Abstract

Hypertension is sexually dimorphic and modified by removal of endogenous sex steroids. This study tested the hypothesis that endogenous gonadal hormones exert differential effects on protein expression in the kidney and mesentery of SHR. At ~5 weeks of age male and female SHR underwent sham operation, orchidectomy, or ovariectomy (OVX). At 20–23 weeks of age, mean arterial pressure (MAP) was measured in conscious rats. The mesenteric arterial tree and kidneys were collected, processed for Western blots, and probed for Cu Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1), soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH), and Alpha 2A adrenergic receptor (A2AR) expression. MAP was unaffected by ovariectomy (Sham 164 ± 4: Ovariecttomy 159 ± 3 mm Hg). MAP was reduced by orchidectomy (Sham 189 ± 5:Orchidectomy 167 ± 2 mm Hg). In mesenteric artery, SOD1 expression was greater in male versus female SHR. Orchidectomy increased while ovariectomy decreased SOD1 expression. The kidney exhibited a different pattern of response. SOD1 expression was reduced in male compared to female SHR but gonadectomy had no effect. sEH expression was not significantly different among the groups in mesenteric artery. In kidney, sEH expression was greater in males compared to females. Ovariectomy but not orchidectomy increased sEH expression. A2AR expression was greater in female than male SHR in mesentery artery and kidney. Gonadectomy had no effect in either tissue. We conclude that sexually dimorphic hypertension is associated with regionally specific changes in expression of three key proteins involved in blood pressure control. These data suggest that broad spectrum inhibition or stimulation of these systems may not be the best approach for hypertension treatment. Instead regionally targeted manipulation of these systems should be investigated.

Keywords: Hypertension, Ovariectomy, Orchidectomy, Super oxide dismutase, Soluble epoxide hydrolase, Alpha 2 adrenergic receptor

Introduction

Hypertension is a disease that afflicts approximately 30% of the population of industrialized nations. While the exact mechanisms underlying the majority of hypertension cases remain unknown, it is clear that the development is sexually dimorphic in both animals and humans. In humans, women exhibit a less severe course of hypertension than men, at least until the time of menopause [1]. Sex differences in hypertension are also clearly observed in a number of animal models [1, 2]. High blood pressure develops more rapidly and becomes more severe in males than in females in genetic and experimental models of hypertension [1, 3–5]. The relative contribution of androgens and estrogens remains controversial [3, 5]. As reviewed by Dubey, some studies have suggested that estrogens exert a protective effect against hypertension development [3]. For example in the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) [2, 6] and Dahl salt sensitive rat [7] estrogen appeared to attenuate hypertension. In contrast, orchidectomy of male SHR was effective at attenuating blood pressure elevation early in the hypertensive process [8–12] while testosterone supplementation augmented hypertension [10, 13] suggesting that androgens potentiate hypertension development.

Hypertension is known to be associated with disruptions in the regulation of a number of neurohumoral systems such as the sympathetic nervous system, calcium channels, and renin angiotensin systems which are targets for current antihypertensive therapies. Nevertheless, other less well-studied vascular or renal control mechanisms may play an important role in hypertension and sex differences in this disease. This study chose to focus on less well-studied systems implicated in hypertension: the alpha 2 adrenergic system, the soluble epoxide hydrolase system and the superoxide dismutase system. Alpha 2 adrenergic receptors have a recognized role in the control of arterial pressure by virtue of their ability to inhibit sympathetic outflow via effects in the central nervous system and at presynaptic locations in peripheral sympathetic nerves [14, 15]. Although, less well established, substantial evidence also suggests that alpha 2 adrenergic receptors in the vasculature and kidney are also tied to hypertension development [16]. In the vasculature, alpha 2 adrenergic receptors mediate constriction through activation of vascular smooth muscle [14, 17, 18] an effect that is amplified in hypertension [19]. Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) is implicated in cardiovascular control by virtue of its ability to degrade epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) that exert vasodilatory effects in a number of vascular beds including the mesentery [20] and kidney [21]. EETs also act on the kidney to promote sodium excretion [22]. Consequently, sEH is a prohypertensive factor. Indeed, sEH protein expression and activity were increased in SHR [23] while deletion or inhibition of sEH attenuated hypertension [24, 25]. Hypertension is associated with increased oxidative stress. As one of the enzyme systems responsible for oxygen radicals, superoxide dismutase (SOD) may play a role in hypertension. SOD1 (Cu Zn SOD) was reduced in human hypertensives [26]. Similar findings were reported for the kidney of SHR [27, 28]. Moreover, the use of SOD mimetics dilated isolated mesenteric arteries [29] and reduced hypertension in SHR [30]. Collectively, these data support the view that SOD1, sEH, and alpha 2 adrenergic receptors in both the vasculature and in the kidney are implicated in either the development and/or maintenance of hypertension.

However, the effect gender on these systems has received comparatively less attention. Gong reported that alpha 2 binding sites in kidney homogenates were higher in male SHR compared to female SHR [31]. Conversely, testosterone appeared to downregulate expression of Alpha 2A receptors in the kidney of Sabra hypertensive rats [32]. Alpha 2A receptor density was increased in platelets of postmenopausal women an effect reversed by estrogen treatment [33]. sEH expression was increased in male compared to female murine kidney samples [24, 34]. This sex difference was regionally selective since comparable increases were not observed in liver [34]. Sex differences in the role of sEH in blood pressure control were also evident since male sEH null mice exhibited a reduction in blood pressure whereas female mice did not [24]. Kidney cortex SOD1 but not SOD2 expression was reported to be higher in males than female rats [35]. In contrast, other data suggest no differences in renal medullary SOD1 or SOD2 expression between male and female SHR [36]. While relatively sparse, collectively these data are consistent with the possibility that sexually dimorphic expression of these systems may occur in regionally selective manner. This study tested the hypothesis that endogenous gonadal hormones exert differential effects on protein expression in the kidney and mesenteric artery of male and female SHR subjected to sham operation or gonadectomy.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male and female spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) were purchased at 3 weeks of age from Harlan Sprague–Dawley. The animals were maintained at the University of South Dakota on a 12 h day/night cycle and allowed free access to low phytoestrogen laboratory rat chow (Harlan) and tap water. The institutional animal care and use committee of the University of South Dakota reviewed and approved all procedures involving these animals.

At the age of ~5 weeks, the rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and subjected to sham operation, bilateral ovariectomy, or bilateral orchidectomy. Subsequently at the ages of 20–23 weeks, the rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and cannulae were implanted into the carotid artery. All catheters were filled with heparinized saline (25 mU/ml) and exteriorized to the nape of the neck. The rats were allowed to recover for at least 48–72 h (during which time they were acclimatized to the recording environment) before recording of blood pressure and heart rate. Blood pressure and heart rate were recorded from conscious unrestrained rats in their home cages. After an acclimatization period of approximately 60 min, blood pressure was recorded over a period of 3–4 h at times when the animals were calm. Reported blood pressure values represent the average values over this time period. After the completion of blood pressure recording, the animals were euthanized with pentobarbital. The kidneys and mesenteric vascular tree were rapidly collected via a midline laparotomy.

