Abstract

Background & objectives:

There has been an ongoing debate about the impact of Ramadan fasting (RF) on the health of these individuals who fast during Ramadan. The aim of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the relationship between RF and glycaemic parameters in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients.

Methods:

Search terms were decided and databases such as MEDLINE EBSCO, Google Scholar and EMBASE were searched for eligible studies. Standardized mean differences and 95 per cent confidence intervals (CIs) of post-prandial plasma glucose (PPG), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (%) and fructosamine levels were calculated for different treatment regimens.

Results:

Of the 40 studies, 19 were found eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Based on pooled results, significant reductions in FPG were found in single oral antidiabetics (OAD) [standardized weighted mean difference (SMD)=0.47, 95% CI=(0.20-0.74)], multi-OAD [SMD=0.36, 95% CI=(0.11-0.61)] and multitreatment subgroups [SMD=0.65, 95% CI=(0.03-1.27)] and overall [SMD=0.48, 95% CI=(0.27-0.70)]. Furthermore, HbA1c (%) [SMD=0.26, 95% CI=(0.03-0.49)] and body mass index (BMI) [SMD=0.18, 95% CI=(0.04-0.31)] were significantly decreased in the multi-OAD group.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The meta-analysis showed that RF was not associated with any significant negative effects on PPG and fructosamine levels. However, BMI and FPG and HbA1c (%) were positively affected by RF.

Keywords: Fasting plasma glucose, glycated haemoglobin (%), post-prandial plasma glucose, Ramadan fasting, T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common type of DM and affects around 95 per cent of people with DM around the world1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that in 2015, more than 415 million people worldwide were living with diabetes3, and in 2014, the International Diabetes Federation estimated that diabetes resulted in five million deaths4.

It is estimated that around 40 to 50 million individuals with diabetes worldwide fast during Ramadan5. During fasting, they abstain from eating, drinking, taking oral medications and smoking from sunrise to sunset. Because people fast from dawn to sunset, they consume substantial quantities of sugary foods and carbohydrate-rich meals during non-fasting hours5. It is assumed that these traditionally rich foods associated with Ramadan may present a risk of hyperglycaemia and weight gain for diabetic patients5. In healthy people, this fasting does not have any harmful consequences on health6. However, it can induce several complications in patients with diabetes7,8. There is only one previously published meta-analysis that showed the impact of fasting on health parameters in a healthy population6. An outcome of interest of other three meta-analysis was the occurrence of hypoglycaemic events in T2DM patients who fast during Ramadan9,10,11. There is perhaps no meta-analysis that included before-after studies to show any effect of RF on glycaemic parameters used for monitoring T2DM patients. For this reason, this meta-analysis was conducted including all recent studies on T2DM with the aim to demonstrate the impact of RF on the most widely reported health outcomes including post-prandial plasma glucose (PPG), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (%), fructosamine levels and body mass index (BMI).

Material & Methods

Literature search: A systematic review protocol was developed for the meta-analysis, and MEDLINE EBSCO, Google Scholar and EMBASE databases were searched from January 2010 to August 2017. Terms such as Ramadan, Ramadan fasting, diabetes, BMI, body weight, fructosamine, PPG, FPG, etc., were used to search appropriate studies in literature.

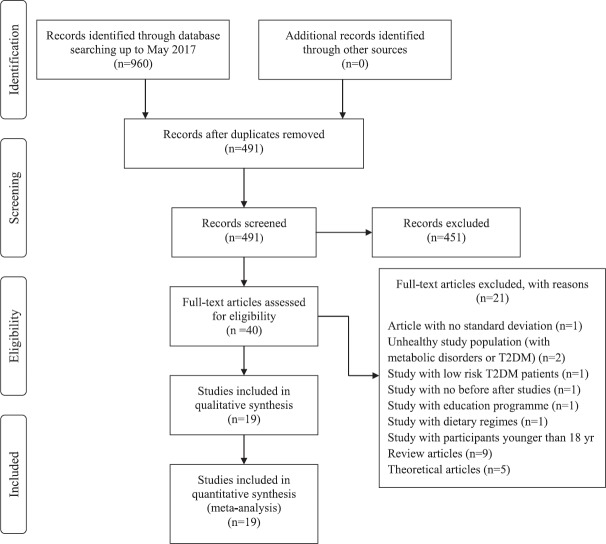

Study inclusion/exclusion criteria: All studies included in the meta-analysis compared the outcomes before and after RF. Studies were included when at least one of the following outcome indicators had been evaluated: PPG, FPG, HbA1c (%), fructosamine levels and BMI. Details are shown in Figure 1. Studies on patients with T2DM with co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease were excluded. Only studies with adult participants were considered.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search results.

