Abstract

Pulmonary carcinoid tumors, including typical and atypical carcinoids, are well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) that represent 1–2% of all lung cancer cases. In the present study, all cases of well-differentiated NETs diagnosed at Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (Tianjin, China) between 2006 and 2016 were reviewed, and 20 pulmonary carcinoid cases were identified. The clinical features of these cases were summarized, and the results of pathological and imaging examinations were collated. As a low-grade malignant pulmonary neoplasm, the molecular biological mechanism of pulmonary carcinoids is yet to be elucidated. To investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms behind pulmonary carcinoids and to determine an effective molecular targeted therapeutic strategy, next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed using tissue samples from six patients to determine additional molecular biological characteristics that may help guide targeted therapy. A total of 27 somatic mutations in 21 genes were detected. Of note, mutations in the KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase, Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4, MET proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase and insulin-like growth factor 1 genes occurred in two out of six cases. Since treatments for advanced carcinoids are relatively ineffective, molecular profiling may contribute to the identification of novel treatments. In addition, the literature on mutations in pulmonary carcinoids was reviewed and available clinical information and features of this tumor type were summarized.

Keywords: carcinoid tumors, characteristics, next-generation sequencing

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a subtype of neoplasms that can arise in the majority of organs and share a number of common biochemical and pathologic features (1). Pulmonary NETs comprise 20–30% of all NETs (2), and NETs in the lung can be divided into four subtypes according to their malignancy grade: Typical carcinoids (TCs), atypical carcinoids (ACs), large-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (LCNECs) and small-cell lung cancers (SCLCs). Of these subtypes, typical and atypical carcinoids are generally termed pulmonary carcinoids and constitute 1–2% of all pulmonary malignancies; however, their incidence has notably increased in recent decades; Petursdottir et al (3) reported that the incidence of PC increased from 1.9/1,000,000 (1955–1964) to 5.8/1,000,000 (2005–2015) per year in Iceland (4). Complete surgical resection is the primary choice of treatment for early-stage lung carcinoids (2). However, efficient management strategies for advanced-stage lung carcinoids are limited (2). As the development of precision medicine has progressed, molecular targeted therapy has achieved breakthroughs for the treatment of pulmonary carcinoids, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, bevacizumab and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (5–7). The present study aimed to analyze the clinicopathological characteristics of patients admitted to Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (Tianjin, China) center who underwent surgical resection for pulmonary carcinoids, and gene mutation profiling was performed to explore the underlying molecular mechanisms. In addition, gene mutation information of pulmonary carcinoids was summarized from relevant literature.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

The present study was conducted in accordance with the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research involving human subjects. All subjects provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the clinical research ethical review board at Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (Tianjin, China).

Study design

Patient data were reviewed between January 2006 and December 2016 at Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, and information on 20 patients with lung carcinoid tumors with complete medical records was collected. The clinical features and imaging data from patient records were summarized. All pulmonary carcinoid cases were reviewed according to the World Health Organization criteria (2015) and were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual (8th edition) criteria (8,9). Carcinoid tumors of the lung were classified as typical carcinoids (TCs) or atypical carcinoids (ACs) based on the following histological differences: The number of mitoses per 10 high-power fields (TC mitotic index, <2; AC mitotic index, 2–10; SCLC/LCNECs mitotic indices, >10) (10); the presence of necrosis; increased cellularity with disorganization; nuclear pleomorphism; hyperchromatism; and an abnormal nuclear: Cytoplasmic ratio (11,12). In general, macroscopic pulmonary carcinoid tissues appeared as smooth, highly vascular, gray-yellow and notably demarcated masses (1,9,13,14). The diagnosis of pulmonary carcinoid can be established by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of a histopathologic section. However, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining is more precise for the diagnosis of pulmonary carcinoids compared with HE; specifically, staining for synaptophysin, chromogranin A and neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) can distinguish high-grade NETs (LCNECs and SCLCs) from pulmonary carcinoids (15).

Tissue sections (5 µm thick) were prepared from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks using formalin (10% methanol) solution as a fixative. The sections were stained using hematoxylin for 5 min and eosin (HE) for 1 min at room temperature.

Immunohistochemistry

Stainings for chromogranin A (CgA), synaptophysin (Syn), CD56, thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), P63, S-100, CK7 and Ki67 were performed by immunohistochemistry for six carcinoid tumors. The tumor tissue samples were fixed in formalin solution (10% methanol) for 48 h at room temperature. The tissues were dehydrated in xylene and graded ethanol series. After being immersed into paraffin wax twice at 60°C and embedded into paraffin blocks, the tumor tissues were cut into 5 µm thick sections. Tissues were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in a graded ethanol series. Microwave pretreatment in 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 10.0) for 15 min was performed to facilitate heat-induced antigen retrieval. After being rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), the sections were incubated with primary antibodies against CgA (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:100; cat. no. sc-393941), Syn (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:100; cat. no. sc-17750), CD56 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:50; cat. no. sc-7326), TTF-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:100; cat. no. sc-53136), P63 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:50; cat. no. sc-25268), S-100 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:100; cat. no. sc-53438), CK7 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.; 1:200; cat. no. M7018) and Ki67 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:100; cat. no. sc-23900) at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, samples were incubated with a secondary antibody mouse IgGκ light chain binding protein (m-IgGκ BP) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:50; cat. no. sc-516102) for 30 min at room temperature. Diaminobenzidine was used for visualization and followed by hematoxylin for counterstaining at room temperature for 1 min. A light microscope was used to evaluate the staining results at ×100 magnification. All staining slides were evaluated by two researchers to evaluate samples individually.

