Abstract

Reiterative transcription is a non-canonical form of RNA synthesis by RNA polymerase in which a ribonucleotide specified by a single base in the DNA template is repetitively added to the nascent RNA transcript. We previously determined the X-ray crystal structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase engaged in reiterative transcription from the pyrG promoter, which contains eight poly-G RNA bases synthesized using three C bases in the DNA as a template and extends RNA without displacement of the promoter recognition σ factor from the core enzyme. In this study, we determined a series of transcript initiation complex structures from the pyrG promoter using soak–trigger–freeze X-ray crystallography. We also performed biochemical assays to monitor template DNA translocation during RNA synthesis from the pyrG promoter and in vitro transcription assays to determine the length of poly-G RNA from the pyrG promoter variants. Our study revealed how RNA slips on template DNA and how RNA polymerase and template DNA determine length of reiterative RNA product. Lastly, we determined a structure of a transcript initiation complex at the pyrBI promoter and proposed an alternative mechanism of RNA slippage and extension requiring the σ dissociation from the core enzyme.

INTRODUCTION

Non-canonical form of transcription called ‘reiterative transcription’ (also known as transcript slippage) regulates gene expression (1,2). Unlike canonical transcription in which RNA polymerase (RNAP) simply copies the DNA sequence to RNA, RNAP adds extra bases to the RNA by reiterative transcription. This is due to repetitive addition of the same nucleotide to the 3′ end of a nascent RNA while RNA slips on the template DNA (tDNA) (1–6).

The pyrG gene in Bacillus subtilis encodes CTP synthetase and its expression is regulated by CTP concentration dependent reiterative transcription (Supplementary Figure S1) (6). The initially transcribed region (ITR) of pyrG (5′-GGGCTC on the non-template DNA and 3′-CCCGAG on the tDNA; the transcription start site is underlined) contains a slippage-prone homopolymeric DNA sequence followed by a base that determines the fate of RNA extension, either canonical or reiterative, depending on the amount of CTP. In the presence of a high concentration of CTP, RNAP transcribes RNA without slippage (5′-GGGCUC) and continues until an attenuator sequence, which forms the transcription termination hairpin, thereby eliminating pyrG expression (Supplementary Figure S1, left). On the other hand, when CTP is limited, right after 5′-GGG-3′ RNA is synthesized, RNAP starts reiterative transcription and inserts up to 10 extra G bases to the nascent RNA before returning to canonical transcription (5′-GGGGnCUC, n = 1–10), resulting in the formation of an anti-termination hairpin with the pyrimidine-rich sequence in the 5′ part of the attenuator, thereby allowing expression of the pyrG gene (Supplementary Figure S1, right).

Another well-known example of conditional reiterative transcription is UTP-sensitive regulation of transcript initiation at the pyrBI operon of Escherichia coli (7). The pyrBI ITR (5′-AATTTG, non-template DNA; transcription start site is underlined) contains a slippage-prone sequence (italicized) (Supplementary Figure S2), where transcript slippage produces transcripts with the sequence 5′-AAUUUn (where n = 1 to >100) (7). In contrast to the regulation of the pyrG promoter where reiterative transcription eventually switches to canonical transcription to express the pyrG operon (Supplementary Figure S1), the reiterative transcripts at the pyrBI promoter are released from the transcript initiation complex (TIC; Supplementary Figure S2, left) (2).

Since first proposed in the early 1960s in the E. coli RNAP transcription (3), reiterative transcription has been discovered and characterized not only in cellular RNAPs from bacteria to humans but also in virus RNAPs (8–16). To best of our knowledge, only a structural study of the HIV reverse transcriptase with a polypurine tract showed a non-canonical form of DNA:RNA hybrid away from the active site that may involve both slipped and mismatched bases (17); however, the mechanism of reiterative transcription remains to be elucidated due to lack of atomic structures showing the slipped RNA and mismatched bases of tDNA and RNA near the active site of RNAP.

Previously, we reported the X-ray crystal structure of the reiterative transcription complex (RTC) from the pyrG promoter, which was prepared by in crystallo RNA synthesis in the presence of GTP in a 30-min reaction within the crystal of bacterial RNAP and pyrG promoter DNA complex (RTC-30′) (18). The structure represented the final stage of reiterative transcription, revealed the presence of 8-mer poly-G RNA and showed that three bases at the 3′ end form a DNA/RNA hybrid and a fourth base from the 3′ end of RNA (−4G) fits into the rifampin (RIF)-binding pocket of the β subunit of RNAP. These features allow RNA to detour from the dedicated RNA exit channel and extend toward the main channel of the enzyme without displacement of the σ factor. The 3′ end of RNA is in a post-translocated state (i.e. in the i site), forming a base pair with tDNA residue +3C, whereas the +4G base is positioned at the i + 1 site, poised for incoming CTP to extend the nascent RNA by canonical transcription. The structure revealed an unexpected RNA extension pathway during reiterative transcription; however, several questions remain to be answered such as how RNA slips on tDNA and how the 5′ end of RNA is guided toward the main channel of RNAP.

In this study, we further study the mechanism of reiterative transcription from the pyrG promoter by structural and biochemical approaches. We determined a series of X-ray crystal structures of the RNAP and pyrG promoter complex containing 2-, 3- and 4-mer RNAs. Additionally, we determined a series of structures with pyrG promoter variants containing base substitution at the tDNA −1 position and revealed a role of this tDNA base for guiding RNA toward the RIF-binding pocket. Lastly, we investigate the reiterative transcription from the pyrBI promoter by structural and biochemical studies to propose an alternative way of reiterate RNA extension.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and purification of Thermus thermophilus and E. coli RNAPs

Thermus thermophilus and E. coli RNAP holoenzymes were prepared as described previously (19,20).

Preparation of promoter DNA scaffolds for the crystallization, the DNA translocation assay and the in vitro transcription assay

The promoter DNA scaffold that resembles the B. subtilis pyrG promoter and its variants, and the E. coli pyrBI promoter were constructed using two oligodeoxynucleotides for template and non-template DNA strands. The DNA oligonucleotides used for the crystallization, the DNA translocation assay and the in vitro transcription assay are synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and their sequences are shown in Supplementary Tables S1–S3. DNA strands were annealed in 40 μl containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA to the final concentration of 0.5 mM. The solutions were heated at 95°C for 10 min and then the temperature was gradually decreased to 22°C.

Crystallization of the T. thermophilus RNAP promoter DNA complexes

The crystals of the RNAP and promoter DNA complex were prepared as described previously (18). To prepare the crystals of RTC from the pyrG promoter, the RNAP and pyrG DNA complex crystals were transferred to cryoprotection solution containing 1 mM GTP, harvested from the soaking solution at indicated time points and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. To prepare the crystals of TIC from the pyrBI promoter, the RNAP and pyrBI DNA complex crystals were transferred to a cryoprotection solution containing 5 mM ATP, 5 mM UTP and 500 μM GTP for 1 h and then frozen by liquid nitrogen.

