The blood concentration of isoniazid (INH) is evidently affected by polymorphisms in N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), an enzyme that is primarily responsible for the trimodal (i.e., fast, intermediate, and slow) INH elimination. The pharmacokinetic (PK) variability, driven largely by NAT2 activity, creates a challenge for the deployment of a uniform INH dosage in tuberculosis (TB) patients.

KEYWORDS: population pharmacokinetics, isoniazid, tuberculosis, NAT2, China

ABSTRACT

The blood concentration of isoniazid (INH) is evidently affected by polymorphisms in N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), an enzyme that is primarily responsible for the trimodal (i.e., fast, intermediate, and slow) INH elimination. The pharmacokinetic (PK) variability, driven largely by NAT2 activity, creates a challenge for the deployment of a uniform INH dosage in tuberculosis (TB) patients. Although acetylator-specific INH dosing has long been suggested, well-recognized dosages according to acetylator status remain elusive. In this study, 175 blood samples were collected from 89 pulmonary TB patients within 0.5 to 6 h after morning INH administration. According to their NAT2 genotypes, 32 (36.0%), 38 (42.7%), and 19 (21.3%) were fast, intermediate, and slow acetylators, respectively. The plasma INH concentration was detected by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Population pharmacokinetic (PPK) analysis was conducted using NONMEM and R software. A two-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination well described the PK parameters of isoniazid. Body weight and acetylator status significantly affected the INH clearance rate. The dosage simulation targeting three indicators, including the well-recognized efficacy-safety indicator maximum concentration in serum (Cmax; 3 to 6 μg/ml), the reported area under the concentration-time curve from 0 h to infinity (AUC0–∞; ≥10.52 μg·h/ml), and the 2-h INH serum concentrations (≥2.19 μg/ml), was associated with the strongest early bactericidal activity. The optimal dosages targeting the different indicators varied from 700 to 900 mg/day, 500 to 600 mg/day, and 300 mg/day for the rapid, intermediate, and slow acetylators, respectively. Furthermore, a PPK model for isoniazid among Chinese tuberculosis patients was established for the first time and suggested doses of approximately 800 mg/day, 500 mg/day, and 300 mg/day for fast, intermediate, and slow acetylators, respectively, after a trade-off between efficacy and the occurrence of side effects.

TEXT

Tuberculosis (TB) is a leading infectious disease that caused an estimated 10 million new cases and 1.3 million deaths in 2017 (1). Despite the availability of potent anti-TB drugs, treatment failure and unfavorable outcomes are frequently confronted. Multiple studies have proved that the variable therapeutic drug concentration is a key factor in the discrepant treatment outcomes as well as for adverse reactions. Isoniazid (INH), the backbone of the first-line anti-TB treatment regimen, harbors the most potent early bactericidal activity (EBA) among the known anti-TB drugs. Variance in plasma concentrations of up to 3 to 7 times was observed in patients administered the standard isoniazid dosage (2), which highlights the value of individualized dosing.

INH is mainly metabolized by N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), which demonstrates diverse interindividual variability in acetylating activities. Individuals can be classified as rapid, intermediate, or slow acetylators according to their NAT2 gene polymorphisms (3). Previous studies have demonstrated that rapid acetylators have plasma exposures significantly lower than the presumed effective and safe concentration range of 3 to 6 mg/liter, which could be an important cause of treatment failure (4). Although slow acetylators can easily achieve the effective exposure, they have an increased risk of adverse reactions (5). The pharmacokinetic (PK) variability, driven largely by NAT2 polymorphisms, creates a challenge for the deployment of a uniform INH dose for different TB patients. The distribution of NAT2 polymorphisms is highly diverse among various populations. In contrast to the high percentage of slow acetylators among Western populations, a higher percentage of the Chinese population are rapid acetylators. This status reinforces the requirement for a rapid NAT2 genotyping test and, accordingly, the administration of an increased INH dosage in China.

Population pharmacokinetic (PPK) analysis is a well-established method that can quantify and explain the variability in drug concentrations among individuals (6). In contrast to the traditional pharmacokinetic (PK) assay, blood samples can be collected at flexible time points postdosing for PPK analysis, which not only makes it easy to be performed but also avoids the bias caused by sampling at fixed times. The PPK assay is routinely performed nowadays to propose an appropriate dosage for new drugs. A recent study conducted with 33 healthy Asians revealed that the derived metabolic phenotypes for NAT2 were a significant covariate of INH clearance (CL) (7). Similarly, another study categorized the subjects into two subgroups (rapid and slow acetylators) according to the INH metabolism speed, which reiterated the important effect of NAT2 gene polymorphisms on CL, the apparent elimination rate constant (K), and the median elimination half-life (t1/2) (8). Although multiple studies were performed to demonstrate the importance of the NAT2 genotype on INH metabolism, they were either performed among healthy individuals, used only two subgroups, or used only a single INH dose. Furthermore, no specific dosage has yet been proposed according to the trimodal acetylator phenotype based on the PPK among tuberculosis patients. Therefore, we aimed to address these important issues in this study with Chinese tuberculosis patients.