Next-generation sequencing

The DNA of 20 lung carcinoid tumors was extracted using QIAamp DNA FFPE tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and evaluated, and via quality control (according to the extent of DNA degradation), six cases were selected for sequencing. Targeted capture sequencing of 56 cancer-associated genes was performed in 6 pulmonary carcinoid tumors (Lung core TM 56 genes; Burning Rock Biotech; Table SI).

The concentration of the DNA samples was measured using the Qubit dsDNA assay (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to ensure that the content of genomic DNA was ≥100 ng. The volume was adjusted to a total of 100 µl using 1X Tris-low EDTA buffer, and the solution was transferred to a Covaris microtube for fragmentation using Covaris M220 (Covaris, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The DNA was fragmented (average DNA fragment size, 180–220 bp), which was followed by hybridization with the capture probe baits, hybrid selection with magnetic beads and PCR amplification. A high-sensitivity DNA assay was then used to assess the quality and size range. Available indexed samples were sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina, Inc.) bioanalyzer with pair-end reads.

Raw data from the NextSeq 500 runs were processed with Flexbar software (version 2.7.0) to generate clean FASTQ data, trim adapter sequences and filter and remove poor-quality reads (16). The depth for the sequencing in the present study was ~1,000 and Varscan (v. 2.3) was used to call single nucleotide variations and insertions/deletions with MAPQ >60, base quality >30 and allele frequency (AF) >1% (17). The variants that comprised >3 non-duplicated paired reads or >5 non-duplicated reads were considered as true mutations. Subsequently, clean FASTQ data were aligned to the hg19 (GRCH37) assembly using BWA-sample (Burrows Wheeler Aligner software; version 0.7.12-r1039; http://sourceforge.net/projects/bio-bwa/files/), and PCR duplicates were removed using the Mark Duplicates tool in Picard Tools (version 1.124, http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). All variants were annotated using ANNOVAR (version 20160201) (18). Finally, variation frequency (>0.5%) was used to eliminate erroneous base calling and to generate final mutations, and manual verification was performed using Integrative Genomics Viewer version 2.3.72 (19–21).

Statistical analysis

Clinicopathological characteristics of the patients with TC and AC were compared using the unpaired Student's t-test (for mean age and tumor diameter), Kruskal-Wallis test [pathological N and Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging] and χ2 test (all other characteristics). A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 software (IBM Corp.).

Results

Clinical features of the study cohort

The clinicopathological characteristics of 20 patients who underwent surgical resection for pulmonary carcinoid tumors at Tianjin Medical University General Hospital were reviewed and summarized (Table I). Generally, atypical carcinoids are less frequent and the ratio of TCs to ACs is 8–10:1 (4,22); however, of the 20 included cases, 9 were typical carcinoid tumors and 11 were atypical carcinoid tumors. The underlying reasons for this discrepancy are not clear. There was a male predominance in the included population (male:female, 15:5) and the age of patients ranged from 14–71 years with a median age of 48 years. None of the patients with TC tumors presented with lymphatic metastasis, whereas 5/11 (45.45%) patients with AC tumors had lymphatic metastasis, including three cases of N1 and two cases of N2 metastasis. The P-value of the Kruskal-Wallis test was 0.024, which indicated that ACs exhibited a higher malignancy stage. Other clinical characteristics, including the surgical approach, surgical procedure, prescribed adjuvant therapy, tumor sites and TNM stage were considered and compared between TC and AC, and no significant differences were observed (Table I).

Table I.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with pulmonary carcinoid who underwent surgical resection at Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (Tianjin, China).

| Total pulmonary carcinoid tumors (n=20) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Typical carcinoids (n=9) | Atypical carcinoids (n=11) | P-value |

| Median age (range), years | 48 (28–66) | 49 (14–71) | 0.396 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.069 | ||

| Male | 5 (55.6) | 10 (90.9) | |

| Female | 4 (44.4) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 0.653 | ||

| Never | 5 (55.6) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Current/former | 4 (44.4) | 6 (54.5) | |

| History of malignancy, n (%) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (36.4) | 0.888 |

| Median tumor diameter (range), cm | 4 (1.5–9.1) | 5.5 (2.1–12.5) | 0.252 |

| Incidence of PET evaluation, n (%) | 4 (44.4) | 3 (27.3) | 0.423 |

| Pathological N stage, n (%) | 0.024 | ||

| N0 | 9 (100) | 6 (54.5) | |

| N1 | 0 (0) | 3 (27.3) | |

| N2 | 0 (0) | 2 (18.2) | |

| TNM stage, n (%) | 0.872 | ||

| I | 4 (44.4) | 5 (45.5) | |

| II | 2 (22.2) | 3 (27.3) | |

| III | 2 (22.2) | 2 (18.2) | |

| IV | 1 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Tumor site | 0.946 | ||

| Left upper lobe | 1 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Left lower lobe | 2 (22.2) | 3 (27.3) | |

| Left hilum | 1 (11.1) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Right upper lobe | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Right middle lobe | 1 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Right lower lobe | 2 (22.2) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Right hilum | 1 (11.1) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Surgical approach, n (%) | 0.492 | ||

| VATS | 7 (77.8) | 7 (63.6) | |

| Thoracotomy | 2 (22.2) | 4 (36.4) | |

| Procedure, n (%) | 0.493 | ||

| Wedge | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Segmentectomy | 2 (22.2) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Lobectomy | 6 (66.7) | 9 (81.8) | |

| Adjuvant therapy, n (%) | 0.659 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 2 (22.2) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Radiotherapy | 1 (11.1) | 2 (18.2) | |

PET, positron emission tomography; VATs, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; patients were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual (8th edition) criteria.

