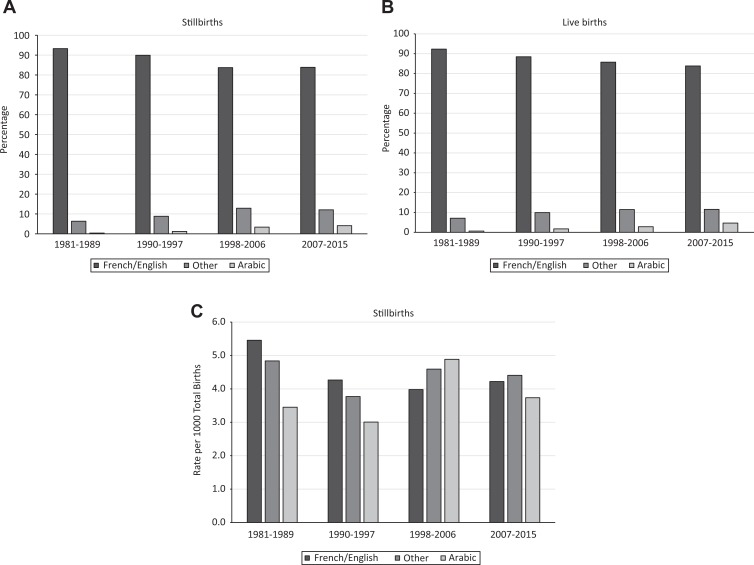

Of 13 452 stillbirths in the study, 283 (2.1%) were among women with Arabic mother tongue, 229 (1.7%) were among fathers with Arabic mother tongue, and 181 (1.3%) were among parents with Arabic home language. The percentage of stillbirths among women with Arabic mother tongue rose steadily during the study period, increasing from 0.4% of stillbirths during 1981-1989 to 4.1% of stillbirths during 2007-2015 (Figure). Similarly, the percentage of live births to Arabic speakers increased substantially during the study period, from 0.6% of live births during 1981-1989 to 4.6% of live births during 2007-2015. Arabic speakers had lower stillbirth rates at most time points than French or English speakers; however, the gap was greater during 1981-1989 than during 2007-2015. The gap narrowed over time because of a slight increase in the stillbirth rate among women with Arabic mother tongue and a decrease in the stillbirth rate among women with French or English mother tongue.

Figure.

Trends in stillbirth and live birth over time according to maternal mother tongue, Quebec, Canada, 1981-2015. (A) Percentage of stillbirths over time. (B) Percentage of live births over time. (C) Stillbirth rates over time. Data source: Med-Echo System Normative Framework—Maintenance and Use of Data for the Study of Hospital Clientele, Ministry of Health and Social Services.17

Stillbirth rates per 1000 total births were 3.89 for maternal Arabic mother tongue, 3.77 for paternal Arabic mother tongue, and 4.93 for Arabic home language (Table 1). Women with French or English mother tongue had a stillbirth rate of 4.52 per 1000 total births. The adjusted risk of stillbirth was not significantly higher for maternal Arabic mother tongue (RR = 0.92; 95% CI, 0.82-1.04) or paternal Arabic mother tongue (RR = 0.91; 95% CI, 0.80-1.04) than for French or English mother tongue. Arabic home language was, however, associated with a higher risk of stillbirth (RR = 1.19; 95% CI, 1.02-1.38) than French or English home language.

Table 1.

Stillbirth rates according to parental characteristics, Quebec, Canada, 1981-2015a

| Characteristic | Total No. of Births (n = 2 992 901) | No. of Stillbirths (n = 13 452) | Stillbirth Rate per 1000 Total Births (95% CI) | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||||

| Maternal mother tongue | |||||

| Arabic | 72 677 | 283 | 3.89 (3.44-4.35) | 0.86 (0.76-0.97) | 0.92 (0.82-1.04) |

| French/English | 2 623 245 | 11 867 | 4.52 (4.44-4.61) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 296 979 | 1302 | 4.38 (4.13-4.63) | 0.97 (0.91-1.03) | 0.93 (0.87-0.99) |

| Paternal mother tonguec | |||||

| Arabic | 60 688 | 229 | 3.77 (3.28-4.26) | 0.91 (0.80-1.04) | 0.91 (0.80-1.04) |