X-ray data collections and structure determinations

The X-ray datasets were collected at the Macromolecular Diffraction at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (MacCHESS) F1 beamline (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) and structures were determined as previously described (18,19) using the following crystallographic software: HKL2000 (21), Phenix (22) and Coot (23).

In vitro transcription assay

The transcription assays on the pyrG promoter and its variants were performed in 10 μl containing 250 nM RNAP holoenzyme, 250 nM DNA, 100 μM GTP and 32P-labeled pGpGpG primer in the transcription buffer [40 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8 at 25°C), 30 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 15 μM acetylated BSA and 1 mM DTT]. RNAP–DNA–primer were pre-incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After adding GTP, the samples were incubated at 37°C for 10 min and the reaction was stopped by adding 10 μl of stop buffer (90% formamide, 50 mM EDTA, xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue). The transcription assay on the pyrBI promoter was performed in 10 μl containing 250 nM RNAP holoenzyme, 250 nM DNA, 100 μM GTP, 100 μM ATP, [γ-32P] ATP and 5 mM to 10 μM UTP. The reaction products were electrophoretically separated on a denaturing 24% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel and visualized with a phosphorimager (Typhoon 9410, GE Healthcare).

Monitoring DNA translocation during reiterative transcription in solution using 2-aminopurine (2-AP) fluorescence (equilibrium study)

E. coli RNAP holoenzyme (500 nM) and DNA (100 nM) were pre-incubated in the transcription buffer for 10 min at 25°C. Transcription complex was prepared by mixing one or more indicated NTPs (each at 200 μM) for 15 min at 37°C. The fluorescence was detected at excitation and emission wavelengths of 315 and 375 nm, respectively, using a Spectramax-M5 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices).

Measurement of DNA translocation kinetics during reiterative transcription

Stopped-flow studies were performed on an Applied Photophysics SX20 stopped-flow machine equipped with a fluorescence detector. All experiments were performed at room temperature (23 ± 2°C) in the transcription buffer and the final ionic strength was adjusted to 100 mM by the addition of appropriate amounts of KCl. Syringe A (70 μl) containing the E. coli RNAP holoenzyme (500 nM) and DNA (100 nM) was mixed with an equal volume of Syringe B (70 μl) containing one or more NTPs (each at 200 μM). Upon mixing, 2-AP fluorescence was monitored by exciting at 315 nm and monitoring the emission using a 350-nm cutoff filter (Andover Corporation, Salem, NH). The fluorescence traces were recorded by collecting 1000 total time points over 10 s. All traces were analyzed using Applied Photophysics ProData™ and KaleidaGraph software.

RESULTS

Capturing TICs from the pyrG promoter by X-ray crystallography

We applied time-dependent soak–trigger–freeze X-ray crystallography (24) to determine a series of structures representing early stage of transcription from the pyrG promoter. We previously demonstrated that T. thermophilus σA RNAP holoenzyme is proficient at reiterative transcription from the B. subtilis pyrG promoter both in vitro and in crystallo (18). The crystals of T. thermophilus RNAP and DNA complex containing the pyrG promoter sequence (Supplementary Table S1) were soaked into a cryo-solution containing GTP to trigger RNA synthesis in crystallo. The reaction was stopped by freezing crystals at different time points (from 1 min to 2 h; Figure 1A) and the structures were determined by molecular replacement (Supplementary Table S4). Each structure presented here shows electron density corresponding to in crystallo synthesized RNA, allowing us to monitor extension of poly-G RNA. The length of RNA increases as the crystal soaks in the GTP solution (Figure 1B).

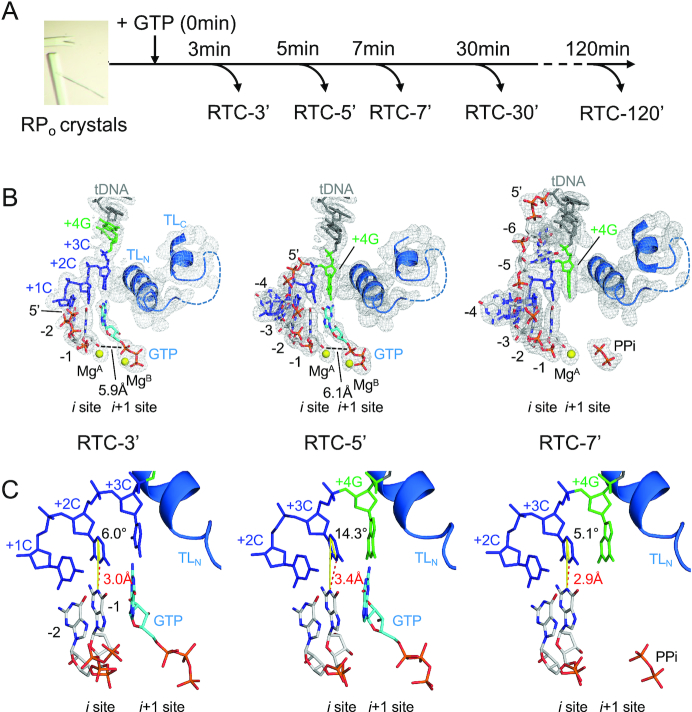

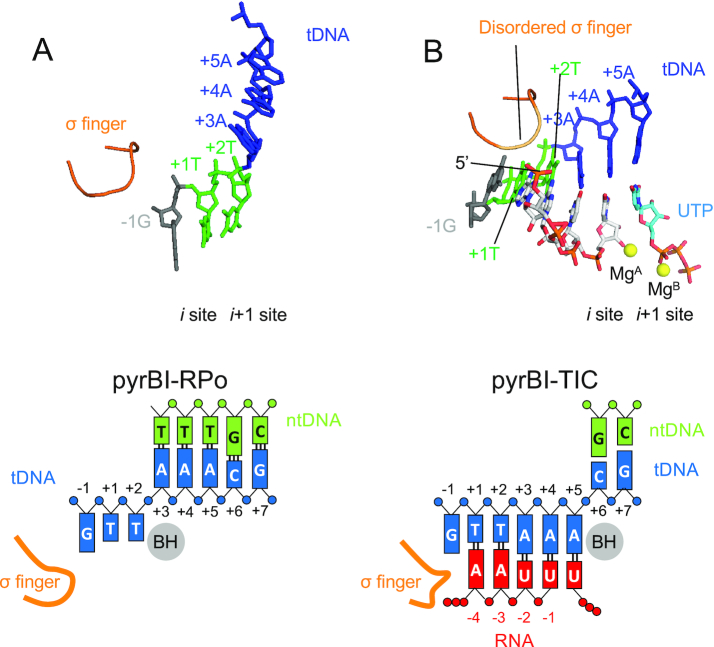

Figure 1.

