Abstract

Not only does the innate immune system represent the first line of defense against invading pathogens, but it is also responsible for instructing appropriate adaptive immune responses. Pattern recognition receptors (PRR) detect the presence of invading pathogens and are paramount in innate instruction of the adaptive immune response. A diverse class of PRRs, the NOD-like Receptors (NLR), has recently been implicated in the regulation of processes ranging from anti-tumor immunity to the adjuvant action of aluminum hydroxide. In this review we will highlight many of the recent findings in the NLR field with a particular focus on NLR influence of adaptive immune responses.

Introduction

The vertebrate immune system consists of two arms: the innate and adaptive immune systems. The innate arm is the first to detect and respond to pathogens and rapidly clears a majority of these insults. The adaptive arm consists of T and B cells, which provide long-term immunological memory with exquisite antigen specificity through the T cell and B cell receptors, respectively. However, as these receptors can collectively recognize any antigen—whether non-self (pathogen-derived) or self, their activation must be tightly regulated by the innate branch of the immune system. Dendritic cells (DCs) lie at this innate-adaptive interface and continually survey tissues, take up antigens and, upon activation of innate receptors, license naïve T cells to begin an adaptive immune response. Thus, innate recognition of loss of homeostasis (i.e. presence of pathogens, altered self-molecules, or host damage) is central to generating effective adaptive immunity.

PRRs in innate immunity–division of labor

To enable rapid pathogen detection, the innate immune system utilizes numerous germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRR) that recognize conserved pathogen-derived motifs, termed pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), or host-derived markers of cell stress and/or damage, called damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). A large group of PRRs act as signaling receptors to induce production of innate effectormolecules upon pathogen detection. These signaling receptors can be divided into multiple classes including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), and NOD-like receptors (NLRs). TLRs are membrane bound (cell surface or endosomal) receptors that recognize a wide variety of extracellular or phagocytosed PAMPs [1]. By contrast, RLRs are cytoplasmic RNA helicases that act as sensors of viral RNA [2]. The third class of PRRs, the NLRs, is also cytosolic and responds to a diverse range of PAMPs and/or DAMPs [3]. Thus, NLRs represent a second line of defense against pathogens that evade cell surface or endocytic PRRs. Unlike TLRs, NLRs are also capable of initiating two unique inflammatory forms of programmed cell death, pyroptosis and pyronecrosis [4-6].

NLRs and the inflammasome

Most NLRs contain a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain that is thought to function in ligand sensing, a central NACHT nucleotide-binding domain that is important for oligomerization and activation, and an N-terminal effector domain that mediates signal transduction to downstream targets through protein-protein interactions. The N-terminal domain, partly, determines the outcome of NLR activation and by virtue of this domain NLRs can be classified into 4 major groups: (1) NLRA, containing an acidic transactivaton domain; (2) NLRB, containing a baculoviral inhibitory repeat (BIR)-like domain; (3) NLRC, containing a caspase recruitment domain (CARD); and (4) NLRP, containing a pyrin domain (PYD) (Table 1) [7].

Table 1.

Human and mouse NOD-like receptors with synonyms and known agonists. Note that particular NLRs, such as Nlrp1 have a number of paralogs (1a–1c) and are listed together. PGN, peptidoglycan; Gm+, Gram positive; Gm−, Gram negative; MDP, Muramyl Dipeptide; DAP, Diaminopimelic Acid.

| Family | Human ortholog | Mouse ortholog | Selected agonists |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLRA | CIITA (MHC2TA, C2TA) | CIIta (C2ta) | IFN-γ |

| NLRB | NAIP | Naip1-7 (Birc1a-g, Naip-rs1-4B) | Legionella and Flagellin (Naip5) |

| NLRC | NOD1 (NLRC1, CARD4, CLR7.1) | Nod1 (Nlrc1, Card4) | Meso-DAP (PGN from Gm−, Some Gm+, Mycobacterium) |

| NOD2 (NLRC2, CARD15, CD, BLAU, IBD1, PSORAS1, CLR16.3) | Nod2 (Nlrc2, Card15) | MDP (PGN from Gm+, Gm−, Mycobacterium) | |

| NLRC3 (NOD3, CLR16.2) | Nlrc3 (CLR16.2) | ||

| NLRC4 (IPAF, CARD12, CLAN, CLR2.1) | Nlrc4 (Ipaf, Card12, Clan) | Flagellin, Pseudomonas, Salmonella, Legionella, Shigella | |

| NLRC5 (NOD27, CLR16.1) | Nlrc5 | ||

| NLRP | NLRP1 (NALP1, DEFCAP, NAC, CARD7) | Nlrp1a-c (Nalp1a-c)* | MDP (NLRP1), Anthrax Lethal Toxin (Nlrp1b) |

| NLRP2 (NALP2, Pypaf2, NBS1, PAN1) | Nlrp2 (Nalp2) | ||

| NLRP3 (NALP3, (Cryopyrin, CIAS1, Pypaf1) | Nlrp3 (Nalp3, Cias1, Pypaf1, Mmig1, Cryopyrin) |

