Abstract

Background:

This study is the first to examine longitudinal post-treatment outcomes of a placebo-controlled trial of varenicline for alcohol use disorder with comorbid cigarette smoking.

Methods:

Participants were 131 adults (n=39 female) seeking alcohol treatment in a randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled, 16-week multi-site trial of varenicline combined with medical management (O’Malley et al., 2018). Timeline follow-back assessments of alcohol and smoking behavior were conducted at the end of treatment (4 months), with follow-ups at 6, 9, and 12 months. Outcomes were percentage of heavy drinking days (PHDD), percent of participants with no heavy drinking days (NHDD), cotinine-confirmed prolonged smoking abstinence (PA), and good clinical outcome (GCO) on either NHDD or PA.

Results:

Treatment improvements were maintained post-treatment. For the sample overall, PHDD or NHDD did not differ significantly by treatment condition (ps>.13), but varenicline produced higher rates of PA vs. placebo at 4, 9, and 12 months (p<.05). Significant differences were observed by sex: Males had higher rates of NHDD with varenicline (28.8%) vs. placebo (6.4%) at the end of treatment (p=.004), and these effects were maintained at 12 months (varenicline: 40.0% vs. placebo: 19.2%, p=.02). Higher rates of PA were seen for varenicline in both males (8.8%) and females (21.0%) vs. placebo (males/females: 0%) at the end of treatment (p=.05), and this effect was maintained at 12 months for females (varenicline: 21.0% vs. placebo, 0.0%, p=.05).

Conclusions:

Varenicline treatment combined with medical management appears to have enduring benefits for patients with co-occurring alcohol use disorder and cigarette smoking, and these effects may differ by sex.

Keywords: varenicline, alcohol, tobacco, smoking, treatment

Introduction

Co-occurring smoking and heavy alcohol use is a significant public health concern. Cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death (USDHHS, 2014), and smoking combined with heavy alcohol use has negative synergistic health effects, including increased risk for cancer and mortality (Kuper et al, 2000; Lowenfels et al, 1994; Prabhu et al, 2014). Rates of cigarette smoking among individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) are more than twice as high compared to the general population (Dawson, 2000; Grant et al, 2015), and combined heavy alcohol and cigarette use is associated with poor outcomes for both alcohol and tobacco treatment (Abrams et al, 1992; Cook et al, 2012; Fucito et al, 2012; Hintz & Mann, 2007; Kahler et al, 2009; Leeman et al, 2008). Despite the frequent co-occurrence and substantial health risks of these behaviors, there are currently no pharmacotherapies that are approved to treat both alcohol and tobacco use.

Varenicline, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, has shown promise for addressing both alcohol and tobacco use. Varenicline is a partial agonist that acts on the nicotinic acetylcholine system (Rollema et al, 2007), a system that is involved in the rewarding effects of both nicotine and alcohol (Hendrickson et al, 2013; Lě et al, 2000). Varenicline has been shown to reduce alcohol consumption in preclinical (Ericson et al, 2009; Feduccia et al, 2014; Kaminski & Weerts, 2014) and preliminary clinical studies (Fucito et al, 2011; McKee et al, 2009; Mitchell et al, 2012). Two randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials have evaluated varenicline for individuals with AUD among smokers and non-smokers, with mixed results on alcohol outcomes (de Bejczy et al, 2015; Litten et al, 2013). A separate double-placebo controlled study among smokers with current substance use disorders found a benefit of varenicline compared to nicotine patch for smoking cessation but no benefit on drug or alcohol use outcomes, although these participants were abstinent from alcohol at the initiation of smoking treatment (Rohsenow et al, 2017). Only one published trial to date has exclusively enrolled current smokers with AUD (O’Malley et al, 2018). Participants in this study were seeking treatment for alcohol use but not smoking. Results from this trial indicated that varenicline, compared to placebo, reduced heavy drinking by the end of treatment specifically in men and promoted smoking cessation in the sample overall (O’Malley et al, 2018).

Thus, there is growing but mixed evidence that varenicline is effective at addressing the combined use of alcohol and tobacco. To date, studies have focused on evaluating the net benefit of varenicline (vs. placebo) specifically for smoking cessation over time (Rosen et al, 2018). The current study builds on these findings by examining the longitudinal effects of varenicline in adults as a potential treatment for both heavy drinking and comorbid cigarette smoking. The current study utilizes follow-up data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 16-week clinical trial of daily varenicline among smokers with AUD seeking alcohol treatment (O’Malley et al, 2018). We evaluated the effects of treatment condition on percentage of heavy drinking days (PHDD), percent of participants with no heavy drinking days (NHDD), and rates of prolonged smoking abstinence (PA) for up to one-year after the start of treatment. Given that varenicline may promote change in alcohol or smoking behavior, the main trial also examined an exploratory integrated responder outcome, defined as achieving a good clinical outcome (GCO) on either alcohol (NHDD) or smoking (PA) during the last 4 weeks of treatment (O’Malley et al, 2018). This integrated exploratory outcome is based on the FDA recommendations for evaluating treatment responders as a clinical efficacy endpoint (Food and Drug Administration, 2015); improvements in either alcohol or smoking outcomes from varenicline treatment likely has substantial public health benefits given the significant risk of these co-occurring behaviors. Results from the main trial indicated a significant benefit for men taking varenicline vs. placebo on the integrated outcome during the 16-week treatment period, so we also examined the longitudinal effects following medication discontinuation on this integrated good clinical outcome at time points through one-year post-treatment. We also a priori examined these longitudinal effects separately by sex, based on findings from the main trial (O’Malley et al., 2018) and evidence that men and women differ in smoking and alcohol use and their response to treatment (Erol & Karpyak, 2015; Greenfield et al, 2010; Jamal et al, 2018; McKee et al, 2015; Smith et al, 2017; Verplaetse et al, 2018).

