Soh et al. study the organization of Tetrahymena ciliary arrays. Basal body–associated striated fibers organize motile cilia by promoting basal body orientation, reorientation, and resistance to ciliary forces. To do so, striated fiber length is modulated to ensure connections between neighboring basal bodies and to the cell cortex.

Abstract

Multi-ciliary arrays promote fluid flow and cellular motility using the polarized and coordinated beating of hundreds of motile cilia. Tetrahymena basal bodies (BBs) nucleate and position cilia, whereby BB-associated striated fibers (SFs) promote BB anchorage and orientation into ciliary rows. Mutants that shorten SFs cause disoriented BBs. In contrast to the cytotaxis model, we show that disoriented BBs with short SFs can regain normal orientation if SF length is restored. In addition, SFs adopt unique lengths by their shrinkage and growth to establish and maintain BB connections and cortical interactions in a ciliary force-dependent mechanism. Tetrahymena SFs comprise at least eight uniquely localizing proteins belonging to the SF-assemblin family. Loss of different proteins that localize to the SF base disrupts either SF steady-state length or ciliary force-induced SF elongation. Thus, the dynamic regulation of SFs promotes BB connections and cortical interactions to organize ciliary arrays.

Introduction

Multi-ciliary arrays comprise hundreds of hydrodynamically coupled cilia that beat in a coordinated and polarized manner. Basal bodies (BBs) nucleate, position, and anchor cilia at the cell cortex. Beating cilia produce both hydrodynamic flow across the cell surface and mechanical forces that are transduced to the BB anchors (Dirksen, 1971; Vernon and Woolley, 2004). Because of the asymmetric nature of ciliary beating, several forces are imposed upon BBs. These include oscillatory, compressive, and rotational forces during the power and recovery strokes (Cheung and Jahn, 1976; Narematsu et al., 2015; Riedel-Kruse et al., 2007). Nevertheless, BBs maintain their position and polar orientation.

Cilia-generated mechanical forces are resisted through BB connections with neighboring BBs and with the cell cortex. These linkages are promoted by BB appendage structures that are classified into distal appendages, basal feet, and striated fibers (SFs). BB distal appendages promote BB docking to the plasma membrane (Garcia and Reiter, 2016; Vertii et al., 2016). In amphibians, basal feet and SFs are polarized along the ciliary beat axis, but are oriented in opposite directions (Hard and Rieder, 1983; Werner et al., 2011). Both structures are generally thought to maintain BB position and orientation by mediating interactions with cortical microtubule, actin, and intermediate filament cytoskeletons (Antoniades et al., 2014; Kunimoto et al., 2012; Lemullois et al., 1987; Vladar et al., 2012). BB-associated SFs are striated structures that are conserved across ciliated eukaryotes (Holberton et al., 1988; Lechtreck and Melkonian, 1991; Yang et al., 2002). In vertebrates, SFs consist of proteins proximal to the BB (C-Nap1, Centlein, and Cep68) that link to proteins that form the SF (Rootletin, Cep68, and Lrrc45; Fang et al., 2014; He et al., 2013; Vlijm et al., 2018). How BB-associated SFs respond to mechanical forces and interact with the cytoskeleton in multi-ciliated arrays remains poorly understood.

The BBs within Tetrahymena multi-ciliary arrays are arranged in longitudinal ciliary rows and possess microtubule appendages and SFs. The microtubule appendages consist of both the post-ciliary microtubule (pcMT) bundles, which project posteriorly from BBs, and the transverse microtubule bundles, which extend rightward (when viewed from the outside of the cell) to the adjacent ciliary row (Allen, 1967; Junker et al., 2019). SFs project anteriorly, to connect with anterior BBs by crossing the surface of the pcMT bundles (Allen, 1967; Junker et al., 2019; Pitelka, 1961). Ciliate cortical organization is promoted by both global and local polarity cues (Frankel, 1989; Frankel, 2008; Sonneborn, 1964). Cytotaxis is a local and nongenetic polarity mechanism, whereby preexisting BBs and their associated structures transmit local polarity information to guide the organization and orientation of new BBs (Beisson and Sonneborn, 1965; Frankel, 1964; Ng and Frankel, 1977; Sonneborn, 1964; Tartar, 1956). However, it is unclear whether and how the cell’s cortical architecture recovers when the local polarity of the system is compromised.

The Tetrahymena BB orientation-defective mutant disA-1 revealed that normal SF length is required for proper BB orientation (Galati et al., 2014; Jerka-Dziadosz et al., 1995). This facilitates BB connections within BB rows and enables the propagation of metachronal ciliary beating for cellular motility (Narematsu et al., 2015; Tamm, 1984; Tamm, 1999). However, the mechanisms by which SFs promote BB organization and orientation, and how their lengths are controlled, remain unknown.

Here, we show that Tetrahymena thermophila SFs physically link neighboring BBs to each other and to the cell cortex to organize, orient, and reorient BBs. SF lengths respond to changes in ciliary forces, such that elevated or reduced cilia-dependent forces cause SFs to elongate and shorten, respectively. As with vertebrate SFs, T. thermophila SFs are composed of a complex network of components that localize to different domains of the SF structure. Components localizing to the SF base ensure both (1) steady-state SF length and (2) elevated ciliary force-induced SF elongation. Using mutants of SF base components to separate these functions, we illuminate the important roles that the unique length states of SFs play in organizing and orienting BBs. These findings serve as a foundation for understanding the role of SF dynamics in anchoring BBs and hydrodynamic flow.

Results and discussion

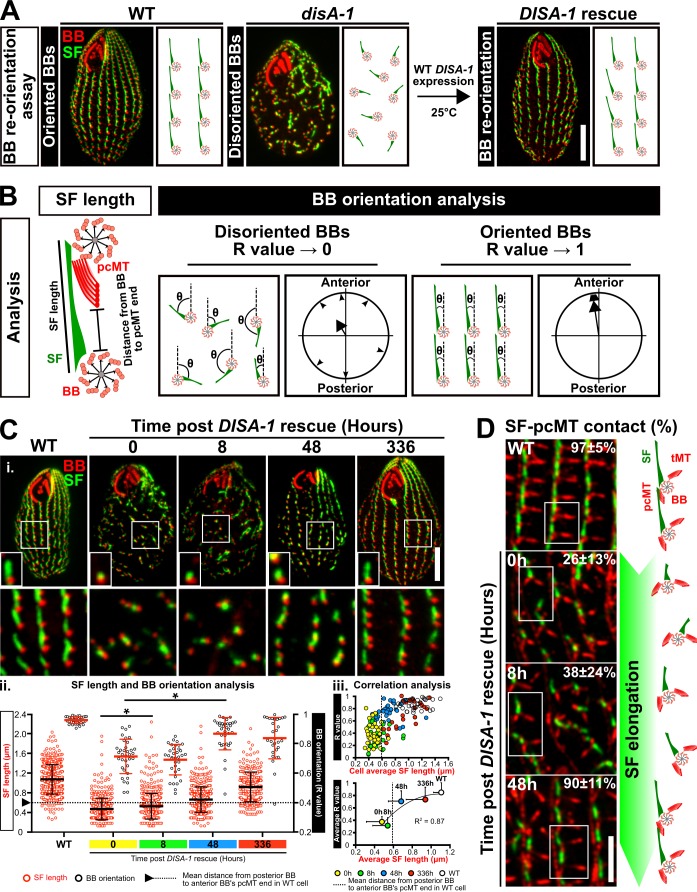

SFs promote BB reorientation

Cells with severely disoriented BBs in disA-1 mutants are rescued by the reintroduction of WT DISA-1 (DISA-1 rescue; Galati et al., 2014). Cytotaxis is a local and nongenetic polarity mechanism, whereby preexisting BBs guide the position and orientation of new BBs such that the existing cortical architecture is propagated to future generations (Beisson and Sonneborn, 1965; Ng and Frankel, 1977; Sonneborn, 1964; Tartar, 1956). However, in contrast to the cytotaxis model, rescue of disoriented BBs in DISA-1 rescue cells suggests that BBs retain the ability to correct their orientation, even in a landscape of disorganized BBs. To visualize BB reorientation, we increased BB disorientation by incubating DISA-1 rescue cells at high ciliary forces (37°C for 24 h) and then initiated BB reorientation by acute DisAp expression at low ciliary forces (DISA-1 rescue; 25°C; Fig. 1 A). BB orientation is defined by the axis of the BB and their associated SFs relative to the cell’s anterior–posterior polarity (Fig. 1 B; Galati et al., 2014). This was monitored along with SF length relative to time after expression of WT DisAp. SF elongation begins within 8 h after DisAp expression, and BBs begin to reorient by 48 h. Thus, SF elongation initiates before BB reorientation (Fig. 1, Ci and Cii). Although mild recoveries in SF length and BB orientation were observed in the negative control (uninduced condition), they were attributed to leaky GFP-DisAp expression (Fig. S1 E). Importantly, SF length positively corresponds with proper BB orientation (Fig. 1 Ciii, single cell level R2 value = 0.87; and Fig. S1 D, individual BB level R2 value = 0.92). This further suggests that SF elongation is important for promoting BB orientation and reorientation.

Figure 1.

SFs promote BB reorientation. (A) The BB reorientation assay. BB disorientation was exacerbated by shifting DISA-1 rescue cells from 25°C to 37°C for 24 h. To promote BB reorientation, cells were shifted from 37°C to 25°C coincident with WT DisAp protein expression. (B) Schematic of SF length measurements, distance measurements from the posterior BB to the anterior BB’s pcMT distal end to establish the minimal SF length that is required for SF–pcMT contact, and BB orientation analyses. BBs and pcMTs, red; SF, green. (C) i and ii: DisAp expression leads to SF elongation before BB reorientation. BB reorientation occurs when SF length surpasses the minimal length that is required for SF–pcMT interactions (arrowhead and dotted line marks the mean distance from the posterior BB to the anterior BB’s pcMT distal end in WT cells). SF length and BB orientation partially recover 2 wk after DISA-1 rescue. BB, red; SF, green. All small insets show a representative BB and SF. i, bottom: White box marks region of interest (large inset). iii, top: Average SF length positively corresponds with BB orientation (R value) on the single cell level during DISA-1 rescue. iii, bottom: Correlation analysis between the average SF length and BB orientation during DISA-1 rescue. BB orientation in most cells is recovered once SF length surpasses the minimal length that is required to establish SF–pcMT contacts (dotted line marks the mean distance from the posterior BB to the anterior BB’s pcMT distal end in WT cells). Data points are fitted with a polynomial (order = 2) function. n ≥ 300 SFs (≥30 cells). Mann-Whitney test. * denotes P value <0.01. Mean ± SD. Scale bars, 10 µm (cell), 1.3 µm (small inset width), 7.8 µm (large inset width). (D) Frequency of SF–pcMT contacts is increased as SF length recovers in DISA-1 rescue cells. Schematic illustrates the position and orientation of two BBs within a region of interest (white box). BB-associated microtubule appendages, red; SF, green. n = 240 SFs (24 cells). Scale bar, 5 µm. tMT, transverse microtubule.

Figure S1.

