Abstract

Objectives:

From 2017 to 2018, electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use increased 78% among high school students and 48% among middle school students in the United States. However, few e-cigarette prevention interventions have been evaluated. We determined the feasibility and initial effectiveness of “CATCH My Breath,” an e-cigarette prevention program, among a sample of middle schools in central Texas.

Methods:

Twelve middle schools in Texas (6 intervention schools and 6 control schools) participated in the CATCH My Breath pilot program during 2016-2017. CATCH My Breath is rooted in social cognitive theory, consists of 4 interactive in-class modules, and is collaboratively administered via classroom and physical education teachers, student–peer leaders, and social messaging (eg, school posters). We collected 3 waves of data: baseline (January 2017), 4-month follow-up (May 2017), and 16-month follow-up (May 2018). Using school as the unit of analysis, we tested a repeated cross-sectional, condition-by-time interaction on e-cigarette ever use, psychosocial determinants of use, and other tobacco use behaviors. Analyses controlled for school-level sociodemographic characteristics (eg, sex, race/ethnicity, and percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch).

Results:

From baseline to 16-month follow-up, increases in ever e-cigarette use prevalence were significantly lower among intervention schools (2.8%-4.9%) than among control schools (2.7%-8.9%), controlling for covariates (P = .01). Intervention schools also had significantly greater improvements in e-cigarette knowledge (β = 0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.21-1.21; P = .008) and perceived positive outcomes (β = –0.12; 95% CI, –0.23 to –0.02; P = .02) than control schools, controlling for covariates from baseline to 16-month follow-up.

Conclusion:

Ever e-cigarette use was lower among middle schools that implemented the CATCH My Breath program than among those that did not. Replication of findings among a larger sample of schools, using a group-randomized, longitudinal study design and a longer follow-up period, is needed.

Keywords: adolescent health, tobacco, e-cigarettes, prevention, school health

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are devices that allow users to inhale aerosolized chemicals. E-cigarettes comprise 4 components: a battery, a heating element (eg, atomizer), e-liquid (typically containing nicotine, propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and other chemicals), and a cartridge that holds the e-liquid. E-cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product among middle and high school students.1 From 2017 to 2018, e-cigarette use increased 78% among high school students (from 11.7% to 20.8%) and 48% among middle school students (from 3.3% to 4.9%).2 Although research indicates that e-cigarettes are safer than combustible tobacco products,3 adolescent e-cigarette use presents several public health concerns, including nicotine dependence1,3-5 and combustible tobacco initiation.1,3,6-9 Ubiquitous marketing and promotion of e-cigarette devices create a norm that e-cigarettes are desirable and popular, lowering the social risk of using e-cigarettes.1,10-21 Although retailers cannot sell e-cigarettes to minors, these devices are frequently accessed via social means (eg, peers, family members) or directly purchased via online or in-person retailers.22-24 The combination of high prevalence, public health ramifications, and social/environmental reinforcers of adolescent e-cigarette use has resulted in a call to action for e-cigarette prevention programs aimed at adolescents.1,3,5

JUUL is the most used e-cigarette device among young persons, accounting for approximately 70% of the e-cigarette market at convenience stores in 2018.17,25,26 JUUL presents several unique public health concerns relative to other e-cigarette devices. First, JUUL delivers one of the highest doses of nicotine available, at about 59 mg/mL (5.0% weight),27,28 higher than the European Union nonprescription limit of 20 mg/mL (2.0% weight).29 Second, JUUL delivers nicotine 1.3-2.7 times faster than competing e-cigarette products, making JUUL users more vulnerable to nicotine addiction than users of other e-cigarette devices that deliver less nicotine.27,28 Numerous copy-cat products have entered the marketplace with even higher doses of nicotine than JUUL, leading to what has been described as the “nicotine arms race” (ie, competition to achieve the highest rates of nicotine delivery among e-cigarette products).26

A 2012 US Surgeon General report concluded that coordinated, multicomponent interventions are effective in reducing combustible tobacco initiation and use among adolescents, in the presence of supporting community environments.30 School-based programs are an important part of multicomponent prevention strategies.30-32 A meta-analysis of school-based smoking prevention trials from 2006-2014 found an average 12% reduction in smoking incidence during a 12-month span.31 To our knowledge, no empirically tested e-cigarette interventions among adolescents exist33; however, evidence suggests social competence and social influence approaches may be transferable to e-cigarette prevention.34

In 2015, researchers at the University of Texas School of Public Health developed the “CATCH My Breath” e-cigarette prevention program. Because evidence-based programs to prevent e-cigarette use are not available, the development of CATCH My Breath was guided by strategies used for the prevention of adolescent cigarette smoking. CATCH My Breath used a multicomponent framework (ie, combined social competence and social influences) for school-based tobacco prevention programs.30-32 The objective of this study was to determine the feasibility and initial effectiveness of CATCH My Breath in preventing e-cigarette use initiation (ie, ever use) among a sample of middle school students in central Texas.