Materials and Methods

Study Objectives and Design

The main 16-week trial compared the efficacy and safety of varenicline tartrate (1mg twice daily) vs. placebo combined with medical management (MM) in adults with alcohol use disorder and comorbid cigarette smoking who were seeking treatment for alcohol use (O’Malley et al, 2018). Participants were enrolled between September 2012 and August 2015. Randomization to 2 mg daily of varenicline tartrate (n = 64) or matching placebo pills (n = 67) was stratified by site and sex within site (block size of 4). Participants, MM treatment providers, and research staff were blind to the treatment assignment throughout the study. Medication titration followed standard doses: 0.5 mg once daily for 3 days, 0.5 mg twice daily for 4 days, and 1 mg twice daily for the remainder of the 16-week treatment. After week 16, use of medication was tapered over 2 weeks (0.5 mg twice daily and then 0.5 mg daily). Participants also received 12 brief counseling sessions with a healthcare professional for medical management (MM) (Zweben et al, 2017) adapted from the COMBINE study (Anton et al, 2006; Pettinati et al, 2005). The first 4 weeks of treatment focused on medication adherence and stabilization on medication. The remaining 12 weeks focused on changing alcohol use. Smoking cessation was not addressed during the treatment period, but a faxed referral to the state tobacco quitline was offered at the end of the 16-week treatment period. Medication dose reductions were permitted, and those who discontinued medication could continue research assessments and attend counseling appointments. After treatment termination, participants were seen for follow-up assessments at 6, 9, and 12 months from the treatment start date. In the longitudinal follow-up analyses, we examined the effect of study condition on alcohol and smoking behavior from the end of treatment up to 12 months after the first treatment session.

Participants

A full description of participants enrolled in the main trial is provided in O’Malley et al., 2018. Participants who were seeking treatment for alcohol use were recruited from two sites: New Haven and New York City. Eligible participants were: 1) 18–70 years old; 2) met alcohol-dependence criteria, according to the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000); 3) reported heavy drinking ≥ 2 times per week during the previous 90 days and ≤ 7 consecutive days of abstinence from alcohol prior to the intake; 4) smoking cigarettes ≥ 2 times per week, verified with urine cotinine level of ≥ 30 ng/mL or plasma cotinine level of ≥ 6 ng/mL. Exclusion criteria included current, clinically significant disease or abnormality; diagnosis of a serious psychiatric illness; current suicidal ideation or lifetime history of suicidal behavior; risk of aggression; current diagnosis of drug dependence, except for nicotine or marijuana; risk of clinically significant alcohol withdrawal; medications in the past 3 months to treat alcohol or tobacco dependence; and psychotropic medications in the past month, except a stable dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor was allowed. Women of childbearing age could not be pregnant or nursing and had to be using effective contraception. The CONSORT diagram depicting enrollment into the trial has been published previously (O’Malley et al, 2018).

Assessments

The current analyses focus on the measures described below. Additional measures were collected as a part of the larger trial. Trained research staff administered the Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) Interview (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) to record self-reported quantity and frequency of alcohol and cigarette use at intake for the previous 90 days and at each subsequent visit. Outcome variables were calculated from the TLFB data at each time point. Carbon monoxide and plasma cotinine were measured at intake and subsequent visits to confirm smoking status. Participants were also asked to report any additional methods they may have used to quit drinking and/or smoking during the follow-up period (e.g., pharmacotherapy, treatment programs, quitline, “cold turkey”).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics and other methods used to address alcohol or smoking during the follow-up period. Alcohol and smoking outcomes were calculated at each time point: 4 month (end of treatment), 6 month, 9 month, 12 month. The primary alcohol use outcomes in the main paper (O’Malley et al, 2018) (percentage of heavy drinking days (PHDD) and percent of participants achieving no heavy drinking days (NHDD)) were assessed in the last 8 weeks of treatment based on FDA guidelines (Food and Drug Administration, 2015), which allow for an initial grace period prior to evaluating treatment outcome. A heavy drinking day was defined as consuming ≥ 5 standard drinks for men and ≥ 4 standard drinks for women. The primary smoking outcome in the main paper was biochemically confirmed (plasma cotinine levels < 6 ng/mL) prolonged smoking abstinence (PA) in the last 4 weeks of treatment, consistent with prior studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of varenicline for smoking cessation (Anthenelli et al, 2016; Gonzales et al, 2006; Jorenby et al, 2006). For consistency with the primary outcome paper, we maintained these same time frames for assessing alcohol (last 8 weeks) and smoking (last 4 weeks) outcomes at each point during the follow-up period. Consistent with the main paper, we also examined an exploratory integrated responder outcome, using definitions of achieving a good clinical outcome (GCO) on either alcohol (NHDD) or smoking (PA) assessed on an equivalent time frame of the last 4 weeks at each follow-up through one-year post-treatment. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All tests were 2-tailed, and the significance level was .05.

