Data on the effectiveness of ceftazidime-avibactam (CAZ-AVI) in critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients are limited. The present retrospective observational cohort study, which was conducted in two general intensive care units (ICUs) in central Greece, compared critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients suffering from carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections receiving CAZ-AVI to patients who received appropriate available antibiotic therapy.

KEYWORDS: ceftazidime-avibactam, critically ill, infections, mechanically ventilated, survival

ABSTRACT

Data on the effectiveness of ceftazidime-avibactam (CAZ-AVI) in critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients are limited. The present retrospective observational cohort study, which was conducted in two general intensive care units (ICUs) in central Greece, compared critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients suffering from carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections receiving CAZ-AVI to patients who received appropriate available antibiotic therapy. Clinical and microbiological outcomes and safety issues were evaluated. A secondary analysis in patients with bloodstream infections (BSIs) was conducted. Forty-one patients that received CAZ-AVI (the CAZ-AVI group) were compared to 36 patients that received antibiotics other than CAZ-AVI (the control group). There was a significant improvement in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score on days 4 and 10 in the CAZ-AVI group compared to that in the control group (P = 0.006, and P = 0.003, respectively). Microbiological eradication was accomplished in 33/35 (94.3%) patients in the CAZ-AVI group and 21/31 (67.7%) patients in the control group (P = 0.021), and clinical cure was observed in 33/41 (80.5%) versus 19/36 (52.8%) patients (P = 0.010), respectively. The results were similar in the BSI subgroups for both outcomes (P = 0.038 and P = 0.014, respectively). The 28-day survival was 85.4% in the CAZ-AVI group and 61.1% in the control group (log-rank test = 0.035), while there were 2 and 12 relapses in the CAZ-AVI and control groups, respectively (P = 0.042). A CAZ-AVI-containing regime was an independent predictor of survival and clinical cure (odds ratio [OR] = 5.575 and P = 0.012 and OR = 5.125 and P = 0.004, respectively), as was illness severity. No significant side effects were recorded. In conclusion, a CAZ-AVI-containing regime was more effective than other available antibiotic agents for the treatment of CRE infections in the high-risk, mechanically ventilated ICU population evaluated.

INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) strains have spread worldwide (1). The dissemination of the specific pathogens has been facilitated by the production of carbapenemases, most commonly produced by Klebsiella pneumoniae (1). Carbapenemases are carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases that confer resistance to a broad spectrum of β-lactam substrates, including carbapenems. The Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC; Ambler class A) is one of the five major carbapenemase families; the others are Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase (VIM), imipenemase (IMP), and New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases (NDM) (Ambler class B) and the OXA-48-group carbapenemases (Ambler class D) (2, 3).

Only a few antibiotics are currently active against carbapenem-resistant pathogens. Colistin in combination with aminoglycosides, tigecycline, and fosfomycin has been used as the treatment of last resort, yet the emergence of resistance to the aforementioned agents has further complicated the management of the specific infections (4). A novel antibiotic (β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor) combination, ceftazidime-avibactam (CAZ-AVI), was developed in response to the need for novel antibiotics to fight the increasing rates of infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria (3).

Infections in intensive care units (ICUs) are associated with increased mortality, morbidity, length of stay, and cost of treatment (5). Treating infections in critically ill patients may become a real challenge, considering the changes in the pharmacokinetics of the antimicrobials due to the increased volume of distribution, hypoalbuminemia, and the daily changes in creatinine clearance in such patients (6). Furthermore, antimicrobial resistance is linked to an increased risk of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy, which is related to increasing rates of in-hospital mortality (5). To our knowledge, there are scarce and inconsistent data regarding the utility of CAZ-AVI in the treatment of life-threatening infections in intensive care unit (ICU) patients, especially those that receive mechanical ventilation. This retrospective study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the newly addressed agent CAZ-AVI for the treatment of mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients presenting with infections due to carbapenem-resistant pathogens.

RESULTS

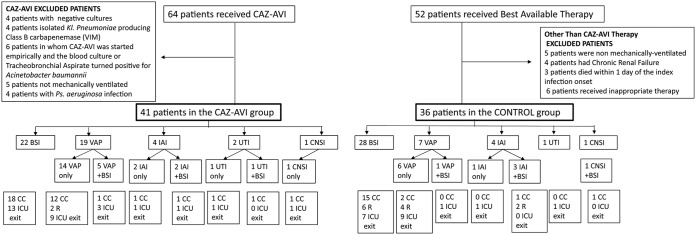

Seventy-seven patients were eligible for this study, and among them, 41 patients (29 from the University Hospital of Larissa ICU [Larissa ICU] and 12 from the General Hospital of Lamia ICU [Lamia ICU]) received CAZ-AVI and consisted of the CAZ-AVI group. The remaining 36 patients (26 from the Larissa ICU and 10 from the Lamia ICU) with carbapenem-resistant infections were included in the control group. A flowchart of the patients included in the study is presented in Fig. 1. The two groups did not differ in their baseline characteristics or in the type or severity of the index infection (presence of shock, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA] score) (Table 1; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Flowchart of the patients included in the study. The BSI subgroups also included all the patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia, intra-abdominal infection, central nervous system, and urinary tract infection with accompanying BSI. CAZ-AVI, ceftazidime-avibactam; BSI, bloodstream infection; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia; UTI, urinary tract infection; IAI, intra-abdominal infection; CNSI, central nervous system infection; CC, clinical cure; R, relapse infection.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics and severity of infectiona

| Characteristic | Value for patients in the following groupsb: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAZ-AVI group (n = 41) | CAZ-AVI BSI subgroup (n = 22) | Control group (n = 36) | Control BSI subgroup (n = 28) | |

