Abstract

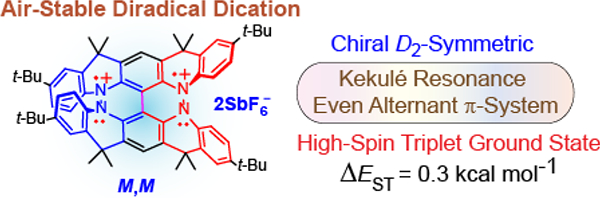

We report an air-stable diradical dication of chiral D2-symmetric conjoined bis[5]diazahelicene with unprecedented high spin (triplet) ground state, singlet triplet energy gap, ΔEST = 0.3 kcal mol−1. The diradical dication possesses closed-shell (Kekulé) resonance forms with 16 π-electron perimeters. The diradical dication is monomeric in dibutylphthalate (DBP) matrix at low temperatures, and it has a half-life of more than two weeks at ambient conditions in the presence of excess oxidant. A barrier of ~35 kcal mol−1 has been experimentally determined for inversion of configuration in the neutral conjoined bis[5]diazahelicene, while the inversion barriers in its radical cation and diradical dication were predicted by the DFT computations to be within a few kcal mol−1 of that in the neutral species. Chiral HPLC resolution provides the chiral D2-symmetric conjoined bis[5]diazahelicene, enriched in (P,P)- or (M,M)-enantiomers. The enantiomerically enriched triplet diradical dication is configurationally stable for 48 h at room temperature, thus providing the lower limit for inversion barrier of configuration of 27 kcal mol−1. The enantiomers of conjoined bis[5]diazahelicene and its diradical dication show strong chirooptical properties that are comparable to [6]helicene or carbon-sulfur [7]helicene, as determined by the anisotropy factors, |g| = |Δε|/ε = 0.007 at 348 nm (neutral) and |g| = 0.005 at 385 nm (diradical dication). DFT computations of the radical cation suggest that SOMO and HOMO energy levels are near-degenerate.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

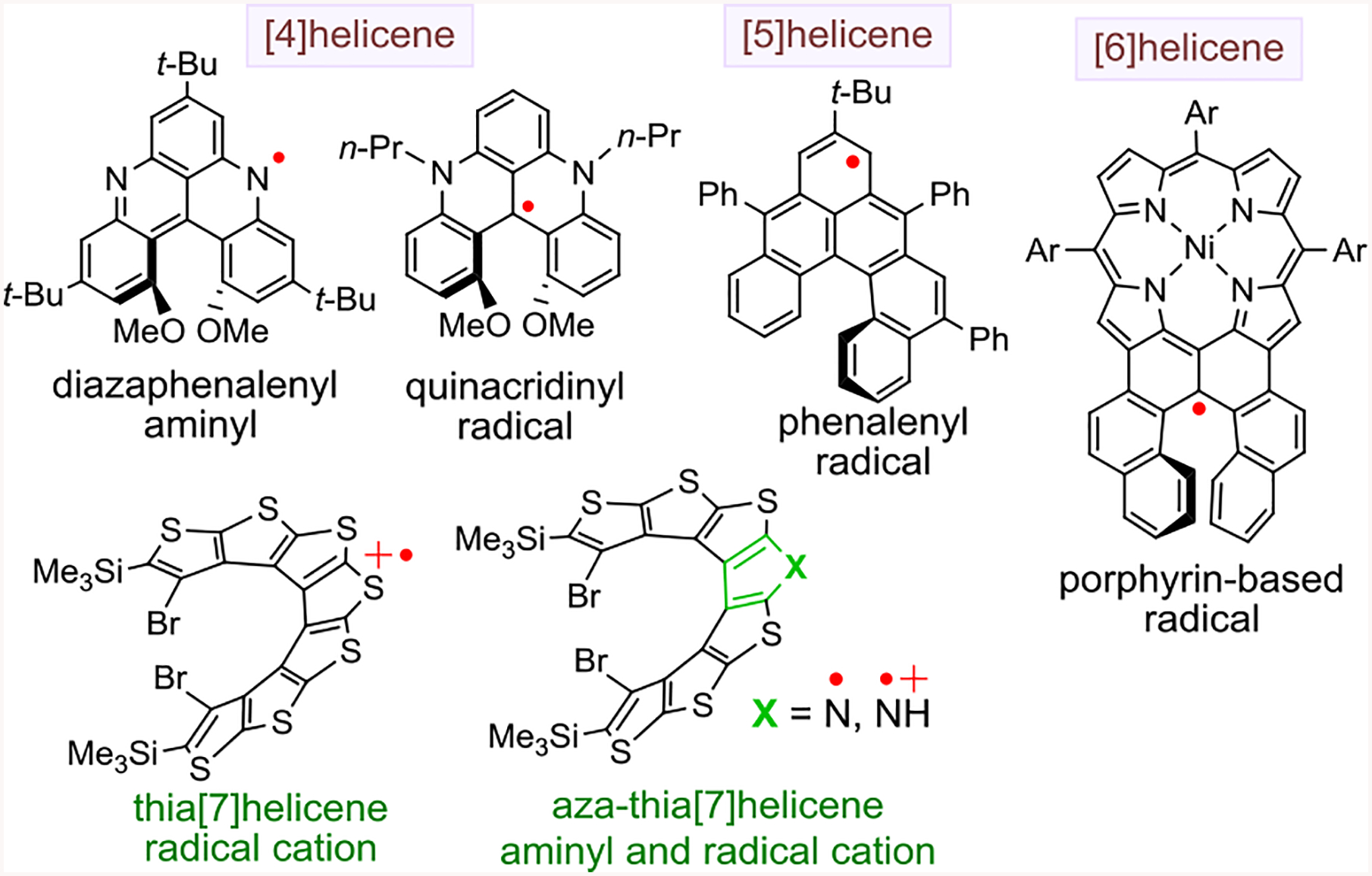

The inherent optical and magnetic properties that arise from a combination of helicene chirality1 and unpaired electron spin delocalization within helical π-systems of organic molecules are of fundamental interest to the discovery and development of novel organic optoelectronic materials and devices.2–5 There are very few open-shell helical molecules with such a distinctive combination of properties, and they are mostly represented by radical ions of short helical structures. Examples are a [4]helicene diazaphenalenyl aminyl and quinacridinyl radicals, [5]helicene phenalenyl radical (and related [5]helicene singlet biradicals), air stable [6]helicene porphyrin-based radical, and hetero[7]helicene radical cations (and aminyl radical) (Figure 1).6–12

Figure 1.

S = ½ open-shell helical molecules.

In spite of the recent breakthroughs in the design and synthesis of robust high-spin ground state diradicals,13,14 a high-spin diradical that is imbedded within the π-conjugated helices remains unknown. Combined molecular properties of strong chirality and high-spin ground state could be beneficial to the development of novel magnetic materials. Considering that [5]helicene-derivatives are known to provide efficient spin filtering with ca. 50% spin polarizations,2 while high-spin diradicals were computed to provide up to 100% spin polarizations,5 high-spin chiral π-conjugated helical molecule is promising as an organic spin filter.