Pore-forming toxins–Nigericin, Aerolysin, Listeriolysin, Tetanolysin, α–β hemolysin, Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins Extracellular ATP, Necrotic Cells Sterile Inflammation–Hyaluronan, Biglycan Crystals/Particulates–Uric Acid, Alum, Silica, Asbestos, Amyloid-β, Nanoparticles Pathogen Products—Mycobacteria, Neisseria Lipooligosaccharide, Candida Hyphae, Influenza RNA, Adenoviral DNA, Klebsiella pneumonia, Malarial Hemozoin |

|

| NLRP4 (NALP4, Pypaf4, PAN2, RNH2) | Nlrp4a-g (Nalp4a-g) | ||

| NLRP5 (NALP5, Pypaf8, Mater, PAN11) | Nlrp5 (Nalp5, Mater, Op1)* | ||

| NLRP6 (NALP6, Pypaf5, PAN3) NLRP7 (NALP7, Pypaf3, NOD12) |

Nlrp6 (Nalp6) | ||

| NLRP8 (NALP8, PAN4, NOD16) NLRP9 (NALP9, NOD6) |

Nlrp9a-c (Nalp9a-c) | ||

| NLRP10 (NALP10, PAN5, NOD8, Pynod) | Nlrp10 (Nalp10, Pynod) | ||

| NLRP11 (NALP11, Pypaf6, NOD17) | |||

| NLRP12 (NALP12, Monarch-1, Pypaf7, PAN6, RNO2) | Nlrp12 (Nalp12) | ||

| NLRP13 (NALP13, NOD14) | |||

| NLRP14 (NALP14, NOD5) | Nlrp14 (Nalp14, GC-LRR) |

Lacks PYD domain in mouse orthologs.

Certain NLR members can form a multimolecular complex, termed the inflammasome [8]. To date three prototypic inflammasomes have been described: the NLRC4, NLRP1, and NLRP3 inflammasomes [3]. Inflammasomes are formed by homotypic domain interactions between the defining NLR, an adaptor molecule called ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein CARD domain) and caspase 1. Inflammasome activation initiates a number of cellular events depending upon the origin and strength of stimulus; however, the primary corollary of inflammasome assembly is the autocatalytic activation of caspase-1, which in turn induces the processing and secretion of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 [9]. Previous reports indicated that pro-IL-33 was similarly regulated by the casapse-1 inflammasome; however, recent studies show instead that full length IL-33 is active and is released during cell necrosis to alert the immune system to cell damage [10•,11•]. By contrast, apoptosis probably results in caspase-dependent cleavage of IL-33, silencing this effect. In addition to pro-inflammatory cytokine processing there is a growing list of leaderless proteins that are cleaved and/or secreted following caspase-1 activation [12•,13•]. However, the physiological significance of their cleavage has yet to be studied in detail and release of many of these candidates might result from bystander processing.

A number of specific NLR activators have been defined, such as flagellin in the case of the NLRC4 inflammasome, and anthrax lethal toxin in the case of the NLRP1b inflammasome [14-18]. By stark contrast, the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by a wide range of chemically and physically diverse stimuli, such as bacterial pore-forming toxins (e.g. Listeria’s LLO), insoluble crystals (e.g. uric acid), and extracellular ATP (Table 1) [19-22]. It is therefore unlikely that each trigger is sensed through direct recognition but rather through induction of common intracellular perturbations. Candidates include efflux of intracellular potassium, release of lysosomal contents and the generation of reactive oxygen species—each is crucial to NLRP3 activation depending on the system [23,24•,25]. However, the mechanisms by which these ‘signals’ induce inflammasome assembly have yet to be elucidated.