SFs promote BB reorientation. (A) Widefield image depicting BB disorientation in WT cell. Arrow marks disoriented BBs. Scale bar, 10 µm (cell), 4.5 µm (inset width). (B) Distribution of SF length measured from SIM-acquired SF-BB images. (C) Distance measurements between posterior BB and anterior BB’s pcMT distal end in WT cells at steady-state and elevated force-induced state. Scale bars, 500 nm. (D) i: SF length positively corresponds with proper BB orientation (angle: SF angular displacement from its associated BB to the cell’s anterior pole) on the individual BB level during DISA-1 rescue. (ii) Correlation analysis between the average SF length and BB orientation (angle) during DISA-1 rescue. Most BBs regain proper orientation once the length of their SFs surpasses the minimal length to establish SF–pcMT contacts (dotted line marks the mean distance from the posterior BB to the anterior BB’s pcMT distal end in WT cells). Data points are fitted with a polynomial (order = 2) function. (E) Negative control of BB reorientation analysis under cycling condition. Recoveries in SF length and BB orientation were attributed to leaky DisAp expression. (F and G) BB reorientation analysis under noncycling conditions. (F) Under noncycling conditions, DISA-1 rescue promotes SF lengthening before BB reorientation. (G) Negative control of BB reorientation analysis under noncycling condition. SF length and BB orientation recovery do not occur without DisAp expression. (H) BB reorientation analysis under reduced ciliary force. Under reduced ciliary force, SFs remained short and BBs failed to reorient. All small insets show a representative BB and SF. (B–H) n = ≥300 SFs (≥30 cells). Mann-Whitney test. * denotes P value <0.01. Mean ± SD. (E–H) Scale bars, 10 µm (cell), 1.3 µm (small inset width), 5 µm (BB rows inset). (I) Top: DISA-1 rescue isolates are rescued upon DisAp expression. Scale bars, 10 µm (cell), 2 µm (inset). (I) Bottom: DISA-1 rescue isolates recover at different rates. BB, red; SF, green.

Since SF distal ends are normally juxtaposed to the anterior BB’s pcMTs, we hypothesized that SF elongation in DISA-1 rescue cells enables disoriented BBs to establish attachments to the pcMTs of anterior BBs, thereby regaining BB orientation. To test this hypothesis, we measured the proportion of SF–pcMT interactions during DISA-1 rescue. As SFs elongate in DISA-1 rescue cells, the frequency of BBs with SF–pcMT interactions increases by 48 h (Fig. 1 D). Based on the relative position of the anterior BB’s pcMT distal end in WT cells, SFs must attain a minimum length of 0.59 ± 0.25 µm to establish SF–pcMT interactions (Fig. S1 C). Consistent with this, we observed that disoriented BBs in DISA-1 rescue cells began to regain BB orientation once the mean SF length surpassed this minimum length (Fig. 1, C and D; and Fig. S1 D).

To test whether BB reorientation occurs in single cells, we increased BB disorientation in DISA-1 rescue cells using the same BB-disorientation regimen described earlier (high ciliary forces, 37°C for 24 h) and followed the rescue of single-cell DISA-1 rescue isolates grown under cycling conditions. Upon the induction of DISA-1 rescue at low ciliary forces (25°C), DISA-1 rescue isolates underwent BB reorientation (Fig. S1 I, top). Interestingly, DISA-1 rescue isolates recovered at different rates (Fig. S1 I, bottom). Since a subpopulation of cells still retains poor BB orientation even at 336 h after DISA-1 rescue induction, we postulate that the difference in recovery rate results from the varying degree of BB disorientation at the onset of the experiment (Fig. 1 Ciii and Fig. S1 D). Cells with more severe BB disorientation may require a longer recovery time. Collectively, this suggests that T. thermophila cells possess error correction mechanisms to resolve BB disorientation. Indeed, spontaneous BB disorientation was observed in 5% of WT cells (Fig. S1 A). While SF-independent mechanisms, such as the potential role of neighboring cortical structures that promote BB reorientation, cannot be ruled out, we propose that SF elongation ensures the propagation of orientated BBs to future cell progeny.

In cycling cells, new BBs assemble, thereby reducing the spacing between neighboring BBs. This could promote BB reorientation during DISA-1 rescue. To test this, cells were starved to inhibit both cell cycle progression and new BB synthesis. We first increased BB disorientation in DISA-1 rescue cells before inhibiting cell cycle progression and BB duplication during DISA-1 rescue. Non-cycling DISA-1 rescue cells were equally efficient as cycling cells in BB reorientation. This suggests that cell cycle progression and new BB synthesis are not required for BB reorientation (Fig. S1, F and G). We postulate that this is because new BBs assemble from disoriented BBs, thereby further propagating BB disorientation.

We next tested whether ciliary beating promotes BB reorientation by translocating BBs to their proper position and orientation. To test whether ciliary beating is required for BB reorientation, we reduced ciliary beating during DISA-1 rescue. NiCl2 treatment was used to inhibit dynein motor activity and ciliary beating (Larsen and Satir, 1991). In NiCl2-treated media, disoriented BBs failed to reorient with reduced ciliary beating 48 h after DISA-1 rescue (Fig. S1 H). However, SF length remained short, suggesting that cilia-dependent forces are necessary for SF elongation during DISA-1 rescue. Because SFs did not elongate, we did not determine whether ciliary beating is important for promoting BB reorientation toward the cell’s anterior pole.

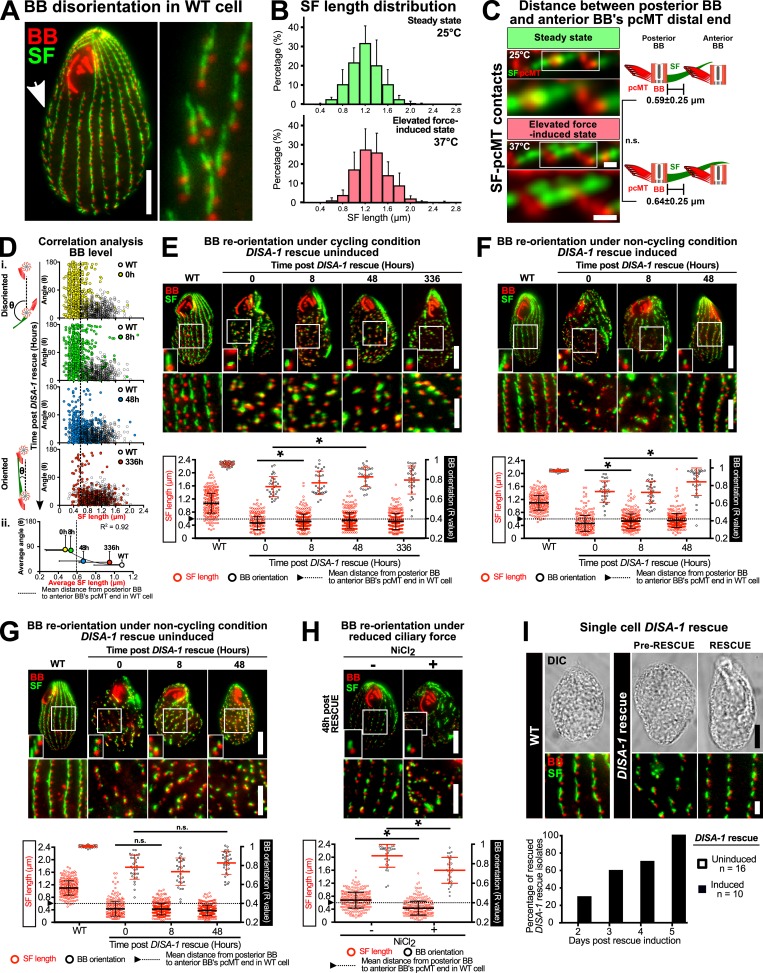

Ciliary forces tune SF length

To investigate the relationship between ciliary forces and SF length, we exposed cells to a range of ciliary forces and quantified SF length. Consistent with our prior work, SFs of WT cells elongate by 16% when cell swimming and cilia-dependent forces are increased with elevated temperature for 4 h (elevated force-induced state; Fig. 2, A and C; Galati et al., 2014). Because SFs commonly overlap with each other (66%), the number of SFs that could be spatially resolved by conventional fluorescence microscopy was limited. Using structured illumination microscopy (SIM), a larger proportion of SF lengths was resolvable, and was quantified to show that SFs generally elongate with elevated ciliary forces (Fig. 2 A and Fig. S1 B).

Figure 2.

SFs elongate and shorten with ciliary force. (A) Cell motility and SF length of WT cells were elevated by increasing temperature (37°C for 4 h). (B) Cell motility and SF length of the temperature-sensitive mutant strain, outer arm deficient 1 (oad1), were reduced at restrictive temperature (37°C for 4 h; Attwell et al., 1992). BB, red; SF, green. All insets show a representative BB and SF. SF length quantitation: n = 300 SFs (30 cells); motility assay, 90 cells. Mann-Whitney test. * denotes P value <0.01. Mean ± SD. Scale bars, 10 µm (cell), 1.3 µm (inset width), 100 µm (swim paths). (C) Schematic illustrating SF length response to varying levels of ciliary force. BB-associated microtubule appendages are not shown.

SFs were previously shown to shorten at low temperatures (Galati et al., 2014). To establish whether SF length responds to reduced ciliary forces independent of temperature effects, SF length was measured when ciliary beating was inhibited. To inhibit ciliary beating, the temperature-sensitive mutant strain, outer arm deficient 1 (oad1; cilia lacking outer arm dynein), was grown at restrictive temperature (37°C for 4 h; Attwell et al., 1992). Elevated temperature reduces swimming rates of oad1 cells by 45% and SF length by 11% (Fig. 2 B). Similarly, 6 h of NiCl2 treatment reduces cell motility and SF length by 67% and 15%, respectively (Fig. S2 A). Thus, SF length is dynamically responsive to elevated and reduced ciliary forces (Fig. 2 C).

Figure S2.

SF length and position during varying levels of ciliary force and the molecular composition of SFs. (A) Cell motility and SF length of WT cells were reduced by NiCl2 treatment (25°C for 6 h). BB, red; SF, green. Insets show a representative BB and SF. SF length quantitation: n = 500 SFs (35 cells); motility assay, 90 cells. Scale bars, 10 µm (cell), 1.3 µm (inset width), 100 µm (swim paths). (B) EM tomographic images of cross-sectional SF–pcMT interface at steady-state (25°C) and elevated ciliary force-induced state (38°C). Electron-dense linkages exist between SFs and pcMT bundles of the anterior BB (cyan arrowheads, enlarged interface). Scale bars, 200 nm. (C) EM tomographic images of longitudinal and cross-sectional SF–epiplasm interfaces at steady-state and elevated ciliary force-induced state (red arrowheads, enlarged interface; magenta arrowheads, SF–epiplasm linkages). Scale bars, 200 nm. (D) Localization of non-SF localizing Tetrahymena SFA proteins. Multiple labeling strategies indicate that TtSfap localizes to oral and cortical cilia (white arrowheads). TtMdlg1p is found in vacuoles. mCh: mCherry. Scale bars, 10 µm (cell), 6.5 µm (inset width). (E) Sequence logos of group-specific consensus sequences in SFA proteins (X, nonconserved residue). (F) Quantitation of Group 2 SF protein distribution along the SF. Top: Length distribution of Group 2 SF proteins. Bottom: Start positions of Group 2 SF proteins relative to BB peak intensity. Number of SFs analyzed: Cro1p, 101; DisAp, 107; Kdf3p, 105; Kdd6p, 93; Bbc39p, 107; Kdf4p, 157; Bbc29p, 115; and Kdf1p, 109. SFs were obtained from ≥60 cells. Mann-Whitney test. * denotes P value <0.01. Mean ± SD.