PHDD was analyzed using a linear mixed model based on available data, with treatment group (varenicline or placebo), site (New York or New Haven), sex (male or female), time (baseline, 4 month, 6 month, 9 month, 12 month), and all of their interactions as categorical predictors. We used overall F tests for interactive and main effects in the models. PHDD was log-transformed to adjust for positive skew of the data, and the model was fit on the transformed variable. For categorical outcomes (NHDD, PA, GCO), chi-square tests were used by time point when expected counts were above 5 and Fisher’s exact tests otherwise. For these binary outcomes, missing data were imputed as failed, consistent with intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses. Similar findings were obtained in a sensitivity analysis of completers only, excluding missing data, so results are presented from ITT analyses. Use of additional methods to quit drinking or smoking during the follow-up period were examined in separate models as predictors of alcohol and smoking outcomes at each follow-up time point.

Results

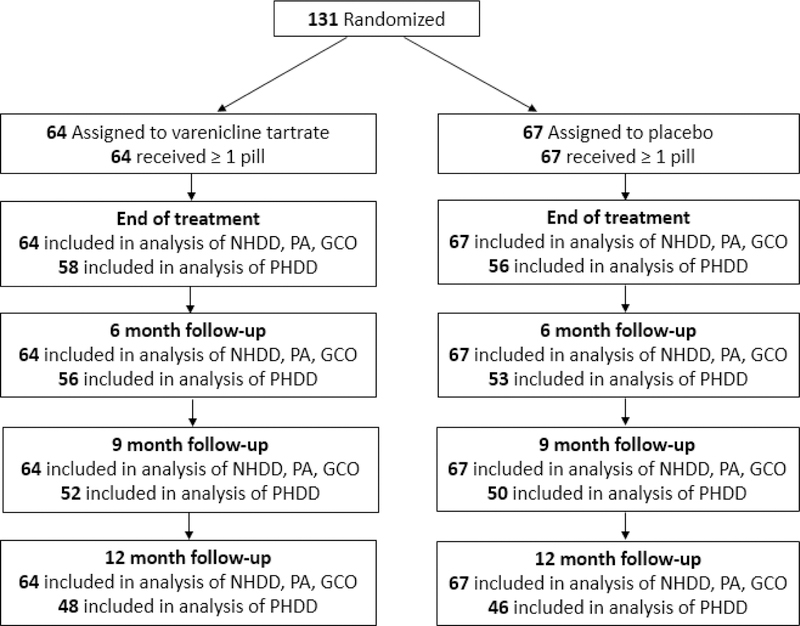

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram depicting retention through follow-up of the 131 patients who were randomized. In total, analyses of PHDD outcomes were conducted among the N=114 (87.0%) who provided data at the end of treatment (4 month follow-up), N=109 (83.2%) who provided data at the 6 month follow-up, N=102 (77.9%) who provided data at the 9 month follow-up, and N=94 (71.8%) who provided data at the 12 month follow-up. All randomized participants (N=131) were included in analyses of binary outcomes (NHDD, PA, GCO) where missing data were treated as failed.

Figure 1:

Study Follow-up Flow Diagram by Treatment Condition. Note: NHDD=percent of participants with no heavy drinking days, PA=prolonged smoking abstinence, GCO=good clinical outcome (either NHDD or PA), PHDD=percentage of heavy drinking days. Missing data on binary outcomes (NHDD, PA, GCO) are treated as failed.

Table 1 reports baseline characteristics among the full randomized sample. There were no significant differences between treatment groups on these baseline characteristics, including alcohol use and smoking variables. See O’Malley et al., 2018 for detailed baseline characteristics reported by treatment condition and sex.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Among All Randomized Participants (N=131)

| Variable | N (%) or M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 42.7(11.70) |

| Male, N (%) | 92 (70.2%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 51 (38.9%) |

| Black/African American | 72 (55.0%) |

| Other | 8 (6.1%) |

| Highest level of education1 | |

| High school/GED or less | 50 (38.5%) |

| Some college | 44 (33.8%) |

| College or post baccalaureate degree | 36 (27.7%) |

| Employed full- or part-time | 68 (51.9%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 78 (59.5%) |

| Married/Cohabitating | 35 (26.7%) |

| Other | 18 (13.8%) |

| Alcohol use characteristics2 | |

| Drinks per drinking day, mean (SD) | 8.7 (4.20) |

| Percentage of heavy drinking days, mean (SD) | 62.6 (24.87) |

| Percent days abstinent from alcohol, mean (SD) | 20.5 (18.46) |

| Smoking characteristics3 | |

| Cigarettes per smoking day, mean (SD) | 11.6 (7.24) |

| FTND score, mean (SD) | 4.4 (2.6) |

| Daily smoker, N (%) | 118 (90.1%) |

Note:

Missing education data for n=1.

Baseline alcohol use characteristics were assessed for the 8 weeks prior to the intake.

Baseline smoking characteristics were assessed for the 4 weeks prior to the intake.