Western blot analysis

The mesenteric vascular tree was placed in ice cold homogenization buffer and the mesenteric artery dissected free of its associated vein and fat tissue while a section of kidney corresponding to the cortex was collected into ice cold homogenization buffer. These mesenteric artery and kidney tissue samples were dispersed by repeated sonication in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.25 M sucrose, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF, and 100 μM leupeptin [37]. The protein content of the samples was determined using the BioRad protein assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). One-dimensional Western blots were run using standard techniques. A sample of protein solution containing a standard amount of protein (50 μg) was mixed with 5 volumes of SDS sample buffer (Tris 250 mM, SDS 5%, glycerol 10%, bromophenol blue 0.006%, ß-mercaptoethanol 2%) and placed in a boiling water bath for 5 min. The samples were loaded into wells of the assay gel and subjected to SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad). After transfer of proteins from the gel to PVDF membranes, the membranes were blocked in 1:1 Aqua Block blocking buffer (East Coast Biologics, Inc., North Berwick, ME) overnight. The membranes were then incubated at 4C overnight with primary antibody against the protein of interest diluted in Aqua Block. After washing, the membranes were then incubated with actin primary antibody at 4C overnight (SOD1: BD Biosciences 1:500; sEH Santa Cruz 1:1000; A2AR Affinity Bioreagents 1:500; Actin Calbiochem 1:2000). After washing, the membranes were incubated with a fluorescent-labeled secondary antibody diluted in Aqua Block for 3 h. The membranes were imaged with the Odyssey Infrared Imager (LiCor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). The protein bands were quantified with the densitometric analysis software on the Odyssey Imager, and the density of the protein of interest was expressed as a percentage of actin loading control density.

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Absolute values for MAP and densitometry values were analyzed by two way analysis of variance (grouping factors: sex and surgery). Fisher’s Protected Least Significant difference was used as the post hoc test. Differences were considered significant at a probability of 5% or less (P < 0.05). Statistical differences between groups are indicated by letters. Histograms with the same letter are not different statistically while histograms denoted by different letters are statistically different.

Results

Baseline body weight and blood pressure

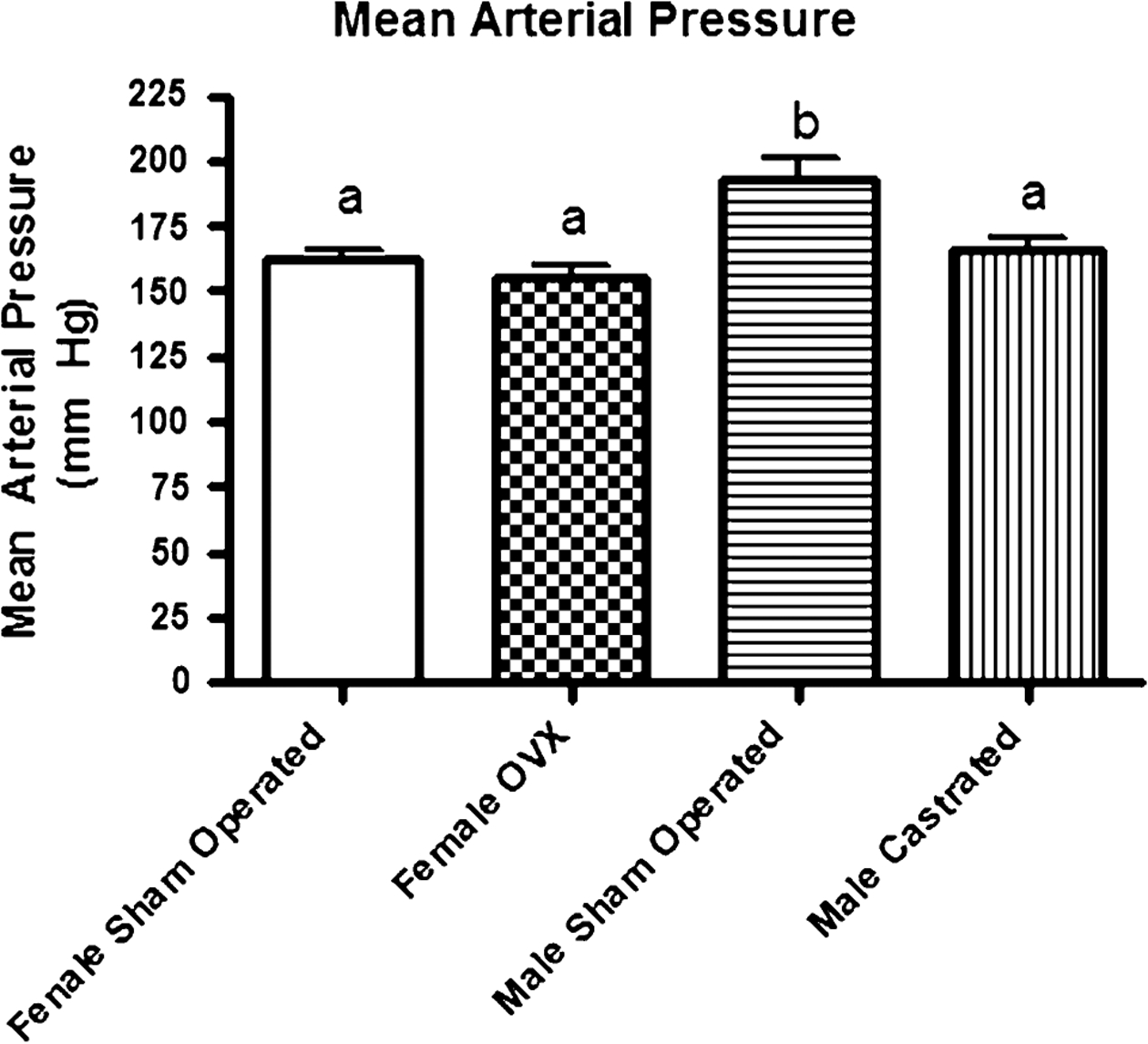

Body weight was significantly greater in the OVX SHR (251 ± 16 g) compared to sham-operated SHR (196 ± 11 g). Conversely, gonadectomy in males caused body weight to decrease (Sham-Operated Males 371 ± 15 g: Castrated Males 298 ± 7 g). Baseline mean arterial pressure (MAP) is shown in Fig. 1. MAP was higher in male sham-operated SHR (193 ± 8 mm Hg) compared to the male-castrated SHR (165 ± 6 mm Hg), female sham-operated SHR (162 ± 4 mm Hg), and female OVX SHR (156 ± 4 mm Hg). There were no significant differences in MAP between sham-operated and OVX female SHR. Similarly, MAP in castrated male SHR was not significantly different than that observed in either the sham-operated female SHR or the OVX SHR. Thus, castration of male SHR abolished the observed sex difference in MAP. There were no significant differences in baseline HR among any of the groups.

Fig. 1.

Absolute values for baseline mean arterial pressure (MAP) obtained at 20–23 weeks of age in male and female SHR subjected to sham operation or gonadectomy at ~5 weeks of age. Male Sham Operated (N = 6) (Sham), Male Castrated (N = 6) (Cam), Female Sham Operated (N = 6) (Sham), and Female Ovariectomized = Female OVX (N = 6) (OVX). ANOVA: Gender P < 0.0001, Surgery P = 0.0005, Interaction P = 0.03). Statistical differences (P < 0.05) between groups are indicated by letters. Histograms with the same letter are not statistically different while histograms denoted by different letters are statistically different

Cu Zn super oxide dismutase protein expression (SOD1)