Methods

Beginning in January 2017, researchers at the University of Texas School of Public Health conducted a pilot test of CATCH My Breath. CATCH My Breath is a school-based program rooted in social cognitive theory and designed to prevent e-cigarette use initiation among middle school students. We conducted a pilot test of CATCH My Breath in 12 middle schools in central Texas. We used a pretest–posttest, serial cross-sectional design to determine the effects of CATCH My Breath on reducing e-cigarette use behaviors among sixth-grade students from January 2017 (ie, baseline) to May 2018 (ie, 16-month follow-up). The University of Texas Institutional Review Board and school district research offices reviewed and approved all study objectives and protocols.

Development of CATCH My Breath

Although e-cigarettes are regulated as tobacco products,35,36 several factors led to the creation of an explicit e-cigarette prevention program rather than an amendment of an existing tobacco prevention program. Most tobacco prevention programs highlight the long-term health consequences of using combustible cigarettes30-32; however, the long-term health consequences of e-cigarette use are unknown.1,3 E-cigarette prevention programs must use strategies and messages that differ from those used for combustible cigarette prevention programs because e-cigarettes pose fewer health consequences (with the exception of nicotine dependence) than combustible tobacco products (eg, cigarettes, cigars/cigarillos, hookahs/water pipes) and smokeless tobacco products.1,3 In addition, whereas flavors for combustible cigarettes are restricted to menthol,35,36 an estimated 7700 e-cigarette flavors exist.37 Because flavored tobacco is popular with adolescents,19-21,38-44 education about flavors must be highlighted differently for e-cigarettes than for combustible cigarettes. Finally, although television advertising of combustible cigarettes has been banned since 1971, no such regulations exist for e-cigarettes,1,35,36 resulting in the marketing of e-cigarettes via traditional (eg, print, television) and new social media channels with high rates of viewership among young persons.1,10-16 Thus, e-cigarette prevention programs must address the unique characteristics and marketing of e-cigarettes.

CATCH My Breath was informed by theoretical perspectives of social cognitive theory,45,46 evidence-based strategies from tobacco prevention programs,30-32 and risk-factor data from recent research on e-cigarettes.1,47-51 Social cognitive theory posits that behavior is shaped by the interaction of environmental factors (eg, peer role models, health messaging, social reinforcement) and intrapersonal factors (eg, outcome expectations).45,46 Fostering of social competence and refusal skills is an important element of smoking prevention programs in schools.30-32,45,46

In 2015, researchers at the University of Texas School of Public Health began developing CATCH My Breath with the aim of influencing the psychosocial determinants of e-cigarette susceptibility, initiation, and sustained use. Researchers relied on more than 40 years of empirical evidence to apply practical, theoretical, and empirical underpinnings of tobacco prevention research.30-32 Before testing the feasibility and effectiveness of CATCH My Breath, we conducted a needs assessment survey among middle school teachers and established a community advisory board comprising tobacco prevention practitioners and school district health education managers. We designed CATCH My Breath to be easy for teachers to implement, fit into existing class schedules, and serve either as a stand-alone program or as individual modules that can be inserted into an existing tobacco prevention program.

Feasibility Test of CATCH My Breath

We conducted a feasibility test of CATCH My Breath in spring 2016 to determine the program’s strengths and areas for improvement. We conducted the feasibility test among 26 middle schools in 7 states and included participants in sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. Forty-two teachers and 2255 middle school students provided feedback on CATCH My Breath, including the following 9 suggestions: (1) reduce the number of lessons from 6 to 4; (2) create grade-specific, sequential learning activities; (3) reduce lesson length to 25 minutes; (4) create school posters that reinforce messaging; (5) reinforce harms of combustible tobacco use; (6) produce PowerPoint slides for each lesson; (7) replace the teacher’s manual with a user-friendly online portal; (8) train teachers via webinar; and (9) create companion activities for physical education classes that reinforce the messaging.

Applying Feedback From the Feasibility Test

Based on feedback from the feasibility test, we made the following changes to CATCH My Breath: (1) reduced the number of lessons from 6 to 4; (2) created grade-specific content with differing activities and lessons for sixth-grade classrooms, relative to seventh- and eighth-grade classrooms; (3) streamlined content so that lessons lasted no longer than 25 minutes; (4) designed promotional posters for in-school display that incorporated social messaging informed by social cognitive theory and school-based tobacco interventions, with the aim of reducing social norms of e-cigarette use30-32; (5) expanded the knowledge components of CATCH My Breath to include the negative health effects of using combustible cigarettes and other tobacco products; (6) developed PowerPoint presentations for each lesson; (7) put all program materials (eg, teacher manuals) on a user-friendly online portal; (8) developed webinar trainings for teachers that were available through the online portal; and (9) developed companion physical education activities based in movement-oriented games and activities that reinforced the CATCH My Breath classroom lessons.