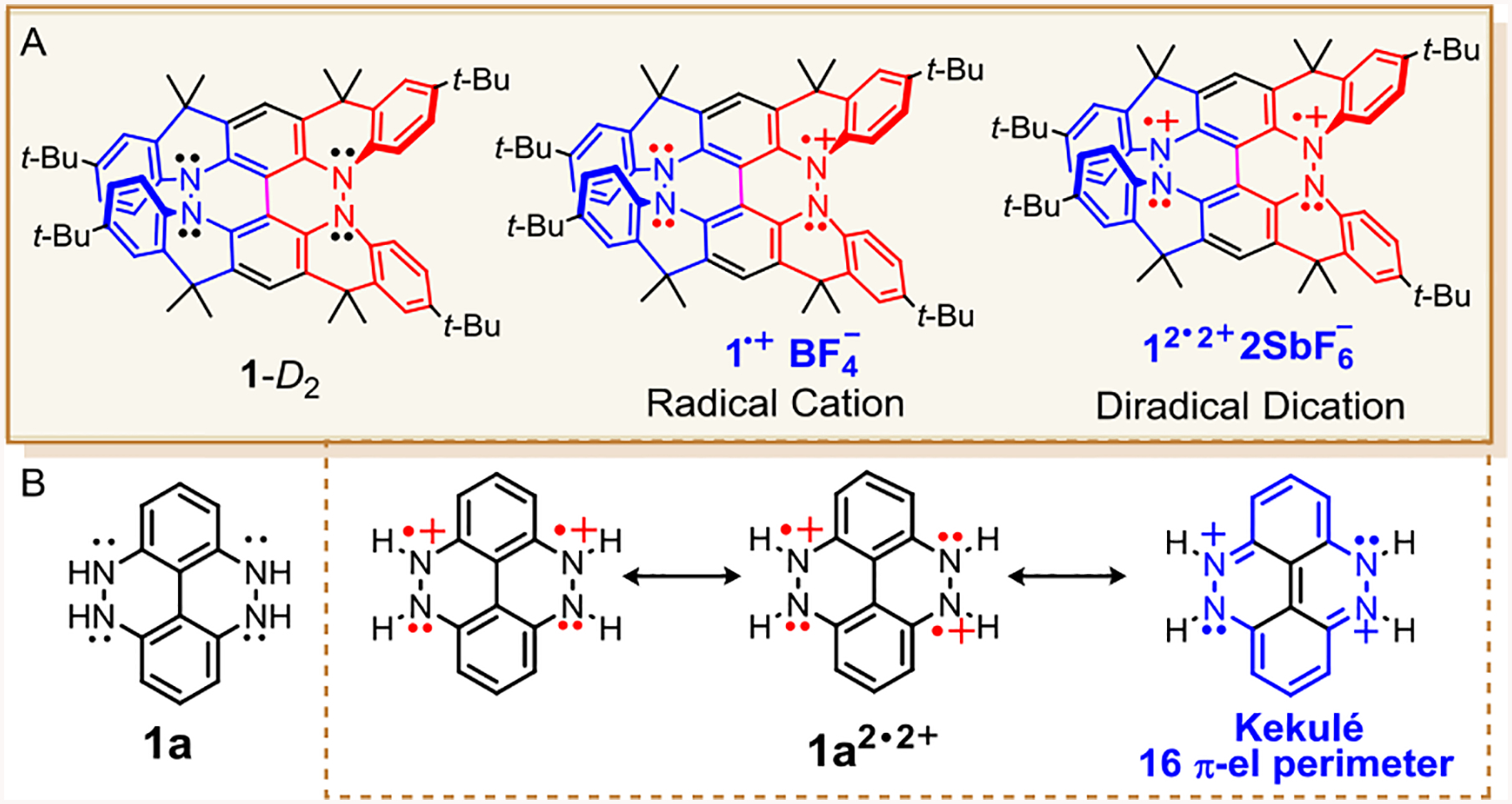

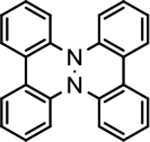

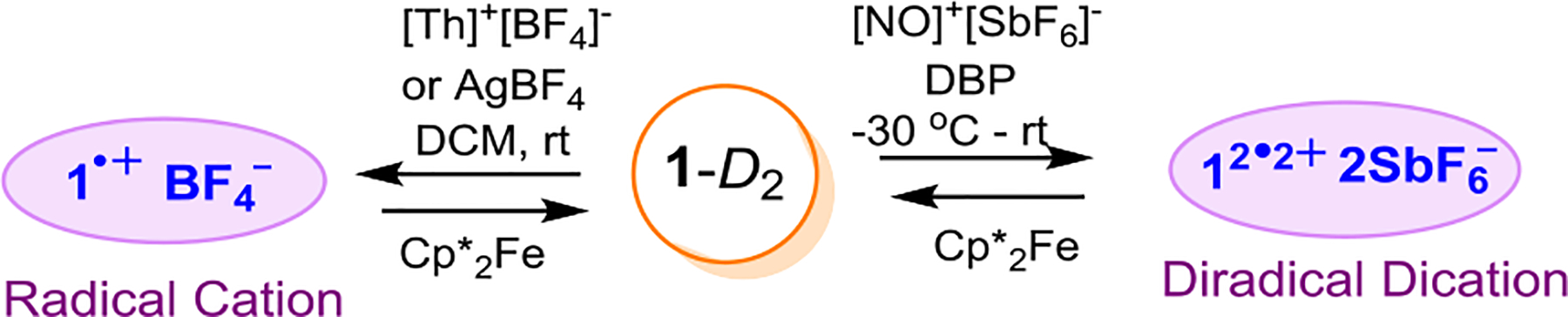

We have developed a straightforward synthesis of a double helical structure, the chiral conjoined bis[5]diazahelicene 1-D2 incorporating dihydrazine moiety (Figure 2)15 that is anticipated to be readily oxidized to radical cations. Especially, the corresponding radical cation 1•+ and diradical dication 12•2+ are of interest for investigating the delocalized electron spins within chiral π-conjugated system.

Figure 2.

A) Chiral conjoined bis[5]diazahelicene 1-D2, its corresponding radical cation and diradical dication. B) Dihydrazine 1a and selected resonance forms for diradical dication 1a2•2+, in which one of the four Kekulé resonance forms with 16 π-electron perimeters is shown.

Upon examination of the simplified structure of 1-D2, dihydrazine 1a (4,5,9,10-tetrahydro-4,5,9,10-tetraazapyrene, Figure 2), we found the presence of closed-shell (Kekulé) resonance form in diradical dication, 1a2•2+, which possesses an even alternant π-system. This would imply that the diradical dication should possess a singlet ground state.16 We also note that those Kekulé resonance forms possess 16 π-electron perimeters, which suggests that they are relatively destabilized because of Hückel antiaromaticity. The non-Kekulé resonance forms of 1a2•2+ also possesses Hückel antiaromatic 16 π-electron perimeters, but these are more than offset by two Hückel aromatic Clar sextets, thus leading to relative stabilization of open-shell forms.

Here we report the unexpected finding that the diradical dication 1a2•2+ 2SbF6− possesses triplet ground state with a singlet triplet energy gap, ΔEST = 0.3 kcal mol−1. The diradical dication is monomeric in dibutyl phthalate (DBP) solution and it is stable at ambient conditions with a half-life of more than two weeks. The diradical dication possesses an even alternant π-system and resonance forms with 16 π-electron perimeters, which, in conjunction with the triplet ground state, appear to conform to the criteria of Baird aromaticity17 – a topic of wide interest.18 Nevertheless, the literature reports to date include non-alternant π-systems with relatively low ΔEST <0.1 kcal mol−1.19 However, some exotic carbocation (and carbanion) structures, with non-alternant π-systems, were computed to possess large ΔEST,20 similarly to a classic triplet ground state cyclopentadienyl cation.21

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and Electrochemistry.

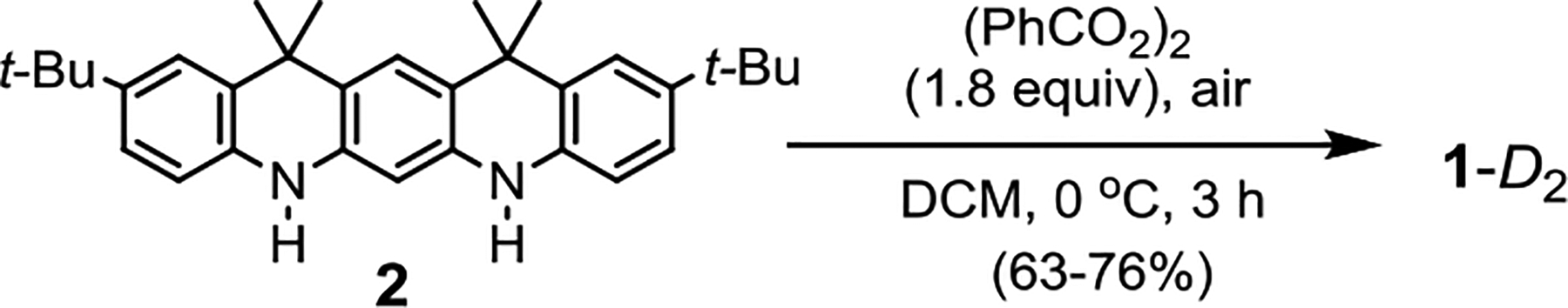

The bis[5]diazahelicene 1-D2 is prepared from diamine 2 by a one-pot reaction, in which the fused ring structure is obtained by two N-N and one C-C bond forming reactions (Scheme 1).15 Optimization of the reaction conditions and product purification provided racemic 1-D2 in 60+% isolated yield; the other possible diastereomer, C2h-symmetric meso-compound, i.e., 1-C2h, which is thermodynamically controlled product,15 was not detectable in 1H NMR spectra of crude reaction mixtures.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 1-D2.

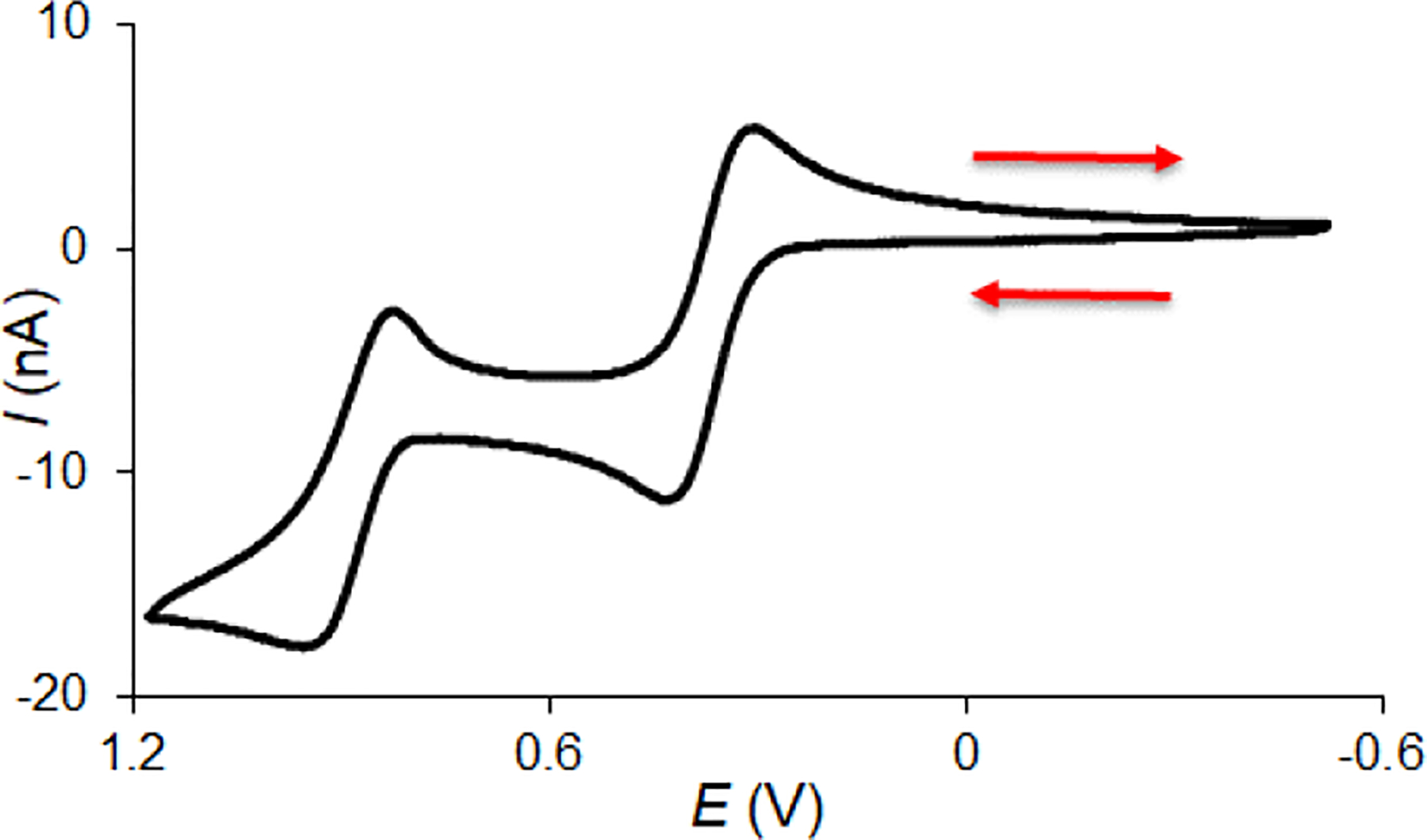

Cyclic voltammetry of 1-D2 in 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate ([n-Bu4N]+[PF6]−) in dichloromethane (DCM) shows reversible voltammogram consisting of two waves at E1° = +0.393 ± 0.011 V and E2° = +0.993 ± 0.020 V (Figure 3). As shown in Table 1, these potentials are below those of fused bicyclic tetraarylhydrazine 3 (benzo[c]benzo[3,4]cinnolino[1,2-a]cinnoline),22 tetraphenylhydrazine (Ph2NNPh2),23 azathia[7]helicene,12 and thia[7]helicene.24,25 The first and the second waves most likely correspond to a one-electron oxidation of 1-D2 to its radical cation (1•+ PF6−) and to a two-electron oxidation to its diradical dication (12•2+ 2PF6−), respectively; in addition, we observe a third one-electron wave at E30 ≈ 1.53 (Fig. S2, SI).

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammogram of ~0.7 mM 1-D2 in 0.1 M [n-Bu4N]+[PF6]− in DCM at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1. Further details are reported in Figs S1–S3, SI.

