Abstract

Bordetella pertussis produces several toxins that affect host-pathogen interactions. Of these, the major toxins that contribute to pertussis infection and disease are pertussis toxin, adenylate cyclase toxin-hemolysin and tracheal cytotoxin. Pertussis toxin is a multi-subunit protein toxin that inhibits host G protein-coupled receptor signaling, causing a wide array of effects on the host. Adenylate cyclase toxin-hemolysin is a single polypeptide, containing an adenylate cyclase enzymatic domain coupled to a hemolysin domain, that primarily targets phagocytic cells to inhibit their antibacterial activities. Tracheal cytotoxin is a fragment of peptidoglycan released by B. pertussis that elicits damaging inflammatory responses in host cells. This chapter describes these three virulence factors of B. pertussis, summarizing background information and focusing on the role of each toxin in infection and disease pathogenesis, as well as their role in pertussis vaccination.

Keywords: Bordetella toxins, Pertussis toxin, Adenylate cyclase toxin-hemolysin, Tracheal Cytotoxin, Pertussis pathogenesis

1. PERTUSSIS TOXIN

1.1. Background

Pertussis toxin (Agarwal et al.) is a multi-subunit (AB5) protein toxin secreted by B. pertussis. PT binds mammalian cell surface glycosylated molecules (Witvliet et al. 1989) in a non-saturable and non-specific manner (Finck-Barbancon and Barbieri 1996), indicating lack of a specific receptor. PT is endocytosed and transported by the retrograde pathway to the endoplasmic reticulum (el Baya et al. 1997; Plaut and Carbonetti 2008; Plaut et al. 2016), from where the A subunit (S1) translocates to the cytosol (Hazes et al. 1996; Pande et al. 2006; Worthington and Carbonetti 2007). In the cytosol, S1 ADP-ribosylates the alpha subunit of heterotrimeric G proteins of the Gi/o class in mammalian cells, inhibiting activation of these G proteins by ligand-bound G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) (Katada 2012). This modification has multiple effects on host cell activities, since many different GPCRs couple to Gi proteins. Binding of the PT B pentamer to mammalian cells elicits various signaling effects independently of the enzymatic activity of S1, but these effects are relatively transient and concentration-dependent (Carbonetti 2010; Mangmool and Kurose 2011; Wong and Rosoff 1996; Schneider et al. 2009; Zocchi et al. 2005) and it is unclear whether this binding and signaling activity of PT is relevant in vivo. PT is an important virulence factor for B. pertussis and is central to the pathogenesis of pertussis infection and disease (as described below) and a detoxified form of PT is an important component of currently used acellular pertussis vaccines (aPV) (Coutte and Locht 2015).

1.2. Role in infection and disease pathogenesis

1.2.1. Systemic and local effects of PT

Systemic administration of purified PT to experimental animals has a variety of biological and toxic effects (Munoz et al. 1981). The most important of these is leukocytosis (Morse and Morse 1976; Munoz et al. 1981; Hinds et al. 1996; Nogimori et al. 1984), a large increase in the number of circulating white blood cells that is also a prominent feature in human infants with pertussis and high levels of which correlate with fatal outcome (Winter et al. 2015). PT likely induces leukocytosis through a number of mechanisms (Carbonetti 2016), including reduced expression of leukocyte surface adhesion molecules such as LFA-1 (Schenkel and Pauza 1999) and CD62L (Hodge et al. 2003; Hudnall and Molina 2000), inhibition of LFA-1-dependent lymphocyte arrest on lymph node high endothelial venules (Bargatze and Butcher 1993; Warnock et al. 1998), and inhibition of chemokine receptor signaling affecting leukocyte migration (Beck et al. 2014; Pham et al. 2008). PT treatment of experimental animals also has adverse effects on control of heart rate and other cardiac functions, independently of leukocytosis (Grimm et al. 1998; Wainford et al. 2008; Adamson et al. 1993; Zheng et al. 2005). Another effect of PT is reduction of vascular barrier integrity (Dudek et al. 2007), which may contribute to the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) in animal models (Bennett et al. 2010), several of which require PT as an adjuvant to stimulate disease (Munoz et al. 1984; Arimoto et al. 2000; Zhao et al. 2008). This led to the recent speculation that PT effects from sub-clinical pertussis infections may be a contributor to exacerbations of multiple sclerosis in humans (Rubin and Glazer 2016). Other effects of systemic administration of PT include vasoactive sensitization to histamine (Munoz et al. 1981) and induction of insulinemia/hypoglycemia (Yajima et al. 1978), although whether these are relevant to pertussis disease in humans is not clear.

The extent to which PT contributes to the respiratory pathology of pertussis is less clear. Experimental animals, such as mice and guinea pigs, do not cough when administered purified PT (Hewitt and Canning 2010) but baboons experimentally-infected with B. pertussis suffer the typical severe paroxysmal pertussis cough (Warfel et al. 2012). However, baboons infected with PT-deficient strains of B. pertussis show no cough symptoms at all, despite being colonized for the same duration as wild type B. pertussis-infected animals (Merkel, unpublished data). This may be because PT is necessary to induce robust respiratory inflammation, as demonstrated in mouse models (Connelly et al. 2012; Khelef et al. 1994), which may be an important contributor to the cough pathology (see more below). In addition, data from natural and volunteer B. pertussis infections indicate that PT plays a role in respiratory pathology. For instance, a PT-deficient strain isolated from a 3-month-old unvaccinated infant in France was associated with a relatively mild and short time course of disease (Bouchez et al. 2009). Also, human volunteers intranasally inoculated with the candidate pertussis vaccine strain BPZE1, which expresses a genetically inactivated form of PT (Mielcarek et al. 2006), did not cough (Thorstensson et al. 2014), although this strain contains two other modifications in potential virulence factors. The paroxysmal nature of pertussis cough may also be an effect of PT activity, since PT can inhibit desensitization of receptors stimulated by tussive agents (Maher et al. 2011), thereby preventing the cessation of the coughing response. In addition, PT effects in experimental animals are long-lived (Carbonetti et al. 2003; Carbonetti et al. 2007) and so the longevity of pertussis cough may also be an effect of PT activity.

Another important activity of PT is likely in promoting fatal pertussis infection in young infants. PT induces leukocytosis and there is a significant correlation between high levels of leukocytosis and fatal outcome in these infants (Rowlands et al. 2010; Surridge et al. 2007; Pierce et al. 2000; Winter et al. 2015). Animal models provide additional evidence supporting the role of PT in promoting fatal outcome in pertussis. For example, PT is required for lethality of B. pertussis infection in neonatal Balb/c (Weiss and Goodwin 1989) and C57BL/6 mice (Scanlon et al. 2017). However, the specific mechanisms by which PT promotes lethality in pertussis remain to be determined and probably involve pathologies beyond leukocytosis and respiratory effects.

1.2.2. Effects of PT on B. pertussis colonization and host immune responses

Most of our understanding of the effects of PT on colonization and immune responses is derived from mouse model experiments, with some recent data from baboon studies, by comparing infection with isogenic strains differing only in PT production. In mice, PT clearly promotes colonization of the respiratory tract, presumably through effects on immune responses (Carbonetti et al. 2003; Connelly et al. 2012). PT inhibits early innate immune defenses, including recruitment of neutrophils to B. pertussis-infected lungs (Carbonetti et al. 2005; Carbonetti et al. 2003; Kirimanjeswara et al. 2005; Andreasen and Carbonetti 2008) and anti-bacterial activity of resident airway macrophages (Carbonetti et al. 2007). PT also inhibits some aspects of adaptive immunity, including migration of dendritic cells in response to lymphatic chemokines (Fedele et al. 2011) and generation of serum antibody responses to B. pertussis during infection (Carbonetti et al. 2004; Mielcarek et al. 1998). However, at the peak of infection PT promotes lung inflammation (Connelly et al. 2012; Khelef et al. 1994; Andreasen et al. 2009), probably through a variety of mechanisms. One such mechanism may involve the PT-dependent increased expression of the epithelial anion exchanger pendrin, which promotes lung inflammatory pathology during B. pertussis infection (Scanlon et al. 2014). Another mechanism involves PT-dependent inhibition of the resolution of lung inflammation (Connelly et al. 2012), possibly by inhibiting activity of specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators such as resolvins and lipoxins (Levy and Serhan 2014), that signal through PT-sensitive GPCRs (Maddox et al. 1997; Krishnamoorthy et al. 2010; Chattopadhyay et al. 2018; Jo et al. 2016).

It is unclear whether lung inflammatory pathology correlates with the severe cough of human pertussis, but the recently developed baboon model of pertussis may shed some light on this. Baboons cough paroxysmally when infected with a clinical isolate of B. pertussis (Warfel et al. 2012; Warfel and Merkel 2014) although, as stated above,they do not develop cough when infected with an isogenic PT-deficient strain. In addition, PT production was associated with cough in rats experimentally infected with B. pertussis (Parton et al. 1994). Even though PT may not be the direct cause of pertussis cough, these findings indicate that there is a strong association between PT production and cough responses, which may be due to the exacerbated inflammatory responses at the peak of infection that are promoted by PT.