| French/English | 1 231 041 | 5094 | 4.14 (4.02-4.25) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 174 107 | 763 | 4.38 (4.04-4.74) | 1.06 (0.97-1.16) | 0.99 (0.91-1.08) |

| Language spoken at home | |||||

| Arabic | 36 832 | 181 | 4.93 (4.20-5.65) | 1.11 (0.96-1.29) | 1.19 (1.02-1.38) |

| French/English | 2 790 906 | 12 387 | 4.44 (4.36-4.52) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 165 163 | 884 | 5.35 (4.98-5.72) | 1.21 (1.12-1.29) | 1.13 (1.05-1.21) |

| Maternal age, y | |||||

| <20 | 112 798 | 737 | 6.54 (6.07-7.01) | 1.56 (1.45-1.68) | 1.11 (1.03-1.21) |

| 20-34 | 2 527 397 | 10 591 | 4.19 (4.11-4.27) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| ≥35 | 352 706 | 2123 | 6.02 (5.76-6.28) | 1.44 (1.37-1.50) | 1.70 (1.62-1.78) |

| Parity | |||||

| 0 | 1 340 509 | 7281 | 5.43 (5.31-5.56) | 1.63 (1.56-1.70) | 1.67 (1.61-1.74) |

| 1 | 1 059 512 | 3534 | 3.34 (3.23-3.45) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| ≥2 | 592 880 | 2637 | 4.45 (4.28-4.62) | 1.33 (1.27-1.40) | 1.21 (1.15-1.27) |

| Maternal education | |||||

| No high school diploma | 419 627 | 2574 | 6.13 (5.86-6.41) | 1.74 (1.63-1.85) | 1.78 (1.66-1.90) |

| High school with or without vocational training | 1 790 174 | 8115 | 4.53 (4.43-4.63) | 1.28 (1.23-1.34) | 1.32 (1.26-1.38) |

| Some university | 783 100 | 2763 | 3.53 (3.39-3.67) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Period | |||||

| 1981-1989 | 797 738 | 4306 | 5.40 (5.24-5.56) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1990-1997 | 729 327 | 3060 | 4.20 (4.05-4.34) | 0.78 (0.74-0.81) | 0.80 (0.76-0.84) |

| 1998-2006 | 676 698 | 2757 | 4.07 (3.92-4.23) | 0.75 (0.72-0.79) | 0.78 (0.75-0.82) |

| 2007-2015 | 789 138 | 3329 | 4.22 (4.08-4.36) | 0.78 (0.75-0.82) | 0.83 (0.79-0.87) |

a Data source: Med-Echo System Normative Framework—Maintenance and Use of Data for the Study of Hospital Clientele, Ministry of Health and Social Services.17 Missing data for maternal mother tongue, paternal mother tongue, maternal education, birth country, and age were imputed.

b Risk ratios for language are from separate models containing maternal mother tongue, paternal mother tongue, or language spoken at home. Models for maternal age, parity, maternal education, and time period were adjusted for maternal mother tongue.

c Data available beginning in 1998.

Compared with French or English speakers, several subgroups of Arabic speakers had a greater risk of stillbirth (Table 2). Compared with women with French or English mother tongue from Canada, women with Arabic mother tongue who originated from Arab countries had a significantly higher risk of stillbirth (RR = 1.23; 95% CI, 1.07-1.42), and women with Arabic mother tongue who originated from non-Arab countries had a lower risk of stillbirth (RR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.20-0.68). Compared with women whose mother tongue was French or English, women with Arabic mother tongue who spoke Arabic at home had a higher risk of stillbirth (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 1.00-1.35), whereas women with Arabic mother tongue who spoke French or English at home had a lower risk of stillbirth (RR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.61-0.88). Compared with French- or English-speaking couples, couples in which the mother but not the father had Arabic mother tongue (RR = 1.39; 95% CI, 0.94-2.04) had a higher risk of stillbirth, whereas couples in which the father but not the mother had Arabic mother tongue (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.97) had a lower risk of stillbirth. We found no association with stillbirth when both parents were Arabic speakers.

Table 2.