RESULTS

Enrolled patient information.

A total 89 patients were recruited from March to August 2018. Among these patients, 59 were male; the median age and weight were 44 years (range, 16 to 72 years) and 58 kg (range, 35 to 100 kg), respectively; and 32 (36.0%), 38 (42.7%), and 19 (21.3%) patients were fast, intermediate, and slow acetylators, respectively. A summary of the patient characteristics is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 89 pulmonary tuberculosis patients

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Median (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 42.9 (15.6) | 44.0 (16.0–72.0) |

| Wt (kg) | 60.0 (12.3) | 58.0 (35.0–100) |

| Ht (cm) | 169 (7.36) | 170 (153–185) |

| Serum creatinine concn (μmol/liter) | 59.5 (15.9) | 60.9 (32.9–124) |

| Urea nitrogen concn (U/liter) | 8.65 (43.3) | 3.86 (1.05–412) |

| Alanine aminotransferase concn (U/liter) | 15.7 (14.3) | 12.0 (3.00–95.0) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase concn (U/liter) | 24.5 (19.4) | 19.0 (7.00–160) |

| Alkaline phosphatase concn (U/liter) | 85.9 (43.0) | 79 (37.0–392) |

| INH treatment | ||

| Duration (days) | 8.97 (7.56) | 7 (7.00–64.0) |

| Dose (mg/dose) | 317 (62.6) | 300 (300–600) |

PPK model establishment.

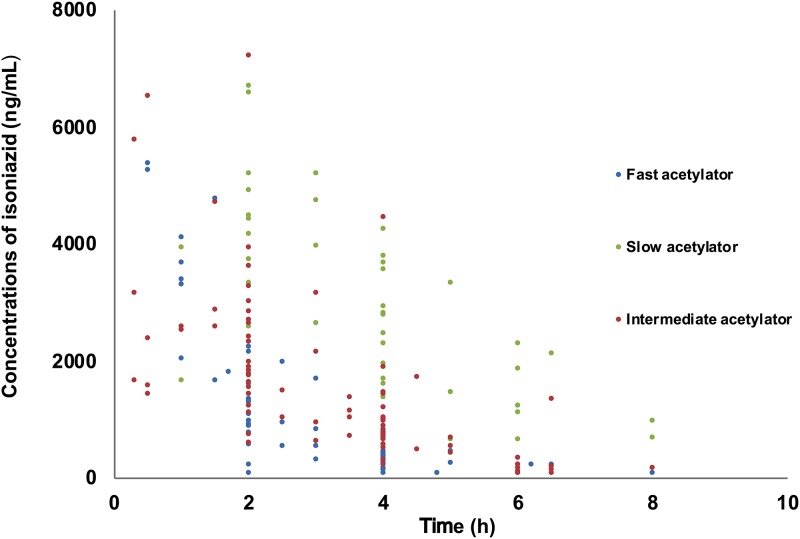

Only 1 patient provided one sample, 71 patients provided two samples, 16 patients provided three samples, and 1 patient provided four samples. Subsequently, a total of 195 INH concentrations from 89 patients were analyzed for the PPK model. The INH concentrations in the pharmacokinetic and scavenged samples ranged from 0.1 to 7.2 mg/liter. A total of 12 concentrations were below the limit of quantitation (LOQ) and were censored and replaced by a constant value of 50 ng/ml, i.e., a value of half the LOQ in PPK analyses. The concentration-versus-time profile is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG 1.

Isoniazid concentrations versus time.

Oral absorption of the two-compartment model fitted the data. The objective function value (OFV) and residual variability of the two-compartment model were lower than those of the one-compartment model (OFV = 2,690 versus 2,713). The model was parameterized in terms of the central volume of distribution (V1/F), peripheral volume of distribution (V2/F), intercompartmental clearance (Q/F), clearance (CL/F), and absorption rate constant (Ka) of INH. Interindividual variability was best described by an exponential model and was then estimated for CL/F, Q/F, and Ka. An exponential model best described the residual variability.

Covariate analysis.

Weight had a significant influence on clearance, with a drop in the OFV of 13.41 units. The NAT2 metabolic genotype was identified to be the most important covariate on CL, associated with a drop in the OFV of 84.08 units. Other covariates were implemented, but no further decrease in the OFV was observed.