| Mean ± SEM age (yr) | 61.92 ± 2.36 | 62.82 ± 3.24 | 59.11 ± 2.74 | 57.07 ± 3.04 |

| No. (%) of male patients | 28 (68.3) | 15 (68.2) | 28 (77.78) | 19 (67.85) |

| No. (%) of patients admitted for surgery | 17 (41.5) | 8 (36.4) | 23 (63.89) | 15 (53.57) |

| Mean ± SEM value for: | ||||

| APACHE II score (admission) | 19.11 ± 1.08 | 18.86 ± 1.21 | 18.5 ± 1.24 | 18.53 ± 1.38 |

| SOFA score (admission) | 7.90 ± 0.47 | 8.36 ± 0.63 | 8.06 ± 0.50 | 8.39 ± 0.52 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 4.85 ± 0.42 | 5.05 ± 0.66 | 4.86 ± 0.53 | 5.07 ± 0.64 |

| APACHE II score at infection onset | 21.05 ± 1.05 | 19.5 ± 1.51 | 19.8 ± 1.49 | 22.4 ± 1.62 |

| SOFA score at infection onset | 9.07 ± 0.66 | 8.81 ± 0.88 | 8.66 ± 0.86 | 9.92 ± 0.97 |

| ICU LOS (days) at infection onset | 15.92 ± 2.12 | 15.68 ± 3.22 | 19.52 ± 2.89 | 18.42 ± 3.37 |

| No. (%) of patients with shock at infection onset | 31 (75.6) | 15 (68.2) | 26 (72.2) | 19 (67.9) |

| Mean ± SEM Pitt score | 5.90 ± 0.51 | 5.78 ± 0.45 | ||

CAZ-AVI, ceftazidime-avibactam; control, best available therapy; BSI, bloodstream infection; APACHE II, Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; ICU LOS, intensive care unit length of stay.

Comparisons were made between the main groups (the CAZ-AVI and control groups) and the BSI subgroups.

Antibiotic administration.

The types of index infections, the susceptibilities of the CRE isolates, and the prescribed antibiotics are presented in Tables S1, S2, and S3, respectively. Concerning colistin, 41.46% of the K. pneumoniae isolates from the CAZ-AVI group were susceptible to colistin, while 86.11% of the K. pneumoniae isolates from the control group were susceptible to colistin (P < 0.0001). Class A carbapenemase (KPC) production was the mechanism of resistance in 100% of the pathogens isolated from the CAZ-AVI group and 87.1% of the pathogens isolated from the control group (P = 0.072). The majority of patients in the control group had been hospitalized in the first 2 years of the study period, while the majority of the CAZ-AVI group patients had been hospitalized in the last 16 months. The increased rates of colistin resistance may explain the increased use of CAZ-AVI over the years. None of the patients included in the CAZ-AVI group or the control group received carbapenems.

Shock was present in 75.6% of the patients in the CAZ-AVI group and in 72.2% of the patients in the control group (P = 0.876). The mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) time from the time of infection onset to the time of initiation of appropriate therapy was 2.048 ± 0.43 days in the CAZ-AVI group and 1.03 ± 0.24 days in the control group (P = 0.048), as in control patients, the antibiotic regime that was started empirically included at least one antibiotic to which the isolated pathogen was susceptible, usually colistin. For the CAZ-AVI patients with an isolate susceptible to colistin, the mean time of initiation of appropriate therapy was 1.12 ± 0.32 days (as colistin therapy had been started in most patients). The appropriate antibiotics that were administered to both groups are presented in Table S3. Twenty-four patients in the CAZ-AVI group and 31 in the control group received colistin (P = 0.007). Twenty-two percent of the patients in the CAZ-AVI group (77.8% of which had a bloodstream infection [BSI]) received monotherapy, and only one (2.8%) patient in the control group (P = 0.101) received monotherapy, and that patient ultimately died. A total of 43.9% of CAZ-AVI group patients and 75% of control group patients received two antibiotics with activity against CRE (P = 0.013). CAZ-AVI was administered for a median duration of 11 days (interquartile range [IQR], 10 to 15 days), while appropriate antimicrobial treatment was administered for 15 days (IQR, 9 to 21 days) in the control group (P = 0.034).

Outcomes.

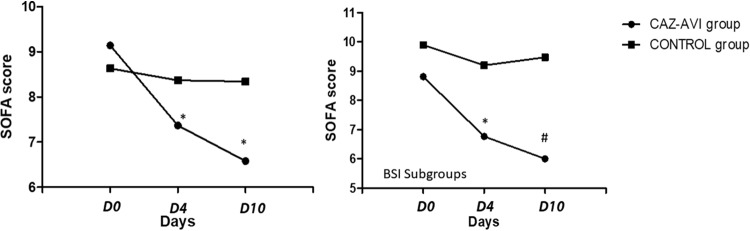

There was a statistically significant difference between the SOFA score on day 0 and that on day 4 (−1.80 ± 0.73 versus 0.84 ± 0.50, P = 0.006) and between the SOFA score on day 0 and that on day 10 (−2.38 ± 0.89 versus 1.20 ± 0.72, P = 0.003) (Fig. 2). Clinical cure was observed in 33/41 patients in the CAZ-AVI group and in 19/36 patients in the control group (P = 0.010). Microbiological eradication was accomplished in 33/35 patients in the CAZ-AVI group and in 21/31 patients in the control group (P = 0.021) (Table 2). Two relapse infections were noted in the CAZ-AVI group, and 12 were noted in the control group (P = 0.042). One of the two pathogens responsible for the relapse infection in the CAZ-AVI group presented resistance to CAZ-AVI; molecular testing revealed that it produced a class B carbapenemase and had a clonality different from that of the pathogen responsible for the index infection. Therefore, mechanisms of resistance to CAZ-AVI were not observed. In the control group, 10 isolates with resistance to colistin were detected in subsequent cultures (P = 0.001). Clonality was not examined in these isolates. The mean ± SEM time from the time of initial antibiotic treatment to the time of isolation of the colistin resistant pathogens was 27.3 ± 4.92 days. Half of the patients had received monotherapy with colistin, one had received a triple therapy, and the other four received a combination of colistin with tigecycline.