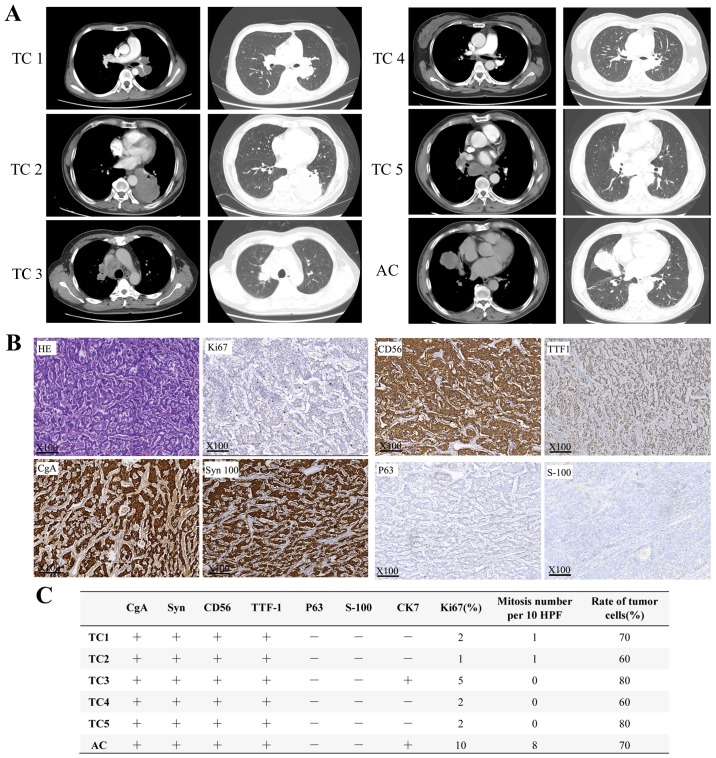

Computed tomography images of six patients whose samples were submitted for NGS analysis are presented in Fig. 1A. The imaging features of pulmonary carcinoids are often similar to those of other lung cancers and have few defining characteristics. The majority of carcinoids appear as round or ovoid peripheral lung nodules with smooth or lobular margins (23) and generally exhibit marked enhancement in enhanced CT due to their high vascularity (24). Representative images of HE and IHC staining are presented in Fig. 1B. The specific markers of the six carcinoid tumors were also summarized in Fig. 1C. The present analysis revealed that ACs exhibited a higher percentage of antigen Ki-67-positive cells and more mitoses per 10 high-power fields; and considering the diagnostic criteria of AC vs. TC, this result was logical and expected.

Figure 1.

Radiological and pathological results of six patients with pulmonary carcinoids. (A) Computed tomography imaging of six patients with pulmonary carcinoid. (B) Representative HE and IHC images of pulmonary carcinoids under light microscope at ×100 magnification. (C) IHC results of 6 patients with pulmonary carcinoids. IHC, immunohistochemistry; HE, hematoxylin and eosin; TC, typical carcinoid; AC, atypical carcinoid.