The structures of RTC from the pyrG promoter. (A) Experimental scheme of the RTC preparation by time-dependent soak–trigger–freeze X-ray crystallography. (B) Structures of the RTC-3′ (left), RTC-5′ (middle) and RTC-7′ (right). RNA, tDNA and incoming GTP are shown as stick models, the Mg ions bound at the active site of RNAP are shown as yellow spheres and the RNAP trigger loop is depicted as a ribbon model. The 2Fo–Fc electron densities for RNA, tDNA and trigger loop are shown (gray mesh, 1.5σ). (C) Analysis of the DNA and RNA base parings at the i site of RNAP active site (RTC-3′, left; RTC-5′, middle; RTC-7′, right). The distances between N1 (RNA G base) and N3 (tDNA C base) are shown as red dashed lines. The angles of the DNA and RNA base pairing [from N1(RNA G base) to C5(tDNA C base) to N3(tDNA C base)] are shown as yellow lines.

After 3 min of GTP soaking (RTC-3′, Figure 1B, left, and Supplementary Figure S3A), RNAP synthesizes 2-mer RNA and its 3′ end is positioned at the i site (post-translocated state), forming a base pair with +2C tDNA. Hereafter, RNA residues are counted −1, −2 and −3 from the 3′ end. The +3C tDNA is positioned at the i + 1 site and forms a base pair with an incoming GTP. The α-phosphate of GTP is 5.9 Å away from the 3′-OH of RNA and the trigger loop is in the open conformation, indicating that the GTP is positioned at the pre-insertion site. The structure of RTC after 4 min of GTP soaking (RTC-4′, data not shown) was the same as the structure of the RTC-3′.

After 5 min of GTP soaking (RTC-5′, Figure 1B, middle, and Supplementary Figure S3B), RNA extends to 4-mer and its 3′ end is positioned at the i site, forming a base pair with +3C tDNA, while +4G tDNA is positioned at the i + 1 site. The first three bases of RNA are synthesized by canonical transcription, whereas the fourth base is added by reiterative transcription. The 5′ end of 4-mer RNA (−4G) is inserted into the RIF-binding pocket, as observed in the previously published RTC structure (RTC-30′) containing 8-mer RNA, indicating that the 5′ end of RNA base fits in the RIF-binding pocket followed by extension toward the main channel of RNAP. In the RTC-5′, incoming GTP bound at the i + 1 site forms a mismatch with the +4G tDNA and the trigger loop is in the open conformation.

At 7 min (RTC-7′, Figure 1B, right, and Supplementary Figure S3C), RNA is extended to 6-mer and the 5′-end RNA base positions at fork loop 2 of the β subunit and the downstream edge of the transcription bubble. The 3′ end of the RNA is positioned at the i site, forming a base pair with +3C tDNA, while +4G tDNA positions at the i + 1 site as observed in the RTC-5′. The NTP-binding i + 1 site is empty but traps pyrophosphate. The +4G tDNA is waiting for GTP for further extension of the poly-G transcript. We also prepared the RTC by soaking GTP for 2 h, but there was no further RNA extension beyond 8-mer RNA (data not shown) as observed in the RTC-30′, indicating that the 8-mer RNA is the longest RNA produced by in crystallo transcription. A series of structures of RTC show that (i) extra G bases are added at the RNA 3′ end by the G–G mismatch between the +4G tDNA and incoming GTP and (ii) the fitting of −4G RNA in the RIF-binding pocket is an obligatory step before RNA extension beyond 4-mer RNA.

Comparison of the distances between bases to characterize hydrogen bonds

We captured the progression of RNA synthesis, from 2-mer to 8-mer, within the RTC crystals. In case of transcription from the pyrG promoter, the first three bases of RNA are synthesized by canonical transcription (e.g. RTC-3′) and then RNA synthesis is continued by reiterative transcription (e.g. RTC-5′, RTC-7′ and RTC-30′) (Figure 1B). To gain insight into the RNA slippage mechanism, we analyzed the DNA and RNA base pairing at the i site of these structures. We assessed the distance between bases and the planarity of the base pair, which could be affected by GTP binding at the i + 1 site during canonical and reiterative transcriptions. The distance between N1 of the G base of the RNA and N3 of the C base of the tDNA accommodated at the i site of RTC-3′ is 3.0 Å, whereas it is extended to 3.4 Å in case of the RTC-5′ containing the G–G mismatch at the i + 1 site (Figure 1C, left and middle). An average distance between C (DNA) and G (RNA) bases in atomic resolution DNA/RNA hybrid crystal structures is 2.9 Å with a minimum 2.75 Å and maximum 3.15 Å (25–27). We therefore concluded that the base pair between tDNA (+3C) and 3′ end of RNA is wobbled when RNAP switches the mode of RNA synthesis from canonical to reiterative transcription. The distance between C and G bases at the i site returns to 2.9 Å without GTP bound at the active site (RTC-7′, Figure 1C, right) or when the RTC has completed poly-G RNA extension (RTC-30′) (18). Not only a distance between bases, but also planarity of base pair at the i site is impaired during reiterative transcription. In the RTC-5′, +3C base of the tDNA is tilted about 15° toward the incoming GTP bound at the i + 1 site (Figure 1C, middle, and Supplementary Figure S4). A major difference found in the RTC-5′ compared with other RTC structures is the presence of an incoming GTP at the i + 1 site, forming a G–G mismatch with the tDNA +3G base, which may wobble base pairing at the i site and initiate RNA slippage.

Monitoring DNA translocation state during reiterative transcription in solution using 2-AP fluorescence signal