FIG 2.

SOFA score change (ΔSOFA score) during the first 10 days of treatment in the two main study groups and the two BSI subgroups. For the CAZ-AVI and control main study groups, the ΔSOFA score was −1.80 ± 0.73 versus 0.84 ± 0.50, respectively (P = 0.006), on day 4 and −2.38 ± 0.89 versus 1.20 ± 0.72, respectively (P = 0.003), on day 10. For the CAZ-AVI and control BSI subgroups, the ΔSOFA score was −2.04 ± 1.21 versus 0.58 ± 0.51, respectively (P = 0.046), on day 4 and −2.17 ± 1.61 versus 1.33 ± 0.85, respectively (P = 0.051), on day 10. *, statistical significance for within-group comparisons; #, statistical significance for between-group comparisons.

TABLE 2.

Outcome variables in both study groupsa

| Variable | Value for patients in the following groupsb: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAZ-AVI group (n = 41) | CAZ-AVI BSI subgroup (n = 22) | Control group (n = 36) | Control BSI subgroup (n = 28) | |

| SOFA score on day 0 | 9.07 ± 0.66 | 8.81 ± 0.88 | 8.66 ± 0.86 | 9.92 ± 0.97 |

| SOFA score on day 4 | 7.62 ± 0.89 | 6.77 ± 1.13 | 8.40 ± 0.82 | 9.25 ± 0.91 |

| ΔSOFA score on day 4 | −1.80 ± 0.73* | −2.04 ± 1.21* | 0.84 ± 0.50 | 0.58 ± 0.51 |

| SOFA score on day 10 | 6.58 ± 1.02 | 6.00 ± 1.51* | 8.34 ± 0.87 | 9.47 ± 0.95 |

| ΔSOFA score on day 10 | −2.38 ± 0.89* | −2.17 ± 1.61* | 1.20 ± 0.72 | 1.33 ± 0.85 |

| No. of patients with the following/total no. of patients (%): | ||||

| Clinical cure | 33/41* (80.48) | 18/22* (81.8) | 19/36 (52.8) | 15/28 (53.57) |

| Microbiological eradication on day 10c | 33/35* (94.3) | 18/18* (100) | 21/31 (67.7) | 17/23 (73.9) |

| No. of deaths up to day 10 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Median (IQR) duration of appropriate antibiotic treatment (days)d | 11 (10–15)* | 10.5 (9.75–14.25)* | 15 (9–21) | 16 (7–25) |

| No. of patients with relapses | 2* | 0* | 12 | 6 |

| Mean ± SEM no. of days to relapse | 35.6 ± 3.4 | 0 | 27.3 ± 4.92 | 26.8 ± 4.44 |

| 28-day survival rate (%) | 85.4* | 81.8 | 61.1 | 57.1 |

| ICU survival rate (%) | 61 | 59.1* | 41.7 | 32.1 |

CAZ-AVI, ceftazidime-avibactam; control, best available therapy; BSI, bloodstream infection; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; IQR, interquartile range.

Comparisons were made between the main groups (the CAZ-AVI and control groups) and the BSI subgroups. *, P < 0.05.

Microbiological cure was estimated for patients alive on day 10.

Duration of CAZ-AVI treatment in the CAZ-AVI group and the duration of appropriate antimicrobial therapy in the control group.

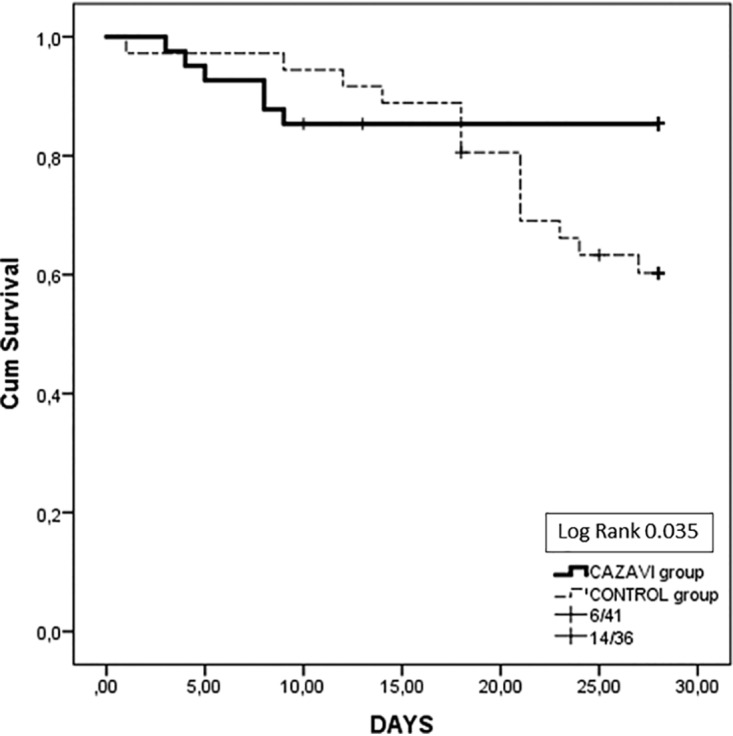

The 28-day survival rate was 85.4% in the CAZ-AVI group and 61.1% in the control group (log-rank test = 0.035) (Table 2; Fig. 3). The cumulative rate of survival among the ICU patients was 61% in the CAZ-AVI group and 41.7% in the control group (P = 0.264). The ICU length of stay (LOS) for patients that were discharged did not differ between the two groups (44.88 ± 7.62 and 55.86 ± 7.81 days, respectively). The results of univariate analysis between survivors and nonsurvivors are presented in Table 3. Multivariate analysis revealed that the most significant predictor of clinical cure was an antibiotic regime containing CAZ-AVI (odds ratio [OR], 5.125; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.680 to 15.619; P = 0.004) (Table 4). Independent predictors for 28-day survival were treatment with CAZ-AVI (OR, 5.575; 95% CI, 1.469 to 21.169; P = 0.012) and a lower SOFA score on infection onset (OR, 0.805; 95% CI, 0.684 to 0.948; P = 0.010) (Table 4). The time of appropriate antibiotic treatment initiation did not differ between survivors and nonsurvivors (1.25 ± 0.32 versus 1.68 ± 0.33 days, P = 0.465).