1.3. PT as a pertussis vaccine component and therapeutic target

Since the move to aPV in most countries in recent years, a detoxified form of PT has been a component of all of these vaccines, in recognition of its role as a protective antigen against severe disease in infants (Coutte and Locht 2015). Although most of these vaccines contain other pertussis antigens, a monocomponent detoxified PT vaccine is used in Denmark (Thierry-Carstensen et al. 2013). Since pertussis has remained under control in Denmark (Dalby et al. 2016), this indicates that immune responses to this single component can protect a population from pertussis disease effectively. In addition, in the baboon model a monocomponent PT vaccine was sufficient to protect infant animals born to vaccinated mothers from pertussis disease (Kapil et al. 2018).

PT may also be an important target for therapy against pertussis. In one trial, administration of intravenous pertussis immunoglobulin (P-IGIV), which contains high levels of anti-PT antibodies, resulted in significant reduction in leukocytosis in infants with pertussis, and reduced paroxysmal coughing and bradycardic episodes (Bruss et al. 1999). In animal models, treatment with humanized murine monoclonal antibodies specific for PT was more effective than P-IGIV in preventing leukocytosis in mice and reduced leukocytosis when administered therapeutically to infected baboons (Nguyen et al. 2015), highlighting the therapeutic potential of this approach. Very recently, inhibitors of cyclophilins, such as cyclosporine A, were found to inhibit PT activity in cultured cells (Ernst et al. 2018), representing an additional therapeutic strategy targeting PT.

2. ADENYLATE CYCLASE TOXIN-HEMOLYSIN

2.1. Background

Adenylate cyclase toxin-hemolysin (CyaA, ACT or AC-Hly) is a repeat-in-toxin (RTX) cytotoxin expressed by three closely related Bordetella species, B. pertussis, B. parapertussis and B. bronchiseptica (Endoh et al. 1980; Hewlett et al. 1976; Glaser et al. 1988a). This 1706 amino acid polypeptide is encoded by cyaA in an operon containing the type I secretion apparatus genes cyaB, cyaD and cyaE (Glaser et al. 1988b). CyaA contains an N-terminal adenylate cyclase (AC) enzyme domain of 364 amino acid residues and a C-terminal RTX hemolysin moiety of ~1300 residues (Glaser et al. 1988b). The hemolysin moiety is comprised of a hydrophobic pore-forming domain (Benz et al. 1994), an active domain containing two posttranslationally acylated lysine residues (Lys 860 and Lys 983) (Hackett et al. 1994; Hackett et al. 1995), a receptor binding RTX domain with characteristic calcium-binding glycine- and aspartate-rich nonapeptide repeats (Rose et al. 1995) and a C-terminal secretion signal for the type I secretion system (Bumba et al. 2016; Sebo and Ladant 1993). This toxin plays a key role in establishing B. pertussis infection. Activities mediated by both the AC and hemolysin domains of CyaA function to subvert host innate immunity and thereby facilitate initial colonization (as described below). Current formulations of acellular pertussis vaccines do not contain CyaA. However, recently a focus on research elucidating the structure-function relationship of CyaA has emerged, with the aim of using this new understanding to rationally develop CyaA vaccine candidates (Cheung et al. 2006; Osickova et al. 2010; Boehm et al. 2018).

2.2. Role in infection and disease pathogenesis

2.2.1. Host cell subversion by CyaA

First described in 1976 as both a soluble and bacterial cell-associated enzyme (Hewlett et al. 1976), CyaA physically associates with filamentous haemagglutinin (FHA) to mediate toxin retention on the bacterial surface (Zaretzky et al. 2002). Interestingly, target cell intoxication is not dependent on surface-associated CyaA and instead newly secreted CyaA is necessary (Gray et al. 2004). However, unlike PT, which acts conventionally as a soluble factor (described above), exogenous administration of recombinant CyaA fails to rescue a “wild type” B. pertussis phenotype in mice infected with a cyaA-deficient strain (Carbonetti et al. 2005). In vitro studies have demonstrated rapid aggregation of CyaA in solution (Rogel et al. 1991). Hence, CyaA is hypothesized to be a short-lived toxin acting in close proximity to the bacterium (Vojtova et al. 2006) but the exact role of soluble vs bacterial-associated CyaA remains to be determined. Given that CyaA functions at the site of the bacterial-host interface, this toxin does not contribute to systemic pathologies during B. pertussis infection.

At the site of infection, locally secreted CyaA performs a number of functions to subvert host cell biology and potentiate cell death. Upon insertion into the target cell membrane, CyaA takes on one of two conformations (Osickova et al. 1999). It is proposed that a monomeric form of CyaA acts to translocate the catalytic AC enzyme domain into the host cell cytosol, whilst oligomerization of CyaA potentiates the formation of a hemolytic pore and that actions performed by the CyaA monomer improve the efficacy of the hemolysin moiety (Osickova et al. 1999; Fiser et al. 2012). The exact mechanism by which CyaA translocates its AC domain into the host cytosol is still under investigation. Recently, recombinant CyaA has been shown to display calcium-dependent phospholipase A (PLA) activity and this mechanism has been associated with CyaA-induced cytotoxicity in macrophages and macrophage release of free fatty acids (Gonzalez-Bullon et al. 2017). Ostolaza et al. suggest that CyaA-PLA acts to remodel the host cell membrane (releasing membrane fatty acids and lysophospholipids), generating a “toroidal pore” that facilitates transport of the AC domain (Ostolaza et al. 2017). However, whether CyaA itself, and not an E. coli-derived contaminant, possesses PLA activity has been contested (Masin et al. 2018; Ostolaza 2018), hence more studies are required to elucidate the contribution of PLA activity to CyaA biology. Translocation of the AC domain is concomitant with Ca2+ influx in the host cell (Fiser et al. 2007). This process is required to activate calpain-mediated processing of CyaA and liberation of the AC domain into the cytosol (Bumba et al. 2010; Uribe et al. 2013). In addition, CyaA-driven Ca2+ influx alters endocytic trafficking in the host cell membrane and limits macropinocytic removal of pore-forming oligomerized CyaA (Fiser et al. 2012). In the cytosol, AC binds host calmodulin and catalyzes the rapid, unregulated conversion of cytoplasmic ATP into cAMP (Wolff et al. 1980; Hanski and Farfel 1985; Guo et al. 2005). CyaA-induced accumulation of cAMP prevents bactericidal activities of phagocytes by inhibiting oxidative burst and phagocytosis (Confer and Eaton 1982; Pearson et al. 1987; Kamanova et al. 2008; Friedman et al. 1987; Cerny et al. 2015), and modulates innate immune cell activation by inhibiting phagocyte maturation and suppressing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Boyd et al. 2005; Njamkepo et al. 2000; Ross et al. 2004; Fedele et al. 2010; Spensieri et al. 2006). In addition, elevated cAMP levels inhibit the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and neutrophil apoptosis (Eby et al. 2014), whilst also promoting B. pertussis intracellular survival in macrophages and macrophage apoptosis (Valdez et al. 2016; Hewlett et al. 2006; Ahmad et al. 2016). In parallel, the oligomerized conformation of CyaA generates a cation-selective pore that induces potassium ion efflux from nucleated cells (Gray et al. 1998; Osickova et al. 1999). This activity promotes cell death caused by both apoptosis and necrosis (Basler et al. 2006; Khelef et al. 1993; Hewlett et al. 2006). In addition, CyaA-promoted potassium efflux induces IL-1β production by dendritic cells via activation of caspase-I and NALP3-containing inflammasome complex (Dunne et al. 2010) and activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) signaling (Masin et al. 2015; Svedova et al. 2016). Hence, taken together CyaA uses both its AC domain and hemolysin moiety to induce cellular dysfunctions that promote bacterial survival and inhibit phagocyte-mediated bacterial clearance.

2.2.2. Effects of CyaA on B. pertussis colonization and host immune responses

CyaA was characterized as a toxin in 1982, when it was shown that CyaA inhibited phagocytosis and oxidative burst by human neutrophils (Confer and Eaton 1982). Since that time, CyaA has been found to specifically target myeloid phagocytic cells, using CD11b/CD18 integrin (known as αMβ2 integrin or complement receptor 3, CR3) on the host cell surface as a receptor (Guermonprez et al. 2001). CyaA can also penetrate lipid bilayers in the absence of this receptor (Martin et al. 2004; Szabo et al. 1994) and intoxicate most cells but with reduced efficacy (Gordon et al. 1989; Gray et al. 1999; Eby et al. 2010; Bassinet et al. 2000; Hanski and Farfel 1985). In vivo, CyaA acts primarily on phagocytic cells to inhibit clearance and promote B. pertussis colonization (Gueirard et al. 1998; Harvill et al. 1999). However, CyaA-induced apoptotic cell death of bronchopulmonary cells is also described following administration of airway-isolated bacteria (Gueirard et al. 1998).