Table 2 summarizes the parameter estimates of the final pharmacokinetic model. The median estimated weight-normalized CL/F and volume distribution at steady state (the sum of V1/F and V2/F) were 0.56 liter/h/kg (range, 0.15 to 1.11 liter/h/kg) and 0.84 liter/kg (range, 0.49 to 1.40 liters/kg), respectively. The CL/F in fast, intermediate, and slow eliminators were 42.7 liters/h, 31.4 liters/h, and 11.9 liters/h, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Population PK parameters of INH and bootstrap analysis resultsa

| Parameter | Full data set |

Bootstrap analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final estimate | RSE (%) | Median | 5th–95th percentile | |

| CL/F (liters/h) (intermediate acetylators) | ||||

| CL/F = θ1× FCW × FNAT2 | ||||

| θ1 | 31.4 | 6.60 | 31.1 | 24.7–37.6 |

| V1/F (liters) | ||||

| V1/F = θ2 | ||||

| θ2 | 21.1 | 26.1 | 20.1 | 3.01–47.2 |

| V2/F (liters) | ||||

| V2/F = θ3 | ||||

| θ3 | 27.7 | 19.2 | 28.3 | 7.52–47.5 |

| Q/F (liters/h) | ||||

| Q/F = θ4 | ||||

| θ4 | 43.7 | 39.1 | 43.2 | 11.9–228 |

| Ka | ||||

| Ka = θ5 | ||||

| θ5 | 1.70 | 25.8 | 1.81 | 1.09–5.82 |

| Fcw = (CW/58)θ6 | ||||

| θ6 | 0.930 | 21.0 | 0.929 | 0.311–1.45 |

| FNAT2 | ||||

| Fast acetylator on CL/F | 1.36 | 8.20 | 1.34 | 1.05–1.69 |

| Slow acetylator on CL/F | 0.378 | 8.70 | 0.379 | 0.289–0.496 |

| Interindividual variability (%) | ||||

| CL/F | 25.6 | 18.1 | 24.5 | 17.3–33.3 |

| Q/F | 63.8 | 53.7 | 67.8 | 7.61–170 |

| Ka/F | 75.8 | 44.5 | 66.3 | 22.6–122 |

| Residual variability (%) | 25.1 | 24.8 | 24.4 | 14.3–22.1 |

CL, clearance; V1, central volume of distribution; V2, peripheral volume of distribution; Q, intercompartment clearance; CW, current weight (in grams); Ka, absorption rate constant. In our population, 58 kg and 44 years were the median current weight and postnatal age values, respectively.

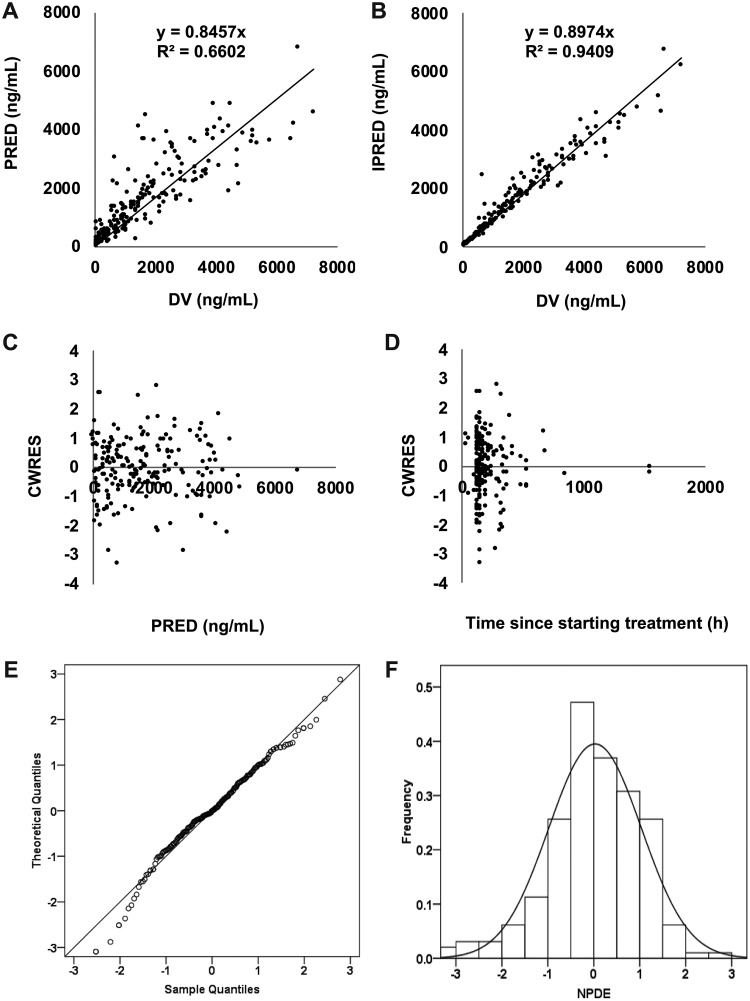

Model evaluation.