Alcohol Outcomes

PHDD was log-transformed to adjust for positive skew of the data, and results are presented for the transformed variable. To further facilitate interpretation of the PHDD data, Table 2 presents the median and interquartile ranges for PHDD at each time point. For the sample overall, there were no significant differences between treatment groups over time in PHDD (treatment*time: F(4,99.3)=0.27, p=.89) or NHDD outcomes (χ2(1, N=131) < 2.31, ps > 0.13 for treatment comparisons at each time point). Regardless of treatment condition, participants maintained improvements in alcohol use outcomes from the end of treatment through the follow-up period. There was a significant main effect of time (F(4,99.3)=64.09, p<.0001), such that PHDD decreased significantly from the end of treatment to the 12-month follow-up. While we could not fit a general model over time for the binary outcome of NHDD due to small cell counts, rates of achieving NHDD increased during the post-treatment follow-up for both the varenicline and placebo conditions; the proportion of the sample with no heavy drinking days increased from 21.8% to 34.4% for the varenicline group (p=0.07, McNemar’s test) and from 11.9% to 25.4% for the placebo group (p=0.02, McNemar’s test) from the end of treatment to the 12-month follow-up.

Table 2.

Median and Interquartile Ranges for Percentage of Heavy Drinking Days (PHDD) by Medication, Time, and Sex

| Baseline | Month 4 | Month 6 | Month 9 | Month 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Varenicline | 58.9 (39.3, 7.5) |

3.6 (0.0, 28.6) |

1.8 (0.0, 33.9) |

3.6 (0.0, 26.8) |

0.0 (0.0, 7.1) |

| Placebo | 60.7 (42.9, 82.1) |

10.7 (30.4, 3.6) |

5.4 (0.0, 25.0) |

12.5 (0.0, 35.7) |

5.4 (0.0, 21.4) |

|

| Females | Varenicline | 66.1 (46.4, 85.7) |

17.9 (3.6, 41.1) |

5.4 (3.6, 26.7) |

12.5 (0.0, 35.7) |

5.4 (0.0, 28.6) |

| Placebo | 65.2 (35.7, 88.4) |

5.8 (0.0, 39.3) |

0.0 (0.0, 28.6) |

3.6 (0.0, 26.8) |

1.0 (0.0, 23.2) |

|

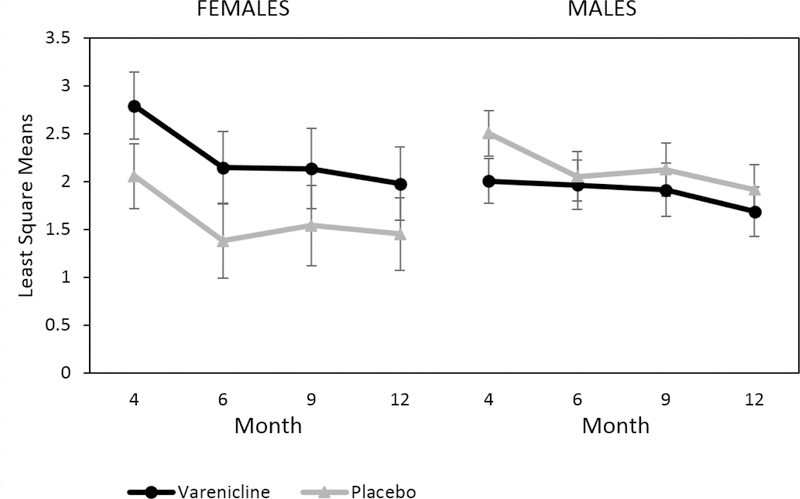

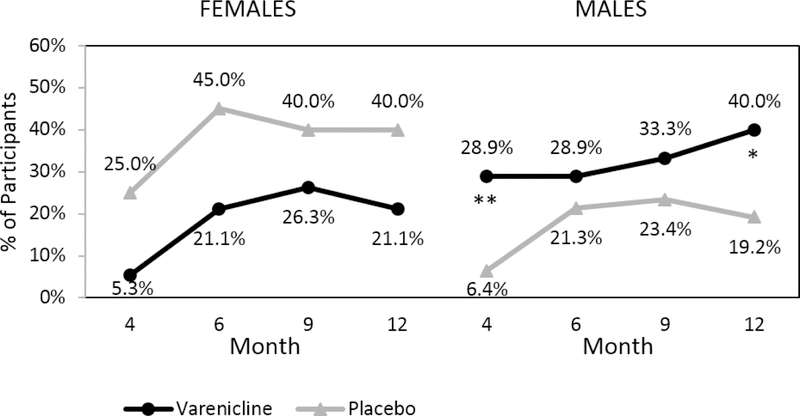

Additionally, there were no significant treatment group differences in PHDD when examined by sex over time (treatment*sex*time F(4,99.3)=1.20, p=.32) (Figure 2). However, there was a significant treatment effect by sex for NHDD (treatment*sex Month 4: χ2(1, N=131)=7.02, p=.008; Month 12: χ2(1, N=131)=6.60, p=.01); significantly higher rates of NHDD were observed among men in the varenicline group compared to the placebo group at the end of treatment (χ2(1, N=92)=8.11, p=.004) and month 12 (χ2(1, N=92)=4.82, p=.03) (Figure 3). Although women in the placebo group had higher rates of achieving NHDD compared to the varenicline group, these differences were not statistically significant at any time point (all ps>.11).

Figure 2:

Least Square Means of Log-transformed Percentage of Heavy Drinking Days (PHDD) by Medication, Time, and Sex. Note: PHDD calculated during the last 8 weeks at each time point. Month 4 corresponds to the end of treatment and medication discontinuation.

Figure 3:

Percent of Participants with No Heavy Drinking Days (NHDD) by Medication, Time, and Sex. Note: NHDD calculated during the last 8 weeks at each time point with missing data treated as failed. Month 4 corresponds to the end of treatment and medication discontinuation. **p≤.01, *p≤.05.