Components of CATCH My Breath

CATCH My Breath features 6 activities taught via 4 classroom lessons; each lesson lasts about 25 minutes. First, students are educated (via group discussion) on the contents of e-cigarettes, the short-term health consequences of e-cigarette use (eg, nicotine dependence), and school policies and age-of-sale restrictions. Second, students compare their expectations of peers’ e-cigarette use with data on e-cigarette prevalence, thereby discovering (or reinforcing) that e-cigarette use is not a normative behavior for middle school students. Third, reasons or motivations for e-cigarette use are explored and positive alternatives to achieve these goals are discussed. Fourth, students learn how these reasons or motivations are established through social (eg, peer/adult role models) and environmental (eg, product marketing) influences. Students then analyze real-world e-cigarette advertisements and mock social situations in small groups to identify social and environmental influences on e-cigarette use in the students’ school and community. Fifth, students learn and practice refusal skills to resist social influences to use e-cigarettes and role-play possible social encounters. Sixth, students make a public commitment to abstain from e-cigarette use.

All CATCH My Breath lessons are led by classroom teachers who are trained via webinar to implement the program. All program activities are designed to require active participation led by trained peer facilitators (ie, student leaders). These peer facilitators are elected by their classmates and trained to organize cooperative group discussion activities. Peer facilitators practice facilitating group activities with their teachers in a brief 30-minute session before curriculum implementation. Classroom teachers ensure preparedness of each peer facilitator and routinely check in with peer facilitators to address any issues that may arise.

Pilot Test of CATCH My Breath

A pilot test of CATCH My Breath took place from January 2017 through May 2018. We collected 3 waves of data during the pilot test: January 2017 (baseline), May 2017 (4-month follow-up), and May 2018 (16-month follow-up). We collected baseline data before CATCH My Breath classroom lessons were taught. We collected data at baseline and at 4-month follow-up among sixth-grade students. We collected data at 16-month follow-up among seventh-grade students. Because baseline surveys were anonymous, the follow-up surveys asked students to identify whether they had taken the survey the previous year in sixth grade.

A convenience sample of 19 public schools in central Texas were invited and agreed to participant in the pilot study. Participating schools in the intervention group implemented CATCH My Breath in sixth-grade classes in spring. Participating schools in the control group implemented the required tobacco education lessons mandated by the State of Texas Education Code and State Board of Education (ie, “usual care”).

Although 19 schools initially agreed to participate at baseline, we excluded 7 schools from the analysis to ensure comparability on sociodemographic variables at baseline. We excluded 4 schools because the seventh-grade assessment (ie, 16-month follow-up) was not administered, and we excluded 3 schools because a disproportionately high percentage of students (90%) were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (ie, were economically disadvantaged). Given the strong correlation between economic disadvantage and e-cigarette use behaviors,34 these 3 schools were excluded from analysis to eliminate potential confounding. We included 12 schools in the final analyses: 6 intervention schools and 6 control schools.

Teachers in schools that implemented CATCH My Breath (ie, intervention schools) were trained via a 1-hour webinar designed by the CATCH Global Foundation and available through the online portal. The webinar covered knowledge of e-cigarettes, activities used in CATCH My Breath, and how to access program materials through the CATCH.org online digital platform. Teachers also reviewed the 4 lessons and accompanying PowerPoint slides during this training.

Measures and Data Collection

We administered a brief questionnaire that assessed knowledge and attitudes toward e-cigarettes, susceptibility to e-cigarette use, ever and 30-day e-cigarette use, ever and past 30-day combustible tobacco use, race/ethnicity, and sex.

We determined susceptibility to using e-cigarettes by adapting a validated measure of cigarette smoking susceptibility shown to predict future smoking.52-54 Students were asked if they were curious about using e-cigarettes, if they had thought about using an e-cigarette in the next year, and if they would use an e-cigarette if their best friend offered them one. Possible responses were definitely not, probably not, probably yes, and definitely yes. Students responding “definitely not” to all 3 questions were considered not susceptible; all others were considered susceptible.

We assessed ever and past 30-day e-cigarette use by adapting a question from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) survey that assessed frequency of e-cigarette use.55 To determine ever use, we asked students, “Have you ever used an e-cigarette, even 1 or 2 puffs?” To determine past 30-day e-cigarette use, we asked students, “During the past 30 days, have you used an e-cigarette?”

We measured knowledge by using an 11-item scale related to content delivered in the classroom lessons, with scores corresponding to the number of questions answered correctly (0-11). We developed psychosocial variables based on research that demonstrates the need for product-specific measures of attitudes and perceptions toward tobacco products.56,57 We examined attitudes toward e-cigarettes by asking 6 questions. Exploratory factor analyses revealed 2 unique factors among the 6 variables on attitudes: perceived positive outcomes (ie, self-evaluations of likely consequences of behavior) and subjective norms (ie, perceived prevalence of a behavior). Four items loaded to the construct for perceived positive outcomes (α = .85). To assess perceived positive outcomes, we asked students how much they agreed with the following statements about e-cigarettes: (1) “I would enjoy using e-cigarettes,” (2) “Using e-cigarettes would help me to deal with problems or stress,” (3) “Using e-cigarettes would help me make new friends,” and (4) “Using e-cigarettes would help me wake up and feel energized.” Two items loaded to the construct for subjective norms (α = .67). To assess subjective norms, we asked students how much they agreed with the following statements about e-cigarettes: (1) “Most kids my age use e-cigarettes” and (2) “Most kids in high school use e-cigarettes.” Responses ranged from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree).