Model diagnostics showed an acceptable goodness of fit for the final model of INH. A prediction-corrected visual predictive check (pc-VPC), shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material, indicated a good predictive performance of the developed model. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, predictions were unbiased. In the diagnostic plots of conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus time and population prediction (PRED), no trends were observed (Fig. 2C and D). In addition, the median parameter estimates resulting from the bootstrap procedure closely agreed with the respective values from the final population model, indicating that the final model is stable and can redetermine the estimates of the population pharmacokinetic parameters (Table 2). The normalized prediction distribution errors (NPDEs) are presented in Fig. 2E and F, which show that the distribution and histogram of NPDEs met the theoretical N(0,1) distribution and density well, therefore indicating a good fit of the model to the individual data. The mean and variance of the NPDEs were 0.027 (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 0.411) and 1.02 (Fisher variance test, P = 0.821), respectively.

FIG 2.

Model evaluation for isoniazid. (A) Population prediction (PRED) versus observed (DV) concentration; (B) individual prediction (IPRED) versus DV concentration; (C) CWRES versus PRED; (D) conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus time; (E) QQ plot of the distribution of the normalized prediction distribution errors (NPDE) versus the theoretical N(0,1) distribution; (F) histogram of the distribution of the NPDE.

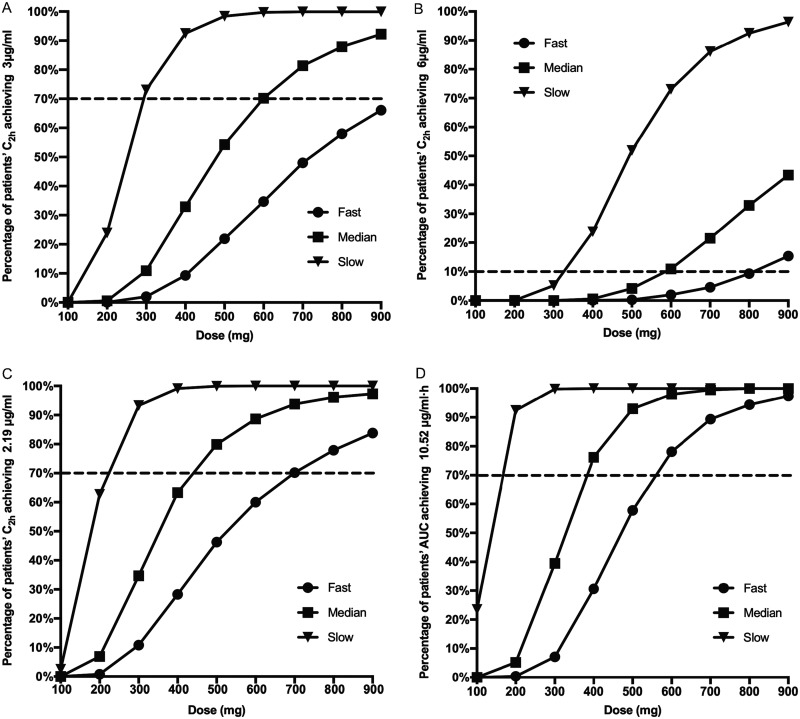

Figure 3 shows the dosage simulation for effective and safe plasma exposures.

FIG 3.

INH dosage simulation targeting different indicators over different dosages. (A) Rate at which a C2h of ≥3 μg/ml was reached; (B) rate at which a C2h of ≥6 μg/ml was reached; (C) rate at which a C2h of ≥2.19 μg/ml was reached; (D) rate at which an AUC0–∞ of ≥10.52 μg·h/ml was reached.

Dosage simulation.

The dosage simulation was performed with weight-based or fixed-dose strategies. The two dosing strategies did not have a significant difference (Fig. S2). In addition, as the isoniazid tablet is 100 mg, it is convenient to use a fixed dose in clinical practice. Therefore, here we present the outcomes only for the fixed dose.

A well-recognized optimal maximum serum concentration (Cmax) of INH ranging from 3 to 6 μg/ml was targeted (5). For fast acetylators, even by using 900 mg/day (equivalently to 10 mg/kg of body weight), only 66.1% of the patients achieved the lowest pursued concentration (Fig. 3A). However, a 600-mg/day dosage for the intermediate acetylators resulted in a 3-μg/ml blood concentration in 70.2% of cases, while the corresponding percentage for slow acetylators was 73.1% at a 300-mg/day dosage. On the other hand, a concentration of over 6 μg/ml should be used with caution and the patients should be monitored to avoid side effects. The dosage simulation demonstrated that ∼5% of fast, intermediate, and slow acetylators can have Cmaxs above 6 μg/ml by receiving 700 mg/day, 500 mg/day, and 300 mg/day, respectively. Furthermore, this percentage can increase to 15.4% and 10.9% for intermediate and slow acetylators, respectively, using dosages of 900 mg/day and 600 mg/day, respectively (Fig. 3D).