FIG 3.

Twenty-eight-day survival in the whole study group.

TABLE 3.

Univariate analysis between survivors and nonsurvivors in the whole study groupa

| Characteristic | Value for patients in the following groups: |

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors (n = 57) | Nonsurvivors (n = 20) | ||

| Age (yr) | 58.85 ± 2.18 | 65.6 ± 2.81 | NS |

| No. (%) of male patients | 37 (64.9) | 12 (60) | NS |

| No. (%) of patients admitted for surgery | 27 (47.3) | 9 (405) | NS |

| Mean ± SEM value for: | |||

| APACHE II score (admission) | 18.43 ± 1.00 | 20.05 ± 1.32 | NS |

| SOFA score (admission) | 7.47 ± 0.38 | 9.4 ± 0.60 | 0.012 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 4.31 ± 2.61 | 6.4 ± 0.71 | 0.005 |

| APACHE score (at infection onset) | 18.68 ± 0.91 | 25.55 ± 1.83 | 0.001 |

| SOFA score (at infection onset) | 7.70 ± 0.50 | 12.25 ± 1.19 | <0.001 |

| ICU LOS (at infection onset) | 19.01 ± 2.25 | 13.6 ± 2.06 | NS |

| No. (%) of patients with shock (at infection onset) | 38 (66.6) | 17 (85) | NS |

| No. (%) of patients receiving a CAZ-AVI-containing regime | 35 (61.4) | 6 (30) | 0.015 |

| No. (%) of patients with a BSI | 34 (59.6) | 16 (80) | NS |

| Mean ± SEM Pitt score | 5.35 ± 0.40 | 6.87 ± 0.53 | 0.033 |

CAZ-AVI, ceftazidime-avibactam; control, best available therapy; BSI, bloodstream infection; APACHE II, Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; ICU LOS, intensive care unit length of stay from the time of ICU admission until the time of infection onset.

Comparisons were made between the main groups (the CAZ-AVI and control groups) and the BSI subgroups. NS, not significant.

TABLE 4.

Multivariate analysis to determine predictors of 28-day survival and clinical cure in the CAZ-AVI and control groups of patientsa

| Variable | Values for predictors of 28-day survival |

Values for predictors of clinical cure |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

| SOFA score on admission | 0.906 | 0.677–1.213 | 0.507 | 0.976 | 0.788–1.209 | 0.827 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.830 | 0.655–1.053 | 0.124 | 0.880 | 0.704–1.101 | 0.263 |

| SOFA score at infection onset | 0.805 | 0.684–0.948 | 0.010 | 0.887 | 0.772–1.019 | 0.091 |

| CAZ-AVI containing regime | 5.575 | 1.469–21.162 | 0.012 | 5.123 | 1.680–15.619 | 0.004 |

CAZ-AVI, ceftazidime-avibactam; control, best available therapy; BSI, bloodstream infection; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; CI, confidence interval.

Side effects.

During the whole study period, there were no differences in the results of liver and renal function and coagulation tests between the two groups, nor was there any statistically significant worsening in the results of the above-mentioned tests between days 0, 4, and 10 in each study group. There was a nonstatistically significant decrease in the creatinine levels in the CAZ-AVI group compared to the control group (data not shown). Two patients in the CAZ-AVI group and four in the control group required initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT; which in all patients was started by the 5th day of infection onset) (P = 0.653), while eight and seven patients in the CAZ-AVI and control groups, respectively, were already receiving CRRT at the time of the index infection, due to episodes of acute renal failure during the index hospitalization. In this CRRT subpopulation, the cure rates did not differ significantly between the two study groups (microbiological eradication, 5/10 versus 2/11, respectively [P = 0.223]; clinical cure, 6/10 versus 2/11, respectively [P = 0.114]). None of the patients in the CAZ-AVI group and 3/11 in the control group required CRRT after ICU discharge.

BSI subgroup analysis.

BSI was the index infection in 22 (53.66%) patients in the CAZ-AVI group and in 28 (77.78%) patients in the control group. The baseline variables did not differ between the BSI subgroups. Shock on index infection onset was present in 68.2% of the patients in the CAZ-AVI subgroup and in 67.9% of those in the control subgroup (Table 1). Appropriate antibiotic therapy was initiated in 1.82 ± 0.57 versus 0.96 ± 0.26 days (P = 0.151) in the two groups, respectively. K. pneumoniae isolates from the CAZ-AVI subgroup presented increased rates of resistance to colistin (50% versus 10.72% for the control subgroup, P = 0.047); thus, the proportion of patients who received colistin differed significantly between the two study groups (12/22 versus 24/28, P = 0.014). More patients in the CAZ-AVI subgroup than in the control subgroup received monotherapy (7/22 versus 1/28, P = 0.012) (Table S3).