A role for CyaA in bacterial colonization was first described by Weiss et al. (Weiss et al. 1983). In that study, B. pertussis mutants not expressing CyaA were found to be non-lethal in a histamine-sensitizing in vivo mouse assay (Weiss et al. 1983). Further to this, expression of CyaA was found to be required for colonization and lethality of B. pertussis in infant mice (Goodwin and Weiss 1990; Weiss and Goodwin 1989). Both AC activity and the hemolysin moiety have been shown to be required for competent colonization and virulence by B. pertussis (Gross et al. 1992; Khelef et al. 1992). Indeed, in a later study using B. pertussis strains that express CyaA deficient in AC or hemolysin activity, it was determined that actions performed by the AC domain were required for bacterial colonization and persistence in mouse lungs, whereas the hemolysin moiety was not involved in colonization (Skopova et al. 2017). However, the hemolysin moiety did contribute to B. pertussis-induced lethality, penetration of B. pertussis across the epithelial lining and recruitment of myeloid phagocytic cells into B. pertussis-infected tissue (Skopova et al. 2017). Hence, the pore-forming ability of CyaA is not required for bacterial persistence but contributes to B. pertussis-associated pathology.

2.3. CyaA as a pertussis vaccine component

Whole-cell formulations of pertussis vaccines (wP) displayed AC activity (Hewlett et al. 1977) and mass spectrometry analysis of wP detected the presence of CyaA (Boehm et al. 2018). However, the aP does not contain CyaA antigens. In studies using monoclonal antibodies and serum from convalescent individuals, it was found that antibodies against CyaA promote B. pertussis phagocytosis by neutrophils, validating one potentially beneficial effect of including a CyaA antigen in an aPV (Weingart and Weiss 2000; Weingart et al. 2000; Mobberley-Schuman et al. 2003). In addition, CyaA antibody-mediated neutrophil clearance of B. pertussis was shown to be important in an immune mouse challenge model (Andreasen and Carbonetti 2009). Given the potential for CyaA-mediated toxicity, current studies on developing CyaA as a vaccine antigen have focused of delineating the minimal essential regions of CyaA that confer protective immunity. Studies by Wang et al. show that the RTX domain of CyaA was sufficient to generate neutralizing antibodies and may represent an alternative to the use of full length CyaA (Wang et al. 2015). Indeed, in a mouse model, inclusion of the RTX domain in aP resulted in enhanced bacterial clearance after B. pertussis challenge, increased production of anti-PT antibodies, decreased production of proinflammatory cytokines and decreased recruitment of total macrophages (Boehm et al. 2018).

CyaA also displays an adjuvant effect in mice during immunization, with AC enzymatically inactive-CyaA generating greater and more potent adaptive immune responses than active CyaA (Orr et al. 2007; Cheung et al. 2006). When used as an adjuvant, CyaA induces the generation of antigen-specific Th17 cells by a pore-forming dependent mechanism (Dunne et al. 2010). Th17 cells mediate protective immunity to B. pertussis (Ross et al. 2013), hence generation of vaccine antigens that include specific functional regions of CyaA may prove beneficial in an acellular vaccine formulation.

3. TRACHEAL CYTOTOXIN

3.1. Background

Tracheal cytotoxin (TCT) is a peptidoglycan (PGN) fragment released by B. pertussis. PGN recycling is a process utilized by bacteria during cell division. First PGN is converted into its constituent parts, which are then available to the bacteria to be utilized in the synthesis of more PGN or for use as an energy source (Uehara and Park 2008). Bacteria producing PGN molecules containing diaminopimelic acid (DAP), or DAP-type PGNs, such as Bacillus subtilis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Lactobacillus acidophilus and B. pertussis, lose large amounts (25–50%) of the DAP from their cell wall to their growth media compared to E. coli (6%) (Mauck et al. 1971; Boothby et al. 1973; Goodell 1985; Goodell et al. 1978; Chaloupka and Strnadova 1972; Hebeler and Young 1976). The inner membrane permease AmpG is a key component in this process (Jacobs et al. 1994). In Bordetella however, this transporter is defective, resulting in accumulation of extracellular fragments of PGN (Cookson et al. 1989a; Rosenthal et al. 1987; Mielcarek et al. 2006). Over 95% of these PGN fragments released from Bordetella are of the structure N-acetylglucosaminyl-1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanine-D-glutamyl-mesoDAP-D-alanine. This released monomeric fragment of PGN constitutes the virulence factor TCT. TCT is a 921 dalton disaccharide tetrapeptide PGN fragment. The anhydrous nature of the acetylmuramyl saccharide indicates that TCT is not just an accidentally released PGN fragment (which would contain reducing as opposed to anhydrous muramic acid residues) (Goldman and Cookson 1988). This finding led to the hypothesis that TCT is processed via an as yet unidentified murein transglycosylase.

3.2. TCT in pathogenesis

Host pattern recognition receptors trigger innate responses to PGN fragments. Following its release from the bacterial cell wall, non-ciliated cells of the airway epithelium internalize TCT (Flak and Goldman, 2001, (Flak et al. 2000; Flak and Goldman 1999). TCT is trafficked to the cytosol via PGN transporter Slc46A2 (Paik et al. 2017) where it is recognized by the pattern recognition receptor Nod1 (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain protein 1) (Magalhaes et al. 2005). This leads to the activation of downstream NF-kB signaling (Paik et al. 2017) and IL-1α production by non-ciliated cells of the murine airway epithelium, in a synergistic manner with LPS (Flak et al. 2000). Interestingly, neither TCT nor Bordetella lipooligosaccharide (LOS) elicit strong IL-1α production alone, but the combination of the two is a potent producer (Flak et al. 2000). Downstream effects of this activity include the production of nitric oxide (NO), which diffuses to neighboring ciliated cells causing cell death (Flak and Goldman 1999). In addition to promoting NO and IL-1α mediated inflammation, TCT inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis (Cundell et al. 1994) preventing optimal immune responses.

In Drosophila, TCT triggers the activation of the IMD pathway following cytosolic recognition by PGN recognition protein PGRP-LE (Lim et al. 2006). Interestingly, mammalian PGN recognition protein 4 (PGLYRP4) has a protective role against TCT-mediated pathogenesis (Skerry et al. 2019). Hypersecretion of TCT, using mutant strains lacking PGN recycling molecule AmpG, or deficiency in PGLYRP4 causes increased early lung pathology in mice, suggesting that PGLYRP4 limits early TCT-induced inflammation (Skerry et al. 2019).

Each member of the pathogenic Bordetellae produce a chemically identical TCT molecule (Cookson et al. 1989b; Folkening et al. 1987; Gentry-Weeks et al. 1988; Goldman and Cookson 1988). Additionally, all of the pathogenic Bordetellae induce a similar respiratory pathology typified by the destruction of the ciliated cells of the upper airways, in hosts ranging from humans (Paddock et al. 2008) to dogs (Oskouizadeh 2011; Bemis 1992) and turkeys (Arp and Fagerland 1987) and TCT is the only factor capable of replicating this ciliated cell extrusion that is the hallmark of the bordetelloses (Cookson et al. 1989a; Endoh et al. 1986; Goldman et al. 1982; Goldman and Cookson 1988).

TCT analogues in other bacteria are associated with similar pathologies, e.g. Neisseria gonorrhoeae-released PGN fragments have been associated with damage to the mucosa of human fallopian tubes (Melly et al. 1984). PGN monomers released from Vibrio fischeri induce the regression of ciliated fields of Euprymna scolopes (Doino and McFall-Ngai 1995; Montgomery and McFall-Ngai 1994).

3.3. TCT in vaccination

The transition from the use of the whole cell to acellular pertussis vaccine has been associated with a reduction in the duration of immunity (Chen and He 2017). The whole cell vaccine, derived from intact B. pertussis organisms, likely contained TCT, even if only in the form of intact PGN. The acellular vaccine consists of recombinant subunit proteins of B. pertussis but does not contain TCT or PGN. Freund’s complete adjuvant, a potent contributor to vaccine responses, contains muramyl peptides like TCT (Kotani et al. 1986). It has therefore been speculated that the loss of TCT in acellular vaccine formulations contributed to their waning immunogenicity (Goldman and Cookson 1988). Candidate live attenuated B. pertussis vaccine BPZE1 utilizes the E. coli PGN recycling machinery, AmpG, resulting in <1% TCT activity (Mielcarek et al. 2006). However, it contains the full complement of Bordetella PGN and therefore the potential adjuvanticity. Loss of PT, TCT and dermonecrotic toxin (DNT) resulted in a vaccine strain which successfully colonized hosts and elicited a protective immune response, without the associated pathophysiology of “wild-type” infection (Skerry and Mahon 2011; Skerry et al. 2009; Feunou et al. 2010).

