Abstract

Background

Reduced circulating estrogen levels around the time of the menopause can induce unacceptable symptoms that affect the health and well‐being of women. Hormone therapy (both unopposed estrogen and estrogen/progestogen combinations) is an effective treatment for these symptoms, but is associated with risk of harms. Guidelines recommend that hormone therapy be given at the lowest effective dose and treatment should be reviewed regularly. The aim of this review is to identify the minimum dose(s) of progestogen required to be added to estrogen so that the rate of endometrial hyperplasia is not increased compared to placebo.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to assess which hormone therapy regimens provide effective protection against the development of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group trials register (searched January 2012), The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2012), MEDLINE (1966 to January 2012), EMBASE (1980 to January 2012), Current Contents (1993 to May 2008), Biological Abstracts (1969 to 2008), Social Sciences Index (1980 to May 2008), PsycINFO (1972 to January 2012) and CINAHL (1982 to May 2008). Attempts were made to identify trials from citation lists of reviews and studies retrieved, and drug companies were contacted for unpublished data.

Selection criteria

Randomised comparisons of unopposed estrogen therapy, combined continuous estrogen‐progestogen therapy, sequential estrogen‐progestogen therapy with each other or placebo, administered over a minimum period of 12 months. Incidence of endometrial hyperplasia/carcinoma assessed by a biopsy at the end of treatment was a required outcome. Data on adherence to therapy, rates of additional interventions, and withdrawals owing to adverse events were also extracted.

Data collection and analysis

In this update, 46 studies were included. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. The small numbers of studies in each comparison and the clinical heterogeneity precluded meta‐analysis for many outcomes.

Main results

Unopposed estrogen is associated with increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia at all doses, and durations of therapy between one and three years. For women with a uterus the risk of endometrial hyperplasia with hormone therapy comprising low‐dose estrogen continuously combined with a minimum of 1 mg norethisterone acetate (NETA) or 1.5 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) is not significantly different from placebo at two years (1 mg NETA: OR 0.04; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0 to 2.8; 1.5 mg MPA: no hyperplasia events).

Authors' conclusions

Hormone therapy for postmenopausal women with an intact uterus should comprise both estrogen and progestogen to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Drug Therapy, Combination; Drug Therapy, Combination/methods; Drug Therapy, Combination/standards; Endometrial Hyperplasia; Endometrial Hyperplasia/chemically induced; Endometrial Hyperplasia/prevention & control; Endometrial Neoplasms; Endometrial Neoplasms/chemically induced; Endometrial Neoplasms/prevention & control; Estrogen Replacement Therapy; Estrogen Replacement Therapy/adverse effects; Estrogen Replacement Therapy/standards; Estrogens; Estrogens/administration & dosage; Postmenopause; Progestins; Progestins/administration & dosage; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Uterine Hemorrhage; Uterine Hemorrhage/chemically induced; Uterine Hemorrhage/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Hormone therapy for postmenopausal women with intact uterus

Hormone therapy may be used to manage troublesome menopausal symptoms, but is currently recommended to be given at the lowest effective dose and regularly reviewed by a woman and her doctor. In women with an intact uterus hormone therapy comprising estrogen and progestogen is desirable to minimise the risk of endometrial hyperplasia, which can develop into endometrial cancer. Low‐dose estrogen plus progestogen (minimum of 1 mg norethisterone acetate or 1.5 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate) taken daily (continuously) appears to be safe for the endometrium. For women who had their last menstrual period less than one year ago low‐dose estrogen combined sequentially with 10 days of progestogen (1 mg norethisterone acetate) per month appears to be safe for the endometrium.

Background

Description of the condition

Menopause means the cessation of menstruation and typically occurs in women aged between 45 and 55 years with a mean age of about 51 years. Women are said to be postmenopausal when menstruation has ceased for six to 12 months and blood serum levels of follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH) increase to at least 49 IU/L. The decline in circulating estrogen around the time of the menopause can induce symptoms that affect the well‐being and health of women; hot flushes, insomnia, declining bone mass, night sweats, mood disturbances and vaginal dryness have all been reported. Estrogen therapy has been utilised for the treatment of many of the menopausal symptoms, particularly hot flushes and vaginal dryness. As life expectancy and the proportion of older adults in the population increase, there has been an increased focus on the effects of ageing.

Description of the intervention

Hormone therapy (HT) may consist of unopposed estrogen or a combination of estrogen plus progestogen (E+P).

Unopposed estrogens include conjugated equine estrogen (CEE), ethinyl estradiol (EE), micronised 17β‐estradiol (E2), estradiol valerate (EV), estrone sulphate (EIS) and esterified estrogens (ESE). These estrogens cannot be considered equal. They vary in their dose equivalency and have different metabolic effects on different tissues or end organs. In order to make meaningful comparisons estrogens were grouped into low, moderate and high doses according to the advice of experts (Ansbacher 1994; France 1998; MacLennan 1998; O'Connell 1998). See Table 9.

1. Classification of estrogen dosages.

| Oestrogen | Low dose (mg/day) | Moderate dose (mg/day) | High dose (mg/day) |

| Conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) | 0.15, 0.3, 0.4, 0.45 | 0.625 | 1.25 |

| Piperazine estrone sulphate (POS) | 0.3, 0.625 | 1.25, 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Ethinyl estradiol (EE) | < 0.010 | 0.010 | > 0.010 |

| 17β estradiol (E2) | 0.5, 1.0 | 1.5, 2 | 4 |

| Estradiol valerate (EV) | (EV)0.5 | 1 | 2 |

| Esterified estrogens (ESE) | 0.3 | 0.625 | 1.25 |

There are a number of different progestogens used in HT, which can be classified according to their structure and bioactivity, or both (Lawrie 2011). These include:

micronised progesterone (MP), dydrogesterone (DYG; a retroprogesterone), and progesterone derivatives such as medrogestone (MG);

pregnanes such as medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), megestrol acetate (MA), cyproterone acetate (CPA);

norpregnanes such as trimegestone (TMG), nestorone and promegestone;

estranges such as norethisterone, norethisterone acetate (NETA) and lynestrol, derived from testosterone and collectively known as first‐generation progestogens;

gonane progestogens, which can be divided into two categories ‐ the second‐generation progestogens such as norgestrel (NG), levonorgestrel (LNG) and the third‐generation progestogens, such as desogestrel (DG), gestodene, norgestimate (NGM) and dienogest (DNG);

drospirinone (DSP) ‐ a new progestogen derived from spironolactone not included in the generation classification.

Some progestogens are prodrugs that are metabolised by the liver into active compounds. Examples are promegestone which is converted to TMG, and NGM which is converted to NG.

Why it is important to do this review

Several studies have suggested a causal relationship between unopposed estrogen therapy (daily use of estrogen without the addition of progestogen) and the development of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma (Antunes 1979; Gardan 1977; Grady 1995; HOPE 2001; Smith 1977; Ziel 1975). Endometrial hyperplasia is regarded as a precursor of endometrial cancer but progression is dependent on the type of hyperplasia (Kurman 2000; Terakawa 1997). The estimated risk of hyperplasia progression to cancer is 1%, 3%, 8% and 29% for women with simple, complex, simple atypical and complex atypical hyperplasia, respectively (Kurman 1985). The risk of hyperplasia and carcinoma appears to increase with higher doses and increased duration of unopposed estrogen treatment (Speroff 2005). Adding a progestogen to estrogen therapy significantly reduces the risk of hyperplasia (Corson 1999; Cust 1990;Udoff 1995; Whitehead 1977), but can result in premenstrual symptoms that are problematic for some women. These symptoms and increased bleeding and spotting with both types of HT regimens are often given as a reason not to continue HT (Ellerington 1992; Rozenberg 2001). An additional concern is that the addition of progestogen to estrogen also appears to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and breast cancer (WHI 2002).

As a result of evidence suggesting that HT is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and breast cancer in women aged over 55 years (WHI 2002), current advice is that HT not be used for chronic disease prevention. HT is an effective treatment for women with menopausal symptoms of hot flushes, night sweats and vaginal dryness and the duration of therapy should be decided for individual women based on an assessment of both benefits in terms of menopausal symptom management, and harms of therapy such as venous thromboembolism (Hickey 2005; Roberts 2007). The duration of treatment with HT should be reviewed by a woman with her doctor, because for most women hot flushes resolve within one year of onset of the menopause. About one third of women will continue to have vasomotor symptoms for up to five years and some women for even longer (Hickey 2005).

HT is usually taken orally, but there are also other modalities including transdermal (patches, gels and creams), subcutaneous (implants), intranasal, vaginal and intrauterine. This review will consider only oral HT and the other modalities will be covered in separate reviews.

The original version of this review investigated abnormal vaginal bleeding, and concluded as follows:

Regular withdrawal bleeding is expected with a sequential regimen of E+P but women appear to experience less irregular bleeding than with a continuous E+P regimen. Irregular bleeding or spotting is common in the first year of continuous E+P but following the first year of treatment, bleeding and spotting become more common in sequential E+P regimens. A large proportion of women taking continuous E+P become amenorrhoeic after one year of therapy while withdrawal bleeding continues for women taking sequential regimens.

Bleeding during the first year of continuous E+P therapy does not need investigation with vaginal ultrasound scan, endometrial thickness or endometrial biopsy (or a combination of these), but these investigations should be considered in the second and subsequent years of HT. Unscheduled bleeding on sequential HT should be investigated by hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy. For the 2008 and subsequent updates of this review, we have addressed long‐term endometrial safety outcomes rather than bleeding patterns, and have amended the protocol accordingly

We aimed to assess which of the oral HT regimens, unopposed estrogen or E+P administered either continuously or sequentially, provides the best protection against the development of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma, has better adherence to therapy regimens and the lowest rate of unscheduled biopsies. In addition we aimed to compare the effects of different types, doses and duration of progestogen use on both endometrial hyperplasia and adherence to treatment, in order to determine the minimum dose and duration of progestogen required for endometrial protection.

Objectives

To assess which oral HT regimens provide effective protection against the development of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of oral estrogen or oral combined E+P therapy versus placebo, oral estrogen versus combined oral E+P (sequential or continuous therapy), oral E+P (continuous) versus oral E+P (sequential) with a minimum treatment period of 12 months.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Postmenopausal women with an intact uterus, defined as women who have not menstruated for more than six months and who have a serum FSH of 40 IU/L or greater. It is recognised that this criterion is relatively liberal and that a common definition of postmenopausal status requires a minimum of 12 months to elapse since last menses, but the majority of trials use this more liberal criterion and postmenopausal status is often further confirmed by FSH levels. The definition includes women who have undergone a natural menopause and women who have had bilateral oophorectomy (removal of both ovaries). The participants could be recruited from any healthcare setting or from advertisements.

Exclusion criteria

Perimenopausal women (menstruation less than six months prior to study)

Intercurrent major disease

Previous HT within one month of commencement of the study

Any contraindication to HT (either unopposed estrogen or estrogen + progestogen therapy)

Current use of other sex steroids including tibolone

Types of interventions

Oral interventions administered for a period of 12 months or greater.

Unopposed estrogen versus placebo (low, moderate or high dose)

Combined estrogen + progestogen (continuous) versus placebo

Combined estrogen +progestogen (sequential) versus placebo

Unopposed estrogen versus combined E+P (continuous)

Unopposed estrogen versus combined E+P (sequential)

Combined estrogen + progestogen (continuous) versus E+P (sequential)

Continuous combined estrogen + progestogen (dose comparisons)

Sequential combined estrogen + progestogen (dose/regimen comparisons)

Estrogens vary in their dose equivalency and have different metabolic effects on different tissues or end organs. In order to make meaningful comparisons, estrogens were grouped into 'low', 'moderate' and 'high' dose subgroups. The allocations of different types and doses of estrogens to these groupings were made according to the literature and the advice of experts (Ansbacher 1994; France 1998; MacLennan 1998; O'Connell 1998) and are set out in Table 9. However, disagreement persists among clinical experts regarding categorisation of E2 in the moderate range and two different doses (1.5 mg and 2 mg) of this estrogen have sometimes been included in this category. From the information available (Ansbacher 1994) 0.010 mg EE can be considered equivalent to 0.625 mg CEE and can be considered a moderate dose. Consequently we have modified the categorisation of EE doses in this update of the review.

The progestogens also vary in dose equivalency and metabolic effects on different tissues. As all progestogens share the effect of inducing a structural change in estrogen‐primed endometrium, the potency of a progestogen can be expressed by the difference in dose required in order to achieve this transformation. Estimates of potency based on animal studies give a "transformation dose" per cycle (Kumar 2000). However, the serum level resulting from administration of progestogen to women is dependent on a number of variables including the mode of administration, absorption, metabolism, distribution and storage in fat and other tissues, binding to serum proteins, inactivation and conjugation. We were unable to find empirical evidence as to a 'transformation dose' per cycle in women. In this review we attempted to order the progestogens based on estimates of their relative potency from animal studies (Kumar 2000) as there are few data from studies in humans as to dose equivalency of progestogens used in HT.

In the analysis, continuous and sequential E+P regimens were evaluated separately. For each type of regimen, different doses were compared.

There is evidence that progestogens must be taken for at least 10 days per month to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma (Whitehead 1981), though some studies suggest that progestogens should be given for at least 12 to 14 days (Archer 2001; Sturdee 1994; Whitehead 1987). It was planned to assess separately the effects of sequential progestogen given for less than and more than 10 days per cycle.

The effects of sequential therapy were evaluated separately for different doses and duration of progestogen treatment, and for different treatment regimens (monthly sequential, long cycle (three monthly sequential) and intermittent (three days estrogen only followed by three days E+P, repeated).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Frequency of endometrial hyperplasia (of any type) or adenocarcinoma (assessed by endometrial biopsy)

Secondary outcomes

Requirements for other medical or surgical therapy (e.g. unscheduled endometrial biopsies, hysteroscopy)

Adherence/compliance to therapy

Withdrawal owing to adverse events

Included studies are those where endometrial assessment is planned for every participant at the end of the intervention. Endometrial assessment may be either an endometrial biopsy for all women or measurement of endometrial thickness by transvaginal ultrasound, followed by endometrial biopsy in those women whose endometrial thickness is 5 mm or greater. Studies that did not report rates of endometrial hyperplasia were excluded.