A greater change in the SOFA score (ΔSOFA score) (decrease) on the 4th and 10th days of treatment was detected in the CAZ-AVI subgroup than in the control subgroup (ΔSOFA score on day 4, −2.04 ± 1.21 versus 0.58 ± 0.51 [P = 0.046]; ΔSOFA score on day 10, −2.17 ± 1.61 versus 1.33 ± 0.85 [P = 0.051]). The SOFA score had significantly improved by the 10th day in the CAZ-AVI subgroup compared to that in the control subgroup (6.00 ± 1.51 versus 9.47 ± 0.95, P = 0.05). Clinical cure was observed in 18/22 (81.8%) and 15/28 (53.6%) patients in the CAZ-AVI and control subgroups, respectively (P = 0.038). Microbiological eradication was observed in 18/18 (100%) patients in the CAZ-AVI subgroup and 17/23 (73.9%) patients in the control subgroup (P = 0.014). Only six patients in the control group experienced relapses (P = 0.027) (Table 2). Resistant isolates appeared in 5 patients, and these were only in the control group (0 versus 5, P = 0.042). Four out of the six control group patients who experienced relapses ultimately died (mean time to death, 85.6 ± 42.76 days).

The 28-day survival rate was 81.8% and 57.1% in the CAZ-AVI and control groups, respectively (log-rank test = 0.120), while ICU survival was 59.1% versus 32.1% in the CAZ-AVI and control groups, respectively (P = 0.264) (77.65 ± 17.76 versus 62.26 ± 15.05 days, respectively) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

The results of the present observational, retrospective cohort study indicate that life-threatening infections caused by carbapenem-resistant pathogens in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients, who mostly present with septic shock and multiorgan failure, can be effectively managed with an antimicrobial regime including the new antibiotic CAZ-AVI. Patients receiving CAZ-AVI presented with prompt improvements in terms of multiorgan failure, increased microbiological eradication and clinical cure rates, and increased 28-day survival compared to the results for patients treated with a control. Similar results were observed in the subgroups of patients with BSI. The use of CAZ-AVI for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant infections was a significant predictor of clinical cure, while CAZ-AVI treatment and the severity of illness upon infection onset determined the 28-day survival rate.

Critical illness, particularly in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, results in extreme fluid extravasation into the interstitial space from endothelial damage and capillary leakage (7, 8). This extravasation substantially increases the interstitial volume. For hydrophilic antibiotics, a rise in the interstitial volume might lead to a large increase in the volume of distribution (6). Moreover, for antibiotics that are moderately to highly protein bound, the volume of distribution rises by up to 100% in critically ill patients with hypoalbuminemia (6). On the other hand, augmented renal clearance is frequently seen in critically ill patients with normal serum creatinine concentrations. These circumstances may pose the risk of underdosing, and thus, some critically ill patients with renal impairment might actually need more intensive regimens of antibiotics (6). To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of CAZ-AVI, focusing exclusively on the frail, critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients. The patients were recruited from two ICUs from southern Europe (central Greece), where K. pneumoniae resistance to carbapenems is attributed to KPC carbapenemase production in almost 80% of isolates (9). Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant pathogens are associated with high rates of treatment failure and increased mortality. Dealing with K. pneumoniae infections has become a real challenge over the last few years, due to the limited availability of effective antimicrobials. Among them, aminoglycosides, tigecycline, colistin, and fosfomycin have remained the last options (10), yet the increased consumption of colistin has led to increased nonsusceptibility rates (11). Two recent studies reported an incidence of colistin resistance among K. pneumoniae isolates of 23% and 40.4% in Greece (9, 12). This worrisome finding of increased colistin resistance among K. pneumoniae isolates was depicted between the two study groups evaluated in our study (colistin resistance in 58.54% for the CAZ-AVI group versus 13.89% for the control group, P < 0.0001). Therefore, the introduction of new antibiotics has become an urgent need during the last decade.

Scarce data comparing the effectiveness of CAZ-AVI against that of other antibiotic combinations (most of which include colistin) in the treatment of carbapenem-resistant infections are available. CAZ-AVI has recently been introduced for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal and urinary tract infections caused by CRE by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), while, additionally, it has received authorization by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia and for aerobic Gram-negative bacterial infections in adults with limited treatment options (13). However, in registration clinical trials, CAZ-AVI was compared to carbapenems for the treatment of infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Therefore, phase 3 clinical trials did not include carbapenem-resistant isolates. This is the first report to compare the effectiveness of CAZ-AVI with that of a therapeutic regime that includes at least one appropriate antibiotic, mainly colistin, for the treatment of exclusively carbapenem-resistant infections in critically ill patients.

Our results support the scarce published data concerning the effective treatment of ICU patients suffering from life-threatening infections with the new antibiotic agent CAZ-AVI. Tumbarello et al. reported a favorable outcome in 138 patients, 33% of whom were ICU patients (14). In that study, patients were recruited from different centers, and there was no report on the severity (neither illness severity nor at the infection onset), the number of mechanically ventilated patients, and, most importantly, the outcomes in this subset of patients. The inclusion of mechanically ventilated patients with different severity scores and central venous catheter insertion practices treated under different therapeutic protocols renders an inhomogeneous population, which may affect the ability to draw generalizations about the outcomes. In our study, all patients, recruited from two ICUs, one from a university hospital and another hospital from which patients are referred, were mechanically ventilated, had a central venous catheter present, and were treated following similar therapeutic protocols; therefore, the results correspond to a more uniform population. Patients in the CAZ-AVI group had a significant and sustained improvement in multiorgan function (depicted by the SOFA score) on the 4th and 10th days of treatment, and clinical cure rates were significantly higher for the CAZ-AVI group than for the control group. Importantly, more patients treated with CAZ-AVI presented microbiological eradication by the 10th day of treatment. Similar improvements were observed in BSI patients.

A difference between the two studies that can explain our results is that the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment in our study was earlier than that reported by Tumbarello et al. (2.05 ± 0.43 versus 7 days, respectively), although patients from the latter study still presented a favorable outcome (14). The timely initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy is crucial for increased survival in critically ill patients (15).