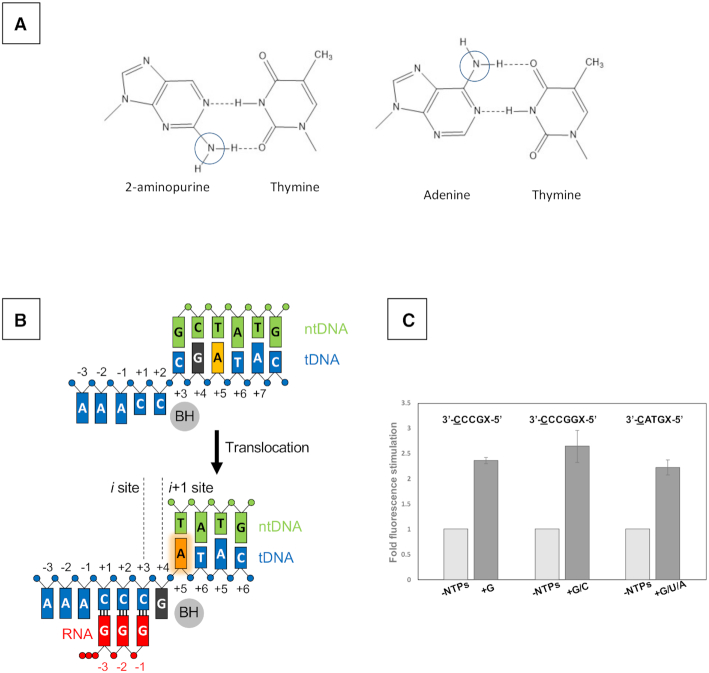

The RTC-5′, RTC-7′ and RTC-30′ structures show that the +4G DNA base is translocated into the i + 1 site when extra G residues are added to RNA during reiterative transcription (Figure 1B). To validate this observation in solution, we monitored tDNA position during transcription by fluorescence signal of 2-AP incorporated in the tDNA. 2-AP is an adenine analogue (Figure 2A) (28) and its fluorescence intensity is affected by its environment (29,30). 2-AP displays weak and strong fluorescence signals when it stacked and unstacked with neighboring bases, respectively (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure S5) (31,32).

Figure 2.

Monitoring equilibrium DNA translocation state in solution using 2-AP. (A) The fluorophore 2-AP mimics the structure of natural adenine base and participates in the Watson–Crick interaction with thymine. Chemical difference between 2-AP and adenine bases are indicated by cycles. (B) Reaction scheme of reiterative transcription at the pyrG promoter. (C) Fluorescence signal from 2-AP substituted at +5 or +6 position of the template strand DNA. Sequences of tDNA used for each experiment are shown (transcript initiation site, underlined; 2-AP position, X). The similar fork DNA scaffold used for crystallization, including transcription bubble and pyrG promoter initially transcribing region, was used as tDNA.E. coli RNAP holoenzyme was used for the assay. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean.

We prepared two DNA scaffolds containing a guanine DNA base as a quencher of 2-AP fluorescence with 2-AP at the +4 and +5 positions of the tDNA, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). One scaffold contains the tDNA sequence 3′-CATGX-5′ (transcription start site is underlined; X = 2-AP) for canonical transcription (Supplementary Figure S5B) and another scaffold contains an RNA slippage-prone tDNA sequence, 3′-CCCGX-5′, for reiterative transcription (Figure 2B). For this assay, we used the E. coli RNAP σ70 holoenzyme since it is proficient at reiterative transcription from the pyrG promoter (18).

In the case of the canonical transcription DNA template, 2-AP displays low fluorescence in the RNAP–DNA complex (-NTPs, 2-AP positioned at +5 site remains stacked with a quencher G base at +4 site), whereas it shows increased fluorescence after adding GTP, UTP and ATP in the RNAP–DNA complex (+G/U/A, Figure 2C right). The control experiments show that adding single NTP does not change fluorescence signal (Supplementary Figure S5C). The result indicates that after 3-mer RNA synthesis, the +4G DNA base moves to the active site of RNAP (i + 1 site), leaving the 2-AP unstacked with +4G (Supplementary Figure S5B).

In the case of the reiterative transcription DNA template, 2-AP fluorescence increases upon addition of GTP (but not ATP, CTP or UTP) to the RNAP–DNA complex for synthesizing 3-mer or longer RNA (Figure 2C left and Supplementary Figure S5C), demonstrating that the +4G tDNA is translocated to the i + 1 site of the RNAP active site, which is consistent with the observation from the structural analysis of RTC (Figure 1).

We also tested another DNA scaffold containing the pyrG transcription start site sequence but with an extra G base after +4G tDNA (Figure 2C middle) as a control, which would maintain the base stacking interaction between +5G and 2-AP while RNAP is engaged in reiterative transcription (Supplementary Figure S5A). When only GTP is mixed to the RNAP–DNA complex, 2-AP displays low fluorescence while the solution containing GTP and CTP that allows for translocation of +5G and 2-AP at the i + 1 and i + 2 sites, respectively, shows increased fluorescence signal (Figure 2C middle).

Kinetics of transcription-induced increase in fluorescence of 2-AP promoter DNA

A series of the RTC structures determined in this study revealed that RNAP requires 4–5 min to synthesize 5-mer RNA from the pyrG promoter by in crystallo transcription, which is substantially slower than RNA synthesis from a promoter without a slippage-prone sequence. For example, the structure of the initially transcribing complex containing 6-mer RNA (PDB: 4Q5S) (19), which contains the tDNA sequence 3′-TGAGTGC-5′, requires only 20 s to produce 6-mer RNA in crystallo in the presence of ATP, CTP and UTP.

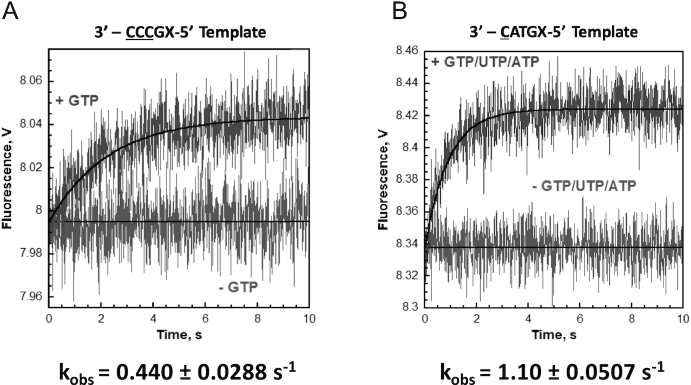

To measure the speed of RNA synthesis from slippage-prone DNA in solution, we monitored the fluorescence of 2-AP embedded in tDNA at the +5 position with the stopped-flow technique. We used the same DNA (Supplementary Table S2) for determining the DNA translocation state during reiterative and non-reiterative transcription. These DNA templates require at least 3-mer RNA synthesis for enhancing the 2-AP fluorescence signal. The data were best fit to a single exponential equation and kinetic values of the fluorescence signal from 2-AP are shown in Figure 3. The rates of DNA translation of the RNA slippage-prone and the canonical transcription DNA templates are ∼0.44 and ∼1.1 s−1, respectively, indicating that RNA synthesis from the slippage-prone DNA is substantially slower than that from the DNA for canonical transcription (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of change in 2-AP fluorescence as measured by stopped-flow analysis. Time dependence of the increase in fluorescence upon mixing nucleotides to the reiterative transcription DNA template (A) and the canonical transcription DNA template (B). Each fluorescence trace represents the average of at least seven shots. For each DNA template, the observed increase in fluorescence was fit to a single exponential rise. If NTPs were omitted, a change in the fluorescence signal was not observed. The kinetic values are indicated.