In this review we used the outcome withdrawal owing to adverse events as a proxy for the acceptability of the therapy regimens to women. It is defined as withdrawal owing to adverse events prior to the end of the planned therapy period whether or not the investigator considered that the event was related to the therapy.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all publications that describe (or might describe) RCTs of:

estrogen versus E+P or placebo;

E+P versus placebo;

combined continuous E+P versus sequential E+P therapy;

sequential combined E+P where different regimens are compared;

and their impact on rates of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer in postmenopausal women.

Electronic searches

The original search was performed in 1998. Updated searches were completed in 2003, July 2007, May 2008 and January 2012.

(1) We searched the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group's trials register for any trials (searched January 2003, July 2007, May 2008 and January 2012). See Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group for more details on the make‐up of the trial register. The following search strategy was used:

((Keywords = "*Menopaus*" or Keywords = "postmenopaus*" or #43= "menopaus*" or #43="postmenopausal" ) AND ( Keywords ="*Hormone Therap*" or Keywords = "HRT*" or Keywords = "HT* " ) AND (Keywords = "endometrial biops*" or Keywords ="endometrial hyperpla*" or Keywords ="endometrial response*" or Keywords = "endometrial proliferat*" or Keywords ="bleeding*" or #43= "bleeding pattern*" )) AND NOT (Keywords = "tibolone" or Keywords = "SERM" or Keywords ="raloxifene" or Keywords = "phytoestrogen*" ) Appendix 1 (2) We searched The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2012) , MEDLINE (1966 to January 2012) Appendix 2, EMBASE (1980 to January 2012) Appendix 3, Current Contents (1993 to May 2008), Biological Abstracts (1969 to 2008), Social Sciences Citation Index (1980 to May 2008), PsycINFO (1972 to January 2012) Appendix 4 and CINAHL (1982 to May 2008) Appendix 5.

These electronic databases were searched using the highly sensitive search strategy developed by The Cochrane Collaboration together with the following terms: 1. exp climacteric/ or exp menopause/ 2. (climacter$ or menopaus$).tw. 3. (postmenopaus$ or post‐menopaus$ or post menopaus$).tw. 4. or/1‐3 5. exp estrogens/ 6. exp Contraceptives, Oral, Combined/ 7. hormone replacement therapy/ or oestrogen replacement therapy/ 8. exp Progestins/ 9. (hormone replacement therapy or HRT).tw. 10. (oestrogen$ or progest$).tw. 11. or/5‐10 12. 4 and 11 13. endometrial hyperplasia/ 14. (endometri$ adj5 hyperplasia).tw. 15. (endometri$ adj5 carcinoma).tw. 16. (endometri$ adj5 (biops$ or histology)).tw. 17. (hysteroscop$ or hysterectomy).tw. 18. (adherence or compliance).tw. 19. or/13‐18 20.12 and 19

The output from these searches was transferred to a database, where duplicates were identified and removed. Titles and abstracts were read to identify publications of trials that were potentially eligible for inclusion. We obtained paper copies of all potentially eligible studies. Where there was insufficient information available electronically we obtained paper copies to establish whether a study met the inclusion criteria for this review.

Searching other resources

We searched citation lists of included trials, conference abstracts and relevant review articles. Relevant journals were handsearched for additional trials (see Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group details for more information) and drug companies were contacted for details of unpublished trials.

We made attempts to contact the corresponding author of included trials where data were not in a form suitable for extraction or where information relating to the study was not explicit.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The selection of trials for inclusion in the review was performed by at least two review authors working independently for each of the versions of this review, after employing the search strategy described previously. For the 2008 update of the review selection of included trials was undertaken independently by three review authors (JM, SF and AL) with any discrepancies resolved by discussion. For the 2012 update of the review selection of included trials was undertaken independently by two review authors (SF and JM) with any discrepancies resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Included trials were assessed independently by at least two of the review authors for the following quality criteria and methodological details, with any discrepancies resolved by discussion:

Trial characteristics

Method of randomisation

Presence or absence of blinding to treatment allocation

Quality of allocation concealment

Number of women randomised, excluded or lost to follow‐up

Whether an intention‐to‐treat analysis was done

Whether a power calculation was done

Duration, timing and location of the study

Characteristics of the study participants

Age and any other recorded characteristics of women in the study

Other inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Interventions used

Doses and types of unopposed estrogen therapy used

Doses, types and regimens of E+P therapy used

Duration of HT

Outcomes reported

Endometrial hyperplasia as assessed by endometrial biopsy

Endometrial cancer as confirmed by histology

Requirements for additional investigations to exclude endometrial pathology, including ultrasound, endometrial biopsy or hysteroscopy, or saline infusion sonography

Adherence/compliance to therapy

Withdrawals owing to adverse events

Data extraction and assessment of risk of bias were also performed independently by at least two review authors, using forms designed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011, Table 7.3), with any discrepancies resolved by discussion. Authors included clinical experts and those with statistical or methodological expertise. Where necessary, additional information on trial methodology or original trial data were sought from the corresponding author of any trials that appeared to meet the eligibility criteria.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

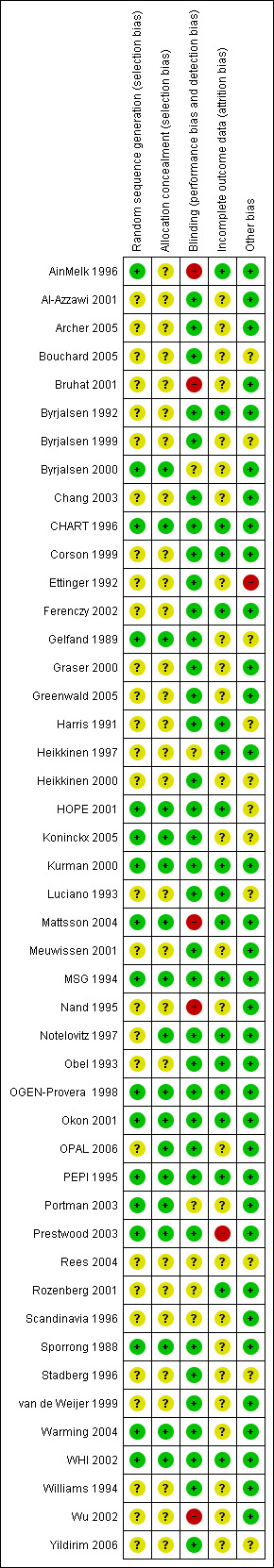

Risk of bias was assessed according to the method described by Higgins 2011; see Figure 1; Figure 2.

1.

Summary of risk of bias: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' domain for each included study (Characteristics of included studies/risk of bias section, for details).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies.

In order to determine the likelihood of publication bias a funnel plot was planned.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, such as endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer and withdrawal owing to adverse effects, we used the numbers of events in the intervention and control arm of each study to calculate Peto‐modified Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (ORs).

Where possible we took an intention‐to‐treat approach and used the number of women randomised to each group to calculate the rates of hyperplasia. This approach is based on the assumption that women who stopped HT and did not return for a biopsy did not have endometrial hyperplasia.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the woman randomised to treatment with HT.

Dealing with missing data

The data were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible and attempts were made to obtain missing data from original trialists. No imputations were made where data were missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between the results of different studies was examined by inspecting the scatter in the data points and the overlap in their confidence intervals (CIs) and, more formally, by checking the Q and I2 statistics (Higgins 2002). As a guide, a value of I2 of 25% or less can be considered a low degree of heterogeneity, a value of 50% or more considered as moderate heterogeneity and a value of 75% or more considered as high heterogeneity. A priori, it was planned to look at the possible contribution of differences in trial design to any heterogeneity identified in this manner.

Assessment of reporting biases

We undertook a comprehensive search for trials and placed no restrictions on language or publication status. Many of the studies included in this review have a number of associated publications. In this review we planned a priori to select only studies that reported the primary outcome of interest for this review; specifically harms of HT ‐ endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma. Publication bias often results in the absence of data on the possible harms of treatment.

Data synthesis

Statistical analysis was performed in accordance with the guidelines for statistical analysis developed by the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group. Where it was clinically appropriate, study outcomes were pooled statistically. It was planned to use a fixed‐effect model for calculation of summary effects in the meta‐analysis. Where significant heterogeneity was demonstrated it was planned to calculate summary effects using a random‐effects model to take account of the added uncertainty.

For dichotomous data (e.g. proportion of participants with hyperplasia or carcinoma), results for each study were expressed as an OR with 95% CIs and combined for meta‐analysis with RevMan software (RevMan 2011) using the Peto‐modified Mantel‐Haenszel method. All outcomes apart from adherence to therapy were categorised so that a high value represented a harm or negative consequence rather than a benefit of treatment. Thus, a negative consequence of treatment is in most cases represented in the graphs as an OR and CI on the right of the centre line.

In order to avoid double counting we chose to use subtotals only where there was a single reference group (e.g. unopposed estrogen or placebo) and two or more comparison groups in a trial.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Comparisons were subgrouped according to the HT regimen (estrogen only, E+P combined either continuously or sequentially) and also by estrogen dose (grouped as low, moderate or high dose ‐ see Table 9) and by progestogen type and dosage given.

Sensitivity analysis

We also planned a priori sensitivity analyses comparing the pooled results of all trials with:

trials with adequate allocation concealment,

trials with double blinding,

trials with < 20% withdrawals,

where there were sufficient studies to make this possible.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Owing to the changes in the protocol for the 2008 update, 12 previously included studies were excluded from the review; three because they had less than 12 months of therapy (Blumel 1994; Pinto 2003;Von Holst 2002), and nine because the primary outcomes were bleeding patterns and these studies did not report endometrial hyperplasia as an outcome (Archer 1999; Hagen 1982;Limpaphayom 2000;Marslew 1991;Marslew 1992;Mizunuma 1997;Simon 2001;Simon 2003;Williams 1990). Three studies previously excluded because they were dose‐finding studies are now included (Bruhat 2001; Graser 2000;OGEN‐Provera 1998). An additional 28 studies were identified that met the inclusion criteria, to give a total of 45 studies included in the updated review.

The searches were again updated in January 2012, and resulted in 297 additional references. The titles and abstracts were screened by two review authors (SF, JM) and 290 were assessed as being not relevant to this review. We obtained full‐text copies of seven references that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, and assessment of these papers resulted in one additional trial being included (OPAL 2006) and six being excluded (Bergeron 2010; Endrikat 2007; Steiner 2007; Stevenson 2010; Sturdee 2008; Veerus 2008; see Characteristics of excluded studies for details).

Included studies

The main analyses were based on 46 trials that involved a total of 39,409 participants randomised to treatment. Not all of the women randomised completed the total period of follow‐up or were included in an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Data extraction was independently performed by at least two review authors (SF, JM, AL).

Study design and setting

The included trials ranged in size from 32 (Nand 1995) to 16,608 participants (WHI 2002). The three largest trials were WHI 2002 (16,608 participants), HOPE 2001 (2673 participants) and MSG 1994 (1724 participants). Twenty eight were multicentre trials and in the remaining 18 trials women were recruited from a single centre. All had a parallel group design. Ten trials had performed a power calculation for sample size and analysis was by ITT (Bruhat 2001; Greenwald 2005; Kurman 2000; Mattsson 2004; OGEN‐Provera 1998; OPAL 2006; PEPI 1995; Portman 2003; Warming 2004; WHI 2002), three trials had power calculations and no ITT analysis (CHART 1996; HOPE 2001; MSG 1994), two studies did not provide power calculations but noted that the planned sample size "probably lacked power" (Ettinger 1992; Williams 1994) and another was a pilot study (Nand 1995). In 30 studies no mention of a power calculation was made. Twenty‐two studies used either a placebo control group or a placebo instead of one of the hormones in order to maintain blinding.

The trials took place in the US (15 studies: Archer 2005;CHART 1996;Corson 1999;Ettinger 1992;Greenwald 2005;Harris 1991;HOPE 2001; Kurman 2000;Luciano 1993;Notelovitz 1997;PEPI 1995;Portman 2003;Prestwood 2003;WHI 2002;Williams 1994); Denmark, Norway and Sweden (three studies: Mattsson 2004;Okon 2001;Scandinavia 1996); Denmark (five studies: Byrjalsen 1992; Byrjalsen 1999;Byrjalsen 2000;Obel 1993; Warming 2004); Finland (two trials: Heikkinen 1997;Heikkinen 2000); Sweden (two trials: Sporrong 1988;Stadberg 1996); the Netherlands (van de Weijer 1999); Europe (Meuwissen 2001); Europe and Scandinavia (Rozenberg 2001); Europe, Scandinavia and the UK (Bouchard 2005); Europe and the UK (three trials: Al‐Azzawi 2001; Koninckx 2005;Rees 2004); Europe and South Africa (Graser 2000); France and Germany (Bruhat 2001) and Turkey (Yildirim 2006). One large trial took place in 99 centres in the US and Europe (MSG 1994), one in 11 centres in the UK and Europe (OPAL 2006), one in Canada (AinMelk 1996) and two in both Canada and the Netherlands (Ferenczy 2002;Gelfand 1989). There was one included trial from China (Wu 2002), one from Taiwan (Chang 2003) and two from Australia (Nand 1995;OGEN‐Provera 1998).

Participants

Most of the included trials specified that women be postmenopausal and this was defined in 32 trials as cessation of bleeding for six months or more prior to entry into the study. In two trials postmenopausal was defined as serum FSH ≥ 40 IU/L (CHART 1996; Rozenberg 2001), in four trials postmenopausal was defined as serum FSH "in the postmenopausal range" (Harris 1991; Heikkinen 1997;Nand 1995;Warming 2004) and in one trial postmenopausal was defined as estradiol < 20 pg/mL (Greenwald 2005). Seven studies did not define postmenopausal (Byrjalsen 1992; Byrjalsen 1999;Mattsson 2004;Scandinavia 1996;Stadberg 1996;Warming 2004;Wu 2002) and in one trial the inclusion criteria specified that participants be older than 65 years and consequently postmenopausal (Prestwood 2003).