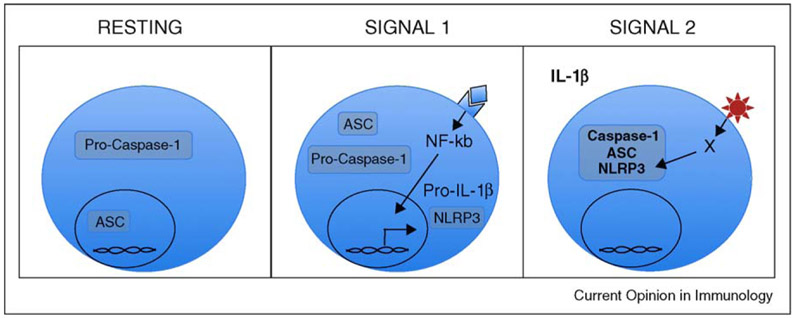

It has long been known that the NLRP3 inflammasome required a pre-activation ‘signal 1’ for both induction of substrates (e.g. pro-IL-1β) and for a ‘license’ to activate. Recently, Bauernfeind et al. clearly delineated that any number of NF-κB activating stimuli, from PAMPs to cytokines, can act as an inflammasome priming signal [26••]. In agreement, Franchi et al. confirmed that TNF-α and other non-microbial stimuli, including IL-1β itself, could act as signal 1 [27•]. Further, recent observations reveal how these stimuli may regulate inflammasome licensing; signal 1 results in increased Nlrp3 transcription—a step necessary to provide sufficient NLRP3 to nucleate the inflammasome upon signal 2 stimulation (Figure 1). This elegant model emphasizes the necessity of tight regulation of PRRs that have the ability to sense self-molecules such as uric acid; these layers of checkpoints would therefore limit aberrant NLRP3 activation and potentially prevent inappropriate activation of the adaptive immune arm, as we will next discuss.

Figure 1.

Stages of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Under resting conditions, NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β are not highly expressed. By contrast, ASC and caspase-1 are constitutively expressed, although with different subcellular localization. Upon stimulation by a variety of stimuli, such as LPS and other PAMPs as well as IL-1β and other cytokines that trigger NF-κB activation (Signal 1), NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β are transcribed but not activated; this has been termed ‘licensing of the inflammasome’. Only after a specific NLRP3 trigger such as crystals, extracellular ATP or pore-forming toxins (Signal 2), is the inflammasome formed and activated, resulting in cleavage of numerous secreted proteins, including IL-1β. It should be noted that while numerous triggers of NLRP3 have been identified, the actual ligand that binds to NLRP3 (X in panel 3) has not been identified.

Inflammasome-adaptive immunity crosstalk

In line with the model of innate instructed adaptive immune responses, many of the NLRs have been shown to induce the requisite signals for T and B cell activation. Of all NLRs, NODs have been most clearly and uniformly implicated in this innate-adaptive crossroad. NOD2 has been shown to mediate the adjuvant effect of muramyl dipeptide (MDP) [28] and lymphocyte responses to antigen priming with Complete Freund’s Adjuvant were severely diminished in NOD1-deficient mice [29]. In contrast to the NODs, a majority of the other NLR members simply have not been studied except for NLRP3, and the role of NLRP3 in adaptive immune processes is controversial. Multiple models or even the same model from different laboratories have generated a confusing picture of if, when and how NLRP3 might be involved in adaptive immune responses. Studies in 2008 using chemical sensitizers in contact hypersensitivity models were the first to demonstrate that lymphocyte sensitization was attenuated in inflammasome-deficient mice [22,30]. Since then, adjuvants such as aluminum hydroxide (‘alum’), infections such as influenza and products of cell necrosis have all been shown to activate NLRP3 and, depending on the study, initiate adaptive immunity through this innate pathway.

Products of cell death were one of the first identified triggers of NLRP3, including extracellular ATP and uric acid (for review see [3]). Expanding this list, four papers recently showed various products of cell death or tissue damage, from mitochondrial ATP to soluble biglycan, activate the NLRP3 inflammasome [31-34]. In one study, tumor cells treated with chemotherapeutic agents were used as effective adjuvants to prime anti-tumor Th1 and CD8+ T cell responses [35••]. Using multiple in vivo models, these authors showed that ATP released by the dying tumor, signaling through P2×7R, activated the NLRP3 inflammasome in DCs and the resultant IL-1β was sufficient to drive an effective adaptive response. These studies support the hypothesis that NLRP3 activation is capable of providing the requisite signals to instruct long-lived adaptive immune responses and therefore might be a useful target in vaccination.