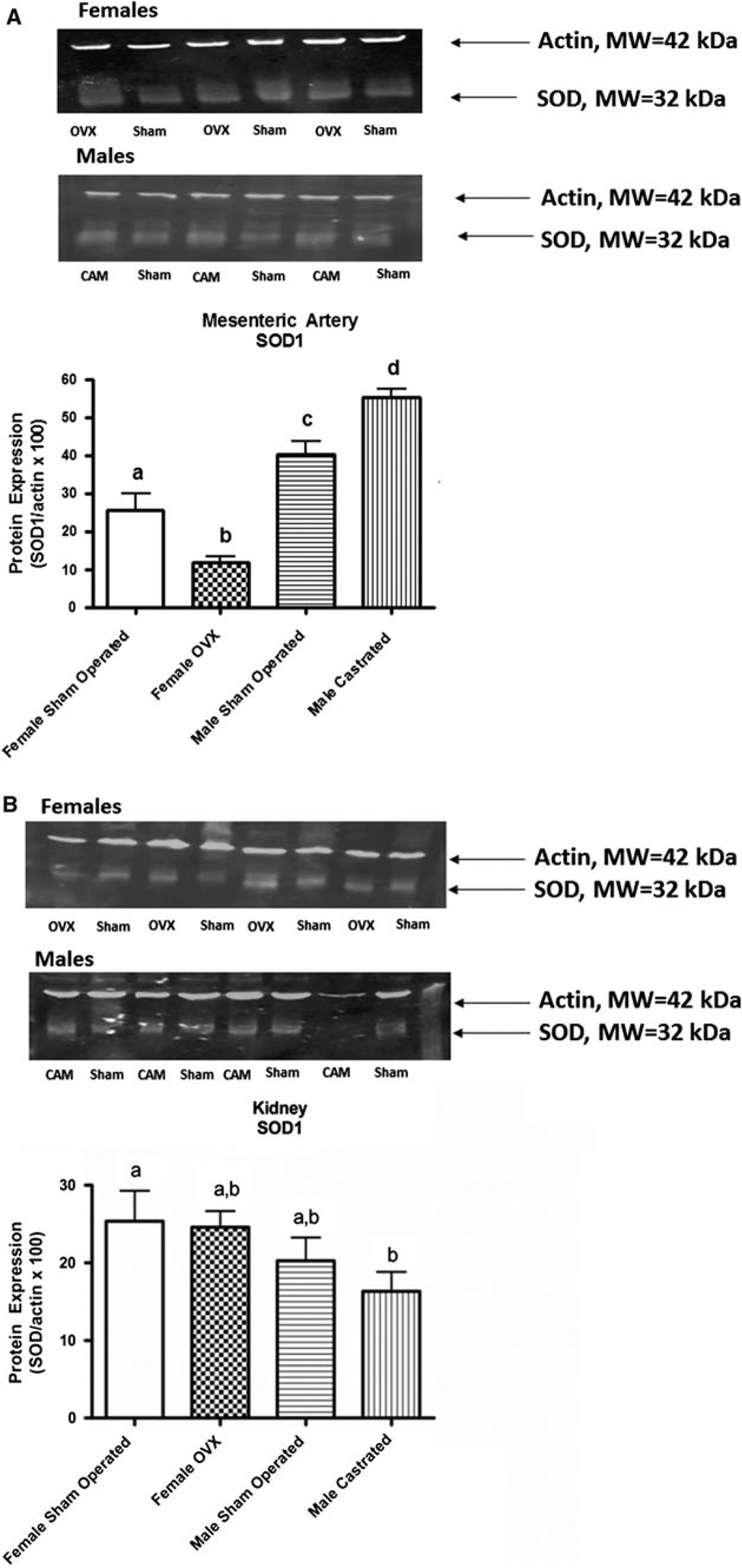

The SOD1 signal as assessed by Western blot was relatively weak compared to that of the actin loading control (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, in mesenteric artery homogenates differences in SOD1 expression were detected (Gender P < 0.0001, Interaction P = 0.007) among the treatment groups. Overall SOD1 expression was higher in male compared to female SHR. Within each gender, gonadectomy had an effect on SOD1 expression although this effect was different in females and males. SOD1 was decreased in female-ovariectomized SHR compared to sham-operated females. Conversely, castration of male SHR increased SOD1 expression. Sexually dimorphic SOD1 signal was also detected in kidney homogenates where a main effect of gender was apparent (P = 0.04). Within the female group, SOD1 expression was not different between sham-operated and OVX female SHR. SOD1 expression was generally lower in male than in female SHR. Castration of male SHR resulted in a level of SOD1 expression that was significantly lower than that observed in female SHR but not different from the value observed in sham-operated male SHR.

Fig. 2.

Western blot assessment of Cu Zn SOD (SOD1) expression in homogenates of mesenteric artery obtained at 20–23 weeks of age (a) from Male Sham Operated (N = 6) (Sham), Male Castrated (N = 6) (Cam), Female Sham Operated (N = 6) (Sham), and Female Ovariectomized = Female OVX (N = 6) (OVX). ANOVA: Gender P < 0.0001, Surgery P = 0.89, Interaction P = 0.007) and kidney obtained at 20–23 weeks of age (b) from Male Sham Operated (N = 4) (Sham), Male Castrated (N = 4) (Cam), Female Sham Operated (N = 4) (Sham), Female OVX = Female Ovariectomized (N = 4) (OVX). ANOVA: Gender P = 0.04, Surgery P = 0.44, Interaction P = 0.61). Statistical differences (P < 0.05) between groups are indicated by letters. Histograms with the same letter are not statistically different while histograms denoted by different letters are statistically different Surgical procedures were performed in SHR at ~5 weeks of age. Actin MW ~42 kDa, SOD1 MW ~32 kDa

Soluble epoxide hydrolase protein expression (sEH)