Our results are in accordance with those reported in the study of Van Duin et al. (16). In that retrospective study, the efficacy of CAZ-AVI over that of colistin was evaluated in 137 patients with CRE infections; 38 patients received CAZ-AVI, and only 7 presented with a critical illness, defined as a Pitt score of >4 at the time of a positive culture (16). Our study, presenting data exclusively on critically ill patients with life-threatening infections, gives more robust evidence for the effectiveness of CAZ-AVI in this population.

The 30-day mortality rate after BSI due to carbapenem-resistant pathogens has been reported to be about 50%, which corresponds to the mortality rate found in our control group (17). The treatment of BSIs with a therapeutic regime containing CAZ-AVI led to increased survival in our cohort by almost 30%. Improved survival in patients treated with CAZ-AVI has also been reported previously, but this is the first study that clearly demonstrates a survival benefit in mechanically ventilated ICU patients (14, 16, 18). A CAZ-AVI-including therapeutic regime, along with less severe disease at the infection onset, expressed by the SOFA score, independently predicted survival.

KPC carbapenemase production was the main mechanism of carbapenem resistance of the pathogens isolated from the two study groups (100% for the CAZ-AVI group and 87.1% for the control group). The mechanism of resistance seems not to have changed during the last 4 years in Greece since the epidemiological report of Galani et al. on the resistance phenotypes of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae strains in Greece between the years 2014 and 2016 (9). However, soon after CAZ-AVI’s launch, reports on the emergence of resistance, which represents a public health threat, were submitted (3). Baseline resistance to CAZ-AVI has been reported in up to 2 to 3% of CRE isolates and has been attributed to the production of the NDM-1 carbapenemase. In 2015, Humphries et al., reported the first clinical isolate resistant to CAZ-AVI and found that it carried a KPC-3 enzyme (19), yet the emergence of resistance has been reported after 10 to 19 days of CAZ-AVI treatment (20–22). In Europe, two cases of isolates that became resistant to CAZ-AVI after exposure to CAZ-AVI treatment, one producing OXA-48 and CTX-M-14 and the other harboring a blaKPC-3 mutation, have been described (23, 24). In our cohort, two patients presented with a relapse infection. In one, the responsible isolate was resistant to CAZ-AVI. Molecular analysis revealed that the isolate responsible for the index infection was a KPC-producing K. pneumoniae isolate, while the second isolate produced a VIM metallo-β-lactamase and did not arise from the same clone responsible for the index infection. However, surveillance cultures, performed on a regular basis, are mandatory for the early diagnosis of resistance emergence, as great differences in mechanisms of resistances may be present even in the same country (9).

Our study presents a few limitations. First, it was a retrospective study, and therefore, the analysis of preexisting data may be subject to numerous biases. Another limitation of the present study is that the distributions of the two groups of patients included in the study differed across the study period. As a result, resistance profiles, especially for resistance to colistin, changed substantially, yet the personnel and therapeutic protocols applied did not change significantly during the study period, while compliance with the latter was safeguarded through regular meetings between the two centers. Thus, in order to have a balanced population, only patients with colistin-susceptible pathogens should have been included; only then could comparisons of therapeutic efficacy be fair. However, this was not the aim of the present study, which explored the effectiveness of CAZ-AVI in mechanically ventilated patients in the era of increased colistin resistance rates.

In conclusion, this is the first report of a study that tried to evaluate the effectiveness of CAZ-AVI as at least part of an antimicrobial regime targeting life-threatening infections due to carbapenem-resistant pathogens in ICU patients. Patients treated with CAZ-AVI presented more rapid and sustained clinical improvements and microbiological eradication and, most importantly, presented increased survival compared to the results for patients treated with antibiotic combinations, which included colistin in the majority of the cases. On the other hand, clinicians should pay an effort to use CAZ-AVI cautiously, as resistant isolates have emerged, posing a public health threat. Case-by-case consideration and interprofessional teamwork are mandatory in an effort to preserve one of the last options in the current antibiotic armamentarium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective observational study was conducted in two ICUs from hospitals located in Central Greece (the University Hospital of Larissa and the General Hospital of Lamia) during a 40-month period. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Larissa (approval no. 22/4th/28-02-2019).

Eligibility criteria were as follows: (i) the patients had to be >18 years of age, (ii) the patients had to be intubated and mechanically ventilated, (iii) the patients had to have a documented CRE infection, (iv) the patients had to have multiorgan failure at the onset of the infection (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA] score > 3, Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation II [APACHE II] score > 10), and (v) the patient isolates had to be susceptible to the dosing antibiotics (in the case of susceptibility to fosfomycin, the isolate had to be susceptible to one more agent). Patients were excluded if (i) death occurred within 48 h of initiation of appropriate therapy and (ii) the patients had chronic renal failure, defined as a baseline creatinine level of >3 mg/dl and/or a need for hemodialysis. Eligible patients were divided into two different groups: all the patients who received CAZ-AVI as part of their antibiotic treatment after the antibiotic’s launch entered the CAZ-AVI group. The control group comprised all consecutive patients that received antibiotics other than CAZ-AVI during the study period. CAZ-AVI was initiated according to the attending physician’s decision (after the antibiotic was available in Greece), although it was mainly driven by previous experience with colistin use in our ICUs (25).

Antibiotic administration protocol.

CAZ-AVI (2 g of ceftazidime/0.5 g avibactam) was administered over a 2-h infusion period every 8 h. No dose adjustments were made in patients on CRRT. Colistin was administered at a dose of 4.5 × 106 IU every 12 h after a loading dose of 9 × 106 IU, while patients on CRRT received 4.5 106 IU three times daily. For patients with decreased creatinine clearance, dosing adjustments were made according to published formulas (26). Aminoglycoside dosing was led by the therapeutic drug monitoring results. Tigecycline was administered at a dose of 100 mg twice daily (after a loading dose of 200 mg).