Two other assessment indicators adopted from a study analyzing the maximum EBA were also utilized (9). In this study, patients with an area under the concentration-time curve from 0 h to infinity (AUC0–∞) of ≥10.52 μg·h/ml or serum concentrations at 2 h postdosing (C2h) of ≥2.19 μg/ml could achieve ≥90% of the maximum EBA for INH. The rates for reaching the targeted indicators came to plateaus for rapid, intermediate, and slow acetylators when 900-, 600-, and 300-mg dosages per day, respectively, were simulated, while 700-mg/day, 500-mg/day, and 300-mg/day dosages for rapid, intermediate, and slow acetylators, respectively, resulted in a C2h of ≥2.19 μg/ml in 70.2%, 79.9%, and 93.3% of the patients, respectively (Fig. 3B and C).

DISCUSSION

We report here for the first time the PPK parameters of isoniazid among Chinese pulmonary tuberculosis patients determined by integrating the results for the three NAT2 metabolic genotypes. A two-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination well described the PK parameters of isoniazid in this assay. This finding is consistent with previously reported isoniazid PK model results (7–8). In this model, body weight was a significant factor affecting the INH clearance rate, and the OFV decreased by 13.41 units. The other demographic covariates included in this assay did not have significant effects on the PK parameters. Other studies have drawn controversial conclusions on the effects of gender. In the present study, there was no significant difference in body fat ratio between males and females.

Consistent with the findings of other studies, the NAT2 metabolic genotype was identified to be the most important covariate on CL/F, and the OFV decreased by 84.08 units in our study. Among the 89 pulmonary TB patients, the respective proportions of fast, intermediate, and slow acetylators were 36.0% (n = 32), 42.7% (n = 38), and 21.3% (n = 19), consistent with the findings of another Chinese study (10). Other studies identified a higher percentage of slow acetylators (40% to 70%) among Caucasians, whereas higher numbers of fast acetylators were reported among South Africans (23.4% to 74.3%) (11, 12). These discrepancies within regions and races highlight the variable influence of the NAT2 polymorphism on TB patient care, while they also reiterate the need for rapid NAT2 genotype identification before INH administration. Although body weight and NAT2 genotypes were the significant factors explaining variability, a lot of variability still remains unexplained. Therefore, multiple factors that were not among those evaluated in the present study are required to be investigated in the future.

In our study, the CL/F values for fast, intermediate, and slow acetylators were 42.7 liters/h, 31.4 liters/h, and 11.9 liters/h, respectively. The CL/F in the fast acetylators was about 1.4 and 3.6 times faster than those in the intermediate and slow acetylators, respectively. This result is basically consistent with the CL/F of 50 liters/h for the fast acetylators and 15 liters/h for the slow acetylators in the study by Peloquin et al. (8). In another study with healthy volunteers, the CL/F of fast acetylators was 1.9 and 7.7 times faster than those of the intermediate and slow acetylators, respectively (7), while in a study involving tuberculosis patients in eastern Africa, the CL/F of fast and slow acetylators were 26.1 and 15.5 liters/h, respectively (13). These results show that, in addition to the polymorphism of the NAT2 genotype, other genetic factors might also affect the metabolism of isoniazid between ethnic groups and require further exploration.

Dose simulations were performed by use of the final model to calculate the proportion of the population achieving the default pharmacodynamically effective and safe Cmax (3 to 6 μg/ml). These targets are based on concentrations that are usually achieved in patients who undergo successful treatment. Using the regular dosage (i.e., 300 mg/day), up to 98% of fast acetylators, 89.1% of intermediate acetylators, and only 26.9% of slow acetylators acquired Cmax values less than 3 μg/ml. By increasing the dosage 2 or 3 times of the regular dosage for intermediate and slow acetylators, the proportion of patients who achieved the minimum Cmax threshold dramatically increased. However, 15.4% and 10.9% of the intermediate and slow acetylators, respectively, receiving the 900-mg/day and 600-mg/day dosages, respectively, had Cmax values that surpassed the safe concentration of 6 μg/ml. Since fast acetylators rapidly metabolize INH, the side effects associated with the acquisition of a Cmax of over 6 μg/ml in a short time require further studies.