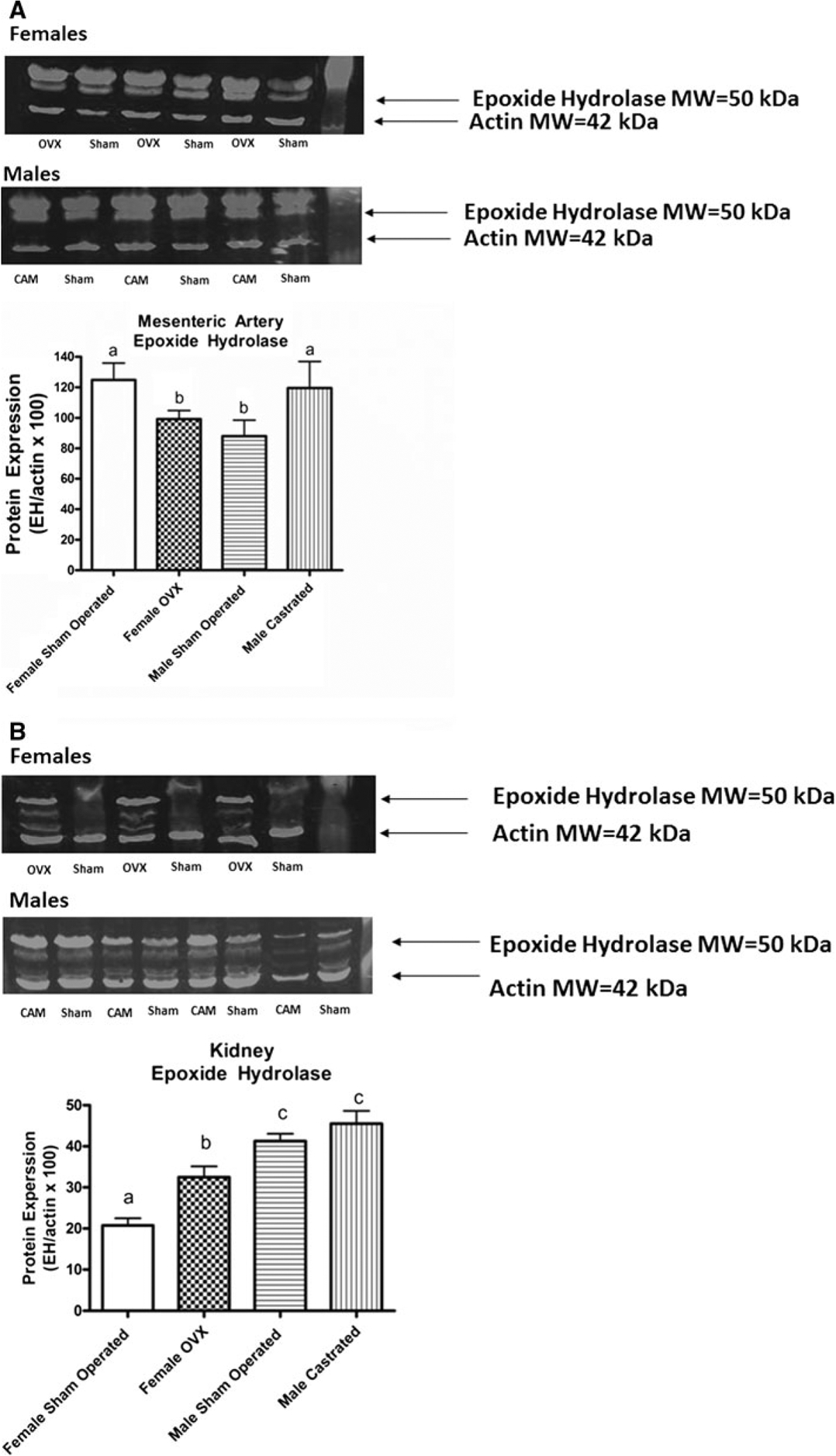

sEH signal was relatively robust in mesenteric artery homogenates (Fig. 3). ANOVA detected a significant interaction (P = 0.03) between the grouping factors of gender and surgery. sEH expression was significantly reduced in the OVX females compared to the sham-operated female SHR. Conversely, castration of male SHR increased sEH expression significantly. In the kidney homogenates, the sEH signal was not as robust as that observed in mesenteric artery samples. Nevertheless, significant main effects for gender (P < 0.0001) and surgery (P = 0.005) were detected by ANOVA. There was a clear sex difference with male SHR exhibiting higher expression than female SHR. Within the male cohort, castration had no effect on sEH expression compared to sham-operated SHR, suggesting that testosterone is not responsible for this sex difference. In the female cohort, sEH expression was increased significantly in female OVX SHR compared to sham-operated SHR, suggesting that endogenous female sex steroids suppress sEH expression in the kidney.

Fig. 3.

Western blot assessment of soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) expression in homogenates of mesenteric artery obtained at 20–23 weeks of age (a) from Male Sham Operated (N = 6) (Sham), Male Castrated (N = 6) (Cam), Female Sham Operated (N = 6) (Sham), and Female Ovariectomized = Female OVX (N = 6) (OVX). ANOVA: Gender P < 0.67, Surgery P = 0.61, Interaction P = 0.03) and kidney (b) Male Sham Operated (N = 4) (Sham), Male Castrated (N = 4) (Cam), Female Sham Operated (N = 4) (Sham) and Female Ovariectomized = Female OVX (N = 4) (OVX). ANOVA: Gender P < 0.0001, Surgery P = 0.005, Interaction P = 0.14). Statistical differences (P < 0.05) between groups are indicated by letters. Histograms with the same letter are not statistically different while histograms denoted by different letters are statistically different. Surgical procedures were performed in SHR at ~5 weeks of age. Actin MW ~42 kDa, sEH MW ~50 kDa

Alpha 2A adrenergic receptor (A2AR) expression

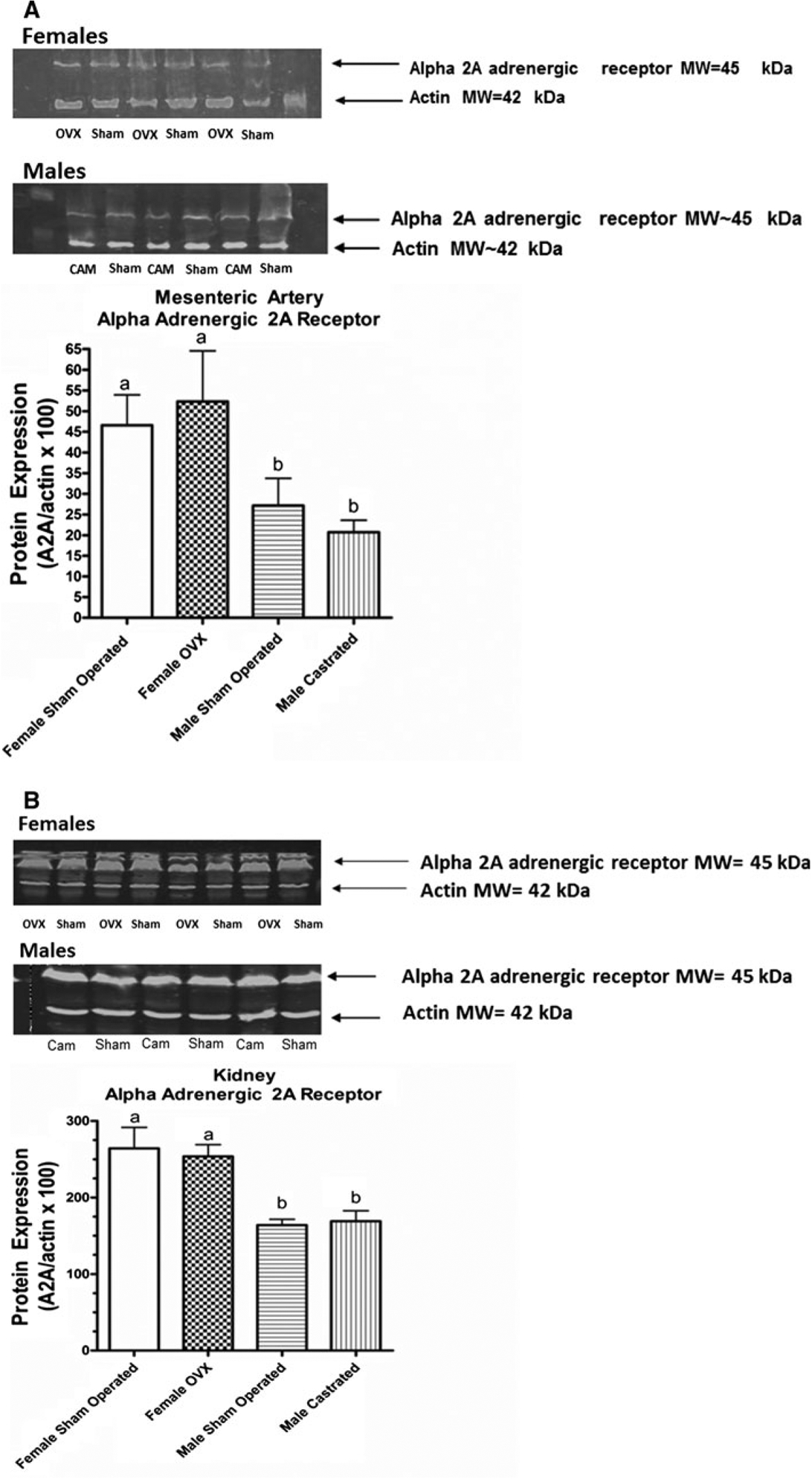

ANOVA revealed significant effects of gender (P = 0.005) for A2AR expression in mesenteric artery homogenates (Fig. 4). Post hoc analysis showed that A2AR expression was greater in the female groups compared to the male groups. Within the same sex cohorts, castration did not affect A2AR expression significantly. A similar pattern of A2AR expression was observed in the kidney where ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of gender (P = 0.0002). Samples obtained from female SHR showed greater expression than those obtained from male SHR. However, there were no significant differences in A2AR expression between sham-operated and OVX female SHR. Similarly, A2AR protein expression was not different between sham-operated and castrated male SHR.

Fig. 4.