Outcome measures: In this study, results were combined for five outcome indicators: PPG, FPG, HbA1c (%), fructosamine levels and BMI. Among the included studies, these were the most commonly used outcomes for which results were available.

Data extraction and quality assessment: Authors, publication year, sample size, characteristics of the population studied and outcome measures were recorded. Two authors independently screened the titles, abstracts and keywords to identify eligibility and assessed methodological quality of the included studies and recorded the findings and the studies were included when both agreed. Any disagreement was discussed with a third author. Quality of the paper was assessed based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale12. All of included studies achieved a score of 7 out of 8 on that scale. All of the outcome variables were continuous, and means and standard deviations were used as descriptive statistics.

Treatment subgroups: All patients with T2DM participating in the studies included in the meta-analysis were given different therapies. To evaluate the effect of different treatment regimens, studies were classified into three different subgroups: single oral antidiabetics (single OAD), multi-OAD and multitreatment (OAD plus insulin or diet modification).

Data analysis: Data analysis was performed using the guideline for statistical methods as described by the Cochrane Collaboration13. Random effect models were used to conduct meta-analysis of continuous outcomes to eliminate the effect of heterogeneity on results for all outcomes14. A sensitivity analysis was performed to identify studies with poor quality15. The earliest, the largest, the smallest and studies with the most contradictory results were excluded sequentially to see how these affected the meta-analysis when included in the sensitivity analysis. Separate funnel plots to assess potential publication bias for individual outcome variables were plotted. Egger regression test13 to check funnel plot asymmetry was applied using metaphor package in R package v3.5.1 for windows (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.5.1/). Meta-analysis results were presented with a forest plot. Since the units for the variables differed between the publications, these were converted into the most commonly used units to be able to combine results. The standardized weighted mean difference (SMD) and 95 per cent confidence intervals (CI) were used as a summary statistic in the meta-analysis to assess the same outcome. SMD can be considered as a uniform scale between 0 and 1 to express intervention effect14,15. A SMD less than 0.40 is interpreted as a small effect size, a SMD between 0.40 and 0.70 as moderate and >0.70 as a large effect size16. Analysis was performed using RevMan 5.0317.

Results

The search strategy identified a total of 960 records (Fig. 1). Among the 40 studies identified, 19 publications with 33 independent treatment groups met the study inclusion criteria. Details of all included studies and treatments are given in Table I. A total sample of 2457 patients was included in the meta-analysis. Five of the included studies were performed in Turkey18,19,20,21,22, and three were multicentered23,24,25. In studies by Almutari26 and Belkadir24 younger population was included compared to the rest of the studies. Not all of the study gave gender information, but majority of the studies included both men and women in the study. Duration of fasting varied between 10 and 30 days. Time of measurements for before and after Ramadan was different for each study.

Table I.

Summary of the study characteristics included in the meta-analysis

| First author, year | Country | Age range or mean age±SD (yr) | Male/female | Main outcome | Duration of fasting (days) | Time of measurements | Subgroups | Treatments | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Befxsore Ramadan | After Ramadan | |||||||||

| Yeoh et al, 201733 | Singapore | 57±11 | 15/14 | HbA1c (%), body weight change, blood pressure, TG | >15 | Before | Last day | No subgroups | Oral antidiabetic agents alone or insulin therapy + oral antidiabetics | 29 |

| Malha et al, 201430 | USA | 57.0±9.6 | - | HbA1c (%), hypoglycaemic events, BMI | >15 | Before | Last day | A | Metformin + vildagliptin | 30 |

| 54.6±9.2 | - | B | Metformin + sulphonylurea | 39 | ||||||

| Karatoprak et al, 201322 | Turkey | 57.4±10.1 | 19/57* | HbA1c (%), body weight, BMI, PPG | 29 | 15 days | 29th day | A | Insulin premix + metformin | 12 |

| B | Insulin long-acting + metformin | 13 | ||||||||

| C | Metformin | 18 | ||||||||

| D | Metformin + pioglitazone + acarbose | 17 | ||||||||

| Şahin et al, 201321 | Turkey | 59.93±9.57 | - | PPG, FPG, HbA1c (%), body weight, fructosamine | 27 | Two week before | At the end of Ramadan | No subgroup | Glinides + metformin | 88 |

| Almutairi et al., 201226 | Kuwait | 28-67 | 36/64 | FPG, BMI, CRP, MAP | - | - | - | No subgroup | Oral antidiabetics | 100 |

| Vasan et al, 201227 | India | 45±9 | - | FPG, PPG, body weight, fructosamine, dietary pattern | 30 | One week before | One week after | No subgroup | Pioglitazone | 50 |