We also examined 2 behaviors on combustible tobacco use from the 2017 YRBSS survey.55 To determine ever combustible tobacco use, we asked students, “Have you ever smoked a cigarette, or any other kind of tobacco like a cigar or pipe, even 1 or 2 puffs?” To determine past 30-day combustible tobacco use, we asked students, “During the past 30 days, have you smoked a cigarette or any other kind of tobacco?”

We also assessed school-level covariates. We collected data on sample size and percentage of females at each wave, and we collected data on percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, percentage of African American students, and percentage of Hispanic/Latino students only at baseline. We administered the baseline survey in January 2017, the first posttest survey in May 2017 (4-month follow-up), and the final posttest survey in May 2018 (16-month follow-up). We administered surveys during physical education classes.

Statistical Analysis

Before evaluating the effectiveness of CATCH My Breath, we conducted an attrition analysis to account for possible selection bias through school exclusion. We conducted 2-tailed t tests to determine whether the 12 schools included in the analysis differed significantly from the 7 schools that were excluded from analysis on all baseline variables. We found 1 significant difference between included schools and excluded schools: excluded schools differed significantly from included schools in percentage of students enrolled in bilingual and English as a Second Language programs (26.7% vs 10.2%; P = .02).

This study used a quasi-experimental cross-sectional design, which offers the greatest protection against type II error (ie, false positive) compared with analysis at the student (ie, individual) level.58,59 In these designs, intact groups (eg, schools) are matched according to sociodemographic characteristics (eg, percentage of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch, racial/ethnic composition) from within the intervention and control schools. We created a time variable to classify data based on the time of assessment: baseline, 4-month follow-up, and 16-month follow-up. We excluded students who were new to their school in seventh grade. We accounted for the school component of variance (ie, participants in a single school tend to be more like each other than they are like participants in other schools) by modeling an individual’s e-cigarette smoking status as the outcome and included school as a nested random effect.

We tested the intervention effect at each wave of data using a condition × time interaction against the school variance. Linear regression models examining the condition × time interaction controlled for all covariates. We conducted all analyses by using Stata version 14.2.60

Results

We found minimal sociodemographic differences between intervention schools and control schools (Table 1). However, intervention schools had significantly more participants than control schools (mean number of participants: 318.0 vs 105.7; P = .004).

Table 1.

School-level characteristics of the CATCH My Breath e-cigarette prevention program, at intervention and control schools, Texas, January 2017a

| Characteristic | Control Schools (n = 6)b | Intervention Schools (n = 6)b | t Test (P Value)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch | 33.1% | 29.4% | t 10 = 0.36 (.73) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 5.6% | 8.8% | t 10 = –1.34 (.21) |

| Hispanic | 41.6% | 32.4% | t 10 = 1.10 (.30) |

| Enrolled in English as a Second Language course | 8.9% | 11.6% | t 10 = –0.87 (.41) |

| Female | 40.9% | 49.4% | t 10 = –1.81 (.10) |

| Mean no. of participants per school | 105.7 | 318.0 | t 10 = –5.21 (.004) |

| E-cigarette use among students | |||

| Ever e-cigarette use | 2.7% | 2.8% | t 10 = –0.12 (.91) |

| Past 30-day e-cigarette use | 1.5% | 0.8% | t 10 = 1.06 (.32) |

| Susceptible to using e-cigarettesd among never users | 42.7% | 34.2% | t 10 = 1.60 (.14) |

| Tobacco use among students | |||

| Ever tobacco use | 3.7% | 2.9% | t 10 = 0.50 (.63) |

| Past 30-day tobacco use | 0.4% | 0.6% | t 10 = –0.45 (.66) |

| Knowledge and attitudes toward e-cigarettes | |||

| Knowledge, scoree | 7.14 | 7.23 | t 10 = –0.32 (.76) |

| Perceived positive outcomesf for not using e-cigarettes, scoreg | 1.26 | 1.20 | t 10 = 1.09 (.30) |

| Subjective norms,g scoreg | 1.91 | 1.70 | t 10 = 2.27 (.047) |

Abbreviation: e-cigarette, electronic cigarette.

a CATCH My Breath is a school-based program rooted in social cognitive theory and designed to prevent e-cigarette use behaviors (eg, initiation, sustained use) among middle school students. Schools are the unit of analysis for this program. Schools are divided into treatment conditions (ie, intervention schools received CATCH My Breath, control schools did not).

b Data reflect the mean prevalence or value within control schools and intervention schools.

c t tests were used to examine significant differences between control and intervention schools. P = .05 was considered significant.

d Students were asked if they were curious about using e-cigarettes, if they had thought about using an e-cigarette in the next year, and if they would use an e-cigarette if their best friend offered them one. Students were classified as not susceptible if they responded “definitely not” to all 3 questions. Students were classified as susceptible if they responded “probably not,” “probably yes,” or “definitely yes” to 1 or more questions.