Western blot assessment of Alpha 2A adrenergic receptor expression in homogenates of mesenteric artery obtained at 20–23 weeks of age (a) from Male Sham Operated (N = 6) (Sham), Male Castrated (N = 6) (Cam), Female Sham Operated (N = 6) (Sham), and Female Ovariectomized = Female OVX (N = 6) (OVX). ANOVA: Gender P = 0.005, Surgery P = 0.97, Interaction P = 0.45) and kidney (b) Male Sham Operated (N = 4) (Sham), Male Castrated (N = 4) (Cam), Female Sham Operated (N = 4) (Sham) and Female Ovariectomized = Female OVX (N = 4) (OVX). ANOVA: Gender P < 0.0002, Surgery P = 0.089, Interaction P = 0.67). Statistical differences (P < 0.05) between groups are indicated by letters. Histograms with the same letter are not statistically different while histograms denoted by different letters are statistically different. Surgical procedures were performed in SHR at ~5 weeks of age. Actin MW ~42 kDa, A2A MW ~45 kDa

Discussion

Convincing evidence exists that hypertension is sexually dimorphic in animal models and human subjects, with females exhibiting less severe hypertension than males, at least until the time of menopause. While these data are clear, the mechanisms underlying the sex differences in hypertension remain to be defined. Sex steroids may account for some of these differences, since manipulating endogenous sex steroids through orchidectomy or ovariectomy alters the course of hypertension. Since, the sex steroids are ligand-activated transcription factors that exert their long-term effects at least in part through changes in gene and protein expression, it seems likely that changes in protein expression contribute to sex differences in hypertension development. Given that sex steroids may exert regionally distinct effects, this study tested the hypothesis that endogenous gonadal hormones exert differential effects on protein expression in the kidney and mesentery of male and female SHR subjected to sham operation or gonadectomy.

In this study, arterial blood pressure was measured at approximately 23 weeks of age which corresponds to the maintenance stage of hypertension in the SHR. We observed that sham-operated male SHR exhibited higher blood pressure than female sham-operated SHR, consistent with a sex difference in hypertension development in this genetic model. Castration of male SHR at an early age (5 weeks) led to a reduction in the level of hypertension measured during the established phase of the disease. This finding supports previous data from our laboratory [9, 11, 38] and those of others [8, 36, 39, 40] suggesting that removal of endogenous androgens attenuated hypertension development in male SHR. Indeed, blood pressure in the castrated male SHR was not significantly different than that recorded in the sham-operated female SHR, suggesting that endogenous male sex steroids play a key role in sex differences in blood pressure in the SHR. We have made similar observations in another genetic model of hypertension, the New Zealand genetically hypertensive rat [10, 41, 42] consistent with the view that the effect of male sex steroids to amplify genetic hypertension is a generalized phenomenon. On the other hand, we observed that the blood pressure of ovariectomized female SHR was not different from that recorded in sham-operated female SHR. Thus, removal of endogenous female sex steroids did not affect the development of hypertension. These data are consistent with our previous findings [38, 43, 44] and those others [45–47]. In contrast, other groups have reported that ovariectomy enhanced hypertension development in SHR [2, 48, 49]. The reasons for these discrepant findings are not immediately clear, however, it may be related to the degree of salt sensitivity of the SHR strain used or the degree of sodium in the diet [47].

SOD1 has been implicated in the development of hypertension by virtue of its ability to scavenge superoxide. SOD1 expression was reduced in erythrocytes from human hypertensive subjects [26] as well as in the kidney of SHR [27, 28]. Currently, data concerning the effects of sex on SOD1 in the vasculature are sparse and contradictory. SOD1 expression was reduced in brain homogenates of female compared to male adult mice [50]. SOD1 expression was not different in cerebral vessels harvested from male and female Sprague–Dawley rats [51] or mice [52]. In this study, we observed that SOD1 expression in mesenteric artery homogenates was higher in male compared to female SHR. These different outcomes may be due to strain (SHR vs. Sprague–Dawley rats/mice) or tissue (cerebral vs. mesentery) differences. SOD1 expression was reduced by OVX in whole brain homogenates obtained from mice [50]. In line with this report, we found that OVX was associated with a reduction in SOD1 expression in mesenteric artery homogenates. The reduction in SOD1 expression is consistent with the reported reduction in superoxide scavenging in OVX animals [53]. In contrast to the findings in female SHR, we found that castration of male SHR was associated with an increase in SOD1 expression in mesenteric artery samples supporting a previous report of the effects of castration on SOD1 expression [54]. An increase in SOD1 expression may account for the reported increase in SOD1 activity in aorta obtained from orchidectomized rats [54]. The effects of gender and gonadectomy on SOD1 expression appear to be regionally selective in that the kidney showed a different pattern of response. In the kidney, ANOVA detect a significant main effect of sex with overall SOD1 expression higher in female compared to male SHR. In contrast, it has been previously reported that kidney cortex SOD1 expression was higher in males than female rats [35] or that there was no difference in renal SOD1 expression between male and female SHR [36]. The reasons for these divergent findings are not immediately clear. However, our study was performed on SHR of ~20–23 weeks of age while the findings of previous study were obtained from SHR of 15 weeks of age and 12–14 weeks of age, respectively. SOD1 expression was reduced in kidney homogenates obtained from orchidectomized SHR. A similar trend was previously reported [36], although in that study the differences were not statistically significant. The correlations described in this study do not directly answer the cause and effect relationship between SOD1 expression and hypertension. Nevertheless, given that the changes in SOD1 that we observed are, in general, inversely related to blood pressure (e.g., SOD1 increased in male versus female), it seems unlikely that changes in SOD1 expression are a primary cause of hypertension. Expression of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD1 is thought to be upregulated by oxidative stress [36, 55, 56]. Accordingly, it seems more reasonable to suggest that changes in SOD1 are part of a negative feedback loop designed to compensate for the increased oxidant status known to exist in hypertensive animals [36, 55]. These responses may be impaired in SHR [36, 55] allowing ROS to exert pro hypertensive effects. Ultimately, large-scale studies using conditional knock out or silencing of SOD1 using site specific promoters during the developmental and maintenance stages of hypertension will be required to definitely address this issue.