Indeed uric acid had long been known to act as an effective T cell adjuvant [36]. On the basis of the similarity in physical properties between uric acid and the commonly used vaccine adjuvant alum (both suspensions of insoluble crystals), multiple groups tested whether NLRP3 was the long-sought innate pathway through which this mysterious adjuvant worked. Seven recent reports have described activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by various forms of aluminum adjuvants [24•,37•,38•,39•,40•,41•,42•]. In all studies, alum adjuvants activated monocytes in vitro leading to caspase-1 activation and IL-1β secretion in an NLRP3-dependent manner. Yet, these studies found widely divergent roles for NLRP3 in vivo. Alum was shown by our group and by two others to induce DC and lymphocyte activation in a NLRP3-dependent manner [37•,39•,40•]; by contrast, two other groups did not find a difference in T cell or antibody responses in NLRP3-deficient mice [38•,41•]. One group has further shown that uric acid is released and is required for the adjuvant function of alum [43••]. Whether uric acid is then acting through NLRP3 is not yet known.

Because alum is such a potent Th2 adjuvant in mice, T cell activation and T cell differentiation are often considered indistinguishable. Yet in the absence of the major Th2 cytokines (such as IL-4 or STAT6 signaling), alum still primes a T cell response, but the response is more Th1 biased, indicating priming and Th2 differentiation can be dissociated (for review see [44]). Where does the NLR pathway fit in this paradigm? From our own data and those of other groups, it seems clear that NLRP3 does not control Th2 differentiation (S.C.E. and R.A.F. unpublished observations and [41•]); therefore NLRP3 is probably acting to initiate priming. Without effective T cell priming, differentiation cannot occur—a model that is consistent with some of the published studies [37•,40•] and with the DC phenotype observed in one study [39•]. But if priming is intact (e.g. by bypassing the innate stimulus provided by NLRP3), differentiation should be intact—a model that is consistent with a number of other studies and with data showing influx of eosinophils and early Th2 cytokine production at the site of alum injection [38•,41•]. However, even this speculative model does not fit all of the data. In certain alum immunization models, IgE (a Th2-associated antibody) was completely absent in NLRP3-deficient mice while IgG2c (a Th1- type antibody) was increased suggesting priming is intact but Th2 skewing is instead defective [39•]. While no united model can yet be generated to explain the adjuvant function of alum, multiple variables might explain these contrasting results, including different NLRP3-deficient strains, different genetic backgrounds of the mice, different alum preparations, and different immunization protocols. What is clear though is that a better understanding of how NLRP3 agonists influence regulation of the adaptive immune response will be crucial and perhaps will enable the generation of more targeted vaccine adjuvants.

Two groups, including our own, recently demonstrated that another particulate adjuvant, biodegradable polymer nanoparticles, can similarly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome [42•,45]. Interestingly, this novel vaccine delivery system was taken up by CD11b+Gr1- cells at the site of injection and upregulated the co-stimulatory molecule CD86 in a partially NLRP3-dependent manner [42•].

Surprisingly, it appears that these particles induce a normal antibody response in NLRP3-deficient mice in the face of a defective T cell response (S.C.E. and R.A.F. unpublished observations [42•]). Similarly, in an antigen-induced arthritis model, joint inflammation was significantly reduced in ASC-deficient mice but was unaffected in NLRP3-, NLRC4-, or caspase-1-deficient mice; intriguingly this study found that T cells lacking ASC had a reduced capacity to proliferate and to produce cytokines, suggesting a T cell intrinsic defect in ASC knockout mice that was inflammasome independent [46]. We do not yet know how inflammasome activation in different cell types differentially affects the overall immune response. This may be one other reason why innate responses in inflammasome-deficient mice have been relatively straightforward to study, while adaptive responses have presented significant challenges.

In addition to products of cell death and adjuvants, the NLRP3 inflammasome has also recently been implicated in the initiation of adaptive responses to infectious disease. Three groups studied the immune response to influenza virus in inflammasome-deficient mice and all agreed that NLRP3 plays an important role in the innate response to influenza [47-49]. But again there was disagreement about the impact of NLRP3 deficiency on the adaptive response. Two groups found that survival and cellular response in the lungs required intact NLRP3 [47,49], while another found that only caspase-1 and ASC but not NLRP3 were crucial for survival and induction of an effective T and B cell response [48]. Possible differences in influenza preparations could explain some of these disparities, but again the discrepant findings in NLRP3-deficient mice are difficult to resolve.