A role of the upstream sequences of the transcription start site of pyrG promoter

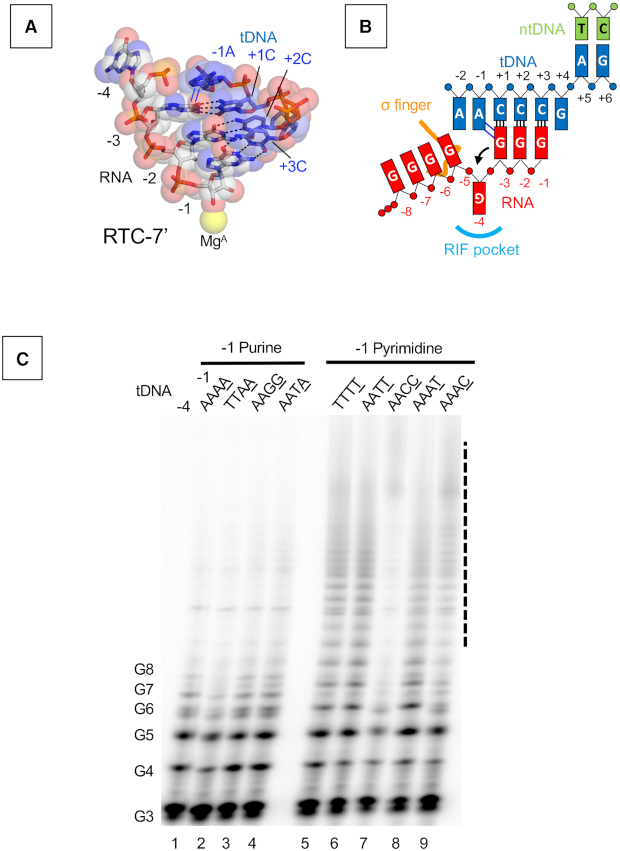

Reiterative transcription from the pyrG promoter places the −4G RNA base in the RIF-binding pocket. The RTC-7′ and RTC-30′ structures showed the −1A base of tDNA partially overlapping with the −3G base of RNA (Figure 4A). Such base stacking is only possible in the presence of a purine (tDNA) and purine (RNA) combination (adenine in tDNA and guanine in RNA in the case of pyrG promoter transcription) (Figure 4B). Consistent with this fact, the upstream sequence of the transcription start site of the pyrG promoter is highly conserved in other closely related bacteria, and particularly, tDNA bases at positions −1 and −2 are adenine in a majority of promoters (Supplementary Figure S6). We therefore hypothesized that the −1A tDNA may block RNA extension toward the RNA exit channel, thereby the −4G RNA base is pushed into the RIF-binding pocket when RNA slips on the tDNA.

Figure 4.

Role of the −1 tDNA base in reiterative transcription. (A) DNA and RNA hybrid region of the RTC-7′ structure. Base parings and base stacking interactions are depicted as black dashed lines and blue lines, respectively. (B) Schematic representation of reiterative transcription from the pyrG promoter and the base stacking interaction between the −1 tDNA adenine base and the guanine base of RNA at −1 position. (C) In vitro transcription assays measuring poly-G RNA production at the pyrG variant promoters. Sequences of tDNA from −4 to −1 positions used for the transcription assay are indicated above each lane. 32P-labeled pGpGpG primer (20 μM), corresponding to positions +1 to +3 of the promoter in the presence of GTP (100 μM), was used. Positions of the poly-G products are indicated. Poly-G RNAs longer than eight bases are indicated as a dashed line.

First, we investigated the role of adenine bases of tDNA by in vitro transcription (Figure 4C). The pyrG promoter from B. subtilis contains four adenine bases from the −4 to −1 positions in the tDNA. We prepared a series of pyrG promoter variants with substitutions from the −4 to −1 positions (Supplementary Table S3) and tested their abilities to produce reiterative transcripts. The reaction was performed in the presence of a pGpGpG primer complementary to the tDNA positions from +1 to +3 and GTP for efficient RNA extension. The wild-type promoter produces poly-G RNA around eight bases in length, and adenine bases at −4, −3 and −2 tDNA can be substituted with thymine without changing the activity of reiterative transcription (Figure 4C, lanes 1, 2 and 4). Guanine substitutions at −2 and −1 positions of tDNA did not influence the transcription (Figure 4C, lane 3). In contrast, pyrG derivatives containing thymine or cytosine substitutions at the −1 position increased the length of poly-G RNA transcript substantially (20-mer or longer) (Figure 4C, lanes 5–9, and Supplementary Figure S7). These results indicate that the tDNA base at the −1 position determines the length of reiterative RNA product from the pyrG promoter; short RNAs are synthesized in the presence of adenine and guanine (purine bases) and longer RNA are produced in the presence of thymine and cytosine (pyrimidine bases).

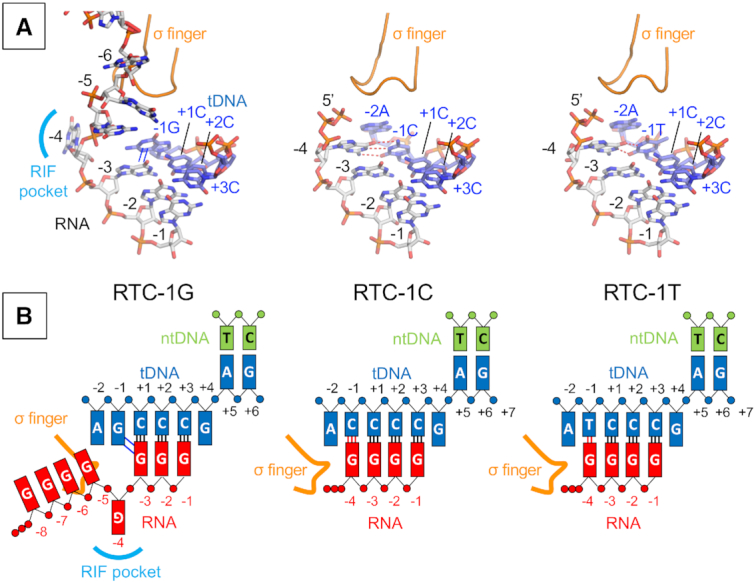

Structural analysis of the role of −1 base of tDNA during reiterative transcription

To understand how the −1 base of tDNA determines the length of reiterative transcription products, we solved the crystal structures of RTC containing pyrG variants having tDNA bases of −1G, −1C and −1T (Figure 5A, and Supplementary Table S5). All RTC structures show electron densities corresponding to poly-G RNA products starting from the RNAP active site; however, the position of the 5′ end of RNA is different depending on the sequence of tDNA. In the case of the RTC containing −1G tDNA (RTC-1G) (Figure 5A, left), the RNA is accommodated as found in the wild-type RTC; the RNA forms a 3-bp hybrid with tDNA, the −3G RNA base partially overlaps with −1G tDNA base, the −4G RNA base fits into the RIF-binding pocket and the 5′ end of RNA extends toward the main channel (Figure 5B, left). In sharp contrast, the RTCs with −1C and −1T tDNA bases (RTC-1C and RTC-1T) (Figure 5A, middle and right) contain a 4-bp DNA/RNA hybrid; −4G RNA base forms a Watson–Crick base pair (C–G) with tDNA base (−1C) in the RTC-1C and a wobble base pair (T–G) with tDNA base (−1T) in the RTC-1T (Figure 5B, middle and right). In both structures, the triphosphate of RNA contacts the tip of σ finger (residues 321–327). The path of RNA in the RTC-1C and RTC-1T is the same as the initially transcribing complex containing a 6-bp DNA/RNA hybrid (PDB: 4G7H) (19).