Smoking Outcomes

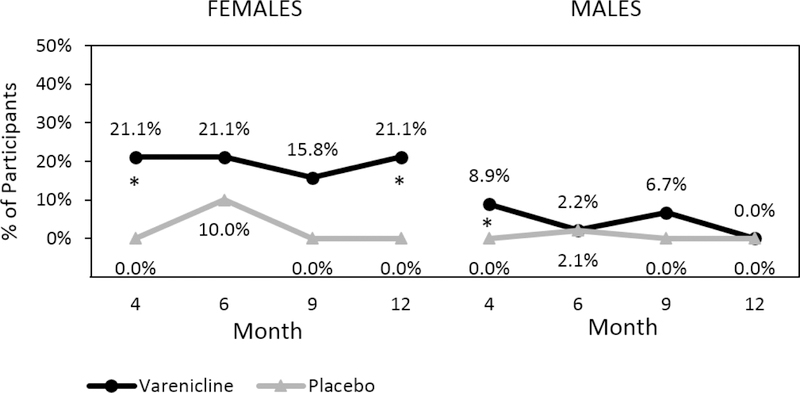

Despite the fact that participants were not seeking treatment for their smoking, there was a significant overall treatment effect for the full sample on cotinine confirmed prolonged smoking abstinence (PA), with higher rates of PA observed in the varenicline vs. placebo group at month 4 (varenicline: 12.5% vs. placebo: 0.0%, Fisher’s Exact Test p=.003), month 9 (varenicline: 9.4% vs. placebo: 0.0%, Fisher’s Exact Test p=.01), and month 12 (varenicline: 6.3% vs. 0.0%, Fisher’s Exact Test p=.05). This benefit of varenicline (vs. placebo) is seen in men early on during the follow-up period (month 4, Fisher’s Exact Test p=.05), and in women this benefit is observed at month 4 (Fisher’s Exact Test p=.05) and maintained at month 12 (Fisher’s Exact Test p=.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Percent of Participants with Prolonged Smoking Abstinence (PA) by Medication, Time, and Sex. Note: PA, defined as self-reported smoking abstinence in the last 4 weeks at each time point, confirmed by plasma cotinine levels < 6 ng/mL with missing data treated as smoking. Month 4 corresponds to the end of treatment and medication discontinuation. *p≤.05.

Integrated Good Clinical Outcomes

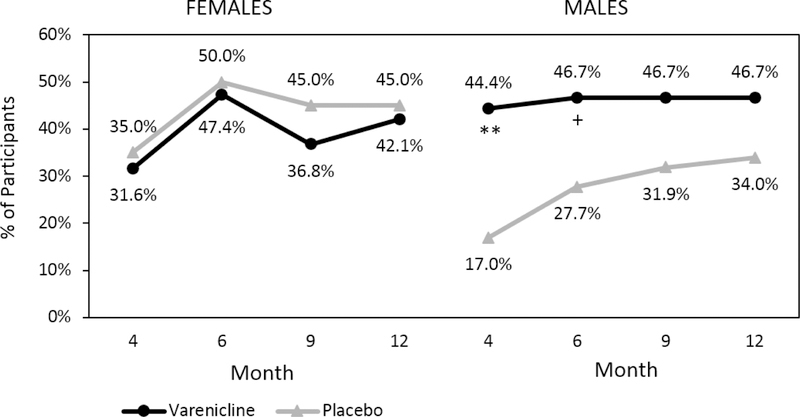

There was a significant overall treatment effect for the full sample on good clinical outcome (GCO: achieving either NHDD or PA) at the end of treatment, month 4 (varenicline: 40.6% vs. placebo: 22.4%, χ2(1, N=131)=5.06, p=.02). Additionally, a greater proportion of men on varenicline vs. placebo achieved a GCO early on during the follow-up period (month 4, χ2(1, N=131)=8.17, p=.004; month 6, χ2(1, N=131)=3.56, p=.06) (Figure 5). There were no significant differences by treatment group in GCO for women across the time points (χ2(1, N=131)<0.26, ps>.60). However, both men and women in the sample appeared to maintain improvements in GCO throughout the follow-up period, regardless of treatment condition.

Figure 5:

Percent of Participants with Good Clinical Outcome on Either Alcohol (NHDD) or Smoking (SA) by Medication, Time, and Sex. Note: Good clinical outcome (GCO) defined as achieving positive outcomes on either alcohol (NHDD) or smoking (PA) during the last 4 weeks at each time point with missing data treated as failed. Month 4 corresponds to the end of treatment and medication discontinuation. **p≤.01; +p=.06

Additional Methods to Address Alcohol and Smoking During Follow-Up

We also examined other methods used to address alcohol or smoking after the end of treatment, as reported by N=107 participants during follow-up (see Supplemental Table). Rates of endorsing additional treatment methods during the follow-up period did not differ significantly by study treatment condition or sex (all ps>.25). Overall, 45.8% of the sample reported using additional treatments to address alcohol or smoking during the follow-up period, although use of additional treatment methods did not significantly predict alcohol, smoking, or integrated good clinical outcomes (all ps>.10).