Gene mutation analysis of lung carcinoid tumors

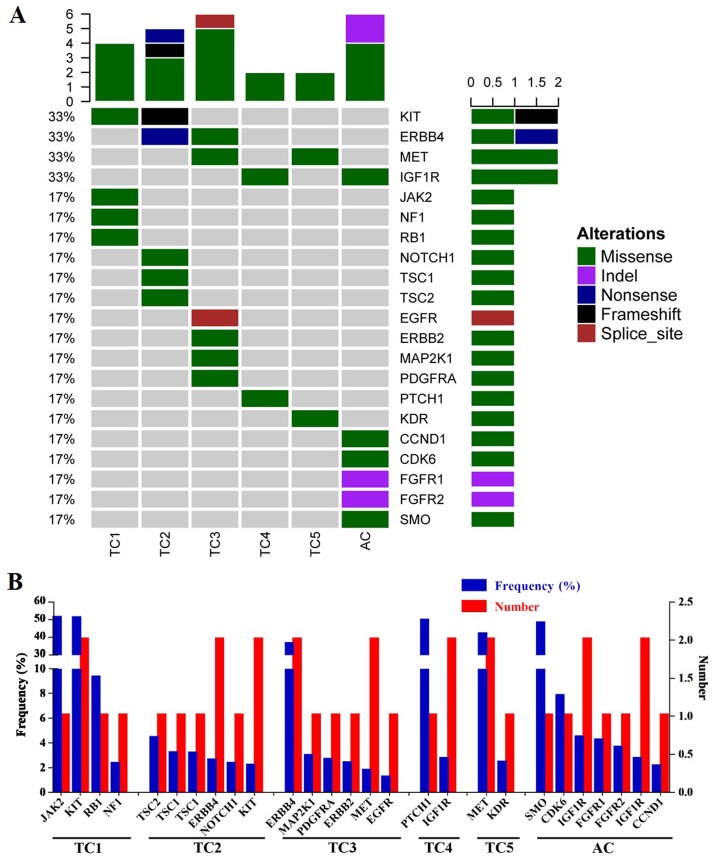

The results of NGS are presented in Table II and Fig. 2. Following the gene mutation profiling of six pulmonary carcinoid tumors, a total of 27 mutations in 21 genes were identified, including JAK2, KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT), RB transcriptional coexpressor 1 (Rb), neurofibromin 1, TSC complex subunit 1 (TSC1), TSC2, Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4 (ERBB4), NOTCH1, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1, platelet-derived growth factor receptor α, ERBB2, MET proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (MET), EGFR, patched 1, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), kinase insert domain receptor, smoothened frizzled class receptor, CDK6, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), FGFR2 and CDK4. Of these, 11 were proto-oncogenes and 6 were tumor suppressor genes, which indicated that they may participate in tumorigenesis, tumor growth, invasion and metastasis.

Table II.

Gene mutations of patients with pulmonary carcinoids from our cohort.

| Case | Histology | Gene | AA change | Mutation type | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TC | JAK2 | K1030R | Missense variant | 50.60 |

| KIT | A755T | Missense variant | 50.40 | ||

| RB1 | F198L | Missense variant | 9.23 | ||

| NF1 | S1100T | Missense variant | 2.24 | ||

| 2 | TC | TSC2 | R57H | Missense variant | 4.33 |

| TSC1 | S1038R | Missense variant | 3.12 | ||

| TSC1 | S1039G | Missense variant | 3.08 | ||

| ERBB4 | R1155a | Nonsense variant | 2.51 | ||

| NOTCH1 | E242K | Missense variant | 2.26 | ||

| KIT | P37S? | Frameshift variant | 2.09 | ||

| 3 | TC | ERBB4 | I944V | Missense variant | 35.80 |

| MAP2K1 | D67N | Missense variant | 2.89 | ||

| PDGFRA | R293H | Missense variant | 2.56 | ||

| ERBB2 | R47H | Missense variant | 2.29 | ||

| MET | R988C | Missense variant | 1.68 | ||

| EGFR | NA | Splice donor variant | 1.15 | ||

| 4 | TC | PTCH1 | K251T | Missense variant | 49.00 |

| IGF1R | G8R | Missense variant | 2.65 | ||

| 5 | TC | MET | V1088M | Missense variant | 41.30 |

| KDR | A532V | Missense variant | 2.35 | ||

| 6 | AC | SMO | P743T | Missense variant | 47.50 |

| CDK6 | I159K | Missense variant | 7.72 | ||

| IGF1R | P1290L | Missense variant | 4.38 | ||

| FGFR1 | DDDD163D | Deletion variant | 4.15 | ||

| FGFR2 | L192 | Deletion variant | 3.56 | ||

| IGF1R | S1180F | Missense variant | 2.63 | ||

| CDK4 | V281E | Missense variant | 2.06 |

TC, typical carcinoid; AC, atypical carcinoid; AA, amino acid

termination codon which signals the end of translation.

Figure 2.

Gene mutation analysis results of size patients with pulmonary carcinoid. (A) Heat map of pulmonary carcinoids mutational analysis. (B) Frequency and distribution of gene mutations in six carcinoids. TC, typical carcinoid; AC, atypical carcinoid.

The majority of the identified mutations were missense mutations (81.48%), followed by deletion mutations (7.4%) and one case each of nonsense, frameshift and splice donor mutations (Fig. 2A). All carcinoids had multiple mutated genes, and two patients (33.3%) had multiple mutations in a single gene, including the TSC1 and IGF1R genes (Fig. 2B). The KIT, ERBB4, MET and IGF1R genes were mutated in two patients (33.3%). These four genes were considered to be mutated at a high frequency (Fig. 2A) and were followed (in order of frequency) by 17 other genes that were each mutated in only one case (16.73% of cases) (Fig. 2A).

Two KIT mutations were identified on chromosome 4, but on different exons: Case 1 presented with a missense mutation (G>A mutation in exon 16; AF 50.4%), whereas case 2 presented with a frameshift mutation (A>AT mutation in exon 2; AF 2.09%) (Table II). Two ERBB4 mutations were revealed on chromosome 2. Case 2 harbored a nonsense G>A mutation in exon 27, whereas case 3 had a missense T>C mutation in exon 23, resulting in a 35.8% mutation frequency (Table II). The two MET mutations were both missense mutations on chromosome 7. Case 3 presented with a C>T base change in exon 14, whereas case 5 had a G>A base change in exon 15, yielding a 41.3% mutation frequency (Table II). A total of three IGF1R mutations were identified on chromosome 15 in two patients on different exons: Case 4 presented with a G>A mutation in exon 16, whereas case 6 presented with two C>T changes in exons 19 and 21.