Participants ranged in age from 40 to 75 years although in most studies women were in the early menopause with the requirement that women should be within five or less years of their last spontaneous menstrual bleeding. Results can thus be generalised only to women in the early postmenopause rather than all postmenopausal women. Most of the trials also required that women have an intact uterus, or this was implied by the requirement for an endometrial biopsy at baseline, exclusion criterion of previous gynaecological operation or the nature of the primary outcomes. Full details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each study are found in the Characteristics of included studies. Common exclusion criteria were malignancy, chronic illness or use of contraindicated medications.

Interventions

A wide variety of unopposed estrogen or estrogen + progestogen combinations were used as interventions in the included trials. Unopposed estrogens included CEEs, EV, EIS, ESEs, micronised E2 and piperazine oestrone sulphate (POS). Two studies (CHART 1996; Portman 2003) compared placebo with unopposed EE at four different doses and with the same doses continuously combined with NETA. Most of the unopposed estrogen studies compared different doses of the same drug with placebo.

A number of different progestogens were used in the studies included in this review. In alphabetical order these included CPA, DG, DNG, DSP, DYG, gestodene, MPA, MA, NG, NETA, NGM, LNG and TMG.

In some trials, unopposed estrogen treatment was compared with estrogen plus progestogen (E+P) combined treatment, either continuous or sequential.

Sequential combined regimens of HT may be divided into four main types. The most common regimens use unopposed estrogen for part of the cycle followed by E+P for 10 to 15 days per monthly cycle (28 to 30 days). Alternatively there are experimental regimens that use intermittent progestogen (i.e. estrogen only for three days) followed by E+P for three days repeated for up to one year (Byrjalsen 2000; Corson 1999; Rozenberg 2001). Some studies have used regimens where progestogen is added for 10 to 12 days every two or three months (Heikkinen 1997; Scandinavia 1996; Williams 1994) or every six months (Prestwood 2003) (long‐cycle regimens). In one study (Rees 2004) a biphasic regimen comprising 11 days of unopposed estrogen and 10 days of E+P followed by seven days of placebo, was compared with a triphasic regimen comprising 12 days of unopposed estrogen followed by 10 days of E+P, followed by six days of lower‐dose estrogen only. The biphasic regimen in this study was similar to the cyclical regimens that were originally used in HT but were found to be unsatisfactory for women because the troublesome menopausal symptoms returned during the seven‐day placebo phase.

In this review, duration of progestogen therapy varied from 10 to 14 days and it was given at differing times in the treatment cycle.

Where there was only one comparison group of unopposed estrogen and two or more groups with different E+P doses (MSG 1994; PEPI 1995), we chose to use subtotals only, to avoid double counting the comparison group. Likewise, in evaluating the effects of combined E+P, both continuous and sequential, where there was only one comparison group the analyses use subtotals only.

Seventeen of the trials had a placebo control group. Five studies had an estrogen‐only group as the comparison with combined regimens (Archer 2005: Corson 1999;Gelfand 1989;MSG 1994;PEPI 1995). Eleven trials compared two or more different continuous combined regimens or dosages (AinMelk 1996: Bouchard 2005;Bruhat 2001;Graser 2000;Heikkinen 2000;Kurman 2000;Mattsson 2004;Nand 1995;OGEN‐Provera 1998;Wu 2002;Yildirim 2006). Seven studies compared two or more sequential regimens or dosages (Chang 2003; Meuwissen 2001;Okon 2001;Rees 2004;Scandinavia 1996;van de Weijer 1999;Williams 1994) and a further six studies compared a combined sequential regimen with a combined continuous regimen (Al‐Azzawi 2001; Koninckx 2005;Luciano 1993;Rozenberg 2001;Sporrong 1988;Stadberg 1996).

Duration of treatment in the included trials ranged from 12 months to six years but the majority of studies assessed treatment over either one or two years.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were frequency of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma. Some studies assessed endometrial thickness by ultrasound and only performed a biopsy where endometrial thickness was greater than 5 mm. This would appear to be common clinical practice. Endometrial hyperplasia was invariably confirmed by endometrial biopsy and reported at 12, 24 and 36 months. Most studies included any type of hyperplasia as a hyperplasia outcome.

A subgroup of women from the Women's HOPE study were followed up for two years and there were no additional cases of endometrial hyperplasia in the second year except in the women on unopposed estrogen. In another study (Rozenberg 2001) participants were initially randomised to treatment for one year and then an open‐label extension study followed for a second year. Only 65% of those women initially randomised had endometrial biopsies at the end of the second year.

Incidence of endometrial carcinoma was measured as an outcome by 14 studies (Al‐Azzawi 2001;Byrjalsen 1999;Chang 2003;Ferenczy 2002;Koninckx 2005;Kurman 2000; Meuwissen 2001;MSG 1994;Notelovitz 1997;Obel 1993;OPAL 2006;PEPI 1995;Scandinavia 1996;WHI 2002) at different time points: after one, two, three or more than five years of treatment.

A small number of trials (Ettinger 1992; Harris 1991; Heikkinen 1997; Notelovitz 1997; OPAL 2006; Rozenberg 2001) assessed change in bone density, lipid profile, carotid artery or climacteric symptoms as the primary outcomes. Effects on the endometrium and frequency of unscheduled bleeding were secondary outcomes.

The frequency of unscheduled biopsies or dilation and curettage was measured in one large trial (PEPI 1995), and non‐adherence to treatment as measured by pill counts was assessed in only two studies (PEPI 1995; Rees 2004). However, there were significant numbers of participants in most of the trials who withdrew from the trial prior to completion (10% to 50%), owing to adverse events, lack of efficacy or other reasons.

Excluded studies

We retrieved paper copies of an additional 60 studies identified as potentially eligible for inclusion. These were evaluated and subsequently excluded. Twenty‐nine studies had primary outcomes of bleeding patterns or bone mineral density and did not include planned endometrial biopsy, or other means of diagnosing hyperplasia, as an outcome measure (Archer 1999;Archer 2001;Arrenbrecht 2004;Blumel 1994;Byrjalsen 1992a; Byrjalsen 1992b;Campodonico 1996;Chen 1999;Christensen 1982;Gulhan 2004;Hagen 1982;Jaisamrarn 2002;Jirapinyo 2003;Kazerooni 2004;Limpaphayom 2000;Liu 2005;Marslew 1991;Marslew 1992;Mizunuma 1997;Morabito 2004;Odmark 2001;Simon 2001;Simon 2003;Stevenson 2001;Veerus 2008;Wang 2006;Warming 2004a;Weinstein 1990;Williams 1990). Six studies were subsequently found to be non‐randomised (Bergeron 2010; Granberg 2002; Nachtigall 1979;Sturdee 2000;Wahab 2002; Wells 2002) and 11 had a treatment period less than one year (Endrikat 2007; Keil 2002;Luciano 1988;Pinto 2003;Stevenson 2010;Sturdee 2008;Symons 2000;Symons 2002;Utian 2002;Von Holst 2002;Yang 2001). Three studies included women with endometrial hyperplasia at baseline, (Campbell 1977;Popp 2006;Volpe 1986), which is an exclusion criteria for this review; in one study all the participants underwent transcervical resection of the endometrium at baseline (Istre 1996), and another publication (Steiner 2007) was a comparison of subgroups selected retrospectively from two previously conducted randomised studies that drew participants from very different populations. A study published in 1982 (Schiff 1982) compared a now obsolete cyclic estrogen‐only regimen with a continuous estrogen‐only regimen, and therefore did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review. A further eight studies were found by handsearching and published in abstract form only. These publications contained insufficient information to establish eligibility for inclusion in the review and attempts to obtain further information from the authors have been unsuccessful (Aoki 1990;Heytmanek 1990;Pickar 2003a; Sturdee 1996; Ulla Timonen 2002; van der Mooren 1996; van de Weijer 2002; Webster 1996).

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Sequence generation

All 46 trials were randomised but in 29 no details were provided of the method of sequence generation. Four trials used random number tables (AinMelk 1996; Byrjalsen 2000; Sporrong 1988; Warming 2004), and 13 trials used computerised randomisation (CHART 1996; Gelfand 1989; HOPE 2001; Koninckx 2005; Kurman 2000; Mattsson 2004; MSG 1994; OGEN‐Provera 1998; Okon 2001; PEPI 1995; Portman 2003; Prestwood 2003; WHI 2002).

Allocation concealment

Twenty‐eight trials did not describe methods of allocation concealment and were assessed as unclear risk of bias for this domain. The remaining 18 trials were classified as low risk of bias because randomisation was conducted centrally (Byrjalsen 2000; CHART 1996; Gelfand 1989; HOPE 2001; Koninckx 2005; Kurman 2000; Mattsson 2004; MSG 1994; Notelovitz 1997; OGEN‐Provera 1998; Okon 2001; OPAL 2006; PEPI 1995; Portman 2003; Prestwood 2003; Sporrong 1988; Warming 2004; WHI 2002).

Blinding

Thirty‐three of the 46 included trials used double blinding and two trials were single blinded (Byrjalsen 1992; Yildirim 2006). These 35 trials were assessed at low risk of performance and detection bias. In three studies (Byrjalsen 2000; Rees 2004; Rozenberg 2001) some of the participants had open‐label treatment and in a further three trials blinding was not clear (Heikkinen 1997; Portman 2003; Scandinavia 1996) and these six trials were assessed as unclear risk of bias for this domain. Unblinding occurred in 38 women in the PEPI trial (31 of those receiving the unopposed estrogen regimen, four receiving one of the E+P regimens and three receiving placebo) because of endometrial biopsy results classified as complex hyperplasia, atypia or cancer (PEPI 1995). Unblinding also occurred in the WHI trial: 331 participants were unblinded and reassigned to the experimental group owing to the release of the PEPI trial results indicating long‐term adherence to unopposed estrogen was not feasible in women with a uterus. The WHI protocol was subsequently changed to randomise women with a uterus to only E+P or placebo in equal proportions. Five trials were assessed at high risk of performance and detection bias owing to the absence of blinding (AinMelk 1996; Bruhat 2001; Mattsson 2004; Nand 1995; Wu 2002).

Incomplete outcome data

Losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were common, particularly in the larger trials and trials with long duration. In the CHART study, 570 women (45%) had withdrawn (out of a total of 1265) by the conclusion of the trial at two years. In this trial, a priori stopping rules were applied for participants who developed hyperplasia and consequently a proportion of subjects in group 8 (10 μg daily of oral unopposed EE continuously) were terminated from the study early owing to a high rate of hyperplasia. All remaining treatment groups had similar rates of withdrawal that ranged from 22% to 30% and excluding the high‐dose estrogen group, over 73% of the subjects completed the study (CHART 1996). In five other trials more than 40% of the women randomised withdrew prior to the end of the trial (Byrjalsen 1999; Ettinger 1992; Gelfand 1989; Greenwald 2005; Rees 2004). Details of the numbers of and reasons for early withdrawals are in the included studies table.

Where more than 20% of women withdrew during the course of the study (owing to adverse events or other reasons such as change of address and unwillingness to continue to participate) there was a correspondingly low rate of endometrial biopsy. High rates of withdrawals and losses to follow‐up thus reduced the power of the study to detect the primary outcome of interest to this systematic review.

Other potential sources of bias

One publication (Fugh‐Berman 2010) has described how pharmaceutical companies have used medical education and communication companies to create publications as part of a marketing strategy for their products. Academics are then invited to become the 'authors' of these pre‐written articles that contain the desired marketing messages ‐ a practice known as 'ghost‐writing'. The extent of this practice is unclear, but there is evidence that three major articles published about the HOPE 2001 study, which provided data for this review (Archer 2001; Pickar 2003; Utian 2001) were 'ghost‐written' (Fugh‐Berman 2010). However, as 'ghost‐writing' has no influence on statistical data we consider that the likelihood of bias in this review owing to 'ghost‐writing' is low.

Effects of interventions

We extracted data on the cumulative incidence of endometrial hyperplasia at 12, 24 and 36 months. Not all of the studies reported the incidence rates at these time intervals. No differentiation was made in the analysis between the type of hyperplasia (simple, atypical or complex), although this was reported in some studies. Where a study had only one comparison or control group and several different doses in the experimental group, we used subgroups only and did not combine the results, in order to avoid counting the control group more than once.

We have created four additional tables to summarise the lowest dose of progestogen added to various doses of estrogen that result in endometrial hyperplasia rates that are:

statistically significantly reduced compared with unopposed estrogen (Table 10 continuous combined regimens and Table 11 sequentially combined regimens);

not statistically significantly increased compared with placebo (Table 12 continuous combined regimens and Table 13 sequentially combined regimens).