Table 1.

| Compounds | Oxidation Potentials | EPR (Radical cations) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E10 (V) | E20 (V) |

A(14N) (MHz) |

g | |

| 1-D2c | 0.393 ± 0.011a | 0.993 ± 0.020a | 10.0 | 2.0030 |

3c |

0.485b,d | 1.220b,d | 20.2f | 20032f |

| Ph2NNPh2 | 0.795b,d,e | 1.690b,d,e | 25.0f | 2.0032f |

| aza-thia [7]helicene | 0.884 ± 0.010a | 1.086 ± 0.005a | 6.4 | 2.0050 |

| thia [7]helicene | 1.34 | 1.82 | - | 2.006 |

Oxidation of 1-D2.

We explored chemical oxidation of 1-D2, in which experiments are carried out in a custom-made Schlenk vessel, which designed for in situ EPR or EPR/UV-vis-NIR spectroscopic measurements to monitor the oxidation process.11,12

Radical Cation.

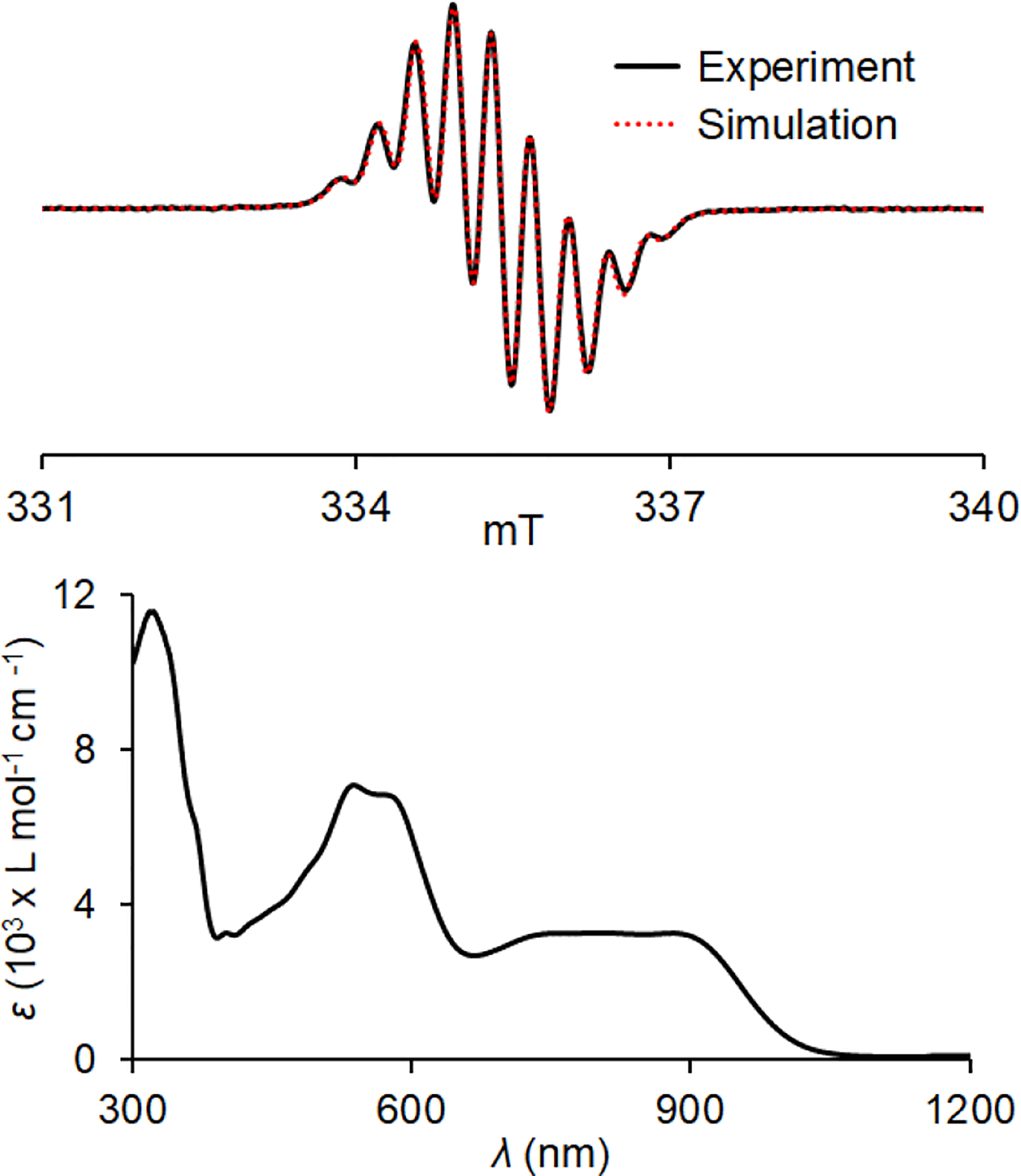

A brief exposure of 1-D2 in DCM to an approximately stoichiometric amount of AgBF4 or sub-stoichiometric amounts of thianthrene radical cation ([Th] •+[BF4]−, E10 ≈ +1.26 V)26 at room temperature provides a purple colored reaction mixture. A well-resolved nine-line EPR spectrum, corresponding to the coupling of four equivalent I = 1 14N nuclei with effective 14N-hyperfine coupling constant, A(14N) = 10.0 MHz, and isotropic g = 2.0030,27 is assigned to radical cation 1•+ BF4−. Spin counting experiment at T = 294 K gives χT ≈ 0.31 emu mol−1 K, corresponding to ~82% content of radical cation 1•+ BF4− in DCM solution, which remains unchanged even after 24 h at room temperature (Fig. S8, SI). The UV-vis-NIR spectrum shows intense bands at λmax = 322 and 538 nm (with a shoulder at 577 nm) and very broad NIR bands ranging from 740 to 880 nm (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

In situ EPR (ν = 9.6356 GHz) and UV-vis-NIR spectra for 0.58 mM radical cation 1•+ BF4− in DCM at ambient temperature, obtained during oxidation of 1-D2 with [Ag]+[BF4]−: EPR spectral simulations correspond to the following parameters: A(14N) = 10.0 MHz, g = 2.0030, and line-width = 0.28 mT. Bands at λmax = 322, 538, 577, 743, and 882 nm have the following extinction coefficients: ε322 = 1.16 × 104, ε538 = 7.09 × 103, ε577 = 6.83 × 103, ε743 = 3.25 × 103, and ε882 = 3.27 × 103 L mol−1 cm−1.

When ca. 2 equivalents of [Th] •+[BF4]−(E10 (V) ≈ +1.26 V) are used, a broad EPR spectrum at room temperature is observed instead of the well-resolved nine-line spectrum, while EPR spin concentration is sharply decreased. Evidently, addition of 1+ equivalent of [Th] •+[BF4]− produces the triplet diradical dication, of which EPR spectrum at room temperature in fluid DCM is effectively broadened to the baseline. In such case, the spin concentration of the remaining S = ½ radical cation is mainly measured. Noticeably, new bands at λmax = 331, 553, 651, and 899 nm are observed in the UV-vis-NIR spectrum (Fig. S10, SI).

Diradical Dication.

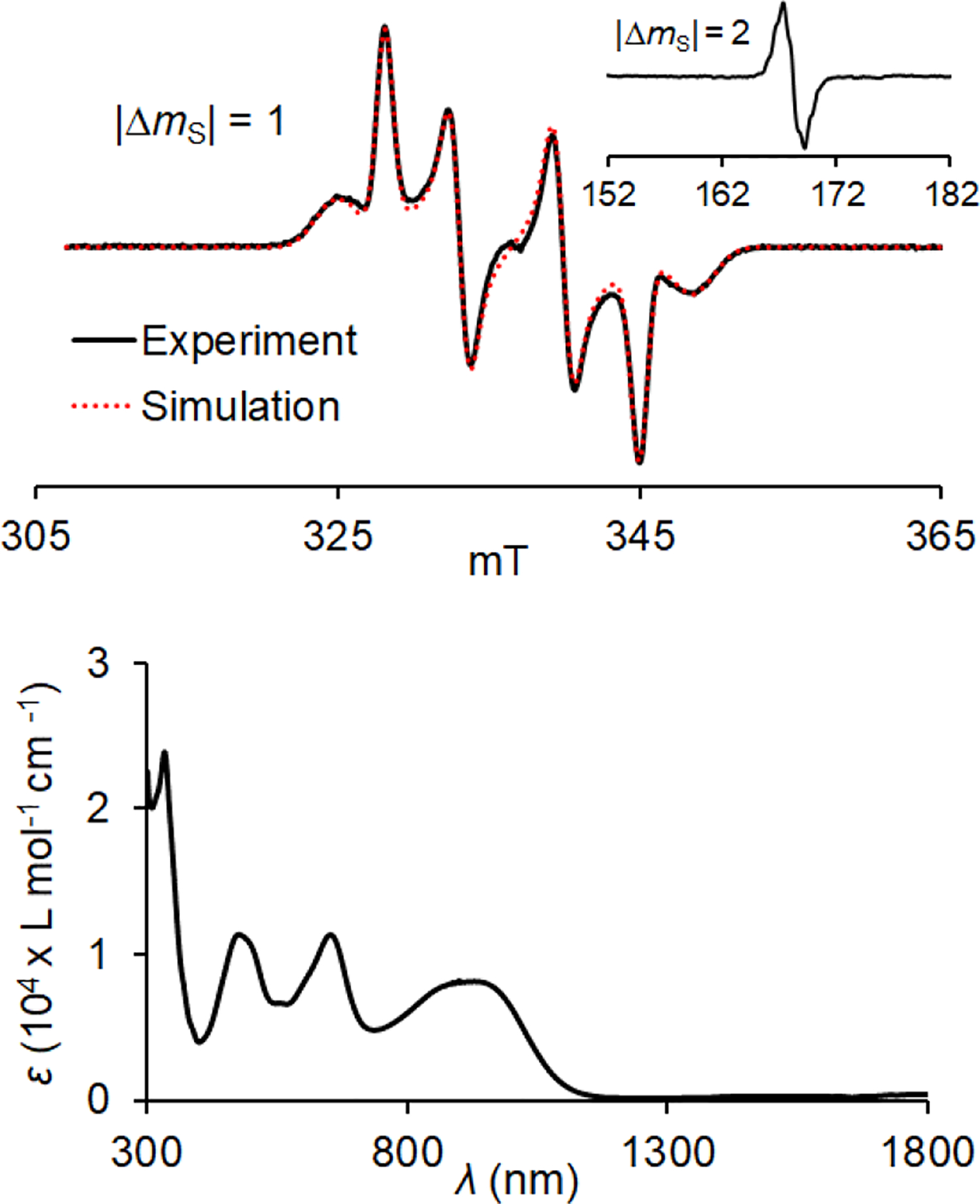

We examine nitrosonium hexafluoroantimonate [NO]+[SbF6]− in dibutyl phthalate (DBP) (E° = +1.46 V in DCM and +1.27 V in acetonitrile)26 as an oxidant for the oxidation of 1-D2 to its diradical dication 12•2+ 2SbF6− (E2° ≈ +0.95 V and E3° ≈ +1.53 V). When 2+ equiv of [NO]+[SbF6]− is used (Scheme 2), a well-defined S = 1 EPR spectrum, with negligible S = ½ impurities, is obtained (Figure 5). In addition, the |Δms| = 2 transition was observed. The |Δms| = 1 region of the spectrum may be simulated with the following zero-field splitting parameters: |D/hc| = 1.11 × 10−2 cm−1 and |E/hc| = 1.56 × 10−3 cm−1.27 Also, for a spectrum of 12•2+ 2SbF6− in DBP/CH3CN mixture, the most outer peaks show splitting associated with hyperfine coupling from four equivalent 14N (Fig. S21, SI), corresponding to |Azz/hc|/2 = 7.3 × 10−4 cm−1. B3LYP/EPR-II-computed values, using ORCA,28 of both |D/hc| = +1.32 × 10−2 cm−1 and |Azz/hc|/2 = 7.0 × 10−4 cm−1 are in good agreement with the experiment; the largest components of D- and A-tensors, as well as the smallest component of g-tensor, are oriented parallel to 2pπ orbital axis (Table S13, SI). These tensor orientations are analogous to those found in neutral triplet aminyl diradicals.29,30

Scheme 2.