Risk of stillbirth among Arabic speakers according to maternal origin, language retention, and language proficiency, Quebec, Canada, 1981-2015a

| Characteristics | Total No. of Births (n = 2 992 901) | No. of Stillbirths (n = 13 452) | Stillbirth Rate per 1000 Total Births (95% CI) | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||||

| Maternal originc | |||||

| Arabic mother tongue, Arab country | 46 019 | 216 | 4.69 (4.05-5.33) | 1.22 (1.06-1.40) | 1.23 (1.07-1.42) |

| Arabic mother tongue, non-Arab country | 9429 | 13 | 1.40 (0.55-2.25) | 0.36 (0.20-0.67) | 0.37 (0.20-0.68) |

| French or English mother tongue, Canada | 1 125 786 | 4336 | 3.85 (3.74-3.97) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 284 602 | 1521 | 5.34 (5.07-5.61) | 1.39 (1.31-1.47) | 1.34 (1.26-1.42) |

| Language retention | |||||

| Arabic mother tongue and home language | 36 832 | 181 | 4.93 (4.20-5.65) | 1.09 (0.94-1.27) | 1.16 (1.00-1.35) |

| Arabic mother tongue, French or English home language | 36 722 | 112 | 3.05 (2.48-3.62) | 0.68 (0.56-0.81) | 0.73 (0.61-0.88) |

| French or English mother tongue and home language | 2 612 857 | 11 785 | 4.51 (4.43-4.59) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 306 491 | 1374 | 4.48 (4.23-4.74) | 0.99 (0.94-1.06) | 0.95 (0.90-1.01) |

| Language proficiencyc | |||||

| Arabic mother, non-Arabic father | 4825 | 28 | 5.80 (3.57-8.04) | 1.41 (0.96-2.07) | 1.39 (0.94-2.04) |

| Non-Arabic mother, Arabic father | 10 065 | 28 | 2.78 (1.73-3.83) | 0.68 (0.46-0.99) | 0.67 (0.46-0.97) |

| Arabic mother and father | 50 623 | 201 | 3.97 (3.42-4.52) | 0.96 (0.84-1.11) | 0.97 (0.84-1.11) |

| French or English mother and father | 1 198 094 | 4931 | 4.12 (4.00-4.23) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 202 230 | 898 | 4.44 (4.12-4.76) | 1.08 (1.00-1.17) | 1.01 (0.94-1.10) |

a Data source: Med-Echo System Normative Framework—Maintenance and Use of Data for the Study of Hospital Clientele, Ministry of Health and Social Services.17

b Adjusted for maternal age, parity, education, and time period.

c Data available beginning in 1998.

Disorders of the placenta, cord, or membranes explained most stillbirths regardless of language (Table 3). Women with Arabic mother tongue had a higher proportion of stillbirths due to congenital anomalies, pregnancy terminations, and undetermined causes than women with French or English mother tongue. Among Arabic speakers, 18.8% (95% CI, 14.2%-23.4%) of stillbirths (53 of 283) were due to congenital anomalies compared with 12.9% (95% CI, 12.3%-13.5%) of stillbirths (1532 of 11 867) among French or English speakers. Birth asphyxia and other causes of stillbirth were less common among Arabic speakers than among French or English speakers. Disorders of the placenta, cord, or membranes explained most stillbirths regardless of language. Sensitivity analyses in which we excluded births with missing data did not affect the interpretation of results.

Table 3.

Proportion of stillbirths by cause of death, according to maternal mother tongue, Quebec, Canada, 1981-2015a

| Cause of Death | Arabic | French or English | Other language | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Stillbirths | Proportion of Stillbirths, % (95% CI) | No. of Stillbirths | Proportion of Stillbirths, % (95% CI) | No. of Stillbirths | Proportion of Stillbirths, % (95% CI) | |

| Disorders of the placenta, cord, or membranes | 84 | 29.6 (24.2-35.0) | 3600 | 30.3 (29.5-31.2) | 415 | 31.8 (29.3-34.4) |

| Birth asphyxia | 6 | 2.1 (0.4-3.8) | 623 | 5.3 (4.8-5.7) | 41 | 3.2 (2.2-4.1) |