2. Continuous HT ‐ the lowest 'safe' dose; minimum progestogen dose for various estrogen types and doses compared to unopposed estrogen.

| Estrogen dose | P Dose | RCT evidence | Events estrogen alone | Events E+P |

OR (95% CI) |

Duration | Allocation concealment | |

| Low‐dose estrogen | 5 µg EE | 1 mg NETA | CHART 1996 | 4/221 | 0/65 | 3.70 (0.35 to 38.81) |

2 years | Adequate |

| 1 mg E2 | 0.5 DRSP | Archer 2005 | 4/113 | 0/231 | 7.80 (1.93 to 31.51) | 1 year | B | |

| 1 mg E2 | 0.1 mg NETA | Kurman 2000 | 36/247 | 2/249 | 6.98 (3.60 to 13.52) | 1 year | Adequate | |

| 0.3‐0.45 mg CEE | 1.5 mg MPA | HOPE 2001 | 6/65 | 0/144 | 26.97 (4.69 to 155.13) | 2 years | Adequate | |

| 0.45 mg CEE | 2.5 mg MPA | HOPE 2001 | 6/65 | 0/66 | 8.13 [1.59, 41.60] | 2 years | Adequate | |

| Moderate‐dose estrogen | 0.625 mg CEE | 2.5 mg MPA | HOPE 2001; PEPI 1995 | 69/174 | 1/182 | 11.99 (7.09 to 20.27) | 2 years | Adequate; Adequate |

| 0.625 mg CEE | 5 mg MPA | MSG 1994 | 57/283 | 0/274 | 8.92 (5.16 to 15.43) | 1 year | Adequate | |

| 10 µg EE | 1 mg NETA | CHART 1996 | 10/18* | 0/65 | 177.61 (36.08 to 874.43) | 2 years | Adequate |

*this group stopped hormone therapy early owing to high rate of endometrial hyperplasia

3. Sequential HT ‐ the lowest 'safe' dose of progestogen for various types and doses of estrogen compared to unopposed estrogen.

| Estrogen dose | P Dose | RCT evidence | Events estrogen alone | Events E+P |

OR (95% CI) |

Duration | Allocation concealment | |

| Low‐dose estrogen | 1 mg E2 | 30 µg NGM intermittent** | Corson 1999 | 74/265 | 16/260 | 5.91 (3.33 to 10.47) | 1 year | Unclear |

| Moderate‐dose estrogen | 0.625 mg CEE | 5 mg MPA (11‐12 days/month) | Gelfand 1989; MSG 1994 | 65/310 | 4/302 | 20.04 (7.16 to 56.07) | 1 year | Adequate; Adequate |

| 0.625 mg CEE | 10 mg MPA (12 days/month) | PEPI 1995 | 74/119 | 6/118 | 12.71 (7.43 to 21.76) | 3 years | Adequate | |

| 0.625 mg CEE | 200 mg progesterone (12 days/month) | PEPI 1995 | 74/119 | 6/120 | 12.90 (7.55 to 22.05) | 3 years | Adequate | |

| 0.625 mg CEE | 10 mg MPA (12 days/month) | MSG 1994; PEPI 1995 | 82/402 | 1/390 | 67.46 (13.26 to 343.08) | 1 year | Adequate | |

| High‐dose estrogen | 1.25 mg CEE | 5 mg MPA | Gelfand 1989 | 13/23 | 2/20 | 11.70 (2.19 to 62.62) | 1 year | Adequate |

** 3 days E+P followed by 3 days unopposed estrogen only, repeated.

4. Continuous HT ‐ the lowest 'safe' dose: minimum progestogen doses for various types and doses of estrogen compared to placebo.

| Estrogen dose | P Dose | RCT evidence | Events E+P | Events placebo |

OR (95% CI) |

Duration | Allocation concealment | |

| Low‐dose estrogen | 5 µg EE | 1 mg NETA | CHART 1996; Portman 2003 | 0/257 | 1/198 | 0.13 (0.00, 6.48) | 1 year | Adequate; Adequate |

| 5 µg EE | 1 mg NETA | CHART 1996 | 0/130 | 1/59 | 0.04 (0.00 to 2.79) | 2 years | Adequate | |

| 0.3‐0.45 mg CEE | 1.5 mg MPA | HOPE 2001 | 0/144 | 0/61 | not estimable | 2 years | Adequate | |

| 1 mg E2 | 1 mg DSP | Warming 2004 | 0/39 | 0/47 | not estimable | 2 years | Adequate | |

| 1 mg E2 | 25 µg gestodene | Byrjalsen 1999 | 0/34 | 0/43 | not estimable | 2 years | Unclear | |

| Moderate‐dose estrogen | 10 µg EE | 1 mg NETA | CHART 1996 | 0/65 | 1/59 | 0.12 (0.00 to 6.19) | 2 years | Adequate |

| 2 mg E2 | 1 mg NETA | Byrjalsen 2000; Greenwald 2005; Obel 1993 | 0/117 | 1/118 | 0.14 (0.00 to 6.82) | 2 years | Adequate; Unclear; Unclear | |

| 0.625 mg CEE | 2.5 mg MPA | PEPI 1995; HOPE 2001 | 1/182 | 0/180 | 7.33 (0.15 to 369.31) | 2 years | Adequate; Adequate | |

| 0.625 mg CEE | 2.5 mg MPA | PEPI 1995; OPAL 2006 | 1/356 | 2/360 | 0.51 (0.05 to 4.91) | 3 years | Adequate: Adequate |

5. Sequential HT ‐ the lowest 'safe' dose of progestogen for various doses and types of estrogen compared to placebo.

| Estrogen dose | Progestogen dose | RCT evidence | Events E+P | Events placebo |

OR (95% CI) |

Duration | Allocation concealment | |

| Low‐dose estrogen | 0.25 mg E2 | 100 mg progesterone (15 days/6 months) | Prestwood 2003 | 1/51 | 1/57 | 1.12 (0.07 to 18.20) | 3 years | Adequate |

| 1 mg E2 | 5 mg DYG (14 days/month) | Ferenczy 2002 | 0/100 | 0/63 | not estimable | 2 years | Unclear | |

| 1 mg E2 | 25 µg gestodene (12 days/month) | Byrjalsen 1999 | 0/34 | 0/43 | not estimable | 2 years | Unclear | |

| 0.75 mg POS | 0.35 mg NETA (intermittent)** | Byrjalsen 2000 | 0/32 | 0/25 | not estimable | 2 years | Adequate | |

| Moderate‐dose estrogen | 1.5 mg E2 | 150 µg DG (14 days/month) | Byrjalsen 1992 | 0/20 | 0/18 | not estimable | 2 years | Unclear |

| 1.5 mg POS*** | 0.7 mg NETA (intermittent)** | Byrjalsen 2000 | 0/26 | 0/25 | not estimable | 2 years | Adequate | |

| 0.625 mg CEE | 200 mg progesterone (12 days/month) | PEPI 1995 | 6/120 | 2/119 | 2.83 (0.69 to 11.54) | 3 years | Adequate | |

| 2 mg E2 | 1 mg NETA (10 days/month) | Obel 1993 | 0/45 | 0/45 | not estimable | 2 years | Unclear | |

| 2 mg E2 | 10 mg DYG (14 days/month) | Ferenczy 2002 | 0/88 | 0/63 | not estimable | 2 years | Unclear | |

| 2 mg E2 | 25 µg gestodene (12 days/month) | Byrjalsen 1999 | 0/27 | 0/43 | not estimable | 2 years | Unclear | |

| High‐dose estrogen | 2 mg EV | 10 mg MPA (10 days/month) | Heikkinen 1997; Byrjalsen 1992 | 3/41 | 1/43 | 3.19 (0.42 to 24.21) | 2 years | Unclear; Unclear |

| 2 mg EV | 10 mg MPA (14 days/6 months)‐long cycle | Heikkinen 1997 | 0/21 | 1/25 | 0.16 (0.00 to 8.12) | 2 years | Unclear |

**3 days E+P followed by 3 days estrogen only, repeated

*** Piperazine estrone sulphate

In Tables 2 to 5, allocation concealment was used as an indication of overall risk of bias. Allocation concealment is only one aspect of study validity, and has the objective of avoiding selection bias. However, adequate allocation concealment is also strongly associated with the presence of double‐blinding, and it may in addition be a marker for other bias‐reducing strategies (Wood 2008). For more details on individual aspects of study quality, see Characteristics of included studies and risk of bias Figure 1.

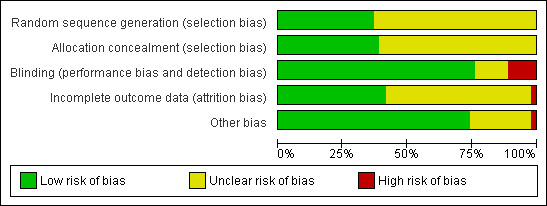

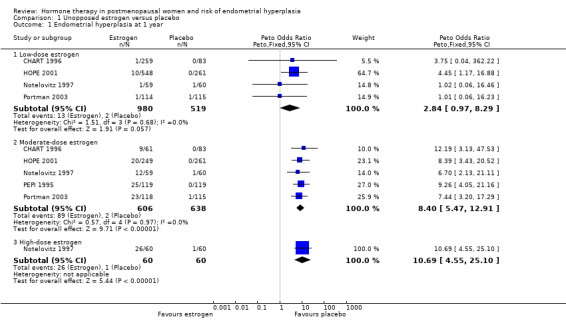

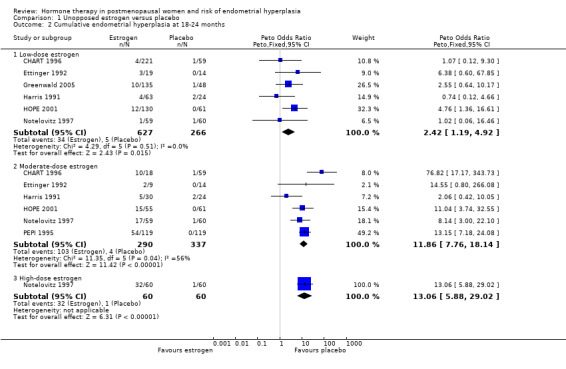

(1) Unopposed estrogen versus placebo

Low dose

After one year of therapy there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of endometrial hyperplasia between the group receiving unopposed estrogen and the placebo group (4 RCTs; OR 2.84; 95% CI 0.97 to 8.29) (Analysis 1.1). However, there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups in the rate of endometrial hyperplasia at 18 to 24 months, favouring the placebo group (6 RCTs; OR 2.42; 95% CI 1.19 to 4.92) (Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Unopposed estrogen versus placebo, Outcome 1 Endometrial hyperplasia at 1 year.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Unopposed estrogen versus placebo, Outcome 2 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 18‐24 months.

One trial with 591 participants (HOPE 2001) noted a statistically significant increase in the rate of endometrial hyperplasia when low doses of CEE (either 0.3 mg or 0.45 mg) were compared with placebo. After 12 months' follow‐up, there was a 1.8% rate of hyperplasia in the low‐dose unopposed groups and 0% rate and no hyperplasia in the placebo group. After two years these rates of endometrial hyperplasia increased to 9.2% for the combined low‐dose groups (3.2% in the 0.3 mg CEE group and 14.9% in the 0.45 mg CEE group) with no hyperplasia in the placebo group.

The other trial, with 490 participants (CHART 1996), noted a 0.4% overall rate of endometrial hyperplasia after one year in the low‐dose estrogen groups (1 to 5 µg EE), compared to no cases of hyperplasia in the placebo group. In the CHART study after two years of therapy the low‐dose estrogen groups showed a 1.8% rate of endometrial hyperplasia, which was not significantly different from the 1.7% placebo rate in this study.

There were no cases of endometrial cancer detected in the one small study that assessed this outcome after two years of therapy (Notelovitz 1997).

There was no statistically significant difference in the rate of withdrawal owing to adverse events between the low‐dose unopposed estrogen and placebo groups (4 RCTs; OR 1.1; 95% CI 0.7 to 1.7).

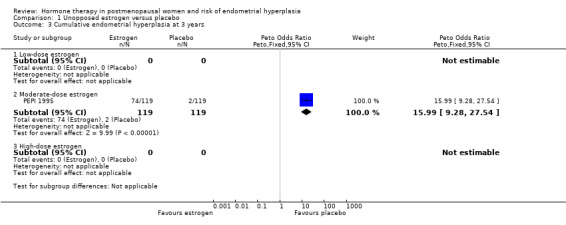

Moderate dose

There were statistically significant differences in the rates of endometrial hyperplasia at 12 months (5 RCTs; OR 8.4; 95% CI 5.5 to 12.9) (Analysis 1.1), 18 to 24 months (6 RCTs; OR 11.9; 95% CI 7.8 to 18.1) (Analysis 1.2) and three years (1 RCT; OR 16; 95% CI 9.3 to 27.5) (Analysis 1.3) in the studies that compared moderate‐dose unopposed estrogen therapy with placebo.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Unopposed estrogen versus placebo, Outcome 3 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 3 years.

After one year of therapy, there were 89 cases of endometrial hyperplasia in the 606 women from five RCTs randomised to moderate‐dose unopposed estrogen (14.7%) compared to two cases in the 638 women randomised to placebo (0.3%) (Analysis 1.1). After two years of therapy there were 103 cases of endometrial hyperplasia in the 290 women randomised to moderate‐dose unopposed estrogen therapy (35.5%) compared with four of the 337 women (1.2%) of those randomised to placebo (Analysis 1.2). After three years, the PEPI 1995 trial showed a 62% rate of endometrial hyperplasia associated with moderate‐dose unopposed estrogen compared to 1.7% in the placebo group (Analysis 1.3).

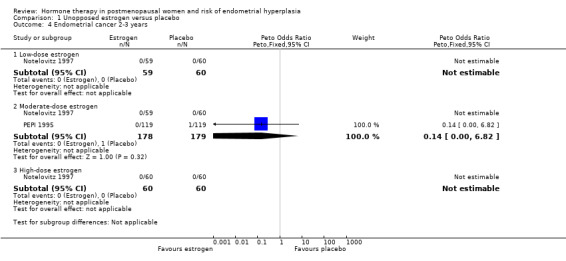

The only case of endometrial cancer in the two trials that assessed this outcome occurred in the placebo group (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Unopposed estrogen versus placebo, Outcome 4 Endometrial cancer 2‐3 years.

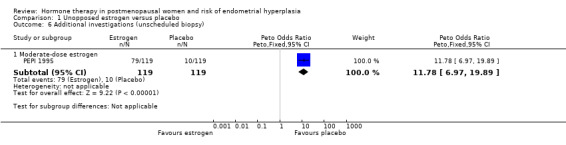

There was a small statistically significant increase in adherence to therapy in the placebo group compared to the unopposed estrogen group in the one study (PEPI 1995) that assessed medication compliance (OR 0.2; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.36) (Analysis 1.5). The only study that assessed the rate of unscheduled biopsies (PEPI 1995) found a significant increase associated with moderate‐dose unopposed estrogen therapy (1 RCT; OR 11.8; 95% CI 7.0 to 19.9) (Analysis 1.6).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Unopposed estrogen versus placebo, Outcome 5 Adherence to therapy at 1 year.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Unopposed estrogen versus placebo, Outcome 6 Additional investigations (unscheduled biopsy).

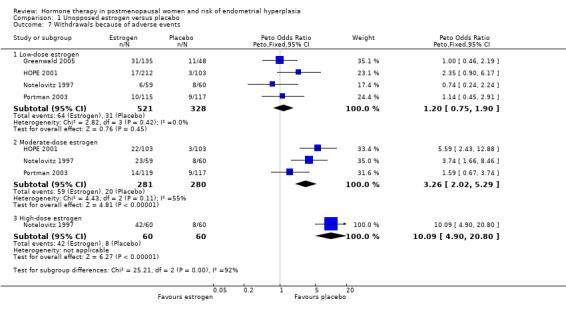

There was no statistically significant difference in the rate of early withdrawal from treatment owing to adverse events in the moderate‐dose unopposed estrogen therapy group compared to the placebo group (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Unopposed estrogen versus placebo, Outcome 7 Withdrawals because of adverse events.