Figure 5.

In situ EPR (117 K, ν = 9.4387 GHz) and UV-vis-NIR (294 K) spectra for 0.82 mM diradical dication 12•2+ 2SbF6−, obtained during oxidation of 1-D2 with [NO]+[SbF6]− in dibutyl phthalate (DBP). EPR spin counting at T = 117 K showed χT ≈ 0.92 emu mol−1 K. EPR spectrum of 12•2+ 2SbF6− in DBP at 117 K (inset: the |Δms| = 2 transition) with spectral simulation of the |Δms| = 1 region: |D/hc| = 1.11 × 10−2 cm−1, |E/hc| = 1.56 × 10−3 cm−1, |Azz/hc|/2 = 7.3 × 10−4 cm−1, gxx = 2.0036, gyy = 2.0035, gzz = 2.0025. UV-vis-NIR absorption spectrum of 12•2+ 2SbF6− in DBP, bands at λmax = 332, 476, 652, and 929 nm have the following extinction coefficients: ε332 = 2.39 × 104, ε476 = 1.14 × 104, ε652 = 1.14 × 104, and ε929 = 8.17 × 103 L mol−1 cm−1. Complete sets of EPR simulation parameters may be found in Figs. S14, S21, S24, and S26, SI.

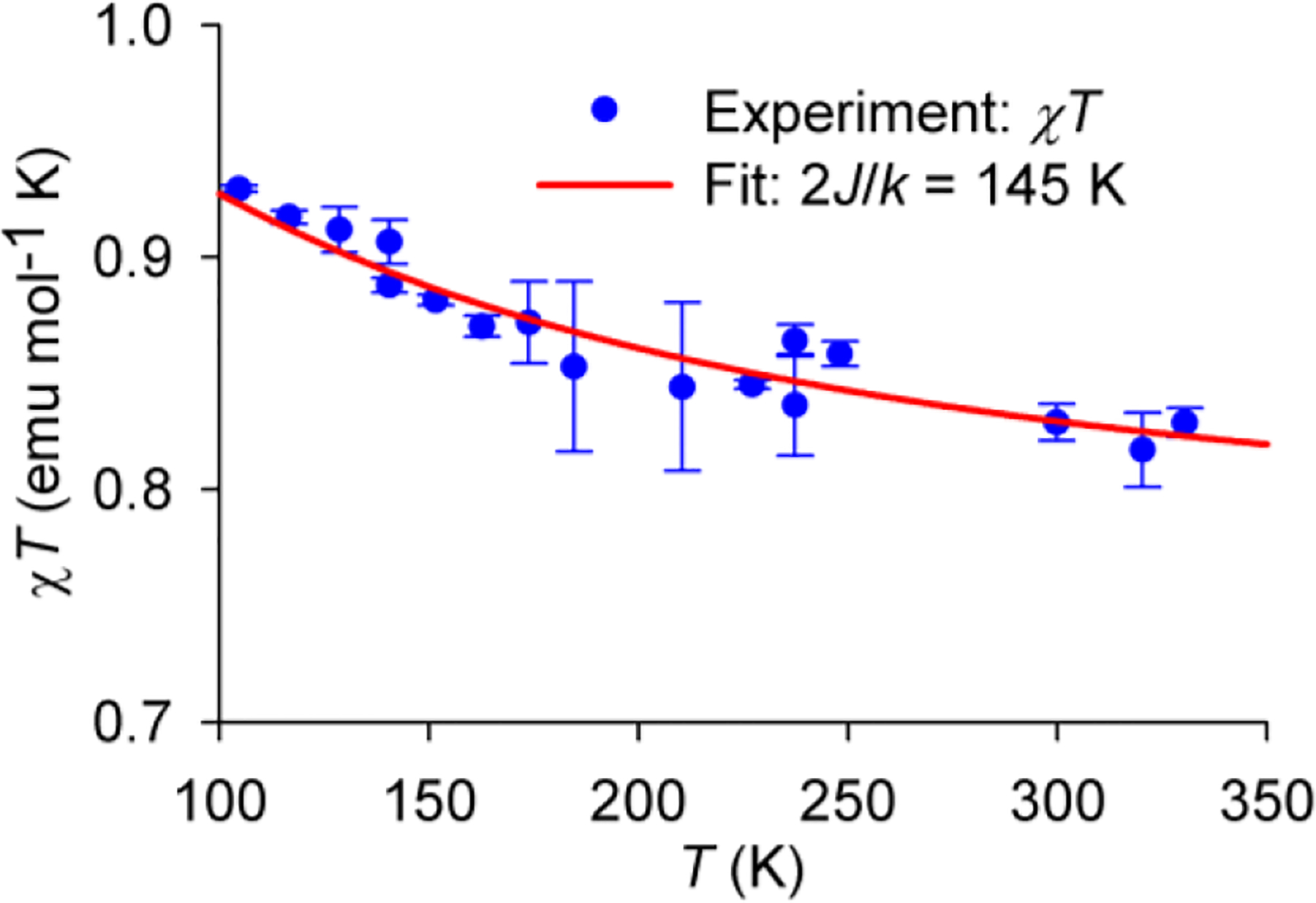

Quantitative EPR spectroscopy is used to determine triplet ground state of 12•2+ 2SbF6− in DBP by measurement of χT, the product of paramagnetic susceptibility (χ) and temperature (T), in the T = 105–330 K range (Figure 6).14a,30 Values of χT are obtained by spin counting, using standard such as TEMPONE in DBP (in triplicate, n = 3), and then are fit to the Bleaney–Bowers equation, to provide singlet-triplet energy gap 2J/k = 145 ± 4 K (mean ± SE), i.e., ΔEST = 0.3 kcal mol−1 (Figure 6).14a

Figure 6.

Quantitative EPR spectroscopy of 0.82 mM diradical dication 12•2+ 2SbF6− in DBP: experimental values of χT (mean ± SE, n = 3), the product of paramagnetic susceptibility (χ) and T in the T = 105 – 330 K range and numerical one-parameter fit with the variable parameter, 2J/k = 145 ± 4 K (mean ± SE). Further details are reported in the SI, Fig. S12, S16, and S26.

The quantitative EPR spectroscopy also indicates high persistence of 12•2+ 2SbF6− on air at room temperature. For the 0.82 mM sample (Figure 5), no detectable change in χT is observed after 2 h of air exposure at 294 K. In a more rigorous experiment on another sample, with 14 time points in the 0 – 48 h range and with accurate measurements (n = 3) of χT at 117 K, a half-life of more than two weeks is determined, in the presence of excess oxidant (Figs. S13 and S25, SI).

Remarkably, the low temperature EPR spectra of diradical dication in frozen solutions do not show evidence for formation of diamagnetic π-dimers, which are commonly found for planar π-conjugated radical cations.31 We ascribe this finding to the double helical shape and bulky (tert-butyl) terminal groups.11,12

Reduction of Radical Cation and Diradical Dication.

Reduction of radical cation 1•+ BF4− with decamethylferrocene, Cp*2Fe, in DCM leads to a color change of the reaction mixture from purple to yellow, producing starting conjoined [5]helicene 1-D2 as the only detectable diastereomer (Scheme 2, Table S2, Figs. S9 and S11, SI). Similarly, reduction of diradical dication 12•2+ 2SbF6− with Cp*2Fe in DCM/DBP also leads to the color change from purple to yellow, producing starting conjoined [5]helicene 1-D2 as the only detectable diastereomer, recovered in isolated yield of 83–96 % (Scheme 2, Table S3, Figs. S15, S19&20, S22&23, S27&28, SI).

Computational Study.