Discussion

This study is the first to report the longitudinal effects following medication discontinuation in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of varenicline in adults with alcohol use disorder and comorbid cigarette smoking who were seeking treatment for alcohol use. Following 16-weeks of varenicline or placebo combined with medical management, alcohol and smoking outcomes were assessed at 6, 9, and 12-month follow-up visits. Overall, participants maintained improvements from the end of treatment through the follow-up period across both medication conditions. Furthermore, a substantial proportion of participants achieved a good clinical outcome on either alcohol or smoking outcomes that was maintained after medication discontinuation. The current findings extend the results from the main trial (O’Malley et al, 2018), and indicate that men and women with co-occurring AUD and cigarette smoking may derive differential benefit from varenicline treatment. Although this study is limited by a small proportion of women, findings indicate that men in the varenicline condition had better alcohol outcomes compared to those in the placebo condition at the end of treatment that were maintained through the 12-month follow-up; whereas women in the varenicline condition had significantly higher rates of prolonged smoking abstinence compared to those in the placebo condition at the end of treatment and at the 12-month follow-up. These findings indicate that varenicline treatment outcomes may differ by sex and that these effects are maintained up to one year after the start of treatment.

The observation that positive treatment outcomes were maintained or continued to improve during the post-treatment period regardless of medication condition may indicate that individuals who make initial gains during treatment are more likely to maintain these benefits, in line with research showing that early treatment success predicts positive long-term outcomes (Ashare et al, 2013; Dunn et al, 2016; Nides et al, 1995; Weisner et al, 2003). These findings differ somewhat from the results of a recent meta-analysis of smoking cessation trials that indicated a sustained benefit of varenicline (vs. placebo) through 12 months, but a decline in quit rates across both groups over time (Rosen et al, 2018). The sustained effects in the current study may also indicate a longitudinal benefit of behavioral counseling since all participants received 12 weeks of medical management for alcohol use (Zweben et al, 2017), a behavioral intervention adapted from the COMBINE study (Anton et al, 2006; Pettinati et al, 2005). Other studies indicate that behavioral treatments for substance use can produce lasting benefits beyond the end of treatment (e.g., (Carroll et al, 1994; O’Malley et al, 1996). Additional research is needed to identify characteristics of patients who achieve and maintain positive outcomes from varenicline and medical management to inform ways to optimize treatment delivery.

Results from the current study differ from the other two randomized placebo-controlled trials of varenicline for individuals with AUD. One trial found that varenicline reduced alcohol use by the end of treatment compared to placebo (Litten et al, 2013), and this effect was not moderated by sex (Falk et al, 2015), while another trial did not identify a significant advantage of varenicline over placebo on alcohol outcomes (de Bejczy et al, 2015). However, our findings indicate that varenicline (vs. placebo) had a benefit for reducing alcohol use in males but not females and this effect was maintained through the 12-month follow-up, while females had a more sustained benefit for smoking outcomes in the varenicline versus placebo group. Contrary to the samples used in other studies (de Bejczy et al, 2015; Litten et al, 2013), which included smokers and non-smokers, the current study exclusively enrolled smokers, which may contribute to the different findings. Our findings align with other evidence of sex differences with varenicline that indicate a greater efficacy among women compared to men for smoking cessation outcomes (McKee et al, 2015). However, the small sample size of women should be noted when considering the findings from the current study. Additionally, sex differences in the observed outcomes may be due to other factors not related to medication condition. As reported in the main trial (O’Malley et al, 2018), women had greater baseline severity of alcohol dependence and lower nicotine dependence and smoking intensity compared to men. Women were also more likely to reduce or discontinue their medication dose. These differences may have also influenced the observed outcomes during follow-up. Additional studies are needed to replicate the current findings to further understand the long-term benefit of varenicline treatment for co-occurring alcohol use and cigarette smoking and whether these effects may differ by sex.

Longitudinal alcohol and smoking outcomes were not influenced by additional methods that participants used to address alcohol use or smoking during the follow-up period. Our findings suggest that while many individuals are still engaged in efforts to change their alcohol and smoking behavior during the post-treatment period and report trying additional methods to change their behavior, most are not utilizing evidence-based treatments to support this effort. Extended efforts and new ways to increase patient access and utilization of evidence-based treatments may be important for continuing to improve outcomes for these health behaviors.

Study findings should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, although outcomes were biochemically confirmed for smoking, alcohol outcomes were based on self-report data during the follow-up period. Second, there was a small sample size of women, which limits the statistical power to examine sex differences and limits the reliability of model estimates. Due to sparse data, we were unable to fit models with all interactions for the categorical outcomes, so results are presented from chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests comparing these outcomes by sex and treatment condition at each time point. Larger trials are needed to further explore these findings and examine additional demographic factors that may influence outcomes. Furthermore, the current analyses present treatment differences in outcomes at each time point and do not correct for multiple comparisons as the outcomes are highly correlated across timepoints. Future investigations may benefit from examining trajectories across time to identify patterns of alcohol and smoking behavior and predictors of treatment outcome. Lastly, the current study investigated longitudinal effects following 16 weeks of treatment, and additional research is needed to identify the optimal duration of varenicline treatment to promote long-term clinical benefit for co-occurring alcohol and smoking behavior.