TCT is identical in structure to slow wave sleep promoting factor FSu (Martin et al. 1984). In rabbits, FSu has been shown to induce excess slow-wave sleep following intraventricular infusion of picomolar concentrations (Krueger et al. 1982). The sleep-promoting effects of this factor are separate from its immunomodulatory potential (Krueger and Karnovsky 1987). These somnogenic qualities, along with the small size of TCT, led to the untested hypothesis that TCT may have been the reason behind the whole-cell vaccine-associated drowsiness (Goldman and Cookson 1988).

CONCLUSION

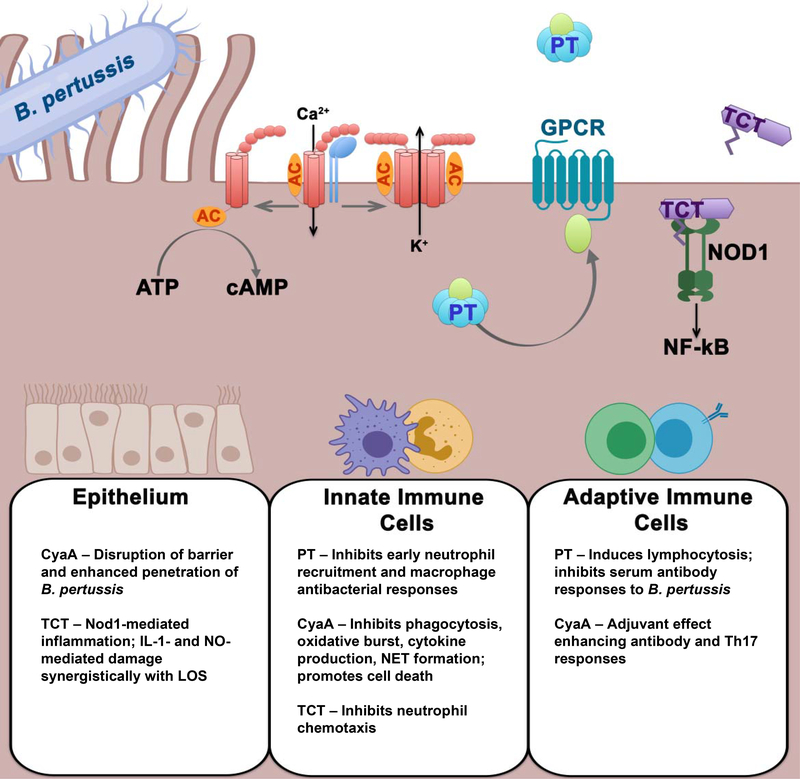

As we describe here, much of the pathogenesis of pertussis is attributable to the major secreted toxins, PT, CyaA and TCT, produced during B. pertussis infection (their activities and effects are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1). Although there is still much to be learned about their activities and roles, it is clear that these toxins collectively suppress protective immune responses while exacerbating damaging pathologies in the respiratory tract and (in the case of PT) other organ systems. Further understanding of these toxin activities and the affected host responses will be important in the development of optimal therapeutics and vaccines to treat and prevent pertussis.

Figure 1.

Summary of pertussis toxin (PT), adenylate cyclase toxin (CyaA) and tracheal cytotoxin (TCT) activities on cells.

Table 1.

Effects and activities of the major Bordetella pertussis toxins.

| Agent | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pertussis Toxin | ADP-Ribosylation of Gi/α class GPCRs Induction of leukocytosis Inhibition of chemokine signaling Cardiac issues Reduction of vascular barrier integrity Histamine sensitization Insulinemia/hypoglycemia Prevention of cough cessation Promotes colonization Inhibits early defense Inhibits macrophage antibacterial responses Promotes lung inflammation |

Katada et al. 2012 Morse and Morse 1976, Munoz et al. 1981, Hinds et al 1996, Nogimori et al 1984 Pham et al. 2008, Beck et al. 2014 Grimm et al. 1998, Wainford et al 2008, Adamson et al. 1993, Zheng et al. 2005 Dudek et al. 2007 Munoz et al. 1981 Yajima et al. 1978 Maher et al. 2011 Carbonetti et al. 2003, Connelly et al. 2012 Carbonetti et al. 2003, Carbonetti et al. 2005, Kirimanjeswara et al. 2008, Andreasen and Carbonetti 2008 Carbonetti et al. 2007 Connelly et al. 2012, Khelef et al. 1994, Andreasen et al. 2009 |

| Adenylate cyclase toxin | Hemolytic pore formation cAMP intoxication Inhibition of oxidative burst and phagocytosis Suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines Inhibition of NET formation Induction of potassium ion efflux Promotes cell death Activation of MAP and JNK signaling Promotes Colonization Inhibits clearance |

Osickova et al. 1999, Fisher et al. 2012 Wolff et al.1980, Hanski and Furfel 1985, Guo et al. 2005 Confer and Eaton et al. 1982, Pearson et al. 1987, Kamanova et al. 2008, Friedman et al. 1987, Cerny et al. 2015 Boyd et al. 2005, Njakempo et al. 2000, Ross et al. 2004 Eby et al. 2014 Gray et al. 1998, Osickova et al. 1999 Basler et al. 2006, Khelef et al. 1993, Hewlett et al. 2006 Masin et al.2015, Svedova et al. 2016 Weiss et al. 1989 Gueirard et al. 1998 |

| Tracheal Cytotoxin | Stimulation of Nod1 Nf-kB activation IL-1a production Ciliated cell death Inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis |

Magalhaes et al. 2005 Paik et al. 2017 Flak et al 2000 Flak and Goldman 1999 Cundell et al. 1994 |