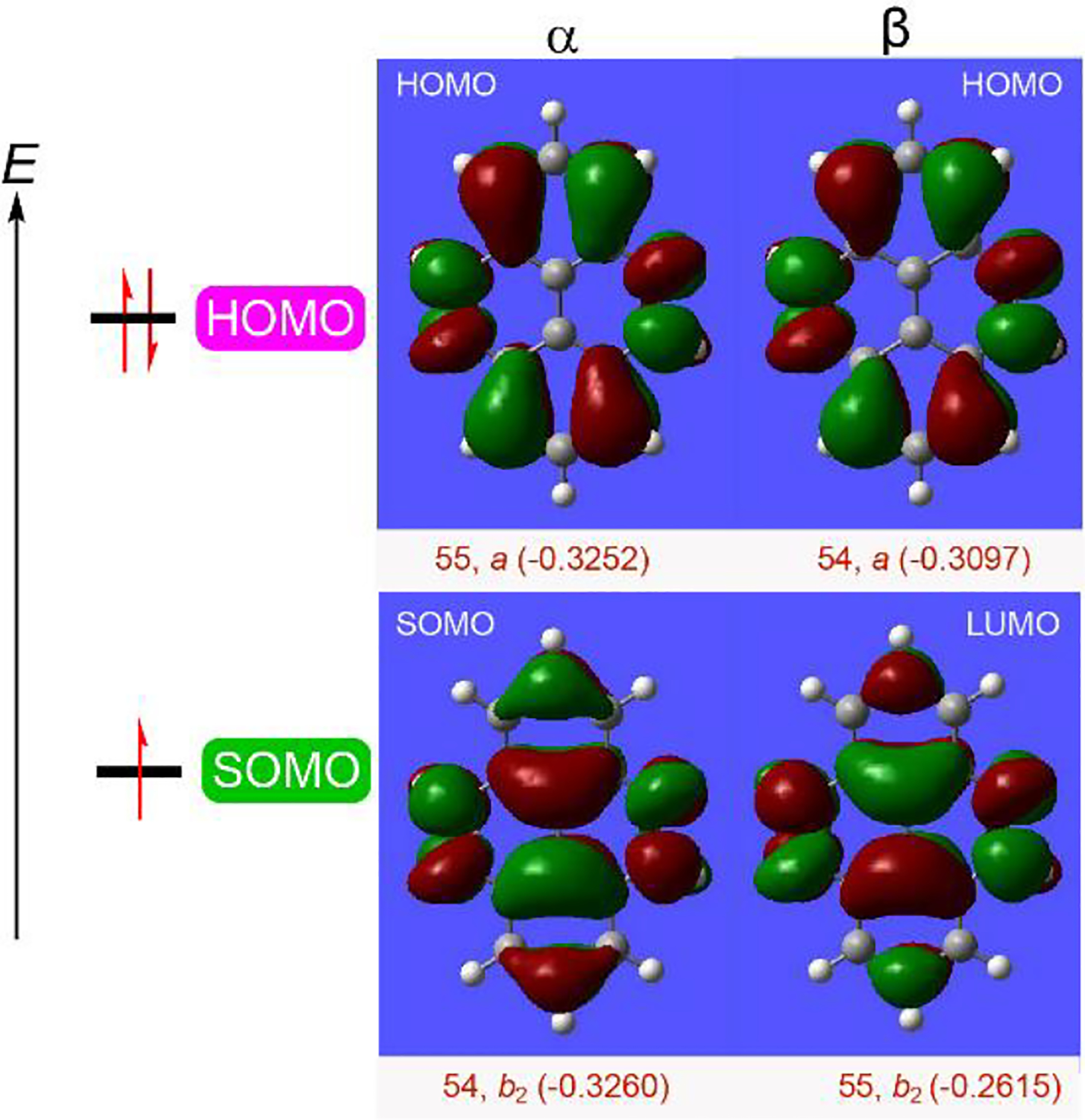

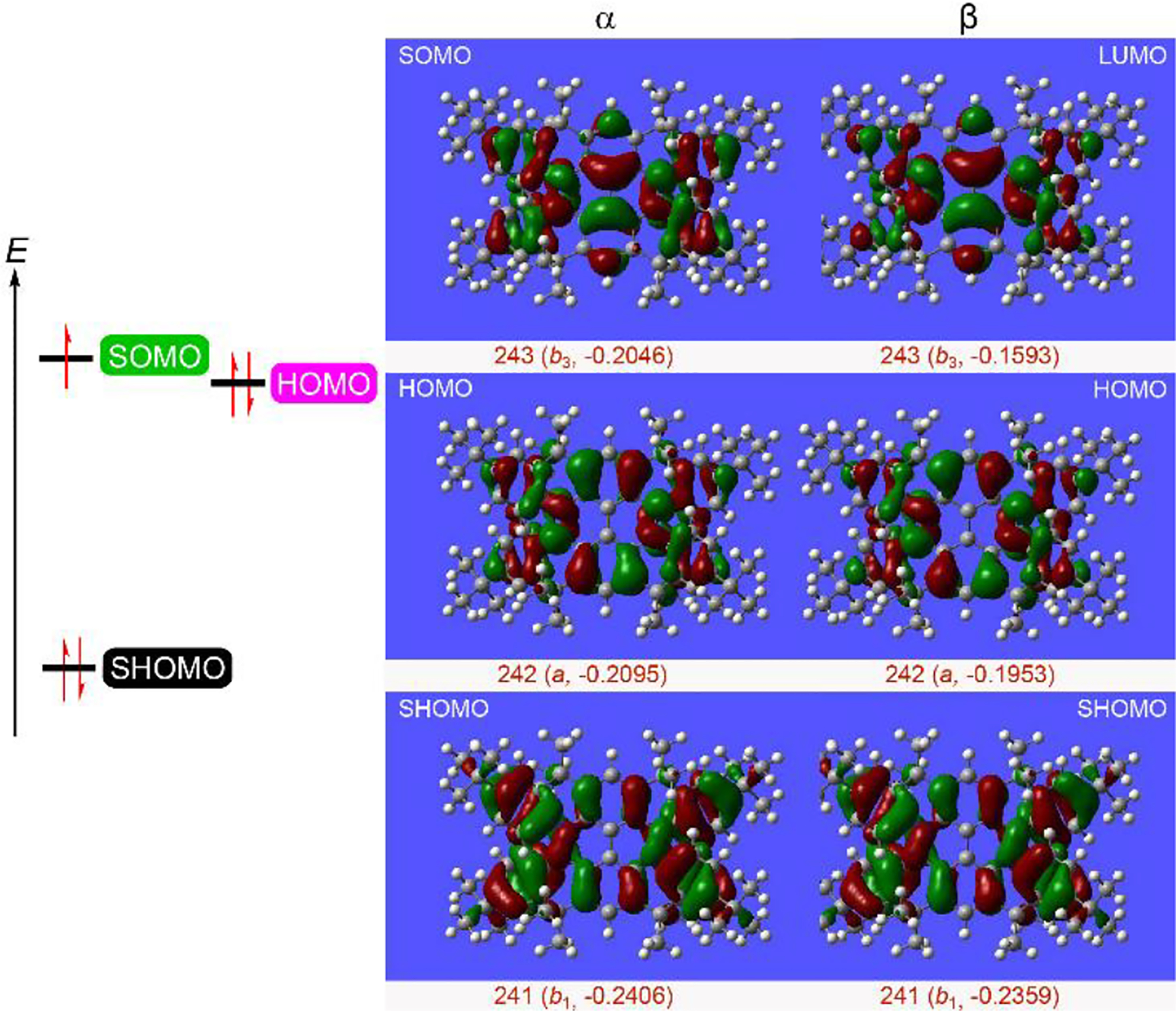

We investigate a simplified structure of conjoined [5]helicene 1, dihydrazine 1a (Figure 2), at the (U)B3LYP/6–31G(d)+ZPVE level of theory.32 The global minimum structure for diradical dication 1a2•2+ is a triplet ground state with D2h point group of symmetry and a large ΔEST = 4.0 kcal mol−1. For radical cation 1a•+, the D2h-symmetric structure is 2.2 kcal mol−1 above the C2h-symmetric global minimum and corresponds to the critical point with two imaginary frequencies. However, C2h- and D2-symmetric minima are nearly isoenergetic, with energy difference, ΔE < 0.05 kcal mol−1. As anticipated for such large ΔEST in the diradical dication, we observed the SOMO-HOMO energy inversion of about 0.5 kcal mol−1 and 0.7 kcal mol−1, as measured by the difference of energies of the relevant alpha-orbitals for its D2- and C2h-symmetric isomer, respectively (Figure 7, Table S9, SI).12

Fig. 7.

Orbital maps for the D2-symmetric structure of model radical cation 1a•+-D2 in the gas phase at the UB3LYP/6–31G(d,p) level. Positive (red) and negative (green) contributions are shown at the isodensity level of 0.02 electron/Bohr3. The singly-occupied α orbital is matched in a nodal pattern (b2-symmetry) to the lowest unoccupied β orbital to provide the SOMO energy level; doubly occupied molecular orbitals are identified by matching nodal pattern (a-symmetry for HOMO) and energies (in Hartrees) of the α and β occupied orbitals.

Notably, in polar solvents such as DCM or water, global minima for 1a•+ adopt C2 point group of symmetry with two non-equivalent hydrazine moieties. The C2-symmetric enantiomers are however fluxional with D2- and C2h-symmetric transition structures only 0.5–0.7 kcal mol−1 above the minima. Similar to that observed for radical and radical cation of aza-thia[7]helicene,12 the SOMO-HOMO orbital configurations are not only maintained in polar solvents, but the SOMO-HOMO energy inversions increase to 6.0 and 5.7 kcal mol−1 in DCM and water, respectively (Table S10, SI)!33 The results provide a new example of organic molecule with SOMO-HOMO energy inversion which violates the Aufbau principle.

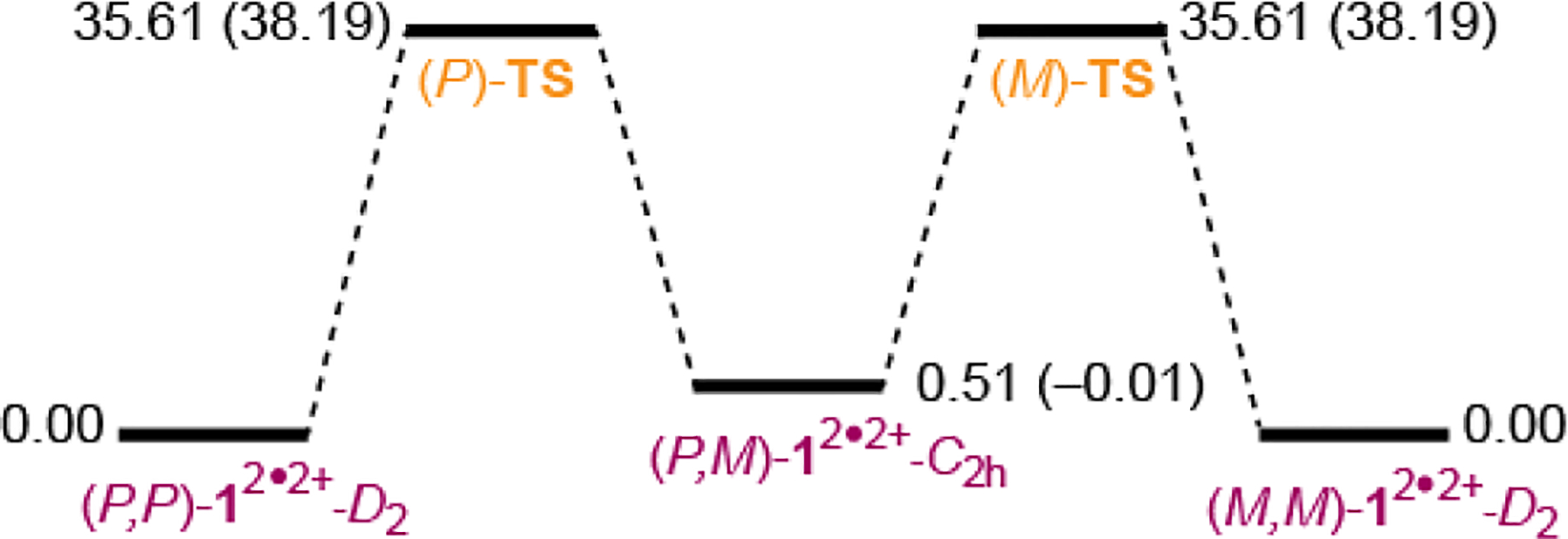

The structures of chiral 1-D2 and the meso compound 1-C2h, as well as their corresponding radical cations and diradical dications are computed at the (U)B3LYP/6–31G(d)+ZPVE levels of theory, both in the gas phase and in IEF-PCM-UFF solvent models for DCM. In addition, (U)M06–2X/6–31G(d)/IEF-PCM-UFF+ZPVE computations are carried out for selected structures (Table 2, Figure 8, Tables S5, S7, and S8 SI). For triplet states of simplified structure of diradical dication 1b2•2+, in which tert-butyl and gem-dimethyl groups were replaced with hydrogens, single point ROMP2/6–31G(d)//UB3LYP/6–31G(d) energies are calculated (Table 2, Figure 8, and Table S16, SI).