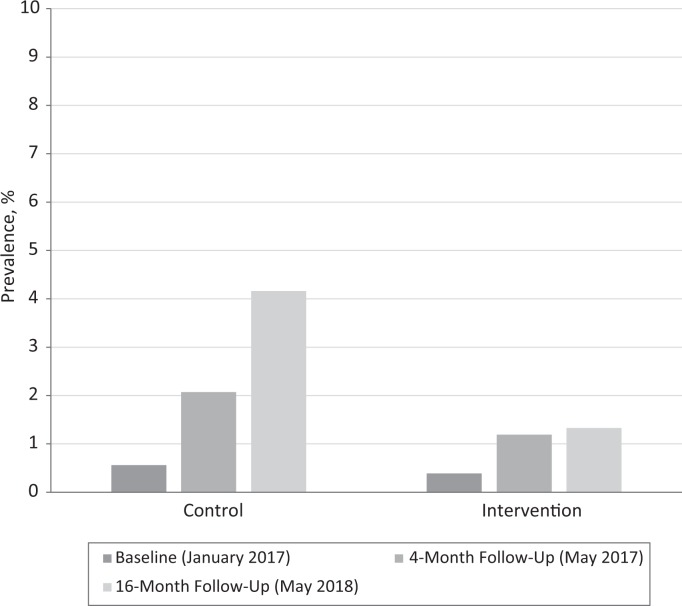

From baseline to 16-month follow-up, ever e-cigarette use increased 6.2% among control schools (from 2.7% to 8.9%; P = .003) and 2.1% among intervention schools (from 2.8% to 4.9%; P = .33; Figure 1). At 16-month follow-up, 45% fewer students in the intervention schools than in the control schools reported ever using e-cigarettes (4.9% vs 8.9%; P = .09). From baseline to 16-month follow-up, the prevalence of past 30-day use of combustible tobacco increased significantly among control schools (from 0.6% to 4.2%, P = .002) but not among intervention schools (from 0.4% to 1.3%, P = .13; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

School-level prevalence of ever electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use among central Texas schools receiving the CATCH My Breath e-cigarette prevention program (intervention schools, n = 6) and those not receiving the program (control schools, n = 6), January 2017–May 2018. The P value reflects a bivariate analysis (t test) comparing school-level e-cigarette prevalence at baseline and 16-month follow-up, stratified by intervention schools and control schools.

Figure 2.

School-level prevalence of past 30-day electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use among central Texas schools receiving the CATCH My Breath e-cigarette prevention program (intervention schools, n = 6) and those not receiving the program (control schools, n = 6), January 2017–May 2018. The P value reflects a bivariate analysis (t test) comparing school-level e-cigarette prevalence at baseline and 16-month follow-up, stratified by intervention schools and control schools.

Intervention schools had significant improvements in e-cigarette knowledge (β = .71; 95% CI, 0.21-1.21; P = .01) and perceived positive outcomes for not using e-cigarettes (β = –0.12; 95% CI, –0.23 to –0.02; P = .02) from baseline to 16-month follow-up, controlling for covariates (Table 2). Intervention status had no significant effect on subjective norms. Susceptibility to e-cigarette use from baseline to 16-month follow-up dropped considerably although not significantly in intervention schools (β = –0.09; 95% CI, –0.11 to –0.01; P = .08).

Table 2.

Changes in school-level e-cigarette knowledge, perceived positive outcomes, and subjective norms at intervention and control schools during the CATCH My Breath e-cigarette prevention program, Texas, 2017-2018a

| Characteristic | 4-mo Follow-upb | 16-mo Follow-upb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI)c | P Valued | β (95% CI) | P Valued | |

| Knowledgee | 0.81 (0.32 to 1.30) | .002 | 0.71 (0.21 to 1.21) | .01 |

| Perceived positive outcomesf for not using e-cigarettes | 0.02 (–0.08 to 0.12) | .73 | –0.12 (–0.23 to –0.02) | .02 |

| Subjective normsg | 0.03 (–0.06 to 0.21) | .41 | –0.09 (–0.33 to 0.16) | .46 |

| Ever e-cigarette use | –0.01 (–0.06 to 0.03) | .41 | –0.06 (–0.11 to –0.02) | .01 |

| Past 30-day e-cigarette use | 0 (–0.03 to 0.02) | .81 | –0.01 (–0.03 to 0.01) | .11 |

| Susceptibility of using e-cigarettes among never usersh | –0.04 (–0.12 to 0.01) | .35 | –0.09 (–0.11 to –0.01) | .08 |

| Ever combustible tobacco usei | –0.02 (–0.05 to 0.04) | .34 | –0.05 (–0.10 to –0.01) | .76 |

| Past 30-day combustible tobacco usei | –0.01 (–0.03 to 0.01) | .34 | –0.04 (–0.06 to –0.02) | .001 |

Abbreviation: e-cigarette, electronic cigarette.

a CATCH My Breath is a school-based program rooted in social cognitive theory and designed to prevent e-cigarette use behaviors (eg, initiation, sustained use) among middle school students. Schools are the unit of analysis for this program. Schools are divided into intervention schools (ie, received CATCH My Breath, n = 6) and control schools (implemented the required tobacco education lessons mandated by the State of Texas Education Code and State Board of Education, n = 6).