REFERENCES

- Adamson PB, Hull SS Jr., Vanoli E, De Ferrari GM, Wisler P, Foreman RD, Watanabe AM, Schwartz PJ (1993) Pertussis toxin-induced ADP ribosylation of inhibitor G proteins alters vagal control of heart rate in vivo. The American journal of physiology 265 (2 Pt 2):H734–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal N, Lamichhane G, Gupta R, Nolan S, Bishai WR (2009) Cyclic AMP intoxication of macrophages by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis adenylate cyclase. Nature 460 (7251):98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad JN, Cerny O, Linhartova I, Masin J, Osicka R, Sebo P (2016) cAMP signalling of Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin through the SHP-1 phosphatase activates the BimEL-Bax pro-apoptotic cascade in phagocytes. Cell Microbiol 18 (3):384–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen C, Carbonetti NH (2008) Pertussis toxin inhibits early chemokine production to delay neutrophil recruitment in response to Bordetella pertussis respiratory tract infection in mice. Infect Immun 76 (11):5139–5148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen C, Carbonetti NH (2009) Role of neutrophils in response to Bordetella pertussis infection in mice. Infect Immun 77 (3):1182–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen C, Powell DA, Carbonetti NH (2009) Pertussis toxin stimulates IL-17 production in response to Bordetella pertussis infection in mice. PLoS One 4 (9):e7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimoto H, Tanuma N, Jee Y, Miyazawa T, Shima K, Matsumoto Y (2000) Analysis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis induced in F344 rats by pertussis toxin administration. Journal of neuroimmunology 104 (1):15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arp LH, Fagerland JA (1987) Ultrastructural pathology of Bordetella avium infection in turkeys. Vet Pathol 24 (5):411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargatze RF, Butcher EC (1993) Rapid G protein-regulated activation event involved in lymphocyte binding to high endothelial venules. The Journal of experimental medicine 178 (1):367–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M, Masin J, Osicka R, Sebo P (2006) Pore-forming and enzymatic activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin synergize in promoting lysis of monocytes. Infect Immun 74 (4):2207–2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassinet L, Gueirard P, Maitre B, Housset B, Gounon P, Guiso N (2000) Role of adhesins and toxins in invasion of human tracheal epithelial cells by Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun 68 (4):1934–1941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck TC, Gomes AC, Cyster JG, Pereira JP (2014) CXCR4 and a cell-extrinsic mechanism control immature B lymphocyte egress from bone marrow. The Journal of experimental medicine 211 (13):2567–2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemis DA (1992) Bordetella and Mycoplasma respiratory infections in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 22 (5):1173–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J, Basivireddy J, Kollar A, Biron KE, Reickmann P, Jefferies WA, McQuaid S (2010) Blood-brain barrier disruption and enhanced vascular permeability in the multiple sclerosis model EAE. Journal of neuroimmunology 229 (1–2):180–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz R, Maier E, Ladant D, Ullmann A, Sebo P (1994) Adenylate cyclase toxin (CyaA) of Bordetella pertussis. Evidence for the formation of small ion-permeable channels and comparison with HlyA of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 269 (44):27231–27239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm DT, Hall JM, Wong TY, DiVenere AM, Sen-Kilic E, Bevere JR, Bradford SD, Blackwood CB, Elkins CM, DeRoos KA, Gray MC, Cooper CG, Varney ME, Maynard JA, Hewlett EL, Barbier M, Damron FH (2018) Evaluation of Adenylate Cyclase Toxoid Antigen in Acellular Pertussis Vaccines by Using a Bordetella pertussis Challenge Model in Mice. Infect Immun 86 (10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby D, Daneo-Moore L, Higgins ML, Coyette J, Shockman GD (1973) Turnover of bacterial cell wall peptidoglycans. The Journal of biological chemistry 248 (6):2161–2169 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchez V, Brun D, Cantinelli T, Dore G, Njamkepo E, Guiso N (2009) First report and detailed characterization of B. pertussis isolates not expressing Pertussis Toxin or Pertactin. Vaccine 27 (43):6034–6041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd AP, Ross PJ, Conroy H, Mahon N, Lavelle EC, Mills KH (2005) Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin modulates innate and adaptive immune responses: distinct roles for acylation and enzymatic activity in immunomodulation and cell death. J Immunol 175 (2):730–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruss JB, Malley R, Halperin S, Dobson S, Dhalla M, McIver J, Siber GR (1999) Treatment of severe pertussis: a study of the safety and pharmacology of intravenous pertussis immunoglobulin. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 18 (6):505–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumba L, Masin J, Fiser R, Sebo P (2010) Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin mobilizes its beta2 integrin receptor into lipid rafts to accomplish translocation across target cell membrane in two steps. PLoS Pathog 6 (5):e1000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumba L, Masin J, Macek P, Wald T, Motlova L, Bibova I, Klimova N, Bednarova L, Veverka V, Kachala M, Svergun DI, Barinka C, Sebo P (2016) Calcium-Driven Folding of RTX Domain beta-Rolls Ratchets Translocation of RTX Proteins through Type I Secretion Ducts. Mol Cell 62 (1):47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH (2010) Pertussis toxin and adenylate cyclase toxin: key virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis and cell biology tools. Future microbiology 5 (3):455–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH (2016) Pertussis Leukocytosis: Mechanisms, Clinical Relevance and Treatment. Pathogens and disease. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftw087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH, Artamonova GV, Andreasen C, Bushar N (2005) Pertussis toxin and adenylate cyclase toxin provide a one-two punch for establishment of Bordetella pertussis infection of the respiratory tract. Infect Immun 73 (5):2698–2703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH, Artamonova GV, Andreasen C, Dudley E, Mays RM, Worthington ZE (2004) Suppression of serum antibody responses by pertussis toxin after respiratory tract colonization by Bordetella pertussis and identification of an immunodominant lipoprotein. Infect Immun 72 (6):3350–3358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH, Artamonova GV, Mays RM, Worthington ZE (2003) Pertussis toxin plays an early role in respiratory tract colonization by Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun 71 (11):6358–6366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonetti NH, Artamonova GV, Van Rooijen N, Ayala VI (2007) Pertussis toxin targets airway macrophages to promote Bordetella pertussis infection of the respiratory tract. Infect Immun 75 (4):1713–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerny O, Kamanova J, Masin J, Bibova I, Skopova K, Sebo P (2015) Bordetella pertussis Adenylate Cyclase Toxin Blocks Induction of Bactericidal Nitric Oxide in Macrophages through cAMP-Dependent Activation of the SHP-1 Phosphatase. J Immunol 194 (10):4901–4913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka J, Strnadova M (1972) Turnover of murein in a diaminopimelic acid dependent mutant of Escherichia coli. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 17 (6):446–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay R, Mani AM, Singh NK, Rao GN (2018) Resolvin D1 blocks H2O2-mediated inhibitory crosstalk between SHP2 and PP2A and suppresses endothelial-monocyte interactions. Free Radic Biol Med 117:119–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, He Q (2017) Immune persistence after pertussis vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother 13 (4):744–756. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1259780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GY, Xing D, Prior S, Corbel MJ, Parton R, Coote JG (2006) Effect of different forms of adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis on protection afforded by an acellular pertussis vaccine in a murine model. Infect Immun 74 (12):6797–6805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Confer DL, Eaton JW (1982) Phagocyte impotence caused by an invasive bacterial adenylate cyclase. Science 217 (4563):948–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly CE, Sun Y, Carbonetti NH (2012) Pertussis toxin exacerbates and prolongs airway inflammatory responses during Bordetella pertussis infection. Infect Immun 80 (12):4317–4332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson BT, Cho HL, Herwaldt LA, Goldman WE (1989a) Biological activities and chemical composition of purified tracheal cytotoxin of Bordetella pertussis. Infection and immunity 57 (7):2223–2229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson BT, Tyler AN, Goldman WE (1989b) Primary structure of the peptidoglycan-derived tracheal cytotoxin of Bordetella pertussis. Biochemistry 28 (4):1744–1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutte L, Locht C (2015) Investigating pertussis toxin and its impact on vaccination. Future microbiology 10:241–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cundell DR, Kanthakumar K, Taylor GW, Goldman WE, Flak T, Cole PJ, Wilson R (1994) Effect of tracheal cytotoxin from Bordetella pertussis on human neutrophil function in vitro. Infection and immunity 62 (2):639–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalby T, Andersen PH, Hoffmann S (2016) Epidemiology of pertussis in Denmark, 1995 to 2013. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 21 (36). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doino JA, McFall-Ngai MJ (1995) A Transient Exposure to Symbiosis-Competent Bacteria Induces Light Organ Morphogenesis in the Host Squid. Biol Bull 189 (3):347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek SM, Camp SM, Chiang ET, Singleton PA, Usatyuk PV, Zhao Y, Natarajan V, Garcia JG (2007) Pulmonary endothelial cell barrier enhancement by FTY720 does not require the S1P1 receptor. Cellular signalling 19 (8):1754–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne A, Ross PJ, Pospisilova E, Masin J, Meaney A, Sutton CE, Iwakura Y, Tschopp J, Sebo P, Mills KH (2010) Inflammasome activation by adenylate cyclase toxin directs Th17 responses and protection against Bordetella pertussis. J Immunol 185 (3):1711–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby JC, Ciesla WP, Hamman W, Donato GM, Pickles RJ, Hewlett EL, Lencer WI (2010) Selective translocation of the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin across the basolateral membranes of polarized epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 285 (14):10662–10670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby JC, Gray MC, Hewlett EL (2014) Cyclic AMP-mediated suppression of neutrophil extracellular trap formation and apoptosis by the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Infect Immun 82 (12):5256–5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Baya A, Linnemann R, von Olleschik-Elbheim L, Robenek H, Schmidt MA (1997) Endocytosis and retrograde transport of pertussis toxin to the Golgi complex as a prerequisite for cellular intoxication. European journal of cell biology 73 (1):40–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh M, Amitani M, Nakase Y (1986) Purification and characterization of heat-labile toxin from Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microbiol Immunol 30 (7):659–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh M, Takezawa T, Nakase Y (1980) Adenylate cyclase activity of Bordetella organisms. I. Its production in liquid medium. Microbiol Immunol 24 (2):95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst K, Eberhardt N, Mittler AK, Sonnabend M, Anastasia A, Freisinger S, Schiene-Fischer C, Malesevic M, Barth H (2018) Pharmacological Cyclophilin Inhibitors Prevent Intoxication of Mammalian Cells with Bordetella pertussis Toxin. Toxins 10 (5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele G, Bianco M, Debrie AS, Locht C, Ausiello CM (2011) Attenuated Bordetella pertussis vaccine candidate BPZE1 promotes human dendritic cell CCL21-induced migration and drives a Th1/Th17 response. J Immunol 186 (9):5388–5396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele G, Spensieri F, Palazzo R, Nasso M, Cheung GY, Coote JG, Ausiello CM (2010) Bordetella pertussis commits human dendritic cells to promote a Th1/Th17 response through the activity of adenylate cyclase toxin and MAPK-pathways. PLoS One 5 (1):e8734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feunou PF, Kammoun H, Debrie AS, Mielcarek N, Locht C (2010) Long-term immunity against pertussis induced by a single nasal administration of live attenuated B. pertussis BPZE1. Vaccine 28 (43):7047–7053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finck-Barbancon V, Barbieri JT (1996) Preferential processing of the S1 subunit of pertussis toxin that is bound to eukaryotic cells. Molecular microbiology 22 (1):87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser R, Masin J, Basler M, Krusek J, Spulakova V, Konopasek I, Sebo P (2007) Third activity of Bordetella adenylate cyclase (AC) toxin-hemolysin. Membrane translocation of AC domain polypeptide promotes calcium influx into CD11b+ monocytes independently of the catalytic and hemolytic activities. J Biol Chem 282 (5):2808–2820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser R, Masin J, Bumba L, Pospisilova E, Fayolle C, Basler M, Sadilkova L, Adkins I, Kamanova J, Cerny J, Konopasek I, Osicka R, Leclerc C, Sebo P (2012) Calcium influx rescues adenylate cyclase-hemolysin from rapid cell membrane removal and enables phagocyte permeabilization by toxin pores. PLoS Pathog 8 (4):e1002580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flak TA, Goldman WE (1999) Signalling and cellular specificity of airway nitric oxide production in pertussis. Cell Microbiol 1 (1):51–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flak TA, Heiss LN, Engle JT, Goldman WE (2000) Synergistic epithelial responses to endotoxin and a naturally occurring muramyl peptide. Infection and immunity 68 (3):1235–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkening WJ, Nogami W, Martin SA, Rosenthal RS (1987) Structure of Bordetella pertussis peptidoglycan. J Bacteriol 169 (9):4223–4227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RL, Fiederlein RL, Glasser L, Galgiani JN (1987) Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase: effects of affinity-purified adenylate cyclase on human polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions. Infect Immun 55 (1):135–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry-Weeks CR, Cookson BT, Goldman WE, Rimler RB, Porter SB, Curtiss R, 3rd (1988) Dermonecrotic toxin and tracheal cytotoxin, putative virulence factors of Bordetella avium. Infection and immunity 56 (7):1698–1707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser P, Ladant D, Sezer O, Pichot F, Ullmann A, Danchin A (1988a) The calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase of Bordetella pertussis: cloning and expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 2 (1):19–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser P, Sakamoto H, Bellalou J, Ullmann A, Danchin A (1988b) Secretion of cyclolysin, the calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase-haemolysin bifunctional protein of Bordetella pertussis. EMBO J 7 (12):3997–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman WE, Cookson BT (1988) Structure and functions of the Bordetella tracheal cytotoxin. Tokai J Exp Clin Med 13 Suppl:187–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman WE, Klapper DG, Baseman JB (1982) Detection, isolation, and analysis of a released Bordetella pertussis product toxic to cultured tracheal cells. Infection and immunity 36 (2):782–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Bullon D, Uribe KB, Martin C, Ostolaza H (2017) Phospholipase A activity of adenylate cyclase toxin mediates translocation of its adenylate cyclase domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114 (33):E6784–E6793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell EW (1985) Recycling of murein by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 163 (1):305–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell EW, Fazio M, Tomasz A (1978) Effect of benzylpenicillin on the synthesis and structure of the cell envelope of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 13 (3):514–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin MS, Weiss AA (1990) Adenylate cyclase toxin is critical for colonization and pertussis toxin is critical for lethal infection by Bordetella pertussis in infant mice. Infect Immun 58 (10):3445–3447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon VM, Young WW Jr., Lechler SM, Gray MC, Leppla SH, Hewlett EL (1989) Adenylate cyclase toxins from Bacillus anthracis and Bordetella pertussis. Different processes for interaction with and entry into target cells. J Biol Chem 264 (25):14792–14796 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M, Szabo G, Otero AS, Gray L, Hewlett E (1998) Distinct mechanisms for K+ efflux, intoxication, and hemolysis by Bordetella pertussis AC toxin. J Biol Chem 273 (29):18260–18267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MC, Donato GM, Jones FR, Kim T, Hewlett EL (2004) Newly secreted adenylate cyclase toxin is responsible for intoxication of target cells by Bordetella pertussis. Molecular microbiology 53 (6):1709–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MC, Ross W, Kim K, Hewlett EL (1999) Characterization of binding of adenylate cyclase toxin to target cells by flow cytometry. Infect Immun 67 (9):4393–4399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm M, Gsell S, Mittmann C, Nose M, Scholz H, Weil J, Eschenhagen T (1998) Inactivation of (Gialpha) proteins increases arrhythmogenic effects of beta-adrenergic stimulation in the heart. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 30 (10):1917–1928. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross MK, Au DC, Smith AL, Storm DR (1992) Targeted mutations that ablate either the adenylate cyclase or hemolysin function of the bifunctional cyaA toxin of Bordetella pertussis abolish virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89 (11):4898–4902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueirard P, Druilhe A, Pretolani M, Guiso N (1998) Role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin in alveolar macrophage apoptosis during Bordetella pertussis infection in vivo. Infect Immun 66 (4):1718–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guermonprez P, Khelef N, Blouin E, Rieu P, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Guiso N, Ladant D, Leclerc C (2001) The adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis binds to target cells via the alpha(M)beta(2) integrin (CD11b/CD18). J Exp Med 193 (9):1035–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Shen Y, Lee YS, Gibbs CS, Mrksich M, Tang WJ (2005) Structural basis for the interaction of Bordetella pertussis adenylyl cyclase toxin with calmodulin. The EMBO journal 24 (18):3190–3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett M, Guo L, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Hewlett EL (1994) Internal lysine palmitoylation in adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. Science 266 (5184):433–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett M, Walker CB, Guo L, Gray MC, Van Cuyk S, Ullmann A, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Hewlett EL, Sebo P (1995) Hemolytic, but not cell-invasive activity, of adenylate cyclase toxin is selectively affected by differential fatty-acylation in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 270 (35):20250–20253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanski E, Farfel Z (1985) Bordetella pertussis invasive adenylate cyclase. Partial resolution and properties of its cellular penetration. J Biol Chem 260 (9):5526–5532 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvill ET, Cotter PA, Yuk MH, Miller JF (1999) Probing the function of Bordetella bronchiseptica adenylate cyclase toxin by manipulating host immunity. Infect Immun 67 (3):1493–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazes B, Boodhoo A, Cockle SA, Read RJ (1996) Crystal structure of the pertussis toxin-ATP complex: a molecular sensor. J Mol Biol 258 (4):661–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebeler BH, Young FE (1976) Chemical composition and turnover of peptidoglycan in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol 126 (3):1180–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Canning BJ (2010) Coughing precipitated by Bordetella pertussis infection. Lung 188 Suppl 1:S73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett EL, Donato GM, Gray MC (2006) Macrophage cytotoxicity produced by adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis: more than just making cyclic AMP! Molecular microbiology 59 (2):447–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett EL, Manclark CR, Wolff J (1977) Adenyl cyclase in Bordetella pertussis vaccines. J Infect Dis 136 Suppl:S216–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett EL, Urban MA, Manclark CR, Wolff J (1976) Extracytoplasmic adenylate cyclase of Bordetella pertussis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 73 (6):1926–1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds PW, 2nd, Yin C, Salvato MS, Pauza CD (1996) Pertussis toxin induces lymphocytosis in rhesus macaques. J Med Primatol 25 (6):375–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge G, Hodge S, Markus C, Lawrence A, Han P (2003) A marked decrease in L-selectin expression by leucocytes in infants with Bordetella pertussis infection: leucocytosis explained? Respirology 8 (2):157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudnall SD, Molina CP (2000) Marked increase in L-selectin-negative T cells in neonatal pertussis. The lymphocytosis explained? American journal of clinical pathology 114 (1):35–40. d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs C, Huang LJ, Bartowsky E, Normark S, Park JT (1994) Bacterial cell wall recycling provides cytosolic muropeptides as effectors for beta-lactamase induction. The EMBO journal 13 (19):4684–4694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo YY, Lee JY, Park CK (2016) Resolvin E1 Inhibits Substance P-Induced Potentiation of TRPV1 in Primary Sensory Neurons. Mediators of inflammation 2016:5259321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamanova J, Kofronova O, Masin J, Genth H, Vojtova J, Linhartova I, Benada O, Just I, Sebo P (2008) Adenylate cyclase toxin subverts phagocyte function by RhoA inhibition and unproductive ruffling. J Immunol 181 (8):5587–5597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapil P, Papin JF, Wolf RF, Zimmerman LI, Wagner LD, Merkel TJ (2018) Maternal Vaccination With a Monocomponent Pertussis Toxoid Vaccine Is Sufficient to Protect Infants in a Baboon Model of Whooping Cough. The Journal of infectious diseases 217 (8):1231–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katada T (2012) The inhibitory G protein G(i) identified as pertussis toxin-catalyzed ADP-ribosylation. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin 35 (12):2103–2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khelef N, Bachelet CM, Vargaftig BB, Guiso N (1994) Characterization of murine lung inflammation after infection with parental Bordetella pertussis and mutants deficient in adhesins or toxins. Infect Immun 62 (7):2893–2900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khelef N, Sakamoto H, Guiso N (1992) Both adenylate cyclase and hemolytic activities are required by Bordetella pertussis to initiate infection. Microb Pathog 12 (3):227–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khelef N, Zychlinsky A, Guiso N (1993) Bordetella pertussis induces apoptosis in macrophages: role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect Immun 61 (10):4064–4071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirimanjeswara GS, Agosto LM, Kennett MJ, Bjornstad ON, Harvill ET (2005) Pertussis toxin inhibits neutrophil recruitment to delay antibody-mediated clearance of Bordetella pertussis. J Clin Invest 115 (12):3594–3601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotani S, Tsujimoto M, Koga T, Nagao S, Tanaka A, Kawata S (1986) Chemical structure and biological activity relationship of bacterial cell walls and muramyl peptides. Fed Proc 45 (11):2534–2540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy S, Recchiuti A, Chiang N, Yacoubian S, Lee CH, Yang R, Petasis NA, Serhan CN (2010) Resolvin D1 binds human phagocytes with evidence for proresolving receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (4):1660–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger JM, Karnovsky ML (1987) Sleep and the immune response. Ann N Y Acad Sci 496:510–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger JM, Pappenheimer JR, Karnovsky ML (1982) Sleep-promoting effects of muramyl peptides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 79 (19):6102–6106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BD, Serhan CN (2014) Resolution of acute inflammation in the lung. Annual review of physiology 76:467–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JH, Kim MS, Kim HE, Yano T, Oshima Y, Aggarwal K, Goldman WE, Silverman N, Kurata S, Oh BH (2006) Structural basis for preferential recognition of diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan by a subset of peptidoglycan recognition proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry 281 (12):8286–8295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox JF, Hachicha M, Takano T, Petasis NA, Fokin VV, Serhan CN (1997) Lipoxin A4 stable analogs are potent mimetics that stimulate human monocytes and THP-1 cells via a G-protein-linked lipoxin A4 receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry 272 (11):6972–6978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhaes JG, Philpott DJ, Nahori MA, Jehanno M, Fritz J, Le Bourhis L, Viala J, Hugot JP, Giovannini M, Bertin J, Lepoivre M, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Sansonetti PJ, Girardin SE (2005) Murine Nod1 but not its human orthologue mediates innate immune detection of tracheal cytotoxin. EMBO Rep 6 (12):1201–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher SA, Dubuis ED, Belvisi MG (2011) G-protein coupled receptors regulating cough. Curr Opin Pharmacol 11 (3):248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangmool S, Kurose H (2011) G(i/o) protein-dependent and -independent actions of Pertussis Toxin (PTX). Toxins 3 (7):884–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Requero MA, Masin J, Konopasek I, Goni FM, Sebo P, Ostolaza H (2004) Membrane restructuring by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin, a member of the RTX toxin family. J Bacteriol 186 (12):3760–3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SA, Karnovsky ML, Krueger JM, Pappenheimer JR, Biemann K (1984) Peptidoglycans as promoters of slow-wave sleep. I. Structure of the sleep-promoting factor isolated from human urine. The Journal of biological chemistry 259 (20):12652–12658 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masin J, Osicka R, Bumba L, Sebo P (2015) Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin: a unique combination of a pore-forming moiety with a cell-invading adenylate cyclase enzyme. Pathog Dis 73 (8):ftv075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masin J, Osicka R, Bumba L, Sebo P (2018) Phospholipase A activity of adenylate cyclase toxin? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115 (11):E2489–E2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauck J, Chan L, Glaser L (1971) Turnover of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria. The Journal of biological chemistry 246 (6):1820–1827 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melly MA, McGee ZA, Rosenthal RS (1984) Ability of monomeric peptidoglycan fragments from Neisseria gonorrhoeae to damage human fallopian-tube mucosa. The Journal of infectious diseases 149 (3):378–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielcarek N, Debrie AS, Raze D, Bertout J, Rouanet C, Younes AB, Creusy C, Engle J, Goldman WE, Locht C (2006) Live attenuated B. pertussis as a single-dose nasal vaccine against whooping cough. PLoS pathogens 2 (7):e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielcarek N, Riveau G, Remoue F, Antoine R, Capron A, Locht C (1998) Homologous and heterologous protection after single intranasal administration of live attenuated recombinant Bordetella pertussis. Nature biotechnology 16 (5):454–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobberley-Schuman PS, Connelly B, Weiss AA (2003) Phagocytosis of Bordetella pertussis incubated with convalescent serum. J Infect Dis 187 (10):1646–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MK, McFall-Ngai M (1994) Bacterial symbionts induce host organ morphogenesis during early postembryonic development of the squid Euprymna scolopes. Development 120 (7):1719–1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse SI, Morse JH (1976) Isolation and properties of the leukocytosis- and lymphocytosis-promoting factor of Bordetella pertussis. J Exp Med 143 (6):1483–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz JJ, Arai H, Bergman RK, Sadowski PL (1981) Biological activities of crystalline pertussigen from Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun 33 (3):820–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz JJ, Bernard CC, Mackay IR (1984) Elicitation of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) in mice with the aid of pertussigen. Cell Immunol 83 (1):92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AW, Wagner EK, Laber JR, Goodfield LL, Smallridge WE, Harvill ET, Papin JF, Wolf RF, Padlan EA, Bristol A, Kaleko M, Maynard JA (2015) A cocktail of humanized anti-pertussis toxin antibodies limits disease in murine and baboon models of whooping cough. Science translational medicine 7 (316):316ra195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njamkepo E, Pinot F, Francois D, Guiso N, Polla BS, Bachelet M (2000) Adaptive responses of human monocytes infected by bordetella pertussis: the role of adenylate cyclase hemolysin. J Cell Physiol 183 (1):91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogimori K, Ito K, Tamura M, Satoh S, Ishii S, Ui M (1984) Chemical modification of islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin. Essential role of free amino groups in its lymphocytosis-promoting activity. Biochimica et biophysica acta 801 (2):220–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr B, Douce G, Baillie S, Parton R, Coote J (2007) Adjuvant effects of adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis after intranasal immunisation of mice. Vaccine 25 (1):64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osickova A, Masin J, Fayolle C, Krusek J, Basler M, Pospisilova E, Leclerc C, Osicka R, Sebo P (2010) Adenylate cyclase toxin translocates across target cell membrane without forming a pore. Mol Microbiol 75 (6):1550–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osickova A, Osicka R, Maier E, Benz R, Sebo P (1999) An amphipathic alpha-helix including glutamates 509 and 516 is crucial for membrane translocation of adenylate cyclase toxin and modulates formation and cation selectivity of its membrane channels. J Biol Chem 274 (53):37644–37650 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskouizadeh K, Selk-Ghafari M, Zahraei-Salehi T, and Dezfolian O (2011) Isolation of Bordetella bronchiseptica in a dog with tracheal collapse. Comparative Clinical Pathology 20 (5):153–158 [Google Scholar]