Table 2.

Relative energies (ΔE in kcal mol−1), including barriers for ring inversion (racemization) for 1-D2, 1-C2h and the corresponding radical cations and diradical dications at the (U)B3LYP/6–31G(d)+ZPVE level of theory.

| Crit. point | Structure | State | ΔE | ΔESTa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| minima | 1-C2h | 1Ag | 0.00 | - |

| 1-D2 | 1A | 1.08 | - | |

| TS | 1-C1 | 1A | 43.12 | - |

| minima | 1•+-C2h | 2Ag | 0.00 | - |

| 1•+-D2 | 2B3 | 0.14 | - | |

| TS | 1•+-C1 | 2A | 38.14 | - |

| minima | 12•2+-D2 | 3B3 | 0.00 (0.00)b | 0.00 |

| BS | - | 0.59 | ||

| 12•2+-C2h | 3Au | 0.51 (–0.01)b | 0.00 | |

| BS | - | 0.95 | ||

| TS | 12•2+-C1 | 3A | 35.61 (38.19)b | 0.00 |

| BS | - | 0.81 |

Singlet-triplet energy gaps (ΔEST in kcal mol−1) for diradical dications; BS corresponds to a broken-symmetry singlet.

Values in parentheses are for triplet states of simplified 1b2•2+ at the ROMP2/6–31G(d)//UB3LYP/6–31G(d) level of theory.

Figure 8.

Potential energy surface for racemization of triplet state of diradical dication 12•2+-D2 at the UB3LYP/6–31G(d)+ZPVE level of theory. Values in parentheses are for simplified 1b2•2+ at the ROMP2/6–31G(d)//UB3LYP/6–31G(d) level of theory

According to our previous report, neutral 1-D2 in naphthalene undergoes a clean conversion upon heating to 180 °C to its meso diastereomer 1-C2h, with a half-life of 3 h, corresponding to a barrier of about ~35 kcal mol−1.15 In a qualitative agreement with the experiment, chiral diastereomer 1-D2 is computed ca. 1 kcal mol−1 higher in energy than meso diastereomer 1-C2h, with the barrier of ca. 42 kcal mol−1 for conversion of 1-D2-to-1-C2h.

Notably, the D2- and C2h-diastereomers of radical cation are nearly isoenergetic, while the D2-diastereomer of diradical dication at the UB3LYP/6–31G(d) level is the global minimum ca. 0.5 kcal mol−1 below the meso-compound. For the open-shell species, the barriers for conversion of D2-to-C2h-diastereomer are in the 35–38 kcal mol−1 range (Table 2, Table S5, SI). Therefore, the potential energy surface for racemization of 12•2+-D2 involves two racemic C1-symmetric transition states and C2h-symmetric (meso) intermediate (Figure 8).

Because the triplet state stability is overestimated by UB3LYP and UM06–2X,34 the computed ΔEST = 0.6–1.0 kcal mol−1 for diradical dication is in reasonable agreement with the experimental value of ΔEST = 0.3 kcal mol−1. For such relatively small values of ΔEST < 1 kcal mol−1 in diradical dication, we find that the radical cation 1•+-D2 shows the nearly degenerate SOMO-HOMO energy levels, with SOMO-HOMO and HOMO-SHOMO energy differences of ca. 3 and 20 kcal mol−1, respectively (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Orbital maps for the D2-symmetric structure of radical cation 1•+-D2 at the UB3LYP/6–31G(d) level. Positive (red) and negative (green) contributions are shown at the isodensity level of 0.02 electron/Bohr3. The singly-occupied α orbital is matched in a nodal pattern (b3-symmetry) to the lowest unoccupied β orbital to provide the SOMO energy level; doubly occupied molecular orbitals are identified by matching nodal pattern (a-symmetry for HOMO and b1-symmetry for SHOMO) and energies (in Hartrees) of the α and β occupied orbitals.

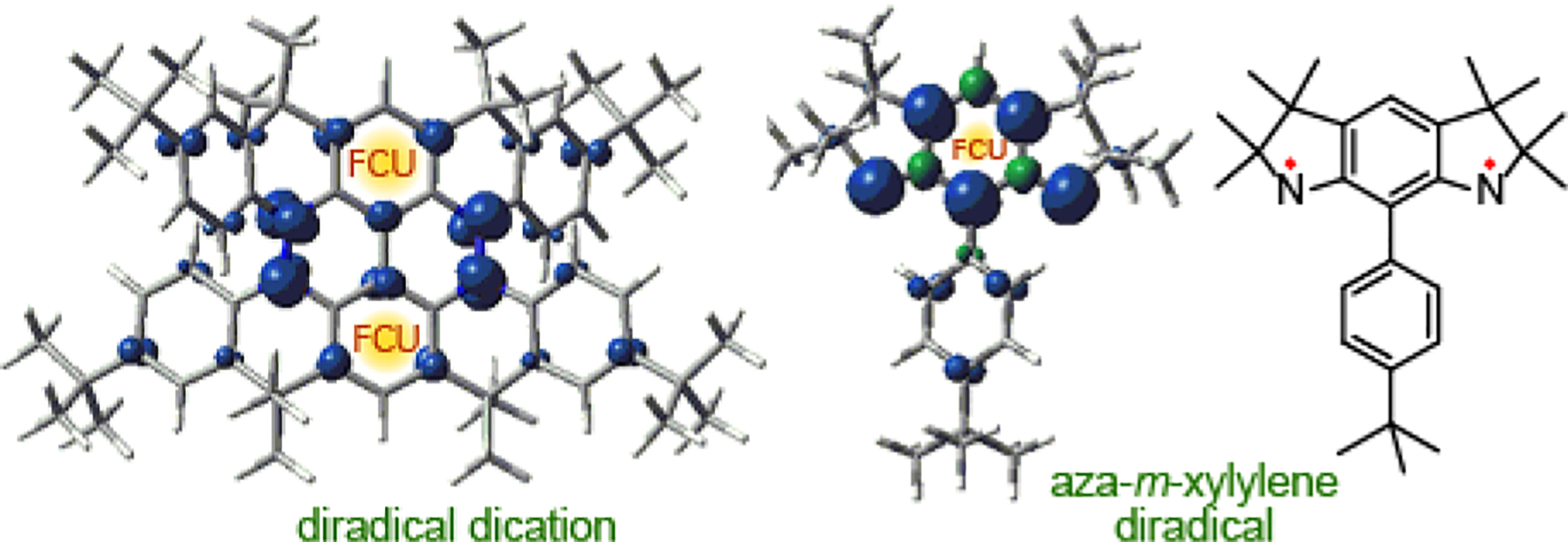

The experimentally determined ΔEST = 0.3 kcal mol−1 for diradical dication 12•2+ 2SbF6− is much lower than that of aza-m-xylylene diradicals,29,30 for which the ΔEST ≈ 10 kcal mol−1 was computed using the reliable DDCI method by Barone35 and the lower bound for the ΔEST of the order of 0.5 kcal mol−1 was experimentally determined.30 Diminishing ΔEST in diradical dication is due to the more dilute spin density associated with m-phenylene ferromagnetic coupling units (FCUs) and the presence of Kekulé resonance forms which would favor singlet ground state. Spin density maps for triplet ground states of diradical dication and aza-m-xylylene diradical are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Spin density maps for triplet ground states of diradical dication and aza-m-xylylene diradical at the UB3LYP/6–31G(d)//UB3LYP/6–31G(d)+ZPVE level. Positive (blue) and negative (green) spin densities are shown at the isodensity level of 0.006 electron/Bohr3.

Chiral Resolution.