| Khan et al, 201234 | Pakistan | 52.8±8.5 | 38/37 | Glucose level, body weight, lipid profile | >20 | 10 days | seventh day | No subgroup | Oral antidiabetics + insulin | 75 |

| Hassanein et al, 201132 | UK | 58.3±13.1 | 11/12 | Hypoglycaemic events, HbA1c (%), body weight | >10 | One-six week | ≤ six week after | A | Metformin + vildagliptin | 23 |

| 57.3±11 | 15/21 | B | Metformin + suphonylurea | 36 | ||||||

| Khaled & Belbraouet 200925 | Multicenter study/Algeria | 49±6 | 0/276 | Anthropometric characteristics and nutrient intakes | - | One month before | One month after | No subgroup | Metformin + glimepiride | 276 |

| Devendra et al., 200935 | UK | 53.2±9.7 | 18/34 | Body weight, hypoglycaemic event, HbA1c | >15 | Two days before | 10 days after | A | Metformin + vildagliptin | 26 |

| B | Metformin + gliclazide | 26 | ||||||||

| M’guil et al, 200831 | Morocco | 48-60 | 58/62* | BMI, HbA1c (%), fructosamine | 30 | First day | 29th day | No subgroup | Gliclazide | 110 |

| Cesur et al, 200720 | Turkey | 56.5±9.2 | 29/20 | FPG, PPG, HbA1c (%), fructosamine | - | Two days before | Four days after | A | Glimepiride | 21 |

| B | Repaglinide | 18 | ||||||||

| C | Glargine | 10 | ||||||||

| Patel et al, 200736 | Sultanate of Oman | 54.3±11.7 | 146/188 | BMI, sugar intake, food intake, fluid intake | - | At the beginning of Ramadan | At the end of Ramadan | No subgroup | Insulin + oral antidiabetics | 334 |

| GLIRA study group, 200528 | Lebanon | 53.8±9.2 | 123/109 | FPG, HbA1c (%), BMI | - | One week before | At the end of Ramadan | No subgroup | Glimepiride | 232 |

| Gustaviani et al, 200429 | Indonesia | 52.6±8 | 10/14 | BMI, FPG, fructosamine | - | One week before | Two week after | No subgroup | Repaglinide | 24 |

| Sarı et al, 200419 | Turkey | 57.79±7 | - | BMI, PPG, FPG, HbA1c (%), fructosamine | - | - | - | A | Glimepiride | 23 |

| B | Gliclazide | 17 | ||||||||

| Mafauzy, 200223 | Multicenter study/Malaysia/UK/France/Saudi Arabia | 52.7±7.4 | 87/29 | FPG, HbA1c (%), BMI | - | At the beginning of Ramadan | At the end of Ramadan | A | Repaglinide | 116 |

| 54.5±6.9 | 82/37 | B | Glibenclamide | 119 | ||||||

| Uysal, 199818 | Turkey | 55 | 11/30 | HDL, LDL, HbA1c (%), BMI | - | Two week before | Last week of Ramadan | No subgroup | Diabetic diet or single or combined oral anti-diabetics | 41 |

| Belkhadir et al, 199324 | Multicenter study/Morocco | 33-80 | 391/198* | Fructosamine, HbA1c (%), body weight | - | One day before | One day after | A | Glibenclamide | 78 |

| B | Glibenclamide | 173 | ||||||||

| C | Glibenclamide | 95 | ||||||||

| D | Glibenclamide | 87 | ||||||||

| E | Glibenclamide | 101 | ||||||||

*Mismatch in total number of patients is due to dropout. SD, standard deviation; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; TG, triglyceride; BMI, body mass index; PPG, post-prandial plasma glucose; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; CRP, C-reactive protein; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein

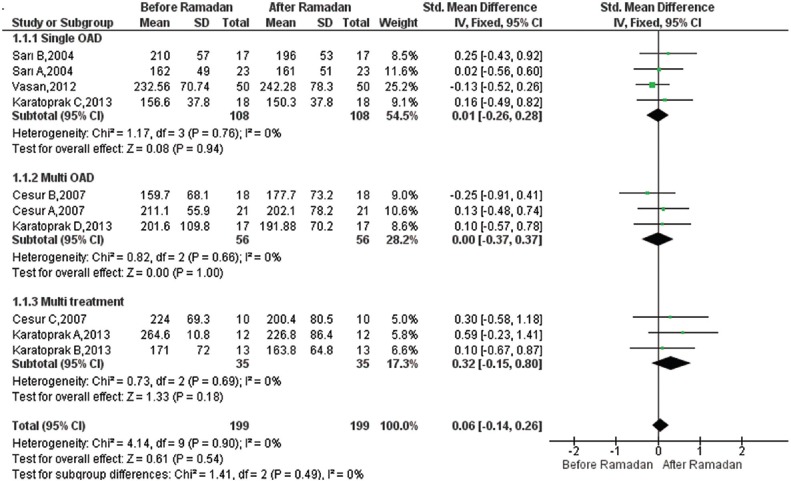

Effect of Ramadan fasting on PPG: Ten studies were included19,20,22,27 in the meta-analysis to estimate the pooled reduction in PPG after RF versus before RF. A total of 199 participants were analyzed, including 108 participants in the monotherapy and 56 participants in the oral combination therapy subgroup. RF had no significant effect in the monotherapy group [SMD=0.01, 95% CI=(−0.26, 0.28), P=0.94], and no significant difference was observed in the oral combination therapy group [SMD=0.00, 95% CI=(−0.37, 0.37), P=1.000]. The overall pooled SMD for PPG was 0.06, 95% CI=[(−) 0.14-0.26], which was not significant. SMD estimates and their 95 per cent CIs are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for pre-post Ramadan changes in post-prandial plasma glucose (mg/dl).

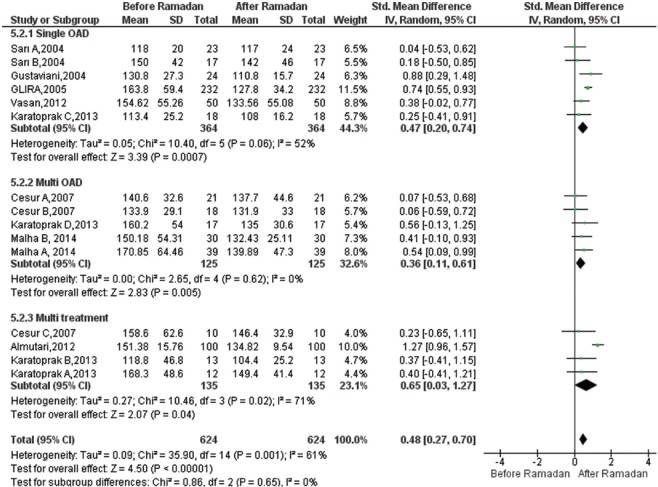

Effect of Ramadan fasting on FPG:Fifteen studies19,20,22,26,27,28,29,30 reporting estimates for FPG were included. A total of 624 participants were analyzed, including 364 participants in the monotherapy and 135 participants in the insulin combination therapy subgroup. The Figure 3 displays the results of the meta-analysis. FPG values were significantly decreased in single OAD [SMD=0.47, 95% CI=(0.20-0.74), P<0.001], in the multi-OAD group [SMD=0.36, 95% CI=(0.11-0.61), P=0.005] as well as in the insulin combination therapy after Ramadan [SMD=0.65, 95% CI=(0.03-1.27), P=0.04]. Furthermore, the overall result of meta-analysis was significant [SMD=0.48, 95% CI=(0.27-0.70), P<0.001]. There was heterogeneity across studies for FPG (I2=61%, P=0.001).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for pre-post Ramadan changes in fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl).