Figure 5.

The structures of RTC from the pyrG promoter variants. (A) Structures of the RTC-1G (left), RTC-1C (middle) and RTC-1T (right). RNA and tDNA are shown as stick models and the σ finger is depicted as a ribbon model. Base stacking and base paring interactions are depicted as blue lines (in RTC-1G) and red dashed lines (in RTC-1C and RTC-1T), respectively. (B) Schematic representations of reiterative transcription from the pyrG promoter variants containing −1G (RTC-1G, left), −1C (RTC-1C, middle) and −1T (RTC-1T, right).

Structure of an TIC at the pyrBI promoter

Reiterative transcription from the pyrBI operon of E. coli produces much longer RNA products in the presence of ATP and high concentration of UTP (Supplementary Figure S8B) (7), which is akin to the transcription from the pyrG promoter variant containing a pyrimidine base at −1 tDNA (Figure 4C). To study similarity and difference of reiterative transcription from the pyrBI and pyrG promoters, we determined the crystal structures of the RNAP and DNA complex containing the pyrBI promoter and its TIC by soaking crystal into a solution containing ATP and UTP (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table S6). In the RNAP and DNA complex structure, thymine bases of tDNA position at the i and i + 1 sites of the RNAP active site, showing that the RNA synthesis starts from +1 position. The TIC structure shows the RNAP active site containing 4-mer RNA (5′-AAUU) with a UTP positioned at the pre-insertion site (Figure 6B). RNA extends directly toward the σ finger and steric clash between the RNA triphosphate and σ finger prohibits RNA extension beyond 4-mer RNA.

Figure 6.

The structures of the TIC from the pyrBI promoter. Structures of the RNAP–pyrBI promoter complex (pyrBI-RPO, A) and TIC (pyrBI-TIC, B). RNA and tDNA are shown as stick models and the σ finger is depicted as a ribbon model. The Mg ions bound at the active site of RNAP are shown as yellow spheres. Schematic representations of the pyrBI-RPO (left) and pyrBI-TIC (right) are shown in lower panels.

DISCUSSION

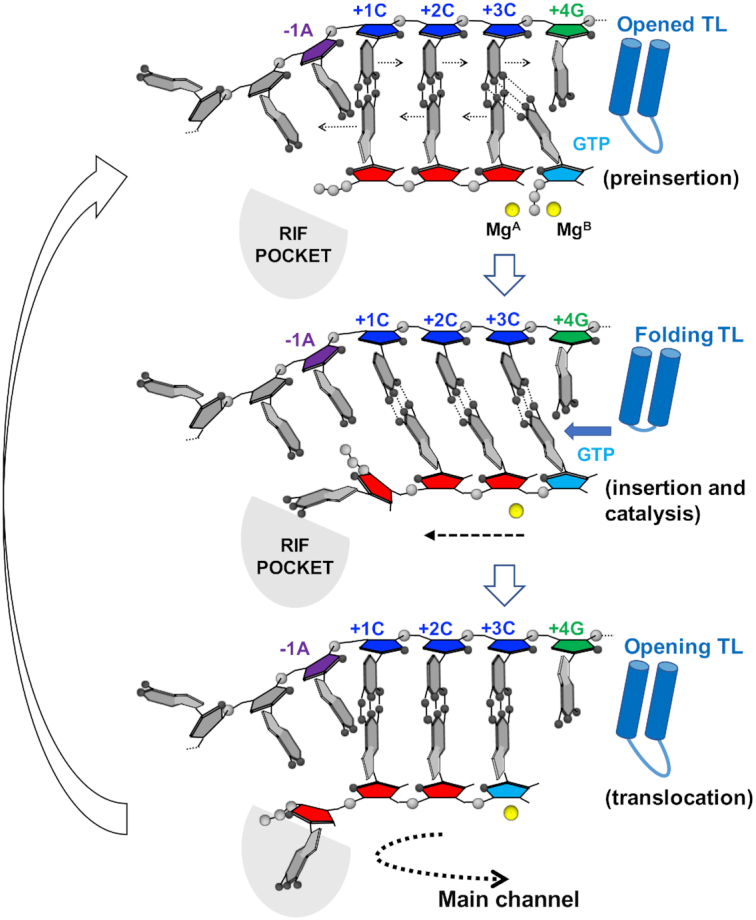

In this study, using time-dependent soak–trigger–freeze X-ray crystallography, we analyzed how RNAP synthesizes RNA from the pyrG promoter by reiterative transcription. The first three RNA bases are synthesized without RNA slippage, which is a simple copy of DNA sequence to RNA. In the case of a CTP limited condition, RNAP extends RNA with GTP by reiterative transcription (Supplementary Figure S1). The structure of RTC-5′ containing 4-mer RNA, which represents the transcript initiation complex right after the mode of RNA synthesis has switched, revealed that +4G tDNA is positioned at the active site of RNAP (i + 1 site) and forms a mismatch pair with an incoming GTP using an anti–anti conformation (Figure 1B, middle). The structure also revealed that a base pair between tDNA (+3C tDNA) and the 3′ end of RNA positioned at the i site is wobbled and the +3C tDNA base is tilted toward an incoming GTP, likely due to a mismatch between +4G tDNA and incoming GTP (Figure 1C, middle). The opening of the trigger loop causes the α-phosphate of GTP to be 6.1 Å away from the 3′-OH of RNA and maintain GTP in a non-reactive state for the nucleotidyl transfer reaction. We speculate that the trigger loop would then adapt the completely closed conformation transiently, forming the trigger helix, to load the GTP in the reactive state followed by the nucleotidyl transfer reaction (Figure 7, top). RNA extension may trigger base sharing of the +3C tDNA with guanine bases of RNA at the i and i + 1 sites and would promote shifting of the DNA/RNA hybrid in a stepwise manner (Figure 7, middle). This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the base pairs upstream from the i site are not wobbled. After RNA is extended, only RNA translocates in the upstream direction to prepare for the next cycle of reiterative transcription (Figure 7, bottom). This prediction is supported by the results of 2-AP fluorescence-based DNA translocation assay (Figures 2 and 3). Extending RNA from 3-mer to 4-mer determines the fate of RNA synthesis from the pyrG promoter. Translocating +4G tDNA at the active site (i + 1 site) after 3-mer RNA synthesis is also observed in the DNA translocation assay by monitoring the 2-AP fluorescence signal from tDNA (Figure 2). The +4G tDNA moving at the active site is essential for regulating pyrG expression depending on CTP availability; when the CTP concentration is high enough, CTP is loaded at the active site, forms a base pair with +4G tDNA and RNAP undergoes canonical transcription (Supplementary Figure S1). Previous study by Meng et al. observed the similar reiterative transcription pattern when the +4G tDNA was replaced with either A or T (6), further suggesting that the mismatch between the +4 tDNA and incoming GTP favors transcript slippage at pyrG promoter.