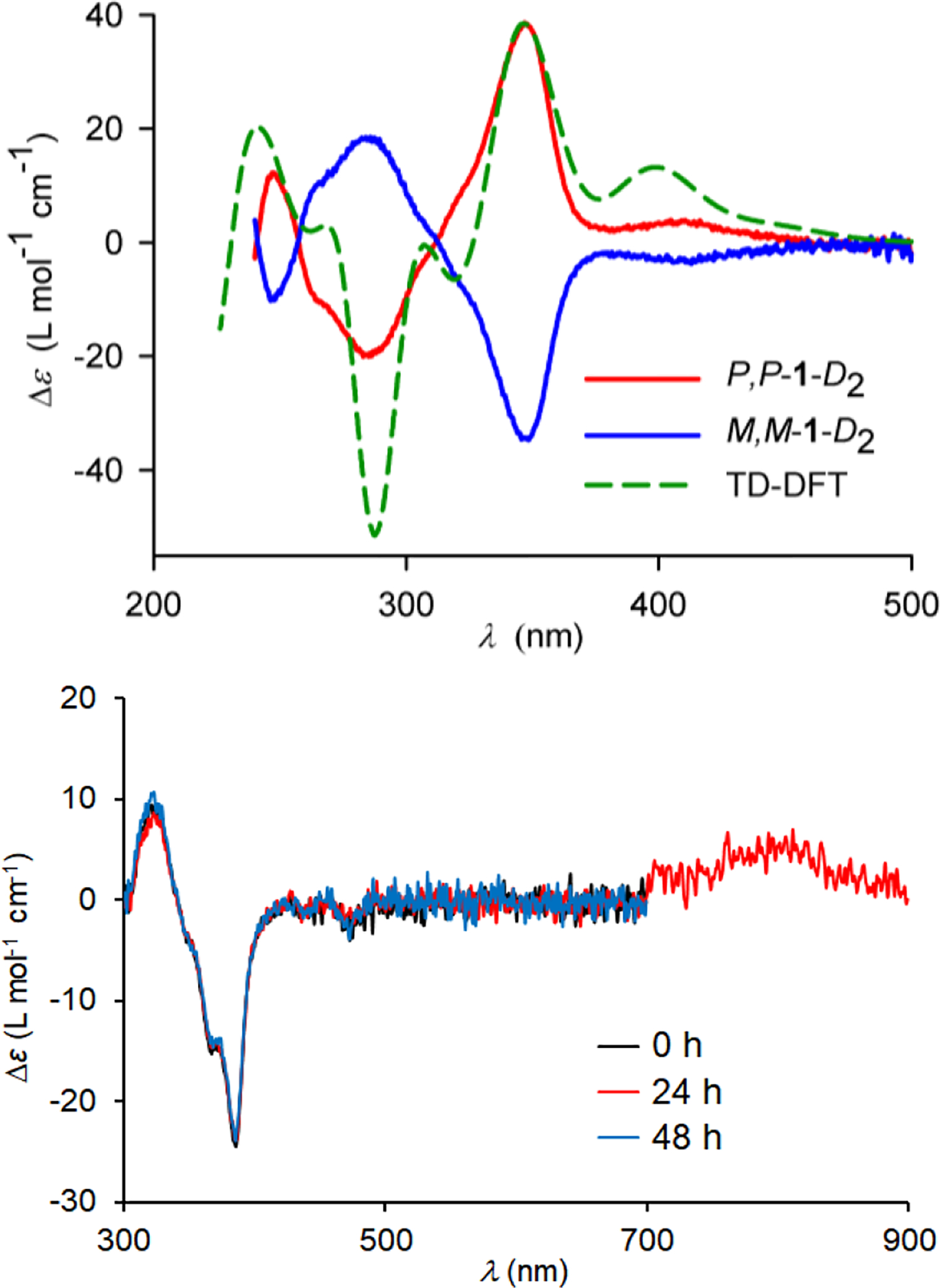

Room temperature configurational stability of 1-D2 and the corresponding diradical dication is confirmed by resolution of racemic 1-D2 by HPLC, using chiral AD-H column. In contrast to racemic carbon-sulfur [n]helicenes (n = 7, 9, and 11)24,25,35 and double helices,36,37 which gave baseline separation of enantiomers, resolution of 1-D2 turns out to be a challenging case. We could establish the optimum temperature of 12 °C (hexane as a mobile phase) for only partial resolution. We obtain mg-quantities of M,M-1-D2 and P,P-1-D2 with 41.7% and 61.3% enantiomeric excess (ee), respectively (Fig. S29, SI). The absolute configurations of the enantiomers are assigned by comparison of the experimental and TD-DFT-computed electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra (Figure 11 and Fig. S30, SI).

Figure 11.

ECD spectra at ambient temperature. Top: 1-D2 and TD-DFT computed spectrum for P,P-1-D2 (B3LYP/6–31G(d)-optimized geometry) at the CAM-B3LYP/6–31G(d) level in IEF-PCM-UFF-modelled DCM. Bottom: M,M-12•2+ 2SbF6−; three overlapped spectra at time 0, 24, and 48 h. Experimental ECD spectra intensities are scaled by the ee. Further details are reported in the SI, Table S4, Figs. S29–S36.

Oxidation of M,M-1-D2 or P,P-1-D2 with [NO]+[SbF6]− in DBP produces the corresponding enantiomerically-enriched diradical dications 12•2+ 2SbF6−. Configurational stability of 12•2+ 2SbF6− is illustrated by overlapping ECD spectra taken at 24 and 48 h apart, while the sample is kept at room temperature (Figure 11). Assuming <1% ee change after 48 h at 294 K, the lower limit of the barrier for racemization of M,M-12•2+ 2SbF6− is estimated at 27 kcal mol−1 (Eq. S2, SI).

The enantiomers of conjoined bis[5]diazahelicene 1-D2 show strong chirooptical properties, as determined by the anisotropy factor, |g| = |Δε|/ε = 0.007, based on P,P-1-D2 with Δεmax = +38.8 and ε = 5.45 × 103 L mol−1 cm−1 in DCM at 348 nm. Similarly, diradical dication P,P-12•2+ 2SbF6− has |g| = 0.005 with Δεmax = +26.4 and ε = 5.0 × 103 L mol−1 cm−1 in DBP at 385 nm. These anisotropy factors are comparable to |g| = 0.004 for the air stable porphyrin-based S = ½ radical9 and to those of [6]helicene (|g| = 0.007)38 and carbon-sulfur [7]helicene (|g| = 0.004)24 but smaller than the recently reported |g| = 0.039 for carbon-sulfur double helix.1b,37

CONCLUSION

We have prepared the first high-spin diradical imbedded within helical (doubly helical) π-system, demonstrating a molecule with a combined property of strong chirality and high-spin ground state. The high-spin ground state for this diradical, with an alternant π-system, is unusual because of presence of Kekulé resonance forms. Based on the existing computational and experimental reports, such molecule-based materials may provide enhanced spin filtering properties for the development of next generation of spintronics.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General procedures.

Standard techniques for synthesis under inert atmosphere (argon or nitrogen), using custom-made Schlenk glassware, custom-made double manifold high vacuum lines, argon-filled Vacuum Atmospheres and MBraun gloveboxes, and nitrogen- or argon-filled glovebags. Chromatographic separations were carried out using normal phase silica gel.

Cyclic and square wave voltammetric data for 1-D2, using decamethyl ferrocene as a reference, were obtained according to the procedures described in the SI.12,25 Synthesis of 1-D2 is described in the SI (Table S1 and Figs. S37–S45).15

Procedures for oxidation of conjoined bis[5]diazahelicene 1-D2 to radical cation 1•+BF4− and diradical dication 12•2+ 2SbF6−, are described below.

Radical cation 1•+ BF4−.

To the starting material 1-D2 (4.2 mg, 4.7 μmol) in a custom-made Schlenk vessel,12 evacuated on vacuum line at room temperature overnight, AgBF4 in dichloromethane (DCM, 0.41 mL, 0.0149 M, 6.1 μmol) was added to the vessel; color of the reaction mixture immediately changed to dark purple. After stirring at room temperature for 2 h, the reaction mixture was filtered with DCM and dried under the high vacuum overnight. Dark purple crude (5.5 mg) was obtained. Subsequently, the crude mixture was dissolved in DCM (0.584 mM) and transferred to a 4-mm EPR tube. EPR spectra were obtained at 294 K (Figure 4). Using tempone in DCM (1.091 mM) as reference, χT ≈ 0.31 emu mol−1 K was determined, corresponding to ~82% content of monoradical. The sample solution was diluted to 0.295 mM and UV-vis-NIR spectra were obtained (Figure 4). Following UV-vis-NIR spectra, solution in UV cuvette was transferred back to a new 4 mm EPR tube, and then using the same reference, 80% spin concentration was determined. Further details of preparation of radical cation, using [Th] •+[BF4]−as an oxidant, are summarized in Table S2 and Figs. S7–S11, SI.

Diradical dication 12•2+ 2SbF6−.

To the starting material 1-D2 (0.34 mg, 0.38 μmol) in a custom-made Schlenk vessel with 4-mm EPR tube, evacuated on vacuum line at room temperature for several days, distilled dibutyl phthalate (DBP, ~100 μL) was added under argon flow to obtain a yellow solution. Subsequently, the solution was cooled to −30 °C by ethanol-liquid nitrogen bath, and the oxidant, [NO]+[SbF6]−, in distilled DBP (60 μL, 3.8 equiv, 6.4 mg/1.0 mL) was added under flow of argon. The reaction mixture was stirred at −30 °C and evacuated until vacuum build up inside the vessel (pressure = ~ 1 mTorr). During this process the color of the reaction mixture changed from yellow to dark blue-purple. EPR spectrum showed diradical with a significant admixture of monoradical. The process of addition/evacuation of oxidant was repeated, until the EPR spectra showed absence of monoradical (SI). Subsequently, the reaction mixture was diluted with DBP (200 μL), to obtain dark blue solution (0.816 mM), which was studied by variable temperature (T = 105 – 330 K) quantitative EPR spectroscopy, using 1.005 mM tempone in DBP as reference (Figure 6). Prior to UV-Vis-NIR spectra, quantitative EPR spectra at T = 117 K showed χT ≈ 0.92 ± 0.01 emu mol−1 K (Figure 5). Then the solution of diradical dication was transferred under flow of argon to a custom-made Schlenk vessel with 2-mm UV cuvette. Following UV-vis-NIR absorption spectra (Figure 5), χT = 0.89 ± 0.02 was determined by quantitative EPR spectra at 117 K (Fig. S14, SI).

Finally, Cp*2Fe in DCM (1.34 mg, 10 eq) was added to the reaction mixture; the color changed from blue-purple to yellow. The solution was transferred to a vial and evaporated by N2 gas flow, and subsequently purified by column chromatography (regular silica gel, pentane/DCM, 5:1) with exclusion of light, followed by analytical TLC, to obtain 1-D2 as a yellow powder (0.29 mg, 85% recovery, Fig. S15, SI). Details of preparation of racemic diradical dication are summarized in Table S3, SI. Using similar procedures, chiral diradical dication is prepared, as summarized in Table S4, SI, and characterized (Figs. S32–S36, SI).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the NSF Chemistry Division for support of this research under Grants No. CHE-1362454 and CHE-1665256. We thank Dr. P. J. Boratynski for initial studies in the synthesis of 1-D2 and Dr. C. Yan for recording preliminary EPR spectra of the diradical dication. Upgrade of the EPR spectrometer was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS #R01GM124310-01).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