Outcomes.

The primary outcome was multiorgan failure improvement on day 10 and mortality on day 28 after the onset of the study infection. Secondary outcomes were microbiological eradication of the pathogen and relapse of the infection.

Clinical assessment.

Age, the Charlson comorbidity index, and the APACHE II and SOFA scores were obtained on admission, while the APACHE II and SOFA scores were also calculated on the day of the index infection onset. The Pitt bacteremia score was calculated for patients suffering from bloodstream infection (BSI).

Definitions.

Sepsis and septic shock were defined according to recently updated terms (27). The index infection was considered the infection for which the patient was included in the study. The types of infections were defined according to the standardized definitions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Healthcare Safety Network (28).

The isolation of a carbapenem-resistant pathogen from biological samples without the presence of criteria for clinical infection was considered colonization (28, 29). Infection onset was defined as the day that the sample positive by culture was drawn. Empirical therapy was defined as therapy that was initiated at the onset of the index infection, and it was based on (i) pathogens that had been isolated from surveillance cultures of samples from the patients and (ii) the local ICU microbiology. Appropriate antimicrobial treatment referred to administration of at least one of the antimicrobials active against the study isolates in vitro. Fosfomycin monotherapy was not considered appropriate therapy, and patients receiving fosfomycin were excluded. Microbiological eradication was defined as the absence of the initially isolated pathogen from the site of the index infection by the 10th day. Samples for repeat culture were obtained per the local protocol even in the absence of clinical or laboratory signs of infection. For bloodstream infections, a blood sample for culture was obtained 72 h after infection onset, and a sample for repeat culture (even if the first sample was negative) was obtained by the 9th to 10th day after infection onset. In ventilator-associated pneumonia cases, samples for repeat culture were obtained per the local protocol depending on the quantity and the quality of patient’s bronchial secretions and were always obtained by the 9th to 10th day after infection onset. Microbiological eradication was assessed only for the patients that were alive on the 10th day. Clinical cure was defined as the resolution of all symptoms and signs that were present at the onset of the index infection with the initial appropriate antibiotic therapy. Patients not meeting all of the criteria described above were considered clinical failures. Relapse was defined as the onset of a new infection caused by the initially isolated pathogen (independently of clonality or the resistance profile) after the patient had recovered from the initial infection within a period of 60 days (covering the period of the ICU and hospital stays).

Microbiology.

Identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing of the microorganisms were performed by use of the Vitek 2 automated system (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). The MICs of colistin were determined by a commercial broth microdilution method (Com ASP Colistin; Liofilchem). The MICs of CAZ-AVI were determined by the Etest method. Interpretation of the susceptibility results was based on EUCAST criteria. All the pathogens that had meropenem MICs of >2 mg/liter were tested for the production of carbapenemase using the protocol proposed by EUCAST. In brief, to identify class A and B carbapenemases, the combination disk test was applied, using boronic and dipicolinic acid, respectively (30). In the CAZ-AVI group, for patients presenting with a relapse, if the isolate’s susceptibility to CAZ-AVI was different from that of the index isolate, further testing for the presence of the blaVIM, blaNDM, blaOXA-48, and blaKPC genes was performed by PCR.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). The normality of the data was tested by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Student's t test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare normally and nonnormally distributed variables, respectively. In order to identify predictors of 28-day survival and clinical cure, univariate analysis was performed using as predictors data from the baseline and infection onset variables (age, sex, reason for admission, APACHE II and SOFA scores on admission, SOFA score on infection onset, Charlson comorbidity index, ICU length of stay [LOS] until infection onset). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using only statistically significant variables from the univariate analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We declare no conflict of interest.

This work has not received any funds.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Poirel L. 2015. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5873–5884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01019-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giske CG, Sundsfjord AS, Kahlmeter G, Woodford N, Nordmann P, Paterson DL, Cantón R, Walsh TR. 2009. Redefining extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: balancing science and clinical need. J Antimicrob Chemother 63:1–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2018. Emergence of resistance to ceftazidime-avibactam in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falagas ME, Lourida P, Poulikakos P, Rafailidis PI, Tansarli GS. 2014. Antibiotic treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: systematic evaluation of the available evidence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:654–663. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01222-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, Moreno R, Lipman J, Gomersall C, Sakr Y, Reinhart K, EPIC II Group of Investigators . 2009. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 302:2323–2329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts J, Abdul-Aziz M, Lipman J, Mouton J, Vinks A, Felton T, Hope W, Farkas A, Neely M, Schentag J, Drusano G, Frey O, Theuretzbacher U, Kuti J, on behalf of the International Society of Anti-infective Pharmacology and the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics Study Group of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases . 2014. Individualized antibiotic dosing for patients who are critically ill: challenges and potential solutions. Lancet Infect Dis 14:498–509. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70036-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonçalves-Pereira J, Póvoa P. 2011. Antibiotics in critically ill patients: a systematic review of the pharmacokinetics of β-lactams. Crit Care 15:R206. doi: 10.1186/cc10441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts JA, Pea F, Lipman J. 2013. The clinical relevance of plasma protein binding changes. Clin Pharmacokinet 52:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s40262-012-0018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galani I, Karaiskos I, Karantani I, Papoutsaki V, Maraki S, Papaioannou V, Kazila P, Tsorlini H, Charalampaki N, Toutouza M, Vagiakou H, Pappas K, Kyratsa A, Kontopoulou K, Legga O, Petinaki E, Papadogeorgaki H, Chinou E, Souli M, Giamarellou H. 2018. Epidemiology and resistance phenotypes of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece, 2014 to 2016. Euro Surveill 23(31):pii=17000775 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.30.1700775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karaiskos I, Giamarellou H. 2014. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens: current and emerging therapeutic approaches. Expert Opin Pharmacother (15):1351–1370. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.914172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). 2017. Antimicrobial consumption. Surveillance and disease data. Antimicrobial consumption database. Trend by country. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maltezou HC, Kontopidou F, Dedoukou X, Katerelos P, Gourgoulis GM, Tsonou P, Maragos A, Gargalianos P, Gikas A, Gogos C, Koumis I, Lelekis M, Maltezos E, Margariti G, Nikolaidis P, Pefanis A, Petrikkos G, Syrogiannopoulos G, Tsakris A, Vatopoulos A, Saroglou G, Kremastinou J, Daikos GL, Working Group for the National Action Plan to Combat Infections due to Carbapenem-Resistant, Gram-Negative Pathogens in Acute-Care Hospitals in Greece . 2014. Action plan to combat infections due to carbapenem-resistant, Gram-negative pathogens in acute-care hospitals in Greece. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Medicines Agency (EMA). 2018. European public assessment report (EPAR) for Zavicefta. Last update, June 2016 http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/004027/WC500210237.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2018.