| Congenital anomalies | 53 | 18.8 (14.2-23.4) | 1532 | 12.9 (12.3-13.5) | 164 | 12.6 (10.8-14.4) |

| Termination of pregnancy | 25 | 8.8 (5.5-12.1) | 795 | 6.7 (6.2-7.2) | 86 | 6.6 (5.1-8.1) |

| Maternal complications or comorbidities | 24 | 8.4 (5.1-11.6) | 1135 | 9.6 (9.0-10.1) | 126 | 9.7 (8.1-11.4) |

| Other causes | 17 | 6.0 (3.2-8.8) | 1596 | 13.4 (12.8-14.1) | 169 | 13.0 (11.1-14.9) |

| Undetermined cause | 74 | 26.3 (21.2-31.4) | 2586 | 21.8 (21.0-22.5) | 301 | 23.1 (20.8-25.4) |

| Total | 283 | 100.0 | 11 867 | 100.0 | 1302 | 100.0 |

a Data source: Med-Echo System Normative Framework—Maintenance and Use of Data for the Study of Hospital Clientele, Ministry of Health and Social Services.17

Discussion

Studies of migrant populations suggest that the risk of stillbirth is generally higher among women of Arab origin than among other populations.25 In Belgium, women from Egypt and the Maghreb have up to 60% higher risk of stillbirth than nonmigrant women in Belgium.5 However, little is known about subgroups of Arabs, despite the diversity of this population. A review of industrialized areas found higher stillbirth rates among migrants from Turkey and North Africa than among nonmigrants but could not examine data on Arab persons from traditionally non-Arab countries.15 We found that country of origin affected the risk of stillbirth, but only among Arabic-speaking women who originated from Arab countries, not among Arabic-speaking women who originated from non-Arab countries. Women from Arab countries are more likely to have faced forced migration and be more vulnerable than Arabic-speaking women from non-Arab countries.

In our study, the risk of stillbirth was higher among Arabic-speaking women who retained their mother tongue at home than among Arabic-speaking women who currently spoke French or English at home. These women potentially reflect a group that is less acculturated and integrated into prevailing society than Arabic-speaking women who speak French or English at home. Acculturation encompasses greater mastery of the language of receiving countries7 and may help women access health care, including access to stillbirth prevention activities.26 Arabic-speaking women who spoke Arabic at home are less acculturated than Arabic-speaking women who speak French or English at home and may have fewer employment opportunities and lower socioeconomic status. In our study, Arabic-speaking women who spoke French or English at home had a lower risk of stillbirth than Arabic-speaking women who spoke Arabic at home. Risks also appeared to be protective for couples in which the father but not the mother spoke Arabic at home. This pattern highlights the importance of the mother’s proficiency in the language of the receiving country, which may facilitate communication with health care providers and understanding of prenatal health risks and services.27 Many stillbirths occur during emergency obstetric situations, when a woman’s ability to communicate with health care professionals is essential.

Arabic-speaking women had a higher proportion of stillbirths due to congenital anomalies and termination of pregnancy than French- or English-speaking women. Reasons for the proportionately greater number of anomaly-related stillbirths among Arabic-speaking women compared with French- or English-speaking women are hard to pinpoint but may be related to traditional risk factors, such as folic acid deficiency or inadequate nutrition. Folic acid supplementation is protective of neural tube defects, and the high proportion of stillbirth due to congenital anomalies raises the possibility that Arabic-speaking women may be less aware of this protective factor than the French or English majority.28 Other maternal risk factors such as obesity may also be prevalent, although we could not explore such factors because of a lack of data. Some congenital anomalies may be related to consanguinity or close biological relationships, which increase the chance of inherited genetic disorders. Consanguineous marriages are historically common in some Arab countries, where up to 50% of marriages are between relatives.29 Better targeting of Arabic-speaking women to identify these risk factors during the periconceptional period may be one route for preventing stillbirths.