Discussion

As pulmonary carcinoid is a tumor with a low malignancy rate, resection is often an effective treatment option for early disease; however, for patients with advanced unresectable pulmonary carcinoids, no standardized or authoritative postoperative adjuvant therapy scheme has been established (25,26). In recent years, as the development of precision medicine has progressed, targeted therapy has achieved significant breakthroughs for pulmonary carcinoids, an example of which is mTOR inhibitors (5–7). However, the progression of therapy in pulmonary carcinoids is still limited due to its low prevalence (26), and an in-depth understating of the underlying molecular mechanisms is necessary. Thus, large-scale clinical drug research targeted at pulmonary carcinoids should be proposed as soon as possible. Surgical resection is appropriate for localized diseases; these include locoregional pulmonary carcinoids, cases with limited sites of metastatic disease and local recurrent diseases, such as liver metastases (26).

Pulmonary carcinoids are low-grade malignant tumors, and their underlying molecular biological mechanism is yet to be fully elucidated. To understand previous results of pulmonary carcinoid gene sequencing, published literature (PubMed; January 2018) on mutations in pulmonary carcinoids was examined, and available clinical information was summarized in Table III, comprising 13 studies that referenced 61 cases, including 29 ACs, 31 TCs and 1 indeterminate carcinoid (22,27–38). The majority of the articles retrieved utilized first-generation sequencing technology to reveal mutations in single genes or chromosomes, including PI3K, p53TP53, Rb, menin 1, K-ras, c-Met, ELAV-like RNA-binding protein 4, 3p14 and 9p, and no significant associations were observed between specific gene mutations and cancer type, age or sex (22,27–38). A total of three studies (including 21 patients) reported NGS data for carcinoids. The mutations of KIT, ERBB4 and MET were also reported in these studies, which supported the findings of the present study (27–29). Notably, one study that used NGS to investigate carcinoids did not provide the original sequencing data and, consequently, the sequencing results were not summarized in Table III; however, it was reported in the study that FGFR1 was highly expressed in carcinoids (39). In addition, Rossi et al (40) also reported that ERBB4 alteration was detected in carcinoids. Recently, Asiedu et al (41) used mRNA expression, single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping and a combination of exome and whole-genome sequencing to detect genomic alterations in 31 TC and 11 AC tumors. Compared with the results of Asiedu et al (41), only a limited number of mutated genes were common to the genes identified using NGS in the present study. The differences between the current study and the previous studies may be attributable to the examination of different targeted gene panels and the different demographic of patients included. In the present study, four genes were revealed to be mutated at a high frequency, including KIT, ERBB4, MET and IGF1R, which were mutated in 33.3% patients. These genes encode typical tyrosine-protein kinases or receptor tyrosine kinases that are cell surface receptors for multiple signaling pathways and serve an essential role in the regulation of cell survival, proliferation and apoptosis (42–45). Mutations in these genes are important therapeutic targets of molecular targeted therapeutic drugs, such as the TKIs imatinib and sunitinib (42–45).

Table III.

Gene mutation analysis of pulmonary carcinoids from previously published literature.

| Case | Author | Year | Age | Sex | Type | Mutation | Gene/Chromosome | Country | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hiyama et al | 1993 | 77 | M | AC | point mutation Cys>Phe | p53 | Japan | (38) |

| Deletion mutation | Rb | ||||||||

| 2 | Lohmann et al | 1993 | 65 | F | TC | Neutral mutation Cys>Tyr | p53 | Germany | (22) |

| 3 | 68 | M | TC | Missense mutation Glu>Lys | p53 | ||||

| 4 | 72 | F | TC | Missense mutation Val>Met | p53 | ||||

| 5 | Debelenko et al | 1997 | 46 | NA | TC | Frameshift mutation 1650insC | MEN1 | USA | (37) |

| 6 | 56 | NA | TC | Alteration of splicing, frameshift mutation 764+3A>G | MEN1 | ||||

| 7 | 63 | NA | TC | Frameshift mutation 134del13 (GACGCTGTTCCCG) | MEN1 | ||||

| 8 | 49 | NA | TC | Frameshift mutation 1699delA and 1702G>C | MEN1 | ||||

| 9 | Sagawa et al | 1998 | NA | NA | AC | point mutation | K-ras | USA | (36) |

| 10 | Couce et al | 52 | F | AC | K-ras c12 Gly>Ser missense mutation | K-ras | USA | (35) | |

| 11 | 39 | F | AC | K-ras c12 Gly>Asp missense mutation | K-ras | ||||

| 12 | 61 | F | AC | Exon 8 c298 Glu>Stop missense mutation | p53 | ||||

| 13 | Sugio et al | 2003 | NA | NA | AC | Loss of heterozygosity in 3p14 | 3p14 | Japan | (34) |

| 14 | NA | NA | AC | Loss of heterozygosity in 9p | 9p | ||||

| 15 | Snabboon et al | 2005 | 68 | F | TC | Deletion mutation at exon 10 (1793delG) | MEN1 | Thailand | (33) |

| 16 | D'Alessandro et al | 2010 | 29 | F | TC | Exon 5 c.733-16C>T | ELAVL4 | Italy | (32) |

| 17 | 50 | M | TC | Exon 5 c.666A>T | ELAVL4 | ||||

| Exon 5 c.712C>T | ELAVL4 | ||||||||

| 18 | 70 | F | TC | Somatic mutation Exon 4 c.424delA | ELAVL4 | ||||

| Exon 5 c.559G>A | ELAVL4 | ||||||||

| 19 | 47 | M | AC | Exon 4 c.387C>T | ELAVL4 | ||||

| Single nucleotide polymorphism | ELAVL4 | ||||||||

| Exon 5 c.687T>C | |||||||||

| c.1367+56C>T 3′UTR | ELAVL5 | ||||||||

| 20 | 54 | M | AC | Somatic mutation Exon 5 | ELAVL4 | ||||

| c.655C>T | |||||||||

| Exon 5 c.704G>A | ELAVL4 | ||||||||

| 21 | Capodanno et al | 2012 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.1576 A>G | PI3K | Italy | (31) |