General procedures and materials, additional experimental andcomputattional details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Shen Y; Chen C-F Helicenes: synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 1463–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rajca A; Miyasaka M Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Chiral Conjugated Materials In Functional Organic Materials - Syntheses and Strategies; Mueller TJJ; Bunz UHF, Eds.; Wiley-VCH: New York, 2007; pp 543–577. [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Naaman R; Paltiel Y; Waldeck DH Chiral molecules and the electron spin. Nat. Rev. Chem 2019, 3, 250–260. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kira V; Mathew SP; Cohen SR; Delgado IH; Lacour J; Naaman R Helicenes—A New Class of Organic Spin Filter. Adv. Mater 2016, 28, 1957–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Miyamoto Y; Rubio A; Cohen ML Self-inductance of chiral conducting nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 13885–13889. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rikken GLJA; Folling J; Wyder P Electrical Magnetochiral Anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett 2001, 87, 236602–1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sessoli R; Boulon M-E; Caneschi A; Mannini M; Poggini L; Wilhelm F; Rogalev A Strong magneto-chiral dichroism in a paramagnetic molecular helix observed by hard X-ray. Nat Phys. 2015, 11, 69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xu X; Li W; Zhou X; Wang Q; Feng J; Tian WQ; Jiang Y Theoretical study of electron tunneling through the spiral molecule junctions along spiral paths. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2016, 18, 3765–3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Herrmann C; Solomon GC; Ratner MA Organic Radicals As Spin Filters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 3682–3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shil S; Bhattacharya D; Misra A; Klein DJ A high-spin organic diradical as a spin filter. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2015, 17, 23378–23383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ueda A; Wasa H; Suzuki S; Okada K; Sato K; Takui T; Morita Y Chiral Stable Phenalenyl Radical: Synthesis, Electronic-Spin Structure, and Optical Properties of [4]Helicene-Structured Diazaphenalenyl. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 6691–6695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sørensen TJ; Nielsen MF; Laursen BW Synthesis and Stability of N,N′‐Dialkyl‐1,13‐dimethoxyquinacridinium (DMQA+): A [4]Helicene with Multiple Redox States. ChemPlusChem, 2014, 79, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ravat P; Ribar P; Rickhaus M; Häussinger D; Neuburger M; Juríček M Spin-Delocalization in a Helical Open-Shell Hydrocarbon. J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 12303–12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kato K; Furukawa K; Mori T; Osuka A Porphyrin-Based Air-Stable Helical Radicals. Chem.- Eur. J 2018, 24, 572–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Liu J; Ravat P; Wagner M; Baumgarten M; Feng X; Müllen K Tetrabenzo[a,f,j,o]perylene: A Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon With An Open‐Shell Singlet Biradical Ground State. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 12442–12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ravat P; Šolomek T; Rickhaus M; Häussinger D; Neuburger M; Baumgarten M; Juríček M Cethrene: A Helically Chiral Biradicaloid Isomer of Heptazethrene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 1183–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zak JK; Miyasaka M; Rajca S; Lapkowski M; Rajca A Radical Cation of Helical, Cross-Conjugated β-Oligothiophene. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 3246–3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wang Y; Zhang H; Pink M; Olankitwanit A; Rajca S; Rajca A Radical Cation and Neutral Radical of Aza-thia[7]helicene with SOMO−HOMO Energy Level Inversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7298–7304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Gallagher N; Zhang H; Junghoefer T; Giangrisostomi E; Ovsyannikov R; Pink M; Rajca S; Casu MB; Rajca A Thermally and Magnetically Robust Triplet Ground State Diradical. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 4764–4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Gallagher NM; Bauer JJ; Pink M; Rajca S; Rajca A High-Spin Organic Diradical with Robust Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 9377–9380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang W; Chen C; Shu C; Rajca S; Wang X; Rajca AS = 1 Tetraazacyclophane Diradical Dication with Robust Stability: a Case of Low Temperature One-Dimensional Antiferromagnetic Chain. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 7820–7826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gallagher NM; Olankitwanit A; Rajca A High-Spin Organic Molecules. J. Org. Chem 2015, 80, 1291–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wingate AJ; Boudouris BW Recent advances in the syntheses of radical‐containing macromolecules. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem 2016, 54, 1875–1894. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Shiraishi K; Rajca A; Pink M; Rajca S π-Conjugated Conjoined Double Helicene via a Sequence of Three Oxidative CC- and NN–Homocouplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 9312–9313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Rajca A Organic diradicals and polyradicals: from spin coupling to magnetism? Chem. Rev 1994, 94, 871–893. [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Baird NC Quantum organic photochemistry. II. Resonance and aromaticity in the lowest 3ππ* state of cyclic hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1972, 94, 4941–4948. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gogonea V; Schleyer P. v. R.; Schreiner PR Consequences of Triplet Aromaticity in 4np-Electron Annulenes: Calculation of Magnetic Shieldings for Open-Shell Species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1998, 37, 1945–1948. [Google Scholar]

- (18).(a) Liu C; Ni Y; Lu X; Li G; Wu J Global Aromaticity in Macrocyclic Polyradicaloids: Hückel’s Rule or Baird’s Rule? Acc. Chem. Res 2019, 52, 2309–2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oh J; Sung YM; Hong Y; Kim D Spectroscopic Diagnosis of Excited-State Aromaticity: Capturing Electronic Structures and Conformations upon Aromaticity Reversal. Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 1349–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rosenberg M; Dahlstrand C; Kils K; Ottosson H Excited State Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity: Opportunities for Photophysical and Photochemical Rationalizations. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 5379–5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Liu C; Sandoval-Salinas ME; Hong Y; Gopalakrishna TY; Phan H; Aratani N; Herng TS; Ding J; Yamada H; Kim D; Casanova D; Wu J Macrocyclic Polyradicaloids with Unusual Super-ring Structure and Global Aromaticity. Chem. 2018, 4, 1586–1595. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cha W-Y; Kim T; Ghosh A; Zhang Z; Ke X-S; Ali R; Lynch VM; Jung J; Kim W; Lee S; Fukuzumi S; Park J-S; Sessler JL; Chandrashekar TK; Kim D Bicyclic Baird-type aromaticity. Nat. Chem 2017, 9, 1243–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dressler JJ; Zhou Z; Marshall JL; Kishi R; Takamuku S; Wei Z; Spisak SN; Nakano M; Petrukhina MA; Haley MM Synthesis of the Unknown Indeno[1,2-a]fluorene Regioisomer: Crystallographic Characterization of Its Dianion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 15363–15367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Fischer LJ; Dutton AS; Winter AH Anomalous effect of non-alternant hydrocarbons on carbocation and carbanion electronic configurations. Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 4231–4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Saunders M; Berger R; Jaffe A; McBride JM; O’Neill J; Breslow R; Hoffmann JM Jr.; Perchonock C; Wasserman E; Hutton RS; Kuck VJ Unsubstituted Cyclopentadienyl Cation, a Ground-state Triplet. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1973, 95, 3017–3018. [Google Scholar]; (b) Borden WT; Davidson ER Potential Surfaces for the Planar Cyclopentadienyl Radical and Cation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101, 3771–3775. [Google Scholar]

- (22).(a) Neugebauer FA; Bock M; Kuhnhauser S; Kurreck H Darstellung. ESR‐ und ENDOR‐Untersuchung von Radikalkationen des Tetraphenylhydrazins, des 5,6‐Dihydro‐5,6‐diphenylbenzo[c]cinnolins und des Benzo[c]benzo[3,4]cinnolino[1,2‐a]cinnolins. Chem. Ber 1986, 119, 980–990. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fisher H; Krieger C; Neugebauer FA Benzo[c]benzo[3,4]cinnolino1[1,2-a]cinnoline, a Chiral Hydrazine Derivative. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 1986, 25, 374–375. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Neugebauer FA, Bamberger S Uber das Tetraphenylhydrazin-Radikalkation. Chem. Ber 1972, 105, 2058–2067. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Rajca A; Miyasaka M; Pink M; Wang H; Rajca S Helically Annelated and Cross-Conjugated Oligothiophenes: Asymmetric Synthesis, Resolution, and Characterization of a Carbon-Sulfur [7]Helicene. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 15211–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Miyasaka M; Pink M; Olankitwanit A; Rajca S; Rajca A Band Gap of Carbon–Sulfur [n]Helicenes. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 3076–3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Connelly NG; Geiger WE Chemical Redox Agents for Organometallic Chemistry. Chem. Rev 1996, 96, 877–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Stoll S; Schweiger A EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson 2006, 178, 42–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).(a) Neese F The ORCA program system. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Comp. Mol. Sci 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sinnecker S; Neese F Spin–Spin Contributions to the Zero-Field Splitting Tensor in Organic Triplets, Carbenes and Biradicals - A Density Functional and Ab Initio Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 12267–12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).(a) Rajca A; Olankitwanit A; Rajca S Triplet Ground State Derivative of Aza-m-Xylylene Diradical with Large Singlet–Triplet Energy Gap. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 4750–4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Olankitwanit A; Rajca S; Rajca A Aza-m-Xylylene Diradical with Increased Steric Protection of the Aminyl Radicals. J. Org. Chem 2015, 80, 5035–5044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Olankitwanit A; Pink M; Rajca S; Rajca A Synthesis of Aza-m-Xylylene Diradicals with Large Singlet-Triplet Energy Gap and Statistical Analyses of their EPR Spectra. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 14277–14288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).(a) Miller LL; Mann KR π-Dimers and π-Stacks in Solution and in Conducting Polymers. Acc. Chem. Res 1996, 29, 417–423. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nishinaga T; Sotome Y Stable Radical Cations and Their π-Dimers Prepared from Ethylene- and Propylene-3,4-dioxythiophene Co-oligomers: Combined Experimental and Theoretical Investigations. J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 7245–7253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Mennucci B; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji H; Caricato M; Li X; Hratchian HP; Izmaylov AF; Bloino J; Zheng G; Sonnenberg JL; Hada M; Ehara M; Toyota K; Fukuda R; Hasegawa J; Ishida M; Nakajima T; Honda Y; Kitao O; Nakai H; Vreven T; Montgomery JA Jr.; Peralta JE; Ogliaro F; Bearpark M; Heyd JJ; Brothers E; Kudin KN; Staroverov VN; Kobayashi R; Normand J; Raghavachari K; Rendell A; Burant JC; Iyengar SS; Tomasi J; Cossi M; Rega N; Millam NJ; Klene M; Knox JE; Cross JB; Bakken V; Adamo C; Jaramillo J; Gomperts R; Stratmann RE; Yazyev O; Austin AJ; Cammi R; Pomelli C; Ochterski JW; Martin RL; Morokuma K; Zakrzewski VG; Voth GA; Salvador P; Dannenberg JJ; Dapprich S; Daniels AD; Farkas Ö; Foresman JB; Ortiz JV; Cioslowski J; Fox DJ Gaussian 09, Revision A.1 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- (33).(a) Gryn’ova G; Coote ML Origin and Scope of Long-Range Stabilizing Interactions and Associated SOMO–HOMO Conversion in Distonic Radical Anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 15392–15403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Franchi P; Mezzina E; Lucarini M SOMO–HOMO Conversion in Distonic Radical Anions: An Experimental Test in Solution by EPR Radical Equilibration Technique. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 1250–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).(a) Manñeru DR; Pal AK; Moreira IPR; Datta SN; Illas F The Triplet-Singlet Gap in the m‑Xylylene Radical: A Not So Simple One. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2014, 10, 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolas Ferré N; Guihéry N; Malrieu JP Spin decontamination of broken-symmetry density functional theory calculations: deeper insight and new formulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2015, 17, 14375–14382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Barone V; Boilleau C; Cacelli I; Ferretti A; Monti S; Prampolini GJ Structure–Properties Relationships in Triplet Ground State Organic Diradicals: A Computational Study. Chem. Theory Comput 2013, 9, 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).(a) Miyasaka M; Rajca A; Pink M; Rajca S Chiral molecular glass: synthesis and characterization of enantiomerically pure thiophene-based [7]helicene. Chem. - Eur. J 2004, 10, 6531–6539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miyasaka M, Rajca A, Pink M; Rajca S Cross-Conjugated Oligothiophenes Derived from The (C2S)n Helix: Asymmetric Synthesis and Structure of Carbon-Sulfur [11]Helicene. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 13806–13807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rajca A; Miyasaka M; Pink M; Xiao S; Rajca S; Das K; Plessel K Functionalized Thiophene-Based [7]Helicene: Chirooptical Properties versus Electron Delocalization. J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 7504–7513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Miyasaka M, Pink M, Rajca S; Rajca A Noncovalent Interactions in the Asymmetric Synthesis of Rigid, Conjugated Helical Structures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 5954–5957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Zhang S; Liu X; Li C; Li L; Song J; Shi J; Morton M; Rajca S; Rajca A; Wang H Thiophene-Based Double Helices: Syntheses, X-ray Structures, and Chiroptical Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 10002–10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Eliel EL; Wilen SH Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds. Wiley-VCH: New York, 1994, Ch. 13, pp. 991–1118 (Table 13.2). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.