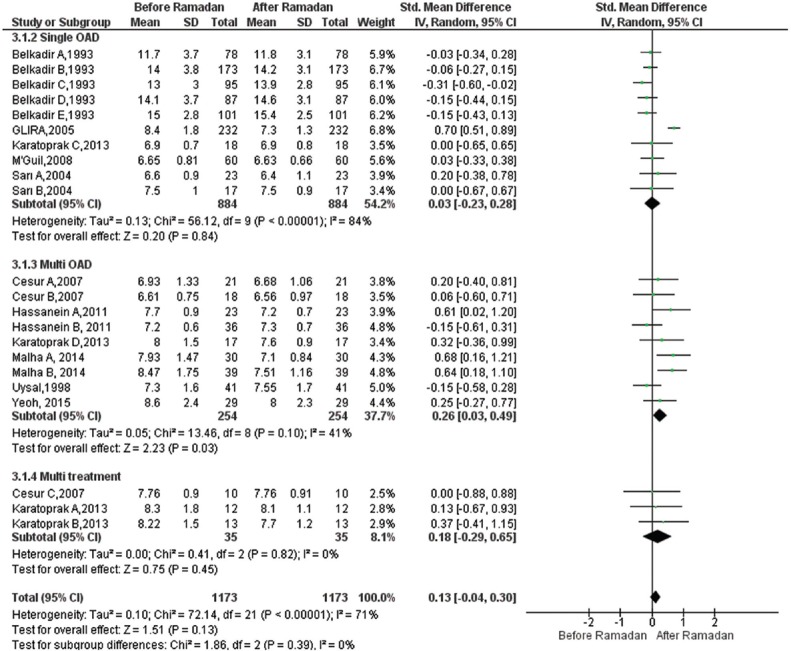

Effect of Ramadan fasting on HbA1c: A total of 22 studies18,19,20,22,24,28,30,31,32,33 provided data for the meta-analysis for HbA1c (%) change (1173 participants, 884 in single OAD, 254 in multi OAD and 35 in multitreatment). In the subgroup analysis, there was no significant difference in monotherapy group [SMD=0.03, 95% CI=([−]0.23-0.28), P=0.84] and oral combination therapy group [SMD=0.18, 95% CI=([−]0.29-0.65), P=0.45]. However, in multi-OAD subgroup, small significant reduction was observed [SMD=0.26, 95% CI=(0.03-0.49), P=0.03]. The overall results of random effects model showed that RF did not lead to significant changes in HbA1c (%) levels [SMD=0.13, 95% CI=([−]0.04-0.30), P=0.13] (Fig. 4). There was heterogeneity across studies for HbA1c (%) (I2=71%, P=0.01), but there was no difference between subgroups (P=0.72).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for pre-post Ramadan changes in glycated haemoglobin (%).

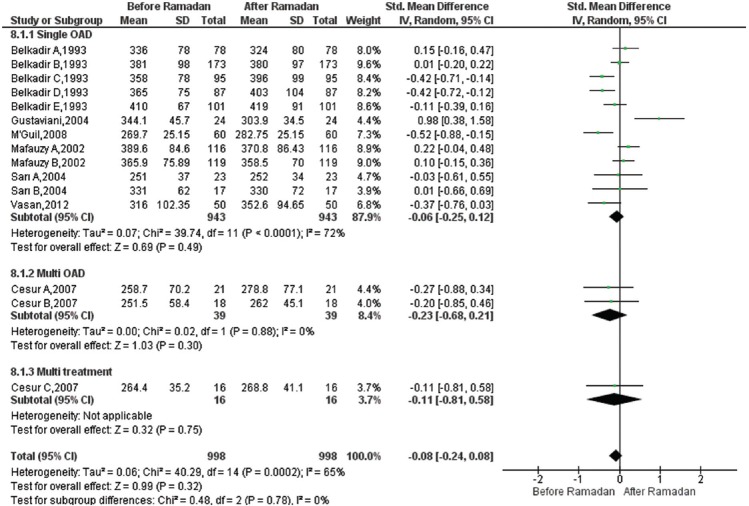

Effect of Ramadan fasting on fructosamine: Fifteen studies19,20,23,24,27,29,31 were included in the meta-analysis to estimate the pooled changes in fructosamine after RF compared to before RF. A total of 998 participants were analyzed to evaluate changes in fructosamine levels. Most of the participants received monotherapy (n=943). RF had no significant effect [SMD=(−)0.08, 95% CI=([−]0.24, 0.08), P=0.320]. SMD estimates and their 95 per cent CIs are shown in Fig. 5. There was heterogeneity across studies for fructosamine (I2=65%, P=0.001).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot for pre-post Ramadan changes in fructosamine.

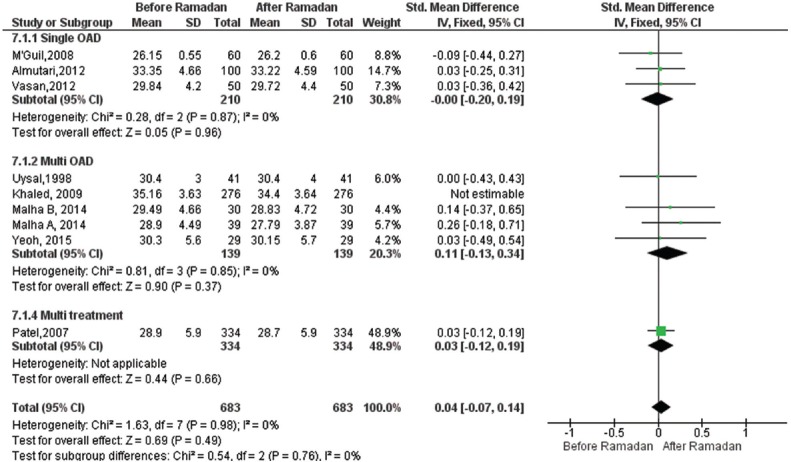

Effect of Ramadan fasting on body mass index: Nine18,26,27,30,31,33,34,35,36 studies representing T2DM population of 959 participants reported BMI scores before and after RF. Overall, meta-analysis results of the random effects model showed marginally significant reduction in BMI levels compared to pre-Ramadan levels as shown in Fig. 6 [SMD=0.09, 95% CI=([−]0.00-0.18), P=0.06]. Furthermore, in the multi-OAD group, there was a significant decrease in BMI values [SMD=0.18, 95% CI=(0.04-0.31), P=0.01].