| 22 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.1639 G>A | PI3K | ||||

| 23 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.1639 G>A | PI3K | ||||

| 24 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.1639 G>A | PI3K | ||||

| 25 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.1639 G>A | PI3K | ||||

| 26 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.2993 T>C | PI3K | ||||

| 27 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3007 T>C | PI3K | ||||

| 28 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3017 T>C | PI3K | ||||

| 29 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3022 T>C | PI3K | ||||

| 30 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.3034 G>A | PI3K | ||||

| 31 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3041 A>G | PI3K | ||||

| 32 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3050 A>T | PI3K | ||||

| 33 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3062 A>G | PI3K | ||||

| 34 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.3061 T>A | PI3K | ||||

| 35 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3068 G>A | PI3K | ||||

| 36 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.3133 G>A | PI3K | ||||

| 37 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.3145 G>A | PI3K | ||||

| 38 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.3145 G>A | PI3K | ||||

| 39 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3155 C>T | PI3K | ||||

| 40 | Voortman et al | 2013 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation Exon 14 T1010I mutation | c-Met | USA | (30) |

| 41 | Armengol et al | 2015 | 69 | Male | TC | Missense mutation c.1796C>T | BRAF | Finland | (29) |

| Missense mutation c.1496G>A | SMAD4 | ||||||||

| Missense mutation c.3074C>T | SMAD4 | ||||||||

| Missense mutation c.38G>A | KRAS | ||||||||

| 42 | Vollbrecht et al | 2015 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.311T>A | EGFR | Germany | (28) |

| Missense mutation c.311T>A | EGFR | ||||||||

| Insertion mutation c.2516_2517insC | GNAS | ||||||||

| Deletion mutation c.1912delA | KIT | ||||||||

| Missense mutation c.1015C>T | PTEN | ||||||||

| 43 | NA | NA | AC | Deletion and insertion mutation | KDR | ||||

| c.1416_1417delinsTA | |||||||||

| 44 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.2744C>A | ERBB4 | ||||

| 45 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3788G>A | APC | ||||

| Insertion mutation c.855_856insG | FGFR1 | ||||||||

| Insertion mutation c.3730_3731insC | MET | ||||||||

| 46 | NA | NA | AC | Deletion and insertion mutation | RET | ||||

| c.2712_2713delinsGG | |||||||||

| 47 | NA | NA | AC | Deletion and insertion mutation | ERBB2 | ||||

| c.2354_2355delinsGG | |||||||||

| 48 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.3367C>T | APC | ||||

| Missense mutation c.112G>A | KRAS | ||||||||

| 49 | NA | NA | AC | Deletion mutation c.862delG | HNF1A | ||||

| 50 | NA | NA | AC | Missense mutation c.2602C>T | ERBB2 | ||||

| Missense mutation c.1100T>G | SMO | ||||||||

| 51 | NA | NA | AC | Deletion and insertion mutation | KIT | ||||

| c.1637_1638delinsGG | |||||||||

| Missense mutation c.274C>T | PI3K | ||||||||

| Missense mutation c.167C>T | SMARCB1 | ||||||||

| 52 | NA | NA | AC | Insertion mutation c.3730_3731insC | MET | ||||

| 53 | NA | NA | TC | Deletion and insertion mutation | RET | ||||

| c.2711_2713delinsTGG | |||||||||

| 54 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.3386T>C | APC | ||||

| 55 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.2624C>T | ERBB2 | ||||

| 56 | NA | NA | TC | Deletion and insertion mutation | ERBB2 | ||||

| c.2354_2355delinsGG | |||||||||

| 57 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.2531G>A | GNAS | ||||

| 58 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.2318A>C | EGFR | ||||

| Missense mutation c.274T>A | IDH1 | ||||||||

| Missense mutation c.267A>C | IDH1 | ||||||||

| 59 | NA | NA | TC | Deletion and insertion mutation | PDGFRA | ||||

| c.2471_2472delinsCT | |||||||||

| 60 | NA | NA | TC | Missense mutation c.920C>T | ABL1 | ||||

| Missense mutation c.505C>T | SMAD4 | ||||||||

| 61 | Lou et al | 2017 | 23 | Male | NA | NA | PI3K | China | (27) |

NA, not available; Rb, RB transcriptional corepressor 1; MEN1, menin 1; ELAV4, ELAV-like RNA-binding protein 4; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, putative; NA, not applicable.

Although certain high-frequency gene mutations were identified, it is difficult to confirm whether the alteration of these genes may initiate and promote pulmonary carcinoid tumors and be effective against targeted therapy. In the future, systematic gene mutation profiling should be performed with a large number of samples to detect potential tumor-promoting genes and to identify potential novel treatment targets for pulmonary carcinoids. This profiling may have important therapeutic implications for the treatment of patients with pulmonary carcinoids.

There are certain limitations the present study; only 6 PCs were collected and this is too few to predict more precise and comprehensive molecular principles of PCs and to conduct survival analysis.