sEH is another enzyme linked to hypertension by way of its ability to degrade epoxyeicosatrienoic acids that may exert vasodilator and anti-hypertensive effects. In mesenteric artery samples, ANOVA did not detect a main effect of gender. In contrast, increased sEH expression was reported in the brain of female compared to male mice [57], whereas there was no effect of gender on sEH gene expression in humans [58]. In our hands, there was a small albeit statistically significant decrease in sEH expression following ovariectomy. The effects of estrogen and its analogs on sEH expression are complex. We previously reported that while estradiol benzoate did not affect sEH expression, ethinyl estradiol increased sEH expression [59]. Thus, loss of estrogen or one of its metabolites may account for the reduction in sEH expression in the ovariectomized SHR. These changes in sEH expression are difficult to reconcile with a direct effect on blood pressure. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids are recognized vasodilators of the mesenteric vasculature [20, 60]. sEH degrades vasodilator epoxyeicosatrienoic acids to less active intermediates [61], thus loss of sEH expression might have been expected to increase EET concentrations, to reduce vascular resistance [62] and lower blood pressure in female-ovariectomized SHR. However, we observed no differences in blood pressure between the sham-operated and ovariectomized SHR. This finding is consistent with that reported for female sEH null mice which did not exhibit a decrease in blood pressure [24]. Conversely, loss of endogenous androgens via orchidectomy was associated with increased sEH expression whereas blood pressure was lowered in castrated male SHR. These observations are compatible with two possibilities. First, changes in sEH expression in the mesenteric vasculature may have relatively little influence on blood pressure. This possibility seems unlikely as studies using pharmacological inhibitors of sEH have demonstrated decreases in blood pressure [63]. Alternatively, castration may have lowered blood pressure in male SHR via effects on systems other than vascular sEH and sEH expression was increased as a counter regulatory measure. The kidney exhibited a somewhat different pattern of sEH expression. A sex difference was apparent as sEH protein expression was higher in kidney homogenates obtained from male SHR compared to female SHR. These data are consistent with previous reports showing that renal sEH expression is higher in male compared to female mice [24, 34]. Since, increased expression of sEH would be expected to more readily degrade EETs which exert antihypertensive and renoprotective effects in the kidney, our findings are consistent with the increased blood pressure in male versus female SHR [5, 36]. Orchidectomy did not affect renal sEH expression significantly, suggesting that the differences between male and female sEH expression were not due to endogenous androgens. On the other hand, ovariectomy resulted in a significant increase in sEH expression in the kidney, implicating endogenous estrogens in the control of renal sEH expression. However, this increase in sEH expression was not accompanied by a marked change in blood pressure. Thus, the differential changes in sEH expression in the male and female kidney and mesenteric artery samples are interesting but difficult to interpret mechanistically in terms of blood pressure control. In addition, the band patterns of the sham-operated female and OVX SHR samples seemed different, suggesting the possibility of estrogen sensitive polymorphisms in epoxide hydrolase gene expression. While, we cannot address this possibility directly with our data, polymorphisms in epoxide hydrolase gene expression linked to proteinuria in a gender selective manner were reported in the stroke prone strain of SHR [64, 65]. Accordingly, the increase in sEH expression observed in OVX SHR is consistent with the increased macrophage infiltration and albuminuria observed in OVX SHR [36] suggesting a possible role for estrogen sensitive changes in sEH expression in hypertensive end organ renal damage. In any case, the differential pattern of sEH protein expression in mesentery and kidney samples observed in this study is consistent with previous study showing that sex and testosterone had different effects on sEH activity in the liver and kidney [34]. These regionally specific changes in sEH expression make use of broad scale approaches such as global drug treatments or knockouts impractical. Ultimately, large-scale studies using conditional knock out or silencing of sEH using tissue specific promoters during manipulation of sex steroids in the developmental and maintenance stages of hypertension will be required to directly address this issue.

Presynaptic alpha 2A receptors are recognized to play a major role in the control of blood pressure by virtue of their ability to regulate sympathetic outflow to the cardiovascular system via actions in hindbrain cardiovascular control centers and peripheral sympathetic nerve terminals [14, 15]. More controversial and less well studied are the actions of the alpha 2A receptors in the vasculature and kidney. Postsynaptic alpha 2 adrenergic receptors that mediate vasoconstriction are distributed throughout the arterial vascular tree [18] including in the mesenteric artery [66]. Moreover, responses to manipulation of these receptors are exaggerated in SHR [67], in rats made hypertensive by nitric oxide synthase inhibition [17], and in human hypertensive patients [68]. These data implicate vascular alpha 2 adrenergic receptors in hypertension. While, there has been considerable investigation of sexual dimorphism in alpha 1 adrenergic control of vascular smooth muscle, study of sex differences in expression and function of alpha 2 adrenergic receptors is sparse. In view of its reported vasoconstrictor actions [16], we had predicted that mesenteric artery alpha 2A receptor expression would be increased in male compared to female SHR. In contrast to our prediction, while we observed a gender difference in alpha 2A adrenergic receptor expression in mesenteric arteries, female SHR exhibited greater alpha 2A adrenergic receptor expression compared to male SHR. In contrast, it was reported that alpha 2A mRNA expression in rat tail artery was not different between male and female rats [69]. On the other hand, Tejera reported that alpha 2 adrenergic constrictions of aortic rings was greater in female compared to male rats [70], which is functionally consistent with our observation of increased alpha 2 receptor expression in mesenteric vascular smooth muscle in females. However, these findings do not support a primary role for mesenteric arterial vascular smooth alpha 2A receptors in the hypertensive phenotype of the SHR since blood pressure was lower in female SHR than male SHR despite elevated mesenteric alpha 2A receptor expression. Since, sympathetic nerve terminals are embedded in the vessel wall, we cannot rule out the possibility that the increases alpha 2A receptor expression may reflect changes in density of presynaptic alpha 2A receptors on sympathetic neurons. These receptors in turn could inhibit sympathetic transmitter release [14] and lead to a reduction in blood pressure consistent with the observed lower blood pressure in female SHR. We found that gonadectomy did not affect alpha 2A receptor expression in either female or male SHR. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first direct examination of the effects of gonadectomy on alpha 2A receptor expression in vascular tissue. Functional studies regarding the effect of gonadectomy on alpha 2A receptor responses are contradictory. Alpha 2 adrenergic responses were reported to be increased in carotid artery of ovariectomized rats [71], which is consistent with the report that estrogen treatment of ovariectomized rabbits decreased alpha 2-mediated contractile effects in the femoral artery [72]. Conversely, ovariectomy was reported to decrease alpha 2-mediated responses in aortic rings [70] and isolated mesenteric artery [73] preparations. On the other hand, neither orchidectomy nor ovariectomy affected alpha 2 adrenergic receptor-mediated responses in the rat tail artery [74]. Thus, there remains considerable controversy regarding the effects of gonadectomy on alpha 2-mediated responses in vascular smooth muscle. These disparate findings may be due to different species or vascular beds used and thus underscore the regional heterogeneity of response to endogenous sex steroids. In any case, the data from this study suggests that the observed gender difference in mesenteric alpha 2A receptor expression is not dependent on the presence of sex steroids and likely does not contribute directly to hypertension in the SHR.

Alpha 2A receptors in the kidney have also been implicated in hypertension [31, 75–77]. In SHR and Dahl hypertensive rats renal alpha 2 receptor density, as assessed by radioligand binding studies, was greater in males than females [31, 78]. In contrast, we observed that renal alpha 2A receptor expression was decreased in male compared to female SHR. However, previous studies have examined either overall alpha 2 receptor density or have focused on the alpha 2B subtype. Moreover, the alpha 2B and alpha 2A adrenergic receptors may be differentially regulated by sex steroids in the kidney [17, 76, 77]. Indeed, in Sabra hypertensive rats, alpha 2A receptor expression is increased following orchidectomy whereas the alpha 2B subtype was decreased [76, 77]. In any case, these data suggest that there is a clear sex difference in the expression of alpha 2 adrenergic receptors in the kidney. In our hands, this difference does not appear to be related to the presence of endogenous sex steroids since neither ovariectomy nor orchidectomy altered alpha 2A receptor expression in the kidney. Renal alpha 2A receptors appear to exert antihypertensive effects via increased sodium excretion and urine flow [76, 79]. Accordingly, the lower expression alpha 2A receptor expression in male compared to female SHR observed in this study may have contributed to the higher pressure in male SHR.

The findings of this study support the view that hypertension in the SHR is sexually dimorphic. There are also sex-dependent differences in the expression of SOD1, sEH, and alpha 2A receptors in the mesenteric artery and kidney, suggesting that sex and endogenous sex steroids may exert regionally selective effects on these systems. A limitation to this study is that gonadectomy was performed early (~5 weeks of age) to avoid the pubertal surge in endogenous sex steroids that may have long-term effects on blood pressure [8]. Unavoidably early gonadectomy also affected development, at least as judged by body weight. Accordingly, we cannot rule out the possibility that changes in development contributed to some of the blood pressure and protein expression responses that we observed. Nevertheless, the reported regionally specific alterations in protein expression suggest that broad spectrum manipulation of these systems may not be the most appropriate approach to study or treatment. Rather, future study should investigate regionally targeted manipulations of these systems to define their roles in the maintenance of hypertension.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH HLBI 63053.