Fig. 6.

Forest plot for pre-post Ramadan changes in body mass index.

Discussion

One major finding of our meta-analysis was the reduction in the HbA1c (%) and FPG in the multi-OAD subgroup after Ramadan. In addition to these glycaemic parameters, BMI values were lower after Ramadan in this subgroup. Another meta-analysis on healthy controls also reported significant decrease in body weight after RF6. Body weight reduction might have led to improvement in these glycaemic parameters. Norris et al37 showed that relatively modest weight loss was significantly associated with improvement in FPG and HbA1c. Fujioka38 showed that even the intention to lose weight, without significant success, improved outcomes in patients with diabetes and moderate weight loss had positive effects on metabolic control. However, another meta-analysis examining non-pharmacological weight loss in adults with T2DM did not report significant changes in HbA1c39. Another meta-analysis which assessed the benefit of low calorie diet programmes in obese patients reported dramatic reductions in FPG values after two weeks and relative improvement in FPG over the course of a single week, when three per cent decrease was achieved in body weight40. Overall results of our meta-analysis also showed significant FPG reductions after Ramadan and overall BMI result was marginally significant. We did not find a significant FPG reduction in the single OAD group. Fasting patients consume substantial amounts of sugary foods and carbohydrate-rich meals during non-fasting hours5. Therefore, monotherapy alone for the treatment of diabetes may not be sufficient for FPG control.

Since smoking is not permitted during RF, there is a consequential reduction in smoking and tobacco consumption among fasting diabetic patients. Another explanation for the improvement in FPG and HbA1c (%) could be cessation or reduction of smoking during Ramadan. In healthy young males, an increased insulin resistance was observed in acute smokers41. Other studies showed that smoking reduced insulin-mediated glucose uptake by 10-40 per cent when compared to non-smokers42,43. Other studies showed a positive association between HbA1c and total smoking exposure as measured by pack-years44,45. One of the reasons for positive outcomes of our meta-analysis could be increased treatment adherence during Ramadan. It has been shown that in most of the countries, non-adherence rates are surprisingly high during RF46,47,48. However, the VIRTUE study enrolling 1333 patients from 10 countries reported high treatment adherence during Ramadan, with low or similar number of missed doses compared to other months49.

The sensitivity analysis showed similar SMDs for all of the outcomes (Table II). For fructosamine, HbA1c (%) and FPG significant heterogeneity were detected among included studies. Not all of the included studies followed the same duration of fasting (Table I). Hence, duration of fasting may be one of the reasons for heterogeneity. Egger regression analysis showed no publication bias for PPG (P=0.068), FBG (P=0.802), BMI (P=0.622) and fructosamine (P=0.950). For HbA1c (%), publication bias was detected (P=0.015).

Table II.

Result of sensitivity analysis

| Outcome | Effect size | Heterogeneity | Sensitivity analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | P | Excluding the largest | Excluding the smallest | Excluding the earliest | Excluding studies with the most contradictory results | ||

| PPG (mg/dl) | 0.06 (−0.14-0.26) | 0 | 0.900 | 0.13 (−0.10-0.35) | 0.03 (−0.17-0.23) | 0.05 (−0.17-0.27) | 0.09 (−0.11-0.30) |

| FPG (mg/dl) | 0.48 (0.27-0.70) | 61 | 0.001 | 0.44 (0.20-0.69) | 0.49 (0.28-0.71) | 0.54 (0.32-0.76) | None |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.13 (−0.04-0.30) | 71 | 0.001 | 0.05 (−0.07-0.17) | 0.13 (−0.04-0.30) | 0.14 (−0.03-0.32) | 0.16 (−0.01-0.32) |

| BMI | 0.09 (−0.00-0.18) | 0 | 0.810 | 0.04 (−0.07-0.14) | 0.08 (−0.01-0.18) | 0.09 (−0.00-0.18) | 0.04 (−0.07-0.14) |

| Fructosamine | −0.08 (−0.24-0.08) | 65 | 0.001 | −0.09 (−0.27-0.09) | −0.08 (−0.25-0.09) | −0.03 (−0.27-0.22) | −0.05 (−0.21-0.11) |

HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; TG, triglyceride; BMI, body mass index; PPG, post-prandial plasma glucose; FPG, fasting plasma glucose