A study in which 90% of the subjects achieved the maximum EBA highlighted that the patients with an area under the concentration-time curve from 0 h to infinity (AUC0–∞) of ≥10.52 μg·h/ml or a serum concentration at 2 h of ≥2.19 μg/ml were able to achieve the goal (10). They also found that at a 6-mg/kg dose, several fast acetylators could not achieve the INH AUC0–∞ and INH serum concentrations at 2 h associated with the EBA standard, although all the slow acetylators could achieve it with the 3-mg/kg dosage. It is well documented that fast acetylators can achieve better drug exposure with higher dosages, whereas low plasma levels are associated with treatment failure and drug resistance (14). Multiple studies reported that the side effects are closely related to the slow acetylators (odds ratio, 1.9 to 4.7) (2, 15) and recommended that the dose for slow acetylators be reduced to lower the risk of hepatotoxicity (16, 17). One study suggested that for fast, intermediate, and slow acetylators, the INH dose can be adjusted to 7.5 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, and 2.5 mg/kg, respectively, to achieve similar INH exposures, which were equivalent to 450, 300, and 150 mg/day, respectively, for patients with an average body weight (∼60 kg) (2). Our dosage simulation demonstrated that these dosages are far from enough. Based on our outcomes, not only fast acetylators but also intermediate acetylators need to increase their INH dosage to pursue better treatment outcomes, while the 300-mg/day dosage seems appropriate for slow acetylators. In general, dosages of about 800 mg/day, 500 mg/day, and 300 mg/day might be optimal for fast, intermediate, and slow acetylators, respectively, after the trade-off between efficacy and side effects.

High-dose INH administration is at least partially justified by the WHO recommendation on the treatment of patients with multidrug-resistant (MDR) rifampin-resistant TB. The recommended dosage is 10 to 15 mg/kg/day, which is equivalent to 600 mg/day to 900 mg/day for a person with an average body weight (∼60 kg). However, a systematic evaluation of high-dose INH has never been well performed. High-dose isoniazid was associated with treatment success among children with confirmed MDR TB, and on this basis, its use in adults was extrapolated. WHO guidelines presumed that patients with different isoniazid resistance genotypes (e.g., katG versus inhA mutations) might benefit differently from high-dose INH, while specific studies on this hypothesis are scarce.

Although the model built in this study well describes the variability and covariates among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, there are still some limitations. First, the dosage prediction is highly dependent on the targeting indicators. In this study, we applied the most recognized 3- to 6-μg/ml Cmax range, an AUC0–∞ of ≥10.52 μg·h/ml, and a C2h of ≥2.19 μg/ml as target values for dosage imitations. The dearth of an authoritative standard target is a barrier to dosage adjustment according to acetylator status. Second, the predicted dosages for different acetylators are based on a mathematical model, and it does not account for oral bioavailability and the interindividual variability of isoniazid. Therefore, more pharmacodynamic (PD) studies and clinical trials are needed to justify these dosages. Third, the relevance and applicability of this PPK model cannot be easily generalized because the susceptibility to Mycobacterium tuberculosis may vary over time, between countries, and between patient profiles. Lastly, a major weakness of the present work is the lack of a PD perspective. The opinions on the increased INH dosage and its effects are paradoxical. Some studies found that an increased INH dose would result in a limited efficacy increase when the bacilli have low INH MICs, even in fast acetylators. Other researchers suggest that increasing the dose may be necessary only in the case of infections with low-level INH resistance. However, a clinical trial reported that an increased dosage for rapid acetylators could increase the successful treatment rate (9). Overall, currently, clinical trials and the PK/PD studies are not enough to address explicitly the high dosage and its efficacy among patients infected with either INH-sensitive or INH-resistant strains.

In conclusion, we combined the NAT2 genotype to establish a PPK model for isoniazid among Chinese tuberculosis patients, in which the NAT2 genotype and body weight had significant effects on isoniazid clearance. According to our study, the routinely used INH dosages for intermediate and fast acetylators are far from enough. Our PPK model suggests 900-, 600-, and 300-mg/day dosages for fast, intermediate, and slow acetylators, respectively. Our simulations suggest that tailoring the INH dose to NAT2 metabolism status may be necessary and is expected to result in an improved balance between risk and benefit upon treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

The trial was a prospective, open-label population pharmacokinetic study of INH conducted with pulmonary tuberculosis patients in the Beijing Chest Hospital, Beijing, China. The study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the hospital (reference no. 2017-05-01). Written informed consent was obtained from all the recruited patients.

Patient inclusion criteria included (i) a diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis, (ii) inclusion of isoniazid in the treatment regimen, (iii) age 18 years or older, (iv) no serious underlying diseases, and (v) no pregnancy. Patient exclusion criteria were (i) hypersensitivity or intolerance to isoniazid and (ii) the presence of a severe comorbidity. The demographic characteristics of each patient and the laboratory examination outcomes for each patient were collected.

Dosing regimen and blood sampling.