In conclusion, IGF1R, ERBB4, KIT and MET were identified as frequently mutated genes that may influence the tumorigenesis of pulmonary carcinoid tumors; therefore, targeted therapy against these genes may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of this rare disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Shannon Chuai, Dr Zhou Zhang and Dr Junyi Ye (Burning Rock Dx, Guangzhou, China) for their technical support and Dr Dongbo Xu (Department of Pathology, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, China) for her assistance in the pathological evaluation.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81772464), the Tianjin Key Project of Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 17JCZDJC36200), the Tianjin Science and Technology Plan Project (grant no. 19ZXDBSY00060), the Science & Technology Foundation for Selected overseas Chinese scholar Ministry of personnel of China, the Science & Technology Foundation for Selected overseas Chinese scholar Bureau of personnel of China Tianjin and the Tianjin Medical University General Hospital Young Incubation Foundation (grant no. ZYYFY2017040).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

SX and JC conceived and designed the study. ZS, SW, GC and JC performed surgery. XL, YLH, TS and DR reviewed the patient electronic medical record for patients with pulmonary carcinoid. XL, YLH, TS and YH performed the genetic analysis. XL and YH performed the literature review and wrote the manuscript. SX and JC reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University (Tianjin, China). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients with pulmonary carcinoid for blood sampling and tissue sequencing.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