Our study had several limitations. Although studies with co-morbidities were excluded, it was very difficult to include only those cases of diabetes without co-morbid conditions, and most of the studies did not follow similar inclusion criteria. The reported rates of hypoglycaemic and hyperglycaemic and hyperglycaemic rate events vary between 3.7 and 33.3 per cent18,19,22. Since only a small number of studies reported these outcomes, we could not include them in our meta-analysis. Another limitation of our study was related to the fact that most of the included studies investigated the impact of RF just after Ramadan; therefore, sustainability of positive outcomes could not be evaluated.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis showed that RF was not associated with any significant negative effects on PPG and fructosamine levels. However, BMI and FPG and HbA1c (%) were positively affected by RF. Although RF showed positive effects on certain outcomes, one should consider the limitations of the study and confounders while interpreting the results.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: None

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Diabetes. [accessed on November 20, 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report. [accessed on August 20, 2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/2014StatisticsReport.html .

- 3.World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. [accessed on August 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/diabetes/global-report/en .

- 4.IDF Diabetes Atlas Group. Update of mortality attributable to diabetes for the IDF diabetes atlas: Estimates for the year 2013. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109:461–5. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benaji B, Mounib N, Roky R, Aadil N, Houti IE, Moussamih S, et al. Diabetes and Ramadan: Review of the literature. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;73:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kul S, Savaş E, Öztürk ZA, Karadaǧ G. Does Ramadan fasting alter body weight and blood lipids and fasting blood glucose in a healthy population? A meta-analysis. J Relig Health. 2014;53:929–42. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nutrition recommendations and principles for people with diabetes mellitus. American Diabetes Association. J Fla Med Assoc. 1998;85:25–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmedani MY, Alvi SF, Haque MS, Fawwad A, Basit A. Implementation of Ramadan-specific diabetes management recommendations: A multi-centered prospective study from Pakistan. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:37. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-13-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SWH, Lee JY, Tan CS, Wong CP. Strategies to make Ramadan fasting safer in type 2 diabetics: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2457. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray LJ, Dales J, Brady EM, Khunti K, Hanif W, Davies MJ. Safety and effectiveness of non-insulin glucose-lowering agents in the treatment of people with type 2 diabetes who observe Ramadan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:639–48. doi: 10.1111/dom.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mbanya JC, Al-Sifri S, Abdel-Rahim A, Satman I. Incidence of hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with gliclazide versus DPP-4 inhibitors during Ramadan: A meta-analytical approach. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109:226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [accessed on January 17, 2017]. Available from: http://www ohri ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford asp .