High dose

In the only study (Notelovitz 1997) that compared high‐dose unopposed estrogen therapy with placebo the odds of developing endometrial hyperplasia at 12 months were significantly higher in the intervention group (OR 10.7; 95% CI 4.6 to 25.1) (Analysis 1.1) and increased further at 18 to 24 months of therapy (OR 13.1; 95% CI 5.9 to 29) (Analysis 1.2).

There were no cases of endometrial cancer in either the high‐dose unopposed estrogen or the placebo group after two years of therapy in this study (Analysis 1.4).

The odds of early withdrawal owing to adverse events were significantly higher in the high‐dose unopposed estrogen group than in the placebo group (OR 6.8; 95% CI 3.4 to 14.0) (Analysis 1.7). Vaginal bleeding and endometrial hyperplasia were the main reasons given for discontinuation in the high‐dose group.

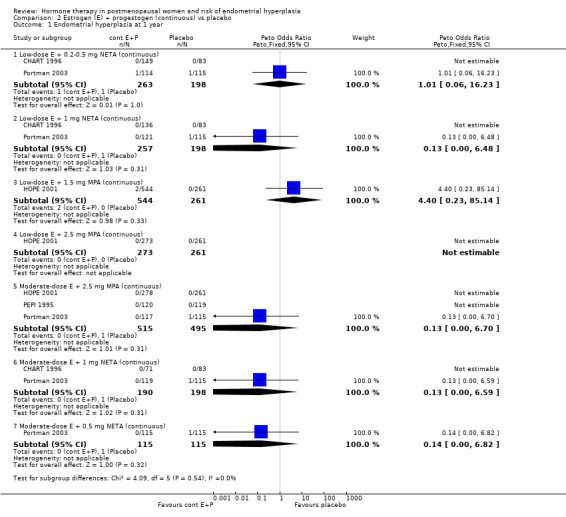

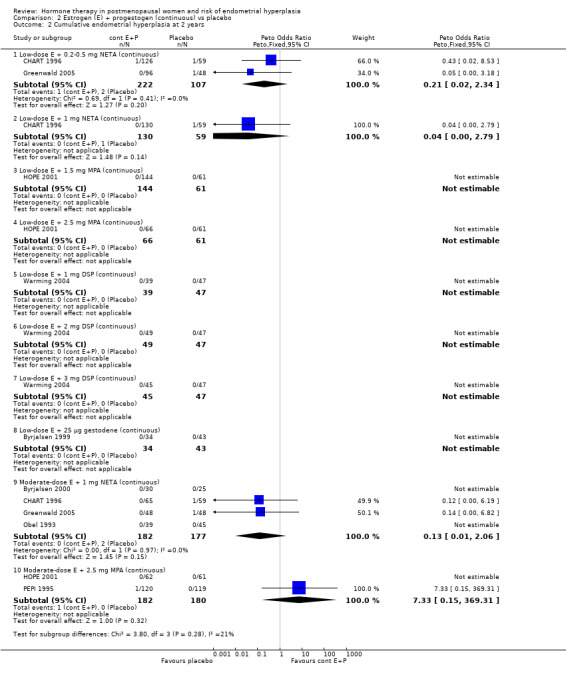

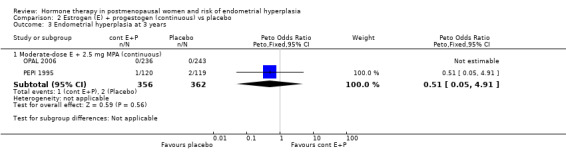

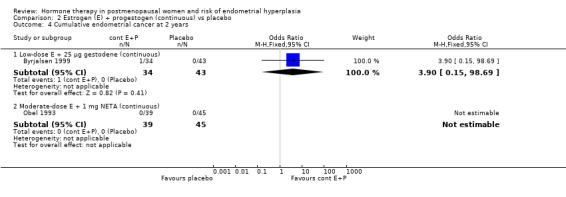

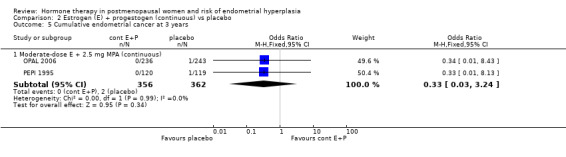

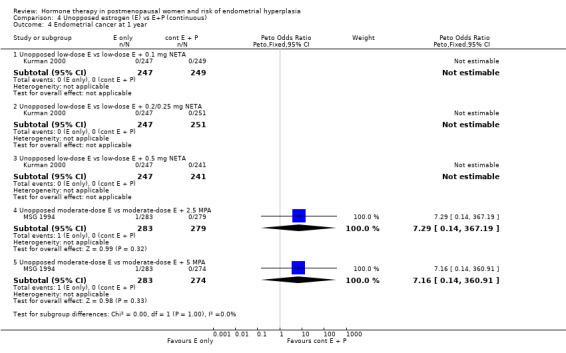

(2) Estrogen plus progestogen (continuous) versus placebo

In the nine RCTs (Byrjalsen 2000; CHART 1996; Greenwald 2005; HOPE 2001; Obel 1993; OPAL 2006; PEPI 1995; Portman 2003; Warming 2004) that compared various doses and types of continuous combined E+P with placebo no statistically significant differences were found between any of the groups in the rates of endometrial hyperplasia after one, two or three years (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3). It should be noted that the OPAL 2006 study included some women who had had a hysterectomy. For the outcomes of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer we have considered the denominator to be the number of women in each group with an intact uterus at baseline (236 and 243 in CEE and placebo groups, respectively). However, for the outcome withdrawal owing to adverse effects we present the only data available that is for all women randomised (288 in each group).

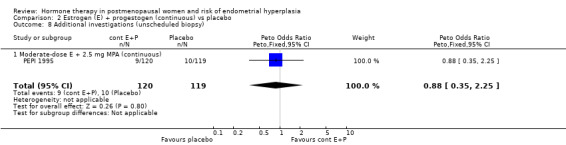

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (continuous) vs placebo, Outcome 1 Endometrial hyperplasia at 1 year.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (continuous) vs placebo, Outcome 2 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 2 years.

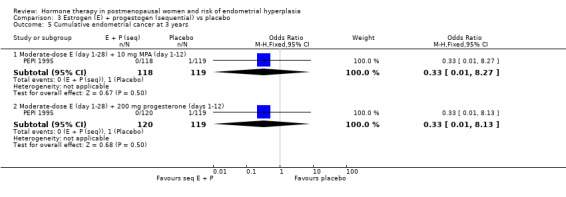

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (continuous) vs placebo, Outcome 3 Endometrial hyperplasia at 3 years.

A summary of the lowest 'safe' dose of progestogens for endometrial protection for the various estrogen doses used can be found in Table 12.

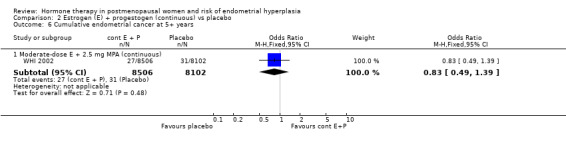

Similarly, rates of endometrial carcinoma were very low in the five studies (Byrjalsen 1999; Obel 1993; OPAL 2006; PEPI 1995; WHI 2002) that reported this outcome, with no statistically significant difference between the groups receiving continuous combined regimens and those on placebo, even after 5+ years of follow‐up (WHI 2002) (Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (continuous) vs placebo, Outcome 6 Cumulative endometrial cancer at 5+ years.

There was no evidence of a statistically significant difference between the groups in the odds of adherence to therapy, unscheduled biopsies or withdrawals owing to adverse events (Analysis 2.7; Analysis 2.8; Analysis 2.9).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (continuous) vs placebo, Outcome 7 Adherence to therapy.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (continuous) vs placebo, Outcome 8 Additional investigations (unscheduled biopsy).

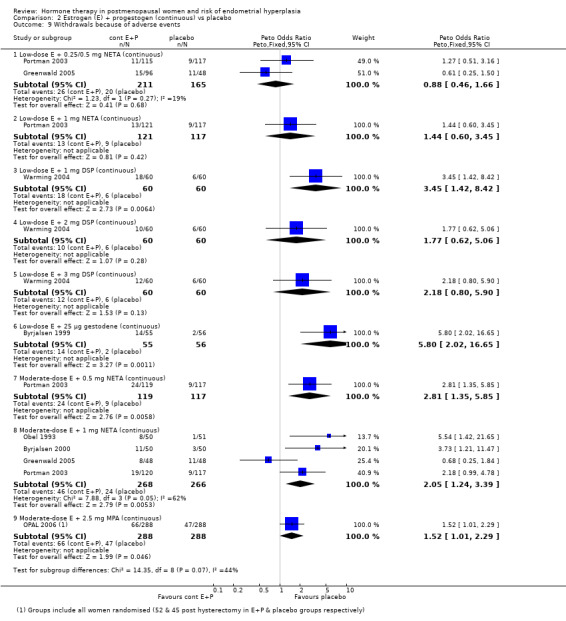

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (continuous) vs placebo, Outcome 9 Withdrawals because of adverse events.

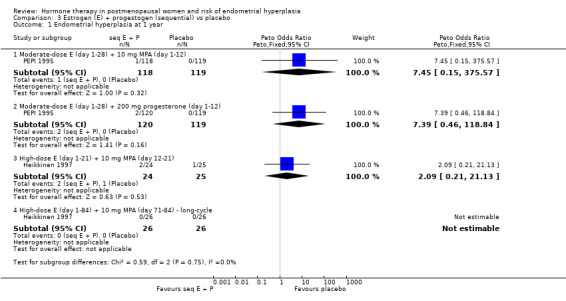

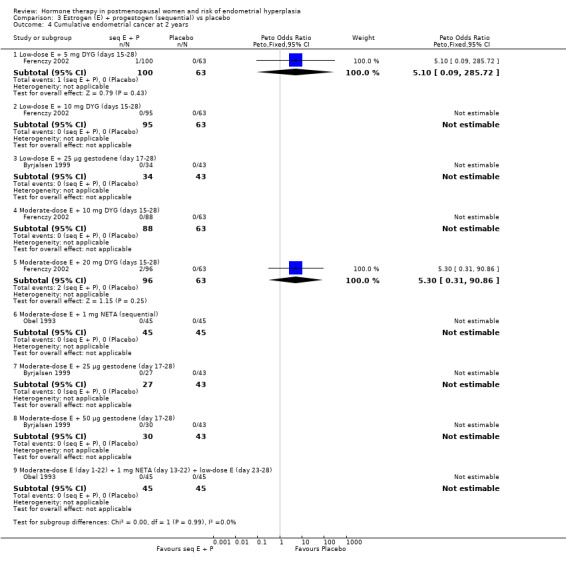

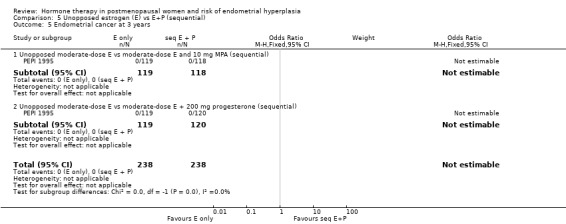

(3) Estrogen plus progestogen (sequential) versus placebo

There were eight RCTs included in this comparison (Byrjalsen 1992; Byrjalsen 1999; Byrjalsen 2000; Ferenczy 2002; Heikkinen 1997; Obel 1993; PEPI 1995, Prestwood 2003).

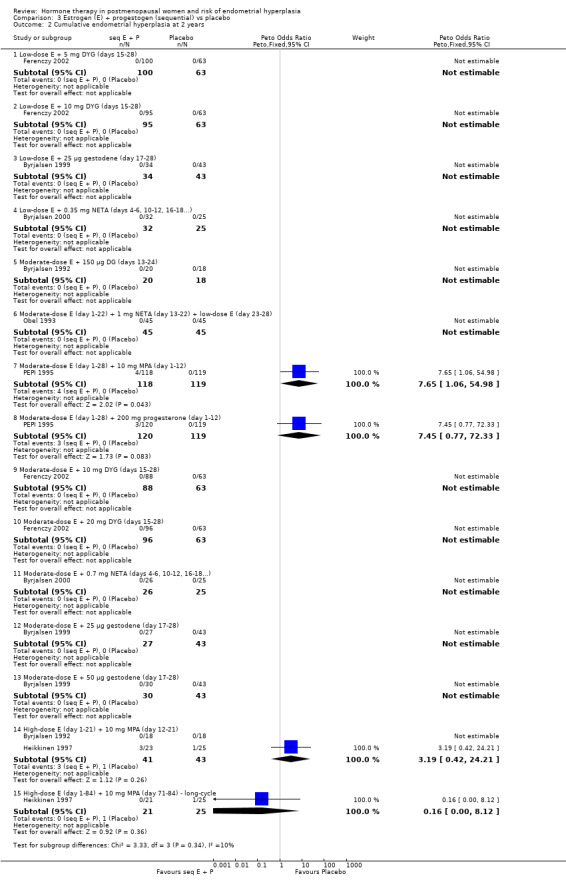

There were no cases of endometrial hyperplasia associated with the low‐dose estrogen sequential regimens in three RCTs (Byrjalsen 1999; Byrjalsen 2000; Ferenczy 2002) over two years of treatment (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (sequential) vs placebo, Outcome 2 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 2 years.

In five of the RCTs that compared moderate‐dose estrogen sequential regimens with placebo (Byrjalsen 1992; Byrjalsen 1999; Byrjalsen 2000; Ferenczy 2002; Obel 1993) no cases of endometrial hyperplasia were found in either group (Analysis 3.2). Regimens were as follows:

1.5 mg E2 plus 150 µg DG for 14 days per cycle (Byrjalsen 1992);

2 mg estradiol plus 1 mg NETA for 10 days per cycle (Obel 1993);

2 mg E2 plus 10 mg DYG for 14 days per cycle (Ferenczy 2002);

2 mg E2 plus 20 mg DYG for 14 days per cycle (Ferenczy 2002);

1.5 mg POS plus 0.7 mg norethisterone (intermittent three days unopposed estrogen, three days E+P) (Byrjalsen 2000);

2 mg estradiol plus 25 µg gestodene for 12 days per cycle (Byrjalsen 1999);

2 mg estradiol plus 50 µg gestodene for 12 days per cycle (Byrjalsen 1999).