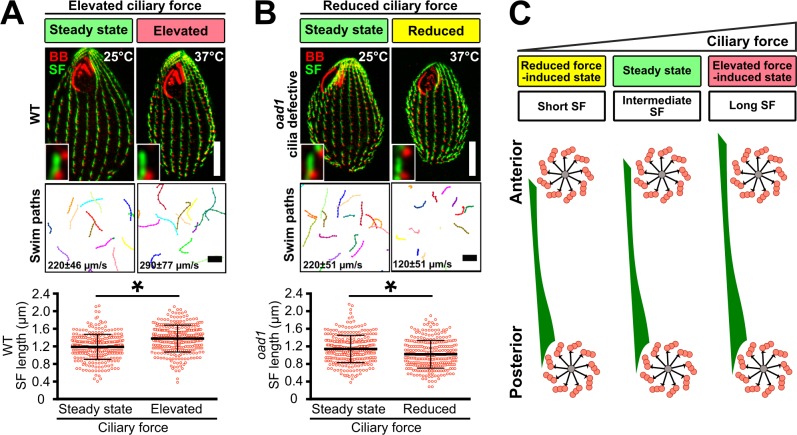

SFs contact pcMTs and the cell cortex

Since SF elongation maintains BB orientation in WT cells and SFs promote BB reorientation in DISA-1 rescue cells (Fig. 1; Galati et al., 2014), we postulated that SF length above a certain threshold promotes SF interactions with structures to facilitate normal BB organization and orientation. Prior work revealed the close proximity and interactions of SFs to BB microtubule appendages and the cell cortex (Iftode et al., 1996; Pitelka, 1961). However, it is not known whether SF interactions persist at different ciliary forces. Here, we investigate SF interactions that promote BB positioning and orientation (Fig. 3 A).

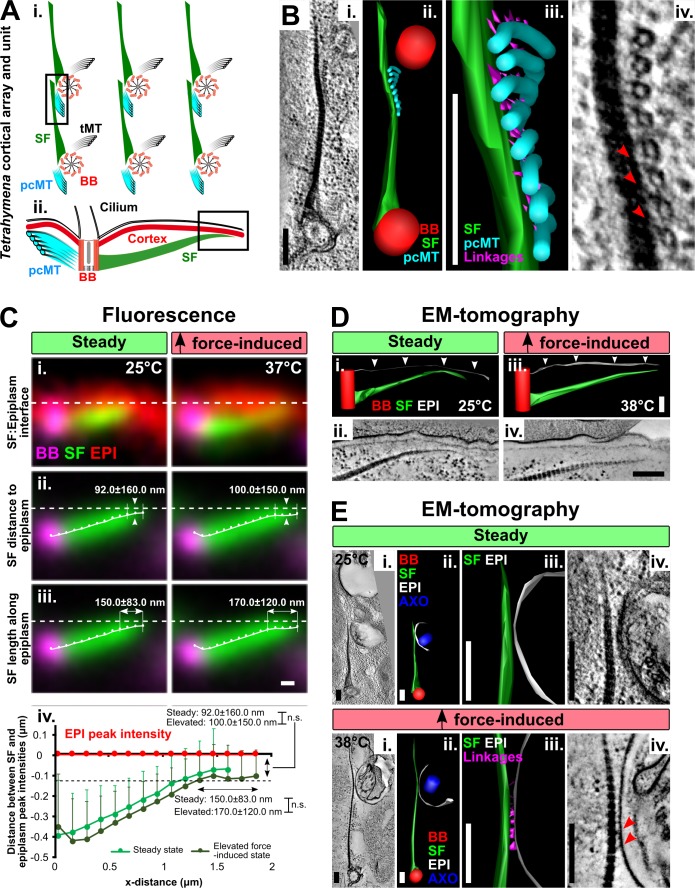

Figure 3.

SFs contact the pcMTs and the cell cortex. (A) i: Schematic of T. thermophila cortical array (cross-sectional interface) illustrating BBs (red) and their associated appendage structures, including SFs (green), pcMTs (cyan) and transverse microtubules (tMT; black). (ii) Schematic depicting the SF–cell cortex longitudinal interface of a single T. thermophila cortical unit. Boxes mark the interfaces of interest. (B) EM tomographic images of the SF–pcMT interface between a pair of BBs at steady-state (25°C). Electron-densities (red arrowheads) link SFs to pcMT bundles (EM tomographic slice: i and iv; model: ii and iii). (C) i: Fluorescence images illustrating the SF position relative to the cell cortex (epiplasm; EpiC-mCherry [EPI]) at steady-state (25°C) and elevated ciliary force-induced state (37°C). (ii and iii) Averaged fluorescence images show that SFs extend toward (y axis) and along (x axis) the epiplasm at both steady-state and elevated force-induced state. BB, magenta; SF, green; EPI, red. Dashed line indicates the peak fluorescence intensities of EpiCp-mCherry. (iv) Quantification of SF position relative to the epiplasm. Black dashed line marks the positions where the SF distal ends start to extend along the epiplasm. Steady-state, n = 104 SFs (53 cells); elevated force-induced state, n = 94 SFs (53 cells). Mann-Whitney test. Mean ± SD. (D) EM tomographic images of the longitudinal SF–epiplasm interface. Linkages were not detected between SFs and the epiplasm (white arrowheads; EM tomographic slice: ii and iv; model: i and iii). (E) EM tomographic images of the cross sections of the SF–epiplasm interface at the ciliary pocket at steady-state (25°C) and elevated ciliary force-induced state (38°C). Electron-dense linkages (red arrowheads) were observed between SFs and the epiplasm only at the elevated force-induced state (EM tomographic slice: i and iv; model: ii and iii). B, D, E: BB, red; SF, green; pcMTs, cyan; epiplasm, white; linkages, magenta; axoneme (AXO), dark blue. Scale bars, 200 nm.

To determine whether SFs interact with the pcMTs of anterior BBs at varying levels of ciliary force, we measured interactions between these structures using EM tomography of WT cells grown at normal (25°C, steady-state) or high ciliary force (38°C, elevated force-induced state). SFs extend anteriorly, crossing the surface of the anterior BBs’ pcMT bundles in close proximity (Fig. 3 Ai). We observed electron densities that link SFs and pcMTs, suggesting that BBs interact with neighboring BBs by forming bridges between SFs and pcMTs (Fig. 3 B and Video 1). These linkages were observed at both normal and high ciliary forces, indicating that, under all conditions measured, SFs physically link neighboring BBs via pcMTs (Fig. 3 B and Fig. S2 B). The SF–pcMT linkage length is longer in the elevated force-induced state (steady-state, 16.0 ± 4.6 nm; elevated force-induced state, 20.0 ± 7.4 nm; mean ± SD; P value = 0.03). Because these linkages were observed under both steady-state and elevated force-induced state, they may be constitutive components required for the preservation of BB organization and orientation (Fig. S2 B).

Video 1.

Serial, tomographic slices and model depicting cross section of SF–pcMT interface at steady-state (25°C). Electron densities link SFs to pcMT bundles. BB, red; SF, green; pcMT, cyan; linkages, purple. Scale bar, 200 nm.

Upon elevated ciliary-beating forces, SFs elongate beyond the anterior BB’s pcMTs. This suggests that the SF distal ends may provide a secondary reinforcing interaction to resist elevated forces from ciliary beating. SFs are oriented toward the cell cortex, suggesting that SFs may have an interacting structure there (Fig. 3 Aii; Allen, 1967; Galati et al., 2014). To quantify the position of SFs relative to the cell cortex, we colocalized SFs with the cortical epiplasm protein EpiCp, fused to mCherry (Williams et al., 1987). Using a semiautomated image analysis routine, the distance between the peak intensities of SFs and EpiCp was quantified. SFs were not detectably closer to the epiplasm upon elongation (Fig. 3, Cii and Civ). However, SFs extended further along the epiplasm during the elevated force-induced state as compared with steady-state (Fig. 3, Ciii and Civ).

To test for SF–cell cortex interactions, we employed EM tomography to monitor SF’s distal end relative to the cortical epiplasm. Consistent with the above fluorescence quantification, SF–epiplasm interactions by longitudinal sections were not observed (Fig. 3 D and Fig. S2 C). However, we did observe electron-dense linkages between elongated SFs and the epiplasm surrounding the ciliary pocket in the elevated force-induced state, but not the steady-state (Fig. 3 E and Videos 2 and 3). While such interactions were not observed at steady-state, we cannot rule out the possibility that they are transient or were not captured. The length of the SF–epiplasm linkage was 22.0 ± 6.0 nm (mean ± SD). Unlike SF–pcMT connections, SF–epiplasm linkages were not observed at all SF–epiplasm interfaces around the ciliary pocket. SF–epiplasm linkages were detected in two of four SF–epiplasm interface tomograms during the elevated force-induced state. This is potentially due to transient interactions between these structures. Thus, SF–epiplasm linkages serve as dynamic, secondary interaction sites to reinforce BB organization and orientation when cilia and BBs experience greater mechanical forces.

Video 2.

Serial, tomographic slices and model depicting cross section of SF–epiplasm interface at steady-state (25°C). BB, red; SF, green; epiplasm, white; linkages are absent. Scale bar, 200 nm.

Video 3.

Serial, tomographic slices and model depicting cross section of SF–epiplasm interface at elevated force-induced state (38°C). Electron densities link SF to the epiplasm. BB, red; SF, green; epiplasm, white; linkages, purple. Scale bar, 200 nm.