An INH dosage of 300 or 600 mg/day was administered orally (once in the morning on an empty stomach) according to the physician’s prescription. After INH had been used for more than 1 week and the drug concentration supposedly reached a steady state, blood samples were drawn within 0.5 to 6 h postdosing and stored in EDTA-containing tubes. Blood was centrifuged within an hour at 3,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and plasma was collected and stored at −80°C.

INH detection by LC-MS/MS.

The liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system consisted of an Agilent 1240 high-performance liquid chromatograph equipped with a cooled autosampler connected to an Agilent 6400 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). Chromatographic separations were achieved using a Zorbax SB-Aq column (50 mm by 4.6 mm; particle size, 5 μm; Agilent) with gradient elution. Mobile phases A and B were 5 mM ammonium acetate and 90% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in water containing 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid, respectively. The flow rate was 0.3 ml/min. Serial dilution was used to obtain linear calibration ranges for INH (100 to 10,000 ng/ml). The method has been validated according to U.S. FDA guidance for industry on bioanalytical method validation. Methanol and acetaminophen, used as an internal standard (IS), were added to the plasma separated from the blood samples, and the components were mixed thoroughly. After 15 min of further centrifuging, 50 μl supernatant was used for drug detection.

NAT2 genotyping.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood samples using a BloodGen minikit (Zeesan Biotech Co., Xiamen, China). A multicolor melting curve analysis (MMCA) method (Zeesan Biotech Co., Xiamen, China) analyzing the four most common single nucleotide polymorphism sites, including C.341T>C, C.481C>T, C.590G>A, and C.857G>A, was applied for NAT2 genotype identification (18). Twenty-five microliters of template DNA was added into the tube containing the PCR master mix and 2 U Taq polymerase. The PCR and melting curve analysis were performed on a LightCycler 480 instrument. The genotype of NAT2 was defined according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Population pharmacokinetic modeling of INH.

Pharmacokinetic analysis was carried out using the nonlinear mixed effects modeling program NONMEM (v7.2; Icon Development Solutions, USA). The first-order conditional estimation (FOCE) method with interaction was used to estimate the pharmacokinetic parameters and their variability. The interindividual variability of the pharmacokinetic parameters was estimated using an exponential model and was expressed as follows: , where θi represents the parameter value for the ith subject, θmedian is the typical value of the parameter in the population, and ηi is the variability between subjects, which is assumed to follow a normal distribution with a mean of zero and a variance of ω2.

Covariate analysis followed a forward and backward selection process. The likelihood ratio was used to test the effect of each variable on the model parameters. The effects of weight, height, postnatal age, gender, acetylator type, and serum creatinine concentration, urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentration, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) concentration, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) concentration (in blood collected within ≤48 h of pharmacokinetic sampling) were investigated as potential variables affecting the pharmacokinetic parameters. During the first step of covariate model building, a covariate was included if a significant (P < 0.05, χ2 distribution with 1 degree of freedom) decrease (reduction > 3.84) in the objective function value (OFV) from the basic model as well as a reduction in the variability of the pharmacokinetic parameter was obtained. All the significant covariates were then added simultaneously into a full model. Subsequently, each covariate was independently removed from the full model. If the increase in the OFV was higher than 6.635 (P < 0.01, χ2 distribution), the covariate was considered significantly correlated with the pharmacokinetic parameter and was therefore retained in the final model.

Model validation was based on graphical and statistical criteria. Goodness-of-fit plots, including the observed value (DV) versus the population prediction (PRED), DV versus the individual prediction (IPRED), conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus time, and CWRES versus PRED, were initially used for diagnostic purposes. The stability and performance of the final model were also assessed by means of a nonparametric bootstrap analysis with resampling and replacement. One thousand data sets were simulated using the final population model parameters. NPDE results were summarized graphically by default, as provided by the NPDE R package (v1.2): (i) a quantile-quantile (QQ) plot of NPDE and (ii) a histogram of the NPDE. The NPDE is expected to follow an N(0,1) distribution.

Based on the final population pharmacokinetic model and previous studies, we simulated the optimal INH exposure according to different acetylator groups. Both weight-based and fixed-dose strategies were applied. The dosage simulation was on a milligram-per-day basis. Monte Carlo simulations were performed using the parameter estimates obtained from the final model. The original data set was simulated 100 times. The original patients were used in the simulation cohort in order to ensure a similar distribution of population characteristics. The virtual patient was administered the evaluated dosing regimen of 100 to 900 mg/day.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81672065), the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (grant Z181100001718092), the National Science and Technology Major Project (grants 2017ZX09304009, 2017ZX10201301-004-002, 2018ZX10302301-004, and 2018ZX10302302), the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’ Ascent Plan (grant DFL20181602), and the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (grant ZYLX201809).