Figure 7.

Proposed model of RNA slippage during reiterative transcription from the pyrG promoter. Cartoon model of the active site of RNAP. pyrG ITR sequence (tDNA, −1A: purple, +1C, +2C, +3C: blue, +4G: green), nascent RNA (5′-GGG-3′, red), incoming nucleotide (GTP, cyan), active site Mg2+ (yellow sphere), trigger loop (blue shape) and RIF-binding pocket (RIF POCKET, gray) are shown. A direction of RNA extension is indicated by a dashed line.

In vitro transcription assays (Figure 4C) and the structures of the RTCs containing pyrG promoter variants (Figure 5) revealed the nature of tDNA base at the −1 position, either purine or pyrimidine, determines the fates of poly-G transcripts regarding length and direction. In the case of tDNA having a purine base (guanine or adenine) at the −1 position, RNAP synthesizes RNA around 8-mer in solution (Figure 4C, lanes 1–4) and in crystallo. The 5′ base of RNA sterically clashes with a purine base of tDNA at −1 position when RNA slips on the tDNA for the first time, resulting in flipping an RNA base into the RIF-binding pocket (Figure 4A and B). It is important to note that the steric collision between the RNA and tDNA bases only happens during reiterative transcription. Further reiterative transcription extends RNA toward the main channel of RNAP until around 8-mer length. RNA synthesis eventually switches to canonical transcription when a CTP molecule is incorporated into the 3′ end of the transcript (Supplementary Figure S1).

In the case of tDNA having a pyrimidine base at the −1 position (−1C and −1T), RNAP synthesizes RNA over 40-mer in solution (Figure 4C, lanes 5–8) but only 4-mer in crystallo (Figure 5). The structures show that a pyrimidine base of tDNA does not hinder RNA movement toward the dedicated RNA exit channel, which allows for a base pair between the 5′ end of RNA and the −1 tDNA base right after the first RNA slippage event (Watson–Crick or wobble base pair in case of −1C and −1T, respectively), resulting in forming a 4-bp DNA/RNA hybrid (Figure 5). The reiterative transcript extends toward the σ finger, which may trigger the release of σ factor from the core enzyme for longer RNA extension. RNAP can extend RNA only 4-mer in crystallo because σ cannot be released from the core enzyme due to crystal packing.

It has been demonstrated that two short segments of the 5′ untranslated region of pyrG are required for CTP concentration-dependent regulation, including the ITR of the pyrG promoter (5′-GGGC; transcription start site is underlined) and the pyrimidine-rich sequence of the attenuator (Supplementary Figure S1) (6,33). In addition to these DNA cis-elements, in this study, we shed light on the function of the purine-rich sequence of tDNA just upstream of the transcription start site. These bases, particularly a purine base at −1 tDNA position, maintain the length of DNA/RNA hybrid to three bases and guide the 5′ end of RNA toward the RIF-binding pocket of RNAP, which is an obligatory step for RNA extension toward the main channel of RNAP. Reiterative RNA synthesis pauses around 8–10 bases when the 5′-end RNA reaches the narrow opening of the main channel of RNAP, providing time for CTP to be incorporated at the 3′ end of RNA and for RNAP to switch the mode of RNA synthesis from the reiterative to canonical transcription. Maintaining the three-base DNA/RNA hybrid length in the pyrG RTC is critical to the regulation of pyrG gene expression depending on the CTP availability. In the ITR, not only a run of three but also a run of four or five G residues permits reiterative transcription; however, these extra Gs in the ITR result in less than optimum regulation of pyrG expression under CTP limited conditions. A run of five or more G residues suppresses RNA slippage due to suppression of the DNA/RNA hybrid melting (33).

The mechanism of RNA extension observed for the pyrG promoter will not hold for other promoters engaged in reiterative transcription, such as pyrBI (5′-AATTTG; transcription start site is underlined and slippage-prone sequence is italicized) (7), codBA (5′-ATTTTTTG) (34) and upp-uraA (5′-GATTTTTTTTG) (35) in E. coli, because these promoters produce 5–10 bases of RNA before slipping and synthesize much longer stretches of reiterative RNAs (30 nucleotides or longer) (Supplementary Figure S8). Furthermore, once reiterative transcription starts from these promoters, RNA synthesis does not switch to canonical transcription (Supplementary Figure S2). The mechanism of reiterative transcription from these promoters might be similar to pyrG promoter variants containing −1T or −1C as investigated in this study (Figures 4 and 5); these variants produce much longer reiterative RNA relative to the wild-type pyrG promoter. This hypothesis is consistent with our structural observation that the crystal containing the pyrBI promoter in the presence of ATP and UTP substrates formed 4-mer RNA (5′-AAUU-3′) and its 5′ end collides with the σ finger (Figure 6). Investigating how the pyrBI-type RTC accommodates a long stretch of reiterative RNA cannot be addressed by in crystallo transcription and X-ray crystallography structure determination because σ release is not permitted in the RNAP crystals. Elucidating the structural basis of pyrBI-type reiterative transcription could be achieved by determining the structure of RTC by cryo-electron microscopy, a powerful method to determine high-resolution macromolecular structures in solution (36).

DATA AVAILABILITY

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structures have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 6OY5, 6OY6, 6OY7, 6OVR, 6OVY, 6OW3, 6P70 and 6P71.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the staff at the MacCHESS for support of crystallographic data collection. We thank Dr. Steve Benkovic for using the stopped-flow equipment in his group. We thank Dr. Charles L. Turnbough, Jr, Catherine Sutherland and Shoko Murakami for critically reading the manuscript. We thank Dr. Vadim Molodtsov for preparing Figure 7 and discussion.