b Linear regression models examining the intervention × time interaction. Intervention was coded as a binary variable: intervention schools were coded as 1, and control schools were coded as 0. Time was coded as a categorical variable, with 3 waves of data collection: January 2017 (ie, baseline; coded as 0), May 2017 (ie, 4-month follow-up; coded as 1), and May 2018 (ie, 16-month follow-up; coded as 2). Tests were considered significant at P = .05.

c All linear regression models controlled for percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, percentage of students who were non-Hispanic black, percentage of students who were Hispanic/Latino, and percentage of students enrolled in English as a Second Language courses at baseline, as well as school-level sample size and percentage female enrollment at each wave of data collection.

d P < .05 was considered significant.

e Measured by using an 11-item scale related to content delivered in classroom lessons, with scores corresponding to the number of questions answered correctly (0-11).

f Perceived positive outcomes were conceptualized as the self-evaluation of likely consequences of behavior and were assessed via the following 4 items: (1) “I would enjoy using e-cigarettes,” (2) “Using e-cigarettes would help me to deal with problems or stress,” (3) “Using e-cigarettes would help me make new friends,” and (4) “Using e-cigarettes would help me wake up and feel energized.” Responses ranged from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree). Scores were calculated as means of all 4 items, measured continuously. Minimum and maximum values ranged from 0-4.

g Subjective norms were conceptualized as perceived prevalence of a behavior and were assessed via the following 2 items: (1) “Most kids my age use e-cigarettes” and (2) “Most kids in high school use e-cigarettes.” Responses ranged from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree). Scores were calculated as means of both items, measured continuously. Minimum and maximum values ranged from 0-4.

h Determined by adapting a validated measure of cigarette smoking susceptibility.29 Students were asked if they were curious about using e-cigarettes, if they had thought about using an e-cigarette in the next year, and if they would use an e-cigarette if their best friend offered them one. Students were classified as not susceptible if they responded “definitely not” to all 3 questions. Students were classified as susceptible if they responded “probably not,” “probably yes,” or “definitely yes” to 1 or more questions.

i Combustible tobacco products included cigarettes or any other kind of tobacco (eg, cigar or pipe), even 1 or 2 puffs.

Rates of ever using e-cigarettes decreased significantly from baseline to 16-month follow-up among intervention schools (β = –0.06; 95% CI, –0.11 to –0.02; P = .01), controlling for covariates (Table 2). Similarly, rates of past 30-day combustible tobacco use decreased significantly from baseline to 16-month follow-up among intervention schools (β = –0.04; 95% CI, –0.06 to –0.02; P < .001), controlling for covariates.

Discussion

To our knowledge, CATCH My Breath is the first e-cigarette prevention program to be developed, implemented, and evaluated in the United States.33 This study found that the program had positive effects on preventing ever e-cigarette use among middle school students in central Texas. Furthermore, CATCH My Breath, which is rooted in social cognitive theory, was found to significantly improve key psychosocial determinants of e-cigarette use behavior (eg, e-cigarette knowledge and perceived positive outcomes). As such, the presented findings provide preliminary support for the effectiveness of CATCH My Breath.

Our findings have substantial implications. The US Surgeon General and the National Academy of Sciences recognized the need for e-cigarette prevention strategies tailored to adolescents.1,3 However, a recent review of interventions aimed at e-cigarette use behaviors found that most programs were not product specific (ie, embedded in existing tobacco control programs) and had insufficient evidence of success or effectiveness.33 Thus, to our knowledge, CATCH My Breath is the only evidence-based e-cigarette prevention program with demonstrated effectiveness for middle school students. As such, study findings may inform public health educators and practitioners in their efforts to address the increase in adolescent e-cigarette use.

This study also found positive effects of CATCH My Breath on reducing past 30-day combustible tobacco product use. This finding is notable given that approximately 40% of adolescent tobacco users report using more than 1 product (ie, dual/poly use).2 Although CATCH My Breath primarily focuses on e-cigarettes, this program also reinforces student intention to resist other forms of tobacco. Findings could be the result of a generalized effect based on increased awareness of the harmful consequences of all forms of tobacco use, training in resistance skills, and tobacco media literacy activities offered in the program.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, because the study used a quasi-experimental design and lacked randomization, we could not rule out selection bias. However, the selected study design (nested serial cross-sectional design) is widely accepted in evaluating quasi-experimental school-based interventions and has been shown to reduce type II error.58,59 Second, the study relied on measures of e-cigarette perceptions and expectations by using modified assessments that were specific to combustible cigarettes. This limitation presents potential psychometric issues (eg, construct validity) because perceptions and expectations vary substantially by product type and in relation to conventional cigarettes.55-57 However, until psychometrically validated measures of e-cigarette behavior, expectations, and perceptions are available,56,57 the effect of e-cigarette interventions cannot be comprehensively examined.