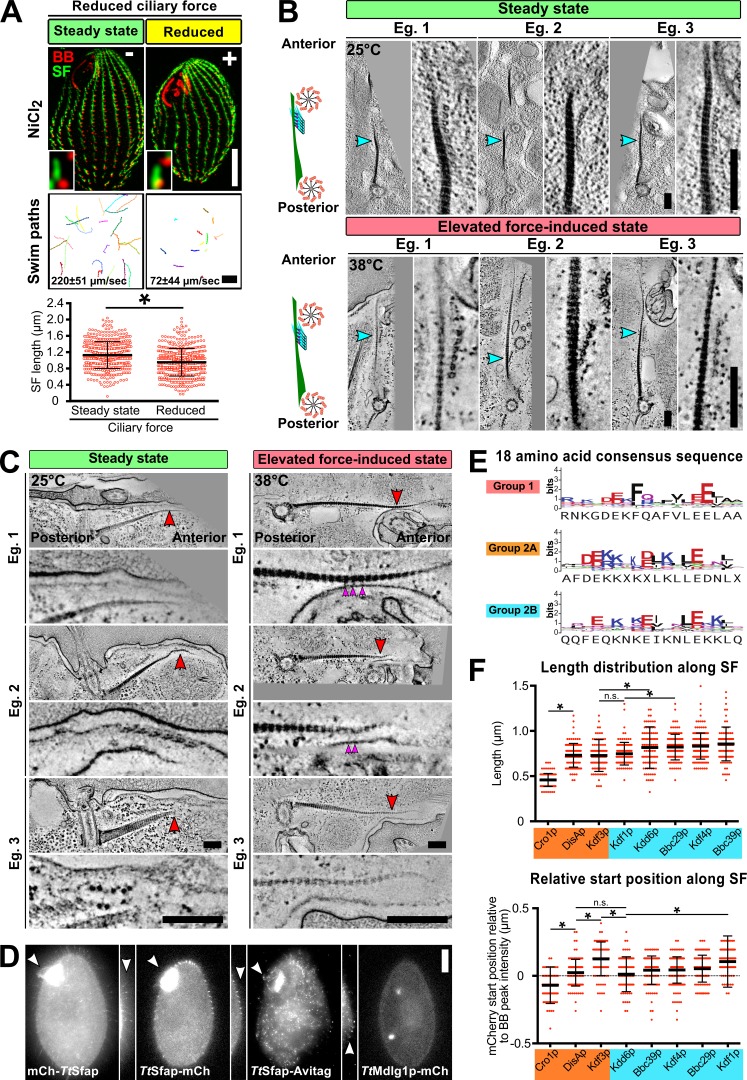

SFs are composed of a family of uniquely localized SF-assemblin (SFA) components

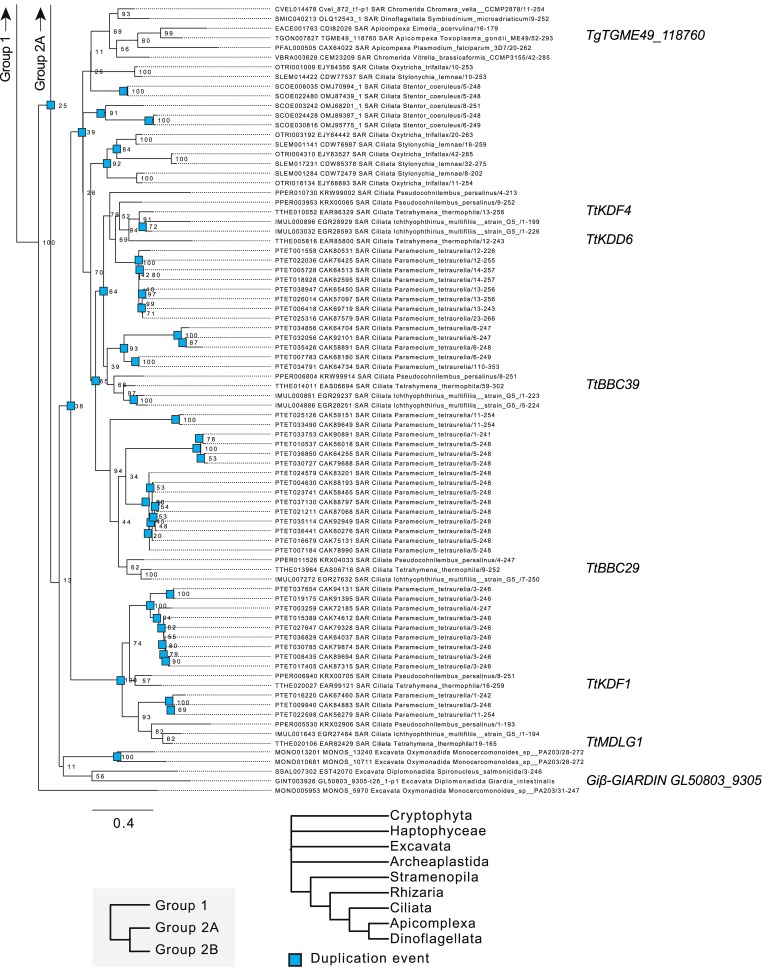

To determine the molecular composition of SFs, we performed phylogenetic analysis on the known SF gene DISA-1 to identify similar genes. As DisAp belongs to the SFA family of proteins, we searched for SFA proteins across a broad set of eukaryotic species and found that SFA homologues are found exclusively among protists and Diphoda algae (Fig. 4 A and Figs. S4, S5, and S6; Galati et al., 2014). Moreover, these organisms possess variable numbers of SFA homologues, possibly resulting from whole-genome duplication and/or gene duplication events (Figs. S4, S5, and S6; number of SFA homologues: Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, 1; T. thermophila, 10; and Paramecium tetraurelia, 72). T. thermophila SFA homologues fall into three orthologous clades, which we designate Group 1, Group 2A, and Group 2B. Group 1 and Group 2 SFA proteins can be distinguished by the relative positions of an 18–amino acid consensus sequence (Fig. 4 B). This sequence appears near the N-terminus of Group 1 SFA proteins, but it is found on the C-terminus in Group 2 (Fig. 4 B and Fig. S2 E). In addition, Group 2B SFA proteins possess a single, conserved proline residue that distinguishes them from the Group 2A proteins (Fig. 4 B). Hence, we hypothesized that T. thermophila SFA proteins diverged and sub-functionalized.

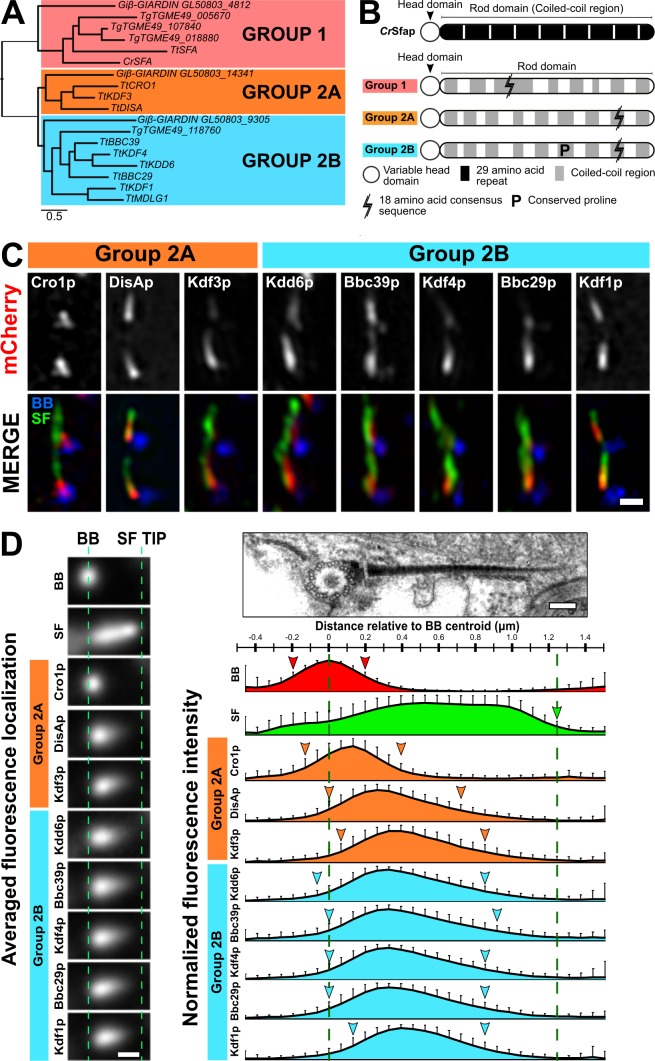

Figure 4.

SFs are composed of a family of uniquely localized SFA components. (A) Simplified phylogenetic tree depicting the evolutionary relationships between SFA homologues of selected algae and protists. SFA homologues fall into three evolutionarily distinct groups. Tt: T. thermophila; Cr: C. reinhardtii; Gi: G. intestinalis; Tg: T. gondii. (B) Domain comparison of previously characterized green algae SFA protein (C. reinhardtii; Lechtreck and Silflow, 1997) and unique sequence features identified in SFA orthologous groups. (C) SIM imaging shows the unique localization of T. thermophila Group 2 SF proteins. BB, blue; SF, green; Group 2 SF proteins, white and red. Scale bar, 500 nm. (D) Left: Averaged fluorescence localization of T. thermophila Group 2 SF proteins. Number of SFs analyzed: Cro1p, 101; DisAp, 107; Kdf3p, 105; Kdd6p, 93; Bbc39p, 107; Kdf4p, 157; Bbc29p, 115; and Kdf1p, 109. SFs were gathered from ≥60 cells. Scale bar, 500 nm. Right: Schematic illustrating the relative localization of T. thermophila Group 2 SF proteins along the SF. BB, red; SF, green; Group 2A, orange; Group 2B, cyan. Green dashed lines mark the BB centroid and SF distal end. Arrowheads mark the start and end positions of the Group 2 SF proteins as defined by 30% from peak fluorescence intensity. SF start position is unmarked due to overlapping fluorescence signals from posterior SFs. Error bars indicate SD. Scale bar, 125 nm.

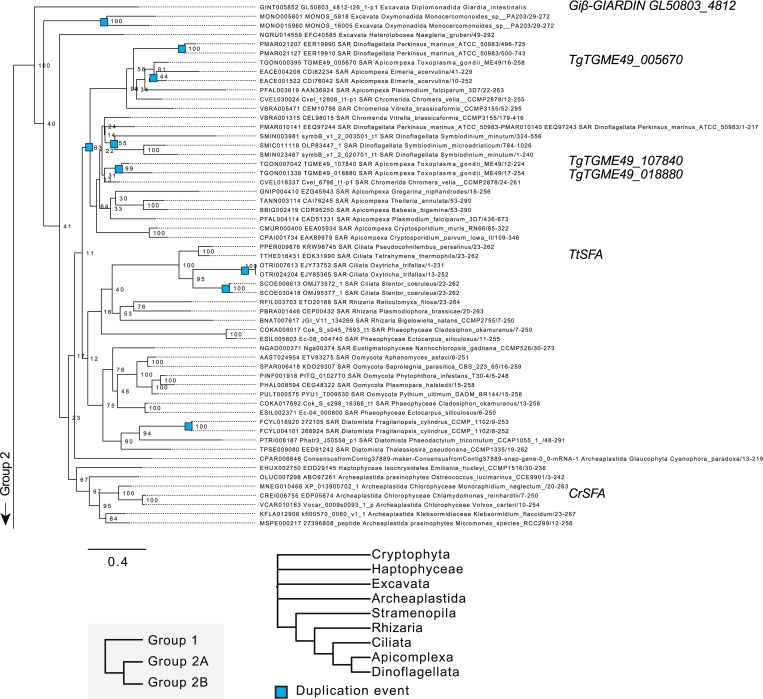

Figure S4.

Phylogenetic analysis of Group 1 SFA homologues among ciliates and algae. Rooted phylogenetic tree of 205 SFA protein sequences gathered from 50 species of protists and algae. Figure only indicates SFA proteins that belong to the Group 1 clade.

Figure S5.

Phylogenetic analysis of Group 2A SFA homologues among ciliates and algae. Rooted phylogenetic tree of 205 SFA protein sequences gathered from 50 species of protists and algae. Figure only indicates SFA proteins that belong to the Group 2A clade.