In the PEPI 1995 study, two moderate‐dose estrogen sequential regimens were compared with placebo.

This study found a difference in odds of endometrial hyperplasia between placebo and a sequential regimen comprising 0.625 mg CEEs plus 10 mg MPA for 12 days per cycle, which narrowly attained statistical significance after two years (OR 7.65; 95% CI 1.06 to 54.98). The absolute risk of hyperplasia in the sequential regimen group was 3.3% compared with 0% in the placebo group. At three years' follow‐up, there was no evidence of a statistically significant difference in rates of hyperplasia between the groups (OR 2.83; 95% CI 0.7 to 11.5) for any sequential regimen (absolute risk with the MPA sequential regimen had increased to 5.1% compared with 1.7% in the placebo group).

There was no statistically significant difference in the odds of developing endometrial hyperplasia after either two or three years of therapy in the group receiving the other sequential regimen utilised in PEPI 1995 (0.625 mg CEE plus 200 mg MP), compared to the placebo group (Analysis 3.3).

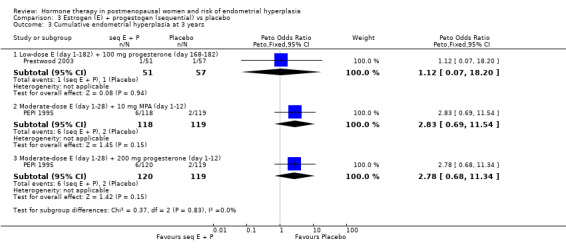

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (sequential) vs placebo, Outcome 3 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 3 years.

In the two studies that compared high‐dose estrogen sequential regimens with placebo (Byrjalsen 1992; Heikkinen 1997) there was no statistically significant difference between the groups in endometrial hyperplasia rates after two years of therapy (Analysis 3.3).

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in any of the included studies in the rates of endometrial cancer (Analysis 3.5) or additional investigations (Analysis 3.6) when sequential regimens were compared with placebo after two or three years of therapy.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (sequential) vs placebo, Outcome 5 Cumulative endometrial cancer at 3 years.

3.6. Analysis.

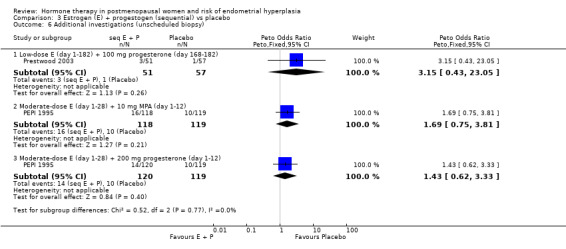

Comparison 3 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (sequential) vs placebo, Outcome 6 Additional investigations (unscheduled biopsy).

In the six RCTs that reported the outcome 'withdrawal owing to adverse events' (Analysis 3.7), most of the regimens showed no statistically significant difference between the intervention and placebo groups. However the odds of withdrawal owing to adverse events were higher in the groups receiving the following regimens:

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Estrogen (E) + progestogen (sequential) vs placebo, Outcome 7 Withdrawal because of adverse events.

2 mg estradiol plus 25 µg or 50 µg gestodene for 12 days per cycle (Byrjalsen 1999);

1 mg estradiol plus 25 µg gestodene for 12 days per cycle (Byrjalsen 1999);

1.5 mg POS plus 0.35 mg NETA taken intermittently (three days on, three days off) (Byrjalsen 2000).

In both RCTs uterine bleeding was a common reason for early withdrawal.

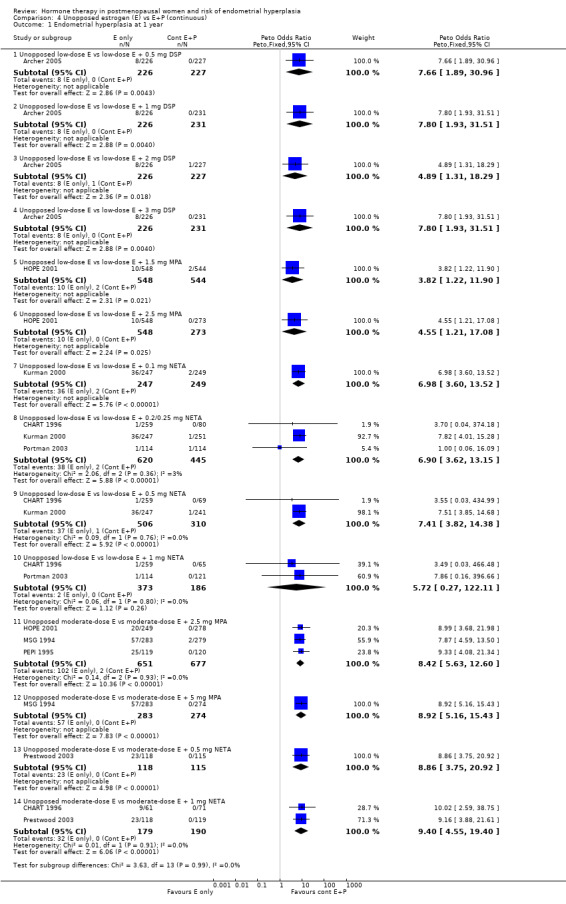

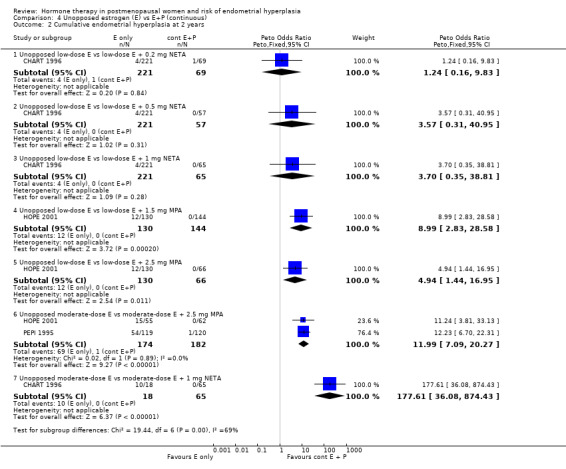

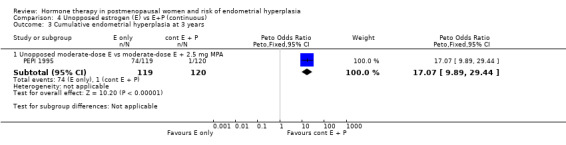

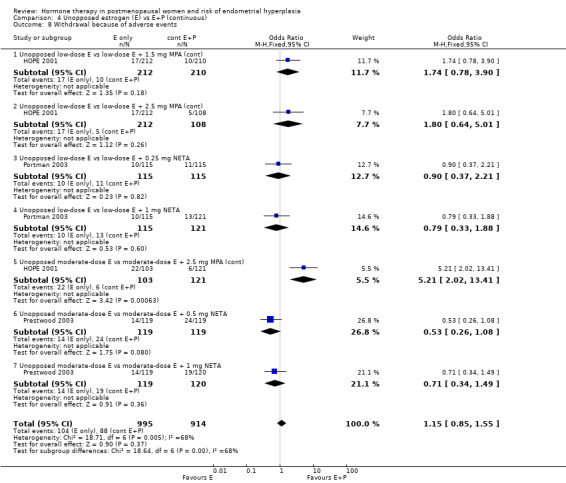

(4) Unopposed estrogen versus estrogen plus progestogen (continuous)

In six trials (Archer 2005; CHART 1996; HOPE 2001; Kurman 2000; MSG 1994; PEPI 1995), rates of endometrial hyperplasia after one year of therapy were significantly higher for the group receiving low‐ or moderate‐dose unopposed estrogen therapy, compared with the group receiving continuous combined low‐ or moderate‐dose E+P treatment, for all of the 13 regimens compared, with ORs for the individual comparisons ranging between 3.8 and 9.4. The summary OR was not calculated because the same control group was used in more than one subgroup in these comparisons (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (continuous), Outcome 1 Endometrial hyperplasia at 1 year.

After one year of continuous combined therapy the groups receiving following regimens containing low‐dose estrogen:

1 mg E2 plus either 0.5, 1, 2 or 3 mg DSP (Archer 2005);

1 mg E2 plus 0.1, 0.25 or 0.5 mg NETA (Kurman 2000);

0.3 mg CEEs plus 1.5 mg MPA (HOPE 2001);

0.45 mg CEEs plus 2.5 mg MPA (HOPE 2001);

1 or 2.5 µg EE plus 0.2 or 0.5 mg NETA (CHART 1996);

showed a statistically significant reduction in the odds of hyperplasia compared to the groups receiving low‐dose unopposed estrogen.

After two years of therapy, the statistically significant decrease in rate of endometrial hyperplasia was still evident for groups receiving the following low‐dose estrogen regimens:

but there was insufficient statistical power to determine the endometrial safety of the 1 to 5 µg EE plus 0.2 to 1 mg NETA regimens (Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (continuous), Outcome 2 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 2 years.

Groups receiving the following regimens containing a moderate dose of estrogen:

0.625 mg CEE plus either 2.5 or 5 mg MPA (HOPE 2001; MSG 1994; PEPI 1995);

10 µg EE plus 1 mg NETA (CHART 1996);

showed a statistically significant reduction in odds of endometrial hyperplasia compared to groups receiving moderate‐dose unopposed estrogen after one or two years of therapy (Analysis 4.2) and the PEPI 1995 study showed that the reduced odds of endometrial hyperplasia persisted after three years of therapy (Analysis 4.3).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (continuous), Outcome 3 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 3 years.

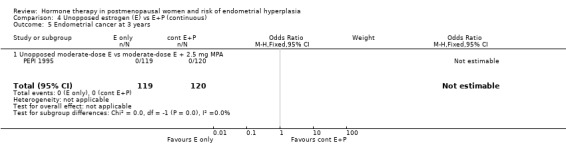

There were three RCTs that compared unopposed estrogen with continuous combined E+P with regard to the outcome of endometrial cancer. After one year of therapy there were no cases of endometrial cancer in either group in Kurman 2000, which compared low‐dose unopposed estrogen only with low‐dose estrogen plus 0.1 to 0.5 mg NETA, and there was only one case of endometrial cancer in MSG 1994 in the unopposed estrogen group. However, this study lacked sufficient power to show a statistically significant difference between the groups with regard to the outcome of endometrial cancer after one year of therapy. PEPI 1995 reported no cases of endometrial cancer in either the moderate‐dose estrogen only group or the moderate‐dose estrogen plus 2.5 mg MPA group after three years of therapy.

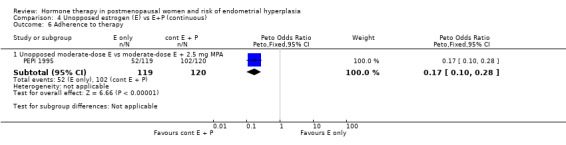

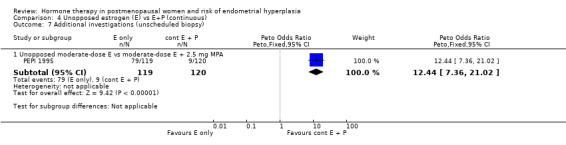

Adherence to therapy as measured by pill counts showed a small but statistically significant increase in the continuous combined E+P group compared to the groups receiving unopposed estrogen (1 RCT; OR 0.2; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.3) (Analysis 4.6) and unscheduled biopsies were more likely under unopposed estrogen treatment (1 RCT; OR 12.4; 95% CI 7.4 to 21.0) (Analysis 4.7).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (continuous), Outcome 6 Adherence to therapy.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (continuous), Outcome 7 Additional investigations (unscheduled biopsy).

Withdrawals owing to adverse effects were significantly higher in the unopposed estrogen group (1 RCT; OR 2.3; 95% CI 1.4 to 4.0) (Analysis 4.8).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (continuous), Outcome 8 Withdrawal because of adverse events.

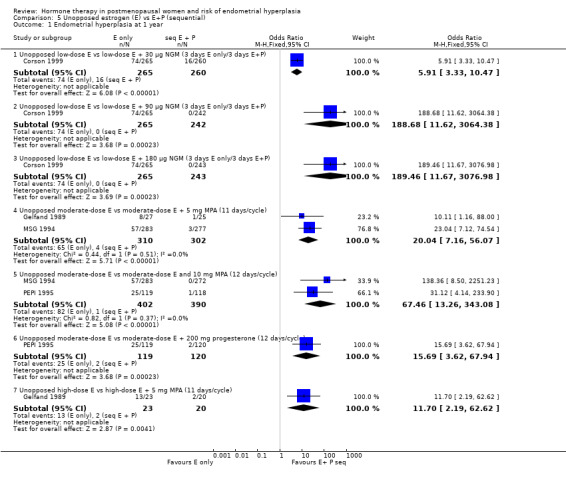

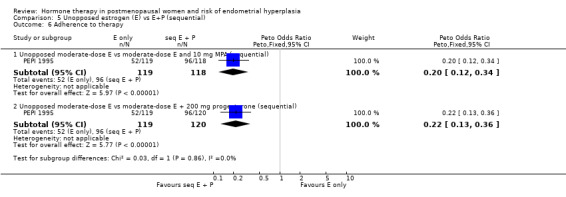

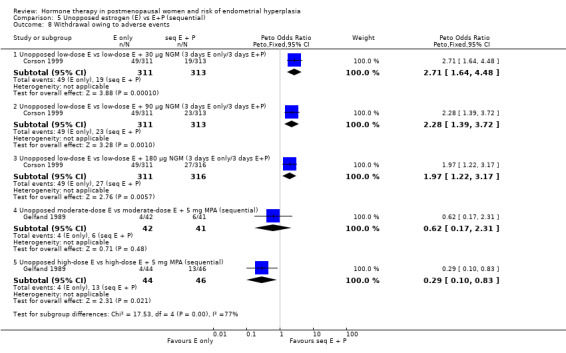

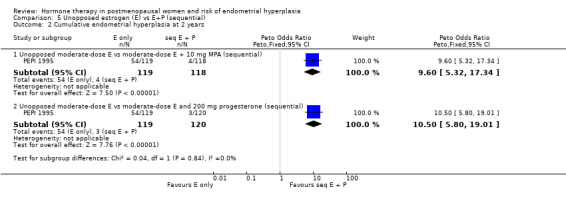

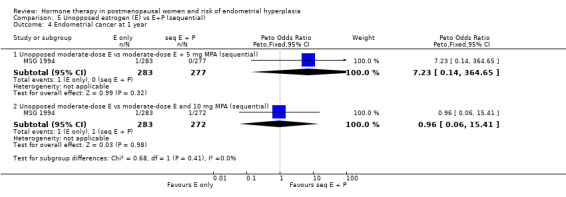

(5) Unopposed estrogen versus estrogen plus progestogen (sequential)

In this comparison sequential combined HT included intermittent regimens where women took estrogen alone for three days, followed by E+P for three days, then estrogen alone for three days (repeated for one year), and also the more common regimen where progestogen was added for 11 or 12 days per cycle.