Conclusion

CATCH My Breath has been updated every year since 2016, and schools using the program have requested elementary and high school versions of the program. The high school version was written in 2019, and plans are underway for development of the elementary school version. The program is being disseminated nationally by CVS Pharmacy, Discovery Education, and the CATCH Global Foundation. Although this analysis found positive intervention effects from a pilot test of CATCH My Breath, replication using more sophisticated research methods is needed. To replicate and establish a stronger evidence base, the National Cancer Institute began a formal randomized controlled trial of CATCH My Breath in May 2019, and results are expected in 2023.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank our partner central Texas school districts, schools, and students for participating in this study. We also gratefully acknowledge Cheryl Perry, PhD, Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Texas School of Public Health, for her insightful and constructive comments of earlier drafts of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by an opportunity grant from the St. David’s Foundation.

ORCID iD: Dale S. Mantey, MPA  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1122-4849

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1122-4849

References

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, et al. Vital signs: tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(6):157–164. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Case KR, Mantey DS, Creamer MR, Harrell MB, Kelder SH, Perry CL. E-cigarette-specific symptoms of nicotine dependence among Texas adolescents. Addict Behav. 2018;84:57–61. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on new enforcement actions and a youth tobacco prevention plan to stop youth use of, and access to, JUUL and other e-cigarettes [news release]. Washington, DC: US Food and Drug Administration; April 23, 2018 https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm605432.htm. Accessed May 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watkins SL, Glantz SA, Chaffee BW. Association of noncigarette tobacco product use with future cigarette smoking among youth in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013-2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(2):181–187. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hammond D, Reid JL, Cole AG, Leatherdale ST. Electronic cigarette use and smoking initiation among youth: a longitudinal cohort study. CMAJ. 2017;189(4f3):E1328–E1336. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goldenson NI, Leventhal AM, Stone MD, McConnell RS, Barrington-Trimis JL. Associations of electronic cigarette nicotine concentration with subsequent cigarette smoking and vaping levels in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(12):1192–1199. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lozano P, Barrientos-Gutierrez I, Arillo-Santillan E, et al. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use and onset of conventional cigarette smoking and marijuana use among Mexican adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:427–430. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mantey DS, Cooper MR, Clendennen SL, Pasch KE, Perry CL. E-cigarette marketing exposure is associated with e-cigarette use among US youth. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(6):686–690. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mantey DS, Creamer MR, Pasch KE, Perry CL. Marketing exposure recall is associated with past 30-day single, dual, polytobacco use among US adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(suppl 1):S55–S61. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Fagan P, Unger JB, Stacy AW. E-cigarette advertising exposure, explicit and implicit harm perceptions, and e-cigarette use susceptibility among nonsmoking young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(1):127–131. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fallin-Bennett A, Aleshire M, Scott T, Lee YO. Marketing of e-cigarettes to vulnerable populations: an emerging social justice issue. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;55(4):584–591. doi:10.1111/ppc.12366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen-Sankey JC, Unger JB, Bansal-Travers M, Niederdeppe J, Bernat E, Choi K. E-cigarette marketing exposure and subsequent experimentation among youth and young adults. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20191119 doi:10.1542/peds.2019-1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phua J. E-cigarette marketing on social networking sites: effects on attitudes, behavioral control, intention to quit, and self-efficacy. J Advertising Res. 2019;59(2):242–254. doi:10.2501/JAR-2018-018 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Unger JB, Bartsch L. Exposure to tobacco websites: associations with cigarette and e-cigarette use and susceptibility among adolescents. Addict Behav. 2018;78:120–123. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, et al. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control. 2019;28(2):146–151. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirkpatrick MG, Cruz TB, Unger JB, Herrera J, Schiff S, Allem JP. Cartoon-based e-cigarette marketing: associations with susceptibility to use and perceived expectations of use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:109–114. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Case KR, Harrell MB, Pérez A, et al. The relationships between sensation seeking and a spectrum of e-cigarette use behaviors: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses specific to Texas adolescents. Addict Behav. 2017;73:151–157. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harrell MB, Loukas A, Jackson CD, Marti CN, Perry CL. Flavored tobacco product use among youth and young adults: what if flavors didn’t exist? Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(2):168–173. doi:10.1800/TRS.3.2.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harrell MB, Weaver SR, Loukas A, et al. Flavored e-cigarette use: characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep. 2016;5:33–40. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mantey DS, Barroso CS, Kelder BT, Kelder SH. Retail access to e-cigarettes and frequency of e-cigarette use in high school students. Tob Regul Sci. 2019;5(3):280–290. doi:10.18001/TRS.5.3.6 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pepper JK, Coats EM, Nonnemaker JM, Loomis BR. How do adolescents get their e-cigarettes and other electronic vaping devices? Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(3):420–429. doi:10.1177/0890117118790366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Laestadius L, Wang Y. Youth access to JUUL online: eBay sales of JUUL prior to and following FDA action. Tob Control. 2019;28(6):617–622. doi:10/1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen A. Teenagers embrace JUUL, saying it’s discreet enough to vape in class. National Public Radio. December 4, 2017 https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/12/04/568273801/teenagers-embrace-juul-saying-its-discreet-enough-to-vape-in-class. Accessed November 4, 2019.