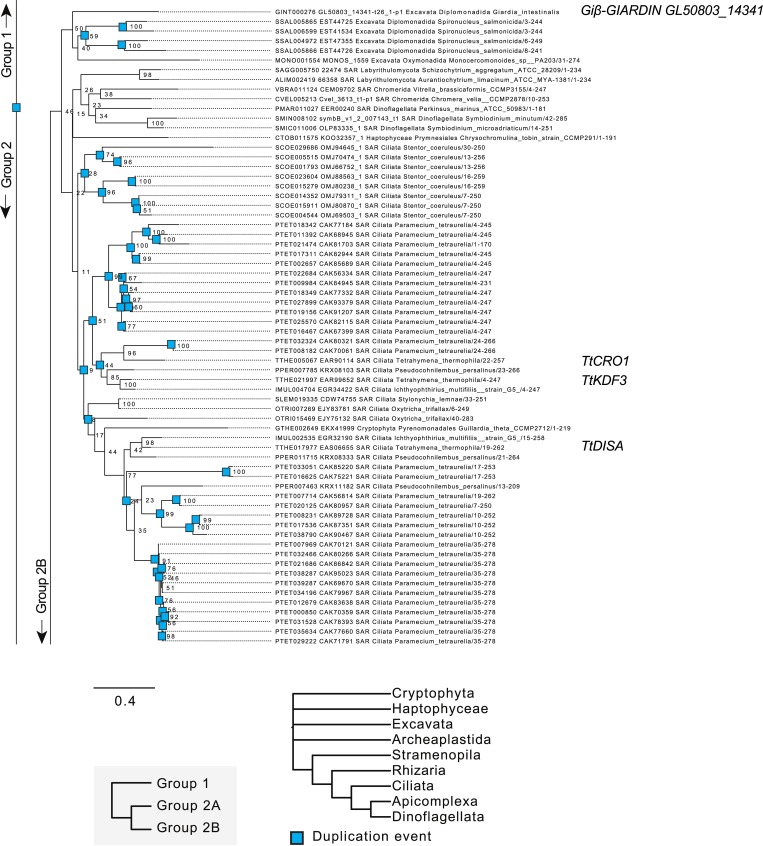

Figure S6.

Phylogenetic analysis of Group 2B SFA homologues among ciliates and algae. Rooted phylogenetic tree of 205 SFA protein sequences gathered from 50 species of protists and algae. Figure only indicates SFA proteins that belong to the Group 2B clade.

To investigate whether T. thermophila SFA proteins localize to SFs, we fluorescently tagged these proteins in T. thermophila cells. From our localization analysis, we discovered that the Group 1 SFA homologue (Entrez Gene accession no. TTHERM_00263290) localizes to cilia (Fig. S2 D), which is surprising given that its green algae homologue localizes to SFs (Lechtreck and Melkonian, 1991). Group 2 SFA proteins (Cro1p, DisAp, Kdf3p, Kdd6p, Bbc39p, Kdf4p, Bbc29p, and Kdf1p) localize to SFs (Galati et al., 2014; Chalker, D., personal communication). Using endogenously tagged genes under native promoters, we showed with SIM imaging that 8 out of 10 of the SFA proteins distinctly localize within SFs (Fig. 4 C). Thus, T. thermophila SF proteins exhibit unique phylogenetic and localization profiles.

We developed a semiautomated, image-averaging pipeline to quantify the localization pattern for each T. thermophila SF protein (Fig. 4 D). Using BBs and SFs as fiducial marks, fluorescent images of each SF protein were aligned and averaged. To quantify the relative position and distribution of each SF protein along the SF, the fluorescent signal was measured. SF proteins localize to unique domains along the SF length (Fig. 4 D, left; and Fig. S2 F). Among Group 2A proteins, Cro1p and DisAp localize to the SF base, while Kdf3p localizes more distally. Group 2B SF proteins (Kdd6p, Bbc39p, Kdf4p, Bbc29p, and Kdf1p) localize along the SF length (Fig. 4 D, right). Because these components do not localize along the entire SF length, additional proteins likely form the SF distal ends. Coupled with the unique sequence features in each T. thermophila SFA group, it will be interesting to explore how these proteins influence SF assembly, length regulation, and function.

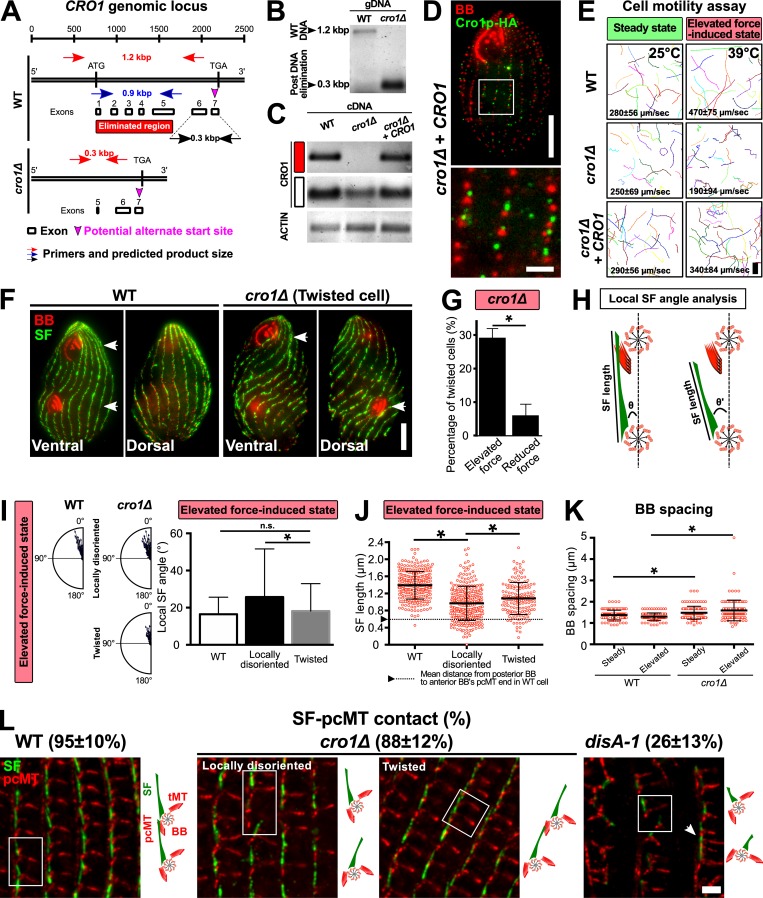

Cro1p promotes elevated ciliary force-induced SF elongation

The localization of the ciliary row organizing-1 protein (Cro1p) to the SF base suggests that it may nucleate SFs, link SFs to BBs, and/or influence SF length (Fig. 4, C and D; Entrez Gene accession no. TTHERM_000354599). The latter hypothesis is consistent with the proximal localizing SF component DisAp, which, when disrupted, causes SF shortening by ~60% (Fig. 1; Galati et al., 2014). To investigate the effect of Cro1p loss on SFs, T. thermophila CRO1 was knocked out in the T. thermophila macronucleus using CoDel (Hayashi and Mochizuki, 2015). Successful CRO1 knockout was confirmed by the loss of CRO1 genomic DNA and CRO1 transcripts (Fig. S3, A–C). While exons 1–5 were eliminated, a partial transcript containing exons 6 and 7 was detected (Fig. S3 C, white box). Based on an alternate transcriptional start site within exon 7, expression of a truncated 20–amino acid Cro1p cannot be excluded. A cro1Δ+CRO1 rescue strain was created by reintroducing CRO1 into the cro1Δ cells (Fig. S3 D).

Figure S3.

Cro1p promotes elevated ciliary force-induced SF elongation. (A) Schematic illustrating the genomic locus of CRO1 and the site that was targeted for DNA elimination (red box). (B) PCR assessment confirmed DNA elimination at the targeted site of CRO1 genomic locus. (C) RT-PCR assessment confirmed the absence of CRO1 transcript expression in cro1Δ cells (red box). A partial CRO1 transcript was expressed downstream of the DNA-eliminated region (white box). (D) Expression and localization of Cro1p-HA in cro1Δ rescue strain. BB, red; Cro1p-HA, green. Scale bars, 10 µm (cell), 2 µm (inset). (E) Motility assay of WT, cro1Δ, and cro1Δ rescue cells at steady-state and elevated force-induced state. Scale bar, 100 µm. Motility assay, 90 cells. (F) Mispositioned oral structure in dividing and twisted cro1Δ cells. White arrowheads mark matured and developing oral structures. Scale bar, 10 µm. (G) Twisted cell phenotype is rescued at reduced ciliary forces. To reduce ciliary forces, cro1Δ cells were enriched for the twisted cell phenotype at 39°C for 24 h before they were temperature shifted to 25°C. Percentage of twisted cells was assessed 24 h after temperature shift. (H) Schematic analysis to quantify SF length and local SF angle (θ) relative to the anterior BB. (I) Local SF angle is wider for BBs that exhibit local disorientation as compared to BBs within twisted rows at the elevated force-induced state. (J) Locally disoriented BBs possess shorter SFs than BBs in twisted rows. n ≥ 285 SFs (≥37 cells). (K) BB spacing is marginally increased in cro1Δ cells at steady-state and elevated force-induced state. n ≥ 120 (≥30 cells). (L) Frequency of SF–pcMT contacts in WT, cro1Δ, and disA-1 cells. Schematic illustrates the position and orientation of two BBs within a region of interest (white boxes). White arrowhead marks BB clusters in disA-1 mutants. n = 240 SFs (24 cells). Scale bar, 2 µm. tMT, transverse microtubule. Mann-Whitney test. * denotes P value <0.01. Mean ± SD.

At steady-state, cro1Δ cells swim ~11% slower than WT cells (Fig. S3 E). At elevated forces, cro1Δ cells swim 60% slower than WT cells (Fig. S3 E). Thus, cro1Δ, like disA-1 mutants, impedes cellular swimming behavior when ciliary beating forces are elevated.

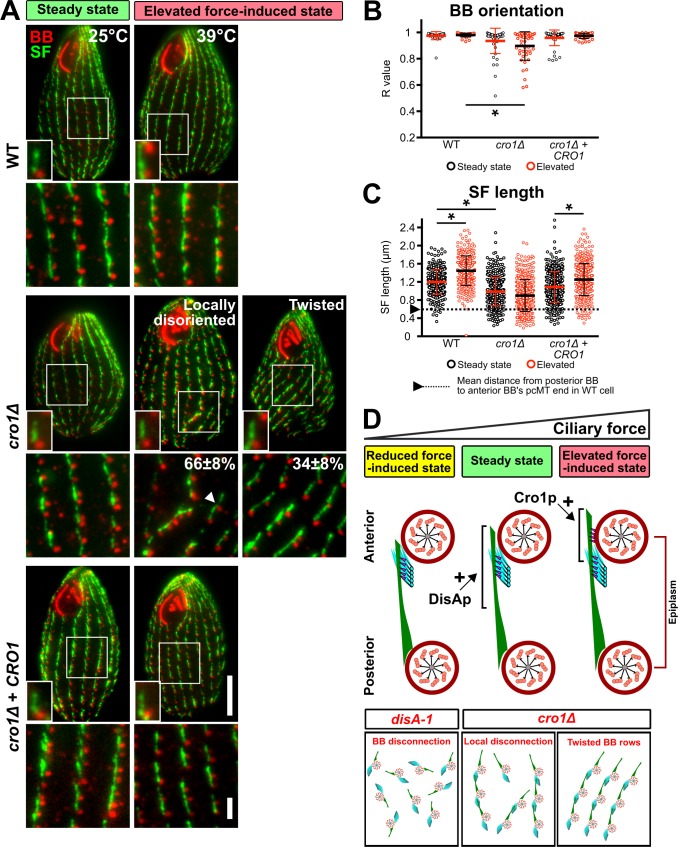

To test whether the reduced cell motility in cro1Δ cells results from BB disorientation, we visualized BBs in cro1Δ cells. At steady-state, most BBs in cro1Δ cells were oriented. However, BB disorientation is increased at the elevated force-induced state (Fig. 5, A and B). Moreover, BB spacing is slightly increased in cro1Δ cells grown at elevated force-induced state as compared with WT cells, which retain normal BB spacing at both steady-state and elevated force-induced state (Fig. S3 K). Compared with disA-1 mutants, cro1Δ cells exhibit intermediate BB disorientation (Fig. S3 L; Galati et al., 2014). We next tested whether Cro1p loss impacts SF length (Fig. 5 C). cro1Δ SFs are 18% shorter than WT SFs during steady-state and remain short at the elevated ciliary force-induced state (Fig. 5, A and C). Thus, Cro1p loss results in shorter SFs and an inability to lengthen SFs when ciliary forces are increased. Interestingly, the extent of the SF length defect in cro1Δ and disA-1 cells correlates with the extent of BB disorientation (Fig. 5 D and Fig. S3 L; elevated force-induced state: WT, 1.45 ± 0.33 µm; cro1Δ, 0.90 ± 0.35 µm; disA-1, 0.44 ± 0.23 µm; mean ± SD). Unlike disA-1 mutants, SFs in cro1Δ cells are long enough to establish SF–pcMT interactions and promote normal BB orientation at steady-state (Fig. 5, B and C; and Fig. S3 L). Hence, this further supports the importance of SF length in ensuring proper BB orientation (Fig. 5 D).