- 14.Tumbarello M, Trecarichi EM, Corona A, De Rosa FG, Bassetti M, Mussini C, Menichetti F, Viscoli C, Campoli C, Venditti M, De Gasperi A, Mularoni A, Tascini C, Parruti G, Pallotto C, Sica S, Concia E, Cultrera R, De Pascale G, Capone A, Antinori S, Corcione S, Righi E, Losito AR, Digaetano M, Amadori F, Giacobbe DR, Ceccarelli G, Mazza E, Raffaelli F, Spanu T, Cauda R, Viale P. 2019. Efficacy of ceftazidime-avibactam salvage therapy in patients with infections caused by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis 68:355–364. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, Light B, Parrillo JE, Sharma S, Suppes R, Feinstein D, Zanotti S, Taiberg L, Gurka D, Kumar A, Cheang M. 2006. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 34:1589–1596. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Duin D, Lok JJ, Earley M, Cober E, Richter SS, Perez F, Salata RA, Kalayjian RC, Watkins RR, Doi Y, Kaye KS, Fowler VG, Paterson DL, Bonomo RA, Evans S, Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group . 2018. Colistin versus ceftazidime-avibactam in the treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 66:163–171. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satlin MJ, Chen L, Patel G, Gomez-Simmonds A, Weston G, Kim A, Seo SK, Rosenthal ME, Sperber SJ, Jenkins SG, Hamula CL, Uhlemann AC, Levi MH, Fries BC, Tang YW, Juretschko S, Rojtman AD, Hong T, Mathema B, Jacobs MR, Walsh TJ, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2017. Multicenter clinical and molecular epidemiological analysis of bacteremia due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in the CRE epicenter of the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02349-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02349-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Chen L, Press GE, Potoski GA, Marini RV, Doi Y, Kreiswirth BN, Clancy CJ. 2017. Ceftazidime-avibactam is superior to other treatment regimens against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00883-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00883-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphries RM, Yang S, Hemarajata P, Ward KW, Hindler JA, Miller SA, Gregson A. 2015. First report of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in a KPC-3 expressing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6605–6607. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01165-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shield RK, Chen L, Cheng S, Chavda K, Press EG, Snyder A, Pandey R, Doi Y, Kreiswirth BN, Nguyen MH, Clancy CJ. 2017. Emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance due to plasmid-borne blaKPC-3 mutations during treatment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02097-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02097-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shields RK, Potoski BA, Haidar G, Hao B, Doi Y, Chen L, Press EG, Kreiswirth BN, Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. 2016. Clinical outcomes, drug toxicity, and emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance among patients treated for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Clin Infect Dis 63:1615–1618. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giddins MJ, Macesic N, Annavajhala MK, Stump S, Khan S, McConville TH, Mehta M, Gomez-Simmonds A, Uhlemann AC. 2018. Successive emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance through distinct genomic adaptations in blaKPC-2-harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 307 isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e02101-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02101-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Both A, Buttner H, Huang J, Perbandt M, Belmar Campos C, Christner M, Maurer FP, Kluge S, König C, Aepfelbacher M, Wichmann D, Rohde H. 2017. Emergence of ceftazidime/avibactam non-susceptibility in an MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:2483–2488. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaibani P, Campoli C, Lewis RE, Volpe SL, Scaltriti E, Giannella M, Pongolini S, Berlingeri A, Cristini F, Bartoletti M, Tedeschi S, Ambretti S. 2018. In vivo evolution of resistant subpopulations of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae during ceftazidime/avibactam treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:1525–1529. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mantzarlis K, Makris D, Manoulakas E, Karvouniaris M, Zakynthinos E. 2013. Risk factors for the first episode of Klebsiella pneumoniae resistant to carbapenems infection in critically ill patients: a prospective study. Biomed Res Int 2013:850547. doi: 10.1155/2013/850547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin AS, Barone AA, Penço J, Santos MV, Marinho IS, Arruda EA, Manrique EI, Costa SF. 1999. Intravenous colistin as therapy for nosocomial infections caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Infect Dis 28:1008–1011. doi: 10.1086/514732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer M, Deutschman C, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. 2016. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. 2008. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of healthcare-associated infections and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 36:309–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Healthcare Safety Network. 2016. CDC-NHSN ventilator-associated event (VAE). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/10-vae_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malli E, Florou Z, Tsilipounidaki K, Voulgaridi I, Stefos A, Xitsas S, Papagiannitsis CC, Petinaki E. 2018. Evaluation of rapid polymyxin NP test to detect colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in a tertiary Greek hospital. J Microbiol Methods 153:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.