Conclusions

This study provides new information about the longitudinal effects following treatment with varenicline and medical management for patients with co-occurring alcohol use disorder and cigarette smoking. Varenicline resulted in significant reductions in heavy drinking among men during treatment compared to placebo, and these effects endured through the 8-month period after medication discontinuation. Although smoking cessation counseling was not provided in this study, varenicline promoted significantly higher rates of prolonged smoking abstinence in the total sample compared to placebo at the end of treatment, and this effect was maintained at the 12-month follow-up for women. Improving either alcohol or smoking outcomes has substantial public health benefits given the significant risk of these co-occurring behaviors. Varenicline treatment combined with medical management appears to have enduring benefits for individuals with alcohol use disorder who also smoke cigarettes and should be considered when treating these co-occurring health behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contribution to the conduct of this trial: Armin Baier, JD, MSW, Parallax Center; Douglas Bass, MD, Parallax Center; David Forman, MSW, Columbia University; Elaine LaVelle, MS, Yale School of Medicine; Susan Neveu, Yale School of Medicine; David Ockert, Ph.D., Parallax Center; Denise Romano, APRN, MSN, MA, ADS-RT, Yale School of Medicine. Pfizer generously donated varenicline and placebo pills.

Funding Sources: This trial was supported in part by grants R01AA020388, R01AA020389, P50AA012870, T32DA019426, K23AA020000, K05AA014715 from the National Institutes of Health and by the State of Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Pfizer generously donated varenicline and placebo pills.

Trial Registration clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01553136

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health, the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, or the State of Connecticut.