Figure 5.

Cro1p promotes elevated ciliary force-induced SF elongation. (A) Representative images of WT, cro1Δ, and cro1Δ rescue cells during steady-state (25°C) and elevated force-induced state (39°C for 24 h). More cro1Δ cells exhibit local BB disorientation (white arrowhead) and twisted BB rows compared with WT cells at elevated force-induced state. The percentage of each phenotype is calculated based on cro1Δ cells that exhibit BB disorientation. All small insets show a representative BB and SF. Scale bars, 10 µm (cell), 1.3 µm (inset width), 2 µm (BB rows inset). (B) Quantification of BB orientation (R value) of WT, cro1Δ, and cro1Δ rescue cells. cro1Δ cells exhibit BB disorientation at elevated force-induced state. (C) Quantification of SF length of WT, cro1Δ, and cro1Δ rescue cells. SF length of cro1Δ cells failed to elongate at the elevated force-induced state. Arrowhead and dotted line mark the minimal SF length that is required for SF–pcMT interactions. n ≥ 350 SFs (≥40 cells). Mann-Whitney test. * denotes P value <0.01. Mean ± SD. (D) Model depicting how SF base proteins, DisAp and Cro1p, influence SF length. Loss-of-function of these proteins either affect primary (SF–pcMT) or secondary (SF–cell cortex) interactions, and lead to varying degrees of BB disorganization and disorientation. A and D: BB and epiplasm, red; SF, green; pcMTs, cyan; linkages, magenta.

At steady-state, the majority of cro1Δ cells (76 ± 9%; mean ± SD) exhibit normal BB orientation. The remaining cells exhibit either individual BBs that are locally disoriented and disconnected from their neighboring BBs in ciliary rows (locally disoriented cells: 20 ± 7%; mean ± SD) or connected BBs that are positioned within twisted BB rows relative to the cell’s anterior–posterior axis (twisted cells: 4 ± 2%; mean ± SD). The elevated force-induced state resulted in a larger proportion of cro1Δ cells with BB disorientation (Fig. 5, A and B; normal BB orientation, 10 ± 8%; BB disorientation, 90 ± 8% [locally disoriented, 66 ± 8%; twisted cells, 34 ± 8%], mean ± SD). This suggests that SF–pcMT interactions alone are insufficient to maintain BB orientation under the elevated force-induced state. Moreover, it reveals that proteins that localize to the SF base possess distinct SF functions, whereby DisAp is required for ensuring proper SF length to achieve SF–pcMT interactions and Cro1p is required for elevated force-induced SF elongation (Fig. 5 D and Fig. S3 L). Based on the distinct functions of DisAp and Cro1p, we hypothesized that the double knockout of DISA-1 and CRO1 will lead to cells that do not assemble SFs. However, we failed to obtain clones of the double knockout strain. This suggests that the loss of function of both proteins is synthetically lethal.

The twisted cells are reminiscent of the twisty and screwy mutants in T. thermophila and P. tetraurelia, respectively (Fig. S3 F; Frankel, 2008; Jerka-Dziadosz et al., 1995; Whittle and Chen-Shan, 1972). Reduction of ciliary forces by shifting cro1Δ cells from 39°C to 25°C for 24 h rescued twisted BB rows back to WT configuration, indicating that twisted BB rows arise from elevated ciliary forces (Fig. S3 G). Because SFs are generally oriented in cro1Δ cells with a few examples of local disorientation, we predicted that locally disoriented BBs possess shorter SFs that cause BBs to disconnect from their anterior neighbor. Indeed, locally disoriented BBs possess shorter SFs than BBs in twisted BB rows, which leads to BB disconnection (Fig. S3, H–J and L). Cells with twisted BB rows, on the other hand, possess SFs that are long enough to establish and maintain BB connections, but they are unable to elongate at the elevated force-induced state (Fig. S3, H–J and L). We postulate that this makes BB rows more susceptible to asymmetric ciliary forces and causes BB rows to deviate from the cell’s anterior–posterior axis (Fig. 5 A and Fig. S3, F and L; Cheung and Jahn, 1976). Collectively, this suggests that Cro1p ensures proper SF lengthening to establish secondary SF–cell cortex interactions during elevated ciliary forces (Fig. 5 D).

Conclusions

Here, we show that BB-associated SFs are ciliary force-responsive structures that attain unique length states to organize multi-ciliary arrays. To stabilize the positioning and orientation of BBs, SFs establish primary (steady-state) and secondary (elevated force-induced state) interactions with the anterior BB pcMTs and the cell cortex, respectively. This facilitates BB connections to propagate metachronal ciliary beating for cellular motility. Consistent with the sub-functionalization of SF components, we discovered that one proximally localized SF protein, DisAp, maintains steady-state SF lengths while a second proximal SF protein, Cro1p, is required for elevated force-induced SF elongation. We show that SF length maintenance and elongation promote attachments between neighboring BBs and to the cell cortex to ensure proper BB positioning and orientation.

Materials and methods

T. thermophila culture

T. thermophila cells were grown in 2% SPP media (2% proteose peptone, 0.2% glucose, 0.1% yeast extract, and 0.003% Fe-EDTA). For studies under cycling conditions, cells were analyzed at mid-log phase (4–5 × 105 cells/ml) as determined using a Coulter Counter Z1 (Beckman Coulter). For studies under noncycling conditions, cells were arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle by washing and culturing in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, for 48 h. Cell concentration was kept at 4–5 × 105 cells/ml. For microscopy experiments, analyses were restricted to nondividing cells as judged by those lacking a developing oral structure.

To study BB reorientation, DISA-1 rescue cells were grown in SPP media at high ciliary forces (37°C for 24 h) to exacerbate BB disorientation. Next, cells were grown under cycling condition (SPP media) or noncycling condition (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) at steady-state (25°C). Under both conditions, experiments were performed with and without GFP-DisAp expression. For the single cell rescue experiment, DISA-1 rescue cells were subjected to the same BB disorientation regimen (high ciliary forces, 37°C for 24 h) before they were isolated and grown under cycling condition (SPP media) with and without GFP-DisAp expression. Cells were collected at the respective time points, fixed for immunofluorescence assay, and imaged. The assessment criteria for the rescue of DISA-1 rescue isolates are normal (i) cell morphology and (ii) swim path.

To expose cultures to reduced ciliary forces, T. thermophila cells were propagated in 2% SPP supplemented with 3 mM NiCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich), which was added directly to the culture vessel from a 1 M stock. Dynein-dependent ciliary beating is inhibited by NiCl2, which blocks plasma membrane calcium channels and directly inhibits dynein motors (Larsen and Satir, 1991). For experiments that require an extended duration of NiCl2 treatment, a lower dosage of NiCl2 (2 mM) was used.

Plasmids and T. thermophila strain construction

The BB reorientation assay was performed using the DISA-1 rescue strain previously described (Galati et al., 2014). To initiate rescue in the DISA-1 rescue strain, DISA-1 expression was induced via a cadmium (II) chloride-driven promoter.

Previously reported T. thermophila strains overexpressing SFA proteins (Cro1p, Kdf3p, Kdd6p, Bbc39p, Kdf4p, Bbc29p, and Kdf1p) localize to the SF (www.suprdb.org; Chalker, D., personal communication). In this study, we created endogenously tagged genes under native promoters. WT T. thermophila cells (B1868) that express mCherry-tagged SF proteins were created using the p4T2-1–mCherryLAP construct (Winey et al., 2012). Briefly, the mCherryLAP cassette integrates at the endogenous target gene locus, and gene expression remains under the control of the endogenous promoter. Transformed cells were selected for paromomycin resistance and assorted to at least 2 mg/ml of paromomycin. For information on oligo design, please refer to Table S1.

Phylogenetic analysis

We gathered an initial set of SFA-related protein sequences from our in-house orthology dataset by running Orthofinder 2.1.2 (Emms and Kelly, 2015) on a curated set of 169 eukaryotic proteomes with DIAMOND (Buchfink et al., 2015). To identify sequences that may have been missed, we constructed a custom hidden Markov model with the HMMER package (Eddy, 2011) using merged orthologous group sequences that were aligned with MAFFT (v7.271; Katoh and Standley, 2013). The final alignment was constructed by aligning the inclusive set of sequences with CulstalOmega (v1.2.1; Sievers et al., 2011), and curated by removing variable N- and C-termini sequences. The final set contains 205 SFA sequences (supplemental data file 1). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using RaxML (v8.2.4; Stamatakis, 2014) and MrBayes (v3.2.6; Ronquist et al., 2012). Both algorithms generated phylogenetic trees that are in agreement. Raw data are available on request. Since a suitable outgroup could not be determined, the final trees were rooted such that each branch contains eukaryotic-wide taxonomic distributions. Coiled-coil regions were predicted during manual curation of SFA protein sequence alignment (Fig. 4 B).

Immunocytochemistry

BB and SF labeling

For immuno-cytochemical analyses of BBs and SFs, 7 × 105 cells were pelleted at 600 g in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and fixed for 20 min with 1 ml of 70% ethanol + 0.1% Triton X-100 on ice. Cells were washed thrice with 10 mM PBS, pH 7.4, and blocked in 0.5% BSA/PBS for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were immunostained by incubating in primary antibody (mouse anti-SF [5D8], 1:500; rabbit anti-centrin [BB], 1:500; Jerka-Dziadosz et al., 1995; Stemm-Wolf et al., 2005) overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 or 594, 1:2,000; goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647, 1:2,000; Invitrogen) for a 2-h incubation at 4°C. Cells were mounted in Citifluor mounting media using #1.5 coverslips and sealed with nail polish. All antibodies were diluted in 0.5% BSA/PBS. Cells were washed thrice with 0.5% BSA/PBS after primary and secondary antibody incubations.