Much of this confusion is probably generated by the use of different in vivo models. In particular, although the regulation of inflammasome activation in vitro is well characterized with a requirement for two signals (Figure 1), it is still not clear where and how signal 1 is generated in vivo. It is plausible that in some models, signal 1 is generated and in others it is not; without signal 1 it would be impossible to get inflammasome activation and therefore see an inflammasome-dependent effect. Until we understand this aspect of inflammasome biology it will be difficult to interpret and compare these different models; however, given such variability it seems likely that complex immune triggers such as alum or influenza activate multiple innate pathways that can each regulate adaptive responses circumventing absolute requirements for any one pathway.

Autoinflammatory versus autoimmune diseases

Mutations in NLRP1 have been associated with the autoimmune disease vitiligo [50] and SNPs in NLRP3, thought to increase NLRP3 message levels, were significantly associated with food-induced anaphylaxis and aspirin-induced asthma [51]. Both studies suggest that an exaggerated inflammasome response might predispose to dysregulated adaptive immunity in humans; however, a group of rare disorders called Autoinflammatory Disorders (AID) provides evidence that constitutive inflammasome activation does not result in dysregulated adaptive immunity. AID include a number of different syndromes that manifest with recurrent episodes of inflammation in multiple organs including the joints, skin, and central nervous system, without evidence of infection, autoantibodies, or autoreactive T cells (see [3,9] for review). One rare subgroup of AID is the cryopyrinopathies (or CAPS) caused by dominantly inherited gain-of-function NLRP3 mutations, resulting in dysregulated production of IL-1β. While IL-1β has been implicated in the pathogenesis of a number of autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, it is important to emphasize that autoinflammatory is not synonymous with autoimmune disease; CAPS patients do not have evidence of altered adaptive immune responses despite recurrent inflammasome activation, although as we will next discuss, even this distinction is blurred in animal models of AID.

Two recent papers, which both studied constitutive active forms of NLRP3, provide conflicting views of the influence of NLRP3 on adaptive immunity [52•,53•]. These groups introduced the relevant point mutations in NLRP3 to mimic various CAPS, rendering NLRP3 activation independent of signal 2. Both groups saw evidence of skin and systemic illness and identified a central role for IL-1β and cells of the myeloid lineage in the disease process, thus mirroring the human disorders. Hoffman’s group then crossed these mice with RAG1 knockouts, thereby eliminating T and B cells, without significantly altering the observed phenotype, suggesting that the autoinflammatory disease process was dependent on a dysregulated innate but not adaptive immune response. By contrast, Strober’s group found that in addition to dermatitis, these mice had increased antidouble stranded DNA autoantibodies and activated T cells with a proclivity toward Th17 differentiation. These are characteristics of an autoimmune rather than autoinflammatory disease and are consistent with NLRP3 regulation of adaptive immunity. While the two groups generated mice with different point mutations in NLRP3 one cannot rule out differences in mouse colony environment, especially given the known effect of gut commensal flora on Th17 regulation [54]. But again, it is not clear why different models of NLRP3-induced inflammasome should result in such divergent adaptive immune responses.

Conclusions

Understanding the crossroad between the two major arms of the immune system is crucial, as it has already and will continue to clarify the physiology underpinning a myriad of useful (e.g. vaccination, anti-tumor) and harmful (e.g. allergic, autoimmune) adaptive immune responses. As activation of NLRs, and NLRP3 in particular, is triggered by a wide range of stimuli, it is not surprising that these molecules have now been implicated in this crossroad. In this review, we have highlighted many of the recent advances in the NLR field, but along with these advances, numerous unanswered questions regarding the in vivo function and relevance of these NLR pathways remain. Crucially: (1) what initiates the first signal for inflammasome priming in vivo? (2) Which cells respond to NLRP3 inflammasome triggers in vivo? (3) What is the role of other putative caspase-1 substrates (i.e. beyond IL-1β and IL-18) in the physiology of inflammasome function? (4) What products of NLRP3 inflammasome activation regulate T cell priming and polarization? (5) What is the ligand or ligands that directly activate NLRP3? Answers to these questions will help clarify the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome and potentially other inflammasomes in adaptive immune responses. In addition, beyond the NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasomes and NOD1 and NOD2, we still have only a rudimentary knowledge concerning the function of a majority of NLR family members. Thus, our understanding of the repertoire of innate receptors that regulate the adaptive immune system is still only in its infancy and suggests there is incredible potential to advance our understanding of immune regulation and function.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S: Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009, 388:621–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pichlmair A, Reis e Sousa C: Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity 2007, 27:370–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J: The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol 2009, 27:229–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Yu JW, Datta P, Miller B, Jankowski W, Rosenberg S, Zhang J, Alnemri ES: The pyroptosome: a supramolecular assembly of ASC dimers mediating inflammatory cell death via caspase-1 activation. Cell Death Differ 2007, 14:1590–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fink SL, Cookson BT: Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell Microbiol 2006, 8:1812–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willingham SB, Bergstralh DT, O’Connor W, Morrison AC, Taxman DJ, Duncan JA, Barnoy S, Venkatesan MM, Flavell RA, Deshmukh M et al. : Microbial pathogen-induced necrotic cell death mediated by the inflammasome components CIAS1/cryopyrin/NLRP3 and ASC. Cell Host Microbe 2007, 2:147–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ting JP, Lovering RC, Alnemri ES, Bertin J, Boss JM, Davis BK, Flavell RA, Girardin SE, Godzik A, Harton JA et al. : The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity 2008, 28:285–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J: The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell 2002, 10:417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arend WP, Palmer G, Gabay C: IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 families of cytokines. Immunol Rev 2008, 223:20–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.•.Cayrol C, Girard JP: The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is inactivated after maturation by caspase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106:9021–9026.This study argues that pro-IL-33 is active and that cleavage by casapse-1 results in loss of function.