Conflict of Interest/Disclosures: Dr. O’Malley reported having been a consultant or an advisory board member for Alkermes, Amygdala, Arkeo, Cerecor, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Opiant, Pfizer; honoraria from the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative supported by Abbott, Amygdala, Ethylpharm, Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, and Indivior and from the Emmes Corporation as a DSMB member for the NIDA Clinical Trials Network; a coinvestigator on studies receiving donated medications from Astra Zeneca, Norvatis; a contract from Lilly; and a scientific panel member for Hazelden Foundation. Dr. Gueorguieva discloses consulting fees for Palo Alto Health Sciences, Knopp Biosciences and Mathematica Policy Research, royalties from book “Statistical Methods in Psychiatry and Related Fields” published by CRC Press, honorarium from the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology’s Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative, and a provisional patent submission by Yale University: Chekroud, AM., Gueorguieva, R., & Krystal, JH. “Treatment Selection for Major Depressive Disorder” [filing date 3rd June 2016, USPTO docket number Y0087.70116US00]. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- Abrams DB, Rohsenow DJ, Niaura RS, Pedraza M, Longabaugh R, Beattie MC, Binkoff JA, Noel NE & Monti PM (1992) Smoking and treatment outcome for alcoholics: Effects on coping skills, urge to drink, and drinking rates. Behavior Therapy, 23(2), 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, St Aubin L, McRae T, Lawrence D, Ascher J, Russ C, Krishen A & Evins AE (2016) Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The Lancet, 387(10037), 2507–2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA & LoCastro JS (2006) Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 295(17), 2003–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashare RL, Wileyto EP, Perkins KA & Schnoll RA (2013) The first seven days of a quit attempt predicts relapse: Validation of a measure for screening medications for nicotine dependence. Journal of addiction medicine, 7(4), 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW & Gawin F (1994) One-year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence: Delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Archives of general psychiatry, 51(12), 989–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2017) Quitting Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2000–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(52), 1457–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A & Kranzler HR (2007) Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and alcohol dependence, 86(2–3), 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JW, Fucito LM, Piasecki TM, Piper ME, Schlam TR, Berg KM & Baker TB (2012) Relations of alcohol consumption with smoking cessation milestones and tobacco dependence. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 80(6), 1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA (2000) Drinking as a risk factor for sustained smoking. Drug and alcohol dependence, 59(3), 235–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bejczy A, Löf E, Walther L, Guterstam J, Hammarberg A, Asanovska G, Franck J, Isaksson A & Söderpalm B (2015) Varenicline for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(11), 2189–2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KE, Harrison JA, Leoutsakos J-M, Han D & Strain EC (2016) Continuous abstinence during early alcohol treatment is significantly associated with positive treatment outcomes, independent of duration of abstinence. Alcohol and alcoholism, 52(1), 72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Löf E, Stomberg R & Söderpalm B (2009) The smoking cessation medication varenicline attenuates alcohol and nicotine interactions in the rat mesolimbic dopamine system. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 329(1), 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol A & Karpyak VM (2015) Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug and alcohol dependence, 156, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Castle I-JP, Ryan M, Fertig J & Litten RZ (2015) Moderators of varenicline treatment effects in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for alcohol dependence: an exploratory analysis. Journal of addiction medicine, 9(4), 296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feduccia A, Simms J, Mill D, Yi H & Bartlett S (2014) Varenicline decreases ethanol intake and increases dopamine release via neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nucleus accumbens. British journal of pharmacology, 171(14), 3420–3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update (2008). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration (2015) Alcoholism: Developing drugs for treatment (No. FDA D-0152–001) Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Fucito LM, Park A, Gulliver SB, Mattson ME, Gueorguieva RV & O’Malley SS (2012) Cigarette smoking predicts differential benefit from naltrexone for alcohol dependence. Biological psychiatry, 72(10), 832–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucito LM, Toll BA, Wu R, Romano DM, Tek E & O’Malley SS (2011) A preliminary investigation of varenicline for heavy drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology, 215(4), 655–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, Watsky EJ, Gong J, Williams KE & Reeves KR (2006) Varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 296(1), 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM & Huang B (2015) Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA psychiatry, 72(8), 757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Pettinati HM, O’Malley S, Randall PK & Randall CL (2010) Gender differences in alcohol treatment: an analysis of outcome from the COMBINE study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(10), 1803–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann‐Boyce J, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Begh R, Stead LF & Hajek P (2016) Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. The Cochrane Library(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson LM, Guildford MJ & Tapper AR (2013) Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: common molecular substrates of nicotine and alcohol dependence. Frontiers in psychiatry, 4, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintz T & Mann K (2007) Long-term behavior in treated alcoholism: Evidence for beneficial carry-over effects of abstinence from smoking on alcohol use and vice versa. Addictive behaviors, 32(12), 3093–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, Homa DM, Babb SD, King BA & Neff LJ (2018) Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(2), 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR & Group VPS (2006) Efficacy of varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 296(1), 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Borland R, Hyland A, McKee SA, Thompson ME & Cummings KM (2009) Alcohol consumption and quitting smoking in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Drug and alcohol dependence, 100(3), 214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhoran S & Glantz SA (2016) E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 4(2), 116–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski BJ & Weerts EM (2014) The effects of varenicline on alcohol seeking and self‐administration in baboons. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(2), 376–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper H, Tzonou A, Kaklamani E, Hsieh CC, Lagiou P, Adami HO, Trichopoulos D & Stuver SO (2000) Tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and their interaction in the causation of hepatocellular carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer, 85(4), 498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lě A, Corrigall W, Watchus J, Harding S, Juzytsch W & Li TK (2000) Involvement of nicotinic receptors in alcohol self‐administration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(2), 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, McKee SA, Toll BA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Cooney JL, Makuch RW & O’Malley SS (2008) Risk factors for treatment failure in smokers: relationship to alcohol use and to lifetime history of an alcohol use disorder. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10(12), 1793–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Fertig JB, Falk DE, Johnson B, Dunn KE, Green AI, Pettinati HM, Ciraulo DA & Sarid-Segal O (2013) A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy of varenicline tartrate for alcohol dependence. Journal of addiction medicine, 7(4), 277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, DiMagno EP, Andrén-Sandberg Å, Domellöf L & Di Francesco V (1994) Prognosis of chronic pancreatitis: an international multicenter study. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 89(9). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malas M, van der Tempel J, Schwartz R, Minichiello A, Lightfoot C, Noormohamed A, Andrews J, Zawertailo L & Ferrence R (2016) Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18(10), 1926–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Harrison EL, O’Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Shi J, Tetrault JM, Picciotto MR, Petrakis IL, Estevez N & Balchunas E (2009) Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biological psychiatry, 66(2), 185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Smith PH, Kaufman M, Mazure CM & Weinberger AH (2015) Sex differences in varenicline efficacy for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18(5), 1002–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Teague CH, Kayser AS, Bartlett SE & Fields HL (2012) Varenicline decreases alcohol consumption in heavy-drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology, 223(3), 299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nides MA, Rakos RF, Gonzales D, Murray RP, Tashkin DP, Bjornson-Benson WM, Lindgren P & Connett JE (1995) Predictors of initial smoking cessation and relapse through the first 2 years of the Lung Health Study. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 63(1), 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, Rode S, Schottenfeld R, Meyer RE & Rounsaville B (1996) Six-month follow-up of naltrexone and psychotherapy for alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53(3), 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Zweben A, Fucito LM, Wu R, Piepmeier ME, Ockert DM, Bold KW, Petrakis I, Muvvala S & Jatlow P (2018) Effect of varenicline combined with medical management on alcohol use disorder with comorbid cigarette smoking: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 75(2), 129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Weiss RD, Dundon W, Miller WR, Donovan D, Ernst DB & Rounsaville BJ (2005) A structured approach to medical management: a psychosocial intervention to support pharmacotherapy in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement(15), 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu A, Obi KO & Rubenstein JH (2014) The synergistic effects of alcohol and tobacco consumption on the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. The American journal of gastroenterology, 109(6), 822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Tidey JW, Martin RA, Colby SM, Swift RM, Leggio L & Monti PM (2017) Varenicline versus nicotine patch with brief advice for smokers with substance use disorders with or without depression: effects on smoking, substance use and depressive symptoms. Addiction, 112(10), 1808–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Chambers L, Coe J, Glowa J, Hurst R, Lebel L, Lu Y, Mansbach R, Mather R & Rovetti C (2007) Pharmacological profile of the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology, 52(3), 985–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LJ, Galili T, Kott J, Goodman M & Freedman LS (2018) Diminishing benefit of smoking cessation medications during the first year: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction, 113(5), 805–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Weinberger AH, Zhang J, Emme E, Mazure CM & McKee SA (2017) Sex differences in smoking cessation pharmacotherapy comparative efficacy: a network meta-analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(3), 273–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC & Sobell MB (1992) Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption

- USDHHS (2014) The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Verplaetse TL, Morris ED, McKee SA & Cosgrove KP (2018) Sex differences in the nicotinic acetylcholine and dopamine receptor systems underlying tobacco smoking addiction. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weisner C, Ray GT, Mertens JR, Satre DD & Moore C (2003) Short-term alcohol and drug treatment outcomes predict long-term outcome. Drug and alcohol dependence, 71(3), 281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweben A, Piepmeier M, Fucito L & O’Malley S (2017) The clinical utility of the Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ) in an alcohol pharmacotherapy trial. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 77, 72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.