- Ostolaza H (2018) Reply to Masin et al. : To be or not to be a phospholipase A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115 (11):E2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostolaza H, Martin C, Gonzalez-Bullon D, Uribe KB, Etxaniz A (2017) Understanding the Mechanism of Translocation of Adenylate Cyclase Toxin across Biological Membranes. Toxins (Basel) 9 (10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock CD, Sanden GN, Cherry JD, Gal AA, Langston C, Tatti KM, Wu KH, Goldsmith CS, Greer PW, Montague JL, Eliason MT, Holman RC, Guarner J, Shieh WJ, Zaki SR (2008) Pathology and pathogenesis of fatal Bordetella pertussis infection in infants. Clin Infect Dis 47 (3):328–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik D, Monahan A, Caffrey DR, Elling R, Goldman WE, Silverman N (2017) SLC46 Family Transporters Facilitate Cytosolic Innate Immune Recognition of Monomeric Peptidoglycans. Journal of immunology 199 (1):263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande AH, Moe D, Jamnadas M, Tatulian SA, Teter K (2006) The pertussis toxin S1 subunit is a thermally unstable protein susceptible to degradation by the 20S proteasome. Biochemistry 45 (46):13734–13740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton R, Hall E, Wardlaw AC (1994) Responses to Bordetella pertussis mutant strains and to vaccination in the coughing rat model of pertussis. Journal of medical microbiology 40 (5):307–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RD, Symes P, Conboy M, Weiss AA, Hewlett EL (1987) Inhibition of monocyte oxidative responses by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. J Immunol 139 (8):2749–2754 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TH, Okada T, Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cyster JG (2008) S1P1 receptor signaling overrides retention mediated by G alpha i-coupled receptors to promote T cell egress. Immunity 28 (1):122–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce C, Klein N, Peters M (2000) Is leukocytosis a predictor of mortality in severe pertussis infection? Intensive Care Med 26 (10):1512–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaut RD, Carbonetti NH (2008) Retrograde transport of pertussis toxin in the mammalian cell. Cell Microbiol 10 (5):1130–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaut RD, Scanlon KM, Taylor M, Teter K, Carbonetti NH (2016) Intracellular disassembly and activity of pertussis toxin require interaction with ATP. Pathog Dis 74 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogel A, Meller R, Hanski E (1991) Adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. The relationship between induction of cAMP and hemolysis. J Biol Chem 266 (5):3154–3161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose T, Sebo P, Bellalou J, Ladant D (1995) Interaction of calcium with Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Characterization of multiple calcium-binding sites and calcium-induced conformational changes. J Biol Chem 270 (44):26370–26376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal RS, Nogami W, Cookson BT, Goldman WE, Folkening WJ (1987) Major fragment of soluble peptidoglycan released from growing Bordetella pertussis is tracheal cytotoxin. Infection and immunity 55 (9):2117–2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross PJ, Lavelle EC, Mills KH, Boyd AP (2004) Adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis synergizes with lipopolysaccharide to promote innate interleukin-10 production and enhances the induction of Th2 and regulatory T cells. Infect Immun 72 (3):1568–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross PJ, Sutton CE, Higgins S, Allen AC, Walsh K, Misiak A, Lavelle EC, McLoughlin RM, Mills KH (2013) Relative contribution of Th1 and Th17 cells in adaptive immunity to Bordetella pertussis: towards the rational design of an improved acellular pertussis vaccine. PLoS Pathog 9 (4):e1003264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands HE, Goldman AP, Harrington K, Karimova A, Brierley J, Cross N, Skellett S, Peters MJ (2010) Impact of rapid leukodepletion on the outcome of severe clinical pertussis in young infants. Pediatrics 126 (4):e816–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin K, Glazer S (2016) The potential role of subclinical Bordetella Pertussis colonization in the etiology of multiple sclerosis. Immunobiology 221 (4):512–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon KM, Gau Y, Zhu J, Skerry C, Wall SM, Soleimani M, Carbonetti NH (2014) Epithelial anion transporter pendrin contributes to inflammatory lung pathology in mouse models of Bordetella pertussis infection. Infect Immun 82 (10):4212–4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon KM, Snyder YG, Skerry C, Carbonetti NH (2017) Fatal Pertussis in the Neonatal Mouse Model Is Associated with Pertussis Toxin-Mediated Pathology beyond the Airways. Infect Immun 85 (11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel AR, Pauza CD (1999) Pertussis toxin treatment in vivo reduces surface expression of the adhesion integrin leukocyte function antigen-1 (LFA-1). Cell adhesion and communication 7 (3):183–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider OD, Weiss AA, Miller WE (2009) Pertussis toxin signals through the TCR to initiate cross-desensitization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Immunol 182 (9):5730–5739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebo P, Ladant D (1993) Repeat sequences in the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin can be recognized as alternative carboxy-proximal secretion signals by the Escherichia coli alpha-haemolysin translocator. Mol Microbiol 9 (5):999–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerry C, Goldman WE, Carbonetti NH (2019) Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein 4 Suppresses Early Inflammatory Responses to Bordetella pertussis and Contributes to Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor Agonist-Mediated Disease Attenuation. Infection and immunity 87 (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerry CM, Cassidy JP, English K, Feunou-Feunou P, Locht C, Mahon BP (2009) A live attenuated Bordetella pertussis candidate vaccine does not cause disseminating infection in gamma interferon receptor knockout mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol 16 (9):1344–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerry CM, Mahon BP (2011) A live, attenuated Bordetella pertussis vaccine provides long-term protection against virulent challenge in a murine model. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18 (2):187–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skopova K, Tomalova B, Kanchev I, Rossmann P, Svedova M, Adkins I, Bibova I, Tomala J, Masin J, Guiso N, Osicka R, Sedlacek R, Kovar M, Sebo P (2017) Cyclic AMP-Elevating Capacity of Adenylate Cyclase Toxin-Hemolysin Is Sufficient for Lung Infection but Not for Full Virulence of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun 85 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spensieri F, Fedele G, Fazio C, Nasso M, Stefanelli P, Mastrantonio P, Ausiello CM (2006) Bordetella pertussis inhibition of interleukin-12 (IL-12) p70 in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells blocks IL-12 p35 through adenylate cyclase toxin-dependent cyclic AMP induction. Infect Immun 74 (5):2831–2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surridge J, Segedin ER, Grant CC (2007) Pertussis requiring intensive care. Arch Dis Child 92 (11):970–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svedova M, Masin J, Fiser R, Cerny O, Tomala J, Freudenberg M, Tuckova L, Kovar M, Dadaglio G, Adkins I, Sebo P (2016) Pore-formation by adenylate cyclase toxoid activates dendritic cells to prime CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Immunol Cell Biol 94 (4):322–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Gray MC, Hewlett EL (1994) Adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis produces ion conductance across artificial lipid bilayers in a calcium- and polarity-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 269 (36):22496–22499 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierry-Carstensen B, Dalby T, Stevner MA, Robbins JB, Schneerson R, Trollfors B (2013) Experience with monocomponent acellular pertussis combination vaccines for infants, children, adolescents and adults--a review of safety, immunogenicity, efficacy and effectiveness studies and 15 years of field experience. Vaccine 31 (45):5178–5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorstensson R, Trollfors B, Al-Tawil N, Jahnmatz M, Bergstrom J, Ljungman M, Torner A, Wehlin L, Van Broekhoven A, Bosman F, Debrie AS, Mielcarek N, Locht C (2014) A phase I clinical study of a live attenuated Bordetella pertussis vaccine--BPZE1; a single centre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalating study of BPZE1 given intranasally to healthy adult male volunteers. PloS one 9 (1):e83449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T, Park JT (2008) Peptidoglycan Recycling. EcoSal Plus 3 (1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe KB, Etxebarria A, Martin C, Ostolaza H (2013) Calpain-Mediated Processing of Adenylate Cyclase Toxin Generates a Cytosolic Soluble Catalytically Active N-Terminal Domain. PLoS One 8 (6):e67648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez HA, Oviedo JM, Gorgojo JP, Lamberti Y, Rodriguez ME (2016) Bordetella pertussis modulates human macrophage defense gene expression. Pathog Dis 74 (6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vojtova J, Kamanova J, Sebo P (2006) Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin: a swift saboteur of host defense. Curr Opin Microbiol 9 (1):69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainford RD, Kurtz K, Kapusta DR (2008) Central G-alpha subunit protein-mediated control of cardiovascular function, urine output, and vasopressin secretion in conscious Sprague-Dawley rats. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 295 (2):R535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Gray MC, Hewlett EL, Maynard JA (2015) The Bordetella adenylate cyclase repeat-in-toxin (RTX) domain is immunodominant and elicits neutralizing antibodies. J Biol Chem 290 (6):3576–3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warfel JM, Beren J, Kelly VK, Lee G, Merkel TJ (2012) Nonhuman primate model of pertussis. Infect Immun 80 (4):1530–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warfel JM, Merkel TJ (2014) The baboon model of pertussis: effective use and lessons for pertussis vaccines. Expert review of vaccines 13 (10):1241–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnock RA, Askari S, Butcher EC, von Andrian UH (1998) Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte homing to peripheral lymph nodes. J Exp Med 187 (2):205–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingart CL, Mobberley-Schuman PS, Hewlett EL, Gray MC, Weiss AA (2000) Neutralizing antibodies to adenylate cyclase toxin promote phagocytosis of Bordetella pertussis by human neutrophils. Infect Immun 68 (12):7152–7155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingart CL, Weiss AA (2000) Bordetella pertussis virulence factors affect phagocytosis by human neutrophils. Infect Immun 68 (3):1735–1739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AA, Goodwin MS (1989) Lethal infection by Bordetella pertussis mutants in the infant mouse model. Infect Immun 57 (12):3757–3764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AA, Hewlett EL, Myers GA, Falkow S (1983) Tn5-induced mutations affecting virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun 42 (1):33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter K, Zipprich J, Harriman K, Murray EL, Gornbein J, Hammer SJ, Yeganeh N, Adachi K, Cherry JD (2015) Risk Factors Associated With Infant Deaths From Pertussis: A Case-Control Study. Clin Infect Dis 61 (7):1099–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witvliet MH, Burns DL, Brennan MJ, Poolman JT, Manclark CR (1989) Binding of pertussis toxin to eucaryotic cells and glycoproteins. Infect Immun 57 (11):3324–3330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J, Cook GH, Goldhammer AR, Berkowitz SA (1980) Calmodulin activates prokaryotic adenylate cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77 (7):3841–3844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WS, Rosoff PM (1996) Pharmacology of pertussis toxin B-oligomer. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 74 (5):559–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington ZE, Carbonetti NH (2007) Evading the proteasome: absence of lysine residues contributes to pertussis toxin activity by evasion of proteasome degradation. Infect Immun 75 (6):2946–2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yajima M, Hosoda K, Kanbayashi Y, Nakamura T, Nogimori K, Mizushima Y, Nakase Y, Ui M (1978) Islets-activating protein (IAP) in Bordetella pertussis that potentiates insulin secretory responses of rats. Purification and characterization. Journal of biochemistry 83 (1):295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaretzky FR, Gray MC, Hewlett EL (2002) Mechanism of association of adenylate cyclase toxin with the surface of Bordetella pertussis: a role for toxin-filamentous haemagglutinin interaction. Mol Microbiol 45 (6):1589–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao CB, Coons SW, Cui M, Shi FD, Vollmer TL, Ma CY, Kuniyoshi SM, Shi J (2008) A new EAE model of brain demyelination induced by intracerebroventricular pertussis toxin. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 370 (1):16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M, Zhu W, Han Q, Xiao RP (2005) Emerging concepts and therapeutic implications of beta-adrenergic receptor subtype signaling. Pharmacology & therapeutics 108 (3):257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zocchi MR, Contini P, Alfano M, Poggi A (2005) Pertussis toxin (PTX) B subunit and the nontoxic PTX mutant PT9K/129G inhibit Tat-induced TGF-beta production by NK cells and TGF-beta-mediated NK cell apoptosis. J Immunol 174 (10):6054–6061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]