Four RCTs (Corson 1999; Gelfand 1989; MSG 1994; PEPI 1995) compared sequential E+P regimens with unopposed estrogen using the following doses and regimens:

1 mg E2 plus 30 µg NGM (intermittent three days on/three days off) (Corson 1999);

1 mg E2 plus 90 µg NGM (intermittent three days on/three days off) (Corson 1999);

1 mg E2 plus 180 µg NGM (intermittent three days on/three days off) (Corson 1999);

0.625 mg CEEs plus 5 mg MPA (11 to 12 days per cycle) (Gelfand 1989; MSG 1994);

0.625 mg CEEs plus 10 mg MPA (12 days per cycle) (MSG 1994; PEPI 1995);

1.25 mg CEEs plus 5 mg MPA (11 days per cycle) (Gelfand 1989).

There were statistically significant differences in the odds of developing endometrial hyperplasia at one year between the groups taking unopposed estrogen and the groups taking sequential E+P in all of the regimens compared, favouring the sequential group (Analysis 5.1). These are summarised in Table 11.

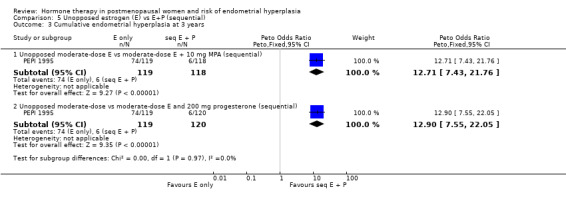

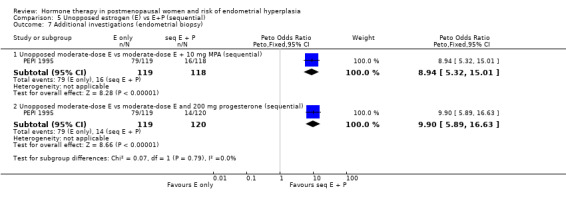

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 1 Endometrial hyperplasia at 1 year.

Only one study (PEPI 1995) followed women treated for more than one year and found that a sequential regimen with 10 mg of either MPA or MP given for 12 days per cycle was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the odds of endometrial hyperplasia compared to an unopposed estrogen regimen (OR 12.8; 95% CI 8.8 to 18.8) after three years of therapy Analysis 5.3.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 3 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 3 years.

After one year of therapy there was no difference in the rate of endometrial cancer (one case in estrogen‐only group and one in the estrogen plus MPA group) in the one study that reported this outcome (MSG 1994). After three years of HT the PEPI 1995 study reported no cases of endometrial cancer in either the unopposed estrogen or the sequential combined groups.

Unscheduled biopsies were more frequent in the estrogen‐only group in the only trial that reported these outcomes (PEPI 1995) (Analysis 5.7) and adherence to therapy was greater in the sequential combined groups compared to the unopposed estrogen group in the same study (Analysis 5.6).

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 7 Additional investigations (endometrial biopsy).

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 6 Adherence to therapy.

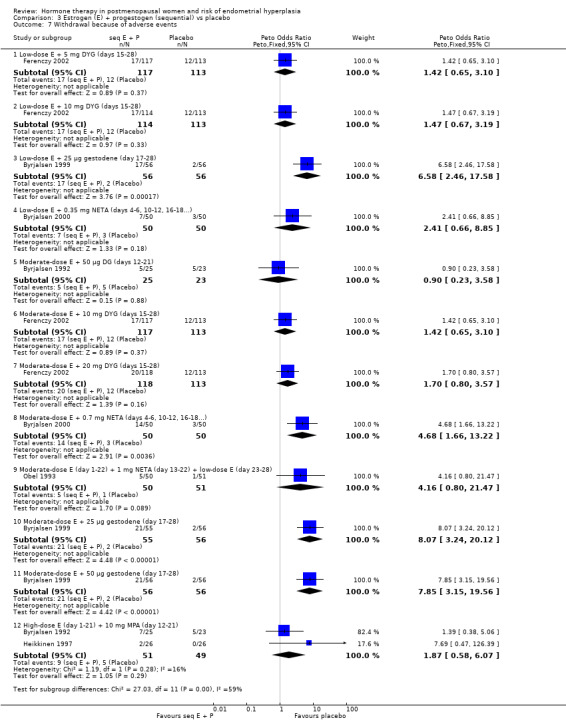

Women were more likely to withdraw because of an adverse event in the unopposed estrogen group in one study that compared low‐dose unopposed estrogen with three different doses of an intermittent three days on/three days off E+P regimen (Corson 1999). However, in the other study that reported this outcome (Gelfand 1989) where unopposed estrogen was compared with a sequential regimen where MPA was added for 11 days per cycle, withdrawal owing to adverse events were similar in both groups receiving moderate‐dose estrogen. In Gelfand 1989, withdrawal owing to adverse events was significantly more likely in the high‐dose sequential group compared to the unopposed high‐dose estrogen group (Analysis 5.8).

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Unopposed estrogen (E) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 8 Withdrawal owing to adverse events.

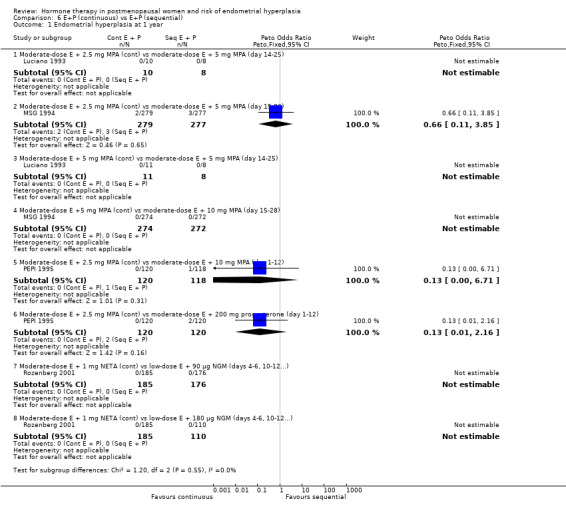

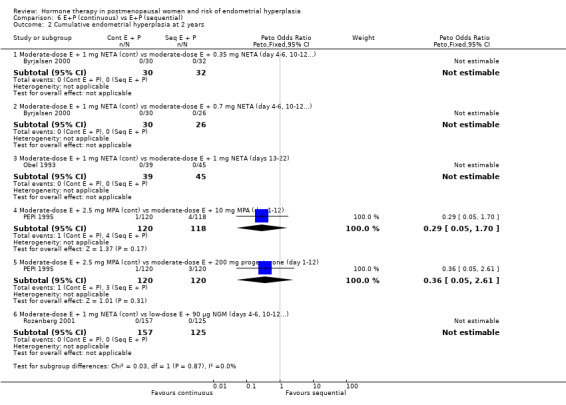

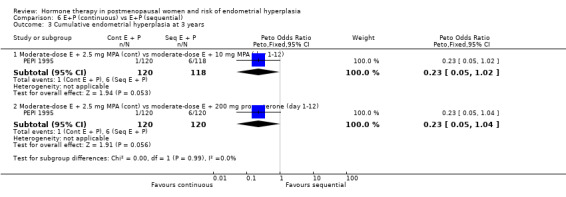

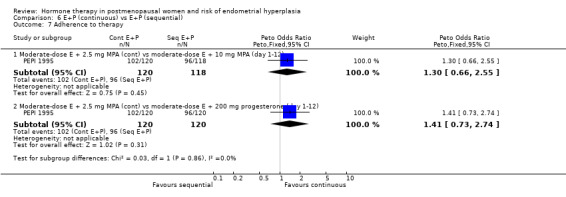

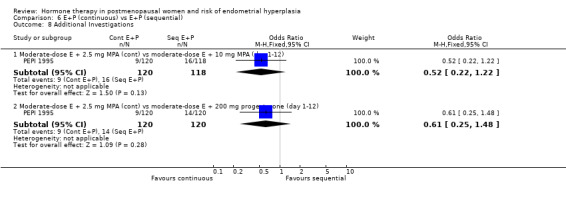

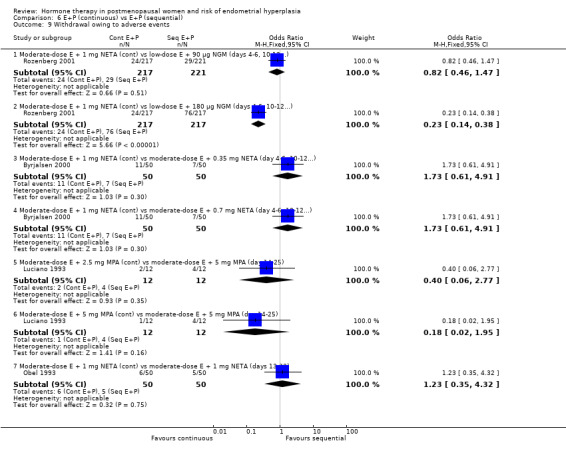

(6) Estrogen plus progestogen (continuous) versus estrogen plus progestogen (sequential)

There were six RCTs that compared sequential combined therapy with continuous combined therapy (Byrjalsen 2000; Luciano 1993; MSG 1994; Obel 1993; PEPI 1995; Rozenberg 2001). The sequential therapy groups included regimens of 10 days' progestogen per cycle (Obel 1993), 12 days' progestogen per cycle (Luciano 1993; PEPI 1995), 14 days' progestogen per cycle (MSG 1994) and regimens where progestogen was taken for three days followed by a three‐day break throughout the cycle (Byrjalsen 2000; Rozenberg 2001; intermittent regimens). The odds of endometrial hyperplasia were not significantly different between the groups receiving continuous and the groups receiving sequential regimens of combined treatment at 12, 24 and 36 months for any of the comparisons included (Analysis 6.1; Analysis 6.2; Analysis 6.3).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 E+P (continuous) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 1 Endometrial hyperplasia at 1 year.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 E+P (continuous) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 2 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 2 years.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 E+P (continuous) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 3 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 3 years.

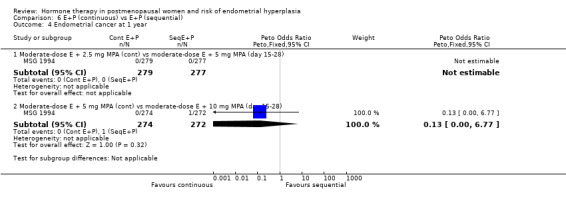

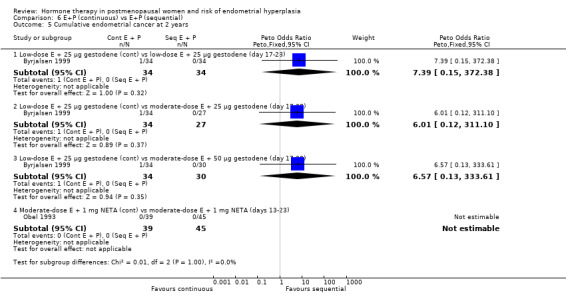

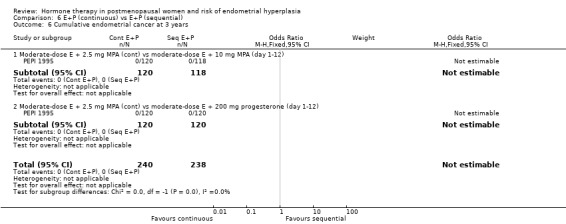

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups receiving continuous and sequential regimens in the rates of carcinoma (Analysis 6.4; Analysis 6.5; Analysis 6.6), adherence to therapy (Analysis 6.7), additional investigations (Analysis 6.8) or withdrawal owing to adverse events (Analysis 6.9).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 E+P (continuous) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 4 Endometrial cancer at 1 year.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 E+P (continuous) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 5 Cumulative endometrial cancer at 2 years.

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 E+P (continuous) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 6 Cumulative endometrial cancer at 3 years.

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6 E+P (continuous) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 7 Adherence to therapy.

6.8. Analysis.

Comparison 6 E+P (continuous) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 8 Additional Investigations.

6.9. Analysis.

Comparison 6 E+P (continuous) vs E+P (sequential), Outcome 9 Withdrawal owing to adverse events.