- 26. Kavuluru R, Han S, Hahn EJ. On the popularity of the USB flash drive-shaped electronic cigarette JUUL. Tob Control. 2019;28(1):110–112. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goniewicz ML, Boykan R, Messina CR, Eliscu A, Tolentino J. High exposure to nicotine among adolescents who use JUUL and other vape pod systems (‘pods’). Tob Control. 2019;28(6):676–677. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jackler RK, Ramamurthi D. Nicotine arms race: JUUL and the high-nicotine product market. Tob Control. 2019;28:623–628. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bertollini R, Ribeiro S, Mauer-Stender K, Galea G. Tobacco control in Europe: a policy review. Eur Respir Rev. 2016;25(140):151–157. doi:10.1183/16000617.0021-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. US Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thomas RE, McLellan J, Perera R. Effectiveness of school-based smoking prevention curricula: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e006976 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas RE, McLellan J, Perera R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(4):CD001293 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001293.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. O’Connor S, Pelletier H, Bayoumy D, Schwartz R. Interventions to Prevent Harms From Vaping. Toronto, Canada: Ontario Tobacco Research Unit; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Springer AE, Davis C, Van Dusen D, et al. School socioeconomic disparities in e-cigarette susceptibility and use among central Texas middle school students. Prev Med Rep. 2018;11:105–108. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. US Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products: final rule. Fed Regist. 2016;81(90):28973–29106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Berman ML, Yang YT. E-cigarettes, youth, and the US Food and Drug Administration’s “deeming” regulation. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(11):1039–1040. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu SH, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control. 2014;23(suppl 3):iii3–iii9. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mantey DS, Omega-Njemnobi O, Montgomery L. Flavored tobacco use is associated with dual and poly tobacco use among adolescents. Addict Behav. 2019;93:269–273. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cooper M, Harrell MB, Pérez A, Delk J, Perry CL. Flavorings and perceived harm and addictiveness of e-cigarettes among youth. Tob Regul Sci. 2016;2(3):278–289. doi:10.18001/TRS.2.3.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Villanti AC, Johnson AL, Ambrose BK, et al. Flavored tobacco product use in youth and adults: findings from the first wave of the PATH study (2013-2014). Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(2):139–151. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cullen KA, Liu ST, Bernat JK, et al. Flavored tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2014-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(39):839–844. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6839a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dai H. Single, dual, and poly use of flavored tobacco products among youths. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:170389 doi:10.5888/pcd15.170389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dai H. Changes in flavored tobacco product use among current youth tobacco users in the United States, 2014-2017. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(3):282–284. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goldenson NI, Leventhal AM, Simpson KA, Barrington-Trimis JL. A review of the use and appeal of flavored electronic cigarettes. Curr Addict Rep. 2019;6(2):98–113. doi:10.1007/s40429-019-00244-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kelder SH, Hoelscher D, Perry CL. How individuals, environments, and health behaviors interact In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath eds. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2015:159–182. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kelder SH, Hoelscher DM, Shegog R. Social cognitive theory applied to health and risk messaging In: Parrott RL, ed. Oxford Encyclopedia of Health and Risk Message Design and Processing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.259 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Perry CL, Creamer MR, Chaffee BW, et al. Research on youth and young adult tobacco use, 2013-2018, from the Food and Drug Administration–National Institutes of Health Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science [published online April 23, 2019]. Nicotine Tob Res. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntz059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cooper M, Creamer MR, Ly C, Crook B, Harrell MB, Perry CL. Social norms, perceptions and dual/poly tobacco use among Texas youth. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40(6):761–770. doi:10.5993/AJHB.40.6.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roditis M, Delucchi K, Cash D, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ perceptions of health risks, social risks, and benefits differ across tobacco products. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(5):558–566. doi:10.1016/j.adohealth.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gorukanti A, Delucchi K, Ling P, Fisher-Travis R, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ attitudes towards e-cigarette ingredients, safety, addictive properties, social norms, and regulation. Prev Med. 2017;94:65–71. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. El-Toukhy S, Choi K. Smoking-related beliefs and susceptibility among United States youth nonsmokers. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(4):448–450. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Merritt RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15(5):355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Unger JB, Johnson CA, Stoddard JL, Nezami E, Chou CP. Identification of adolescents at risk for smoking initiation: validation of a measure of susceptibility. Addict Behav. 1997;22(1):81–91. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(95)00107-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bold KW, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. E-cigarette susceptibility as a predictor of youth initiation of e-cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;20(1):140–144. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntw393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(SS-8):1–114. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weaver SR, Kim H, Glasser AM, et al. Establishing consensus on survey measures for electronic nicotine and non-nicotine delivery system use: current challenges and considerations for researchers. Addict Behav. 2018;79:203–212. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gibson LA, Creamer MR, Breland AB, et al. Measuring perceptions related to e-cigarettes: important principles and next steps to enhance study validity. Addict Behav. 2018;79:219–225. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Murray DM, Varnell SP, Blitstein JL. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials: a review of recent methodological developments. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):423–432. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.3.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Murray DM. Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials. Vol 29: Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stata [computer software]. Release 14 College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2015. [Google Scholar]