- 11.•.Luthi AU, Cullen SP, McNeela EA, Duriez PJ, Afonina IS, Sheridan C, Brumatti G, Taylor RC, Kersse K, Vandenabeele P et al. : Suppression of interleukin-33 bioactivity through proteolysis by apoptotic caspases. Immunity 2009, 31:84–98This study also argues that pro-IL-33 is active, but that cleavage by noncaspase-1 caspases results in loss of function.

- 12.•.Keller M, Ruegg A, Werner S, Beer HD: Active caspase-1 is a regulator of unconventional protein secretion. Cell 2008, 132:818–831.Using mass spectrometry-based iTRAQ, this study identifies numerous secreted but leaderless products from keratinocytes that require casapse-1.

- 13.•.Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD, Van Damme P, Vanden Berghe T, Vanoverberghe I, Vandekerckhove J, Vandenabeele P, Gevaert K, Nunez G: Targeted peptidecentric proteomics reveals caspase-7 as a substrate of the caspase-1 inflammasomes. Mol Cell Proteomics 2008, 7:2350–2363.Using LC-MS/MS, this proteomics screen identified cleavage products of caspase-1 in macrophage cell lysates, with a particular focus on caspase-7.

- 14.Amer A, Franchi L, Kanneganti TD, Body-Malapel M, Ozoren N, Brady G, Meshinchi S, Jagirdar R, Gewirtz A, Akira S et al. : Regulation of Legionella phagosome maturation and infection through flagellin and host Ipaf. J Biol Chem 2006, 281:35217–35223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyden ED, Dietrich WF: Nalp1b controls mouse macrophage susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin. Nat Genet 2006, 38:240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franchi L, Stoolman J, Kanneganti TD, Verma A, Ramphal R, Nunez G: Critical role for Ipaf in Pseudomonas aeruginosainduced caspase-1 activation. Eur J Immunol 2007, 37:3030–3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miao EA, Alpuche-Aranda CM, Dors M, Clark AE, Bader MW, Miller SI, Aderem A: Cytoplasmic flagellin activates caspase-1 and secretion of interleukin 1beta via Ipaf. Nat Immunol 2006, 7:569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nour AM, Yeung YG, Santambrogio L, Boyden ED, Stanley ER, Brojatsch J: Anthrax lethal toxin triggers the formation of a membrane-associated inflammasome complex in murine macrophages. Infect Immun 2009, 77:1262–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanneganti TD, Ozoren N, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Franchi L, Whitfield J, Barchet W, Colonna M, Vandenabeele P et al. : Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase-1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature 2006, 440:233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O’Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, Lee WP, Weinrauch Y, Monack DM, Dixit VM: Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature 2006, 440:228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J: Goutassociated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 2006, 440:237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Szczepanik M, Lara-Tejero M, Lichtenberger GS, Grant EP, Bertin J, Coyle AJ, Galan JE, Askenase PW et al. : Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity 2006, 24:317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J: Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science 2008, 320:674–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.•.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E: Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol 2008, 9:847–856.One of seven papers describing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by alum. While this study did not evaluate the in vivo effect of NLRP3-deficiency upon alum immunization, it did look at one potential mechanism of NLRP3 activation resulting from lysosomal disruption following alum phagocytosis.