SF and pcMT labeling

For immuno-cytochemical analyses of SFs and pcMTs, 7 × 105 cells were pelleted at 600 g in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and fixed for 5 min with 1 ml of 3.2% PFA/PHEM + 0.24% Triton X-100 (PHEM, 60 mM Pipes, 25 mM Hepes, 10 mM EGTA, and 2 mM MgCl2, pH 6.9) at 25°C. Next, cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold 0.5% Triton X-100 (PHEM) for 10 min on ice at 4°C. Cells were washed thrice with PHEM and blocked in 0.5% BSA/PHEM for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were immunostained by incubating in primary antibody (mouse anti-SF [5D8], 1:500; rabbit anti-acetylated α-tubulin lysine 40 [D20G3; Cell Signaling Technology], 1:100) overnight at 4°C followed by secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 or 647, 1:2,000; goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594, 1:2,000; Invitrogen) for a 2-h incubation at 4°C. Cells were mounted in Citifluor mounting media using #1.5 coverslips and sealed with nail polish. All antibodies were diluted in 0.5% BSA/PHEM. Cells were washed thrice with 0.5% BSA/PHEM after primary and secondary antibody incubations.

Light microscopy

Imaging experiments (Figs. 3 C, 4 D, 5 A; S1, A and F–I; S2 D, and S3, D and F) were performed with an inverted widefield microscope (Ti Eclipse; Nikon). A 100× Plan-Apochromat (NA 1.4) objective lens (Nikon) was used. Images were captured with a z-step size of 300 nm using a scientific complementary metal-oxide semiconductor camera (Zyla; Andor Technology).

Super-resolution localization experiments of SF–pcMT interactions (Figs. S1 C and S3 L) and Group 2 SF proteins (Fig. 4 C) were performed via SIM with the Nikon 3D SIM system (Ti 2 Eclipse). A 100× total internal reflection fluorescence objective (NA 1.45) was used. Images were captured with a complementary metal-oxide semiconductor camera (Orca-Flash 4.0; Hamamatsu) with a z-step size of 300 nm. Raw SIM images were reconstructed by the image stack reconstruction algorithm (Nikon Elements).

Confocal microscopy was performed using an inverted microscope (Ti Eclipse) with a 100× Plan-Apochromat (NA 1.43) objective lens (Nikon) and a swept field confocal scan head with the 35-µm slit mode (Prairie Technologies). Images were captured with a charge-coupled device camera (iXon X3; Andor Technology). Confocal images were also acquired with the A1 confocal laser microscope (Nikon). All images were acquired with Nikon Elements with a z-step size of 300 nm at room temperature (Figs. 1, 2, S1 E, and S2 A).

Electron tomography

Cells were prepared for electron tomography as previously described (Giddings et al., 2010; Meehl et al., 2009). Cells were gently spun into 15% dextran (molecular weight 9,000–11,000 D; Sigma-Aldrich) with 5% BSA in 2% SPP. A small volume of concentrated cells was transferred to a sample holder and high-pressure frozen using a Wohlwend Compact 02 High Pressure Freezer (TechnoTrade International). After low-temperature freeze substitution in 0.25% glutaraldehyde and 0.1% uranyl acetate in acetone, cells were slowly infiltrated with Lowicryl HM20 resin. Serial thick (250–300 nm) sections were cut using a Leica UCT ultramicrotome. The serial sections were collected on Formvar-coated copper slot grids and poststained with aqueous uranyl acetate followed by Reynold’s lead citrate.

Dual-axis tilt series (−60 to +60°) of T. thermophila cells were collected on a FEI Tecnai 300kV FEG-TEM (FEI). Images were acquired using the SerialEM acquisition program (Mastronarde, 2005) with a Gatan OneView (4k × 4k) camera. Serial section tomograms of T. thermophila cortical structures were generated using the IMOD 4.9 software package (Kremer et al., 1996; Mastronarde, 1997). Three tomograms for each interface of interest were analyzed.

T. thermophila motility measurements

T. thermophila cell motility was imaged on an inverted widefield microscope using a 20× objective lens (Ti Eclipse; Nikon). Each movie duration is 2.5 s (exposure duration, 50 ms; frame rate, 20 frames per second). To quantify swim rates, the relative displacement of the anterior or posterior pole of cells was tracked for 500 ms via the FIJI MTrackJ plugin (Meijering et al., 2012). Analyses were restricted to cells that swam along the same x y plane.

Image analysis: SF length, BB orientation (R value), distance between posterior BB and anterior BB’s pcMT distal end, and frequency of SF–pcMT contact

SF length and BB orientation were quantified by a semiautomated strategy previously described (Galati et al., 2014). Briefly, all images were first uniformly contrasted before quantitation. SF length was measured via the freehand tool (Fig. 1 B). To compute BB orientation (R value), which reflects the variance of BBs’ orientation relative to the cell’s anterior–posterior axis, the ORIANA circular statistics suite (Kovach Computing Services) was used. Based on the displacement of the SF from its associated BB and the anterior pole of the cell, an angular measurement was obtained (Fig. 1 B). For each T. thermophila cell, at least five angular measurements were gathered from SFs that are positioned within a 10-µm box placed at the cell’s medial region. Using the angular measurements, the mean vector and length of the mean vector (R value) were calculated. The BB orientation in each cell is represented by a single R value. An R value of 1 indicates that SFs are uniformly oriented toward the anterior pole of the cell. Conversely, an R value of 0 indicates that SFs are randomly oriented. The discrepancy in R values between our prior publication and this paper is attributed to slight differences in SF sampling between experimentalists (Galati et al., 2014). Consistency of R-value measurements was ensured in this paper. Cell level SF length:BB orientation correlation analysis was performed by correlating the average SF length within the same cell to its corresponding R value. Individual BB level SF length:BB orientation correlation analysis was performed by correlating the SF length of an individual BB to its SF’s angular displacement from the anterior pole of the cell.

To quantitate the position of the anterior BB’s pcMT distal end (relative to the posterior BB), we colocalized SFs with pcMTs and measured the distance from the pcMT distal end to the posterior BB (determined by the position of SF base; Fig. 1 B). To measure the frequency of SF–pcMT contacts, we determined the criteria for contact to be an overlap of the SF and pcMT fluorescence signals by at least 220 nm (2 pixels). Both analyses were restricted to SFs and pcMTs found at the cell’s medial region.

Image analysis: Quantification of SF position relative to the cell cortex (epiplasm)

Fluorescence quantification of SF position relative to the cell cortex was performed by a semiautomated strategy that utilizes the FIJI macro scripting language and plugins (Schindelin et al., 2012). Image stacks colocalized for BBs, SFs, and the cell cortex (marked by EpiC-mCherry) were preprocessed to generate maximum projections (three slices; z-step size = 300 nm [FIJI Z Project; Max Intensity plugin]). All analyses were restricted to BBs and their associated SFs that were found in the medial region of the cell. To visualize the longitudinal SF–cell cortex interface, BBs positioned at the side of T. thermophila cells were selected. Each BB unit, which includes a BB, its associated SF, and the nearby epiplasm, is cropped as an individual image (5.2 µm × 5.2 µm) for further processing. The average distance between the SF and the epiplasm is measured based on the peak intensities of the SF (distal 25th percentile of its total length; labeled with mouse anti-SF [5D8]) and the epiplasm marker EpiC-mCherry (FIJI Plot Profile plugin). The average SF length that spans along the epiplasm is quantified based on SF peak fluorescence intensities that fall within 130 nm (2 pixels) from the EpiC-mCherry peak fluorescence intensities.

Image analysis: Fluorescence image averaging

Fluorescence image averaging was performed by a semiautomated strategy that utilizes the FIJI macro scripting language and plugins (Schindelin et al., 2012). Image stacks were preprocessed to generate maximum projections of the T. thermophila cell side that is nearer to the glass cover (11 slices; z-step size = 300 nm [FIJI Z Project; Max Intensity plugin]). All analyses were restricted to BBs and their associated SFs that were found in the medial region of the cell. Each selected BB and its associated SF (SF length: 1.1–1.3 µm) is cropped as an individual image (5.2 µm × 5.2 µm) for further processing.

Next, selected BBs and SFs served as fiducial marks for 2D alignment. To align BBs, the brightest pixel within each BB is identified by Gaussian blur (FIJI Gaussian Blur plugin; σ = 2 pixels). Based on the position of the brightest pixel in each BB, BBs were aligned through the FIJI Translate plugin. Next, a second alignment step based on the SF distal end was performed. To align SFs along the same axis, SFs were rotated (relative to the BB’s brightest pixel) using the FIJI Rotate plugin.

Prior to fluorescence image averaging, the local background fluorescence intensities (defined by the regions directly adjacent to the signal of interest) were measured, averaged, and subtracted from each respective channel. Next, all peak intensities for each respective channel were normalized to 1. Finally, fluorescence images of aligned BBs and SFs were averaged using the FIJI Average Intensity plugin.

To measure the average length distributions and relative start positions of Group 2 SF proteins along the SF, we measured the fluorescence distribution of each mCherry-tagged Group 2 SF protein (FIJI Plot Profile plugin). To quantify the length of SF protein-mCherry localization along the SF, a fluorescence-based criterion was used (intensity value ≥30% from the peak fluorescence intensity qualifies for length measurement). The start positions of Group 2 SF protein-mCherry along the SF are determined based on their relative positions from the BB centroid. The same fluorescence-based criterion was applied.

Statistical analysis

All datasets were assessed for normal distribution using Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Student’s t test was performed on normally distributed datasets. Mann-Whitney test was performed on datasets that do not conform to normal distribution. Tests for significance were unpaired and two-tailed. Categorical datasets were analyzed using χ2 test. All error bars indicate SD. Statistical significance was set at P value <0.01. All analyses were performed on samples obtained from three independent experiments.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that SF elongation promotes BB reorientation. Fig. S2 shows SF length and position during varying levels of ciliary force and the molecular composition of SFs. Fig. S3 shows that Cro1p promotes elevated ciliary force-induced SF elongation. Figs. S4, S5, and S6 show phylogenetic analysis of SFA homologues among ciliates and algae; rooted phylogenetic trees of 205 SFA protein sequences gathered from 50 species of protists and algae; and three taxonomically diverse clades are identified and designated as Group 1, Group 2A, and Group 2B. Figs. S4, S5, and S6 show Group 1, Group 2A and Group 2B, respectively. Video 1 shows serial, tomographic slices and model depicting cross section of SF–pcMT interface at steady-state (25°C). Video 2 demonstrates serial, tomographic slices and model depicting cross section of SF–epiplasm interface at steady-state (25°C). Video 3 shows serial, tomographic slices and model depicting cross section of SF–epiplasm interface at elevated force-induced state (38°C). Table S1 provides tabulation of oligo sequences used for fluorescent protein tagging and the functional study of T. thermophila Cro1p. The supplemental data file 1 provides multiple sequence alignment of 205 SFA protein sequences from 50 protist and algae species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Pearson laboratory for the helpful discussions during the course of this project. In addition, we express our gratitude to Nick Galati (Western Washington University), who aided in the development of image analysis tools used in this study. We also thank Doug Chalker (Washington University) for helpful discussions on T. thermophila SF-localizing proteins. EM was performed at the University of Colorado, Boulder EM Services Core Facility in the Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology Department, with the technical assistance of facility staff. The authors also thank the Tetrahymena Stock Center (Cornell University) for strains.