- 13.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leandro G. Meta-analysis in medical research: The handbook for the understanding and practice of meta-analysis. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong SS, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound treatment studies in EMBASE. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94:41–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cochrane reviews: Review manager (RevMan) version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uysal AR, Erdoǧan MF, Sahin G, Kamel N, Erdoǧan G. Clinical and metabolic effects of fasting in 41 type 2 diabetic patients during Ramadan. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2033–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.11.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sari R, Balci MK, Akbas SH, Avci B. The effects of diet, sulfonylurea, and Repaglinide therapy on clinical and metabolic parameters in type 2 diabetic patients during Ramadan. Endocr Res. 2004;30:169–77. doi: 10.1081/erc-200027375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cesur M, Corapcioglu D, Gursoy A, Gonen S, Ozduman M, Emral R, et al. A comparison of glycemic effects of glimepiride, repaglinide, and insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes mellitus during Ramadan fasting. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahin SB, Ayaz T, Ozyurt N, Ilkkilic K, Kirvar A, Sezgin H. The impact of fasting during Ramadan on the glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2013;121:531–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1347247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karatoprak C, Yolbas S, Cakırca M, Cinar A, Zorlu M, Kiskac M, et al. The effects of long term fasting in Ramadan on glucose regulation in type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2512–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mafauzy M. Repaglinide versus glibenclamide treatment of Type 2 diabetes during Ramadan fasting. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2002;58:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(02)00104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belkhadir J, el Ghomari H, Klöcker N, Mikou A, Nasciri M, Sabri M. Muslims with non-insulin dependent diabetes fasting during Ramadan: treatment with glibenclamide. BMJ. 1993;307:292–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6899.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khaled BM, Belbraouet S. Effect of Ramadan fasting on anthropometric parameters and food consumption in 276 type 2 diabetic obese women. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2009;29:62–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.53122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almutairi H, Alhendi MH, Alhelal B, Mouro M. The Effect of Ramadan Fasting on waist circumference (WC), body mass index (BMI), C-reactive protein (CRP), mean arterial pressure (MAP) and fasting blood sugar (FBS) in type 1 diabetic Kuwaiti Patients. MEJFM. 2012;10:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasan SK, Karol R, Mahendri NV, Arulappan N, Jacob JJ, Thomas N. A prospective assessment of dietary patterns in Muslim subjects with type 2 diabetes who undertake fasting during Ramadan. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:552–7. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.98009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glimepiride in Ramadan (GLIRA) Study Group. The efficacy and safety of glimepiride in the management of type 2 diabetes in Muslim patients during Ramadan. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:421–2. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gustaviani R, Soewondo P, Semiardji G, Sudoyo AW. The influence of calorie restriction during the Ramadan fast on serum fructosamine and the formation of beta hydroxybutirate in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Acta Med Indones. 2004;36:136–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malha LP, Taan G, Zantout MS, Azar ST. Glycemic effects of vildagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes before, during and after the period of fasting in Ramadan. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2014;5:3–9. doi: 10.1177/2042018814529062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.M'guil M, Ragala MA, El Guessabi L, Fellat S, Chraibi A, Chabraoui L, et al. Is Ramadan fasting safe in type 2 diabetic patients in view of the lack of significant effect of fasting on clinical and biochemical parameters, blood pressure, and glycemic control? Clin Exp Hypertens. 2008;30:339–57. doi: 10.1080/10641960802272442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassanein M, Hanif W, Malik W, Kamal A, Geransar P, Lister N, et al. Comparison of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor vildagliptin and the sulphonylurea gliclazide in combination with metformin, in Muslim patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus fasting during Ramadan: results of the VECTOR study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1367–74. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.579951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeoh EC, Zainudin SB, Loh WN, Chua CL, Fun S, Subramaniam T, et al. Fasting during Ramadan and associated changes in glycaemia, caloric intake and body composition with gender differences in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2015;44:202–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan N, Khan MH, Shaikh MZ, Khanani MR, Rasheed A. Effects of Ramadan fasting and physical activity on glucose levels and serum lipid profile among Type 2 diabetic patients. Pak J Med Sci. 2012;28:91–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devendra D, Gohel B, Bravis V, Hui E, Salih S, Mehar S, et al. Vildagliptin therapy and hypoglycaemia in Muslim type 2 diabetes patients during Ramadan. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1446–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel P, Mirakhur A, El-Magd KM, El-Matty AN, Al-Ghafri D. Type 2 Diabetes and its characteristics during Ramadan in Dhahira Region, Oman. Oman Med J. 2007;22:16–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norris SL, Zhang X, Avenell A, Gregg E, Schmid CH, Lau J. Pharmacotherapy for weight loss in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;25:CD004096. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004096.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujioka K. Benefits of moderate weight loss in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:186–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norris SL, Zhang X, Avenell A, Gregg E, Brown TJ, Schmid CH, et al. Long-term non-pharmacologic weight loss interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;18:CD004095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004095.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson JW, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ. Importance of weight management in type 2 diabetes: Review with meta-analysis of clinical studies. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003;22:331–9. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Attvall S, Fowelin J, Lager I, Von Schenck H, Smith U. Smoking induces insulin resistance – A potential link with the insulin resistance syndrome. J Intern Med. 1993;233:327–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1993.tb00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Facchini FS, Hollenbeck CB, Jeppesen J, Chen YDI, Reaven GM. Insulin resistance and cigarette smoking. Lancet. 1992;339:1128–30. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90730-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eliasson B, Mero N, Taskinen MR, Smith U. The insulin resistance syndrome and postprandial lipid intolerance in smokers. Atherosclerosis. 1997;129:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)06028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sargeant LA, Khaw KT, Bingham S, Day NE, Luben RN, Oakes S, et al. Cigarette smoking and glycaemia: The EPIC-norfolk study. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:547–54. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nilsson PM, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Eliasson B, Cederholm J Steering Committee of the Swedish National Diabetes Register. Smoking is associated with increased HbA1c values and microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes – Data from the national diabetes register in Sweden. Diabetes Metab. 2004;30:261–8. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ashur ST, Shamsuddin K, Shah SA, Bosseri S, Morisky DE. Reliability and known-group validity of the arabic version of the 8-item morisky medication adherence scale among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. East Mediterr Health J. 2015;21:722–8. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.10.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jamous RM, Sweileh WM, Abu-Taha AS, Sawalha AF, Zyoud SH, Morisky DE. Adherence and satisfaction with oral hypoglycemic medications: A pilot study in palestine. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33:942–8. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9561-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung WW, Chua SS, Lai PSM, Morisky DE. The Malaysian medication adherence scale (MALMAS): Concurrent validity using a clinical measure among people with type 2 diabetes in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Arouj M, Hassoun AA, Medlej R, Pathan MF, Shaltout I, Chawla MS, et al. The effect of vildagliptin relative to sulphonylureas in muslim patients with type 2 diabetes fasting during Ramadan: The VIRTUE study. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:957–63. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]