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Word Health Organization. 2018. Global tuberculosis report 2018. Word Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinzig-Schippers M, Tomalik-Scharte D, Jetter A, Scheidel B, Jakob V, Rodamer M, Cascorbi I, Doroshyenko O, Sörgel F, Fuhr U. 2005. Should we use N-acetyltransferase type 2 genotyping to personalize isoniazid doses? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:1733–1738. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1733-1738.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolt HM, Selinski S, Dannappel D, Blaszkewicz M, Golka K. 2005. Re-investigation of the concordance of human NAT2 phenotypes and genotypes. Arch Toxicol 79:196–200. doi: 10.1007/s00204-004-0622-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azuma J, Ohno M, Kubota R, Yokota S, Nagai T, Tsuyuguchi K, Okuda Y, Takashima T, Kamimura S, Fujio Y, Kawase I, Pharmacogenetics-Based Tuberculosis Therapy Research Group. 2013. NAT2 genotype guided regimen reduces isoniazid-induced liver injury and early treatment failure in the 6-month four-drug standard treatment of tuberculosis: a randomized controlled trial for pharmacogenetics-based therapy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69:1091–1101. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1429-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsultan A, Peloquin CA. 2014. Therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of tuberculosis: an update. Drugs 74:839–854. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheiner LB. 1984. The population approach to pharmacokinetic data analysis: rationale and standard data analysis methods. Drug Metab Rev 15:153–171. doi: 10.3109/03602538409015063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seng KY, Hee KH, Soon GH, Chew N, Khoo SH, Lee LS. 2015. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of isoniazid, acetylisoniazid, and isonicotinic acid in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6791–6799. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01244-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peloquin GA, Jaresko GS, Yong CL, Keung AC, Bulpitt AE, Jelliffe RW. 1997. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:2670–2679. doi: 10.1128/AAC.41.12.2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donald PR, Parkin DP, Seifart HI, Schaaf HS, van Helden PD, Werely CJ, Sirgel FA, Venter A, Maritz JS. 2007. The influence of dose and N-acetyltransferase-2 (NAT2) genotype and phenotype on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of isoniazid. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 63:633–639. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen B, Li JH, Huang J, Cao XM. 2004. One-step allele amplification for genotyping of NAT2 in Chinese subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 20:49–52. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-6821.2004.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donald PR, Sirgel FA, Venter A, Parkin DP, Seifart HI, van de Wal BW, Werely C, van Helden PD, Maritz JS. 2004. The influence of human N-acetyltransferase genotype on the early bactericidal activity of isoniazid. Clin Infect Dis 39:1425–1430. doi: 10.1086/424999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loktionov A, Moore W, Spencer SP, Vorster H, Nell T, O'Neill IK, Bingham SA, Cummings JH. 2002. Differences in N-acetylation genotypes between Caucasians and black South Africans: implications for cancer prevention. Cancer Detect Prev 26:15–22. doi: 10.1016/S0361-090X(02)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denti P, Jeremiah K, Chigutsa E, Faurholt-Jepsen D, PrayGod G, Range N, Castel S, Wiesner L, Hagen CM, Christiansen M, Changalucha J, McIlleron H, Friis H, Andersen AB. 2015. Pharmacokinetics of isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol in newly diagnosed pulmonary TB patients in Tanzania. PLoS One 10:e0141002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiner M, Burman W, Vernon A, Benator D, Peloquin CA, Khan A, Weis S, King B, Shah N, Hodge T, Tuberculosis Trails Consortium. 2003. Low isoniazid concentrations and outcome of tuberculosis treatment with once-weekly isoniazid and rifapentine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167:1341–1347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-951OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiratsuka M, Kishikawa Y, Takekuma Y, Matsuura M, Narahara K, Inoue T, Hamdy SI, Endo N, Goto J, Mizugaki M. 2002. Genotyping of the N-acetyltransferase polymorphism in the prediction of adverse reactions to isoniazid in Japanese patients. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 17:357–362. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.17.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pea F, Milaneschi R, Baraldo M, Talmassons G, Furlanut M. 1999. Isoniazid and its hydrazine metabolite in patients with tuberculosis. Clin Drug Invest 17:145–154. doi: 10.2165/00044011-199917020-00009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cojutti P, Duranti S, Isola M, Baraldo M, Viale P, Bassetti M, Pea F. 2016. Might isoniazid plasma exposure be a valuable predictor of drug-related hepatotoxicity risk among adult patients with TB? J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1323–1329. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Y, Chen S, Yu X, Dai G, Dong L, Li Y, Zhao L, Huang H. 2016. Rapid identification of the NAT2 genotype in tuberculosis patients by multicolor melting curve analysis. Pharmacogenomics 60:1211–1215. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2016-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.