YH is affiliated with Burning Rock Biotech, who performed targeted capture sequencing of cancer-associated genes. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Coppola D, Lloyd RV, Suster S. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: A review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems. Pancreas. 2010;39:707–712. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ec124e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pusceddu S, Lo Russo G, Macerelli M, Proto C, Vitali M, Signorelli D, Ganzinelli M, Scanagatta P, Duranti L, Trama A, et al. Diagnosis and management of typical and atypical lung carcinoids. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;100:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petursdottir A, Sigurdardottir J, Fridriksson BM, Johnsen A, Isaksson HJ, Hardardottir H, Jonsson S, Gudbjartsson T. Pulmonary carcinoid tumours: Incidence, histology, and surgical outcome. A population-based study. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019 Nov 28; doi: 10.1007/s11748-019-01261-w. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertino EM, Confer PD, Colonna JE, Ross P, Otterson GA. Pulmonary neuroendocrine/carcinoid tumors: A review article. Cancer. 2009;115:4434–4441. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filosso PL, Ferolla P, Guerrera F, Ruffini E, Travis WD, Rossi G, Lausi PO, Oliaro A, European Society of Thoracic Surgeons Lung Neuroendocrine Tumors Working-Group Steering Committee Multidisciplinary management of advanced lung neuroendocrine tumors. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(Suppl 2):S163–S171. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.04.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oberg K, Hellman P, Ferolla P, Papotti M, ESMO Guidelines Working Group Neuroendocrine bronchial and thymic tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii120–vii123. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zatelli MC, Minoia M, Martini C, Tagliati F, Ambrosio MR, Schiavon M, Buratto M, Calabrese F, Gentilin E, Cavallesco G, et al. Everolimus as a new potential antiproliferative agent in aggressive human bronchial carcinoids. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:719–729. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Kim AW, Tanoue LT. The eighth edition lung cancer stage classification. Chest. 2017;151:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, Yatabe Y, Austin JHM, Beasley MB, Chirieac LR, Dacic S, Duhig E, Flieder DB, et al. The 2015 World Health organization classification of lung tumors: Impact of genetic, clinical and radiologic advances since the 2004 classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1243–1260. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swarts DR, Ramaekers FC, Speel EJ. Molecular and cellular biology of neuroendocrine lung tumors: Evidence for separate biological entities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826:255–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travis WD, Rush W, Flieder DB, Falk R, Fleming MV, Gal AA, Koss MN. Survival analysis of 200 pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors with clarification of criteria for atypical carcinoid and its separation from typical carcinoid. Am J surg Pathol. 1998;22:934–944. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arrigoni MG, Woolner LB, Bernatz PE. Atypical carcinoid tumors of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1972;64:413–421. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)39836-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travis WD. Pathology and diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors: Lung neuroendocrine. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horsch D, Schmid KW, Anlauf M, Darwiche K, Denecke T, Baum RP, Spitzweg C, Grohé C, Presselt N, Stremmel C, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the bronchopulmonary system (typical and atypical carcinoid tumors): Current strategies in diagnosis and treatment. Conclusions of an expert meeting February 2011 in Weimar, Germany. Oncol Res Treat. 2014;37:266–276. doi: 10.1159/000362430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelosi G, Rindi G, Travis WD, Papotti M. Ki-67 antigen in lung neuroendocrine tumors: Unraveling a role in clinical practice. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:273–284. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodt M, Roehr JT, Ahmed R, Dieterich C. FLEXBAR-flexible barcode and adapter processing for next-generation sequencing platforms. Biology (Basel) 2012;1:895–905. doi: 10.3390/biology1030895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. VarScan 2: Somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Wenger AM, Zehir A, Mesirov JP. Variant review with the integrative genomics viewer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e31–e34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): High-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohmann DR, Fesseler B, Pütz B, Reich U, Böhm J, Präuer H, Wünsch PH, Höfler H. Infrequent mutations of the p53 gene in pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5797–5801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meisinger QC, Klein JS, Butnor KJ, Gentchos G, Leavitt BJ. CT features of peripheral pulmonary carcinoid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:1073–1080. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schrevens L, Vansteenkiste J, Deneffe G, De Leyn P, Verbeken E, Vandenberghe T, Demedts M. Clinical-radiological presentation and outcome of surgically treated pulmonary carcinoid tumours: A long-term single institution experience. Lung Cancer. 2004;43:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pavel M, O'Toole D, Costa F, Capdevila J, Gross D, Kianmanesh R, Krenning E, Knigge U, Salazar R, Pape UF, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of distant metastatic disease of intestinal, pancreatic, bronchial neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN) and NEN of unknown primary site. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:172–185. doi: 10.1159/000443167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caplin ME, Baudin E, Ferolla P, Filosso P, Garcia-Yuste M, Lim E, Oberg K, Pelosi G, Perren A, Rossi RE, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors: European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society expert consensus and recommendations for best practice for typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1604–1620. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lou G, Yu X, Song Z. Molecular profiling and survival of completely resected primary pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinoma. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18:e197–e201. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vollbrecht C, Werner R, Walter RF, Christoph DC, Heukamp LC, Peifer M, Hirsch B, Burbat L, Mairinger T, Schmid KW, et al. Mutational analysis of pulmonary tumours with neuroendocrine features using targeted massive parallel sequencing: A comparison of a neglected tumour group. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:1704–1711. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armengol G, Sarhadi VK, Ronty M, Tikkanen M, Knuuttila A, Knuutila S. Driver gene mutations of non-small-cell lung cancer are rare in primary carcinoids of the lung: NGS study by ion Torrent. Lung. 2015;193:303–308. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9690-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voortman J, Harada T, Chang RP, Killian JK, Suuriniemi M, Smith WI, Meltzer PS, Lucchi M, Wang Y, Giaccone G. Detection and therapeutic implications of c-Met mutations in small cell lung cancer and neuroendocrine tumors. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:833–840. doi: 10.2174/1381612811306050833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Capodanno A, Boldrini L, Ali G, Pelliccioni S, Mussi A, Fontanini G. Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase α catalytic subunit gene somatic mutations in bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumours. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1559–1566. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Alessandro V, Muscarella LA, la Torre A, Bisceglia M, Parrella P, Scaramuzzi G, Storlazzi CT, Trombetta D, Kok K, De Cata A, et al. Molecular analysis of the HuD gene in neuroendocrine lung cancers. Lung Cancer. 2010;67:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snabboon T, Plengpanich W, Siriwong S, Wisedopas N, Suwanwalaikorn S, Khovidhunkit W, Shotelersuk V. A novel germline mutation, 1793delG, of the MEN1 gene underlying multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:280–282. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugio K, Osaki T, Oyama T, Takenoyama M, Hanagiri T, Morita M, Yamazaki K, Nagashima A, Nakahashi H, Maehara Y, Yasumoto K. Genetic alteration in carcinoid tumors of the lung. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;9:149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Couce ME, Bautista D, Costa J, Carter D. Analysis of K-ras, N-ras, H-ras, and p53 in lung neuroendocrine neoplasms. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1999;8:71–79. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sagawa M, Saito Y, Fujimura S, Linnoila RI. K-ras point mutation occurs in the early stage of carcinogenesis in lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:720–723. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Debelenko LV, Brambilla E, Agarwal SK, Swalwell JI, Kester MB, Lubensky IA, Zhuang Z, Guru SC, Manickam P, Olufemi SE, et al. Identification of MEN1 gene mutations in sporadic carcinoid tumors of the lung. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2285–2290. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.13.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiyama K, Hasegawa K, Ishioka S, Takahashi N, Yamakido M. An atypical carcinoid tumor of the lung with mutations in the p53 gene and the retinoblastoma gene. Chest. 1993;104:1606–1607. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.5.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walter RF, Vollbrecht C, Christoph D, Werner R, Schmeller J, Flom E, Trakada G, Rapti A, Adamidis V, Hohenforst-Schmidt W, et al. Massive parallel sequencing and digital gene expression analysis reveals potential mechanisms to overcome therapy resistance in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. J Cancer. 2016;7:2165–2172. doi: 10.7150/jca.16925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossi G, Bertero L, Marchiò C, Papotti M. Molecular alterations of neuroendocrine tumours of the lung. Histopathology. 2018;72:142–152. doi: 10.1111/his.13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asiedu MK, Thomas CF, Jr, Dong J, Schulte SC, Khadka P, Sun Z, Kosari F, Jen J, Molina J, Vasmatzis G, et al. Pathways impacted by genomic alterations in pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1691–1704. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maennling AE, Tur MK, Niebert M, Klockenbring T, Zeppernick F, Gattenlöhner S, Meinhold-Heerlein I, Hussain AF. Molecular targeting therapy against EGFR family in breast cancer: Progress and future potentials. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:E1826. doi: 10.3390/cancers11121826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chughtai S. The nuclear translocation of insulin-like growth factor receptor and its significance in cancer cell survival. Cell Biochem Funct. 2019 Dec 25; doi: 10.1002/cbf.3479. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salgia R. MET in lung cancer: Biomarker selection based on scientific rationale. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:555–565. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miettinen M, Lasota J. KIT (CD117): A review on expression in normal and neoplastic tissues, and mutations and their clinicopathologic correlation. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2005;13:205–220. doi: 10.1097/01.pai.0000173054.83414.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.