The proportion of undetermined causes of stillbirth was also greater among Arabic-speaking women than among French- or English-speaking women. Inability to determine the cause of death is particularly concerning because knowing the cause is essential for preventing future stillbirths. Reasons for having an undetermined cause of death are unknown, but the importance of fetal autopsy in identifying the cause cannot be underestimated. Fetal autopsy is the gold standard to determine the cause of stillbirth.30 However, research indicates that fetal autopsy is used less frequently by parents in Canada who do not speak English or French than parents who do speak English or French.31 Autopsy is a procedure that requires informed consent, and language barriers can prevent parents from fully understanding its benefits. Parents may also refuse autopsy for cultural or religious reasons. In Islam, funerals are frequently performed rapidly after death, and autopsy can be perceived as disrespectful.32 Culturally sensitive ways to increase autopsy rates may be one way to lower the proportion of stillbirths with an undetermined cause of death among Arabic speakers.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, we used data collected in birth certificates that lacked information on immigrant background, duration of residence, immigrant generation, family sponsorship, and refugee status. Second, language variables were self-reported and may have been subject to misclassification, potentially attenuating the results toward the null. Third, stillbirth data were coded following prespecified algorithms, but a validation study was not performed. Fourth, data on paternal mother tongue and maternal origin were unavailable before 1998, thereby lowering the power of the analysis for these variables. Fifth, we could not analyze different types of anomalies because of sample size restrictions. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to assess whether stillbirths among subgroups of Arab women are associated with different causes of death. Sixth, language groups in Quebec may not reflect the diversity of cultures present in other countries, and the extent to which the results generalize to other regions is to be determined. Many Arabic speakers in Quebec originate from the Maghreb, but the Middle East may be a greater source of Arabic-speaking migrants for other countries. Nonetheless, Quebec has the advantage of collecting data on language for all births in the province, an important strength of the study, as the results indicate that language is useful to capture information on subgroups of Arabs at risk of stillbirth.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that the Arabic-speaking population comprises an increasing proportion of births in Quebec. Selected subgroups of Arabic-speaking women, especially those who speak Arabic at home or originate from an Arab country, have a greater risk of stillbirth than French or English speakers. Proportionately more stillbirths among Arabic-speaking women are related to congenital anomalies, termination of pregnancy, and undetermined causes of death. These findings indicate a need to better understand cause of death as it relates to disparities in stillbirth occurrence. Strategies should focus on developing ways to improve stillbirth postmortem evaluations to understand causes of death and develop evidence-based prevention strategies. Future research should address strategies to prevent stillbirth among Arabic speakers in light of the higher prevalence due to congenital anomalies.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by Health Canada through the McGill Training and Retention of Health Professionals Project (3.1/2018-2019/06/01) and the Canadian Congenital Anomalies Surveillance System of the Public Health Agency of Canada (6D02363004). Dr Auger acknowledges career award support from the Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé (34 695).

ORCID iD: Nathalie Auger, MD, MSc  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2412-0459

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2412-0459

References

- 1. Frøen JF, Friberg IK, Lawn JE, et al. Stillbirths: progress and unfinished business. Lancet. 2016;387(10018):574–586. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00818-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ravelli AC, Tromp M, Eskes M, et al. Ethnic differences in stillbirth and early neonatal mortality in the Netherlands. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2011;65(8):696–701. doi:10.1136/jech.2009.095406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartsch E, Park AL, Pulver AJ, Urquia ML, Ray JG. Maternal and paternal birthplace and risk of stillbirth. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(4):314–323. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30281-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reeske A, Kutschmann M, Razum O, Spallek J. Stillbirth differences according to regions of origin: an analysis of the German perinatal database, 2004-2007. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:63 doi:10.1186/1471-2393-11-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Racape J, De Spiegelaere M, Alexander S, Dramaix M, Buekens P, Haelterman E. High perinatal mortality rate among immigrants in Brussels. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(5):536–542. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckq060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spallek J, Lehnhardt J, Reeske A, Razum O, David M. Perinatal outcomes of immigrant women of Turkish, Middle Eastern and North African origin in Berlin, Germany: a comparison of two time periods. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(3):505–512. doi:10.1007/s00404-013-2986-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. El Reda DK, Grigorescu V, Posner SF, Davis-Harrier A. Lower rates of preterm birth in women of Arab ancestry: an epidemiologic paradox—Michigan, 1993-2002. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(6):622–627. doi:10.1007/s10995-007-0199-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kulwicki A, Smiley K, Devine S. Smoking behavior in pregnant Arab Americans. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32(6):363–367. doi:10.1097/01.NMC.0000298132.62655.0d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. El-Sayed AM, Galea S. The health of Arab-Americans living in the United States: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:272 doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Auger N, Park AL, Harper S. Francophone and Anglophone perinatal health: temporal and regional inequalities in a Canadian setting, 1981-2008. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(6):925–934. doi:10.1007/s00038-012-0372-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Auger N, Daniel M, Mortensen L, Toa-Lou C, Costopoulos A. Stillbirth in an Anglophone minority of Canada. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(3):353–362. doi:10.1007/s00038-015-0650-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Statistics Canada. Proportion of mother tongue responses for various regions in Canada, 2016 census. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dv-vd/lang/index-eng.cfm. Published August 4, 2017. Accessed July 4, 2018.