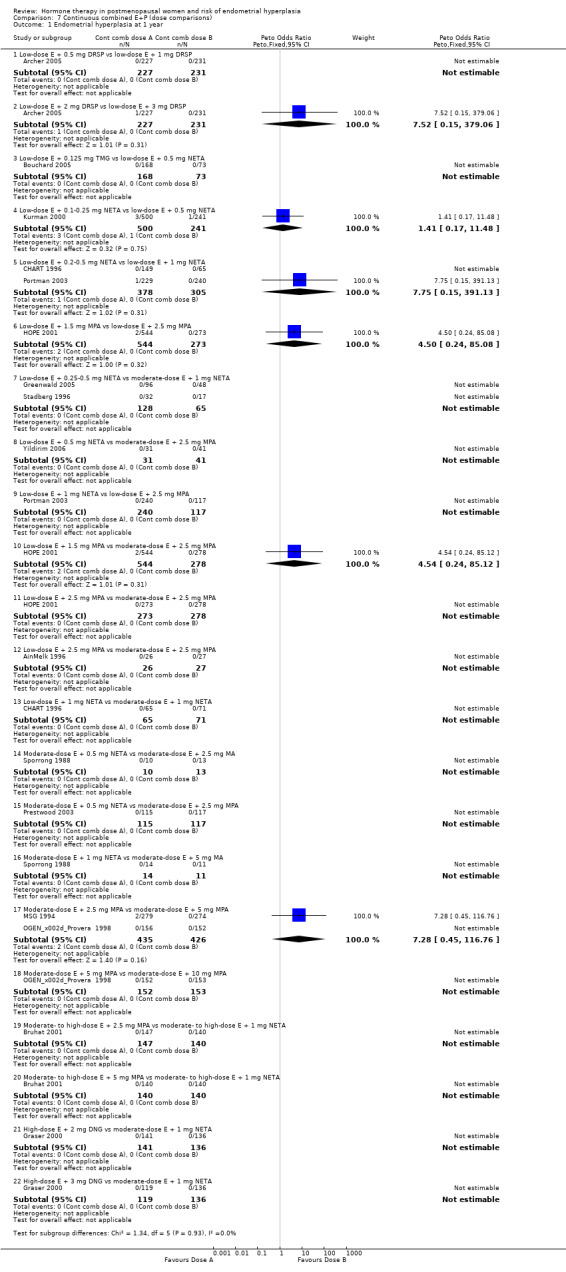

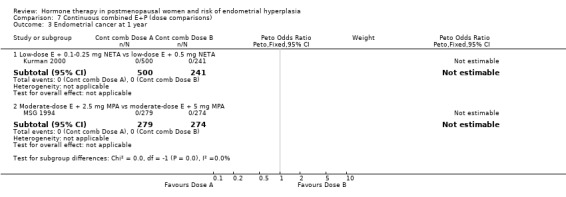

(7) Continuous combined estrogen + progestogen (dose/regimen comparisons)

There were 15 RCTs that compared various dose combinations of continuous combined HT:

six RCTs (Archer 2005; Bouchard 2005; CHART 1996; HOPE 2001; Kurman 2000; Portman 2003) compared low‐dose estrogen combined with various doses of either DSP, TMG, medroxyprogesterone and NETA;

four RCTs (AinMelk 1996; Greenwald 2005; Stadberg 1996; Yildirim 2006) compared low‐dose estrogen combinations with moderate‐dose estrogen combinations;

three RCTs (MSG 1994; OGEN‐Provera 1998; Sporrong 1988) compared moderate‐dose estrogen combined with various doses of either META, MA or MPA;

two RCTs (Bruhat 2001; Graser 2000) compared moderate‐ to high‐dose estrogen combined with various doses of MPA, META or DNG.

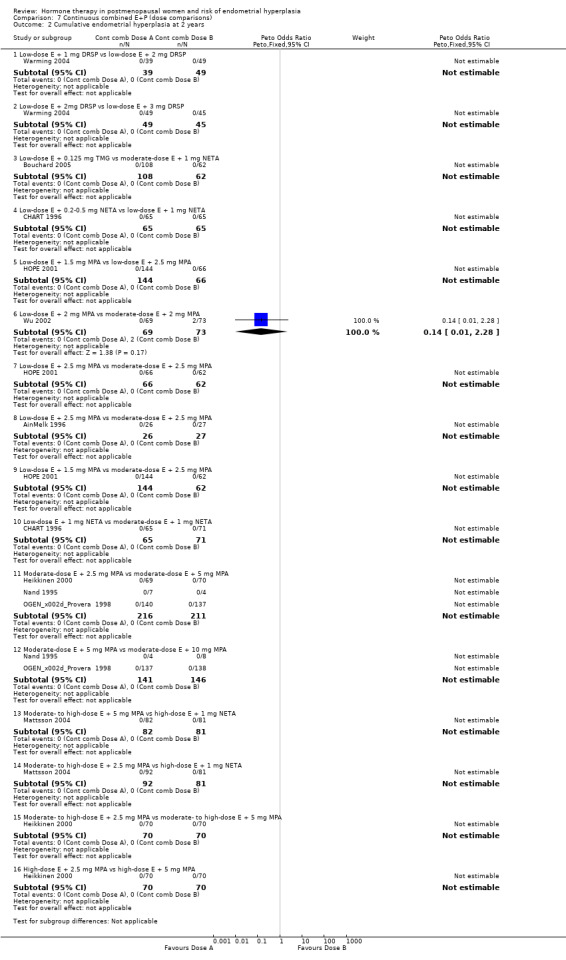

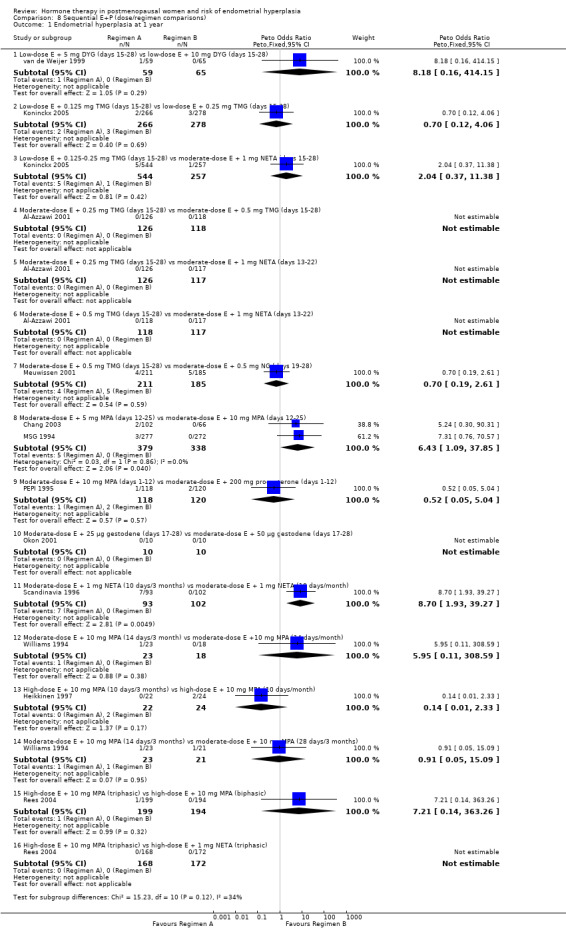

After one or two years of therapy there were no statistically significant differences in the rates of endometrial hyperplasia between groups receiving any of the doses compared in the 15 RCTs included (Analysis 7.1; Analysis 7.2).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Continuous combined E+P (dose comparisons), Outcome 1 Endometrial hyperplasia at 1 year.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Continuous combined E+P (dose comparisons), Outcome 2 Cumulative endometrial hyperplasia at 2 years.

Regimens included the following dose ranges:

low‐dose estrogen continuously combined with either 1 to 3 mg DSP, 0.1 to 1 mg NETA, 1.5 to 2.5 mg MPA or 0.125 mg TMG;

moderate‐dose estrogen continuously combined with 1 mg NETA, 2.5 to 10 mg MPA or 2.5 to 5 mg MA;

high‐dose estrogen continuously combined with 2 to 3 mg DNG.

All of the continuous combined regimens included were associated with low rates of hyperplasia (approximately 0.3% over one year).

In the two RCTs that reported endometrial cancer (Kurman 2000, MSG 1994), no cases were found after one year of therapy.

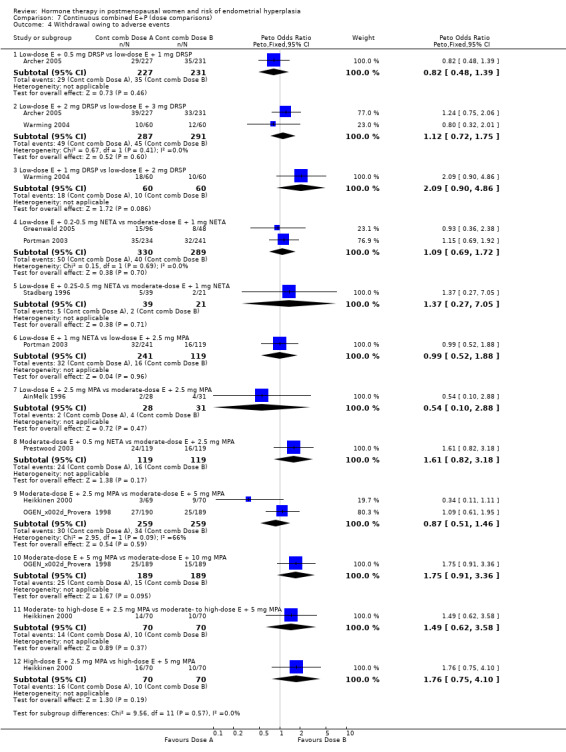

Withdrawal from the study owing to adverse events was reported by eight RCTs and no statistically significant difference was found between the groups receiving any of the continuous combined regimens compared (Analysis 7.4).

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Continuous combined E+P (dose comparisons), Outcome 4 Withdrawal owing to adverse events.

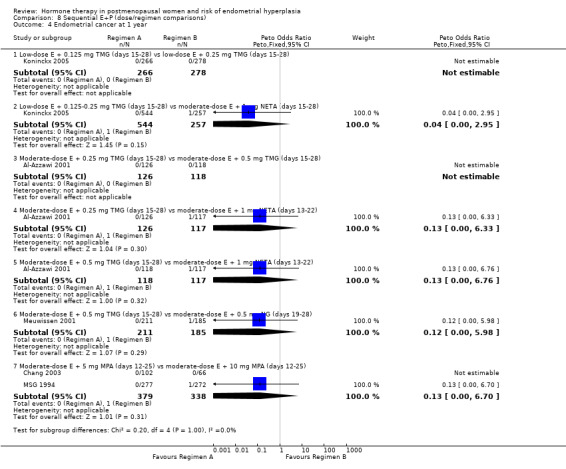

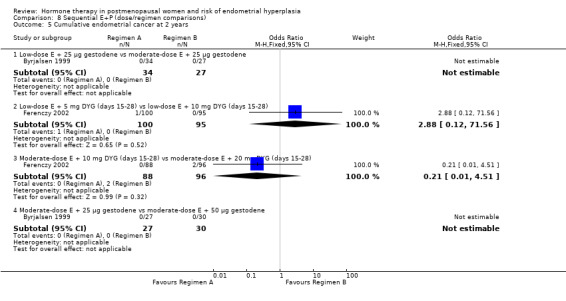

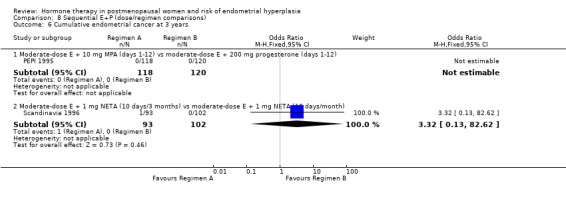

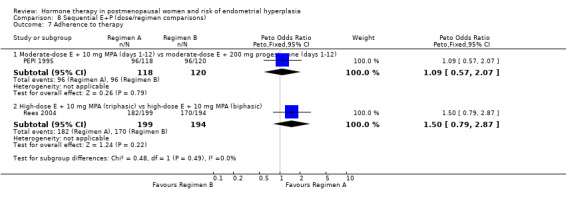

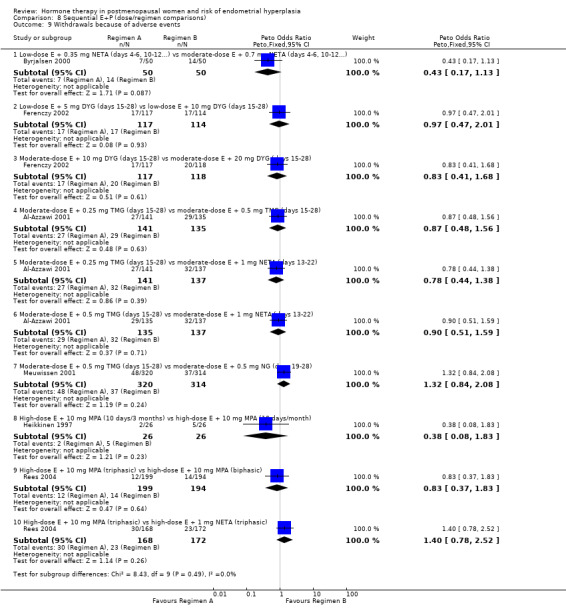

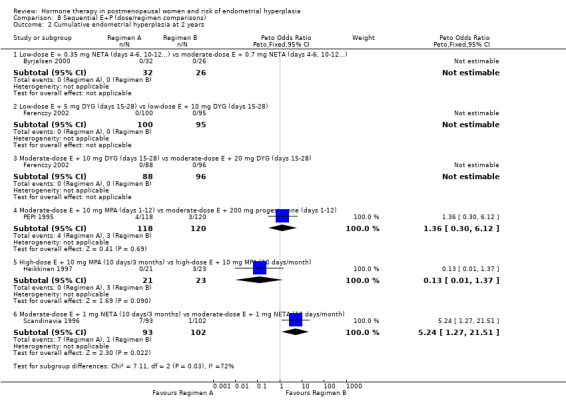

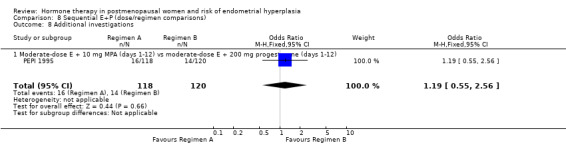

(8) Sequential combined estrogen plus progestogen (dose/regimen comparisons)

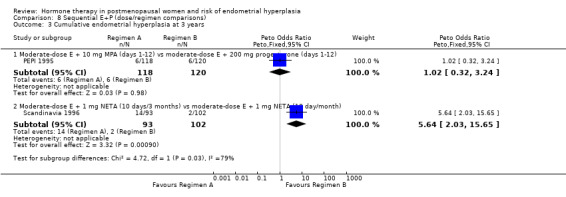

There were 12 RCTs that compared different sequential regimens and doses of HT. The regimens compared fall into five major groups:

five RCTs (Al‐Azzawi 2001; Chang 2003; Koninckx 2005; MSG 1994; van de Weijer 1999) compared different doses of progestogens (TMG, DYG, MPA) taken for 14 days per monthly cycle