Author contributions: Y.S., M.H. and K.S.M. contributed to the design of the experiments. Y.S. crystallized the RTCs and collected the X-ray diffraction data. Y.S. and K.S.M. determined X-ray crystal structures. Y.S. developed and conducted the in vitro transcription and 2-AP fluorescence assays. Y.S. and M.H. developed and conducted the stopped-flow experiment. All authors participated in the interpretation of the results and in writing the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health [GM087350, GM131860 to K.S.M.]. Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Turnbough C.L. Jr, Switzer R.L.. Regulation of pyrimidine biosynthetic gene expression in bacteria: repression without repressors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008; 72:266–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turnbough C.L. Regulation of gene expression by reiterative transcription. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011; 14:142–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chamberlin M., Berg P.. Deoxyribonucleic acid-directed synthesis of ribonucleic acid by an enzyme from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1962; 48:81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jacques J.P., Kolakofsky D.. Pseudo-templated transcription in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. Genes Dev. 1991; 5:707–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anikin M., Molodtsov V., Temiakov D., McAllister W.T.. Atkins JF, Gesteland RF. Transcript slippage and recoding. Recoding: Expansion of Decoding Rules Enriches Gene Expression. 2010; NY: Springer; 409–432. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meng Q., Turnbough C.L., Switzer R.L.. Attenuation control of pyrG expression in Bacillus subtilis is mediated by CTP-sensitive reiterative transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004; 101:10943–10948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu C., Heath L.S., Turnbough C.L. Jr. Regulation of pyrBI operon expression in Escherichia coli by UTP-sensitive reiterative RNA synthesis during transcriptional initiation. Genes Dev. 1994; 8:2904–2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barr J.N., Wertz G.W.. Polymerase slippage at vesicular stomatitis virus gene junctions to generate poly(A) is regulated by the upstream 3′-AUAC-5′ tetranucleotide: implications for the mechanism of transcription termination. J. Virol. 2001; 75:6901–6913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng Y., Dylla S.M., Turnbough C.L. Jr. A long T·A tract in the upp initially transcribed region is required for regulation of upp expression by UTP-dependent reiterative transcription in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2001; 183:221–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guo H.C., Roberts J.W.. Heterogeneous initiation due to slippage at the bacteriophage 82 late gene promoter in vitro. Biochemistry. 1990; 29:10702–10709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Molodtsov V., Anikin M., McAllister W.T.. The presence of an RNA:DNA hybrid that is prone to slippage promotes termination by T7 RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 2014; 426:3095–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Raabe M., Linton M.F., Young S.G.. Long runs of adenines and human mutations. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998; 76:101–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Leeuwen F.W., de Kleijn D.P., van den Hurk H.H., Neubauer A., Sonnemans M.A., Sluijs J.A., Koycu S., Ramdjielal R.D., Salehi A., Martens G.J et al.. Frameshift mutants of beta amyloid precursor protein and ubiquitin-B in Alzheimer's and Down patients. Science. 1998; 279:242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wagner L.A., Weiss R.B., Driscoll R., Dunn D.S., Gesteland R.F.. Transcriptional slippage occurs during elongation at runs of adenine or thymine in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990; 18:3529–3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xiong X.F., Reznikoff W.S.. Transcriptional slippage during the transcription initiation process at a mutant lac promoter in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 1993; 231:569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou Y.N., Lubkowska L., Hui M., Court C., Chen S., Court D.L., Strathern J., Jin D.J., Kashlev M.. Isolation and characterization of RNA polymerase rpoB mutations that alter transcription slippage during elongation in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2013; 288:2700–2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sarafianos S.G., Das K., Tantillo C., Clark A.D. Jr, Ding J., Whitcomb J.M., Boyer P.L., Hughes S.H., Arnold E.. Crystal structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in complex with a polypurine tract RNA:DNA. EMBO J. 2001; 20:1449–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murakami K.S., Shin Y., Turnbough C1, Molodtsov V.. X-ray crystal structure of a reiterative transcription complex reveals an atypical RNA extension pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017; 114:8211–8216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Basu R.S., Warner B.A., Molodtsov V., Pupov D., Esyunina D., Fernandez-Tornero C., Kulbachinskiy A., Murakami K.S.. Structural basis of transcription initiation by bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2014; 289:24549–24559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mechold U., Potrykus K., Murphy H., Murakami K.S., Cashel M.. Differential regulation by ppGpp versus pppGpp in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:6175–6189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Otwinowski Z., Minor W.. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997; 276:307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Afonine P.V., Mustyakimov M., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Moriarty N.W., Langan P., Adams P.D.. Joint X-ray and neutron refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010; 66:1153–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emsley P., Cowtan K.. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2004; 60:2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Basu R.S., Murakami K.S.. Watching the bacteriophage N4 RNA polymerase transcription by time-dependent soak–trigger–freeze X-ray crystallography. J. Biol. Chem. 2013; 288:3305–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saenger W., Suck D.. The relationship between hydrogen bonding and base stacking in crystalline 4-thiouridine derivatives. Eur. J. Biochem. 1973; 32:473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Voet D., Rich A.. The crystal structures of purines, pyrimidines and their intermolecular complexes. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1970; 10:183–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saenger W. Neidle S. Principles of Nucleic Acid Structure. 1984; NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sowers L.C., Fazakerley G.V., Eritja R., Kaplan B.E., Goodman M.F.. Base pairing and mutagenesis: observation of a protonated base pair between 2-aminopurine and cytosine in an oligonucleotide by proton NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986; 83:5434–5438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guest C.R., Hochstrasser R.A., Sowers L.C., Millar D.P.. Dynamics of mismatched base pairs in DNA. Biochemistry. 1991; 30:3271–3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raney K.D., Sowers L.C., Millar D.P., Benkovic S.J.. A fluorescence-based assay for monitoring helicase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994; 91:6644–6648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Malinen A.M., Turtola M., Parthiban M., Vainonen L., Johnson M.S., Belogurov G.A.. Active site opening and closure control translocation of multisubunit RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:7442–7451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sullivan J.J., Bjornson K.P., Sowers L.C., deHaseth P.L.. Spectroscopic determination of open complex formation at promoters for Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 1997; 36:8005–8012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elsholz A.K.W., Jørgensen C.M., Switzer R.L.. The number of G residues in the Bacillus subtilispyrG initially transcribed region governs reiterative transcription-mediated regulation. J. Bacteriol. 2007; 189:2176–2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qi F., Turnbough C.L. Jr. Regulation of codBA operon expression in Escherichia coli by UTP-dependent reiterative transcription and UTP-sensitive transcriptional start site switching. J. Mol. Biol. 1995; 254:552–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tu A.H., Turnbough C.L. Jr. Regulation of upp expression in Escherichia coli by UTP-sensitive selection of transcriptional start sites coupled with UTP-dependent reiterative transcription. J. Bacteriol. 1997; 179:6665–6673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kuhlbrandt W. Biochemistry. The resolution revolution. Science. 2014; 343:1443–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structures have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 6OY5, 6OY6, 6OY7, 6OVR, 6OVY, 6OW3, 6P70 and 6P71.