- 13. Dajani G. 750,925 Canadians hail from Arab lands. http://www.canadianarabinstitute.org/publications/reports/750925-canadians-hail-arab-lands. Published June 2014 Accessed July 6, 2018.

- 14. Statistics Canada. Immigrant population by place of birth, period of immigration, 2016 counts, both sexes, age (total), Quebec, 2016 census—25% sample data. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/imm/Table.cfm?&T=21&Geo=24&SO=10D. Published October 25, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2018.

- 15. Gissler M, Alexander S, MacFarlane A, et al. Stillbirths and infant deaths among migrants in industrialized countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(2):134–148. doi:10.1080/00016340802603805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malin M, Gissler M. Maternal care and birth outcomes among ethnic minority women in Finland. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:84 doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ministry of Health and Social Services. Med-Echo System Normative Framework—Maintenance and Use of Data for the Study of Hospital Clientele. Quebec: Government of Quebec; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Government of Quebec. Banque de données des statistiques officielles: definition(s). http://www.bdso.gouv.qc.ca/pls/ken/ken254_clas.page_clas?p_iden_tran=REPER1XNFBH19-18765125015870L(&p_1&p_id_raprt=803#definition . Published 2015. Accessed July 12, 2018.

- 19. Ford C, Harawa NT. A new conceptualization of ethnicity for social epidemiologic and health equity research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(2):251–258. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corbeil JP, Chavez B, Pereira D. Portrait of official-language minorities in Canada—Anglophones in Quebec. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-642-x/89-642-x2010002-eng.pdf?st=XQvSlzwy. Published September 2010 Accessed July 3, 2018.

- 21. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Perinatal Health Report—2008 Edition. Ottawa, Ontario: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Auger N, Denis G. Late pregnancy abortions: an analysis of Québec stillbirth data, 1981-2006. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(2):443–446. doi:10.1007/s00038-011-0313-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393 doi:10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. SAS for Windows [computer program]. Version 9.4 Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gagnon AJ, Zimbeck M, Zeitlin J. Migration to Western industrialised countries and perinatal health: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(6):934–946. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dias SE, Severo M, Barros H. Determinants of health care utilization by immigrants in Portugal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:207 doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dias S, Gama A, Rocha C. Immigrant women’s perceptions and experiences of health care services: insights from a focus group study. J Public Health. 2010;18(5):489–496. doi:10.1007/s10389-010-0326-x [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Eijsden M, van der Wal MF, Bonsel GJ. Folic acid knowledge and use in a multi-ethnic pregnancy cohort: the role of language proficiency. BJOG. 2006;113(12):1446–1451. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01096.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ben Halim N, Ben Alaya Bouafif N, Romdhane L, et al. Consanguinity, endogamy, and genetic disorders in Tunisia. J Community Genet. 2013;4(2):273–284. doi:10.1007/s12687-012-0128-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wright C, Lee RE. Investigating perinatal death: a review of the options when autopsy consent is refused. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89(4):F285–F288. doi:10.1136/adc.2003.022483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Auger N, Tiandrazana R-C, Healy-Profitós J, Costopoulos A. Inequality in fetal autopsy in Canada. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(3):1384–1396. doi:10.1353/hpu.2016.0110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mohammed M, Kharoshah MA. Autopsy in Islam and current practice in Arab Muslim countries. J Forensic Leg Med. 2014;23:80–83. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]