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Reckelhoff JF (2001) Gender differences in the regulation of blood pressure. Hypertension 37:1199–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iams SG, Wexler BC (1979) Inhibition of the development of spontaneous hypertension in SH rats by gonadectomy or estradiol. J Lab Clin Med 94:608–616 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubey RK, Oparil S, Imthurn B, Jackson EK (2002) Sex hormones and hypertension. Cardiovasc Res 53:688–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalil RA (2005) Sex hormones as potential modulators of vascular function in hypertension. Hypertension 46(2):249–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reckelhoff JF (2008) Sex and sex steroids in cardiovascular-renal physiology and pathophysiology. Gend Med 5(Suppl A):S1–S2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang Z, Carlson SH, Chen YF, Oparil S, Wyss JM (2001) Estrogen depletion induces NaCl sensitive hypertension in female spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol 281:R1934–R1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinojosa Laborde C, Craig T, Zheng W, Ji H, Haywood JR, Sandberg K (2004) Ovariectomy augments hypertension in aging female Dahl salt sensitive rats. Hypertension 44:405–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganten U, Witt GS, Zimmermann F, Ganten D, Stock G (1989) Sexual dimorphism of blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats: effect of antiandrogen treatment. J Hypertens 7:721–726 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin D, Biltoft S, Redetzke R, Vogel E (2005) Castration reduces blood pressure and autonomic venous tone in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 23:2229–2236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song J, Eyster KM, Kost CK Jr, Kjellsen B, Martin DS (2010) Involvement of protein kinase C-CPI-17 in androgen modulation of angiotensin II-renal vasoconstriction. Cardiovasc Res 85(3):614–621. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song J, Martin DS (2006) Rho kinase contributes to androgen amplification of renal vasoconstrictor responses in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 48(3):103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reckelhoff JF, Zhang J, Granger JP (1998) Testosterone exacerbates hypertension and reduces pressure natriuresis in male spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 31:435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reckelhoff JF, Yanes LL, Iliescu R, Fortepiani LA, Granger JP (2005) Testosterone supplementation in aging men and women: possible impact on cardiovascular-renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289(5):F941–F948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanagy NL (2005) Alpha(2)-adrenergic receptor signalling in hypertension. Clin Sci (Lond) 109(5):431–437. doi: 10.1042/CS20050101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vongpatanasin W, Kario K, Atlas SA, Victor RG (2011) Central sympatholytic drugs. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 13(9):658–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00509.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JY, DeBernardis JF (1990) Alpha 2-adrenergic receptors and calcium: alpha 2-receptor blockade in vascular smooth muscle as an approach to the treatment of hypertension. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 12(3):213–225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanagy NL (1997) Increased vascular responsiveness to alpha 2-adrenergic stimulation during NOS inhibition-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol 273(6 Pt 2):H2756–H2764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Struijker-Boudier HA, Messing MW, van Essen H (1996) Alpha-adrenergic reactivity of the microcirculation in conscious spontaneously hypertensive rats. Mol Cell Biochem 157(1–2): 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter RW, Kanagy NL (2003) Mechanism of enhanced calcium sensitivity and alpha 2-AR vasoreactivity in chronic NOS inhibition hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284(1): H309–H316. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00453.200200453.2002[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proctor KG, Falck JR, Capdevila J (1987) Intestinal vasodilation by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids: arachidonic acid metabolites produced by a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. Circ Res 60(1): 50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imig JD, Navar LG, Roman RJ, Reddy KK, Falck JR (1996) Actions of epoxygenase metabolites on the preglomerular vasculature. J Am Soc Nephrol 7(11):2364–2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nusing RM, Schweer H, Fleming I, Zeldin DC, Wegmann M (2007) Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids affect electrolyte transport in renal tubular epithelial cells: dependence on cyclooxygenase and cell polarity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293(1):F288–F298. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00171.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Z, Xu F, Huse LM, Morisseau C, Draper AJ, Newman JW, Parker C, Graham L, Engler MM, Hammock BD, Zeldin DC, Kroetz DL (2000) Soluble epoxide hydrolase regulates hydrolysis of vasoactive epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Circ Res 87(11):992–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinal CJ, Miyata M, Tohkin M, Nagata K, Bend JR, Gonzalez FJ (2000) Targeted disruption of soluble epoxide hydrolase reveals a role in blood pressure regulation. J Biol Chem 275(51):40504–40510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008106200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghosh S, Chiang PC, Wahlstrom JL, Fujiwara H, Selbo JG, Roberds SL (2008) Oral delivery of 1,3-dicyclohexylurea nanosuspension enhances exposure and lowers blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 102(5):453–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amirkhizi F, Siassi F, Djalali M, Foroushani AR (2010) Assessment of antioxidant enzyme activities in erythrocytes of pre-hypertensive and hypertensive women. J Res Med Sci 15(5): 270–278 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simao S, Gomes P, Pinto V, Silva E, Amaral JS, Igreja B, Afonso J, Serrao MP, Pinho MJ, Soares-da-Silva P (2011) Age-related changes in renal expression of oxidant and antioxidant enzymes and oxidative stress markers in male SHR and WKY rats. Exp Gerontol 46(6):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhan CD, Sindhu RK, Pang J, Ehdaie A, Vaziri ND (2004) Superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in the spontaneously hypertensive rat kidney: effect of antioxidant-rich diet. J Hypertens 22(10):2025–2033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Pearlman A, Luo Z, Wilcox CS (2007) Hydrogen peroxide mediates a transient vasorelaxation with tempol during oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293(4):H2085–H2092. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00968.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Patel K, Connors SG, Mendonca M, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS (2007) Acute antihypertensive action of Tempol in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293(6):H3246–H3253. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00957.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gong G, Dobin A, McArdle S, Sun L, Johnson ML, Pettinger WA (1994) Sex influence on renal alpha 2-adrenergic receptor density in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 23(5):607–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khalid M, Ilhami N, Giudicelli Y, Dausse JP (2002) Testosterone dependence of salt induced hypertension in Sabra rats and role of renal alpha 2 adrenoreceptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exptl Ther 300:43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piletz JE, Halbreich U (2000) Imidazoline and alpha(2a)-adrenoceptor binding sites in postmenopausal women before and after estrogen replacement therapy. Biol Psychiatry 48(9):932–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinot F, Grant DF, Spearow JL, Parker AG, Hammock BD (1995) Differential regulation of soluble epoxide hydrolase by clofibrate and sexual hormones in the liver and kidneys of mice. Biochem Pharmacol 50(4):501–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sartori-Valinotti JC, Iliescu R, Fortepiani LA, Yanes LL, Reckelhoff JF (2007) Sex differences in oxidative stress and the impact on blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34(9):938–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan JC, Sasser JM, Pollock JS (2007) Sexual dimorphism in oxidant status in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292(2):R764–R768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eyster KM, Waller MS, Miller TL, Miller CJ, Johnson MJ, Persing JS (1993) The endogenous inhibitor of protein kinase-C in the rat ovary is a protein phosphatase. Endocrinology 133(3):1266–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tatchum-Talom R, Eyster KM, Kost CK Jr, Martin DS (2011) Blood pressure and mesenteric vascular reactivity in spontaneously hypertensive rats 7 months after gonadectomy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 57(3):357–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reckelhoff JF, Granger JP (1999) Role of androgens in mediating hypertension and renal injury. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 26(2):127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toot J, Jenkins C, Dunphy G, Boehme S, Hart M, Milsted A, Turner M, Ely D (2008) Testosterone influences renal electrolyte excretion in SHR/y and WKY males. BMC Physiol 8:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song J, Kost CK Jr, Martin DS (2006) Androgens potentiate renal vascular responses to angiotensin II via amplification of the Rho kinase signaling pathway. Cardiovasc Res 72(3):456–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song J, Kost CK Jr, Martin DS (2006) Androgens augment renal vascular responses to ANG II in New Zealand genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290(6):R1608–R1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin DS, Breitkopf NP, Eyster KM, Williams JL (2001) Dietary soy exerts an antihypertensive effect in spontaneously hypertensive female rats. Am J Physiol 281:R553–R560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin DS, Redetzke R, Vogel E, Mark C, Eyster KM (2008) Effect of ovariectomy on blood pressure and venous tone in female spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 21(9):983–988. doi:ajh2008237[pii]10.1038/ajh.2008.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fortepiani LA, Zhang H, Racusen L, LJR JFR (2003) Characterization of an animal model of postmenopausal hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 41:640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan JC, Semprun-Prieto L, Boesen EI, Pollock DM, Pollock JS (2007) Sex and sex hormones influence the development of albuminuria and renal macrophage infiltration in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293(4):R1573–R1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrison-Bernard LM, Schulman IH, Raij L (2003) Postovariectomy hypertension is linked to increased renal AT1 receptor and salt sensitivity. Hypertension 42(6):1157–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ito K, Hirooka Y, Kimura Y, Sagara Y, Sunagawa K (2006) Ovariectomy augments hypertension through rho-kinase activation in the brain stem in female spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 48(4):651–657. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000238125.21656.9e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng N, Clark JT, Wei CC, Wyss JM (2003) Estrogen depletion increases blood pressure and hypothalamic norepinephrine in middle-aged spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 41(5):1164–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000065387.09043.2E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ali SS, Xiong C, Lucero J, Behrens MM, Dugan LL, Quick KL (2006) Gender differences in free radical homeostasis during aging: shorter-lived female C57BL6 mice have increased oxidative stress. Aging Cell 5(6):565–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00252.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller AA, Drummond GR, Mast AE, Schmidt HH, Sobey CG (2007) Effect of gender on NADPH-oxidase activity, expression, and function in the cerebral circulation: role of estrogen. Stroke 38(7):2142–2149. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.477406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Silva TM, Broughton BR, Drummond GR, Sobey CG, Miller AA (2009) Gender influences cerebral vascular responses to angiotensin II through Nox2-derived reactive oxygen species. Stroke 40(4):1091–1097. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ha BJ, Lee SH, Kim HJ, Lee JY (2006) The role of Salicornia herbacea in ovariectomy-induced oxidative stress. Biol Pharm Bull 29(7):1305–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blanco-Rivero J, Sagredo A, Balfagon G, Ferrer M (2006) Orchidectomy increases expression and activity of Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase, while decreasing endothelial nitric oxide bioavailability. J Endocrinol 190(3):771–778. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fortepiani LA, Reckelhoff JF (2005) Increasing oxidative stress with molsidomine increases blood pressure in genetically hypertensive rats but not normotensive controls. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289(3):R763–R770. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00526.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mates JM (2000) Effects of antioxidant enzymes in the molecular control of reactive oxygen species toxicology. Toxicology 153(1–3): 83–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang W, Iliff JJ, Campbell CJ, Wang RK, Hurn PD, Alkayed NJ (2009) Role of soluble epoxide hydrolase in the sex-specific vascular response to cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 29(8):1475–1481. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farin FM, Janssen P, Quigley S, Abbott D, Hassett C, Smith-Weller T, Franklin GM, Swanson PD, Longstreth WT Jr, O-miecinski CJ, Checkoway H (2001) Genetic polymorphisms of microsomal and soluble epoxide hydrolase and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacogenetics 11(8):703–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mark-Kappeler CJ, Martin DS, Eyster KM (2011) Estrogens and selective estrogen receptor modulators regulate gene and protein expression in the mesenteric arteries. Vascul Pharmacol. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chawengsub Y, Gauthier KM, Nithipatikom K, Hammock BD, Falck JR, Narsimhaswamy D, Campbell WB (2009) Identification of 13-hydroxy-14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid as an acid-stable endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rabbit arteries. J Biol Chem 284(45):31280–31290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zeldin DC, Kobayashi J, Falck JR, Winder BS, Hammock BD, Snapper JR, Capdevila JH (1993) Regio- and enantiofacial selectivity of epoxyeicosatrienoic acid hydration by cytosolic epoxide hydrolase. J Biol Chem 268(9):6402–6407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olearczyk JJ, Field MB, Kim IH, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Imig JD (2006) Substituted adamantyl-urea inhibitors of the soluble epoxide hydrolase dilate mesenteric resistance vessels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 318(3):1307–1314. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li J, Carroll MA, Chander PN, Falck JR, Sangras B, Stier CT (2008) Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor, AUDA, prevents early salt-sensitive hypertension. Front Biosci 13:3480–3487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Corenblum MJ, Wise VE, Georgi K, Hammock BD, Doris PA, Fornage M (2008) Altered soluble epoxide hydrolase gene expression and function and vascular disease risk in the stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 51(2):567–573. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.102160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fornage M, Hinojos CA, Nurowska BW, Boerwinkle E, Hammock BD, Morisseau CH, Doris PA (2002) Polymorphism in soluble epoxide hydrolase and blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 40(4):485–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agrawal DK, Daniel EE (1985) Two distinct populations of [3H]prazosin and [3H]yohimbine binding sites in the plasma membranes of rat mesenteric artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 233(1):195–203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Medgett IC, Hicks PE, Langer SZ (1984) Smooth muscle alpha-2 adrenoceptors mediate vasoconstrictor responses to exogenous norepinephrine and to sympathetic stimulation to a greater extent in spontaneously hypertensive than in Wistar Kyoto rat tail arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 231(1):159–165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bolli P, Erne P, Ji BH, Block LH, Kiowski W, Buhler FR (1984) Adrenaline induces vasoconstriction through post-junctional alpha 2 adrenoceptors and this response is enhanced in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl 2(3):S115–S118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McNeill AM, Leslie FM, Krause DN, Duckles SP (1999) Gender difference in levels of alpha2-adrenoceptor mRNA in the rat tail artery. Eur J Pharmacol 366(2–3):233–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tejera N, Balfagon G, Marin J, Ferrer M (1999) Gender differences in the endothelial regulation of alpha2-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction in the rat aorta. Clin Sci (Lond) 97(1):19–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mehrotra S, Gupta S, Villalon CM, Boomsma F, Saxena PR, MaassenVanDenbrink A (2007) Rat carotid artery responses to alpha-adrenergic receptor agonists and 5-HT after ovariectomy and hormone replacement. Headache 47(2):236–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gisclard V, Flavahan NA, Vanhoutte PM (1987) Alpha adrenergic responses of blood vessels of rabbits after ovariectomy and administration of 17 beta-estradiol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 240(2):466–470 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ferrer M, Osol G (1998) Estrogen replacement modulates resistance artery smooth muscle and endothelial alpha2-adrenoceptor reactivity. Endothelium 6(2):133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen DC, Duckles SP, Krause DN (1999) Postjunctional alpha2-adrenoceptors in the rat tail artery: effect of sex and castration. Eur J Pharmacol 372(3):247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gong G, Johnson ML, Pettinger WA (1995) Testosterone regulation of renal alpha 2B-adrenergic receptor mRNA levels. Hypertension 25(3):350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khalid M, Giudicelli Y, Dausse JP (2001) An up-regulation of renal alpha(2)A-adrenoceptors is associated with resistance to salt-induced hypertension in Sabra rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 299(3):928–933 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khalid M, Ilhami N, Giudicelli Y, Dausse JP (2002) Testosterone dependence of salt-induced hypertension in Sabra rats and role of renal alpha(2)-adrenoceptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300(1):43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gong G, Dobin A, Johnson ML, Pettinger WA (1996) Sexual dimorphism of renal alpha2-adrenergic receptor regulation in Dahl rats. Hypertens Res 19(2):83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Intengan HD, Smyth DD (1997) Renal alpha 2a/d-adrenoceptor subtype function: Wistar as compared to spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol 121(5):861–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]