- 25.Petrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J: Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ 2007, 14:1583–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.••.Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Monks BG, Fitzgerald KA et al. : Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol 2009, 183:787–791.An important study clarifying the role of ‘signal 1’ in licensing of the inflammasome by multiple NF-κB activators.

- 27.•.Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Nunez G: Cutting edge: TNF-alpha mediates sensitization to ATP and silica via the NLRP3 inflammasome in the absence of microbial stimulation. J Immunol 2009, 183:792–796.This paper also maintains that ‘signal 1’ can come from numerous stimuli including cytokines and IL-1beta.

- 28.Kobayashi KS, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y, Henegariu O, Inohara N, Nunez G, Flavell RA: Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science 2005, 307:731–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fritz JH, Le Bourhis L, Sellge G, Magalhaes JG, Fsihi H, Kufer TA, Collins C, Viala J, Ferrero RL, Girardin Se et al. : Nod1-mediated innate immune recognition of peptidoglycan contributes to the onset of adaptive immunity. Immunity 2007. 26:445–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe H, Gehrke S, Contassot E, Roques S, Tschopp J, Friedmann PS, French LE, Gaide O: Danger signaling through the inflammasome acts as a master switch between tolerance and sensitization. J Immunol 2008, 180:5826–5832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babelova A, Moreth K, Tsalastra-Greul W, Zeng-Brouwers J, Eickelberg O, Young MF, Bruckner P, Pfeilschifter J, Schaefer RM, Grone HJ et al. : Biglycan, a danger signal that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via toll-like and P2X receptors. J Biol Chem 2009, 284:24035–24048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iyer S, Pulskensc W, Sadler J, Butter L, Teske G, Ulland T, Eisenbarth S, Florquin S, Flavell R, Leemans J et al. : Necrotic cells trigger a sterile inflammatory response through the Nlrp3 inflammasome. PNAS 2009, 106:20388–20393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H, Ambade A, Re F: Cutting edge: necrosis activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Immunol 2009, 183:1528–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamasaki K, Muto J, Taylor KR, Cogen AL, Audish D, Bertin J, Grant EP, Coyle AJ, Misaghi A, Hoffman HM et al. : NLRP3/ cryopyrin is necessary for interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) release in response to hyaluronan, an endogenous trigger of inflammation in response to injury. J Biol Chem 2009, 284:12762–12771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.••.Ghiringhelli F, Apetoh L, Tesniere A, Aymeric L, Ma Y, Ortiz C, Vermaelen K, Panaretakis T, Mignot G, Ullrich E et al. : Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1beta-dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat Med 2009, 15:1170–1178.A thorough study of the adjuvant effect of chemotherapeutic-treated tumor cells. This paper argues that ATP released by dying cells, acting through P2×7R and HmGB1, activates the NLRP3 inflammasome thereby initiating adaptive anti-tumor immunity.

- 36.Shi Y, Evans JE, Rock KL: Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature 2003, 425:516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.•.Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O’Connor W, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA: Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature 2008. 453:1122–1126.One of seven papers describing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by alum. Our study found a reduced T and B cell response in vivo in an OVA/alum asthma model.

- 38.•.Franchi L, Nunez G: The Nlrp3 inflammasome is critical for aluminium hydroxide-mediated IL-1beta secretion but dispensable for adjuvant activity. Eur J Immunol 2008, 38:2085–2089.One of seven papers describing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by alum. This study failed to see a difference in antibody responses to antigens injected with alum in vivo in NLRP3-deficient mice.

- 39.•.Kool M, Petrilli V, De Smedt T, Rolaz A, Hammad H, van Nimwegen M, Bergen IM, Castillo R, Lambrecht BN, Tschopp J: Cutting edge: alum adjuvant stimulates inflammatory dendritic cells through activation of the NALP3 inflammasome. J Immunol 2008, 181:3755–3759.One of seven papers describing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by alum. This study found reduced DC activation in NLRP3-deficient mice immunized with antigen in alum and did find reduced antigen-specific IgE but also found increased IgG2c.

- 40.•.Li H, Willingham SB, Ting JP, Re F: Cutting edge: inflammasome activation by alum and alum’s adjuvant effect are mediated by NLRP3. J Immunol 2008, 181:17–21.One of seven papers describing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by alum. Using a tetanus toxoid-alum in vivo model, this group found reduced antigen-specific antibody production in NLRP3-deficient mice and also found that the adjuvants Quil A and chitosan also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.