The research was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health–National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM099820), the American Cancer Society, and the Linda Crnic Institute (to C.G. Pearson).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: A.W.J. Soh designed and executed experiments and data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. T.J.P. van Dam performed the phylogenetic analysis. A.J. Stemm-Wolf generated Tetrahymena strains. A.T. Pham performed the DISA-1 rescue experiments. G.P. Morgan and E.T. O’Toole acquired EM tomograms. C.G. Pearson directed the study and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Allen R.D. 1967. Fine structure, reconstruction and possible functions of components of the cortex of Tetrahymena pyriformis. J. Protozool. 14:553–565. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1967.tb02042.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniades I., Stylianou P., and Skourides P.A.. 2014. Making the connection: ciliary adhesion complexes anchor basal bodies to the actin cytoskeleton. Dev. Cell. 28:70–80. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell G.J., Bricker C.S., Schwandt A., Gorovsky M.A., and Pennock D.G.. 1992. A temperature-sensitive mutation affecting synthesis of outer arm dyneins in Tetrahymena thermophila. J. Protozool. 39:261–266. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1992.tb01312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisson J., and Sonneborn T.M.. 1965. Cytoplasmic inheritance of the organization of the cell cortex in Paramecium aurelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 53:275–282. 10.1073/pnas.53.2.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink B., Xie C., and Huson D.H.. 2015. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 12:59–60. 10.1038/nmeth.3176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung A.T., and Jahn T.L.. 1976. High speed cinemicrographic studies on rabbit tracheal (ciliated) epithelia: determination of the beat pattern of tracheal cilia. Pediatr. Res. 10:140–144. 10.1203/00006450-197602000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen E.R. 1971. Centriole morphogenesis in developing ciliated epithelium of the mouse oviduct. J. Cell Biol. 51:286–302. 10.1083/jcb.51.1.286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy S.R. 2011. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLOS Comput. Biol. 7:e1002195 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emms D.M., and Kelly S.. 2015. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 16:157 10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang G., Zhang D., Yin H., Zheng L., Bi X., and Yuan L.. 2014. Centlein mediates an interaction between C-Nap1 and Cep68 to maintain centrosome cohesion. J. Cell Sci. 127:1631–1639. 10.1242/jcs.139451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel J. 1964. Cortical morphogenesis and synchronization in Tetrahymena pyriformis GL. Exp. Cell Res. 35:349–360. 10.1016/0014-4827(64)90101-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel J. 1989. Pattern-Formation - Ciliate Studies and Models. Oxford University Press, New York. 262 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel J. 2008. What do genic mutations tell us about the structural patterning of a complex single-celled organism? Eukaryot. Cell. 7:1617–1639. 10.1128/EC.00161-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galati D.F., Bonney S., Kronenberg Z., Clarissa C., Yandell M., Elde N.C., Jerka-Dziadosz M., Giddings T.H., Frankel J., and Pearson C.G.. 2014. DisAp-dependent striated fiber elongation is required to organize ciliary arrays. J. Cell Biol. 207:705–715. 10.1083/jcb.201409123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G. III, and Reiter J.F.. 2016. A primer on the mouse basal body. Cilia. 5:17 10.1186/s13630-016-0038-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddings T.H. Jr., Meehl J.B., Pearson C.G., and Winey M.. 2010. Electron tomography and immuno-labeling of Tetrahymena thermophila basal bodies. Methods Cell Biol. 96:117–141. 10.1016/S0091-679X(10)96006-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hard R., and Rieder C.L.. 1983. Muciliary transport in newt lungs: the ultrastructure of the ciliary apparatus in isolated epithelial sheets and in functional triton-extracted models. Tissue Cell. 15:227–243. 10.1016/0040-8166(83)90019-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A., and Mochizuki K.. 2015. Targeted gene disruption by ectopic induction of DNA elimination in Tetrahymena. Genetics. 201:55–64. 10.1534/genetics.115.178525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He R., Huang N., Bao Y., Zhou H., Teng J., and Chen J.. 2013. LRRC45 is a centrosome linker component required for centrosome cohesion. Cell Reports. 4:1100–1107. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holberton D., Baker D.A., and Marshall J.. 1988. Segmented alpha-helical coiled-coil structure of the protein giardin from the Giardia cytoskeleton. J. Mol. Biol. 204:789–795. 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90370-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iftode F., Adoutte A., and Fleury A.. 1996. The surface pattern of Paramecium tetraurelia in interphase: an electron microscopic study of basal body variability, connections with associated ribbons and their epiplasmic environment. Eur. J. Protistol. 32:46–57. 10.1016/S0932-4739(96)80076-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jerka-Dziadosz M., Jenkins L.M., Nelsen E.M., Williams N.E., Jaeckel-Williams R., and Frankel J.. 1995. Cellular polarity in ciliates: persistence of global polarity in a disorganized mutant of Tetrahymena thermophila that disrupts cytoskeletal organization. Dev. Biol. 169:644–661. 10.1006/dbio.1995.1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker A.D., Soh A.W.J., O’Toole E.T., Meehl J.B., Guha M., Winey M., Honts J.E., Gaertig J., and Pearson C.G.. 2019. Microtubule glycylation promotes basal body attachment to the cell cortex. J. Cell Sci. 132 10.1242/jcs.233726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., and Standley D.M.. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30:772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer J.R., Mastronarde D.N., and McIntosh J.R.. 1996. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116:71–76. 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunimoto K., Yamazaki Y., Nishida T., Shinohara K., Ishikawa H., Hasegawa T., Okanoue T., Hamada H., Noda T., Tamura A., et al. 2012. Coordinated ciliary beating requires Odf2-mediated polarization of basal bodies via basal feet. Cell. 148:189–200. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen J., and Satir P.. 1991. Analysis of Ni(2+)-induced arrest of Paramecium axonemes. J. Cell Sci. 99:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck K.F., and Melkonian M.. 1991. Striated microtubule-associated fibers: identification of assemblin, a novel 34-kD protein that forms paracrystals of 2-nm filaments in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 115:705–716. 10.1083/jcb.115.3.705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck K.F., and Silflow C.D.. 1997. SF-assemblin in Chlamydomonas: sequence conservation and localization during the cell cycle. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 36:190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemullois M., Gounon P., and Sandoz D.. 1987. Relationships between cytokeratin filaments and centriolar derivatives during ciliogenesis in the quail oviduct. Biol. Cell. 61:39–49. 10.1111/j.1768-322X.1987.tb00567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde D.N. 1997. Dual-axis tomography: an approach with alignment methods that preserve resolution. J. Struct. Biol. 120:343–352. 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde D.N. 2005. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 152:36–51. 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehl J.B., Giddings T.H. Jr., and Winey M.. 2009. High pressure freezing, electron microscopy, and immuno-electron microscopy of Tetrahymena thermophila basal bodies. Methods Mol. Biol. 586:227–241. 10.1007/978-1-60761-376-3_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijering E., Dzyubachyk O., and Smal I.. 2012. Methods for cell and particle tracking. Methods Enzymol. 504:183–200. 10.1016/B978-0-12-391857-4.00009-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narematsu N., Quek R., Chiam K.H., and Iwadate Y.. 2015. Ciliary metachronal wave propagation on the compliant surface of Paramecium cells. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 72:633–646. 10.1002/cm.21266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S.F., and Frankel J.. 1977. 180 degrees rotation of ciliary rows and its morphogenetic implications in Tetrahymena pyriformis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 74:1115–1119. 10.1073/pnas.74.3.1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitelka D. 1961. Fine structure of the silverline and fibrillar systems of three Tetrahymenid ciliates. J. Protozool. 8:75–89. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1961.tb01186.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel-Kruse I.H., Hilfinger A., Howard J., and Jülicher F.. 2007. How molecular motors shape the flagellar beat. HFSP J. 1:192–208. 10.2976/1.2773861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Teslenko M., van der Mark P., Ayres D.L., Darling A., Höhna S., Larget B., Liu L., Suchard M.A., and Huelsenbeck J.P.. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61:539–542. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., et al. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9:676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F., Wilm A., Dineen D., Gibson T.J., Karplus K., Li W., Lopez R., McWilliam H., Remmert M., Söding J., et al. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7:539 10.1038/msb.2011.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneborn T.M. 1964. The determinants and evolution of life. The differentiation of cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 51:915–929. 10.1073/pnas.51.5.915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 30:1312–1313. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemm-Wolf A.J., Morgan G., Giddings T.H. Jr., White E.A., Marchione R., McDonald H.B., and Winey M.. 2005. Basal body duplication and maintenance require one member of the Tetrahymena thermophila centrin gene family. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:3606–3619. 10.1091/mbc.e04-10-0919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm S.L. 1984. Mechanical synchronization of ciliary beating within comb plates of ctenophores. J. Exp. Biol. 113:401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm S.L. 1999. Locomotory waves of Koruga and Deltotrichonympha: flagella wag the cell. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 43:145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartar V. 1956. Pattern and substance in Stentor. Rudnick D., editor. Princton University Press, London: 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon G.G., and Woolley D.M.. 2004. Basal sliding and the mechanics of oscillation in a mammalian sperm flagellum. Biophys. J. 87:3934–3944. 10.1529/biophysj.104.042648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertii A., Hung H.F., Hehnly H., and Doxsey S.. 2016. Human basal body basics. Cilia. 5:13 10.1186/s13630-016-0030-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladar E.K., Bayly R.D., Sangoram A.M., Scott M.P., and Axelrod J.D.. 2012. Microtubules enable the planar cell polarity of airway cilia. Curr. Biol. 22:2203–2212. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlijm R., Li X., Panic M., Rüthnick D., Hata S., Herrmannsdörfer F., Kuner T., Heilemann M., Engelhardt J., Hell S.W., and Schiebel E.. 2018. STED nanoscopy of the centrosome linker reveals a CEP68-organized, periodic rootletin network anchored to a C-Nap1 ring at centrioles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115:E2246–E2253. 10.1073/pnas.1716840115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner M.E., Hwang P., Huisman F., Taborek P., Yu C.C., and Mitchell B.J.. 2011. Actin and microtubules drive differential aspects of planar cell polarity in multiciliated cells. J. Cell Biol. 195:19–26. 10.1083/jcb.201106110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle J.R., and Chen-Shan L.. 1972. Cortical morphogenesis in Paramecium aurelia: mutants affecting cell shape. Genet. Res. 19:271–279. 10.1017/S0016672300014531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams N.E., Honts J.E., and Jaeckel-Williams R.F.. 1987. Regional differentiation of the membrane skeleton in Tetrahymena. J. Cell Sci. 87:457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winey M., Stemm-Wolf A.J., Giddings T.H. Jr., and Pearson C.G.. 2012. Cytological analysis of Tetrahymena thermophila. Methods Cell Biol. 109:357–378. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385967-9.00013-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Liu X., Yue G., Adamian M., Bulgakov O., and Li T.. 2002. Rootletin, a novel coiled-coil protein, is a structural component of the ciliary rootlet. J. Cell Biol. 159:431–440. 10.1083/jcb.200207153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.