- 41.•.McKee AS, Munks MW, MacLeod MK, Fleenor CJ, Van Rooijen N, Kappler JW, Marrack P: Alum induces innate immune responses through macrophage and mast cell sensors, but these sensors are not required for alum to act as an adjuvant for specific immunity. J Immunol 2009, 183:4403–4414.One of seven papers describing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by alum. However, this group found no role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in the adaptive immune response in vivo to antigen in alum.

- 42.•.Sharp FA, Ruane D, Claass B, Creagh E, Harris J, Malyala P, Singh M, O’Hagan Dt, Petrilli V, Tschopp J et al. : Uptake of particulate vaccine adjuvants by dendritic cells activates the NALP3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106:870–875.One of seven papers describing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by alum. While this paper mostly focused on the actions of microparticles in vivo, the authors did find in vitro NLRP3 activation by alum particles.

- 43.••.Kool M, Soullie T, van Nimwegen M, Willart MA, Muskens F, Jung S, Hoogsteden HC, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN: Alum adjuvant boosts adaptive immunity by inducing uric acid and activating inflammatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2008, 205:869–882.A thorough study of DC activation following alum immunization in mice. This paper concludes that uric acid and the MyD88 pathway are crucial to the immunogenicity of alum and that the mediastinal LN rather than the spleen is the site of adaptive activation following i.p. immunization.

- 44.Marrack P, McKee AS, Munks MW: Towards an understanding of the adjuvant action of aluminium. Nat Rev Immunol 2009, 9:287–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Demento SL, Eisenbarth SC, Foellmer HG, Platt C, Caplan MJ, Mark Saltzman W, Mellman I, Ledizet M, Fikrig E, Flavell RA et al. : Inflammasome-activating nanoparticles as modular systems for optimizing vaccine efficacy. Vaccine 2009, 27:3013–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kolly L, Karababa M, Joosten LA, Narayan S, Salvi R, Petrilli V, Tschopp J, van den Berg WB, So AK, Busso N: Inflammatory role of ASC in antigen-induced arthritis is independent of caspase-1, NALP-3, and IPAF. J Immunol 2009, 183:4003–4012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, Holl EK, McElvania-TeKippe E, Taxman DJ, Guthrie EH, Pickles RJ, Ting JP: The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity 2009, 30:556–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ichinohe T, Lee HK, Ogura Y, Flavell R, Iwasaki A: Inflammasome recognition of influenza virus is essential for adaptive immune responses. J Exp Med 2009, 206:79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas PG, Dash P, Aldridge JR Jr, Ellebedy AH, Reynolds C, Funk AJ, Martin WJ, Lamkanfi M, Webby RJ, Boyd KL et al. : The intracellular sensor NLRP3 mediates key innate and healing responses to influenza A virus via the regulation of caspase-1. Immunity 2009, 30:566–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin Y, Mailloux CM, Gowan K, Riccardi SL, LaBerge G, Bennett DC, Fain PR, Spritz RA: NALP1 in vitiligo-associated multiple autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med 2007, 356:1216–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hitomi Y, Ebisawa M, Tomikawa M, Imai T, Komata T, Hirota T, Harada M, Sakashita M, Suzuki Y, Shimojo N et al. : Associations of functional NLRP3 polymorphisms with susceptibility to food-induced anaphylaxis and aspirin-induced asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009, 124:779–785 e776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.•.Brydges SD, Mueller JL, McGeough MD, Pena CA, Misaghi A, Gandhi C, Putnam CD, Boyle DL, Firestein GS, Horner AA et al. : Inflammasome-mediated disease animal models reveal roles for innate but not adaptive immunity. Immunity 2009, 30:875–887.An elegant paper describing the characterization of a constitutively activate NLRP3 mutation to mimic a mouse model of CAPS. This study found no significant role for the adaptive immune system in the autoinflammatory disease process.

- 53.•.Meng G, Zhang F, Fuss I, Kitani A, Strober W: A mutation in the Nlrp3 gene causing inflammasome hyperactivation potentiates Th17 cell-dominant immune responses. Immunity 2009, 30:860–874.An intriguing study also describing the characterization of a constitutively activate NLRP3 mutation to mimic a mouse model of CAPS. This study found increased Th17 cell populations, increased activation state of T cells and autoantibodies in the autoinflammatory model.

- 54.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV et al. : Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]